Abstract

Seborrheic keratoses (SK) are the most common skin tumour of humanity. The incidence of this purely benign epithelial proliferation is increasing with age and exposure to ultraviolet light. It has a remarkable variability in its clinical presentation raising some differential diagnoses. Recently, oncogenic mutations have been detected involved in the development of SK, which, however, do not bear the risk of malignant transformation. SK may also develop with the use of modern targeted drugs for the treatment of malignancies. The classical treatment options for SK are cryotherapy and curettage. Recently, topical treatment with 40% hydrogen peroxide and the nitric-zinc complex has been investigated. Ablative laser therapy is an effective treatment as well.

Keywords: Seborrheic keratosis, Oncogenic mutations, Targeted tumour therapy, Topical treatment, Lasers

Introduction

Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are the most common benign epithelial tumours of humanity with an increasing incidence with age. The predilection zones of SKs are trunk and forehead. An important clinical sign is the formation of multiple horn pearls [1]. In dermoscopy, comedo-like openings, milia-like cysts, and fissures and ridges are characteristic [2]. Although most SKs have a maximum diameter of less than 4 cm, sometimes giant lesions develop that raises some possible differential diagnoses including Buschke-Löwenstein tumours [3].

On the histologic level six subtypes can be differentiated: - hyperkeratotic type; - acanthotic type; - reticular/adenoid type; - clonal type; - irritated type; - melanoakanthoma [1]. Multiple eruptive SKs was known as Leser-Trélat-syndrome gain importance as a paraneoplasia [4].

Pathogenesis

The etiopathology of SKs is not completely understood. They are considered a sign of ageing skin and UV-exposure may be associated with. The viral hypothesis is suggesting the involvement of human papillomavirus has not been substantiated by recent studies [5], [6].

Expression of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) has been evaluated in SKs versus normal skin by immunohistochemistry, Western blotting and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). APP and its downstream products (i.e. amyloid-β42) were stronger expressed in SK than in paired adjacent normal skin tissues. In contrast, the expression of its key secretase (i.e. β-secretase1) was low.

Furthermore, APP expression was higher in UV-exposed than non-exposed skin sites and the older age group. APP expression correlated positively with age in the epidermis (p < 0.05), but not in the dermis. These findings suggest that overexpression of APP may promote the onset of SK and is a marker of skin ageing and UV damage [7].

Exome sequencing of SKs indicated three mutations per megabase pairs of the targeted sequence. The mutational pattern depicted typical UV signature with the majority of alterations being C > T and CC > TT base changes at dipyrimidinic sites. The FGFR3 mutations were the most frequent, detected in 48% of lesions, followed by the PIK3CA (32%), TERT promoter (24%) and DPH3 promoter mutations (24%) [8].

Neel et al., (2016) investigated SKs, which frequently have acquired oncogenic mutations in the receptor tyrosine kinase/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signalling cascade. They demonstrated that SKs have a hypersensitivity to Akt inhibition. FoxN1 is a novel biomarker of the oncogenically activated but benign phenotype in SKs.

They also established that Akt inhibition caused an increase in p53 protein expression, but not RNA expression and that Akt-mediated apoptosis was dependent on p53 and FoxO3, a target of Akt [9].

Hyperkeratotic type

The histologic feature of this common subtype is orthohyperkeratosis with papillomatosis. Acanthosis is mild or absent. Horn pearls are missing (Figure 1) [1].

Figure 1.

Hyperkeratotic seborrheic keratosis

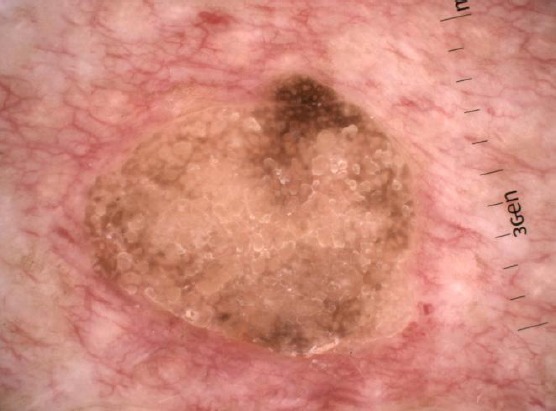

This is the most common subtype (Figure 2). The tumours are characterised by huge acanthosis but mild or missing hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis. Horny invaginations that on cross-sections appear as “pseudo-horn cysts” are numerous. True horn cysts are also seen, which show sudden and complete keratinisation with a very thin granular layer surrounding it [1].

Figure 2.

Dermoscopic presentation of acanthotic seborrheic keratosis with multiple pseudo-horn cysts

Reticular or adenoid type

The SKs of this subtype is characterised by reticular acanthosis of thin, double row with mild to moderate hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis. These SKs are often hyperpigmented. Horn pearls are uncommon. This subtype is more common in sun-exposed areas (Figures 3 and 4) [10].

Figure 3.

Hyperpigmented adenoid seborrheic keratosis of the vulva

Figure 4.

Reticular seborrheic keratosis with an oak-leave appearance

Clonal type

In this type marked acanthosis and papillomatosis are associated with orthohyperkeratosis. Tumour cells are spindle-shaped. With a tumour demarcated tumour, islands of basaloid cell nests are found. Major differential diagnosis to clinal SK is pagetoid Bowen’s disease (Figure 5). Immunohistochemistry may be helpful in selected cases to distinguish both entities. Cytokeratin-10 is more expressed in clonal SK, while increased Ki-67-positive cells and the presence of > 75% positive p16 cells is in favour of pagetoid Bowen’s disease [11].

Figure 5.

Giant hyperpigmented clonal seborrheic keratosis resembling Buschke-Löwenstein a tumour

Irritated type

Here, a proliferation of spindle-shaped eosinophilic tumours cells is found, sometimes in whorl-like formations. Dyskeratotic cells may be present. In clinical practice, it is important to separate irritated SK from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (Figure 6). Immunohistochemistry may be helpful to distinguish both entities. In a recent study, the combination of U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein protein IMP3 and B-cell lymphoma 2 regulatory protein (BCL-2) may has been shown diagnostic utility in distinguishing between irritated SK and SCC in daily clinical practice while epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) immunohistochemistry did not appear to be useful in this setting [12].

Figure 6.

Irritated seborrheic keratosis resembling cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

In the illustrated case of an SK prepatellar, koilocytes were present as a histological sign of a secondary viral infection. A higher prevalence of human papillomavirus p16 expression has been found preferably in genital SKs with 65% to 69.6% [13], [14]. The prevalence is lower in vulvar SKs in women older than 50 years with 14.3% [15]. Herpes virus 6A is another virus that can be detected in SKs [16]. In a recent study, Merkel cell polyomavirus could be detected in 6 of 23 SKs by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) [14]. Expression of p16 and p21 had been detected in SKs with Bowenoid transformation [17].

With the development of checkpoint inhibitors, new adverse events have been seen in treated patients. Rhambia et al., (2018) reported on inflammatory reactions in SKs induced by programmed cell death-1 (PD1) inhibitor nivolumab. Chronic viral infections are known to result in T-cell tolerance because of persistent antigen stimulation. A viral infection is a secondary event in SKs. PD-1 inhibition can reinvigorate exhausted T cells, which are accordingly able to decrease viral load. Thus, the inflammatory reaction of SKs may be the result of PD-1 inhibition reactivating virally driven T lymphocytes [18].

LL-37 is a naturally occurring 37-amino-acid peptide that is part of the innate immune system in human skin. Studies have shown that intra-tumoral injections of LL-37 stimulate the innate immune system by activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which mediate tumour destruction. It has been reported that LL-37 induces an inflammatory response to SKs characterised by a lichenoid cellular infiltrate [19].

Melanoakanthoma

This is the hyperpigmented acanthotic type with a proliferation of basaloid cells with mild or even absent hyperkeratosis. Numerous melanocytes are intermingled. Melanophages are located within the dermis underneath a tumour (Fig. 7) [1].

Figure 7.

Melanoacanthoma with prominent horn cysts

Treatment

Patients have wide ranges of motivations for treating or removing SKs, including embarrassment from the stigmatising appearance of the lesion, physical irritation or pruritus, and a desire to look younger [20].

Lesions that are inflamed, bleeding, ulcerated, or sufficiently irritated should be further characterised by a biopsy or excision to rule out malignancies [21].

Two recent randomised trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02667236 and NCT02667275) compared the safety and efficacy of 40% hydrogen peroxide topical solution (HP40; ESKATA™, Aclaris Therapeutics, Inc., Wayne, PA) versus vehicle (VEH) for the treatment of SKs. This trial included 937 patients with 4 SKs who were randomised 1:1 to HP40 or VEH.

The clinical response was graded using the Physician’s Lesion Assessment (PLA) scale (0: Clear; 1: Near-Clear; 2: ≤ 1 mm thick, and 3: > 1 mm thick). After one treatment, SKs with PLA > 0 were re-treated 3 weeks later. At day 106, significantly more HP40 patients versus VEH achieved PLA = 0 on all 4 SKs (4% or 8% vs 0%) and 3 of 4 SKs (13% or 23 % vs 0%). A higher mean per-patient percentage of SKs were Clear (25% vs 2 % or 34% vs 1%) and Clear/Near-Clear (47% vs 10% or 54% vs 5%) with HP40 versus VEH. Most local skin reactions were mild and resolved by day 106 [22]. HP40 may act not only through its direct oxidation of organic tissues, generation of reactive oxygen species, and local lipid peroxidation but also by the generation of local concentrations of oxygen that are toxic to SK cells [23] [24].

A nitric-zinc complex has been used to treat 50 SK lesions. The topical formulation is an aqueous solution containing nitric acid, zinc and copper salts, and organic acids (acetic, lactic, and oxalic acid). Treatment consisted of the topical application to obtain a whitening or yellowish reaction on top of SKs. Application of the nitric-zinc solution was performed every other week until clinical and dermoscopic clearance or crust formation, for a maximum of 4 applications. All subjects, who reported no or minimal discomfort during and after the application of the solution, completed the study. After eight weeks, complete clearance was observed in 37 lesions after an average of 3 applications/lesion. A partial response, with minimal persistent residual spots, was detected in the remaining 13 lesions. All patients with complete clearance showed no relapses at a 6-month follow-up [25].

Case reports have been published with the successful use of either diclofenac gel, imiquimod, dobesilate or calcitriol [26], [27], [28], [29].

Patients preferred cryotherapy over curettage in a small trial (n = 25). But physicians rating observed more redness at 6 weeks and the tendency for hypopigmented scar formation at greater than 12 months with curettage. Leftover SK lesion occurred more frequently with cryotherapy in the short and long term [30].

The use of ablative lasers and cryotherapy for SKs has a long tradition. But which method is better? A comparative trial was carried out on 42 patients with SK of 0.5-3 cm, located on the back, chest, face and neck. Lesions with a similar size and location on the same patient were matched. In the same session, half of the lesions were treated with cryotherapy, while the other half were treated with Er: YAG laser [31].

Following the first treatment, complete healing was detected in all of the lesions (100%) treated with Er: YAG lasers, while the healing rate was 68% in the cryotherapy group (p < 0.01). In the Er: YAG laser-treated group, hyperpigmentation was significantly lower and more erythema developed than in the cryotherapy group [31]. The results are in one line with our own experiences with Er: YAG laser [32].

The CO2 laser is another opportunity but with a higher risk of scarring and pigmentary changes [33]. Small case series have used intense pulsed light [34].

In conclusion, SKs are very common. Their clinical variability can confuse with other potentially malignant skin diseases. Treatment options include topical and surgical options.

Footnotes

Funding: This research did not receive any financial support

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist

References

- 1.Jackson JM, Alexis A, Berman B, Berson DS, Taylor S, Weiss JS. Current Understanding of Seborrheic Keratosis: Prevalence, Etiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(10):1119–25. PMid:26461823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takenouchi T. Key points in dermoscopic diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma and seborrheic keratosis in Japanese. J Dermatol. 2011;38(1):59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01093.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01093.x PMid:21175757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wollina U, Chokoeva A, Tchernev G, Heinig B, Schönlebe J. Anogenital giant seborrheic keratosis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152(4):383–6. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.16.04945-2. PMid:25604463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiers BH, Sahn RE, Callen JP. Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(2):73–98. doi: 10.3322/caac.20005. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20005 PMid:19258446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsambaos D, Monastirli A, Kapranos N, Georgiou S, Pasmatzi E, Stratigos A, Koutselini H, Berger H. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in nongenital seborrhoeic keratoses. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287(6):612–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00374085. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00374085 PMid:748715;1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kambiz KH, Kaveh D, Maede D, Hossein A, Nessa A, Ziba R, Alireza G. Human Papillomavirus Deoxyribonucleic Acid may not be Detected in Non-genital Benign Papillomatous Skin Lesions by Polymerase Chain Reaction. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(4):334–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.135475. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5154.135475 PMid:25071248 PMCid: PMC4103265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Wang Y, Zhang W, Jiang L, Zhou W, Liu Z, Li S, Lu H. Overexpression of Amyloid Precursor Protein Promotes the Onset of Seborrhoeic Keratosis and is Related to Skin Ageing. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(6):594–600. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2911. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2911 PMid:29487944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heidenreich B, Denisova E, Rachakonda S, Sanmartin O, Dereani T, Hosen I, Nagore E, Kumar R. Genetic alterations in seborrheic keratoses. Oncotarget. 2017;8(22):36639–49. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16698. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16698 PMid:28410231 PMCid: PMC5482683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neel VA, Todorova K, Wang J, Kwon E, Kang M, Liu Q, Gray N, Lee SW, Mandinova A. Sustained Akt Activity Is Required to Maintain Cell Viability in Seborrheic Keratosis, a Benign Epithelial Tumor. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(3):696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2015.12.023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2015.12.023 PMid:26739095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roh NK, Hahn HJ, Lee YW, Choe YB, Ahn KJ. Clinical and Histopathological Investigation of Seborrheic Keratosis. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(2):152–8. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.2.152. https://doi.org/10.5021/ad.2016.28.2.152 PMid:27081260 PMCid: PMC4828376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalegowda IY, Böer-Auer A. Clonal Seborrheic Keratosis Versus Pagetoid Bowen Disease: Histopathology and Role of Adjunctive Markers. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(6):433–9. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000669. https://doi.org/10.1097/DAD.0000000000000669 PMid:28475506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richey JD, Deng AC, Dresser K, O'Donnell P, Cornejo KM. Distinguishing between irritated seborrheic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma in situ using BCL-2 and IMP3 immunohistochemistry. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45(8):603–9. doi: 10.1111/cup.13269. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13269 PMid:29726030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey NT, Leecy T, Wood BA. Immunohistochemical staining for p16 is a useful adjunctive test in the diagnosis of Bowen's disease. Pathology. 2013;45(4):402–7. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e328360c064. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAT.0b013e328360c064 PMid:23635817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillen LM, Rennspiess D, Speel EJ, Haugg AM, Winnepenninckx V, Zur Hausen A. Detection of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus in Seborrheic Keratosis. Front Microbiol. 2018;8:2648. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02648. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02648 PMid:29375515 PMCid: PMC5767171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reutter JC, Geisinger KR, Laudadio J. Vulvar seborrheic keratosis: is there a relationship to human papillomavirus? J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014;18(2):190–4. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182952357. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182952357 PMid:24556611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding L, Mo X, Zhang L, Zhou F, Zhu C, Wang Y, Cai C, Liu Y, Wei F, Cai Q. High prevalence and correlates of human herpesvirus-6A in nevocytic nevus and seborrheic diseases: Implication from a pilot study of skin patient tissues in Shanghai. J Med Virol. 2018;90(9):1532–40. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25217 PMid:29727474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu YH, Hsiao PF, Chen CK. Seborrheic keratosis with bowenoid transformation: the immunohistochemical features and its association with human papillomavirus infection. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(6):462–8. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000285. https://doi.org/10.1097/DAD.0000000000000285 PMid:25747812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rambhia PH, Honda K, Arbesman J. Nivolumab induced inflammation of seborrheic keratoses: a novel cutaneous manifestation in a metastatic melanoma patient. Melanoma Res. 2018;28(5):475–77. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000477. https://doi.org/10.1097/CMR.0000000000000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolkar T, Trinidad CM, Nelson KC, Amaria RN, Nagarajan P, Torres-Cabala CA, Ivan D, Prieto VG, Tetzlaff MT, Curry JL, Aung PP. Dermatologic toxicity from novel therapy using antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in melanoma: A detailed examination of the clinicopathologic features. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45(7):539–44. doi: 10.1111/cup.13262. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13262 PMid:29665030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Del Rosso JQ. A closer look at seborrheic keratoses: patient perspectives, clinical relevance, medical necessity, and implications for management. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10(3):16–25. PMid:28360965 PMCid: PMC5367878. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karadag AS, Parish LC. The status of the seborrheic keratosis. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(2):275–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.09.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.09.011 PMid:29566932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baumann LS, Blauvelt A, Draelos ZD, Kempers SE, Lupo MP, Schlessinger J, Smith SR, Wilson DC, Bradshaw M, Estes E, Shanler SD. Safety and efficacy of hydrogen peroxide topical solution, 40%(w/w) in patients with seborrheic keratoses: results from two identical, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies (A-101-SEBK-301/302) Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bekeschus S, Kolata J, Winterbourn C, et al. Hydrogen peroxide: a central player in physical plasma-induced oxidative stress in human blood cells. Free Radic Res. 2014;48(5):542–9. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2014.892937. https://doi.org/10.3109/10715762.2014.892937 PMid:24528134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oyewole AO, Wilmot MC, Fowler M, et al. Comparing the effects of mitochondrial targeted and localized antioxidants with cellular antioxidants in human skin cells exposed to UVA and hydrogen peroxide. FASEB J. 2014;28(1):485–94. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-237008. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-237008 PMid:24115050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lacarrubba F, Nasca MR, Verzì AE, Micali G. A novel topical agent in the treatment of seborrheic keratoses: A proof of concept study by clinical and dermoscopic evaluation. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:5. doi: 10.1111/dth.12526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aktaş H, Ergin C, Keseroğlu HÖ. Diclofenac gel may be a new treatment option for seborrheic keratosis. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7(3):211–2. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.182363. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.182363 PMid:27294065 PMCid: PMC4886602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karadag AS, Ozlu E, Uzuncakmak TK, Akdeniz N, Cobanoglu B, Oman B. Inverted follicular keratosis successfully treated with imiquimod. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7(3):177–9. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.182354. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.182354 PMid:27294052 PMCid: PMC4886589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuevas P, Angulo J, Salgüero I, Giménez-Gallego G. Clearance of seborrhoeic keratoses with topical dobesilate. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr.01.2012.5628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu'o'ng Kv, Nguyn LT. The roles of vitamin D in seborrhoeic keratosis: possible genetic and cellular signalling mechanisms. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2013;35(6):525–31. doi: 10.1111/ics.12080. https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.12080 PMid:23859137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wood LD, Stucki JK, Hollenbeak CS, Miller JJ. Effectiveness of cryosurgery vs curettage in the treatment of seborrheic keratoses. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(1):108–9. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.275. https://doi.org/10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.275 PMid:23324775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurel MS, Aral BB. Effectiveness of erbium: YAG laser and cryosurgery in seborrheic keratoses: Randomized, prospective intraindividual comparison study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(5):477–80. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1024597. https://doi.org/10.3109/09546634.2015.1024597 PMid:25798694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wollina U. Erbium-YAG laser therapy –analysis of more than 1,200 treatments. Glob Dermatol. 2016;3(2):268–72. https://doi.org/10.15761/GOD.1000171. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruscino N, Conti R, Campolmi P, Bonan P, Cannarozzo G, Lazzeri L, Moretti S. Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra and 10,600-nm CO2 laser, a good choice. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16(3):114–6. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2013.854640. https://doi.org/10.3109/14764172.2013.854640 PMid:24131098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piccolo D, Di Marcantonio D, Crisman G, Cannarozzo G, Sannino M, Chiricozzi A, Chimenti S. Unconventional use of intense pulsed light. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:618206. doi: 10.1155/2014/618206. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/618206 PMid:25276803 PMCid: PMC4167959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]