Abstract

Background and Purpose:

In the treatment of severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), thrombolytic use and clot size are known to influence clot lysis rates. We evaluated the effect of other variables on IVH clot lysis rates among patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) or placebo.

Methods:

One hundred patients with IVH and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) volume < 30cc requiring hemergency external ventricular drainage, from two multicenter trials were treated with intraventricular administration of rt-PA (n=78; 53M/25F), or placebo (n=22; 7M/15F). IVH volume was quantified daily by head computed tomography. A segmented linear regression using an optimized spline knot for each patient was fit. Random effects linear regression was used to estimate the effect of prespecified patient characteristics on clot lysis rates over the first 6 days.

Results:

Stability IVH volumes were larger in males (N=60) (54±5cc) than females (N=40) (36±5cc; P=0.01). Intraventricular thrombolytic treatment was associated with an increase in clot lysis rate of 14.6% of stability IVH volume/day before the spline knot compared to the placebo group (P<0.001). After adjustment for thrombolytic, higher baseline serum plasminogen and lower baseline platelet count were independently associated with an increase in clot lysis of 1.28%/day per 10g/dL increase (P<0.001) and 0.70% /day per 10 × 103/uL decrease (P<0.001) before the knot, respectively.

Conclusions:

While thrombolysis remains the major determinant of IVH clot lysis rate, higher baseline serum plasminogen and lower platelet count also predict faster clot lysis. Further studies are needed to confirm whether plasminogen availability and thrombus structure impact IVH clot removal.

Keywords: Intracerebral hemorrhage, Intracerebral hemorrhage, Thombolysis, External ventricular drainage, Cerebrospinal fluid

Introduction

The current therapy for intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) causing obstructive hydrocephalus is drainage of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through an external ventricular drain (EVD). Thrombolytic drugs, particularly recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA), can be administered safely into the ventricles of patients with IVH once IVH volume has stabilized and these drugs significantly shorten the time of blood clot resolution in both experimental models and humans (1–5). The identification of other factors affecting clot lysis rates may be important for determining the optimal dosing regimen of rt-PA which may differ based on patient-specific characteristics.

In our initial prospective randomized trial using intraventricular Urokinase, IVH clot resolution rate was favorably affected by female gender (5). In this study, we explore the effect of gender and other variables on clot lysis rates in patients with acute IVH treated with either placebo or rt-PA using completed phases of the CLEAR IVH studies. We hypothesize that intraventricular rt-PA therapy results in faster clot lysis rates in females compared to males presenting with IVH.

Materials and Methods

This multicenter clinical study was performed under the approval of the Institutional Review Board committee of each participating center. Written consent was obtained from all participants or their legal representatives.

Study Design and Patient Selection

The CLEAR IVH Trial study procedures have been published previously (4) (Supp-Figure 1-supplemental material, provides an overview of study designs). In the initial Safety study, 48 patients (26M/22F) with severe IVH, and supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) volume < 30cc, with EVD for treatment of obstructive hydrocephalus were randomized to receive 3.0 mg intraventricular (IVR) rt-PA in 1 ml of normal saline (N=26) or IV placebo (pcb; 1 ml normal saline) (N=22) every 12 hours (q12h). Fifty-two patients (34M/18F), with the same indications participated in a 2-part open label dose escalation trial of IVR rt-PA at doses 0.3 or 1.0 mg q12h or 1.0 mg q8h. Patients were enrolled within 48 hours after the initial hemorrhage.

EVD Placement

Patients in these studies required emergency EVD. In the majority of patients (63%) EVDs were placed into the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle with the least blood. Seven patients had more than one catheter simultaneously. Intraventricular location of the catheter tip was confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scan performed 6 hours after placement.

Documenting Clot Stability

The first CT scan performed at least 6 hours after EVD placement that demonstrated a stable IVH and ICH volume and either no or stable catheter tract hemorrhage was designated as the stability CT. Evidence of additional hemorrhage required delaying study agent administration for at least 12 hours and until clot stabilization was established.

Treatment Protocol

The study dose of rt-PA or placebo was delivered after an effort was made to aspirate at least 4 ml of CSF. Isovolemic injection of the study agent was followed by a 2-ml flush. The EVD was then closed for one hour to allow adequate time for drug-clot interaction and re-opened only if necessary to control medically refractory ICP elevations. After the one-hour closure, the EVD was reopened to drain CSF at the gradient set by the treating physician. The first injection of study agent occurred no sooner than 12 hours, but no later than 48 hours after the diagnostic CT scan and at least 6 hours after EVD placement. Study agent injections continued at the specified interval until clearance of hyperdense blood from the 3rd and 4th ventricle was observed on daily head CT or for a maximum of 12 doses in the Clear A and B studies.

Evaluation of Clot Resolution

Head CT scans were obtained before the initial intraventricular injection and then daily for quantitative determination of IVH volume. Additional CT scans were performed in the event of acute neurological deterioration. The volumes of intraventricular and intraparenchymal hematomas were measured independently by a blinded experienced researcher using standard computerized volumetric analysis as described by Steiner et al. (6). Size of IVH clot was taken into account in the analysis of clot resolution by using IVH clot volume standardized as a percent of the IVH clot volume on the stability CT. The time of each scan with respect to the time of the stability CT scan was determined to the minute then converted to 24 hour periods and proportions thereof.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of Groups

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between rt-PA and Pcb-treated patients and between male and female patients. Wilcoxon rank-sum test, test of medians, Student’s t-test, and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test were used for comparisons as appropriate. Summary data are presented as mean ± SD, unless otherwise indicated. “Baseline” refers to data at clinical presentation, “stability” to data at time of stability CT scan. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 11.1 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA 2010)

Regression Models

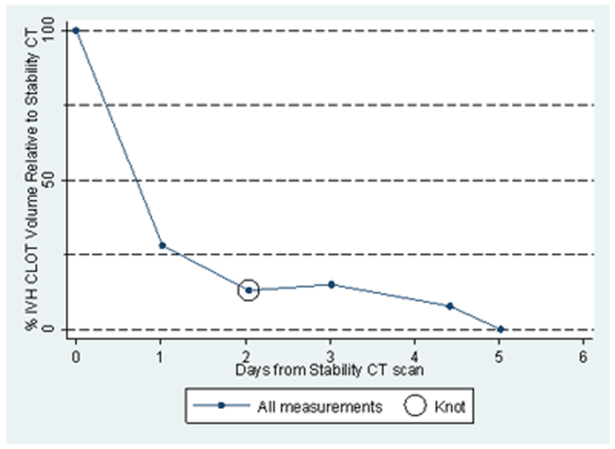

Previous work with CT data of 5–7 days duration (4) has depicted a non-linear association between standardized IVH volumes and time. In the past this has been dealt with by limiting linear models of the clot lysis process to the initial 72 hours following stability CT, and by including quadratic terms when examining longer periods of time (7). The distinct decrease in clot lysis rates after an initial period of lysis at a higher rate observed for most patients in this cohort led to the consideration of a spline or segmented linear regression model (Figure 1)(8).

Figure 1:

IVH Clot volume remaining over time as a percentage of stability CT clot volume in one rt-PA treated patient, showing the initial designation of the spline knot for this patient.

To implement the spline models, each patient’s standardized IVH volumes were plotted against time and the plot was reviewed to identify the time at which a change in clot lysis rate (spline knot) seemed to take place if this phenomenon was present (initial time estimate). Alternative models in which the spline knot was shifted to either side of the initial time estimate were compared. The time associated with the highest likelihood (best fit) was selected for the spline knot. If there was a tie in the likelihood for two times, the earlier time was chosen. No spline knot was assigned for a patient’s data if the relationship appeared linear.

A series of single candidate regression models was run to determine factors potentially affecting clot lysis for inclusion in a multivariate regression model. All analyses were performed with an offset of 100% instead of a constant term and included linear terms for time before and after the spline knot with cross products of each term with treatment with rt-PA (base model). Cross-products of these two linear terms with each of the candidate factors were then added to individual models. We used a random effects model which accounted for multiple measurements per patient, and included clot volume measurements up to 6 days following the stability CT. We included rt-PA dose as a variable in the analysis with dose groups as follows: Group 1 = 0.3 mg q12h; Group 2 = 1.0 mg q8h or q12h; Group 2* = 1.0 mg q12h only; Group 3 = 3.0 mg q12h; Group 4 = 1.0 mg q8h rt-PA only. The effect of each candidate factor on clot lysis rates was adjusted for the effect of rt-PA treatment. For each factor its effect on rate of clot lysis before and after the spline knot, and the change between these two, were estimated.

Several demographic and clinical characteristics were considered as the additional factors in the single candidate models: gender, stability IVH and ICH volume, time from symptom onset CT to first injection of study agent, side of EVD relative to side of greatest ventricular clot volume, and biologic effectors/modulators of clotting including age, use of antiplatelet drugs, alcohol and cocaine, baseline platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), serum fibrinogen, and plasminogen. Factors showing a strong relationship with clot lysis before the knot (P ≤ 0.05) were then combined into a multiple regression analysis with the basic model terms also included. We also evaluated baseline cerebrospinal fluid level of plasminogen available in 44 rt-PA treated patients in a separate multivariate analysis of a spline model with log-transformed baseline CSF plasminogen.

The basic spline model was compared to a model with time treated as a linear variable and to a model with time treated as a quadratic variable using the log-likelihood ratio and AIC (Aikake Information Criterion) as appropriate.

Results

For baseline clinical, laboratory and computed tomographic characteristics of the patients in this study please refer to supplementary data (Tables S1 and S2). There were significantly more males in the rt-PA treated groups compared to the Pcb-treated group (68% vs. 32%; P=0.003). Comparing variables by gender over both treatment groups, female patients were older than male patients, and males were more likely to have a history of seizures, significant alcohol and cocaine use. Stability IVH volumes were larger in males than females (median 48 vs. 27 cc; P=0.038) and males had higher admission cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) than females (median 92 vs. 78 mm Hg; P=0.004).

Four patients were removed from the analysis due to evidence of large early expansion of IVH which would have detracted from the purpose of this study to assess factors affecting clot lysis under the assumption that clot volume decreases over time. Seventy-four patients were treated with intraventricular rt-PA for a median of 1.8 days (range: 0 – 13.6 days). Twenty-two patients were treated with placebo for a median of 5.8 days (range: 0 – 14.6 days).

Regression Models

The mean time from diagnostic to stability CT was 0.64 ± 0.39 days (range: 0.0 – 1.7 days). Median spline knot time was 2.5 days after the stability CT scan (range: 0.1 – 5.2 days). Twenty-four patients had linear clot resolution over the period (maximum of 6 days) and their data points were considered to be in the pre-spline knot period. Time to first dose of study agent from symptom onset was a median of 1.2 days (range: 0.5 – 2.6 days) and time to last dose was a median of 3.6 days (range: 1.1 – 15.7 days). The overall rate of clot resolution during the first 6 days after the stability CT was 20.92% lysis of stability clot volume/day before the spline knot and a rate of 1.34% clot volume/day after the spline knot. In both treatment groups, rates were significantly different from zero pre-spline knot (Placebo 9.44%, P<0.001; rt-PA 24.07%, P<0.001), but not post-spline knot (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clot lysis by time period and treatment group

| Time period/treatment group | Clot lysis

rate [% IVH volume/day resolved relative to stability] (95% confidence interval) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-spline knot | ||

| All patients | 20.92 (18.76, 23.08) | < 0.001 |

| Placebo treated | 9.44 (4.91, 13.96) | < 0.001 |

| rt-PA treated | 24.07 (21.69, 26.46) | < 0.001 |

| Post-spline knot | ||

| All patients | 1.34 (−1.46, 4.14) | 0.349 |

| Placebo treated | 4.11 (−1.61, 9.82) | 0.159 |

| rt-PA treated | 0.55 (−2.54, 3.64) | 0.728 |

Abbreviations: IVH: intraventricular hemorrhage; rt-PA: recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (any dose).

The results of the spline models to evaluate the effect of individual factors on IVH clot volume resolved per day are presented in Table 2. Each model is adjusted using a base model which takes treatment effect and time into account. In that model, the rate of clot resolution for any rt-PA dose was estimated as 14.63% a day greater than for placebo (P<0.001). After this adjustment, lower IVH stability volume, higher baseline serum plasminogen, and lower baseline platelet count were significantly associated with faster rate of clot resolution pre-spline knot. For each 10 mL decrease in IVH stability volume, clot resolution increased by 0.85% of stability volume/day. For each 10 g/L increase in serum plasminogen, clot lysis increased by 1.01% of stability volume/day. For each 10 × 10 3/uL lower platelet count, clot lysis increased 0.40% of stability volume/day. Analysis of side of EVD placement required removal of 11 patients whose IVC placement was ambiguous (crossing the midline) and 8 patients with simultaneous dual EVDs. The faster rate of clot lysis before the knot with an ipsilateral placed catheter compared to a contralateral placed catheter was marginally significant (P=0.051). Gender, stability ICH volume and time from symptom onset to first injection of study agent were not significantly associated with rate of clot resolution. Each rt-PA dose group was associated with significantly faster clot lysis rate before the knot compared to placebo (and no difference after the knot). Comparison of rt-PA dose groups to each other (Group models 1 and 2) showed no differences in clot lysis rates before or after the knot. Since clot-lysis rates were not dependent on rt-PA dose, rt-PA treatment was considered as any rt-PA versus placebo. Test for plasminogen-rt-PA interaction was not significant (P=0.79) (data not shown). Baseline PTT was the only factor associated with clot lysis rate post spline knot (P=0.025). Factors associated with a significant change in the rate of clot resolution at the deflection point were rt-PA treatment (all doses), baseline serum plasminogen, baseline PTT, and baseline platelet count. The first two variables had the effect of flattening the clot lysis rate after the knot whereas higher baseline PTT and higher baseline platelet count were associated with an increase in clot lysis rate after the knot.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of factors associated with IVH clot lysis rate in the acute phase (over 6 days post stability) using a spline model

| Rate of lysis/day before knota | Rate of lysis/day after knota | Rate/day change: After knot - before knota |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Nb | # Patients | Estimate | 95%CI | P value | Estimate | 95%CI | P value | Estimate | 95%CI | P value |

|

Base

model: Treatment with rt-PA |

524 | 96 | 14.634 | (9.52, 19.75) | <0.001 | −3.559 | (−10.06, 2.94) | 0.283 | −18.193 | (−24.91, −11.48) | <0.001 |

| Additional modelc: | |||||||||||

| Serum plasminogen leveld | 458 | 84 | 0.101 | (0.03, 0.17) | 0.005 | −0.013 | (−0.08, 0.06) | 0.722 | −0.114 | (−0.19, −0.04) | 0.003 |

| IVH stability volumed | 524 | 96 | −0.085 | (−0.15, −0.02) | 0.007 | −0.021 | (−0.10, 0.06) | 0.592 | 0.063 | (−0.02, 0.15) | 0.144 |

| Platelet leveld | 524 | 96 | −0.04 | (−0.07, −0.01) | 0.004 | −0.007 | (−0.04, 0.03) | 0.671 | 0.032 | (0.00, 0.06) | 0.049 |

| Antiplatelet medication | 524 | 96 | −3.129 | (−10.44, 4.18) | 0.401 | −2.454 | (−12.66, 7.75) | 0.637 | 0.674 | (−10.01, 11.36) | 0.902 |

| Fibrinogend | 478 | 88 | −0.004 | (−0.02, 0.01) | 0.685 | 0 | (−0.02, 0.02) | 0.968 | 0.004 | (−0.02, 0.03) | 0.719 |

| History of cocaine | 524 | 96 | −1.644 | (−7.72, 4.44) | 0.596 | −0.493 | (−8.26, 7.27) | 0.901 | 1.151 | (−6.60, 8.90) | 0.771 |

| History of alcohol | 524 | 96 | 1.229 | (−4.30, 6.76) | 0.663 | −4.485 | (−11.60, 2.63) | 0.217 | −5.714 | (−12.98, 1.55) | 0.123 |

| PT stabilityd | 474 | 87 | −0.732 | (−1.81, 0.34) | 0.181 | −0.359 | (−1.79, 1.07) | 0.623 | 0.374 | (−1.10, 1.85) | 0.619 |

| PTT stabilityd | 489 | 90 | −0.064 | (−0.50, 0.37) | 0.775 | 0.64 | (0.08, 1.20) | 0.025 | 0.704 | (0.16, 1.24) | 0.011 |

| Old age (< 60 years) | 524 | 96 | −1.691 | (−6.17, 2.79) | 0.459 | 1.316 | (−4.36, 7.00) | 0.65 | 3.008 | (−2.75, 8.76) | 0.306 |

| Gender | 524 | 96 | 0.067 | (−4.48, 4.62) | 0.977 | 3.258 | (−2.69, 9.21) | 0.283 | 3.192 | (−2.76, 9.14) | 0.293 |

| Stability ICH volume | 524 | 96 | −0.019 | (−0.23, 0.19) | 0.857 | 0.013 | (−0.26, 0.28) | 0.926 | 0.032 | (−0.24, 0.31) | 0.817 |

| Symptom onset to first dose (hr) | 524 | 96 | 0.234 | (−4.16, 4.63) | 0.917 | −0.501 | (−6.62, 5.62) | 0.872 | −0.735 | (−6.94, 5.47) | 0.816 |

| Ipsilateral EVD | 419 | 77 | 6.044 | (−0.03, 12.12) | 0.051 | −0.05 | (−8.07, 7.97) | 0.99 | −6.093 | (−14.48, 2.29) | 0.154 |

| Group Model 1 | 524 | 96 | |||||||||

| Group1_S_t | 17.01 | (8.62, 25.40) | <0.001 | −9.231 | (−20.58, 2.12) | 0.111 | −26.241 | (−37.36, −15.12) | <0.001 | ||

| Group2_S_t | 14.168 | (8.64, 19.70) | <0.001 | −2.442 | (−9.42, 4.53) | 0.492 | −16.61 | (−23.78, −9.44) | <0.001 | ||

| Group3_S_t | 14.57 | (8.30, 20.84) | <0.001 | −4.146 | (−12.21, 3.92) | 0.314 | −18.717 | (−26.91, −10.52) | <0.001 | ||

| Group 1 – Group 2 | 2.842 | (−4.88, 10.57) | 0.471 | −6.789 | (−17.37, 3.79) | 0.208 | |||||

| Group 1 – Group 3 | 2.44 | (−5.83, 10.71) | 0.563 | −5.085 | (−16.41, 6.24) | 0.379 | |||||

| Group 2 – Group 3 | −0.402 | (−5.75, 4.95) | 0.883 | 1.704 | (−5.23, 8.64) | 0.630 | |||||

| Group Model 2 | 524 | 96 | |||||||||

| Group1_S_t | 17.015 | (8.62, 25.41) | < 0.001 | −5.136 | (−14.94, 4.67) | 0.304 | −26.26 | (−37.38, −15.14) | < 0.001 | ||

| Group2*_S_t | 14.989 | (6.29, 23.69) | 0.001 | 3.858 | (−5.11, 12.83) | 0.399 | −15.24 | (−26.31, −4.17) | 0.007 | ||

| Group3_S_t | 14.576 | (8.30, 20.85) | < 0.001 | −0.043 | (−5.73, 5.64) | 0.988 | −18.728 | (−26.92, −10.54) | < 0.001 | ||

| Group4_S_t | 13.975 | (8.24, 19.71) | < 0.001 | 1.12 | (−3.32, 5.56) | 0.621 | −16.965 | (−24.39, −9.54) | < 0.001 | ||

| Group 1 - Group 2* | 2.026 | (−8.21, 12.27) | 0.698 | −8.994 | (−22.28, 4.29) | 0.185 | |||||

| Group 1 - Group 4 | 3.04 | (−4.83, 10.91) | 0.449 | −6.255 | (−17.02, 4.51) | 0.255 | |||||

| Group 2* - Group 4 | 1.014 | (−7.18, 9.21) | 0.808 | 2.738 | (−7.27, 12.75) | 0.592 | |||||

| Group 1 - Group 3 | 2.439 | (−5.84, 10.72) | 0.564 | −5.092 | (−16.42, 6.24) | 0.378 | |||||

| Group 2* - Group 3 | 0.413 | (−8.17, 9.00) | 0.925 | 3.902 | (−6.72, 14.52) | 0.471 | |||||

| Group 3 - Group 4 | 0.601 | (−4.95, 6.15) | 0.832 | −1.163 | (−8.38, 6.05) | 0.752 | |||||

Each patient had a specific optimized spline knot to identify the deflection point in their lysis rate, if appropriate. Estimate is expressed as % of the IVH volume on the stability CT scan resolved per day.

Number of measurements across patients used in the model.

Each additional single candidate model had time and treatment with rt-PA included with spline terms.

Variable was centered by its median before a cross product with time relative to stability was obtained.

Abbreviations: IVH: intraventricular hemorrhage; CI: confidence interval; rt-PA: tissue plasminogen activator; PT: prothrombin time; PTT: partial thromboplastin time; Group 1 = 0.3 mg q12h rtPA; Group 2 = 1.0 mg q8h or q12h rtPA; Group 2* = 1.0 mg q12h rtPA only; Group 3 = 3.0 mg q12h rtPA; Group 4 = 1.0 mg q8h rtPA only. For each dose group, the baseline is placebo and the estimates are slope differences from placebo. Group model 1 combines 1 mg rtPA q8h and q12h groups; group model 2 considers these dose frequencies separately.

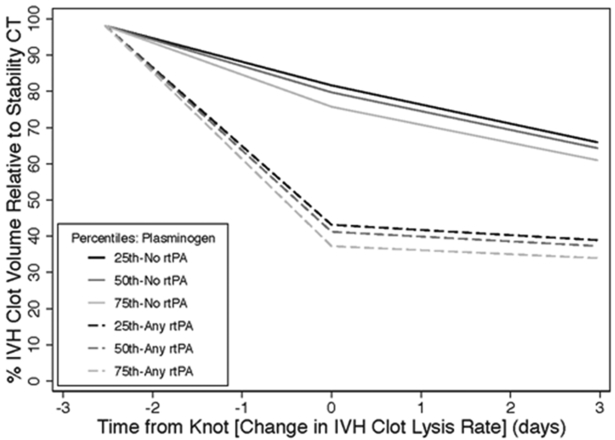

In the multivariate analysis, rt-PA treatment (any dose) as well as higher baseline serum plasminogen and lower baseline platelet count remained significant predictors of faster clot lysis pre-spline knot and indicated a change in the slope of the clot lysis rate (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Final model of factors associated with IVH clot lysis rate in the acute phase, using a spline model

| Rate of lysis/day before knota | Rate of lysis/day after knota | Rate/day change:

After knot - before knota |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Nb | # Patients | Estimate | 95%CI | P value | Estimate | 95%CI | P value | Estimate | 95%CI | P value |

| Time relative to stability | 458 | 84 | 10.05 | (5.73, 14.37) | < 0.001 | 4.61 | (−0.86, 10.08) | 0.099 | −5.44 | (−11.49, 0.61) | 0.078 |

| Treatment with rt-PA | 458 | 84 | 13.88 | (9.06, 18.70) | < 0.001 | −2.949 | (−9.29, 3.39) | 0.362 | −16.828 | (−23.74, −9.92) | < 0.001 |

| Serum plasminogen levelc | 458 | 84 | 0.128 | (0.06, 0.19) | < 0.001 | −0.009 | (−0.08, 0.06) | 0.783 | −0.138 | (−0.21, −0.06) | < 0.001 |

| Platelet levelc | 458 | 84 | −0.069 | (−0.10, −0.04) | < 0.001 | −0.001 | (−0.04, 0.04) | 0.967 | 0.068 | (0.03, 0.11) | 0.002 |

Each patient had a specific spline knot to identify the deflection point in their lysis rate. Estimate is expressed as % of the IVH volume on the stability CT scan resolved per day.

Number of measurements across patients used in the model.

Variable was centered by its median before a cross product was obtained.

Abbreviations: IVH: intraventricular hemorrhage; CI: confidence interval; rt-PA: tissue plasminogen activator (any dose).

The effect of rt-PA and baseline plasminogen on estimated IVH resolution over time from this analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Estimated IVH clot volume remaining over time as a percentage of stability CT clot volume for placebo and rtPA patients by quartile of baseline serum plasminogen level.

The likelihood ratio test statistics comparing the quadratic and spline models with the linear model were highly significant (P<0.001 for both models), indicating that the spline and quadratic models do perform better than the linear model over the first 6 days after stability. The AIC values for the quadratic model (8150.641) and spline model (8028.537) suggest choosing the spline model. The spline model also provides an easier interpretability of the coefficients, and seems to represent a more biologically plausible model over longer time periods.

In a separate analysis of baseline CSF plasminogen levels in 40 patients (44 original; excluded because of assay uncertainty – 3 zeros, and 1 outlier), median CSF plasminogen level was 8 g/L (range: 1–28), representing 7.1% of median serum plasminogen (range: 0.01–24.9%). The correlation between baseline CSF plasminogen and baseline IVH volume was significant (Spearman’s rho = 0.447; P=0.003) whereas the correlations between serum and CSF plasminogen and between serum plasminogen and baseline IVH volume were not. A multivariate analysis of a spline model with log-transformed baseline CSF plasminogen in those treated with rt-PA showed a trend between lower CSF plasminogen and faster clot lysis rate: 2.6%/day for each 2-fold decrease in plasminogen (P=0.09).

Discussion

Factors Affecting IVH Clot Lysis: Main Results

Based on these clot lysis rates from the CLEAR IVH studies, predictors of faster IVH volume resolved per day over the first 6 days of treatment from clot stability were intraventricular rt-PA treatment, higher baseline serum plasminogen and lower baseline platelet count. Our initial hypothesis, that female gender would be associated with improved clot lysis rates in rt-PA treated patients with IVH, was not observed. Initial IVH volume and ipsilateral EVD placement relative to side of greatest IVH volume were associated with faster clot lysis in the univariate, but not in the multivariate analysis.

Fibrinolysis in IVH

Lysis of intraventricular clots could depend on the fibrinolytic activity of the CSF rather than the “fibrinolytic state of the circulation” (9). Normal CSF, however, contains very low levels of fibrinolytic enzymes, although fibrinolytic activity (as measured by fibrinogen, plasminogen and total protein) in both CSF and serum, is higher in acute brain injured states and in older compared with younger patients (10). Plasminogen is normally excluded from the CSF by the blood brain barrier due to its high molecular weight (92 kDa) (11). In a study of neonatal IVH, CSF plasminogen levels were only 0.55% of normal adult plasma (and only 2% of neonatal plasma), remained very low during the weeks following IVH, and were not significantly different from reference infants without IVH (12). Our findings of extremely low CSF:serum plasminogen ratios at baseline are consistent with these data. A relative deficiency of plasminogen at the thrombus site may explain the finding of only modest clot lysis despite high concentrations of plasminogen activator locally. The source of plasminogen in the CSF is likely twofold: from blood including the original hemorrhage, and production by microglial cells with diffusion across the inflamed ependymal lining of the ventricles (13,14). Low levels of CSF plasminogen after IVH may reflect that rt-PA has activated all available plasminogen. Baseline CSF plasminogen was positively correlated with stability IVH volume suggesting that more serum plasminogen is incorporated into larger clots. The finding that higher serum plasminogen and possibly lower CSF plasminogen at time of first dose of study agent were associated with faster clot lysis rates supports the hypothesis that high serum concentrations of plasminogen in the initial hemorrhage provide more substrate for the plasminogen-rt-PA interaction, but quickly becomes depleted. Whether lower CSF plasminogen is a marker of more effective clot lysis or a lack of substrate is unknown. This analysis was independent of treatment effect because no study agent had yet been administered at the time of plasminogen measurement. Serial plasminogen levels in both CSF and plasma would be required to better understand this issue.

With a deficiency of thrombolytic factors in CSF, it has been postulated that, in untreated patients, plasminogen and rt-PA within the clot are responsible for clot resolution and that this enzyme system is saturated by 24 to 48 hours leading to a constant percentage rate clot resolution thereafter (7). Naff et al found that during the first 24 to 48 hours of untreated IVH there was little if any clot resolution while a substantial number of clots expanded during this time. In our study, this early latency period was not observed most likely because the first CT scan used for the analysis occurred at least 6 hours after IVC placement and approximately 18 hours after the diagnostic CT scan. In Naff’s study the rate of clot resolution over the first 10 days was 10.8% per day. This compares reasonably well with the pre-spline 9.4% clot resolution rate in placebo patients in this study. In rt-PA treated patients, administering thrombolytic agents hastened early clot resolution by 14.6% /day over treatment by placebo to achieve an average rate of 24%/day. After the spline knot, in rt-PA treated patients, the rate of clot resolution significantly decreased (to 0.55%/day), either because the CSF plasminogen/rt-PA thrombolytic system became saturated or because many patients had stopped receiving intraventricular rt-PA due to radiographic clearing of blood from 3rd and 4th ventricles which prompted stopping study drug.

Implications of Clot Composition on IVH Lysis Rates

The finding that lower baseline platelet level is associated with faster clot lysis suggests that IVH clot composition influences clot dissolution independent of rt-PA effect. In the current understanding of fibrinolysis, plasminogen activation occurs on the clot surface and creates a lytic zone at the fluid solid interface which is propagated to the core of the clot (15). Dissolution of thrombus depends on diffusion and permeation which are affected by clot composition. Specifically fibrinogen to fibrin conversion results in a heterogeneous gel phase mesh to which platelet attachment via glycoprotein IIb/IIIa to fibrin increases fiber density in platelet-rich areas (16). Higher platelet concentration in clots is known to significantly reduce the rate of fibrinolysis under both static and flow conditions (17,18).

Initial Hypothesis

Our initial hypothesis, that female gender would be associated with improved clot lysis rates in rt-PA treated patients with IVH was not confirmed by these data. The only predictor related to female gender was initial IVH clot volumes which was significantly smaller in females. Quantitative MRI studies of elderly volunteers (mean age: 75 ± 5 years) report a difference in CSF volume of the lateral ventricles between genders of approximately 10 mL (greater in males) (19). It is arguable that the anatomic difference in normal ventricular size may not fully explain the 19 mL difference in median IVH volume between genders.

Limitations

Although the population size is small, this represents the largest comprehensive dataset of adult IVH analyzed to date and the effort to obtain a daily CT scans permitted a much more detailed examination of rate of clot resolution. Serial measurements of fibrinolytic factors would have been optimal in this study and are therefore under investigation in upcoming trials. Moreover, many other factors regulating fibrinolysis including plasminogen activation, fibrin and thrombus structure, and EVD positioning are not accounted for in this analysis. Based on the inclusion criteria, results from this study cannot be generalized to patients with IVH and ICH >30 ml, nor to patients whose clot volumes do not stabilize within 48 hours of diagnosis.

Conclusion

Future assessments of fibrinolysis in the cerebral ventricle will need to consider plasminogen availability and thrombus structure especially the impact of platelets. A better understanding of the factors regulating fibrinolysis in IVH could lead to patient-specific dose adjustments of fibrinolytic agents and possibly to novel delivery agents such as plasminogen. Optimizing plasminogen activation through either improved matching of thrombolytic dose to plasminogen availability and/or mechanical dissolution of clot to increase clot surface area may lead to faster clot lysis and removal while reducing risk of re-hemorrhage. If faster IVH removal translates into better clinical outcomes (the hypothesis of the ongoing CLEAR III IVH trial), then enhancing this process may improve recovery from severe IVH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the patients, families, and hospital colleagues who participated in the CLEAR Safety and CLEAR IVH trials and the following Data Safety Monitoring Board: Joseph P. Broderick, MD, Department of Neurology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; Robert J. Wityk, MD, Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported in part by the Eleanor Naylor Dana Fellowship (DFH and WCZ), American Academy of Neurology (WCZ), Office of Orphan Products Development, Food and Drug Administration FD-R-001693 (DFH, PK, KL) and FD-R 002018 (DFH, PK, KL), National Institutes of Health/NINDS grants U01NS062851 and RO1NS046309 (DFH, PK, KL), the Jeffry and Harriet Legum Endowment (DFH), the France Merrick Foundation Grant (DFH), and materials grants from Genentech, Inc.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration Information:

CLEAR IVH NCT00650858

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00650858?term=clear+ivh&rank=1

MISTIE NCT00224770

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=MISTIE

CLEAR III NCT00784134

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00784134?term=CLEAR+III&rank=1

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures

Dr. Hanley has received research support as PI of the CLEAR IVH trial.

References:

- 1.Pang D, Sclabassi RJ, Horton JA. Lysis of intraventricular blood clot with urokinase in a canine model: part 2: in vivo safety study of intraventricular urokinase. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang YV, Lin CW, Shen CC, Lai SC, Kuo JS. Tissue plasminogen activator for the treatment of intraventricular hematoma: the dose effect relationship. J Neurol Sci. 2002;202:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayfrank L, Lippitz B, Groth M, Bertalanffy H, Gilsbach JM. Effect of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator on clot lysis and ventricular dilatation in the treatment of severe intraventricular hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir. 1993;122:32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naff N, Williams M, Keyl PM, Tuhrim S, Bullock RM, Mayer S, et al. Low-dose rt-PA enhances clot resolution in brain hemorrhage: The intraventricular hemorrhage thrombolysis trial. Stroke. 2011. In-press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naff NJ, Hanley DF, Keyl PM, Tuhrim S, Kraut M, Bederson J, et al. Intraventricular thrombolysis speeds blood clot resolution: results of a randomized, double-blinded controlled clinical trial. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steiner L, Bergvall U, Zwetnow N. Quantitative estimation of intracerebral and intraventricular hematoma by computer tomography. Acta Radiol Suppl. 1975;346:143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naff NJ, Williams MA, Rigamonti D, Keyl PM, Hanley DF. Blood clot resolution in human cerebrospinal fluid: evidence of first-order kinetics. Neurosurgery.2001;49:614–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies. New York, NY: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takashima S, Koga M, Tanaka K. Fibrinolytic activity of human brain and cerebrospinal fluid. Br J Exp Pathol. 1969;50:533–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen AR. CNS fibrinolysis. a review of the literature with a pediatric emphasis. Pediatr Neurol. 1998;18:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu KK, Jacobsen CD, Hoak JC. Plasminogen in normal and abnormal human cerebrospinal fluid. Arch Neurol. 1973;28:64–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whilelaw A, Mowinckel MC, Abildgaard U. Low levels of plasminogen in cerebrospinal fluid after intraventricular hemorrhage: A limiting factor for clot lysis? Acta Paediatr. 1995;84:933–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajima K, Tauzaki N, Nagata K, Takemoto N, Kohsaka S. Production and secretion of plasminogen in cultured rat cell microglia. FEBS Lett. 1992;308:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakajima K, Nagata K, Hamanoue M, Takemoto N, Kohsaka S. Microglia derived elastase produces a low molecular-weight plasminogen that enhances neurite outgrowth in rat neocortical explant cultures. J Neurochem. 1993;61:2155–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolev K, Longstaff C, Machovich R. Fibrinolysis at the fluid-solid interface of thrombi. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents. 2005;3:341–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collet JP; Montalescot J; Lesty C; Weisel JW Circ. Res 2002;90:428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunitada S, FitzGerald GA, Fitzgerald DJ. Inhibition of clot lysis and decreased binding of tissue-type plasminogen activator as a consequence of clot retraction. Blood. 1992;79:1420–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komorowicz E, Kolev K, Léránt I, Machovich R. Flow rate-modulated dissolution of fibrin with clot-embedded and circulating proteases. Circ Res. 1998;82:1102–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coffey CE, Saxton JA, Ratcliff G, Bryan RN, Lucke JF. Relation of education to brain size in normal aging: Implications for the reserve hypothesis. Neurology. 1999;53:189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.