Abstract

Introduction:

Millions of patients take prescription medications each year for common urological conditions. Generic and brand-name drugs have widely divergent pricing despite similar therapeutic benefit and side effect profiles. We examined prescribing patterns across provider types for generic and brand-name drugs used to treat 3 common urological conditions, and estimated economic implications for Medicare Part D spending.

Methods:

We extracted 2014 prescription claims and payments from Medicare Part D and categorized oral medications used to treat 3 urological conditions, namely benign prostatic hyperplasia, erectile dysfunction and overactive bladder. We examined claims and payments for each medication among urologists and nonurologists. Lastly, we estimated potential savings by selecting a low cost or generic drug as a cost comparator for each class.

Results:

There were significant differences in prescribing patterns across these conditions, with urologists prescribing more brand-name and expensive medications (p <0.001). The total potential savings related to prescriptions of more expensive and nongeneric drugs in 2014 was $1 billion (benign prostatic hyperplasia $348,454,910, erectile dysfunction $10,211,914 and overactive bladder $698,130,833). These potential savings comprised 53% of the total spending for these medications in 2014.

Conclusions:

Within Medicare Part D the potential savings associated with generic substitution for higher cost and nongeneric drugs for 3 common urological conditions surpassed $1 billion, with urologists more likely to prescribe brand-name and more expensive drugs. Increasing low cost and generic drug use where available evidence of efficacy is equivocal represents a promising policy target to optimize prescription drug spending.

Keywords: Medicare Part D, prescription drugs, drug costs, cost savings, urology

The burden of urological diseases in the United States is immense, accounting for billions in health care expenditures annually.1 While most expenditures support physician visits and procedural fees, a substantial portion is attributable to prescription medications. Medicare Part D allows Medicare enrollees to purchase outpatient prescription drug coverage and in 2016 nearly 41 of the 57 million Americans enrolled in Medicare were also Part D beneficiaries. With estimated expenditures of $94 billion in 2017, Part D makes up nearly 7% of the global prescription drug market.2,3 Urologists, who devote nearly half of their visits to Medicare-age patients, are well suited to inform and influence Part D prescribing policies while maximizing value among an aging U.S. population.4,5

Prescription patterns for the management of common urological conditions have not been well elucidated. Lower cost, generic medications exist for many conditions but they may not always be prescribed over more expensive brand-name versions, despite similar effectiveness and adverse effect profiles.6,7 In fact, studies examining the use of statins and anticonvulsants have found that less expensive generic drugs often have better adherence, leading to fewer adverse events.8,9 Nonetheless, patients and providers may perceive generic medications as less effective, decreasing prescription rates and increasing costs.10–13 This difference is potentially magnified as Medicare Part D is prohibited from negotiating drug prices, unlike other federal programs (eg Veterans Health Administration and Medicaid).3 Brand-name prescriptions are a significant driver of regional cost variation, indicating unique opportunities to improve Medicare Part D value for urological care.14 In addition, patients may directly benefit from generic substitution via lower out-of-pocket costs.15

Given the range of medications available for common urological conditions, we explored variations in prescription rates and total expenditures for individual medications within Medicare Part D. We compared prescribing patterns of urologists to those of nonurologists to assess for patterns in the type of medications prescribed (low cost vs higher cost and generic vs brand-name medications). We then investigated potential savings opportunities related to higher cost medications. This work provides an estimation of cost savings if lower cost prescriptions were substituted among Medicare beneficiaries with common urological conditions.

Materials & Methods

Data Sources

We used the 2014 Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data: Part D Prescriber Public Use File available from CMS.16 This data set contains information on all prescription drug events for Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D, accounting for approximately 70% of all Medicare patients. Data are organized by NPI and drug name, and restricted to prescribers with a valid NPI during the year of study. Each record in the data set is a unique combination of NPI, drug name and generic name, and includes information on provider specialty, total number of Medicare Part D claims dispensed (including original prescriptions and refills), total drug cost and number of days’ supply dispensed. Total costs are based on amounts paid by Part D, beneficiaries, government subsidies and third party payers, and include ingredient cost, dispensing fees, sales tax and administration fees. Further discussion of the methodology and limitations of these data have been well described by CMS.17

Study Population

We generated a list of oral prescription medications for benign prostatic hyperplasia, erectile dysfunction and overactive bladder. We chose these conditions because they are managed by urologists and primary care providers, there is a range of medications and current practice guidelines do not suggest that a single medication is superior to others for a given condition.18–20 However, among OAB drugs longer acting formulations are generally preferred and treatment selection is guided by the goal of limiting side effects, which are common.

To focus on those medications driving cost differences we limited our analysis to medications with at least 1,000 claims among urologists and nonurologists, which captured 99% of claims across the medication classes examined. This yielded several medications for BPH, including terazosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin (brand-name and generic), alfuzosin (brand-name and generic), silodosin, finasteride, dutasteride and tamsulosin/dutasteride. Medications for ED included sildenafil, vardenafil and tadalafil, and for OAB the medications were oxybutynin, tolterodine (brand-name and generic), trospium, darifenacin, fesoterodine, solifenacin and mirabegron. We stratified medications by length of action where extended-release and long-acting versions were available.

We conducted a subset analysis restricted to urologist records given their role as subspecialist providers. Data sets were collapsed by drug name and summed to give total claims, day’s supply and cost for each medication. We then extracted records for the medications in our list. Values in the urologist-only data set were subtracted from the complete data set to obtain values for nonurologists.

Outcomes

Our 2 primary outcome measures were the distribution of prescriptions within each urological condition and their related costs. We hypothesized that urologists would have different prescribing patterns than nonurologists, possibly related to expertise, familiarity with newer brand-name medications, case complexity or other factors. We then examined total costs. To allow for comparison we divided the total cost by total days’ supply to yield a cost per day figure for each medication. We first assessed the added costs generated by prescriptions of brand-name drugs where an identical generic medication was available. We calculated the potential savings by multiplying the cost per day of the less expensive medication by total days’ supply of the more expensive medication and subtracting this from the total cost of the more expensive medication.

For our secondary outcomes we examined cost savings related to increased prescriptions of lower cost and generic medications for each condition. In each group we selected a low cost, gold standard medication based on specialist opinion, and performed cost calculations for the remaining medications compared to equivalent prescriptions of the gold standard to quantify the potential savings. For BPH we selected a standard for each of the 2 main classes of drugs, specifically finasteride for 5-alpha reductase inhibitors and tamsulosin for alpha-1 antagonists. For the brand-name combination of tamsulosin/dutasteride we calculated comparator cost using equivalent length prescriptions of tamsulosin and finasteride. Among OAB drugs we selected oxybutynin ER. Among ED medications there were no available generics so we selected the lowest cost medication, vardenafil. In calculating potential savings we excluded those medications that were less expensive than the comparator.

Statistical Analysis

We tested differences in prescriptions using chi-square tests with a 2-tailed significance level of 0.05. Data analyses were performed in Stata® 13. This study was determined “Not Regulated” by the University of Michigan internal review board since the research did not interact with nor obtain identifiable private information about human subjects.

Results

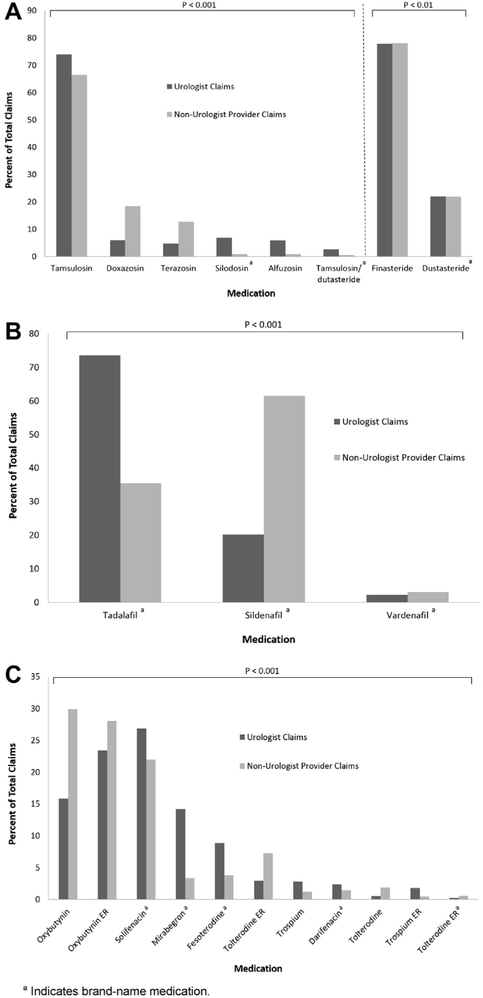

Among all Medicare Part D providers we identified 30,902,921 claims with a total cost of $1,988,184,607 (see table). There were significant differences in prescription patterns among urologists and nonurologist providers across BPH, ED and OAB (fig. 1). For BPH generic tamsulosin was the most commonly prescribed alpha-1 antagonist medication by both types of providers. However, nonurologists prescribed more doxazosin and terazosin, while nearly all prescriptions for silodosin, alfuzosin and tamsulosin/dutasteride were written by urologists. Among the 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, finasteride accounted for nearly 80% of prescriptions written by urologists and nonurologists. For OAB we found that nonurologists were more likely to prescribe oxybutynin or tolterodine, while urologists more likely to write prescriptions for solifenacin and other brand-name medications. While nonurologists wrote the majority of prescriptions for sildenafil to treat ED, urologists were more likely to prescribe tadalafil.

Table.

Overall claims, costs per day, payments and potential savings for all providers in the 2014 Medicare Part D Provider file for selected urological medications

| Total Claims | Cost/Day ($) | Total Payment ($) | Potential Savings ($)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia: | ||||

| Tamsulosin† | 11,685,671 | 0.49 | 272,159,867 | — |

| Finasteride† | 4,357,475 | 0.41 | 96,934,658 | — |

| Doxazosin | 2,675,599 | 0.64 | 85,149,342 | 20,214,395 |

| Terazosin‡ | 1,875,481 | 0.20 | 21,506,103 | — |

| Dutasteride§ | 1,228,151 | 4.59 | 248,567,328 | 226,415,280 |

| Silodosin§ | 371,318 | 4.97 | 75,469,772 | 68,218,394 |

| Alfuzosin | 336,448 | 0.62 | 10,594,369 | 2,389,479 |

| Tamsulosin/dutasteride§ | 177,141 | 4.61 | 34,609,473 | 27,956,318 |

| Tamsulosin§ | 8,812 | 7.56 | 2,236,066 | 2,093,388 |

| Alfuzosin§ | 2,951 |

12.69 | 1,213,514 |

1,167,656 |

| Totals | 22,719,047 | 848,440,492 | 348,454,910 | |

| Erectile dysfunction: | ||||

| Sildenafil§ | 139,631 | 5.13 | 19,322,544 | 4,410,225 |

| Tadalafil§ | 118,128 | 5.41 | 21,691,569 | 5,801,689 |

| Vardenafil†,§ | 7,672 |

3.96 | 903,739 |

— |

| Totals | 265,431 | 41,917,852 | 10,211,914 | |

| Overactive bladder: | ||||

| Oxybutynin ER† | 2,134,463 | 1.51 | 128,391,118 | — |

| Oxybutynin‡ | 2,104,026 | 0.81 | 69,772,973 | — |

| Solifenacin§ | 1,832,621 | 7.33 | 488,877,010 | 387,696,116 |

| Tolterodine ER | 495,103 | 5.78 | 101,778,596 | 75,158,201 |

| Mirabegron§ | 469,687 | 8.13 | 139,126,085 | 112,992,782 |

| Fesoterodine§ | 396,576 | 6.38 | 89,588,979 | 68,201,128 |

| Darifenacin§ | 129,444 | 6.86 | 29,012,619 | 22,579,355 |

| Trospium | 127,889 | 2.54 | 14,427,825 | 5,777,546 |

| Tolterodine | 122,889 | 4.13 | 14,993,612 | 9,513,222 |

| Trospium ER | 63,698 | 5.03 | 13,177,983 | 9,181,407 |

| Tolterodine ER§ | 42,047 |

7.96 | 8,679,463 |

7,031,076 |

| Totals | 7,918,443 | 1,097,826,263 | 698,130,833 | |

| Cumulative totals | 30,902,921 | 1,988,184,607 | 1,056,797,657 |

Calculated as total cost of drug X — (total supply of drug X * cost/day of comparator medication).

Reference medication for cost comparisons within each drug class or condition.

Medications that were less expensive than the selected comparator medication were excluded from savings calculations.

Brand name medication.

Figure 1.

Distribution of prescription claims within Medicare Part D among urologists and nonurologist providers of medications for BPH, ED and OAB. A, among BPH medications urologists were much more likely to prescribe silodosin, alfuzosin and tamsulosin/dutasteride, while non-urologists prescribed significantly more doxazosin and terazosin. Not shown in figure 1 for clarity, due to lower prescription rates, are brand-name tamsulosin (3,722 claims or 0.1% among urologists and 5,090 claims or 0.04% among nonurologists) and brand-name alfuzosin (1,757 claims or 0.04% among urologists and 1,194 claims or 0.01% among nonurologists). Urologists also prescribed more tamsulosin, while rates were overall quite similar between finasteride and dutasteride. B, among ED medications urologists were more likely to prescribe tadalafil while nonurologists were more likely to prescribe sildenafil, and rates of prescription for vardenafil were low in both groups. C, among OAB medications nonurologists were more likely to prescribe oxybutynin and tolterodine, while urologists had higher prescription rates for solifenacin, mirabegron, fesoterodine, trospium and darifenacin.

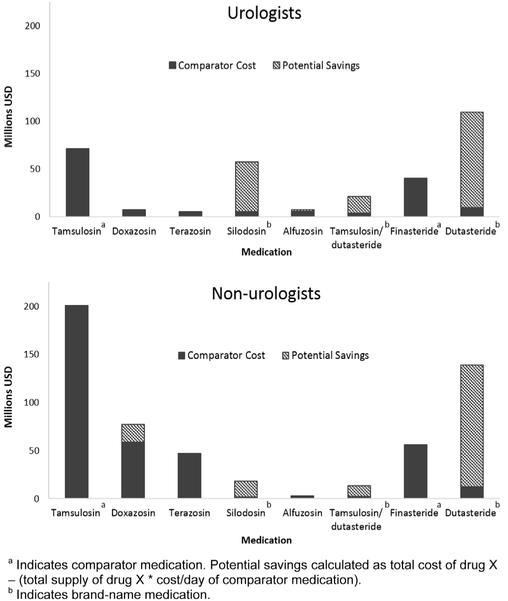

Cost comparisons among medications for the 3 conditions are illustrated in figures 2-4. For BPH medications, among alpha-1 antagonists the greatest potential savings were generated by silodosin ($52.0 million urologists, $16.2 million nonurologists), tamsulosin/dutasteride ($17.1 million urologists, $10.9 million nonurologists) and doxazosin ($1.5 million urologists, $18.8 million nonurologists) compared to tamsulosin (fig. 2). Among 5-alpha reductase medications large potential savings were generated by prescriptions of dutasteride ($100.1 million urologists, $126.3 million nonurologists) compared to finasteride. Total potential savings for BPH medications were $348.5 million ($174.2 million urologists, $174.3 million nonurologists).

Figure 2.

Cost comparisons between provider types for BPH medications. Significant sources of potential savings were silodosin, tamsulosin/dutasteride and dutasteride. Doxazosin was also important source of potential savings among nonurologists due to increased rate of prescription.

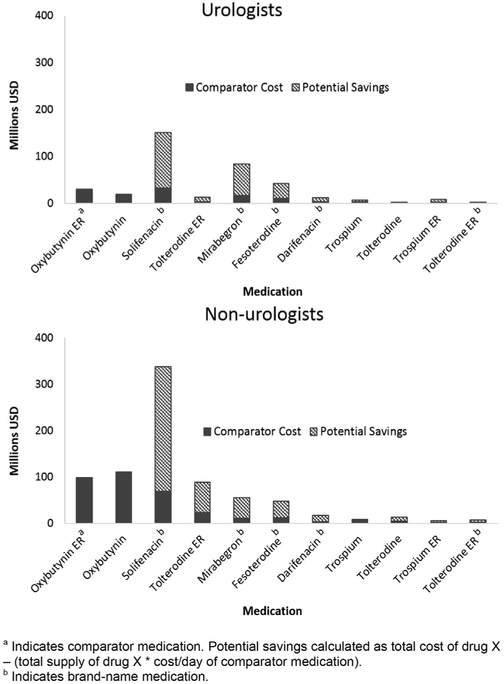

Figure 4.

Cost comparisons between provider types for OAB medications. Most significant source of potential savings by far across both types of providers was solifenacin. Other significant sources included mirabegron and fesoterodine. Tolterodine ER generated significant potential savings among nonurologists due to increased use (p <0.01).

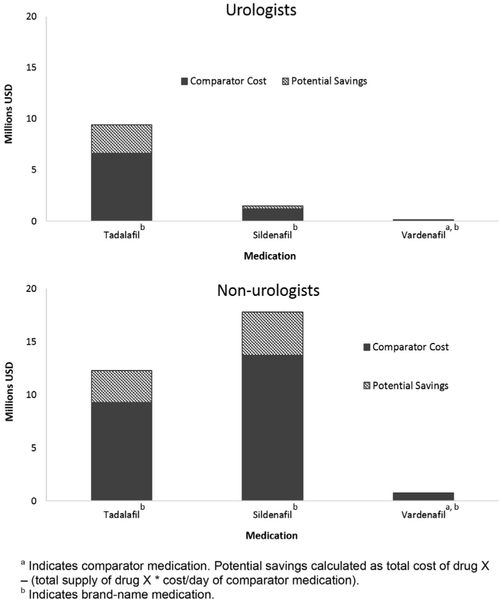

Sildenafil generated savings opportunities largely among nonurologist providers due to its increased use ($4.1 million), while tadalafil generated similar savings in both groups of prescribers treating ED ($2.8 million urologists, $3.0 million nonurologists) (fig. 3). The cumulative potential savings were lowest among ED medications at $10.2 million ($3.1 million urologists, $7.1 million nonurologists).

Figure 3.

Cost comparisons between provider types for ED medications. Tadalafil was important source of potential savings among urologists and nonurologists. Sildenafil also contributed significant potential savings among nonurologists, who prescribed it at greater rate.

Conversely, OAB drugs demonstrated the largest potential savings opportunity of $698.1 million ($248.4 million urologists, $449.7 million nonurologists) (fig. 4). This was largely driven by solifenacin ($119.2 million urologists, $268.5 million nonurologists), followed by mirabegron ($68.2 million urologists, $44.8 million nonurologists) and fesoterodine ($31.6 million urologists, $36.6 million nonurologists). Estimated savings of replacing all brand-name tolterodine ER prescriptions with the equivalent generic was $2.4 million ($0.4 million urologists, $2.0 million nonurologists).

The potential savings opportunities across all conditions exceeded $1 billion ($424.0 million urologists, $629.5 million nonurologists). These potential savings represented more than 50% of the total 2014 Medicare Part D expenditures for the medications examined.

Discussion

We identified $1 billion of potential savings opportunities in Medicare Part D related prescription spending across 3 urological conditions in 2014 and found that prescription patterns for these urological conditions varied significantly between urologists and other providers. Rates of brand-name prescriptions when a generic formulation was available were surprisingly low. A significant portion of these potential savings may be justified by the use of second line therapies or other patient characteristics. Urologists were more likely to prescribe nongeneric and more expensive medications compared to nonurologists, likely reflective of referral practices leading to increased use of second line medications as well as specialty specific familiarity with newer therapeutic options. However, it is unlikely that all nongeneric and expensive medications in these data represent second line prescriptions, and these findings suggest that given the calculated maximum savings of $1 billion, even small changes in practice patterns could result in significant savings to Medicare.

These findings build on prior work examining Medicare Part D spending among urologists, and are consistent with data from other fields suggesting suboptimal use of lower cost, generic prescription medications.21 A strength of our study is its focus on common urological conditions with sufficient numbers of roughly equivalent medications to allow for decreased costs without compromising patient care outcomes and satisfaction. Existing data and practice guidelines from the AUA do not suggest superiority of any medications we examined in this study. Among alpha-antagonists for BPH all are considered therapeutically equivalent options for management. This is also the case among the 2 available 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, one generic and one brand-name.18,22 These results offer a compelling reason to choose older, generic medications over newer, brand-name options. Similarly, among ED medications no single phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor has been proven to be superior to the others, although recent analyses suggest that sildenafil may be the most efficacious while tadalafil minimizes adverse effects.19,23,24 The balance of patient preference against cost may favor preference in this situation given the similar medication costs and lack of generic options.

Our findings regarding OAB management are perhaps the most nuanced among the 3 conditions. While efficacy data and guidelines do not indicate a superior medication, there are important differences in adverse effect profiles and a general progression from first line to subsequent treatments. 20,25–28 Anticholinergics can cause significant dry mouth and constipation, effects which may be worse among the older medications such as oxybutynin and tolterodine, as well as more severe effects including cognitive alterations or arrhythmias. However, extended-release formulations appear to attenuate these effects. Thus, in anticholinergic naive patients a low cost approach would be to initiate generic oxybutynin ER, with subsequent transition to an alternative if adverse effects become intolerable or efficacy is lacking. Mirabegron is unique in that its mechanism of action through agonism of the beta 3-adrenoceptor avoids most adverse effects associated with anticholinergics. Although AUA guidelines suggest mirabegron and anticholinergics may be used interchangeably, given that it remains under patent protection and is quite expensive, it could be reserved for patients for whom the drugs fail or who have contraindications to the use of anticholinergics.

Our study has several limitations. It is a cross-sectional analysis at the provider level and lacks specific patient information. Therefore, we are not able to determine if lower cost medications failed before patients were transitioned to more expensive options. However, published analyses examining referral bias have demonstrated that clinically significant differences in BPH symptom severity were absent between urologists and nonurologists, and that urologists tended to use more intensive treatment approaches even when patient factors were controlled.29, 30 The low rates of brand-name prescription when a directly comparable generic was available suggest that urologists and nonurologists do often seek to select a lower cost medication, but given the size of the study population it is likely that a significant proportion of brand-name claims were initial prescriptions within a given class. It may also be the case that specialists are too quick to escalate care to more expensive options. Furthermore, we do not know what proportion of patients treated by these providers had supplemental insurance coverage during the study period, which may defray the cost of brand-name medications. We also do not know to what extent the drugs used in this study were dictated by mandates from individual insurance providers.

In addition, we lacked data on the therapeutic indication for a given prescription, meaning that we could be capturing medications prescribed for nonurological conditions (eg alpha-1 antagonists prescribed for hypertension). However, this is not likely to represent a significant proportion of prescriptions.31 Also, although these records do include some provider data, they lack a robust set of covariates to facilitate assessment of predictors of prescription patterns among providers. Nonetheless, we believe these results show a generalized need for improvement across providers and specialties and may motivate further research into predictors of prescriber practice patterns. Also noteworthy is that these data reflect claims filled rather than actual prescriptions as written and, thus, reflect the distribution of medications dispensed after any therapeutic substitutions at the pharmacy level. This could potentially bias the findings in either direction, but it is unlikely that pharmacists would replace a generic medication with a high cost, brand-name substitute, Therefore, the numbers calculated here may be an underestimate of the potential savings at the prescriber level.

Cost data in this analysis are aggregate measurements that do not allow for a nuanced understanding of considerations such as variations in out-of-pocket costs as a driver of patient preference. In addition, these data do not capture factors such as direct and indirect remuneration fees or manufacturer rebates. As these fees are often calculated on a percentage basis they have a more significant effect in regard to the use of brand-name medications. However, from the standpoint of overall costs these data provide adequate information to assess relative contributions from medications in each class.

Lastly, the prescription drug market is an evolving environment as patents expire and new medications are brought to market. Generic dutasteride is now available to consumers and generic formulations of solifenacin and sildenafil are also expected to become available in the coming years. This will have significant effects on the marketplace for the medications examined in these data. However, the conclusion that small changes in practice could lead to significant savings across specialties remains unchanged.

Despite such limitations, our results have important implications for all stakeholders involved. Given the magnitude of potential savings observed in these data, policymakers and CMS could implement several approaches to increase value of care for these patients. These include required generic substitution and a managed formulary across all Medicare Part D plans, and individual payers could take similar cost saving approaches.3 While the choice of a specific medication is a shared decision between patient and provider, these results should encourage physicians to reflect on their own prescribing practices and consider which patients truly benefit from the added costs of brand-name medications. As for patients, they may benefit in the form of lower out-of-pocket costs.

Conclusions

Among Medicare Part D beneficiaries with common urological conditions, urologists were more likely to prescribe nongeneric medications than nonurologist providers, but potential savings opportunities exist regardless of specialty. Continued research should allow us to better understand the drivers of prescription patterns to allow for targeted interventions and system-wide improvement. As providers and policymakers continue to work toward lowering costs and increasing value, optimizing the use of generic medications should enable positive economic impacts without compromising quality of care or outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award 4TL1TR000435-10 (PSK), National Cancer Institute Advanced Training in Urologic Oncology Training Grant T32-CA180984 (TB), American Cancer Society (RSGI-13-323-01-CPHPS) (BKH), VA HSR&D Career Development Award – 2 (CDA 12–171) (TAS).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AUA

American Urological Association

- BPH

benign prostatic hyperplasia

- CMS

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

- ED

erectile dysfunction

- ER

extended-release

- NPI

National Provider Identifier

- OAB

overactive bladder

Footnotes

The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government

Financial interest and/or other relationship with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan.

Financial interest and/or other relationship with Michigan Pharmacists Association.

Contributor Information

Peter S. Kirk, Dow Division of Health Services Research, Department of Urology, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Tudor Borza, Dow Division of Health Services Research, Department of Urology, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

James M. Dupree, Dow Division of Health Services Research, Department of Urology, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

John T. Wei, Dow Division of Health Services Research, Department of Urology, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Chad Ellimoottil, Dow Division of Health Services Research, Department of Urology, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Megan E. V. Caram, Division of Hematology & Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Mary Burkhardt, University of Michigan Health System, Pharmacy Service, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Joel J. Heidelbaugh, Department of Family Medicine, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Brent K. Hollenbeck, Dow Division of Health Services Research, Department of Urology, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Ted A. Skolarus, Dow Division of Health Services Research, Department of Urology VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan, VA Health Services Research & Development Center for Clinical Management Research, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

References

- 1.Miller DC, Saigal CS and Litwin MS: The demographic burden of urologic diseases in America. Urol Clin North Am 2009; 36: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation: The Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit. Available at http://kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/the-medicare-prescription-drug-benefit-fact-sheet/. Accessed November 1, 2016.

- 3.Gagnon M and Wolfe S: Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Medicare Part D pays needlessly high brand-name drug prices compared with other OECD countries and with U.S. government programs. Policy Brief, Carleton University School of Public Policy and Administration, and Public Citizen Inc 2015. Available at https://carleton.ca/sppa/wp-content/uploads/Mirror-Mirror-Medicare-Part-D-Released.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drach GW and Griebling TL: Geriatric urology. J Am Geriatr Soc, suppl., 2003; 51: S355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suskind AM and Clemens JQ: Health policy 2016: implications for geriatric urology. Curr Opin Urol 2016; 26: 207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper-DeHoff RM and Elliott WJ: Generic drugs for hypertension: are they really equivalent? Curr Hypertens Rep 2013; 15: 340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhry NK, Denberg TD, Qaseem A et al. : Improving adherence to therapy and clinical outcomes while containing costs: opportunities from the greater use of generic medications: best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164: 41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagne JJ, Choudhry NK, Kesselheim AS et al. : Comparative effectiveness of generic and brand-name statins on patient outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161: 400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagne JJ, Kesselheim AS, Choudhry NK et al. : Comparative effectiveness of generic versus brand-name antiepileptic medications. Epilepsy Behav 2015; 52: 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrank WH, Cox ER, Fischer MA et al. : Patients’ perceptions of generic medications. Health Aff 2009; 28: 546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shrank WH, Liberman JN, Fischer MA et al. : Physician perceptions about generic drugs. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45: 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel RA, Walberg MP, Tong E et al. : Cost variability of suggested generic treatment alternatives under the Medicare Part D benefit. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2014; 20: 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gellad WF, Donohue JM, Zhao X et al. : Brand-name prescription drug use among Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D patients with diabetes: a national cohort comparison. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159: 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donohue JM, Morden NE, Gellad WF et al. : Sources of regional variation in Medicare Part D drug spending. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alston G and Hanrahan C: Can a pharmacist reduce annual costs for Medicare Part D enrollees? Consult Pharm 2011; 26: 182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Part D Prescriber Data CY 2014. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-DataZPartD2014.html. Accessed November 2016.

- 17.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Medicare Fee-For Service Provider Utilization & Payment Data Part D Prescriber Public Use File: A Methodological Overview. May 25, 2017. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Downloads/Prescriber_Methods.pdf. Accessed July 2017.

- 18.McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Avins AL et al. : American Urological Association Guideline: Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH). 2014. Available at https://www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/benign-prostatic-hyperplasia.cfm. Accessed December 2016.

- 19.Montague DK, Jarow JP, Broderick GA et al. : American Urological Association Guideline: The Management of Erectile Dysfunction. 2011. Available at https://www.auanet. org/education/guidelines/erectile-dysfunction.cfm. Accessed December 2016.

- 20.Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL et al. : Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Neurogenic Overactive Bladder (OAB) in Adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline. 2014. Available at https://www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/overactive-bladder.cfm. Accessed December 2016.

- 21.Dowling RA: Medicare Part D data reveal prescriber patterns. Urology Times 2016; 44: 20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahm P, Brasure M, MacDonald R et al. : Comparative effectiveness of newer medications for lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2017; 71: 570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsertsvadze A, Fink HA, Yazdi F et al. : Oral phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors and hormonal treatments for erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Staubli SE, Schneider MP et al. : Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors for the treatment of erectile dysfunction: a trade-off network meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2015; 68: 674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buser N, Ivic S, Kessler TM et al. : Efficacy and adverse events of antimuscarinics for treating overactive bladder: network meta-analyses. Eur Urol 2012; 62: 1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapple CR, Khullar V, Gabriel Z et al. : The effects of anti-muscarinic treatments in overactive bladder: an update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2008; 54: 543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madhuvrata P, Cody JD, Ellis G et al. : Which anticholinergic drug for overactive bladder symptoms in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 1: CD005429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novara G, Galfano A, Secco S et al. : A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with antimuscarinic drugs for overactive bladder. Eur Urol 2008; 54: 740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei JT, Miner MM, Steers WD et al. : Benign prostatic hyperplasia evaluation and management by urologists and primary care physicians: practice patterns from the observational BPH registry. J Urol 2011; 186: 971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollingsworth JM, Hollenbeck BK, Daignault S et al. : Differences in initial benign prostatic hyperplasia management between primary care physicians and urologists. J Urol 2009; 182: 2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann J: Choice of drug therapy in primary (essential) hypertension. Available at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/choice-of-drug-therapy-in-primary-essential-hypertension. Accessed January 2017.