Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to better understand the experience of coercive control as a type of IPV by examining associations between coercive control and women’s experiences of particular forms of violence, use of violence, and risk of future violence.

Method

As part of a larger research study, data were collected from 553 women patients at two hospital emergency departments who had experienced recent IPV and unhealthy drinking. Baseline assessments, including measures of coercive control, danger, and experience and use of psychological, physical, and sexual forms of IPV in the prior three months were analyzed.

Results

Women experiencing coercive control reported higher frequency of each form of IPV, and higher levels of danger, compared to women IPV survivors who were not experiencing coercive control. There was no statistically significant association between experience of coercive control and women’s use of psychological or sexual IPV; women who experienced coercive control were more likely to report using physical IPV than women who were not experiencing coercive control.

Conclusions

Findings contribute to knowledge on the relationship between coercive control and specific forms of violence against intimate partners. A primary contribution is the identification that women who experience coercive control may also use violence, indicating that a woman’s use of violence does not necessarily mean that she is not also experiencing severe and dangerous violence as well as coercive control. In fact, experience of coercive control may increase victims’ use of physical violence as a survival strategy.

Keywords: Intimate Partner Violence, Domestic Violence, Battering, Coercive Control, Use of Violence

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a widespread problem in the United States, with more than one in three women, and one in four men, reporting experience of rape, physical violence, or stalking from a current or former intimate partner in their lifetimes, according to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (Black et al., 2011). IPV is frequently treated as a singular category of experience but actually reflects a broad range of behaviors and contexts. There is variety in both forms (e.g., physical, psychological, sexual) and impacts of violence. A now abundant body of research indicates that impacts of IPV experience vary widely, largely due to the extent to which coercive control is present in the relationship (Ali, Dhingra, & McGarry; 2016; Johnson, 2008; Pence & Dasgupta, 2006). This study examines rates of violence and risk among women who experience IPV, comparing contexts with and without coercive control.

Coercive Control as a Type of IPV

Coercive control, also described as “intimate terrorism,” “coercive controlling violence” (Johnson, 2008) or “battering” (Davies & Lyon, 2014; Pence & Dasgupta, 2006; Smith, Thornton, DeVellis, Earp, & Coker, 2002), refers to a systematic pattern of behavior that establishes dominance over another person through intimidation, isolation, and terror-inducting violence or threats of violence (Dasgupta, 1999, 2002; Dutton & Goodman, 2005; Johnson, 2008; Pence & Dasgupta, 2006; Smith et al., 2002; Stark, 2007). Through systematic restrictions on freedom and independence, individuals experiencing coercive control are often isolated from friends, family, or other support systems; entrapped within the relationship due to financial, logistical, social, or emotional barriers to escaping; and fearful for not only their own safety but that of family members and other people in their network (Kelly & Johnson, 2008; Pence & Paymar, 1993; Stark, 2007). Coercive control can instill fear even in the absence of physical violence and can continue after the relationship ends (Crossman, Hardesty, & Raffaelli, 2016).

One of the most important advances in understanding IPV has been the shift towards typologies rather than conceptualizing it as a single broad phenomenon. Michael Johnson developed a typology, with categories and terminology that have evolved over time, that distinguishes types of IPV based on the presence or absence of coercive control (see Johnson 1995; Johnson 2008; Kelly & Johnson, 2008). In this model, “coercive controlling violence,” used to establish and maintain power and control over the partner, stands in contrast to the more commonly reported “situational couple violence,” referring to that which is used within the context of a specific conflict and without the motivation of power and control. Situational couple violence can, and often is, used by both individuals within a couple. Violence used by the recipient (victim) of coercive controlling violence, in self-defense or retaliation, is categorized as “violent resistance.” Finally, a relationship in which both individuals engage in coercive controlling violence would be labeled as having “mutual violent control;” however, there is controversy over the possibility and likelihood of such mutual coercive control given that the nature of coercive control indicates an imbalance of dominance in the relationship (Johnson, 2006; Ali et al., 2016).

Prior research has established several ways in which the experiences and impacts associated with coercive controlling violence differ from those associated with situational couple violence. First, the former tends to include more frequent and more severe acts of violence (Coker, Pope, Smith, Sanderson, & Hussey, 2001; Graham-Kevan & Archer, 2003; Hardesty, Crossman, Haselschwerdt, Raffaelli, Ogolsky, & Johnson, 2015; Johnson & Leone, 2005; Myhill 2015; Neilsen et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2002). Second, with coercive controlling violence, acts of severe physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, harassment, coercion, and control are more likely to continue and even escalate after partners separate given that separation is often experienced as a threat to the abusive partner’s control (Myhill 2015; Ornstein & Rickne, 2013). Third, compared with experience of situational couple violence, experience of coercive controlling violence is associated with elevated levels of trauma-associated mental health symptoms during and after the relationship and greater likelihood of feeling unsafe (Cook & Goodman, 2006; Dichter & Gelles, 2012).

In contrast to the increasingly robust literature on the nature, tactics, and impact of coercive control, relatively little is known about the use of violence among individuals experiencing coercive control. Understanding the relationship between experience of coercive control and use of violence is important given that use of violence – be it defensive or retaliatory – is one of the many safety strategies used by women experiencing IPV (Goodman, Dutton, Vankos, & Weinfurt, 2005; Hamby, 2014; Larance & Miller, 2016). The current study begins to address identified current knowledge gaps by comparing women who experienced coercive control to those who did not on levels of victimization, risk of future violence, and their own use of violence in the relationship. It is important to note that, although experience of coercive control is not necessarily exclusive to women (Black et al., 2011), research thus far has primarily focused on women as recipients of such violence. The few studies measuring coercive control experience among men have found rates of such experience relatively low compared to rates among women (Hester, Jones, Williamson, Fahmy, & Feder, 2017; Myhill, 2015; Tanha, Beck, Figueredo, & Raghavan, 2010). A better understanding of, and measurement tools to assess, men’s experience of coercive control is needed to conduct the kind of nuanced examination found in the current study with a male-identified population.

Use of Violence among Women who Experience Violence

Violence used against an intimate partner by women who are experiencing violence in the relationship stems from a variety of complex motivations. Women may use violence to resist coercion and control, as a survival or protective strategy, to defend themselves and others, to “assert their dignity,” to demonstrate anger or frustration, to retaliate, or as a result of other conflict or communication difficulties in the relationship (Hamby, 2014; Goodman et al., 2005; Larance & Miller, 2016; Miller & Meloy, 2006; Neal, Dixon, Edwards, & Gidyez, 2015; Swan & Snow, 2002). Additionally, women who are more socially disenfranchised (e.g., due to structural factors such as poverty, racism, xenophobia, and homophobia) may turn to violence in response to victimization because other options for self-preservation (e.g., calling the police, seeking shelter) are either not available to them (Goodmark, 2008; Hamby, 2014; Kennedy et al., 2012; Richie, 2012) or will cause new problems for them (Thomas, Goodman, & Putnins, 2015). Similarly, additional factors such as a woman’s substance use – which might be a result of IPV – can exacerbate women’s use of violence (Cafferky, Mendez, Anderson, & Stith, 2016) and hinder their help seeking efforts (Martin, Moracco, Chang, Council, & Dulli, 2008). Although violence may be used a means of protection and defense, women’s use of violence has been found to increase their risk for injury, sustained abuse, and an escalation in violence severity (Goodman et al., 2005; Johnson & Leone, 2005; Leonard, Winters, Kearns-Bodkin, Homish, & Kubiak, 2014).

Despite the growing attention to women’s use of violence as self-protection, there is insufficient knowledge about the frequency of women’s use of violence in the context of coercive control versus situational couple violence. Teasing apart both forms and types of IPV can better illuminate the diversity of IPV experiences and ways in which forms and types of violence intersect and interact.

Study Purpose and Hypotheses

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of coercive control as a type of IPV by comparing the frequency of specific forms of victimization (psychological, physical, sexual), use of violence, and risk of future violence (danger) between women who experienced IPV in relationships with coercive control and those who experienced IPV outside the context of coercive control. Building on the previous literature described above, we hypothesized:

-

H1

Women who have experienced coercive control will have higher frequency of IPV victimization (psychological, physical, and sexual) than women who have not experienced coercive control.

-

H2

Women who have experienced coercive control will report higher levels of danger than women who have not experienced coercive control.

-

H3

Women who have experienced coercive control will report lower rates of use of violence (psychological, physical, and sexual) against their partners than women who have not experienced coercive control, due to their increased experience of fear and decreased experience of power in the relationship.

Research Design and Methods

Data analyzed for this study were collected as part of a randomized clinical trial conducted in two academic urban emergency departments in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Rhodes et al., 2015). The study enrolled female emergency department patients aged 18–64 who were verbally and cognitively able to complete an English language interview. All trial participants experienced or used at least one act of physical, psychological, or sexual IPV, and had incidents of heavy drinking in the past three months, based on their own self report. Data from the baseline assessments were used for the analysis presented here.

Measurements

Demographic characteristics, including participant age, race/ethnicity, annual household income, formal education, and gender of intimate partner were self-reported.

Experience of coercive control (battering) was measured with the Women’s Experience with Battering (WEB) scale (Smith, Earp, & DeVellis, 1995). The WEB measures coercive control through the victim’s report of her experience of coercive control rather than the specific behaviors or acts of violence. The scale measures the effect of the experienced abuse and the level of fear by assessing the victim’s sense of powerlessness, lack of control, and susceptibility to physical violence in the relationship. Example items include: “He makes me feel unsafe, even in my own home;” “I feel owned and controlled by him;” “He can scare me without laying a hand on me.” Each item is scored using a 6-point Likert scale (ranging from 1= “Disagree Strongly” to 6= “Agree Strongly”) with a range of 10–60 and a cut-off of 20 or greater to meet the threshold for coercive control (Smith, Smith, & Earp, 1999). The scale has high internal consistency reliability and construct validity (Smith et al., 2002) and has strong sensitivity (79.8%) and specificity (99.4%; Coker et al., 2007). In this study, cronbach’s alpha was 0.94.

Presence of violent incidents (victimization and use of violence) in the relationship over the past three months was measured with the Short Form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2S; Straus & Douglas, 2004). The CTS2S, based on the longer 78-item version, has strong psychometric properties and is highly correlated with the CTS2 (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). The short form has 20 items, distributed over five subscales: physical assault, psychological aggression, sexual coercion, injury, and negotiation. The four-item negotiation subscale was not used in this study. The subscales measure the frequency of violent acts that the participant both received from her partner (“victimization”) and used against her partner (“use of violence”). Example items include: “I [my partner] punched or kicked or beat-up my partner [me]” (physical), “I [my partner] insulted or swore or shouted or yelled at my partner [me]” (psychological), “I [my partner] used force (like hitting, holding down, or using a weapon) to make my partner [me] have sex” (sexual). Response options included a range from 0 (never in the past three months) to 6 (more than 20 times in the past three months); with the higher scores indicating higher frequency of occurrence. The CTS2S demonstrates construct and discriminant validity (Straus & Douglas, 2004; Straus et al., 1996); Cronbach’s alpha for the CTS2S in this sample was 0.83.

Danger was measured using the Danger Assessment scale (DA; Campbell, 1995; Roehl, O’Sullivan, Webster, & Campbell, 2005), an empirically-derived and widely-used measure of risk of lethality and severe re-victimization. The DA contains 20 items (e.g., “Has the physical violence increased in severity or frequency over the past year?” “Does he own a gun?” “Do you have a child that is not his?”) with yes/no response options and produces a weighted score (more severe items given a higher point value), ranging from 0 to 39. The score is divided into four classifications of risk: Variable Danger (0–7), Elevated Danger (8–13), High Danger (14–17), and Extreme Danger (18+). Psychometric properties reveal strong validity, test-retest reliability ranging from .89 to .94, and Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .60 to .86 (Campbell, 1995; Roehl et al., 2005); in this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83.

Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4. Descriptive statistics, independent Wilcoxon rank-sum and chi-square analyses were run to assess differences between women experiencing IPV with coercive control and women experiencing IPV without coercive control on demographic and dependent variables. To compare the two groups (coercive control vs. no coercive control) on experiences of victimization and use of violence, we dichotomized the variables to identify whether the participant had or had not experienced or used each type of violence (psychological, physical, and sexual) in the past three months. Cases with missing data on key variables were excluded from the comparative analyses (described below).

We ran logistic regressions for each model to test for possible confounding of demographic characteristics. As there was no change in association between coercive control group (coercive control or no coercive control) and any of the dependent variables (victimization, danger, or use of violence) when adjusting for demographic characteristics, bivariate associations only are presented below.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 600 women enrolled in the original study, 553 had completed WEB scales and thus are included in this analysis. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 62, with a mean age of 32. The majority (72.5%) self-identified as Black or African American and not Hispanic or Latina (94.6%); more than half of all participants reported an annual household income of less than $20,000 and nearly half did not have formal education beyond the high school level. Data on partner gender were available for 499 participants (23 not asked and 31 had missing data for this variable). Among those participants, 42 (8.4%) reported that their partner was not male (40 reported a female partner and 2 reported partner gender as neither male nor female). Close to one-third (32.2%; n = 178) of the participants met the cut-off for coercive control with a score of 20 or higher on the WEB scale. Individuals who had experienced coercive control were more likely to report lower annual household incomes compared to the no coercive control group. The groups did not otherwise significantly differ by demographic characteristics. The coercive control group had higher median scores on the scales measuring victimization, use of violence, and danger (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Description: Individual and Relationship Factors

| Women who Experienced Coercive Control (n = 178) | Women who Did Not Experience Coercive Control (n = 375) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age – participant: median (IQR) | 27.7 (23.0–38.6) | 29.1 (24.2–41.1) | 0.054 |

| Race – participant: n (%)a | 0.069 | ||

| Black/African-American | 126 (71.6) | 275 (73.7) | |

| White/Caucasian | 21 (11.9) | 60 (16.1) | |

| Other | 29 (16.5) | 38 (10.2) | |

| Annual household income: n (%)b | 0.015 | ||

| < 10,000 | 64 (40.0) | 96 (28.2) | |

| 10,000–19,999 | 38 (23.8) | 80 (23.5) | |

| 20,000–49,999 | 45 (28.1) | 110 (32.3) | |

| ≥ 50,000 | 13 (8.1) | 55 (16.1) | |

| Level of education: n (%)c | 0.094 | ||

| No high school degree | 42 (23.7) | 68 (18.2) | |

| High school degree | 55 (31.1) | 96 (25.7) | |

| Some college | 57 (32.2) | 140 (37.4) | |

| College graduate + | 23 (13.0) | 70 (18.7) | |

| Partner gender: n (%)d | 0.511 | ||

| Male | 142 (92.8) | 315 (91.0) | |

| Non Male | 11 (7.2) | 31 (9.0) | |

| Violence and Danger: median (IQR) | |||

| Conflict Tactics Scales: Victimization | 6 (3–12) | 2 (0–4) | <.001 |

| Conflict Tactics Scales: Use of Violence | 6 (3–9) | 3 (2–6) | <.001 |

| Danger Assessment Scale | 12 (7–19) | 4 (1–7) | <.001 |

4 (0.7%) participants missing race data

52 (9.4%) participants missing income data

2 (0.4%) participants missing education data

Item asked of 530 participants; 31 (5.8%) participants missing data on partner gender

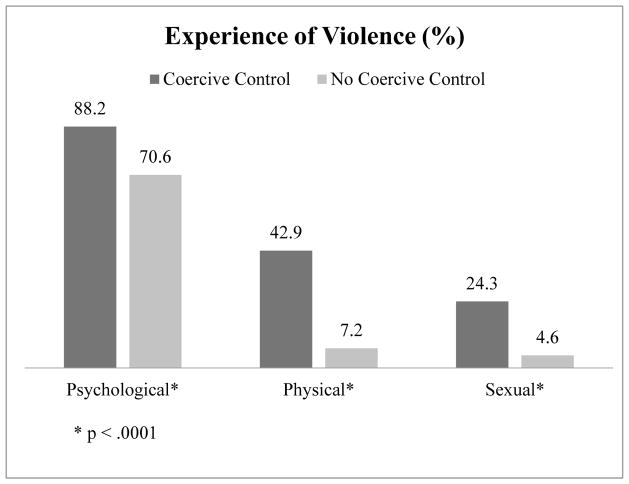

Victimization

Experience of psychological, physical, and sexual violence in the prior three months were all significantly (p<.0001) more frequent among the coercive control versus the no coercive control group (Figure 1), providing support for Hypothesis 1. A large majority of both the coercive control and no coercive control groups experienced any psychological violence (88.2% and 70.6%, respectively). Close to half (42.9%) of those who experienced coercive control also reported experience of physical violence, compared with just over 7% of those who did not experience coercive control. Nearly one-quarter of the participants in the coercive control group experienced sexual violence, compared with less than 5% of those in the no coercive control group. The women who had experienced coercive control reported higher rates of each individual victimization item compared to women who had not experienced coercive control (not shown in figure).

Figure 1.

Proportion of Coercively Controlled and Non-Coercively Controlled Women who Experienced Each Type of Violence

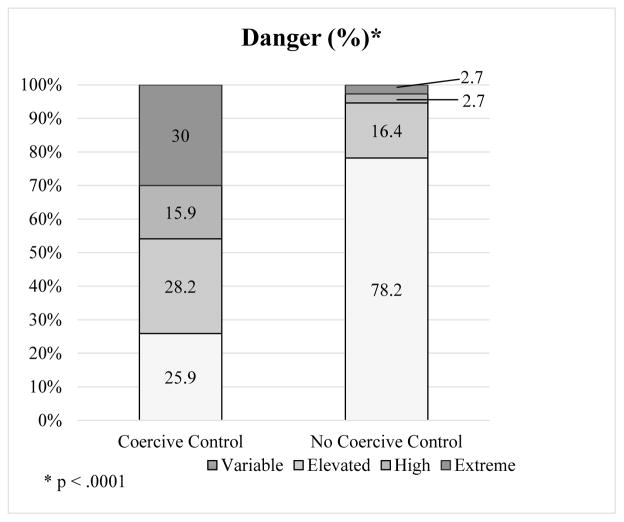

Danger

Women who had experienced coercive control were also at greater risk of re-victimization (danger), based on Danger Assessment scores, as was predicted with Hypothesis 2. The scores of women who experienced coercive control were statistically significantly higher than those who did not experience coercive control (Median [IQR]: 12 [7–19] vs. 4 [1–7]; p <.0001; r =0.52). The majority (78.2%) of women who did not experience coercive control was in the lowest level of danger, Variable Danger, and a small subset (2.7%) was in the highest level of danger, Extreme Danger (Figure 2). The scores of women who experienced coercive control were more evenly distributed across the four categories than those who did not experience coercive control, with 30% in the Extreme Danger category and 25.9% in the lowest risk category, Variable Danger. Among the individual Danger Assessment items, women experiencing coercive control were more likely to endorse each individual item than women not experiencing coercive control (all differences statistically significant at the .001 level except for “Does he own a gun?” and “Do you have a child that is not his?”; not shown in figure).

Figure 2.

Proportion of Coercively Controlled and Non-Coercively Controlled Women who Scored within Each Danger Category

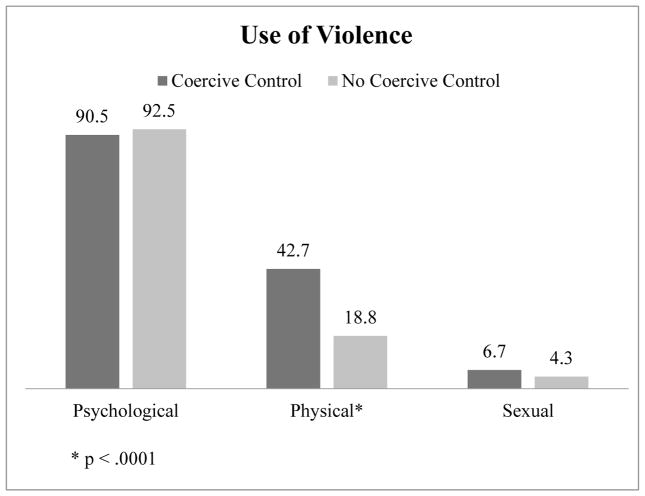

Use of Violence

Hypothesis 3, that women who have experienced coercive control would report using violence at lower rates than women who have not experienced coercive control, was not supported. As shown in Figure 3, the proportion of women who reported use of psychological or sexual violence did not differ significantly between the two groups. The overwhelming majority of both the coercive control and no coercive control groups reported use of psychological violence (90.5% and 92.5%, respectively). Less than 7% of the coercive control group and just over 4% of the no coercive control reported perpetrating sexual violence against their partners. However, there was a statistically significant difference (p<.01) between the two groups in use of physical violence with those who had experienced coercive control reporting more frequent use of physical violence against their partners (42.7% vs. 18.8%). Examination of individual use of violence items revealed higher proportions of women who had experienced coercive control than those who had not experienced coercive control reporting use of physical violence and one measure of psychological violence (“destroyed something belonging to my partner or threatened to hit my partner”); there were no statistically significant differences between the groups on the other psychological violence item (“insulted or swore or shouted or yelled at my partner”) or the sexual violence items (not shown in figure).

Figure 3.

Proportion of Coercively Controlled and Non-Coercively Controlled Women who Reported Using Each Type of Violence

Discussion

This study expands the current knowledge about coercive control in several important ways. First, findings provide additional evidence demonstrating a strong association between coercive control and frequency of victimization as well as with the risk of future victimization. Second, this study is one of a few to examine the use of violence by women experiencing coercive control. Third, by including and independently examining multiple forms of IPV (physical, sexual, and psychological violence), we are able to gain a more nuanced picture of IPV experience. Finally, whereas much of the research on coercive control has relied on measures of the partner’s controlling behaviors (Myhill 2015; Bubriski-McKenzie & Jasinski 2014; Hardesty et al 2015), we use the WEB scale (described in Methods) to assess coercive control based on the survivor’s experience of being controlled rather than on the behaviors identified. This is important because the construct of coercive control is based on the individual’s experience of being controlled (Dutton & Goodman, 2005) and it is possible that a behavior that may be intended as controlling (e.g., demanding a partner’s whereabouts or attempting to limit a partner’s freedom) may not have the effect of coercive control and, conversely, that behaviors that contribute to coercive control are not measured as such. Overall, a key finding of this study is that a woman’s use of violence in a relationship does not negate the possibility that she also experiences coercive control within that relationship.

Our finding that coercive control is associated with elevated rates of psychological, physical, and sexual violence victimization is consistent with prior research (e.g., Anderson, 2008; Coker et al., 2001; Myhill, 2015) and further highlights the variety of tactics and acts of violence used within this context. Crossman and Hardesty (2017) emphasize the importance of recognizing and assessing coercive control as an independent component of victimization, not dependent on co-occurrence with experience of physical violence. We note that the majority of the participants in this study who were identified as experiencing coercive control based on their experiences of their partner’s behaviors did not, in fact, also report experiencing physical violence in the most recent three months. That nearly one-quarter of the women experiencing coercive control also reported recent experience of sexual violence is significant given the profound adverse health and safety impacts associated with sexual violence from an intimate partner (Dichter & Gelles, 2012; Dichter, Marcus, Wagner, & Bonomi, 2014).

The finding of association between coercive control and risk of ongoing severe and lethal violence highlights the seriousness of this type of IPV, regardless of the other forms of violence experienced. That one in three women experiencing coercive control scored within the “extreme danger” category on the Danger Assessment scale indicates that this is a population that may require careful safety planning and protection. At the same time, however, the fact that nearly 22% of women in the no coercive control group scored higher than the minimal danger category (with nearly 3% in the highest danger category) is an indicator that it is also important to attend to risk among those reporting no coercive control.

Our data revealed no difference in frequency of women’s use of psychological (frequent) or sexual (infrequent) forms of violence by whether or not the women were experiencing coercive control, but there was a higher frequency of use of physical forms of violence among those experiencing coercive control. The findings regarding use of violence among women who experienced coercive control challenge a misleading stereotype of “battered women” as “pure victims” who do not use violence (Dunn, 2005; Goodmark, 2008). Legal scholars and advocates have noted that the battered woman stereotype leads to problematic assumptions that about women who have used violence (e.g., Schneider, 2000). Osthoff (2002) noted the concern that, “practitioners may not go so far as to conclude that the woman who used force is the batterer; he or she may simply conclude that, if the woman used violence, she could not be battered” (p. 1527). Alternatively, such an “either/or” assumption can lead to a woman being labeled as “mutually violent” or “mutually controlling” (Hamby, 2014), suggesting a symmetry of violence and discounting violence used as a protective strategy (Swan, Gambone, Caldwell, Sullivan, & Snow, 2008).

Use of violence among women experiencing coercive control may, in fact, reflect higher levels of fear, risk, and isolation leading to use of violence as a safety and survival strategy. Cook and Goodman (2006) found that women who experienced coercion and conflict in their relationships were considerably more likely to engage in formal and informal safety strategies compared to women who experienced conflict without coercion. Although the two groups in that study did not differ in their use of resistance-type strategies, this might have been because resistance was conceptualized to include violent and nonviolent strategies. It is also possible that the higher rates of physical violence use in our sample reflect observed demographic differences, specifically in terms of income. Women in the coercive control group were notably more economically disadvantaged. While the directionality between poverty and coercive control is unclear, poverty and discrimination can limit options for coping and help-seeking (Goodman, Smyth, Borges, & Singer; 2009; Kennedy et al., 2012). Women in the coercive control group, therefore, may have had fewer resources for escape and independence thereby leading to greater reliance on violence for self-protection.

Limitations

The data from this study are based on retrospective self-report from one member of a couple reporting on both her own and her partner’s violence. Self-report data are subject to misreporting and recall bias. Recall bias is typically associated with underreporting and as such our results may underestimate the degree of violence. This limitation is somewhat mitigated by the focus on IPV in the three months prior to the interview and by the use of valid and reliable self-report instruments to measure violent behavior in intimate relationships.

It is also important to note, however, that the validated measures used in this study are not without their own limitations. The use of the Conflict Tactics Scales to measure experience and use of violence is both widely implemented in IPV research and criticized largely for not including a measure of the context in which behaviors are used or their impact. Likewise, the use of a subjective measure of coercive control, focusing on the experience of the victim rather than the behavior of the perpetrator, is both a strength, as noted above, and potential a limitation as we do not know about the behaviors that contribute to the experience. We do not know from this study about the motivations or impacts of each partner’s use of violence and whether this context differed between those who did and did not experience coercive control. The Danger Assessment measure relies largely on objective indicators of risk (e.g., partner being unemployed or having a child not-in-common) and while having been validated as a measure of risk, is not a perfect predictor for each case. Therefore, while these tools have been found to be valid and reliable, and are widely used in research on violence against intimate partners, such measures cannot be perfect in their sensitivity and specificity, thus potentially misclassifying some people.

This study focuses on adult women who came to an urban emergency department for care, enrolled in a larger study, and also had reported unhealthy alcohol use in the prior three months. Research has not examined the role of survivors’ alcohol use in their experience of coercive control specifically; however, there is ample evidence that women’s alcohol use is associated with physical violence victimization and perpetration (Cafferky, Mendez, Anderson, & Stith, 2016; Devries et al., 2013; Foran & O’Leary, 2008). Thus, it is possible that survivors who engage in unhealthy alcohol use (versus those who do not) are more likely to respond to coercive control with violence.

The majority of study participants identified as Black or African American and not Hispanic/Latina and had relatively low annual household income; all participants were English-speaking; results cannot be confidently generalized to other populations of women who may have different experiences with coercive control and use of violence. Although we did not find statistically significant difference in experience of coercive control by participant race, it is important to note that African American women’s experiences of IPV occur within – and are informed by – a broader context of racism, sexism, and often classism; thus, their experiences of IPV and reactions to it may differ in many ways from those of their white counterparts (Al’Uqdah, Maxwell, & Hill, 2016; Richie, 2012; Taft, Bryant-Davis, Woodward, Tillman, & Torres, 2009). For example, research has found that African-American and Black women face barriers to seeking and receiving help from formal sources due to societal stigma, prejudice, and institutionalized discrimination (Bent-Goodley, 2016; Richie, 2012). In light of these differences, it is possible that one’s race affects their experiences of and responses to coercive control. Our sample, however, however, might not have been sufficiently diverse for such a finding to emerge. Furthermore, as our study focused exclusively on female participants, findings cannot speak to men’s experiences with and behaviors related to coercive control.

Research Implications

Study findings reinforce the importance of examining the construct and context of coercive control in studies of intimate partner violence. Limitations of the present study could be overcome in future research. In particular, it would be important to replicate this study with different populations of women, and with men, and in different settings. Additionally, further examination of possible differences in relationship dynamics among women (and men) in same-sex relationships is warranted. Finally, as noted above, research is needed to further examine the relationship between experiences of coercive control and unhealthy alcohol use and the ways in which experience or use of violence may differ by – or contribute to – heavy alcohol use behaviors.

Clinical and Policy Implications

In policy and practice as well as theory development, this study’s findings indicate that we must not overlook or minimize the impact of coercive control when working with women who use violence. It is important that women who use violence against a partner are not excluded from victim services or presumed to not experience victimization. Theories and typologies of IPV need to allow both the experience and use of violence to co-exist with careful attention to the context of these behaviors. Correspondingly, in clinical practice, we need to assess for both behaviors and context.

There is increasing attention to and advocacy around screening and assessing for individuals’ experiences of IPV in healthcare and social service settings in order to improve access to safety- and recovery-related services. There is little consensus about how best to screen for such experience and many of the existing screening tools inquire about specific acts of violence or an overall sense of safety. Given the increased victimization and risk associated with experience of coercive control, it may be useful to ask individuals about their experiences of coercive control and not just about behaviors that they have used or experienced. Furthermore, given that women use violence within a context of experiencing coercive control, it is important to ask about use of violence in a way that acknowledges possible victimization as well as agency and risk, and to work towards developing safety strategies that confer less risk.

Conclusions

This study advances our understanding of coercive control as a particular form of IPV, adding to the growing body of knowledge that supports a differentiated and multi-faceted view of IPV. Women who experience coercive control are likely to have also experienced violence victimization in various forms. Their victimization, however, does not indicate their passivity; they may also use violence against their partners. It is critical, therefore, that we do not view a woman’s use of violence as negating her own experience of being violently victimized and coercively controlled. The findings from this study support the arguments that we need to move away from thinking about victimization and agency as an either/or dichotomy (Dunn & Powell-Williams, 2007; Schneider, 2000).

Acknowledgments

Data analyzed for this study were collected as part of a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1R01AA018705-01A1). The authors acknowledge the contributions of Melissa Rodgers.

Footnotes

The contents of this article do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Contributor Information

Melissa E. Dichter, Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

Kristie A. Thomas, School of Social Work, Simmons College

Paul Crits-Christoph, Department of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Shannon N. Ogden, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

Karin V. Rhodes, Northwell Health Solutions, Office of Population Health Management, Hofstra Northwell Medical School

References

- Ali PA, Dhingra K, McGarry J. A literature review of intimate partner violence and its classifications. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2016;31:16–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.06.008 [Google Scholar]

- Al’Uqdah SN, Maxwell C, Hill N. Intimate partner violence in the African American community: Risk, theory, and interventions. Journal of Family Violence. 2016;31:877–884. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-016-9819-x [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KL. Is partner violence worse in the context of control? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2008;70:1157–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, et al. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bent-Goodley TB. Health disparities and violence against women: Why and how cultural and societal influences matter. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2016;8(2):90–104. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301160. http://doi.org/10.1177/1524838007301160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubriski-McKenzie A, Jasinki JL. Mental health effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence among Black and Hispanic women. Violence Against Women. 2014;19:1429–1448. doi: 10.1177/1077801213517515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferky BM, Mendez M, Anderson JR, Stith SM. Substance use and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Violence. 2016 Sep 15; http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/vio0000074 Advance online publication.

- Campbell JC. Assessing dangerousness: Violence by sexual offenders, batterers, and child abusers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Flerx VC, Smith PH, Whitaker DJ, Fadden MK, Williams M. Intimate partner violence incidence and continuation in a primary care screening program. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165:821–827. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Pope BO, Smith PH, Sanderson M, Hussey JR. Assessment of clinical partner violence screening tools. JAMWA. 2001;56:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SL, Goodman LA. Beyond frequency and severity: Development and validation of the brief coercion and conflict scales. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1050–1072. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossman KA, Hardesty JL. Placing coercive control at the center: What are the processes of coercive control and what makes control coercive? Psychology of Violence. 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/vio0000094 Advance online publication. Advance online publication.

- Crossman KA, Hardesty JL, Raffaelli M. “He could scare me without laying a hand on me”: Mothers’ experiences of nonviolent coercive control during marriage and after separation. Violence Against Women. 2016;22(4):454–473. doi: 10.1177/1077801215604744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta SD. Just like men? A critical view of violence by women. In: Shepard M, Pence E, editors. Coordinating community responses to domestic violence: Lessons from Duluth and beyond. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta SD. A framework for understanding women’s use of nonlethal violence in intimate heterosexual relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:12. [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Lyon E. Domestic violence advocacy: Complex lives/Difficult choices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Child JC, Bacchus LJ, Mak J, Falder G, Graham K, et al. Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2013;109(3):379–391. doi: 10.1111/add.12393. http://doi.org/10.1111/add.12393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Gelles RJ. Women’s perceptions of safety and risk following police intervention for intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2012;18:44–63. doi: 10.1177/1077801212437016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Marcus SC, Wagner C, Bonomi AE. Associations between psychological, physical, and sexual intimate partner violence and health outcomes among women veteran VA patients. Social Work in Mental Health. 2014;12:411–428. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JL. “Victims” and “survivors”: Emerging vocabularies of motive for “battered women who stay. Sociological Inquiry. 2005;75:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JL, Powell-Williams M. “Everybody makes choices”: Victim advocates and the social construction of battered women’s victimization and agency. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:977–1001. doi: 10.1177/1077801207305932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Goodman LA. Coercion in intimate partner violence: Toward a new conceptualization. Sex Roles. 2005;52:743–756. [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Dutton MA, Vankos N, Weinfurt K. Women’s resources and use of strategies as risk and protective factors for reabuse over time. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:311–336. doi: 10.1177/1077801204273297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Borges AM, Singer R. When crises collide: How intimate partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s mental health and coping? Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10:306–329. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339754. http://doi.org/10.1177/1524838009339754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodmark L. When is a battered woman not a battered woman? When she fights back. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 2008;20:75–129. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Kevan N, Archer J. Intimate terrorism and common couple violence: A test of Johnson’s predictions in four British samples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:1247–1270. doi: 10.1177/0886260503256656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby SL. Battered women’s protective strategies: Stronger than you know. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hardesty JL, Crossman KA, Haselschwerdt ML, Raffaelli M, Ogolsky BG, Johnson MP. Toward a standard approach to operationalizing coercive control and classifying violence types. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015;77:833–843. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12201. http://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester M, Jones C, Williamson E, Fahmy E, Feder G. Is it coercive controlling violence? A cross-sectional domestic violence and abuse survey of men attending general practice in England. Psychology of Violence. 2017;7:417–427. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/vio0000107 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Conflict and control: Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1003–1018. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. A typology of domestic violence: Intimate terrorism, violent resistance, and situational couple violence. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Leone JM. The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:322–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JB, Johnson MP. Differentiation among types of intimate partner violence: Research update and implications for interventions. Family Court Review. 2008;46:476–499. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AC, Adams A, Bybee D, Campbell R, Kubiak SP, Sullivan C. A model of sexually and physically victimized women’s process of attaining effective formal help over time: the role of social location, context, and intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;50:217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9494-x. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9494-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larance LY, Miller SL. In her own words: Women describe their use of force resulting in court-ordered intervention. Violence Against Women. 2016:1–24. doi: 10.1177/1077801216662340. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077801216662340 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leonard KE, Winters JJ, Kearns-Bodkin JN, Homish GG, Kubiak AJ. Dyadic patterns of intimate partner violence in early marriage. Psychology of Violence. 2014;4:384–398. doi: 10.1037/a0037483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Moracco KE, Chang JC, Council CL, Dulli LS. Substance Abuse Issues Among Women in Domestic Violence Programs: Findings from North Carolina. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(9):985–997. doi: 10.1177/1077801208322103. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077801208322103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Meloy M. Women’s use of force: Voices of women arrested for domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:89–115. doi: 10.1177/1077801205277356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myhill A. Measuring coercive control: What can we learn from national population surveys? Violence Against Women. 2015;21:355–375. doi: 10.1177/1077801214568032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal AM, Dixon KJ, Edwards KM, Gidyez CA. Why did she do it? College women’s motives for intimate partner violence perpetration. Partner Abuse. 2015;6:425–441. [Google Scholar]

- Neilsen SK, Hardesty JL, Raffaelli M. Exploring variations within situational couple violence and comparisons with coercive controlling violence and no violence/no control. Violence Against Women. 2016;22:206–224. doi: 10.1177/1077801215599842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orstein P, Rickne J. When does intimate partner violence continue after separation? Violence Against Women. 2013;19:617–633. doi: 10.1177/1077801213490560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osthoff S. But, Gertrude, I beg to differ, a hit is not a hit is not a hit: When battered women are arrested for assaulting their partners. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1521–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Pence E, Dasgupta SD. Re-examining ‘battering’: Are all acts of violence against intimate partners the same? Praxis International, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pence E, Paymar M. Education groups for men who batter: The Duluth model. New York: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Rodgers M, Sommers M, Hanlon A, Chittams J, Doyle A, … Crits-Christoph P. Brief motivational intervention for intimate partner violence and heavy drinking in the emergency department: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:466–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie B. Arrested justice: Black women, violence, and America’s prison nation. New York City, NY: NYU Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roehl J, O’Sullivan C, Webster D, Campbell J. Final Report to the U.S. Department of Justice. 2005. Intimate partner violence risk assessment validation study. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EM. Battered women and feminist lawmaking. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Earp JA, DeVellis R. Measuring battering: Development of the Women’s Experience with Battering (WEB) Scale. Women’s Health. 1995;1:273–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Smith JB, Earp JA. Beyond the measurement trap: A reconstructed conceptualization and measurement of battering. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1999;23:179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Thornton GE, DeVellis R, Earp J, Coker AL. A population-based study of the prevalence and distinctiveness of battering, physical assault, and sexual assault in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1208–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Stark E. Coercive control: How men entrap women in personal life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:507–520. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Gambone LJ, Caldwell JE, Sullivan TP, Snow DL. A review of research on women’s use of violence with male intimate partners. Violence and Victims. 2008;23(3):301–315. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Snow DL. A typology of women’s use of violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:286–319. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Bryant-Davis T, Woodward HE, Tillman S, Torres SE. Intimate partner violence against African American women: An examination of the socio-cultural context. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14(1):50–58. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2008.10.001 [Google Scholar]

- Tanha M, Beck CJA, Figueredo AJ, Raghavan C. Sex differences in intimate partner violence and the use of coercive control as a motivational factor for intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1836–1854. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KA, Goodman LA, Putnins S. “I have lost everything:” Trade-offs of seeking safety from intimate partner violence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85:170–180. doi: 10.1037/ort0000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]