Abstract

Purpose

The most prevalent intervention for localized prostate cancer (pca) is radical prostatectomy (rp), which has a 10-year relative survival rate of more than 90%. The improved survival rate has led to a focus on reducing the burden of treatment-related morbidity and improving the patient and partner survivorship experience. Post-rp sexual dysfunction (sdf) has received significant attention, given its substantial effect on patient and partner health-related quality of life. Accordingly, there is a need for sdf treatment to be a fundamental component of pca survivorship programming.

Methods

Most research about the treatment of post-rp sdf involves biomedical interventions for erectile dysfunction (ed). Although findings support the effectiveness of pro-erectile agents and devices, most patients discontinue use of such aids within 1 year after their rp. Because side effects of pro-erectile treatment have proved to be inadequate in explaining the gap between efficacy and ongoing use, current research focuses on a biopsychosocial perspective of ed. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of literature describing the components of a biopsychosocial program designed for the post-rp population and their partners.

Results

In this paper, we detail the development of the Prostate Cancer Rehabilitation Clinic (pcrc), which emphasizes multidisciplinary intervention teams, active participation by the partner, and a broad-spectrum medical, psychological, and interpersonal approach.

Conclusions

The goal of the pcrc is to help patients and their partners achieve optimal sexual health and couple intimacy after rp, and to help design cost-effective and beneficial rehabilitation programs.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, sexual dysfunction, rehabilitation, biospsychosocial approaches

INTRODUCTION

Apart from non-melanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer (pca) is the most common type of cancer in North American men. Coupled with 10-year relative survival rates approaching 98%1, statistics suggest that, in large proportion, pca survivors require post-treatment survivorship care. The most common intervention for localized pca is radical prostatectomy (rp)2, which continues to demonstrate effectiveness in long-term cancer control3. Although survival rates are remarkable, and most patients live healthy lives for many years after rp, most patients experience sexual dysfunction (sdf) as a result of their pca treatment.

Erectile dysfunction (ed) has been shown to affect 26%–100% of men after rp4. A recent investigation into predictors of ed showed that up to 60% of men with pre-rp erectile function (that is, firm enough for penetration) report ed at 2 years after rp5. The period required for recovery of erectile function after surgery is suggested to vary in the range of 6–48 months6. However, in a survey of 1213 patients 5 years after rp for pca, only 28% reported having an erection firm enough for penetration. Moreover, despite trending improvements in sexual performance 2–5 years after rp, more than three quarters of the patients found their sdf to be distressing7.

Investigation into health-related quality of life (hrqol) for patients 1 year after rp has shown that more men are concerned with sdf than with the possibility of a cancer recurrence8. The persistence of sdf side effects after rp can greatly interfere with the survivorship experience of pca patients and can result in significant reductions in their hrqol9–11. Compared with healthy age-matched controls, pca patients not only experience distressing physical side effects after rp, but also report significantly lower sexual confidence and sexual intimacy with their partners, a greater level of anxiety relating to sexual penetration, and a diminished sense of masculinity and self-confidence regarding their sexual abilities after treatment12.

Research has further revealed that the partners of post-rp patients can suffer from increased stress and lower marital intimacy. Partners worry about the patient’s health and about being left alone13. Fear of burdening the patient means that those concerns are often not communicated by the partner. Moreover, patient sdf after rp is negatively associated with partner marital adjustment and positively associated with partner experience of stress14. Despite the challenges of sdf, couples who report good communication in their relationship experience better marital adjustment overall14, which underscores the need for the partner’s participation in comprehensive or tailored survivorship care. Moreover, the involvement of partners in rehabilitative programs can potentially improve partner well-being and the likelihood of sexual rehabilitation success for men after rp15.

Recognition of the physical and psychological changes that attend rp and their implications for patient and partner hrqol has led many physicians to develop programs to treat sdf after rp16. Similarly, a consensus statement from the International Consultation on Sexual Medicine has outlined 5 approaches to physiologic rehabilitation: phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (pde5is), intracavernosal injections, intra-urethral alprostadil, vacuum erection devices, and neuromodulatory agents. However, evidence to support any specific rehabilitation paradigms is currently absent17. Research examining the use of pro-erectile agents and devices after rp has shown that, despite reports of the effectiveness of sexual aids, patients motivated to maintain sexual functioning before rp often fail to initiate the use of pro-erectile agents and devices after rp18. Furthermore, 30%–73% of patients initiating treatment after rp eventually discontinue the use of sexual aids18,19. Reasons for the discontinuation of pro-erectile agents and devices include loss of interest in sex, insufficient erection, and urethral pain and burning10.

An interview study exploring satisfaction in 320 patients with ed after rp and their partners showed that, even though most patients sought help to improve their sexual difficulties, only 20% were happy with their sexual functioning at the time of the interview15. Additional research similarly suggests that, despite attempts to use sexual aids, only 30%–62% of men remain sexually active or satisfied with their current sexual functioning 1–5 years after rp20,21. Those low rates of success in long-term sdf treatment suggest that physiologic treatments alone, such as sexual aids, are a necessary but insufficient step to long-term satisfaction and sexual rehabilitation. Experts in the field have therefore suggested that the introduction of psychological counselling might improve patient acceptance and adherence to pro-erectile agents and devices and also couple satisfaction17,22.

In contrast with the abundance of literature describing biomedical treatments for ed23,24, only a few studies involving pca survivors have evaluated psychosocial interventions that focus on ed. Nonetheless, interventions that target sdf and ed show promising results. Davison et al.25 evaluated a sexual rehabilitation program for men recovering from rp. In that study, patients were provided with information pertaining to available erectile aids and how to select the most appropriate ones. To enhance their sexual experiences, patients were also counselled on ways to adjust to sexual changes. Compared with baseline, patient levels of erectile function, orgasmic function, penetration, and overall satisfaction were significantly greater 4 months after the consultations. Similarly, Titta et al.22 randomly assigned 57 Italian men to one of two groups: a control group (n = 28) whose members received intracavernosal injections of prostaglandin E1, and an experimental group (n = 29) whose members received the injections and sexual counselling. After 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18 months, the rates of orgasmic function, sexual desire, sexual satisfaction, and overall satisfaction were significantly higher, and the rate of drop-out from the intervention was significantly lower, in the experimental group compared with the control group26,27.

Researchers, recognizing the importance of the partner in pca survivorship programming, have designed couple-centric psychosocial interventions. Canada and Schover28 evaluated an intervention meant to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after pca treatment. It included 4 education sessions about the sexual impact of the surgery and the various medical treatments for ed. Skills training was provided to improve sexual communication and general communication for the couple. In addition, cognitive–behavioral techniques addressed negative beliefs about cancer and sexuality. The researchers found that sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction in both the patient and his partner improved significantly after the intervention. In addition, once patients had more information about medical treatments for ed, their likelihood of using sexual aids increased significantly. However, despite initial improvements, sexual satisfaction returned to baseline 6 months after the intervention was completed. Further studies making use of psychological interventions to improve sexual functioning in pca patients and their partners have also been shown to improve hrqol even in cases in which support was provided over the telephone29 or a computer30,31.

Initial studies addressing the gap between the efficacy of pro-erectile agents and devices, their ongoing use, and improvements in patient and partner hrqol provide support for biopsychosocial programming designed to help pca patients and their partners. Despite growing enthusiasm for that approach on the part of pca survivorship experts, the literature lacks descriptions of systematic, longitudinal biopsychosocial programming designed for the post-rp population. In the present paper, we detail the development and implementation of the Prostate Cancer Rehabilitation Clinic (pcrc), a biopsychosocial sexual health rehabilitation clinic that emphasizes multidisciplinary intervention teams, the active participation of the partner, and a broad-spectrum medical, psychological, and interpersonal approach. The goals of the pcrc are to help patients and their partners achieve optimal sexual health and couple intimacy after rp.

THE PCRC

In 2009, the pcrc was made available to all men who consented to a rp at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Ontario. The pcrc format and content were informed by relevant scientific literature and the findings of a qualitative interview study, performed by the authors, explicating the post-rp effects of sdf on the patient, partner, and couple. The study helped to identify the sources of patient and partner distress related to sdf after rp, the reasons for avoiding or rejecting the use of sexual aids, and factors that assist couples in adapting to changes in sexual functioning32. Each component of the pcrc undergoes regular evaluation (data monitoring and participant feedback) and alignment to the developing scientific literature to ensure that the pcrc continues to evolve to adequately address participant concerns related to sdf.

Personnel and Staffing

The pcrc is staffed by an interprofessional team that includes urologists, uro-oncologists, sexual health counsellors, psychologists, a nurse, researchers, a clerk, and a volunteer. A urologist or a nurse specializing in uro-oncology patient care oversees the physical health of the patients, and a clinical psychologist manages the clinical and research agendas. The sexual health counsellors are psychology residents who have completed coursework in sexual health and cancer (for example, ipode and sharetraining)33,34. Additionally, to reinforce “real world” experience, the sexual health counsellors shadow and are shadowed for several months by senior pcrc staff.

Clinic Goals

The goals of the pcrc are to improve sexual functioning and to support the maintenance of intimacy after rp. Those goals are addressed by two complementary program components:

▪ A biomedical component (erectile rehabilitation) focuses on the long-term return of erectile functioning firm enough for penetration with or without erectile agents and devices, and the assessment and treatment of other sexual health concerns including climacturia, dysorgasmia (painful orgasms), and changes in penile size and shape.

▪ A psychosocial component (intimacy maintenance) involves the maintenance or restoration of the couple’s sexual activity and intimacy through adaptation to the ongoing use of pro-erectile therapy or adaptation to satisfying non-penetrative sexual activity, and intimacy counselling.

Referral Process

The pcrc is introduced to the patient and his partner preoperatively in an effort to ensure that the patient experiences continuity of care during the pre- to post-surgery transition. At the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, all patients consenting to surgery receive a preoperative teaching appointment with the Urology Clinical Coordinator, who provides teaching and counselling about treatment-related side effects. During the preoperative appointment, the coordinator informs the man about the pcrc. Men who indicate interest are provided with a referral for a pcrc appointment at 6–8 weeks after their rp.

Key to the integration between uro-oncologist care and pcrc follow-up care is the successful transfer of patient and partner sexual health care to the pcrc. Since 2009, we have therefore collected pcrc patient uptake data. As a result of that standardization, we successfully documented interest in the clinic for 99% of eligible patients. The patient tracking has helped to advance an understanding of the hurdles to transferring care to the pcrc and has enabled appropriate adjustments that aim to ensure the best possible uptake. Initially, transfer of patients relied on self-identification and therefore resulted in a small fraction of eligible patients attending the pcrc. In 2011, in an effort to increase successful transfer of care, the pcrc was integrated as part of usual care in post-rp management. That initiative ensured that, during their preoperative appointment, men were informed that they would receive notification of an initial appointment in the pcrc 6–8 weeks after their rp. The inclusion of the pcrc as part of usual care was an effort to normalize rehabilitative treatment and to overcome patient non-involvement because of stigma related to sexual dysfunction and cancer35.

Of the approximately 330 patients undergoing rp at Princess Margaret annually, 60% in 2011 and 66% in 2012 showed interest in participating in the pcrc. Encouragingly, 96% of the patients expressing intention to attend the pcrc actually presented to the clinic. The reasons patients provided for declining to participate included not being sexually active (62%), living far from the hospital (13%), lack of interest (10%), and other (15%—for example, scheduling conflicts and requests to delay participation because of a wish to prioritize recovery from the cancer diagnosis and treatment). Patients are encouraged to bring their partners along for the clinic visits, and 62% of the participating patients attended at least 1 clinic visit with their partner.

Assessment

During the initial pcrc appointment (3–4 months after the rp), a sexual health counsellor conducts a brief, structured clinical interview to determine the patient’s current and past sexual functioning. Patients are assessed for pre-rp erectile function and use of pro-erectile therapies, post-rp erectile function and bother, post-rp use of pro-erectile therapies, urinary dysfunction and bother, quality of orgasm and bother, climacturia and bother, changes in penis shape or size and bother, couple communication and intimacy and bother, and comorbidities and medications that might affect biomedical treatment recommendations. The assessment also includes a discussion about the sexual health values and goals of the patient or couple and specific sexual health concerns of the partner. The assessment as a whole is used to develop a personalized biopsychosocial treatment plan. Additionally, during follow-up pcrc appointments, sexual health counsellors continue to assess sexual activity engagement and, where appropriate, the effectiveness, acceptance, and enablers of and barriers to ongoing use of pro-erectile therapy. Finally, patients and partners are asked to complete a battery of patient-reported outcomes (pros) at each appointment. The pros are used to measure the effectiveness of the pcrc intervention and to produce quality assurance reports (see Table I for the pros used).

TABLE I.

Patient reported outcomes

| Questionnaire | Patient | Partner | Appointment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Single | Coupled | Female | Male | Pre-op | 6–8 Weeks |

3–4 Months |

7–8 Months |

12–13 Months |

17–18 Months |

22–24 Months |

|

| 1 Demographics (patient) | X | X | X | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 2 Demographics (partner) | X | X | X | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 3 Sexual Health Inventory for Mena | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| 4 Female Sexual Function Index37 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 5 EDITSb | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| 6 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale39 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

|

| |||||||||||

| 7 Miller Social Intimacy Scale40 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

|

| |||||||||||

| 8 Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite41 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| 9 Satisfaction questionnaire | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

Intervention

The pcrc provides both biomedical and psychosocial support for sdf.

Biomedical Component

Historically, the biomedical approach to improving ed after rp involved penile rehabilitation, which is defined as offering intervention for ed before or after pca treatment (or both) to achieve a return of natural erectile functioning similar to that achieved before the rp42,43. The pcrc uses a broader biomedical perspective: erectile rehabilitation focuses on the long-term return of erectile functioning firm enough for penetration with or without the use of erectile agents or devices. Both strategies involve the use of pro-erectile agents or devices to promote the oxygenation of penile tissue so as to reduce the likelihood of structural damage44. However, unlike penile rehabilitation, erectile rehabilitation focuses on helping patients or couples integrate pro-erectile agents into their sexual activity during their recovery trajectory after rp. The process helps to ensure that patients continue to engage in the use of pde5is in the later months of recovery (that is, 6–24 months after rp), when, compared with non-use, the use of pde5is is more likely to improve erectile function outcomes45,46. The erectile rehabilitation process allows for the likelihood that desired outcomes will be achieved at a higher rate in the long term, improving patient self-esteem and maintaining patient–partner intimacy. In that regard, patients in the pcrc are recommended to attempt sexual activity (penetrative or non-penetrative, self-stimulation or with partner) at least weekly, combined with initiation of pro-erectile therapy at 6–8 weeks after the rp.

Our erectile rehabilitation algorithm is personalized to the goals of the patient or couple related to

▪ the achievement of firm erections within weeks of rp or to wait until further neural function returns;

▪ the use of medications or non-medication pro-erectile approaches; and

▪ attempts at sexual activity with pro-erectile therapy or to engage in non-penetration-based sexual activity.

The resulting treatment plan and therapeutic prescription account for patient–partner preference through medical prescription according to effectiveness, balanced by invasiveness and patient desire or tolerance, with or without psychoeducation methods to achieve sexual satisfaction through non-penetrative processes. For example, intracavernosal injection might be prescribed to patients who desire upfront erections. Patients who are willing to forgo firm erections early in their recovery in favour of promoting the oxygenation of penile tissue might be prescribed pde5is. Similarly, for patients who are not interested in taking medication, a vacuum erection device might be prescribed; and for patients who are not focused on penetrative sex, sensate focus exercises might be recommended47. In all cases, patients receive relevant instruction during individualized physician and counsellor training for the use of pro-erectile therapies (including intracavernosal injection, alprostadil, vacuum erection device, and pde5is) and non-penetrative sexual practices.

Psychosocial Component

The primary goal of the psychosocial component is to support maintenance of intimacy, pro-erectile therapy use, and regular satisfying sexual activity, whether penetration- or non-penetration-based. The core topics include education about and normalization of sexual health rehabilitation, post-rp response expectation, intimacy and passion, challenges to naturalness and spontaneity, adaptation to sexual response changes, performance anxiety, masculinity, grief and loss, partner concerns, communication and intimacy, importance of orgasms, sensate focus, sexual desire, adaptation to long-term use of pro-erectile therapy, and enjoyment of non-penetrative sexual activity. As well, the psychosocial treatment protocol allows for personalization of the treatment based on the patient’s relationship status (single or coupled) and sexual orientation. As an example, patients who are single are offered guidance and recommendations about strategies for disclosure of the pca diagnosis and treatment, and the resulting ed. Similarly, psychoeducation is offered to gay patients about the potential effect of sexual response changes corresponding to top, bottom, or versatile sexual positions.

Clinic Visits: Timing and Content

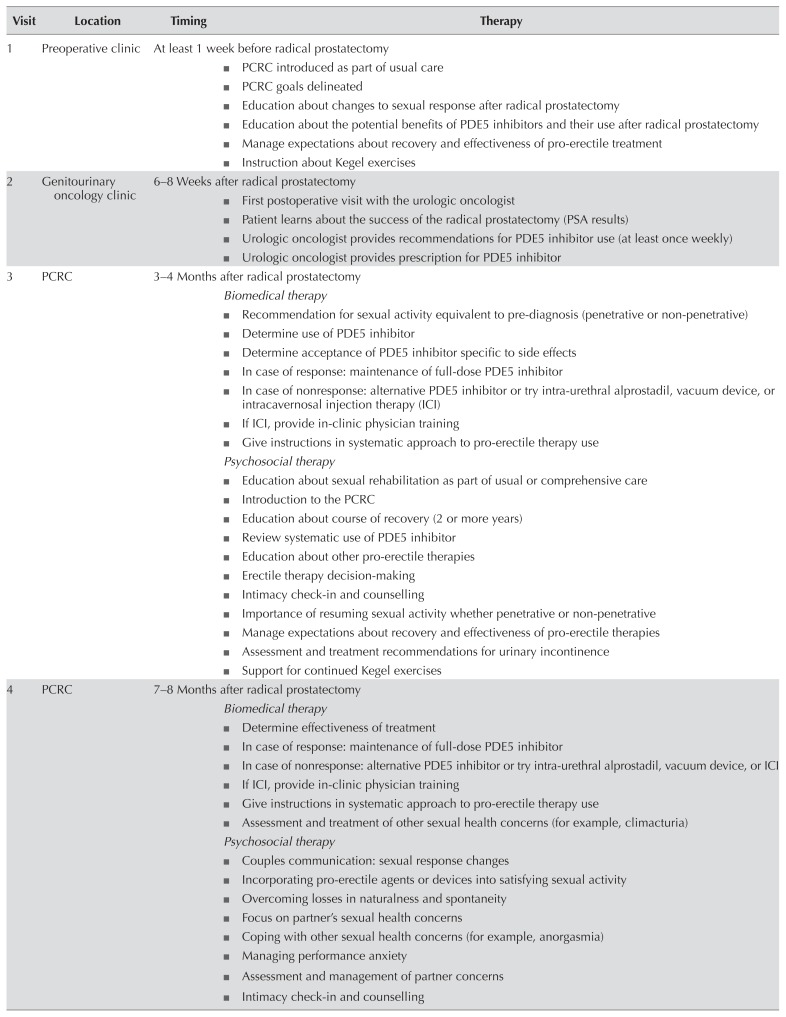

The pcrc program involves 7 clinic visits across 2 years, consisting of a pre-rp appointment, an appointment with the uro-oncologist at 6–8 weeks after the rp, and follow-up appointments with the multi-disciplinary team at 3–4, 7–8, 12–13, 17–18, and 22–24 months post-rp (for a detailed description of clinic visits, see Table II).

TABLE II.

Visits to the Prostate Cancer Rehabilitation Clinic (PCRC): clinical care content

| Visit | Location | Timing | Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preoperative clinic | At least 1 week before radical prostatectomy

|

|

| 2 | Genitourinary oncology clinic | 6–8 Weeks after radical prostatectomy

|

|

| 3 | PCRC | 3–4 Months after radical prostatectomy Biomedical therapy

|

|

| 4 | PCRC | 7–8 Months after radical prostatectomy Biomedical therapy

|

|

| 5 | PCRC | 12–13 Months after radical prostatectomy Biomedical therapy

|

|

| 6 | PCRC | 17–18 Months after radical prostatectomy Biomedical therapy

|

|

| 7 | PCRC | 22–24 Months after radical prostatectomy Biomedical therapy

|

|

PDE5 = phosphodiesterase type 5; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Institutional Support and Funding

The pcrc operates on private donor funding and research grants. The pcrc has not received institutional funding; however, support has been provided in the form of space allocation and human resources. Specifically, on a schedule of 3 days per month, the pcrc is provided with a clinic space consisting of 6 examination rooms. The urologist is compensated by ohip (the Ontario Health Insurance Plan), and the registered nurse and psychologist contributions are absorbed by their annual salaries. Additionally, the team developed a multidisciplinary training protocol for psychology and urology residents and fellows. The inclusion of trainees allowed pcrc to respond to increasing participant volume. In February 2013, the pcrc received a Quality of Life Research Grant from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute, which was applied toward examining the pcrc’s effectiveness (publication pending).

Research

Research is an important part of the pcrc. Data from each of the 7 clinic visits are collected and stored for longitudinal analysis (see Tables I and III for lists of pros and clinical data collected). Clinical records and psychosocial assessments for patients are stored in two relational databases. There are many research questions that we hope to explore from both a medical and a psychosocial perspective. We intend to examine the effect of the pcrc on patients in a variety of areas, including performance anxiety, maintenance of intimacy, adherence to treatment, satisfaction with sexual functioning, partner distress, couple communication, and the long-term use of pro-erectile agents. In addition, we have the capacity to examine physiologic and psychosocial responses to the use of pde5is and other types of ed therapy, and to compare the effectiveness of the various treatment modalities.

TABLE III.

Clinical data collected from the medical database

| Disease characteristics | Prostate-specific antigen and digital rectal exam |

| Biopsy and radical prostatectomy pathology | |

| Body mass index | |

| Transrectal ultrasonography | |

|

| |

| Treatments | Imaging |

| Computed tomography | |

| Ultrasonography | |

| Bone scan | |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | |

| Cystoscopy | |

|

| |

| Quality of life | Patient-Oriented Prostate Utility Scale48,a |

Collected serially during each oncology clinic visit.

Future Directions of the PCRC

To augment the care provided through the pcrc, we are developing the Kindness, Intimacy, Sexuality, and Satisfaction (kiss) manual. The kiss manual contains 13 chapters, all of which provide detailed information and diagrams specific to topics covered during the pcrc visits. Patients or couples are encouraged before each meeting to read the assigned chapters from the kiss manual. An important benefit of receiving the chapter assignments before the pcrc visit is that it provides patients with an opportunity to prepare questions that can be addressed during the clinic visit. Patients will also be able to review key points after the visit, which aligns with the recommendations of the American Medical Association that physicians should provide patients with educational handouts at the end of clinic visits49. Research has shown that providing patients with materials to take home after treatment can increase the likelihood of treatment adherence50 and might increase recollection of information given during the clinic visit51.

Our goal is to transition the pcrc from paper-based to electronic-based documentation and data collection to further enhance patient and partner care. To that end, the Treatment Fidelity Tracking Record has been transformed into an online document that is completed by the sexual health counsellors during each clinic visit, making documentation and review of the patient’s experience from prior clinic visits more efficient. Similarly, patients and partners complete their pros using an iPad in the pcrc waiting area before each visit; however, the pcrc infrastructure currently does not allow for real-time scoring of the pros and provision of feedback. By introducing immediate feedback, the patient and the sexual health counsellor would both be able to track pro responses in a number of domains (for example, erectile function, intimacy, distress). Patients could use the feedback to track their progress over the trajectory of the recovery period, and sexual health counsellors could monitor patient functioning and respond to identified concerns. Overall, the updated process will provide a further mechanism to encourage the “patient voice” to be included in their own care experience.

Knowledge Translation

The pcrc was designed with attention to the importance of knowledge translation. As a consequence, the protocol is highly structured. To ensure the reliability of treatment, a Treatment Fidelity Tracking Record is completed by the treating health care professional at each clinic visit. The Treatment Fidelity Tracking Record is specific to each clinic visit (for example, the 3- to 4-month post-rp visit) and includes check boxes associated with the ongoing assessment of sexual health concerns (anorgasmia, for instance), pro-erectile agent or device use (type, number of attempts, effectiveness), side effects, partner concerns, intimacy concerns, and clinic-specific psychosocial educational components (for example, performance anxiety). The kiss manual that complements those procedures supports sustainability and protects against treatment dilution, allowing for the pcrc to be packaged and distributed to other hospital-based treatment facilities.

DISCUSSION

It is widely recognized that psychosocial interventions for pca survivors are needed to facilitate the healing process and to assist patients with their effort to return to normal functioning52–54. Biomedical treatment for ed can improve sexual functioning in patients to some extent after rp6,45; however, sdf in patients treated for pca is complex and usually transcends a physiologic cause. The broader issue of intimacy between the patient and his partner is an important part of the survivorship experience that is rarely addressed during treatment55. The biomedical approach is itself not sufficient for treating ed in patients after rp—a more comprehensive treatment is needed. The biopsychosocial perspective of sdf after rp, as implemented in the pcrc, emphasizes a broad spectrum of medical, psychological, and interpersonal perspectives. The pcrc addresses factors that affect the couple’s experience of sdf after rp and also factors that influence early rejection of pro-erectile agents or devices so as to assist the couple in finding a satisfying solution to their sexual health concerns.

The pcrc has a number of important strengths. The program is delivered by a team that specializes in treating the effects of post-rp sdf on patients, partners, and couples. It is designed to accommodate the unique sdf effects on same-sex and heterosexual couples or individuals. One-on-one counselling is offered to patients and couples, supporting candid communication about intimate issues. Neese et al.15 found that, compared with a group format, a couples-based intervention with a health care professional is preferred by 74% and 93% of patients and their partners respectively. That format is also important given that couples can experience difficulty seeking social support for sdf. By facilitating communication for the couple, patients and their partners are enabled to become each other’s social support. The clinic uses automatic referral as a method for overcoming the stigma of seeking sdf treatment programming. The pcrc tries to increase treatment adherence by supporting couples for 2 years after the rp, in a series of 7 clinic visits at specified time points.

The challenge to biopsychosocial programs in general, and to the pcrc specifically, is the absence of scientific literature exploring the determining factors that influence coping and adaptation on the part of the patient and the partner. Studies conducted into new psychological therapies for treating sdf in pca patients after rp show promising results56, but more research into the benefit of involving the patient’s partner in the intervention is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

A great number of men are diagnosed each year with pca, and most will enjoy a long life after treatment. Thus, health care practitioners have a responsibility to ensure that pca survivors and their partners experience optimal hrqol during their survivorship years. We propose the pcrc: a multidisciplinary, couple-oriented, biopsychosocial program designed to help couples maintain intimacy and restore sexual functioning after rp. Integrated into the pcrc is research to address the requirement for greater understanding of the needs of patients and couples surviving pca and to help design cost-effective and beneficial rehabilitation programs.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society (acs) Cancer Facts and Figures 2012. Atlanta, GA: ACS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmons MN, Berglund RK, Jones JS. A practical guide to prostate cancer diagnosis and management. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011;78:321–31. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78a.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boorjian SA, Eastham JA, Graefen M, et al. A critical analysis of the long-term impact of radical prostatectomy on cancer control and function outcomes. Eur Urol. 2012;61:664–75. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnett AL, Aus G, Canby-Hagino ED, et al. on behalf of the American Urological Association Prostate Cancer Guideline Update Panel. Erectile function outcome reporting after clinically localized prostate cancer treatment. J Urol. 2007;178:597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alemozaffar M, Regan MM, Cooperberg MR, et al. Prediction of erectile function following treatment for prostate cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:1205–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glickman L, Godoy G, Lepor H. Changes in continence and erectile function between 2 and 4 years after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2009;181:731–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-Year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154637.38262.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heathcote PS, Mactaggart PN, Boston RJ, James AN, Thompson LC, Nicol DL. Health-related quality of life in Australian men remaining disease-free after radical prostatectomy. Med J Aust. 1998;168:483–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb141408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckley BS, Lapitan MCM, Glazener CM on behalf of the maps trial group. The effect of urinary incontinence on health utility and health-related quality of life in men following prostate surgery. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:465–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nandipati KC, Raina R, Agarwal A, Zippe CD. Erectile dysfunction following radical retropubic prostatectomy. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:101–17. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz A. Quality of life for men with prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:302–8. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000281726.87490.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, et al. Patients’ perception of quality of life after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3777–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harden J. Developmental life stage and couples’ experiences with prostate cancer: a review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28:85–98. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badr H, Taylor CL. Sexual dysfunction and spousal communication in couples coping with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:735–46. doi: 10.1002/pon.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neese LE, Schover LR, Klein EA, Zippe C, Kupelian PA. Finding help for sexual problems after prostate cancer treatment: a phone survey of men’s and women’s perspectives. Psychooncology. 2003;12:463–73. doi: 10.1002/pon.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung E, Brock G. Sexual rehabilitation and cancer survivorship: a state of art review of current literature and management strategies in male sexual dysfunction among prostate cancer survivors. J Sex Med. 2013;10(suppl 1):102–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salonia A, Burnett AL, Graefen M, et al. Prevention and management of postprostatectomy sexual dysfunctions part 2: recovery and preservation of erectile function, sexual desire, and orgasmic function. Eur Urol. 2012;62:273–86. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salonia A, Gallina A, Zanni G, et al. Acceptance of and discontinuation rate from erectile dysfunction oral treatment in patients following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008;53:564–70. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horsburgh S, Matthew A, Bristow R, Trachtenberg J. Male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a pilot study investigating medical characteristics of patients participating in a prostate cancer prevention clinic. Prostate. 2005;65:124–9. doi: 10.1002/pros.20278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarow JP, Nana-Sinkam P, Sabbagh M, Eskew A. Outcome analysis of goal directed therapy for impotence. J Urol. 1996;155:1609–12. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raina R, Pahlajani G, Agarwal A, Jones S, Zippe C. Long-term potency after early use of a vacuum erection device following radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2010;106:1719–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Titta M, Tavolini IM, Dal Moro F, Cisternino A, Bassi P. Sexual counseling improved erectile rehabilitation after non-nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy or cystectomy—results of a randomized prospective study. J Sex Med. 2006;3:267–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padma Nathan H, Christ G, Adaikan G, et al. Pharmacotherapy for erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1:128–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.04021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teloken P, Mesquita G, Montorsi F, Mulhall J. Original research— ed pharmacotherapy: post-radical prostatectomy pharmacological penile rehabilitation: practice patterns among the International Society for Sexual Medicine Practitioners. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2032–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davison BJ, Elliott S, Ekland M, Griffin S, Wiens K. Development and evaluation of a prostate sexual rehabilitation clinic: a pilot project. BJU Int. 2005;96:1360–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS, Eton DT, Schulz R. Improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial of group education interventions. Health Psychol. 2003;22:443–52. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molton IR, Siegel SD, Penedo FJ, et al. Promoting recovery of sexual functioning after radical prostatectomy with group-based stress management: the role of interpersonal sensitivity. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:527–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canada AL, Schover LR. Research promoting better patient education on reproductive health after cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005:98–100. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, et al. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African-American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners. Cancer. 2007;109(suppl):414–24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, et al. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:752–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, et al. A randomized trial of Internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012;118:500–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthew AG, Irvine J, Trachtenberg J, et al. Sexual dysfunction in couples after prostate cancer surgery: phase one— findings from initial interviews [abstract] Psychooncology. 2008;17:S17. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLeod D, Curran J, Dumont S, White M, Charles G. The Interprofessional Psychosocial Oncology Distance Education (ipode) project: perceived outcomes of an approach to healthcare professional education. J Interprof Care. 2014;28:254–9. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.863181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tran S, Walker LM, Wassersug RJ, Matthew AG, McLeod DL, Robinson JW. What do Canadian uro-oncologists believe patients should know about androgen deprivation therapy? J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2014;20:199–209. doi: 10.1177/1078155213495285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fergus KD, Gray RE, Fitch MI. Sexual dysfunction and the preservation of manhood: experiences of men with prostate cancer. J Health Psychol. 2002;7:303–16. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Pena AB. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (iief-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (fsfi): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Althof SE, Corty EW, Levine SB, et al. edits: development of questionnaires for evaluating satisfaction with treatments for erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1999;53:793–9. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Downs AC, Hillje ES. Reassessment of the Miller Social Intimacy Scale: use with mixed- and same-sex dyads produces multidimensional structures. Psychol Rep. 1991;69:991–7. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (epic) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56:899–905. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00858-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mulhall JP, Bivalacqua TJ, Becher EF. Standard operating procedure for the preservation of erectile function outcomes after radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med. 2013;10:195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulhall JP, Bella AJ, Briganti A, McCullough A, Brock G. Erectile function rehabilitation in the radical prostatectomy patient. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1687–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fode M, Ohl DA, Ralph D, Sønksen J. Penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy: what the evidence really says. BJU Int. 2013;112:998–1008. doi: 10.1111/bju.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Padma-Nathan H, McCullough AR, Levine LA, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of postoperative nightly sildenafil citrate for the prevention of erectile dysfunction after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:479–86. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2008.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montorsi F, Brock G, Lee J, Shindel AW, Lue TF. Words of wisdom. Re: Effect of nightly versus on-demand vardenafil on recovery of erectile function in men following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2009;56:1088–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krahn M, Ritvo P, Irvine J, et al. Construction of the Patient-Oriented Prostate Utility Scale (porpus): a multiattribute health state classification system for prostate cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:920–30. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiss BD. Health Literacy and Patient Safety: Help Patients Understand Manual for Clinicians. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: The American Medical Association Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandler DA, Mitchell JR, Fellows A, Garner ST. Is an information booklet for patients leaving hospital helpful and useful? BMJ. 1989;298:870–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6677.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Meulen N, Jansen J, van Dulmen S, Bensing J, van Weert J. Interventions to improve recall of medical information in cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2007;17:857–68. doi: 10.1002/pon.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 53.United States, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (nci) Living Beyond Cancer: Finding a New Balance. Washington, DC: NCI; 2004. [Available online at: http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/pcp03-04rpt/Survivorship.pdf; cited 28 June 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 54.United States, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc) A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing; 2014. [Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/survivors/pdf/plan.pdf ; cited 28 June 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Galbraith ME, Pedro LW, Jaffe AR, Allen TL. Describing health-related outcomes differences and similarities. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:794–801. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.794-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manne SL, Kissane DW, Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Winkel G, Zaider T. Intimacy-enhancing psychological intervention for men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their partners: a pilot study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:1197–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]