Abstract

Background

Adrenergic receptor stimulation is involved in the development of hypertension (htn) and has been implicated in cancer progression and dissemination of metastases in various tumours, including colon cancer. Adrenergic antagonists such as beta-blockers (bbs) demonstrate inhibition of invasion and migration in colon cancer cell lines and have been associated with decreased mortality in colorectal cancer (crc). We examined the association of baseline htn and bb use with overall (os) and progression-free survival (pfs) in patients with pretreated, chemotherapy refractory, metastatic crc (mcrc). We also examined baseline htn as a predictor of cetuximab efficacy.

Methods

Using data from the Canadian Cancer Trials Group co.17 study [cetuximab vs. best supportive care (bsc)], we coded baseline htn and use of anti-htn medications, including bbs, for 572 patients. The chi-square test was used to assess the associations between those variables and baseline characteristics. Cox regression models were used for univariate and multivariate analyses of os and pfs by htn diagnosis and bb use.

Results

Baseline htn, bb use, and anti-htn medication use were not found to be prognostic for improved os. Baseline htn and bb use were not significant predictors of cetuximab benefit.

Conclusions

In chemorefractory mcrc, neither baseline htn nor bb use is a significant prognostic factor. Baseline htn and bb use are not predictive of cetuximab benefit. Further investigation to determine whether baseline htn or bb use have a similarly insignificant impact on prognosis in patients receiving earlier lines of treatment remains warranted.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (crc) is the 3rd most commonly diagnosed malignancy in Canada and the 2nd leading cause of cancer death1. Despite treatment of localized disease with curative intent, nearly one third of patients experience disease relapse2, which often presents as incurable metastatic cancer. Although combination chemotherapy regimens and targeted agents have significantly improved survival for patients with metastatic disease, median overall survival (os) still does not usually exceed 36 months3,4. There is thus a pressing need to understand the factors that affect the development, progression, and ultimate dissemination of crc.

Sympathoadrenal activity plays a significant role in the development of hypertension (htn), as evidenced by the increased catecholamine levels found in hypertensive patients, and the prevention of blood pressure elevation caused by sympatholytic agents5. Stimulation of adrenergic receptors has also been postulated to play a role in cancer progression and in dissemination of metastases in various tumour types, including colon and breast cancer. Epinephrine, which acts as an agonist to many subtypes of alpha and beta adrenoreceptors, has been noted to stimulate colon cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent manner6 and to induce chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil7. In breast cancer, the expression of adrenoreceptor subtypes (for example, erbB2, epidermal growth factor receptor, progesterone receptor) varies according to tumour histology and molecular subtype and might be related to prognosis8. In colon cancer, beta3 adrenoreceptor expression is demonstrably increased in tumours compared with the normal colonic mucosa9. In pancreatic cancer cell lines, beta-adrenergic receptor activation leads to the phosphorylation of p38/mapk (mitogen-activated protein kinase), which is associated with increased proliferation and cell migration10. Gene signature evidence also suggests commonalities between the pathways involved with breast cancer (for example, matrix metalloproteinases, chemokines, interleukins) and the beta-adrenergic pathways11.

Further significance of the adrenergic pathway on tumour progression is evidenced by the inhibitory action of adrenergic blockers. Adrenergic antagonists such as beta-blocking drugs demonstrate inhibition of invasion and migration in colon cancer cell lines12 and growth inhibition in other cancer cell lines13. Exposure to beta-blockers (bbs) and angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin ii receptor blockers, which are commonly used antihypertensives, is associated with decreased mortality in advanced colorectal cancer14. Similarly, after adjusting for other variables, bb use has been associated with improved relapse-free survival in breast cancer patients15.

The prevalence of htn in Canada was 20% in 200816, and it increased to 22.6% in 2013, with an associated increase in use of antihypertensive drugs17. Although the prevalence and awareness of htn in the elderly population have increased over time, the proportion of that population treated to achieve optimal blood pressure control remains lower than it does in younger patients16,18,19. Given that the median age of diagnosis for crc approximates 70 years, many crc patients have htn. Patients with crc are now also routinely exposed to inhibitors of the vascular endothelial growth factor (vegf) pathway (bevacizumab, regorafenib) or steroids, which can exacerbate or precipitate htn. Whether the development of htn during chemotherapy or non-vegf-inhibitor therapy affects cancer outcomes such as disease progression or mortality is unknown. Ultimately, the effect of baseline htn and bb use on cancer outcomes in the setting of advanced crc remains unknown.

OBJECTIVES

Using data from the Canadian Cancer Trials Group and Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group co.17 trial, our main objective was to examine the prognostic value of baseline htn (bhtn) and bb use with respect to survival in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic crc (mcrc). Furthermore, we examined the value of bhtn as a predictor of cetuximab efficacy in patients with mcrc. Specifically, we examined the effect of bhtn on os and the effect of bb use on os. Other examined effects included os in the context of the use of non-bb antihypertensive medication (alpha-blockers, angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics, calcium channel blockers), the effect of bhtn or of the use of bbs or antihypertensives on progression-free survival (pfs), and the predictive value of bhtn for the effect of cetuximab treatment (os, pfs) in patients with mcrc.

METHODS

Data Extraction

Previously captured data from co.17 were used for the analysis. In that study, 572 patients with chemotherapy-refractory mcrc were randomly assigned to cetuximab (400 mg/m2 loading dose, followed by 250 mg/m2 weekly) and best supportive care (bsc) or to bsc alone. Results from co.17 demonstrated improved os, pfs, objective tumour response rate, and better preservation of health-related quality of life with cetuximab treatment20,21. The data extracted included bhtn and baseline use of antihypertensive medications, with the specific type of medication recorded:

▪ Beta-blockers: metoprolol, labetalol, atenolol, bisoprolol, nadalol, propranolol, carvedilol, acebutolol

▪ Alpha-blockers: clonidine, doxazosin, methyldopa, terazosin, prazosin

▪ Angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors: captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril quinapril, ramipril, trandolapril, benazepril, cilazapril

▪ Angiotensin receptor blockers: candesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, telmisartan, valsartan

▪ Diuretics: hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, indapamide, metolazone, amiloride, triamterene

▪ Calcium-channel blockers: amlodipine, diltiazem, nicardipine, nifedipine, verapamil

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test was used for univariate analyses of associations between the two patient groups (with and without bhtn) and their baseline characteristics. A logistic regression model was used for multivariate analyses to identify any independent characteristics associated with htn status. Cox regression models were used for univariate and multivariate analyses of os and pfs by htn diagnosis, bb use, and antihypertensive use. Multivariate models included only covariates that were significant at the 0.1 level in univariate analysis.

The predictive effect of bhtn for cetuximab treatment outcomes (os, pfs) was analyzed by using a Cox model to test the interaction of bhtn and treatment. Analysis of the predictive effect of bhtn for cetuximab treatment outcomes by KRAS status (wild-type vs. mutated) was also undertaken.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table I presents key baseline patient, disease, and treatment characteristics by bhtn status. In the univariate analysis, patients of older age, higher body mass index, or higher serum creatinine or receiving bsc were more likely to have bhtn. Age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, body mass index, and serum creatine level were identified as independent factors associated with htn status in the multivariate analysis.

TABLE I.

Baseline patient, disease, and treatment characteristics for patients with and without baseline hypertension

| Characteristic | Hypertension at baseline | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Yes | No | Univariatea | Multivariateb | |

| Patients (n) | 149 | 423 | ||

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | 0.0006 | ||

| Median | 66.9 | 61.5 | ||

| Range | 42.9–88.1 | 28.6–85.9 | ||

|

| ||||

| Age group [n (%)] | ||||

| <65 Years | 65 (43.6) | 270 (63.8) | ||

| ≥65 Years | 84 (56.4) | 153 (36.2) | ||

|

| ||||

| Sex [n (%)] | 0.112 | 0.421 | ||

| Women | 45 (30.2) | 159 (37.6) | ||

| Men | 104 (69.8) | 264 (62.4) | ||

|

| ||||

| ECOG PS [n (%)] | 0.062 | 0.047 | ||

| 0 | 28 (18.8) | 108 (25.5) | ||

| 1 | 91 (61.1) | 211 (49.9) | ||

| 2 | 30 (20.1) | 104 (24.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | <0.001 | 0.018 | ||

| Median | 27.1 | 25.3 | ||

| Range | 16.4–42.5 | 15.6–45.0 | ||

|

| ||||

| BMI group [n (%)] | ||||

| Low (<20) | 6 (4.0) | 52 (12.3) | ||

| Normal (20–25) | 44 (29.5) | 142 (33.6) | ||

| High (>25) | 99 (66.4) | 229 (54.1) | ||

|

| ||||

| Site of primary [n (%)] | 0.561 | 0.576 | ||

| Colon only | 87 (58.4) | 245 (57.9) | ||

| Rectum only | 38 (25.5) | 95 (22.5) | ||

| Colon and rectum | 24 (16.1) | 83 (19.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Initial Dx to randomization (years) | 0.071 | 0.702 | ||

| Median | 2.4 | 2.2 | ||

| Range | 0.5–10.4 | 0–15.7 | ||

|

| ||||

| Dx-to-randomization group [n (%)] | ||||

| ≥2 Years | 93 (62.4) | 234 (55.3) | ||

| <2years | 56 (37.6) | 189 (44.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| Serum creatinine [n (%)] | 0.014 | 0.010 | ||

| Grade 0c | 127 (85.2) | 390 (92.2) | ||

| ≥Grade 1c | 22 (14.8) | 32 ( 7.6) | ||

|

| ||||

| Previous CTx drug classes [n (%)] | 0.508 | 0.740 | ||

| ≤2 | 9 ( 6.0) | 19 ( 4.5) | ||

| >2 | 140 (94.0) | 404 (95.5) | ||

|

| ||||

| KRAS status [n (%)] | 0.201 | 0.215 | ||

| Wild type | 66 (44.3) | 164 (38.8) | ||

| Mutated | 37 (24.8) | 127 (30.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Treatment [n (%)] | 0.017 | 0.050 | ||

| BSC only | 87 (58.4) | 198 (46.8) | ||

| Cetuximab and BSC | 62 (41.6) | 225 (53.2) | ||

Wilcoxon test for continuous variables; Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Logistic regression model.

According to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; BMI = body mass index; Dx = diagnosis; CTx = chemotherapy; BSC = best supportive care.

Based on the univariate analysis of key baseline patient, disease, and treatment characteristics by bb use at baseline, patients of older age, male sex, and higher body mass index were noted to be more likely to use a bb at baseline. Age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, and serum creatinine level were identified as independent factors associated with use of a bb in the multivariate analysis.

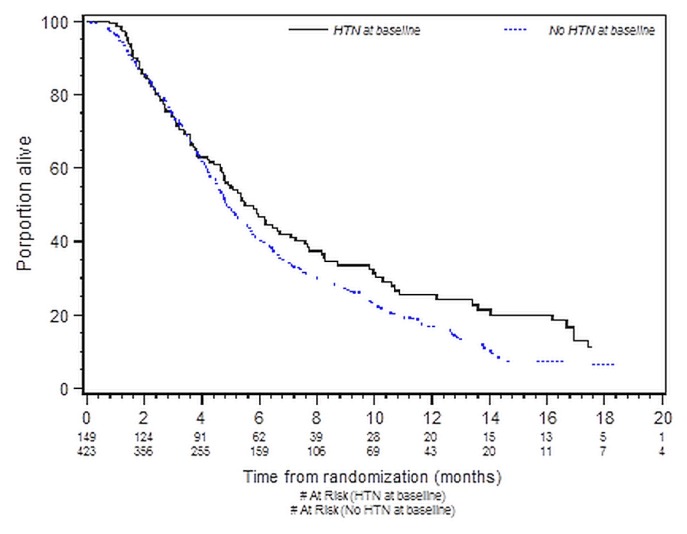

Prognostic Effects

Table II presents the results of the os analysis by bhtn status for all patients. No significant association was found between bhtn and improved os in either the univariate analysis [hazard ratio (patients without htn compared with patients with htn): 1.22; 95% confidence limits: 0.98, 1.51; p = 0.07] or the multivariate analysis (hazard ratio: 1.05; 95% confidence limits: 0.80, 1.38; p = 0.72). Figure 1 depicts os by bhtn group. No significant association was found between baseline use of a bb and improved os in either the univariate or the multivariate analysis.

TABLE II.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall survival in patients with and without baseline hypertension (HTN)

| Characteristic | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| HR | 95% CL | p Valuea | Adjusted HR | 95% CL | p Valueb | |

| Current or past diagnosis of HTN | 0.071 | 0.720 | ||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No | 1.22 | 0.98, 1.51 | 1.05 | 0.80, 1.38 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age group | 0.596 | Not in model | ||||

| <65 Years | Reference | |||||

| ≥65 Years | 1.05 | 0.87, 1.27 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Sex | 0.107 | Not in model | ||||

| Women | Reference | |||||

| Men | 0.85 | 0.70, 1.04 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ECOG PS | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 1 | 1.15 | 0.92, 1.45 | 1.25 | 0.94, 1.67 | 0.127 | |

| 2 | 2.51 | 1.93, 3.27 | 1.96 | 1.37, 2.80 | <0.0001 | |

|

| ||||||

| BMI group (kg/m2) | <0.0001 | |||||

| Low (<20) | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Normal (20–25) | 0.77 | 0.56, 1.05 | 0.86 | 0.54, 1.35 | 0.501 | |

| High (>25) | 0.54 | 0.40, 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.45, 1.10 | 0.123 | |

|

| ||||||

| Site of primary | 0.068 | |||||

| Colon only | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Rectum only | 0.83 | 0.66, 1.05 | 0.85 | 0.62, 1.17 | 0.323 | |

| Colon and rectum | 0.82 | 0.64, 1.05 | 0.77 | 0.55, 1.06 | 0.113 | |

|

| ||||||

| Dx-to-randomization group | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| >2 Years | Reference | Reference | ||||

| <2 Years | 1.57 | 1.31, 1.90 | 1.66 | 1.30, 2.12 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Lactate dehydrogenase | <0.0001 | 0.026 | ||||

| ≤Upper limit of normal | Reference | Reference | ||||

| >Upper limit of normal | 1.99 | 1.56,2.53 | 1.42 | 1.04, 1.93 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| ≤Upper limit of norma | Reference | Reference | ||||

| >Upper limit of normal | 2.16 | 1.73, 2.70 | 1.81 | 1.34, 2.44 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hemoglobin | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Grade 0c | Reference | Reference | ||||

| ≥Grade 1c | 2.02 | 1.64, 2.48 | 1.79 | 1.38, 2.33 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Serum creatinine | 0.839 | Not in model | ||||

| Grade 0c | Reference | |||||

| ≥Grade 1c | 1.03 | 0.75, 1.42 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Previous CTx drug classes | 0.192 | Not in model | ||||

| ≤2 | Reference | |||||

| >2 | 1.35 | 0.86, 2.11 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| KRAS status | 0.007 | 0.001 | ||||

| Wild type | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Mutated | 1.36 | 1.09, 1.70 | 1.51 | 1.18, 1.93 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Treatment | 0.004 | 0.045 | ||||

| BSC only | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Cetuximab and BSC | 0.76 | 0.63, 0.92 | 0.78 | 0.62, 0.99 | ||

Log-rank test.

Cox model using all factors reaching p ≤ 0.1 in the univariate analysis.

According to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

HR = hazard ratio; CL = confidence limits; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; BMI = body mass index; Dx = diagnosis; CTx = chemotherapy; BSC = best supportive care.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival in patients with and without baseline hypertension (HTN). Log-rank p = 0.07.

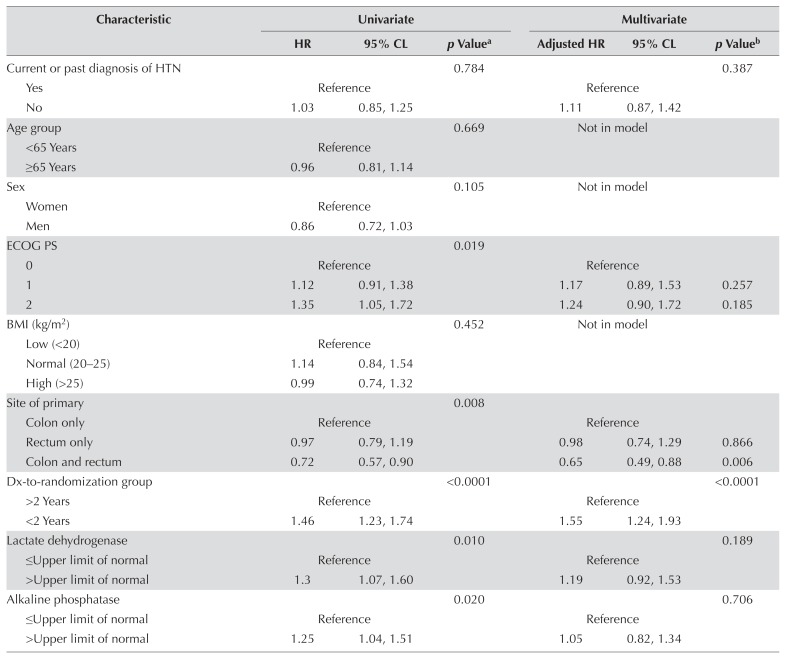

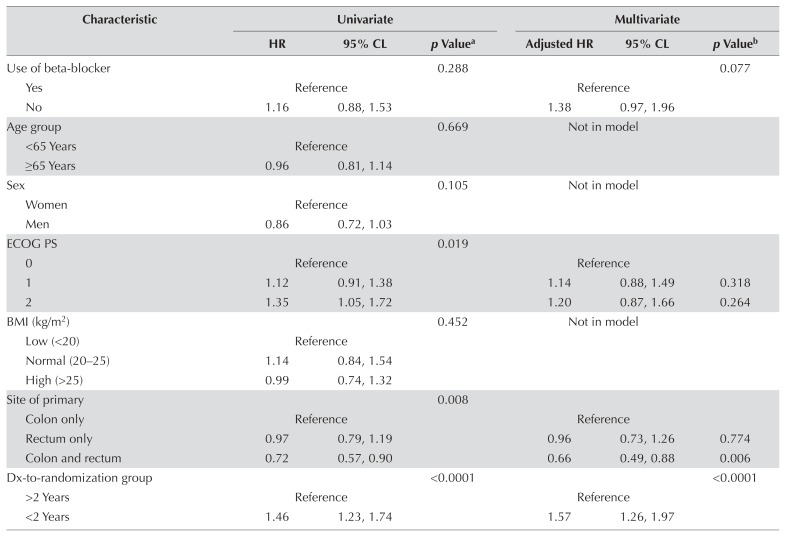

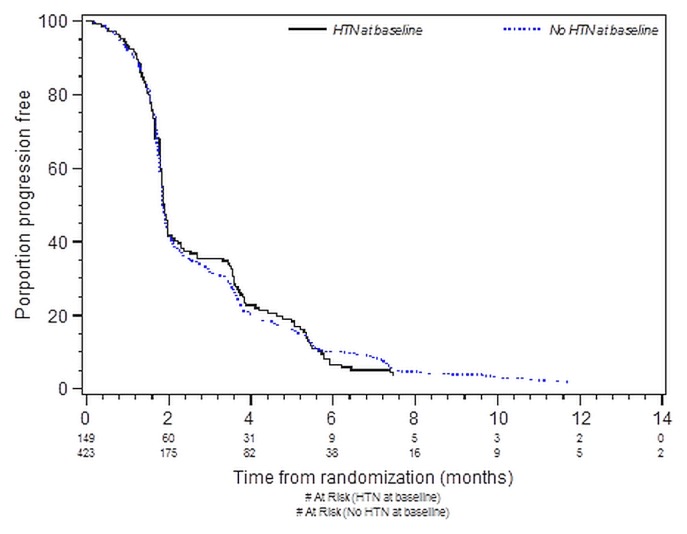

Tables III and IV present the results of analyses for pfs by bhtn status and by use of bbs for all patients. Figure 2 depicts pfs by bhtn group. No significant association was found between bhtn and improved pfs in either the univariate or the multivariate analysis. No significant association was observed between bb use and improved pfs [adjusted hazard ratio (patients not using bbs compared with patients using bbs): 1.38; 95% confidence limits: 0.97, 1.96; p = 0.08].

TABLE III.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for progression-free survival in patients with and without baseline hypertension (HTN)

| Characteristic | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| HR | 95% CL | p Valuea | Adjusted HR | 95% CL | p Valueb | |

| Current or past diagnosis of HTN | 0.784 | 0.387 | ||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No | 1.03 | 0.85, 1.25 | 1.11 | 0.87, 1.42 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age group | 0.669 | Not in model | ||||

| <65 Years | Reference | |||||

| ≥65 Years | 0.96 | 0.81, 1.14 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Sex | 0.105 | Not in model | ||||

| Women | Reference | |||||

| Men | 0.86 | 0.72, 1.03 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ECOG PS | 0.019 | |||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 1 | 1.12 | 0.91, 1.38 | 1.17 | 0.89, 1.53 | 0.257 | |

| 2 | 1.35 | 1.05, 1.72 | 1.24 | 0.90, 1.72 | 0.185 | |

|

| ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.452 | Not in model | ||||

| Low (<20) | Reference | |||||

| Normal (20–25) | 1.14 | 0.84, 1.54 | ||||

| High (>25) | 0.99 | 0.74, 1.32 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Site of primary | 0.008 | |||||

| Colon only | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Rectum only | 0.97 | 0.79, 1.19 | 0.98 | 0.74, 1.29 | 0.866 | |

| Colon and rectum | 0.72 | 0.57, 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.49, 0.88 | 0.006 | |

|

| ||||||

| Dx-to-randomization group | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| >2 Years | Reference | Reference | ||||

| <2 Years | 1.46 | 1.23, 1.74 | 1.55 | 1.24, 1.93 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 0.010 | 0.189 | ||||

| ≤Upper limit of normal | Reference | Reference | ||||

| >Upper limit of normal | 1.3 | 1.07, 1.60 | 1.19 | 0.92, 1.53 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase | 0.020 | 0.706 | ||||

| ≤Upper limit of normal | Reference | Reference | ||||

| >Upper limit of normal | 1.25 | 1.04, 1.51 | 1.05 | 0.82, 1.34 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hemoglobin | 0.094 | 0.573 | ||||

| Grade 0c | Reference | Reference | ||||

| ≥Grade 1c | 1.17 | 0.97, 1.40 | 1.07 | 0.85, 1.35 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Serum creatinine | 0.879 | Not in model | ||||

| Grade 0c | Reference | |||||

| ≥Grade 1c | 0.98 | 0.74, 1.30 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Previous CTx drug classes | 0.725 | Not in model | ||||

| ≤2 | Reference | |||||

| >2 | 1.07 | 0.73, 1.58 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| KRAS status | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Wildtype | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Mutated | 1.67 | 1.36, 2.05 | 1.58 | 1.27, 1.97 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Treatment | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| BSC only | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Cetuximab and BSC | 0.68 | 0.57, 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.53, 0.82 | ||

Log-rank test.

Cox model using all factors reaching p≤0.1 in the univariate analysis.

According to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

HR = hazard ratio; CL = confidence limits; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; BMI = body mass index; Dx = diagnosis; CTx = chemotherapy; BSC = best supportive care.

TABLE IV.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for progression-free survival by beta-blocker status, all patients

| Characteristic | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| HR | 95% CL | p Valuea | Adjusted HR | 95% CL | p Valueb | |

| Use of beta-blocker | 0.288 | 0.077 | ||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||||

| No | 1.16 | 0.88, 1.53 | 1.38 | 0.97, 1.96 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age group | 0.669 | Not in model | ||||

| <65 Years | Reference | |||||

| ≥65 Years | 0.96 | 0.81, 1.14 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Sex | 0.105 | Not in model | ||||

| Women | Reference | |||||

| Men | 0.86 | 0.72, 1.03 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ECOG PS | 0.019 | |||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 1 | 1.12 | 0.91, 1.38 | 1.14 | 0.88, 1.49 | 0.318 | |

| 2 | 1.35 | 1.05, 1.72 | 1.20 | 0.87, 1.66 | 0.264 | |

|

| ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.452 | Not in model | ||||

| Low (<20) | Reference | |||||

| Normal (20–25) | 1.14 | 0.84, 1.54 | ||||

| High (>25) | 0.99 | 0.74, 1.32 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Site of primary | 0.008 | |||||

| Colon only | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Rectum only | 0.97 | 0.79, 1.19 | 0.96 | 0.73, 1.26 | 0.774 | |

| Colon and rectum | 0.72 | 0.57, 0.90 | 0.66 | 0.49, 0.88 | 0.006 | |

|

| ||||||

| Dx-to-randomization group | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| >2 Years | Reference | Reference | ||||

| <2 Years | 1.46 | 1.23, 1.74 | 1.57 | 1.26, 1.97 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 0.010 | 0.140 | ||||

| ≤Upper limit of normal | Reference | Reference | ||||

| >Upper limit of normal | 1.30 | 1.07, 1.60 | 1.21 | 0.94, 1.57 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Alkaline phosphatase | 0.020 | 0.911 | ||||

| ≤Upper limit of normal | Reference | Reference | ||||

| >Upper limit of normal | 1.25 | 1.04, 1.51 | 1.01 | 0.79, 1.30 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hemoglobin | 0.094 | 0.628 | ||||

| Grade 0c | Reference | Reference | ||||

| ≥Grade 1c | 1.17 | 0.97, 1.40 | 1.06 | 0.84, 1.34 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Serum creatinine | 0.879 | Not in model | ||||

| Grade 0c | Reference | |||||

| ≥Grade 1c | 0.98 | 0.74, 1.30 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Previous CTx drug classes | 0.725 | Not in model | ||||

| ≤2 | Reference | |||||

| >2 | 1.07 | 0.73, 1.58 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| KRAS status | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Wild type | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Mutated | 1.67 | 1.36, 2.05 | 1.63 | 1.31, 2.03 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Treatment | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| BSC only | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Cetuximab and BSC | 0.68 | 0.57, 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.53, 0.81 | ||

Log-rank test.

Cox model using all factors reaching p≤0.1 in the univariate analysis.

According to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

HR = hazard ratio; CL = confidence limits; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; BMI = body mass index; Dx = diagnosis; CTx = chemotherapy; BSC = best supportive care.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for progression-free survival in patients with and without baseline hypertension (HTN). Log-rank p = 0.78.

With respect to the effect of antihypertensive medication use at baseline on os and pfs, no significant association was found in either the univariate or the multivariate analysis.

Predictive Effects

Tables V and VI present the results of the subgroup analysis of os and pfs, comparing cetuximab with bsc in each of the subgroups defined by bhtn. The treatment effect was not different in the groups defined by bhtn status.

TABLE V.

Predictive effects of baseline hypertension for overall survival

| Factor | Survival with best supportive care | HRa (95% CL) | p Valueb | Interaction (95% CL) | p Valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| And cetuximab | And no cetuximab | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Pts (n) | Median months (95% CL) | Pts (n) | Median months (95% CL) | |||||

| All patients | ||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Yes | 62 | 7.3 (5.4, 10.7) | 87 | 4.8 (3.7, 5.9) | 0.67 (0.45, 0.98) | 0.038 | 1.20 (0.77, 1.86) | 0.418 |

| No | 225 | 5.7 (4.9, 6.5) | 198 | 4.5 (4.0, 4.8) | 0.77 (0.62, 0.95) | 0.015 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Patients with wild-type KRAS | ||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Yes | 25 | 10.6 (7.3, 16.9) | 41 | 5.1 (3.6, 6.2) | 0.37 (0.20, 0.72) | 0.002 | 1.54 (0.75, 3.17) | 0.238 |

| No | 92 | 8.4 (7.0, 9.9) | 72 | 4.6 (4.0, 5.5) | 0.59 (0.41, 0.83) | 0.003 | ||

For cetuximab and best supportive care compared with best supportive care only.

Log-rank test for cetuximab and best supportive care compared with best supportive care only.

From Cox proportional hazards model with factor, treatment, and their interaction as covariates.

Pts = patients; CL = confidence limits; HR = hazard ratio.

TABLE VI.

Predictive effects of baseline hypertension for progression-free survival

| Factor | Survival with best supportive care | HRa (95% CL) | p Valueb | Interaction (95% CL) | p Valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| And cetuximab | And no cetuximab | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Pts (n) | Median months (95% CL) | Pts (n) | Median months (95% CL) | |||||

| All patients | ||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Yes | 62 | 3.5 (1.9, 3.9) | 87 | 1.8 (1.8, 1.9) | 0.49 (0.34, 0.69) | <0.0001 | 1.43 (0.97, 2.11) | 0.074 |

| No | 225 | 1.8 (1.8, 1.9) | 198 | 1.9 (1.8, 2.0) | 0.75 (0.62, 0.92) | 0.005 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Patients with wild-type KRAS | ||||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Yes | 25 | 5.1 (3.5, 5.7) | 41 | 2.0 (1.8, 2.5) | 0.44 (0.26, 0.75) | 0.002 | 0.71 (0.38, 1.32) | 0.284 |

| No | 92 | 3.6 (2.0, 5.1) | 72 | 1.8 (1.7, 1.9) | 0.35 (0.25, 0.51) | <0.0001 | ||

For cetuximab and best supportive care compared with best supportive care only.

Log-rank test for cetuximab and best supportive care compared with best supportive care only.

From Cox proportional hazards model with factor, treatment, and their interaction as covariates.

Pts = patients; CL = confidence limits; HR = hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

Hypertension has been shown to be a significant risk factor in developing cancer. A large prospective observational study in 2011 observed that patients with elevated blood pressure experienced an increased incidence of cancers, including the colorectal type22. The association between htn and increased cancer incidence23 and mortality24,25 has also been described in multiple studies, although the causal correlation remains difficult to ascertain because of the possibility of competing risk factors—including lifestyle choices—that might not be taken directly into account. Whether baseline htn is a secondary risk factor for disease recurrence or progression remains unclear.

Our analysis explores the effect that baseline htn might have on prognosis in colon cancer patients. Our review suggests that neither bhtn nor the use of antihypertensive medications (including bbs) is significantly related to os or pfs. Being that htn is a multifactorial comorbidity, a question arises about whether controlling for certain associated factors might have brought to light a more significant relationship between bhtn and prognosis. Furthermore, given that our cohort included only patients with advanced-stage crc refractory to standard chemotherapy, the study results might not be generalizable to patients newly diagnosed with mcrc. There is evidence that increased exposure to chemotherapy is associated with an increased risk of developing htn26 and that vegf inhibitors can lead to the development of htn that can persist after cessation of therapy27. It is therefore possible that the inherent mechanism of bhtn plays a differential role in respect to its effect on prognosis in cancer.

Available evidence both promotes and refutes the prognostic value of the use of antihypertensive medications on cancer outcomes28–32. In particular, beta-adrenergic blockade is thought to reduce cancer progression by reducing promotion of metastasis. Many studies have demonstrated that chronic activation of the stress response, oftentimes associated with catecholamine release, can lead to progression of metastases in in vivo mouse models33–36. Furthermore, the release of catecholamines that target beta-adrenergic receptor signalling pathways (such as norepinephrine) is believed to be a possible pathway to increased dissemination of metastases37–39. Building on that knowledge, beta-adrenergic receptor blockers have been investigated both in vitro and in vivo for their potential to slow metastasis, with encouraging results in various tumour types40–42. However, our study did not reveal any significant link between survival and the baseline use of bbs. That lack of an association might be attributable to the small number of patients in our cohort who were using bbs at baseline or to an influence on survival of the comorbidity for which the patients were using the drug (ischemic heart disease or arrhythmia, for instance). Ultimately, the use of bbs in patients with earlier-stage disease warrants further investigation.

In our investigation, bhtn did not significantly predict benefit from cetuximab. However, a stronger cetuximab treatment effect was noted in patients with bhtn. Cetuximab is a monoclonal antibody targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor43, which, among other effects, lowers the production of vegf. It is possible that the stronger cetuximab treatment effect observed in patients with bhtn might be a result of increased levels of circulating vegf, which might itself be influenced by other comorbidities such as inflammatory conditions or renal insufficiency.

KRAS mutation status is a known predictive factor for cetuximab treatment effect, in that patients with crc having KRAS mutations in exon 2 (codons 12 and 13) achieve no appreciable benefit from cetuximab treatment in the chemotherapy-refractory metastatic setting44. Our analysis suggests that neither bhtn nor the use of bbs has a significant predictive effect for cetuximab treatment outcomes in the KRAS wild-type population.

Limitations of our study include its inherent retrospective nature. Given the small number of patients using bbs, no distinction was made between the beta1 and beta2 bbs, which could have had some bearing on effect. In addition, given that blood pressure is a multifactorial and continuous variable, the threshold value for investigating an effect remains arbitrary. Although guidelines specify a particular blood pressure value as representing htn in the normal population, the blood pressure at which an end-stage cancer patient is deemed to be hypertensive might differ. Another limitation is the confounding factors associated with htn and use of bbs that remain unaccounted for, such as concomitant comorbidities.

CONCLUSIONS

Ultimately, our study was unable to demonstrate a clear prognostic or predictive value for either bhtn or use of bbs. Nevertheless, the effect of bb use in particular merits further investigation in earlier-stage disease.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare the following interests: TP has acted in a consulting or advisory role for Amgen, Merck Serono, and Roche; NT has acted in a consulting or advisory role for, or has received research funding from, Amgen and Roche; NP has received honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Serono, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche; PG has received honoraria from Amgen, Merck, Roche, Servier, and Sirtex Medical and has received (institutional) research funding from Amgen, Merck Serono, and Roche; LS has acted in a consulting or advisory role for Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, Novartis (institutional), and Oncoethix and has received research funding from Abraxis BioScience, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol–Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Karyopharm Therapeutics, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Regeneron; SG has received honoraria from Celgene and Eli Lilly, has acted in a consulting or advisory role for Celgene, Eli Lilly, Shire, and Taiho Pharmaceutical, and has received research funding from Celgene; the remaining authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2014. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andre T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage ii or iii colon cancer in the mosaic trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3109–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venook A, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz HJ, et al. calgb/swog 80405: Phase iii trial of irinotecan/5-fu/leucovorin (folfiri) or oxaliplatin/5-fu/leucovorin (mfolfox6) with bevacizumab (bv) or cetuximab (cet) for patients (pts) with KRAS wild-type (wt) untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum (mcrc) [abstract LBA3] J Clin Oncol. 2014;32 doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.32.18_suppl.lba3. [Available online at: http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/jco.2014.32.18_suppl.lba3; cited 15 February 2015] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, et al. folfiri plus cetuximab versus folfiri plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (fire-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1065–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michel MC, Brodde OE, Insel PA. Peripheral adrenergic receptors in hypertension. Hypertension. 1990;16:107–20. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong HP, Ho JW, Koo MW, et al. Effects of adrenaline in human colon adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells. Life Sci. 2011;88:1108–12. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao H, Duan Z, Wang M, Awonuga AO, Rappolee D, Xie Y. Adrenaline induces chemoresistance in HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;190:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powe DG, Voss MJ, Habashy HO, et al. Alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor (ar) protein expression is associated with poor clinical outcome in breast cancer: an immunohistochemical study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:457–63. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1371-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perrone MG, Notarnicola M, Caruso MG, Tutino V, Scilimati A. Upregulation of beta3-adrenergic receptor mrna in human colon cancer: a preliminary study. Oncology. 2008;75:224–9. doi: 10.1159/000163851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang XY, Wang HC, Yuan Z, Huang J, Zheng Q. Norepinephrine stimulates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion via β-adrenergic receptor-dependent activation of P38/mapk pathway. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:889–93. doi: 10.5754/hge11476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kafetzopoulou LE, Boocock DJ, Dhondalay GK, Powe DG, Ball GR. Biomarker identification in breast cancer: beta-adrenergic receptor signaling and pathways to therapeutic response. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2013;6:e201303003. doi: 10.5936/csbj.201303003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iseri OD, Sahin FI, Terzi YK, Yurtcu E, Erdem SR, Sarialioglu F. β-Adrenoreceptor antagonists reduce cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and migration. Pharm Biol. 2014;52:1374–81. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.892513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozanoglu I, Yandim MK, Cincin ZB, Ozdogu H, Cakmakoglu B, Baran Y. New indication for therapeutic potential of an old well-known drug (propranolol) for multiple myeloma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:327–35. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1331-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engineer DR, Burney BO, Hayes TG, Garcia JM. Exposure to acei/arb and beta-blockers is associated with improved survival and decreased tumor progression and hospitalizations in patients with advanced colon cancer. Transl Oncol. 2013;6:539–45. doi: 10.1593/tlo.13346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melhem-Bertrandt A, Chavez-Macgregor M, Lei X, et al. Beta-blocker use is associated with improved relapse-free survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2645–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robitaille C, Dai S, Waters C, et al. Diagnosed hypertension in Canada: incidence, prevalence and associated mortality. CMAJ. 2012;184:E49–56. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padwal RS, Bienek A, McAlister FA, Campbell NR on behalf of the Outcomes Research Task Force of the Canadian Hypertension Education Program. Epidemiology of hypertension in Canada: an update. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:687–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.07.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostchega Y, Dillon CF, Hughes JP, Carroll M, Yoon S. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in older U.S. adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988 to 2004. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1056–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonker DJ, O’Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS, et al. Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2040–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Au HJ, Karapetis CS, O’Callaghan CJ, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab: overall and KRAS-specific results of the ncic ctg and agitg co.17 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1822–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stocks T, Van Hemelrijck M, Manjer J, et al. Blood pressure and risk of cancer incidence and mortality in the Metabolic Syndrome and Cancer Project. Hypertension. 2012;59:802–10. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.189258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buck C, Donner A. Cancer incidence in hypertensives. Cancer. 1987;59:1386–90. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870401)59:7<1386::AID-CNCR2820590726>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khaw KT, Barrett-Connor E. Systolic blood pressure and cancer mortality in an elderly population. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;120:550–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dyer AR, Stamler J, Berkson DM, Lindberg HA, Stevens E. High blood pressure: a risk factor for cancer mortality? Lancet. 1975;1:1051–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)91826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraeman KH, Nordstrom BL, Luo W, Landis SH, Shantakumar S. Incidence of new-onset hypertension in cancer patients: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Hypertens. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/379252. 379252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayman SR, Leung N, Grande JP, Garovic VD. vegf inhibition, hypertension, and renal toxicity. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:285–94. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0242-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devore EE, Kim S, Ramin CA, et al. Antihypertensive medication use and incident breast cancer in women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:219–29. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li CI, Malone KE, Weiss NS, Boudreau DM, Cushing-Haugen KL, Daling JR. Relation between use of antihypertensive medications and risk of breast carcinoma among women ages 65–79 years. Cancer. 2003;98:1504–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gómez-Acebo I, Dierssen-Sotos T, Palazuelos C, et al. The use of antihypertensive medication and the risk of breast cancer in a case–control study in a Spanish population: the mcc–Spain study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bangalore S, Kumar S, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of cancer: network meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of 324 168 participants from randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:65–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li CI, Daling JR, Tang MTC, Haugen KL, Porter P, Malone KE. Use of antihypertensive medications and breast cancer risk among women aged 55 to 74 years. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1629–37. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao L, Xu J, Liang F, Li A, Zhang Y, Sun J. Effect of chronic psychological stress on liver metastasis of colon cancer in mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang A, Le CP, Walker AK, et al. β2-Adrenoceptors on tumor cells play a critical role in stress-enhanced metastasis in a mouse model of breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;57:106–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang A, Kim-Fuchs C, Le CP, Hollande F, Sloan EK. Neural regulation of pancreatic cancer: a novel target for intervention. Cancers (Basel) 2015;7:1292–312. doi: 10.3390/cancers7030838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thakar PH, Han LY, Kamat AA, et al. Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat Med. 2006;12:939–44. doi: 10.1038/nm1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creed SJ, Le CP, Hassan M, et al. β2-Adrenoceptor signaling regulates invadopodia formation to enhance tumor cell invasion. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:145. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0655-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang J, Li Z, Lu L, Cho CH. β-Adrenergic system, a backstage manipulator regulating tumour progression and drug target in cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23:533–42. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang EV, Sood AV, Chen M, et al. Norepinephrine up-regulates the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, matrix metalloproteinase (mmp)–2, and mmp-9 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10357–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choy C, Raytis JL, Smith DD, et al. Inhibition of β2-adrenergic receptor reduces triple-negative breast cancer brain metastases: the potential benefit of perioperative β-blockade. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:3135–42. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang D, Ma QY, Hu HT, Zhang M. β2-Adrenergic antagonists suppress pancreatic cancer cell invasion by inhibiting creb, nfκb and AP-1. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:19–29. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.1.11944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo K, Ma Q, Wang L, et al. Norepinephrine-induced invasion by pancreatic cancer cells is inhibited by propranolol. Oncol Rep. 2009;22:825–30. doi: 10.3892/or_00000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baselga J. The egfr as a target for anticancer therapy—focus on cetuximab. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(suppl 4):S16–22. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karapetis C, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker D, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1757–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]