This review focuses on the development of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analyses for detecting predictive biomarkers for metastatic colorectal cancer and highlights prospective clinical trials to demonstrate the usefulness of ctDNA analysis.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Liquid biopsy, Circulating tumor DNA, Clonal evolution, Intratumoral heterogeneity

Abstract

Multiple genomic changes caused by clonal evolution induced by therapeutic pressure and corresponding intratumoral heterogeneity have posed great challenges for personalized therapy against metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) in the past decade. Liquid biopsy has emerged as an excellent molecular diagnostic tool for assessing predominant spatial and temporal intratumoral heterogeneity with minimal invasiveness.

Previous studies have revealed that genomic alterations in RAS, BRAF, ERBB2, and MET, as well as other cancer‐related genes associated with resistance to anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy, can be analyzed with high diagnostic accuracy by circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis. Furthermore, by longitudinally monitoring ctDNAs during anti‐EGFR therapy, the emergence of genomic alterations can be detected as acquired resistance mechanisms in specific genes, mainly those associated with the mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Analysis of ctDNA can also identify predictive biomarkers to immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as mutations in mismatch repair genes, microsatellite instability‐high phenotype, and tumor mutation burden. Some prospective clinical trials evaluating targeted agents for genomic alterations in ctDNA or exploring resistance biomarkers by monitoring of ctDNA are ongoing.

To determine the value of ctDNA analysis for decision‐making by more accurate molecular marker‐based selection of patients and identification of resistance mechanisms to targeted therapies or sensitive biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors, clinical trials must be refined to evaluate the efficacy of study treatment in patients with targetable genomic alterations confirmed by ctDNA analysis, and resistance biomarkers should be explored by monitoring ctDNA in large‐scale clinical trials. In the near future, ctDNA analysis will play an important role in precision medicine for mCRC.

Implications for Practice.

Treatment strategies for metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) are determined according to the molecular profile, which is confirmed by analyzing tumor tissue. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) may overcome the limitations of tissue‐based analysis by capturing spatial and temporal intratumoral heterogeneity of mCRC. Clinical trials must be refined to test the value of ctDNA analysis in patient selection and identification of biomarkers. This review describes ctDNA analysis, which will have an important role in precision medicine for mCRC.

摘要

治疗压力和相应肿瘤内异质性诱发的克隆演变会导致多种基因改变,因此在过去十年间给转移性结直肠癌(mCRC) 的个性化治疗带来极大挑战。液体活检是评估肿瘤内主要时空异质性的极佳微创分子诊断工具。

以往的研究提示,通过循环肿瘤DNA (ctDNA)分析,可对RAS, BRAF, ERBB2和MET以及其它与抗表皮生长因子受体 (EGFR)治疗耐药相关的癌症相关基因的基因组改变进行高诊断准确性分析。此外,在抗EGFR治疗期间通过纵向监测ctDNAs,基因组改变的出现可以被检测为特定基因中的获得性耐药机制,这主要指与丝裂原活化蛋白激酶信号通路相关的基因组改变。ctDNA 分析还能确定免疫检查点抑制剂的预测性生物标志物,如错配修复基因突变、微卫星不稳定性‐高表型和肿瘤基因突变负荷。目前正在展开一些前瞻性临床试验,评估针对ctDNA基因组改变的靶向药物,或通过监测ctDNA探讨耐药生物标志物。

为明确ctDNA分析对于靶向治疗中更准确的基于分子标志物的患者选择和耐药机制识别的价值,或者其对于免疫检查点抑制剂的敏感生物标志物的价值,必须改善临床试验,评估研究治疗方案在经ctDNA分析确定发生靶向基因组改变的患者中的疗效,并且应当展开大规模临床试验,通过监测ctDNA探索耐药性生物标志物。在不久的将来,ctDNA 分析将在mCRC精准医疗中起到重要作用。

实践意义

通过分析肿瘤组织确定分子谱,从而依据分子谱决定转移性结直肠癌(mCRC)的治疗策略。循环肿瘤DNA (ctDNA)分析也许能通过获取mCRC的肿瘤内时空异质性而克服基于组织分析的局限性。必须细化临床试验,以验证ctDNA分析对于患者选择和生物标志物识别的价值。本综述描述了ctDNA分析,这种分析将在转移性结直肠癌的精准医疗中起到重要作用。

Introduction

Over the last 20 years, the clinical outcome of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) has improved because of the increased number of patients who undergo surgical resection of metastatic lesions and the development of systemic therapies, including targeted agents [1]. However, the prognosis for patients with mCRC remains poor, with a median overall survival of approximately 30 months. Although vast efforts and investments have been made in the discovery of novel biomarkers to predict the efficacy of anticancer agents for mCRC, extended RAS, BRAF, and microsatellite instability (MSI) are the only validated predictive biomarkers so far. Further studies are critical to the expansion of the precision medicine armamentarium for patients with mCRC.

Comprehensive molecular analyses of CRC have revealed somatic alterations in multiple genes encoding targetable proteins, including KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, IGF2, IGFR, HER2, HER3, MET, MEK, PIK3CA, AKT, and MTOR [2]. Preclinical and clinical studies are being conducted to determine the role of these molecular abnormalities as predictive and prognostic biomarkers. In addition to identifying potential biomarkers, molecular testing is evolving from the “one test‐one drug” paradigm to multiplex approaches that explore the genomic landscape of a tumor. The evolution of next‐generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has enabled the genotyping of tissue samples for multiple genomic alterations in parallel.

However, tissue‐based NGS has inherent limitations. For example, recent studies revealed that multiple genetic changes can arise because of clonal evolution under treatment pressure in mCRC, resulting in acquired secondary resistance [3]. Therefore, longitudinal surveillance of clonal evolution is required to identify secondary resistance. However, repeated tissue biopsies are expensive and can be difficult to perform because of the inherent risk of complications. Moreover, biopsies or tissue sections represent a single snapshot of the tumor in time and space; therefore, they often fail to detect intratumoral heterogeneity, which is a great challenge for the optimal treatment selection for mCRC [4], [5], [6], [7].

Recent technical advances have enabled analysis of tumor materials obtained from blood or other body fluids. These liquid biopsies can be used to assess the predominant type from intratumoral heterogeneity and overcome the limitations of tissue analyses. Specifically, analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), which is tumor‐derived fragmented DNA released into the blood stream, has been shown to have clinical utility in detecting genetic alterations in various types of cancers, including CRC. A number of studies since the early 2000s have revealed that mutations and/or methylations of ctDNA have independent prognostic value for stage I–III CRC [8]. In patients with mCRC, ctDNA analysis potentially evaluates the disease burden of tumors in mCRC by quantification [9]; this can be used with serial monitoring of ctDNA to predict tumor response during treatment. Indeed, some studies have indicated an association between the decrease of ctDNA levels or mutant allele frequency (MAF) during treatment and tumor response [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Furthermore, evolving technologies such as digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and NGS have expanded the potential for ctDNA analysis, and studies have employed these techniques for targeted therapy of mCRC. In this review, we focus on the development of ctDNA analyses for detecting predictive biomarkers for mCRC and highlight our prospective clinical trials to demonstrate the usefulness of ctDNA analysis.

Identification of Biomarkers Related to Resistance to Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Blockade in mCRC by ctDNA Analyses

The clinical durability of the treatment of mCRC is limited by primary and secondary resistance. Resistant mechanisms in RAS wild‐type patients with mCRC treated with anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy mainly involve alterations of specific genes associated with the mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway [15], [16], [17], [18]. Liquid biopsies can detect these genomic alterations related to primary or acquired resistance to anti‐EGFR therapy in ctDNA. Here, we summarize the utility of ctDNA analysis in detecting these biomarkers of anti‐EGFR therapy resistance in mCRC.

RAS Mutations

Concordance of RAS Status Between Tissue and ctDNA Analysis.

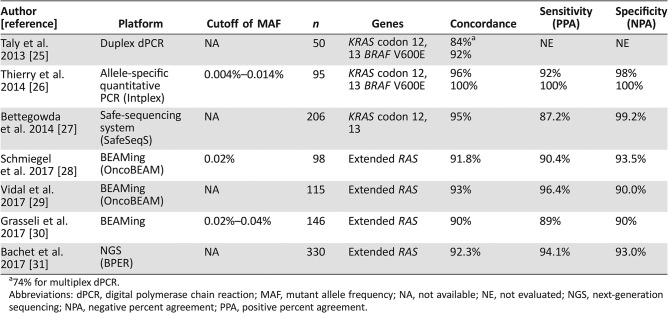

Mutations in extended RAS, that is, KRAS exon 2, 3, or 4 or NRAS exon 2, 3, or 4 are negative predictive biomarkers that have been validated in prospective‐retrospective or retrospective analyses in several randomized studies with anti‐EGFR antibodies for mCRC [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. The utility of detecting RAS mutations by ctDNA analysis has been assessed and validated in several studies with novel liquid biopsy technologies [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31] (Table 1). The first blinded prospective study that evaluated KRAS mutation status in ctDNA using Intplex, a quantitative PCR‐based method using originally designed specific primers for multiple gene mutations [32], in mCRC showed high concordance (94%) and specificity (98%) compared with tissue analyses [26]. The OncoBEAM RAS CRC assay is now available as the only test for detecting RAS mutations in ctDNA with European Conformity in vitro diagnostic (CE‐IVD) study; it can accurately detect up to 34 mutations in exons 2, 3, and 4 of KRAS and NRAS genes, using the BEAMing technology [28], [29]. One of the largest cohort prospective studies revealed that the accuracy raised up to 95.6% in patients with liver metastases [31]. Of note, blood samples were obtained before the start of anti‐EGFR therapy in all these validation studies to avoid detecting acquired RAS mutations as discussed below. In addition, the turnaround time was shown to be 18 days and 7 days for tumor tissue and ctDNA analysis in this study, respectively. This result is consistent with findings from studies evaluating the turnaround time of ctDNA analysis of other cancer types [33], [34], [35] and suggests that ctDNA analysis can help patients with mCRC to quickly receive the optimal targeted therapy.

Table 1. Concordance of RAS mutation statuses between tumor‐tissue analysis and ctDNA analysis.

74% for multiplex dPCR.

Abbreviations: dPCR, digital polymerase chain reaction; MAF, mutant allele frequency; NA, not available; NE, not evaluated; NGS, next‐generation sequencing; NPA, negative percent agreement; PPA, positive percent agreement.

Predictive Value of Mutant RAS in ctDNA for Efficacy of Anti‐EGFR Therapy.

Comparisons of the progression‐free survival (PFS) of patients with mCRC treated with anti‐EGFR therapy using the tissue RAS versus the plasma ctDNA RAS result to determine eligibility of patients for targeted therapy indicated similar PFS following first‐line [29] and second/third‐line treatments [30]. These initial observations are encouraging and suggest that plasma RAS testing could accurately determine the eligibility of RAS wild‐type patients for anti‐EGFR therapy.

However, the application of plasma RAS testing remains an important challenge to develop clinically meaningful thresholds for the RAS MAF in ctDNA for appropriately selecting patients who may benefit from anti‐EGFR therapy. When a low sensitivity threshold of MAF is applied, ctDNA analysis can identify patients with a very low number of RAS mutant cells who could benefit from anti‐EGFR therapy [36]. Indeed, a prospective‐retrospective study showed that a RAS mutation with a MAF detected by ctDNA ≥0.1 was significantly associated with short PFS after anti‐EGFR therapy, whereas the PFS of patients with a RAS mutation with a MAF detected by ctDNA <0.1 was similar to that of the RAS wild‐type [30]. Further investigations are needed to evaluate the efficacy of anti‐EGFR therapy for mCRC with any mutant RAS with low MAF detected by ctDNA harboring wild‐type RAS based on tissue analysis.

Monitoring RAS Mutation by ctDNA Analysis During Anti‐EGFR Therapy.

RAS mutant clones have been identified as drivers of acquired resistance to anti‐EGFR therapy in clinical and preclinical studies [16], [17], [37], [38], [39]. Acquired KRAS mutations have been suggested to emerge not only from the selection of pre‐existing KRAS mutant subclones but also as a result of ongoing mutagenesis in the cancer during anti‐EGFR therapy [17]. Some studies identified RAS mutations in ctDNA after anti‐EGFR therapy. A case series indicated that detection of RAS mutations in the plasma during anti‐EGFR therapy provided early warning of impending resistance, which was confirmed several months later by imaging [40]. A retrospective analysis of ctDNA from mCRC patients refractory to anti‐EGFR therapy showed that KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations were more common than in treatment‐naïve patients and the frequency of acquired KRAS mutations was inversely correlated with the time since last anti‐EGFR therapy [41].

A retrospective analysis of ctDNA from mCRC patients refractory to anti‐EGFR therapy showed that KRAS codon 61 and 146 mutations were more common than in treatment‐naïve patients and the frequency of acquired KRAS mutations was inversely correlated with the time since last anti‐EGFR therapy.

Furthermore, monitoring ctDNA during anti‐EGFR therapy indicated the emergence of acquired RAS mutations as well as alterations in other genes, including MET, ERBB2, FLT3, EGFR, and MEK [42]. Interestingly, the temporal withdrawal of an anti‐EGFR antibody resulted in a decline in KRAS‐mutant alleles, suggesting that sensitivity to anti‐EGFR antibody was restored. These findings warrant prospective studies evaluating the strategy of monitoring genomic alterations, including RAS mutations, by ctDNA analyses and temporarily stopping or rechallenging anti‐EGFR therapy.

BRAF Mutations

BRAF V600E mutation is a strong biomarker for poor prognosis of CRC [43]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the BRAF V600E mutation decreases the likelihood of a response to anti‐EGFR monotherapy [18], [44], [45]. Preclinical studies demonstrated that patients with BRAF V600E‐mutant CRC were highly sensitive to dual inhibition of EGFR and the MAPK signaling pathway [46], [47]; these results have prompted additional clinical studies to evaluate the efficacy of combined inhibition of BRAF and MEK, EGFR, or PI3K in patients with BRAF V600E‐mutant mCRC.

Analysis of BRAF V600E mutation in ctDNA by digital PCR has also been validated; this method was shown to have a high accuracy of nearly 100% for detecting BRAF V600E mutations [26]. In a phase Ib study, reductions in BRAF V600E ctDNA allele fraction predicted improved radiographic responses to vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, cetuximab, and irinotecan [48]. In addition, serial NGS‐based ctDNA analysis identified mutations in MAPK signaling pathway‐related genes (MEK1, ARAF, ERBB2, and EGFR) upon progression. In another phase I/II study of the clinical activity of dabrafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, and panitumumab against BRAF V600E‐mutant CRC, the BRAF V600E‐mutant fraction burden in ctDNA was more markedly reduced by week 4 in responders than in nonresponders and the emergence of RAS mutations in ctDNA was detected in 9 of 22 patients (41%) during disease progression [49].

EGFR Mutations

Somatic mutations in EGFR have been demonstrated as a mechanism of resistance to anti‐EGFR therapy. One study identified a point mutation (S492R) within the EGFR ectodomain (ECD) that arose in a cetuximab‐resistant cell line and demonstrated that panitumumab could block EGFR activation in these mutants [50]. Furthermore, the researchers identified the EGFR S492R mutation in a patient with mCRC after treatment with cetuximab, and panitumumab treatment markedly reduced the size of all lesions in this patient. Another study revealed that several other EGFR ECD mutations such as R451C, K467T, S464L, G465R, and I491M were acquired after treatment with cetuximab; these mutants showed different binding properties from cetuximab and panitumumab [51]. Sym004, a 1:1 mixture of two antibodies against nonoverlapping epitopes of EGFR ECD, has been developed to overcome the resistance to anti‐EGFR therapy and demonstrated tumor shrinkage in patients whose disease progressed after anti‐EGFR therapy, including a patient with EGFR S492R mutation in a phase I trial [52]. However, in a randomized phase II study of Sym004, this agent seemed to be more active in patients with no mutant allele of RAS, BRAF, and EGFR ECD in ctDNA compared with investigator's choice [53]. This result indicates the further need for the development of agents to overcome EGFR ECD mutations.

An analysis of ctDNA using the BEAMing method detected EGFR S492R mutation in 5 of 62 patients (8%) who had acquired resistance to anti‐EGFR antibody after an initial response [41]. Notably, four of five patients with ctDNA EGFR S492R mutation also had newly detected KRAS mutations, suggesting that these mutations were not mutually exclusive. Another analysis of ctDNA revealed that EGFR ECD mutations arose in patients who experienced greater and longer responses to anti‐EGFR therapy compared with patients with acquired RAS mutations [54]. This finding indicates that EGFR ECD mutations are acquired as de novo mutations after anti‐EGFR therapy rather than occurring from pre‐existing low levels of mutations.

ERBB2 (HER2) Amplification

ERBB2 amplifications have been observed in approximately 3% of patients with mCRC [55]. Preclinical studies using a patient‐derived xenograft model of ERBB2‐amplified CRC showed that ERBB2‐amplified CRC was resistant to anti‐EGFR treatment and responded to HER2‐targeted therapy [56], [57]. Consistent with these findings, the frequency of ERBB2 amplifications increase from approximately 3% in treatment‐naïve patients to over 10% in patients administered anti‐EGFR treatment [56]. Clinical studies have investigated the efficacy of combined HER2‐targeted therapies, which showed some clinical benefit [58], [59].

To detect copy number alterations (CNAs), including ERBB2 amplification, in ctDNA, researchers have utilized whole‐genome sequencing methods to evaluate the normalized copy number of the target locus in circulating cell‐free DNA [60]; however, these methods have limited sensitivity because of their low depth. Recently, targeted sequencing approaches have been established to detect CNAs in ctDNA [61]. Guardant360, an NGS‐based ctDNA analysis method that targets cancer‐related genes, was shown to identify CNAs for multiple genes, including ERBB2, EGFR, and MET, with high diagnostic accuracy [62]. In a National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project study, acquired ERBB2 amplifications were detected using this technology in two of eight patients with mCRC, who initially had HER2‐negative tumors and showed progression after anti‐EGFR therapy [63]. Digital PCR methods have also been developed to detect ERBB2 amplifications in ctDNA [64], [65]. We have now conducted the TRIUMPH study, an investigator‐initiated, multicenter, phase II study, to evaluate the efficacy and safety of combination therapy with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in patients with HER2‐positive mCRC [66]. This study enrolls patients with RAS wild‐type in tissue and not only HER2‐positive detected by tissue analysis, but also ERBB2‐amplified and RAS wild‐type tissues confirmed by ctDNA analysis using an NGS‐based method, which has a potential benefit to detect acquired ERBB2 amplification with minimal invasiveness. In addition, monitoring using ctDNA analysis during treatment or after disease progression is conducted to explore the resistance mechanisms to HER2‐targeted therapy in this study.

MET Amplification

MET amplification is also responsible for de novo and acquired resistance to anti‐EGFR therapy for mCRC [67]. Cotreatment with MET inhibitors and cetuximab caused robust and long‐lasting tumor shrinkage in patient‐derived xenograft models of MET‐amplified mCRC. In a study investigating the frequency of MET amplification in a large cohort of patients with mCRC, MET amplifications were detected in 1.7% (10/590) of tumor tissue biopsies tested by both fluorescence in situ hybridization and sequencing in the pretreatment cohort [68]. In contrast, an NGS panel detected MET amplification in the ctDNAs of 22.6% (12/53) of patients who had been treated with anti‐EGFR therapy and showed disease progression, which was not detected in patients with pre‐cetuximab treatment. In addition, this ctDNA NGS method did not detect MET amplification in post‐cetuximab patients with RAS mutations, suggesting that MET amplification is a resistance mechanism exclusive from RAS mutation in anti‐EGFR‐treated patients. Furthermore, novel technologies have been developed to evaluate MET amplification with improved analytical sensitivity, using amplification‐associated rearrangements along with normalized counting‐based approaches [69]. In a phase Ib study of the efficacy of cabozantinib, a multiple receptor kinase inhibitor, and panitumumab in patients with RAS wild‐type mCRC, the combination markedly reduced the tumor volume in a patient in whom MET amplification was detected in ctDNA but not in tissue [70].

ctDNA Analysis for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in mCRC

The emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting Cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte associated protein‐4 and programmed death‐1 (PD‐1)/programmed death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) has facilitated breakthrough developments in cancer immunotherapy; however, most patients with mCRC did not exhibit significant responses to these agents [71], [72], and thus it is necessary to identify novel biomarkers and combination strategies for mCRC.

It has been hypothesized that deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) or mutations inactivating DNA repair genes, such as POLD, POLE, and MYH, could elicit sensitivity toward immune checkpoint inhibitors because of the high tumor neoantigen load caused by hypermutation of the genome. This hypothesis was supported by the results of a clinical trial with pembrolizumab, an anti‐PD‐1 antibody, which indicated an objective response rate of approximately 40% in dMMR mCRC [73]. Another checkpoint inhibitor, nivolumab, also showed that approximately 30% of patients responded to dMMR/MSI‐high (MSI‐H) mCRC in a phase II study [74]. Most recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved pembrolizumab for dMMR/MSI‐H cancers and nivolumab for dMMR/MSI‐H mCRC. International phase III trials are now ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors for dMMR mCRC.

ctDNA analyses can serve as a potential tool for exploring predictive biomarkers of immune checkpoint inhibitors. For example, mutations in MMR genes can be detected by ctDNA analyses along with the MSI‐H phenotype using five mononucleotide markers (BAT‐25, BAT‐26, MONO‐27, NR‐21, and NR‐24) and has been validated for clinical use by Personal Genome Diagnostics using PlasmaSELECT. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) that often co‐occurs with dMMR/MSI‐H is another predictive biomarker but is at times difficult to assess with tumor tissue from patients diagnosed in the metastatic setting. NGS‐based ctDNA analysis may estimate blood TMB that reflects neo‐antigenicity at the time when the blood sample is obtained. Khagi et al. reported that PFS after immune checkpoint inhibitors was significantly better in patients with >3 variant of undetermined significance (VUS) alterations versus ≤3 VUS alterations detected by an NGS‐based ctDNA analysis in a population including patients with mCRC [75]. Some resistance biomarkers of somatic genomic alterations, such as JAK1/2 mutation, EGFR mutation, and MDM2 amplification, may be related to the resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors [76], [77]. Such genomic alterations can also be detected by NGS‐based ctDNA analyses.

ctDNA Analysis‐Adapted Prospective Studies

Clinical Trial Evaluating the Clinical Utility of ctDNA‐Guided Decision‐Making

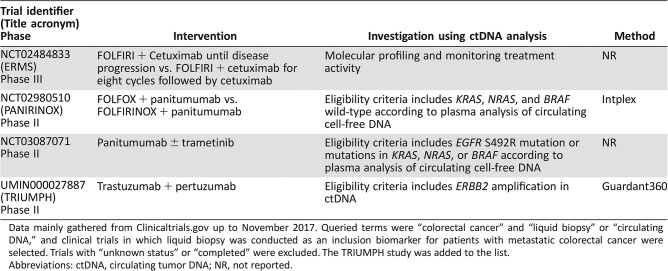

The eligibility criteria in most clinical trials only includes patients with certain genomic alterations based on analysis of tumor tissue. However, the analysis of archival tissue may not accurately reflect clonal evolution under prior therapeutic pressure, and re‐biopsy samples are difficult to obtain from all patients because of the inherent risk of complications. In contrast, liquid biopsy, which is minimally invasive, allows for patient stratification according to the current status of genomic alterations from plasma obtained immediately before enrollment, although the concordance of the broad range of genomic alteration statuses between newly obtained tumor‐tissue analysis and ctDNA analysis remains unclear. To establish the potential value of ctDNA analysis‐guided decision‐making, clinical trials must be refined to test the efficacy of study treatment in patients with targetable genomic alterations confirmed by ctDNA analysis but not analyzing archival tissue. A few studies in which patient selection is based on ctDNA analysis are underway (Table 2).

Table 2. List of clinical trials incorporating ctDNA analysis for patient selection.

Data mainly gathered from Clinicaltrials.gov up to November 2017. Queried terms were “colorectal cancer” and “liquid biopsy” or “circulating DNA,” and clinical trials in which liquid biopsy was conducted as an inclusion biomarker for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer were selected. Trials with “unknown status” or “completed” were excluded. The TRIUMPH study was added to the list.

Abbreviations: ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; NR, not reported.

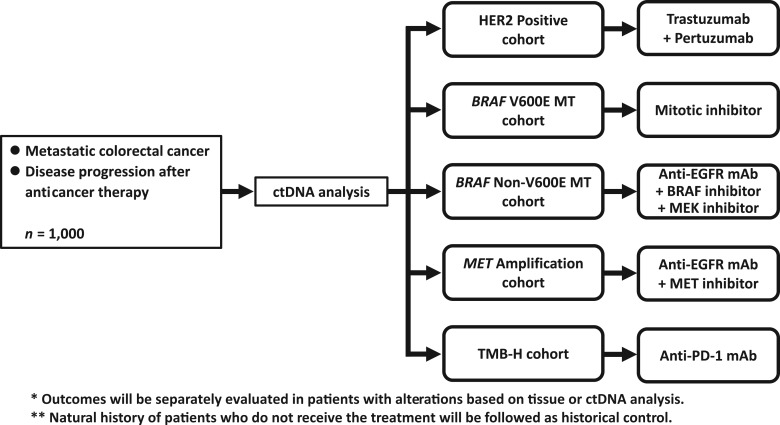

The potential advantage of ctDNA analysis can lead to next‐generation clinical trials, such as basket and umbrella trials based on genomic alterations that reflect spatial and temporal intratumoral heterogeneity. Kim et al. have already reported that a clinical trial using ctDNA‐guided matched therapy showed clinical responses, which was similar to tissue‐based targeted therapy, for patients with non‐small cell lung cancer and gastric cancer [78]. The Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry, an American Society of Clinical Oncology‐sponsored large basket/umbrella trial, accepts patient selection by using ctDNA analysis (NCT02693535). We have planned an umbrella project for mCRC based on the molecular profile based on ctDNA analysis (Fig. 1). Around 1,000 patients with mCRC whose disease progressed after anticancer therapy will be screened by using an NGS‐based ctDNA analysis in this project (UMIN000029315). The patients who have alterations of ERBB2, BRAF V600E, BRAF non‐V600E, or MET or high tumor mutation burden in tumor tissue or ctDNA will be enrolled into each substudy targeting the genomic alteration. In the substudies, the outcomes will be compared between both patient groups with the genomic alteration based on tumor tissue and ctDNA analysis to assess the potential of ctDNA‐guided biomarker selection compared with the standard‐of‐care tissue analysis. Furthermore, natural history will be followed as a historical control of patients with rare genomic alterations targeted in each substudy and compared with the treatment group.

Figure 1.

Schema of a planning umbrella project for metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Patients with mCRC who have disease progression after anticancer therapy will be screened by ctDNA analysis. Trastuzumab and pertuzumab, a mitotic inhibitor, a triplet of anti‐EGFR and BRAF inhibition and MEK inhibition, a doublet of anti‐EGFR and MET inhibition, and anti‐PD‐1 will be tested for each targetable alteration.

Abbreviations: ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; MT, mutant; PD‐1, programmed death‐1; TMB, tumor mutation burden.

Exploratory Study Using ctDNA Analysis in Prospective Clinical Trials

In addition to the potential of appropriate molecular selection of patients, ctDNA analysis can explore the mechanisms of resistance to targeted therapies by monitoring genomic alterations during treatment. Recently, baseline blood samples were prospectively collected and analyzed in large‐scale clinical trials to identify novel biomarkers. These exploratory analyses with large‐scale trials have the advantage of being able to analyze novel biomarkers in similar populations as intention‐to‐treat populations because of the ease of collecting samples. In the CORRECT trial, which demonstrated the survival benefit of regorafenib in salvage line for mCRC, mutations in KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA in ctDNA obtained from the plasma of enrolled patients were analyzed by BEAMing technology [79]. BEAMing analysis of plasma revealed consistent trends toward a clinical benefit with regorafenib irrespective of KRAS and PIK3CA mutational status in ctDNA. Interestingly, although the clinical benefit of regorafenib was not significantly affected by circulating DNA concentrations in the plasma, a high baseline circulating DNA concentration was associated with poor prognosis in the placebo group. In the ASPECCT study, a phase III study of panitumumab versus cetuximab in patients previously treated with KRAS exon 2‐wild‐type mCRC, ctDNAs were analyzed by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) and NGS. Consistent with the difference in binding properties between the anti‐EGFR antibodies, ctDNA analysis by ddPCR revealed that cetuximab treatment resulted in more frequent emergence of EGFR S492R mutations in the plasma than panitumumab treatment [80]. NGS‐based monitoring of the mutational landscape in ctDNAs of 238 patients receiving panitumumab showed that at least 10% of the subjects acquired mutations during therapy, both inside and outside of the EGFR pathway [81]. The PARADIGM study is a large phase III study that assessed modified FOLFOX6 plus panitumumab or bevacizumab as the first‐line treatment for RAS wild‐type mCRC. Archival formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded tumor tissues and ctDNA samples, which are obtained prior to treatment and at the confirmed disease progression stage from similar population as intention‐to‐treat population, will be analyzed to elucidate mechanisms of primary and secondary resistance to anti‐EGFR and anti‐vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in the first‐line treatment [82].

NGS‐based monitoring of the mutational landscape in ctDNAs of 238 patients receiving panitumumab showed that at least 10% of the subjects acquired mutations during therapy, both inside and outside of the EGFR pathway.

Conclusion

Analysis of ctDNA has emerged as a potential tool for evaluating the complicated biological processes involved in CRC, represented by intratumoral heterogeneity and clonal evolution, given the limited availability of precision medicine for patients with mCRC. The practical advantages, such as minimal invasiveness, rapid turnaround time, and low cost of sampling procedures, enable medical oncologists to promptly guide patients to an optimal therapy and potentially monitor the resistance using multiple sampling to implement changes in the therapy. As reviewed above, although several studies have already suggested the utility of ctDNA analysis for evaluating the spatial and temporal dynamics of tumor clones under therapeutic pressures in mCRC, some limitations have been observed. One major limitation of ctDNA analysis is the sensitivity and specificity versus those of tissue analysis. Some studies identified factors of discordance, such as the site of metastasis (peritoneum and lung), histology (mucinous), administration of treatment prior to blood collection, low tumor burden, absence of a primary tumor, and lower levels of lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, and CA19‐9 [29], [30], [31]. Additionally, ctDNA analysis cannot analyze biomarkers other than genomic alterations, such as microRNAs. Analysis of circulating RNAs, circulating tumor cells, and exosomes may overcome this issue.

Until now, most studies included small cohorts of patients, and thus the value and limitations of ctDNA analysis in clinical practice for mCRC must be validated in well‐designed or large‐scale prospective trials. In conclusion, liquid biopsy analysis of ctDNA is creating a paradigm shift in the molecular diagnosis of mCRC, and researchers should design prospective trials to establish ctDNA analysis‐based personalized therapy to improve patient outcomes.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Andrea Z. Lai, Alexa B. Schrock, Rachel L. Erlich et al. Detection of an ALK Fusion in Colorectal Carcinoma by Hybrid Capture‐Based Assay of Circulating Tumor DNA. The Oncologist 2017;22:774–779.

Abstract

ALK rearrangements have been observed in 0.05%.2.5% of patients with colorectal cancers (CRCs) and are predicted to be oncogenic drivers largely mutually exclusive of KRAS, NRAS, or BRAF alterations. Here we present the case of a patient with metastatic CRC who was treatment naive at the time of molecular testing. Initial ALK immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was negative, but parallel genomic profiling of both circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and tissue using similar hybrid capture‐based assays each identified an identical STRN‐ALK fusion. Subsequent ALK IHC staining of the same specimens was positive, suggesting that the initial result was a false negative. This report is the first instance of an ALK fusion in CRC detected using a ctDNA assay.

Key Points.

- Current guidelines for colorectal cancer (CRC) only recommend genomic assessment of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and microsatellite instability (MSI) status.

- ALK rearrangements are rare in CRC, but patients with activating ALK fusions have responded to targeted therapies.

- ALK rearrangements can be detected by genomic profiling of ctDNA from blood or tissue, and this methodology may be informative in cases where immunohistochemistry (IHC) or other standard testing is negative.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Yoshiaki Nakamura, Takayuki Yoshino

Collection and/or assembly of data: Yoshiaki Nakamura, Takayuki Yoshino

Data analysis and interpretation: Yoshiaki Nakamura, Takayuki Yoshino

Manuscript writing: Yoshiaki Nakamura, Takayuki Yoshino

Final approval of manuscript: Yoshiaki Nakamura, Takayuki Yoshino

Disclosures

Yoshiaki Nakamura: Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. (H); Takayuki Yoshino: Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K. (H), GlaxoSmithKline plc., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd. (RF).

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1. Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2016;27:1386–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Network . Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012;487:330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Misale S, Di Nicolantonio F, Sartore‐Bianchi A et al. Resistance to anti‐EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer: From heterogeneity to convergent evolution. Cancer Discov 2014;4:1269–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uchi R, Takahashi Y, Niida A et al. Integrated multiregional analysis proposing a new model of colorectal cancer evolution. PLoS Genet 2016;12:e1005778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Normanno N, Rachiglio AM, Lambiase M et al. Heterogeneity of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in metastatic colorectal cancer and potential effects on therapy in the CAPRI GOIM trial. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1710–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Russo M, Siravegna G, Blaszkowsky LS et al. Tumor heterogeneity and lesion‐specific response to targeted therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov 2016;6:147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mamlouk S, Childs LH, Aust D et al. DNA copy number changes define spatial patterns of heterogeneity in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun 2017;8:14093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fan G, Zhang K, Yang X et al. Prognostic value of circulating tumor DNA in patients with colon cancer: Systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0171991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tie J, Kinde I, Wang Y, et al. Circulating tumor DNA as an early marker of therapeutic response in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1715–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Montagut C, Siravegna G, Bardelli A. Liquid biopsies to evaluate early therapeutic response in colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1525–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spindler KL, Pallisgaard N, Vogelius I et al. Quantitative cell‐free DNA, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in plasma from patients with metastatic colorectal cancer during treatment with cetuximab and irinotecan. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:1177–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spindler KL, Pallisgaard N, Andersen RF et al. Changes in mutational status during third‐line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer–Results of consecutive measurement of cell free DNA, KRAS and BRAF in the plasma. Int J Cancer 2014;135:2215–2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garlan F, Laurent‐Puig P, Sefrioui D et al. Early evaluation of circulating tumor DNA as marker of therapeutic efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients (PLACOL study). Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:5416–5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee JJ, Palma JF, Yao L et al. Correlation of pre‐ and post‐induction plasma mutant allele fraction with progression‐free survival (PFS) in STEAM, a prospective, randomized, multicenter study in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). J Clin Oncol 2017;35(suppl 15):e15118a. [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy‐refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diaz LA Jr, Williams RT, Wu J et al. The molecular evolution of acquired resistance to targeted EGFR blockade in colorectal cancers. Nature 2012;486:537–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Misale S, Yaeger R, Hobor S et al. Emergence of KRAS mutations and acquired resistance to anti‐EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Nature 2012;486:532–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bertotti A, Papp E, Jones S et al. The genomic landscape of response to EGFR blockade in colorectal cancer. Nature 2015;526:263–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S et al. Panitumumab‐FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patterson SD, Peeters M, Siena S et al. Comprehensive analysis of KRAS and NRAS mutations as predictive biomarkers for single agent panitumumab (pmab) response in a randomized, phase III metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) study (20020408). J Clin Oncol 2013;31(suppl 15):3617a. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Cutsem E, Lenz HJ, Köhne CH et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peeters M, Oliner KS, Price TJ et al. Analysis of KRAS/NRAS mutations in a phase III study of panitumumab with FOLFIRI compared with FOLFIRI alone as second‐line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:5469–5479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bokemeyer C, Köhne CH, Ciardiello F et al. FOLFOX4 plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:1243–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stintzing S, Modest DP, Rossius L et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE‐3): A post‐hoc analysis of tumour dynamics in the final RAS wild‐type subgroup of this randomised open‐label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1426–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taly V, Pekin D, Benhaim L et al. Multiplex picodroplet digital PCR to detect KRAS mutations in circulating DNA from the plasma of colorectal cancer patients. Clin Chem 2013;59:1722–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thierry AR, Mouliere F, El Messaoudi S et al. Clinical validation of the detection of KRAS and BRAF mutations from circulating tumor DNA. Nat Med 2014;20:430–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early‐ and late‐stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:224ra224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmiegel W, Scott RJ, Dooley S et al. Blood‐based detection of RAS mutations to guide anti‐EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer patients: Concordance of results from circulating tumor DNA and tissue‐based RAS testing. Mol Oncol 2017;11:208–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vidal J, Muinelo L, Dalmases A et al. Plasma ctDNA RAS mutation analysis for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2017;28:1325–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grasselli J, Elez E, Caratù G et al. Concordance of blood‐ and tumor‐based detection of RAS mutations to guide anti‐EGFR therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2017;28:1294–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bachet JB, Bouche O, Taïeb J et al. RAS mutations concordance in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and tissue in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): RASANC, an AGEO prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(suppl 15):11509a. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mouliere F, El Messaoudi S, Pang D et al. Multi‐marker analysis of circulating cell‐free DNA toward personalized medicine for colorectal cancer. Mol Oncol 2014;8:927–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heitzer E, Ulz P, Belic J, et al. Tumor‐associated copy number changes in the circulation of patients with prostate cancer identified through whole‐genome sequencing. Genome Med 2013;5:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sacher AG, Paweletz C, Dahlberg SE et al. Prospective validation of rapid plasma genotyping for the detection of EGFR and KRAS mutations in advanced lung cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1014–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Paweletz CP, Sacher AG, Raymond CK et al. Bias‐corrected targeted next‐generation sequencing for rapid, multiplexed detection of actionable alterations in cell‐free DNA from advanced lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:915–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thierry AR, El Messaoudi S, Mollevi C et al. Clinical utility of circulating DNA analysis for rapid detection of actionable mutations to select metastatic colorectal patients for anti‐EGFR treatment. Ann Oncol 2017;28:2149–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andreou A, Kopetz S, Maru DM et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFOX for primary colorectal cancer is associated with increased somatic gene mutations and inferior survival in patients undergoing hepatectomy for metachronous liver metastases. Ann Surg 2012;256:642–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Otsuka K, Satoyoshi R, Nanjo H et al. Acquired/intratumoral mutation of KRAS during metastatic progression of colorectal carcinogenesis. Oncol Lett 2012;3:649–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Misale S, Arena S, Lamba S et al. Blockade of EGFR and MEK intercepts heterogeneous mechanisms of acquired resistance to anti‐EGFR therapies in colorectal cancer. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:224ra226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Trojan J, Klein‐Scory S, Koch C et al. Clinical application of liquid biopsy in targeted therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer. Case Rep Oncol Med 2017;2017:6139634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Morelli MP, Overman MJ, Dasari A et al. Characterizing the patterns of clonal selection in circulating tumor DNA from patients with colorectal cancer refractory to anti‐EGFR treatment. Ann Oncol 2015;26:731–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Siravegna G, Mussolin B, Buscarino M et al. Clonal evolution and resistance to EGFR blockade in the blood of colorectal cancer patients. Nat Med 2015;21:795–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J et al. Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 2011;117:4623–4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pietrantonio F, Petrelli F, Coinu A et al. Predictive role of BRAF mutations in patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving cetuximab and panitumumab: A meta‐analysis. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rowland A, Dias MM, Wiese MD et al. Meta‐analysis of BRAF mutation as a predictive biomarker of benefit from anti‐EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy for RAS wild‐type metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2015;112:1888–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature 2012;483:100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Corcoran RB, Ebi H, Turke AB et al. EGFR‐mediated re‐activation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer Discov 2012;2:227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hong DS, Morris VK, El Osta B et al. Phase IB study of vemurafenib in combination with irinotecan and cetuximab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with BRAFV600E mutation. Cancer Discov 2016;6:1352–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Corcoran RB, André T, Yoshino T et al. Efficacy and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis of the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib (D), MEK inhibitor trametinib (T), and anti‐EGFR antibody panitumumab (P) in patients (pts) with BRAF V600Er. g hepateRAFm) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Ann Oncol 2016;27(suppl 6):4550–4550. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Montagut C, Dalmases A, Bellosillo B et al. Identification of a mutation in the extracellular domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor conferring cetuximab resistance in colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2012;18:221–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arena S, Bellosillo B, Siravegna G et al. Emergence of multiple EGFR extracellular mutations during cetuximab treatment in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2157–2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dienstmann R, Patnaik A, Garcia‐Carbonero R et al. Safety and activity of the first‐in‐class Sym004 anti‐EGFR antibody mixture in patients with refractory colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov 2015;5:598–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tabernero J, Ciardiello F, Montagut C et al. Efficacy and safety of Sym004 in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer with acquired resistance to anti‐EGFR therapy: Results of a randomized phase II study (RP2S). Ann Oncol 2017;28(suppl 5):4780–4780. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Van Emburgh BO, Arena S, Siravegna G et al. Acquired RAS or EGFR mutations and duration of response to EGFR blockade in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun 2016;7:13665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Valtorta E, Martino C, Sartore‐Bianchi A et al. Assessment of a HER2 scoring system for colorectal cancer: Results from a validation study. Mod Pathol 2015;28:1481–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bertotti A, Migliardi G, Galimi F et al. A molecularly annotated platform of patient‐derived xenografts (“xenopatients”) identifies HER2 as an effective therapeutic target in cetuximab‐resistant colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov 2011;1:508–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Leto SM, Sassi F, Catalano I et al. Sustained inhibition of HER3 and EGFR is necessary to induce regression of HER2‐amplified gastrointestinal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:5519–5531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sartore‐Bianchi A, Trusolino L, Martino C et al. Dual‐targeted therapy with trastuzumab and lapatinib in treatment‐refractory, KRAS codon 12/13 wild‐type, HER2‐positive metastatic colorectal cancer (HERACLES): A proof‐of‐concept, multicentre, open‐label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hurwitz H, Raghav KPS, Burris HA et al. Pertuzumab + trastuzumab for HER2‐amplified/overexpressed metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): Interim data from MyPathway. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(suppl 4):676a. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Leary RJ, Sausen M, Kinde I et al. Detection of chromosomal alterations in the circulation of cancer patients with whole‐genome sequencing. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:162ra154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kirkizlar E, Zimmermann B, Constantin T et al. Detection of clonal and subclonal copy‐number variants in cell‐free DNA from patients with breast cancer using a massively multiplexed PCR methodology. Transl Oncol 2015;8:407–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lanman RB, Mortimer SA, Zill OA et al. Analytical and clinical validation of a digital sequencing panel for quantitative, highly accurate evaluation of cell‐free circulating tumor DNA. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kim SR, Srinivasan A, Allegra CJ et al. NSABP FC‐7 correlative study: HER2 amplification (amp) in circulating cell‐free DNA (cfDNA) in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) resistant to anti‐EGFR therapy (tx). Cancer Res 2017;77(suppl 13):5684a. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Takegawa N, Yonesaka K, Sakai K et al. HER2 genomic amplification in circulating tumor DNA from patients with cetuximab‐resistant colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2016;7:3453–3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pietrantonio F, Vernieri C, Siravegna G et al. Heterogeneity of acquired resistance to anti‐EGFR monoclonal antibodies in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:2414–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nakamura Y, Okamoto W, Sawada K et al. TRIUMPH Study: A multicenter phase II study to evaluate efficacy and safety of combination therapy with trastuzumab and pertuzumab in patients with HER2‐positive metastatic colorectal cancer (EPOC1602). Ann Oncol 2017;28(suppl 5):612TiP. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bardelli A, Corso S, Bertotti A et al. Amplification of the MET receptor drives resistance to anti‐EGFR therapies in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov 2013;3:658–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Raghav K, Morris V, Tang C et al. MET amplification in metastatic colorectal cancer: An acquired response to EGFR inhibition, not a de novo phenomenon. Oncotarget 2016;7:54627–54631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Diaz LA Jr, Sausen M, Fisher GA et al. Insights into therapeutic resistance from whole‐genome analyses of circulating tumor DNA. Oncotarget 2013;4:1856–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Strickler JH, Rushing CN, Uronis HE et al. Phase Ib study of cabozantinib plus panitumumab in KRAS wild‐type (WT) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). J Clin Oncol 2016;34(suppl 15):3548a. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chung KY, Gore I, Fong L et al. Phase II study of the anti‐cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐associated antigen 4 monoclonal antibody, tremelimumab, in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3485–3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti‐PD‐1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2443–2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H et al. PD‐1 blockade in tumors with mismatch‐repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2509–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair‐deficient or microsatellite instability‐high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): An open‐label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1182–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Khagi Y, Goodman AM, Daniels GA et al. Hypermutated circulating tumor DNA: Correlation with response to checkpoint inhibitor‐based immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:5729–5736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Shin DS, Zaretsky JM, Escuin‐Ordinas H et al. Primary resistance to PD‐1 blockade mediated by JAK1/2 mutations. Cancer Discov 2017;7:188–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kato S, Goodman A, Walavalkar V et al. Hyperprogressors after immunotherapy: Analysis of genomic alterations associated with accelerated growth rate. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:4242–4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kim ST, Banks KC, Lee SH et al. Prospective feasibility study for using cell‐free circulating tumor DNA–guided therapy in refractory metastatic solid cancers: An interim analysis. JCO Precis Oncol 2017;1:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tabernero J, Lenz HJ, Siena S et al. Analysis of circulating DNA and protein biomarkers to predict the clinical activity of regorafenib and assess prognosis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective, exploratory analysis of the CORRECT trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:937–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Price TJ, Newhall K, Peeters M et al. Prevalence and outcomes of patients (pts) with EGFR S492R ectodomain mutations in ASPECCT: Panitumumab (pmab) vs. cetuximab (cmab) in pts with chemorefractory wild‐type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). J Clin Oncol 2015;33(suppl 3):740a. 25605841 [Google Scholar]

- 81. Boedigheimer M, Ang A, Price TJ et al. Profiling circulating tumor (ct)DNA mutations after panitumumab treatment in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) from the phase III ASPECCT study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(suppl 15):3523a. 28872926 [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yoshino T, Uetake H, Tsuchihara K et al. Rationale for and design of the PARADIGM study: Randomized phase III study of mFOLFOX6 plus bevacizumab or panitumumab in chemotherapy‐naive patients with RAS (KRAS/NRAS) wild‐type, metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2017;16:158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]