Abstract

Ovarian carcinoma histotypes are critical for research and patient management and currently assigned by a combination of histomorphology +/− ancillary immunohistochemistry (IHC). We aimed to validate the previously described IHC algorithm (Calculator of Ovarian carcinoma Subtype/histotype Probability version 3, COSPv3) in an independent population-based cohort, and to identify problem areas for IHC predictions. Histotype was abstracted from cancer registries for eligible ovarian carcinoma cases diagnosed from 2002–2011 in Alberta and British Columbia, Canada. Slides were reviewed according to WHO 2014 criteria, tissue microarrays were stained with and scored for the eight COSPv3 IHC markers, and COSPv3 histotype predictions were calculated. Discordant cases for review and COSPv3 prediction were arbitrated by integrating morphology with IHC results. The integrated histotype (n=880) was then used to identify areas of inferior COSPv3 performance. Review histotype and integrated histotype demonstrated 93% agreement suggesting that IHC information revises expert review in up to 7% of cases. There was also 93% agreement between COSPv3 prediction and integrated histotype. COSPv3 errors predominated in four areas: endometrioid versus clear cell (N=23), endometrioid versus low-grade serous (N=15), endometrioid versus high-grade serous (N=11), and high-grade versus low-grade serous (N=6). Most problems were related to Napsin A-negative clear cell, WT1-positive endometrioid, and p53 IHC wild-type high-grade serous carcinomas. Although 93% of COSPv3 prediction accuracy was validated, some histotyping required integration of morphology with ancillary test results. Awareness of these limitations will avoid overreliance on IHC and misclassification of histotypes for research and clinical management.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, histotype, COSP, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Ovarian carcinoma histotypes are considered different diseases (1) and accurate ovarian carcinoma histotyping is critical for research and clinical management. For example, treatment specific management includes: PARP inhibitors for recurrent high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC); immunotherapy for endometrioid (EC) mismatch repair deficient cancer (2–4) and hormonal therapy for low-grade serous (LGSC) (5) and for certain disease stages of EC (6, 7). Ovarian carcinoma histotypes are reproducible if ancillary immunohistochemistry (IHC) is judiciously applied to cases with ambiguous morphology (8–12). We have developed IHC algorithms and prediction models for the five major histotypes: HGSC, LGSC, EC, clear cell carcinoma (CCC), and mucinous carcinoma (MC). The accuracy varies by the number of markers from 88% for the simple 4-marker algorithm to 93% for the 8 marker Calculator of Ovarian carcinoma Subtype/histotype Probability version 3 (COSPv3) prediction model (13). However, a small percentage of histotypes remain incorrectly classified despite these IHC-based approaches.

Given the importance of accurate and reproducible histotyping, the objective of the current study was to validate COSPv3 with an independent cohort of ovarian carcinomas and to identify and describe the limitations of ancillary IHC for classification.

Materials and Methods

Cohort description

COSPv3 was developed on a training set of N=1762 cases (13). The validation set is from the Ovarian Cancer in Alberta and British Columbia (OVAL-BC) study described previously (14). Briefly, OVAL-BC recruited incident, histologically-confirmed cases of ovarian cancer from 2001–2012 (BC) and 2005–2011 (AB) from provincial cancer registries. Eligible cases were: 1) diagnosed with incident ovarian tumors; 2) residents of the provinces; 3) age 20–79 years (40–79 in AB); 4) English-speaking; 5) alive at study contact; and, 6) able to complete an interview/self-administered questionnaire. Cases had no previous cancer except non-melanoma skin cancer. A total of 2522 cases were eligible and 1505 (60%) provided signed informed consent. The cancer registry histotype was assessed from the ICD-O code, which represents the original treatment guiding diagnosis established by a mix of academic and community pathologists with little use of immunohistochemistry at the time. Review histotype was established by central review hematoxylin and eosin slides using contemporary WHO 2014 criteria (10) without use of immunohistochemistry for 979 cases.

COSPv3

Tissue micro-arrays (TMAs) containing 2 0.6 mm cores (for cases from BC) or 3 0.6 mm cores (AB) were constructed for 945. Of these, 942 women had eligible histotypes, but 52 overlapped with the training set and were excluded, leaving 890 new cases in the OVAL-BC validation cohort. Using protocols described previously (13), 4 micron sections of the were stained with the 8 markers for COSPv3: WT1, p53, Napsin A, PR, p16, ARID1A, TFF3, and Vimentin. Scoring was done by two pathologists (SL, MK). As previously described (13), results were interpreted for: WT1, Napsin A, PR and ARID1A as present (i.e. expression in >1% of tumor cells); p53 as abnormal (mutant-type overexpression or complete nuclear absence with retained internal control or cytoplasmic staining (15)) and p16 as block (i.e. expression in >90% of tumor cells); and, TFF3 and Vimentin as diffuse (i.e. >50% expression).

Integrated histotype

Discordant cases between review histotype and COSPv3 prediction were subjected to arbitration. Arbitration was performed by a pathologist (MK) re-reviewing available histological sections (median: one slide, range 1–10) with knowledge of the IHC marker profile and COSPv3 prediction probability. An integrated histotype was assigned by evaluating histotype-specific morphological and IHC information.

Statistics

The same multinomial logistic regression model of the 8 IHC markers used for the test cohort of N=1762 cases was used to predict the five major histotypes in the OVAL-BC validation cohort. Missing IHC marker data in the OVAL-BC cohort were handled by performing multiple imputation using an approximate Bayesian framework implemented in the R “mi” package (16). The probability of each predicted histotype was averaged over 1000 imputed datasets. The histotype with the largest average probability was considered the algorithm predicted histotype for each patient. We used a Sankey diagram to describe the patterns of the histotype changes from cancer registry to histotype review to integrated histotype. Contingency tables and percentages were used to summarize the concordance among different histotypes. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank tests were used to compare the overall survival patient outcome by different integrated histotypes. Median overall survival time and 95% confidence intervals were summarized. All statistical analyses were performed using R (17).

Results

Changes in histotype from cancer registry to review

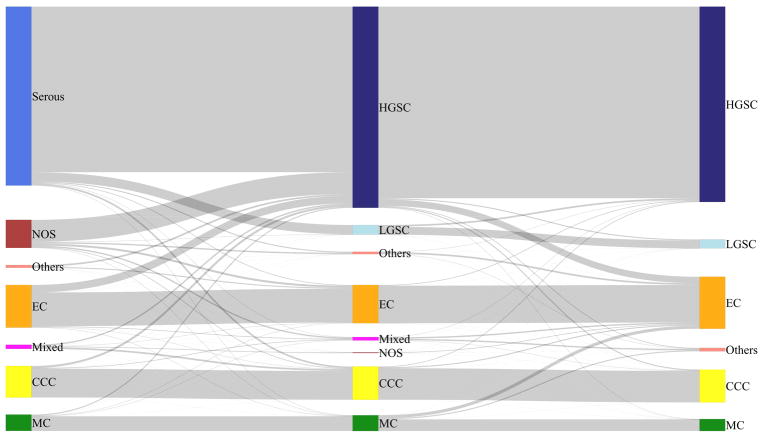

Major changes occurred between the cancer registry histotype based on the 2003 and prior WHO classification criteria and the review histotype based on the 2014 WHO classification (Figure 1). As expected, cancer registry diagnoses of serous or carcinoma not otherwise specified were assigned by review to HGSC in 92.5% and 78% of cases, respectively (Table 1). Additionally, 18% of EC (N=22) were reclassified to HGSC by review. Due to the differences in histotype definitions it was not possible to apply agreement statistics to cancer registry and review histotype (8).

Figure 1.

Sankey diagram showing changes in histotype from cancer registry (left) via review (middle) to integrated histotype (right). The cancer registry serous carcinoma split into high-grade serous (HGSC) and low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC). The majority of carcinomas not otherwise specified (NOS) and some endometrioid carcinomas (EC) were classified as HGSC on review. In contrast, most reclassification from review to integrated histotype were reclassifications of HGSC to EC and MC to EC. CCC – clear cell carcinoma, MC – mucinous carcinoma.

Table 1.

Concordance between cancer registry and review histotype

| N (% row) | CCC | EC | HGSC | LGSC | MC | Mixed | NOS | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCC | 84 (91.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 92 |

| EC | 1 (0.8) | 99 (79.2) | 22 (17.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 125 |

| MC | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (6.2) | 0 (0) | 43 (89.6) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 48 |

| Mixed | 5 (41.7) | 1 (8.3) | 4 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 12 |

| NOS | 2 (2.4) | 6 (7.3) | 64 (78) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.9) | 82 |

| Others | 0 (0) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 |

| Serous | 5 (1) | 2 (0.4) | 484 (92.5) | 27 (5.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.6) | 523 |

| Total | 97 | 112 | 588 | 28 | 46 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 890 |

CCC, clear cell carcinoma; EC, endometrioid carcinoma; HGSC, high-grade serous carcinoma; LGSC, low-grade serous carcinoma; MC, mucinous carcinoma; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Rows: cancer registry histotype; columns: review histotype.

Changes in histotype from review to COSPv3 to arbitration/integration

At least one IHC marker result was missing for 117 cases and imputation was used for COSPv3 prediction. A flow chart of the study is provided in supplemental Figure S1. Review histotype and COSPv3 prediction were discordant in 119 (13%) of the 890 cases and underwent arbitration. With arbitration, further 10 cases were excluded because they were classified as an ineligible histotype or a rare (18), true mixed ovarian carcinoma resulting in 880 cases with integrated histotype. Arbitration agreed with review in 50/109 (46%), with COSPv3 in 45/119 (41%), and assigned a new histotype in 14/119 (13%) of cases. The final integrated histotype after arbitration agreed with review histotype in 93% of the cases (Table 2). The largest change involved EC with an overall gain of 40 EC for the integrated compared to the review histotype suggesting that IHC aids in avoiding an under-diagnosis of EC (Figure 1, Table 2). Specifically, 19 cases were reclassified from review HGSC to EC by the integrated histotype and of these 19, only seven were originally classified as EC by the cancer registry. Other integrated EC included nine cases reclassified from MC and four from a mixed diagnosis (Figure 1, Table 2).

Table 2.

Concordance between review histotype and integrated histotype

| N (% row) | CCC | EC | HGSC | LGSC | MC | Other: Mixed | Other: NOS | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCC | 92 (94.8) | 3 (3.1) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 97 |

| EC | 0 (0) | 110 (98.2) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 112 |

| HGSC | 3 (0.5) | 19 (3.2) | 560 (95.2) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 588 |

| LGSC | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (17.9) | 23 (82.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 28 |

| MC | 0 (0) | 9 (19.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 34 (73.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.5) | 46 |

| Mixed | 1 (10) | 4 (40) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 |

| NOS | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 |

| Others | 0 (0) | 5 (71.4) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 7 |

| Total | 96 | 152 | 571 | 26 | 35 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 890 |

CCC, clear cell carcinoma; EC, endometrioid carcinoma; HGSC, high-grade serous carcinoma; LGSC, low-grade serous carcinoma; MC, mucinous carcinoma; NOS, not otherwise specified..

Rows: review histotype; columns: integrated histotype.

Comparison of integrated histotype with COSPv3 predictions

To validate the accuracy of COSPv3 in this independent dataset, we compared the agreement between integrated histotype with the COSPv3 predictions (Table 3). The overall accuracy for COSPv3 was 93% for the entire dataset including cases with imputed data for missing scores. The accuracy was higher (98%) for cases with a ≥70% prediction probability than that for cases (59%) with < 70% prediction probability (supplemental Table S1 and S2). COSPv3 accuracy for the 782 cases without imputation was 93% compared to 91% for the 98 cases with at least one marker imputed. Within the group of cases with imputed data, the accuracy decreased from 92% for cases who had a maximum of three markers imputed to 86% for cases with four or more markers imputed (Table S3–S6). The agreement between COSPv3 and integrated histotype varied across the histotypes with the lowest in LGSC and the highest in HGSC (Table 3).

Table 3.

Concordance between COSPv3 prediction and integrated histotype

| N (% rows) | CCC | EC | HGSC | LGSC | MC | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCC | 82 (86.3) | 12 (12.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 95 |

| EC | 11 (8.3) | 117 (88) | 3 (2.3) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 133 |

| HGSC | 2 (0.3) | 8 (1.4) | 562 (97.7) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 575 |

| LGSC | 0 (0) | 13 (31.7) | 5 (12.2) | 23 (56.1) | 0 (0) | 41 |

| MC | 1 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 33 (91.7) | 36 |

| Total | 96 | 152 | 571 | 26 | 35 | 880 |

CCC, clear cell carcinoma; EC, endometrioid carcinoma; HGSC, high-grade serous carcinoma; LGSC, low-grade serous carcinoma; MC, mucinous carcinoma. Rows: COSPv3; columns: integrated histotype.

Problem areas for COSPv3 histotype prediction

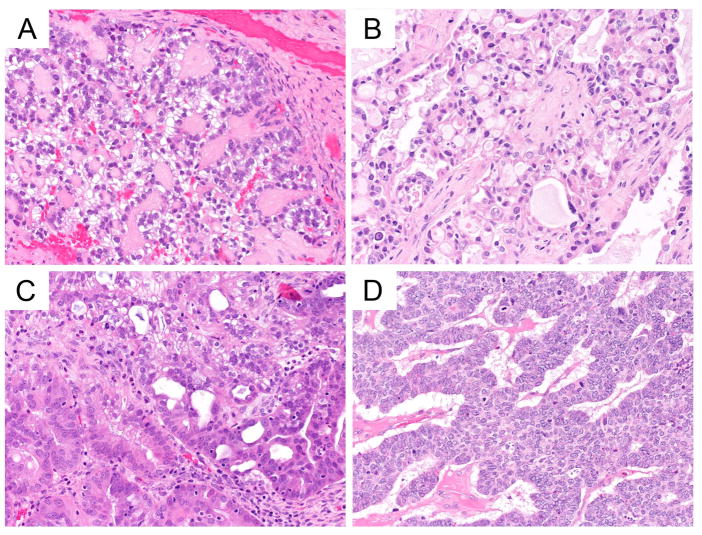

There were four problem areas in which COSPv3 errors occurred. In the first, EC vs CCC, COSPv3 predicted 11 cases as EC with an average probability of 63.8% (compared to 27.3% for CCC); these cases were integrated as CCC. IHC characteristics included Napsin A negative (10/11), PR negative (9/10), ARID1A absence (6/11) and Vimentin diffuse staining (9/10). Morphologically, all these cases were prototypical CCC (Figure 2A, B), indicating that a lack of Napsin A expression in combination with diffuse Vimentin staining can lead to a false IHC-based prediction of EC. Conversely, COSPv3 predicted 12 cases as CCC with an average probability of 51.2% (compared to 32.8% for EC); these cases were integrated as EC. IHC characteristics included Napsin A negative (10/12), PR negative (10/12), ARID1A absence (4/12), and Vimentin non-diffuse staining (11/12). Apart from the absence of ARID1A expression, these cases demonstrated a nonspecific IHC profile indicating a need for a more sensitive EC marker than PR. The morphological diagnoses of these tumors were challenging, noted by the variety of non-EC diagnosis by review histotype including seromucinous, MC and HGSC but not CCC (Figure 2C, D).

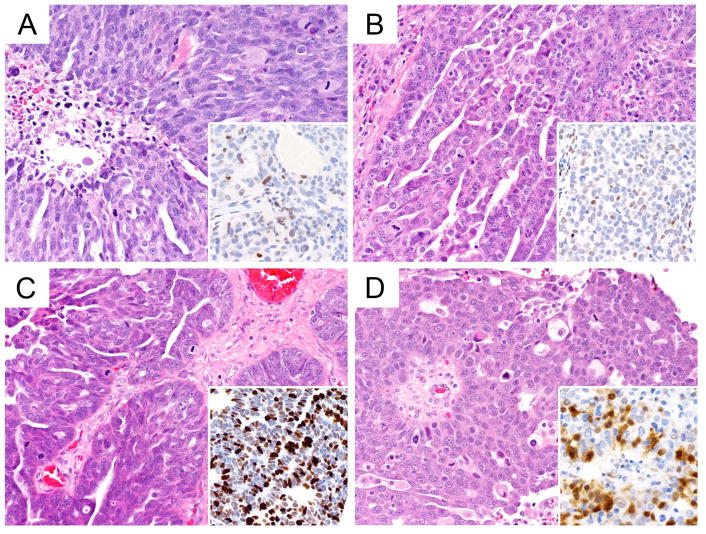

Figure 2.

COSPv3 prediction errors: clear cell versus endometrioid carcinoma.

A, B, Clear cell carcinomas showing typical clear cell morphology with hyaline stromal changes. COSPv3 falsely predicted EC because of absence of Napsin A expression and diffuse Vimentin expression.

C, D, Endometrioid carcinomas with focal secretory changes (C) and sex cord like architecture (D). COSPv3 falsely predicted CCC despite absence of Napsin A but based on absence of ARID1A and PR.

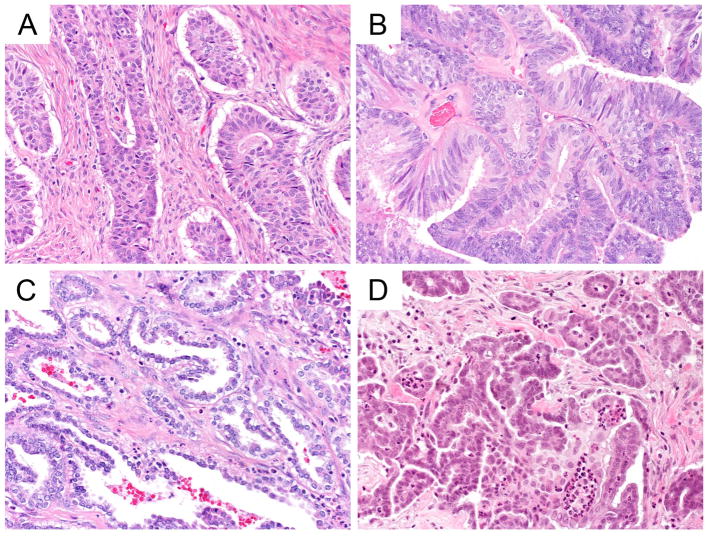

In the second area, for EC vs LGSC, COSPv3 predicted 13 cases as LGSC with an average probability of 55.2% (compared to 24.4% for EC); these cases were integrated as EC. All 13 cases were WT1 positive, one case had loss of ARID1A, and 6/12 showed diffuse Vimentin expression. However, morphologically these cases were all typical EC without evidence of LGSC features (Figure 3A, B, C). The COSPv3 predictions were driven by WT1 positive expression indicating a specificity issue of WT1 for serous only. Conversely, COSPv3 predicted two cases as EC with an average probability of 71.9% (compared to 6.0% for LGSC); these cases were integrated as LGSC. One case had three imputed markers, the other showed presence of WT1 in combination with diffuse TFF3 expression. TFF3 highlights mucinous differentiation, which can occur in LGSC (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

COSPv3 prediction errors: endometrioid versus low-grade serous carcinoma.

A, B, C, Endometrioid carcinomas showing sex cord like (A), glandular (B, C) morphology with secretory changes in C. COSPv3 falsely predicted LGSC owing to WT1 expression in these cases.

D, Low-grade serous carcinoma showing micropapillary architecture with some cytoplasmic mucin. COSPv3 falsely predicted EC owing to diffuse expression of the mucinous markers TFF3.

In the third area, for EC vs HGSC, COSPv3 predicted eight cases as HGSC with an average probability of 83.9% (compared to 6.1% for EC); these cases were integrated as EC. Five cases (or 3.3% of all EC, Table S7, S8) showed the combination of WT1 presence and abnormal p53 staining, results specific for HGSC. However, morphologically, these cases were EC (Figure 4A, B, C). Conversely, COSPv3 predicted three cases as EC with an average probability of 68.3% (compared to 22.7% for HGSC); these cases were consolidated as HGSC. These cases were WT1 negative HGSC (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

COSPv3 prediction errors: endometrioid versus high-grade serous carcinoma.

A, B, C, Endometrioid carcinomas showing glandular (A, B) morphology with mucinous differentiation or solid almost squamoid morphology in C. COSPv3 falsely predicted HGSC owing to the combined presence of WT1 expression and abnormal p53 in these cases.

D, High-grade serous carcinoma showing small papillae within a cystic space. Note, high-grade nuclear atypia. COSPv3 falsely predicted EC owing to lack of WT1 expression.

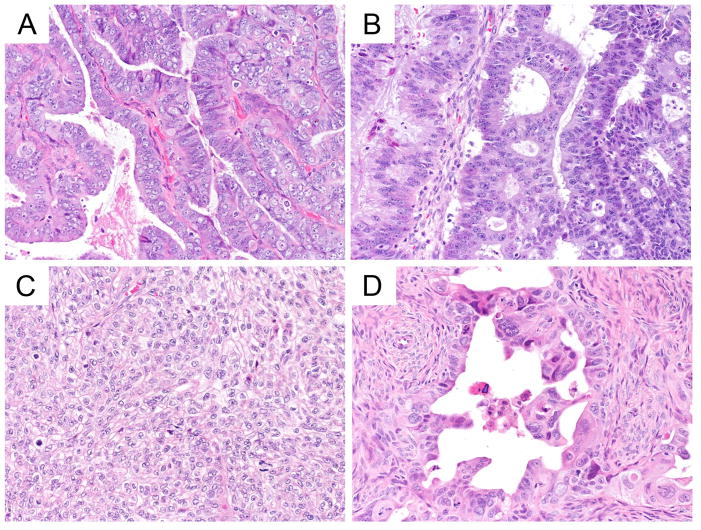

In the fourth area, for HGSC vs LGSC, COSPv3 predicted five cases as LGSC with an average probability of 56.7% (compared to 29.1% for HGSC); these cases were integrated as HGSC. All five cases showed WT1 expression with normal p53 wild type pattern (Figure 5A–D). Re-review for two cases with a scored p53 wild type pattern (Figure 5C and D) indicated an unusual mosaic and focal cytoplasmic pattern of p53 expression. These unusual patterns suggest that there might be an unusual underlying TP53 mutation (e.g. splice site mutations) (15) or the IHC readout was incorrectly interpreted possibly due to antigen degradation in the tissue. Conversely, the one case predicted as HGSC was a LGSC of psammoma-type with seven markers imputed.

Figure 5.

COSPv3 prediction errors: high-grade serous versus low-grade serous carcinoma.

A, B, C, D High-grade serous carcinomas showing slit like spaces (A, B, C) or broad papillary architecture with microcystic spaces (D). COSPv3 falsely predicted LGSC owing to the normal p53 expression. We speculate that normal p53 expression maybe due to truncating or splice site TP53 mutation in A and B or due to antigen degradation leading to misinterpretation in C (perhaps overexpression) and D (perhaps cytoplasmic expression).

Issues from a single IHC marker perspective

While above derived predictions were derived from the complex nominal logistic regression model COSPv3, we use previous knowledge from a hierarchical decision tree (13) to review the most important individual biomarkers: WT1, p53 and Napsin A. First, only 72/96 (75%) CCC stained positive for Napsin A indicating a lack of sufficient sensitivity on small tumor samples in TMAs (Table S9, S10). Second, 21/150 (14%) EC were positive for WT1. However, only five (3.3%) showed WT1 presence and abnormal p53 while this combination was seen in 94.6% of HGSC (Table S8). Third, 12/547 HGSC (2.2%) showed normal p53 wild type expression (Table S10). To see if these marker results impacted survival, we performed a survival analysis for CCC with or without Napsin A expression, for HGSC with abnormal mutant p53 versus normal wild type p53 and for EC with or without WT1 expression. No significant differences were observed (Figure S2).

Survival by cancer registry and integrated histotype

The five-year survival for overall serous carcinomas (cancer registry) was 43.1% and similar to the 42.6% for integrated HGSC (Figure S3, Table S11, S12), but no differences were seen for EC (91.0% vs 87.6%, respectively) or CCC (68.6% vs 68.1%, respectively). The five-year survival for the integrated histotype of LGSC was 63.5%. The largest survival difference was seen for MC, which was better for integrated MC (85.4%) than MC from the cancer registry (78.4%).

Discussion

This study used an independent validation cohort of 880 cases to arrive at the same accuracy found in our previous study (93%) for COSPv3 prediction using an integrated histotype as the benchmark (13). Hence, this study provides further validation that IHC provides a robust independent reference for ovarian carcinoma histotyping. The integration of IHC and arbitration by a pathologist revised the expert review histotype in 7% of cases, mostly by reclassifying cases to EC that were classified as HGSC and MC based on morphology review alone. Thus, integrating IHC avoided an under-diagnosis of EC. Additionally, the agreement between review histotype and intergrated histotype was relatively low for LGSC and MC (82.1% and 73.9%, respectively) suggesting that diagnostic IHC markers are particularly useful for these uncommon histotypes to avoid misclassification and to make results between studies more comparable.

While integration of IHC can improve review histotype, it cannot be used by itself because COSPv3 predictions were discordant with the benchmark integrated histotype in 7% of cases. In daily practice, this should not create a problem unless one over-relies on IHC. We identified four areas of misclassification in IHC prediction. The most common problem was CCC vs EC due to a low frequency of Napsin A expression in this validation cohort (75%), lower than in our test cohort (92%) (13). Although the staining protocol was the same in both situations, there may be intrinsic cohort differences regarding tissue handling (e.g. antigen degradation due to prolonged devitalization times); however, we did not observe such differences with the other markers. While Napsin A expression is found in almost all CCC in small studies using full sections, some cases only showed focal expression (19). Thus having three TMA cores (the test cohort) rather than two cores (predominant in the validation cohort) may explain the lower frequency of Napsin A positivity in the validation cohort. This caveat is also relevant when Napsin A is assessed on small omental core biopsies.

The second problem, EC vs LGSC, arose because of WT1 expression. 14% of EC in the validation cohort were WT1 positive, which is slightly higher than the test cohort (10%) (13). The majority of these ECs (68%) showed diffuse (>50%) WT1 expression commonly found in HGSC (82%). Morphologically, they were prototypical EC without evidence of the typical micropapillary pattern of LGSC. As previously reported, we noted an adenofibromatous background in 8/13 and sex cord-like features in 4/13 of cases in WT1 positive EC (20). Given the limitation of low numbers, there were no survival differences between WT1 negative or positive EC suggesting that there are no overt differences in their biology and clinical behavior.

The third problem is false prediction of HGSC; 3.3% of EC showed the highly specific combination of WT1 presence and abnormal p53 staining normally found in HGSC. If up to 13% of EC are positive for WT1 and 16% are p53 abnormal, then just by chance some EC should harbor co-occurrence of these markers. Correct classification is challenging and relies on endometrioid-like morphological features (overwhelming glandular architecture with smooth luminal borders, abundant cytoplasm including mucinous cytoplasm) and not the IHC profile. Additional ancillary tests such as a combination of IHC and targeted sequencing to identify HGSC-specific (e.g. BRCA1/2 mutation) or EC-specific (CTNNB1 mutation, mismatch repair deficiency, ARID1 loss, etc.) molecular alterations may be useful.

The fourth problem was related to normal wild type pattern p53 staining in HGSC, observed in 2.2% of the HGSC, about half the 5% noted in our test cohort (15). Since TP53 mutations are ubiquitous in HGSC (15), two explanations are likely. First, certain TP53 mutations do not result in an abnormal p53 IHC pattern. We previously reported that truncating or splice site mutation may show normal wild type staining (15) or misinterpretation of p53 IHC may have occurred due to reduced antigenicity, but because of the population-based nature of our study we were not able to re-retrieve blocks to further assess whether full section staining would have clarified the issue. HGSC morphology with p53 wild type pattern suggesting LGSC should alert practicing pathologists to seek a second opinion or further testing (TP53 sequencing is rarely available and has limited sensitivity, p16 block staining is more likely HGSC, or detection of MAPK pathway mutations in favor of LGSC) (11, 21).

While the strength of this study is the population-based nature and comprehensive histotype assessments, there are also limitations. The IHC was assessed on TMAs that are more reflective of small biopsies rather than surgical specimens. However, this is clinically relevant because of the increasing use of pretreatment biopsies for a histotype diagnosis to support primary surgery (for LGSC, CCC, MC, EC) or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (for HGSC) as the initial preferred treatment option (22). While the arbitration process used in this study reflects current clinical practice in which histotyping is performed integrating morphology and IHC results, it is difficult to improve on such an integrated approach using an IHC prediction such as COSPv3 by itself because of the sensitivity and specificity limitations of some of the IHC markers. Until markers or combinations with very high specificity for each histotype are found, the strongest argument for a complete IHC prediction may be for cases with ambiguous morphology, where the diagnosis mainly rests on the IHC profile. Lack of IHC specificity also leads to a scenario where IHC contradicts morphology, yet the morphology shows a classic presentation of the histotype. These cases may be subjected to an extended molecular analysis, but while targeted sequencing for histotype-specific mutations supported the majority of reclassification events in our testing cohort, sequencing was uninformative in 32% of cases (13). Another previous limitation of COSPv3 assessments was the need for a complete data set, but in this study we imputed missing data with only a small decrease in accuracy making this an acceptable approach. This study applied a complex 8 marker panel with at least one marker, i.e. TFF3, not in routine use, however, the conclusions are transferrable to our previously proposed slightly less accurate but simple 4 marker algorithm consisting of WT, p53, Napsin A and PR (13).

Despite some reclassification to an integrated histotype, our results confirm that the outcome information from cancer registries is reliable for the three most common histotypes: serous as a surrogate for HGSC; EC; and, CCC. Since cancer registry classifications do not include LGSC, outcome for this histotype was only available after reclassification. The five-year survival for the 26 LGSC (integrated histotype) in this study was 63.5% similar to previous reports (23). Regarding MC, we observed a slight increase of the five-year survival, probably because a few cases were reclassified to HGSC and some were considered metastatic gastrointestinal carcinoma on review.

Pathology is at the cross roads of integration of morphology with ancillary testing. Nowadays the art of pathology is to decide whether ancillary testing is indicated and if so to interpret the test correctly and incorporate this information without bias. We recommend further workup (second opinion, additional ancillary tests) for cases in which morphology and IHC profile provide contradicting information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Taryn Rutherford, Shuhong Liu and Young Ou for IHC stains. This study was funded by the Cancer Research Society (19319) and CLS internal research support RS11-508. Tissue sample collection of OVAL-BC cohort was supported by National Institutes of Health Cancer Support Grant 2 P30 CA118100-11.

Funding support:

This study was funded by the Cancer Research Society (19319) and CLS internal research support RS11-508. Tissue sample collection of OVAL-BC cohort was supported by National Institutes of Health Cancer Support Grant 2 P30 CA118100-11.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Conception and design: M. Köbel and Linda S. Cook. Provision of study material or patients: A. Brooks-Wilson, Nhu Le, Linda S. Cook. Collection and assembly of data: M. Köbel, S. Lee, C. Blake Gilks, X. Grevers. Data analysis and interpretation: Li Luo, M. Köbel, Linda S. Cook. Manuscript drafting: M. Köbel, X. Grevers, Linda S. Cook. Manuscript revision and final approval of manuscript: M. Köbel, Li Luo, X. Grevers, S. Lee, A. Brooks-Wilson, C. Blake Gilks, Nhu Le, Linda S. Cook.

References

- 1.Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Boyd N, McKinney S, Mehl E, Palmer C, et al. Ovarian carcinoma subtypes are different diseases: implications for biomarker studies. PLoS medicine. 2008;5(12):e232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;375(22):2154–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemery S, Keegan P, Pazdur R. First FDA Approval Agnostic of Cancer Site - When a Biomarker Defines the Indication. The New England journal of medicine. 2017;377(15):1409–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1709968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rambau PF, Duggan MA, Ghatage P, Warfa K, Steed H, Perrier R, et al. Significant frequency of MSH2/MSH6 abnormality in ovarian endometrioid carcinoma supports histotype-specific Lynch syndrome screening in ovarian carcinomas. Histopathology. 2016;69(2):288–97. doi: 10.1111/his.12934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gershenson DM, Bodurka DC, Coleman RL, Lu KH, Malpica A, Sun CC. Hormonal Maintenance Therapy for Women With Low-Grade Serous Cancer of the Ovary or Peritoneum. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(10):1103–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rambau P, Kelemen LE, Steed H, Quan ML, Ghatage P, Kobel M. Association of Hormone Receptor Expression with Survival in Ovarian Endometrioid Carcinoma: Biological Validation and Clinical Implications. International journal of molecular sciences. 2017;18(3) doi: 10.3390/ijms18030515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sieh W, Kobel M, Longacre TA, Bowtell DD, deFazio A, Goodman MT, et al. Hormone-receptor expression and ovarian cancer survival: an Ovarian Tumor Tissue Analysis consortium study. The Lancet Oncology. 2013;14(9):853–62. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70253-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kommoss S, Gilks CB, du Bois A, Kommoss F. Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis: the clinical impact of 15 years of change. British journal of cancer. 2016;115(8):993–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilks CB, Kommoss F. Ovarian Carcinoma Histotypes: Their Emergence as Important Prognostic and Predictive Markers. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2016;30(2):178–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobel M, Bak J, Bertelsen BI, Carpen O, Grove A, Hansen ES, et al. Ovarian carcinoma histotype determination is highly reproducible, and is improved through the use of immunohistochemistry. Histopathology. 2014;64(7):1004–13. doi: 10.1111/his.12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altman AD, Nelson GS, Ghatage P, McIntyre JB, Capper D, Chu P, et al. The diagnostic utility of TP53 and CDKN2A to distinguish ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma from low-grade serous ovarian tumors. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2013;26(9):1255–63. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Baker PM, Ewanowich CA, Arseneau J, Zherebitskiy V, et al. Diagnosis of ovarian carcinoma cell type is highly reproducible: a transcanadian study. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2010;34(7):984–93. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e1a3bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobel M, Rahimi K, Rambau PF, Naugler C, Le Page C, Meunier L, et al. An Immunohistochemical Algorithm for Ovarian Carcinoma Typing. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. 2016;35(5):430–41. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook LS, Leung AC, Swenerton K, Gallagher RP, Magliocco A, Steed H, et al. Adult lifetime alcohol consumption and invasive epithelial ovarian cancer risk in a population-based case-control study. Gynecologic oncology. 2016;140(2):277–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobel M, Piskorz AM, Lee S, Lui S, LePage C, Marass F, et al. Optimized p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate predictor of TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma. The journal of pathology Clinical research. 2016;2(4):247–58. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu-Sung S, Jennifer H, Andrew G, Masanao Y. Multiple Imputation with Diagnostics (mi) in R : Opening Windows into the Black Box. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45(2) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackenzie R, Talhouk A, Eshragh S, Lau S, Cheung D, Chow C, et al. Morphologic and Molecular Characteristics of Mixed Epithelial Ovarian Cancers. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015;39(11):1548–57. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kandalaft PL, Gown AM, Isacson C. The lung-restricted marker napsin A is highly expressed in clear cell carcinomas of the ovary. American journal of clinical pathology. 2014;142(6):830–6. doi: 10.1309/AJCP8WO2EOIAHSOF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart CJ, Brennan BA, Chan T, Netreba J. WT1 expression in endometrioid ovarian carcinoma with and without associated endometriosis. Pathology. 2008;40(6):592–9. doi: 10.1080/00313020802320697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntyre JB, Rambau PF, Chan A, Yap S, Morris D, Nelson GS, et al. Molecular alterations in indolent, aggressive and recurrent ovarian low-grade serous carcinoma. Histopathology. 2017;70(3):347–58. doi: 10.1111/his.13071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoang LN, Zachara S, Soma A, Kobel M, Lee CH, McAlpine JN, et al. Diagnosis of Ovarian Carcinoma Histotype Based on Limited Sampling: A Prospective Study Comparing Cytology, Frozen Section, and Core Biopsies to Full Pathologic Examination. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. 2015;34(6):517–27. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okoye E, Euscher ED, Malpica A. Ovarian Low-grade Serous Carcinoma: A Clinicopathologic Study of 33 Cases With Primary Surgery Performed at a Single Institution. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2016;40(5):627–35. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.