As ongoing debates about Ontario’s sex curriculum show, sex education continues to be controversial. Those in favour of the curriculum implemented by the Liberal government argue that sex education must change as values and practices change. Our research on one of Canada’s first sex education efforts leads us to concur.

The Health League of Canada was one of the country’s most successful voluntary public health groups from the 1920s to the 1960s, but it ultimately faltered by refusing to alter its message to adapt to the growing acceptance of premarital sex. The Health League of Canada, initially known as the Canadian National Council for Combatting Venereal Disease and then the Canadian Social Hygiene Council, was started in 1919 by physician Gordon Bates, as an anti–venereal disease organization, with a strong emphasis on sex education. The organization believed that sex education needed to be based on high moral standards: it promoted continence before marriage and condemned the sexual double standard that allowed men leeway in sexual adventures while blaming women for any violation of chastity. Although the Health League promoted a wide range of initiatives over the years, including childhood immunization, milk pasteurization, industrial health and water fluoridation, we will focus our attention here on the issue that birthed the organization and was its key interest throughout its history: sex education.

During the First World War, Canadians realized that the country had a substantial problem with sexually transmitted infections or, as they were then known, venereal diseases. By 1915, 28.7% of the men in the Canadian Expeditionary Force were infected.1 And yet, there was also hope. Not long before the war, new treatments had emerged: these arsenic-based treatments were toxic and arduous, but they could cure.

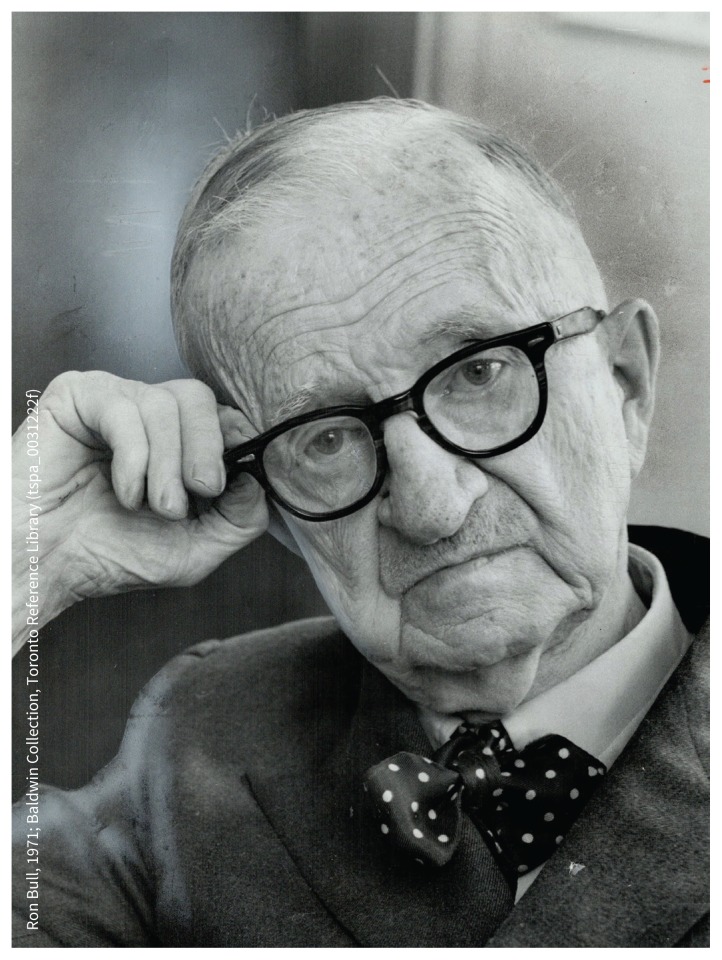

Dr. Gordon Bates. Permission to use the image was granted by The Toronto Star.

Image courtesy of Ron Bull, 1971; Baldwin Collection, Toronto Reference Library (tspa_0031222f)

Also, in this post-Victorian era, some of the stigma associated with venereal disease was declining. Groups such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and public health organizations urged Canadians to talk openly about venereal disease in the hopes of improving moral standards.2 During the war, Captain Gordon Bates, a young physician, became the Secretary of the Advisory Committee on Venereal Disease in Military District No. 2. His committee of volunteers, including doctors, lawyers, newspaper editors, the heads of women’s organizations and clergy, organized education on venereal disease for churches and schools, created women’s patrols to police the streets of the city and established a recreation committee for soldiers to keep them out of trouble.3

After the war, Bates lobbied to keep the work going. When the federal Ministry of Health was created in 1919, it had a venereal disease division, the main purpose of which was to provide matching funding to provinces that agreed to establish free venereal disease clinics. The division also provided a yearly grant to the Canadian National Council for Combatting Venereal Disease, to deliver education about venereal disease across the country.4

As head of the council, Bates arranged for the British suffrage leader Emmeline Pankhurst to give lectures across the country about venereal disease. As many historians have detailed, the interwar period marked a high point of eugenic concerns in Canada — Alberta passed a sexual sterilization act in 1928 to prevent the “unfit” from reproducing, while other Canadians promoted “positive” eugenics, urging Canadians to improve their health through maternal health education, better nutrition and exercise. There was particular concern about syphilis, because it could be passed from mother to child. Pankhurst warned of dire consequences for the white race if venereal disease was to continue to spread. The council showed The End of the Road (1919) to half a million Canadians. The silent film featured 2 girls: Mary and Vera. Mary’s mother teaches her about reproduction and she becomes a nurse, who refuses her boyfriend’s advances when he enlists. Vera’s mother tells her nothing and Vera becomes the mistress of a wealthy man and contracts syphilis.5

The council sponsored social hygiene exhibits across the country, including short films on reproduction, educational pamphlets and wax models portraying the ravages of syphilis. The council urged people to be tested and treated for venereal disease, and it promoted healthy recreation for young people. By urging parents to talk about sex with their children and criticizing the sexual double standard, the council saw itself as an open-minded and progressive organization.

Interest in venereal disease waned by the end of the 1920s. By the early 1930s, routine testing was showing substantial decreases in the incidence of disease.6 The Canadian Social Hygiene Council broadened into childhood immunization and milk pasteurization. It started a magazine, Health, and operated a very successful series of radio talks. When the Second World War broke out, the Health League jumped into action, fearing the war would once again lead to an increase in venereal disease. The League showed the American film, No Greater Sin (1941), featuring a young couple who are successfully treated for syphilis, to half a million Canadians. Although some people involved in venereal disease education thought that it would be better to focus on testing and treatment, the League strongly believed that moral education in chastity was necessary, and it continued to circulate the materials it had developed in the 1920s. Partly as a result, provincial governments began developing their own programs of venereal disease education and pushing the League out of the national conversation about the topic.

In the 1970s, when concern about venereal disease reawakened in the midst of rapidly changing sexual mores, Bates believed that young people needed to be re-educated in morality, using the same materials and standards that he had used in the 1920s, including The End of the Road.7 In Health, he reprinted an editorial originally published in the Toronto Globe at the end of the First World War. Titled “She might have been your daughter,” the article told of the tragic marriage of a pure young woman who was infected with venereal disease by her husband, and whose children were born with syphilis.8 Not only was the piece out of date in terms of the likely consequences of venereal disease in the age of antibiotics, but the rhetoric of female purity and the idea that women’s happiness came from their maternal duties made the piece seem desperately out of touch in the era of second-wave feminism.

Over the years, the Health League had many successes: its magazine, Health, was a staple in many medical offices and it ran very successful educational campaigns, in the form of National Immunization Week and National Health Week. But the organization was unable to renew itself or adjust to changing sexual values and norms. The dynamic doctor who had founded the organization remained at its head until his death. By the 1960s, the Health League’s funders, most notably the United Way, had abandoned the organization, and the once large and influential board of directors had shrivelled. The Health League did much to promote health in Canada in the middle decades of the 20th century, but the organization’s focus on improving the morality of Canadians ultimately led to its downfall.9

Footnotes

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/180773-medsoc

Competing interests: Catherine Carstairs, Bethany Philpott and Sara Wilmshurst report receiving grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, during the conduct of the study.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Funding: Government of Canada, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, No. 410-2006-0074.

References

- 1.Cassel J. The secret plague: venereal disease in Canada, 1838–1939. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1987:122–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sethna CL. The facts of life: the sex instruction of Ontario public school children, 1900–1950 [thesis]. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1995:80–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates G. The venereal disease problem. The Public Health Journal 1918;9:354–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Memorandum concerning the Canadian Social Hygiene Council. LAC, MG28, I332, vol. 34, file 4.

- 5.End of the Road. University of Michigan Historical Health Films Collection; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parney FS. Social aspects of the venereal disease problem in Canada. Canadian Public Health Journal 1933;24:316–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minutes, Action Committee Meeting, 1971 Nov. 23, LAC, MG28, I332, vol. 135, file 2;1–3.

- 8.Bates G. She might have been your daughter. Health 1972; Summer:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carstairs C, Philpott B, Wilmshurst S. Be wise! Be healthy!: morality and citizenship in Canadian public health Campaigns. Vancouver: UBC Press; 2018:192–7. [Google Scholar]