Abstract

The knowledge of individual response to a therapy, which can be assesed by in vitro screening, is essential for the development of therapeutics. Chaperone therapy is based on the ability of small molecules to fold the mutant protein to recover its function. As a novel approach for the treatment of Gaucher disease (GD), ambroxol was recently identified as a chaperone for GD, caused by the pathogenic variants in GBA gene, resulting in lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase (GCase) deficiency. Since ambroxol activity is mutation-dependent, the assessment of the chaperone action requires adaptation of a cell model with genetic format identical to the patient. We compared the chaperone activity of ambroxol using different primary cells derived from GD patients with different GBA genotypes. Ambroxol enhanced GCase activity in cells with wild type GBA and in those, compound heterozygous for N370S, but was ineffective in cell lines with complex GBA alleles. In cells from patients with neuropathic GD and L444P/L444P genotype, the response to ambroxol was varied. We conclude that chaperone activity depends on diverse factors in addition to a particular GBA genotype. We showed that PBMCs and macrophages are the most relevant cell-based methods to screen the efficacy of ambroxol therapy. For pediatric patients, a non-invasive source of primary cells, urine derived kidney epithelial cells, have a vast potential for drug screening in GD. These findings demonstrate the importance of personalized screening to evaluate efficacy of chaperone therapy, especially in patients with neuronopathic GD.

Keywords: Ambroxol, Gaucher disease, chaperone therapy, drug screening, neuronopathic

Introduction

Personalized medicine started with the knowledge that each individual has a unique genetic background [1]. In some patients, certain drugs do not work as expected; in others, treatment can have toxic effects [2-4]. Therefore, it is desirable to test drug efficacy using in vitro cell-based screening assays before prescription of therapy. The key to a successful screening is the adaptation of native cell systems with physiological and genetic format relevant to the patient. Application of stem cell-derived cellular models is expected to improve our ability to speed up the development of novel therapies. Preparation of stem cells from each individual patient however is not only costly but also requires specific expertise. Primary cells can be an ideal source for drug screening for a particular disease, especially for genetic disorders.

Gaucher disease (GD) (OMIM 23080, 231000, 231005), the most common lysosomal storage disorder (LSD), is caused by mutations in GBA gene (OMIM 606463), resulting in the deficiency of lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase (GCase) (EC 3.2.1.45). The clinical Gaucher disease is divided into distinct clinical types whether the Central Nervous System (CNS) is involved. The spectrum for neuronopathic GD ranges from a perinatal lethal form (type 2 GD or acute neuronopathic, GD2) to a slowly progressive neurological disorder (type 3 Gaucher disease, GD3). In non neuronopathic or type 1 Gaucher disease, GD1), there is primary systemic involvement with organomegaly and skeletal disease, or some patients with GD1 occasionally remain asymptomatic.

The GBA mutations lead to misfolding of GCase during the translation process in the endoplasmic reticulum, and altered protein trafficking to the lysosome [5]. The deficiency of GCase in the lysosome results in chronic accumulation of the substrate glucosylceramide virtually in all cell lineages However, the involvement of macrophages and their precursors, monocytes result in Gaucher cells, the pathologic hallmark for GD. The current standard of care, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) administrated intravenously successfully treats the systemic manifestation, however is less effective during the advanced stages of disease when the complications ensue. In developing countries, ERT as a treatment modality, is still problematic due to its high cost and limitations with production, distribution, and storage. Another FDA approved therapy for GD is substrate reduction therapy (SRT), and both miglustat and eliglustat act on ceramide synthesis pathway by decreasing the production of the substrate. None of the above therapies are effective for the treatment of neuropathic form of GD. The future of GD therapy may lie in small molecules acting as agents for enzyme-enhancement therapy (EET). EET is based on the ability of small molecules, or chaperones, to fold the misfolded mutant enzyme. This approach has the potential to cross the CNS and carries the potential to treat the neurological symptoms of GD.

Chaperones show mutation-dependent biochemical chaperoning profiles. It is well studied that different GBA mutations have different effects on protein folding, trafficking, and functional activity [6,7]. The GCase is extremely prone to bind to site-specific chaperones and propagate enzyme activity in a pH-dependent manner. In 2009, ambroxol was identified as a chaperone for GCase [7,8]. Ambroxol hydrochloride (C13H19Br2ClN2O) is an anti-inflammatory and a Na+ channel blocker. It was developed for treatment of airway mucus-hypersecretion and hyaline membrane disease in newborns. Ambroxol has unique chaperone characteristics: it works best at both the pH of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and lysosomal environment. At pH 4.3, near lysosomal pH, ambroxol does not inhibit the enzyme but instead becomes an activator of GCase. The 3-D docking model predicts that ambroxol interacts with GCase through hydrogen binding, hydrophobic and π-π interactions [7]. Ambroxol interacts with active and non-active sites of the enzyme, by explaining the mixed type of activation/inhibition and pH-dependent activity [7]. However, ambroxol does not have a uniform chaperoning profile for all GBA mutations such as L444P [7]. Given that each patient has a unique genetic background, we need a personalized approach to assess the efficacy of chaperones utilizing in vitro cell models to achieve therapeutic success for each patient [9,10].

Patients and methods

Materials

Ambroxol hydrochloride (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), human anti-glucocerebrosidase (GBA) antibodies (N-terminal # G4046, C-terminal #G4171, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), LAMP1 and LC3A/B antibodies (Cell signaling technology, Danvers, MA, USA), NuPAGE SDS running buffer, bolt 8% Bis-Tris Plus gel, Novex ECL chemiluminescent substrate reagents, sample reducing agents, supeScript VILO master mix, qubit RNA assay kit, powerUP SYBR green master mix, media 106, low serum growth supplement kit, BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), sodium taurocholate hydrate, 4-Methylumbelliferyl β-D-glucopyranoside (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), normocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA).

Patients

The patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The diagnosis of GD was confirmed by enzymatic activity and molecular analysis. All patients have given a written informed consent for the collection of samples and analysis of the data. The clinical protocol was approved by the ethics committees and data protection agencies at all participating sites, protocol # 13-CFCT-07, WIBR protocol #20131424.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patient-derived primary cells

| Patients | Gender | Age | Ethnicity | GBA genotype | GD type | GCase residual activity | Ambroxol treatment | |

|

| ||||||||

| Enzyme activity (%) | Protein | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | M | 8 | Asian | L444P/L444P | GD3 | 3.5% | No | No |

| 2 | M | 15 | Caucasian | L444P/L444P | GD3 | 4.2% | 211±3.2% | Increased |

| 551%*±26% | ||||||||

| 3 | M | 8 | Caucasian | L444P/L444P | GD3 | 3.8% | 212±3.2% | ND |

| 4 | F | 4 | Hispanic | L444P/L444P | GD3 | 5.1% | No* | ND |

| D409H/A549P | ||||||||

| 5 | F | 22 | Hispanic | L444P/L444P | GD3 | 7.4% | 119±3.5% | ND |

| 216±26# | ||||||||

| 6 | M | 21 | Hispanic | L444P/L444P | GD3 | 2.4% | No | ND |

| No# | ||||||||

| 7 | F | 12 | Hispanic | L444P/L444P | GD3 | 6.3% | No | ND |

| 158±24# | ||||||||

| 8 | M | 50 | Ashkenazi | L444P/N370S | GD1 | 26% | 222±14% | ND |

| 9 | F | 61 | Caucasian | L444P/N370S | GD1 | 6.8% | 176±4.4% | ND |

| 304±10%# | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Carrier | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | F | 55 | Caucasian | WT/N370S | 58% | No | ND | |

| 2 | M | 8 | Ashkenazi | WT/N370S or L444P | Normal | 132±3% | Increased | |

| UKEC cells | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Control | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | F | 49 | Caucasian | WT/WT | Normal | 191±5.6% | ND | |

| 122±2.5%& | ||||||||

| 2 | F | 26 | Caucasian | WT/WT | Normal | 144±9.8% | ND | |

| 3 | M | 25 | Asian | WT/WT | Normal | 153±3.3% | ND | |

No: does not show a statistically significant increase in response to 100 µM Ambroxol. ND: no data.

Data from fibroblasts and PBMC.

Data from PBMC and macrophages.

Data from fibroblasts and macrophages.

Isolation and growth of primary skin fibroblasts

Tissue samples were obtained from 4 patients (1 female and 3 male, age 3-15 years) (Table 1). Skin biopsies were placed into 50 ml conical tube and washed in PBS with 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Skin fibroblasts were cultured as per standard methodology in 24 well plates with complete media 106 (media 106, low serum growth supplement kit and normocin, ATCC, USA). After first passages, fibroblast cells were grown in complete media 106 until confluent stage and sub-cultured at a split ratio 1:4 for young cultures. Cultures were terminated before passage 10 or when the fibroblasts were unable to reach confluence after two weeks.

Isolation, purification and growth of urine-derived kidney cells

Fresh 25-50 ml of mid-stream urine samples were collected from a male patient with GD and a healthy control. The samples were processed immediately by transferring to sterile 50 ml conical tubes and then centrifuging at 400×g for 10 min. After the supernatant was removed, the pellets were washed three times with PBS containing 1% ampicillin/streptomycin and centrifuged again at 400×g for 10 min. Cells were then plated in a 24-well dish with renal epithelial cell basal media supplemented with renal epithelial cell growth kit (ATCC) and normocin (InvivoGen). While most cells from urine failed to attach; kidney epithelial cells attached to plate surfaces. The culture media was changed every 2-3 days until a single or few cells formed colonies. The urine kidney epithelial cells were split using 0.05% trypsin when culture cells reached formation of large colonies. After first passages, kidney epithelial cells were continuously grown in complete renal epithelial cell basal media and sub-cultured at a split ratio of 1:2 for young cultures. Maximum passage number was 6-8 passages, or until kidney epithelial cells were unable to reach confluence and started to undergo apoptosis.

Isolation, purification and culture of peripheral blood monocytes (PBMC)

PBMC were purified from blood samples from patients with GD using Lymphoprep™ reagent and SepMate™ tubes (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Lymphoprep™ was added to the lower compartment of the SepMate tube. Blood was mixed with PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a 1:1 ratio, and then layered on top of Lymphoprep™ following manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were centrifuged at 800×g for 20 min at 18°C with the brake off. The upper plasma layer was discarded. The PBMC layer was removed carefully, washed three times with PBS and centrifuged at 300×g for 8 min at room temperature between each wash. Isolated PBMC were incubated in 5% CO2 in phenol red-free RPMI media with 10% FBS.

Differentiation of M2-macrophages from PBMC

Freshly isolated PBMC had been used for macrophage differentiation. PBMC (10 million in 1 ml) were resuspended in an appropriate amount of monocyte attachment medium (2 ml per well in 6 well plate) then incubated for 2 h in 5% CO2 cell culture incubator to let monocytes attach to the surface. After aspiration of the media along with floating cells, a complete M2-macrophage generation media was added. M2 differentiation media contained: RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% normocin, 2 mM glutamine, 1% Na-pyruvate, 1% non-essential amino acids (NEEA) and 50 ng/ml human recombinant M-CSF (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). After 6 days 100% by volume of fresh complete M2 macrophage differentiation media was added, and 2 days later media was completely replaced with fresh media. On day 10 macrophages were treated with ambroxol at indicated intervals and concentrations.

Protein isolation and Western blot analysis

Whole-cell extracts (WCE) were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). 30-40 μg of WCE were separated on mini protein TGX stain free gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and electroblotted using the Trans-Blot® Turbo™ midi PVDF transfer packs. The ChemiDoc™ MP imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to visualize and quantitate optical density (IOD) for each band. The IODs of bands of interest were normalized to the loading control, beta-actin, and the normalized value of the controls were set to 1 for comparison between separate experiments.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time-PCR (qPCR)

RNA was extracted from patient and control PBMCs using the RNeasy mini kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA). The superScript®VILO™ cDNA synthesis kit was used to reverse-transcribe RNA using random hexamers primers. Samples were prepared using PowerUp™ SYBR® master mix. Individual samples were run in triplicate. mRNA transcript levels were compared to loading control, GADPH were measured using StepOnePlus™ Real-time PCR System (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). The primers were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA) (Supplementary Table 1). Analyses and fold differences were determined using the comparative CT method. Fold change was calculated from the ΔΔCT values with the formula 2-ΔΔCT relative to mRNA expression in untreated control.

Measurement of GCase activity

The assay to measure GCase enzymatic activity in cells was carried out as described [11,12], using 4-methylumbelliferyl b-D-glucopyranoside as the artificial substrate. Released 4-methylumbelliferone was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (excitation 360 nm and emission 460 nm). Briefly, for preparation of lysates, the frozen cells were lysed in cold H2O. Protein concentrations were determined with BCA assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, Il, USA). The reaction was started by addition of 5 or 10 μg of protein into substrates solution in 0.1 M citrated buffer, pH 5.2, supplemented with sodium taurocholate (0.8% w/v). The reaction was terminated by adding 0.4 ml of 0.2 M glycine sodium hydroxide buffer (pH 10.7).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test with 2-tailed distribution and 2-sample equal variance or 1-way ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Chaperone activity of ambroxol in patient derived fibroblasts

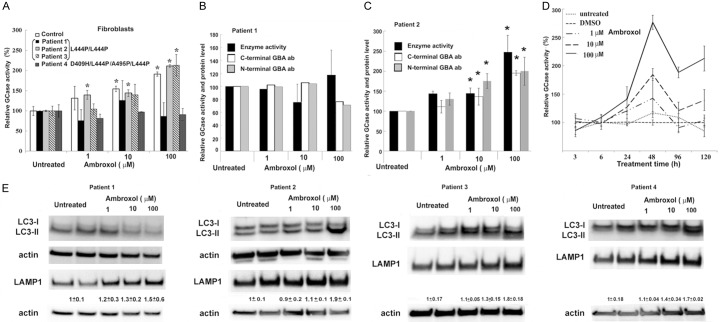

Dermal fibroblasts are an established research model for GD. Fibroblasts appear 7-10 days after the biopsy and get established in 4-8 weeks before screening. The most common GBA mutation leading to GD3 is L444P/L444P. However, it is not clear whether ambroxol is able to fold this mutated enzyme in fibroblasts derived from GD3 patients with L444P/L444P and with 3-6% of residual GCase activity. GCase activity was measured and compared to controls after treating the cells with ambroxol. GCase activity was increased in control fibroblasts (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 1A) suggesting ambroxol’s ability to accelerate folding and trafficking of wild type GCase from endoplasmic reticulum to lysosomes [7,13]. Consistent with a dose response effect, in two patient cell lines, there was an increase in GCase activity (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 1A), however fibroblasts from patient 1 showed no increase in GCase activity following ambroxol treatment (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 1A). Ambroxol did not lead to a change in enzymatic activity in D409H/L444P fibroblasts (patient 4). Fibroblasts from patient 1 similarly showed no change in protein or mRNA levels (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 1B, 1C). In fibroblasts from patient 2, there was an increase in GBA protein, but not mRNA levels (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure 1D, 1E). These findings demonstrate that not all GCase mutants respond to ambroxol similarly, and especially the genotype L444P/L444P exhibit varied responses. To determine the optimal time to enhance mutated GCase, fibroblasts (patient 3) were treated with ambroxol at intervals of 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, 4, and 5 days. GCase activity increased after 24 h, with a maximum peak at 48 h (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Ambroxol chaperone activity in fibroblasts from GD patients with L444P/L444P and D409H/L444P/L444P/A549P genotypes. A. Fibroblasts were cultured for 5 days in presence of increasing concentrations of ambroxol. GCase enzyme activity was estimated as relative levels towards to untreated control. Each bar represents the average ± stdev. P < 0.05 vs. untreated control; Student’s t test. B. Fibroblasts derived from patient 1 show no enhancement of GCase activity or protein level in response to ambroxol treatment. Fibroblasts were treated for 5 days in the presence of ambroxol. Whole cell extracts (30 mg) were prepared and immunoblotted using anti-GBA antibodies. Results represent enzyme activity level (black bar), immunoblotting with C-terminal (white bar) and N-terminal (gray bar) anti-GBA antibodies. Quantification of relative levels of GBA normalized to actin from separate experiments in which control were untreated fibroblasts. Untreated control set as 100%. C. Fibroblasts derived from patient 2 show enhancement of GCase activity in response to ambroxol treatment. Values are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. untreated control; Student’s t test. D. Ambroxol induced GCase activity in time- and concentration-dependent manner, as determined by enzyme activity assay. GD3 fibroblasts were derived from patient 2. Each bar represents the average ± stdev vs. untreated control; Student’s t test. E. Following ambroxol treatment, representative Western blot showing LC3-I/LC3-II and LAMP1 protein expression level in fibroblasts derived from patient 1, 2, 3 and 4. Quantification of relative level of LAMP1/actin from 3 different experiments.

GCase deficiency is associated with alterations in autophagy-lysosomal function. Recent reports indicate that ambroxol may have dual action: chaperone activity and restoration of lysosomal dynamics for the proper functioning of GCase [13-15]. To examine the effects of ambroxol on autophagy-lysosomal pathway, the autophagy marker LC3I/II and lysosome marker LAMP1 were used. Western blot analysis demonstrated an increase in the level of LC3-II with ambroxol treatment in all fibroblasts except for patient 1 that also didn’t have a change in GCase activity (Figure 1E). For LAMP1, fibroblasts from all patients demonstrated increased levels after ambroxol treatment (Figure 1E). In summary, ambroxol enhanced GCase activity and improved autophagy-lysosomal dynamics in fibroblasts derived from GD 3 patients. Moreover, these results clearly suggest that the prediction of ambroxol chaperone activity cannot be done alone based on the type of GCase mutation.

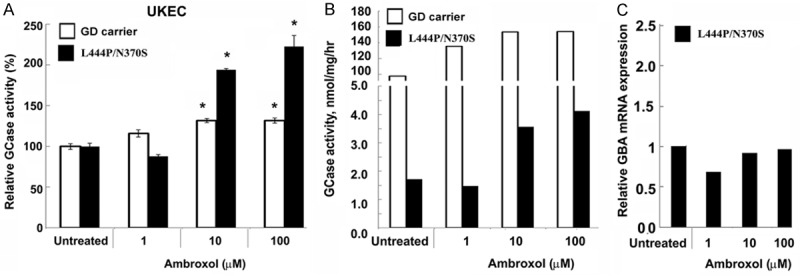

Monitoring chaperone response in urine kidney epithelial cells (UKEC)

We investigated whether a non-invasive source of primary cells from patients could serve as a cell model for chaperone screening, the effect of ambroxol on the GCase activity in urine derived kidney epithleial cells (UKEC) was studied. UKEC derived from an asymptomatic GD carrier and a patient with GD and L444P/N370S mutation were treated with ambroxol. GCase activity increased in UKEC lines in a concentration-dependent manner, similar to that observed in fibroblasts (Figure 2). mRNA analysis was concurrent with that of the fibroblast, and showed that ambroxol-treated kidney cells did not have increased mRNA level, (Figure 2C). Thus, UKEC are a suitable model for testing efficacy of enzyme enhancement therapy with pharmacological chaperones.

Figure 2.

Ambroxol increases GCase activity in urine kidney epithelial cells. (A, B) GCase activity in UKEC cells derived from a healthy control (white bar) and a GD patient with genotype L444P/N370S (black bar) cultured for 5 days in presence of increasing concentrations of ambroxol. The data are expressed as % GCase activity compared to respective untreated cells (A) and as GCase concentration nmol/hr/mg protein (B). Each bar represents the average ± sem. *P < 0.05 compared with an untreated group. (C) Q-PCR was performed to determine relative GBA mRNA expression levels after 5 days ambroxol treatment.

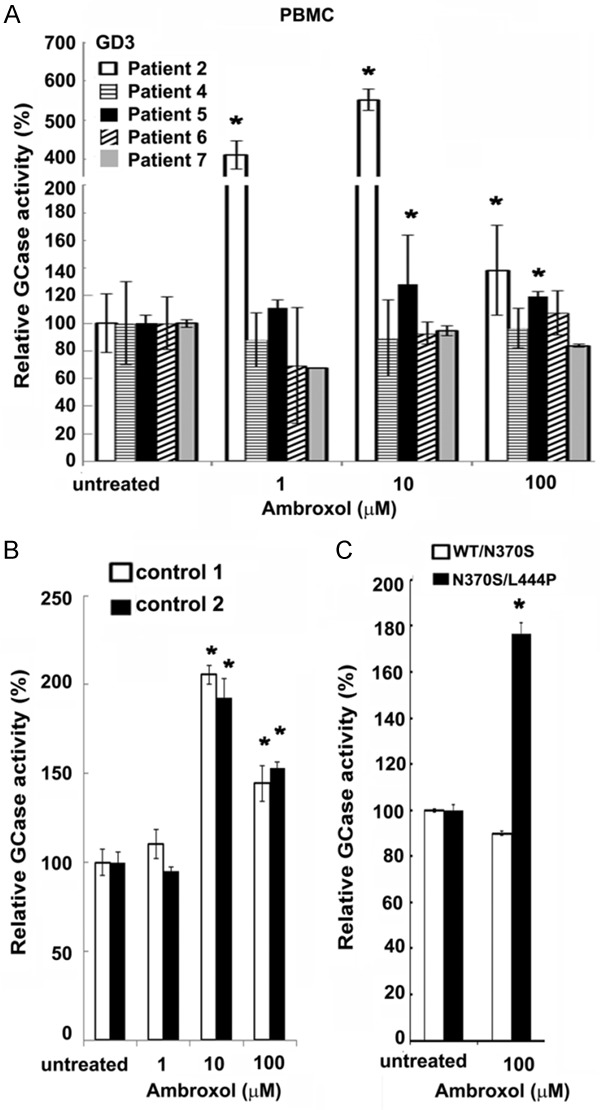

An express-screening model for GD peripheral blood mononuclear cells

An expedited screening for ambroxol chaperoning efficiency could be done in 5 days using PBMC. Screening of PBMCs from five patients with either L444P/L444P or D409H/L444P/A495P/L444P genotyeps demonstrated that cells from different patients responded differently to ambroxol (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 2A). PBMCs from patient 2 with the lowest GCase activity showed the best chaperoning response (Figure 3A), consistent with ambroxol induced increase in GCase activity in fibroblasts. D409H/L444P/A495P/L444P PBMCs showed no increase in GCase activity in the presence of ambroxol, also similar to the fibroblasts. In samples 5, 6, and 7 derived from siblings carrying L444P/L444P mutation, only PBMCs from patient 5 showed an increase in GCase activity with ambroxol. (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 2A). Ambroxol elevated GCase activity in control PBMCs (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure 2B). The chaperoning efficiency of ambroxol was assessed in a GD carrier (WT/N370S) and the GD patient with N370S/L444Pgenotype and Parkinsonism, PBMCs were treated with ambroxol. Ambroxol increased enzyme activity in PBMCs from the patient with GD, but not from the Gaucher carrier (Figure 3C). These results supports that individual screening is essential to predict the efficacy of ambroxol. In contrast to the fibroblast data, the highest concentration (100 μM) of ambroxol showed inhibition of GCase activity in PBMCs.

Figure 3.

Ambroxol chaperone activity in PBMCs. A. PBMCs derived from GD patients with L444P/L444P genotype, were cultured for 5 days in the presence of increasing concentrations of ambroxol. The data are expressed as % GCase activity compared to respective untreated cells. Each bar represents the average ± stdev. *P < 0.05 Student’s t-test compared with an untreated group. B. Ambroxol induced GCase activity in control PBMC as determined by enzyme activity assay. PBMCs derived from healthy donors were cultured for 5 days in the presence of ambroxol. The data are expressed as % GCase activity compared to respective untreated cells. Each bar represents the average ± stdev. *P < 0.05 Student’s t-test compared with an untreated group. C. PBMCs derived from a Gaucher carrier patient with WT/N370S genotype and a GD patient with N370S/L444P genotype were cultured for 5 days in presence of 100 mM of ambroxol. The data are expressed as % GCase activity compared to respective untreated cells ± stdev. *P < 0.05 Student’s t-test compared with an untreated group.

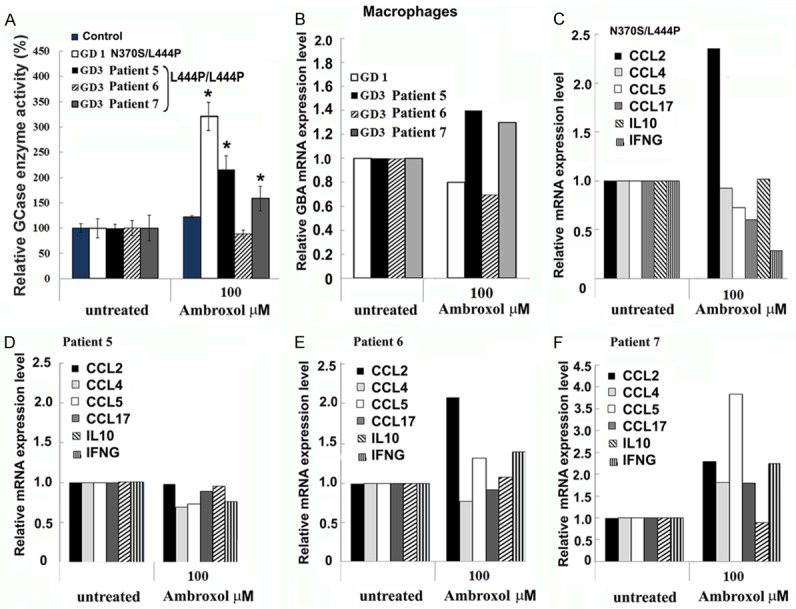

Patient-derived macrophages as a GD model for chaperone screening

In GD, macrophages, with distinct subpopulations such as M2, are suggested to be the primary disease effectors [16,17]. M2 macrophages were differentiated from PBMCs isolated from a control, a GD1 patient with N370S/L444P, and GD3 patients with L444P/L444P genotypes (Figure 4). Macrophages, along with PBMCs, derived from GD1 patient showed ambroxol chaperoning activity (Figure 4A). Consistent with the previous data, in patients with the L444P/L444P, the response to ambroxol treatment varied. Macrophages and PBMC derived from patient 5 showed increasing GCase activity in the presence of ambroxol (Figure 4A). Surprisingly, ambroxol led to an enhanced GCase activity in macrophages from patient 7, but no effect was observed in PBMCs (gray color bar, Figures 3 and 4). Despite an increase in the GCase activity level, the mRNA expression level did not change with ambroxol (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Macrophages as a GD model for screening chaperone activity. (A) Macrophages derived from a healthy donor (control), GD patients with L444P/N370S, and L444P/L444P genotypes, were differentiated from PBMCs and treated for 5 days in the presence of 100 mM ambroxol. The data are expressed as % GCase activity compared to respective untreated cells ± stdev. *P < 0.05 Student’s t-test compared with an untreated group. (B) Ambroxol treatment did not change GCase mRNA levels in macrophages. Q-PCR was performed to determine relative GBA mRNA expression levels from macrophages derived from GD patients with L444P/N370S and L444P/L444P genotypes. Macrophages were differentiated from PBMC and treated for 5 days in the presence of 100 mM of Ambroxol. (C-F) Q-RT-PCR was performed to determine mRNA expression levels of CCL2, CCL4, CCL5, CCL17, IL10 and IFNG in macrophages derived from GD1 patient (C), GD3 patients with chaperoning activity to ambroxol (C-E), and GD3 patient not responded to ambroxol (E).

Substrate accumulation is suggested to trigger macrophage activation, enhanced expression of immune response genes, and transformation of monocytes into macrophages [16]. For that reason, we studied the effect of ambroxol on expression of cytokines, interferon gamma (IFNG), and interleukin 10 (IL10). An increased CCL2 mRNA level was observed after ambroxol treatment in GD1 and GD3 macrophages (Figure 4). CCL4 and CCL5 levels did not change, except for an increase in CCL5 levels in macrophages from patient 7 (Figure 4F). A decrease in the expression of IFNG and CCL7 occurred only in N370S/L444P macrophages after ambroxol treatment, but not in L444P/L444P macrophages (Figure 4). Altogether, data demonstrate that ambroxol also changes the expression profile of genes involved in immune pathways in macrophages.

Discussion

Enzyme enhancement or chaperone therapy is a promising approach for the treatment of GD, especially when the CNS is involved. Recently, an open-label pilot study with ambroxol showed promising results in patients with neuronopathic GD with N188S, G193W, F213I/RecNciI and D409H/IVS10-1G>A genotypes [10]. Ambroxol demonstrated good tolerability while enhancing GCase activity and improving neurological manifestations. In this study, we focused on screening cell lines from GD3 patients with L444P/L444P and compared them with the cell lines harboring H409/L444P/A549P/L444P and N370S/L444P mutations as in a given population of patients with the subacute neurological form of Gaucher disease (GD3), the homozygosity for L444P is the most common. However, it is not clear whether ambroxol is able to fold GCase mutant L444P/L444P. In previous studies, fibroblasts with L444P/L444P mutation demonstrated neither increased protein levels nor enzymatic activity upon ambroxol exposure [6,7]. While ambroxol increased GCase activity, protein and RNA levels in L444P/L444P fibroblasts in another study [13]. As such, we investigated ambroxol chaperoning activity in primary fibroblasts derived from patients with the genotype L444P/L444P, and with 3-6% range of residual GCase activity. Ambroxol showed time and concentration-dependent chaperoning activity in control fibroblast, however not all L444P/L444P fibroblast lines responded positively to ambroxol. This result, together with the contradicting previously published data, suggests that the chaperone activity of ambroxol could be modified by diverse factors and not only by the individual’s genetic variants. Therefore, we highlight the importance of individualized screening for choosing chaperone therapy using ambroxol for patients with GD. It is well-known that the ER-folding system is complex and plays a central role on folding of misfolded mutant proteins. GCase as a lysosomal enzyme go through quality control and several protein modifications before shuttle to Golgi apparatus. Following further modification, GCase is trafficking to the lysosomes [18]. Mutant GCase enzymes are recognized as misfolded proteins and undergo through excessive degradation instead of trafficking to lysosome especially the L444P mutant of GCase [19]. Different mutations of GCase demonstrated varying degrees of degradation and demonstrated different level of residual enzyme activity. In GD1 cell lines with N370S/N370S, where residual GCase activity is 20% of normal, ambroxol was shown to significantly increase the enzymatic activity and protein levels [6,7]. Similarly, ambroxol increases GCase activity in fibroblasts harboring N188S/G193W, F213I/RecNciI, and D409S/IVS10-1G>A mutations [10]. In contrast, the genotype F2131/L444P having 5% residual GCase activity does not respond to ambroxol [6,10]. Additionally, ambroxol increases lysosomal integral mebrane protein-2 (LIMP-2) which mediates GCase trafficking to lysosomes and activate GCase endogenius activator saposin C [15,20]. During the process of translation and trafficking of GCase, ambroxol enhances the removal of L444P mutant protein from the endoplasmic reticulum, however this does not always lead to recovery of the enzyme activity [20]. Thus, the wide clinical spectrum observed in GD patients especially with L444P homozygotes cannot be explained only by the contribution of a genetic mutation [21]. The balance between lysosomal enzyme degradation, folding and trafficking is determined by the more than 75 proteins of the ER proteostasis network. As such, components of proteostasis network may play a vital role by re-arrangement ambroxol-mutant GCase forming interaction to other proteins during trafficking and maintaining enzyme activation. For example, inhibition of ERdj3-mediated mutant GCase with enhancing of calnexin-associated folding is able to rescue of lysosomal L444P GCase in fibroblast L444P cell line [22].

Dermal fibroblasts are the most common research model for LSDs, including GD. Initially, cultured fibroblasts were used to measure GCase activity to confirm GD diagnosis [7]. Later, cultured skin fibroblasts became the popular model to study molecular and biochemical aspects of GD, including the original screening of ambroxol as a GCase chaperone [7]. We were able to complete the ambroxol screening in two to three weeks, when fibroblasts demonstrated good proliferative rate with a low passage number. But, ambroxol concentration and time course treatments for screening in fibroblasts were not standardized and varied from one publication to another. The reported range for the optimal concentration of ambroxol, i.e., when ambroxol enhances the activity of the mutant GCase without toxic effects, has a wide range from 1 to 100 μM concentration. In fibroblasts, GCase has been reported to have half-life of approximately 60 h, so treatment duration for 5 days often has been used [7,10,13]. In this study, ambroxol exhibited time-dependent chaperoning profiles after 24 h treatment, and the maximum enzyme activity was observed at 48 h.

Obtaining tissue material from pediatric patients requires invasive procedure such as biopsy or phlebotomy. Moreover, access to a medical facility is required for this kind of sample collection. We have now established primary UKEC as a cell model for screening assays. Stably-transfected podocytes have been used previously to study molecular and the pharmacogenetics aspect of Fabry disease (FD), where kidney dysfunction is a frequent complication [23,24]. However, to our knowledge, kidney cells are not yet studied as a GD cell model. Kidney epithelial cells are regularly sloughed off the renal tubule into the urine [25], and can be collected from urine and selectively grown under conditions supporting proliferation of epithelial cells [26]. 25-100 ml of mid-stream urine can be collected and samples may be processed immediately or stored at +4°C for up to 24 h, allowing the transport of samples. UKEC cell colonies become visible 1-2 weeks, after which can be passaged. Cells stop dividing after 5-6 passages, providing a time frame of two to three weeks for ambroxol screening.

GD pathology involves macrophage lineage cells, including monocytes, and dendritic cells, T and B cells [16,27]. In macrophages, the accumulation of GCase substrate in the lysosomes leads to formation of ”Gaucher cells” [28]. Gaucher cells become intensely stimulated and release chemokines and cytokines, some of which are utilized as GD biomarkers. Moreover, Gaucher cells accumulate in various tissues, and are associated with the propagation of tumor associated macrophages [28]. Therefore, PBMCs and macrophages are the most relevant cell type to screen efficacy, toxicity, and inflammatory response in GD. Similar to the fibroblast and UKEC data, ambroxol demonstrated chaperone activity in PBMC and macrophages. However, cells derived from various patients with genotype L444P/L444P, including PBMCs and macrophages derived from three siblings with GD3 responded differently to the ambroxol treatment.

Synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) could affect messenger RNA splicing, stability, protein structure and protein folding [29-31]. Increasing evidence suggest that in future, SNPs analysis could help to predict individual’s response to treatment. Over 4000 SNPs of GBA genes have been reported, including 98 pathogenic SNPs, 34 likely benign, or uncertain significant SNPs, it is possible that variability in response to ambroxol treatment may be related to SNP.

Ambroxol is a drug with anti-inflammatory activity, and has been historically used for the treatment of acute and chronic bronchopulmonary diseases. It is known that patients with L444P/L444P genotype have a high risk for lung involvement [32]. Furthermore, Gaucher macrophages release proinflamatory cytokines such as CCL2, CCL5, IF gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, IL10 [16]. Elevated cytokine levels are associated with bone and pulmonary pathology of GD. Ambroxol was shown to decrease the secretion of IL-2, IF gamma, IL-1, and TNF-alfa in PBMCs stimulated with phytohemagglutinin or lipopolysaccharide [33]. In the present study, macrophages respond to ambroxol by changing expression profile of genes involved in immune pathways. Ambroxol stimulated the expression of CCL2, a chemokine which regulates migration and infiltration of monocytes/macrophages. Expression analysis of other immune pathway genes suggests, among patients with GD, there are differing responses. Altogether, our results show that macrophages respond to ambroxol by changing expression profile of immune genes, thus chaperone screening should also include immune activation studies, especially in patients with significant bone or pulmonary disease.

Summary

We evaluated chaperone therapy using ambroxol in different types of primary cells derived from patients with Gaucher disease. Ambroxol demonstrated a positive chaperone effect in primary cells with N370S/L444P genotype; however, in cells derived from patients with L444P/L444P mutation, there was not always a response to ambroxol. Patient-derived primary cells can be used to identify patients who are likely to respond to chaperone treatment. The individualized screening for ambroxol is an example how personalized medicine can improve the efficacy of certain medications while preventing the untoward effects.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Renuka Limgala for reviewing this manuscript.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Ni X, Zhang W, Huang RS. Pharmacogenomics discovery and implementation in genome-wide association studies era. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2013;5:1–9. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prakash S, Agrawal S. Significance of pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics research in current medical practice. Curr Drug Metab. 2016;17:862–876. doi: 10.2174/1389200217666160804150959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kingsley MJ, Abreu MT. A personalized approach to managing inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2016;12:308–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Severson TJ, Besur S, Bonkovsky HL. Genetic factors that affect nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic clinical review. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6742–6756. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i29.6742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butters TD. Gaucher disease. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:412–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luan Z, Li L, Higaki K, Nanba E, Suzuki Y, Ohno K. The chaperone activity and toxicity of ambroxol on Gaucher cells and normal mice. Brain Dev. 2013;35:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maegawa GH, Tropak MB, Buttner JD, Rigat BA, Fuller M, Pandit D, Tang L, Kornhaber GJ, Hamuro Y, Clarke JT, Mahuran DJ. Identification and characterization of ambroxol as an enzyme enhancement agent for Gaucher disease. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23502–23516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimran A, Altarescu G, Elstein D. Pilot study using ambroxol as a pharmacological chaperone in type 1 Gaucher disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2013;50:134–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haneef SA, Doss CG. Personalized pharmacoperones for lysosomal storage disorder: Approach for next-generation treatment. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2016;102:225–265. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narita A, Shirai K, Itamura S, Matsuda A, Ishihara A, Matsushita K, Fukuda C, Kubota N, Takayama R, Shigematsu H, Hayashi A, Kumada T, Yuge K, Watanabe Y, Kosugi S, Nishida H, Kimura Y, Endo Y, Higaki K, Nanba E, Nishimura Y, Tamasaki A, Togawa M, Saito Y, Maegaki Y, Ohno K, Suzuki Y. Ambroxol chaperone therapy for neuronopathic Gaucher disease: a pilot study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3:200–215. doi: 10.1002/acn3.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban DJ, Zheng W, Goker-Alpan O, Jadhav A, Lamarca ME, Inglese J, Sidransky E, Austin CP. Optimization and validation of two miniaturized glucocerebrosidase enzyme assays for high throughput screening. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2008;11:817–824. doi: 10.2174/138620708786734244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng W, Padia J, Urban DJ, Jadhav A, Goker-Alpan O, Simeonov A, Goldin E, Auld D, LaMarca ME, Inglese J, Austin CP, Sidransky E. Three classes of glucocerebrosidase inhibitors identified by quantitative high-throughput screening are chaperone leads for Gaucher disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13192–13197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705637104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNeill A, Magalhaes J, Shen C, Chau KY, Hughes D, Mehta A, Foltynie T, Cooper JM, Abramov AY, Gegg M, Schapira AH. Ambroxol improves lysosomal biochemistry in glucocerebrosidase mutation-linked Parkinson disease cells. Brain. 2014;137:1481–1495. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siebert M, Sidransky E, Westbroek W. Glucocerebrosidase is shaking up the synucleinopathies. Brain. 2014;137:1304–1322. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambrosi G, Ghezzi C, Zangaglia R, Levandis G, Pacchetti C, Blandini F. Ambroxol-induced rescue of defective glucocerebrosidase is associated with increased LIMP-2 and saposin C levels in GBA1 mutant Parkinson’s disease cells. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;82:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandey MK, Grabowski GA. Immunological cells and functions in Gaucher disease. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013;18:197–220. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.2013004503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boven LA, van Meurs M, Boot RG, Mehta A, Boon L, Aerts JM, Laman JD. Gaucher cells demonstrate a distinct macrophage phenotype and resemble alternatively activated macrophages. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:359–369. doi: 10.1309/BG5V-A8JR-DQH1-M7HN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maor G, Rencus-Lazar S, Filocamo M, Steller H, Segal D, Horowitz M. Unfolded protein response in Gaucher disease: from human to Drosophila. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:140. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bendikov-Bar I, Ron I, Filocamo M, Horowitz M. Characterization of the ERAD process of the L444P mutant glucocerebrosidase variant. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2011;46:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendikov-Bar I, Maor G, Filocamo M, Horowitz M. Ambroxol as a pharmacological chaperone for mutant glucocerebrosidase. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2013;50:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goker-Alpan O, Hruska KS, Orvisky E, Kishnani PS, Stubblefield BK, Schiffmann R, Sidransky E. Divergent phenotypes in Gaucher disease implicate the role of modifiers. J Med Genet. 2005;42:e37. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan YL, Genereux JC, Pankow S, Aerts JM, Yates JR 3rd, Kelly JW. ERdj3 is an endoplasmic reticulum degradation factor for mutant glucocerebrosidase variants linked to Gaucher’s disease. Chem Biol. 2014;21:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebau MC, Braun F, Hopker K, Weitbrecht C, Bartels V, Muller RU, Brodesser S, Saleem MA, Benzing T, Schermer B, Cybulla M, Kurschat CE. Dysregulated autophagy contributes to podocyte damage in Fabry’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prabakaran T, Nielsen R, Larsen JV, Sorensen SS, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Saleem MA, Petersen CM, Verroust PJ, Christensen EI. Receptormediated endocytosis of alpha-galactosidase A in human podocytes in Fabry disease. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajzenberg H, Slaats GG, Stokman MF, Arts HH, Logister I, Kroes HY, Renkema KY, van Haelst MM, Terhal PA, van Rooij IA, Keijzer-Veen MG, Knoers NV, Lilien MR, Jewett MA, Giles RH. Non-invasive sources of cells with primary cilia from pediatric and adult patients. Cilia. 2015;4:8. doi: 10.1186/s13630-015-0017-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou T, Benda C, Dunzinger S, Huang Y, Ho JC, Yang J, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zhuang Q, Li Y, Bao X, Tse HF, Grillari J, Grillari-Voglauer R, Pei D, Esteban MA. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from urine samples. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:2080–2089. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonder S, Limgala RP, Ivanova MM, Ioanou C, Plassmeyer M, Marti GE, Alpan O, Goker-Alpan O. Persistent immune alterations and comorbidities in splenectomized patients with Gaucher disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2016;59:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ivanova M, Limgala RP, Changsila E, Kamath R, Ioanou C, Goker-Alpan O. Gaucheromas: When macrophages promote tumor formation and dissemination. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2018;68:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao N, Han JG, Shyu CR, Korkin D. Determining effects of non-synonymous SNPs on protein-protein interactions using supervised and semi-supervised learning. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunt R, Sauna ZE, Ambudkar SV, Gottesman MM, Kimchi-Sarfaty C. Silent (synonymous) SNPs: should we care about them? Methods Mol Biol. 2009;578:23–39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-411-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simhadri VL, Hamasaki-Katagiri N, Lin BC, Hunt R, Jha S, Tseng SC, Wu A, Bentley AA, Zichel R, Lu Q, Zhu L, Freedberg DI, Monroe DM, Sauna ZE, Peters R, Komar AA, Kimchi-Sarfaty C. Single synonymous mutation in factor IX alters protein properties and underlies haemophilia B. J Med Genet. 2017;54:338–345. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santamaria F, Parenti G, Guidi G, Filocamo M, Strisciuglio P, Grillo G, Farina V, Sarnelli P, Rizzolo MG, Rotondo A, Andria G. Pulmonary manifestations of Gaucher disease: an increased risk for L444P homozygotes? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:985–989. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.9706057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beeh KM, Beier J, Esperester A, Paul LD. Antiinflammatory properties of ambroxol. Eur J Med Res. 2008;13:557–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.