Abstract

Background

Increasingly, women have sought alternatives to traditional options (lubricants, estrogen products, and hormone replacement therapy) for unwelcome vaginal changes of menopause.

Objectives

This study evaluated whether a series of three monthly fractional CO2 laser treatments significantly improves and maintains vaginal health indices of elasticity, fluid volume, pH level, epithelial integrity, and moisture. Self-reported symptoms of vaginal atrophy were also measured. Biopsy samples after a series of three treatments were evaluated for histological changes to vaginal canal tissue.

Methods

Forty postmenopausal women were treated extravaginally and internally with a fractional CO2 laser. Objective measurements of vaginal health index, as well as subjective measurements of symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), urinary incontinence, and sexual function were reported at baseline. Follow-up evaluations were at one, three, six, and 12 months after the third treatment.

Results

Vaginal health index improved significantly after the first treatment and was maintained with mean improvement of 9.6 ± 3.3 (P < 0.001) and 9.5 ± 3.3 (P < 0.001) at the 6- and 12-month follow ups, respectively. Vaginal symptoms of dryness, itching, and dyspareunia improved significantly (P < 0.05) at all evaluations. Histological findings showed increased collagen and elastin staining, as well as a thicker epithelium with an increased number of cell layers and a better degree of surface maturation.

Conclusions

Fractional CO2 laser treatments were well tolerated and were associated with improvement in vaginal health and amelioration of symptoms of VVA. Histological changes in the epithelium and lamina propria, caused by fractional CO2 laser treatments, correlated with clinical restoration of vaginal hydration and pH to premenopausal levels.

Level of Evidence: 4

The past five years have witnessed a surge of interest in female wellness and specifically, vaginal rejuvenation, both surgical and nonsurgical. The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS) procedural statistics report an increase of 23% in surgical labiaplasty procedures performed in 2016 by plastic surgeons in the United States, compared to 2015 (the first year for which statistics were available).1 It is estimated that 35% of plastic surgeons now offer surgical labiaplasty and performed over 10,000 procedures last year.1 Along with this newer area of surgical interest, there has also developed a rapid growth in the number of treatment options for nonsurgical vulvovaginal rejuvenation. For both cosmetic and functional reasons, increasing numbers of women have sought alternatives to traditional options (vaginal lubricants, topical or oral estrogen products, and hormone replacement therapy) for dealing with unwelcome vaginal changes of menopause and childbirth, by choosing among a host of energy-based treatment devices that have emerged. These devices use technologies similar to those employed to rejuvenate skin of the face and body2-5 and include fractional CO2 or erbium:YAG (Er:YAG) laser-based technology, as well as radiofrequency (RF) treatment, to address the most common complaints of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) or vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA).6-12

GSM or VVA represents a constellation of symptoms13 that, while underreported, has been estimated to affect up to 50% of postmenopausal women14 and affect quality of life (QoL),15,16 as a result of the natural decrease of estrogen levels after the onset of menopause. Prior to menopause with normal circulating levels of endogenous estrogen, vaginal canal physiology is characterized by the presence of a thickened, rugated, nonkeratinized epithelial layer that is well vascularized and self-lubricated. As estrogen levels decline (or are deprived as in some patients with hormonally treated malignancies or following hysterectomy), the vaginal wall becomes thinner, there is a reduction in blood flow, and there is a changed quality and quantity of vaginal secretions, as well as loss of collagen and elasticity. The epithelial surface becomes pale with loss of rugation, more friable with petechiae, and irritation and bleeding may occur after minimal trauma. These changes lead to increased tissue fragility and higher risk of vaginal and urinary infections, irritation, dryness, urogenital pain and leakage, and vaginal tissue trauma.13,17-20 The symptoms of GSM/VVA commonly include, but are not limited to, reductions in the diameter and elasticity of the introitus and internal vaginal canal, thinning of vaginal tissues, and loss of natural lubrication, which often leads to the secondary effects of dryness, itching, irritation, dyspareunia, sexual dysfunction, and dysuria. Additionally, the female genitalia may become loose and lax over time (vaginal relaxation syndrome or VRS), leading to aesthetic concerns for many women, as well as frequently resulting in stress urinary incontinence and decreased sensation during coitus.21

One advantage of the newer minimally invasive, ablative or nonablative, energy-based treatment modalities is that they may provide an alternative solution for GSM/VVA, by favorably affecting vascularization and all levels of connective tissue of the vaginal canal. Hormonal and topical therapies have an effect mostly on the surface of the vaginal epithelium, an effect exerted only while these therapies are actively being used.22 Symptoms recur amidst poor compliance, and many women express concern over cancer-related consequences that affect successful long-term use of alternative therapies to treat symptoms of GSM/VVA.23

At present, there seems to be a paucity of data on the long-term safety, efficacy, and clinical outcomes of the various energy-based treatment modalities (lasers and RF) now available. This study supports recent findings in the literature for one-year outcome in a postmenopausal population investigated for long-term changes in vaginal health and subjective assessments of VVA/GSM symptoms following three fractional CO2 laser treatments. Additionally, histological changes in the epithelium and lamina propria were investigated at three and six months after the third treatment (at approximately 5 and 8 months postbaseline biopsies).

METHODS

Study Design

This prospective, investigational IRB-approved study was conducted at two US clinics. Study enrollment took place from July 2015 through February 2016. Study participants included postmenopausal women presenting to the clinic with symptoms of VVA (vaginal dryness, irritation, soreness, or dyspareunia associated with this condition). Study inclusion criteria included: absence of menstruation for at least 12 months; unresponsive to or dissatisfied with previous local estrogen therapy (with a washout period for the use of hormone replacement therapy, either systemic or local, within the six months prior to study enrollment); desire to maintain sexual activity and currently experiencing sexual activity at least once a month; previous vaginal reconstructive surgery or treatment for vaginal tightening within the past 12 months; previous laser or RF treatment within the prior six months; prolapse stage ≥II, according to the pelvic organ prolapse quantification (ICS-POP-Q) system; acute or recurrent urinary tract infections; active genital infections; undiagnosed vaginal bleeding; anticoagulation medications one week prior to and during the treatment course; currently using immunosuppressive medications or use of systemic corticosteroid therapy six months prior to and throughout the course of the study; suffering from hormonal imbalance or any serious disease or chronic condition that could interfere with study compliance excluded participation in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Salus Institutional Review Board, and informed written consent was obtained from all study patients.

Study Procedure

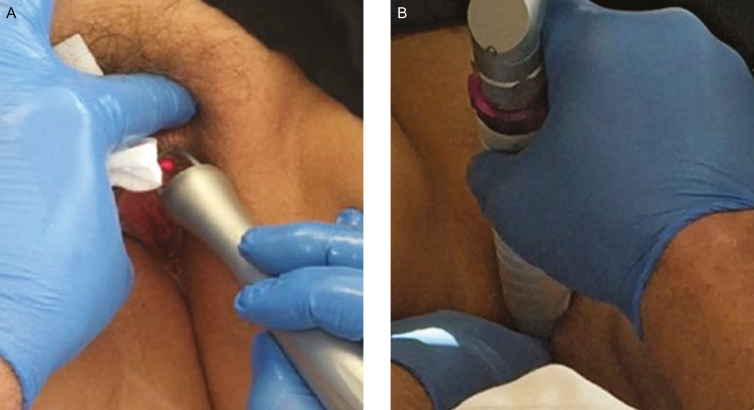

Postmenopausal women were treated extravaginally (Figure 1A) and internally (Figure 1B) with a fractional CO2 laser (CO2RE Intima, Syneron Candela, Wayland, MA). Patients underwent a series of three monthly treatments, following a similar treatment protocol to a report in the literature of CO2 vaginal laser treatment.7 The procedures were performed by the study investigator (J.S.) at the plastic surgery practice and by the study investigator (G.M.) at the obstetrics and gynecology clinic. A gynecological exam of the vaginal canal for evidence of active infection and of the vestibule and introitus for signs of injury or bleeding was performed prior to treatment. An examination of the vulvar skin was also done to look for characteristic color changes and signs of atrophy. Treatment to the vaginal canal was performed using the following settings: square pattern and deep mode with the internal handpiece, fractional density of 4% to 5%, and energy level of 50 to 60 mJ. The handpiece was inserted into the vaginal canal (up to 12 cm). Several drops of baby oil were used for more comfortable insertion into the introitus. The handpiece was positioned with contact to the vaginal wall and was rotated to apply up to 16 pulses at each 1 cm marking, until a 4 to 5 cm depth. The vaginal canal was treated with two to three passes. Anesthesia was not used for internal treatment to the vaginal canal.

Figure 1.

(A) Treatment with the external fractional CO2 laser handpiece. (B) Treatment with the internal fractional CO2 laser handpiece.

External treatments were performed with a separate handpiece, using deep mode and the hexagon or square pattern. A thick layer (approximately 1 g) of topical anesthetic (EMLA CREAM, ACTAVIS, Parsippany, NJ) was applied to the labia minora and majora just prior to external treatment. Single passes were administered at energy level of 45 to 60 mJ and 4% to 5% fractional density. Patients received three treatments at an interval of three to four weeks between treatments. The procedure was performed in the outpatient clinics and did not require systemic analgesia/anesthesia. Patients were recommended to avoid coital sexual activity and tampon use for at least seven days after treatment.

Vaginal biopsy samples were taken, by one study investigator (J.S.), from several patients presenting with visibly atrophied vaginal tissue immediately before the first treatment and at the 3-month and 6-month follow ups after a series of three treatments. The baseline biopsy was taken from the left vaginal sidewall at 2 cm inside the introitus (where the wall was well rugated), and the posttreatment biopsy was taken from the right vaginal sidewall, also at 2 cm inside the introitus. Biopsies were evaluated (CPA Lab, Louisville, KY) for histological changes to vaginal canal tissue following treatment and compared to the baseline pretreatment biopsies for each patient.

Data Assessments

The primary objective of this investigational study was to evaluate improvement in vaginal health at three months following the series of three CO2 laser treatments and to evaluate if improvement was maintained at long-term follow up to one year. The vaginal health index (VHI), a quantitative assessment of vaginal health, was performed by the investigator to assess changes in vaginal elasticity, fluid volume, vaginal pH level, epithelial integrity, and moisture after treatment and at follow ups (1, 3, 6, and 12 months) after the final treatment compared to baseline. The VHI scale ranges from 5 (severe) to 25 (normal) across all five parameters.

A visual analog scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) was used to measure discomfort associated with probe insertion, probe rotation/retraction, and laser application (a blank copy of this form is available online as Appendix A).

At baseline and at the same follow-up time points, patients completed the following questionnaires during the in-office study visits. The questionnaires were not completed anonymously.

(1) ICIQ-Urinary Incontinence Form. A validated questionnaire on urinary incontinence to assess the impact of symptoms of incontinence on quality of life (a blank copy of this questionnaire is available online as Appendix B).24

(2) The Female Sexual Functional Index (FSFI) questionnaire. A 19-item questionnaire developed as a brief, multidimensional, self-reported instrument for assessing the key dimensions of sexual function in women (a blank copy of this questionnaire is available online as Appendix C).25

(3) Severity of symptoms of vaginal dryness, burning sensation, itching, dyspareunia, and dysuria, using a 10-point numerical scale response (NSR) from 0 = No symptoms to 10 = Worst possible symptoms (a blank copy of this questionnaire is available online as Appendix D).

(4) A 5-point Likert scale questionnaire for satisfaction.

Differences between baseline and follow-up scores were analyzed by t test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Forty-three (43) postmenopausal females (mean age, 56 ± 8 years; range, 39-74 years) were enrolled at the two sites. Of the 43 patients enrolled, 40 patients completed all three treatment sessions and participated in the long-term 6-month and 12-month follow ups. Two patients at six months and one patient at 12 months provided subjective questionnaires, but were not available for VHI assessment at the clinic due to nonstudy related personal reasons (ie, death in the family).

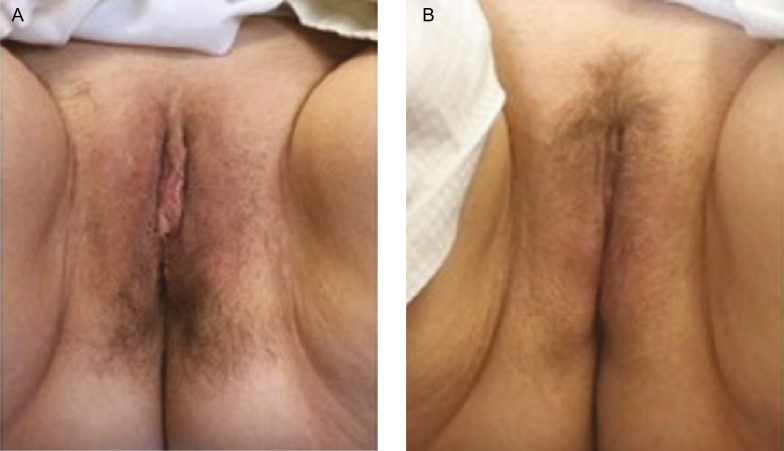

Treatment time varied according to the number of 1 cm depths treated in the vaginal canal (mean, 6 depths; range, 4-8 depths). Mean duration for the internal treatments was 6 ± 3 minutes and 3 ± 2 minutes for the external treatments. An example of improvement to the labial and vulvar tissue following the three external treatments is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(A) Pretreatment clinical photograph of a 60-year-old woman presenting with vaginal atrophy. (B) Photograph at 5 months postbaseline demonstrating improvement in labial and vulvar tissue following three external treatments with 20 to 22 pulses and 45 millijoules energy applied to the treatment area at each session.

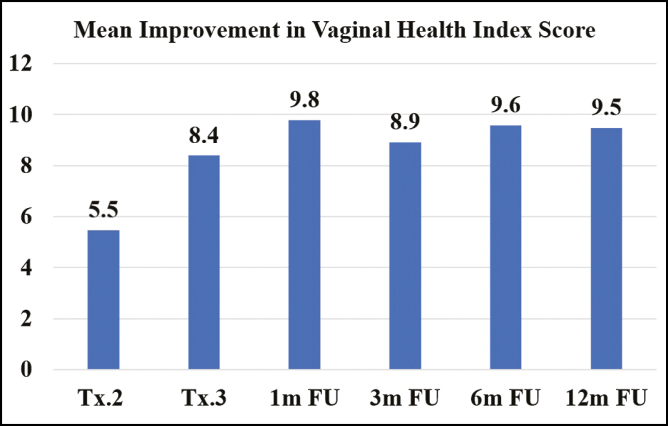

Investigator VHI Assessments

Patients were postmenopausal for one to 34 years prior to treatment, and atrophic symptoms and severity varied in the study population. The mean VHI at baseline, as assessed by the study investigators, was 11.3 ± 3.2 (range, 5-18). Following the first treatment, 90% (36/40) of the patients demonstrated statistically significant improvement in vaginal health (P < 0.001), with an average VHI increase of 5.5 ± 3.7 points compared to baseline (Figure 3). The improvement rate increased with treatment and during follow up. Following the second treatment, 98% (39/40) of patients showed significant improvement, with a mean improvement of 8.4 ± 3.7 points in the VHI (P < 0.001). The one patient who did not demonstrate improvement following the second treatment did, however, experience improvement of 6 points on the VHI scale at the 1-month follow up after the third treatment. At both the 1-month and 3-month follow ups after the third treatment, all patients continued to have significant improvement (P < 0.001) with a mean VHI increase of 9.8 ± 3.2 and 8.9 ± 3.3 points, respectively. All patients evaluated at the long-term follow ups at six (n = 38) and 12 months (n = 39) following the third treatment continued to experience significant improvement (P < 0.001) in VHI with a mean increase of 9.6 ± 3.3 and 9.5 ± 3.3 points, respectively.

Figure 3.

Mean improvement in vaginal health index (VHI) at posttreatment visits.

A positive significant correlation was found between baseline VHI and VHI improvement level at each of the follow-up visits (P < 0.001). Patients with the lowest baseline VHI experienced the greatest improvement with treatment (Pearson correlation coefficients of −0.564, −0.625, −0.613, and −0.570 at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow ups, respectively).

Subjective VVA/GSM Assessments

At baseline prior to the first treatment, symptoms of dryness, dyspareunia, and burning sensation were prevalent with 88% (35/40), 78% (31/40), and 65% (26/40) of patients reporting these symptoms, respectively. Mean severity (0 = no symptoms to 10 = worst symptoms) was 7.1 ± 3.3, 5.9 ± 4.1, and 4.2 ± 3.9 reported for dryness, dyspareunia, and burning sensation, respectively. Patients reported less suffering from vaginal itching (43%, 17/40) and dysuria (25%, 10/40), with mean severity of 2.1 ± 2.8 and 1.4 ± 2.9, respectively.

For patients who experienced VVA symptoms (score greater than 0) at baseline, improvement increased with successive treatment. Following the first treatment, 83% (29/35), 65% (20/31), and 85% (22/26) of the patients reported improvement in symptoms of dryness, dyspareunia, and burning sensation, respectively, while 89% (17/19) of the patients reported improvement in itching and 70% (7/10) for dysuria. Improvement remained highly significant (P < 0.001) for dryness, dyspareunia, and burning) at the 6-month follow up. Amelioration of prevalent treatment symptoms was maintained at the 12-month follow up with 91% (32/35), 87% (27/31), and 88% (23/26) of the patients reporting improvement in symptoms of dryness, dyspareunia, and burning sensation, respectively. Improvement in vaginal itching and dysuria was also maintained with 89% (17/19) and 90% (9/10) of the patients reporting improvement, respectively. Mean severity of dryness decreased from 7.1 at baseline to 4.6, dyspareunia decreased from 5.9 to 3.1, and burning sensation decreased from 4.2 to 3.2. Itching and dysuria, although minimal at baseline, also improved from a mean severity of 2.1 and 1.4 at baseline to 1.4 and 1.1 at the 12-month follow up, respectively.

Subjective ICIQ Assessments

Based on the ICIQ reports at baseline, 25 of the 40 study patients (62.5%) experienced some degree of urine leaking (score greater than 0). Following the first treatment, 52% (13/25) of the patients experienced a reduction in frequency of leaking by at least 1-grade on the 5-point questionnaire item. At the 6-month evaluation, 18 patients (72%) experienced improvement, while the remaining seven patients (28%) had no change in score. At the 12-month follow up, 64% (16/25) of the patients continued to experience improvement, while 36% (9/25) of patients experienced a return to the baseline frequency of urine leaking. The degree to which urine leaking affected daily life remained significantly improved at both the 6-month and 12-month follow ups (P < 0.001).

There were three patients with a score of “0” (never leak urine) at baseline, who then indicated occasional leaking (score of 1) at the 6-month and/or 12-month follow ups. One of the women reported occasional leaking at only the 12-month follow up, while the other two women reported occasional leaking at both follow ups. Two of the three women had a low VHI of “9” at pretreatment baseline, while the other woman had a score of “12.” All three patients experienced significant improvement of 6 points on the VHI after the first treatment (pretreatment 2 visit), which increased with treatment and follow up to a 9-point or 10-point improvement by 12 months.

Subjective FSFI Questionnaire

The Female Sexual Functional Index (FSFI) questionnaire includes 19 questions that are classified into six categories (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain). The aggregated score is a sum of weighted answers for each item. Overall, the maximum score is 36.0 (high level of sexual functional) and the minimum score is 2.0 (low level of sexual functional). At baseline, the mean FSFI score was 17.7 ± 5.97 (range, 5.4-33.9). Significant improvement (P < 0.001) was observed in 88% (35/40) of patients already after the first treatment and remained significant along the study course with mean improvement levels of 5.93 ± 5.34, 8.68 ± 6.11, 9.51 ± 6.87, 8.28 ± 7.49, 8.84 ± 7.47, and 7.65 ± 8.42 at second and third treatments and at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up visits, respectively. The rate of improvement was also maintained at the 12-month follow up with 83% (33/40) of patients continuing to experience improvement in the FSFI.

In addition to the overall score for FSFI, the six categories were analyzed for changes in individual domains following treatment and during follow up. As with the overall score, there was statistically significant improvement in each of the six sexual functional categories (P < 0.05, t test for each category) following the first treatment. Significant improvement was also observed following subsequent treatments (posttreatments 2 and 3) and at all follow ups. Mean improvement levels of 0.8 (desire), 0.9 (arousal), 1.4 (lubrication), 0.9 (orgasm), 1.2 (satisfaction), and 1.3 (pain) over baseline scores of 2.3, 2.7, 2.2, 2.7, 2.7, and 2.2, respectively, were observed at the 12-month follow up. Furthermore, most of the patients had improvement in all six sexual functional categories following the first treatment with 68% of patients reporting improvement in desire, 75% in arousal, 75% in lubrication, 65% in orgasm, 80% in satisfaction, and 73% in pain. The percentage of patients reporting improvement in all six domains was similar at the 12-month follow up with 68% of patients reporting improvement in desire, 75% in arousal, 83% in lubrication, 60% in orgasm, 75% in satisfaction, and 73% in pain.

Patient Satisfaction

Long-term patient satisfaction remained high during the study with 68% (27/40) of patients reporting satisfaction at the 6-month follow up that improved to 75% (30/40) at the 12-month follow up. There was an increase in the degree of satisfaction over time with 50% of the patients reporting that they were “very satisfied” with treatment at the 12-month follow up compared to 28% at the 1-month follow up.

Histology Findings

Histological changes in the epithelium and lamina propria, following fractional CO2 laser treatments, correlated with clinical findings of vaginal hydration and pH. At five months postbaseline (3-month follow up), biopsies showed increased collagen and elastin staining (Figure 4), as well as a thicker epithelium with an increased number of cell layers and a better degree of surface maturation (increase in the ratio of parabasal, intermediate, and superficial cells showing an estrogenic effect on the body). Histological findings at eight months postbaseline (6-month follow up) showed increased submucosal vascularity, as well as increased collagen deposits and elastic fibers (Figure 5). Collagen deposits (observed with trichrome stain) appeared more prominent posttreatment (Figure 6). An increased staining pattern around the blood vessels was also observed (Figure 7).

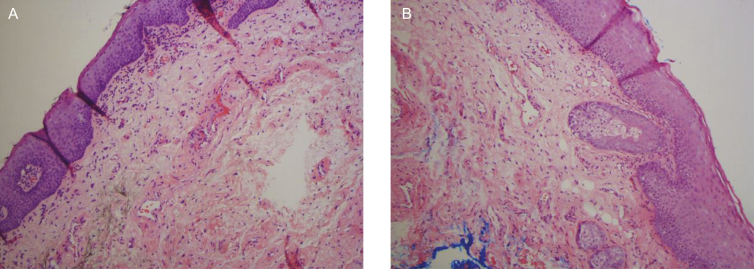

Figure 4.

(A) Pretreatment histology of a 71-year-old woman. (B) At 5-months postbaseline, histology showed increased collagen and elastin staining, as well as a thicker epithelium with an increased number of cell layers and a better degree of surface maturation.

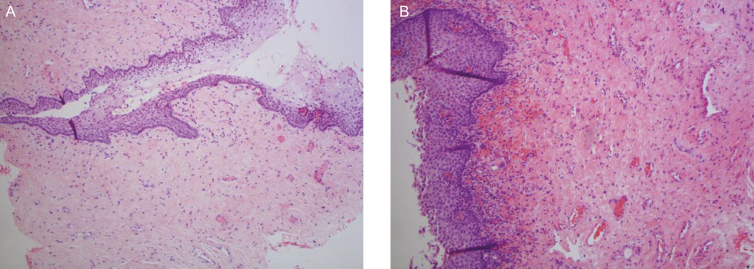

Figure 5.

(A) Pretreatment histology of a 59-year-old woman. (B) At 8-months postbaseline, histological findings showed increased submucosal vascularity, as well as increased collagen deposits and elastic fibers.

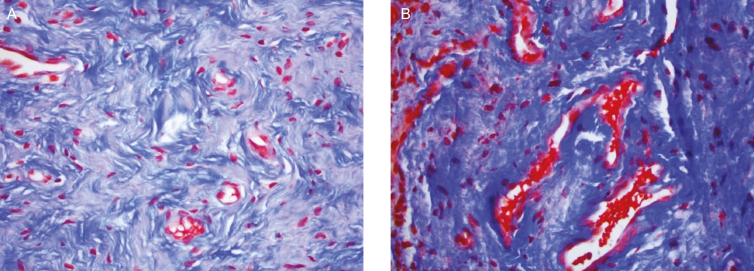

Figure 6.

(A) Pretreatment histology of a 59-year-old woman. (B) At 8-months postbaseline, collagen deposits (observed with trichrome stain) appeared more prominent posttreatment.

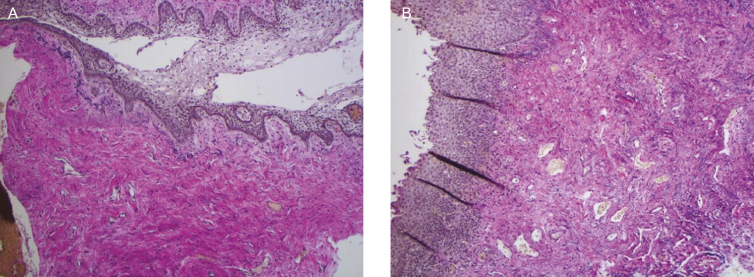

Figure 7.

(A) Pretreatment histology of a 59-year-old woman. (B) At 8-months postbaseline, more prominent vascularity and elastic fibers were observed posttreatment (Verhoeff’s elastic stain).

Safety Evaluation

Forty-three (43) patients underwent one treatment session and were included in the safety evaluation. A total of 40 patients received all three treatment sessions and were evaluated for safety and efficacy. A total of 123 sessions (123 internal treatments and 118 external treatments) were conducted during the study period. Mean treatment time for the internal procedure was 6 ± 2 minutes and 3 ± 2 minutes for the external treatment phase. The treatment phases were associated with none to mild discomfort for 91%, 92%, and 97% of reports following probe insertion, probe movement, and laser application, respectively. Mean pain score on the 0 (no pain) to 10-scale was 1.99 ± 2.36, 1.46 ± 1.93, and 1.32 ± 1.70 for all treatments following probe insertion, probe movement, and laser application, respectively.

Common immediate treatment responses, reported by the treating study investigator following the treatment, were mild to moderate erythema (54%) and edema (55%) observed with treatments. Mild bleeding occurred following two treatments and mild tissue retraction following one treatment. As with most energy-based treatments to tissue, these were anticipated treatment responses, and resolved within 24 hours without intervention.

Patients reported seven treatment-related adverse events. These events occurred following the first treatment only and were reported at the 1-week follow up after the first treatment. These included two cases (1.6%) of mild itching and discomfort; one case (0.8%) of mild itching and swelling; two cases (1.6%) of moderate burning sensation with urination; 1 case (0.8%) of moderate soreness and spotting, and one case (0.8%) of major itching. The patients experienced itching or discomfort of the vulvar tissue, which was alleviated with ice pack application and/or topical antihistamine gel for itching. Additionally, there was one case of a possible yeast infection for which prescription antifungal cream was prescribed. No patient had more than one adverse event, and there were no adverse events with subsequent treatments. No adverse events were reported at any of the follow ups. There were no episodes of excessive lubrication or excessive tightness at the 12-month follow up.

DISCUSSION

Energy-based devices have long demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in rejuvenation of the face and neck, and now appear to have extended this clinical application to the revitalization of vaginal and vulvar tissues.6 In general, RF devices produce tissue contraction as heat develops upon meeting tissue impedance.8,26 The CO2 laser (10,600 nm) fractionally ablates the tissue, causing immediate heat-induced collagen contraction and subsequent tissue remodeling, while the Er:YAG laser (2940 nm) produces wound contraction secondary to tissue heating.27

Fractional CO2 laser treatments improve blood flow in vaginal tissues via a heat response to restore elasticity and moisture of the vaginal canal, improve the extracellular matrix of the mucosal structures improving muscle tone and function, reduce frequent infection and chronic vaginitis via restoration of the barrier function of the healthy vaginal epithelium, and even improve the cosmesis of the external vulvar tissues, urinary continence, and sexual function.7,11,12,28-32

Our study includes both objective and subjective 12-month data with long-term histological results from two clinical sites in the United States. Our findings support a persistent improvement in the troublesome symptoms of VVA, associated with GSM, a full year after a series of three treatments with a fractional CO2 laser. Overall improvements in dryness, itching, dyspareunia, burning sensation, and dysuria were noted at one year, with the most pronounced improvements remaining highly significant at the 12-month follow up for dryness, dyspareunia, and vaginal burning sensation. Improvements in VHI were seen in 90% of patients after the first treatment, 98% after the second treatment, and 100% after the third treatment, with an average VHI increase of almost 10 points collectively. Taken together, these results suggest a durable positive effect on the vaginal symptoms of GSM one year after treatment with the fractional CO2 laser. A significant portion of our menopausal patient population (62.5%) did complain of some degree of urinary leakage, and 72% of these experienced a reduction in the frequency of urinary leakage at 6-month follow up. At the 12-month follow up, 64% of the patients continued to experience improvement, while 36% experienced a return to the baseline frequency of urine leaking. While this suggests that fractional CO2 treatment may have a positive effect on urinary leakage, this warrants further specific study investigation.

Although the baseline FSFI in the current study was higher than that reported for the population in Sokol and Karram’s published study,7 the average improvement in FSFI of 8.9 ± 7.3 reported at three months following a series of CO2 laser treatments to the vaginal canal was similar to the average improvement of 8.3 ± 7.5 reported at the 3-month follow up in the current study. Overall improvement was maintained at the 12-month follow up in both studies. Additionally, we report on mean improvement observed in all six categories of sexual function following the first treatment and at follow ups.

Since the delivery of fractional CO2 energy creates microscopic thermal treatment zones of ablation, coagulation (or some combination of the two), rather than complete 100% surface ablation, there remains surrounding normal skin structures that are unaffected and which then promote rapid reepithelialization and healing, so that any true recovery time is drastically reduced. This finding of rapid, asymptomatic healing with high safety measures was supported in our patient experience by the lack of reported significant edema, exudate, or complications after laser treatment.

The normalization of pH to an acidic level in treated patients supports the effectiveness of the laser in restoring the local lactobacilli population of the vaginal canal, an organism which requires glycogen for proper metabolism and maintenance of the normal barrier function of the vagina. Histology of the inspected samples taken from patients prior to the treatment series showed typical findings of the lack of estrogen, whereas biopsies posttreatment showed thickening of the epithelium and basement membrane, improved vascularization, reduced inflammation, increased collagen, fibrin, and elastin content, as well as higher water content.

Along with a surge in patient demand for treatment alternatives for the symptoms of GSM/VVA, and along with a host of newly available technology, we have also seen a dramatic increase in the numbers and different specialties of practitioners interested in treating these patients, so that it is imperative that treatment recommendations, guidelines, and efficacy data continue to evolve. A recent review, edited by a panel of international experts, described a number of clinical studies that have evaluated the effect of energy-based tissue heating of the vaginal wall in restoring structure and functionality.6 Another recent review examined the literature for studies using radiofrequency and laser devices to evaluate the effectiveness of these devices for both premenopausal and postmenopausal women with laxity and/or atrophy at the histologic and clinical level.33

Histological findings from ex vivo and biopsied atrophic vaginal tissue have demonstrated restoration of vaginal mucosal structure following CO2 laser application.28,29 Clinical findings from energy-based treatments have shown improvement in self-reported sexual function, objective measurement of vaginal canal dimensions, mild to moderate urinary incontinence, and decreased severity of vaginal pain, burning, itching, dryness, dyspareunia, and dysuria associated with vulvovaginal atrophy/genitourinary syndrome of menopause (VVA/GSM).7,11,12,30-32

One caveat of these minimally invasive treatment options is the paucity of long-term clinical outcome. Most studies evaluated patients at three or six months following a series of treatments. Histological findings were reported for up to three months posttreatment. A 12-month extension of a previous exploratory study reported slight nonsignificant deterioration in premenopausal women treated with dynamic quadripolar RF for vaginal laxity, while the postmenopausal study arm experienced persistent improvement in self-evaluation of VVA/GSM symptoms.12 Another recent study reported that the one-year outcome of average VHI remained statistically significant following CO2 laser treatment.7

Potential limitations of this study include lack of a control arm to account for placebo effect and lack of comparison therapy; however, study participation (93%, 40/43) and patient satisfaction (75%, 30/40) were high at the completed 12-month follow up. A recent publication of a large-scale study at nine international centers evaluated the effect of a single radiofrequency treatment on subjective reports of vaginal laxity in premenopausal women at six months after treatment.34 Although there was a significant placebo effect (19.6% of participants reported no vaginal laxity following treatment), the effect of treatment was significantly greater with active treatment (43.5%, P < 0.01). Furthermore, there was no placebo effect on female sexual function, based on the FSFI findings. In the current study, the effect of CO2 treatments on vaginal mucosa resulting in improvement in VVA symptoms was evaluated. As fractional CO2 lasers induce superficial tissue shrinkage, as well as deep stimulation of the collagen layer of the submucosa by heating and energy absorption,6 it is unlikely that VHI improvement maintained at 12 months after treatment could be achieved by a placebo effect.

Another limitation of the study is that the effect of duration from last menstruation was not evaluated in the study. Further investigation is warranted to evaluate if a woman who is further away from last menstruation is more refractory or might possess more inherent tissue damage than a woman who is very close to the last menstruation prior to the treatment series. As urinary incontinence was not an inclusion criterion for study participation, the study was not powered to test the effect of CO2 treatments on urinary incontinence. The findings suggest that treatments may result in subjective improvement and lend a positive impact on daily life for at least six months following the treatment series. This should be further investigated. The study inclusion criterion of sexual activity once a month, the small number of patients, and subjective reporting/recall bias all have the potential to affect study outcome.

CONCLUSION

These findings collectively support the premise that fractional CO2 laser treatment provides an effective and long-lasting treatment option for menopausal patients suffering from VVA associated with GSM. As there is a paucity of long-term clinical outcome reported in the literature, this study adds to the growing evidence-based reports of efficacy and safety beyond three months. The laser offers an effective alternative treatment option especially for patients who are not compliant with or who do not wish to use hormonal or topical therapies (or for whom hormonal options are ill advised). We have observed a trend of diminishing effect beyond the 12-month follow up, although the reported improvement was still highly significant at that point, and this suggests that a retreatment interval of 12 to 18 months may be beneficial, given that the etiological lack of estrogen state will persist. A study with a larger sample size and repeat treatments after 12 to 18 months is warranted. Further study for the application of this laser modality to treat stress urinary incontinence and improve sexual function is also needed.

Disclosures

Dr. Samuels performs research and evaluates devices for Syneron Candela and may be provided with devices at a discount. Dr. Garcia performs research and evaluates devices for Syneron Candela and may be provided with devices at a discount.

Funding

Compensation in the form of a device purchase discount and to cover associated staff costs was provided at the completion of the 1-year study by Syneron Medical Ltd.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Cosmetic surgery national data bank statistics. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(Suppl 2):1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tierney EP, Hanke CW. Ablative fractionated CO2, laser resurfacing for the neck: prospective study and review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(8):723-731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Orringer JS, Rittié L, Baker D, Voorhees JJ, Fisher G. Molecular mechanisms of nonablative fractionated laser resurfacing. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(4):757-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peterson JD, Goldman MP. Rejuvenation of the aging chest: a review and our experience. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(5):555-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ong MW, Bashir SJ. Fractional laser resurfacing for acne scars: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(6):1160-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. . Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):137-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sokol ER, Karram MM. Use of a novel fractional CO2 laser for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: 1-year outcomes. Menopause. 2017;24(7):810-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karcher C, Sadick N. Vaginal rejuvenation using energy-based devices. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2016;2(3):85-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Zerbinati N, et al. . A 12-week treatment with fractional CO2 laser for vulvovaginal atrophy: a pilot study. Climacteric. 2014;17(4):363-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perino A, Calligaro A, Forlani F, et al. . Vulvo-vaginal atrophy: a new treatment modality using thermo-ablative fractional CO2 laser. Maturitas. 2015;80(3):296-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee MS. Treatment of vaginal relaxation syndrome with an Erbium:YAG laser using 90° and 360° scanning scopes: a pilot study & short-term results. Laser Ther. 2014;23(2):129-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vicariotto F, DE Seta F, Faoro V, Raichi M. Dynamic quadripolar radiofrequency treatment of vaginal laxity/menopausal vulvo-vaginal atrophy: 12-month efficacy and safety. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(4):342-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Maturitas. 2014;79(3):349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mac Bride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):87-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nappi RE, Palacios S. Impact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopause. Climacteric. 2014;17(1):3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ivankovich MB, Fenton KA, Douglas JM Jr. Considerations for national public health leadership in advancing sexual health. Public Health Rep. 2013;128(Suppl 1):102-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gaspar A, Brandi H, Gomez V, Luque D. Efficacy of Erbium:YAG laser treatment compared to topical estriol treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):160-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20(9):888-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2009;6(8):2133-2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bachmann GA, Nevadunsky NS. Diagnosis and treatment of atrophic vaginitis. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(10): 3090-3096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iosif CS, Bekassy Z. Prevalence of genito-urinary symptoms in the late menopause. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1984;63(3):257-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnston SL, Farrell SA, Bouchard C, et al. ; SOGC Joint Committee-Clinical Practice Gynaecology and Urogynaecology The detection and management of vaginal atrophy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26(5):503-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. von Schoultz E, Rutqvist LE; Stockholm Breast Cancer Study Group Menopausal hormone therapy after breast cancer: the Stockholm randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(7):533-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23(4):322-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. . The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beasley KL, Weiss RA. Radiofrequency in cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(1):79-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fitzpatrick RE, Rostan EF, Marchell N. Collagen tightening induced by carbon dioxide laser versus erbium: YAG laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2000;27(5):395-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Salvatore S, Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Athanasiou S, et al. . Histological study on the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal tissue: an ex vivo study. Menopause. 2015;22(8):845-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zerbinati N, Serati M, Origoni M, et al. . Microscopic and ultrastructural modifications of postmenopausal atrophic vaginal mucosa after fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(1):429-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arroyo C. Fractional CO2 laser treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy symptoms and vaginal rejuvenation in perimenopausal women. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:591-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Millheiser LS, Pauls RN, Herbst SJ, Chen BH. Radiofrequency treatment of vaginal laxity after vaginal delivery: nonsurgical vaginal tightening. J Sex Med. 2010;7(9):3088-3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Salvatore S, Nappi RE, Parma M, et al. . Sexual function after fractional microablative CO₂ laser in women with vulvovaginal atrophy. Climacteric. 2015;18(2): 219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qureshi AA, Tenenbaum MM, Myckatyn TM. Nonsurgical vulvovaginal rejuvenation with radiofrequency and laser devices: a literature review and comprehensive update for aesthetic surgeons. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38(3):302-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Krychman M, Rowan CG, Allan BB, et al. . Effect of single-treatment, surface-cooled radiofrequency therapy on vaginal laxity and female sexual function: the VIVEVE I randomized controlled trial. J Sex Med. 2017;14(2): 215-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.