Abstract

Background

Infections of the ears, paranasal sinuses, nose and throat are very common and represent a serious issue for the healthcare system. Bacterial biofilms have been linked to upper respiratory tract infections and antibiotic resistance, raising serious concerns regarding the therapeutic management of such infections. In this context, novel strategies able to fight biofilms may be therapeutically beneficial and offer a valid alternative to conventional antimicrobials. Biofilms consist of mixed microbial communities, which interact with other species in the surroundings and communicate through signaling molecules. These interactions may result in antagonistic effects, which can be exploited in the fight against infections in a sort of “bacteria therapy”. Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus oralis are α-hemolytic streptococci isolated from the human pharynx of healthy individuals. Several studies on otitis-prone children demonstrated that their intranasal administration is safe and well tolerated and is able to reduce the risk of acute otitis media. The aim of this research is to assess S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a for the ability to interfere with biofilm of typical upper respiratory tract pathogens.

Methods

To investigate if soluble substances secreted by the two streptococci could inhibit biofilm development of the selected pathogenic strains, co-cultures were performed with the use of transwell inserts. Mixed-species biofilms were also produced, in order to evaluate if the inhibition of biofilm formation might require direct contact. Biofilm production was investigated by means of a spectrophotometric assay and by confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Results

We observed that S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a are able to inhibit the biofilm formation capacity of selected pathogens and even to disperse their pre-formed biofilms. Diffusible molecules secreted by the two streptococci and lowered pH of the medium revealed to be implied in the mechanisms of anti-biofilm activity.

Conclusions

S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a possess desirable characteristics as probiotic for the treatment and prevention of infections of the upper airways. However, the nature of the inhibition appear to be multifactorial and additional studies are required to get further insights.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-018-3576-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Biofilm, Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus salivarius, Probiotics, Respiratory tract infections

Background

Despite the presence of mechanical barriers and host immune defenses, the upper respiratory tract offers an easy access to pathogens involved in acute and chronic infections of ears, paranasal sinuses, nose and throat. The majority of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) are commonly mild and caused by viruses; however, URTIs can also be mediated by bacteria, representing a clinical challenge related to a higher morbidity and a chronic progress of the disease [1]. Moreover, URTIs have been associated with the presence of microbial biofilm, which results in chronic infections characterized by remitting course and resistance to medical management [2, 3]. Biofilm is defined as a “structured community of microorganisms enveloped in a self-produced polymeric matrix, adherent to an inert or living surface” [4]. Once the biofilm is established, the infection becomes more and more difficult to eradicate, because the microbes residing into the matrix are protected from host immune system and antibiotics [5]. Consequently, the microbial biofilm makes infections persistent and more refractory to treatments.

Biofilms usually consist of mixed microbial communities able to interact with other species in the surroundings and to communicate through signaling molecules [6]. These interspecies interactions may result in either mutualistic or antagonistic effects [7, 8]. The importance of the normal microbiota in the protection against URTIs has been widely demonstrated. However, an imbalance in the physiological flora composition may lead to the colonization and infection of the mucosae by opportunistic pathogens.

For instance, it has been noted that otitis-prone children were characterized by a significantly lower number of α-hemolytic streptococci in their nasopharyngeal flora than non-otitis-prone ones [9, 10], opening the possibility to administer living microorganisms as probiotics to confer health benefits to the host [11]. Indeed, the use of bacterial species deriving from healthy human oral microbiota as a probiotic for the treatment of URTIs has been proposed as a valid alternative to antibiotics, contributing to the re-establishment of a balanced flora while reducing or preventing the adhesion and colonization of potential pathogens.

Alpha-hemolytic streptococci (i.e. Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus oralis) isolated from human pharynx are known to be early colonizers of upper respiratory mucosae and their numeric predominance is suggestive of a healthy flora [12, 13]. Furthermore, these species possess desirable characteristics, such as production of bacteriocin like Colicin V and bacteriocin-like peptides [14, 15] and both act as pioneer colonizer. Nonetheless, S. salivarius and S. oralis own a high affinity to human mucosae, protecting epithelial cells from pathogen adherence, internalization, and potential cytotoxic effects. For this reason, these α-hemolytic streptococci represent the predominant species in the upper respiratory healthy flora and they can selectively influence the composition of the microbiota [16–19]. In the past decades, several studies have demonstrated the intranasal administration of S. salivarius and S. oralis as safe and well-tolerated strategy to reduce the risk of new episodes of acute otitis media in otitis-prone children and to decrease middle ear fluids amount in children with secretory otitis media [19–23].

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a, both isolated from a commercial product (Rinogermina®, DMG Italia Srl, Pomezia, Italy), are able to interfere with biofilm formation in vitro and to eradicate pre-formed biofilm of typical upper respiratory tract pathogens, such as Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Propionibacterium acnes. In addition, the mechanisms underlying the anti-biofilm activity of the probiotic streptococci were speculated.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture media

Clinically relevant upper respiratory tract pathogens were isolated from patients with URTIs at the Laboratory of Clinical Chemistry and Microbiology of IRCCS Galeazzi Institute, where they were routinely collected and stored. In particular, biofilm-producing strains of S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, M. catarrhalis and P. acnes were selected. The identification of the isolates was carried out by means of the Vitek2 Compact (BioMerieux, Marcy L’Etoile, France) and further confirmed by pyrosequencing (PSQ96RA, Diatech, Jesi, Italy), as described elsewhere [24]. Biofilm production was assessed by means of the spectrophotometric assay described by Christensen et al. [25]. S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a were isolated from the manufactured product and identified by biochemical assays and pyrosequencing, as described above. All strains were stored at − 80 °C in proper broths enriched with 10% glycerol (VWR Chemicals, Leuven, Belgium) until testing. Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI, bioMérieux, Marci L’Etoile, France) was used for the culture of staphylococci, BHI plus 5% of defibrinated blood (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy) for streptococci and M. catarrhalis, and thioglycollate broth (TH, Oxoid, Rodano, Italy) for P. acnes. When performing transwell and mixed species experiments (see below), S. oralis and S. salivarius were grown in the same medium needed for the tested pathogenic strain. Before the beginning of the study, the biofilm formation ability of S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a was assessed in each of the above-mentioned culture media, finding no significant differences among them (data not shown).

Interaction between S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a

To evaluate whether the reciprocal interactions between S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a could inhibit their biofilm production, co-cultures were performed with the aid of transwell inserts (microporous PET membranes with pore diameter of 0.4 μm, 1.6 × 106 pores/cm2) designed for 24-well plates (Falcon®, Corning, New York, NY, USA), as described elsewhere [26]. Wells were inoculated with 800 μL of S. salivarius 24SMB suspension and 200 μL of S. oralis 89a suspension were dispensed in the upper compartment of transwell inserts, and vice versa. Thereafter, mixed dual-species biofilms were also produced by inoculating 1 mL of a mixture of the two probiotic strains. In all the aforementioned experimental settings, S. salivarius and S. oralis were cultured in a 98:2 ratio (about 1.5 × 107 CFU/mL of S. salivarius and 3 × 105 CFU/mL of S. oralis), as that of the manufactured product. Mono-species biofilms of each strain were produced as positive controls, while medium alone was used as negative control. The experiment was performed in triplicate. Strains were incubated at 37 °C in proper conditions, and after 72 h the biofilm formation was evaluated.

Interference on biofilm formation

To investigate if soluble substances secreted by the probiotic bacteria S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a could inhibit biofilm formation by the tested strains, co-cultures were performed with the use of transwell inserts, as described above. Wells were inoculated with 800 μL of the target bacterial species (1.5 × 107 CFU/mL) and 200 μL of a mixture of S. salivarius and S. oralis in a 98:2 ratio were inoculated in the transwell inserts (about 1.5 × 107 CFU/mL of S. salivarius and 3 × 105 CFU/mL of S. oralis). Thereafter, mixed species biofilms were also produced in order to evaluate if the biofilm formation by the selected pathogens requires a direct contact with the two probiotic strains to be inhibited. Mono-species biofilms of each strain were used as positive controls, while medium alone was used as negative control. The experiment was performed in triplicate for each strain. Plates were incubated at 37 °C in proper conditions. After 24, 48 and 72 h, transwell inserts and liquid medium were removed, and the amount of biofilm was evaluated by a spectrophotometric assay as described below.

Interference on pre-formed biofilm

To investigate whether the probiotic strains were able to break an existing biofilm down, biofilm of each target strain was grown for 72 h in proper conditions and then incubated in the presence of S. salivarius and S. oralis for an additional time (24, 48 and 72 h), as previously described. Mono-species biofilm of each strain was produced as positive control, while medium alone was used as negative control. The experiment was performed in triplicate for each tested strain. At each time point, the amount of biofilm was evaluated spectrophotometrically as described below, and expressed as percentage in respect to pre-treatment level.

Spectrophotometric assay

The amount of biofilm was quantified by means of the spectrophotometric assay developed by Christensen et al. [25], adjusting the volume of reagents for 24-well plates. Briefly, at the end of each incubation time, the culture medium was removed, and two washes with sterile saline were performed in order to remove non-adherent bacteria. After air-drying, each well was stained with 1 mL of 1% crystal violet solution (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 10 min and the dye excess removed with three washes of sterile saline. Once dried, 1 mL of absolute ethanol was added to each well to solubilize the dye attached to the biofilm. An aliquot of the solubilized dye was finally transferred into a 96-wells plate for spectrophotometric reading which was performed at a wavelength of 595 nm using a microplate reader (Multiskan FC; Thermo Scientific, Milan, Italy).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy assay

The inhibition of biofilm formation was evaluated by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) assay. Specifically, biofilms were cultured on uncoated 10 mm diameter glass microscope coverslip (VWR International Srl, Milano, Italy) in 24-well plates for 72 h using the same set-up described for transwell experiments. After 72 h of incubation at proper conditions, biofilms were gently washed with sterile saline and stained with Filmtracer™ LIVE/DEAD™ Biofilm Viability Kit (Thermo Fisher Diagnostics SpA, Rodano, Italy), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the staining solution was prepared by adding 3 μL of SYTO9 and 3 μL of propidium iodide to 1 mL of filter-sterilized water. Biofilm samples were stained by incubation with 20 μL of staining solution for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. After incubation, samples were washed with sterile saline and examined with an upright TCS SP8 (Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) using a 20× dry objective (HC PL FLUOTAR 20×/0.50 DRY) plus a 2× electronic zoom. A 488 nm laser line was used to excite SYTO9, while a 552 nm laser line was used to excite propidium iodide. Sequential optical sections of 1.27 μm were collected along the z-axis over the complete thickness of the sample. Images from at least three randomly selected areas were acquired for each coverslip. The obtained images were processed with Las X (Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and analyzed with Fiji software (Fiji, ImageJ, Wayne Rasband National Institutes of Health). The following parameters were evaluated: a) the overall volume to provide an estimation of the total biomass of the biofilm; b) the live/dead cells ratio; c) the substratum coverage, as the percentage of substrate area occupied by the biofilm.

Cell-free extract interference on biofilm formation

To investigate the nature of the inhibition of pathogens biofilm formation by S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a, a cell-free extract (CFE) of the supernatant was obtained. Briefly, as described above, the probiotic strains were cultured in the upper compartment of the transwell, concomitantly with each of the tested bacterial species. After 24 h of incubation (48 h for P. acnes), the medium from both the well and the upper chamber of the transwell was collected in a 15 ml tube (Falcon®, Corning, New York, NY, USA), centrifuged for 10 min at 4200 rpm and filtered through a 0.2 μm filter (ClearLine®, Biosigma S.r.l., Cona, Italy). The resulting CFE was divided in three vials: one was not treated to assess the effect of CFE on bacterial biofilm formation; the second was neutralized to a pH value of 7.0 using NaOH 1 M; the third was heated at 100 °C for 10 min to assess the contribution of thermolabile molecules to biofilm inhibition.

To determine the activity of CFEs, biofilm formation assay was carried out on 96-well polystyrene plates (Biosigma S.r.l., Cona, Italy) by growing the pathogenic species in fresh BHI alone (for positive control) or adding ½ (v/v) or ¼ (v/v) of both treated and untreated CFE. Production of biofilm was then measured by spectrophotometric assay as described above.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analysed for statistical significance with PRISM5 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) using unpaired t test for CLSM assays, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the interaction between S. salivarius and S. oralis and the cell-free extract tests, two-way ANOVA the spectrophotometric assays. One-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA were followed by Bonferroni post hoc correction. A P-value ≤0.05 was used as the significance level.

Results

Interaction between S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a

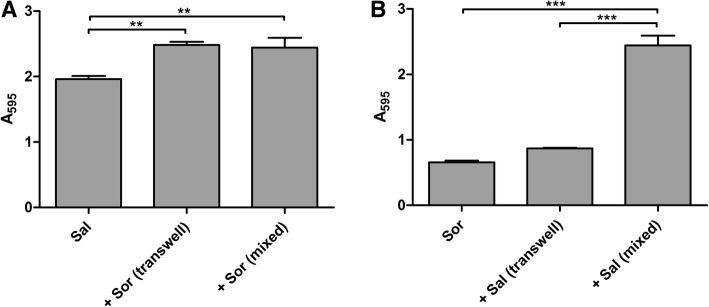

The reciprocal interaction between the two probiotic strains led to an increase in biofilm production of both S. salivarius (21%) and S. oralis (24%), compared to biofilm produced when cultured separately (Fig. 1a and b). When the two species were put in direct contact (mixed) in dual-species biofilms, a significant increase of the biofilm formation was also observed, although the contribution of each strain could not be discriminated.

Fig. 1.

Interaction between S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a. Data are expressed as mean absorbance ± standard deviation (n = 3). Sal = S. salivarius; Sor = S. oralis; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001. Panel A shows the effect of S. oralis 89a on S. salivarius 24SMB biofilm in indirect (transwell) and direct (mixed) contact. Panel B shows the effect of S. salivarius 24SMB on S. oralis 89a biofilm in indirect (transwell) and direct (mixed) contact

Interference on biofilm formation

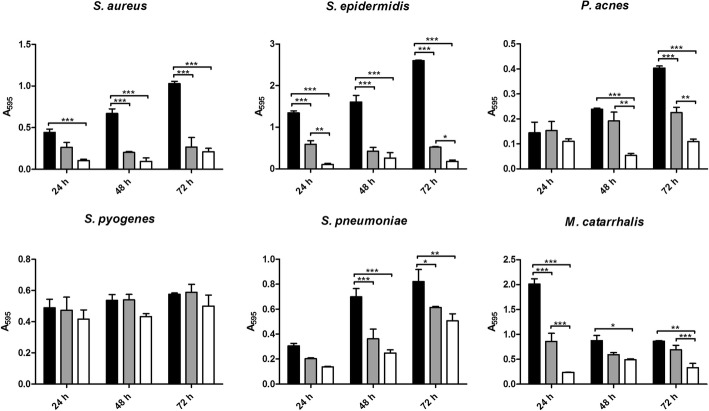

Generally, the mixture of S. salivarius and S. oralis displayed an inhibitory activity against biofilm development of all tested bacteria, except for S. pyogenes whose biofilm formation was not significantly influenced by presence of the probiotic strains (Fig. 2). Biofilm production by staphylococci was strongly affected by S. salivarius and S. oralis: significant reductions were observed at all time points in both transwell (76–86% for S. aureus and 84–92% for S. epidermidis) and mixed biofilms (40–74% for S. aureus and 56–80% for S. epidermidis), compared to controls. Significant biofilm reductions were observed for S. pneumoniae (38–66%) and P. acnes (73–77%) after 48 h and 72 h of incubation in transwell experiments, while mixed co-cultures significantly inhibited S. pneumoniae biofilm production at 48 and 72 h (25–48%) and P. acnes at 72 h (44%). Finally, S. salivarius and S. oralis showed a significant inhibitory activity against M. catarrhalis at all time points in transwell experiments (44–88%) and at 24 h in mixed ones (57%), despite a sudden biofilm reduction in controls after 24 h might have masked the true effect of the two probiotic strains. In general, biofilm reduction was always higher in transwell experiments than in mixed ones, although such difference was not always statistically significant (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of biofilm formation during time. Data are expressed as mean absorbance ± standard deviation (n = 3). Black bars = controls; grey bars = mixed co-cultures; white bars = transwell co-cultures; * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001

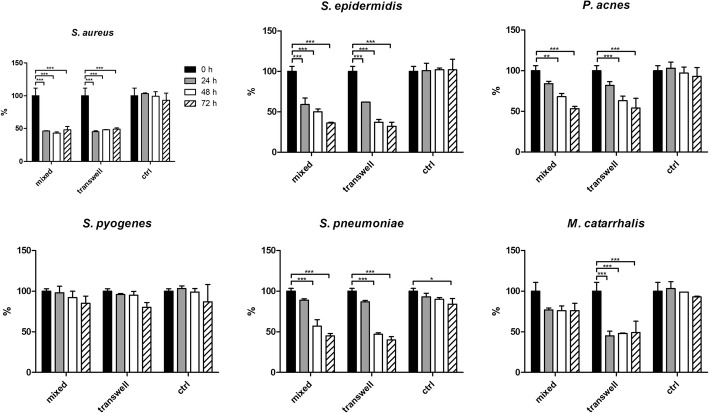

Interference on pre-formed biofilm

The combination of S. salivarius and S. oralis was able to significantly disrupt the pre-formed biofilm of all tested bacteria. Conversely, S. pyogenes biofilm was only slightly affected by the probiotic strains (Fig. 3). After 24 h of incubation, almost the 50% of the mature biofilm of S. aureus was eradicated because of the presence of S. salivarius and S. oralis in both transwell and mixed experiments, and such inhibition was maintained during time. Similarly, M. catarrhalis biofilm was significantly reduced in experiments using the transwell system, with a constant reduction of about 50% at all the time points. On the other hand, the anti-biofilm activity of the probiotic strains against S. epidermidis, P. acnes and S. pneumoniae seemed to increase during time, showing the highest percentages of biofilm reduction at 72 h (64 and 68% for S. epidermidis, 46 and 47% for P. acnes and 55 and 60% for S. pneumoniae in transwell or mixed co-cultures, respectively).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of pre-formed biofilm during time. Data are expressed as mean percentage in respect to the pre-treatment level ± standard deviation (n = 3). Black bars = pre-treatment level; grey bars = 24 h; white bars = 48 h; dashed bars = 72 h; ctrl = untreated; * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001

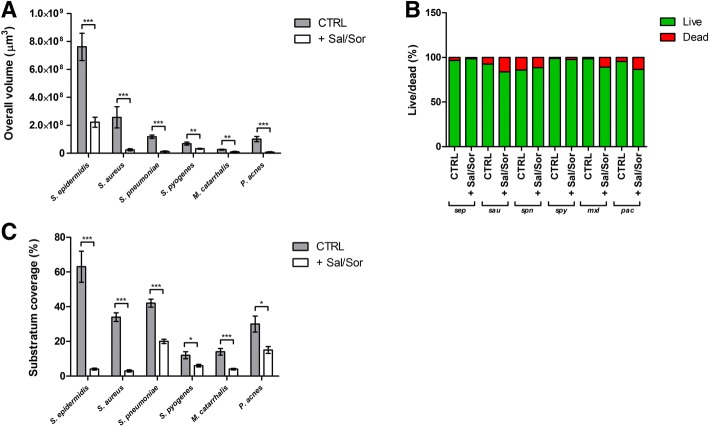

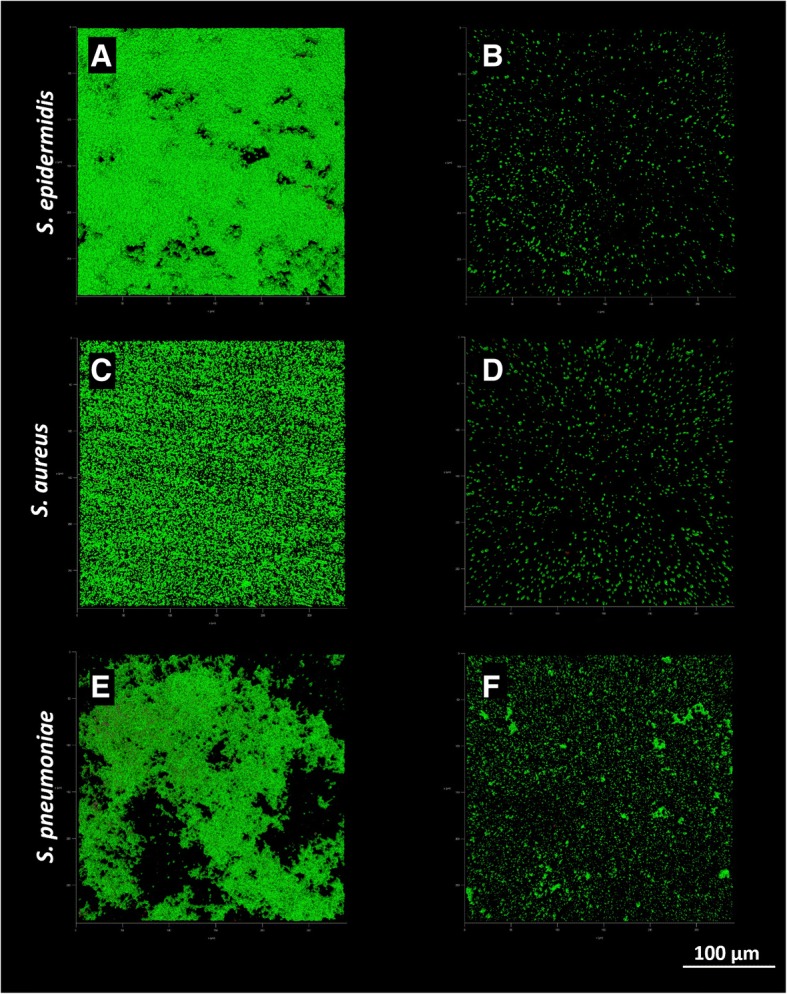

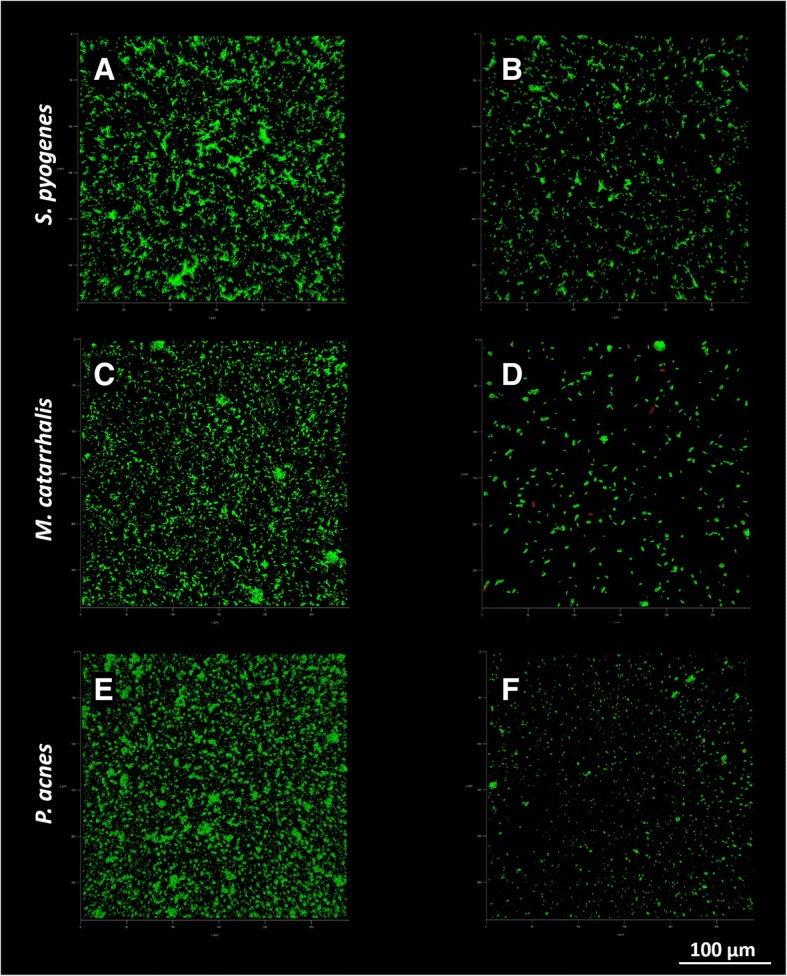

CLSM assay

The total biomass volume of samples incubated with S. oralis and S. salivarius in transwell experiments was significantly lower compared to control samples for all the tested strains (Fig. 4a). No differences in the live and dead cells ratio were found whit respect to treated and untreated biofilms (Fig. 4b). Substratum coverage was significantly lower for samples incubated with the probiotic strains than for control samples (Fig. 4c). As documented by CLSM images (Figs. 5 and 6), biofilms grown in presence of S. oralis and S. salivarius looked more scattered than control biofilms, especially those of S. epidermidis and S. pneumoniae.

Fig. 4.

Results of confocal scanning microscopy analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). CTRL = untreated samples; + Sal/Sor = samples incubated with a mixture of S. salivarius and S. oralis by means of transwell inserts; sep = S. epidermidis; sau = S. aureus; spn = S. pneumoniae; spy = S. pyogenes; mxl = M. catarrhalis; pac = P. acnes; * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001

Fig. 5.

Representative images of S. epidermidis, S. aureus and S. pneumoniae biofilms obtained by CSLM. Panels A, C and E show control biofilms, while panels B, D and F show biofilms co-cultured in presence of the probiotic strains by means of transwell inserts. Green = live cells; red = dead cells; 40× magnification

Fig. 6.

Representative images of S. pyogenes, M. catarrhalis and P. acnes biofilms obtained by CLSM. Panels A, C and E show control biofilms, while panels B, D and F show biofilms co-cultured in presence of the probiotic strains by means of transwell inserts. Green = live cells; red = dead cells; 40× magnification

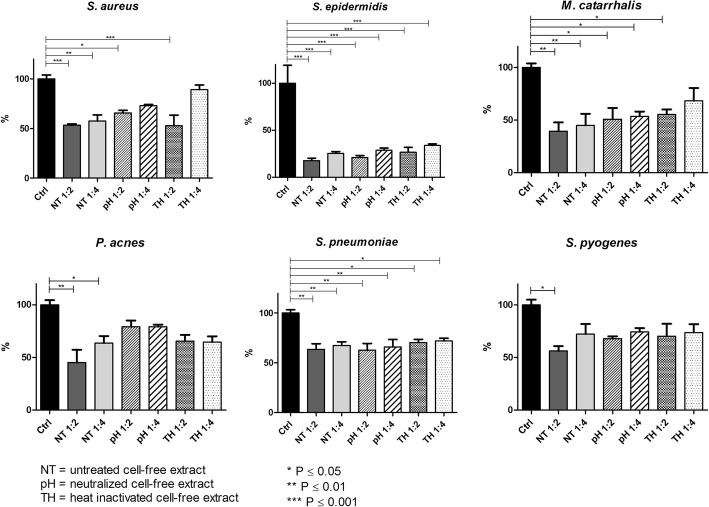

CFE influence on biofilm formation

CFE had a significant inhibitory effect on all the tested strains with respect to the control biofilm growth, even if a general slight concentration-dependent effect was noticed (Fig. 7). All the other strains showed significant biofilm biomass reductions with all the formulations tested (45–50% and 41–51% for S. aureus, 49–77% for M. catarrhalis, 40–80% for P. acnes, 26–45% and 29–40% for S. pneumoniae, ½ and ¼ v/v respectively) with S. epidermidis being the most affected (78–86%). Differently, S. pyogenes was more recalcitrant to CFE addiction than the other tested species, with a significant reduction in the presence of higher amounts of CFE (CFE ½ v/v 35–49%). When CFEs were treated to neutralize the pH or heated at 100 °C to inactivate thermolabile molecules, a mild impairment of CFE activity was observed, but no significant differences were detected with respect to untreated CFEs (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of biofilm formation by cell-free extracts. Data are expressed as mean percentage in respect to biofilm growth control in fresh BHI broth. Black bars = control; grey tone bars = untreated cell-free extract (NT); slanted lines bars = pH neutralized cell-free extract (pH); dotted bars = heat inactivated cell-free extract (TH). * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001

Discussion

Local administration of commensal probiotics as a sort of “bacteria-therapy”, able to interfere with disease-associated disease is gaining increasing interest, finding applications in many fields [27].

Probiotics own different mechanisms that interfere with the activity of pathogenic bacteria, including: the production of antagonistic substances (e.g., bacteriocins, fatty acids, hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid), generation of environment conditions unfavorable for pathogens (e.g., competition for nutrients or pH alteration) and the competitive adhesion to human tissues preventing the colonization by harmful bacteria. Among bacterial species recently recognize as probiotic, S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a isolated from the rhinopharynx of healthy children are suggestive strains of a healthy flora. S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a are administered in a ratio of 98:2 by means of a nasal spray are present, with the aim of preventing ear, nose and throat diseases. The abundance of S. salivarius in the solution is due to its primary and predominant presence in the upper respiratory tract surfaces of humans and because its non-pathogenic behavior in healthy individuals [28]. In particular, the strain 24SMB was isolated in 2012 and selected as a promising probiotic due to the absence of virulence traits and antibiotic resistance genes and its ability to inhibit S. pneumoniae growth [21]. Santagati et al. demonstrated its safety and tolerability, and its capability to colonize the rhinopharynx when administrated as a nasal spray [22].

Conversely, S. oralis 89a was isolated from a recalcitrant healthy child during a tonsillitis outbreak and it was found to be able to inhibit the growth of group A streptococci in vitro [29]. Since then, this strain has been used in in vitro and in vivo studies to evaluate its clinical effects on streptococcal tonsillitis and otitis media [19, 20, 30–32]. The whole genome of this strain was recently sequenced, identifying the gene encoding for the bacteriocin Colicin V and for tolerance to Colicin E2 [14].

As a preliminary step, the reciprocal interaction between S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a was assessed. Using the transwell device, the two strains were physically separated by a membrane that permitted only the passage of diffusible molecules form one compartment to the other. In both cases, a significant increase in biofilm formation was observed, suggesting a possible positive synergistic effect between the two strains. Furthermore, when S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a were simultaneously cultured in direct contact, the resulting biofilm appeared to be like the sum of the two strains grown individually. Unfortunately, the contribution of a single strains in mixed biofilms was not evaluated, being the used staining technique not species-specific, representing a limit of the study.

Then, the anti-biofilm activity resulting from the combination of S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a against pathogens of the upper airways was investigated. In particular, the anti-biofilm activity was tested against S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes and M. catarrhalis being the most common bacterial pathogens causing acute otitis media and bacterial pharyngotonsillitis [33, 34]. Moreover, the anti-biofilm effect was assessed on S. aureus, involved in 50% of recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis [35], and coagulase negative staphylococci and anaerobes, including P. acnes [36].

Biofilms are comprised of microorganisms enclosed in a hydrated self- produced polymeric matrix attached to a solid surface. They represent an important cause of chronic infectious diseases of the upper airways, including recurrent middle ear diseases, chronic rhinosinusitis and recurrent pharyngotonsillitis [2], but also teeth or in implant-associated infections. Biofilm-related infections are often resistant to antibiotic therapy, posing serious concerns about the infection control. Frequent antibiotic intakes may have deleterious effects due to the depletion of the commensal microbiome and the subsequent colonization by microorganisms that are less susceptible to the prescribed antibiotics [37]. In this context, the use of probiotics able to disperse pathogens biofilm may be therapeutically beneficial and may offer a valid alternative or a coadjuvant treatment to conventional antimicrobials.

With the aim to test the aforementioned hypothesis, in the present study, co-culture experiments by means of the direct or indirect culture of the probiotic strains with the respiratory tract pathogens was performed. The combination of probiotics was able to both inhibit the biofilm development and to disperse the already established biofilms of all the tested pathogens with the exception of S. pyogenes. This behavior is not surprising; the inhibitory activity of S. salivarius 24SMB against S. pyogenes depends on the choice of the growth media [21]. Indeed, Santagati and co-workers described how S. salivarius was not able to inhibit S. pyogenes in Todd Hewitt broth supplemented with blood, while an increase in the inhibitory activity was observed on Columbia blood agar. In our experimental setting, the lack of activity against S. pyogenes could also be explained by the lack of supplementation of yeast extract, glucose or calcium salts in the growth medium, which are necessary supplement for an optimal production of bacteriocins [38, 39].

A more detailed investigation was carried out by CLSM analysis, which considered additional outcome variables as live/dead cells ratio and percentage of substratum coverage. Specifically, the total biomass volume was significantly lower when the tested pathogens were incubated with probiotics compared to that of controls. Differently to what observed in the spectrophotometric assay, the higher sensitivity of the CLSM analysis allowed to appreciate a significant biomass reduction also for S. pyogenes. Indeed, while the spectrophotometric assay allows the semi-quantitative measurement of the air-dried biofilm biomass, CLSM gives the possibility to collect three-dimensional images of hydrated biological structures without fixation [40]. This non-destructive technique has radically transformed optical imaging in biology and microbiology, providing a useful tool for the examination of the structure of biofilms.

Concerning the live to dead cells ratio, no differences between treated and untreated samples were found, indicating a prevalent inhibitory effect rather than a potential bactericidal activity of the probiotic strains. On the contrary, substratum coverage was significantly lower in treated biofilms, with particular regard to that of S. epidermidis and S. aureus, which appeared more scattered than controls.

Recent studies shown that chemical interactions through secretion of molecules by different microbial species may affect spatial biofilm structure, regulating both its formation and dispersion [41–43]. Recently, Santagati et al. described the presence of a blpU-like bacteriocine cassette in the genome of S. salivarius 24SMB, which has been shown to mediate intra- and interspecies competition with inhibitory activity against S. pyogenes and S. pneumoniae and also to provide competitive advantage in colonization in vivo [15, 44]. However, no other genes responsible for production of bacteriocine (i.e. salivaricins, commonly produced by other S. salivarius strains) were identified throughout the genome [15]. Similarly, S. oralis 89a possess a locus for the production of a Colicin V, a proteolitically processed peptide antibiotic, which kills sensitive cells by disrupting membrane potential [45]. Interestingly, S. oralis 89a is characterized by the presence of luxS gene, responsible for the production of the quorum-sensing molecule AI-2, involved in cell-to-cell communication and able to influence the expression of virulence factors, motility and biofilm formation [46]. In particular, controlled concentrations of AI-2 are able to promote mutualistic biofilm formation and to influence structure and composition of other commensal streptococcal species biofilm [47, 48]. Unluckily, the genome sequence of S. salivarius 24SMB is not available in public databases and no information on the presence of quorum-sensing clusters involved in biofilm formation and regulation (e.g., Rgg transcriptional regulators family) are available.

Nonetheless, signaling is restricted only to those species with appropriate receptors, suggesting that other kind of unspecific interactions may play an important role in determining biofilm spatial structure [49]. For example, metabolic end products like lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide produced by streptococci,

can act with a broader spectrum by cause acid and oxidative stress, respectively. As expected, the presence of S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a in the co-cultures slightly lowered the pH in all the cases except for S. pyogenes and S. pneumoniae (data shown in Additional file 1). Since the inhibitory activity was observed also for the two streptococci, it can be supposed that alteration in pH is not the only mechanism of action, but other specific interactions might occur.

Finally, a high reduction of biofilm biomass in transwell co-cultures was observed. This event might suggest that the anti-biofilm activity of the probiotic mixture is mediated by diffusible molecules secreted by the probiotic strains, rather than depending on a mechanism requiring physical contact. This was confirmed by supplementation of the cell-free extract to the medium, displaying an effect comparable to that observed in the transwell co-culture. In the attempt to elucidate the nature of the inhibition, the cell-free extracts were neutralized to a pH of 7.0, to evaluate the contribution of the acidic environment resulting from the streptococcal fermentation or were heated, to eliminate all the thermolabile secreted molecules. Even though, both the treatments did not completely impair the inhibitory effect of the cell-free extract, indicating a likely multifactorial and strain-specific strategy. Furthermore, the contribution to biofilm formation between pathogenic and probiotic strains in mixed species biofilms was not discriminated. Indeed, mixed biofilms were not analyzed by confocal microscopy, because of the lack of species-specific dyes able to differentiate the presence of different microbes. Stains able to discriminate among different bacteria should be used in future studies in order to investigate the role of probiotic strains in the biofilm production by pathogenic bacteria.

As the goal of the probiotics tested in this study is to create a barrier against pathogens, an interesting issue would be to investigate if pathogens are able to invade and establish within pre-existing probiotic biofilms.

Conclusions

In this preliminary study, we demonstrated the capability of S. salivarius and S. oralis to interfere with the biofilm formation capacity of the upper airways pathogens and disperse their pre-formed biofilms. The nature of inhibition seems to be multifactorial, involving both specific and unspecific mechanisms. However, additional studies are required to get further insights into the mechanisms underlying these interactions at molecular level.

Additional files

Broth pH after 72 h. Culture medium pH measurement after 72 h of growth. (DOCX 12 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Consorzio Milano Ricerche (Milan, Italy). The sponsor was not involved in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CLSM

Confocal laser scan microscopy

- URTIs

Upper respiratory tract infections

Authors’ contributions

AB, LD and MG conceived and designed the experiments. AB, RDG, MB and MT performed the experiments. AB, RDG, MB, MT and EDV analysed the data. AB prepared figures and graphs and wrote the manuscript. LD, EDV, MG revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received approval by the IRB of Istituto Ortopedico Galeazzi, whereas our Institution did not require specific Ethical Committee approval for in vitro studies performed on materials collected during diagnostic procedures, all patients at the hospital admission were informed on the possible use of clinical isolates routinely obtained for further in vitro research purposes and signed a written consent for the use.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alessandro Bidossi, Email: Ale.bidossi@gmail.com.

Roberta De Grandi, Email: Roberta.degrandi@grupposandonato.it.

Marco Toscano, Email: Toscano.marco1@gmail.com.

Marta Bottagisio, Email: Marta.bottagisio@grupposandonato.it.

Elena De Vecchi, Email: Elena.devecchi@grupposandonato.it.

Matteo Gelardi, Email: gelardim@inwind.it.

Lorenzo Drago, Email: Lorenzo.drago@unimi.it.

References

- 1.Morris DP. Bacterial biofilm in upper respiratory tract infections. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2007;9:186–192. doi: 10.1007/s11908-007-0030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nazzari E, Torretta S, Pignataro L, Marchisio P, Esposito S. Role of biofilm in children with recurrent upper respiratory tract infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:421–429. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danielsen KA, Eskeland O, Fridrich-Aas K, Orszagh VC, Bachmann-Harildstad G, Burum-Auensen E. Bacterial biofilms in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: a confocal scanning laser microscopy study. Rhinology. 2014;52:150–155. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2015.1092169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P. Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1034–1043. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaguchi T, Dwidar M, Byun CK, Leung B, Lee S, Cho YK, et al. Aqueous two-phase system-derived biofilms for bacterial interaction studies. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:2655–2661. doi: 10.1021/bm300500y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Xiang Q, Yang T, Li L, Yang J, Li H, et al. Autoinducer-2 of Streptococcus mitis as a target molecule to inhibit pathogenic multi-species biofilm formation in vitro and in an endotracheal intubation rat model. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:e88. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goers L, Freemont P, Polizzi KM. Co-culture systems and technologies: taking synthetic biology to the next level. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11. 10.1098/rsif.2014.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Bernstein JM, Sagahtaheri-Altaie S, Dryja DM, Wactawski-Wende J. Bacterial interference in nasopharyngeal bacterial flora of otitis-prone and non-otitis-prone children. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. 1994;48:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujimori I, Hisamatsu K, Kikushima K, Goto R, Murakami Y, Yamada T. The nasopharyngeal bacterial flora in children with otitis media with effusion. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;253:260–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00171139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.FAO/WHO Expert Consultation . Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlsson J, Grahnen H, Jonsson G, Wikner S. Early establishment of Streptococcus salivarius in the mouth of infants. J Dent Res. 1970;49:415–418. doi: 10.1177/00220345700490023601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazor CE, Mitchell PM, Lee AM, Stokes LN, Loesche WJ, Dewhirst FE, et al. Diversity of bacterial populations on the tongue dorsa of patients with halitosis and healthy patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:558–563. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.558-563.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidjabat HE. Grahn Håkansson E, and Cervin ADraft genome sequence of the oral commensal Streptococcus oralis 89a with interference activity against respiratory pathogens. Genome Announc. 2016;4:e01546. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01546-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santagati M, Scillato M, Stefani S. Genetic organization of Streptococcus salivarius 24SMBc blp-like bacteriocin locus. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2018;1(10):238–247. doi: 10.2741/s512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jimenez JC, Federle MJ. Quorum sensing in group A Streptococcus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;12(4):127. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiedler T, Riani C, Koczan D, Standar K, Kreikemeyer B, Podbielski A. Protective mechanisms of respiratory tract streptococci against Streptococcus pyogenes biofilm formation and epithelial cell infection. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:1265–1276. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03350-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Helmerhorst EJ, Leone CW, Troxler RF, Yaskell T, Haffajee AD, et al. Identification of early microbial colonizers in human dental biofilm. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:1311–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roos K, Håkansson EG, Holm S. Effect of recolonisation with “interfering” alpha streptococci on recurrences of acute and secretory otitis media in children: randomised placebo-controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:210–212. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7280.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skovbjerg S, Roos K, Holm SE, Grahn Håkansson E, Nowrouzian F, Ivarsson M, et al. Spray bacteriotherapy decreases middle ear fluid in children with secretory otitis media. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:92–98. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.137414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santagati M, Scillato M, Patanè F, Aiello C, Stefani S. Bacteriocin-producing oral streptococci and inhibition of respiratory pathogens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;65:23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santagati M, Scillato M, Muscaridola N, Metoldo V, La Mantia I, Stefani S. Colonization, safety, and tolerability study of the Streptococcus salivarius 24SMBc nasal spray for its application in upper respiratory tract infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:2075–2080. doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchisio P, Santagati M, Scillato M, Baggi E, Fattizzo M, Rosazza C, et al. Streptococcus salivarius 24SMB administered by nasal spray for the prevention of acute otitis media in otitis-prone children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:2377–2383. doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2491-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drago L, Vassena C, Saibene AM, Del Fabbro M, Felisati G. A case of coinfection in a chronic maxillary sinusitis of odontogenic origin: identification of Dialister pneumosintes. J Endod. 2013;39:1084–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen GD, Simpson WA, Younger JJ, Baddour LM, Barrett FF, Melton DM, et al. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: a quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:996–1006. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.6.996-1006.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Standar K, Kreikemeyer B, Redanz S, Münter WL, Laue M, Podbielski A. Setup of an in vitro test system for basic studies on biofilm behavior of mixed-species cultures with dental and periodontal pathogens. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh VP, Sharma J, Babu S. Rizwanulla, Singla a. role of probiotics in health and disease: a review. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63(2):253–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wescombe PA, Heng NC, Burton JP, Chilcott CN, Tagg JR. Streptococcal bacteriocins and the case for Streptococcus salivarius as model oral probiotics. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:819–835. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grahn E, Holm SE. Bacterial interference in the throat flora during a streptococcal tonsillitis outbreak in an apartment house area. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiologie Hyg. 1983;256:72–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roos K, Grahn E, Lind L, Holm S. Treatment of recurrent streptococcal tonsillitis by recolonization with alpha-streptococci. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:318–319. doi: 10.1007/BF01963463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roos K, Grahn E, Holm SE, Johansson H, Lind L. Interfering alpha-streptococci as a protection against recurrent streptococcal tonsillitis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1993;25:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(93)90047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rods K, Holm SE, Grahn-Håkansson E, Lagergren L. Recolonization with selected alpha-streptococci for prophylaxis of recurrent streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis - a randomized placebo-controlled multicenter study. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:459–462. doi: 10.3109/00365549609037940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Worrall G. Acute otitis media. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:2147–2148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray RC, Chennupati SK. Chronic streptococcal and non streptococcal pharyngitis. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2012;12:281–285. doi: 10.2174/187152612801319311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foreman A, Boase S, Psaltis A, Wormald PJ. Role of bacterial and fungal biofilms in chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2012;12:127–135. doi: 10.1007/s11882-012-0246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stressmann FA, Rogers GB, Chan SW, Howarth PH, Harries PG, Bruce KD, et al. Characterization of bacterial community diversity in chronic rhinosinusitis infections using novel culture-independent techniques. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:e133ee140. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu CM, Soldanova K, Nordstrom L, Dwan MG, Moss OL, Contente-Cuomo TL, et al. Medical therapy reduces microbiota diversity and evenness in surgically recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3:775–781. doi: 10.1002/alr.21195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley MA, Chavan MA. Bacteriocin: ecology and evolution. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Therdtatha P, Tandumrongpong C, Pilasombut K, Matsusaki H, Keawsompong S, Nitisinprasert S. Characterization of antimicrobial substance from lactobacillus salivarius KL-D4 and its application as biopreservative for creamy filling. Springerplus. 2016;5:e1060. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2693-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khajotia SS, Smart KH, Pilula M, Thompson DM. Concurrent quantification of cellular and extracellular components of biofilms. J Vis Exp. 2013;10:e50639. doi: 10.3791/50639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davies DG, Marques CN. A fatty acid messenger is responsible for inducing dispersion in microbial biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1393–1403. doi: 10.1128/JB.01214-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwase T, Uehara Y, Shinji H, Tajima A, Seo H, Takada K, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis Esp inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and nasal colonization. Nature. 2010;465:346–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Armbruster CE, Hong W, Pang B, Weimer KE, Juneau RA, Turner J, et al. Indirect pathogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis in polymicrobial otitis media occurs via interspecies quorum signaling. mBio. 2014;1:e00102. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00102-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dawid S, Roche AM, Weiser JN. The blp bacteriocins of Streptococcus pneumoniae mediate intraspecies competition both in vitro and in vivo. Infect Immun. 2007;75(1):443–451. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01775-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang CC, Konisky J. Colicin V-treated Escherichia coli does not generate membrane potential. J Bacteriol. 1987;158(2):757–759. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.757-759.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pereira CS, Thompson JA, Xavier KB. AI-2-mediated signalling in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37(2):156–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cuadra-Saenz G, Rao DL, Underwood AJ, Belapure SA, Campagna SR, Sun Z, et al. Autoinducer-2 influences interactions amongst pioneer colonizing streptococci in oral biofilms. Microbiology. 2012;158(Pt 7):1783–1795. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.057182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rickard AH, Palmer RJ, Jr, Blehert DS, Campagna SR, Semmelhack MF, Egland PG, et al. Autoinducer 2: a concentration-dependent signal for mutualistic bacterial biofilm growth. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60(6):1446–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stacy A, McNally L, Darch SE, Brown SP, Whiteley M. The biogeography of polymicrobial infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:93–105. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Broth pH after 72 h. Culture medium pH measurement after 72 h of growth. (DOCX 12 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.