Abstract

Background

High incidence and morbidity rates are found among adolescents with social anxiety disorder, a severe and harmful form of social phobia. Extensive research has been conducted to uncover the underlying psychological factors associated with the development and continuation of this disorder. Previous research has focused on single individual difference variables such as personality, cognition, or emotion; thus, the effect of an individual’s full psychological profile on social anxiety has rarely been studied. Psychological suzhi is a comprehensive psychological quality that has been promoted in Chinese quality-oriented education. This research aimed to explore how psychological suzhi affects Chinese adolescents’ social anxiety.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey study was carried out among 1459 middle school students (683 boys and 776 girls) from various middle schools in seven provinces of China. Psychological suzhi, self-esteem, sense of security, and social anxiety were measured via four self-reported questionnaires: the Brief Psychological Suzhi Questionnaire for middle school students, the Chinese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, the Security Questionnaire, and the Social Avoidance and Distress Scale.

Results

Analyses showed that psychological suzhi is positively related to self-esteem and sense of security, and it is negatively correlated with social anxiety. The results also revealed that self-esteem partially mediates the relationship between adolescents’ psychological suzhi and social anxiety, with self-esteem and sense of security serving as chain mediators in the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety.

Conclusions

Results highlight that psychological suzhi is a protective factor against social anxiety. It can directly protect adolescents from social anxiety, and it also can protect them through affecting their self-esteem and sense of security. These results are discussed from the viewpoints of school leaders, psychology teachers, and school counsellors, who provide support to students to improve their social functioning within the school context. The findings of this study may provide new perspectives regarding the prevention and treatment of social anxiety.

Keywords: Adolescents, Psychological suzhi, Self-esteem, Sense of security, Social anxiety

Background

Psychological suzhi is an endogenous Chinese psychological concept that has been promoted within the background of Chinese quality-oriented education [1] and has subsequently roused the interest of many Chinese psychologists [2]. The concept of psychological suzhi became more widely known following the publication of an internationally authoritative reference book, The Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools [3], wherein it was recognised as a concept of positive psychology. Psychological suzhi is defined as a fundamental, stable, and implicit mental quality that forms under the influence of inborn conditions, the environment, and one’s education. It is closely and positively associated with an individuals’ adaptive, developmental, and creative behaviors [1, 4]. Psychological suzhi is a comprehensive mental quality that comprises three elements: cognitive quality, individuality, and adaptability. Cognitive quality is the most fundamental component, which directly involves individuals’ cognitive process. Individuality is reflected through one’s action towards that reality and plays a motivating and moderating function during cognition. Finally, adaptability refers to the ability to make oneself be in harmony with the environment; it is the functional component of psychological suzhi that reflects the other two components’ states [4]. It is a weighty component of students’ quality, which Chinese quality education is designed to cultivate. To explore the positive function of this important quality component, a series of studies concerning the relationship between psychological suzhi and mental health have been conducted and they have found that psychological suzhi negatively predicts depression [5]. However, it has been positively associated with life satisfaction [6], subjective well-being [7], and positive emotions [8]. Based on the results of the above studies, researchers have constructed a psychological suzhi and mental health relationship model, and proposed that psychological suzhi is an endogenous factor that affects mental health [9].

Social anxiety is a negative indicator of mental health. It begins at puberty and is most common among teenagers [10]. Related research has also revealed that many members of this demographic group have at least moderate impairment in their socio-emotional functioning [11], academic achievement [12], quality of life [13], areas of friendship [14], and even emerging adult relationship quality [15]. These impairments may result in increased likelihood of engaging in cigarette smoking [16] and drinking alcohol [17]. Given the high prevalence of social anxiety and its harmful nature among middle school students, extensive research has been conducted to uncover the underlying psychological factors associated with the development and maintenance of this condition. Such research has revealed that personality [18]; irrational social, cognitive [19], and behavioural patterns [20, 21]; and information processing biases [22] are important factors that can influence the development of social anxiety. Further, Chinese adolescents’ psychological suzhi can also influence their social anxiety levels. Liu et al. [23] discovered that psychological suzhi was a protective factor against social anxiety. However, a thorough examination of it as a comprehensive psychological quality—i.e. how it protects individual against social anxiety—was lacking. Therefore, in order to further reveal the relationship between psychological suzhi and mental health, and to reveal how multiple variables interact to influence the symptoms of social anxiety, it is necessary to explore how the mechanism of psychological suzhi affects social anxiety. Understanding this mechanism would provide a basis for the effective prevention and scientific control of social anxiety.

Cognitive and behavioural theories of social anxiety emphasise the influence of low self-evaluation on individuals’ development of social anxiety [24]. Indeed, some empirical studies have verified the negative relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety [25], while others have determined that psychological suzhi is a powerful motivator of self-esteem [7, 23]. Thus, individuals with high psychological suzhi have high levels of self-esteem and, in turn, low levels of social anxiety. Therefore, self-esteem may play a mediating role between psychological suzhi and social anxiety.

Sense of security is defined as an individual’s physical or mental feelings concerning the level of danger and risk in their surroundings, as well as their sense of power or powerlessness to address any such dangers. It is mainly manifested in terms of interpersonal security and feelings of control [26]. Sense of security is one of the most important determinants of mental health and is considered a basic human need [27]. Further, empirical research has shown that it is an important factor in the development of social anxiety [28]. However, with regard to the relationship between self-esteem and sense of security, there is controversy concerning the direction of specific predictions. Some researchers, in accordance with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, have proposed that security is a basic need; only when security needs are met can an individual work toward the fulfilment of needed self-esteem. However, other researchers insist that individuals with low self-esteem are unable to develop feelings of security because they lack confidence, and that high self-esteem is more likely to produce a sense of security [29]. Although we believe that there are merits to both arguments in the above debate, one definition of sense of security must be chosen in order to clarify its relationship with self-esteem. Given the measures used in the current study, we adopt the latter viewpoint in terms of our understanding and definition of this construct. Therefore, this study assumes that self-esteem predicts sense of security, which, in turn, predicts social anxiety. In other words, sense of security is assumed to act as a mediating variable between self-esteem and social anxiety. In this context, psychological suzhi positively predicts self-esteem, which affects an individuals’ sense of security, and sense of security negatively predicts social anxiety. Thus, self-esteem and sense of security may serve as chain mediators in the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety.

Although there is currently no research demonstrating the close relationship between psychological suzhi and sense of security, some explanations concerning this relationship have been offered in other studies. Zhang [4] proposed that personality elements that have adaptive and health functions are the basic components of psychological suzhi, and that personality is also closely related to psychological suzhi. Meanwhile, Xie et al. [30] found that psychological suzhi is positively related to extraversion and negatively related to neuroticism. Research on the relationship between personality and sense of security has also indicated that personality can predict sense of security; specifically, sense of security is positively and negatively predicted by extraversion and neuroticism, respectively [31]. In this context, psychological suzhi may be positively correlated with sense of security, and sense of security may play a mediating role in the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety.

Based on the relationships described above, we can know that: first, previous studies on the factors that influence social anxiety have generally examined one or several separate individual difference variables such as personality, cognition, or emotion [32]. The effect of an individual’s full psychological profile on social anxiety has rarely been studied. Consequently, in this study we investigated the influence of the Chinese comprehensive psychological variables, psychological suzhi, on social anxiety to reveal the factors influencing social anxiety among Chinese adolescents. Second, the intrinsic mechanism of this relationship was unknown; therefore, based on the cognitive and behavioural theories of social anxiety and the theory of the sense of security, we investigated the roles of self-esteem and a sense of security as mediators in the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety. This research can provide valuable references for prevention of social anxiety and its related interventions.

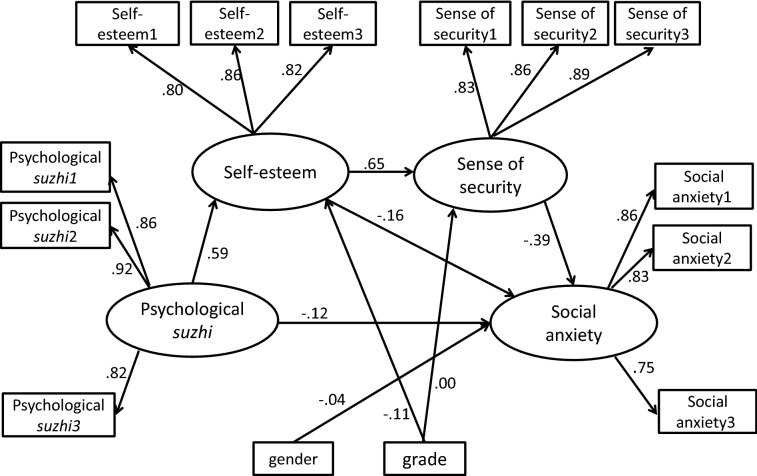

Our specific hypotheses were as follows: (1) psychological suzhi is positively related to self-esteem and sense of security, but it is negatively related to social anxiety; and (2) self-esteem and sense of security mediate the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety. A detailed model of the hypothesised mediating role of self-esteem and sense of security in the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Model of the hypothesised mediating roles of self-esteem and sense of security in the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety

Methods

Participants and sample

The current study is part of the national, normative measurement of psychological suzhi among Chinese middle school students. This national sampling was conducted from October to December 2016. The whole group stratified random sampling method was used to extract the subjects. The inclusion criteria were: (1) being a full-time, middle school student; and (2) being between the ages of 11 and 18 years. Because this was a normative measurement of middle school students’ psychological suzhi, there were no exclusion criteria. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the author’s institution. Written consent was obtained from the heads of participating middle schools and the participants’ parents, and the student participants provided their oral assent.

In this study, 34 classes of students from junior and senior middle schools in the Beijing, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Henan, Jiangxi, Sichuan, and Chongqing provinces were selected to complete a self-administered questionnaire. A total of 1587 students were approached to participate in this study. Under the guidance of a trained investigator, the participants were given 40 min to complete a series of self-report questionnaires during normal class time. They returned their anonymous questionnaires to the researcher upon completion. After completing the questionnaire, each participant received 5 RMB as compensation. Ultimately, 1459 valid questionnaires were recovered, with an effective recovery rate of 91.9%. The participants were representative of the total sample in terms of age, gender, and grade.

Measures

Psychological suzhi

To measure psychological suzhi, we used the Brief Psychological Suzhi Questionnaire for middle school students (BPSQM) [33], which is specifically designed to measure middle school students’ psychological suzhi in a Chinese environment. It contains 24 items and assesses three dimensions of psychological suzhi: cognitive quality, individuality, and adaptability. The items are presented on a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (not at all true for me) to 5 (extremely true for me). Consequently, overall scores range from 24 to 120, with higher scores reflecting higher psychological suzhi. The brief BPSQM was validated using a large sample of Chinese students (N = 2549), and its psychometric properties were found to support a bi-factor structure. Additionally, the total scale was found to have excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .91), and the subscales were all determined to have acceptable internal consistency (α > .76) [33]. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was .94 and ranged between .84 and .87 for the three subscales.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was assessed using the Chinese version of the Self-Esteem Scale (SES) [34]. The SES contains 10 items presented using a 4-point Likert scale for which the responses range from 1 (not at all true for me) to 4 (extremely true for me). Overall scores ranged between 10 and 40. The Chinese version of the SES has been widely used among the Chinese population and has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid measure. Based on the findings of a previous study, we chose to omit one item (item 8), as it has been found to have low factor loadings within a Chinese context [35]. Consequently, Cronbach’s alpha for the final scale was .88 in the current study.

Sense of security

Sense of security was assessed using the Security Questionnaire (SQ) [26], which contains 16 items divided into two subscales: interpersonal security (eight items) and certainty in control (eight items). The interpersonal security subscale assesses feelings of security during interpersonal communication, while the certainty in control subscale assesses sense of control over life and life uncertainty. Items are presented on a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (extremely true for me) to 5 (not at all true for me). Further, overall scores range from 16 to 90, with higher scores reflecting a higher sense of security. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was .88 for the total scale, .78 for the interpersonal security subscale, and .83 for the certainty in control subscale.

Social anxiety

Social anxiety was assessed using the Social Avoidance and Distress Scale (SADS) [36]. The SADS contains 28 items that comprise two subscales: social avoidance (14 items) and social distress (14 items). The social avoidance subscale assesses avoidance behaviour and the desire to avoid situations that involve interactions, whereas the social distress subscale assesses the degree of negative emotions experienced during social interactions. Participants provide a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer to each item. The Chinese version of the SADS has been found to exhibit acceptable reliability and validity in adolescent studies [37]. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .87 for the total scale, .77 for the social avoidance subscale, and .80 for the social distress subscale.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS 19.0 and MPlus 7.0 [38]. The first purpose of this study was to investigate the correlation between psychological suzhi, self-esteem, sense of security, and social anxiety. To this end, descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlational analyses were conducted using SPSS 19.0. The second purpose was to examine the mediation model, so a path analysis using structural equation modelling was used to test the direct and indirect effects of psychological suzhi on social anxiety. The model included four latent variables (psychological suzhi, self-esteem, sense of security, and social anxiety) that were made up of 12 parcels to reduce model complexity [39, 40]; the average scores for each parcel were used as indicators in the model. The model included a direct effect of psychological suzhi on social anxiety and three indirect effects through self-esteem and sense of security: psychological suzhi → self-esteem → social anxiety; psychological suzhi → sense of security → social anxiety; and psychological suzhi → self-esteem → sense of security → social anxiety. Missing data were estimated using full information maximum likelihood estimation, and robust maximum likelihood estimation was used to account for non-normality. Meanwhile, standardized regression coefficients (β) were presented to quantify the strength of association between pairs of variables. The indirect effects of the model were checked using bootstrapping procedures [39], and model fit was evaluated using several common fit indices: CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR. The following were considered indices of good fit: CFI > .90, TLI > .90, RMSEA < .08, and SRMR < .08 [41].

Results

Sample descriptives

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for the sample. The 1459 included participants had a mean age of 14.83 years (SD = 1.83 years). Among them, 684 (46.9%) were boys, and 775 (53.1%) were girls. Concerning grade, 241 (16.5%), 216 (14.8%), 218 (14.9%), 260 (17.8%), 285 (19.5%), and 239 (16.4%) were in seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth grades, respectively. Regarding province, 218 (14.9%), 104 (7.1%), 98 (6.7%), 172 (11.8%), 580 (39.8%), 105 (7.2%), and 182 (12.5%) were from Beijing, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Henan, Jiangxi, Shanxi, and Sichuan, respectively. Moreover, the participants were almost entirely of Han ethnicity (98.9%), with the remainder being from ethnic minorities.

Table 1.

Sample descriptive statistics

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 684 | 46.9 |

| Female | 775 | 53.1 | |

| Grade | 7th | 241 | 16.5 |

| 8th | 216 | 14.8 | |

| 9th | 218 | 14.9 | |

| 10th | 260 | 17.8 | |

| 11th | 285 | 19.5 | |

| 12th | 239 | 16.4 | |

| Ethnicity | Han ethnicity | 1443 | 98.9 |

| Ethnic minorities | 16 | 1.1 | |

| Province | Beijing | 218 | 14.9 |

| Zhejiang | 104 | 7.1 | |

| Guangdong | 98 | 6.7 | |

| Henan | 172 | 11.8 | |

| Jiangxu | 580 | 39.8 | |

| Shanxi | 105 | 7.2 | |

| Sichuan | 182 | 12.5 |

Preliminary analyses

We determined the means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations of all the variables, as shown in Table 1. Results indicated that psychological suzhi was positively correlated with self-esteem and sense of security (r = .29–.52, p < .01), and it was negatively correlated with social anxiety (r = − .34, p < .01). Analyses of the potential covariates indicated that gender was positively related to sense of security and social anxiety (r = .09–.14, p < .01), and it was negatively related to self-esteem (r = − .12, p < .01). In addition, grade was positively related to sense of security (r = .06, p < .01) and negatively related to psychological suzhi (r = − .15, p < .01). Thus, gender and grade were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Measurement model

A confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the fit of the measurement model. Here, the abovementioned four latent variables (psychological suzhi, self-esteem, sense of security, and social anxiety), with 12 parcels as indicators, comprised the measurement model. Results indicated that the data fit the model well: χ2 (47) = 272.591; CFI = .963; TLI = .947; RMSEA = .057 (90% CI [.051, .064]); SRMR = .036. Further, all factor loadings on the latent variables were significant (p < .01), indicating that the latent factors were well represented by their respective indicators.

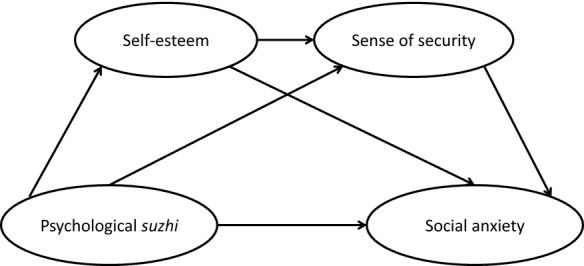

Structural model

As shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2, after controlling for gender and grade, the structural model examining the relationship between psychological suzhi, self-esteem, sense of security, and social anxiety fit the data well: ⎟2(63) = 536.334, p < .001; CFI = .956; TLI = .937; RMSEA = .072 (90% CI = [.066, .077]); SRMR = .040. Analyses of the total indirect effects indicated that self-esteem and sense of security partially mediated the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety (®= − .229, SE = .025, p < .001, 90% CI [− .091, − .016]). Meanwhile, when examined separately, two indirect paths were significant: psychological suzhi → self-esteem → social anxiety (®= − .095, SE = .027, p < .001, 90% CI [− .047, − .018]) and psychological suzhi → self-esteem → sense of security → social anxiety (® = − .151, SE = .018, p < .001, 90% CI [− .061, − .039]). However, the mediating effects of sense of security on the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety were not significant. Consequently, the total indirect effect of self-esteem and sense of security on the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety was .656. In addition, self-esteem was found to mediate the relationship between psychological suzhi and sense of security (®= .381, SE = .031, p < .001, 90% CI [.350, .474]), and sense of security was found to mediate the relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety (®= − .256, SE = .027, p < .001, 90% CI [− .117, − .081]).

Fig. 2.

Structural equation model of the proposed relationships between psychological suzhi, self-esteem, sense of security and social anxiety

Table 2.

Standardised indirect effects of psychological suzhi on social anxiety

| Indirect effect | ® | SE | p | 90% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suzhi → SA | − .229 | .025 | .000 | − .091, − .016 |

| Suzhi → SS → SA | − .394 × .046 = .018 | .016 | .025 | − .003, .014 |

| Suzhi → SE → SA | − .194 × .438 = − .095 − .091 | .027 | .000 | − .047, − .018 |

| Suzhi → SE → SS → SA | − .39 × .586 × .649 = − .151 | .018 | .000 | − .061, − .039 |

Suzhi = psychological suzhi, SE = self-esteem, SS = sense of security, SA = social anxiety

Discussion

This study analysed the effects of psychological suzhi on social anxiety and extended the literature by investigating the potential mediating effects of self-esteem and sense of security in this relationship. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, we discovered that psychological suzhi is positively related to self-esteem and sense of security, and it is negatively related to social anxiety.

The finding that higher psychological suzhi predicts lower social anxiety is consistent with the results of previous research conducted with Chinese adolescents [23], and it indicated that adolescents’ psychological suzhi is an important protective factor for social anxiety. There are several possible explanations for this finding. First, the diathesis-stress model suggests that certain underlying vulnerabilities combined with stressful life events result in the development of mental disorders, whereas protective factors serve to mitigate the impact of stressful life events [42]. In this regard, as a positive psychological quality, psychological suzhi can effectively help teenagers relieve the pressure they experience during social interactions in their daily lives, which results in fewer psychological problems like anxiety and depression. Second, psychological suzhi predicts good peer relationships, as middle school students with high psychological suzhi can more effectively cope with stressful events because of their improved interpersonal communication skills and ability to adapt to various types of social environments [43]. Having these positive peer interactions can, in turn, prevent and alleviate social anxiety. This finding corroborates those of studies examining the association between psychological suzhi and mental health, which have found that psychological suzhi positively relates to mental health [44]. Thus, the current finding adds empirical support for the relationship model of psychological suzhi and mental health [45].

Further, the finding that psychological suzhi is positively correlated with self-esteem is also consistent with previous research [7, 23]. Psychological suzhi concerns a unification of the content of individual psychological and behavioural factors (cognitive, personality) with functional value (adaptive); thus, it constitutes the inner basis for the formation of various psychological functions and the improvement in behavioural efficiency. Moreover, it can improve individuals’ health and foster the development of more adaptive personality traits. Psychological suzhi is also the foundation for middle school students’ success across various settings (e.g. academic, interpersonal) and forms the basis for their realisation of life values. Meanwhile, self-esteem refers to individuals’ positive self-evaluations and positive emotional experiences within social contexts [7]. Therefore, psychological suzhi is an important catalyst for students’ self-esteem, and high psychological quality predicts high self-esteem.

Finally, the finding that psychological suzhi positively relates to sense of security also supports our hypothesis. One possible explanation for this result is that psychological suzhi is an endogenous factor of mental health [45], and sense of security is one of nine main mental health criteria [46]. Thus, psychological suzhi may predict a sense of security.

Hypothesis 2 was also supported in this study, as self-esteem and sense of security were found to play a mediating role in the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety, with the mediating effect equalling 65.6%. Psychological suzhi was determined to have a direct effect on social anxiety and an indirect effect on it through self-esteem and sense of security. Specifically, self-esteem and sense of security mediated the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety through two significant paths. The first of these was psychological suzhi → self-esteem → social anxiety, which had an effect of 27.2%. This result suggests that psychological suzhi is an important catalyst for students’ self-esteem. Individuals with high self-esteem tend to have more positive views of themselves and, in the process of interacting with people, show more initiative. However, those with low self-esteem have a more negative self-evaluation, and they are more passive in their interpersonal communication [47]. As a result, adolescents with low self-esteem have greater social anxiety. This finding is consistent with the cognitive behavioural theory of social anxiety, which suggests that low self-esteem is the main cause of social anxiety [24]. The second path between psychological suzhi and social anxiety was psychological suzhi → self-esteem → sense of security → social anxiety, for which the mediating effect was 43.3%. This finding indicates that self-esteem and sense of security serve as chain mediators in the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety. Indeed, past research has found that sense of security is associated with self-esteem. For example, Klandermans and van Vuuren [48] found that certain personality characteristics, such as self-esteem, determine perceptions of job insecurity. Similarly, Kinnunen et al. [49] showed that low self-esteem can significantly predict subsequent job insecurity. Further, the sociometer theory of self-esteem proposed that people with high self-esteem have a sense of competence and value. They are able to handle problems associated with social interactions and higher security and control; consequently, they have less interpersonal anxiety [50]. With regard to the finding that sense of security is negatively related to social anxiety, past studies have revealed that sense of security is positively associated with interpersonal relationships, and successful interpersonal interactions help individuals form a high level of self-esteem in social situations and alleviate social anxiety [51]. Therefore, self-esteem may influence individuals’ sense of security, which, in turn, affects their social anxiety. Thus, sense of security served to mediate the relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety, psychological suzhi promotes self-esteem, and self-esteem and sense of security serve as chain mediators in the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety. This finding implies that, as a comprehensive psychological construct, psychological suzhi can influence individuals’ self-evaluations and their perceptions and control of interpersonal security. It can also predict the occurrence of social anxiety. The discovery of this mediating role will help reduce social anxiety by starting with self-esteem and sense of security.

As with any study, this current one has some limitations. First, this study was cross-sectional in nature, which precludes any causal inferences. Thus, future longitudinal or experimental research is needed to identify the possible causal relationships. Second, only Chinese adolescent students were included; consequently, caution is needed when generalising these results to other cultures or age groups. Despite these shortcomings, this study still has great theoretical and practical significance. In particular, the present study has important implications for the theoretical construction and practical treatment of social anxiety. Theoretically, the findings demonstrate a new function of psychological suzhi based on its influence on social anxiety via self-esteem and sense of security, which is consistent with the relationship model of psychological suzhi and mental health [45]. Future research is needed to further examine the role that sense of security plays in preventing social anxiety and protecting mental health, given its relationship with psychological suzhi, as revealed in the current study. Moreover, the current findings have several practical implications. First, school leaders and psychology teachers should plan and implement routine psychological suzhi training courses to improve students’ psychological suzhi, thereby preventing social anxiety. Second, when school counsellors interview students with low psychological suzhi and high levels of social anxiety, they can support these students by encouraging them to participate in extracurricular activities and gain positive self-experience from these activities. Doing so can help these students develop positive self-perceptions [52], consequently helping them develop basic interpersonal communication skills and alleviating their senses of insecurity and uncertainty.

Conclusions

As anticipated, psychological suzhi, self-esteem, sense of security, and social anxiety were closely related to each other. Moreover, self-esteem and sense of security were determined to mediate the relationship between psychological suzhi and social anxiety. Notably, the chain mediating effect of self-esteem and sense of security was very strong. This result implied that psychological suzhi can directly protect adolescents from social anxiety, and it can also protect them by increasing their self-esteem and sense of security. The results of this study provide a new perspective for the prevention and treatment of social anxiety. In addition, they hold great implications for the prevention and treatment of social anxiety within a campus environment. It is important for education agencies and families to reinforce adolescents’ psychological suzhi in various ways, including training in psychological suzhi and its components. These findings are also of great significance to the practical work of psychological counselling.

Authors’ contributions

ZP designed the study; collected, analysed, and interpreted the data; drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content; and gave approval for the article to be published in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. DZ conceptualised this study and gave approval for the article to be published in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. TH revised this article critically for important intellectual content and gave approval for the article to be published in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. YP critically revised this article for important intellectual content and gave approval for the article to be published in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the students and teachers who participated, and we are grateful to the faculty and staff at the Research Center of Mental Health Education of Southwest University for their generous support and valuable advice.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed for the present study and the photographs used in the photograph rating are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

All participants consented to the publication of the anonymous results obtained by this survey.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the author’s institution (Southwest University). In addition, the heads of the participating middle schools and the participants’ parents gave their written consent. Additionally, the student participants provided their oral consent. The study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Funding

This research was supported by the Southwest University Research-oriented Faculty Construction Project (2017–2018).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- Suzhi

psychological suzhi

- SE

self-esteem

- SS

sense of security

- SA

social anxiety

Contributor Information

Zhaoxia Pan, Email: chaoxia830621@163.com.

Dajun Zhang, Phone: 1350949548, Email: zhangdj@swu.edu.cn.

Tianqiang Hu, Email: htqpsy@126.com.

Yangu Pan, Email: panyg@swufe.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zhang D, Feng Z, Guo C, Cheng X. Problems on research of students’ mental quality. J Southwest China Norm Univ (Humanit Soc Sci Ed) 2000;26(03):56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen D, Ma H, Bai X. An empirical study on the mental health diathesis for adolescents. Psychol Sci. 2009;12(02):258–261. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilman R, Furlong M, Huebner ES. Handbook of positive psychology in schools. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang D. On man’s mental quality. Stud Psychol Behav. 2003;1(02):143–146. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu T, Zhang D. The relationship between psychological suzhi and depression: the mediating role of self-serving attribution bias. J Southwest Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 2015;41(06):104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong Z, Zhang D. The relationship between psychological suzhi, emotion regulation strategies and life satisfaction among middle school student. J Southwest Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 2015;41(06):99–103+191. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu X, Wu S. Psychological quality and subjective well-being of college students: the mediating role of self-esteem. J Guangxi Norm Univ Philos Soc Sci Ed. 2010;46(06):86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Liang Y, Su Z, Cheng G, Zhang D. The relationship between secondary school students’ psychological quality and positive emotions: the mediating effect of emotional resilience. Chin J Spec Educ. 2015;12(09):71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Zhang D. Looking beyond PTH and DFM: the relationship model between psychological suzhi and mental health. J Southwest Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 2012;38(06):67–74+174. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Zalk N, Van Zalk M. The importance of perceived care and connectedness with friends and parents for adolescent social anxiety. J Pers. 2015;83(3):346–360. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borowski SK, Zeman J, Braunstein K. Social anxiety and socioemotional functioning during early adolescence: the mediating role of best friend emotion socialization. J Early Adolesc. 2018;38(2):238–260. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brook CA, Willoughby T. The social ties that bind: social anxiety and academic achievement across the university years. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(5):1139–1152. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrera TL, Norton PJ. Quality of life impairment in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(8):1086–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davila J, Beck JG. Is social anxiety associated with impairment in close relationships? A preliminary investigation. Behav Ther. 2002;33(3):427–446. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercer N, Crocetti E, Meeus W, Branje S. Examining the relationship between adolescent social anxiety, adolescent delinquency(abstention), and emerging adulthood relationship quality. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2017;30(4):428–440. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2016.1271875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdollahi A, Yaacob SN, Abu Talb M, Ismall Z. Social anxiety and cigarette smoking in adolescents: the mediating role of emotion intelligence. Sch Ment Health. 2015;7(3):184–192. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papachristou H, Aresti E, Theodorou M, Panayiotou G. Alcohol outcome expectancies mediate the relationship between social anxiety and alcohol drinking in university students: the role of gender. Cogn Ther Res. 2018;42(3):289–301. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH, Church AT. Social anxiety in Asian Americans: integrating personality and cultural factors. Asian Am J Psychol. 2017;8(2):103. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gkika S, Wittkowski A, Wells A. Social cognition and metacognition in social anxiety: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2018;25(1):10–30. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allan NP, Oglesby ME, Uhl A, Schmidt NB. Cognitive risk factors explain the relations between neuroticism and social anxiety for males and females. Cogn Behav Ther. 2017;46(3):224–238. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2016.1238503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson B, Goldin PR, Kurita K, Gross JJ. Self-representation in social anxiety disorder: linguistic analysis of autobiographical narratives. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(10):1119–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrewijn A, Schmidt LA, Westenberg PM, Tang A, vander Molen MJW. Electrocortical measure of information processing biased in social anxiety disorder: a review. Biol Psychol. 2017;129:324–348. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu G, Zhang D, Pan Y, Hu T, He N, Chen W, Wang Z. Self-concept clarity and subjective social status as mediators between psychological suzhi and social anxiety in Chinese adolescents. Pers Individ Differ. 2017;108:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan J, Banerjee R. Social anxiety and self-evaluation of social performance in a nonclinical sample of children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35(2):292–301. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng G, Zhang D, Ding F. Self-esteem and fear of negative evaluation as mediators between family socioeconomic status and social anxiety in Chinese emerging adults. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61(6):569–576. doi: 10.1177/0020764014565405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cong Z, An L. Developing of security questionnaire and its reliability and validity. Chin Ment Health J. 2004;18(02):97–99. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maslow AH, Hirsh E, Stein M, Honigmann I. A clinically derived test for measuring psychological security–insecurity. J Gen Psychol. 1945;33(1):21–41. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell J, Moskowitz D, Zuroff D, Bleau P, Pinard G, Young S. Anxiety, emotional security and the interpersonal behavior of individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychol Med. 2011;41(3):545–554. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stotland E. Motivation for security, certainty, and self-esteem. J Gen Psychol. 1961;65(1):75–87. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie J, Yu H, Feng Z, Yang G, Jiang J. Correlation between mental quality and personality and mental health of young army men. Progr Mod Biomed. 2011;11(11):2163–2167. [Google Scholar]

- 31.An L, Cong Z, Wang X. Research of high school students’ security and the related factors. Chin Ment Health J. 2004;18(10):717–719. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makkar SR, Grisham JR. Social anxiety and the effects of negative self-imagery on emotion, cognition, and post-event processing. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(10):654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu T, Zhang D, Cheng G. The compilation of a brief psychological suzhi questionnaire for middle school students. J Southwest Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 2017;43(02):120–126. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian L. Shortcoming and merits of Chinese version of Rosenberg (1965) Self-esteem scale. Psychol Explor. 2006;26(2):88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson D, Friend R. Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1969;33(4):448. doi: 10.1037/h0027806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.An Q, Chen H. Relationship between differentiation of self and social avoidance and distress: moderating roles of security. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2015;23(05):791–794+798. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998. p. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Y, Wen ZL. Item parceling strategies in structural equation modeling. Adv Psychol Sci. 2011;19(12):1859–1867. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Newbury Park: Sage Focus Editions; 1993. p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The impact of early adverse experiences on brain systems involved in the pathophysiology of anxiety and affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(11):1509–1522. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu G, Zhang D, Pan Y, Chen W, Ma Y. The relationship between middle school students’ psychological suzhi and peer relationship: the mediating role of self-esteem. Chin J Psychol Sci. 2016;39(6):1290–1295. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, Su Z. The relationship between personality of psychological suzhi and mental health among university students. J Southwest Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 2015;41(06):110–114+191. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Zhang D. Looking beyond PTH and DFM: the relationship model between psychological suzhi and mental health. J Southwest Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 2012;38(06):67–74+174. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. New York: Harper and Row; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, et al. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2003;4(1):1–44. doi: 10.1111/1529-1006.01431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klandermans B, van Vuuren T. Job insecurity: introduction. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 1999;8(2):145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kinnunen U, Mauno S, Natti J, Happonen M. Perceived job insecurity: a longitudinal study among Finnish employees. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 1999;8(2):243–260. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bi YL, Ma LJ, Yuan F, Zhang BS. Self-esteem, perceived stress and gender during adolescence: interactive links to different types of interpersonal relationships. J Psychol. 2016;150(1):36–57. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2014.996512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paulk AH, Pittman J, Kerpelman J, Alder-Baeder F. Associations between dimensions of security in romantic relationships and interpersonal competence among dating and non-dating high school adolescents. J Soc Pers Relationsh. 2011;28(8):1027–1047. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarquin K, Cook-Cottone C. Relationships among aspects of student alienation and self concept. Sch Psychol Q. 2008;23(1):16–18. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analysed for the present study and the photographs used in the photograph rating are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.