Abstract

Immunotherapy with interleukin-2 can cure 5 to 10% of patients with metastatic melanoma and renal cancer. Recent adoptive cell transfer (ACT) immunotherapies have improved cure rates in metastatic melanoma to 20 to 40%. Genetic engineering of T cells to express conventional alpha/beta T cell receptors or antibody-based chimeric antigen receptors provides an opportunity to extend ACT to patients with common epithelial cancers.

There has been little progress in the development of curative treatments for patients with metastatic solid cancers since the development over 30 years ago of curative chemotherapy for patients with metastatic germ cell tumors and choriocarcinomas. One important exception has been the recent development of immunotherapy, which can cure patients with metastatic melanoma. Recent progress in the development of T cell transfer studies has improved cure rates for melanoma patients, and the genetic engineering of T cells to express anticancer receptors is extending this approach to the treatment of common epithelial cancers (1, 2).

THE NEED FOR CURATIVE CANCER TREATMENTS

The inability to cure patients with metastatic common solid cancers such as breast, colon, prostate, ovary, and others resulted in the cancer-related deaths of over 560,000 Americans in 2010. Even the most successful new drugs such as trastuzumab (Herceptin) and bevacizumab (Avastin) (which cost patients $6 billion and $7.4 billion, respectively, in 2010) prolong survival of patients with meta-static cancer only by months when combined with chemotherapy—and cure no one with metastatic disease. The bar for the approval of new cancer drugs by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is low, and drugs are commonly approved that have minimal impact on survival. A course of erlotinib (Tarceva) for pancreatic cancer that can prolong median survival by less than two weeks and results in no cures costs over $15,000 per course (and has substantial side effects) (3).

Eighteen new drugs to treat cancer were approved by the FDA between July 2005 and December 2007—none of which had curative potential for patients with metastatic solid cancers (4). Conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy agents are limited by toxicity to normal tissues. New “targeted” agents are designed to exploit specific mutational events in vital signaling pathways, and although impressive cancer regressions can be seen, the redundancy in these pathways appears invariably to lead to tumor regrowth and death of the patient. Indeed, a major cost of cancer care in the United States results from cancer patients moving from one minimally effective drug to another.

Curative treatments require the recognition, with a high degree of specificity, of changes that distinguish normal from malignant cells. The immune system of vertebrates evolved in part to detect, with exquisite sensitivity and specificity, molecules or cells that are “non-self” and exhibit aberrations from normal. Immunotherapy based on stimulating lymphocytes to detect distinct “non-self” changes in cancer cells represents an approach that can cure some patients with widespread bulky metastatic melanoma and kidney cancer. The development of immunotherapy for melanoma holds lessons for both the progress and pitfalls of extending immunotherapy to the cure of patients with additional cancer types.

IMMUNOTHERAPY CAN CURE PATIENTS WITH METASTATIC MELANOMA AND RENAL CANCER

The discovery of T cell growth factor (inter-leukin-2, IL-2) in 1976 enabled, for the first time, the growth of T cells in the laboratory and thus greatly expanded studies of the role and function of lymphocytes (5). The cloning of the gene encoding IL-2 and its expression in recombinant vectors enabled the production of large amounts of this molecule and provided an important stimulus to the development of cancer immunotherapy (6, 7). IL-2, which is naturally produced by T lymphocytes, can mediate the in vivo growth and expansion of immune cells that express high-affinity IL-2 receptors, which appear on the T cell surface when it encounters its cognate antigen. The ability of IL-2 administration to mediate antitumor effects in experimental animals led to its clinical study in patients with a wide variety of cancer types.

The administration of IL-2 to patients with metastatic cancer was the first reproducible demonstration in humans that manipulation of the immune system could lead to durable cancer regressions (8). Patients with metastatic melanoma or renal cancer experience a 5 to 10% rate of complete cancer regression, with an additional 10% experiencing a partial regression (RECIST criteria) (9–12). Approximately 70% of complete responders to IL-2 therapy do not recur and are likely cured. In patients with metastatic melanoma or kidney cancer treated in the Surgery Branch of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) with high doses of IL-2, 24 of 33 complete responders have ongoing complete regression up to 25 years after treatment (10), which is similar to findings in a multi-institutional study of patients with metastatic melanoma treated with IL-2 (11). A recent prospective randomized trial showed that adding a melanoma peptide vaccine to IL-2 administration significantly improved the overall as well as the complete response rates in melanoma patients as compared with treatments of IL-2 alone (13). The ability of high-dose IL-2 to mediate durable complete regressions led to its approval by the FDA for the treatment of patients with metastatic renal cancer in 1992 and metastatic melanoma in 1998. Patients that did not achieve a complete regression of metastatic disease ultimately progressed and died of their disease.

Before the approval of IL-2 by the FDA, the only approved treatment for patients with metastatic melanoma was the chemotherapy agent dacarbazine, which only rarely, if ever, produced complete regressions (14). More recently, two new treatments for patients with metastatic melanoma have been approved (Table 1). Blockade of CTLA-4 with ipilimumab, a monoclonal antibody reactive with the inhibitory CTLA-4 cell-surface molecule, blocks inhibitory signals on T lymphocytes and has been shown to prolong median survival in patients with melanoma by 3.7 months as compared with a peptide vaccine (15). However, of 540 patients treated with ipilimumab only three (0.6%) had a complete regression of their disease, and it is thus unclear how many will ultimately be cured. Vemurafenib, which is an inhibitor of the mutant BRAF molecule expressed in approximately 50 to 60% of metastatic melanomas, can improve median progression-free survival by about 3.7 months compared with dacarbazine (14). Although response rates are high, only two of 219 (0.9%) patients achieved a complete regression, and it appears that most, if not all, responding patients ultimately experience recurrence of their metastatic melanoma.

Table 1.

Objective responses in patients with metastatic melanoma.

| Treatment (reference) | Total | Number of patients (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | PR | OR | ||

| Dacarbazine (14) | 220 | 0 | 12 (5.5%) | 12 (5.5%) |

| Interleukin-2 (11) | 270 | 17 (6.3%) | 26 (9.6%) | 43 (15.9%) |

| Ipilimumab (15) | 540 | 3 (0.6%) | 35 (6.4%) | 38 (7.0%) |

| Vemurafenib (14) | 219 | 2 (0.9%) | 104 (47.5%) | 106 (48.4) |

| Cell transfer (1) | 93 | 20 (21.5%) | 32 (34.4%) | 52 (55.9%) |

The superior ability of IL-2 to mediate durable complete regression is also seen in renal cancer. There are now seven FDA-approved treatments for patients with meta-static renal cell cancer. Complete regression data are available for five of these agents. Sorafenib (16), sunitinib (17), everolimus (18), and pazopanib (19) have complete regression rates of 0.2%, 0.2%, 0%, and 0.5%, respectively, in studies encompassing more than 1000 patients. In 259 consecutive patients treated in the Surgery Branch of the NCI with IL-2, 9% experienced complete regressions, and over two-thirds of these patients have never recurred—with many ongoing beyond 20 years (9).

Although nonspecific immune stimulation with either IL-2 or ipilimumab can mediate tumor regression in patients with melanoma, other more common epithelial histologies do not appear to respond to these agents. It thus appears that patients with melanoma and renal cancer naturally generate endogenous antitumor T cell precursors that are inactive in vivo until these cells are stimulated by IL-2. Multiple shared target antigens in melanoma have been characterized; however, it appears that the predominant endogenous immune reactions effective in treating melanoma are directed against mutations expressed specifically on individual melanomas. Melanomas have among the highest mutation rates of any cancer type, which may explain, in part, their singular responsiveness to IL-2 (20). It has been far more difficult to identify target antigens in patients with renal cancer, and alternate mechanisms involving the action of natural killer cells may be involved in mediating the immuno-therapy response against this cancer.

Surprisingly, immunotherapy with IL-2 administration—which in most circumstances is the only curative treatment available to patients with metastatic melanoma and kidney cancer—is often not used for the treatment of these patients. Sales estimates of IL-2 suggest that less than 10% of eligible metastatic melanoma and renal cancer patients actually receive this potentially curative drug, probably because IL-2 is more difficult to administer because it requires hospitalization and has an unusual toxicity profile compared with conventional chemotherapies. Thus, many patients are being denied potentially curative treatment and receive instead treatments that are more convenient to administer but result in few, if any, cures.

ACTIVE IMMUNIZATION APPROACHES TO CANCER TREATMENT (CANCER VACCINES) DO NOT CURE

An alternate approach to immunotherapy has been the attempt to actively immunize patients against their metastatic cancer (“cancer vaccines”). Many thousands of patients in many hundreds of clinical trials of cancer vaccines using immunization with whole cells, proteins, peptides, recombinant viruses, dendritic cells, and naked DNA combined with a variety of adjuvants have failed to show any reproducible ability to mediate regression of metastatic cancer. A review of 58 published trials including 1306 metastatic cancer patients treated with cancer vaccines before 2004 (21) and a review of 936 patients treated in vaccine clinical trials between 2004 and 2010 (22) both revealed an overall objective response rate of 3 to 4%, with only rare complete responders. Although the FDA recently approved a dendritic-like vaccine for men with castration-resistant prostate cancer that improved survival by approximately 4 months, there were no complete responses and only one objective partial response in 330 patients (0.3%) (23). There was no difference in progression-free survival, and it appears that all patients ultimately progress and die of their disease. Although no cancer vaccines capable of reproducibly mediating cancer regression have been described to date, this approach continues to receive considerable attention as a potential treatment for metastatic cancer, perhaps in part because of the allure of easy distribution by pharmaceutical companies and outpatient administration.

ADOPTIVE CELL THERAPY AS A CURATIVE TREATMENT FOR PATIENTS WITH METASTATIC MELANOMA

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) involves the transfer of autologous immune T cells with antitumor activity to the cancer-bearing patient. ACT using either endogenous anti-tumor T cells or cells genetically engineered to express antitumor receptors represents the most direct evidence of the ability of T cells to mediate a high level of durable complete regressions in patients with metastatic cancer (2, 24).

Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) grown from resected melanoma deposits can be grown to large numbers in IL-2 while retaining reactivity against endogenous tumor-associated antigens. An important advance, reported in 2002, was the demonstration that the administration of a lymphodepleting regimen that eliminated T regulatory cells as well as lymphocytes that competed for homeostatic cytokines could lead to in vivo clonal expansion of administered autologous antitumor TILs and result in high levels of complete durable responses (25). In 93 patients with meta-static melanoma treated with autologous TILs expanded in vitro, 20 (21.5%) achieved the complete regression of their metastatic melanoma (Table 1) (1), with 19 of the 20 patients potentially cured—maintaining complete regressions from 4 to more than 8 years after therapy (1, 26). Seventeen of the 20 complete responders had Mlb or Mlc disease (visceral metastases), and the incidence of durable complete responses was the same regardless of any prior treatment the patient had received (1). There was also no relationship between the tumor burden or the BRAF or NRAS tumor mutation status and the likelihood of achieving a durable complete regression. When 12 Gy total-body irradiation was added to the cyclophosphamide and fludarabine lymphodepleting regimen, 40% of 25 patients achieved a complete cancer regression (overall response rate was 72%). Patients with metastatic melanoma who are capable of receiving this ACT treatment with autologous TILs have the highest chance of cure of any available treatment.

USE OF GENE MODIFIED LYMPHOCYTES FOR ADOPTIVE CELL THERAPY OF PATIENTS WITH NON MELANOMA METASTATIC CANCERS

The high curative potential of ACT in patients with metastatic melanoma has stimulated attempts to apply this approach to treating other cancer types. The identification of T cells with appropriate recognition of cancer antigens without detrimental effects on normal cells is the major challenge to extending the use of ACT beyond melanoma. TIL cells with antitumor activity can only be grown from melanoma deposits and not from other common epithelial cancers, perhaps because of the higher mutation rates seen in patients with melanoma as compared with other cancers. To overcome this obstacle, efforts have turned to the in vitro creation of cells with antitumor activity by the genetic engineering of circulating autologous lymphocytes from cancer patients by using genes that encode receptors capable of recognizing cancer antigens. Two types of antitumor receptors have been studied: conventional T cell receptors (TCRs) composed of a heterodimer of alpha and beta chains that recognize processed peptides presented on cell surface major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, and chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) constructed in the laboratory that contain the genes encoding the variable regions of the heavy and light chains of antibodies attached to T cell intracellular signaling molecules such as CD3 zeta, CD28, and 41BB (27). These CARs provide the T cell with the ability to recognize antigens based on the qualities of the encoded antibody.

There are major advantages as well as challenges involved in the genetic engineering of lymphocytes. Conventional TCRs with reactivity against antigens on solid cancers are rare, but even rare cells with antitumor activity can serve as the source of genes encoding appropriate antitumor receptors. If identified from either human cells or immunized MHC transgenic mice, these TCR genes can be incorporated into retroviruses and used to convert normal lymphocytes from patients into cells with anticancer activity (28–30). Similarly, antibodies reactive with cancer-associated antigens can be given a very powerful effector function by providing them with the killing activity of effector lymphocytes.

The first successful application of T cells genetically engineered with a conventional TCR targeted the MART-1 melanocyte/melanoma differentiation antigen (31) and achieved an objective regression in 2 of 15 (13%) patients with one complete regression that is now ongoing beyond 6 years. A follow-up study using higher-affinity receptors against the MART-1 and gp100 antigens achieved objective responses in 9 of 36 (25%) patients but also led to vitiligo, uveitis, and auditory toxicity because of the presence of targeted melanocytes at these sites (29). These initial studies demonstrated the power of using genetically engineered cells to attack metastatic cancer but also pointed to the importance of selecting an appropriate target antigen to avoid toxicity to normal tissues.

A class of antigens that appears ideal for targeting by autologous gene-engineered cells are the cancer-testes antigens, which are expressed during fetal development and are reexpressed in approximately 20 to 30% of common epithelial cancers but not in any normal adult tissues except for the testes (which do not express class 1 MHC molecules and thus are immunologically protected) (32). The first gene therapy studies in humans targeting cancer-testes antigens targeted the NY-ESO-1 antigen in patients with metastatic melanoma and metastatic synovial cell sarcoma (33). In these studies, 8 of 17 (47%) patients with metastatic melanoma and 8 of 10 (80%) patients with metastatic synovial sarcoma, all heavily pretreated with standard therapies, showed objective regressions of their metastatic cancer with no toxicity against normal tissues. There are more than 100 cancer-testes antigens that share cancer-associated expression, and TCRs targeting other cancer-testes antigens such as MAGE-A3 and SSX2 are under investigation.

The use of CARs has broadened the potential application of adoptive cell therapy using gene-modified cells to a wider variety of cancers. CAR T cells targeting the GD2 antigen can mediate modest clinical impact when applied to patients with neuroblastoma (34). The most successful use of CARs in the treatment of patients with metastatic cancer is the ability to target the CD19 molecule expressed on virtually all B cell lymphomas as well as normal B cells. The first report of this in 2010 used a CAR targeting CD19 and mediated tumor regression in a patient with advanced heavily pretreated B cell lymphoma that is now ongoing over 25 months after the patient received two treatments (35). Five of 6 additional patients exhibited an objective response, including one with an ongoing complete regression and four with partial regressions of greater than 80% on going between 10 and 28 months (36). This CAR gene therapy also eliminated normal B cells that expressed the CD19 antigen. These results have recently been confirmed by others (37).

The ability to genetically modify lymphocytes has greatly expanded the opportunities for manipulating the immune system against cancer. Cytokine genes can be inserted into lymphocytes to improve their function and survival. Additional target antigens are being explored, such as the EG-FRvIII mutation expressed on the surface of ~40% of glioblastomas as well as on head and neck cancers; a CAR recognizing this mutation is currently in clinical trial in the Surgery Branch, NCI, in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Stromal components of the tumor such as the vascular endothelial growth factor-2 (VEGFR-2) molecule on tumor vasculature (38) or the fibroblast activation protein (FAP) are also being targeted, thus providing an alternative to the need to target specific cancer antigens.

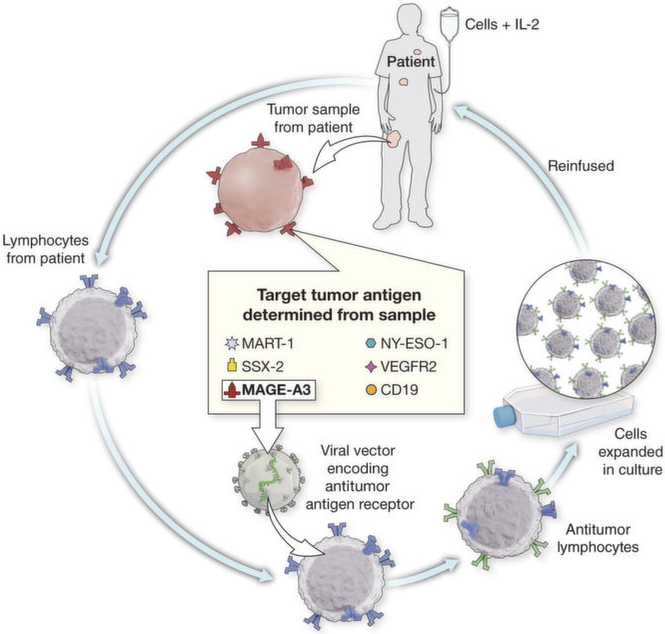

A general strategy of personalized treatment is being developed on the basis of the expression of antigens on individual cancers that will guide the genetic modification of autologous lymphocytes with TCRs or CARs appropriate for targeting that specific antigen (Fig. 1). A summary of clinical trials in the Surgery Branch, NCI, using genetically engineered autologous lymphocytes for cancer treatment is shown in Table 2.

Fig. 1. A schema for personalized immunotherapy using gene-modified cells.

The antigen expression is determined on a tumor biopsy. An appropriate T cell receptor that recognizes that specific antigen is then retrovirally transduced into the patients’ autologous lymphocytes. The lymphocytes are expanded in vitro and infused.

Table 2.

Program for the application of cell transfer therapy to a wide variety of human cancers in the Surgery Branch, NCI.

| Receptor (references) | Type | Cancer | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| MART-1 (29) | TCR | Melanoma | Accrued |

| gp100 (29) | TCR | Melanoma | Accrued |

| NY-ESO-1 (33) | TCR | Epithelial and sarcomas | Accruing |

| CEA (30) | TCR | Colorectal | Accrued |

| CD19 (35) | CAR | Lymphomas | Accruing |

| VEGFR2 (38) | CAR | All cancers | Accruing |

| 2G-1 (39) | TCR | Kidney | Accruing |

| IL-12 (40) | Cytokine | Adjuvant for all receptors | Accruing |

| MAGE-A3*(41) | TCR | Epithelial | In development |

| EGFRvIII | CAR | Glioblastoma | Accruing |

| SSX-2 | TCR | Epithelial | In development |

| Mesothelin | CAR | Pancreas and mesothelioma | In development |

HLA-A2, A1, Cw7, DP4 restricted MAGE-A3 TCRs in development; will cover 80% of patients.

Experimental ACT approaches for patients with metastatic melanoma are only available in a limited number of academic institutions, and there appears to be minimal but increasing commercial interest in their development. ACT represents the ultimate “personalized” cancer therapy—a new drug is created for every patient—and thus does not fit the paradigm attractive to pharmaceutical companies, which desire drugs that can be vialed for ease of administration. Possible strategies to promote widespread use of ACT include the production of TILs or genetically engineered T cells by cell production laboratories that are available in blood banks, or the establishment by commercial companies of central facilities that can accept shipped tumors or phereses and prepare the therapeutic cells for delivery to the treating institution. The use of ACT approaches can cure patients with metastatic melanoma refractory to other treatments and has the potential to cure other cancer types as well. An important challenge is the development of a means to make these potentially curable cell transfer approaches more widely available to patients with cancer.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Phan GQ, Citrin DE, Restifo NP, Robbins PF, Wunderlich JR, Morton KE, Laurencot CM, Steinberg SM, White DE, Dudley ME, Durable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma using T-cell transfer immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 4550–4557 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SA, Cell transfer immunotherapy for meta-static solid cancer—What clinicians need to know. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 8, 577–585 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Figer A, Hecht JR, Gallinger S, Au HJ, Murawa P, Walde D, Wolff RA, Campos D, Lim R, Ding K, Clark G, Voskoglou-Nomikos T, Ptasynski M, Parulekar W; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group, Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J. Clin. Oncol 25, 1960–1966 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sridhara R, Johnson JR, Justice R, Keegan P, Chakravarty A, Pazdur R, Review of oncology and hematology drug product approvals at the US Food and Drug Administration between July 2005 and December 2007. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 102, 230–243 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan DA, Ruscetti FW, Gallo RG, Selective in vitro growth of T lymphocytes from normal human bone marrows. Science 193, 1007–1008 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taniguchi T, Matsui H, Fujita T, Takaoka C, Kashima N, Yoshimoto R, Hamuro J, Structure and expression of a cloned cDNA for human interleukin-2. Nature 302, 305–310 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, Grimm EA, McGrogan M, Doyle M, Kawasaki E, Koths K, Mark DF, Biological activity of recombinant human interleukin-2 produced in Escherichia coli. Science 223, 1412–1414 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Muul LM, Leitman S, Chang AE, Ettinghausen SE, Matory YL, Skibber JM, Shiloni E, Vetto JT, Seipp CA, Simpson C, Reichert CM, Observations on the systemic administration of autologous lymphokine-activated killer cells and recombinant interleukin-2 to patients with metastatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 313, 1485–1492 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klapper JA, Downey SG, Smith FO, Yang JC, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Steinberg SM, Rosenberg S, High-dose interleukin-2 for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A retrospective analysis of response and survival in patients treated in the surgery branch at the National Cancer Institute between 1986 and 2006. Cancer 113, 293–301 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith FO, Downey SG, Klapper JA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Restifo NP, Levy CL, White DE, Steinberg SM, Rosenberg SA, Treatment of metastatic melanoma using interleukin-2 alone or in conjunction with vaccines. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 5610–5618 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, Fisher RI, Weiss G, Margolin K, Abrams J, Sznol M, Parkinson D, Hawkins M, Paradise C, Kunkel L, Rosenberg SA, High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: Analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J. Clin. Oncol 17, 2105–2116 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, White DE, Steinberg SM, Durability of complete responses in patients with meta-static cancer treated with high-dose interleukin-2: Identification of the antigens mediating response. Ann. Surg 228, 307–319 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartzentruber DJ, Lawson DH, Richards JM, Conry RM, Miller DM, Treisman J, Gailani F, Riley L, Conlon K, Pockaj B, Kendra KL, White RL, Gonzalez R, Kuzel TM, Curti B, Leming PD, Whitman ED, Balkissoon J, Reintgen DS, Kaufman H, Marincola FM, Merino MJ, Rosenberg SA, Choyke P, Vena D, Hwu P, gp100 peptide vaccine and interleukin-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med 364, 2119–2127 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, Dummer R, Garbe C, Testori A, Maio M, Hogg D, Lorigan P, Lebbe C, Jouary T, Schadendorf D, Ribas A, O’Day SJ, Sosman JA, Kirkwood JM, Eggermont AM, Dreno B, Nolop K, Li J, Nelson B, Hou J, Lee RJ, Flaherty KT, McArthur GA; BRIM-3 Study Group, Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N. Engl. J. Med 364, 2507–2516 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, Akerley W, van den Eertwegh AJ, Lutzky J, Lorigan P, Vaubel JM, Linette GP, Hogg D, Ottensmeier CH, Lebbé C, Peschel C, Quirt I, Clark JI, Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Tian J, Yellin MJ, Nichol GM, Hoos A, Urba WJ, Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med 363, 711–723 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, Negrier S, Chevreau C, Solska E, Desai AA, Rolland F, Demkow T, Hutson TE, Gore M, Freeman S, Schwartz B, Shan M, Simantov R, Bukowski RM; TARGET Study Group, Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med 356, 125–134 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Kim ST, Chen I, Bycott PW, Baum CM, Figlin RA, Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med 356, 115–124 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, Grünwald V, Thompson JA, Figlin RA, Hollaender N, Kay A, Ravaud A; RECORD-1 Study Group, Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer 116, 4256–4265 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, Szczylik C, Lee E, Wagstaff J, Barrios CH, Salman P, Gladkov OA, Kavina A, Zarbá JJ, Chen M, McCann L, Pandite L, Roychowdhury DF, Hawkins RE, Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results of a randomized phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol 28, 1061–1068 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, Edkins S, O’Meara S, Vastrik I, Schmidt EE, Avis T, Barthorpe S, Bhamra G, Buck G, Choudhury B, Clements J, Cole J, Dicks E, Forbes S, Gray K, Halliday K, Harrison R, Hills K, Hinton J, Jenkinson A, Jones D, Menzies A, Mironenko T, Perry J, Raine K, Richardson D, Shepherd R, Small A, Tofts C, Varian J, Webb T, West S, Widaa S, Yates A, Cahill DP, Louis DN, Goldstraw P, Nicholson AG, Brasseur F, Looijenga L, Weber BL, Chiew YE, DeFazio A, Greaves MF, Green AR, Campbell P, Birney E, Easton DF, Chenevix-Trench G, Tan MH, Khoo SK, Teh BT, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Wooster R, Futreal PA, Stratton MR, Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature 446, 153–158 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP, Cancer immuno-therapy: Moving beyond current vaccines. Nat. Med 10, 909–915 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klebanoff CA, Acquavella N, Restifo Z. Yu, N. P., Therapeutic cancer vaccines: Are we there yet? Immunol. Rev 239, 27–44 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, Redfern CH, Ferrari AC, Dreicer R, Sims RB, Xu Y, Frohlich MW, Schellhammer PF; IMPACT Study Investigators, Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 363, 411–422 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP, Yang JC, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Adoptive cell transfer: A clinical path to effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 299–308 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Sherry R, Restifo NP, Hubicki AM, Robinson MR, Raffeld M, Duray P, Seipp CA, Rogers-Freezer L, Morton KE, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Rosenberg SA, Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science 298, 850–854 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, Hughes MS, Royal R, Kammula U, Robbins PF, Huang J, Citrin DE, Leitman SF, Wunderlich J, Restifo NP, Thomasian A, Downey SG, Smith FO, Klapper J, Morton K, Laurencot C, White DE, Rosenberg SA, Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: Evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J. Clin. Oncol 26, 5233–5239 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross G, Waks T, Eshhar Z, Expression of immunoglobulin-T-cell receptor chimeric molecules as functional receptors with antibody-type specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 10024–10028 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theobald M, Biggs J, Dittmer D, Levine AJ, Sherman LA, Targeting p53 as a general tumor antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 11993–11997 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Cassard L, Yang JC, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Royal RE, Sherry RM, Wunderlich JR, Lee CC, Restifo NP, Schwarz SL, Cogdill AP, Bishop RJ, Kim H, Brewer CC, Rudy SF, VanWaes C, Davis JL, Mathur A, Ripley RT, Nathan DA, Laurencot CM, Rosenberg SA, Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood 114, 535–546 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parkhurst MR, Yang JC, Langan RC, Dudley ME, Nathan DA, Feldman SA, Davis JL, Morgan RA, Merino MJ, Sherry RM, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Phan GQ, Lim RM, Wank SA, Restifo NP, Robbins PF, Laurencot CM, Rosenberg SA, T cells targeting carcinoembryonic antigen can mediate regression of metastatic colorectal cancer but induce severe transient colitis. Mol. Ther 19, 620–626 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Restifo NP, Zheng Z, Nahvi A, de Vries CR, Rogers-Freezer LJ, Mavroukakis SA, Rosenberg SA, Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science 314, 126–129 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson AJ, Caballero OL, Jungbluth A, Chen YT, Old LJ, Cancer/testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 615–625 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Nahvi AV, Helman LJ, Mackall CL, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Restifo NP, Raffeld M, Lee CC, Levy CL, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Schwarz SL, Laurencot C, Rosenberg SA, Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J. Clin. Oncol 29, 917–924 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pule MA, Savoldo B, Myers GD, Rossig C, Russell HV, Dotti G, Huls MH, Liu E, Gee AP, Mei Z, Yvon E, Weiss HL, Liu H, Rooney CM, Heslop HE, Brenner MK, Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: Persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nat. Med 14, 1264–1270 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kochenderfer JN, Wilson WH, Janik JE, Dudley ME, Stetler-Stevenson M, Feldman SA, Maric I, Raffeld M, Nathan DA, Lanier BJ, Morgan RA, Rosenberg SA, Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood 116, 4099–4102 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Feldman SA, Wilson WH, Spaner DE, Maric I, Stetler-Stevenson M, Phan GQ, Hughes MS, Sherry RM, Yang JC, Kammula US, Devillier L, Carpenter R, Nathan D-AN, Morgan RA, Laurencot C, Rosenberg SA, B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood (2011). 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, Katz S, Grupp SA, Bagg A, June CH, T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med 3, 95ra73 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chinnasamy D, Yu Z, Theoret MR, Zhao Y, Shrimali RK, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA, Gene therapy using genetically modified lymphocytes targeting VEGFR-2 inhibits the growth of vascularized syngenic tumors in mice. J. Clin. Invest 120, 3953–3968 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanada K, Wang QJ, Inozume T, Yang JC, Molecular identification of an MHC-independent ligand recognized by a human α/β T-cell receptor. Blood 117, 4816–4825 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L, Kerkar SP, Yu Z, Zheng Z, Yang S, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA, Improving adoptive T cell therapy by targeting and controlling IL-12 expression to the tumor environment. Mol. Ther 19, 751–759 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chinnasamy N, Wargo JA, Yu Z, Rao M, Frankel TL, Riley JP, Hong JJ, Parkhurst MR, Feldman SA, Schrump DS, Restifo NP, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA, A TCR targeting the HLA-A*0201-restricted epitope of MAGE-A3 recognizes multiple epitopes of the MAGE-A antigen superfamily in several types of cancer. J. Immunol 186, 685–696 (2011). 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]