Abstract

Introduction

Occupational therapy (OT) is defined as the promotion of client health and well-being through a client-centred practice. However, there is a tendency to rely on the therapist’s experiences and values, and there is a difference between the client’s and therapist’s perceptions regarding the current activity that the client is engaged in. In previous studies that have applied ‘flow’, activities supported by OT in elderly people were analysed, indicating a difference in recognition. Therefore, we thought that more effective OT could be implemented by adjusting the challenge–skill (ACS) balance, and we invented a novel process termed as ACS balance for OT. The purpose of this study is to verify the effect of ACS-OT on clients in the recovery rehabilitation unit and to prepare a protocol for randomised controlled trial (RCT) implementation.

Method and analysis

This single-blind RCT will recruit 80 clients aged 50–99 years admitted to the recovery rehabilitation unit who meet eligibility criteria. Clients will be randomly allocated to receive ACS-OT or standard OT. Both interventions will be performed during the clients’ residence at the unit. The primary outcome measure will be subjective quality of life and will be measured at entry into (pre) and at discharge from (post) the unit and at 3 months afterwards (follow-up). Outcomes will be analysed using a linear mixed model fitted with a maximum likelihood estimation.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol has been approved by the ethics review committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan University (No.17020). Results of this trial will be submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

UMIN-CTR number, UMIN000029505; Pre-results.

Keywords: rehabilitation medicine, occupational therapy, flow model, randomised control trial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We designed a randomised controlled trial to verify if ACS-OT is effective in improving subjective quality of life.

Stratified randomisation is responsible for homogeneous assignment of experimental group and control group.

Outcomes analysis using clients as random effect by linear mixed model.

It is impossible to blind the therapists because of the nature of intervention in the OT process.

Our study results will be limited to the recovery rehabilitation unit.

Background

Rehabilitation aims to maximally promote the process of recovery from injury, illness or disease, supporting the client to reach a normal condition. An occupational therapist is a health professional who aims to support the client to return to independence, meaning, satisfaction in all aspects of people’s lives. Likewise, occupational therapy (OT) is defined as a profession that promotes clients’ health and well-being through a client-centred practice. In many countries, client-centred practice is the basis for OT; this practice contributes to the realisation of meaningful activities for the client,1–5 which are defined as familiar activities which aligns with an individual’s pursuit of valued developmental goals to maintain a personally meaningful lifestyle.6 7 In saying this, within processes related to a client-centred practice, there is a tendency to rely on the therapist’s experience and values. There is a difference between the client’s and therapist’s perceptions regarding the activity engaged in by the client.8 9 To support the activity desired by the client, it is necessary to determine the client’s evaluation of the activity in a form that the client and the therapist can easily share. In addition, deterioration of the client’s health and physical and mental functions, and loss of social role often causes decreased motivation to perform these activities.10 11 Therefore, in OT, it is necessary for clients and therapists to easily share the meaning of activity and to provide support that facilitates positive client mental state. To reflect this in our research, we applied the concept of ‘flow’, which captures the psychological state of a particular activity. Flow is defined as ‘the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter at the time; the experience is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it’.12 With regard to research on flow in the OT field, there have been reports on improved happiness, self-esteem, work productivity and subjective well-being level.13–18 According to Csikszentmihalyi,12 flow can be explained according to the balance between challenge and skills, that is, the ‘flow model’. Flow is experienced when an individual’s perception of the difficulty associated with an activity is balanced with their level of skill. Conversely, activities in which the individual’s skill is perceived to be too close to the difficulty associated with the activity leads to boredom. Similarly, conditions of low-perceived skill in a high-perceived challenge result anxiety, whereas conditions of low-perceived skill and low-perceived challenge result in apathy. Several cross-sectional studies using the flow model have been reported.19–23 In our previous research using the flow model to shape the OT practice, although the occupational therapist judged the activity to be suitable for the clients, clients themselves felt that the activity made them feel anxious, bored and apathetic.9

We believe that more effective OT and realisation of meaningful activities for clients could be provided by adjusting the challenge–skill balance. Therefore, we invented a new process called adjusting the challenge–skill balance for OT (ACS-OT). A randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted using ACS-OT for the elderly in an adult day programme showed improvements in health-related quality of life (QOL).24 However, this previous research only tested one activity, which limits the generalisation of the effect of ACS-OT on the larger population and to different activities. Therefore, we propose to examine the effect of ACS-OT on clients in the recovery phase who need timely support on activities of daily living (ADL) and occupational performance necessary to return to their home life. To test this, we plan to employ ACS-OT in the recovery rehabilitation unit of Harue Hospital, Fukui, Japan and to determine a protocol for RCT implementation.

Method and analysis

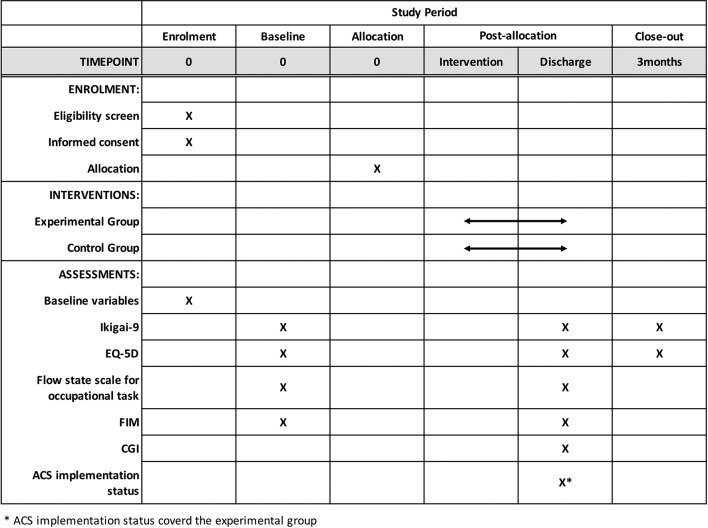

This study was designed as a single-blind RCT, this protocol will be reported according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) statement25 and the results of this trial will be reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines.26 This study is planned to compare ACS-OT with standard OT (control). To minimise heterogeneity of the client sample, we will test clients aged 50–99 years admitted to the recovery rehabilitation unit. This age range was chosen as the average age of patients admitted is 76.8±12.7 years, and we extended the target age range to ±2 SDs. As discussed in a previous review,27 this study represents the practice of client-centred OT, focusing on ADL and occupational performance. To determine if ACS-OT could be effective with various diseases, we targeted cerebrovascular and musculoskeletal diseases, which are the main diseases observed at our recovery rehabilitation unit. The average admission period in this unit is 8–10 weeks for cerebrovascular disease and 6–8 weeks for musculoskeletal disease. The intervention period in this study is set to 6–10 weeks, and the number of interventions would be 36–60. The primary outcome measure will be change in subjective QOL, which will be compared between the experimental and control groups. The secondary outcome measure will be change in flow experience, health-related QOL and performance of ADL. A SPIRIT diagram detailing the timing of enrolment, interventions and assessments is provided in figure 1.

Figure 1.

SPIRIT diagram describing schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments. ACS, adjusting the challenge–skill; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimensions; FIM, Functional Independence Measure; SPIRIT, Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

Feasibility of recruitment and sample size

We conducted an a priori power analysis (using G*power, V.3.1.7)28 that assumed a medium-to-large effect size based on the results of a previous RCT in the field of OT with an effect size of 0.76.24 The analysis indicated that a total sample size of 68 clients (34 in each group) would provide 80% power for detecting a difference, with an effect size of 0.7 for health-related QOL scores using a two-tailed test and an alpha level of 0.05. To compensate for client drop-out, we will recruit 80 clients. We aim to finish this recruitment in one year.

Randomisation

Clients will be randomly assigned by blocked randomisation (block size four) to the experimental or control groups. As the factors within the experimental and control groups affecting the outcome measures are homogeneous, randomisation will be stratified by the disease group (cerebrovascular/musculoskeletal disease) and a Visual Aanalogue Scale (VAS) for self-assessment of general health in EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) (EQ-VAS (high/low, boundary 50))29 will be used, resulting in four layers: (1) cerebrovascular disease and high EQ-VAS, (2) cerebrovascular disease and low EQ-VAS, (3) musculoskeletal disease and high EQ-VAS and (4) musculoskeletal disease and low EQ-VAS. Block order will be randomly assigned using computer-generated software (R. V.3.2.1). Our statistician will create a block random pattern of each layer, but the grouping will be single blinded. On the basis of the calculated random pattern, the assignment will be known to the occupational therapist. We intend to individually randomise patients in this research, and we use a dedicated process support application in the experimental group, but not in the control group. Therefore, there is almost no possibility of contamination between the two groups. The clients will be blinded to group allocation, although the therapists will be aware of the treatment group assigned. After the last outcome measurement point, each client will be asked to guess their assigned group.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for this study will be clients with cerebrovascular or musculoskeletal disease admitted to the recovery rehabilitation unit of the Harue Hospital, Fukui, Japan. Clients aged <50 years and >100 years at the time of their admission to the unit will be excluded from the study. In addition, clients whose Mini-Mental State Examination score is assessed as ≤23 points at their first OT appointment after admission to the unit will be excluded from the study.30 The exclusion criteria are transfer of the patient to another unit, another hospital or death.

Patient and public involvement statement

The clients will be not involved in the recruitment to and conduct of this study. We have designed the study to minimise client time and physical restrictions; all participants are free to withdraw from the study at any time. Structural evaluation on client’s burden in RCTs will be not performed. We will inform the results to the applicants.

Procedure

Intervention

In the experimental and control groups, OT will be provided in accordance with the American Occupational Therapy Association guidelines.31 The study intervention will be implemented by occupational therapists who have at least 200 work hours of experience in delivering treatment according to client-centred OT. Moreover, therapists will be trained for at least 50 hours on ACS-OT. The standard OT programme will focus on the occupational performance of activities and be conducted individually with each client. Treatment will consist of 40–60 min sessions, conducted six times per week. The implementation period will be from admission to discharge.

Experimental group

In the experimental group, we used our own custom application programme designed to run on a mobile device to control the following processes.

During the first session of OT, the therapist will assess the client’s problems with ADL using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure.32 Based on the problems identified, activities that could be supported by OT will be identified.

During the second session, the client will perform the selected activities and will be invited to evaluate the activities using the challenge and skill levels assessment. The ‘challenge level’ will be defined as the client’s perception of the level of difficulty associated with the activity and will be rated on a seven-point scale from ‘very simple’ (1) to ‘very difficult’ (7). The ‘skill level’ will be defined as the client’s perception of their own skills in relation to the activity and will be rated on a seven-point scale from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘very skillful’ (7).33 34 At that time, the therapist will clarify with the client regarding reasons for their challenge and skill-level ratings.

Based on the client’s and therapist’s evaluations, the factors which make the client’s occupational performance more difficult (challenge components, such as environment, execution time and movement range required for activity) and factors that improve their occupational performance (skill components, such as frequency, range, distance, accuracy and dexterity) will be determined. In the experimental group, the compensation approach, such as environmental adjustment and use of technical aid, will be used for adjusting the challenge level.

Based on these components and traditional assessment and activity analysis, the occupational therapist will reconfigure the activity contents after ACS process. The criteria for judging that the challenge–skill balance has been adjusted is defined in terms of the difference between the ‘challenge level’ and ‘skill level’ set by occupational therapist and client, which is 1 or less, respectively. For example, regarding activity on bathing, if the occupational therapist evaluates challenge level to 4, skill level to 5 and the client himself evaluates challenge level to 4, skill level to 4, we judge that it is adjusted. If the occupational therapist evaluates challenge level to 4, skill level to 4, and the client himself evaluates challenge level to 4, skill level to 2, it judges that it is not adjusted.

After the client has performed the adjusted activities, the client’s challenge–skill levels will be re-evaluated. When the client’s challenge–skill levels are determined to be balanced, interventions centred on the improvement of performance of the activities will commence. If the client’s challenge–skill levels are not balanced, the activities will then be readjusted, and the intervention will start once the levels are balanced. The intervention will aim to improve the client’s skill levels on the activities once their challenge–skill levels have been balanced.

This reassessment process will occur at least once a week.

Control group

For the control group, the first and second sessions will be conducted similar to that conducted for the experimental group, except that the therapists will not be informed of the client’s subjective perception of the challenge and skill levels for the activities. From the third session onwards, the therapists will simply assess the client’s performance and conduct the therapy in a manner typical of OT, following the general guidelines for OT practice.

Outcomes

Outcomes will be measured at entry (pre) and discharge from the unit (post) and at 3 months afterwards (follow-up). The primary outcome measure will be subjective QOL. All outcomes to be measured are listed below:

Subjective QOL (pre, post and follow-up)

Ikigai-9 is a self-assessed psychological instrument for measuring an individual’s mental state (reason for living; ikigai) and QOL.35 It comprises nine items; a total score (9–45 points) and three subscale scores (of 15 points each) are calculated.

Health-related QOL (pre, post and follow-up)

Health-related QOL will be assessed using the EQ-5D. The EQ-5D defines health-related QOL with five dimensions: mobility, self-care, day-to-day activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety or depression.29 The EQ-5D also has a VAS scale that enables self-assessment on a scale from 0 (worst possible health) to 100 (best possible health).

Flow experience (pre and post)

Flow experience will be assessed using the Flow State Scale for occupational tasks,36 developed for clinical situations. Since the Flow State Scale for occupational task in this study is to be carried out for occupational therapy in the recovery rehabilitation unit, this evaluation is not carried out at follow-up (after discharge). This consists of 14 items and 3 factors. The items were measured on a seven-point scale ranging from ‘strong disagreement’ (1) to ‘strong agreement’ (7), with possible scores ranging from 7 to 98.

Activities of daily living (pre and post)

ADL will be measured using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM).37 FIM is assessed by occupational therapist during admission to the recovery rehabilitation unit, and not implemented at follow-up. FIM is an 18-item, 7-level scale that uniformly assesses the severity of an individual’s disability and medical rehabilitation functional outcome. The range of values for FIM is from 18 (dependent) to 126 (fully independent).

Clinical Global Impression (post)

The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) rating scales are measures of overall treatment improvement. CGI is rated on a seven-point scale, with the severity of illness scale using a range of responses from 1 indicating ‘very much improved’ to 7 indicating ‘very much worse’.38 CGI is used for determining the minimally important change (MIC)39 in the main outcome (QOL).

ACS implementation status for occupational therapy (post)

Evaluation of ACS implementation status will be conducted by the occupational therapists. This evaluation method was prepared for this research to verify whether the experimental process is feasible. This evaluation is rated on a seven-point scale from ‘very poor’ (1) to ‘excellent’ (7) and consists of the following three items: (1) Whether differences in recognition between the client and the therapist were confirmed, (2) whether differences in recognition between the client and the therapist were adjusted during OT and (3) whether OT suitable for the client was provided. The occupational therapist will fill out this evaluation following each interventional session with a client.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses will be performed using SPSS V.24.0 for Macintosh. Data will be de-identified and entered into Microsoft Excel 2016 and subsequently exported into SPSS software for analysis. The analysis will be performed by the statistician who will be blinded to the random group assignments. The chief researcher will have access to the final trial dataset. Baseline characteristics of the groups will be compared using χ2 and independent samples t-tests for the categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U test will be used for assessing baseline continuous variables. Primary analysis for this study will be performed using intention to treat principles.

Linear mixed model

Each continuous outcome variable will be analysed using a linear mixed model (LMM) fitted with a maximum likelihood estimation. We will assign the following fixed effects: group (experimental or control group), time (pre, post or 3-month follow-up), and the interaction of group and time. In addition, we will include the participants as a random effect. All participants who provided baseline data are included in the analysis. LMM is an appropriate statistical method for longitudinal design studies with missing data in clinical trials.40 All confidence intervals will be provided with 95% margins. For all tests, a two-sided significance level of p<0.05 will be used. Between-groups effect sizes will be calculated as standardised mean differences.

Minimal importance change

MIC for each outcome will be calculated using the anchor-based method.41 The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve will identify the cut-off point on CGI scores that most optimally distinguishes between CGI scores of minimal improvement (1–3) and scores of no difference (4–7). The cut-off will be used to provide an MIC estimate that will maximise the Youden’s J statistic: sensitivity − (1–specificity).42 On the other hand, since there are few possibilities of deteriorating in the recovery rehabilitation unit, there is a possibility of adopting a method that uses MIC as each outcome mean value of the client who evaluated CGI as 3 (slightly improved).43

Cost-effectiveness

A cost-effectiveness analysis will be performed using the total cost and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) based on the index value of EQ-5D. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) will be calculated based on comparisons of the experimental and control groups. The total cost will be converted into US$ using the average currency exchange rate at the time of data analysis. ICER will be estimated using the following equation:

ICER=(μCe−μCc)/(μEe−μEc) where μC and μE represent the mean cost and mean QALY for the experimental and control groups, respectively. To account for uncertainty of ICER, the bootstrap method (1000 times) will be used for calculating mean values.44

Ethics and dissemination

All recruited clients will need to provide written informed consent. The study results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications.

Discussion

This research protocol proposal was prepared to examine the effect of ACS-OT on subjective QOL of clients in a recovery rehabilitation unit as an RCT. The process to be used in this study was devised based on the flow model and shares the perception of activities between the client and occupational therapist. Also, this process highlights the importance of provision of appropriate activities for clients. The client’s perception of their challenge–skill balance is highly relevant to the degree of difficulty and occupational performance of activities provided by OT. We believe that understanding the client’s subjective assessment of their activities according to their challenge–skill balance supports effective OT.

A previous RCT that used a similar protocol for older adults in an adult day programme observed improvements in health-related QOL.24 However, only one activity was examined and a follow-up period was not set. The current proposal will cover several activities such as toilet, bathing, cooking, shopping in which clients would require assistance during admission to a recovery rehabilitation unit. Furthermore, by setting a follow-up period, we will verify the continuity of the effect in addition to the direct effect of ACS-OT implementation. We hypothesise that ACS-OT will enhance the effects of positive emotions and self-affirmation by facilitating activities suitable for clients. As such, subjective QOL (according to the Ikigai-9) is the main outcome. Importantly, this suggests that improvements in OT yield new findings on subjective QOL. In addition, using a LMM, it will be possible to perform an analysis that considers individual differences as a random effect.

Study limitations

Subjective evaluations, such as subjective QOL, health-related QOL and flow experience, are highly likely to result in measurement bias. To address this, we will adopt an RCT design and perform self-assessed outcome measurements. In addition, there is a blinding problem in this RCT as the investigators in this study are occupational therapists, and thus, it will be difficult to blind occupational therapists to their assignment and intervention method.

We will use a convenience sample from the recovery rehabilitation unit of a single hospital, which may not be representative of all clients in a recovery rehabilitation unit. This study will not include patients with acute or subacute diseases, outpatients and clients who use community rehabilitation services. Therefore, our results cannot be generalised to these populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the clients who participated in our research. In addition, we appreciate the clients and public consultants who advised on research subjects, research designs and outcome measures.

Footnotes

Contributors: IY conceived and designed the experiments. IY performed the experiments. IY and KH analysed data. IY drafted the paper. KH and RK made further reviews as well as modifications. RK is also responsible for managing voluntarily reported adverse events from clients and other unintended effects of the intervention. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Japanese Association of Occupational Therapists, grant number 2017-04.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This protocol has been approved by the ethics review committee of the Tokyo Metropolitan University (No.17020).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Client centered occupational therapy. Law MC, Slack Incorporated, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Individuals in context. In: Fearing VG, Clark J, A practical guide to client-centered practice. Slack Incorporated. Eds, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Townsend E, Wilcock AA. Occupational justice and client-centred practice: a dialogue in progress. Can J Occup Ther 2004;71:75–87. 10.1177/000841740407100203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sumsion T, Law M. A review of evidence on the conceptual elements informing client-centred practice. Can J Occup Ther 2006;73:153–62. 10.1177/000841740607300303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Whalley Hammell KR. Client-centred occupational therapy: the importance of critical perspectives. Scand J Occup Ther 2015;22:237–43. 10.3109/11038128.2015.1004103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Atchley RC. A continuity theory of normal aging. Gerontologist 1989;29:183–90. 10.1093/geront/29.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Atchley RC. Continuity and adaptation in aging: creating positive experiences. Johns Hopkins University Press 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maitra KK, Erway F. Perception of client-centered practice in occupational therapists and their clients. Am J Occup Ther 2006;60:298–310. 10.5014/ajot.60.3.298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoshida I, Mima H, Nonaka T, et al. Analysis of subjective evaluation in occupations of the elderly: A study based on the flow model (in Japanese). J of Japanese Occupational Therapy Association 2016;35:70–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vallerand RJ, O’Connor BP. Motivation in the elderly: a theoretical framework and some promising findings. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne 1989;30:538–50. 10.1037/h0079828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krause N. Stressors in salient social roles and well-being in later life. J Gerontol 1994;49:P137–P148. 10.1093/geronj/49.3.P137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Csikszentmihalyi M. Play and intrinsic rewards. Jof humanistic psychology 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Optimal experience. : Csikszentmihalyi M, Csikszentmihalyi IS, Psychological studies of flow in consciousness: Cambridge university press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haworth J, Evans S. Challenge, skill and positive subjective states in the! daily life of a sample of YTS students. J Occup Organ Psychol 1995;68:109–21. 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1995.tb00576.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nielsen K, Cleal B. Predicting flow at work: investigating the activities and job characteristics that predict flow states at work. J Occup Health Psychol 2010;15:180–90. 10.1037/a0018893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Larson E, von Eye A. Beyond flow: temporality and participation in everyday activities. Am J Occup Ther 2010;64:152–63. 10.5014/ajot.64.1.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rebeiro KL, Polgar JM. Enabling occupational performance: optimal experiences in therapy. Can J Occup Ther 1999;66:14–22. 10.1177/000841749906600102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wright JJ, Sadlo G, Stew G. Further explorations into the conundrum of flow process. J Occup Sci 2007;14:136–44. 10.1080/14427591.2007.9686594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirao K, Kobayashi R, Okishima K, et al. Flow experience and health-related quality of life in community dwelling elderly Japanese. Nurs Health Sci 2012;14:52–7. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00663.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yasunaga M, Kobayashi N, Yamada T. The challenge skill ratio of users’ experiences at an adult daycare center: Emotional states based on the Flow model (in Japanese). J of Japanese Occupational Therapy Association 2012;31:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Massimini F, Csikszentmihalyi M, Carli M. The monitoring of optimal experience. A tool for psychiatric rehabilitation. J Nerv Ment Dis 1987;175:545–9. 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moneta GB, Csikszentmihalyi M. The effect of perceived challenges and skills on the quality of subjective experience. J Pers 1996;64:275–310. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Novak TP, Hoffman DL. Measuring the flow experience among web users. Interval Research Corporation 1997;31:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoshida I, Hirao K, Nonaka T. adjusting challenge-skill balance to improve quality of life in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Occup Ther 2018;72:1–8. 10.5014/ajot.2018.020982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Japanese Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2017;45:1895–904. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:726–32. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schiavi M, Costi S, Pellegrini M, et al. Occupational therapy for complex inpatients with stroke: identification of occupational needs in post-acute rehabilitation setting. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40:1026–32. 10.1080/09638288.2017.1283449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Erdfelder E, Faul F, Buchner A. GPOWER: a general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 1996;28:1–11. 10.3758/BF03203630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anthony JC, LeResche L, Niaz U, et al. Limits of the ‘mini-mental state’ as a screening test for dementia and delirium among hospital patients. Psychol Med 1982;12:397–408. 10.1017/S0033291700046730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process. 3rd edn: American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2014:S1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Law M, Baptiste S, McColl M, et al. The canadian occupational performance measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 1990;57:82–7. 10.1177/000841749005700207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R. Being adolescent: Conflict and growth in the teenage years Basic Books. 1986.

- 34. Engeser S, Rheinberg F. Flow, moderators of challenge-skill-balance and performance. Motivation and Emotion 2008;32:158–72. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Imai T. [The reliability and validity of a new scale for measuring the concept of Ikigai (Ikigai-9)]. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2012;59:433–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yoshida K, Asakawa K, Yamauchi T, et al. The flow state scale for occupational tasks: development, reliability, and validity. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy 2013;23:54–61. 10.1016/j.hkjot.2013.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Keith RA, et al. Advances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitation. Top Geriatr Rehabil 1986;1:59–74. 10.1097/00013614-198604000-00007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guy W. Clinical global impression scale. The ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology-Revised Volume DHEW Publ No ADM 1976;76:218–22. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR. Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:395–407. 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00044-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shek DT, Ma CM. Longitudinal data analyses using linear mixed models in SPSS: concepts, procedures and illustrations. ScientificWorldJournal 2011;11:42–76. 10.1100/tsw.2011.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. de Vet HC, Ostelo RW, Terwee CB, et al. Minimally important change determined by a visual method integrating an anchor-based and a distribution-based approach. Qual Life Res 2007;16:131–42. 10.1007/s11136-006-9109-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950;3:32–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Kampen DA, Willems WJ, van Beers LW, et al. Determination and comparison of the smallest detectable change (SDC) and the minimal important change (MIC) of four-shoulder patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). J Orthop Surg Res 2013;8:40 10.1186/1749-799X-8-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Briggs AH, Wonderling DE, Mooney CZ. Pulling cost-effectiveness analysis up by its bootstraps: a non-parametric approach to confidence interval estimation. Health Econ 1997;6:327–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.