Abstract

Exercise is effective in preventing falls amongst older adults. However, few studies have included people living with dementia and their carers and explored their experiences. The aim of this paper is to explore what affects the acceptability of exercise interventions to better meet the needs of people with dementia and their carers as a dyad. Observations, field notes containing participants and instructor’s feedback, and focus groups with 10 dyads involved in Tai Chi classes for 3 or 4 weeks in two sites in the South of England were thematically analysed to understand their experiences. Findings suggest that dyads’ determination to achieve the benefits of Tai Chi facilitated their adherence, whereas a member of the dyad’s low sense of efficacy performing the movements during classes was a barrier. Simplifying class content and enhancing the clarity of instructions for home-based practice will be key to support the design of future exercise interventions.

Keywords: exercise, qualitative, dyad, community-dwelling, falls

Dementia is estimated to affect 46.8 million people worldwide (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2015), with advancing age being an important contributor to its prevalence (WHO, 2015). Due to increasing life expectancy and the resultant increase in the number of individuals with dementia this has become a matter of concern (WHO, 2012). The progression of dementia has an increasing impact on the individual’s cognitive and physical performance, ultimately resulting in more dependency towards their informal caregivers (Alzheimer's Society, 2015). This increase in dependency not only impacts on the person but also on the informal carer (henceforth “carer”) and wider family and friends potentially affecting social, health and financial circumstances (Alzheimer’s Research UK, 2015).

Falls have an additional and direct impact on an individual’s autonomy and quality of life (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013). A variety of interventions (including Vitamin D supplementation, exercise, environmental, and multifactorial interventions) have been attempted to reduce the risk factors for falls amongst older people living in the community. Exercise, including Tai Chi, and home safety interventions have been effective in reducing the risk of falls (see Gillespie et al., 2012). In most of these studies, however, people living with dementia have been excluded even when they are more likely to experience a fall (Shaw, 2003). However, when people living with dementia in the community have been included, exercise related activities have been shown to be potentially useful for this purpose reducing around one third the risk of falling (Burton et al., 2015). Tai Chi in particular shows promise for preventing falls among people living with dementia (Nyman & Skelton, 2017). However, there is a lack of high quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with blinded assessors that focus on exercise, including Tai Chi, among community dwelling older people living with dementia and their carer as a dyad.

Exercise interventions have been tested for their impact on behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia, as well as on physical and cognitive function (i.e., Fleiner, Dauth, Gersie, Zijlstra, & Haussermann, 2017; Hamilton et al., 2017; Öhman et al., 2016). However, recent systematic reviews of such studies have identified inconsistent results due to differences in settings (i.e., community vs long term care), exercise types (i.e., using one or different type of exercises as well as exercise alone or in combination with other interventions), and doses (Abraha et al., 2017; Laver, Dyer, Whitehead, Clemson, & Crotty, 2016; Rao, Chou, Bursley, Smulofsky, & Jezequel, 2014; Öhman, Savikko, Strandberg, & Pitkälä, 2014). Lessons learnt from previous exercise interventions involving community dwelling people living with dementia suggest that uptake facilitators are health care professionals’ advice (Chong et al., 2014; Suttanon et al., 2012), the provision of enough detailed information about the intervention (Frederiksen, Sobol, Beyer, Hasselbalch, & Waldemar, 2014), and the use of positive phrasing in recruitment materials (Hawley-Hague, Horne, Skelton, & Todd, 2016). Characteristics of the intervention such as a group-based format (Chong et al., 2014; Dal Bello-Haas et al., 2014; Hawley-Hague et al., 2016), the possibility of adapting the intervention to participants’ needs (Chong et al., 2014), affordability (Chong et al., 2014; Hawley-Hague et al., 2016), and the abilities of the instructors to create a bond with participants influence their perceived attractiveness of the intervention (Hawley-Hague et al., 2016). Participants’ characteristics also has an impact on acceptance in terms of personal motivations (Hawley-Hague et al., 2016), positive attitudes towards exercise (Chong et al., 2014; Suttanon et al., 2012) or the perceived benefits, including the value of research and the potential reduction of caregiver burden (Suttanon et al., 2012) and the expected impact on cognition (Chong et al., 2014).

Interventions designed to enhance well-being amongst people living with dementia and their informal carers are relatively recent (Van't Leven et al., 2013). Dyadic exercise interventions, where both the person living with dementia and the carer participate together, however, have been well received and feasible in the community (Chew, Chong, Fong, & Tay, 2015; Suttanon et al., 2013; Yao, Giordani, Algase, You, & Alexander, 2012; Yu et al., 2015). The involvement of both members has been found particularly relevant in exercise interventions to ensure safety and promote enjoyment (Dal Bello-Haas et al., 2014; Logsdon, McCurry, & Teri, 2005; Suttanon et al., 2012; Yao et al., 2012).

Tai Chi is a mind-body exercise originated from China and based on the Taoist Philosophy (Fetherston & Wei, 2011). Different styles of Tai Chi have been developed (i.e., Chen, Yang, Sun, Wu) keeping most of the essential principles, but adopting different characteristics (i.e., intensity) (Fetherston & Wei, 2011). Previous research suggests that Tai Chi could be as effective and cost-effective or more than alternative exercises targeting falls prevention amongst older people living with or without dementia; and could attract better adherence as a ‘normal’ activity practiced by people of all ages and not just frailer older adults (Nyman & Skelton, 2017). However, there is little research exploring the use of Tai Chi amongst people living with dementia in the community (Barnes et al., 2015; Burgener et al., 2008; Yao et al., 2012). Only Yao el al. (2012)’s pilot study (the most similar to our study, using an adapted simplified Yang Style form) used Tai Chi in isolation. In this study participants attended 100% of the group sessions; however, those were only delivered twice a week for 4 weeks, whereas 84% adhered to the home-practise component which lasted 12 additional weeks. In two other studies, adherence was around 72-75% to classes delivered 3 times a week over 18 or 40 weeks, but Tai Chi was not delivered in isolation which makes it difficult to differentiate what effects were due to Tai Chi (Barnes et al., 2015; Burgener et al., 2008). In all three cases as no qualitative methods were used, there is no way to explain the reasons for participants’ engagement or disengagement with Tai Chi.

An underuse of qualitative methods has generally been observed in RCTs of healthcare interventions (Drabble, O’Cathain, Thomas, Rudolph, & Hewison, 2014). While more recently some RCTs have incorporated a qualitative component in their evaluation, this has not been the case in feasibility studies (O’Cathain, Thomas, Drabble, Rudolph, & Hewison, 2013). To our knowledge, only one trial testing exercise in people living with dementia (Barnes et al., 2015) reported an amendment to their study protocol to implement qualitative data analysis, although results have not been reported to date. Acceptability has occasionally been reported by authors following their perceptions about participant´s satisfaction with interventions or providing participants’ anecdotal comments (e.g., Saravanakumar, Higgins, Van Der Riet, Marquez, & Sibbritt, 2014; Yao et al., 2012). The need to listen to participants’ opinions and perceptions regarding their involvement in Tai Chi interventions had already been highlighted (Saravanakumar et al., 2014), as it could help to understand the relevance of the intervention and identify ways of making it more appropriate for them. In this paper the acceptability of a Tai Chi intervention is explored using observational and focus groups data. This Tai Chi intervention is the Pilot Intervention Phase of the TAi ChI for people with demenTia (TACIT Trial). The aim of this study was to obtain information on the feasibility of a Tai Chi intervention for people living with dementia in the community, taking part together with an informal carer. The main objective was to identify any practical issues with the Tai Chi intervention that may reduce participants’ acceptability of the intervention. Sharing the lessons learnt in this study could facilitate people living with dementia and their carer’s adherence to Tai Chi and to similar exercise interventions designed for such dyads.

Methods

Prior to data collection for this study, ethical approval was received from NHS (IRAS Project ID: 209193) and the trial was registered (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT02864056).

Recruitment Strategy

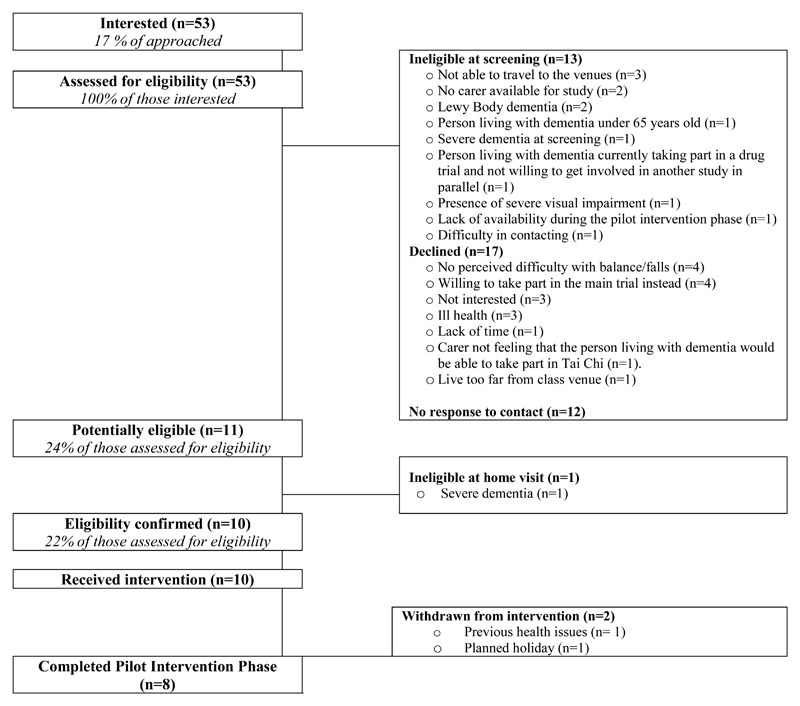

Recruitment took place between October and December 2016. Potential participants were initially identified and approached by three National Health Service (NHS) Trusts in the South of England, as well as by the research team using Join Dementia Research (JDR) website where people living with dementia can express their interest in taking part in research. Additionally, the study was advertised locally, allowing potential participants to contact the research team directly to express their interest in the study. Once participants made initial contact (or after referral) to the research team, further information about the study was posted or emailed to them. Recruitment materials included a Leaflet, a Key Facts Sheet and a Participant Information Sheet. These materials provided information regarding balance, falls prevention, Tai Chi and the implications of getting involved in the study for each member of the dyad. Confidentiality, voluntary participation, data protection and consent procedure were also described within the Participant Information Sheet. Potential participants were also provided with a visual representation of the different steps involved in the study. This study was presented as a falls prevention and balance improvement exercise, which was informed by the main outcome measures, and aim of the RCT. At least 48 hours after receiving this information an initial telephone screening was conducted to ascertain eligibility. A total of 53 people were contacted by the research team and of these 10 dyads (instead of 14 initially planned at this stage) were successfully recruited into the study (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant recruitment.

Participants

Demographic characteristics of participants included in the study are provided in Table 1. The inclusion criteria for participants were: A diagnosis of (mild-to moderate) dementia, be aged 65 years or older, live in their own home, be able to practice standing Tai Chi and have a carer available who would provide support during the assessments and at home and during the group-based Tai Chi classes. The exclusion criteria were: People with Lewy Body dementia or Parkinson’s disease, receiving end of life care, those with severe dementia symptoms according to the The Mini-Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (M-ACE) (Hsieh et al., 2015) (cut off point M-ACE <15) or sensory impairments, those already practising Tai Chi or who would not be able to attend weekly classes. However, after finishing the Pilot Intervention Phase, on re-analysis of M-ACE scores it was revealed that three participants included in this phase of the study were in fact ineligible (scores between 10-15), which was reported to the Sponsor. Nevertheless, all of the participants were able to take part in the classes and provide feedback and no one was put at risk from participating in the study. A subsequent request was sent to the Research Ethics Committee to lower the M-ACE threshold score to 10 or above for the next phase of the study, which was approved.

Table 1. Baseline Demographic Characteristics.

| Participant | Item | Frequencies or means (Standard Deviations (SD)) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 (n=4) | Site 2 (n=6) | Total | ||

| People Living With Dementia | Gender | |||

| Male | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Female | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Mean age (SD) | 73.75 (0.96) | 81.17 (5.04) | 78.20 (5.39) | |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married / Civil partnership | 3 | 5 | 8 | |

| With partner | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Widowed | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Current living situation | ||||

| Living with family/friends | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Secondary | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Higher education college / university | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Further education / professional qualification | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Dementia type | ||||

| Alzheimer’s | 3 | 6 | 9 | |

| Mixed Alzheimer's & Vascular | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mean number of months diagnosed with dementia (SD) | 21 (22.23) | 25.67 (28.56) | 23.80 (24.97) | |

| Other chronic conditions | ||||

| Yes | 3 (Glaucoma, high pressure and headache/hypertension/sarcoidosis1) |

4 (Fibromyalgia2 and stroke/prostate cancer and diverticulitis3/neuralgia4/hypertension) |

7 | |

| No | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Uses a walking aid? | ||||

| No | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Mean prescribed daily medications (SD) | 3.5 (1.29) | 5.5 (4.32) | 4.7 (3.47) | |

| Falls in the last year? | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 1 (minor injury) | 1 | |

| No | 4 | 5 | 9 | |

| Falls in the last month? | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 1 (minor injury) | 1 | |

| No | 4 | 5 | 9 | |

| Frequency of moderate PA practise | ||||

| Everyday | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 3 times per week | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 times per week | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Weekly | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Rarely/never | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Frequency of vigorous PA practise | ||||

| Monthly | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Rarely/never | 3 | 6 | 9 | |

| People Living With Dementia | Previous experience practising Tai Chi? | |||

| No | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Mean confidence about being able to practise Tai Chi for at least 20 minutes per day (SD)5 | 1.75 (0.96) | 2.67 (1.21) | 2.3 (1.16) | |

| Mean intention to practise Tai Chi for at least 20 minutes per day (SD)6 | 2.25 (0.96) | 2.17 (0.75) | 2.2 (0.79) | |

| Carers | Gender | |||

| Male | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Female | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| Mean age (SD) | 69.25 (1.5) | 74.5 (5.96) | 72.40 (5.28) | |

| Relationship with the person living with dementia | ||||

| Spouse/partner | 4 | 5 | 9 | |

| Other | 0 | 1 (niece) | 1 | |

| Live with the person living with dementia | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married / Civil partnership | 3 | 6 | 9 | |

| With partner | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Current living situation | ||||

| Living with family/friends | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Secondary | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Higher education college/university | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Further education/professional qualification | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Previous experience practising Tai Chi? | ||||

| No | 4 | 6 | 10 | |

| Mean confidence about being able to practise Tai Chi for at least 20 minutes per day (SD)5 | 1.33 (0.58) | 1.17 (1.17) | 1.89 (1.05) | |

| Mean intention to practise Tai Chi for at least 20 minutes per day (SD)6 | 1.33 (0.58) | 2 (1.1) | 1.78 (0.97) | |

Sarcoidosis is a disease “characterized by the formation of immune granulomas” in any organ affected (Strookappe et al., 2015, p. 701). If present, symptomatology generally disappears spontaneously or with adequate treatment without further consequences for the patient (Judson, 2015).

Fibromyalgia is a syndrome characterised by chronic “widespread pain” and possibly other physical (i.e., “muscle stiffness”) and psychological (“memory and concentration” difficulties) manifestations (NHS, 2016).

Diverticulitis is an infection caused by bacterial accumulation in “small bulges that stick out of the side of the large intestine” which is generally cured after dietary, pharmacological or (rarely) surgical intervention (NHS, 2014).

Neuralgia is the pain caused by nerve irritation or damage (Shelat, 2016).

Participants were asked to rate their confidence using a Likert scale from 1 (true) to 7 (false), where 1 was the best score –showing participants’ confidence about being able to practise for 20 minutes per day.

Participants were asked to rate their intention using a Likert scale from 1 (likely) to 7 (unlikely), where 1 was the best score –showing participants’ intention to practise for at least 20 minutes per day.

Procedure

The ten dyads recruited were split in two groups, according to their proximity to the venues. In Site 2 participants were invited to attend 4 classes (once a week) and practise at home for 20 minutes a day for 3 weeks as planned. The length of classes and home practice was set up to imitate the Trial Phase of the study where participants would be encouraged to do so to build up over 50 hours of exercise dose (Sherrington et al., 2008). Due to the slower recruitment and restricted time-frame, however, participants in Site 1 were invited to join the study for 3 weeks only and an extension was not offered. As the aim of this study was to obtain qualitative feedback on the experiences of participants to help develop the RCT phase, the impact of participants receiving 3 or 4 classes on research outcomes was not measured. The classes were to run over 4 weeks to allow the study of the acceptability of the classes, the home-visit conducted by the instructor, the home-based practice and the data collection methods used during dyad’s involvement in the study in the short term.

The Tai Chi course was specifically designed and made simple for people to follow, including several repetitions of the movements both in and between classes (during home-practice). Corrections were given to all in class, without excluding any participant, and providing an explanation regarding the importance of ensuring a safe practice. Health and safety protocols were put in place to guide the instructor on what to do in the event of a fall during a class and to allow the instructor know about participants’ health conditions before the first class. Classes were led by a professionally trained Tai Chi instructor with experience of working with older participants living with and without dementia. Both pilot groups were led by the same instructor. Venues were chosen after checking their suitability against various criteria: Size (able to accommodate between 14-20 people), maintenance conditions, accessibility by car and/or public transport, time slots availability, flexible booking, availability of onsite kitchen facilities and general accessibility within the venue (i.e., lifts and toilets).

Both venues were spacious, had well maintained wooden floors, heating systems, and used a combination of natural and artificial lighting. Classes were delivered during working days around midday on a weekly basis, following advice from the Public and Patient Involvement (PPI) advisory group that was involved in the TACIT Trial’s design (see Appendix A for a description of this meeting). Participants were asked to arrive 10 minutes before the scheduled time of the class, take part in 45 minute Tai Chi classes and engage in conversation for 45 minutes after the Tai Chi class over a cup of tea/coffee and cake. Every session therefore required participants’ involvement for up to 90 minutes. Before starting each class, participants had the chance to talk to other participants and the instructor. During the classes participants generally practised in silence and with no or only occasional verbal guidelines from the carer to the person living with dementia. Participants were expected to stand for the duration of the class to challenge their balance, but they were free to sit before and at the end of the session. Each class had the same structure formed by warm-ups, patterns, relaxation and socialising. Classes consisted of copying the instructor’s movements. Each pattern (formed by several movements) was slowly repeated two or three times by the instructor, depending on dyads’ performance, whilst participants mirrored him. Participants responded mostly non-verbally (i.e., with laughs) to the instructor’s jokes and interactions. Only in a few occasions there was a verbal interaction between dyads and with the instructor. Classes developed in a friendly and relaxed atmosphere, where participants kept mostly focused on the instructor and received regular positive feedback. After the classes participants interacted with each other and with the instructor whilst enjoying some refreshments.

Additionally, dyads were asked to practise Tai Chi at home for 20 minutes a day after the first class. Participants were told that they could compensate their practise over the week (i.e., one day practice 30 minutes instead, and the next only 10; or split their 20 minutes practice in 2 slots of 10 minutes if this could fit better in their routines). A booklet was provided to act as a prompt for participants’ home practise, reminding participants how to perform the movements. This booklet contained several pictures of each pattern, supported by explanatory text below each picture.

Dyads were supposed to receive a home-visit from the instructor during the second week of their participation in the study to ensure a safe practice at home and complete an action and a coping plan. However, in practice, only 6 out of 10 received this visit due to time constraints and various reasons. One of the dyads withdrew from the intervention after the first class; a second dyad joined the group a week later and the home-visit had to be postponed because of the person living with dementia not feeling well, but then was never rescheduled because was ill for the rest of her participation in the study. For the other two dyads, their location was quite far from the Instructor’s and they were not able to arrange a suitable time for both to meet. A non-compliance report was filled for this and sent to the Sponsor. Nobody was injured during home-practice and from this experience we learnt that for the future Trial Phase of this study, classes lead by the same instructor would need to start at least two weeks apart and home-visits would only take place after the two first weeks of class practice. This way we could ensure enough time for the instructors to conduct these home-visits without fail. Additionally, information given to the participants has been revised to make clear there is to be no home-practice until the home-visit is made. Although four dyads did not receive the intervention fully as per the protocol, they were not exposed to undue risk given the very safe intervention they are being asked to do (Tai Chi) in their home environment that they are very familiar with. We have not had any experience of there being any risks to account for in any of the home visits in the Pilot Intervention Phase or the ones conducted so far during the RCT phase.

The action plan was introduced to identify a suitable time for home-practice and the coping plan to develop strategies to overcome possible barriers to home-practice (Chase, 2015). Action and coping plans are techniques used to facilitate behaviour change (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014), in this study to facilitate participants’ practice of Tai Chi at home. The action plan is the document where both members of the dyad specify which days of the week, at what times (morning/afternoon/evening), for how long, where specifically and with whom will they practise Tai Chi. The coping plan is the document where both members of the dyad identify the anticipated barriers for practising Tai Chi at home. For each barrier anticipated, they are requested to provide a way of overcome it and keep to the plan.

During the study period, one dyad from each Site withdrew from the intervention (20% withdrawal rate). Both dyads, however, decided to carry on providing research data. As reflected in Table 2, six dyads attended all the classes offered and only one dyad attended less than 50% of the classes (33%).

Table 2. Dyads’ Attendance to the Classes in the Pilot Intervention Phase.

| Dyads | Class number | Totals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | Classes attended per dyad | Dyads' average attendance | Groups' average attendance | |

| 01001 | Yes | Withdrawn1 | Withdrawn | N/A | 1 | 33% | Site 1 75% |

| 01002 | Yes | No2 | Yes | N/A | 2 | 67% | |

| 01003 | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | 3 | 100% | |

| 01004 | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | 3 | 100% | |

| 02001 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | 100% | Site 2 83% |

| 02002 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | 100% | |

| 02003 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | 100% | |

| 02004 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | 100% | |

| 02005 | Yes | Yes | Withdrawn3 | Withdrawn | 2 | 50% | |

| 02006 | Not recruited | Yes | Yes | No4 | 2 | 50% | |

| Dyads attending each class | 9 | 8 | 8 | 4 | |||

Due to previous health issues.

Due to a traffic accident blocking traffic.

Due to planned holiday.

Due to illness.

Data Collection Process

Field notes were used during participants’ involvement in the classes to capture what was observed in the research context (Austin & Sutton, 2014; Patton, 2013) and to record participants and instructor’s feedback. During the classes, qualitative semi-structured observations were made over the two study sites following a semi-structured checklist template (see Appendix B for qualitative checklist). Each observation started with an initial description of the venue, participants’ interaction, and spatial distribution in the room. To capture changes within sessions, observations were split in three blocks (1st: 0-15 minutes; 2nd: 15-30 minutes; 3rd:30-45 minutes). The observational schedule captured examples of participants’ interactions, engagement (as interest and sustained attention) (Kinney & Rentz, 2005), attitudes towards Tai Chi, positive and negative affect (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988), communication (as expressions of pleasure, sadness, self-esteem, and normalcy) (Kinney & Rentz, 2005), and psychological needs satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Data collected by the researcher observing the sessions were quotes (where possible) or a description of what was happening in the intervention context. Sessions were not video or audio-recorded as the instructor opposed this. However, to ensure the appropriateness of the qualitative observation tool created for this study, two authors (first and last) took notes (following guidelines provided by the first author in an observational codebook) during sessions organised in Site 1, which were later compared to refine the observational data collection tool. At the end of each class, during the 45 minutes allocated to socialise, the first author interacted with the participants and the instructor individually and they provided their feedback about the session. This feedback was not audio-recorded but the researcher took notes whilst participants were providing their feedback or immediately after to avoid altering their accounts.

Focus group data were collected immediately after the last class (3rd or 4th depending of the Site), and both lasted around one hour taking place in the same venue as the Tai Chi class. All dyads attending the last class (n=7, 3 dyads in Site 1 and 4 dyads in Site 2) were involved in these focus groups. Two researchers facilitated each joint dyadic focus group (last and first authors in Site 1 and first and third in Site 2) and ensured the focus group schedule was followed. Topics covered included (see Appendix C for focus group schedule): Experience of taking part in Tai Chi classes and at home, their willingness to continue and their experience of taking part in research. This was audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim, to ensure the accuracy of participants’ accounts. First author attended all the sessions and was present in both focus groups. This researcher was in touch with participants weekly so they were sharing their experiences with a familiar person.

Ethical Issues

Due to the progressive nature of dementia process consent procedure was followed (Dewing, 2008), meaning that participants were verbally asked about their willingness to carry on taking part in the study at key points in the study, as well as the researcher looking for verbal cues that confirmed consent to participate.

During the data collection process participants were informed any data collected would be anonymised so their identities or any personal details would not be disclosed, participants’ non-verbal communication, particularly for participants living with dementia was checked during their interactions with the researchers. Participants provided informed consent to take part in the study and focus group during the baseline home-visit, when they were asked to summarise back to the researcher what the study was about and what they would be doing as part of their participation in the study to check their ability to provide informed consent. However, to ensure their willingness to continue taking part in the study, process consent was sought at each interaction with the researcher. This was also verbally checked before and after the focus group. Should any participant have declined to carry on with their participation in the study, up until the point when their data would have been anonymised, their data would have not been analysed. During the focus group, all participants were given an equal opportunity to share their experiences, with occasional direct invitations from the researcher to contribute to the conversation. To facilitate participants’ living with dementia’s involvement in the conversation, printed copies of focus group questions were provided in A4.

Data Analysis Strategy

Thematic analysis was used to identify common trends in systematic qualitative observations of the classes, field notes containing participants and instructor’s views during their involvement in the study and the content of the focus groups. Methodological (observation, feedback and focus group) and data sources (participants, instructor and researchers) triangulation were used to ensure credibility. Data were analysed together following the 6 steps described by Braun and Clarke (2013) for thematic analysis: a) Audio files from focus groups were professionally transcribed verbatim, double-checked and anonymised (UK Data Archive, N. D.); b) Reading and re-reading the transcripts to get familiar with the data; c) Coding all the data sets inductively, looking for salient units of meaning (Saldaña, 2016) in the manifest content expressed by participants, and developed a codebook with inclusion and exclusion criteria and examples for each code. A large number of codes were identified after this process and, after revision, very similar codes were merged; d) Themes were searched amongst the codes; e) Themes were reviewed to make sure they were representative of the codes contained; and f) Themes were defined and named. Data sets and the analytical process were managed using NVivo.11 (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2012). One author (first) coded the whole data set, and once the initial codes had been identified, and refined (merging very similar codes), a coding booklet was developed. This booklet was provided to the second author, who double coded 10% of each type of data collected to enhance rigour. Coding was compared to refine the coding framework.

Results

The intervention was well received by the majority of participants (9 out of 10 dyads) who expressed a willingness to carry on practicing Tai Chi after the study (see Table 1 for participants’ characteristics). The remaining dyad was unable to continue participating in the pilot and withdrew after the first class due to health issues.

Two main themes were identified: intervention’s characteristics and participants’ reactions to the intervention (as reported in Table 3). Direct quotes presented contain participant identification numbers and a “C” when mentioned by a carer or a “P” if was mentioned by a person living with dementia. An “O” indicates this was heard during an observation or observed and described by the researcher, “FG” in the context of a focus group, and “F” when providing feedback at the end of the class. A summary of barriers, facilitators and improvements suggested to enhance the acceptability of the intervention by participants, the instructor or the research team are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Barriers, Facilitators and Improvements Suggested to Increasing Participant’s Acceptability of Tai Chi.

| Theme / Subtheme | Facilitators | Barriers | Improvements suggested (by…) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions characteristics | |||

|

Instructional methods |

|

|

|

|

Class-based Tai Chi |

|

|

-

|

|

Home-based Tai Chi |

|

|

|

|

Participant’s reactions to the intervention | |||

|

Feelings towards the intervention and their dyadic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interaction with others |

|

- | - |

Direct quotes are coded with the participant number and a “C” if provided by a carer or a “P” if provided by the person living with dementia. An additional code is used to mark the context where data was collected: during observations (“O”), feedback provided at the end of the class (“F”), or during the focus group (“FG”).

Intervention’s Characteristics

All subthemes contained by this overarching theme relate to the way the intervention was: a) delivered by the instructor, including the way he engaged with participants, built rapport, reassured participants and tailored the intervention to meet participants’ needs; and b) practised by participants, in terms of class- and home-based Tai Chi practise.

Instructional methods

All participants valued the instructor (see Table 3 for example quotes). Both people living with dementia and their carers stated that they were able to understand him as he was using clear speech and a calm tone of voice. During the classes, the instructor made use of examples from his private life to create rapport with participants (i.e., sharing comments made by his daughter), but also used examples from everyday life to describe the movements during the classes (i.e., “is like drinking a cup of tea” (O)). He regularly provided positive feedback during the classes to encourage participants’ engagement in the activity and reassured the participants when they verbalised difficulties while doing Tai Chi at home or during classes. Sometimes this positive feedback was given when some participants were struggling to perform the movements or doing them incorrectly. This approach was chosen by the instructor for this study to facilitate their engagement and was positively perceived by one of the carers during a focus group:

when he's doing the exercises, he says, oh, that's good, yes, that's right, you're doing it right there, but…you know they're not really but… he's just encouraging (02001C-FG).

Corrections, however, were mostly made as a general comment not directed to individual participants (i.e., “golden rule: your knees very slightly bent go forward and your heels stay in the ground” (O)), unless participants had expressed a particular difficulty in performing a movement. The instructor reinforced participants’ home-practice by providing positive feedback (i.e., “I can see some of you have been practising” (O)).

The instructor adapted the intervention to participants’ needs and responded to their requests (i.e., introducing breathing while practising one movement, as requested by a carer during the class) to make the intervention accessible for both people living with dementia and their carers. He emphasised the need of participants to focus only on their own performance.

Class and home-based Tai Chi practice

Occasionally participants performed better when attempting a move for the second time during a class. However, more frequently participants (mostly people living with dementia) carried on practising the movement in the opposite direction, bending too much forward or pausing their engagement in the activity. During the first class participants living with dementia stood closer to their carers, however in the classes that followed three of the carers in Site 2 practised in front, leaving the person living with dementia to work individually behind them.

At home, eight out of ten dyads reported that they had managed to do some practice. Dyads who did not report any practice were the one dyad who withdrew after the first class and another dyad that attended all the classes but was not able to practice due to an unexpected lack of time.

Two carers verbalised their difficulties motivating the person living with dementia to do things, which had an impact on their home-practise meaning that they did not manage to do any practise or not more than 20 minutes during one week. However, only one participant living with dementia struggling to practice at home had experienced difficulties following the classes, instead focused on doing the warm ups (“you do get quite a bit of benefit in that” (02004C-FG), “But our warm-ups is Tai Chi in my mind” (02004P-FG)).

The lack of guidance and confidence when practising at home was the main issue raised by participant dyads. Particularly carers felt like the “blind leading the blind”, which led one of the carers to stop practising at home, whilst the person living with dementia carried on alone, convinced that any practice would be positive for her. The booklet in all the cases was perceived as not useful, unclear and with inconsistent (picture-description) instructions which failed to show the progression of the movements (see Table 3 for example quotes).

Participants’ Reactions to the Intervention

Subthemes contained by this overarching theme relate to the way participants responded to the intervention in terms of their: a) feelings toward the intervention and their dyadic participation; and b) interaction with others (see Table 3).

Feelings towards the intervention and their dyadic participation

Before starting the classes and after the first class half the dyads were particularly passionate and enthusiastic about the opportunity of taking part in Tai Chi, whereas the rest were more neutral in their behaviours and expressions. Generally, participants had neutral and positive feelings towards the intervention (“a good addition to my life” (02005P-F)). All participants shared their enjoyment of the intervention and the socialising component, when providing feedback (see Table 3 for example quotes). However, only occasionally they verbalised this satisfaction during the class (i.e., “I like it!” (01002P-O)). In site 2, participants expressed their content non-verbally at the end of the class by clapping the instructor.

Tai Chi was perceived as a different activity that participants were not familiar with, however, this had no impact on participants’ enjoyment and engagement in the activity (“It´s strange from another tasters that I went to, but I like it” (02003P-FG)). Tai Chi is an activity that carers see themselves doing with their partners to improve or maintain their physical condition unlike other types of exercise, and both enjoy doing.

Carers did not find their joint participation to be a burden. Only one expressed it had been hard as a carer although he would keep going for the person living with dementia and the possibility of meeting with other carers. Similarly, only one participant living with dementia seemed to react negatively towards the intervention, feeling “distressed before going” (02006C-F)) to the sessions as reported by the carer.

During the classes, all participants were focused in the session, looking at the instructor and copying his movements. Three participants expressed they had experienced difficulties following the classes after the first session, one due to their fear of falling and two because they struggled during sessions when copying more complicated patterns. It was clearly observed, however, that an additional participant, who did not report any difficulties, also struggled copying some of the movements. One of the participants living with dementia, on the contrary, according to the instructor and first author’s observations got more into the intervention and was able to follow the class without verbal prompting from the carer. Carers engaged in the intervention reported no difficulties in copying the movements during the classes. Generally, participants appear to enhance their perceptions of competence during sessions and with practice, feelings of the “flow” and getting other benefits of the intervention. Participants’ progress was already noticeable in the second class when half of the participants living with dementia and carers anticipated the movements taught by the instructor. Finally, three non-serious and non-severe, and expected adverse events experienced by participants were rated as definitely/probably/possibly related to the intervention: dizziness - reported by two participants living with dementia and pain -reported by a carer and attributed to previous conditions, which did not impact on their willingness to carry on practising Tai Chi.

The most important facilitators of participants’ engagement in the intervention were the benefits perceived by both members of the dyad after taking part in the intervention: a) relaxation; b) exercise for health benefits –increasing activity levels, keeping muscle supple; c) body awareness– “it makes you think about what’s going on in your body while you’re doing this” (01004P-FG); d) brain stimulation; and e) balance improvement. Taking part in the intervention was perceived as a source of pride in itself.

Interactions with others

During the classes, most of the interactions were initiated by the instructor as he was the one leading the session. However, participants reacted to the instructor’s comments frequently with smiles and laughs. In both sites only occasionally there was an interaction between members of the same dyad, for instance, in the form of non-verbal interactions expressing mutual understanding. When the carers started a verbal interaction this was always in a soft and comfortable way to ensure the person living with dementia was all right or to support the instructions provided by the instructor. At the end of the class participants were able to engage in informal conversation with other dyads and the instructor.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand what is influencing the acceptability of Tai Chi amongst people living with dementia and their carers and how this could be enhanced. Findings suggest that Tai Chi is perceived by people living with dementia of mild-to-moderate severity and their carers as an enjoyable activity that they can readily carry out together. Carers play a key role in supporting people living with dementia’s involvement in the classes and facilitating home-practice, therefore content and supporting materials must be carefully adapted so both members feel comfortable when practicing at home. Once incorporated in their routines, Tai Chi could be an enjoyable and mutually beneficial activity.

Caution is required in supporting the acceptability of Tai Chi as a falls prevention intervention, as recruitment was challenging. An important reason for this is that eligible participants felt that they were not at risk of falls (Hawley-Hague et al., 2016) and as such that a falls prevention intervention was not for them. This has been a common problem in that participants rate exercise intervention designed to reduce falls as important for other people (Haines, Day, Hill, Clemson, & Finch, 2014). In this study there were also participants who did not feel at risk of falls, which is consistent with the findings of another study with older participants (Yardley et al., 2006). For this reason, in the RCT phase of the TACIT Trial we have changed our strategy to take the emphasis away from falls to general health and well-being.

Class-Based Practice

The intervention was widely accepted by participants who particularly adhered to the class-based component. Consistent with previous exercise research, the qualities of the instructor (Hawley-Hague et al., 2016), the creation of a warm and failure-free environment (Barnes et al., 2015) and the socialising component (Wu et al., 2015) have been positively valued by participants and influenced their adherence to the study.

Researchers observed participants living with dementia that at times struggled to copy the instructor; however these participants only reported their enjoyment of Tai Chi. One reason for this might be that they felt able to do the Tai Chi well-enough and so report that they found the experience enjoyable. This could be partially supported by previous research suggesting that participants’ enjoyment of the intervention could be critical for their sustained participation in falls prevention interventions (McPhate et al., 2016). Previous studies have also found apathy in participants with lack of insight to their dementia symptoms (Aalten et al., 2006). This could explain a lack of awareness about their performance during the classes and their tendency not to communicate their difficulties. However, participants’ enjoyment of the socialising component could have impacted more positively on their acceptability of the intervention, as the satisfaction of the social need seemed to be crucial for people living with dementia (Maki, Amari, Yamaguchi, Nakaaki, & Yamaguchi, 2012).

Low sense of efficacy performing the movements perceived by the carer or the person living with dementia could have an impact on participants’ willingness to carry on taking part in the intervention. Both dyads who expressed this lack of competence ended up not willing (or not being able, due to health issues) to attend further sessions. In light of these results, tailored support from the instructor (Chong et al., 2014; Day, Trotter, Donaldson, Hill, & Finch, 2016; Pitkälä et al., 2013) in becoming aware of these perceptions could facilitate their adherence to the exercise intervention. Having successful experiences and verbal encouragement from the instructor, however, could have enhanced most participants’ efficacy beliefs (Bandura, 1977) which in turn have been shown to be a predictor of perseverance and adherence (Alharbi et al., 2016).

Home-Based Practice

The home-based component was generally well perceived by participants who included Tai Chi practice in their routines. However, their acceptability was challenged due to their difficulties remembering the Tai Chi movements at home, which was not improved by the use of the home-exercise booklet. Such difficulties could have potentially impacted on participants’ adherence to the home-based component. Our results expand on previous research findings suggesting the use of memory aids such as exercise booklets with images and explanations to support home-practice (Connell & Janevic, 2009; Logghe et al., 2011; Logsdon, McCurry, Pike, & Teri, 2009; Prick et al., 2014; Suttanon et al., 2013) and highlight the need for additional support so participants can perceive movements’ progression.

Difficulties to sustain attention have not been previously identified in exercise interventions for people living with dementia (Dal Bello-Haas et al., 2014; Prick et al., 2014). However, in this study, difficulties reported by two carers trying to get the attention of the person living with dementia for 20 minutes in one bout could be motivated by the home environment and the level of confidence of the carer supporting this practice. Previous research suggested that instructions provided by the instructor could have more impact on the person living with dementia than the ones offered by the carer (Prick et al., 2014), which could be influenced by the instructional methods and qualities of the instructor.

Dyadic Approach

In this study the use of a dyadic approach was accepted by both people living with dementia and their carers. This finding concurs with previous studies where a dyadic approach had been used to facilitate people living with dementia’s adherence to exercise interventions (Teri et al., 2003; Yao et al., 2012). Results from the current study suggest that this dyadic approach could not only facilitate their adherence to the intervention, but enable people living with dementia’s inclusion in these interventions. In the same way, feedback from carers reinforce the use of this dyadic approach in the context of dementia as it gives them the opportunity to discover enjoyable activities which could evolve to shared interests. These would be of particular relevance when these common activities could be helpful for carers (to experience their role more positively) and the person living with dementia (to feel competent and empowered) (DiLauro, Pereira, Carr, Chiu, & Wesson, 2015; Lamotte, Shah, Lazarov, & Corcos, 2016). Another strength of this dyadic approach highlighted by carers is that both, they themselves and the person living with dementia benefit from taking part in Tai Chi. This perceived benefit could potentially mean carers are willing to carry on practising after their involvement in the study, which would also be of benefit for the person living with dementia (Lamotte et al., 2016). In contrast to some reports in the literature (Wesson et al., 2013; Woods et al., 2016), carers did not perceive their involvement in this study as a burden.

Strengths and Limitations

Our results describe for the first time how people living with dementia and their carers respond to a Tai Chi exercise intervention. This study is the first of its kind to use qualitative methods to understand how appropriate a Tai Chi intervention is for people living with dementia and their carers. The use of a dyadic approach to gather the views of participants living with dementia and their carers, has enabled carers to support the researcher by rephrasing questions and inviting the person living with dementia to provide their views during the focus groups, as found in previous research (Nyman, Innes, & Heward, 2016; Prick et al., 2014) and in the TACIT Trial PPI advisory group.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the quality of the observations may have been impacted by the fact that the Tai Chi classes were not video-recorded (as the instructor did not consent for him or participants to be recorded during classes). The researcher may have missed some participants’ reactions whilst they were taking notes on different participants. Second, feedback from the two dyads who withdrew from the intervention was limited because one did not agree to take part in the final focus group, and the other dyad was not feeling well after their holiday period. An interview with the dyad that withdrew during the first class could have provided more insight into ways of facilitating their acceptability of the intervention. Third, time to collect participants’ views at the end of the class was also limited, however, capturing how people feel in that specific moment (after practising Tai Chi) could be particularly relevant in the context of dementia as recall could be facilitated by interviewing participants in their natural environment where they were taking part in the activity (Nygård, 2006). Lastly, during one of the focus group participants living with dementia could have felt uncomfortable by hearing their carers commenting they are not always able to provide accurate responses. Although people living with dementia did not seem to respond verbally or non-verbally to this, this could have silenced their voices.

Practical Implications

This study highlights three main aspects which should be considered in designing future exercise programs for people with dementia. First, the use of a dyadic approach in exercise interventions could be beneficial for both the person living with dementia and the carer at an individual level, but also facilitate their uptake of the intervention, as this would provide them with a potential common interest. Second, the combination of class and home-based practice could be advantageous to reinforce participants’ social support networks as well as strengthen dyadic relationships and facilitate the acceptability of the intervention by feeling an increased competence. Third, instructors’ awareness of dementia and adapted instructional methods in class and support materials at home facilitates participants´ acceptability of the classes. For this reason, it must be taken into account that booklets with images and descriptions might be insufficient for people living with dementia and their carers when facing unfamiliar movements such as those of Tai Chi. In this case, simple, clear and when possible, dynamic prompts (i.e., DVD) are advised.

Future Research

Future research investigating the acceptability of Tai Chi should consider the inclusion of participants from different ethnic backgrounds and with different relationships with the person living with dementia (other than spouse). In this study, informal carers were sought to be recruited independently from their relationship with the person living with dementia. However, only one dyad was not formed by a couple and in all cases the person living with dementia was living with the informal carer, which could have influenced their acceptability of the intervention and particularly their availability to take part in home-based practice. Similarly, the impact of the size of the group on dyads acceptability was only explored in two small groups, which could be less cost effective in community settings. The acceptability of larger groups formed by dyads rests unexplored in the context of exercise interventions for people living with dementia and their informal carers.

Conclusion

In summary, this novel study contributes to our understanding of the experiences, needs and preferences of people living with dementia taking part in exercise interventions with their carers. Intervention´s characteristics and participants’ reactions to the intervention might impact on their acceptability of exercise interventions. A series of improvements have been suggested by participants, instructor and the research team to facilitate the engagement of people living with dementia with different levels of performance (i.e., reducing the amount of content to be delivered) and support home practice (i.e., adjusting materials).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The TACIT Trial and PhD studentship awarded to Yolanda Barrado-Martín are funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Career Development Fellowship awarded to Dr Samuel Nyman, Bournemouth University. This paper presents independent research funded by the NIHR’s Career Development Fellowship Programme. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

The authors acknowledge senior instructor Robert Joyce, Elemental Tai Chi, who designed and delivered the Tai Chi course for this study. The authors acknowledge the advice received from Dr Shanti Shanker in regard to cognitive testing, Dr Jonathan Williams in regard to objective measurement of static and dynamic balance, and our public and patient involvement group on our approach to recruitment and data collection. The authors thank the Alzheimer’s Society for their assistance with publicising the study and the two main recruitment sites: Memory Assessment Research Centre, Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust (Principal Investigator: Brady McFarlane) and Memory Assessment Service, Dorset HealthCare University NHS Foundation Trust (Principal Investigator: Kathy Sheret). The authors acknowledge Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust for sponsorship of the pilot intervention phase (for contact details, please see ClinicalTrials.Gov registration). The sponsor’s responsibilities are as defined in the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care (second edition, 2005).

References

- Aalten P, van Valen E, de Vugt ME, Lousberg R, Jolles J, Verhey FRJ. Awareness and behavioral problems in dementia patients: A prospective study. International Psychogeriatrics. 2006;18(1):3–17. doi: 10.1017/S1041610205002772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraha I, Rimland JM, Trotta FM, Dell'Aquila G, Cruz-Jentoft A, Petrovic M, et al. Cherubini A. Systematic review of systematic reviews of non-pharmacological interventions to treat behavioural disturbances in older patients with dementia. The SENATOR-OnTop series. BMJ Open. 2017;7:1. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi M, Gallagher R, Neubeck L, Bauman A, Prebill G, Kirkness A, Randall S. Exercise barriers and the relationship to self-efficacy for exercise over 12 months of a lifestyle-change program for people with heart disease and/or diabetes. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2016;16(4):309–317. doi: 10.1177/1474515116666475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer's Disease International. Dementia statistics. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.alz.co.uk/research/statistics.

- Alzheimer’s Research UK. Dementia in the family: The impact on carers. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Dementia-in-the-Family-The-impact-on-carers.pdf.

- Alzheimer's Society. Factsheet 458LP: The progression of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=1772.

- Austin Z, Sutton J. Qualitative research: Getting started. The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2014;67(6):436–440. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v67i6.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Mehling W, Wu E, Beristianos M, Yaffe K, Skultety K, Chesney M. Preventing loss of independence through exercise (PLIÉ): A pilot clinical trial in older adults with dementia. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0113367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Burgener SC, APRN-BC, FAAN, Yang Y, Gilbert R, Marsh-Yant S. The effects of a multimodal intervention on outcomes of persons with early-stage dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias. 2008;23(4):382–394. doi: 10.1177/1533317508317527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton E, Cavalheri V, Adams R, Browne CO, Bovery-Spencer P, Fenton AM, et al. Hill KD. Effectiveness of exercise programs to reduce falls in older people with dementia living in the community: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2015;10:421–434. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S71691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron ID, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Murray GR, Hill KD, Cumming RG, Kerse N. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(12):1–184. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase J-AD. Interventions to increase physical activity among older adults: A meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2015;55(4):706–718. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S-T, Chow PK, Song Y-Q, Yu ECS, Chan ACM, Lee TMC, Lam JHM. Mental and physical activities delay cognitive decline in older persons with dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;22(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew J, Chong MS, Fong YL, Tay L. Outcomes of a multimodal cognitive and physical rehabilitation program for persons with mild dementia and their caregivers: A goal-oriented approach. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2015;10:1687–1694. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S93914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Moon JS, Song R. Effects of Sun-style Tai Chi exercise on physical fitness and fall prevention in fall-prone older adults. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;51(2):150–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong TWH, Doyle CJ, Cyarto EV, Cox KL, Ellis KA, Ames D, Lautenschlager NT. Physical activity program preferences and perspectives of older adults with and without cognitive impairment. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry: Official Journal of the Pacific Rim College of Psychiatrists. 2014;6(2):179–190. doi: 10.1111/appy.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Janevic MR. Effects of a telephone-based exercise intervention for dementia caregiving wives: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28(2):171–194. doi: 10.1177/0733464808326951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Bello-Haas VPM, O’Connell ME, Morgan DG, Crossley M. Lessons learned: Feasibility and acceptability of a telehealth-delivered exercise intervention for rural- dwelling individuals with dementia and their caregivers. Rural and Remote Health. 2014;14(3):2715. Retrieved from http://www.rrh.org.au/publishedarticles/article_print_2715.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day L, Trotter MJ, Donaldson A, Hill KD, Finch CF. Key factors influencing implementation of falls prevention exercise programs in the community. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2016;24(1):45–52. doi: 10.1123/japa.2014-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry. 2000;11(4):227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dewing J. Process consent and research with older persons living with dementia. Research Ethics Review. 2008;4(2):59–64. doi: 10.1177/174701610800400205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DiLauro M, Pereira A, Carr J, Chiu M, Wesson V. Spousal caregivers and persons with dementia: Increasing participation in shared leisure activities among hospital-based dementia support program participants. Dementia. 2015;16(1):9–28. doi: 10.1177/1471301215570680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble SJ, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Rudolph A, Hewison J. Describing qualitative research undertaken with randomised controlled trials in grant proposals: A documentary analysis. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farran CJ, Staffileno BA, Gilley DW, McCann JJ, Li Y, Castro CM, King AC. A lifestyle physical activity intervention for caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2008;23(2):132–142. doi: 10.1177/1533317507312556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetherston CM, Wei L. The benefits of tai chi as a self management strategy to improve health in people with chronic conditions. Journal of Nursing & Healthcare of Chronic Illnesses. 2011;3(3):155–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-9824.2011.01089.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiner T, Dauth H, Gersie M, Zijlstra W, Haussermann P. Structured physical exercise improves neuropsychiatric symptoms in acute dementia care: A hospital-based RCT. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy. 2017;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0289-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen KS, Sobol N, Beyer N, Hasselbalch S, Waldemar G. Moderate-to-high intensity aerobic exercise in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: A pilot study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;29(12):1242–1248. doi: 10.1002/gps.4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G, Timlin A, Curran S, Wattis J. The scope for qualitative methods in research and clinical trials in dementia. Age and Ageing. 2004;33(4):422–426. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines TP, Day L, Hill KD, Clemson L, Finch C. "Better for others than for me": A belief that should shape our efforts to promote participation in falls prevention strategies. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2014;59(1):136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton S, Ramsay E, Webster L, Payne NL, Taylor ME, Close JCT, et al. Brodaty H. A home-based, carer-enhanced exercise program improves balance and falls efficacy in community-dwelling older people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics. 2017;29(1):81. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley-Hague H, Horne M, Skelton DA, Todd C. Older adults' uptake and adherence to exercise classes: Instructors' perspectives. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2016;24(1):119–128. doi: 10.1123/japa.2014-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KD, Hunter SW, Batchelor FA, Cavalheri V, Burton E. Individualized home-based exercise programs for older people to reduce falls and improve physical performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2015;82(1):72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S, McGrory S, Leslie F, Dawson K, Ahmed S, Butler CR, et al. Hodges JR. The Mini-Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination: A new assessment tool for dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2015;39:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000366040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney JM, Rentz CA. Observed well-being among individuals with dementia: Memories in the Making, an art program, versus other structured activity. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2005;20(4):220–227. doi: 10.1177/153331750502000406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson MA. The clinical features of sarcoidosis: A comprehensive review. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2015;49(1):63–78. doi: 10.1007/s12016-014-8450-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte G, Shah RC, Lazarov O, Corcos DM. Exercise training for persons with Alzheimer's disease and caregivers: A review of dyadic exercise interventions. Journal of Motor Behavior. 2016:1–13. doi: 10.1080/00222895.2016.1241739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver K, Dyer S, Whitehead C, Clemson L, Crotty M. Interventions to delay functional decline in people with dementia: A systematic review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):1. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S, Glenton C, Oxman A. Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trials of complex healthcare interventions: Methodological study. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logghe IHJ, Verhagen AP, Rademaker ACHJ, Zeeuwe PEM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Van Rossum E, et al. Koes BW. Explaining the ineffectiveness of a Tai Chi fall prevention training for community-living older people: A process evaluation alongside a randomized clinical trial (RCT) Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2011;52(3):357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon RG, McCurry SM, Pike KC, Teri L. Making physical activity accessible to older adults with memory loss: A feasibility study. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(Suppl 1):S94–S99. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon RG, McCurry SM, Teri L. A home health care approach to exercise for persons with Alzheimer's disease. Care Management Journals. 2005;6(2):90–97. doi: 10.1891/cmaj.6.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki Y, Amari M, Yamaguchi T, Nakaaki S, Yamaguchi H. Anosognosia: Patients’ distress and self-awareness of deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2012;27(5):339–345. doi: 10.1177/1533317512452039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhate L, Simek EM, Haines TP, Hill KD, Finch CF, Day L. "Are your clients having fun?" The implications of respondents' preferences for the delivery of group exercise programs for falls prevention. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2016;24(1):129–138. doi: 10.1123/japa.2014-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon H, Adams KB. The effectiveness of dyadic interventions for people with dementia and their caregivers. Dementia. 2013;12(6):821–839. doi: 10.1177/1471301212447026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Falls in older people: Assessing risk and prevention. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg161/resources/falls-in-older-people-assessing-risk-and-prevention-35109686728645. [PubMed]

- NHS. Diverticular disease and diverticulitis. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Diverticular-disease-and-diverticulitis/Pages/Introduction.aspx.

- NHS. Fibromyalgia. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Fibromyalgia/Pages/Introduction.aspx.

- Nowalk MP, Prendergast JM, Bayles CM, D'Amico FJ, Colvin GC. A randomized trial of exercise programs among older individuals living in two long-term care facilities: The FallsFREE program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49(7):859–865. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygård L. How can we get access to the experiences of people with dementia? Suggestions and reflections. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006;13(2):101–112. doi: 10.1080/11038120600723190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman SR, Innes A, Heward M. Social care and support needs of community-dwelling people with dementia and concurrent visual impairment. Aging and Mental Health. 2016;21(9):961–967. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1186151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman SR, Skelton D. The case for Tai Chi in the repertoire of strategies to prevent falls among older people. Perspectives in Public Health. 2017;132(2):85–86. doi: 10.1177/1757913916685642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Drabble SJ, Rudolph A, Hewison J. What can qualitative research do for randomised controlled trials? A systematic mapping review. BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman H, Savikko N, Strandberg TE, Kautiainen H, Raivio MM, Laakkonen M-L, et al. Pitkälä KH. Effects of exercise on cognition: The Finnish Alzheimer disease exercise trial: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016;64(4):731–738. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman H, Savikko N, Strandberg TE, Pitkälä KH. Effect of physical exercise on cognitive performance in older adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A systematic review. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2014;38(5–6):347–365. doi: 10.1159/000365388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkälä KH, Pöysti MM, Laakkonen M-L, Tilvis RS, Savikko N, Kautiainen H, Strandberg TE. Effects of the Finnish Alzheimer disease exercise trial (FINALEX): A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173(10):894–901. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prick AE, de Lange J, van ‘t Leven N, Pot AM. Process evaluation of a multicomponent dyadic intervention study with exercise and support for people with dementia and their family caregivers. Trials. 2014;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo qualitative data analysis Software. (Version 11) 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rao AK, Chou A, Bursley B, Smulofsky J, Jezequel J. Systematic review of the effects of exercise on activities of daily living in people with Alzheimer's disease. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;68(1):50–56. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2014.009035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 3rd ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saravanakumar P, Higgins IJ, Van Der Riet PJ, Marquez J, Sibbritt D. The influence of Tai Chi and yoga on balance and falls in a residential care setting: A randomised controlled trial. Contemporary Nurse. 2014;48(1):76–87. doi: 10.5172/conu.2014.48.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw FE. Falls in older people with dementia. Geriatrics and Aging. 2003;6(7):37–40. Retrieved from https://www.healthplexus.net/files/content/2003/August/0607dementiafall.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Shelat AM. Neuralgia. 2016 Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001407.htm.

- Sherrington C, Whitney JC, Lord SR, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Close JC. Effective exercise for the prevention of falls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(12):2234–2243. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strookappe B, Swigris J, De Vries J, Elfferich M, Knevel T, Drent M. Benefits of physical training in sarcoidosis. Lung. 2015;193(5):701–708. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttanon P, Hill KD, Said CM, Byrne KN, Dodd KJ. Factors influencing commencement and adherence to a home-based balance exercise program for reducing risk of falls: Perceptions of people with Alzheimer's disease and their caregivers. International Psychogeriatrics. 2012;24(7):1172–1182. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211002729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttanon P, Hill KD, Said CM, Williams SB, Byrne KN, LoGiudice D, et al. Dodd KJ. Feasibility, safety and preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of a home-based exercise programme for older people with Alzheimer's disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2013;27(5):427–438. doi: 10.1177/0269215512460877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, et al. Larson EB. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease - A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(15):2015–2022. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai P-F, Chang JY, Beck C, Kuo Y-F, Keefe FJ, Rosengren K. A supplemental report to a randomized cluster trial of a 20-week Sun-style Tai Chi for osteoarthritic knee pain in elders with cognitive impairment. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2015;23(4):570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UK Data Archive. Create & Manage Data: Anonymisation. N. D. Retrieved from http://www.data-archive.ac.uk/create-manage/consent-ethics/anonymisation?index=2.

- Van't Leven N, Prick AE, Groenewoud JG, Roelofs PD, de Lange J, Pot AM. Dyadic interventions for community-dwelling people with dementia and their family caregivers: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2013;25(10):1581–1603. doi: 10.1017/s1041610213000860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesson J, Clemson L, Brodaty H, Lord S, Taylor M, Gitlin L, Close J. A feasibility study and pilot randomised trial of a tailored prevention program to reduce falls in older people with mild dementia. BMC Geriatrics. 2013;13:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Falls_prevention7March.pdf?ua=1.

- WHO. Dementia: A public health priority. 2012 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75263/1/9789241564458_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- WHO. The epidemiology and impact of dementia: Current state and future trends. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/dementia_thematicbrief_epidemiology.pdf.

- Woods RT, Orrell M, Bruce E, Edwards RT, Hoare Z, Hounsome B, et al. Russell I. REMCARE: Pragmatic multi-centre randomised trial of reminiscence groups for people with dementia and their family carers: Effectiveness and economic analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0152843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu E, Barnes DE, Ackerman SL, Lee J, Chesney M, Mehling WE. Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIE): qualitative analysis of a clinical trial in older adults with dementia. Aging and Mental Health. 2015;19(4):353–362. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.935290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L, Giordani BJ, Algase DL, You M, Alexander NB. Fall risk-relevant functional mobility outcomes in dementia following dyadic Tai Chi exercise. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2012;35(3):281–296. doi: 10.1177/0193945912443319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]