Abstract

Background

We examined relationships between schistosome infection, HIV transmission or acquisition, and all-cause death.

Methods

We retrospectively tested baseline sera from a heterosexual HIV-discordant couple cohort in Lusaka, Zambia with follow-up from 1994–2012 in a nested case-control design. Schistosome-specific antibody levels were measured by ELISA. Associations between baseline antibody response to schistosome antigens and incident HIV transmission, acquisition, and all-cause death stratified by gender and HIV status were assessed. In a subset of HIV- women and HIV+ men, we performed immunoblots to evaluate associations between Schistosoma haematobium or Schistosoma mansoni infection history and HIV incidence.

Results

Of 2,145 individuals, 59% had positive baseline schistosome-specific antibody responses. In HIV+ women and men, baseline schistosome-specific antibodies were associated with HIV transmission to partners (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.8, p<0.005 and aHR = 1.4, p<0.05, respectively) and death in HIV+ women (aHR = 2.2, p<0.001). In 250 HIV- women, presence of S. haematobium-specific antibodies was associated with increased risk of HIV acquisition (aHR = 1.4, p<0.05).

Conclusion

Schistosome infections were associated with increased transmission of HIV from both sexes, acquisition of HIV in women, and increased progression to death in HIV+ women. Establishing effective prevention and treatment strategies for schistosomiasis, including in urban adults, may reduce HIV incidence and death in HIV+ persons living in endemic areas.

Author summary

This study explored the association between schistosome infections (a disease caused by parasitic flatworms, also known as ‘snail fever’, which is very common throughout sub-Saharan Africa) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). We found in Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, that schistosome infections were associated with transmission of HIV from adult men and women, and schistosome infections were also associated with increased HIV acquisition in adult women. We additionally found that schistosome infections were associated with death in HIV+ adult women. Since treatment of schistosome infections with praziquantel is inexpensive, effective, and safe, schistosomiasis prevention and treatment strategies may be a cost-effective way to reduce not only the symptoms associated with the infection, but also new cases of HIV and death among HIV+ persons. Though often viewed as an infection of predominantly rural areas and children, this study highlights that schistosomiasis prevention and treatment efforts are also needed in urban areas and among adults.

Introduction

Of the more than 200 million persons who have schistosomiasis worldwide, more than 90% live in Africa, and the disease causes tens to hundreds of thousands of deaths annually [1]. Of the parasitic diseases, the health impact of schistosomiasis is second only to malaria [2]. Common species in sub-Saharan Africa are Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni, which cause urogenital and intestinal schistosomiasis, respectively [2]. Infection is generally established during childhood and is more common among those living in rural areas with frequent freshwater contact [1]. However, urbanization trends have increasingly brought schistosomiasis to municipal areas including Lusaka, the capital of Zambia [3, 4].

Like many of the neglected tropical diseases, preventive chemotherapy using mass drug administration is the primary strategy for controlling schistosomiasis. Though praziquantel treatment is inexpensive, effective, and safe [5], only 14% of adults and 54% of school-aged children estimated to need preventive chemotherapy in 2016 received treatment [6]. Schistosome eggs not passed in urine or stool become lodged in tissues and induce granulomas that cause the pathology associated with schistosomiasis which persists after the death of the egg. For example, in female genital schistosomiasis (FGS), deposition of eggs can occur in the cervix, vagina, and/or vulva putting women at risk for genital epithelial bleeding, sandy patches on the cervix and throughout the genital tract [7, 8], and vaginal inflammation at the histopathological level [9, 10]. These lesions and inflammation can persist long after eggs are deposited, irrespective of treatment [11, 12].

Like other infections that generate a local immune response and/or cause genital lesions (e.g., ulcerative and non-ulcerative sexually transmitted infections (STI) caused by syphilis, herpes simplex virus (HSV), trichomonas, gonorrhea, and chlamydia), schistosomiasis may increase the risk of HIV infection [13, 14]. Cross-sectional studies show associations between urogenital schistosomiasis and HIV prevalence [15]. Though relatively few longitudinal studies have been published, the literature supports the hypothesis that urogenital schistosomiasis is a risk factor for HIV acquisition in HIV- persons and a risk factor for HIV transmission and disease progression in those co-infected with HIV [16–19].

Because it may increase risk of HIV transmission or acquisition, treating schistosomiasis could be a highly cost-effective HIV prevention strategy, and the World Health Organization has called for more studies examining schistosomiasis in HIV endemic countries [15, 20–22]. In Zambia, a country with high prevalence of both HIV (13%, [23]) and schistosomiasis (5–40% [3, 24, 25]), we retrospectively analyzed data from urban adults enrolled in a longitudinal HIV discordant couple cohort to test the hypothesis that there is a relationship between a person having schistosome-specific antibodies (reflecting either active or previous infection, with potential for residual sequelae) and transmitting HIV, acquiring HIV, and all-cause death. We also describe the effect of infecting schistosome species on HIV acquisition among a sub-set of female HIV- and male HIV+ cohort participants.

Methods

Ethics statement

The Emory University Office for Human Research Protections-registered Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Zambian Ethics Committee approved this study. The University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (IORG0000774) is registered with the US Office of Human Research Protection (IRB00001131). Written informed consent was obtained from participants, all of whom were adults. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also reviewed the protocol; CDC investigators were not considered to be engaged with study participants as they had no direct contact with them and no access to identifying information.

The cohort

Heterosexual HIV discordant couples (M+F- and M-F+) were enrolled in an open cohort with longitudinal follow-up every three months in Lusaka, Zambia between 1994 and 2012. Participants were identified through couples’ voluntary HIV counseling and testing (CVCT). Study recruitment [26], enrollment, retention and attrition [27], HIV testing and counseling procedures [28, 29], and cohort demographics [30] have been previously published. Briefly, CVCT included group educational sessions, rapid HIV antibody testing, and joint post-test couples’ counseling. HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couples who voluntarily enrolled in the open cohort were provided with free outpatient care including STI testing/treatment and family planning. Couples were censored upon antiretroviral treatment initiation, death of either partner, or relationship dissolution.

Data on demographics (including age, years cohabiting, monthly income, and literacy in Nyanja, the most commonly spoken language in Lusaka Province), family planning, and clinical characteristics (including pregnancy, baseline HIV stage and viral load of HIV+ partners, male partner circumcision status, and STI history) were collected. Past year STI history included self-reported gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomonas, syphilis, and HSV-2 diagnoses. Viral load was not collected before 1999. Genital abnormalities assessed included discharge or inflammation on visual genital exam (including speculum exam for women). Trichomonas, bacterial vaginosis (BV), and candida infections in women were detected by microscopy of vaginal wet mount swabs (and additional whiff test for BV); genital ulceration (including cervical/vaginal erosion or friability); and syphilis diagnosed via rapid plasma regain (RPR) (BD Macro-Vue, Becton-Dickinson Europe), with Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay confirmation when available [31]. HSV-2 infections were diagnosed by serology testing with the highly sensitive test Focus Diagnostics HerpeSelect 2 ELISA IgG, [32], with repeat testing for indeterminate results.

Outcomes

HIV incidence was measured via testing of HIV- partners every 1–3 months using rapid antibody tests [29]. When available, plasma from the last antibody negative sample was tested by p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Based on available data, date of infection was defined as the minimum of: the midpoint between the last negative and first positive antibody test; two weeks prior to a first antigen positive test; or two weeks prior to a first viral load positive/antibody negative test [33]. Date of death was reported by study partners or other family members; >90% of deaths among HIV+ persons were HIV-related [34] and thus death is a proxy for HIV disease progression. Outcomes of interest were relationships between schistosome-specific antibody positivity and time-to incident: HIV acquisition (incident HIV infection in a previously HIV- partner), HIV transmission (onward HIV transmission from an HIV+ index partner), and all-cause death. Our analysis is limited to HIV infections genetically linked to the HIV+ study partner determined via comparison of PCR-amplified conserved nucleotide sequences (gag, gp120, gp41, long terminal repeat regions) between partners [35].

Measurement of schistosomiasis antibodies and species

Blood plasma and serum samples were collected at enrollment from all couples and stored in a repository at Emory University. In 2010, we retrospectively tested plasma samples from individuals enrolled between 1994 and 2009 for antibodies to schistosome soluble worm antigen preparation (SWAP) using a previously described ELISA [36]. All seroconvertors with available samples were included along with a random sample of non seroconvertors in this nested case-control deisgn. ELISA data from each complete discordant pair were not available for some couples. To ensure consistency between plates, a standard 1:3 serial dilution curve was prepared and included on each plate. A 4-parameter curve fitting model was used to assign units based on the standard curve to each unknown sera. The positive cutoff value (25 units) was set at three standard deviations above the average anti-SWAP IgG in serum from egg negative controls from the US and Europe [36]. A positive schistosomiasis result was defined as having a positive SWAP antibody response. A coded list of individuals positive for schistosome-specific antibody was sent to the Director of the Lusaka research site (author WK), and those individuals were offered free praziquantel treatment. Immunoblot testing using species-specific antigens was used to distinguish between S. haematobium and S. mansoni antibodies in women and men in a random sample of individuals from the nested case-control study where males were HIV positive and females were negative (M+F-) at baseline [37].

Statistical data analyses

Descriptive statistics (counts and percentages) described the distribution of schistosomiasis ELISA antibody responses stratified by gender, HIV status, and baseline characteristics, with differences evaluated using Chi-square (or Fisher’s exact) tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-tests for continuous variables. Unadjusted associations between baseline SWAP ELISA results and outcomes of interest were estimated from Cox survival models; crude hazard ratios (cHRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and two-tailed p-values are reported. Adjusted Cox survival models were created and adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) were calculated adjusting for factors associated (p<0.05) with both the exposure and outcome of interest (the ‘confounding triangle’ method). We also applied a second strategy for adjustment by exploring all subsets of potential confounders to look for meaningful (+/-10%) differences in adjusted hazard ratios. In the subset of individuals in M+F- couples with species-specific immunoblot results, we similarly ran unadjusted and adjusted analyses assessing the association between either S. haematobium or S. mansoni and HIV incidence and death. In this subset analysis, we considered the potential for confounding by the other species. All analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

The average follow-up time for n = 1046 male participants was 801.5 days (standard deviation, SD = 778.1, 2,295.2 total man-years of observation). The average follow-up time for n = 1099 female participants was 816.3 days (SD = 799.4, 2456.3 total woman-years of observation).

In this analysis, 19% of men and 12% of women died during follow-up, 8% of HIV+ men and 10% of HIV+ women initiated ART during follow-up, and 4% of couples separated during follow-up (censoring criteria).

Distribution of SWAP ELISA results

Of 2,145 individuals tested by SWAP ELISA, 59% were positive for anti-schistosome antibodies at baseline (25% had ELISA levels >70 units, 34% had 25–70 units), and 41% were negative (<25 units). Schistosome-specific antibody levels were higher in men than women (p<0.0001). This difference was driven by a much higher number of males than females with ELISA levels >70 units (31% of men vs. 19% of women) while the frequencies for 25-<50 and 50–70 units were similar for men and women. There were no differences in the distribution of ELISA results when stratifying by sex and HIV status simultaneously (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline schistosome-specific antibody status stratified by sex and HIV status.

| All Women | All Men | HIV+ Women | HIV- Women | HIV+ Men | HIV- Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA units | N (%) | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | N (%) | p-value |

| >70 | 210 (19) | 326 (31) | < .0001 | 111 (19) | 99 (20) | 0.319 | 179 (30) | 147 (33) | 0.320 |

| 50–70 | 95 (9) | 95 (9) | 52 (9) | 43 (9) | 53 (9) | 42 (9) | |||

| 25 –<50 | 266 (24) | 269 (26) | 133 (22) | 133 (26) | 149 (25) | 120 (27) | |||

| < 25 | 528 (48) | 356 (34) | 300 (50) | 228 (45) | 218 (36) | 138 (31) | |||

| Total (row %) | 1099 (51) | 1046 (49) | 596 (28) | 503 (23) | 599 (28) | 447 (21) |

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

p-values are for comparisons across all four ELISA categories

Associations between women’s schistosome-specific antibody status and baseline characteristics (Table 2)

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and associations between women’s baseline characteristics and schistosome-specific antibody status.

| HIV+ (N = 596) | HIV- (N = 503) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schistosome-specific antibody status | Schistosome-specific antibody status | |||||

| Positive | Negative | p-value | Positive | Negative | p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (mean, SD) | 28.2 (7.3) | 28.3 (6.9) | 0.788 | 27.6 (7.0) | 26.6 (6.9) | 0.097 |

| Years cohabiting (mean, SD) | 6.2 (7.2) | 5.6 (5.8) | 0.222 | 7.6 (6.5) | 7.4 (6.7) | 0.740 |

| Monthly household income (mean USD, SD) | 60.2 (76.5) | 71.3 (107.1) | 0.147 | 59.8 (78.6) | 67.1 (70.3) | 0.282 |

| Reads Nyanja | 0.628 | 0.850 | ||||

| Yes, easily (N, %) | 68 (23) | 74 (25) | 50 (19) | 40 (18) | ||

| With difficulty/not at all (N, %) | 223 (77) | 221 (75) | 220 (81) | 184 (82) | ||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Pregnant at baseline | < .0001 | 0.033 | ||||

| Yes (N, %) | 28 (9) | 64 (21) | 33 (12) | 43 (19) | ||

| No (N, %) | 268 (91) | 236 (79) | 242 (88) | 185 (81) | ||

| HIV stage | 0.001 | |||||

| Stage I (N, %) | 84 (28) | 120 (40) | ||||

| Stage II (N, %) | 84 (28) | 93 (31) | ||||

| Stage III-IV (N, %) | 128 (43) | 87 (29) | ||||

| Viral load (mean log10 copies/ml, SD)* | 4.6 (0.9) | 4.4 (0.9) | 0.094 | |||

| Past year history of any STI | 0.559 | 0.844 | ||||

| Yes (N, %) | 136 (46) | 145 (48) | 96 (35) | 77 (34) | ||

| No (N, %) | 160 (54) | 155 (52) | 179 (65) | 149 (66) | ||

| Genital conditions (non-ulcerative) | <0.001 | 0.822 | ||||

| STI-associated (N, %) | 56 (19) | 33 (11) | 35 (13) | 25 (11) | ||

| Non-STI-associated (N, %) | 73 (25) | 51 (17) | 63 (23) | 52 (23) | ||

| None (N, %) | 167 (56) | 216 (72) | 177 (64) | 151 (66) | ||

| Genital ulcer | 0.003 | 0.497 | ||||

| Yes (N, %) | 67 (23) | 40 (13) | 33 (12) | 23 (10) | ||

| No (N, %) | 229 (77) | 260 (87) | 242 (88) | 205 (90) | ||

| Baseline schistosome-specific antibody status of male partner | 0.002 | 0.004 | ||||

| Positive (N, %) | 188 (76) | 97 (61) | 197 (76) | 132 (63) | ||

| Negative (N, %) | 60 (24) | 62 (39) | 63 (24) | 76 (37) | ||

SD: standard deviation; STI: sexually transmitted infection; USD: United States Dollar

Genital conditions (non-ulcerative) of STI origin includes: clinical or laboratory diagnosis or treatment of gonorrhea or chlamydia (including presumptive treatment given detection of endocervical discharge) or trichomonas. Genital conditions (non-ulcerative) of non-STI origin includes: reported discharge, dysuria, dyspareunia; observed discharge or inflammation of external or internal genitalia; and/or laboratory diagnosis of candida or bacterial vaginosis (with no indication of an inflammatory STI). Genital ulcer includes: observed or reported ulcers and/or baseline positive rapid plasma regain status greater than a titer of 1:2. Genital conditions (non-ulcerative) categories are based on Wall et al [38].

*Not collected before 1999 (samples available for N = 410 HIV+ women).

Women with positive schistosome-specific ELISA results were less likely to be pregnant at baseline (p<0.0001). Positive schistosome-specific ELISA results were also associated with signs and symptoms of genital conditions (non-ulcerative) of STI or non-STI etiologies (p<0.001) and genital ulcers (p = 0.003) in HIV+ women. HIV+ women who were positive for schistosome-specific antibodies were more likely to be at an advanced HIV disease stage III-IV (p = 0.001). In addition, women who were positive for schistosome-specific antibodies were more likely to have a male partner that was also schistosome-specific antibody positive (p<0.01). However, a woman’s age, duration of cohabitation, household income, literacy, and viral load were not statistically significantly associated with schistosome-specific ELISA status. Similarly, number of prior pregnancies, baseline HSV-2 antibody status, or baseline RPR results were not associated with schistosome-specific ELISA status (data not tabled). In the subset of women with information on fertility intentions, tribal/linguistic group, or where they lived prior to age 16 (which was only collected after 2002), there was also no association with schistosome-specific ELISA status (data not tabled). Most data were missing for fertility intentions (72%), tribal/linguistic group (69%), or where they lived prior to age 16 (81%).

Associations between men’s schistosome-specific antibody status and baseline characteristics (Table 3)

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and associations between men’s baseline characteristics and schistosome-specific antibody status.

| HIV+ (N = 599) | HIV- (N = 447) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schistosome-specific antibody status | Schistosome-specific antibody status | |||||

| Positive | Negative | p-value | Positive | Negative | p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (mean, SD) | 34.3 (7.6) | 34.2 (7.9) | 0.955 | 35.1 (9.2) | 33.5 (8.7) | 0.073 |

| Years cohabiting (mean, SD) | 7.6 (6.6) | 7.2 (6.1) | 0.458 | 5.7 (7.0) | 5.3 (4.9) | 0.637 |

| Monthly household income (mean USD, SD) | 61.0 (79.2) | 72.1 (82.8) | 0.109 | 60.7 (78.5) | 69.5 (117.6) | 0.352 |

| Reads Nyanja | 0.029 | 0.432 | ||||

| Yes, easily (N, %) | 181 (49) | 81 (40) | 124 (42) | 58 (46) | ||

| With difficulty/not at all (N, %) | 187 (51) | 123 (60) | 172 (58) | 68 (54) | ||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| HIV stage | 0.912 | |||||

| Stage I (N, %) | 82 (22) | 50 (23) | ||||

| Stage II (N, %) | 145 (38) | 77 (35) | ||||

| Stage III-IV (N, %) | 154 (40) | 91 (42) | ||||

| Viral load (mean log10 copies/ml, SD)* | 5.0 (0.8) | 4.8 (0.9) | 0.025 | |||

| Circumcised | 0.004 | 0.373 | ||||

| Yes (N, %) | 42 (11) | 9 (4) | 48 (16) | 17 (12) | ||

| No (N, %) | 339 (89) | 209 (96) | 261 (84) | 121 (88) | ||

| Past year history of any STI | 0.311 | 0.442 | ||||

| Yes (N, %) | 178 (47) | 111 (51) | 107 (35) | 53 (38) | ||

| No (N, %) | 202 (53) | 106 (49) | 202 (65) | 85 (62) | ||

| Genital conditions (non-ulcerative) | 0.358 | 0.062 | ||||

| STI (N, %) | 17 (4) | 5 (2) | 12 (4) | 2 (1) | ||

| Non-STI (N, %) | 7 (2) | 3 (1) | 23 (7) | 4 (3) | ||

| No (N, %) | 357 (94) | 210 (96) | 274 (89) | 132 (96) | ||

| Genital ulcer | 0.532 | 0.067 | ||||

| Yes (N, %) | 67 (18) | 34 (16) | 35 (11) | 8 (6) | ||

| No (N, %) | 314 (82) | 184 (84) | 274 (89) | 130 (94) | ||

| Baseline schistosome-specific antibody status of female partner | 0.004 | 0.002 | ||||

| Positive (N, %) | 197 (60) | 63 (45) | 188 (66) | 60 (49) | ||

| Negative (N, %) | 132 (40) | 76 (55) | 97 (34) | 62 (51) | ||

SD: standard deviation; STI: sexually transmitted infection; USD: United States Dollar

Genital conditions (non-ulcerative) of STI origin includes: clinical or laboratory diagnosis or treatment of gonorrhea or chlamydia (including presumptive treatment given detection of urethral discharge). Genital conditions (non-ulcerative) of non-STI origin includes: reported discharge, dysuria, dyspareunia; and/or observed discharge or inflammation of external genitalia (with no indication of an inflammatory STI). Genital ulcer includes: observed or reported ulcers and/or baseline positive rapid plasma regain status greater than a titer of 1:2. Genital conditions (non-ulcerative) categories are based on Wall et al [38].

*Not collected before 1999 (samples available for N = 417 HIV+ men).

Unlike in women, presence of schistosome-specific antibodies in HIV+ men were not related to HIV disease stage but viral loads were higher in men with positive schistosome-specific antibody status (p = 0.025). Interestingly, positive schistosome-specific antibody status was associated with an increased likelihood of being circumcised among HIV+ men (p = 0.004) and increased literacy (p = 0.029). Among HIV- men, genital conditions (non-ulcerative) (p = 0.062) and genital ulcer (p = 0.067) were not statistically significantly associated with a positive schistosome-specific antibody result. In addition, men who were positive for schistosome-specific antibodies were more likely to have a female partner that was also schistosome-specific antibody positive (p<0.01). Men’s age, duration of cohabitation, household income, literacy, and reported history of STI in the last year were not associated with schistosome-specific antibody responses. Nor was baseline HSV-2 antibody status, baseline RPR results, or (in a subset of men with the following information which was only collected after 2002) fertility intentions, tribal/linguistic group, or where they lived prior to age 16 associated with schistosome-specific antibody status (data not tabled). Most data were missing for fertility intentions (75%), tribal/linguistic group (72%), or where they lived prior to age 16 (83%).

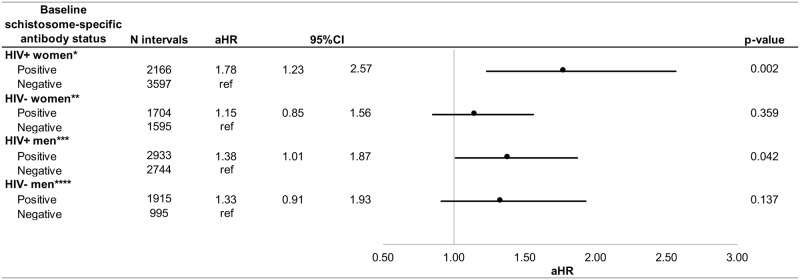

Associations between women’s baseline schistosome-specific antibody status and HIV transmission and acquisition (Fig 1, S1 Table)

Fig 1. Adjusted associations between women's and men's baseline schistosome-specific antibody status and HIV transmission and acquisition.

CI: confidence interval; aHR: adjusted hazard ratio *Controlling for factors associated with both the exposure and outcome of interest: Genital conditions (non-ulcerative) of woman, genital ulcer of woman **Controlling for factors associated with both the exposure and outcome of interest: Male partner's baseline schistosome-specific antibody status ***Controlling for factors associated with both the exposure and outcome of interest: Viral load of man ****Controlling for factors associated with both the exposure and outcome of interest: Female partner's baseline schistosome-specific antibody status.

We observed N = 70/296 and N = 70/300 linked HIV transmission outcomes for baseline schistosome-specific antibody positive and negative HIV+ women, respectively. We observed N = 92/275 and N = 97/228 linked HIV acquisition outcomes for baseline schistosome-specific antibody positive and negative HIV- women, respectively. In unadjusted analyses, HIV+ women positive for schistosome-specific antibodies at baseline had a shorter time-to-HIV transmission to HIV- male partners (cHR = 1.8, p = 0.002). When multivariate analyses were performed controlling for genital conditions (non-ulcerative) and genital ulceration of the woman, positive baseline schistosome-specific antibody in HIV+ women remained associated with shorter time-to-HIV transmission to HIV- male partners (aHR = 1.8, p = 0.002). When applying a different strategy for adjustment (exploring at all subsets of potential confounders to look for meaningful (+/-10%) differences in adjusted hazard ratios), we arrived at the same set of confounders as when using the present (‘confounding triangle’) method. Because of the nested case-control design, proportions of outcomes should not be calculated/interpreted as risk estimates.

Associations between men’s baseline schistosome-specific antibody status and HIV transmission and acquisition (Fig 1, S2 Table)

We observed N = 112/381 and N = 78/218 HIV transmission outcomes for baseline schistosome-specific antibody positive and negative HIV+ men, respectively. We observed N = 93/309 and N = 53/138 HIV acquisition outcomes for baseline schistosome-specific antibody positive and negative HIV- men, respectively. In unadjusted analyses, HIV+ men positive for schistosome-specific antibodies at baseline had a shorter time-to-HIV transmission to HIV- female partners (cHR = 1.4, p = 0.016). When multivariate analyses were performed controlling for men’s viral load, positive baseline schistosome-specific antibody in HIV+ men remained associated with shorter time-to-HIV transmission to HIV- female partners (aHR = 1.4, p = 0.042). When applying a different strategy for adjustment (exploring at all subsets of potential confounders to look for meaningful (+/-10%) differences in adjusted hazard ratios), we arrived at the same set of confounders as when using the present (‘confounding triangle’) method. Because of the nested case-control design, proportions of outcomes should not be calculated/interpreted as risk estimates.

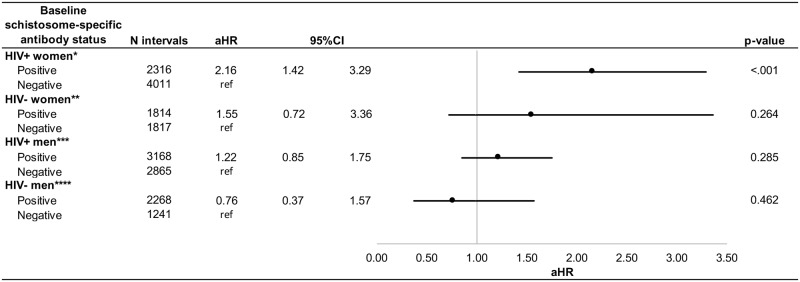

Associations between women’s baseline schistosome-specific antibody status and death (Fig 2, S3 Table)

Fig 2. Adjusted associations between women's and men's baseline schistosome-specific antibody status and death.

CI: confidence interval; aHR: adjusted hazard ratio *Controlling for factors associated with both the exposure and outcome of interest: HIV stage of woman **Unadjusted model ***Controlling for factors associated with both the exposure and outcome of interest: Viral load of man ****Controlling for factors associated with both the exposure and outcome of interest: Female partner's baseline schistosome-specific antibody status.

We observed N = 65/296 and N = 44/300 death outcomes for baseline schistosome-specific antibody positive and negative HIV+ women, respectively. We observed N = 17/275 and N = 11/228 death outcomes for baseline schistosome-specific antibody positive and negative HIV- women, respectively. In unadjusted analyses, HIV+ women positive for schistosome-specific antibodies at baseline had a shorter time-to-women’s death (cHR = 2.3, p<0.0001). When multivariate analyses were performed controlling for HIV stage of the woman, positive baseline schistosome-specific antibody in HIV+ women remained associated with shorter time-to-women’s death (aHR = 2.2, p<0.001). When applying a different strategy for adjustment (exploring at all subsets of potential confounders to look for meaningful (+/-10%) differences in adjusted hazard ratios), we arrived at the same set of confounders as when using the present (‘confounding triangle’) method. When adjusting for viral load of the HIV+ woman (as was done in the model for men, below), the point estimate is slightly tempered but still significant (aHR = 1.97; 95%CI:1.19–3.25, p-value = 0.008) (data not tabeled).

Associations between men’s baseline schistosome-specific antibody status and death (Fig 2, S4 Table)

We observed N = 110/381 and N = 56/218 death outcomes for baseline schistosome-specific antibody positive and negative HIV+ men, respectively. We observed N = 21/309 and N = 13/138 death outcomes for baseline schistosome-specific antibody positive and negative HIV- men, respectively. In unadjusted analyses, HIV+ men positive for schistosome-specific antibodies at baseline were associated with decreased time-to-men’s death (cHR = 1.6, p = 0.008). Baseline schistosome-specific antibody levels were not significantly associated with time-to-HIV+ men’s death once adjusting for men’s viral load. However, viral load was not collected before 1999, thus only 126 of 166 death events were modeled when controlling for viral load. When applying a different strategy for adjustment (exploring at all subsets of potential confounders to look for meaningful (+/-10%) differences in adjusted hazard ratios), we arrived at the same set of confounders as when using the present (‘confounding triangle’) method.

Associations between schistosomiasis species-specific immunoblot results and HIV acquisition and transmission (Table 4)

Table 4. Unadjusted and adjusted associations between schistosomiasis species-specific immunoblot results and HIV acquisition and transmission.

| Women's results | Woman HIV- | |||||||||

| Linked HIV acquisitions | Non-HIV acquiring | cHR | 95%CI | p-value | aHR* | 95%CI | p-value | |||

| S. haematobium | ||||||||||

| Positive (N intervals, %) | 63 (30) | 391 (26) | 1.44 | 1.05 | 1.96 | 0.022 | 1.40 | 1.03 | 1.92 | 0.034 |

| Negative (N intervals, %) | 144 (70) | 1108 (74) | ref | ref | ||||||

| S. mansoni | ||||||||||

| Positive (N intervals, %) | 40 (19) | 265 (18) | 1.30 | 0.91 | 1.87 | 0.147 | 1.33 | 0.93 | 1.91 | 0.121 |

| Negative (N intervals, %) | 167 (81) | 1234 (82) | ref | ref | ||||||

| Men's results | Man HIV + | |||||||||

| Linked HIV trans-missions | Non-HIV transmitting | cHR | 95%CI | p-value | aHR** | 95%CI | p-value | |||

| S. haematobium | ||||||||||

| Positive (N intervals, %) | 64 (33) | 492 (35) | 0.94 | 0.69 | 1.27 | 0.676 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 1.20 | 0.422 |

| Negative (N intervals, %) | 132 (67) | 909 (65) | ref | ref | ||||||

| S. mansoni | ||||||||||

| Positive (N intervals, %) | 44 (22) | 197 (14) | 1.37 | 0.97 | 1.93 | 0.071 | 1.33 | 0.94 | 1.88 | 0.111 |

| Negative (N intervals, %) | 152 (78) | 1204 (86) | ref | ref | ||||||

cHR: crude hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; aHR: adjusted hazard ratio

p-values are two-tailed

*Controlling for genital conditions (non-ulcerative) of woman, genital ulcer of woman

**Controlling for viral load of the man

Among 250 HIV- women and 239 HIV+ men, we observed N = 63/76 and N = 144/174 HIV acquisition outcomes for S. haematobium positive and negative HIV- women, respectively. We observed N = 40/46 and N = 167/204 HIV acquisition outcomes for S. mansoni positive and negative HIV- women, respectively. We observed N = 64/80 and N = 132/159 HIV transmission outcomes for S. haematobium positive and negative HIV+ men, respectively. We observed N = 44/54 and N = 152/185 HIV transmission outcomes for S. mansoni positive and negative HIV+ men, respectively. In M+F- HIV discordant couples, species-specific schistosome antibody response were evaluated by species-specific immunoblot results. S. haematobium-specific antibodies (aHR = 1.4, p = 0.034) significantly increased the risk HIV acquisition in women, while S. mansoni-specific antibodies also increased risk of HIV acquisition, though not significantly (aHR = 1.3, p = 0.12). The schistosome species infecting men did not significantly influence the likelihood of viral transmission to their HIV- partners. Notably, we had very limited power to detect the difference between S. mansoni status and HIV acquisition in HIV- women (3%) or S. mansoni status and HIV transmission from HIV+ men (19%). When applying a different strategy for adjustment (exploring at all subsets of potential confounders to look for meaningful (+/-10%) differences in adjusted hazard ratios), we arrived at the same set of confounders as when using the present (‘confounding triangle’) method. Because of the nested case-control design, proportions of outcomes should not be calculated/interpreted as risk estimates.

Discussion

Our findings indicate a high prevalence of antibodies to schistosomes that was associated with onward HIV transmission from HIV+ men and women and earlier death in HIV+ women. S. haematobium specific immunoblot reactivity was associated (p = 0.034) with increased HIV acquisition risk in HIV- women.

In this study, 59% of participants were positive for schistosome-specific antibodies, indicating an unexpectedly high prevalence of current or past infection in our urban population. Past infection can lead to persistent residual sequelae, which may increase HIV risk irrespective of treatment [11, 12]. Men had higher ELISA values at baseline than women, possibly explained by the finding that more men than women had lived in a rural area prior to age 16. Rural areas in Zambia have a higher prevalence of schistosomiasis, and most infections are acquired during youth [39]. The high observed prevalence of schistosome-specific antibodies in this urban population necessitates a shift in thinking of schistosomiasis as only a disease of children and rural areas. More research is needed to examine urbanization and migration in schistosomiasis transmission, especially in endemic countries. For example, individuals in Lusaka without access to effective water delivery systems may rely on both piped and environmental water sources, which might increase their risk of acquiring schistosome infection [25].

Past or baseline schistosome infection in HIV+ partners was significantly associated with onward HIV transmission to HIV- partners. A possible explanation is increased viral load in the HIV+ partners. In co-infected HIV+ men, schistosome egg excretion in semen may be accompanied by increases in lymphocytes, eosinophils [40], and other cells associated with HIV replication. Furthermore, HIV binding receptors (CCR5 and CXC4) are denser on CD4 T-cell surfaces in men with intestinal schistosomiasis compared to uninfected individuals and those treated with praziquantel [41]. In co-infected HIV+ women, genital schistosomiasis may lead to inflammatory genital lesions that increase transmissibility of HIV [13].

We also observed that S. haematobium (but not S. mansoni) infection as determined by immunoblot was associated increased risk of HIV acquisition by HIV- women in discordant relationships. This finding is consistent with the association of urogenital schistosomiasis and FGS and is similar, though of lesser magnitude, to results from studies in rural Zimbabwe [13] and Tanzania [14, 42] that showed schistosomiasis was associated with a 2–3 fold increased HIV risk in women. However, prior studies did not rely on antibody status indicating past or current infection but rather active infection, limiting direct comparisons with our study. FGS may increase susceptibility to HIV due to cervical lesions reducing the integrity of the genital epithelial barrier [7, 10, 13, 43] or recruitment of CD4+ lymphocytes, macrophages, and Langerhans giant cells [10] to the genital tract, thus increasing the probability of HIV infection [9]. However, most previous research regarding FGS and inflammation has been at the histopathological level without biopsy [9, 10].

A previous randomized controlled trial detected no effect of active schistosome infection on time-to-a composite indicator of HIV disease progression (first occurrence of a CD4 count of <350 cells/ml, first reported use of antiretroviral treatment, and non-traumatic death) [44]. Conversely, a longitudinal study in Tanzania found that individuals with active schistosome infection at the time of their HIV seroconversion had slower HIV disease progression (as indicated by CD4 count of <350 cells/ml or death) [45]. The authors suggest that this unexpected finding indicated complicated interactions between long-term HIV immunological changes and schistosome co-infections, and that additional studies are needed. Furthermore, a 2016 Cochrane Review found scant, “low quality” evidence that treating helminth infections has beneficial effects on slowing HIV disease progression [46]. By contrast, our study is the first to investigate schistosome-specific antibody status, reflecting either past or current infection, as a factor associated with mortality in HIV+ individuals. Interestingly, we also observed an association between schistosome-specific antibody responses and increased baseline HIV stage in women and viral load in men. More research will be needed to confirm these findings.

Women who were not pregnant at baseline were more likely to be schistosome-specific antibody positive. Previous research, including case reports, ecological studies, descriptive series, and geographical mapping, has indicated an association between S. haematobium infection and decreased fertility in sub-Saharan Africa [47, 48]. In a cross-sectional interview study in Kenya, documented treatment for childhood urogenital S. haematobium among women was associated with decreased fertility in adulthood [49], further highlighting the importance of primary prevention for urogenital schistosomiasis and early treatment.

We also found that schistosome-specific antibody positive responses were associated with male circumcision (significant association for HIV+ men, with a trend for HIV- men). To explain this finding, we evaluated circumcision by education, occupation, income, tribal/linguistic group, and whether the man lived in an urban versus rural area before the age of 16. However, none of these factors attenuated the association between circumcision and ELISA results (data not tabled). This finding warrants further exploration.

Given the high prevalence of a history of schistosomiasis in our study, the associated risk of HIV transmission and death among HIV+ persons positive for schistosome-specific antibody, and other studies indicating an increased risk of HIV transmission/acquisition due to schistosome infection, our findings underscore the importance of schistosomiasis treatment and prevention. Further, we argue for integration of routine parasitological testing and treatment in HIV programs. Treating schistosomiasis has been proposed as a cost-effective addition to HIV prevention and treatment programs, and may contribute to slowing the spread of HIV while reducing schistosomiasis-associated morbidity [21]. Praziquantel treatment for schistosomiasis is safe, including in pregnant women [5, 16], has no reported widespread drug resistance, has only moderate side-effects, and can be dispensed via community-wide mass administration [20]. Additionally, praziquantel may attenuate HIV replication by decreasing systemic inflammation [50] and slow HIV disease progression [19, 46, 50, 51]. HIV+ individuals with delayed schistosomiasis treatment have increased viral loads and lower CD4 T-cell counts compared to those who received early treatment [19], and antihelminthic drugs may act to reduce viral load and increase CD4 levels [51]. In resource-limited countries such as Zambia, more efforts are needed to train health care providers, including HIV practitioners, to detect schistosomiasis and administer praziquantel. It will also be important for policy makers to consider the cost-effectiveness of new methods to detect FGS morbidity versus long-term programmatic benefits.

Our study has limitations. Though ELISA tests can be highly specific and robust laboratory measures of antibodies to schistosome infection [52] and the use of immunoblots to detect schistosomiasis species has been validated for S. mansoni [53, 54] and S. haematobium [55], it is possible that some of the participants were misclassified. In a study in Western Kenya, the SWAP ELISA had a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 57% when compared to fecal egg microscopy, which only detects active infection. The lower specificity of the ELISA is likely associated with identifying people who were previously infected and/or the relatively lower sensitivity of the parasitological method [36]. ELISA cutoff values would have been more compelling if we had known negative controls from Zambian samples. Furthermore, it would have been informative if we had performed sensitive diagnostic procedures, including antigen detection or schistosomiasis PCR, to delineate active infections. Nevertheless, our data support the growing appreciation that the sequelae of schistosomiasis persist beyond the period of active infection. Colposcopy or cervical biopsy to confirm schistosome eggs in urogenital tissue would have enabled definitive diagnosis of FGS although the latter approach has ethical concerns due to creating a genital tract wound in a population of HIV positive or HIV serodiscordant couples.

Schistosomal antibodies were only measured at baseline (along with several other covariates such as viral load), due to funding constraints, and time-varying measures would have been informative to explore how titers changed over time. Type-specific immunoblot testing was only done in women and men who were in M+F- partnerships (primarily to test the hypothesis that female schistosomiasis infection was associated with risk of HIV acquisition in women), and it would have been informative to have species-specific immunoblot data for men and women in M-F+ partnerships. We do not know whether the significantly elevated viral loads (in schistosome-specific antibody positive men) and trend towards higher viral loads (in schistosome-specific antibody positive women) reflect viral loads early in HIV infection or after several years because we do not know time of infection of the HIV+ index partner. The imperfect specificity of the Focus HSV-2 test (sensitivity of 99.5% and specificity of 70.2% in HIV+ and HIV- participants in urban Uganda [56]) is a limitation, and unfortunately due to funding changes, not all RPR results were confirmed by Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay. It is unknown if these sources of potential bias would lead to unmeasured confounding by HSV-2 or RPR status in our analysis. We also lack information on some potentially important covariates, including exposures to environmental water, poor sanitation, prior use of praziquantel, and past socioeconomic status. Finally, we did not have sufficient sample size to look at antiretroviral treatment initiation outcomes (another proxy of HIV disease progression) since this intervention only began in 2007.

Expanded identification and treatment of schistosomiasis are warranted in endemic countries such as Zambia, including in adults in urban areas. In addition to reducing morbidity and mortality associated with schistosomiasis, our findings suggest such efforts might also contribute to prevention of onward HIV transmission and disease progression in HIV+ men and women. As such, the strategy of preventive chemotherapy may have benefits not just for schistosomiasis, but also for HIV. Given the relatively few quantitative studies to date, additional research on schistosomiasis and HIV transmission, acquisition, and disease progression in both men and women, including the potential effects of former infections, are warranted.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

To comply with University of Zambia (UNZA) Biomedical Research Ethics Committee approvals and Zambian Project Management groups approvals, all de-identified study data will be made available from the Zambia Heterosexual Transmission study whose authors may be contacted at emoryreg@rzhrg-mail.org.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation [Grant ID 1005342], the National Institute of Child Health and Development [NICHD R01 HD40125]; National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH R01 66767]; the AIDS International Training and Research Program Fogarty International Center [D43 TW001042]; the Emory Center for AIDS Research [P30 AI050409]; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID R01 AI51231, NIAID R01 AI040951, NIAID R01 AI023980, NIAID R01 AI64060, NIAID R37 AI51231]; the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [5U2GPS000758]; and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative. This study was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, CDC, or the United States Government. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO. Schistosomiasis Fact Sheet 2017 [cited 2017 Nov 7]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs115/en/.

- 2.CDC. Parasites—Schistosomiasis Atlanta, Georgia: CDC; 2010 [cited 2017 October 30]. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/schistosomiasis/index.html.

- 3.Modjarrad K, Zulu I, Redden DT, Njobvu L, Freedman DO, Vermund SH. Prevalence and predictors of intestinal helminth infections among human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected adults in an urban African setting. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(4):777–82. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simoonga C, Kazembe LN, Kristensen TK, Olsen A, Appleton CC, Mubita P, et al. The epidemiology and small-scale spatial heterogeneity of urinary schistosomiasis in Lusaka province, Zambia. Geospatial health. 2008;3(1):57–67. Epub 2008/11/21. 10.4081/gh.2008.232 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Southgate VR, Rollinson D, Tchuente LAT, Hagan P. Towards control of schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Helminthology. 2005;79(3):181–5. 10.1079/joh2005307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helmintiases: number of people treated in 2016. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2017;(92):749–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldmeier H, Krantz I, Poggensee G. Female genital schistosomiasis as a risk-factor for the transmission of HIV. International journal of STD & AIDS. 1994;5(5):368–72. Epub 1994/09/01. 10.1177/095646249400500517 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Mduluza T, Gomo E, Gwanzura L, Mason PR, et al. Simple clinical manifestations of genital Schistosoma haematobium infection in rural Zimbabwean women. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72(3):311–9. Epub 2005/03/18. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poggensee G, Feldmeier H. Female genital schistosomiasis: facts and hypotheses. Acta Trop. 2001;79(3):193–210. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Report of an Informal Working Group Meeting on Urogenital Schistosomiasis and HIV Transmission. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009 [cited 2017 October 30]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70504/1/WHO_HTM_NTD_PCT_2010.5_eng.pdf.

- 11.Kjetland EF, Mduluza T, Ndhlovu PD, Gomo E, Gwanzura L, Midzi N, et al. Genital schistosomiasis in women: a clinical 12-month in vivo study following treatment with praziquantel. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;100(8):740–52. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Kurewa EN, Midzi N, Gomo E, Mduluza T, et al. Prevention of gynecologic contact bleeding and genital sandy patches by childhood anti-schistosomal treatment. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79(1):79–83. Epub 2008/07/09. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Gomo E, Mduluza T, Midzi N, Gwanzura L, et al. Association between genital schistosomiasis and HIV in rural Zimbabwean women. AIDS. 2006;20(4):593–600. 10.1097/01.aids.0000210614.45212.0a . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downs JA, van Dam GJ, Changalucha JM, Corstjens PL, Peck RN, de Dood CJ, et al. Association of Schistosomiasis and HIV infection in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87(5):868–73. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0395 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mbah MLN, Poolman EM, Drain PK, Coffee MP, van der Werf MJ, Galvani AP. HIV and Schistosoma haematobium prevalences correlate in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18(10):1174–9. 10.1111/tmi.12165 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjetland EF, Leutscher PD, Ndhlovu PD. A review of female genital schistosomiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28(2):58–65. 10.1016/j.pt.2011.10.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mbabazi PS, Andan O, Fitzgerald DW, Chitsulo L, Engels D, Downs JA. Examining the relationship between urogenital schistosomiasis and HIV infection. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2011;5(12):e1396 Epub 2011/12/14. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001396 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stecher CW, Kallestrup P, Kjetland EF, Vennervald B, Petersen E. Considering treatment of male genital schistosomiasis as a tool for future HIV prevention: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2015;60(7):839–48. 10.1007/s00038-015-0714-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kallestrup P, Zinyama R, Gomo E, Butterworth AE, Mudenge B, van Dam GJ, et al. Schistosomiasis and HIV-1 infection in rural Zimbabwe: effect of treatment of schistosomiasis on CD4 cell count and plasma HIV-1 RNA load. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2005;192(11):1956–61. Epub 2005/11/04. 10.1086/497696 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ndeffo Mbah ML, Kjetland EF, Atkins KE, Poolman EM, Orenstein EW, Meyers LA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a community-based intervention for reducing the transmission of Schistosoma haematobium and HIV in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(19):7952–7. 10.1073/pnas.1221396110 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawers L, Stillwaggon E, Hertz T. Cofactor infections and HIV epidemics in developing countries: implications for treatment. AIDS care. 2008;20(4):488–94. Epub 2008/05/02. 10.1080/09540120701868311 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO. Statement–WHO Working Group on Urogenital Schistosomiasis and HIV Transmission: WHO Press; 2009 [cited 2018 Oct 2]. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/integrated_media_urogenital_schistosomiasis/en/.

- 23.Central Statistical Office (CSO) [Zambia], Ministry of Health (MOH) [Zambia], International. I. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2013–14. Rockville, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, and ICF International.; 2015.

- 24.Mwanakasale V, Vounatsou P, Sukwa TY, Ziba M, Ernest A, Tanner M. Interactions between Schistosoma haematobium and human immunodeficiency virus type 1: The effects of coinfection on treatment outcomes in rural Zambia. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2003;69(4):420–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agnew-Blais J, Carnevale J, Gropper A, Shilika E, Bail R, Ngoma M. Schistosomiasis Haematobium Prevalence and Risk Factors in a School-age Population of Peri-urban Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2010;56(4):247–53. 10.1093/tropej/fmp106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wall KM, Kilembe W, Nizam A, Vwalika C, Kautzman M, Chomba E, et al. Promotion of couples' voluntary HIV counselling and testing in Lusaka, Zambia by influence network leaders and agents. BMJ open. 2012;2(5). Epub 2012/09/08. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001171 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kempf MC, Allen S, Zulu I, Kancheya N, Stephenson R, Brill I, et al. Enrollment and retention of HIV discordant couples in Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2008;47(1):116–25. Epub 2007/11/22. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815d2f3f . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chomba E, Allen S, Kanweka W, Tichacek A, Cox G, Shutes E, et al. Evolution of couples' voluntary counseling and testing for HIV in Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2008;47(1):108–15. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b2d67 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boeras DI, Luisi N, Karita E, McKinney S, Sharkey T, Keeling M, et al. Indeterminate and discrepant rapid HIV test results in couples' HIV testing and counselling centres in Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:18 10.1186/1758-2652-14-18 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephenson R, Barker J, Cramer R, Hall MA, Karita E, Chomba E, et al. The demographic profile of sero-discordant couples enrolled in clinical research in Rwanda and Zambia. AIDS care. 2008;20(3):395–405. Epub 2008/03/21. 10.1080/09540120701593497 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dionne-Odom J, Karita E, Kilembe W, Henderson F, Vwalika B, Bayingana R, et al. Syphilis treatment response among HIV-discordant couples in Zambia and Rwanda. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;56(12):1829–37. Epub 2013/03/15. 10.1093/cid/cit146 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrow RA, Friedrich D, Meier A, Corey L. Use of "biokit HSV-2 Rapid Assay" to improve the positive predictive value of Focus HerpeSelect HSV-2 ELISA. BMC infectious diseases. 2005;5:84 Epub 2005/10/18. 10.1186/1471-2334-5-84 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wall KM, Kilembe W, Vwalika B, Haddad LB, Lakhi S, Onwubiko U, et al. Sustained effect of couples' HIV counselling and testing on risk reduction among Zambian HIV serodiscordant couples. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(4):259–66. 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052743 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peters PJ, Zulu I, Kancheya NG, Lakhi S, Chomba E, Vwalika C, et al. Modified Kigali combined staging predicts risk of mortality in HIV-infected adults in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2008;24(7):919–24. Epub 2008/07/03. 10.1089/aid.2007.0297 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trask SA, Derdeyn CA, Fideli U, Chen Y, Meleth S, Kasolo F, et al. Molecular epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission in a heterosexual cohort of discordant couples in Zambia. J Virol. 2002;76(1):397–405. 10.1128/JVI.76.1.397-405.2002 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shane HL, Verani JR, Abudho B, Montgomery SP, Blackstock AJ, Mwinzi PN, et al. Evaluation of urine CCA assays for detection of Schistosoma mansoni infection in Western Kenya. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2011;5(1):e951 Epub 2011/02/02. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000951 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsang VC, Wilkins PP. Immunodiagnosis of schistosomiasis. Immunological investigations. 1997;26(1–2):175–88. Epub 1997/01/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wall KM, Kilembe W, Vwalika B, Haddad LB, Hunter E, Lakhi S, et al. Risk of heterosexual HIV transmission attributable to sexually transmitted infections and non-specific genital inflammation in Zambian discordant couples, 1994–2012. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(5):1593–606. 10.1093/ije/dyx045 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalinda C, Chimbari MJ, Mukaratirwa S. Schistosomiasis in Zambia: a systematic review of past and present experiences. Infectious diseases of poverty. 2018;7(1):41 Epub 2018/05/01. 10.1186/s40249-018-0424-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leutscher PDC, Pedersen M, Raharisolo C, Jensen JS, Hoffmann S, Lisse I, et al. Increased prevalence of leukocytes and elevated cytokine levels in semen from Schistosoma haematobium-infected individuals. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191(10):1639–47. :000228465000009. 10.1086/429334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Secor WE, Shah A, Mwinzi PM, Ndenga BA, Watta CO, Karanja DM. Increased density of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 on the surfaces of CD4(+) T cells and monocytes of patients with Schistosoma mansoni infection. Infection and immunity. 2003;71(11):6668–71. Epub 2003/10/24. 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6668-6671.2003 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Downs JA, Dupnik KM, van Dam GJ, Urassa M, Lutonja P, Kornelis D, et al. Effects of schistosomiasis on susceptibility to HIV-1 infection and HIV-1 viral load at HIV-1 seroconversion: A nested case-control study. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2017;11(9):e0005968 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005968 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helling-Giese G, Sjaastad A, Poggensee G, Kjetland EF, Richter J, Chitsulo L, et al. Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS): relationship between gynecological and histopathological findings. Acta Trop. 1996;62(4):257–67. Epub 1996/12/30. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walson J, Singa B, Sangare L, Naulikha J, Piper B, Richardson B, et al. Empiric deworming to delay HIV disease progression in adults with HIV who are ineligible for initiation of antiretroviral treatment (the HEAT study): a multi-site, randomised trial. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2012;12(12):925–32. Epub 2012/09/14. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70207-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colombe S, Machemba R, Mtenga B, Lutonja P, Kalluvya SE, de Dood CJ, et al. Impact of schistosome infection on long-term HIV/AIDS outcomes. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2018;12(7):e0006613 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Means AR, Burns P, Sinclair D, Walson JL. Antihelminthics in helminth-endemic areas: effects on HIV disease progression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD006419 10.1002/14651858.CD006419.pub4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woodall PA, Kramer MR. Schistosomiasis and Infertility in East Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018. Epub 2018/01/10. 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0280 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helling-Giese G, Kjetland EF, Gundersen SG, Poggensee G, Richter J, Krantz I, et al. Schistosomiasis in women: manifestations in the upper reproductive tract. Acta Trop. 1996;62(4):225–38. Epub 1996/12/30. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller-Fellows SC, Howard L, Kramer R, Hildebrand V, Furin J, Mutuku FM, et al. Cross-sectional interview study of fertility, pregnancy, and urogenital schistosomiasis in coastal Kenya: Documented treatment in childhood is associated with reduced odds of subfertility among adult women. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2017;11(11):e0006101 Epub 2017/11/28. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006101 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Erikstrup C, Kallestrup P, Zinyama-Gutsire RB, Gomo E, van Dam GJ, Deelder AM, et al. Schistosomiasis and infection with human immunodeficiency virus 1 in rural Zimbabwe: systemic inflammation during co-infection and after treatment for schistosomiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79(3):331–7. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walson JL, Herrin BR, John-Stewart G. Deworming helminth co-infected individuals for delaying HIV disease progression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):Cd006419 Epub 2009/07/10. 10.1002/14651858.CD006419.pub3 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doenhoff MJ, Chiodini PL, Hamilton JV. Specific and sensitive diagnosis of schistosome infection: can it be done with antibodies? Trends Parasitol. 2004;20(1):35–9. Epub 2004/01/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maddison SE, Slemenda SB, Tsang VC, Pollard RA. Serodiagnosis of Schistosoma mansoni with microsomal adult worm antigen in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using a standard curve developed with a reference serum pool. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985;34(3):484–94. Epub 1985/05/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsang VC, Hancock K, Maddison SE, Beatty AL, Moss DM. Demonstration of species-specific and cross-reactive components of the adult microsomal antigens from Schistosoma mansoni and S. japonicum (MAMA and JAMA). Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md: 1950). 1984;132(5):2607–13. Epub 1984/05/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sulahian A, Garin YJ, Izri A, Verret C, Delaunay P, van Gool T, et al. Development and evaluation of a Western blot kit for diagnosis of schistosomiasis. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology. 2005;12(4):548–51. Epub 2005/04/09. 10.1128/CDLI.12.4.548-551.2005 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lingappa J, Nakku-Joloba E, Magaret A, Friedrich D, Dragavon J, Kambugu F, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of herpes simplex virus-2 serological assays among HIV-infected and uninfected urban Ugandans. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2010;21(9):611–6. Epub 2010/11/26. 10.1258/ijsa.2009.008477 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

To comply with University of Zambia (UNZA) Biomedical Research Ethics Committee approvals and Zambian Project Management groups approvals, all de-identified study data will be made available from the Zambia Heterosexual Transmission study whose authors may be contacted at emoryreg@rzhrg-mail.org.