Abstract

Background:

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) is underutilized in correctional settings, and those receiving MMT in the community often undergo withdrawal upon incarceration. Federal and state regulations present barriers to providing methadone in correctional facilities. For this investigation, a community provider administered methadone to inmates who had been receiving methadone prior to incarceration. We hypothesized that inmates continued on MMT would have improved behavior during incarceration and post-release.

Methods:

This open label quasi-experimental trial (n = 382) compared MMT continuation throughout incarceration (n = 184) to an administrative control group (i.e., forced withdrawal; n = 198) on disciplinary tickets and other program attendance during incarceration. Post-release, re-engagement in community-based MMT and 6-month recidivism outcomes were evaluated.

Results:

Inmates in the MMT continuation group versus controls were less likely to receive disciplinary tickets (O.R.=0.32) but no more likely to attend other programs while incarcerated. MMT continuation increased engagement with a community MMT provider within 1 day of release (O.R.=32.04), and 40.6% of MMT participants re-engaged within the first 30 days (versus 10.1% of controls). Overall, re-engagement in MMT was not associated with recidivism. However, among a subset of inmates who received MMT post-incarceration from the jail MMT provider (n = 69), re-engagement with that provider was associated with reduced risk of arrest, new charges, and re-incarceration compared to those who did not re-engage.

Conclusions:

Results support interventions that facilitate continuity of MMT during and after incarceration. Engagement of a community provider is feasible and can improve access to methadone in correctional facilities.

Keywords: methadone maintenance, treatment, incarceration, recidivism, opioid use disorder

Introduction

Opioid use, including heroin and non-medical use of prescription opioids, is a significant public health problem in the U.S., associated with high rates of dependence (Grant et al., 2015), death by overdose (Centers for Disease Control, 2015), and healthcare costs (Birnbaum et al., 2011). Rates of opioid use in the criminal justice system are exceedingly higher than in the general population (Mumola and Karberg, 2006), with estimates that up to 35% of prisoners have an opioid use disorder (OUD; Mir et al., 2015). Given that a history of injection drug use predicts higher rates of recidivism compared to other substances (Håkansson and Berglund, 2012) and opioid use increases risk of overdose after incarceration (Merrall et al., 2010), there is a critical need to treat OUDs in criminal justice settings to prevent repeated incarcerations and improve health outcomes in this population.

There is robust evidence suggesting that methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) is effective for reducing opioid use and its consequences (Fullerton et al., 2014). Correctional facilities that induce inmates with OUDs on MMT (Gordon et al., 2008; Johnson, et al., 2001; Kinlock et al., 2009, 2008, 2007) show reduced illicit drug use and risk behaviors (e.g., institutional misconduct) during incarceration, as well as increased re-engagement in community-based MMT, reduced illicit drug use post-release, and sometimes, reduced re-arrest and reincarceration (see Hedrich et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2016 for review). Very few correctional facilities continue providing MMT that was initiated in the community. Most correctional facilities require forced withdrawal from methadone upon incarceration, which is accompanied by aversive symptoms (Aronowitz and Laurent, 2016), reduces the chances of engaging in MMT post-release (Fu et al., 2013; Maradiaga et al., 2016), and may decrease tolerance and increase risk for overdose post-release (Degenhardt et al., 2014). The few studies examining the impact of continuing MMT throughout incarceration show higher rates of re-engagement in community-based MMT post-release, lower illicit drug use (Rich et al., 2015), and a longer time before re-arrest (Westerberg et al., 2016) compared to inmates who underwent forced withdrawal or detoxification.

There are, however, barriers to continuing MMT in correctional facilities, such as negative attitudes toward pharmacological treatments (Friedmann et al., 2012) and difficulties having controlled substances in the facility (Rich et al., 2005). In addition, current federal and state regulations subject methadone to five tiers of regulation including 1) the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act that applies to all prescription drugs, 2) the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) to prevent the illicit use of schedule II controlled substances, 3) the Department of Health and Human Services and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to control which settings methadone may be used in, 4) state governmental standards, and 5) county/municipal standards. As a result, MMT is underutilized in the criminal justice system, with less than half of U.S. prisons offering MMT (which is mostly reserved for pregnant women and short-term detoxification; Wakeman and Rich, 2015) and 12% of jails continuing previously received methadone during incarceration (Fiscella et al., 2004).

Present Study

A state-funded initiative led by the Connecticut Department of Correction (CT DOC) in partnership with the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DMHAS) and the APT Foundation of New Haven (methadone provider) implemented an open-label pilot study examining the feasibility and effectiveness of continuing to provide MMT throughout incarceration for people receiving community-based MMT. Current legislation in Connecticut prohibited the provision of methadone outside a licensed narcotic treatment program (i.e., a methadone clinic). To overcome this barrier, a licensed narcotic treatment program in the community (the APT Foundation) was utilized to bring methadone into the jail and administer it to inmates in compliance with state and federal regulations. The Department of Public Health approved the jail pharmacy as a satellite methadone clinic of the APT Foundation. Therefore, the Connecticut Department of Correction was designated as a licensed opioid treatment program, which allowed methadone to be administered within its correctional facilities. The State Drug Control and Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), which regulates medication assisted treatments in Connecticut, approved this program prior to its implementation.

Using an open-label quasi-experimental design for our evaluation, we accessed an equivalent control group from administrative records to compare to the MMT group. We hypothesized that inmates continued on MMT, relative to those who underwent withdrawal, would have improved behavior during incarceration (i.e., fewer disciplinary tickets, higher attendance in other programs) and post-release (i.e., higher re-engagement in community-based MMT). Secondarily, we hypothesized that for inmates continued on MMT during incarceration, re-engagement with a community-based provider post-release would be associated with reduced recidivism. Finally, we also evaluated outcomes among the subsample of individuals who had the same MMT provider before, during, and post-incarceration.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Inmates were recruited from an all-male jail facility in Connecticut from October 2013 to June 2015 and consented to methadone treatment provided by the APT Foundation, the primary community-based MMT provider in the greater New Haven area with a census of 4,500 patients. Inclusion criteria included: DSM-IV criteria for opioid dependence, and having received MMT in the community within 5 days prior to incarceration (with proof of enrollment). Exclusion criteria included: bond over $50,000, a sentence > 2 years, serious medical problems, or high security risk (i.e., protective custody, history of violence with inmates/staff in the program). These exclusion criteria reduced the likelihood that participants would be transferred to a prison or medical facility and reduced threats to security during daily movement within the facility. To conduct the program evaluation, Institutional Review Board approval for a retrospective medical record review was received from Yale University in conjunction with Connecticut State approvals [DOC, DHMAS, Court Support Services Division (CSSD)], and the APT Foundation.

Open-label MMT Continuation

Upon being arrested, all inmates completed an intake with nursing staff in the jail to assess basic mental, substance use, and physical health needs, including DSM-IV criteria for opiate dependence. During this intake, inmates were asked if they received MMT in the community prior to getting arrested and if so, whether they wanted to continue MMT in the jail. If they said yes, APT staff were notified and met with the inmates to get contact details and a release of information for the community provider, and to sign a treatment consent to receive MMT in the jail. Inmates also consented to attend monthly counseling and to undergo random oral drug testing as part of the MMT program.

APT staff then contacted inmates’ community methadone clinic to confirm enrollment just prior to incarceration as well as the most recent dose of methadone. Participants were required to receive their first dose within 5 days of their last community dose. Initial dose amount was based on the number of days since the last dose. If APT staff confirmed with community providers right away, an inmates’ most recent dose was continued in the jail and only adjusted if clinically indicated. Participants who had missed doses were typically started on a lower dose and titrated up to their full dose. The primary reason for missed dosing was a delay in the confirmation from the community provider (i.e., incarcerated over the weekend or APT staff could not get in touch with the community provider right away). All dosing was approved by a prescribing physician at the APT Foundation. The majority of participants in the MMT group had received community-based MMT from the APT Foundation prior to incarceration (n = 120; 59%).

MMT participants were housed in a specific unit in the jail. The APT Foundation provided and administered the methadone during incarceration. Methadone was dispensed into patient-labeled bottles at the APT Foundation clinic, placed in a locked box, and transported into the jail by two APT staff. Upon arriving at the jail, a custody officer met the APT staff at the jail entrance, checked the staff in and counted the bottles containing methadone, and permitted the staff to proceed to the pharmacy. Methadone was provided daily at 1pm Monday through Friday and 9am on Saturday and Sunday. Participants were escorted to the medical unit to receive their dose, with an addictions counselor and correctional officer present. Inmates drank juice after being dosed and staff completed a mouth check to prevent diversion. Upon leaving the jail, a custody officer examined all bottles to ensure the number empty matched the number of inmates on the list who received methadone.

Participants could discontinue MMT at any time (at which point they started a two-week taper). Similarly, participants who were transferred to another facility were tapered beforehand. In addition to daily methadone, participants attended a monthly counseling group co-led by APT Foundation and jail staff. Though release from jail was sometimes unpredictable, APT staff tracked release dates to ensure inmates who needed to make appointments with community providers did so before being released. Upon release from jail, participants planning to return to APT for methadone were informed that they could walk in and be dosed at an APT community clinic. Participants planning to return to other programs were provided with an appointment at a community location of their choice. To prevent lapses for those inmates who re-engaged with a non-APT provider post-release, APT also offered daily dosing in the community until participants could connect with their preferred clinic. The APT Foundation was partially compensated to provide methadone in the jail, with state funds supporting approximately 25% of standards costs.

Control Group/Forced Withdrawal

To create an equivalent control group, we reviewed CT DOC and DDAP administrative records of people incarcerated between January 2012 and June 2015 (n = 6,905) to identify inmates who received community-based MMT just prior to incarceration at the same CT DOC facility, met the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as MMT participants, and did not participate in MMT continuation during incarceration (n = 198). This jail’s standard of care for inmates with opioid dependence involved forced withdrawal, which sometimes included medical assistance (i.e., over-the-counter pain reliever) and less commonly, a short-term buprenorphine taper for instances of severe withdrawal symptoms. These details were not documented in the CT DOC medical record.

Measures

Data on treatment and control group participants were obtained from Connecticut administrative records and linked using first name, last name, date of birth, and inmate number.

Demographics.

We obtained demographics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity) and time served at the host jail from CT DOC records. Length of incarceration was calculated by taking the difference of release date and initial incarceration date.

Methadone Dose.

We obtained data on daily dose amounts (mg) administered during incarceration to MMT continuation participants from the APT Foundation.

During Incarceration Outcomes.

The number of Disciplinary Tickets (e.g., disobeying orders, possessing contraband, fighting) and information on Other DOC Program Attendance (substance-related or otherwise) during incarceration was collected from CT DOC records and coded as (0 = none, 1 = any).

Re-engagement in MMT.

Data on whether participants re-engaged in community-based MMT during the 6 months post-release and date of re-engagement was collected from the APT Foundation for participants who received MMT there as well as Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Data and Performance (DDAP) records for participants who used other community MMT facilities. Rate of re-engagement was calculated by taking the difference between the date of release from incarceration and date of re-engagement (i.e., re-engagement within 1 day, 30 days, 180 days).

Recidivism.

Data on recidivism was collected via a record request from CSSD, an organization that manages pretrial, probation, and other court services for adults in Connecticut. Recidivism outcomes (all dichotomous) included re-arrest, reincarceration, and receipt of new charges (drug, violent, felony, misdemeanor) within 6 months post-release. Drug charges included driving under the influence of alcohol, possession/attempted sale/sale of an illicit substance, or possession of drug paraphernalia. Violent charges included weapons charges, or if the charge involved assault, strangulation, harming/threatening to harm another person, rape, sexual assault, or child sexual abuse. Violations of probation were not included in recidivism outcomes. CSSD was missing data for two MMT participants.

Data Analysis Plan

Data were analyzed using SPSS. We examined baseline differences in the treatment and control groups using chi square analyses. Then, we examined whether treatment and control group status differed on outcomes during incarceration (i.e., disciplinary tickets, other program attendance) as well as post-release (i.e., re-engagement in community based MMT) using logistic regression, and ran a Kaplan Meier survival analysis (log-rank) to examine time to re-engagement and recidivism within 180 days post-release. We also used logistic regression to analyze the effect of post-release re-engagement in MMT on recidivism among MMT participants.

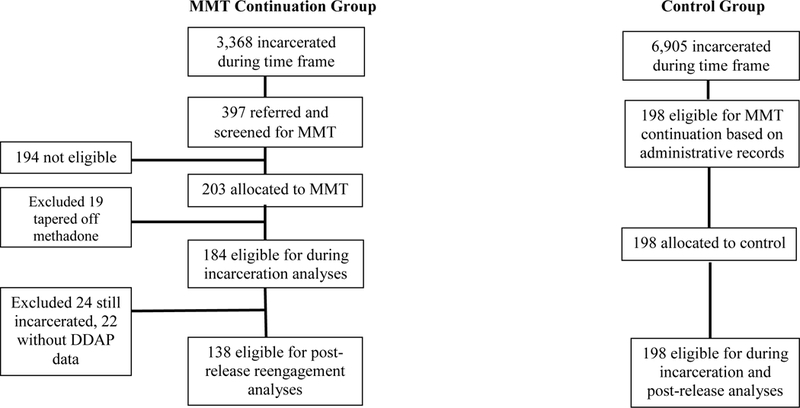

For outcomes of disciplinary tickets and other program attendance, we excluded people who were tapered (n = 19) from analyses (n = 184; see Figure 1). With regard to post-release outcomes, we further excluded people who were still incarcerated at the end of the data collection period (n = 24), or were missing data in the DDAP database (n = 22) resulting in a treatment sample of 138 for re-engagement and recidivism analyses. When analyzing re-engagement outcomes on the subsample of participants who received MMT from the APT Foundation before, during, and post-incarceration (i.e., the APT subsample, n = 93), we compared those in the APT subsample with re-engagement data (n = 84) to the control group (n = 198). For recidivism analyses, only individuals who had valid re-engagement data (treatment n = 138) and had been in the community for at least 6 months (i.e., had equivalent time to reoffend) after completion of MMT continuation were included (treatment n = 100). Finally, we conducted recidivism analyses on the APT subsample who were in the community for at least 6 months after completing MMT continuation (n = 69).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram. This figure shows treatment and control group allocation. MMT = Methadone Maintenance Treatment.

The MMT continuation and control group were comparable on baseline demographics (see Table 1). Nonetheless, all baseline variables were assessed as potential covariates across all analyses. Results were not substantially altered with covariates and they were removed from final models.

Table 1.

Demographics of treatment and control group

| MMT (n = 184) |

Forced Withdrawal (n = 198) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | M/n | SD/% | M/n | SD/% | p |

| Age | 36.16 | (9.63) | 37.01 | (9.13) | .377 |

| Race | .705 | ||||

| White | 145 | (78.8) | 152 | (76.8) | |

| Black | 18 | (9.8) | 18 | (9.1) | |

| Hispanic | 21 | (11.4) | 27 | (13.6) | |

| Native American | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.5) | |

| Marital Status | .559 | ||||

| Married | 12 | (6.5) | 16 | (8.1) | |

| Not married | 172 | (93.5) | 182 | (91.9) | |

| Medical Insurance | < .001 | ||||

| Uninsured | 107 | (58.2) | 166 | (83.8) | |

| Medicaid | 52 | (28.3) | 17 | (8.6) | |

| Private | 2 | (1.1) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Uncategorized | 23 | (12.5) | 15 | (7.6) | |

| Host Jail Incarc. Days | 59.80 | (76.77) | 55.03 | (73.54) | .548 |

Note. MMT = Methadone Maintenance Treatment.

Results

A consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) diagram (see Figure 1) shows treatment allocation and retention. The MMT continuation (n = 184) and control (n = 198) groups were male, mostly Caucasian, and around 36 to 37 years old on average (see Table 1). The only baseline difference between groups was that MMT continuation participants were more likely to be insured (see Table 1). Of note, the MMT group analyzed on post-release outcomes (n = 138) did not differ significantly from the larger group analyzed during incarceration (n = 184) on any baseline characteristics. MMT continuation participants received an average methadone dose of 68.32mg (SD = 26.50) during incarceration. Additional dose information is displayed in Supplemental Table 1. APT and custody staff monitored diversion throughout the study. There were no reported instances of diversion.

With regard to receipt of disciplinary tickets during incarceration (Table 2), participants in the MMT group were about 3 times less likely (OR = 0.32) to receive disciplinary tickets compared to those who received MMT continuation. There was no difference in the odds of attending other treatment programs during incarceration between treatment and control groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Odds ratios for disciplinary tickets, other program attendance, and community treatment re-engagement outcomes

| Incarceration Outcomes | Re-engagement Outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disciplinary Tickets |

Other Program Attendance |

≤ 1 day | ≤ 30 days | ||

| OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | ||

| MMT (n = 184) | 0.32* [.13, .76] | 1.58 [.73, 3.40] | 32.04** [7.55, 136.01] | 6.08** [3.43, 10.79] | |

| APT sample (n = 84) | ------- | ------- | 39.20** [9.00, 170.69] | 6.36** [3.37, 11.98] | |

| Control | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

Note. MMT = Methadone Maintenance Treatment. +p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .001

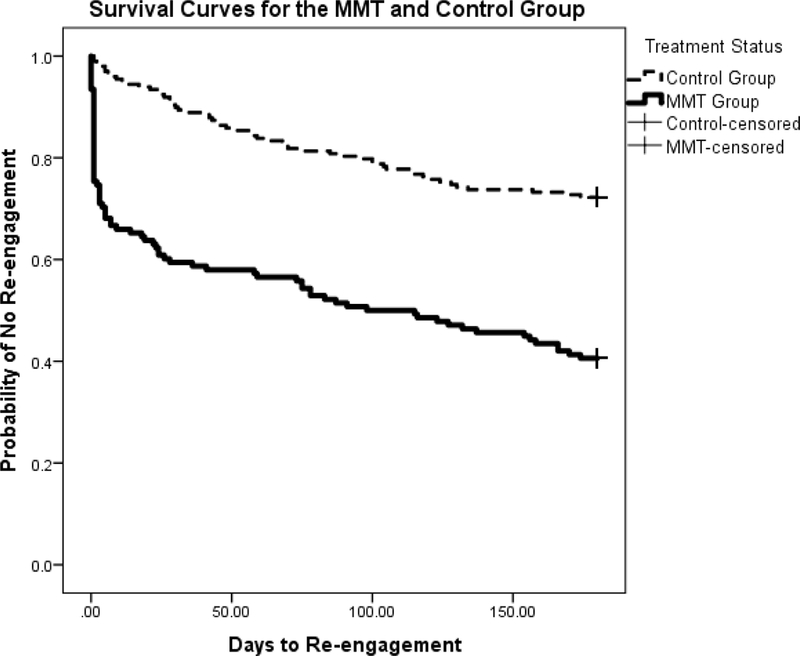

The MMT continuation group had significantly greater odds of re-engagement in community-based MMT within 1 day and 30 days post-release compared to the control group (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). By 30 days, 40.6% of the MMT continuation and 10.1% of the control group had re-engaged (O.R.=6.08). Results were consistent when analyzing the APT subsample; participants in the APT subsample had greater odds of re-engagement in MMT within 1 day and 30 days post-release compared to the control group. By 30 days, 41.7% of the APT subsample had re-engaged compared to 10.1% of the control group (O.R.=6.36). Results of the survival analysis (see Figure 2) showed significantly different time to re-engagement for the MMT continuation and control groups within 180 days post-release, χ2(1) = 42.55, p < .001. Examination of the curves indicate the those in MMT group had high engagement immediately following release, and then the curves remain essentially parallel with small gains in engagement occurring in both groups over the 6-month period. Of note, there were no significant differences among insurance status categories (none, Medicaid, private, uncategorized) and re-engagement post-release.

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier Survival Analysis comparing MMT to control group on time to re-engagement within 180 days post-release. This figure shows that inmates in the MMT group had significantly fewer days to re-engagement (lower probability of not re-engaging) compared to the control group.

With regard to recidivism, we only analyzed participants in the MMT continuation group who were in the community for at least 6 months post-release (n = 100). There were no significant differences in re-arrest rates (p = .321), or obtaining new charges (p = .220), new drug-related charges (p = .402), new violent charges (p = .806), new misdemeanor charges (p = .242), new felony charges (p = .918), or becoming reincarcerated (p = .761) for those MMT continuation participants who re-engaged in MMT within 3 months post-release compared to those who did not re-engage. There were also no differences in the survival analysis examining days to rearrest. Among the APT subsample (n = 69), there were significant associations with re-engagement and recidivism (Table 3, Supplementary Table 3). Those who re-engaged with the jail-MMT provider within 3 months post-release had reduced risk of re-arrest, new charges (i.e., including drug-related, violent, felony, misdemeanor), and re-incarceration.

Table 3.

Effect of re-engagement in community-based Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) post-release on recidivism in APT subsample.

| Recidivism 6 months Post-release | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrest | New Charges | New Drug-related Charges |

New Violent Charges |

New Felony Charges |

New Misdemeanor Charges |

Reincarcerated | |

| OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | OR [95% CI] | |

| Did not Re-engage | 3.70* [1.25; 11.00] | 3.27* [1.12; 9.58] | 10.22* [1.07; 97.77] | 7.26+ [.71; 74.31] | 5.50* [1.23; 24.63] | 3.08* [1.04; 9.19] | 13.53* [1.47; 124.31] |

| Re-engaged | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

Note. This sample includes people who received MMT via the APT Foundation prior to and during incarceration and who were in the community for at least 6 months after incarceration (n = 69).

Re-engagement rates presented here are within the subsample of 69 participants; 47 re-engaged in MMT with the APT Foundation and 22 did not re-engage.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .001

Discussion

This study is among the first to investigate the impact of continuing MMT during incarceration for people previously receiving MMT in the community, and to utilize a community provider to address potential barriers regarding the provision of methadone in correctional facilities. Results suggest high feasibility and positive effects on behavior during incarceration and after release. People who received MMT during incarceration were less likely to receive disciplinary tickets while incarcerated and more likely to re-engage in community-based MMT after release compared to those who underwent forced withdrawal from methadone. In addition, inmates who engaged in MMT with the same provider before, during, and after incarceration were less likely to recidivate or become reincarcerated.

Continuing to receive MMT throughout incarceration was associated with fewer disciplinary tickets during incarceration. There are numerous factors influencing disruptive behavior during incarceration, including access to treatment (Tewksbury et al., 2014). Our results suggest that continuing MMT throughout incarceration may reduce aversive physiological withdrawal symptoms and the distress that accompanies them, fostering more stable mental health and behavior and thereby reducing behavior problems. Consistent with studies that have initiated MMT during incarceration for inmates with opioid use disorders (see Hedrich et al., 2012 for review), we found that continuing MMT during incarceration for people previously receiving MMT in the community was associated with significantly greater likelihood of re-engaging in community-based MMT within 1, 30, and 180 days post-release. The survival curves examining re-engagement over a 6-month period indicate the differences in re-engagement between the MMT and control group happened quickly following release from incarceration. Notably, only two control group participants (1%) re-engaged in community-based MMT on the first day after release compared to about 25% of MMT participants, and only 10% had engaged 30 days post-release compared to 40% of MMT participants. This is concerning, given the elevated chance of overdose in the first month following release from incarceration (Degenhardt et al., 2014; Merrall et al., 2010). Effect sizes were similar for our overall treatment sample and APT subsample who received MMT from a consistent provider, however, participants receiving MMT from a consistent provider did not necessarily have higher rates of re-engagement compared to the overall treatment sample. The process of transferring recently released inmates to community-based MMT providers is challenging and further work is needed to increase rates of engagement. The results of this study highlight the effectiveness of continuing to offer methadone maintenance treatments during incarceration in facilitating a seamless transition between incarceration and community-based treatment in the reentry period after release.

We did not find an effect of post-release re-engagement in MMT on recidivism when examining the entire MMT continuation group. Other studies of MMT continuation have found mixed results with regard to recidivism (Rich et al., 2015; Westerberg et al., 2016). However, we did find that post-release re-engagement in MMT with the APT Foundation was associated with lower odds of being re-arrested and reincarcerated. Failing to reengage in MMT with the APT Foundation within 90 days post-release was associated with 3 times greater odds of re-arrest and obtaining new and misdemeanor charges, over 5 times greater odds of obtaining new felony charges, 10 times greater odds of obtaining new drug-related charges, and about 14 times greater odds of being reincarcerated within 6 months post-release. It may be important to consider the benefits of continuity in treatment organization, location, and staff in addition to continuation of MMT on recidivism outcomes. The APT Foundation served as the primary community MMT provider in our area and the in-jail MMT provider; they may have provided superior treatment compared to other locations. People who are connected with known treatment providers in a familiar location post-release may have less uncertainty and stress regarding MMT, and be more likely to enact other positive behavior changes. Alternatively, these findings could represent selection effects. Most research examining factors that impact MMT outcomes have focused on individual factors, however, program characteristics are also important (Kinlock et al., 2013).

Because there have been mixed results with regard to the impact of MMT continuation on recidivism, it is important to consider that MMT continuation should be supplemented with intervention strategies that target criminogenic in addition to addiction needs. People who are arrested and incarcerated while receiving MMT in the community are a high-risk group of individuals who despite receiving effective treatment for addiction, still engaged in crime that led to arrest. Engaging in more crime prior to entering MMT is a risk factor for treatment non-compliance (Kelly et al., 2011). People with a history of opioid use may still be involved in environments wherein crime is common, associate with people who commit crime, or engage in difficult-to-change criminal behavior patterns. Therefore, people who are arrested while receiving MMT may benefit from intervention around risk factors that lead to incarceration. This is an important direction for future intervention development research.

Limitations

Though this study contributes to the growing body of research examining the effectiveness of continuing inmates on MMT during incarceration, there are several limitations. This was an open-label quasi-experimental study, utilizing an administrative control group. While differences between the groups did not impact on outcomes, future work should incorporate randomized clinical trial designs to minimize selection bias and account for potential confounding variables (e.g., criminal history severity). Notably, other studies suggest selection bias may be less concerning when examining MMT during incarceration (Rich et al., 2015). With regard to re-engagement in community-based MMT, not all community-based MMT programs consistently reported post-release re-engagement rates for DDAP records. We mitigated this potential bias by limiting our analysis to participants who attended DDAP-reporting facilities. We did not collect mortality data as part of this project, but future studies of MMT should incorporate this outcome considering the high potential for opioid overdose after release from incarceration. Finally, we were unable to quantify the experience of forced withdrawal in the control group. Medical records were absent of any details regarding opioid withdrawal or treatment, likely indicating no treatment.

Conclusions

MMT continuation is feasible to implement in correctional settings, may reduce institutional misconduct during incarceration, and greatly increases the likelihood of post-release re-engagement in MMT. There is also preliminary evidence that people who participate in MMT continuation and re-engage in MMT post-release may have reduced chances of being re-arrested and reincarcerated, though this finding only applied to a subsample of inmates receiving MMT from the same community provider prior to, during, and after incarceration. Overall, these finding highlight that engaging a community provider to dispense methadone in a correctional setting is feasible and effective, and may serve to increase access to methadone in correctional facilities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Connecticut Department of Correction, Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, APT Foundation of New Haven, and TI026330 (SAMSHA to SAM). The work described in this article does not express the views of the State of Connecticut, the APT Foundation, or SAMSHA. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors.

References

- Aronowitz S V, Laurent J (2016) Screaming behind a door: The experiences of individuals incarcerated without medication-assisted treatment. J Correct Heal Care 22:98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL (2011) Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med 12:657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (2015) Overdose Death Rates.

- Degenhardt L, Larney S, Kimber J, Gisev N, Farrell M, Dobbins T, Weatherburn DJ, Gibson A, Mattick R, Butler T, Burns L (2014) The impact of opioid substitution therapy on mortality post-release from prison: Retrospective data linkage study. Addiction 109:1306–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Moore A, Engerman J, Meldrum S (2004) Jail management of arrestees/inmates enrolled in community methadone maintenance programs. J Urban Heal Bull New York Acad Med 81:645–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Hoskinson R, Gordon M, Schwartz R, Kinlock T, Knight K, Flynn PM, Welsh WN, Stein LAR, Sacks S, O’Connell DJ, Knudsen HK, Shafer MS, Hall E, Frisman LK (2012) Medication-assisted treatment in criminal justice agencies affiliated with the criminal justice-drug abuse treatment studies (CJ-DATS): Availability, barriers, and intentions. Subst Abus 33:9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JJB, Zaller ND, Yokell MAB, Bazazi AR, Rich JD (2013) Forced withdrawal from methadone maintenance therapy in criminal justice settings: A critical treatment barrier in the United States. J Subst Abuse Treat 44:502–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton CA, Kim M.; Thomas Cindy Parks; Lyman DR.; Montejano LB.; Dougherty RH.; Daniels AS.; Ghose SS.; Delphin-Rittmon ME (2014) Medication-assisted treatment with methadone: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv 65:146–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, O’Grady KE (2008) A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: Findings at 6 months post-release. Addiction 103:1333–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Smith SM, Pickering RP, Huang B, Hasin DS (2015) Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 20852:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A, Berglund M (2012) Risk factors for criminal recidivism - a prospective follow-up study in prisoners with substance abuse. BMC Psychiatry 12:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich D, Alves P, Farrell M, Stover H, Moller L, Mayet S (2012) The effectiveness of opioid maintenance treatment in prison settings: A systematic review. Addiction 107:501–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL; van de Ven JTC; Grant BA (2001) Institutional methadone treatment: Impact of release outcome and institutional behaviour. Ottawa Addict Res Centre, Correct Serv Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SM, O’grady KE, Mitchell SG, Brown BS, Schwartz RP (2011) Predictors of methadone treatment retention from a multi-site study: A survival analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 117:170–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O ‘grady KE (2009) A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: Results at 12 months postrelease. J Subst Abuse Treat 37:277–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, O’Grady KE (2013) Individual patient and program factors related to prison and community treatment completion in prison-initiated methadone maintenance treatment. J Offender Rehabil 52:509–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, O ‘grady K, Fitzgerald TT, Wilson M (2007) A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: Results at 1-month post-release. Drug Alcohol Depend 91:220–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, O ‘grady KE (2008) A study of methadone maintenance for male prisoners: 3-month postrelease outcomes. Crim Justice Behav 35:34–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maradiaga JA, Nahvi S, Cunningham CO, Sanchez J, Fox AD (2016) “I kicked the hard way. I got incarcerated.” Withdrawal from methadone during incarceration and subsequent aversion to medication assisted treatments. J Subst Abuse Treat 49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrall ELC, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, Hobbs MS, Farrell M, Marsden J, Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM (2010) Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction 105:1545–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JM, Griffin OH, Gardner CM (2016) Opiate treatment in the criminal justice system: a review of crimesolutions.gov evidence rated programs. Am J Crim Justice 41:70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mir J, Kastner S, Priebe S, Konrad N, Ströhle A, Mundt AP (2015) Treating substance abuse is not enough: Comorbidities in consecutively admitted female prisoners. Addict Behav 46:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ, Karberg JC (2006). Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report Highlights Drug Use and Dependence, State and Federal Prisoners, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rich JD, Boutwell AE, Shield DC, Key RG, McKenzie M, Clarke JG, Friedmann PD (2005) Attitudes and practices regarding the use of methadone in US State and federal prisons. J Urban Heal New York Acad Med 82:411–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JD, Mckenzie M, Larney S, Wong JB, Tran L, Noska A, Reddy M, Zaller N (2015) Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined US prison and jail: a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 386:350–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewksbury R, Connor DP, Denney AS (2014) Disciplinary infractions behind bars: An exploration of importation and deprivation theories. Crim Justice Rev 39:201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman SE, Rich JD (2015) Addiction treatment within u.s. correctional facilities: Bridging the gap between current practice and evidence-based care. J Addict Dis 34:220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerberg VS, McCrady BS, Owens M, Guerin P (2016) Community-based methadone maintenance in a large detention center is associated with decreases in inmate recidivism. J Subst Abuse Treat 70:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.