Abstract

Purpose:

To compare gastric cancer (GC) patients aged 80 years or older undergoing gastrectomy at two high-volume cancer centers in the United States and China.

Methods:

Patients aged ≥80 years old who underwent R0 resection at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC; in NY, U.S.A.; n=159) and Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (FMUUH; in Fujian, China; n=118) from Jan 2000 to Dec 2013 were included. Demographic, surgical, and pathologic variables were compared. Factors associated with survival were determined via multivariate analysis.

Results:

The number of patients increased annually in the FMUUH cohort but not in the MSKCC cohort. Patients at MSKCC were slightly older (mean 83.7 vs. 82.7), more commonly female (38% vs. 19%), and had higher average BMI (26 vs. 23). Treatment at FMUUH more frequently employed total gastrectomy (59% vs. 20%) and laparoscopic surgery (65% vs. 7%) and less frequently included adjuvant therapy (11% vs. 18%). In addition, FMUUH patients had larger tumors of more advanced T, N, and TNM stage. Morbidity (35% vs. 25%, p=0.08) and 30-day mortality (2.5% vs. 3.3%, p=0.67) were similar between the cohorts. For each TNM stage, there was no significant difference between MSKCC and FMUUH patients in 5-year overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS). TNM stage was the only independent predictor of DSS for both cohorts.

Conclusions:

Patients ≥80 years old selected for gastrectomy for GC at MSKCC and FMUUH have acceptable morbidity and mortality, and DSS is primarily dependent on TNM stage.

Keywords: Gastric adenocarcinoma, Elderly, Gastrectomy, Outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common malignancy worldwide, with nearly one million new cases every year.1 The global distribution of gastric cancer varies across regions, with the highest disease burden in East Asia. The disease continues to carry a poor prognosis, accounting for over 700,000 deaths per year.1,2 Gastric cancer most frequently develops at about 60–65 years old. Because life expectancy in the U.S. has now reached 80 years and in China more than 75 years,3,4 and the proportion of elderly in both populations is predicted to grow, the incidence of gastric cancer will likely increase.

Previous studies on elderly gastric cancer patients defined elderly patients as 70 years or older.5,6 According to an analysis of the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, these patients accounted for nearly 30% of gastric cancer patients in the period 2004–2010.7 Patients aged 70 or older make up a similar proportion of gastric cancer patients in China.8 However, few reports have described outcomes following surgery in gastric cancer patients aged ≥ 80 years. In addition, there is controversy regarding whether treatment strategies for elderly patients with gastric cancer should differ from those for younger patients.

Recently, several studies have compared gastric cancer patients in the East and West,9–11 but none focused on elderly patients. Little is known about how tumor features, therapeutic strategies, and prognosis for these patients compare between Eastern and Western countries. In this study, we analyzed data from two institutions (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center [MSKCC] in the U.S. and Fujian Medical University Union Hospital [FMUUH] in China) on patients age ≥ 80 years with gastric cancer who underwent R0 resection.

METHODS

Patient Selection

We queried prospectively maintained gastric cancer databases at MSKCC and FMUUH for patients who underwent curative-intent resection between 2000 and 2013. The inclusion criteria were defined as: (1) age ≥80 years; (2) histologically confirmed primary gastric adenocarcinoma; (3) no distant metastasis; (4) radical gastrectomy with R0 resection and regional lymphadenectomy. In MSKCC cohort, there were 5 patients with R1 resection and 2 patients with R2 resection who were excluded, and the R0 resection rate was 95.8%. In FMUUH cohort, there were 3 patients with R1 resection and 1 patient with R2 resection who were excluded, and the R0 resection rate was 96.7%. Exclusion criteria were: (1) intraoperative evidence of peritoneal dissemination or distant metastasis; (2) incomplete histopathological or survival data; (3) gastric remnant carcinoma; (4) wedge resection or endoscopic mucosal or submucosal resection. Patients were evaluated for fitness for surgery by the primary surgeon. All patients had preoperative Anesthesia evaluation. There was liberal use of preoperative Cardiology, Geriatrics, and other subspecialty evaluations as needed.12 Institutional review board approval was obtained from MSKCC and FMUUH.

Patient Characteristics

We compared the following patient characteristics between the MSKCC and FMUUH cohorts: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and ethnicity. For the FMUUH cohort, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score,13 and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status14 were available. We also compared treatment characteristics, including type of operation, extent of lymphadenectomy, surgical approach (minimally invasive or open), use of neoadjuvant therapy, post-operative morbidity and mortality, and use of adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation. Pathological characteristics compared between the groups included tumor size, location, differentiation, lymph node retrieval, and stage. Tumor stage was determined according to the 8th edition of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC)/American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification system.15 Follow-up after R0 resection generally consisted of clinic visits, with labs and CT scans repeated every 3–6 months for 2 years and every 6–12 months for years 3–5. Disease status at last follow-up was based on a retrospective review of medical records, review of the Social Security Death Index in the United States, and data from the Department of Gastric Surgery or National Statistical Office in China.

Perioperative chemotherapy for patients with advanced GC generally consisted of a combination of a fluoropyrimidine and a platinum agent.

Endpoints and Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoints of the study were disease-specific survival (DSS) and overall survival (OS), which were calculated at 5 years and stratified according to TNM stage. DSS was defined as time from resection to death from GC recurrence and/or metastasis. OS was defined as time from resection to death from any cause.

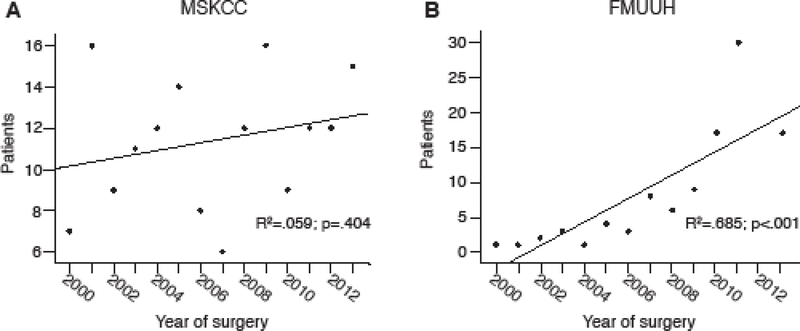

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and medians for discrete. Differences were evaluated using Student’s t test (continuous variables) and the chi-squared test (proportions). Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to assess the relationship between the number of patients older than 80 and year of surgery. DSS and OS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The difference in survival distributions was evaluated by log-rank test, and the relationship between survival and clinical risk factors by Cox regression. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed in SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Treatment Characteristics

A total of 159 MSKCC patients and 118 FMUUH patients that met inclusion criteria were identified, representing 9.8% of the 1,627 patients at MSKCC and 2.9% of the 4,071 at FMUUH undergoing gastrectomy for gastric cancer during the 14-year time period. While there was no time trend in the number of elderly patients treated with surgery at MSKCC (Supplementary Fig.1A), this number increased linearly over time at FMUUH (r=0.685, p<0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Patients at MSKCC were on average older than those at FMUUH (83.7 ± 3.3 versus 82.7 ± 2.8, p=0.006), and FMUUH patients were more frequently male (81.4% versus 61.6%, p<0.001) (Table 1). Mean BMI was higher in patients treated at MSKCC (26.1 ± 3.8 kg/m2 versus 22.5 ± 3.1 kg/m2, p<0.001). All patients treated at FMUUH were Asian, whereas 79.9% of patients treated at MSKCC were Caucasian, 9.4% were black, 8.8% were Asian, and 1.9% were another ethnicity. For FMUUH patients, 73% had an ECOG performance status of 0–1 and 27% had an ECOG performance status of 2–3. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) for these patients was 0 for 42%, 1–2 for 38%, and ≥3 for 20%. We did not have ECOG and CCI data on MSKCC patients.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic and treatment characteristics between MSKCC and FMUUH patients aged ≥80 years undergoing R0 gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

| MSKCC (n=159) n (%) |

FMUUH (n=118) n (%) |

t/χ2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 83.7 ± 3.3 | 82.7 ± 2.8 | 2.794 | 0.006 |

| Sex | 12.552 | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 98 (61.6) | 96 (81.4) | ||

| Female | 61 (38.4) | 22 (18.6) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 26.1 ± 3.8 | 22.5 ± 3.1 | 8.440 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | 222.575 | <0.001 | ||

| White | 127 (79.9) | 0 | ||

| Asian | 14 (8.8) | 0 | ||

| Black | 15 (9.4) | 118 (100.0) | ||

| Other/unknown | 3 (1.9) | 0 | ||

| Type of surgery | 47.884 | <0.001 | ||

| Distal gastrectomy | 104 (65.4) | 45 (38.1) | ||

| Total gastrectomy | 32 (20.1) | 70 (59.3) | ||

| Proximal gastrectomy | 23 (14.5) | 3 (2.5) | ||

| Lymphadenectomy | 0.508 | 0.476 | ||

| <D2 | 27 (17.0) | 24 (20.3) | ||

| D2 | 132 (83.0) | 94 (79.7) | ||

| Surgical approach | 106.338 | <0.001 | ||

| Open | 148 (93.1) | 41 (34.7) | ||

| Minimally invasive | 11 (6.9) | 77 (65.3) | ||

| Perioperative therapy | 11.492 | 0.042 | ||

| Preoperative chemo | 9 (5.7) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Preoperative CRT | 4 (2.5) | 0 | ||

| Postoperative chemo | 9 (5.7) | 11 (9.4) | ||

| Postoperative CRT | 3 (1.9) | 0 | ||

| Pre- and post-operative chemo | 4 (2.5) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| None | 130 (81.7) | 105 (89.0) | ||

Mean ± standard deviation.

Abbreviations: MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; FMUUH, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital; chemo, chemotherapy; CRT, chemoradiotherapy.

Patients treated at MSKCC were more likely to undergo distal gastrectomy than patients treated at FMUUH (65.4% vs. 38.1%, p<0.001) (Table 1). A higher proportion of FMUUH patients underwent minimally invasive surgery (65.3% vs. 6.9%, p<0.001), and a lower proportion received neoadjuvant therapy compared with MSKCC patients (1.6% vs. 10.7%, p<0.05). A similar proportion of patients received postoperative adjuvant therapy at each of the two centers (10.1% and 10.2%, p>0.05).

Pathologic Characteristics

Among patients at FMUUH, tumors were larger (5.4 ± 2.8 cm vs. 4.3 ± 2.9 cm, p=0.004) and more frequently located in the upper third of the stomach (29.7% vs. 24.5%) and encompassed more than two parts of the stomach (16.9% vs. 1.9%), whereas patients at MSKCC more often had distal tumors (46.5% vs. 38.1%, overall p<0.001) (Table 2). Undifferentiated tumors were found in a higher proportion of patients at MSKCC than at FMUUH patients (82.4% vs. 68.6%, p=0.007). Despite the fact that both centers performed a similar extent of lymphadenectomy, fewer lymph nodes were examined in MSKCC patients (median: 20 ± 14.3 vs. 25 ± 12.9, p<0.001). Patients at FMUUH had a greater number of positive LNs (6.9 ± 9.5 vs. 2.2 ± 4.9, p<0.001) and were more likely to have a ratio of positive to retrieved LNs >10% (55.1% vs. 26.4%, p<0.001), and their cancer was of significantly more advanced T stage, N stage, and TNM stage (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of pathologic characteristics between MSKCC and FMUUH patients aged ≥80 years undergoing R0 gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

| MSKCC (n=159) n (%) |

FMUUH (n=118) n (%) |

t/χ2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size (cm)a | 4.3 ± 2.9 | 5.4 ± 2.8 | −3.063 | 0.004 |

| Tumor location | 24.564 | <0.001 | ||

| Upper third | 39 (24.5) | 35 (29.7) | ||

| Middle third | 43 (27.0) | 18 (15.3) | ||

| Lower third | 74 (46.5) | 45 (38.1) | ||

| More than two parts | 3 (1.9) | 20 (16.9) | ||

| Differentiation | 9.861 | 0.007 | ||

| Differentiated | 26 (16.4) | 37 (31.4) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 131 (82.4) | 81 (68.6) | ||

| N/A or unknown | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0) | ||

| No. of LN examinedb | 20 ± 14.3 | 25 ± 12.9 | 3.615 | <0.001 |

| No. of LN examined | 7.962 | 0.019 | ||

| 0–14 | 39 (24.5) | 16 (13.6) | ||

| 15–30 | 90 (56.6) | 66 (55.9) | ||

| >30 | 30 (18.9) | 56 (30.5) | ||

| No. of positive LNa | 2.2 ± 4.9 | 6.9 ± 9.5 | −5.319 | <0.001 |

| Ratio of positive LN | 27.153 | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 90 (56.6) | 40 (33.9) | ||

| ≤10% | 27 (17.0) | 13 (11.0) | ||

| 10–25% | 20(12.6) | 19 (16.1) | ||

| >25% | 22 (13.8) | 46 (39.0) | ||

| T status | 36.080 | <0.001 | ||

| T1 | 55 (34.6) | 11 (9.3) | ||

| T2 | 21 (13.2) | 13 (11.0) | ||

| T3 | 50 (31.4) | 35 (29.7) | ||

| T4a | 30 (18.9) | 55 (46.6) | ||

| T4b | 3 (1.9) | 4 (3.4) | ||

| N status | 32.626 | <0.001 | ||

| N0 | 90 (56.6) | 40 (33.9) | ||

| N1 | 30 (18.9) | 14 (11.9) | ||

| N2 | 23 (14.5) | 22 (18.6) | ||

| N3a | 12 (7.5) | 24 (20.3) | ||

| N3b | 4 (2.5) | 18 (15.3) | ||

| AJCC stage | 25.309 | <0.001 | ||

| I | 67 (42.1) | 18 (15.3) | ||

| II | 41 (25.8) | 34 (28.8) | ||

| III | 51 (32.1) | 66 (55.9) | ||

Mean ± standard deviation;

Median ± standard deviation; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; FMUUH, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital; LN, lymph nodes

Postoperative Morbidity and Mortality

One or more complications occurred in 56 patients (35.2%) in the MSKCC cohort and 30 patients (25.4%) in the FMUUH cohort (p=0.081) (Table 3). There were no significant differences in local or systemic complications (p>0.05). Complication rates in patients aged 85 years or older were not significantly different from rates in patients aged 80–84 (39.6% vs. 33.3% at MSKCC; 32.0% vs. 23.7% at FMUUH; p>0.05). There were 4 patients in each cohort who died within 30 days following surgery (2.5% at MSKCC vs. 3.4% at FMUUH, p=0.668). Nine patients (5.7%) in MSKCC cohort and 7 patients (5.9%) in FMUUH cohort died within 90 days following surgery (p=0.924).

Table 3.

Comparison of morbidity and mortality between MSKCC and FMUUH patients aged ≥80 years undergoing R0 gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

| MSKCC (n=159) n (%) |

FMUUH (n=118) n (%) |

t/χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any complication | 56 (35.2) | 30 (25.4) | 3.036 | 0.081 |

| Age 80–85 | 37/111 (33.3) | 22/93 (23.7) | 2.305 | 0.129 |

| Age >85 | 19/48 (39.6) | 8/25 (32.0) | 0.406 | 0.524 |

| Local complication | 29 (18.2) | 12 (10.2) | 3.497 | 0.061 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 7 | 4 | ||

| Anastomotic stricture | 1 | 0 | ||

| Anastomotic bleeding | 1 | 1 | ||

| Delayed gastric emptying | 4 | 1 | ||

| Fascial dehiscence | 2 | 0 | ||

| Hemorrhage | 1 | 0 | ||

| Ileus, paralytic | 3 | 1 | ||

| Intra-abdominal infection | 5 | 4 | ||

| Small bowel obstruction | 2 | 0 | ||

| Wound infection | 3 | 1 | ||

| Systemic complication | 27 (17.0) | 18 (15.2) | 0.148 | 0.700 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 7 | 2 | ||

| DIC | 0 | 1 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 2 | 1 | ||

| Pneumonitis | 10 | 12 | ||

| Pulmonary embolus | 2 | 0 | ||

| Sepsis | 1 | 1 | ||

| Urinary system | 5 | 1 | ||

| Re-operation | 7 (12.5) | 1 (3.3) | 1.946 | 0.163 |

| 30-day mortality | 4 (2.5) | 4 (3.4) | 0.185 | 0.668 |

| 90-day mortality | 9 (5.7) | 7 (5.9) | 0.009 | 0.924 |

MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; FMUUH, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation

Survival Outcomes

At a median follow-up of 38.6 months (range 1–148) for MSKCC patients and 33.0 months (range 1–105) for FMUUH patients, the 5-year OS and 5-year DSS for MSKCC patients were 44.1% and 58.3%, respectively, and for FMUUH patients were 35.8% and 42.6% (Fig. 1). Although the OS curves were not significantly different, MSKCC patients had better DSS than patients at FMUUH (p<0.05, Fig. 1A). However, stage-specific OS and DSS did not differ between the institutions (OS: stage I, 71.3% vs. 71.4%; stage II, 42.6% vs. 38.3%; stage III, 15.4% vs. 24.9%; all p>0.05. DSS: stage I, 89.7% vs. 83.3%; stage II, 53.5% vs. 51.3%; stage III, 18.0% vs. 29.1%; all p>0.05) (Fig. 1B-D).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) of MSKCC and FMUUH patients for all stages (A), stage I (B), stage II (C), and stage III (D).

Prognostic Factors for Survival

Univariate analysis of DSS in patients at MSKCC identified age, tumor size, tumor location, differentiation type, T status, N status, and TNM stage as significantly associated with DSS. In the FMUUH cohort, surgical approach, tumor size, and T, N, and TNM stage were associated with DSS (Table 4). After multivariate analysis, advanced TNM stage was the only independent predictor of DSS in both cohorts.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors influencing disease-specific survival of patients aged ≥80 years undergoing R0 gastrectomy for gastric cancer at MSKCC and FMUUH

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients |

5-y DSS (%) |

p-value | Hazard ratio |

95% CI | p-value | |

| MSKCC cohort | ||||||

| Age | 0.033 | 0.086 | ||||

| < 85 | 111 | 65.0 | Ref | |||

| ≥ 85 | 48 | 43.2 | 1.735 | 0.925–3.257 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | <0.001 | |||||

| ≤ 4.3 | 93 | 72.2 | Ref | |||

| > 4.3 | 66 | 39.2 | 0.737 | 0.361–1.504 | 0.403 | |

| Tumor location | 0.049 | 0.077 | ||||

| Upper third | 39 | 42.8 | Ref | |||

| Middle third | 43 | 61.3 | 0.446 | 0.211–0.944 | 0.035 | |

| Lower third | 74 | 65.4 | 0.584 | 0.309–1.105 | 0.098 | |

| More than two | 3 | |||||

| Differentiation type | 0.007 | 0.089 | ||||

| Differentiated | 26 | 24.0 | Ref | |||

| Undifferentiated | 131 | 65.3 | 0.633 | 0.285–1.096 | ||

| N/A or unknown | 2 | |||||

| AJCC stage | <0.001 | |||||

| I | 67 | 89.7 | Ref | <0.001 | ||

| II | 41 | 53.5 | 5.677 | 1.964–16.408 | 0.001 | |

| III | 51 | 18.0 | 18.153 | 5.996–54.956 | <0.001 | |

| FMUUH cohort | ||||||

| Surgical approach | 0.028 | |||||

| Open | 41 | 29.2 | Ref | |||

| Minimally invasive | 77 | 48.8 | 0.0.715 | 0.429–1.192 | 0.199 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.001 | |||||

| ≤ 5.0 | 66 | 54.3 | Ref | |||

| > 5.0 | 52 | 28.3 | 1.643 | 0.940–2.872 | 0.082 | |

| AJCC stage | <0.001 | |||||

| I | 18 | 83.3 | Ref | 0.034 | ||

| II | 34 | 51.3 | 3.013 | 0.874–10.378 | 0.081 | |

| III | 66 | 29.1 | 4.637 | 1.371–15.680 | 0.091 | |

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer

Among the MSKCC patients, 77 of 159 died during the study period, 48 (30.2%) of disease and 29 (18.2%) of other causes (Supplementary Table 1). At FMUUH, 74 of the 118 patients died during the study period, 63 (53.4%) of disease and 11 (9.3%) of other causes. This suggests that prognostic factors related to survival in elderly populations should be analyzed using DSS rather than OS. Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 show univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors associated with OS.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that outcomes are similar for patients aged 80 years or older following gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma at high-volume U.S. and Chinese cancer centers when stratified by stage. In addition, morbidity (25–35%) and mortality (2.5–3.4%) at both institutions were reasonable, and AJCC tumor stage was the most significant independent predictor of survival.

Elderly cancer patients have decreased functional reserves and are thus more likely to experience morbidity than younger patients.16–18 However, two Korean studies have found similar morbidity and mortality between elderly (defined as ≥ 70 or ≥ 75 years) and younger patients with gastric cancer.19,20 Although 30-day mortality in the current study (2.5%−3.4%) was slightly higher than that in previous reports on patients of all ages (2% at MSKCC10 and 0.4% at FMUUH21) and a multi-institutional study in Japan,22 it was similar to that reported by some European institutions (2.1%−5.5%).23–25 Moreover, the 90-day mortality rate in this study was also similar or less than the previously studies (5.8–13.7%).26–28 Thus, we conclude that the postoperative mortality of surgery is acceptable in elderly patients whose disease has not metastasized and who are healthy enough to undergo operation with acceptable postoperative mortality.

Previous comparisons of gastric cancer outcomes between Asian countries and the U.S. have found that survival is better among patients treated in Korea and Japan,9,29 but not in China.30 Indeed, in the present study Chinese patients had more advanced cancer and more LN metastases than U.S. patients. Screening for gastric cancer by upper GI endoscopy is not widespread in China, and Chinese patients with cancer, especially those in rural areas, are often reluctant to seek treatment.31 Another potential reason for the greater survival of gastric cancer patients in Korea and Japan is the lower frequency of cancers affecting the upper third of the stomach,9,29 which are associated with worse outcomes.32 In contrast, we observed similar proportions of gastric cancer patients with tumors affecting the upper third between institutions in the U.S. and China, confirming the previous report.30 Moreover, there were similar non-curative resection (R1/R2) rates between MSKCC and FMUUH cohorts (4.2% vs 3.3%), which were slightly lower than that in previous report on patients of all ages (9.7% in MSKCC),33 which may partly contribute by more carefully selection of early clinical stages for elderly patients to surgery.

In this study, significant differences in tumor characteristics and treatment were observed between the cohorts. Patients at MSKCC were older on average, included a higher proportion of women, and had a higher average BMI, consistent with previous studies comparing gastric cancer in Eastern and Western populations. In addition, there were only 2 patients (1.7%) at FMUUH that received preoperative chemotherapy, which is significantly fewer than at MSKCC (10.7%), consistent with differing standards of practice between the U.S. and China.10

Though elderly patients generally have more comorbidities and worse health status than younger patients, their DSS and prognostic factors following gastrectomy for gastric cancer appear similar. Previous comparisons of elderly and nonelderly gastric cancer patients found similar DSS between the two groups,34 with no effect of age on survival.35 The 5-year DSS rate that we observed for the MSKCC cohort, 58.3%, is similar to previous reports on gastric cancer patients of all ages.10,30 Similarly, the 5-year DSS rates for each stage were similar to those in a recent evaluation of the 7th edition revisions to AJCC staging.36 These comparable DSS rates were observed in spite of much less frequent use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy than that for younger patients. Although there was significantly better DSS in the MSKCC cohort compared to the FMUUH cohort, there was no significant difference between cohorts with the same stage cancers, and TNM stage was the only independent predictor of DSS in both cohorts. Since a relatively high proportion of the elderly patients die of other causes within a 5-year interval of their major gastric surgery, the OS could be used as a complementary and important outcome measure for elderly gastric cancer patients. In the current study, the OS was also not significant different between the two cohorts when stratified by stage.

The benefit of surgery in elderly patients with late-stage gastric cancer is controversial. In the current study, the proportion of patient deaths due to other diseases was higher among early-stage patients (Supplemental Table 1), as the majority of these patients are cured by surgery. However, for patients with later stage disease, 5-year DSS is much lower, around 20% for stage III in our study. A recent investigation found that surgery provided benefit to patients aged 85–89 years, but not patients aged 90 years or older.37 However, age may not be the key factor; an editorial on that study suggested that comorbidities were the key reason for differing outcomes, and that chronological age alone is not sufficient reason to withhold surgical treatment.38

There are several limitations to this study. First, its retrospective and non-randomized nature makes it subject to selection bias. We were not able to compare all patients at least 80 years old who had operable gastric cancer, because their data could not be reliably obtained from our institutions’ databases. There were certainly patients who did not undergo surgical resection despite having resectable disease because they were medically unfit. Second, there were some discrepancies between the two institutions’ databases, which may confound the differences in demographic and tumor characteristics between the cohorts. Third, this study is limited by a relatively small sample size. Fourth, we do not have additional data on quality of life, nutritional status, immune function, medication absorption status, and other measures which could be major considerations when evaluating these elderly patients for radical resection. Despite these limitations, this study provides insight into the outcomes of patients aged 80 years or older following radical gastrectomy and could be used as a basis for the future prospective studies. Our findings suggest that aggressive surgical treatment may be effective in these elderly patients.

In conclusion, we found several differences in demographics, treatment standards, and pathological findings between patients aged 80 years and older undergoing surgical resection for gastric cancer at a high-volume cancer center in the U.S. and those treated at a similar institution in China. However, stage-specific 5-year OS and DSS did not differ significantly between the two cohorts, and tumor stage was the only independent risk factor for DSS. When relevant selection guidelines are followed, surgery can be performed in these patients with acceptable morbidity and mortality.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis: We compared gastric cancer (GC) patients aged 80 years or older undergoing gastrectomy at two high-volume cancer centers in the United States and China. Despite differences in clinicopathologic characteristics, outcomes were similar between the two cohorts when stratified by stage.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded in part by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748, the Scientific and Technological Innovation Joint Capital Projects of Fujian Province, China (No.2016Y9031), and the Construction Project of Fujian Province Minimally Invasive Medical Center (No. [2017] 171). We also thank Jessica Moore, senior editor in the Department of Surgery, MSKCC, for editing.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no commercial interests related to this research.

Ethical Standards: This research was approved by the Ethics Committees of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Fujian Medical University Union Hospital. All procedures were in accordance with institutional and national ethical standards on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. March 2015;65(2):87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sitarz R, Skierucha M, Mielko J, Offerhaus GJA, Maciejewski R, Polkowski WP. Gastric cancer: epidemiology, prevention, classification, and treatment. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:239–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Day SM, Reynolds RJ, Kush SJ. The relationship of life expectancy to the development and valuation of life care plans. NeuroRehabilitation. 2015;36(3):253–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Y, Ren J, Shen J, Li T, Zhang CF. The changing gender differences in life expectancy in Chinese cities 2005–2010. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mochiki E, Ohno T, Kamiyama Y, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in young and elderly patients. World J Surg. Dec 2005;29(12):1585–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasuda K, Sonoda K, Shiroshita H, Inomata M, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in the elderly. Br J Surg. Aug 2004;91(8):1061–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song P, Wu L, Jiang B, Liu Z, Cao K, Guan W. Age-specific effects on the prognosis after surgery for gastric cancer: A SEER population-based analysis. Oncotarget. Jul 26 2016;7(30):48614–48624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang YX, Deng JY, Guo HH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of gastric cancer in patients aged >/= 70 years. World J Gastroenterol. October 21 2013;19(39):6568–6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shim JH, Song KY, Jeon HM, et al. Is Gastric Cancer Different in Korea and the United States? Impact of Tumor Location on Prognosis. Annals of Surgical Oncology. July 2014;21(7):2332–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strong VE, Song KY, Park CH, et al. Comparison of Gastric Cancer Survival Following R0 Resection in the United States and Korea Using an Internationally Validated Nomogram. Annals of Surgery. April 2010;251(4):640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlemper RJ, Itabashi M, Kato Y, et al. Differences in diagnostic criteria for gastric carcinoma between Japanese and Western pathologists. Lancet. June 14 1997;349(9067):1725–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daabiss M American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2011;55(2):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. December 1982;5(6):649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amin MBES, Greene FL, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korc-Grodzicki B, Downey RJ, Shahrokni A, Kingham TP, Patel SG, Audisio RA. Surgical Considerations in Older Adults With Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. August 20 2014;32(24):2647–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coniglio A, Tiberio GAM, Busti M, et al. Surgical treatment for gastric carcinoma in the elderly. Journal of Surgical Oncology. December 15 2004;88(4):201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu J, Huang CM, Zheng CH, et al. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes After Laparoscopic Versus Open Total Gastrectomy for Elderly Gastric Cancer Patients: a Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. November 2015;19(11):1949–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong O, Park YK, Ryu SY, Kim YJ. Effect of age on surgical outcomes of extended gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection in gastric carcinoma: prospective cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. June 2010;17(6):1589–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shim JH, Ko KJ, Yoo HM, et al. Morbidity and mortality after non-curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer in elderly patients. Journal of Surgical Oncology. November 2012;106(6):753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin JX, Huang CM, Zheng CH, et al. Evaluation of laparoscopic total gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: results of a comparison with laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. May 2016;30(5):1988–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etoh T, Honda M, Kumamaru H, et al. Morbidity and mortality from a propensity score-matched, prospective cohort study of laparoscopic versus open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: data from a nationwide web-based database. Surg Endosc. December 7 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, et al. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. February 2005;241(2):232–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pugliese R, Maggioni D, Sansonna F, et al. Total and subtotal laparoscopic gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. January 2007;21(1):21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azagra JS, Ibanez-Aguirre JF, Goergen M, et al. Long-term results of laparoscopic extended surgery in advanced gastric cancer: a series of 101 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. Mar-Apr 2006;53(68):304–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bollschweiler E, Lubke T, Monig SP, Holscher AH. Evaluation of POSSUM scoring system in patients with gastric cancer undergoing D2-gastrectomy. BMC Surg. April 15 2005;5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damhuis RA, Wijnhoven BP, Plaisier PW, Kirkels WJ, Kranse R, van Lanschot JJ. Comparison of 30-day, 90-day and in-hospital postoperative mortality for eight different cancer types. Br J Surg. Aug 2012;99(8):1149–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katai H, Sasako M, Sano T, Maruyama K. The outcome of surgical treatment for gastric carcinoma in the elderly. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28(2):112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noguchi Y, Yoshikawa T, Tsuburaya A, Motohashi H, Karpeh MS, Brennan MF. Is gastric carcinoma different between Japan and the United States? Cancer. December 1 2000;89(11):2237–2246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strong VE, Wu AW, Selby LV, et al. Differences in gastric cancer survival between the U.S. and China. J Surg Oncol. July 2015;112(1):31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zong L, Abe M, Seto Y, Ji J. The challenge of screening for early gastric cancer in China. Lancet. November 26 2016;388(10060):2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pacelli F, Papa V, Caprino P, Sgadari A, Bossola M, Doglietto GB. Proximal compared with distal gastric cancer: multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Am Surg. July 2001;67(7):697–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt B, Chang KK, Maduekwe UN, et al. D2 lymphadenectomy with surgical ex vivo dissection into node stations for gastric adenocarcinoma can be performed safely in Western patients and ensures optimal staging. Annals of surgical oncology. 2013;20(9):2991–2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohri Y, Yasuda H, Ohi M, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic gastrectomy in elderly patients with gastric cancer. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. June 2015;29(6):1627–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orsenigo E, Tomajer V, Palo SD, et al. Impact of age on postoperative outcomes in 1118 gastric cancer patients undergoing surgical treatment. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10(1):39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dikken JL, van de Velde CJ, Gonen M, Verheij M, Brennan MF, Coit DG. The New American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer staging system for adenocarcinoma of the stomach: increased complexity without clear improvement in predictive accuracy. Ann Surg Oncol. August 2012;19(8):2443–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endo S, Dousei T, Yoshikawa Y, Hatanaka N, Kamiike W, Nishijima J. Prognosis of gastric carcinoma patients aged 85 years or older who underwent surgery or who received best supportive care only. International Journal of Clinical Oncology. December 2013;18(6):1014–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nashimoto A Current status of treatment strategy for elderly patients with gastric cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. December 2013;18(6):969–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.