Abstract

Cancer growth and progression are associated with immune suppression. Cancer cells have the ability to activate different immune checkpoint pathways that harbor immunosuppressive functions. Monoclonal antibodies that target immune checkpoints provided an immense breakthrough in cancer therapeutics. Among the immune checkpoint inhibitors, PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors showed promising therapeutic outcomes, and some have been approved for certain cancer treatments, while others are under clinical trials. Recent reports have shown that patients with various malignancies benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. However, mainstream initiation of immune checkpoint therapy to treat cancers is obstructed by the low response rate and immune-related adverse events in some cancer patients. This has given rise to the need for developing sets of biomarkers that predict the response to immune checkpoint blockade and immune-related adverse events. In this review, we discuss different predictive biomarkers for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 inhibitors, including immune cells, PD-L1 overexpression, neoantigens, and genetic and epigenetic signatures. Potential approaches for further developing highly reliable predictive biomarkers should facilitate patient selection for and decision-making related to immune checkpoint inhibitor-based therapies.

Cancer immunotherapy: Markers of success

Biomarkers that predict a patient’s response to cancer immunotherapy are being developed, and may allow individual tailoring of therapies. Cancer cells can suppress the immune system by activating immune checkpoints, signals that stop the immune system from attacking the host. Immunotherapy, a recently developed treatment, inactivates immune checkpoints, restoring the patient’s immune response against the tumor. Although promising, immunotherapy has a low response rate, and sometimes triggers severe auto-immune reactions. Eyad Elkord at Qatar Biomedical Research Institute in Qatar and coworkers have reviewed biomarkers that could be used to predict individual effects of immunotherapy, identifying nonresponders and preventing adverse immune reactions. They discuss markers based on factors such as immune response level and individual tumor genetics, among others. With further research and testing, these biomarkers could improve the efficacy of this promising new cancer therapy.

Introduction

The development of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) is a revolutionary milestone in the field of immuno-oncology. Tumor cells evade immunosurveillance and progress through different mechanisms, including activation of immune checkpoint pathways that suppress antitumor immune responses. ICIs reinvigorate antitumor immune responses by interrupting co-inhibitory signaling pathways and promote immune-mediated elimination of tumor cells.

Ipilimumab, which targets cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), was the first approved immune checkpoint inhibitor for treating patients with advanced melanoma1–3. This antibody prevents T-cell inhibition and promotes the activation and proliferation of effector T cells. Following the approval of ipilimumab, other antibodies that target immune checkpoints were examined. Currently, hundreds of phase I and II clinical trials and phase III/IV clinical trials are being carried out across the globe to evaluate the efficacy of multiple ICIs as monotherapy or in combination (details of phase III/IV trials are given in Table 1).

Table 1.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors in phase III and IV clinical trials

| Sl No | Drug | Cancer type | Clinical trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pembrolizumab (Anti-PD-1) | NSCLC | NCT03134456, NCT02220894, NCT02142738, NCT02864394, NCT03302234, NCT01905657, NCT02504372, NCT02775435, NCT02578680 |

| 2 | Small cell lung cancer | NCT03066778 | |

| 3 | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | NCT02252042, NCT03040999, NCT02358031 | |

| 4 | Renal cell carcinoma | NCT03142334, NCT02853331 | |

| 5 | Gastric adenocarcinoma | NCT02370498 | |

| 6 | Nasopharyngeal neoplasms | NCT02611960 | |

| 7 | Urothelial carcinoma | NCT02853305, NCT03244384, NCT02256436, NCT03374488, NCT03361865 | |

| 8 | Colorectal cancer | NCT02563002 | |

| 9 | Pleural mesothelioma | NCT02991482 | |

| 10 | TNBC | NCT02819518, NCT03036488, NCT02555657 | |

| 11 | Esophageal neoplasms | NCT03189719, NCT02564263 | |

| 12 | Multiple myeloma | NCT02579863, NCT02576977 | |

| 13 | Gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer | NCT03019588, NCT03221426 | |

| 14 | Gastric adenocarcinoma | NCT02494583 | |

| 15 | Melanoma | NCT02362594, NCT01866319 | |

| 16 | Hodgkin lymphoma | NCT02684292 | |

| 17 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | NCT02702401, NCT03062358 | |

| 18 | Lung cancer | NCT03322540 | |

| 19 | Head and neck cancer | NCT03358472 | |

| 20 | Nivolumab (Anti-PD-1) | NSCLC | NCT02041533, NCT01642004, NCT01673867 |

| 21 | Mesothelioma | NCT03063450 | |

| 22 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | NCT03366272 | |

| 23 | Metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma | NCT01668784 | |

| 24 | Head and neck cancer | NCT02741570, NCT03342352 | |

| 25 | Lung cancer | NCT03348904 | |

| 26 | Melanoma | NCT03068455, NCT01844505 | |

| 27 | Ipilimumab (Anti-CTLA-4) | NSCLC | NCT03469960, NCT03351361, NCT02785952, NCT03302234 |

| 28 | Squamous cell lung carcinoma | NCT02785952 | |

| 29 | Mesothelioma | NCT02899299 | |

| 30 | Gastric cancer Gastroesophageal junction cancer |

NCT02872116 | |

| 31 | Metastatic melanoma | NCT03445533, NCT00636168, NCT01274338, NCT02339571, NCT02506153, NCT02224781, NCT00094653 | |

| 32 | Metastatic non-cutaneous melanoma | NCT02506153 | |

| 33 | Avelumab (Anti-PD-L1) | NSCLC | NCT02576574, NCT02395172 |

| 35 | Urothelial cancer | NCT02603432 | |

| 35 | Diffuse Large B-cell lymphoma | NCT02951156 | |

| 36 | Renal cell cancer | NCT02684006 | |

| 37 | Gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer | NCT02625623, NCT02625610 | |

| 40 | Atezolizumab (Anti-PD-L1) | Ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer Peritoneal neoplasms |

NCT03038100, NCT02839707, NCT02891824 |

| 41 | NSCLC | NCT02813785, NCT02008227, NCT02367781, NCT02366143, NCT02409342, NCT02486718, NCT02367794, NCT03191786, NCT02409355, NCT02657434, NCT03456063 | |

| 42 | Extensive stage small cell lung cancer | NCT02763579 | |

| 43 | TNBC | NCT03197935, NCT02425891, NCT03125902, NCT03281954 | |

| 44 | Renal cell carcinoma | NCT02420821, NCT03024996 | |

| 45 | Bladder cancer | NCT02302807 | |

| 46 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck | NCT03452137 | |

| 47 | Urothelial carcinoma | NCT02807636 | |

| 48 | Transitional cell carcinoma | NCT02450331 | |

| 49 | Prostatic neoplasms | NCT03016312 | |

| 50 | Durvalumab (Anti-PD-L1) | NSCLC | NCT02352948, NCT03003962, NCT02453282, NCT02273375, NCT02542293, NCT03164616, NCT02125461, |

| 51 | Squamous cell lung carcinoma | NCT02154490, NCT02551159 | |

| 52 | Recurrent or metastatic PD-L1 positive or negative SCCHN | NCT02369874 | |

| 53 | Recurrent squamous cell lung caner | NCT02766335, NCT02154490 | |

| 54 | Urothelial cancer | NCT02516241 | |

| 55 | Advanced solid malignancies | NCT03084471 | |

| 56 | SCCHN, hypo pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma | NCT02551159, NCT03258554 | |

| 57 | REGN2810 (Anti-PD-1) | NSCLC | NCT03409614, NCT03088540 |

| 58 | BMS-936558 (Anti-PD-1) | Unresectable or metastatic melanoma | NCT01721746, NCT01721772 |

| 59 | SHR1210 (Anti-PD-1) | NSCLC | NCT03134872 |

| 60 | Nasopharyngeal neoplasms | NCT03427827 | |

| 61 | KN035 (Anti-PD-L1) | Biliary tract neoplasms | NCT03478488 |

| 62 | IBI308 (Anti-PD-1) | Squamous cell lung carcinoma | NCT03150875 |

| 63 | PDR001 (Anti-PD-1) | Melanoma | NCT02967692 |

| 64 | Anti-PD-1 | Metastatic melanoma | NCT02821013 |

| 65 | BGB-A317 (Anti-PD-1) | NSCLC | NCT03358875 |

| 66 | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | NCT03430843 | |

| 67 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | NCT03412773 | |

| 68 | BCD-100 (Anti-PD-1) | NSCLC | NCT03288870 |

| 70 | JS001 (Anti-PD-1) | Metastatic melanoma | NCT03430297 |

Pembrolizumab and nivolumab, ICIs that target programmed death-1 (PD-1), showed promising results in melanoma and non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) patients, with an objective response rate (ORR) of 40–45%4–6. Additionally, urothelial bladder cancer patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors showed an increase in overall response rate, between 13 and 24%7. In triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients, the response to PD-1 inhibitors was relatively moderate (19%)8. In contrast, in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma, nivolumab showed an objective response rate of 87% with 17% complete response9. Pembrolizumab and nivolumab are currently under phase IV clinical trials for treating various malignancies (Table 1).

Despite the success of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies, only a fraction of patients benefit from ICIs. Antitumor immunity, regulated through complex factors in the tumor microenvironment (TME), could create variable immune responses. The TME is segregated into three major types based on the infiltration of immune cells: immune desert, immune excluded and immune inflamed10. These phenotypes have their own mechanisms for preventing immune responses from eradicating tumor cells10. Immune deserts are characterized by the absence of T cells in the TME and the lack of suitable T cell priming or activation. The immune excluded phenotype exhibits the presence of multiple chemokines, vascular factors or mediators and stromal-based inhibition; however, accumulated T cells are unable to infiltrate the TME. Immune inflamed tumors demonstrate infiltration of multiple immune cell subtypes10.

Accumulating evidence suggests that only a fraction of cancer patients benefit from checkpoint inhibitors, and severe immune-related adverse events (irAEs) are seen in some patients undergoing ICI therapy11. irAEs are due to the inhibition of immune checkpoints that reinforce the normal physiological barriers against autoimmunity, leading to various local and systemic autoimmune responses. Therefore, the development of predictive biomarkers is critical for differentiating responders and nonresponders to avoid any adverse effects. Ongoing clinical studies are aiming to develop predictive biomarkers for better treatment outcomes and less irAEs.

Predictive biomarkers could determine the outcome of therapy in a patient before the initiation of a proposed therapy. These biomarkers should indicate whether a patient would benefit from a particular checkpoint monotherapy or if there is a need for combination therapy. In this review, we discuss biomarkers that predict the response to various ICI therapies in cancer.

Immune cells

Immune inflamed tumors have a high degree of response to immunotherapy. Reports suggest that immune inflamed tissues are more sensitive because ICIs can activate immune reactions and inhibit immune evasion/suppression. Studies confirmed that the response to ICI therapy is related to tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and other immune cells in the TME12.

Analyses of peripheral blood is a noninvasive method with good potential to predict treatment outcomes after immune therapies. Reports have shown that in various malignancies, increased tumor-infiltrating immune cells and peripheral blood absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) can be utilized as predictive biomarkers13–15. The role of ALC as a predictive biomarker has been validated in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Patients with 1.35-fold higher ALC values from baseline in the first 2 weeks of treatment had significantly higher overall survival16. In ipilimumab-treated patients, overall progression-free survival was associated with a low serum lactate dehydrogenase value (LDH ≤ 1.2-fold), a low absolute monocyte count (AMC < 650 cells/µL), a low myeloid-derived suppressor cell count (MDSCs < 5.1%), a high absolute eosinophil count (eosinophils ≥ 50 cells/µL), a relative lymphocyte count < 10.5% and baseline CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs ≥ 1.5% in the peripheral blood15,17. Multiple studies validating the applicability of LDH as a predictive biomarker showed that patients with elevated levels of LDH also responded to ICIs18. Studies have reported that LDH can be used as a potential predictive biomarker for overall survival but not as a prognostic biomarker15,16,19. CyTOF-based immune profiling of peripheral blood samples collected from anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1-treated melanoma patients showed a distinct set of biomarkers in response to therapy20. This study suggested that the abundance of CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells was a predictive biomarker for anti-CTLA-4 therapy and the abundance of CD69+ and MIP1β+ NK cells was a predictive biomarker for anti-PD-1 therapy20. CyTOF analyses of anti-PD-1-treated melanoma patients showed an involvement of CD14+CD16−HLA-DRhi cells in therapy response and progression-free survival (PFS)21. An increase in circulating CD4+, CD8+ T cells and ALC, 2 to 8 weeks after treatment initiation with ipilimumab, was reported in melanoma patients with better clinical outcomes22. Apart from the circulating CD8+ T cells, CD8+ effector memory type-1 T cells were also reported as predictive biomarkers for ipilimumab-treated stage IV melanoma patients23,24.

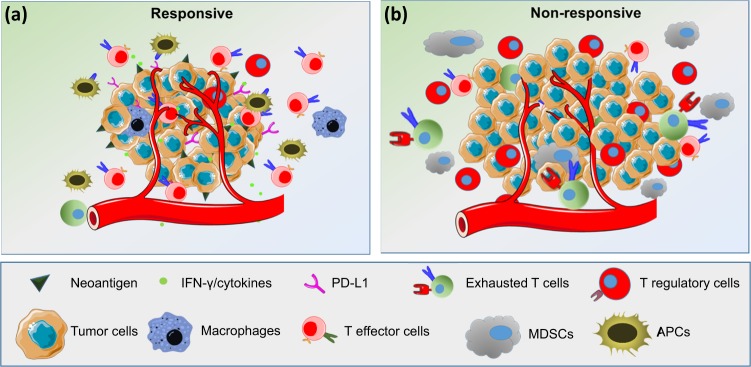

The presence of TILs in various malignancies can be used as potent predictive biomarkers for response to ICIs13,14. Tumors with increased TILs are a major hallmark of the immune inflamed phenotype, and they exhibit improved immune-mediated elimination of tumor cells. In ipilimumab-treated melanoma patients, TILs were significantly increased from baseline in a therapy-responsive group, confirming their significance in response to ICIs25. To explain the role of immune cells in the treatment response, a study was carried out using 52 lymph nodes and 34 cutaneous/subcutaneous metastatic surgical samples collected from 30 metastatic melanoma patients receiving ipilimumab26. In this study, Balatoni et al.26 examined 11 immune cell subsets in the TME and their post-therapy responses. Interestingly, 7 out of 11 immune subsets positively correlated with an increase in the overall survival rate. These subsets included CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, cells expressing CD134+ and CD137+ activation markers, FOXP3+ T cells and NKp46+ cells. Notably, subcutaneous and cutaneous metastatic tissues, compared to lymph nodes, showed distinct immune cell infiltration. In subcutaneous and cutaneous samples, the presence of CD16+ and CD68+ cells positively correlated with therapy response as well as prolonged survival. In contrast, in the lymph nodes, CD45RO+, PD-1+, CD16+, and CD68+ cells correlated only with increased survival26. In addition to the abundance of FOXP3+ Tregs, the ratio of effector T cells (Teffs) to Tregs is reported to be a more specific predictive biomarker for anti-CTLA-4 immune therapies27,28. Immune profiling of TILs using multiparametric flow cytometry in metastatic melanoma patients showed that PD-1hiCTLA-4hi in CD8+ T cells predict the response to anti-PD-1 therapy29. This study is supported through the identification of both transcriptionally and functionally distinct CD8+PD-1+ T-cell subpopulations in NSCLC patients, showing predictive potential for anti-PD-1 therapy30. Additionally, intratumoral and peripheral CD4+FOXP3−PD-1hi nonconventional Tregs in NSCLC as well as melanoma patients were reported as prognostic biomarkers for anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapies31. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy induced an immune inflamed phenotype via expansion of intratumoral and systemic CD4+FOXP3−PD-1hi Tregs that were reduced with anti-PD-1 therapy and improved the overall antitumor response31. Moreover, PD-L1+CD4+CD25+ Tregs predict responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in NSCLC patients32. Figure 1 shows an overview of how the presence of various immune cell subsets in the TME may contribute to the differential responses to ICIs in responders and nonresponders.

Fig. 1. Overview of predictive biomarkers for response to ICIs.

The response to immune checkpoint inhibitors varies depending on the TME. In the responders, tumors have a high neoantigen load, high levels of TILs, especially effector cells, a high Teff to Treg ratio, low MDSC levels and increased secretion of IFN-γ and other cytokines (a). In nonresponders, the TME contains high levels of immunosuppressive cells, such as Tregs and MDSCs, and very low levels of NK cells and activated lymphocytes (b)

Pembrolizumab in advanced melanoma patients showed that pre-existing CD8+ T cells in the TME are required for better tumor regression33. The presence of an immune excluded phenotype with an abundance of immune cells at invasive margins or stroma is also associated with clinical benefits. The spatiotemporal dynamics of CD8+ T cells are also an important factor for better treatment outcomes. Analysis of pretreatment samples collected from patients undergoing PD-1/PD-L1 therapy showed a relatively higher abundance of CD8+ T cells at the invasive margins in therapy responders. These pretreatment samples show an immune excluded phenotype through increased accumulation of T cells on the invasive margin without effective infiltration. Moreover, serially sampled tumors during therapy showed an increase in CD8+ T cells at the invasive margin and then in parenchyma in the response group33. This increase in CD8+ T cells may be due to the negative regulation of PD-1/PD-L1 by ICIs, which resulted in either the infiltration of immune cells or the enhanced proliferation of CD8+ T cells33. Additionally, it has been reported that in lung cancer patients, CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration to deep tissues significantly correlated with longer overall survival34. Metastatic breast cancer patients treated with atezolizumab showed an increased ORR related to stromal TILs35. The predictive potentials of stromal TILs were confirmed in the KEYNOTE-086 study; significantly higher levels of stromal TILs were associated with the anti-PD-1 therapy response in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer patients36.

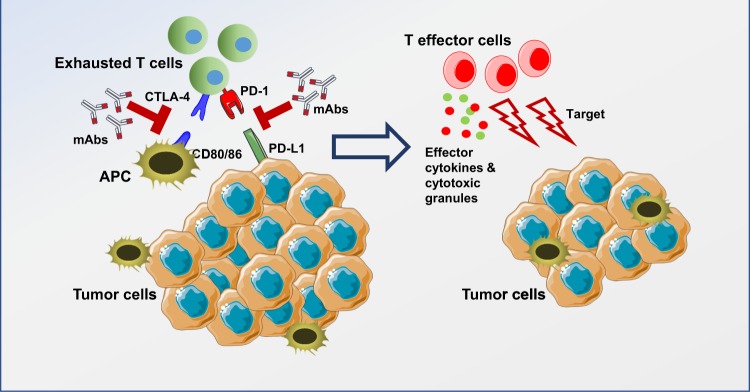

CTLA-4 blockade activates T cells to target malignant cells. CTLA-4 is constitutively expressed in T cells and attenuates immune responses when bound to CD80 or CD86 on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (Fig. 2). Analyses of pre- and post-treated surgical tissues and peripheral blood showed that the inducible costimulator (ICOS) pathway is activated upon anti-CTLA-4 therapy37. This overexpression of ICOS (CD28/CTLA-4 Ig superfamily) resulted in an increase in ICOS+ T cells in both tumor and blood samples37. In tremelimumab-treated breast cancer patients, increased CD4+ICOS+ and CD8+ICOS+ T cells were observed in peripheral blood37. The ratio of FOXP3+ Treg cells to ICOS+ T cells was also increased in therapy-responsive patients37. Moreover, in patients exhibiting clinical benefits, there was an increase in the frequency of CD4+ICOS+Teff cells. These cells express T-bet and produce IFN-γ, strengthening immune responses in anti-CTLA-4 therapy38–40.

Fig. 2. Immune checkpoint blockade for T-cell activation.

Immune checkpoints, including PD-1 and CTLA-4, expressed on activated T cells lead to inhibition of T-cell activation upon binding to their ligands on tumor cells/antigen-presenting cells. These interactions can be blocked using monoclonal antibodies, leading to the activation of T cells targeting tumor cells through the release of effector cytokines and cytotoxic granules.

PD-L1 overexpression

Interactions between PD-1 and its ligands, B7-H1/PD-L1 and B7-DC/PD-L2, lead to T-cell inactivation to maintain immune homeostasis and prevent autoimmunity. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway activation is related to the immune inflamed phenotype41. IC ligands are commonly found on tumor cells, and these interactions work in tandem with elevated tumor infiltration of immunosuppressive cells to support tumor escape from active T-cell responses42. Therefore, blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory pathway can activate T cells in the TME, releasing inflammatory cytokines and cytotoxic granules to eliminate tumor cells (Fig. 2).

The direct approach to check responsiveness to PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in patients is to detect the expression levels of PD-L1 in tumor tissues. Teng et al.43 proposed four different classifications of TME based on the presence of TILs and PD-L1 expression. They classified PD-L1-positive tumors with TILs as a type I tumor microenvironment and proposed it to be most likely to respond to immune checkpoint blockade.

IHC analyses performed on patients with metastatic melanoma, NSCLC, colon cancer, renal cell carcinoma and prostate cancer who underwent PD-1/PD-L1 targeting therapy suggested PD-L1 overexpression as a potential biomarker. An open-label Phase II clinical trial of pembrolizumab in NSCLC reported that progression-free survival and overall survival were higher in patients with PD-L1 expression in at least 50% of tumor cells44. Notably, elevated levels of PD-L1 expression in the TME do not correlate with worse differentiation and poor prognosis. High PD-L1 expression is often accompanied by IFN-γ-secreting TILs in some cancers45. However, Aguiar et al. suggested that PD-L1 overexpression may not be a robust biomarker for the response to ICIs in all cancers, as PD-L1-negative tumors can also respond to mAbs targeting PD-1/PD-L1 interactions. Therefore, to date, PD-L1 overexpression as a prerequisite for initiation of PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade is not established as a potent biomarker for determining responsiveness to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 based immunotherapy.

Investigating PD-L1 expression has some limitations that need to be considered. PD-L1 expression is known to be both spatial and temporal, and it is also expressed on other immune cells, including antigen-presenting cells. One plausible approach to counter these limitations is to perform PD-L1 expression analyses on circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in peripheral blood samples from cancer patients. Interestingly, PD-L1+ CTCs were found to be higher than PD-L1+ cells in the TME of NSCLC patients (83% vs. 41%), and no correlation was observed between tissue and CTC PD-L1 expression46. Therefore, further investigations are warranted to establish PD-L1 expression on CTCs as a predictive biomarker.

Neoantigens

Acquired mutations during cancer progression have promise in detecting efficiency of and resistance to therapy. Mutations in the protein-coding regions of DNA generate truncated proteins termed ‘‘neoantigens.’’ Neoantigens result in a higher degree of foreignness to cells, which helps immune cells readily target and eliminate tumor cells. Various neoantigens that confer therapy efficacy could be potential biomarkers for predicting the clinical activity of ICIs. A retrospective study on stage I/II and stage III/IV lung cancer samples showed that high neoantigen burden is associated with the longest overall survival (P = 0.025)47. Moreover, intratumoral heterogeneity analyses showed that high neoantigen-expressing clones were homogenous with the highest differential expression of PD-L1 and IL-647. Additionally, CD8α and β, STAT1, TAP-1 and 2, CXCL-10, CXCL-9, granzyme–B, –H, and –A, and IFN-γ were upregulated in the high neoantigen-expressing clones47. Overexpression of IFN-γ, IDO, and Th1-associated markers was reported in ipilimumab-treated patients with favorable clinical outcomes. Resistance to CTLA-4 therapy was observed with a loss in IFN-γ signaling in CD8+ T cells. These findings confirm that the immune-mediated elimination of tumor cells could be proportional to the neoantigen load. Neoantigens exhibiting high-affinity binding with MHC and TCR are highly eliminated neoantigens48. Moreover, acquired resistance to ICI can also be predicted through neoantigen landscapes48. Screening of these neoantigens has the potential to predict clinical activity as well as therapeutic resistance.

Tumor tissues from melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab or tremelimumab were used to study the role of somatic mutations as predictive biomarkers for clinical response. Whole genome somatic neoepitope analyses and patient-specific HLA typing were performed in tumors and whole blood samples from 64 patients. It was reported that the neoantigen landscape, as defined through IHC analyses, has a strong association with the treatment response to CTLA-4 blockade49. This study strengthens high-throughput IHC analyses using biopsy specimens to clinically validate therapeutic outcomes.

Recent studies revealed that the evolution of the neoantigen profile in NSCLC patients is associated with the response to ICIs. Acquired resistance to immunotherapy was observed in a cohort of 42 patients with NSCLC who were treated with a PD-1 inhibitor alone or in combination with a CTLA-4 inhibitor48. The whole genome of paired tissues collected before and after therapy was analyzed for the neoantigen landscape related to therapy resistance. This study reported that loss-of-function mutations coding for neoantigens either by the elimination of tumor clones or by chromosomal truncated gene alteration can result in therapy resistance48. Additionally, tumor cells alter the expression of immune suppressive proteins and multiple transcription factors involved in immune functions to acquire resistance against ICIs50. Whole-genome analyses performed on tissues obtained from baseline and relapsed tumors of metastatic melanoma patients undergoing pembrolizumab treatment revealed that acquired resistance to ICIs are associated with loss-of-function mutations51. Truncated mutations in IFN-receptor-associated JAK1 or JAK2 that cause the loss of IFN-γ function and mutations in the B2M gene, resulting in the loss of MHC-I expression and antigen presentation, are also reported in acquired ICI therapy-resistant samples51.

Genetic signatures

In a retrospective study conducted with a cohort of breast cancer patients with 1- to 5-year tumor relapse versus those with up to 7-year relapse-free survival, Ascierto et al.52 screened more than 299 immune-related genes and found that five genes (IGK [IGKC], GBP1, STAT1, IGLL5, and OCLN) were highly overexpressed in patients with relapse-free survival, highlighting their potential as predictive biomarkers. Similarly, RNA expression studies in ipilimumab-treated patients revealed that the number of immune-related genes involved in both innate and adaptive responses were overexpressed in patients with better clinical activity compared with nonresponsive patients. This suggests the importance of a pre-existing immune-active TME for better clinical response to ipilimumab. PD-L1 and PD-L2 copy number alterations (CNA) are also considered potential biomarkers53. Budczies et al.54 reported PD-L1 CNA in 22 major cancers and found a strong correlation between PD-L1 CNA and mRNA expression levels. The mutation load also correlated with PD-L1 copy number gains.

The mutational loads in exomes also have potential roles as predictive biomarkers for ICIs. Studies have shown that patients with higher mutational loads have greater responsiveness to ICIs49,55. Genetic mutations that lead to the expression of immune-related peptides that expand pre-existing T cells or that can be generated in response to immune or other stimuli can increase the efficacy of ICIs49,56. JAK3, a member of the Janus kinase signaling pathway, generally found in leukocytes, was reported to have a regulatory role in PD-L1 expression in lymphomas57. Mutations that activate JAK3 can cause overexpression of PD-L1 in lymphomas and make them responsive to PD-L1 inhibitors58,59.

Mismatch-repair mechanisms are the machinery that protects cells by repairing mutations during DNA replications. A high neoantigen load and high mutational load are associated with an improper mismatch-repair system. The identification of defective mismatch-repair mechanisms may therefore be exploited as potential predictive biomarkers. Mismatch-repair deficiency in pembrolizumab-treated patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer resulted in a high positive response, highlighting the potential of mismatch-repair deficiency as a predictive biomarker60,61. Additionally, in a recent study with 53 cancer patients, the objective response rate was 50% in patients with mismatch-repair deficiency, compared to 0% in patients with mismatch-proficient tumors60. The mismatch-deficient group, compared with the other group, also showed a longer progression-free survival61. Advances in NGS and microarray technologies have made genome-wide screening of potential markers comparatively easier. The accurate prediction of these biomarkers and their use in clinical conditions are suboptimal. However, the development of simple algorithms to read these potential gene signatures from patient DNA is necessary to make these findings clinically applicable. A PanCancer IO 360™ assay was developed by nanoString; the assay profiles TME interactions using a 770 gene panel. This panel evaluates multiple immune processes, including simultaneous assessment of immune evasion in the context of all three immune phenotypes (immune desert, immune excluded and immune inflamed) and supports the prediction of patient responses to a variety of immunotherapies, including ICIs41.

Epigenetic signatures

Epigenetic modifications are complex cellular processes that can modify cellular functions in response to the prevailing environment without altering genetic codes. Multiple epigenetic marks are involved in these complex mechanisms, including DNA methylation, post-transcriptional histone tail modifications, and short noncoding RNAs62. Although the association of multiple epigenetic regulatory mechanisms was evaluated in response to immune checkpoint expression and their applicability in combination therapy for synergistic combination, studies on the evaluation of epigenetic modifications as predictive biomarkers are warranted.

The transcriptomic and epigenetic studies on NSCLC show that the hypomethylation of the CTLA-4, PD-1, and PD-L1 promoter regions may be associated with the upregulation of these genes in the TME63. It has been shown that in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the mRNA and protein levels of PD-1 were elevated and significantly hypomethylated in both promoter and enhancer regions compared to healthy B-cell controls64.

miRNAs are small single-stranded RNA sequences that have a critical role in various diseases, including cancer65. Reports have shown that five members of the miR-200 family, miR-200a, 200b, 200c, 141, and 429, play pivotal roles in tumor suppression by restricting the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)66–68. In human breast cancer cells, it has been reported that expression of PD-L1 decreases with overexpression of miR-20069. These reports rationalize the hypothesis that miR-200 might be a promising biomarker for responders treated with anti-PD-L1 antibodies (atezolizumab or durvalumab). A recent study showed that serum miRNA levels correlated with progression-free survival and overall survival in a phase II clinical study on patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) treated with nivolumab70. Eight miRNAs were found to be associated with a better clinical response, out of which four miRNAs were positively associated with progression-free survival70. In contrast, overexpression of miR-34a has been reported as an inducer of CD8+ TILs by repressing PD-L1 expression in colorectal carcinoma and NSCLC patients71,72. These data suggest that the miRNA-PD-L1 axis might be a promising therapeutic/diagnostic biomarker target in ICI therapy.

Concluding remarks

Immunological response to ICIs is a complex process. Biomarkers that predict the efficacy of ICI therapy and irAEs should help in patient selection and decision-making by distinguishing between responders and nonresponders. Numerous studies on predictive biomarkers focusing on immune cell infiltration, peripheral blood analyses, PD-L1 overexpression, copy number alterations, neoantigen clonality, mutational landscape, mismatch-repair deficiency, SNPs, transcription factors, and miRNA are currently available (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictive biomarkers for progression-free survival and overall survival in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors

| Biomarker Category | Nonresponders | Responders |

|---|---|---|

| Immune cells | Decreased • Lymphocytes (CD4+, CD8+)14 • B Cells (CD20+)26 • Activated lymphocytes (CD134+, CD137+, and FOXP3+)26 • Natural killer cells (NKp46+)26 |

Increased • Peripheral blood absolute lymphocyte count14,15 • Absolute eosinophil count17 • Relative lymphocyte count17 • Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (CD4+, CD8+)14,74 • Teff to Treg ratio27,28 • Number of activated T cells (CD134+, CD137+, and FOXP3+)26 • Monocytes (CD16+ and CD68+)26 • CD8+PD-1hiCTLA-4hi and CD4+FOXP3-PD-1hi subpopulations31,75 Decreased peripheral blood • Absolute monocyte count17 • Myeloid-derived suppressor cells17 |

| Protein expression | • Basal level expression of PD-L143 • The loss in IFN-γ signaling in CD8+ T cells47 |

Increased • Expression of PD-L174 • PD-L1 copy number gain53,54 • Expression of IFN-γ40,45,47 • Expression of IDO47 • Th1-associated markers47 • ICOS pathway37,65,68 Decreased LDH level15–17 |

| Mutations and neoantigens | • Elimination of neoantigen-expressing tumor clones48 • Decreased neoantigen burden47,76 |

• Higher mutational load49,55 • Clonal mutations in neoantigens47,48 • Mismatch-repair deficiency60,61 • Increased neoantigen burden47 |

| Gene signatures | • Overexpression of IGK, GBP1, STAT1, IGLL5, and OCLN52 • Overexpression of immune-related peptides expanding pre-existing T cells49,56 • Activation in JAK358,59 |

|

| Epigenetic signatures | • Altered methylation pattern of PD-L126,63,64 • Higher serum levels of miRNA69–72 |

Major issues in the development of predictive biomarkers are the dynamic variations in cancer biomarker types and a patient’s genetic makeup. Biopsies obtained from multiple sites of the same patient showed variation in biomarker levels owing to intratumoral heterogeneity. Intense research will develop combination biomarker sets to predict ICI therapy outcomes and avoid irAEs73.

Although several predictive biomarker studies are completed and many are underway, the clinical validation of the identified biomarkers is necessary. More integrated approaches should be developed to identify patient-specific choices for checkpoint monotherapies or combination therapies. Moreover, next-generation sequencing techniques should become clinically applicable through the development of simple algorithms to process large quantities of clinical data. In conclusion, biomarker-driven prediction of immune therapy outcomes has the potential to make dramatic changes in cancer immunotherapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a start-up grant [VR04] for Dr. Eyad Elkord from Qatar Biomedical Research Institute, Qatar Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hodi FS, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert C, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibney GT, Weiner LM, Atkins MB. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e542–e551. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borghaei H, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garon EB, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larkin J, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng W, Fu D, Xu F, Zhang Z. Unwrapping the genomic characteristics of urothelial bladder cancer and successes with immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Oncogenesis. 2018;7:2. doi: 10.1038/s41389-017-0013-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polk A, Svane IM, Andersson M, Nielsen D. Checkpoint inhibitors in breast cancer: Current status. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013;63:122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansell SM, et al. PD-1 Blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;372:311–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer–immune set point. Nature. 2017;541:321. doi: 10.1038/nature21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Y, et al. Exposure–response relationships of the efficacy and safety of ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma. Clin. Can. Res. 2013;19:3977. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cogdill AP, Andrews MC, Wargo JA. Hallmarks of response to immune checkpoint blockade. Br. J. Cancer. 2017;117:1–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagès F, et al. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:2654–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angulo GD, Yuen C, Palla SL, Anderson PM, Zweidler-McKay PA. Absolute lymphocyte count is a novel prognostic indicator in ALL and AML. Cancer. 2008;112:407–415. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simeone E, et al. Immunological and biological changes during ipilimumab treatment and their potential correlation with clinical response and survival in patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014;63:675–683. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1545-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelderman S, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase as a selection criterion for ipilimumab treatment in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2014;63:449–458. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1528-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martens A, et al. Baseline peripheral blood biomarkers associated with clinical outcome of advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Clin. Can. Res. 2016;22:2908. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buder-Bakhaya K, Hassel JC. Biomarkers for clinical benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment—a review from the melanoma perspective and beyond. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1474. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manola J, Atkins M, Ibrahim J, Kirkwood J. Prognostic factors in metastatic melanoma: A pooled analysis of eastern cooperative oncology group trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:3782–3793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.22.3782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subrahmanyam PB, et al. Distinct predictive biomarker candidates for response to anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2018;6:18. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0328-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieg C, et al. High-dimensional single-cell analysis predicts response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 2018;24:144. doi: 10.1038/nm.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martens A, et al. Increases in absolute lymphocytes and circulating CD4( + ) and CD8( + ) T cells are associated with positive clinical outcome of melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Clin. Can. Res. 2016;22:4848–4858. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wistuba-Hamprecht K, et al. Peripheral CD8 effector memory type 1 T-cells correlate with outcome in ipilimumab-treated stage IV melanoma patients. Eur. J. Cancer. 2017;73:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Coaña YP, et al. Ipilimumab treatment decreases monocytic MDSCs and increases CD8 effector memory T cells in long-term survivors with advanced melanoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:21539–21553. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamid O, et al. A prospective phase II trial exploring the association between tumor microenvironment biomarkers and clinical activity of ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. J. Transl. Med. 2011;9:204–204. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balatoni T, et al. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells as potential biomarkers predicting response to treatment and survival in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving ipilimumab therapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018;67:141–151. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2072-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quezada SA, Peggs KS, Curran MA, Allison JP. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI27745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodi FS, et al. Immunologic and clinical effects of antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 in previously vaccinated cancer patients. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2008;105:3005–3010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712237105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daud AI, et al. Tumor immune profiling predicts response to anti–PD-1 therapy in human melanoma. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:3447–3452. doi: 10.1172/JCI87324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thommen DS, et al. A transcriptionally and functionally distinct PD-1 + CD8 + T cell pool with predictive potential in non-small-cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 blockade. Nat. Med. 2018;24:994–1004. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0057-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zappasodi R, et al. Non-conventional inhibitory CD4+Foxp3−PD-1hi T cells as a biomarker of immune checkpoint blockade activity. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:1017–1032.e1017. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu SP, et al. Stromal PD-L1 positive regulatory T cells and PD-1 positive CD8-positive T cells define the response of different subsets of non-small cell lung cancer to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018;13:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.11.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tumeh PC, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geng Y, et al. Prognostic role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015;37:1560–1571. doi: 10.1159/000438523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid P, et al. Atezolizumab in metastatic TNBC (mTNBC): Long-term clinical outcomes and biomarker analyses. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2986. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-2986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loi S, et al. LBA13 relationship between tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) levels and response to pembrolizumab (pembro) in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC): Results from KEYNOTE-086. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28:mdx440.005–mdx440.005. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx440.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liakou CI, et al. CTLA-4 blockade increases IFNγ-producing CD4( + )ICOS(hi) cells to shift the ratio of effector to regulatory T cells in cancer patients. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2008;105:14987–14992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806075105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang DN, et al. Increased frequency of ICOS( + ) CD4 T-cells as a pharmacodynamic biomarker for anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2013;1:229–234. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen H, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy results in higher CD4+ICOShi T cell frequency and IFN-γ levels in both nonmalignant and malignant prostate tissues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2009;106:2729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813175106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H, et al. CD4 T cells require ICOS-mediated PI3K-signaling to increase T-bet expression in the setting of anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014;2:167–176. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cesano A, Warren S. Bringing the next generation of immuno-oncology biomarkers to the clinic. Biomedicines. 2018;6:14. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toor SM, Elkord E. Therapeutic prospects of targeting myeloid-derived suppressor cells and immune checkpoints in cancer. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2018;96:888–897. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teng MW, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Smyth MJ. Classifying cancers based on T-cell infiltration and PD-L1. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2139–2145. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reck M, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maleki Vareki S, Garrigos C, Duran I. Biomarkers of response to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017;116:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guibert N, et al. PD-L1 expression in circulating tumor cells of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer. 2018;120:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGranahan N, et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science. 2016;351:1463–1469. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anagnostou V, et al. Evolution of neoantigen landscape during immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:264–276. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snyder A, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkins RW, Barbie DA, Flaherty KT. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Br. J. Cancer. 2018;118:9–16. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaretsky JM, et al. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:819–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1604958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ascierto ML, et al. A signature of immune function genes associated with recurrence-free survival in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012;131:871–880. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1470-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inoue Y, et al. Clinical significance of PD-L1 and PD-L2 copy number gains in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:32113–32128. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Budczies J, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of copy number changes in programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1, CD274) - associations with gene expression, mutational load, and survival. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55:626–639. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rizvi NA, et al. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gnjatic S, et al. Identifying baseline immune-related biomarkers to predict clinical outcome of immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2017;5:44. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green MR, et al. Constitutive AP-1 activity and EBV infection induce PD-L1 in Hodgkin lymphomas and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders: Implications for targeted therapy. Clin. Can. Res. 2012;18:1611. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:275. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Allen EM, et al. Long-term benefit of PD-L1 blockade in lung cancer associated with JAK3 activation. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015;3:855. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le DT, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Le DT, et al. Mismatch-repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wright J. Epigenetics: reversible tags. Nature. 2013;498:S10–11. doi: 10.1038/498S10a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marwitz S, et al. Epigenetic modifications of the immune-checkpoint genes CTLA4 and PDCD1 in non-small cell lung cancer results in increased expression. Clin. Epigenetics. 2017;9:51. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0354-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu-Monette ZY, Zhou J, Young KH. PD-1 expression and clinical PD-1 blockade in B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2018;131:68–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-740993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mongroo PS, Rustgi AK. The role of the miR-200 family in epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010;10:219–222. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.3.12548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Korpal M, Lee ES, Hu G, Kang Y. The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer cell migration by direct targeting of E-cadherin transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:14910–14914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800074200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huber MA, et al. NF-kappaB is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in a model of breast cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:569–581. doi: 10.1172/JCI200421358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noman MZ, et al. The immune checkpoint ligand PD-L1 is upregulated in EMT-activated human breast cancer cells by a mechanism involving ZEB-1 and miR-200. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1263412. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1263412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sudo K, et al. Serum microRNAs to predict the response to nivolumab in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:e14511–e14511. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.e14511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li X, Nie J, Mei Q, Han WD. MicroRNAs: novel immunotherapeutic targets in colorectal carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5317–5331. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i23.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cortez, M. A. et al. PD-L1 regulation by p53 via miR-34. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 108, djv303 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:158–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015;14:847. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Galon J, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aguiar PN, et al. The role of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a network meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 2016;8:479–488. doi: 10.2217/imt-2015-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]