Abstract

Background

Current inhaled polymyxin therapy is empirical and often large doses are administered, which can lead to pulmonary adverse effects. There is a dearth of information on the mechanisms of polymyxin-induced lung toxicity and their intracellular localization in lung epithelial cells.

Objectives

To investigate the intracellular localization of polymyxins in human lung epithelial A549 cells.

Methods

A549 cells were treated with polymyxin B and intracellular organelles (early and late endosomes, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, lysosomes and autophagosomes), ubiquitin protein and polymyxin B were visualized using immunostaining and confocal microscopy. Fluorescence intensities of the organelles and polymyxin B were quantified and correlated for co-localization using ImageJ and Imaris platforms.

Results

Polymyxin B co-localized with early endosomes, lysosomes and ubiquitin at 24 h. Significantly increased lysosomal activity and the autophagic protein LC3A were observed after 0.5 and 1.0 mM polymyxin B treatment at 24 h. Polymyxin B also significantly co-localized with mitochondria (Pearson’s R = 0.45) and led to the alteration of mitochondrial morphology from filamentous to fragmented form (n = 3, P < 0.001). These results are in line with the polymyxin-induced activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway observed in A549 cells.

Conclusions

Accumulation of polymyxins on mitochondria probably caused mitochondrial toxicity, resulting in increased oxidative stress and cell death. The formation of autophagosomes and lysosomes was likely a cellular response to the polymyxin-induced stress and played a defensive role by disassembling dysfunctional organelles and proteins. Our study provides new mechanistic information on polymyxin-induced lung toxicity, which is vital for optimizing inhaled polymyxins in the clinic.

Introduction

The world is facing a major challenge due to the prevalence of MDR Gram-negative bacteria, particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae.1–3 In the last two decades, the situation has become worse due to the lack of novel classes of antibiotics in the developmental pipeline.4 Polymyxins have been reinvigorated as a last-line therapy against these Gram-negative ‘superbugs’.5 Parenteral polymyxin therapy is associated with a high incidence (up to 60%) of nephrotoxicity in patients.6–8 Moreover, current dosing recommendations for parenteral polymyxins are suboptimal, in particular for lung infections, because of the very limited distribution of polymyxins into the infection site.9–14 Inhaled colistin (in the form of an inactive prodrug, colistimethate) has been widely used in European cystic fibrosis centres over the last three decades for the treatment of lung infections caused by P. aeruginosa.15–18 Dose fractionation studies of aerosolized polymyxin B and colistin in animals showed a significant reduction in the bacterial load as well as pulmonary inflammation.19,20 However, inhaled polymyxin therapy has never been optimized in patients using pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD), which has potentially led to a number of adverse effects.21–24 Clearly, there is an urgent need to address this issue and elucidate the mechanism underlying polymyxin-induced pulmonary toxicity.

We have recently demonstrated that polymyxin B can cause time- and concentration-dependent toxicity in lung epithelial cells via extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of apoptosis.25 Interestingly, polymyxins are more toxic to human renal tubular HK-2 cells, compared with human lung epithelial A549 cells, with significantly higher intracellular concentrations.25 Our synchrotron X-ray fluorescence microscopy data showed that polymyxins accumulate in rat (NRK-52E) and human (HK-2) kidney tubular cells at levels ∼1930–4760-fold higher than the extracellular concentrations.26 Partial co-localization of polymyxins with mitochondria was associated with nephrotoxicity in both cell culture and animal models.26–28 Significant morphological changes of mitochondria from filamentous to fragmented were also reported in NRK-52E cells after polymyxin treatment.29 To date, no information is available on the intracellular disposition of polymyxins in lung epithelial cells. The aim of this study was to investigate the intracellular localization of polymyxins in human lung epithelial cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Polymyxin B (sulphate; catalogue number 86-40302; minimum potency, 95%) and colistin (sulphate; catalogue number 86-41620; minimum potency, 95%) were purchased from Beta Pharma (Shanghai, China). Pierce™ methanol-free 16% formaldehyde (w/v, catalogue number 28908) was from Thermo Fisher Scientific and a 3.7% working solution was prepared. Permeabilizing solution (Triton X-100 solution, catalogue number T9284) and blocking reagents (goat serum, catalogue number G9023) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Melbourne, Australia). CellLightTM ER-RFP (catalogue number C10591), CellLightTM early endosome-GFP (catalogue number C10586), CellLightTM late endosome-GFP (catalogue number C10588), mouse monoclonal anti-polymyxin B IgM antibody (Invitrogen, catalogue number MA1-40133), rabbit polyclonal anti-LAMP-1 (Invitrogen, catalogue number PA1-654A), goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa® Fluor 488 (catalogue number A-11008) and goat anti-mouse IgM conjugated with Alexa® Fluor 647 (catalogue number A-21238) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Australia Pty. Ltd (Melbourne, Australia). Rabbit anti-TOMM20 (mitochondrial marker) antibody (catalogue number HPA011562) was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. Rabbit monoclonal anti-LC3A (autophagy protein marker) antibody (catalogue number 4599S) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, USA).

Cell culture

Human lung epithelial cells (A549 cells, ATCC® CCL-185™) were employed to examine the intracellular localization of polymyxins. Cells were grown and subcultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. A549 cells (1 × 105 cells/mL) were seeded in 8-well chamber slides in the supplemented DMEM at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 until 80% confluency. Cells were then treated with 0.1 mM polymyxin B in DMEM and 1% FBS for 24 h. Treated cells were fixed, permeabilized and blocked for antibody staining.

Subcellular localization of polymyxin B with endosomes and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

Cells were transfected with CellLight® Early Endosomes-GFP [a fusion construct of Ras-associated binding (Rab)5a and emerald green fluorescent protein (emGFP)] and CellLight® Late Endosomes-GFP (a fusion construct of Rab7a and emGFP), providing accurate and specific targeting to early and late endosomes, respectively. For ER staining, cells were transfected with CellLight® ER-RFP, an ER-specific fusion construct of the ER signal sequence of calreticulin, KDEL (ER retention signal) and tagged red fluorescent protein (TagRFP). After overnight incubation, cell health was examined by microscopy (EVOS® FL Auto Imaging System, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transfection was confirmed with GFP and RFP fluorescence. Cells were then treated with 0.1 mM polymyxin B for 24 h. Polymyxin B localization was examined by staining with mouse anti-polymyxin B antibody (1:500) and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa® Fluor 647 (1:250). For staining different intracellular organelles, organelle-specific antibodies were used. Imaging was conducted with a Leica SP8 (inverted) confocal microscope and images were processed using the Coloc 2 plugin by ImageJ (Version 1.51n, NIH, USA).

Effect of polymyxin treatment on the cellular protein degradation pathway

The two major pathways of selective cellular protein degradation were examined. Firstly, the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway was assessed by staining ubiquitin with rabbit polyclonal anti-ubiquitin antibody (Abcam, catalogue number ab7780; 1:500) after polymyxin B treatment (0.1 mM for 24 h). Co-localization of polymyxin B with expressed ubiquitin was studied by confocal imaging using a Leica SP8 inverted microscope. Secondly, the lysosome was assessed by staining lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP-1) with rabbit polyclonal anti-LAMP-1 (1:500). Co-localization was validated by analysing the image for the overlapping intensity of two different channels using the Coloc 2 plugin (ImageJ 1.51n, NIH, USA). The concentration-dependent effect of polymyxin B treatment (0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 mM for 24 h) on the lysosomal activity was evaluated by calculating the intensity of LysoTracker™ deep red (Life Technologies, catalogue number L12492) in live cells. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted for significance testing using GraphPad prism (Version 7.01, CA, USA).

Co-localization of polymyxin B with autophagic protein LC3A

A549 cells were treated with 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 mM polymyxin B for 24 h. Cells were then washed with PBS followed by fixation (4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min) and permeabilization (0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min). Cells were blocked with 1% goat serum for 2 h and incubated overnight with rabbit anti-LC3A monoclonal antibody (1:100) in a dark chamber at 4°C. After overnight incubation with the primary antibody, cells were incubated with the goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa® Fluor 488 (1:500). Cells were then imaged with a Leica SP8 (inverted) confocal microscope using a 63× oil immersion objective [numerical aperture (NA) 1.4]. The concentration-dependent effect of polymyxin B on autophagic protein expression was also assessed. Immunofluorescence was measured from three independent fields of each individual sample. The background was subtracted and the fluorescence intensity per cell was calculated.

Mitochondrial localization of polymyxins and changes in the mitochondrial morphology

Mitochondria were stained with rabbit polyclonal anti-TOMM20 antibody (1:500). After overnight incubation with the primary antibody at 4°C, all samples were stained with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa® Fluor 488 (1:500) for 2 h at room temperature. Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies, catalogue number H3570, 2 μg/mL) was used as a nuclear stain. Mitochondria and polymyxin B channel intensities were used for 3D visualization of polymyxin B co-localized with mitochondria. Images were collected from multiple Z-stacks of a cell and a 3D overlap of two channel intensities was created using the Imaris platform. To assess the mitochondrial morphology, cells were treated with 0.1 and 1.0 mM polymyxin B for 1, 4 and 24 h, washed with PBS and treated with 100 nM tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester (TMRE) for 45 min to stain the mitochondria. Cells were visualized under a Leica SP8 confocal microscope to identify filamentous (branched) and fragmented mitochondria in TMRE-stained viable cells. Mitochondrial morphologies were categorized into ‘filamentous’ (for long, elongated and branched networks), ‘fragmented’ (for short networks and small spheres) and ‘intermediates’ (for a mixture of networks and fragments).29,30 More than 200 cells were counted for each treatment condition and the experiments were repeated three times. NIH ImageJ software was used to count the cells with filamentous/fragmented/intermediate mitochondria. Polymyxin B-induced mitochondrial morphology changes were determined by counting the number of cells with different mitochondrial morphologies and expressed as a percentage of the total cell count.31

Imaging and image analysis

All images were representative of several cells from three separate experiments. Vehicle-treated cells were employed as the control. Background intensity of the control was subtracted from treatment groups. Coloc 2 was used to perform the pixel intensity correlation for image analysis, automatic thresholding and statistical testing. The Imaris platform was used to process the two channel intensities simultaneously and to measure the degree of overlap of the two channels. The optics of the microscope were adjusted to prevent any potential crosstalk of signals between different channels. Images were verified by collecting images of single fluorescently labelled samples with the same settings used for co-localization studies. Finally, optical sectioning was employed to capture the images of multiple sections of cells and an image of the entire 3D volume of the cells was created.

Results

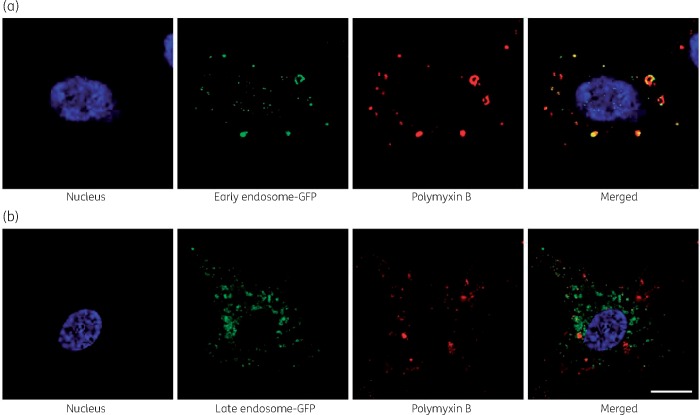

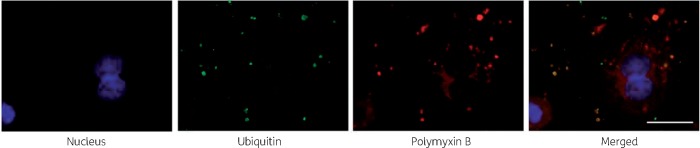

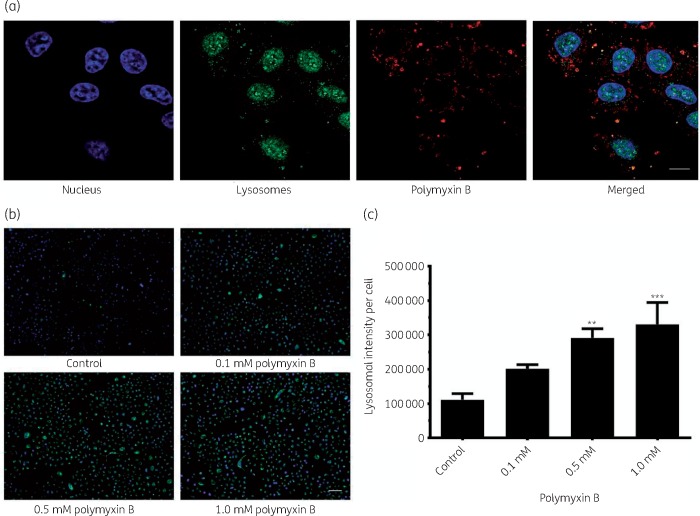

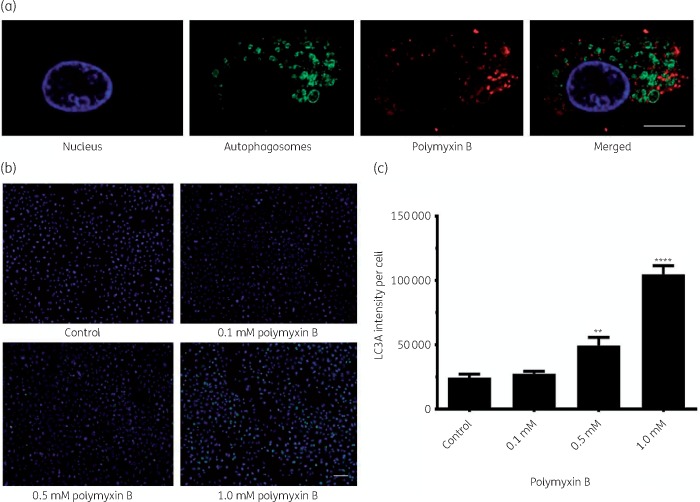

Significant co-localization of polymyxin B with early endosomes (Pearson’s R = 0.70) was observed, whereas co-localization with late endosomes was not significant (Pearson’s R = 0.10) (Figure 1a and b). Polymyxin B was also significantly co-localized with ubiquitin (Pearson’s R = 0.39, Figure 2) and lysosomes (Pearson’s R = 0.17, Figure 3). A significant increase in the lysosomal activity (measured by LysoTracker™ deep red intensity per cell) was observed in A549 cells treated with 0.5 mM (**P < 0.05) and 1.0 mM (***P < 0.001) polymyxin B for 24 h. Co-localization of polymyxin B with autophagic protein LC3A was not detected; however, an increased formation of autophagic vesicles was evident in A549 cells following 0.5 and 1.0 mM polymyxin B treatment for 24 h (Figure 4). LC3A intensity in the cells treated with 0.1 mM polymyxin B was unchanged, compared with the control. Significant increase in the LC3A intensity was observed with 0.5 mM (**P < 0.05) and 1.0 mM (****P < 0.0001) polymyxin B treatment for 24 h.

Figure 1.

Co-localization of polymyxin B with (a) early and (b) late endosomes. A549 cells were treated with 0.1 mM of polymyxin B for 24 h before immunostaining of polymyxin B. Images were obtained by subtracting the background for noise reduction and adjusting the brightness and contrast for better visibility. Scale bar = 10 μm. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Figure 2.

Co-localization of polymyxin B with ubiquitin protein in A549 cells after treatment with 0.1 mM polymyxin B for 24 h. Green intensities are from Alexa® Fluor 488 tagged with a secondary antibody to an anti-ubiquitin protein antibody and red intensities are from Alexa® Fluor 647 tagged with a secondary antibody to anti-polymyxin antibody. Scale bar = 10 μm. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Figure 3.

(a) Lysosomal localization of polymyxin B in A549 cells after treatment with 0.1 mM polymyxin B for 24 h. Lysosomes, polymyxin B and nuclei are shown in green, red and blue, respectively. Scale bar = 10 μm. (b and c) Polymyxin B induced a concentration-dependent increase in lysosomal intensity in A549 cells at 24 h. Scale bar = 100 μm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 compared with untreated control samples. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Figure 4.

(a) Polymyxin B was not co-localized with autophagosomes. Treatment with more than 0.5 mM polymyxin B caused the production of autophagosomes as large as 2 μm (merged image at the top right corner). Scale bar = 10 μm. (b) Concentration-dependent increase in the LC3A intensity; treatment with lower concentration (0.1 mM) of polymyxin B did not produce significant autophagosomes. Scale bar = 100 μm. (c) LC3A intensity per cell was plotted against different treatment conditions at 24 h. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.05 and ****P < 0.0001, compared with control samples. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

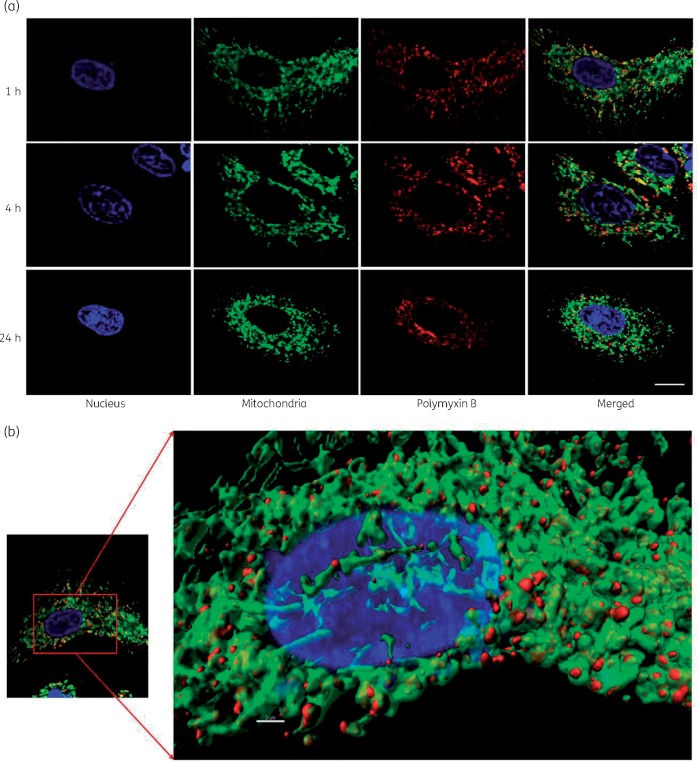

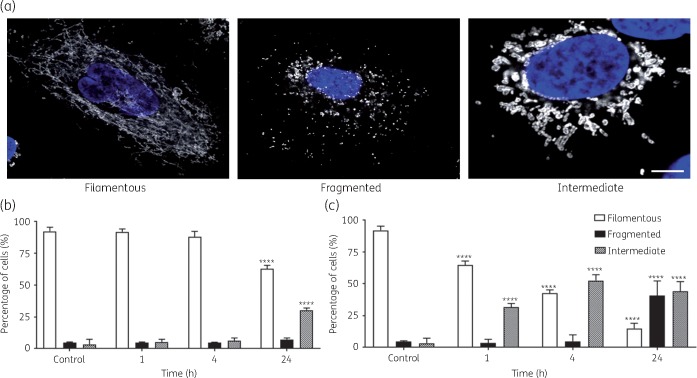

Polymyxin B co-localized with mitochondria in A549 cells (Figure 5a) and confocal images showed significant accumulation of polymyxin B on mitochondria at all three timepoints (1, 4 and 24 h). The 3D visualization indicated significant co-localization of polymyxin B with mitochondria (Figure 5b). A 3D demonstration of mitochondrial distribution in the cells without polymyxin B treatment is presented in Figure S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). Polymyxin B treatment induced significant changes in the mitochondrial morphology in A549 cells (Figure 6a). A significant number of cells with both filamentous and fragmented mitochondria at 24 h were observed after treatment with 0.1 mM polymyxin B, compared with the control (Figure 6b). A concentration- and time-dependent increase in the number of cells with fragmented mitochondria (short and disjointed) was evident; the most significant increase (****P < 0.0001) in the cells with fragmented mitochondria (40.8 ± 11.5%) was observed at 24 h following 1.0 mM polymyxin B treatment (Figure 6c).

Figure 5.

(a) Co-localization of polymyxin B (0.1 mM) with mitochondria in A549 at different timepoints. Scale bar = 5 μm. Green represents the mitochondrial outer membrane protein tagged with anti-TOMM20 antibody and Alexa® Fluor 488. Red represents the polymyxin molecule tagged with anti-polymyxin antibody and Alexa® Fluor 647. (b) Co-localization of polymyxin B (0.1 mM) in A549 cells with mitochondria using the Imaris platform after 1 h treatment. Scale bar = 3 μm. The original image is on the left with the 3D visualization of the same image using Imaris on the right. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Figure 6.

Mitochondrial morphology changes due to polymyxin B treatment. (a) Different types of mitochondria observed with 0.1 mM polymyxin treatment (filamentous, fragmented and intermediate). Scale bar = 5 μm. (b and c) Percentage of cells with different types of mitochondria with 0.1 and 1.0 mM polymyxin B-treated A549 cells at different timepoints. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). ****P < 0.0001 compared with control samples. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Discussion

Over the last few decades, inhaled polymyxins (most commonly as colistimethate) have shown favourable efficacy against Gram-negative pathogens in lung infections.32–36 Pulmonary delivery of polymyxins has the advantage of achieving significant high concentrations in the epithelial lining fluid.19,20 Considering PK/PD/toxicodynamics (PK/PD/TD), extensive accumulation of polymyxins in lung epithelial cells may potentially cause pulmonary toxicity.21–24 We have previously reported that polymyxin-induced toxicity in human lung epithelial A549 cells involves apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction.25 The present study examined the intracellular localization of polymyxins in lung epithelial cells and provides key insights into the mechanism of polymyxin-induced pulmonary toxicity.

Endocytosis is a major route of cellular drug internalization and endocytosed molecules are initially delivered to small and irregularly shaped early endosomes.37 Localization of polymyxins with early endosomes indicated a major route of polymyxin internalization in A549 cells (Figure 1). Rab proteins are critical regulators of endocytosis.38 In our study significant localization of polymyxin B was found only with the early endosome marker Rab5, but not the late endosome marker Rab7 (Pearson’s R = 0.10). This indicates that polymyxin B molecules might bind to the extracellular domain of the receptor and were subsequently internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis.39,40

Proteasomes and lysosomes are two major protein degradation pathways in eukaryotic cells.41 Ubiquitin is a 76 amino acid polypeptide and is used by proteasomes as a marker to target cytosolic and nuclear proteins for rapid degradation, whereas lysosomes are mostly involved in the digestion of extracellular proteins taken up by endocytosis as well as cytosolic proteins.42 Proteins are marked by ubiquitin attached to the amino group of the side chain of a lysine residue and degraded afterwards. Polymyxins are rich in 2,4-diaminobutyric acid (Dab) residues, which are structurally similar to lysine residues.43 The intracellular co-localization of polymyxin B with ubiquitin indicated that A549 cells might tag the polymyxin molecule with ubiquitin for rapid degradation (Figure 2), which might play a significant role in cellular defence mechanisms, as well as polymyxin metabolism.

Lysosomes are membrane-enclosed compartments filled with ∼40 types of hydrolytic enzymes (e.g. glycosidases, lipases, nucleases, phospholipases, phosphatases, proteases and sulphatases) which are used to control the intracellular digestion of macromolecules.44 Polymyxin B was also co-localized with lysosomes and caused a concentration-dependent increase in the lysosomal activity (Figure 3). LysoTracker™ deep red is a pH-dependent dye; the lysosomal pH reduced (more acidic) as polymyxin B concentration in lysosomes increased (Figure 3). Lysosomal drug sequestration plays an important role in the acquired resistance to doxorubicin in MCF-7 breast tumour cells.45 Co-localization of polymyxins with lysosomes and ubiquitin may indicate the degradation of polymyxins in lung epithelial cells and the subsequent lysosomal exocytosis.46

Although polymyxin B was not co-localized with autophagosomes, a concentration-dependent increase of the autophagic protein LC3A was observed after treatment with 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 mM polymyxin B at 24 h (Figure 4). Significant increase of LC3A in formed autophagosomes was evident at 24 h after 0.5 mM (**P < 0.05) and 1.0 mM (****P < 0.0001) polymyxin B treatment (Figure 4). Autophagy is a self-degradative process to balance different sources of energy for cellular development and in response to stresses.45 The formation of the autophagosome and lysosome is a cellular response to stress and they are destructive mechanisms to disassemble unnecessary or dysfunctional components. They also play a housekeeping role in removing misfolded proteins, damaged mitochondria, ER and peroxisomes.47 Measured by an increase in LC3A intensity, treatment with high concentrations of polymyxin B (≥0.5 mM) induced a dose-dependent increase in the autophagy process in lung epithelial cells. In kidney tubular and neuron cells, it has been reported that polymyxin B induced an increase in autophagic protein LC3A in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating that polymyxins induced autophagic cell death in mammalian cells.28,48

Mitochondria are essential for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis and dysfunction leads to oxidative stress and cell death.49 Polymyxins mainly co-localized with mitochondria in A549 and caused concentration- and time-dependent changes in the mitochondrial morphology (Figures 5 and 6). Mitochondrial morphology from networked to fragmented is regulated via mitochondrial fusion and fission processes in response to cellular stresses.50 A tendency of losing mitochondrial membrane protein TOMM-20 was discovered with increased accumulation of polymyxins in A549 cells (Figure S2). In our previous study, we demonstrated concentration- and time-dependent effects of polymyxin B on decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, increased mitochondrial oxidative stress and increased caspase-9 activation in A549 cells.25 Collectively, our findings demonstrated that polymyxin treatment caused mitochondrial toxicity (e.g. membrane depolarization, oxidative stress and morphology) and triggered the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway in lung epithelial cells.25

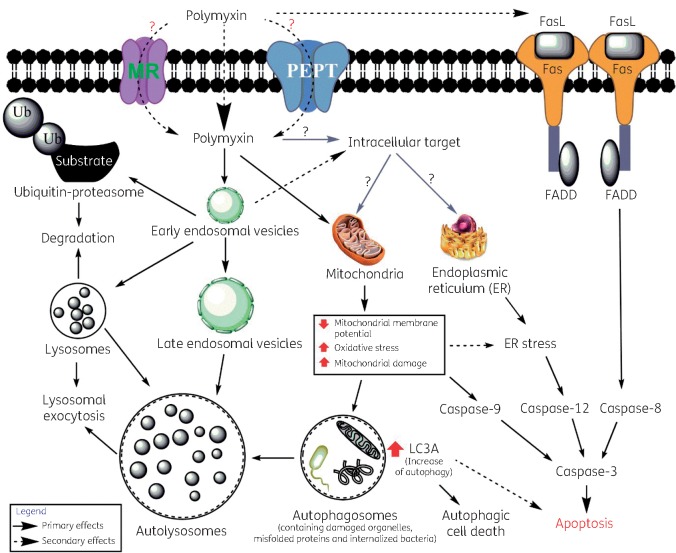

Polymyxins partially co-localized with ER in rat renal tubular cells and up-regulated several proteins involved in the ER pathway in murine nephrotoxicity models.27,28 However, no co-localization of polymyxins within ER was observed in lung epithelial cells (Figure S3). This indicates that the intracellular localization of polymyxins is different in different types of cells, and in A549 cells the ER pathway in polymyxin-induced toxicity may be secondary to mitochondrial dysfunction.51 Like polymyxin B, colistin also co-localized with ubiquitin and lysosomes and mitochondria (Figures S4 and S5), which indicates both lipopeptides share similar intracellular targets for toxicity and might have similar effects on the protein degradation pathways. Polymyxins also activate the death receptor pathway of apoptosis by increasing FasL expression and caspase-8 activation in both lung and kidney epithelial cells.25,29 The polymyxin-induced interplay between different cellular trafficking and apoptosis pathways is still not clear and requires further investigation. Nevertheless, based upon our findings and the literature, we proposed putative cellular trafficking and potential toxicity pathways due to polymyxin treatment in lung epithelial cells (Figure 7). Polymyxins may bind to the extracellular domain of the endocytic receptor megalin (MR) and be internalized via early endosomes.52–55 Oligopeptide transporter 2 (PEPT2) may play a significant role in the uptake of polymyxins.56,57 Mitochondrial toxicity and an increase in autophagy may play a significant role in polymyxin-induced apoptosis and cell death.25,58,59

Figure 7.

A proposed model of cellular trafficking and toxicity effect of polymyxins in A549 cells. FasL, Fas ligand; FADD, Fas-associated protein with death domain; Ub, ubiquitin. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to reveal the intracellular localization and trafficking of polymyxins in lung epithelial cells and provides key mechanistic information for optimization of inhaled polymyxins in patients. PK/PD approaches are required to decrease the exposure and apoptotic effect of polymyxins in lung epithelial cells, thereby minimizing their potential pulmonary toxicity and widening the therapeutic window of polymyxin inhalation therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Monash Micro Imaging, Monash University, Australia for their technical support.

Funding

This study was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC, APP1104581). J. L, Q. T. Z. and T. V. are supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH, R01 AI132681). M. U. A. is supported by Monash Graduate Scholarship and Stan Robson Rural Pharmacy Equity Scholarship. J. L. is an NHMRC Senior Research Fellow and T. V. is an NHMRC Industry Career Development Fellow.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1. Kohlenberg A, Schwab F, Meyer E. et al. Regional trends in multidrug-resistant infections in German intensive care units: a real-time model for epidemiological monitoring and analysis. J Hosp Infect 2009; 73: 239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Samuelsen O, Toleman MA, Sundsfjord A. et al. Molecular epidemiology of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Norway and Sweden shows import of international clones and local clonal expansion. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54: 346–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wadl M, Heckenbach K, Noll I. et al. Increasing occurrence of multidrug-resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from four German university hospitals, 2002–2006. Infection 2010; 38: 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schäberle TF, Hack IM.. Overcoming the current deadlock in antibiotic research. Trends Microbiol 2014; 22: 165–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Benjamin DK Jr. et al. 10×’20 progress—development of new drugs active against Gram-negative bacilli: an update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56: 1685–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karaiskos I, Giamarellou H.. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens: current and emerging therapeutic approaches. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014; 15: 1351–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pogue JM, Lee J, Marchaim D. et al. Incidence of and risk factors for colistin-associated nephrotoxicity in a large academic health system. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53: 879–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vattimo MFF, Watanabe M, da Fonseca CD. et al. Polymyxin B nephrotoxicity: from organ to cell damage. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0161057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garonzik SM, Li J, Thamlikitkul V. et al. Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and formed colistin in critically ill patients from a multicenter study provide dosing suggestions for various categories of patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 3284–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sandri AM, Landersdorfer CB, Jacob J. et al. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous polymyxin B in critically ill patients: implications for selection of dosage regimens. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57: 524–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zavascki AP, Goldani LZ, Li J. et al. Polymyxin B for the treatment of multidrug-resistant pathogens: a critical review. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 60: 1206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Antoniu SA, Cojocaru I.. Inhaled colistin for lower respiratory tract infections. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2012; 9: 333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yapa SWS, Li J, Patel K. et al. Pulmonary and systemic pharmacokinetics of inhaled and intravenous colistin methanesulfonate in cystic fibrosis patients: targeting advantage of inhalational administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 2570–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheah SE, Wang J, Nguyen VT. et al. New pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies of systemically administered colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in mouse thigh and lung infection models: smaller response in lung infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70: 3291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koerner-Rettberg C, Ballmann M.. Colistimethate sodium for the treatment of chronic pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis: an evidence-based review of its place in therapy. Core Evid 2014; 9: 99–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lu Q, Luo R, Bodin L. et al. Efficacy of high-dose nebulized colistin in ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Anesthesiology 2012; 117: 1335–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Westerman EM, De Boer AH, Le Brun PP. et al. Dry powder inhalation of colistin in cystic fibrosis patients: a single dose pilot study. J Cyst Fibros 2007; 6: 284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Westerman EM, Le Brun PP, Touw DJ. et al. Effect of nebulized colistin sulphate and colistin sulphomethate on lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis: a pilot study. J Cyst Fibros 2004; 3: 23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin YW, Zhou Q, Onufrak NJ. et al. Aerosolized polymyxin B for treatment of respiratory tract infections: determination of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic indices for aerosolized polymyxin B against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a mouse lung infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e00211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin YW, Zhou QT, Cheah SE. et al. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of pulmonary delivery of colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a mouse lung infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e02025-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leong KW, Ong S, Chee HL. et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to high-dose colistin aerosol therapy. Int J Infect Dis 2010; 14: e1018–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lepine PA, Dumas A, Boulet LP.. Pulmonary eosinophilia from inhaled colistin. Chest 2017; 151: e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCoy KS. Compounded colistimethate as possible cause of fatal acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 2310–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wahby K, Chopra T, Chandrasekar P.. Intravenous and inhalational colistin-induced respiratory failure. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50: e38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahmed MU, Velkov T, Lin YW. et al. Potential toxicity of polymyxins in human lung epithelial cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e02690-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azad MA, Roberts KD, Yu HH. et al. Significant accumulation of polymyxin in single renal tubular cells: a medicinal chemistry and triple correlative microscopy approach. Anal Chem 2015; 87: 1590–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yun B, Azad MA, Nowell CJ. et al. Cellular uptake and localization of polymyxins in renal tubular cells using rationally designed fluorescent probes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 7489–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dai C, Li J, Tang S. et al. Colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice involves the mitochondrial, death receptor, and endoplasmic reticulum pathways. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 4075–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Azad MA, Akter J, Rogers KL. et al. Major pathways of polymyxin-induced apoptosis in rat kidney proximal tubular cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 2136–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giedt RJ, Fumene Feruglio P. et al. Computational imaging reveals mitochondrial morphology as a biomarker of cancer phenotype and drug response. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 32985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arppe R, Carro-Temboury MR, Hempel C. et al. Investigating dye performance and crosstalk in fluorescence enabled bioimaging using a model system. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0188359.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haworth CS, Foweraker JE, Wilkinson P. et al. Inhaled colistin in patients with bronchiectasis and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 975–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Karvouniaris M, Makris D, Zygoulis P. et al. Nebulised colistin for ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 1732–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kwa ALH, Loh C, Low JGH. et al. Nebulized colistin in the treatment of pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41: 754–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maselli DJ, Keyt H, Restrepo MI.. Inhaled antibiotic therapy in chronic respiratory diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18: 1026–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naesens R, Vlieghe E, Verbrugghe W. et al. A retrospective observational study on the efficacy of colistin by inhalation as compared to parenteral administration for the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia associated with multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11: 317–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kou L, Sun J, Zhai Y. et al. The endocytosis and intracellular fate of nanomedicines: implication for rational design. Asian J Pharm Sci 2013; 8: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jovic M, Sharma M, Rahajeng J. et al. The early endosome: a busy sorting station for proteins at the crossroads. Histol Histopathol 2010; 25: 99–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Woodman PG. Biogenesis of the sorting endosome: the role of Rab5. Traffic 2000; 1: 695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hunker CM, Kruk I, Hall J. et al. Role of Rab5 in insulin receptor-mediated endocytosis and signaling. Arch Biochem Biophys 2006; 449: 130–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cooper GM. The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd edn. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42. von Mikecz A. The nuclear ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Cell Sci 2006; 119: 1977–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Velkov T, Roberts KD, Nation RL. et al. Pharmacology of polymyxins: new insights into an ‘old’ class of antibiotics. Future Microbiol 2013; 8: 711–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J. et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edn. New York, NY, USA: Garland Science, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Guo B, Tam A, Santi SA. et al. Role of autophagy and lysosomal drug sequestration in acquired resistance to doxorubicin in MCF-7 cells. BMC Cancer 2016; 16: 762–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhitomirsky B, Assaraf YG.. Lysosomal accumulation of anticancer drugs triggers lysosomal exocytosis. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 45117–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF.. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol 2010; 221: 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang L, Zhao Y, Ding W. et al. Autophagy regulates colistin-induced apoptosis in PC-12 cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 2189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Olszewska A, Szewczyk A.. Mitochondria as a pharmacological target: Magnum overview. IUBMB Life 2013; 65: 273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu S, Zhou F, Zhang Z. et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress causes mitochondrial fragmentation via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission-fusion proteins. FEBS J 2011; 278: 941–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Foufelle F, Fromenty B.. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in drug-induced toxicity. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2016; 4: e00211.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Suzuki T, Yamaguchi H, Ogura J. et al. Megalin contributes to kidney accumulation and nephrotoxicity of colistin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 6319–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Christensen EI, Birn H.. Megalin and cubilin: multifunctional endocytic receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2002; 3: 256–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lundgren S, Carling T, Hjälm G. et al. Tissue distribution of human gp330/megalin, a putative Ca2+-sensing protein. J Histochem Cytochem 1997; 45: 383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Buchäckert Y, Rummel S, Vohwinkel CU. et al. Megalin mediates transepithelial albumin clearance from the alveolar space of intact rabbit lungs. J Physiol 2012; 590: 5167–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lu X, Chan T, Xu C. et al. Human oligopeptide transporter 2 (PEPT2) mediates cellular uptake of polymyxins. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71: 403–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ma Z, Wang J, Nation RL. et al. Renal disposition of colistin in the isolated perfused rat kidney. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 2857–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ching JK, Ju JS, Pittman SK. et al. Increased autophagy accelerates colchicine-induced muscle toxicity. Autophagy 2013; 9: 2115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Meyer JN, Leung MC, Rooney JP. et al. Mitochondria as a target of environmental toxicants. Toxicol Sci 2013; 134: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.