Precise control of the expression of virulence genes is essential for successful infection of apple hosts by the fire blight pathogen, Erwinia amylovora. The presence and buildup of a signaling molecule called cyclic di-GMP enables the expression and function of some virulence determinants in E. amylovora, such as amylovoran production and biofilm formation. However, other determinants, such as those for motility and the type III secretion system, are expressed and functional when cyclic di-GMP is absent. Here, we report studies of enzymes called phosphodiesterases, which function in the degradation of cyclic di-GMP. We show the importance of these enzymes in virulence gene regulation and the ability of E. amylovora to cause plant disease.

KEYWORDS: EAL domain, cyclic di-GMP, exopolysaccharide, fire blight, flagellar motility, levan

ABSTRACT

Cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) is a ubiquitous bacterial second messenger molecule that is an important virulence regulator in the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Intracellular levels of c-di-GMP are modulated by diguanylate cyclase (DGC) enzymes that synthesize c-di-GMP and by phosphodiesterase (PDE) enzymes that degrade c-di-GMP. The regulatory role of the PDE enzymes in E. amylovora has not been determined. Using a combination of single, double, and triple deletion mutants, we determined the effects of each of the four putative PDE-encoding genes (pdeA, pdeB, pdeC, and edcA) in E. amylovora on cellular processes related to virulence. Our results indicate that pdeA and pdeC are the two phosphodiesterases most active in virulence regulation in E. amylovora Ea1189. The deletion of pdeC resulted in a measurably significant increase in the intracellular pool of c-di-GMP, and the highest intracellular concentrations of c-di-GMP were observed in the Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and Ea1189 ΔpdeABC mutants. The regulation of virulence traits due to the deletion of the pde genes showed two patterns. A stronger regulatory effect was observed on amylovoran production and biofilm formation, where both Ea1189 ΔpdeA and Ea1189 ΔpdeC mutants exhibited significant increases in these two phenotypes in vitro. In contrast, the deletion of two or more pde genes was required to affect motility and virulence phenotypes. Our results indicate a functional redundancy among the pde genes in E. amylovora for certain traits and indicate that the intracellular degradation of c-di-GMP is mainly regulated by pdeA and pdeC, but they also suggest a role for pdeB in regulating motility and virulence.

IMPORTANCE Precise control of the expression of virulence genes is essential for successful infection of apple hosts by the fire blight pathogen, Erwinia amylovora. The presence and buildup of a signaling molecule called cyclic di-GMP enables the expression and function of some virulence determinants in E. amylovora, such as amylovoran production and biofilm formation. However, other determinants, such as those for motility and the type III secretion system, are expressed and functional when cyclic di-GMP is absent. Here, we report studies of enzymes called phosphodiesterases, which function in the degradation of cyclic di-GMP. We show the importance of these enzymes in virulence gene regulation and the ability of E. amylovora to cause plant disease.

INTRODUCTION

Erwinia amylovora is a Gram-negative phytopathogen that is the causal agent of fire blight, a devastating disease that affects rosaceous plants, such as apples and pears. The pathogen infects flowers, leaves at shoot tips, and rootstock crowns, with infections causing yield losses, death of branches, and sometime death of entire trees (1). The initial buildup of E. amylovora cell inoculum on apple trees occurs on flower stigmas, where pathogen populations can grow to >1 × 106 CFU/flower under conducive conditions (2). Motile bacteria then migrate to the base of flowers and infect through natural openings in the nectaries. After flower infection, E. amylovora cells migrate systemically through the host, leading to water soaking and tissue necrosis, which contribute to the characteristic “burnt” appearance of the aerial parts of the plants (3). During systemic migration through flower pedicels and stem tissue, E. amylovora cells can also emerge as ooze droplets, which consist of cells embedded in the exopolysaccharide (EPS) amylovoran (4, 5). Ooze serves as a source of bacterial inoculum for the subsequent infection of leaves at shoot tips.

During flower and leaf infection, E. amylovora uses the type III secretion system (T3SS) to deliver to plant cells effector proteins that suppress host defense responses and initiate pathogenesis (6). Following initial infection of leaves, E. amylovora cells migrate to leaf veins and colonize xylem vessels, forming biofilms within these vessels (7). Three EPSs, amylovoran, levan, and cellulose, are required for biofilm formation (7, 8). Biofilm formation also plays a critical role in adaptation of E. amylovora to temperature gradients during infection (9). Amylovoran biosynthesis is encoded by the ams operon, with amsG being the first gene in the operon (7). As E. amylovora cells migrate out of infected leaves, they can burst out of xylem vessels and continue to spread throughout the host in the intercellular spaces of cortical parenchyma cells (10), where they again use the T3SS to infect plant cells. The structural genes of the E. amylovora T3SS and the major effector DspA/DspE are encoded within the 33.4-kb hrp pathogenicity island (11); hrp genes are encoded within a set of operons whose expression is under the control of the alternate sigma factor HrpL (12). The HrpL regulon also includes genes encoding type III effectors and other non-T3SS proteins that are scattered throughout the genome (13). The hrpL gene is regulated at the transcriptional level by HrpS (σ54-dependent enhancer binding protein) along with RpoN (σ54), YbjN (modulator protein), and the integration host factor IHF (14–16).

The ability of E. amylovora cells to transition between T3SS-mediated infection and the biofilm formation-associated phase involves complex transcriptional regulation, as genes required for biofilm formation and type III secretion are differentially regulated (17–19). We have recently shown that the second messenger molecule bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic diguanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) is a major regulator of all of the critical virulence phenotypes, including amylovoran production, biofilm formation, T3SS, and flagellar motility in E. amylovora (20), and likely plays a critical role in regulating the orchestration of pathogenesis. c-di-GMP is a ubiquitous bacterial second messenger that is known to regulate the transition between a motile and sessile lifestyle and numerous virulence traits, such as EPS production, biofilm formation, and motility (19, 21, 22). Diguanylate cyclase (DGC) enzymes are responsible for the synthesis of c-di-GMP, and phosphodiesterase (PDE) enzymes are responsible for c-di-GMP degradation. Proteins with active GGDEF domains function as DGCs, and proteins with active EAL or HD-GYP domains function as PDEs that degrade c-di-GMP into either 5′-phosphoguanylyl-(3′→5′)-guanosine (pGpG) or GMP, respectively (21, 22).

E. amylovora encodes five genes with GGDEF domains (edc genes), and c-di-GMP synthesis has been shown to positively regulate amylovoran production and biofilm formation and negatively regulate flagellar motility and virulence by the downregulation of T3SS-encoding genes (20). c-di-GMP is similarly important in regulating virulence traits in other plant-pathogenic bacteria, such as by biofilm formation and attachment in Agrobacterium tumefaciens (23), motility and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi (24), extracellular enzyme production and motility in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris (25), and biofilm formation and insect vector transmission in Xylella fastidiosa (26). In other bacterial plant pathogens closely related to the Erwinia-Pantoea clade (27), c-di-GMP regulates the production of secreted enzymes, such as pectinases and proteases in Pectobacterium atrosepticum (28), and it is a major regulator of the T3SS in Dickeya dadantii (29).

Based on the preexisting evidence demonstrating that c-di-GMP is an important signaling molecule that impacts biofilm formation, EPS production, motility, and virulence in E. amylovora, we hypothesized that deletion of the genes encoding PDEs would result in upregulation of biofilm formation and EPS production, as well as in downregulation of motility and virulence. Single, double, and triple deletion mutants of the three EAL-encoding (pde) genes and the GGDEF/EAL-encoding gene edcA in E. amylovora were generated and evaluated in a combination of in vitro and in planta quantitative and phenotypic assays in order to assess the virulence factors known to be affected by c-di-GMP.

RESULTS

Erwinia amylovora encodes four putative phosphodiesterase enzymes.

Bioinformatic analysis of the E. amylovora genome revealed three genes encoding EAL domains and one gene encoding both a GGDEF and an EAL domain (Fig. S1). No genes encoding an HD-GYP domain were found in our analysis. The three EAL domain-encoding genes were designated pdeA, pdeB, and pdeC (for phosphodiesterase), and the dual domain-containing gene was named edcA in a previous study (19). PdeA and PdeB have an N-terminal CSS motif, a periplasmic sensing domain commonly associated with the EAL domain (30). PdeC has an N-terminal GAPES3 domain (gammaproteobacterial periplasmic sensor domain), followed by an HAMP domain, which is characteristic of bacterial sensor and chemotaxis proteins and functions in regulating phosphorylation of receptors in response to conformational changes in the structure of the acceptor domains (31). In addition, all three EAL proteins have predicted transmembrane domains surrounding the N-terminal signaling domains (Fig. S1). EdcA contains three consecutive N-terminal PAS domains, a class of general bacterial receptors involved in sensing various stimuli, but no predicted membrane spanning domains (20).

PdeA and PdeC are the most active E. amylovora PDEs.

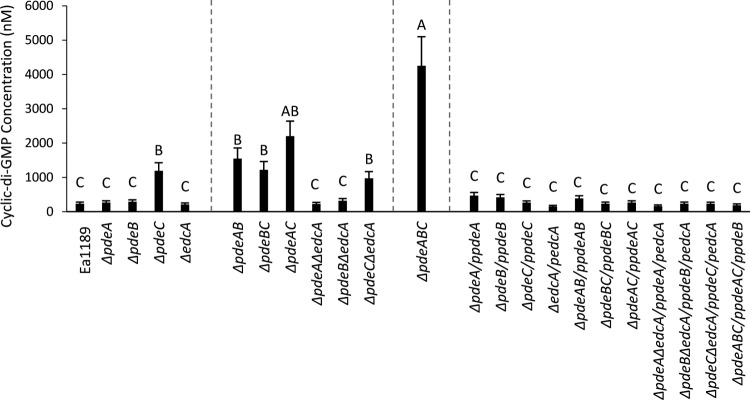

To evaluate the effect of the deletion of individual pde genes, we quantified the intracellular levels of c-di-GMP in E. amylovora cells grown in LB using ultraperformance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). The single-deletion mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeA, Ea1189 ΔpdeB, and Ea1189 ΔedcA produced c-di-GMP at levels that were not significantly different from those of the wild-type (WT) strain, while Ea1189 ΔpdeC produced significantly higher levels of c-di-GMP than did the WT strain (Fig. 1). The deletion of multiple pde genes in combination resulted in significantly increased c-di-GMP levels in every combination. When one of the pde genes was deleted along with edcA, the double mutants had similar c-di-GMP levels as the respective pde single mutants. Mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and Ea1189 ΔpdeABC showed the greatest increase in c-di-GMP levels, approximately 10-fold (Fig. 1). Complementation of all of the mutants restored the levels of c-di-GMP to the WT levels (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Intracellular levels of c-di-GMP for WT E. amylovora Ea1189, pde and edcA mutant strains, and complemented mutants, measured in strains grown in LB using ultraperformance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. Data represent three biological replicates, and error bars represent standard error of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Tukey’s honestly significant difference [HSD] test).

Increased levels of c-di-GMP significantly disrupt swimming motility in E. amylovora.

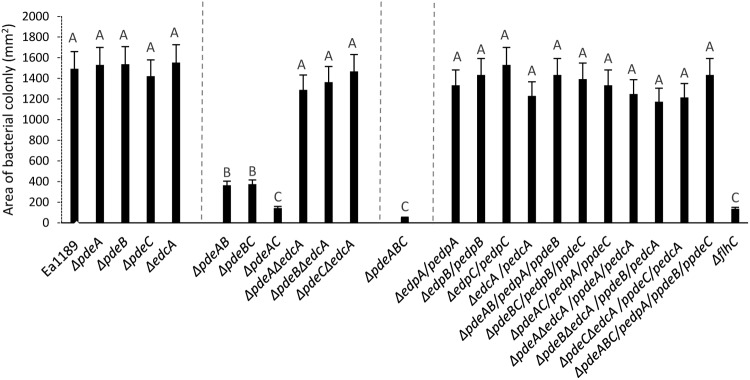

The single-deletion mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeA, Ea1189 ΔpdeB, Ea1189 ΔpdeC, and Ea1189 ΔedcA exhibited similar levels of flagellar swimming motility that were not significantly different from that of the WT (Fig. 2). When edcA was deleted along with another pde gene, WT levels of flagellar motility were still retained (Fig. 2). However, the double mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeAB and Ea1189 ΔpdeBC were indistinguishable from the nonmotile mutant Ea1189 ΔflhC, which lacks the critical flagellar transcriptional regulator FlhC, as well as from Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and Ea1189 ΔpdeABC mutants, which exhibited severely reduced motility that was significantly decreased compared to that of Ea1189 ΔflhC (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Swimming motility (area of colony expansion) for WT E. amylovora Ea1189, pde and edcA mutant strains, and complemented mutants measured 48 hpi on a motility agar plate. Data represent three biological replicates, and error bars represent standard error of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Tukey’s honestly significant difference [HSD] test).

Amylovoran production and biofilm formation are significantly increased in pde mutants.

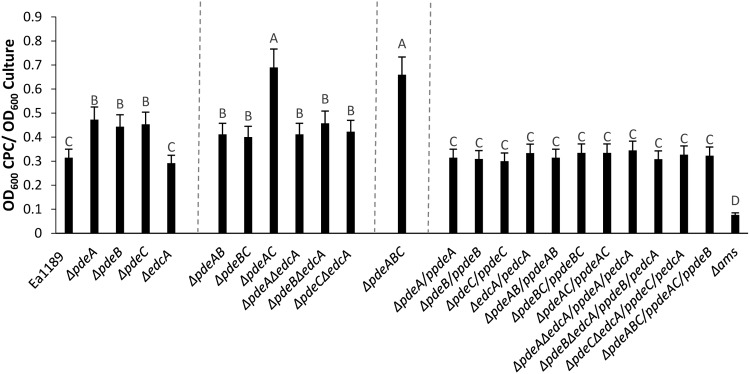

We observed a significant increase in amylovoran levels in the pde single-deletion mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeA, Ea1189 ΔpdeB, and Ea1189 ΔpdeC (Fig. 3) compared to that of the WT strain. In contrast, the deletion of edcA did not have any positive impact on amylovoran production (Fig. 3). Two of the double mutants, Ea1189 ΔpdeAB and Ea1189 ΔpdeBC produced elevated amounts of amylovoran that were not significantly different than those any of the single-gene pde mutants (Fig. 3). In addition, when edcA was deleted along with one of the pde genes, a significant elevation was observed in amylovoran production compared to that of WT Ea1189 (Fig. 3), but the amount of amylovoran production was not increased compared to that of any of the single gene pde mutants. The double mutant Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and the triple mutant Ea1189 ΔpdeABC both produced the largest amounts of amylovoran among all of the strains tested (Fig. 3). Complementation of all mutants restored the WT levels of amylovoran production (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Amylovoran production in vitro for WT E. amylovora Ea1189, pde and edcA mutant strains, complemented mutants, and Ea1189 Δams (negative control) 48 hpi at 28°C in MBMA minimal media amended with sorbitol. Data represent three biological replicates, and error bars represent standard error of the means. Letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Tukey’s honestly significant difference [HSD] test).

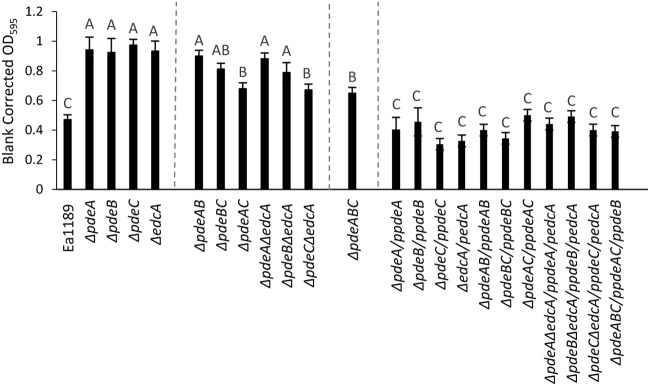

As observed with amylovoran production, biofilm formation was also significantly increased in the single-deletion mutants, Ea1189 ΔpdeA, Ea1189 ΔpdeB, and Ea1189 ΔpdeC, and in two of the double mutants, Ea1189 ΔpdeAB and Ea1189 ΔpdeBC (Fig. 4). Ea1189 ΔedcA also exhibited a significant increase in biofilm formation despite producing amylovoran at WT Ea1189 levels (Fig. 3 and 4). Ea1189 ΔpdeC ΔedcA also produced biofilm at lower levels compared to those of the other pde edcA double mutants (Fig. 4). Biofilm formation was significantly increased in the double mutant Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and the triple mutant Ea1189 ΔpdeABC compared to that of the WT strain, as well; however, the biofilm formation in these mutants was lower than that observed in all the pde single mutants and in Ea1189 ΔpdeAB and Ea1189 ΔpdeBC (Fig. 4). Complementation of all mutants restored biofilm formation to the levels of the WT Ea1189 (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Quantification of in vitro biofilm production for WT E. amylovora Ea1189, pde and edcA mutant strains, and complemented mutants on glass coverslips 48 hpi at 28°C. Data represent three biological replicates, and error bars represent standard error of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Tukey’s HSD test).

Elevated levels of c-di-GMP inhibit virulence.

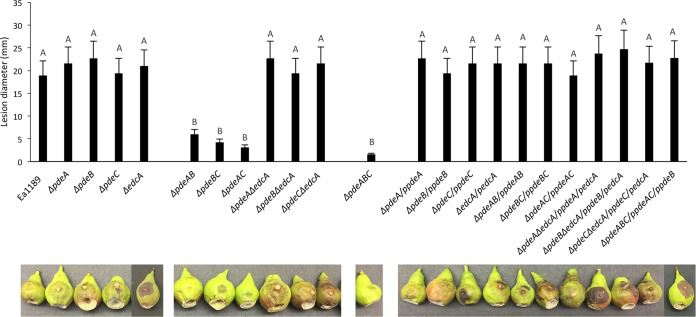

We used the immature pear and apple shoot infection disease models to assess virulence in the Δpde mutants. Virulence was measured as the amount of necrosis and length of shoot blight lesions in immature pear and apple shoots, respectively, and E. amylovora populations were also quantified over time during infection of immature pear fruit. In both infection models, virulence of the single-deletion mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeA, Ea1189 ΔpdeB, and Ea1189 ΔpdeC was not significantly different from that of the WT Ea1189 (Fig. 5, Fig. S2, and Fig. S4). Also, in both infection models, we observed a significant decrease in virulence in the three double mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeAB, Ea1189 ΔpdeAC, and Ea1189 ΔpdeBC and in the triple mutant Ea1189 ΔpdeABC, with no differences observed among these mutant strains (Fig. S2, Fig. S4, and Fig. 5). Complementation of all of the mutants with their respective gene(s) resulted in virulence restored to WT levels (Fig. 5 and Fig. S2).

FIG 5.

Diameters of necrotic lesions in immature pears (cultivar Bartlett) 5 days postinoculation with WT Ea1189, pde mutant strains, and complemented mutants and representative images of these infections. Data represent two biological replicates, and error bars represent standard error of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Tukey’s HSD test).

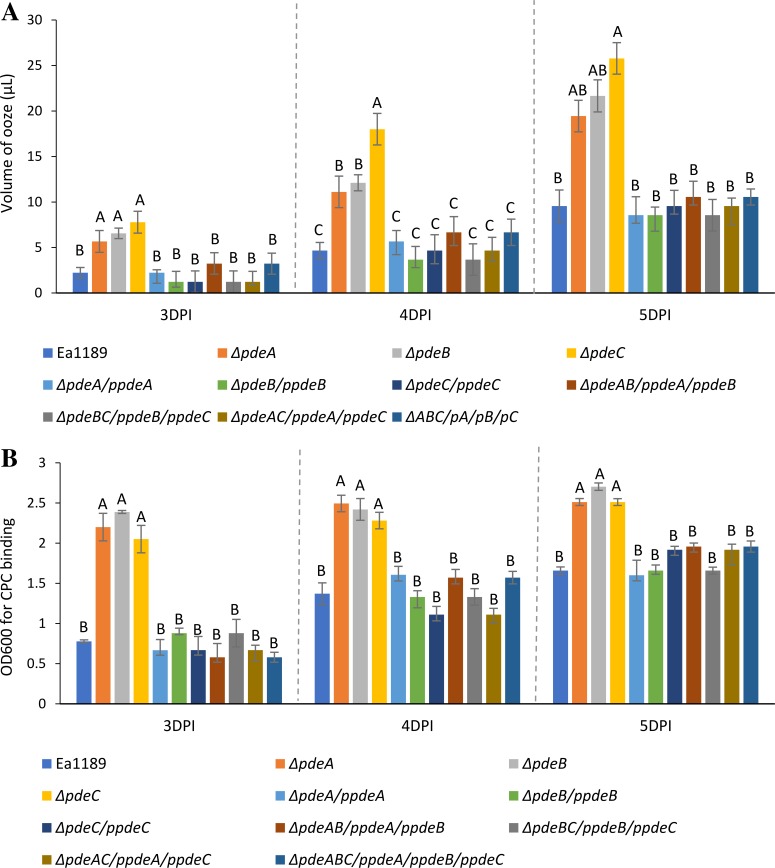

In the immature pear infection model, we typically observed a bacterial ooze droplet emerging from the site of inoculation (Fig. 5). Since ooze droplets are mainly composed of E. amylovora cells and the EPS amylovoran (4, 32) and we had observed increased amylovoran production in vitro by the pde mutants we quantified the volume of ooze exudate from immature pear infections for each of the mutants. The single-deletion mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeA, Ea1189 ΔpdeB, and Ea1189 ΔpdeC produced significantly larger ooze droplets by volume compared to those of the WT Ea1189, and these ooze droplets increased in volume over the course of infection (Fig. 6A). In addition, the amylovoran content in the ooze droplets was also significantly higher in the single-deletion mutants compared to that in the WT (Fig. 6B). The double and triple pde mutants did not produce any visible ooze on the pear surface and hence were not included in ooze volume and bacterial population measurements (Fig. 6A and B). Complementation of all of the mutants with their respective pde gene(s) resulted in restoration of ooze droplet volume and amylovoran content to WT levels (Fig. 6A and B). Although we observed differences in ooze droplet volume and amylovoran content among some of the mutants, the E. amylovora population sizes within the ooze droplets were not significantly different between any of the mutant strains and the WT Ea1189 (Fig. S3).

FIG 6.

(A) Volume of ooze droplet emerging from disease lesions on immature pears infected with WT E. amylovora Ea1189, pde mutants, and complemented mutant strains. Data for double and triple mutants, as well as for the negative control, Ea1189 Δams, are not shown here due to the absence of ooze emergence in immature pears infected with these strains. (B) Amylovoran content in the ooze droplets emerging from immature pears infected with WT E. amylovora Ea1189, pde mutant strains, and complemented mutants. Data for double and triple mutants, as well as for the negative control, Ea1189 Δams, are not shown here, due to the absence of ooze formation in immature pears infected with these strains. For both panels A and B, data represent three biological replicates, and error bars represent standard error of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Tukey’s HSD test).

Regulation of type III secretion and amylovoran biosynthesis genes in Δpde mutants.

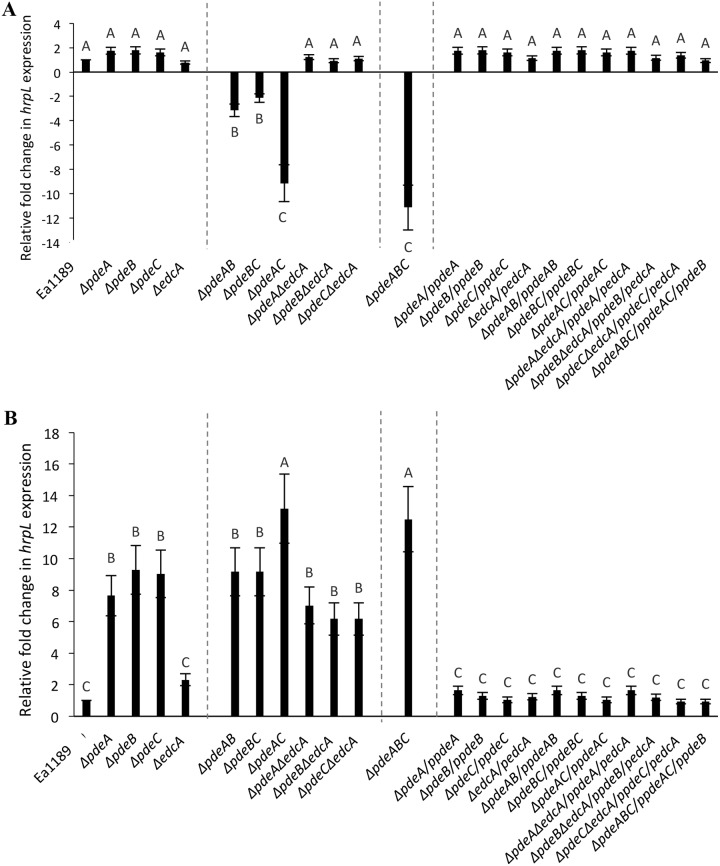

We used the hrpL and amsG genes as proxies for assessing the effects of the Δpde mutants and elevated c-di-GMP in cells on T3SS and amylovoran biosynthesis gene expression, respectively. In E. amylovora, hrpL encodes the alternate sigma factor required for the transcription of T3SS-related genes (33), and amsG is the first gene of the 12-gene amylovoran biosynthetic operon required for the synthesis, export, and polymerization of amylovoran (34). We used real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) to determine the expression levels of amsG and hrpL at18 h after cells were inoculated into Hrp-inducing minimal medium (Hrp-MM). Our results show no significant differences in the expression levels for hrpL in all of the single-deletion mutants compared to that of the WT, while expression was significantly reduced in the double mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeAB and Ea1189 ΔpdeBC, and further reduced in Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and Ea1189 ΔpdeABC (Fig. 7A). Ea1189 ΔedcA ΔpdeA, Ea1189 ΔedcA ΔpdeB, and Ea1189 ΔedcA ΔpdeC did not show any differences in hrpL expression levels from those detected in the WT Ea1189 strain. amsG expression was significantly elevated in all of the single-gene Δpde mutants and in the double mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeAB and Ea1189 ΔpdeBC, and it was further elevated in Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and Ea1189 ΔpdeABC (Fig. 7B). However, Ea1189 ΔedcA did not show any change in amsG expression compared to that of the WT Ea1189. The edcA pde double mutants all showed an increase in amsG expression levels compared to that of WT Ea1189 but were not different compared to any of the single-gene pde mutants.

FIG 7.

(A) hrpL expression levels 18 hpi in Hrp-MM in WT E. amylovora Ea1189, pde and edcA mutant strains, and complemented mutants. Gene expression levels for the mutants and complemented strains are normalized relative to expression levels recorded in Ea1189. (B) amsG expression levels 18 hpi in MBMA medium in WT E. amylovora Ea1189, pde and edcA mutant strains, and complemented mutants. Gene expression levels for the mutants and complemented strains are normalized relative to expression levels recorded in Ea1189. For both panels A and B, data represent three biological replicates, and error bars represent standard error of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Tukey’s HSD test).

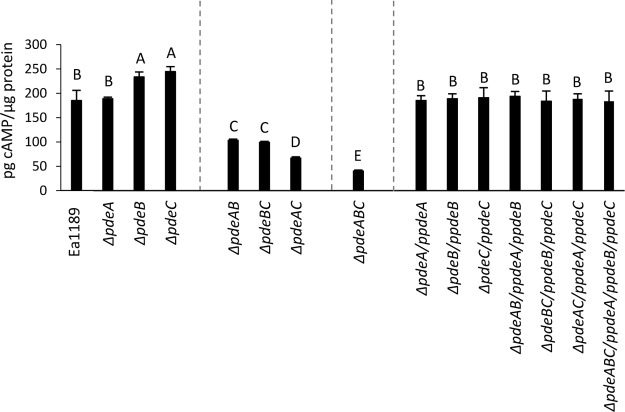

Translocation of the type III effector DspE in Δpde mutants.

Translocation of the effector DspE was examined by using an assay in which the N-terminal portion of DspE, required for translocation by the T3SS (35), was fused to the reporter domain CyaA. Translocation of DspE1-737-CyaA into the model plant host Nicotianatabacum was quantified and compared between the WT Ea1189 and the set of pde mutants. Translocation was measured by quantifying levels of cAMP produced by inoculated N. tabacum as a proxy of CyaA activity. Results indicated that there was no significant difference between Ea1189 ΔpdeA and WT Ea1189 and that there was significantly increased cAMP produced by the other single-deletion mutants, Ea1189 ΔpdeB and Ea1189 ΔpdeC (Fig. 8). Significant decreases in DspE1-737-CyaA translocation were observed in the double mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeAB and Ea1189 ΔpdeBC, and a further reduction was observed in Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and Ea1189 ΔpdeABC (Fig. 8). Complementation of all of the mutants with their respective pde gene(s) resulted in restoration of translocation to WT levels (Fig. 8).

FIG 8.

Translocation levels of type III effector protein DspE for WT E. amylovora Ea1189, pde mutant strains, and complemented mutants (letters represent respective pde genes) measured in a tobacco model using a DspE-CyaA colorimetric assay. Data represent three biological replicates, and error bars represent standard error of the means. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05 by Tukey’s HSD test).

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that PdeA, PdeB, and PdeC are the three active phosphodiesterases in E. amylovora, and that the activity of PdeC has the highest impact on the pool of c-di-GMP in a WT Ea1189 cell. Mutational inactivation of two PDE enzymes in all combinations led to an increase in the intracellular levels of c-di-GMP, with the highest levels of c-di-GMP being observed in the ΔpdeAC double mutant. Primarily, this suggests the presence of functional redundancy among the three Pde enzymes. Mutation of all three pde genes in combination led to the highest increase in c-di-GMP levels in the cell. This indicates that, despite the functional redundancy, PdeA and PdeC are the most important and enzymatically active phosphodiesterases in E. amylovora under the conditions examined here. Deletion of edcA did not result in any measurable impact on c-di-GMP levels in the cell. In addition, the deletion of edcA along with one of the other pde genes did not result in increased intracellular c-di-GMP compared to the pde single mutants. Therefore, our data indicate that edcA is not a PDE in E. amylovora. PDEs respond to a wide range of specific stimuli and can be functional in localized areas within the cell (36, 37). The experimental conditions under which we evaluated c-di-GMP levels might restrict the expression and/or enzymatic activity of PdeA and PdeB, thus not resulting in a measurable impact on c-di-GMP levels in the cell under these conditions, whereas these enzymes might have more significant contributions in other environments. Nevertheless, our observation that the triple pde mutant had the highest levels of c-di-GMP and the most drastic change in the measured phenotypes implicates a functional role for each of the three PDEs in E. amylovora despite inherent differences in their enzymatic activity.

Our results indicate that the regulation of flagellar motility by c-di-GMP in E. amylovora relies on a significant quantitative increase in c-di-GMP levels within the cell. All three pde single mutants and the edcA mutant displayed no change in swimming motility, not even Ea1189 ΔpdeC, which produced an increased level of intracellular c-di-GMP. In contrast, all three pde double mutants and the triple mutant showed drastic reductions in swimming motility. It must be noted, however, that flagellar motility for all strains were examined under conditions that were different from those in which c-di-GMP was quantified. Flagellar motility plays an important role in the E. amylovora infection process that occurs via floral stigmas (38, 39). However, E. amylovora is apparently nonmotile in the apoplast (40) although increased flagellar motility was shown to correlate with virulence in E. amylovora (41). We concluded that the pde double and triple mutants we constructed reached the threshold of c-di-GMP required to impact motility. It is also possible that one or more of the PDEs might have localized action in degrading c-di-GMP in proximity to the flagellar regulatory proteins, a likely possibility, since all PDEs have transmembrane domains predicted (42). Moreover, as c-di-GMP levels were determined from planktonic cultures, it is possible that the pde genes have different impacts on the overall intracellular c-di-GMP under the conditions of the motility assay. This might help explain the lack of change in motility in Ea1189 ΔpdeC despite an increase in overall c-di-GMP levels.

Amylovoran production was strongly regulated by c-di-GMP. Amylovoran is the most important EPS in E. amylovora, is required for pathogenicity, and is critical for biofilm formation and ooze development (4, 7, 32, 34, 43). All three PDEs were involved in negatively regulating amylovoran synthesis, and amsG expression was elevated in all of the mutants, with high-level expression observed in Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and Ea1189 ΔpdeABC. Although the level of necrosis in the immature pear model was similar for WT and the three pde single mutants, the mutants consistently displayed larger ooze droplets. These results suggest that all three PDEs contribute to the negative regulation of amylovoran production during infection.

In addition to the increased amylovoran production in all of the pde mutants, biofilm formation in vitro was also significantly greater in all of the pde single mutants. The pde double mutants displayed even greater biofilm formation than the single mutants. Amylovoran levels were highest in the mutants Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and Ea1189 ΔpdeABC; however, these mutants, although increased in biofilm formation compared to the WT, showed a significant decrease compared to the other two pde double mutant strains. We attribute this loss of ability to form biofilms in Ea1189 ΔpdeAC and Ea1189 ΔpdeABC to an autoaggregation phenotype that was displayed by these mutants when grown in a liquid medium (R. R. Kharadi and G.W. Sundin, unpublished data). The aggregative phenotype presumably negatively impacts the ability of these strains to form a biofilm on a solid surface suspended in liquid medium. Similar to many other xylem-colonizing plant pathogens, such as Pantoea stewartii, Xylella fastidiosa, and Ralstonia solanacearum, E. amylovora forms extensive biofilms within plant xylem vessels, leading to the plugging of the xylem and an inhibition of water transport (7, 44–47). Thus, biofilm formation is an indispensable virulence strategy for E. amylovora. Our results indicate that biofilm formation is under the strong regulation of c-di-GMP and is regulated by all three PDEs, indicating the importance of c-di-GMP degradation and control by phosphodiesterases during pathogenesis.

Virulence in planta involves a complex coordination of the T3SS, motility, amylovoran production, and biofilm formation in E. amylovora. While the T3SS is important during the initial stages of infection, biofilm formation and amylovoran production help the pathogen successfully colonize the xylem and increase population size within the host. An increase in the intracellular levels of c-di-GMP is critical to ensure a successful transitioning of the pathogen to attach and form biofilms (6, 7). However, overproduction of c-di-GMP was detrimental to virulence and to ooze formation during infection of immature pears. This is most likely due to the negative effect of elevated c-di-GMP on the T3SS, resulting in an overall decrease in bacterial population size during infection, which is ultimately visualized as a decrease in lesion size and ooze formation. Thus, the activity of PDEs in degrading c-di-GMP is critical during the orchestration of pathogenesis in E. amylovora. The environmental signaling that triggers PDE activity is currently unknown; however, the presence of transmembrane and external domains in these enzymes suggests that PdeA, PdeB, and PdeC are all capable of responding to external stimuli that regulate their function.

To better correlate phenotypic measures of virulence to T3SS gene expression, we evaluated the gene expression levels of hrpL under T3SS conditions in HRP-MM. HrpL is the alternate sigma factor responsible for the transcriptional regulation of the T3SS structural gene. C-di-GMP has also been shown to suppress T3SS in other bacteria, including Dickeya dadantii and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (17, 29). We found that hrpL expression was largely unaffected in the pde single mutants, whereas upon an increase in c-di-GMP in the double and triple mutants, hrpL expression was reduced significantly. Likewise, the translocation of the type III effector DspE was only negatively affected in the double or triple pde mutants. Even though PdeC alone could affect intracellular levels of c-di-GMP, the requirement of two PDEs to affect T3SS gene expression and effector translocation suggests that individual PDEs are impacting distinct pools of c-di-GMP that collectively impact the function of the T3SS.

In summary, we found that E. amylovora encodes three active phosphodiesterase enzymes, PdeA, PdeB, and PdeC, with PdeC being the most enzymatically active. Although EdcA contains an EAL domain, based on evidence from previous research and our own, we conclude that EdcA is not a PDE, nor does it regulate amylovoran production, motility, or virulence. However, this enzyme does regulate biofilm formation independently of these factors via an unknown mechanism. Amylovoran production and biofilm formation are strongly regulated by all three PDE enzymes. Elevated levels of c-di-GMP conferred by the deletion of two or more pde genes led to an increase in amylovoran production and biofilm formation. Increased levels of c-di-GMP, as observed in the double and triple mutants, led to a downregulation of flagellar motility and virulence in terms of hrpL expression and the translocation of the effector DpsE. In order to fully understand the specific functions of the individual Pde enzymes, studying the target-specific transcriptional regulation mediated by c-di-GMP in E. amylovora will be critical.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study and their relevant characteristics are listed in Table 1. All E. amylovora strains and Escherichia coli strains used in this study were grown routinely in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and agar medium at 28°C and 37°C, respectively. Amylovoran quantification assays were conducted in modified basal medium A (MBMA) (20) amended with 1% sorbitol. For biofilm formation assays, the wild type (WT) and mutant strains were grown in 0.5× LB medium. Media were amended with the following antibiotics as needed: ampicillin (Ap; 100 µg/ml), chloramphenicol (Cm; 10 µg/ml), gentamicin (Gm; 10 µg/ml), kanamycin (Km; 100 µg/ml) or tetracycline (Tc; 10 µg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study and their relevant characteristics

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. amylovora strains | ||

| Ea1189 | Wild type | 8 |

| Ea1189 Δams | Deletion of the ams amylovoran biosynthetic operon | 11 |

| Ea1189 ΔpdeA | Deletion of EAM_RS10800 (pdeA) | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔpdeB | Deletion of EAM_RS16275 (pdeB) | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔpdeC | Deletion of EAM_RS16620 (pdeC) | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔedcA | Deletion of EAM_RS01725 (edcA) | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔpdeAC | pdeA and pdeC deletion mutant | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔpdeAB | pdeA and pdeB deletion mutant | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔpdeBC | pdeB and pdeC deletion mutant | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔpdeABC | pdeA, pdeB, and pdeC deletion mutant | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔedcA ΔpdeA | edcA and pdeA deletion mutant | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔedcA ΔpdeB | edcA and pdeB deletion mutant | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔedcA ΔpdeC | edcA and pdeC deletion mutant | This study |

| Ea1189 ΔflhC | flhC deletion mutant; Kmr | 11 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKD3 | Cmr cassette flanking FRT sites; Cmr | 53 |

| pKD46 | L-Arabinose-inducible lambda red recombinase; Apr | 53 |

| pTL18 | IPTG-inducible FLP; Tetr | 59 |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | Broad-host-range cloning vector; R6K ori; Gmr | 60 |

| pLRT201 | pMJH20 expressing DspE(1-737) – CyaA; Apr | 57 |

| pACYCDuet-1 | Expression vector containing two MCS: P15A ori; Cmr | Novagen (Darmstadt, Germany) |

| pRRK01 | pdeA with native promoter in pBBR1MCS-5; Gmr | This study |

| pRRK02 | pdeB with native promoter in pBBR1MCS-5; Gmr | This study |

| pRRK03 | pdeC with native promoter in pBBR1MCS-5; Gmr | This study |

| pRRK04 | pdeA and pdeB with their respective native promoters in pACYCDuet-1; Cmr | This study |

| pRRK05 | pdeB and pdeC with their respective native promoters in pACYCDuet-1; Cmr | This study |

| pRRK06 | pdeA and pdeC with their respective native promoters in pACYCDuet-1; Cmr | This study |

| pRRK07 | edcA with native promoter in pBBR1MCS-5; Gmr | This study |

| pRRK08 | edcA and pdeA with their respective native promoters in pACYCDuet-1; Cmr | This study |

| pRRK09 | edcA and pdeB with their respective native promoters in pACYCDuet-1; Cmr | This study |

| pRRK10 | edcA and pdeC with their respective native promoters in pACYCDuet-1; Cmr | This study |

IPTG, isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside; FRT, flippase target recognition; MCS, multiple cloning site.

Bioinformatics.

The Motif Alignment and Search Tool (MAST) version 4.11.1 (48) was used to search for open reading frames (ORFs) in E. amylovora that contained EAL domains. The arrangement of the conserved protein domains was predicted using the Pfam tool version 29.0 (49). DNA sequence and protein alignment were done using the MEGA version 7.0 program (50). Transmembrane helices in the proteins were predicted using TMHMM version 2.0 (42). Artemis (Java) was used to browse the annotated E. amylovora genome and to acquire graphical representations and sequences of genes.

Genetic manipulations and analyses.

DNA manipulations were performed using standard techniques and protocols (51). The genome sequence of E. amylovora ATCC 49946 (52) was obtained from GenBank (accession no. FN666575), and used to determine sequences of oligonucleotide primers used for the construction of mutants and complementation clones (Table 2). Chromosomal deletion mutants in E. amylovora WT Ea1189 were constructed using the lambda red recombinase protocol described previously (11, 53). The pde and edcA single-deletion mutants were complemented with their respective genes and native promoter sequences ligated into pBBR1MCS-5. The double mutants of pde and edcA genes were complemented with both of the respective pde and edcA genes and native promoter sequences ligated into pACYCDuet-1. The ΔpdeABC mutant was complemented with a combination of the pdeC gene in pBBR1MCS-5 and the pdeA and pdeB genes in pACYCDuet-1.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| Primers used to make 1.1-kb DNA segments for construction of deletion mutants | |

| pdeA.fw | ATGCCATTATCTACCACCGTCAGACGGCATGTTATCCAGCCGCGCAGAGTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| pdeA.rv | TCATCTGCTTGGCACGCGCGAAATGTCCGTGTCAGCGCAATCCAAAGCAGCATATGAATATCCTCCTTA |

| pdeB.fw | TTGCAAGCATTTGTAAAGCCGAAGCATGAACGTATCTGGCTGGTGGCATCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| pdeB.rv | CTAAGCATTCTGCTGATCTTTCCACTGCATCAGCGCAGCGCTCGACATGGCATATGAATATCCTCCTTA |

| pdeC.fw | TTGCGCGTCAGCCGTTCATTAAAGATTAAGCAAATGGCGACCATTTCCAGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| pdeC.rv | TCAGTAACTGGCCAGATAGCGCTGATTAAACTGCGCCAGCGGCAGCGCTCCATATGAATATCCTCCTTA |

| edcA.fw | ATGATGTTACTGACCAGCGTGCGGCGGATGCGCGCATCCATCATATGGCGCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| edcA.rv | GATGATCTCTCGATGCTGGTTGTTGGTGATCGGCTGGTAATAGAGCTTCAGCTGGCGGTACATATGAATATCCTCCTTA |

| Primers flanking target genes by 500 bp, used to confirm deletions | |

| CpdeA.fw | TTATCTACCACCGTCAGACG |

| CpdeA.rv | TGTCAGCGCAATCCAAAG |

| CpdeB.fw | ATGAACGTATCTGGCTGGT |

| CpdeB.rv | CATTCTGCTGATCTTTCCAC |

| CpdeC.fw | TCAGCCGTTCATTAAAGATT |

| CpdeC.rv | CCAGATAGCGCTGATTAAA |

| CedcA.fw | ATGATGTTACTGACCAGCGTG |

| CedcA.rv | GATGATCTCTCGATGCTGGTTG |

| Primers used to construct complementation vectors | |

| pdeA pBBR1.fw | AACTCGAGCTGTCTTCGATGTTGATGTCC |

| pdeA pBBR1.rv | AATCTAGATCATATAAAATGTGTTGCTCGG |

| pdeB pBBR1.fw | AACTCGAGTCAAATTGAGGCCGC |

| pdeB pBBR1.rv | ATTCTAGACCAATACAGCACGGCAG |

| pdeC pBBR1.fw | AACTCGAGAGATAACGCGAAAGTAACACCTGACTAA |

| pdeC pBBR1.rv | AATCTAGAGGCTCTGTTCACCTGCCGATC |

| edcA pBBR1.fw | ATTACACTCGAGAGAACGACGGCAATCC |

| edcA pBBR1.rv | TCTGAATCTAGACATTAACATCCACCGCAG |

| pdeA pACYC.fw | AAAAGGATCCCTGTCTTCGATGTTGATGTCC |

| pdeA pACYC.rv | AAAAAAGCTTTCATATAAAATGTGTTGCTCGG |

| pdeB pACYC.fw | AAAAGATATCTCAAATTGAGGCCGC |

| pdeB pACYC.rv | AAAAGGTACCCCAATACAGCACGGCAG |

| pdeC pACYCsite1.fw | AAAAGGATCCAGATAACGCGAAAGTAACACCTGACTAA |

| pdeC pACYCsite1.rv | AAAAAAGCTTGGCTCTGTTCACCTGCCGATC |

| pdeC pACYCsite2.fw | AAAAGATATCAGATAACGCGAAAGTAACACCTGACTAA |

| pdeC pACYCsite2.rv | AAAAGGTACCGGCTCTGTTCACCTGCCGATC |

| edcA pACYCsite2.fw | AAAAGATATCAATCATGAATGAAGACTCAGATGTTGTGTACCAG |

| edcA pACYCsite2.rv | AAAAGGTACCGACTGTTACCGGTAACAATAGCTATATTGTAACAGTATG |

Intracellular c-di-GMP concentration quantification.

Intracellular levels of c-di-GMP were quantified using ultraperformance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS), as described previously (54). Overnight cultures were diluted 1:30 and grown until they reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8 to 1.0 and then normalized to an OD600 of 0.7, 5 ml of this new culture was pelleted, and the supernatant was discarded. The pelleted cells were treated with 100 µl of an extraction buffer solution (40% acetonitrile and 40% methanol) and incubated for 15 min at −20°C, after which 10 µl of supernatant was analyzed by UPLC-MS/MS on a Quattro Premier XE instrument. All samples were quantified by comparison against a standard curve generated by using chemically synthesized c-di-GMP (Axxora Life Sciences Inc., San Diego, CA). This assay was repeated three times, with three technical replicates in each experiment.

Swimming motility assay.

Swimming motility was assessed with a motility assay, as previously described (55). Cells from an overnight culture were pelleted, washed and resuspended in 0.5× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to an OD600 of 0.5, and 5 µl of this diluted culture was spotted at the center of a swimming motility plate (10 g tryptone, 5 g NaCl, and 3 g agar per liter), followed by incubation at 28°C for 48 h. The plates were photographed under white light using a Red imaging system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA), and photographs were analyzed using ImageJ (56) software. Motility was quantified in terms of the area (mm2) of bacterial growth on the plate. Ea1189 ΔflhC was used as a negative control in these experiments. This assay was repeated three times.

Quantification of amylovoran production and biofilm formation.

Amylovoran production by E. amylovora Ea1189 and mutant strains was quantified using the cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC)-binding turbidimetric assay, as previously described (43). Ea1189 Δams was used as a negative control in this assay. The OD600 of the CPC-bound suspension was normalized using the OD600 of the corresponding culture. This assay was repeated at least three times, with three technical replicates in each experiment. Biofilm formation was quantified on glass coverslips in vitro using a crystal violet assay as previously described (7). Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.5, and 150 µl of this diluted culture was added to a 24-well polystyrene microtiter plate containing 1.5 ml of 0.5× LB medium in each of the wells, along with a glass coverslip placed at a ≈30° angle. The cultures were incubated at 28°C for 48 h without shaking, after which the planktonic cells were removed, and the coverslips were stained for 1 h in a 0.3% crystal violet (CV) solution. The stained coverslips were rinsed with water and air dried. Each of the coverslips was then washed with 200 µl of elution solution (40% methanol and 10% glacial acetic acid), and the OD595 of this elution was measured. This assay was repeated at least three times, with three technical replicates in each experiment.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR.

Bacterial cells from an overnight culture were washed and resuspended in Hrp-inducing minimal medium (Hrp-MM; used to mimic conditions of the plant apoplast in vitro) to measure hrpL expression (35) or MBMA medium to measure amsG expression (43), followed by incubation at 16°C for 18 h. RNA from cultures was extracted using the RNeasy minikit method (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and treated with Turbo DNA-free DNase (Ambion, Austin, TX). cDNA was synthesized using TaqMan reverse transcription (RT) reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative PCRs were conducted using SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). recA was used as an endogenous control for data analysis. These experiments were repeated at least twice.

DspE-CyaA translocation assay.

To determine the level of translocation of the type III effector DspE to plant cells, the DspE-CyaA assay was conducted, as previously described (57). Mutant and WT strains containing the DspE(1-737)-CyaA fusion plasmid pLRT201 were cultured overnight, washed, and readjusted to a concentration of 6 × 108 CFU/ml. The cell suspension was then infiltrated into three separate, fully expanded leaves of Nicotiana tabacum. Samples were collected 8 h postinoculation (hpi), using a 1-cm diameter cork borer, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Protein extraction was done from the samples using 0.1 M HCl. cAMP levels were then quantified using a cyclic AMP enzyme immunoassay kit (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI). Total protein levels in the samples were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Hercules, CA). The levels of cAMP were then normalized to the amount of protein present in the samples (pg cAMP/µg protein).

Virulence assays.

Virulence assays were conducted on immature pear fruit (Pyrus communis cv. Bartlett), as previously described (58). Bacteria were inoculated on stab-wounded immature pears at a concentration of 104 CFU/ml, followed by an incubation at 28°C. Data were collected from immature pears in the form of necrotic lesion diameters, bacterial population counts within emerged ooze droplets and within the tissue, volume of ooze droplets, and amylovoran content in the ooze droplets. The amylovoran content was assessed by dissolving the ooze droplets from infected pears in MBMA medium, followed by the incubation of 50 µl of CPC (25 mg/ml) with the supernatant for 10 min. The OD600 of the suspension was measured and used as a relative measure of the abundance of amylovoran in the ooze droplets. Bacterial population counts in diseased pear tissue were determined using a 1-cm3 block of pear tissue cut around the site of inoculation, including any ooze present at the area of sampling. In a separate experiment, the bacterial population in the ooze droplet at the site of infection was also quantified. Virulence assays on apple trees (Malus x domestica cv. Gala) were conducted by cutting young leaves with scissors dipped in bacterial inoculum (OD600 = 0.1) between two adjacent veins emerging from the midrib (41). Following this, shoot blight was measured regularly as infection progressed. All virulence assays were repeated at least twice, with a minimum of three technical replicates per treatment in each experiment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program grant 2015-67013-23068 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and by Michigan State University AgBioResearch. R.R.K. is a Michigan State University Plant Science Initiative graduate fellow.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02233-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Norelli JL, Jones AL, Aldwinckle HS. 2003. Fire blight management in the twenty-first century. Plant Dis 87:756–765. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.7.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson SV. 1986. The role of the stigma in fire blight infections. Phytopathology 76:476–482. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-76-476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van der Zwet T, Beer SV. 1995. Fire blight—its nature, prevention, and control. A practical guide to integrated disease management. USDA agriculture information bulletin no. 631. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eden-Green SJ, Knee M. 1974. Bacterial polysaccharide and sorbitol in fireblight exudate. J Gen Microbiol 81:509–512. doi: 10.1099/00221287-81-2-509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slack SM, Zeng Q, Outwater CA, Sundin GW. 2017. Microbiological examination of Erwinia amylovora exopolysaccharide ooze. Phytopathology 107:403–411. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-16-0352-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malnoy M, Martens S, Norelli JL, Barny MA, Sundin GW, Smits TH, Duffy B. 2012. Fire blight: applied genomic insights of the pathogen and host. Annu Rev Phytopathol 50:475–494. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-172931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koczan JM, McGrath MJ, Zhao Y, Sundin GW. 2009. Contribution of Erwinia amylovora exopolysaccharides amylovoran and levan to biofilm formation: implications in pathogenicity. Phytopathology 99:1237–1244. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-99-11-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castiblanco LF, Sundin GW. 2018. Cellulose production, activated by cyclic-di-GMP through BcsA and BcsZ, is a virulence factor and an essential determinant of the three-dimensional architectures of biofilms formed by Erwinia amylovora Ea1189. Mol Plant Pathol 19:90–103. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santander RD, Biosca EG. 2017. Erwinia amylovora psychrotrophic adaptations: evidence of pathogenic potential and survival at temperate and low environmental temperatures. PeerJ 5:e3931. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billing E. 2011. Fire blight. Why do views on host invasion by Erwinia amylovora differ? Plant Pathol 60:178–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02382.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y, Sundin GW, Wang D. 2009. Construction and analysis of pathogenicity island deletion mutants of Erwinia amylovora. Can J Microbiol 55:457–464. doi: 10.1139/w08-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh CS, Beer SV. 2005. Molecular genetics of Erwinia amylovora involved in the development of fire blight. FEMS Microbiol Lett 253:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNally RR, Toth IK, Cock PJ, Pritchard L, Hedley PE, Morris JA, Zhao Y, Sundin GW. 2012. Genetic characterization of the HrpL regulon of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora reveals novel virulence factors. Mol Plant Pathol 13:160–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei ZM, Beer SV. 1995. hrpL activates Erwinia amylovora hrp gene transcription and is a member of the ECF subfamily of sigma factors. J Bacteriol 177:6201–6210. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6201-6210.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ancona V, Li W, Zhao Y. 2014. Alternative sigma factor RpoN and its modulation protein YhbH are indispensable for Erwinia amylovora virulence. Mol Plant Pathol 15:58–66. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JH, Zhao Y. 2015. Integration host factor is required for RpoN-dependent hrpL gene expression and controls motility by positively regulating rsmB sRNA in Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 106:29–36. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-07-15-0170-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad I, Lamprokostopoulou A, Le Guyon S, Streck E, Barthel M, Peters V, Hardt WD, Römling U. 2011. Complex c-di-GMP signaling networks mediate transition between virulence properties and biofilm formation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. PLoS One 6:e28351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuchma SL, Connolly JP, O'Toole GA. 2005. A three-component regulatory system regulates biofilm maturation and type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 187:1441–1454. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1441-1454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Römling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. 2013. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edmunds AC, Castiblanco LF, Sundin GW, Waters CM. 2013. Cyclic di-GMP modulates the disease progression of Erwinia amylovora. J Bacteriol 195:2155–2165. doi: 10.1128/JB.02068-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hengge R. 2009. Principles of c-di-GMP signaling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenal U, Reinders A, Lori C. 2017. Cyclic di-GMP: second messenger extraordinaire. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:271–284. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feirer N, Xu J, Allen KD, Koestler BJ, Bruger EL, Waters CM, White RH, Fuqua C. 2015. A pterin-dependent signaling pathway regulates a dual-function diguanylate cyclase-phosphodiesterase controlling surface attachment in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. mBio 6:e00156-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00156-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aragón IM, Pérez‐Mendoza D, Gallegos MT, Ramos C. 2015. The c‐di‐GMP phosphodiesterase BifA is involved in the virulence of bacteria from the Pseudomonas syringae complex. Mol Plant Pathol 16:604–615. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan RP, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Jiang BL, He YQ, Feng JX, Tang JL, Dow JM. 2007. Cyclic di-GMP signalling in the virulence and environmental adaptation of Xanthomonas campestris. Mol Microbiol 63:429–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chatterjee S, Killiny N, Almeida RP, Lindow SE. 2010. Role of cyclic di-GMP in Xylella fastidiosa biofilm formation, plant virulence, and insect transmission. Mol Plant Microb Interact 23:1356–1363. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-10-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adeolu M, Alnajar S, Naushad S, Gupta RS. 2016. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: proposal for Enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morganellaceae fam. nov., and Budviciaceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:5575–5599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan H, West JA, Ramsay JP, Monson RE, Griffin JL, Toth IK, Salmond GPC. 2014. Comprehensive overexpression analysis of cyclic-di-GMP signaling proteins in the phytopathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum reveals diverse effects on motility and virulence phenotypes. Microbiology 160:1427–1439. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.076828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yi X, Yamazaki A, Biddle E, Zeng Q, Yang CH. 2010. Genetic analysis of two phosphodiesterases reveals cyclic diguanylate regulation of virulence factors in Dickeya dadantii. Mol Microbiol 77:787–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hengge R, Gründling A, Jenal U, Ryan R, Yildiz F. 2016. Bacterial signal transduction by cyclic di-GMP and other nucleotide second messengers. J Bacteriol 198:15–26. doi: 10.1128/JB.00331-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aravind L, Ponting CP. 1999. The cytoplasmic helical linker domain of receptor histidine kinase and methyl-accepting proteins is common to many prokaryotic signaling proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett 176:111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett RA, Billing E. 1978. Capsulation and virulence in Erwinia amylovora. Ann Appl Biol 89:41–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1978.tb02565.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei Z, Kim JF, Beer SV. 2000. Regulation of hrp genes and type III protein secretion in Erwinia amylovora by HrpX/HrpY, a novel two-component system, and HrpS. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13:1251–1262. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.11.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernhard F, Coplin DL, Geider K. 1993. A gene cluster for amylovoran synthesis in Erwinia amylovora: characterization and relationship to cps genes in Erwinia stewartii. Mol Gen Genet 239:158–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huynh TV, Dahlbeck D, Staskawicz BJ. 1989. Bacterial blight of soybean: regulation of a pathogen gene determing host cultivar specificity. Science 245:1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Römling U, Liang ZX, Dow JM. 2017. Progress in understanding the molecular basis underlying functional diversification of cyclic dinucleotide turnover proteins. J Bacteriol 199:e00790-16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00790-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt AJ, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. 2005. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J Bacteriol 187:4774–4781. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4774-4781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bayot RG, Ries SM. 1986. Role of motility in apple blossom infection by Erwinia amylovora and studies of fire blight control with attractant and repellent compounds. Phytopathology 76:441–455. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-76-441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raymundo AK, Ries SM. 1981. Motility of Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 71:45–49. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-71-45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cesbron S, Paulin JP, Tharaud M, Barny MA, Brisset MN. 2006. The alternative σ factor HrpL negatively modulates the flagellar system in the phytopathogenic bacterium Erwinia amylovora under hrp-inducing conditions. FEMS Microbiol Lett 257:221–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D, Korban SS, Zhao Y. 2010. Molecular signature of differential virulence in natural isolates of Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 100:192–198. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-100-2-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellemann P, Bereswill S, Berger S, Geider K. 1994. Visualization of capsule formation by Erwinia amylovora and assays to determine amylovoran synthesis. Int J Biol Macromol 16:290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koczan JM, Lenneman BR, McGrath MJ, Sundin GW. 2011. Cell surface attachment structures contribute to biofilm formation and xylem colonization by Erwinia amylovora. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:7031–7039. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05138-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koutsoudis MD, Tsaltas D, Minogue TD, von Bodman SB. 2006. Quorum-sensing regulation governs bacterial adhesion, biofilm development, and host colonization in Pantoea stewartii subspecies stewartii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:5983–5988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509860103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feil H, Feil WS, Detter JC, Purcel AH, Lindow SE. 2003. Site-directed disruption of the fimA and fimF fimbrial genes of Xylella fastidiosa. Phytopathology 93:675–682. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tran TM, MacIntyre A, Hawes M, Allen C. 2016. Escaping underground nets: extracellular DNases degrade plant extracellular traps and contribute to virulence of the plant pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005686. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bailey TL, Gribskov M. 1998. Methods and statistics for combining motif match scores. J Comput Biol 5:211–221. doi: 10.1089/cmb.1998.5.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finn RD, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Mistry J, Mitchell AL, Potter SC, Punta M, Qureshi M, Sangrador-Vegas A, Salazar GA. 2016. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res 44:279–285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. In vitro mutagenesis using double-stranded DNA templates: selection of mutants with DpnI, p 13–19. In Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sebaihia M, Bocsanczy AM, Biehl BS, Quail MA, Perna NT, Glasner JD, DeClerck GA, Cartinhour S, Schneider DJ, Bentley SD, Parkhill J. 2010. Complete genome sequence of the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora strain ATCC 49946. J Bacteriol 192:2020–2021. doi: 10.1128/JB.00022-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Massie JP, Reynolds EL, Koestler BJ, Cong JP, Agostoni M, Waters CM. 2012. Quantification of high-specificity cyclic diguanylate signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:12746–12751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115663109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeng Q, McNally RR, Sundin GW. 2013. Global small RNA chaperone Hfq and regulatory small RNAs are important virulence regulators in Erwinia amylovora. J Bacteriol 195:1706–1717. doi: 10.1128/JB.02056-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9:671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Triplett LR, Melotto M, Sundin GW. 2009. Functional analysis of the N terminus of the Erwinia amylovora secreted effector DspA/E reveals features required for secretion, translocation, and binding to the chaperone DspB/F. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22:1282–1292. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-10-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao Y, He SY, Sundin GW. 2006. The Erwinia amylovora avrRpt2EA gene contributes to virulence on pear and AvrRpt2EA is recognized by Arabidopsis RPS2 when expressed in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19:644–654. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Long T, Tu KC, Wang YF, Mehta P, Ong NP, Bassler BL, Wingreen NS. 2009. Quantifying the integration of quorum-sensing signals with single cell resolution. PLoS Biol 7:e68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM II, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.