Abstract

Natriuretic peptides (NPs) exert diverse effects on several biological and physiological systems, such as kidney function, neural and endocrine signaling, energy metabolism, and cardiovascular function, playing pivotal roles in the regulation of blood pressure (BP) and cardiac and vascular homeostasis. NPs are collectively known as anti-hypertensive hormones and their main functions are directed toward eliciting natriuretic/diuretic, vasorelaxant, anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-hypertrophic effects, thereby, regulating the fluid volume, BP, and renal and cardiovascular conditions. Interactions of NPs with their cognate receptors display a central role in all aspects of cellular, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms that govern physiology and pathophysiology of BP and cardiovascular events. Among the NPs atrial and brain natriuretic peptides (ANP and BNP) activate guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A (GC-A/NPRA) and initiate intracellular signaling. The genetic disruption of Npr1 (encoding GC-A/NPRA) in mice exhibits high BP and hypertensive heart disease that is seen in untreated hypertensive subjects, including high BP and heart failure. There has been a surge of interest in the NPs and their receptors and a wealth of information have emerged in the last four decades, including molecular structure, signaling mechanisms, altered phenotypic characterization of transgenic and gene-targeted animal models, and genetic analyses in humans. The major goal of the present review is to emphasize and summarize the critical findings and recent discoveries regarding the molecular and genetic regulation of NPs, physiological metabolic functions, and the signaling of receptor GC-A/NPRA with emphasis on the BP regulation and renal and cardiovascular disorders.

Keywords: cardiovascular hemostasis, cGMP, gene-targeting, hypertension, natriuretic peptide receptor, receptor signaling

INTRODUCTION

Almost 37 yr ago, the pioneering discovery by de Bold and his colleagues (35) demonstrated that atrial extracts contained natriuretic and diuretic activities, which led them to isolate and characterize “atrial natriuretic factor/peptide (ANF/ANP)” and to establish the field of natriuretic peptides (NPs) hormone family. The NPs are a group of peptide hormones that play important roles in the control of blood pressure (BP) by affecting renal, cardiovascular, neuronal, and endocrine homeostasis (92, 123, 154, 155, 198, 199, 212, 229). ANP has been shown to be present in various organs including heart, brain, kidney, and gonads; however, it is mainly secreted from the cardiac atrium that elicits natriuretic, diuretic, vasorelaxant, antimitogenic, antihypertrophic, and anti-inflammatory effects, all of which are predominantly directed to the reduction of body fluid volume and BP homeostasis (16, 53, 61, 62, 105, 154). Later, two other members of NPs, namely brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP), were identified and characterized with structural properties similar to ANP, but each of them are encoded from a separate gene (177). BNP was isolated and identified from the brain, but largely synthesized in the cardiac ventricles, secreted in the plasma, and exhibits the greater variability in peptide structure. It is considered that CNP is largely synthesized in the endothelial cells of vasculature and to some extent in the central nervous system, which is remarkably conserved between the species. All three NPs contain a ring structure of 17-amino acid residues and joined by a single disulfide-bridge but deviate from each other in the amino- and carboxyl -terminal flanking sequences (123). The primary structure of the ANP precursor derived from the cDNA sequence contained the biologically active peptide sequence in its carboxyl-terminal region and indicated that circulating ANP is a 28-amino acid molecule, which exhibits biological and physiological activities (123).

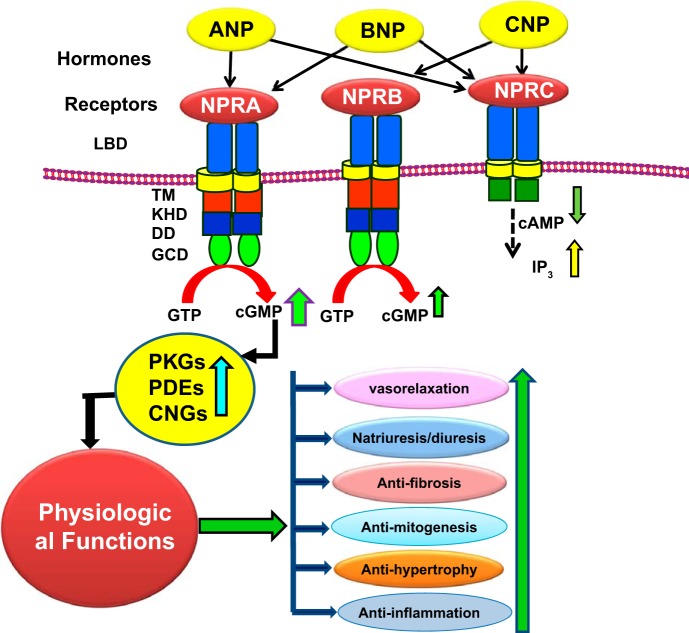

Plasma membrane guanylyl cyclase (GC) represents the biological active form of ANP receptor (NPR), which was cloned and sequenced from rat brain (26, 186), human placenta (20), mouse testis (164), and rat adrenal gland (41). The molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence analyses have identified three types of NPRs (164, 186). The NP receptors with intrinsic GC catalytic activities have been named as natriuretic peptide receptor-A and -receptor B (NPRA and NPRB), also recognized as GC-A/NPRA and GC-B/NPRB, respectively (56, 86, 97, 154, 164, 186). A third NP receptor lacks the GC catalytic domain and has been termed by default as a natriuretic peptide clearance receptor (NPRC), which is considered to clear some of the NPs from the circulation (55, 118). However, the studies using NPRC gene-knockout mice, suggested that NPRC could modulate local effects of NPs, and unexpectedly homozygous null mutant mice (Npr3−/−) exhibited skeletal abnormalities (120). The NPRA is activated by ANP and BNP, while NPRB is activated by CNP, both receptors generate second messenger cGMP, which triggers the biological and physiological functions of NPs (Fig. 1). On the other hand, all NPs (ANP, BNP, and CNP) bind to NPRC, which does not produce cGMP (154). The primary sequence structure of NPRA contains four main regions, including an extracellular ligand-binding region, a single plasma membrane spanning domain, and the cytoplasmic protein kinase-like homology (protein-KHD) and GC catalytic active-site regions (97, 154, 157, 164). The NPRB has overall domain structure like NPRA with the selective binding specificity to CNP (185, 186). NPRC contains a short (35 residues) intracellular cytoplasmic tail, which is devoid of GC domain, apparently not effective to generate cGMP (2, 3, 55, 69). NPRA is the dominant form of the all NP receptors found in most of the peripheral organs including kidneys, adrenal glands, vascular beds, brain, heart, and gonadal tissues (105, 154, 158, 160, 197). The cell and tissue distribution of NPRA, NPRB, and NPRC and their gene-knockout phenotypes is presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Diagrammatic representation of ligand-dependent activation and physiological functions of NPRA, NPRB, and NPRC. ANP-binding activates NPRA, which leads to enhanced production of second messenger cGMP with stimulation and activation of ANP-dependent cellular and physiological responsiveness. CNP activates NPRB, and all three NPs activate NPRC. ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CNP, C-type natriuretic peptide; LBD, ligand binding domain; TM, transmembrane domain; KHD, kinase like homology domain; DD, dimerization domain; GCD, guanylyl cyclase catalytic domain; IP3, inositol trisphosphate.

Table 1.

Disease-specific phenotypes of mice with gene disruption of natriuretic peptides and their specific receptors

| Peptide/Protein Nomenclature | Gene Nomenclature | Gene-disrupted Phenotype in Mouse |

|---|---|---|

| ANP/ANF | Nppa | High blood pressure, salt sensitivity, fibrosis (81, 113, 126, 209) |

| BNP | Nppb | Hypertension, vascular complication, fibrosis (149, 217) |

| CNP | Nppc | Dwarfism, reduced bone growth, impaired endochondral ossification (29, 82, 233, 244) |

| NPRA | Npr1 | Volume overload, high blood pressure, salt sensitivity hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis, inflammation, and reduced testosterone levels (46, 91, 116, 150, 151, 163, 173, 203, 227) |

| NPRB | Npr2 | Seizures, dwarfism, female sterility, decreased adiposity (103, 216) |

| NPRC | Npr3 | Bone deformation with long bone overgrowth (120) |

Nomenclature of peptides/proteins and genes with gene-disrupted phenotypes are indicated in capital letters and italics, respectively. ANP/ANF, atrial natriuretic factor/peptide; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; CNP, C-type natriuretic peptide; Nppa (coding for pro-ANP); Nppb (coding for pro-BNP); Nppc (coding for pro-CNP); NPRA, natriuretic peptide receptor-A; NPRB, natriuretic peptide receptor-B; NPRC, natriuretic peptide receptor-C; Npr1 (coding for NPRA); Npr2, (coding for NPRB); Npr3 (coding for NPRC).

DISRUPTION OF Nppa AND Npr1 TRIGGERS PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF HYPERTENSION AND CARDIOVASCULAR DYSFUNCTION

Hypertension is a heritable quantitative trait, which is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Molecular and genetic approaches have greatly advanced our understanding of the interindividual variations in BP, influenced by polymorphisms in the genomic sequences of Nppa (encoding pro-ANP), Nppb (encoding pro-BNP), and Npr1 (45, 83, 106, 107, 111, 146, 229). Studies with ANP-deficient mice have demonstrated that a decreased level of ANP can cause hypertension (81, 126, 156, 159). The BP of mutant animals was elevated by 8–16 mmHg when they were fed with standard- or intermediate-salt diets. Moreover, mice with overexpression of ANP exhibited ~30 mmHg lower systolic BP (SBP) compared with nontransgenic siblings (96, 126, 209). Somatic delivery of Nppa in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) showed a continuous reduction of SBP (113). Similarly, ANP gene therapy showed a regulatable reduction in BP in hypertensive animals (181). The results of those previous studies provided the concept that ANP gene therapy could be used for the treatment of high BP and related disorders. Genetic studies have revealed that the ablation of Npr1 in mice triggers BP by ~40 mmHg higher as compared with control animals (150, 201, 227). It has been demonstrated that complete absence of NPRA causes hypertension in mice and leads to altered renin and angiotensin II (ANG II) levels, reduced renal function, cardiac hypertrophy, and lethal vascular events similar to untreated hypertensive human subjects (33, 34, 150, 184, 203, 227, 249). In contrast, Npr1 gene duplication in mutant mice showed a significant reduction in BP and produced the intracellular second messenger cGMP, proportionately to the increasing number of Npr1 gene copies (151, 163, 203, 226, 228, 249). Previous studies have demonstrated that plasma and heart tissues of hypertensive heart patients exhibit very high levels of ANP and BNP (23, 51, 173, 222, 236). Studies in humans and experimental animal models have shown that Nppa and Nppb genes are overexpressed during the conditions of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, indicating that autocrine and/or paracrine signaling might be involved in the cardiac protective effects (46, 51, 72, 95, 226, 227, 242).

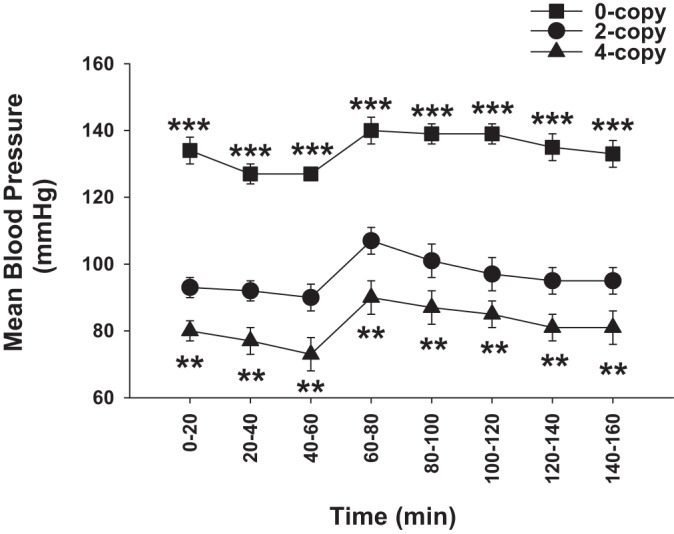

NPRA Regulates Volume Overload, Sodium Excretion, and BP

The previous studies have examined the specific contribution of NPRA in mediating the signaling mechanisms responsible for natriuretic and diuretic responses to nondilutional intravascular volume expansion (203). In wild-type (2-copy; Npr1+/+) and Npr1 gene-duplicated (4-copy; Npr1++/++) animals, the excretion of Na+ and urine flow were proportionately associated with increases in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), but the SBP was not significantly increased. The homozygous null mutant (0-copy; Npr1−/−) mice exhibited the highest SBP, whereas the gene-duplicated 4-copy mice showed the lowest SBP compared with wild-type mice (203). During the volume expansion period, the mean arterial BP was increased in all three animal genotypes (0-copy, 2-copy, and 4-copy), but it remained significantly lower in gene-duplicated 4-copy mice and was greatly higher in 0-copy null mutant mice compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 2). The renal hemodynamic parameters, including GFR and renal plasma flow (RPF), were significantly lower in Npr1−/− mice and higher in Npr1++/++ mice compared with Npr1+/+ animals (33, 203). The urinary cGMP concentrations were significantly reduced in 0-copy mice but greatly increased in 4-copy mice compared with 2-copy animals during the entire period of volume expansion. It is remarkable to note that Npr1++/++ mice exhibited significantly higher GFR values and cGMP concentrations compared with significantly lower responses to the volume expansion in Npr1−/− mutant mice (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of volume expansion on mean blood pressures in Npr1 homozygous mutant and gene-duplicated mice. Mean blood pressures by cannulated carotid arterial methods were continuously recorded for 160 min throughout the duration of the experiment. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. The figure has been reproduced and adapted with permission from Shi et al. (203).

Table 2.

Effect of volume expansion on glomerular filtration rate in Npr1 gene-targeted mice

| GFR, ml·min−1·g kidney weight−1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Before VE | VE | After VE |

| 0-Copy | 0.49 + 0.03* | 0.58 + 0.04† | 0.49 + 0.05* |

| 2-Copy | 0.63 + 0.03 | 0.82 + 0.09 | 0.68 + 0.06 |

| 4-Copy | 0.81 + 0.04 | 1.19 + 0.12† | 0.87 + 0.08* |

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was determined before, during, and after pure blood volume expansion (VE) in Npr1 null mutant (0-copy), wild-type (0-copy), and Npr1 gene-duplicated (4-copy) mice. GFR was measured in the three consecutive periods at 0–60 min before VE, 60–80 min during VE, and 80–160 min after VE. n = 9; 0-copy vs. 2-copy.

P < 0.05; 0-copy vs. 2-copy and 4-copy vs 2-copy;

P < 0.01.

Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that during the blood volume expansion, urine flow and sodium excretion were greatly increased in 2-copy and 4-copy animals; however, in 0-copy Npr1 mice only a minor change in urine flow and sodium excretion occurred despite highly elevated BP (203). It should be noted that gene-duplicated Npr1++/++ mice exhibited significantly higher urinary sodium excretion and urine flow compared with 2-copy wild-type animals. Moreover, after blood volume expansion, there was no significant change in potassium excretion in all Npr1 mice genotypes, including 0-copy, 2-copy, or 4-copy mice either before, during, or after blood volume expansion protocol (203).

The Npr1−/− mice exhibit harmfully elevated BP resembling untreated human hypertensive subjects (33, 34, 46, 150, 201, 203, 226, 227). In contrast, increased expression of Npr1 gene (4 copies) in mice significantly lowered SBP and greatly increased the intracellular accumulation of cGMP proportionately to Npr1 gene copy numbers (151, 163, 226, 249). The cascade of ANP/NPRA/cGMP signaling lowers SBP through its direct effects of natriuretic, diuretic, and vasodilatory responses (123, 128, 203). It also lowers BP indirectly by antagonizing the vasoactive pressure hormones, such as ANG II and vasopressin (142, 213). It is considered that the expression of Nppa and Nppb is greatly increased in hypertensive and hypertrophic failing heart patients, but it is still unclear whether ANP/NPRA system is activated to exert a protective effect by antagonizing the action of pressure hormones and decreasing the adverse effects of high BP due to retention of sodium and fluid volume. Moreover, it could also be a consequence of the detrimental cardiac remodeling due to altered levels of gene expression (16, 46, 92, 125, 155). It has been estimated that BP decreases progressively with increasing number of functional Npr1 gene copies with a change in mean arterial pressure of ~8 mmHg per gene copy and proportional increases in GC activity and accumulation of intracellular cGMP levels (151, 163, 203, 226). There is evidence to support the concept that ANP-BNP/NPRA signaling in the kidneys provides a renoprotective role especially under conditions of elevated BP levels (65).

Role of Npr1 in Counteracting the Effects of Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System and BP Regulation

Our previous findings have indicated that the kidney renin content in newborn Npr1−/− pups (2 days after birth) was 2.5-fold higher than in Npr1+/+ control pups, but the plasma renin concentrations in adult Npr1−/− null mutant mice were one-fourth of the wild-type Npr1+/+ animals (201). However, adult (16 wk) hypertensive Npr1−/− mutant animals exhibited 65–70% lower kidney renin contents as compared with Npr1+/+ animals (201). In contrast, the adrenal renin contents were twofold higher in Npr1−/− adult mice than in Npr1+/+ control mice. It should be noted that the effect of increased Npr1 gene-dosage on the renin activity and expression levels remains still unclear. It is possible, however, that the synthesis and expression of kidney renin mRNA and renin content in adult Npr1−/− mice are suppressed due to volume expansion, elevated BP, and/or activation of baroreceptors (156, 201, 203). It is also not yet clear whether the synthesis of intracellular renin in juxtaglomerular and connecting tubule cells is altered in Npr1 mice in a gene dose-dependent manner, which could be due to elevated BP, reflecting a decrease in plasma renin concentrations.

The renal ANG II levels seem to be regulated by ANP-NPRA/cGMP signaling and by additional factors, including salt diet, BP, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) itself (11, 220, 240, 246, 247, 249). Variations in dietary sodium intake are closely associated with changes in renal renin contents and plasma renin concentrations (143). Our previous studies have suggested that plasma ANG II levels were decreased in Npr1−/− mice as compared with Npr1+/+ controls; nevertheless, plasma aldosterone concentrations were greatly increased in these mutant animals (249). It is considered that the increased plasma aldosterone levels might be due to the increases in the adrenal renin contents (201). Elevated BP is known to decrease the plasma ANG II levels by inhibiting the synthesis and release of renin that seems to act as a negative feedback mechanism in the Npr1 gene-disrupted mice but not in wild-type mice (201). On the other hand, decreased plasma ANG II levels in Npr1 gene-duplicated mice as compared with wild-type mice seem to be due to a consequence of the antagonistic effects of ANP-BNP/NPRA signaling to RAAS. It is believed that elevations in the renal ANG II concentrations cause reductions in renal function and Na+ excretion that contribute to the sustained hypertension and lead to renal and vascular injury (144, 248). Increased excretion of sodium and urine output with decreased arterial BP in Npr1 gene-duplicated mice might attenuate the counteractive effects of the high-salt diet on the plasma ANG II and aldosterone concentrations (203). Altogether, NPRA signaling seems to exert renal protective effect on the blood volume and BP homeostasis in Npr1 gene-knockout mice.

Our previous studies have suggested that 1-copy haplotype Npr1+/− female mice receiving high-salt diet exhibited increased systolic BP compared with Npr1+/+ animals (247, 249). Moreover, Npr1 ablation led to chronic elevation of BP in mutant mice in a salt-sensitive manner (151). However, an earlier provocative report has indicated that BP remained unchanged in response to either low- or high-salt diets in Npr1 gene-knockout mice (carrying a simple insertion of a neomycin-resistance gene into exon 4 of Npr1 construct), with a similar degree of hypertension (116). Those earlier studies indicated that the ablation of Npr1 did not seem to exhibit salt-sensitive hypertension in mice. However, gene-knockout studies of Nppa have suggested that the deficiency of ANP exhibited its effect on BP in a salt-sensitive manner (81, 127). Interestingly, ANP-BNP/NPRA signaling opposes most of the effect of ANG II in both cellular and physiological environments (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antagonistic actions of ANG II and ANP

| ANG II | ANP/BNP |

|---|---|

| Cellular and whole body effects | |

| 1. Stimulates blood vessel and cell constriction (102, 129) | 1. Inhibits blood vessels constriction (4, 57, 190) |

| 2. Stimulates aldosterone release (238, 245) | 2. Inhibits aldosterone release (7, 10, 175) |

| 3. Stimulates vasopressin release (70, 169, 241) | 3. Inhibits vasopressin release (147, 174) |

| 4. Inhibits renin release (24, 64, 138) | 4. Inhibits renin release (17, 148, 201) |

| 5. Stimulates cell growth proliferation (13, 36, 77, 135, 139, 170, 239) | 5. Inhibits cell growth and proliferation (1, 4, 100, 194) |

| 6. Inhibits apoptosis (130, 170, 239) | 6. Induces apoptosis (74, 239) |

| 7. Enhances glomerulosclerosis (167) | 7. Inhibits glomerulosclerosis (167) |

| 8. Facilitates neurotransmission (52, 71) | 8. Inhibits neurotransmission (39, 40, 75, 140, 141) |

| 9. Causes vascular injury (9, 63, 237) | 9. Protects against vascular injury (16, 105) |

| 10. Increases blood pressure (9, 60, 176, 193, 202, 253, 254) | 10. Reduces blood pressure (16, 35, 81, 113, 203) |

| Biochemical Effects | |

| 1. Stimulates/activation of protein kinase C (100) | 1. Inhibits activation of protein kinase C (100, 101) |

| 2. Increases Ca2+ concentrations (16, 44, 235) | 2. Decreases Ca2+ concentrations (67, 114) |

| 3. Stimulates activation of MAP kinases (42, 77, 162, 171, 224, 252) | 3. Inhibits activation of MAP kinases (134, 161, 194, 221) |

| 4. Stimulates phosphoinositide metabolism (215, 218) | 4. Inhibits phosphoinositide metabolism (85, 86) |

| 5. Interacts with G protein-coupled receptors (88, 172, 200) | 5. Not actively involved with G proteins (85) |

| 6. Activates IKK/NF-κB inflammatory pathways (117, 179) | 6. Inhibits IKK/NF-κB inflammatory pathways (34, 98, 227) |

ANG II, angiotensin II; ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide.

It has been shown that low-salt diet increases the adrenal ANG II and aldosterone concentrations in Npr1−/− and Npr1+/− mutant mice as compared with the levels seen in mice fed with a normal-salt diet (247, 249). However, a high-salt diet lowered the adrenal ANG II and aldosterone concentrations in Npr1+/− and Npr1+/+ mice but not in Npr1++/+ and Npr1++/++ mice as compared with the levels in mice fed with a normal-salt diet. Those previous studies showed that the Npr1 gene copy numbers affect adrenal aldosterone level, especially with a low-salt diet. Sodium restriction increases the adrenal renin activity, ANG II levels, and aldosterone production (27, 38, 122). It was concluded that adrenal aldosterone concentrations were also affected in a Npr1 gene-dose-dependent manner, indicating that the release of adrenal aldosterone levels in 1-copy and 2-copy mice was suppressed in response to the high-salt diet as compared with mice fed the normal-salt diet. However, high-salt diet did not suppress adrenal aldosterone levels in Npr1 gene-duplicated mice (249). The underlying mechanism may be related to the elevated Na+ excretion and urine output that occurs with relatively low BP in Npr1 gene-duplicated 3-copy and 4-copy mice than in wild-type mice; thus, the inhibitory effect of the high-salt diet on adrenal aldosterone concentrations was attenuated in Npr1 gene-duplicated mice. The adrenal gland is more sensitive to a low-salt diet than to a high-salt diet, which is consistent with the fact that the adrenal gland functions to retain salt to regulate blood volume and BP homeostasis. Also, it is well known that a low-salt diet increases the plasma ANG II and aldosterone levels, whereas a high-salt diet inhibits these components of RAAS in the circulation (104, 136). Overall, ANP exerts inhibitory effects on both the synthesis and release of adrenal aldosterone levels (7, 16, 105, 154, 175).

Implication of ANP/NPRA Gene Polymorphisms in the Regulation of BP and Cardiovascular Disorders

ANP and BNP act on the kidneys to induce natriuresis and diuresis, thereby lowering the blood volume and BP (50, 105, 123, 154, 229). Previously, a small population has been identified in which hypertension is the consequence of single gene defects that are inherited in a Mendelian fashion; however, in the most of individuals, BP is determined by the action of many quantitative genes (68, 79, 110, 111, 204, 205). It is believed that genetic analysis provides a more accurate and faster approach to evaluate physiological functions. If the gene of interest is quantitative, such as BP and cardiovascular events, it requires optimum function in maintaining a uniform genetic background. Moreover, gene-targeting technology (gene-knockout and gene-duplication) has provided a unique strategy to study the physiological function in a gene-dose-dependent manner in genetically modified experimental animal models (87, 163, 206, 214, 247).

Genetic polymorphisms of Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 exist in relation to high BP and cardiovascular disorders in humans (146, 178, 188, 229, 234, 242). A relationship of gene polymorphism in the Nppa promoter region has also been shown with the left ventricular hypertrophy in the Italian hypertensive subjects (178, 229). Those previous findings indicated that individuals carrying Nppa variant alleles exhibited significantly decreased expression of Nppa and reduced levels of circulation ANP, which were associated with the cardiac hypertrophy and congestive heart failure (178, 229). Similarly, an association of a microsatellite marker in the Npr1 promoter region exhibited ventricular hypertrophy, suggesting that the ANP-BNP/NPRA system might contribute to cardiac remodeling in essential hypertensive subjects (178, 229, 242). Moreover, the relationship between hypertension and cardiovascular dysfunction has been noted that even the small increases in BP contributes toward cardiac harmful effects (146, 178, 188).

Previous findings have also indicated the prevalence of high BP with cardiovascular risks factors that have led to a belief in a role for genetic factors (106). A common genetic polymorphism in Nppa and Nppb was discovered to be associated with plasma levels of ANP and BNP, thus contributing toward interindividual variations in high BP and hypertension in humans (146). Those previous findings showed that single nucleotide polymorphisms in Nppa and Nppb were linked with increased plasma ANP/BNP levels and high BP. The contribution of gene mutations has been previously positively correlated for the monogenic forms of high BP, hypertension, and cardiovascular disorders in humans (25, 80, 111, 180, 219). Several pathways, including RAAS, have been suggested to regulate high BP and hypertension; however, the genetic determinants in these pathways contributing to interindividual differences in BP regulation have not been yet completely established. Therefore, an association of common polymorphisms in Nppa and Nppb loci with plasma levels of NPs contributing to interindividual variations in hypertension and the regulation of high BP seems to be a novel mechanism and needs further investigations. A polymorphism in 3′-noncoding region of Npr1 also seems to be linked with an increased expression of NH2-terminal-proBNP (NT-proBNP) in humans (234). Individuals with mutations in the Npr1 promoter region exhibit significantly higher levels of NT-proBNP. The intrinsic mechanisms for this effect could be due to mRNA instability of Npr1, contributing to a decreased translational level of the NPRA (94). The repressed effect of ANP-BNP/NPRA signaling due to a defect in the Npr1 might lead to a compensatory response to an increased expression and secretion of NPs. The positive co-relationship has been noted with Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 gene disruption in relation with essential hypertension, high BP, and cardiac hypertrophy in the mutant mice (Table 1).

NPRA PREVENTS RENAL INJURY, HYPERTROPHIC GROWTH, AND INFLAMMATION

High BP seems to contribute in initiating and sustaining the fibrotic and hypertrophic remodeling of the kidneys. Several growth factors, ANG II, cytokines, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are considered to play important roles in the pathogenesis of glomerular and tubulointerstitial fibrosis and hypertrophy of in the kidneys (68, 73, 90). The ANP/NPRA system facilitates renal hemodynamic functions (GFR and RPF) and has been implicated in preventing the renal injury and hypertrophic growth (65, 112). Renal fibrosis and glomerular inflammation exhibit complex pathophysiological etiology involving excessive generation of proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, imbalanced synthesis/degradation of MMPs, and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (78, 124, 132). Mice lacking functional Npr1 exhibit renal fibrosis and hypertrophic growth by altered expression of MMPs, ECM proteins, and proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (33, 34). It is considered that fibrosis plays a critical role in all types of sustained kidney disease, regardless of etiology (12, 43). Usually, the renal fibrosis is initiated from the excessive synthesis of collagen in mesangial cells, interstitial myofibroblasts, and vascular smooth muscle cells that seem to maintain the stimulated pathophysiological inflammation and fibrosis in the kidneys.

Our previous findings have indicated that altered levels of MMPs play a pivotal role in the initiation and development of the fibrotic growth of the kidneys and heart (33, 165, 227). Under normal conditions, the activity of MMPs is controlled by tissue-specific MMP inhibitors (TIMPs), which deactivate and/or inhibit MMPs during the posttranslational regulatory mechanisms (19, 33, 59, 227). The disruption of the balance between MMPs and TIMPs contributes to the pathophysiological processes of renal fibrosis and hypertrophic growth (166, 189, 223). Usually, TIMPs bind to the active site of MMPs, thereby blocking their access to ECM substrate protein molecules (109). Thus, the altered levels of MMPs and TIMPs could be critical in promoting the renal remodeling of ECM proteins that could contribute to the abnormal mesangial and tubulointerstitial cell architecture and organization. The regulated control of ECM homeostasis is maintained, in part, by a balance between MMPs and TIMPs. Progressive disorders in renal function seems to be associated with the development of glomerulosclerosis and also with renal fibrosis, which is characterized by increased accumulation of ECM proteins and structural rearrangements that involve cellular hypertrophy, hyperplasia, and proliferation (14, 33, 34, 93). The kidney sections stained with Masson’s trichrome showed progressive increases in collagen synthesis and deposition in the interstitial spaces in Npr1−/− and Npr1+/− mice compared with Npr1+/+ mice (33, 34).

Disruption of Npr1 and Altered Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines in the Kidneys

Increased production of proinflammatory cytokines is a hallmark feature of progressive fibrosis and hypertrophic growth in the kidney and other organs (21, 30, 153, 183, 207, 250). Previous studies have shown that several of the proinflammatory and profibrotic molecules, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukins-1, -2, -6, and -17 (Il-1, Il-2, Il-6, and Il-17), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) serve to amplify the inflammatory and fibrotic responsiveness in the kidneys of Npr1−/− mice (33, 34, 98, 99). Specifically, blocking the expression and function of proinflammatory cytokines before and/or during the progression of the inflammatory process has been considered a valuable tool in determining the contribution of these molecules in the initiation and progression of the inflammation and fibrotic disease states. However, it is possible that blockade of a single cytokine in the inflammatory cascade might be compensated by the enhanced expression of other cytokines to promote the proinflammatory functions (5, 6, 243). Therefore, the strategy to block the multiple cytokines should be adapted to gain therapeutic advantage to prevent renal inflammation and disease states. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1 Ra) treatment suppresses the expression and synthesis of several other proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-α (28, 152, 192, 225). Moreover, our recent studies have indicated that TGF-β1 antagonizes the transcriptional machinery of Npr1 in the cultured mesangial and vascular smooth muscle cells (190).

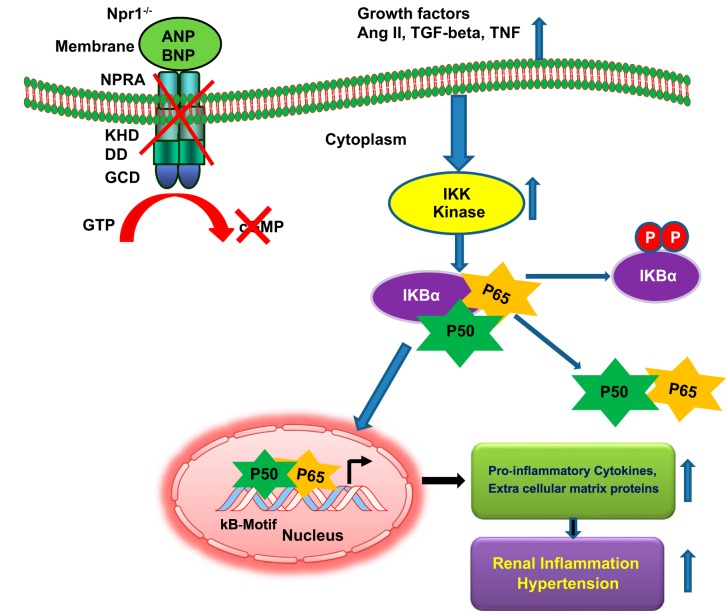

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) serves as a multifunctional proinflammatory signaling molecule that plays a pivotal role in cell survival, inflammation, and apoptosis (8, 32, 58). NF-κB also enhances the transcriptional activation of multiple genes, including various proinflammatory cytokines, MMPs, and ECM proteins that contribute to increased BP and renal damage in Npr1 gene-disrupted mice (33, 34). The activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB have been shown to enhance the expression of various proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and ECM proteins, leading to increased BP and renal damage in Npr1−/− mice (Fig. 3). It has been suggested that NF-κB activates the transcriptional machinery of many proinflammatory genes in both chronic and acute conditions of inflammatory responses in the kidneys (89, 108). The sustained induction of NF-κB has been shown in experimental animal models and human disease conditions (8, 32, 54, 58, 227). Modulation of NF-κB activation and signaling might be an important strategy to reduce cellular injury and inflammation in the absence of ANP-BNP/NPRA signaling (Fig. 3). There is increasing evidence to suggest that NF-κB is a critical mediator in the pathophysiology of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases, which are characterized by elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, MMPs, and ECM proteins (34, 115, 226, 227). Our previous findings have suggested that expression and synthesis of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) are induced in the renal macrophages in hypertensive disease states and play a critical role in the recruitment of monocytes during kidney inflammation and injury (33, 47). However, in the absence of ANP/NPRA/cGMP signaling cascade, the expression of both proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokine genes is significantly enhanced to contribute to the renal fibrosis and hypertrophy in Npr1−/− mice, independently of elevated BP (33, 34).

Fig. 3.

Diagrammatic representation of the Npr1 gene-disruption on renal remodeling, and blood pressure. Disruption of Npr1 gene leads to impaired renal functions, which triggers specific structural and molecular changes in 0-copy mice kidney. Activated inhibitory kappa kinase (IKK) induces the phosphorylation of IκBα, which then undergoes enzymatic degradation. The reduction of cytosolic IκBα favors the constitutive activation of NF-κB, which translocates into the nucleus and activates the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and extracellular matrix protein genes in the kidneys of Npr1 gene-disrupted mice. These molecular changes lead to increase in the inflammatory responses and high blood pressure in Npr1 gene-disrupted mutant mice.

Ablation of Npr1 Causes Renal Fibrosis and End-organ Damage

Previous studies have suggested that renal tubular damage occurs in Npr1−/− and Npr1+/− mice compared with Npr1+/+ mice (33). This damage was characterized by tubular dilation with flattened epithelium and progressive expansion of the interstitial spaces usually referred to as matrix mesangial expansion (MME), which was remarkably pronounced in the kidneys of Npr1 gene-knockout mice. Significant increases were observed in the immunoreactive expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in the glomeruli, proximal and distal tubules, and arterioles of 0-copy and 1-copy mice compared with 2-copy mice (34, 99). The expression of TGF-β1 was also increased by three- to fourfold in the kidneys of homozygous null mutant Npr1−/− mice compared with wild-type animals (33, 34). TGF-β1 contributes to the genesis of renal fibrosis in a gene-dose-dependent manner (68, 84). The Npr1 gene-disruption causes the renal fibrosis, hypertrophy, and ECM remodeling in mice with decreasing Npr1 gene copy numbers. There were significant increases in the kidney weight/body weight ratio, urinary albumin excretion, plasma creatinine concentrations, and reduced creatinine clearance rate, suggesting an increased incidence of renal pathology in Npr1−/− mice. Increased plasma creatinine was associated with the kidney pathologies of tubulointerstitial fibrosis, nephropathy, and polycystic chronic kidney disease conditions (66, 119, 168, 230).

It has been noted that the expression of both monocytes and macrophages is greatly enhanced in chronic kidney disorders, leading to renal fibrosis (76). The onset of glomerular hypertrophy with the thickening of the basement membrane leads to the enlargement of glomerulus with the onset of MME in chronic renal disease conditions (22, 121, 208, 210). The proinflammatory molecule such as TNF-α has been shown to contribute to chronic kidney inflammation and proliferation of mesangial cells that usually precede interstitial matrix deposition in the obstruction-induced renal injury and fibrosis (30, 124, 145). The previous studies have also shown that an increased expression of TGF-β1 exerts a regulatory effect on the development of MME in the kidneys; however, the inhibition by its antibodies effectively blocked the glomerular enlargement and matrix expression (195, 196, 251).

The ANP/NPRA system has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of mesangial and vascular smooth muscle cells in the kidneys by increased production of second messenger cGMP (18, 157, 162, 163, 194, 221). An enhanced expression of PCNA in kidney tissues reflected the renal hypertrophy in Npr1−/− mice, although the percentages of glomeruli with PCNA-positive cells were increased in the kidneys of both homozygous and heterozygous Npr1 gene-knockout mice. The severity of these increases was largely pronounced in Npr1−/− null mutant animals. Our previous findings have demonstrated that both histological and functional changes in the kidneys correlate with the progressive hypertrophy and fibrosis in Npr1 gene-knockout mice. Nevertheless, the normalization of BP showed only a partial effect in reversing renal fibrosis in Npr1−/− mice (33). It is considered that α-SMA-positive cells serve as a major source of profibrotic cytokine TGF-β1 and have been implicated in the development of tubulointerstitial renal fibrotic lesions (211). Simultaneously, treatment with captopril and losartan has also shown a partial attenuation in immunoexpression of α-SMA in Npr1−/− mice (33). However, those previous studies from our laboratory indicated that the administration of bendroflumethiazide significantly lowered BP but did not produce any beneficial effect in either reversing the kidney fibrosis or decreasing the expression of α-SMA in Npr1−/− mice. Moreover, the residual renal damage seems to occur, despite treatment of Npr1 null mutant mice with three different antihypertensive drugs.

NPRA SIGNALING IN DIABETES COMPLICATIONS

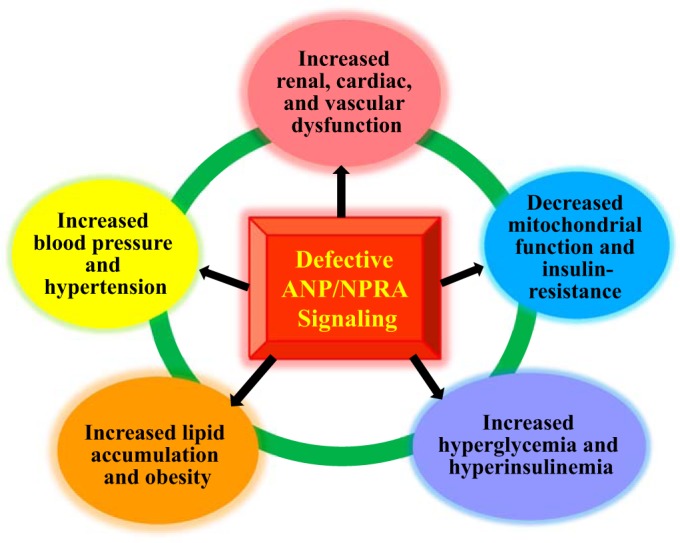

The evidence suggests that reduced levels of ANP seem to be associated with insulin resistance, obesity, and metabolic syndrome in humans (231, 232). However, studies have also shown that ANP/NPRA/cGMP signaling promotes muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and fat oxidation by involving the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) to prevent the glucose intolerance (131, 133). Moreover, murine adipocytes have been shown to exhibit predominance of NPRC and the lipolytic effect of NPs, which was totally salvaged in Npr3 (encoding NPRC) gene-disrupted mice (15, 191). The ANP/NPRA system has been shown to enhance the browning of white adipocytes in humans, which is considered physiologically beneficial (48, 133). Mice exposed to low temperatures exhibited increased release of circulating ANP with enhanced NPRA/cGMP signaling but showed reduced expression levels of NPRC in both brown and white adipose tissues (15). It has been suggested that the ANP/NPRA system might play a pivotal role in enhancing the expression of PGC-1α, which stimulates oxidative phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle tissues (49). Those previous findings indicated that NPRA signaling enhances and promotes the mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and fat oxidation, which might contribute to the enhanced ability of exercise-induced fat oxidation and energy use. Thus, under aerobic conditions in response to exercise, ANP/NPRA/cGMP signaling has been suggested to promote energy expenditure, which has a central role in regulating the supply of fatty acids for metabolic utilization in both cardiac and skeletal muscle cells (182). Studies in humans and experimental mouse models have suggested that there seems to be a pathophysiological link between obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance with defective NPRA signaling in the skeletal muscle cells (31, 137). Those previous findings suggested that increased plasma ANP/BNP concentrations in diabetic mice and a high-fat diet led to improved blood glucose levels, enhanced insulin signaling, increased lipid oxidation, and reduced lipotoxic effects. It was also demonstrated that NPs increased the lipid oxidation, which accelerated the induction of PGC-1α, independently of PPAR-δ activation (31). Similarly, studies have also shown that NPRA/cGMP-dependent signaling enhanced PGC-1α gene expression in white fat and skeletal muscle cells, suggesting a role of NPRA in diabetes (15, 49). Interestingly, a recent finding has provided the provocative evidence that the ANP/NPRA system might contribute toward the regulatory control of fat mass accumulation in humans (37). On the other hand, defective ANP/NPRA signaling could lead to malfunctional disorders, leading to increased hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, and thereby could provoke high BP, increased lipid accumulation, decreased mitochondrial function, and thus increased renal, cardiac, and vascular dysfunction (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Defective ANP-BNP/NPRA signaling could provoke renal, cardiac, and vascular dysfunction. The defects in ANP-BNP/NPRA signaling cascade are usually associated with hypertension, heart failure, vascular disease, and metabolic syndrome. Thus, defective ANP-BNP/NPRA/cGMP signaling could lead to renal, cardiac, and vascular dysfunction.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Recent molecular and genetic studies have greatly contributed toward the understanding of the functional impact of Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 with emphasis on the kidney disease, hypertension, and cardiovascular dysfunction. The investigative growth in the studies of ANP/NPRA signaling system have advanced our understanding of volume overload, BP, and renal and cardiovascular disorders. Studies utilizing genetically modified mouse models have helped delineate the pathophysiological conditions and physiological functions by overexpression or underexpression of Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 gene. Specifically, gene-targeting strategies (gene knockout and gene duplication) have greatly helped to produce mouse models of altered Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 genes to define their precise roles in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Using global gene-targeted mice, investigators have been able to delineate the impact of Npr1 expression on BP and other cardiovascular events governed by decreasing or increasing number of Npr1 gene copies in a gene-dose-dependent manner. Future investigations using Npr1 gene-targeted mice in a cell-specific manner in target organs, especially in the kidney, will continue to have enormous potential in studies of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases by altering the number of Npr1 gene copies and thus the product levels of both NPs and NPRA in an identical genetic background. Thus far, the results of animal experimental studies have introduced novel tools for examining the beneficial impact of altered ANP/NPRA signaling cascade in hypertension and cardiovascular disease states.

Although impressive progress has been made, much remains to be learned and discovered about the ANP/NPRA/cGMP system in terms of its signaling, activation, mechanisms, and physiological and pathophysiological roles in hypertension by coordinated function in different organ systems. Furthermore, the molecular events that determine the activation and termination of signals in the ANP-BNP/NPRA system are not yet completely understood. Information regarding the roles of NPs and NPRA at the molecular levels in specific disease conditions, including hypertension, renal disease, and cardiovascular events, is still lacking. Similarly, the paradigm shift of molecular, cellular, and genetic mechanisms of coordinated actions of ANP-BNP/NPRA system is still incompletely understood. Future studies should greatly help in resolving the physiological complexities related to high BP and renal and cardiovascular dysfunction. Current and future investigations should be directed at achieving unique perspectives for determining molecular and genetic aspects of Nppa, Nppb, and Npr1 regulation, expression, and function in physiological and pathophysiological milieu. Future research in the field of the ANP-BNP/NPRA/cGMP system might identify new therapeutic loci for the treatment and prevention of high BP and renal and cardiovascular diseases in humans.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01HL-057531 and R01HL-062147.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.N.P. conceived and designed research; interpreted results of experiments; prepared figures; drafted manuscript; edited and revised manuscript; and approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author expresses sincere gratitude to past and present laboratory personnel and collaborators for their immense contributions related to this work. The author also thanks Kamala Pandey for the help in the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abell TJ, Richards AM, Ikram H, Espiner EA, Yandle T. Atrial natriuretic factor inhibits proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells stimulated by platelet-derived growth factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 160: 1392–1396, 1989. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(89)80158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand-Srivastava MB. Natriuretic peptide receptor-C signaling and regulation. Peptides 26: 1044–1059, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand-Srivastava MB, Trachte GJ. Atrial natriuretic factor receptors and signal transduction mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev 45: 455–497, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appel RG. Mechanism of atrial natriuretic factor-induced inhibition of rat mesangial cell mitogenesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 259: E312–E318, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.259.3.E312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arend WP. The balance between IL-1 and IL-1Ra in disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 13: 323–340, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(02)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arend WP, Malyak M, Guthridge CJ, Gabay C. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: role in biology. Annu Rev Immunol 16: 27–55, 1998. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atarashi K, Mulrow PJ, Franco-Saenz R, Snajdar R, Rapp J. Inhibition of aldosterone production by an atrial extract. Science 224: 992–994, 1984. doi: 10.1126/science.6326267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldwin HS. Early embryonic vascular development. Cardiovasc Res 31, Suppl 1: E34–E45, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(95)00215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, Shbat L, Laurant P, Neves MF, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension 57: 469–476, 2011. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett PQ, Isales CM. The role of cyclic nucleotides in atrial natriuretic peptide-mediated inhibition of aldosterone secretion. Endocrinology 122: 799–808, 1988. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-3-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassett MH, White PC, Rainey WE. The regulation of aldosterone synthase expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol 217: 67–74, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker GJ, Hewitson TD. The role of tubulointerstitial injury in chronic renal failure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 9: 133–138, 2000. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200003000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhaskaran M, Reddy K, Radhakrishanan N, Franki N, Ding G, Singhal PC. Angiotensin II induces apoptosis in renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F955–F965, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00246.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Border WA, Noble NA, Yamamoto T, Harper JR, Yamaguchi Y, Pierschbacher MD, Ruoslahti E. Natural inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta protects against scarring in experimental kidney disease. Nature 360: 361–364, 1992. doi: 10.1038/360361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bordicchia M, Liu D, Amri EZ, Ailhaud G, Dessì-Fulgheri P, Zhang C, Takahashi N, Sarzani R, Collins S. Cardiac natriuretic peptides act via p38 MAPK to induce the brown fat thermogenic program in mouse and human adipocytes. J Clin Invest 122: 1022–1036, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI59701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner BM, Ballermann BJ, Gunning ME, Zeidel ML. Diverse biological actions of atrial natriuretic peptide. Physiol Rev 70: 665–699, 1990. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnett JC Jr, Granger JP, Opgenorth TJ. Effects of synthetic atrial natriuretic factor on renal function and renin release. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 247: F863–F866, 1984. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1984.247.5.F863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao L, Gardner DG. Natriuretic peptides inhibit DNA synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 25: 227–234, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.25.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cawston TE, Curry VA, Clark IM, Hazleman BL. Identification of a new metalloproteinase inhibitor that forms tight-binding complexes with collagenase. Biochem J 269: 183–187, 1990. doi: 10.1042/bj2690183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang MS, Lowe DG, Lewis M, Hellmiss R, Chen E, Goeddel DV. Differential activation by atrial and brain natriuretic peptides of two different receptor guanylate cyclases. Nature 341: 68–72, 1989. doi: 10.1038/341068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen G, Goeddel DV. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science 296: 1634–1635, 2002. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen G, Paka L, Kako Y, Singhal P, Duan W, Pillarisetti S. A protective role for kidney apolipoprotein E. Regulation of mesangial cell proliferation and matrix expansion. J Biol Chem 276: 49142–49147, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen HH, Burnett JC Jr. The natriuretic peptides in heart failure: diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 111: 406–416, 1999. doi: 10.1111/paa.1999.111.5.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Kim SM, Eisner C, Oppermann M, Huang Y, Mizel D, Li L, Chen M, Sequeira Lopez ML, Weinstein LS, Gomez RA, Schnermann J, Briggs JP. Stimulation of renin secretion by angiotensin II blockade is Gsalpha-dependent. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 986–992, 2010. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009030307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen MA. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in older adults. Am J Med 122: 713–723, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chinkers M, Garbers DL, Chang MS, Lowe DG, Chin HM, Goeddel DV, Schulz S. A membrane form of guanylate cyclase is an atrial natriuretic peptide receptor. Nature 338: 78–83, 1989. doi: 10.1038/338078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiou CY, Williams GH, Kifor I. Study of the rat adrenal renin-angiotensin system at a cellular level. J Clin Invest 96: 1375–1381, 1995. doi: 10.1172/JCI118172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christadoss P, Goluszko E. Treatment of experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis with recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor Fc protein. J Neuroimmunol 122: 186–190, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(01)00473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chusho H, Tamura N, Ogawa Y, Yasoda A, Suda M, Miyazawa T, Nakamura K, Nakao K, Kurihara T, Komatsu Y, Itoh H, Tanaka K, Saito Y, Katsuki M, Nakao K. Dwarfism and early death in mice lacking C-type natriuretic peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4016–4021, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071389098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooker LA, Peterson D, Rambow J, Riser ML, Riser RE, Najmabadi F, Brigstock D, Riser BL. TNF-alpha, but not IFN-gamma, regulates CCN2 (CTGF), collagen type I, and proliferation in mesangial cells: possible roles in the progression of renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F157–F165, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00508.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coué M, Badin PM, Vila IK, Laurens C, Louche K, Marquès MA, Bourlier V, Mouisel E, Tavernier G, Rustan AC, Galgani JE, Joanisse DR, Smith SR, Langin D, Moro C. Defective Natriuretic Peptide Receptor Signaling in Skeletal Muscle Links Obesity to Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 64: 4033–4045, 2015. doi: 10.2337/db15-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Courtois G, Gilmore TD. Mutations in the NF-kappaB signaling pathway: implications for human disease. Oncogene 25: 6831–6843, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das S, Au E, Krazit ST, Pandey KN. Targeted disruption of guanylyl cyclase-A/natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene provokes renal fibrosis and remodeling in null mutant mice: role of proinflammatory cytokines. Endocrinology 151: 5841–5850, 2010. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Das S, Periyasamy R, Pandey KN. Activation of IKK/NF-κB provokes renal inflammatory responses in guanylyl cyclase/natriuretic peptide receptor-A gene-knockout mice. Physiol Genomics 44: 430–442, 2012. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00147.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Bold AJ, Borenstein HB, Veress AT, Sonnenberg H. A rapid and potent natriuretic response to intravenous injection of atrial myocardial extract in rats. Life Sci 28: 89–94, 1981. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Ciuceis C, Amiri F, Brassard P, Endemann DH, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reduced vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries of angiotensin II-infused macrophage colony-stimulating factor-deficient mice: evidence for a role in inflammation in angiotensin-induced vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 2106–2113, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000181743.28028.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dinas PC, Nintou E, Psychou D, Granzotto M, Rossato M, Vettor R, Jamurtas AZ, Koutedakis Y, Metsios GS, Flouris AD. Association of fat mass profile with natriuretic peptide receptor alpha in subcutaneous adipose tissue of medication-free healthy men: A cross-sectional study. F1000 Res 7: 327, 2018. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14198.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doi Y, Atarashi K, Franco-Saenz R, Mulrow PJ. Effect of changes in sodium or potassium balance, and nephrectomy, on adrenal renin and aldosterone concentrations. Hypertension 6: I124–I129, 1984. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.6.2_Pt_2.I124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drewett J, Marchand G, Ziegler R, Trachte G. Atrial natriuretic factor inhibits norepinephrine release in an adrenergic clonal cell line (PC12). Eur J Pharmacol 150: 175–179, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90765-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drewett JG, Trachte GJ, Marchand GR. Atrial natriuretic factor inhibits adrenergic and purinergic neurotransmission in the rabbit isolated vas deferens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 248: 135–142, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duda T, Goraczniak RM, Sharma RK. Site-directed mutational analysis of a membrane guanylate cyclase cDNA reveals the atrial natriuretic factor signaling site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 7882–7886, 1991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duff JL, Berk BC, Corson MA. Angiotensin II stimulates the pp44 and pp42 mitogen-activated protein kinases in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 188: 257–264, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(92)92378-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eddy AA. Molecular basis of renal fibrosis. Pediatr Nephrol 15: 290–301, 2000. doi: 10.1007/s004670000461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eguchi S, Numaguchi K, Iwasaki H, Matsumoto T, Yamakawa T, Utsunomiya H, Motley ED, Kawakatsu H, Owada KM, Hirata Y, Marumo F, Inagami T. Calcium-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation mediates the angiotensin II-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 273: 8890–8896, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, Chasman DI, Smith AV, Tobin MD, Verwoert GC, Hwang SJ, Pihur V, Vollenweider P, O’Reilly PF, Amin N, Bragg-Gresham JL, Teumer A, Glazer NL, Launer L, Zhao JH, Aulchenko Y, Heath S, Sõber S, Parsa A, Luan J, Arora P, Dehghan A, Zhang F, Lucas G, Hicks AA, Jackson AU, Peden JF, Tanaka T, Wild SH, Rudan I, Igl W, Milaneschi Y, Parker AN, Fava C, Chambers JC, Fox ER, Kumari M, Go MJ, van der Harst P, Kao WH, Sjögren M, Vinay DG, Alexander M, Tabara Y, Shaw-Hawkins S, Whincup PH, Liu Y, Shi G, Kuusisto J, Tayo B, Seielstad M, Sim X, Nguyen KD, Lehtimäki T, Matullo G, Wu Y, Gaunt TR, Onland-Moret NC, Cooper MN, Platou CG, Org E, Hardy R, Dahgam S, Palmen J, Vitart V, Braund PS, Kuznetsova T, Uiterwaal CS, Adeyemo A, Palmas W, Campbell H, Ludwig B, Tomaszewski M, Tzoulaki I, Palmer ND, Aspelund T, Garcia M, Chang YP, O’Connell JR, Steinle NI, Grobbee DE, Arking DE, Kardia SL, Morrison AC, Hernandez D, Najjar S, McArdle WL, Hadley D, Brown MJ, Connell JM, Hingorani AD, Day IN, Lawlor DA, Beilby JP, Lawrence RW, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Ongen H, Dreisbach AW, Li Y, Young JH, Bis JC, Kähönen M, Viikari J, Adair LS, Lee NR, Chen MH, Olden M, Pattaro C, Bolton JA, Köttgen A, Bergmann S, Mooser V, Chaturvedi N, Frayling TM, Islam M, Jafar TH, Erdmann J, Kulkarni SR, Bornstein SR, Grässler J, Groop L, Voight BF, Kettunen J, Howard P, Taylor A, Guarrera S, Ricceri F, Emilsson V, Plump A, Barroso I, Khaw KT, Weder AB, Hunt SC, Sun YV, Bergman RN, Collins FS, Bonnycastle LL, Scott LJ, Stringham HM, Peltonen L, Perola M, Vartiainen E, Brand SM, Staessen JA, Wang TJ, Burton PR, Soler Artigas M, Dong Y, Snieder H, Wang X, Zhu H, Lohman KK, Rudock ME, Heckbert SR, Smith NL, Wiggins KL, Doumatey A, Shriner D, Veldre G, Viigimaa M, Kinra S, Prabhakaran D, Tripathy V, Langefeld CD, Rosengren A, Thelle DS, Corsi AM, Singleton A, Forrester T, Hilton G, McKenzie CA, Salako T, Iwai N, Kita Y, Ogihara T, Ohkubo T, Okamura T, Ueshima H, Umemura S, Eyheramendy S, Meitinger T, Wichmann HE, Cho YS, Kim HL, Lee JY, Scott J, Sehmi JS, Zhang W, Hedblad B, Nilsson P, Smith GD, Wong A, Narisu N, Stančáková A, Raffel LJ, Yao J, Kathiresan S, O’Donnell CJ, Schwartz SM, Ikram MA, Longstreth WT Jr, Mosley TH, Seshadri S, Shrine NR, Wain LV, Morken MA, Swift AJ, Laitinen J, Prokopenko I, Zitting P, Cooper JA, Humphries SE, Danesh J, Rasheed A, Goel A, Hamsten A, Watkins H, Bakker SJ, van Gilst WH, Janipalli CS, Mani KR, Yajnik CS, Hofman A, Mattace-Raso FU, Oostra BA, Demirkan A, Isaacs A, Rivadeneira F, Lakatta EG, Orru M, Scuteri A, Ala-Korpela M, Kangas AJ, Lyytikäinen LP, Soininen P, Tukiainen T, Würtz P, Ong RT, Dörr M, Kroemer HK, Völker U, Völzke H, Galan P, Hercberg S, Lathrop M, Zelenika D, Deloukas P, Mangino M, Spector TD, Zhai G, Meschia JF, Nalls MA, Sharma P, Terzic J, Kumar MV, Denniff M, Zukowska-Szczechowska E, Wagenknecht LE, Fowkes FG, Charchar FJ, Schwarz PE, Hayward C, Guo X, Rotimi C, Bots ML, Brand E, Samani NJ, Polasek O, Talmud PJ, Nyberg F, Kuh D, Laan M, Hveem K, Palmer LJ, van der Schouw YT, Casas JP, Mohlke KL, Vineis P, Raitakari O, Ganesh SK, Wong TY, Tai ES, Cooper RS, Laakso M, Rao DC, Harris TB, Morris RW, Dominiczak AF, Kivimaki M, Marmot MG, Miki T, Saleheen D, Chandak GR, Coresh J, Navis G, Salomaa V, Han BG, Zhu X, Kooner JS, Melander O, Ridker PM, Bandinelli S, Gyllensten UB, Wright AF, Wilson JF, Ferrucci L, Farrall M, Tuomilehto J, Pramstaller PP, Elosua R, Soranzo N, Sijbrands EJ, Altshuler D, Loos RJ, Shuldiner AR, Gieger C, Meneton P, Uitterlinden AG, Wareham NJ, Gudnason V, Rotter JI, Rettig R, Uda M, Strachan DP, Witteman JC, Hartikainen AL, Beckmann JS, Boerwinkle E, Vasan RS, Boehnke M, Larson MG, Järvelin MR, Psaty BM, Abecasis GR, Chakravarti A, Elliott P, van Duijn CM, Newton-Cheh C, Levy D, Caulfield MJ, Johnson T, International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association Studies; CARDIoGRAM consortium; CKDGen Consortium; KidneyGen Consortium; EchoGen consortium; CHARGE-HF consortium . Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature 478: 103–109, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ellmers LJ, Scott NJ, Piuhola J, Maeda N, Smithies O, Frampton CM, Richards AM, Cameron VA. Npr1-regulated gene pathways contributing to cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J Mol Endocrinol 38: 245–257, 2007. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elmarakby AA, Quigley JE, Pollock DM, Imig JD. Tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade increases renal Cyp2c23 expression and slows the progression of renal damage in salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension 47: 557–562, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000198545.01860.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Enerbäck S. Human brown adipose tissue. Cell Metab 11: 248–252, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engeli S, Birkenfeld AL, Badin PM, Bourlier V, Louche K, Viguerie N, Thalamas C, Montastier E, Larrouy D, Harant I, de Glisezinski I, Lieske S, Reinke J, Beckmann B, Langin D, Jordan J, Moro C. Natriuretic peptides enhance the oxidative capacity of human skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest 122: 4675–4679, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI64526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Espiner EA. Physiology of natriuretic peptides: cardiovascular function, in Contemporary Endocrinology Natriuretic Peptides in Health and Disease (Samson WK, Levin ER, editors). Totowa, NJ: Humana, 1997, p. 123–146. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-3960-4_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Felker GM, Petersen JW, Mark DB. Natriuretic peptides in the diagnosis and management of heart failure. CMAJ 175: 611–617, 2006. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferguson AV, Washburn DL, Latchford KJ. Hormonal and neurotransmitter roles for angiotensin in the regulation of central autonomic function. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 226: 85–96, 2001. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forssmann WG, Richter R, Meyer M. The endocrine heart and natriuretic peptides: histochemistry, cell biology, and functional aspects of the renal urodilatin system. Histochem Cell Biol 110: 335–357, 1998. doi: 10.1007/s004180050295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frantz S, Fraccarollo D, Wagner H, Behr TM, Jung P, Angermann CE, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Sustained activation of nuclear factor kappa B and activator protein 1 in chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 57: 749–756, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00723-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fuller F, Porter JG, Arfsten AE, Miller J, Schilling JW, Scarborough RM, Lewicki JA, Schenk DB. Atrial natriuretic peptide clearance receptor. Complete sequence and functional expression of cDNA clones. J Biol Chem 263: 9395–9401, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garbers DL. Guanylyl cyclase receptors and their endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine ligands. Cell 71: 1–4, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90258-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garcia R, Thibault G, Cantin M, Genest J. Effect of a purified atrial natriuretic factor on rat and rabbit vascular strips and vascular beds. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 247: R34–R39, 1984. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.1.R34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerondakis S, Grumont R, Gugasyan R, Wong L, Isomura I, Ho W, Banerjee A. Unravelling the complexities of the NF-kappaB signalling pathway using mouse knockout and transgenic models. Oncogene 25: 6781–6799, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goldberg GI, Marmer BL, Grant GA, Eisen AZ, Wilhelm S, He CS. Human 72-kilodalton type IV collagenase forms a complex with a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteases designated TIMP-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 8207–8211, 1989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gratze P, Dechend R, Stocker C, Park JK, Feldt S, Shagdarsuren E, Wellner M, Gueler F, Rong S, Gross V, Obst M, Plehm R, Alenina N, Zenclussen A, Titze J, Small K, Yokota Y, Zenke M, Luft FC, Muller DN. Novel role for inhibitor of differentiation 2 in the genesis of angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circulation 117: 2645–2656, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.760116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gutkowska J, Antunes-Rodrigues J, McCann SM. Atrial natriuretic peptide in brain and pituitary gland. Physiol Rev 77: 465–515, 1997. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gutkowska J, Jankowski M, Sairam MR, Fujio N, Reis AM, Mukaddam-Daher S, Tremblay J. Hormonal regulation of natriuretic peptide system during induced ovarian follicular development in the rat. Biol Reprod 61: 162–170, 1999. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med 204: 2449–2460, 2007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hackenthal E, Aktories K, Jakobs KH. Mode of inhibition of renin release by angiotensin II. J Hypertens Suppl 3: S263–S265, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hannken T, Schroeder R, Stahl RA, Wolf G. Atrial natriuretic peptide attenuates ANG II-induced hypertrophy of renal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F81–F90, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.1.F81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haseyama T, Fujita T, Hirasawa F, Tsukada M, Wakui H, Komatsuda A, Ohtani H, Miura AB, Imai H, Koizumi A. Complications of IgA nephropathy in a non-insulin-dependent diabetes model, the Akita mouse. Tohoku J Exp Med 198: 233–244, 2002. doi: 10.1620/tjem.198.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hassid A. Atriopeptin II decreases cytosolic free Ca in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 251: C681–C686, 1986. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1986.251.5.C681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hathaway CK, Gasim AM, Grant R, Chang AS, Kim HS, Madden VJ, Bagnell CR Jr, Jennette JC, Smithies O, Kakoki M. Low TGFβ1 expression prevents and high expression exacerbates diabetic nephropathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 5815–5820, 2015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504777112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.He XL, Dukkipati A, Wang X, Garcia KC. A new paradigm for hormone recognition and allosteric receptor activation revealed from structural studies of NPR-C. Peptides 26: 1035–1043, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Henrich WL, Walker BR, Handelman WA, Erickson AL, Arnold PE, Schrier RW. Effects of angiotensin II on plasma antidiuretic hormone and renal water excretion. Kidney Int 30: 503–508, 1986. doi: 10.1038/ki.1986.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Henry M, Grob M, Mouginot D. Endogenous angiotensin II facilitates GABAergic neurotransmission afferent to the Na+-responsive neurons of the rat median preoptic nucleus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R783–R792, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00226.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Horio T, Nishikimi T, Yoshihara F, Matsuo H, Takishita S, Kangawa K. Inhibitory regulation of hypertrophy by endogenous atrial natriuretic peptide in cultured cardiac myocytes. Hypertension 35: 19–24, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.35.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang Z, Wen Q, Zhou SF, Yu XQ. Differential chemokine expression in tubular cells in response to urinary proteins from patients with nephrotic syndrome. Cytokine 42: 222–233, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hutchinson HG, Trindade PT, Cunanan DB, Wu CF, Pratt RE. Mechanisms of natriuretic-peptide-induced growth inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res 35: 158–167, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Inagami T, Nakamaru M, Pandey KN, Naruse M, Naruse K, Misono K, Okamura T, Kawamura M. Intracellular action of renin, angiotensin production and release. J Hypertens Suppl 4: S11–S16, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Isbel NM, Hill PA, Foti R, Mu W, Hurst LA, Stambe C, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Tubules are the major site of M-CSF production in experimental kidney disease: correlation with local macrophage proliferation. Kidney Int 60: 614–625, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ishizawa K, Izawa Y, Ito H, Miki C, Miyata K, Fujita Y, Kanematsu Y, Tsuchiya K, Tamaki T, Nishiyama A, Yoshizumi M. Aldosterone stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via big mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 activation. Hypertension 46: 1046–1052, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000172622.51973.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Javaid B, Quigg RJ. Treatment of glomerulonephritis: will we ever have options other than steroids and cytotoxics? Kidney Int 67: 1692–1703, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jeunemaitre X, Soubrier F, Kotelevtsev YV, Lifton RP, Williams CS, Charru A, Hunt SC, Hopkins PN, Williams RR, Lalouel JM, Corvol P. Molecular basis of human hypertension: role of angiotensinogen. Cell 71: 169–180, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90275-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ji W, Foo JN, O’Roak BJ, Zhao H, Larson MG, Simon DB, Newton-Cheh C, State MW, Levy D, Lifton RP. Rare independent mutations in renal salt handling genes contribute to blood pressure variation. Nat Genet 40: 592–599, 2008. doi: 10.1038/ng.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.John SW, Krege JH, Oliver PM, Hagaman JR, Hodgin JB, Pang SC, Flynn TG, Smithies O. Genetic decreases in atrial natriuretic peptide and salt-sensitive hypertension. Science 267: 679–681, 1995. doi: 10.1126/science.7839143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kake T, Kitamura H, Adachi Y, Yoshioka T, Watanabe T, Matsushita H, Fujii T, Kondo E, Tachibe T, Kawase Y, Jishage K, Yasoda A, Mukoyama M, Nakao K. Chronically elevated plasma C-type natriuretic peptide level stimulates skeletal growth in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E1339–E1348, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00272.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 365: 217–223, 2005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Khan S, Jena G. Sodium butyrate, a HDAC inhibitor ameliorates eNOS, iNOS and TGF-β1-induced fibrogenesis, apoptosis and DNA damage in the kidney of juvenile diabetic rats. Food Chem Toxicol 73: 127–139, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Khurana ML, Pandey KN. Catalytic activation of guanylate cyclase/atrial natriuretic factor receptor by combined effects of ANF and GTP gamma S in plasma membranes of Leydig tumor cells: involvement of G-proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys 316: 392–398, 1995. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khurana ML, Pandey KN. Receptor-mediated stimulatory effect of atrial natriuretic factor, brain natriuretic peptide, and C-type natriuretic peptide on testosterone production in purified mouse Leydig cells: activation of cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme. Endocrinology 133: 2141–2149, 1993. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.8404664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim HS, Krege JH, Kluckman KD, Hagaman JR, Hodgin JB, Best CF, Jennette JC, Coffman TM, Maeda N, Smithies O. Genetic control of blood pressure and the angiotensinogen locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 2735–2739, 1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim J, Ahn S, Rajagopal K, Lefkowitz RJ. Independent beta-arrestin2 and Gq/protein kinase Czeta pathways for ERK stimulated by angiotensin type 1A receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells converge on transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem 284: 11953–11962, 2009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808176200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim JH, Ha IS, Hwang CI, Lee YJ, Kim J, Yang SH, Kim YS, Cao YA, Choi S, Park WY. Gene expression profiling of anti-GBM glomerulonephritis model: the role of NF-kappaB in immune complex kidney disease. Kidney Int 66: 1826–1837, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim S, Iwao H. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmacol Rev 52: 11–34, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kishimoto I, Dubois SK, Garbers DL. The heart communicates with the kidney exclusively through the guanylyl cyclase-A receptor: acute handling of sodium and water in response to volume expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 6215–6219, 1996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kishimoto I, Tokudome T, Nakao K, Kangawa K. Natriuretic peptide system: an overview of studies using genetically engineered animal models. FEBS J 278: 1830–1841, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Mechanisms of fibrogenesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233: 109–122, 2008. doi: 10.3181/0707-MR-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Knowles JW, Erickson LM, Guy VK, Sigel CS, Wilder JC, Maeda N. Common variations in noncoding regions of the human natriuretic peptide receptor A gene have quantitative effects. Hum Genet 112: 62–70, 2003. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0834-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Knowles JW, Esposito G, Mao L, Hagaman JR, Fox JE, Smithies O, Rockman HA, Maeda N. Pressure-independent enhancement of cardiac hypertrophy in natriuretic peptide receptor A-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 107: 975–984, 2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI11273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koh GY, Klug MG, Field LJ. Atrial natriuretic factor and transgenic mice. Hypertension 22: 634–639, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.22.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Koller KJ, de Sauvage FJ, Lowe DG, Goeddel DV. Conservation of the kinaselike regulatory domain is essential for activation of the natriuretic peptide receptor guanylyl cyclases. Mol Cell Biol 12: 2581–2590, 1992. doi: 10.1128/MCB.12.6.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kumar P, Gogulamudi VR, Periasamy R, Raghavaraju G, Subramanian U, Pandey KN. Inhibition of HDAC enhances STAT acetylation, blocks NF-κB, and suppresses the renal inflammation and fibrosis in Npr1 haplotype male mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 313: F781–F795, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00166.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kumar P, Periyasamy R, Das S, Neerukonda S, Mani I, Pandey KN. All-trans retinoic acid and sodium butyrate enhance natriuretic peptide receptor a gene transcription: role of histone modification. Mol Pharmacol 85: 946–957, 2014. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.092221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kumar R, Cartledge WA, Lincoln TM, Pandey KN. Expression of guanylyl cyclase-A/atrial natriuretic peptide receptor blocks the activation of protein kinase C in vascular smooth muscle cells. Role of cGMP and cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Hypertension 29: 414–421, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.29.1.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kumar R, von Geldern TW, Calle RA, Pandey KN. Stimulation of atrial natriuretic peptide receptor/guanylyl cyclase- A signaling pathway antagonizes the activation of protein kinase C-alpha in murine Leydig cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1356: 221–228, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(96)00168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kushibiki M, Yamada M, Oikawa K, Tomita H, Osanai T, Okumura K. Aldosterone causes vasoconstriction in coronary arterioles of rats via angiotensin II type-1 receptor: influence of hypertension. Eur J Pharmacol 572: 182–188, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Langenickel TH, Buttgereit J, Pagel-Langenickel I, Lindner M, Monti J, Beuerlein K, Al-Saadi N, Plehm R, Popova E, Tank J, Dietz R, Willenbrock R, Bader M. Cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic rats expressing a dominant-negative mutant of the natriuretic peptide receptor B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 4735–4740, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510019103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Laragh J, Sealey J. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in hypertensive disorders: a key to two forms of arteriolar constriction and a possible clue to risk of vascular injury (heart attack and stroke and prognosis). New York: Raven Press, 1990, p. 1329–1348. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK. Natriuretic peptides. N Engl J Med 339: 321–328, 1998. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Levy D, DeStefano AL, Larson MG, O’Donnell CJ, Lifton RP, Gavras H, Cupples LA, Myers RH. Evidence for a gene influencing blood pressure on chromosome 17. Genome scan linkage results for longitudinal blood pressure phenotypes in subjects from the Framingham heart study. Hypertension 36: 477–483, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.36.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]