Abstract

An ethanolic extract of Artemisia scoparia (SCO) has metabolically favorable effects on adipocyte development and function in vitro and in vivo. In diet-induced obese mice, SCO supplementation significantly reduced fasting glucose and insulin levels. Given the importance of adipocyte lipolysis in metabolic health, we hypothesized that SCO modulates lipolysis in vitro and in vivo. Free fatty acids and glycerol were measured in the sera of mice fed a high-fat diet with or without SCO supplementation. In cultured 3T3-L1 adipocytes, the effects of SCO on lipolysis were assessed by measuring glycerol and free fatty acid release. Microarray analysis, qPCR, and immunoblotting were used to assess gene expression and protein abundance. We found that SCO supplementation of a high-fat diet in mice substantially reduces circulating glycerol and free fatty acid levels, and we observed a cell-autonomous effect of SCO to significantly attenuate tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-induced lipolysis in cultured adipocytes. Although several prolipolytic and antilipolytic genes were identified by microarray analysis of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue from SCO-fed mice, regulation of these genes did not consistently correlate with SCO’s ability to reduce lipolytic metabolites in sera or cell culture media. However, in the presence of TNFα in cultured adipocytes, SCO induced antilipolytic changes in phosphorylation of hormone-sensitive lipase and perilipin. Together, these data suggest that the antilipolytic effects of SCO on adipose tissue play a role in the ability of this botanical extract to improve whole body metabolic parameters and support its use as a dietary supplement to promote metabolic resiliency.

Keywords: adipocyte, Artemisia scoparia, botanical, lipolysis

INTRODUCTION

Once regarded simply as a storage site for excess energy, adipose tissue is now known to be a major regulator of metabolic health (32). Disruption of adipose tissue’s ability to store lipid or to respond to insulin, or dysregulation of its endocrine functions, have all been implicated in the metabolic dysfunction that accompanies obesity and type 2 diabetes (64). Adipose tissue lipolysis, the process by which adipocytes release fatty acids and glycerol into the circulation, occurs in response to a variety of stimuli, including fasting. Insulin resistance and obesity are often associated with abnormally high rates of basal lipolysis in the fed state, resulting in elevated circulating fatty acid levels that can further promote insulin resistance and impair metabolic functions in several tissues (41).

Plants have a long history of medicinal use in many cultures, and many modern pharmaceuticals have been developed from botanical sources. Screening efforts in our laboratory identified an ethanolic extract of Artemisia scoparia (SCO) that promotes adipocyte development in vitro (49). Subsequent studies revealed that SCO is a highly specific activator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) but not of any other nuclear receptor (47). In vivo, SCO, administered by oral gavage or through diet supplementation, exerts metabolically beneficial effects such as improved whole body insulin sensitivity and reduced circulating triglycerides and adiponectin, as well as many favorable effects on adipose tissue, including enhanced endocrine function and insulin signaling, and reduced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) levels, while producing no changes in body weight, food intake, body composition (47, 49, 65), fat pad weight independent of depot (observed, data not published), or de novo lipogenesis in liver or adipose tissue (52). In vitro, experiments in 3T3-L1 cells have also demonstrated SCO’s ability to enhance adipogenic differentiation and to reduce tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-induced changes in inflammatory gene expression and adipokine secretion (49). Given the important role of lipolysis in insulin resistance and metabolic health (41), we hypothesized that SCO might be able to modulate adipocyte lipolysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and extract preparation.

SCO was grown under common greenhouse conditions at Rutgers University and harvested as the total plant above soil level during late-stage flowering, when seeds are beginning to develop. The ethanolic extract used for diet formulation and cell culture experiments was prepared as previously reported (49). C57BL/6J diet-induced obese (DIO) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), housed, randomized, and fed as described (in Ref. 49) with Research Diets [New Brunswick, NJ; high-fat diet (HFD) D12492 (60% kcal as fat)] with or without 1% wt/wt SCO supplementation. Mice had ad libitum access to assigned diets and water for 4 wk. Two separate cohorts of mice from this feeding study were used. Treatment of the two cohorts differed only at the end of study on day 28/29 of defined diet feeding. For cohort 1, which was used for determination of circulating glycerol and fatty acids, on day 29, food was removed between 1200 and 1745, and lights were turned off at 1800. At 2200, animals were euthanized, and blood was collected. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 15 min, and the serum was separated, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C until time of analysis. For cohort 2, which was used for gene and protein expression analyses of adipose tissue (by microarray, qPCR, and immunoblotting), animals were euthanized on day 28, after a 4-h fast starting at 0630. All animal studies were approved by the Pennington Biomedical Research Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol no. 665P).

Serum fatty acids and glycerol.

Serum lipids were extracted using 2:1 chloroform-methanol based on the Folch method (12). After total lipid extraction, the chloroform layer was dried under nitrogen and resuspended in 1 ml of chloroform and 1 mL of 3N methanolic HCl. Tubes were incubated at 37°C overnight. After incubation, 2 ml of 5% NaCl and 3 ml of hexane were added to the tubes and vortexed. The top layer was used for fatty acid analysis, and the lower layer was used for glycerol analysis. The nonaqueous layer containing the fatty acids was dried under nitrogen and resuspended in hexane for GC-MS analysis. The aqueous phase containing the glycerol was processed using a series of cation and anion columns and then dried using a Speed Vac. The sample was then derivatized using 100 μl of pyridine:acetic anhydride (1:2). Samples were heated at 60°C for 30 min, dried under nitrogen, and then resuspended in ethyl acetate for analysis by GC-MS (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) (52).

Cell culture and lipolysis measurements.

Murine 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were grown and differentiated as previously described (6). Fully differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were pretreated in their regular medium [Dulbecco’s modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, GE Life Sciences, Logan, UT)] with 50 μg/ml SCO for 72–96 h and 0.5–0.75 nM TNFα (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for 16 h, or respective vehicle controls. Stock solutions were at 50 mg/ml in DMSO for SCO, and 0.5 μM in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich) for TNFα. In each case, equal volumes of stock solutions and their respective vehicles were used. After pretreatment, medium was removed, and cells were incubated in phenol red-free DMEM (Life Technologies) containing 0.1% glucose and 2% BSA for 2.5 h. Conditioned media were collected and assayed for glycerol by use of free glycerol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), or for nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) by use of a free fatty acid (FFA) quantification kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA). Absorbances were measured on a Versa Max spectrophotometer using Spectromax software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Microarray analysis of gene expression.

Inguinal (iWAT) and epididymal (eWAT) adipose tissue depots from mice fed a HFD with or without SCO supplementation for 4 wk (as described above) were harvested and flash-frozen. RNA was then purified using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and reverse transcribed using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Gene expression analysis of SCO-exposed compared with nonexposed samples was performed as described previously (26), using Illumina mouse expression arrays (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and following protocols specified by the manufacturer. Briefly, raw array data were extracted and processed by Limma software (51), which included background subtraction, identification of expressed genes, quantile normalization, and log2 transformation. Differentially expressed genes were identified through a Bayesian-moderated t-test (yielding Bayes-regularized P values), as implemented in CyberT software (29). Data were deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession no. GSE113808). Results were examined for effects of SCO on a list of 36 genes selected on the basis of literature searches for their involvement in lipolysis (shown in Table 1). Genes with P values below 0.05 were considered differentially expressed.

Table 1.

List of lipolysis-related genes used to query microarray data from SCO feeding study

| Gene Name | Gene Symbol | References* |

|---|---|---|

| Abhydrolase domain containing 5 | Abhd5 | (13) |

| Adenosine A1 receptor | Adora1 | (7) |

| Adenosine A2b receptor | Adora2b | (7) |

| Adrenoceptor alpha 1A | Adra1a | (13) |

| Adrenoceptor alpha 1B | Adra1b | (13) |

| Adrenoceptor alpha 2A | Adra2a | (13) |

| Adrenoceptor alpha 2B | Adra2b | (13) |

| Adrenoceptor alpha 2C | Adra2c | (13) |

| Adrenoceptor beta 1 | Adrb1 | (9, 18) |

| Adrenoceptor beta 2 | Adrb2 | (9, 18) |

| Adrenoceptor beta 3 | Adrb3 | (9, 18) |

| Aquaporin 7 | Aqp7 | (13) |

| Arrestin beta 1 | Arrb1 | (9, 28) |

| Caveolin 1 | Cav1 | (13) |

| Endothelin 1 | Edn1 | (25) |

| Free fatty acid receptor 2 | Ffar2 | (15) |

| G0/G1 switch 2 | G0s2 | (23) |

| Hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 | Hcar2 | (69) |

| Leptin | Lep | (19) |

| Lipase, hormone sensitive | Lipe | (9, 31) |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 8 | Map3k8 | (21) |

| Melanocortin 2 receptor | Mc2r | (40) |

| Melanocortin 5 receptor | Mc5r | (40) |

| Monoglyceride lipase | Mgll | (13) |

| Natriuretic peptide receptor 1 | Npr1 | (7) |

| Natriuretic peptide receptor 2 | Npr2 | (7) |

| Natriuretic peptide receptor 3 | Npr3 | (7) |

| OPA1, mitochondrial dynamin like gtpase | Opa1 | (10) |

| Phosphodiesterase 3b | Pde3b | (9, 45, 68) |

| Phosphodiesterase 4a | Pde4a | (34) |

| Phosphodiesterase 4b | Pde4b | (34) |

| Phosphodiesterase 4d | Pde4d | (34) |

| Phosphodiesterase 5 | Pde5 | (3) |

| Perilipin | Plin | (9, 53) |

| Patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 2 | Pnpla2 | (9, 31) |

| Succinate receptor 1 | Sucnr1 | (38) |

SCO, Artemisia scoparia.

References that refer to a gene as playing a role in lipolysis.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction gene expression analysis.

A subset of SCO-regulated genes identified in iWAT and eWAT by microarray analysis was validated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis using RNA prepared as described above. For in vitro studies, cells were harvested, and RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit. Reverse transcription was performed with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Takara SYBR premix (Takara Bio USA, Mountain View, CA) and primers from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Skokie, IL) were used to perform qPCR on the Applied Biosystems 7900 HT system with SDS 2.4 software (Applied Biosystems). Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, and 1 min at 60°C; dissociation stage: 15 s at 95°C, 15 s at 60°C, and 15 s at 95°C. Nono (non-POU domain containing octamer-binding protein) and Ppia (peptidylprolyl isomerase A) were used as reference genes. Primer sequences are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primer sequences for quantitative PCR gene expression analysis

| Gene Name (Symbol) | Forward Primer, 5′-3′ | Reverse Primer, 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclophilin A (Ppia) | CCACTGTCGCTTTTCGCCGC | TGCAAACAGCTCGAAGGAGACGC |

| Non-POU domain containing octamer binding protein (Nono) | CATCATCAGCATCACCACCA | TCTTCAGGTCAATAGTCAAGCC |

| Perilipin 1 (Plin1) | CGTGGAGAGTAAGGATGTCAATG | GTGCTGTTGTAGGTCTTCTGG |

| Phosphodiesterase 3b (Pde3b) | GTCGTTGCCTTGTATTTCCC | CAACTCCATTTCCACCTCCA |

| G0/G1 switch 2 (G0s2) | CAAAGCCAGTCTGACGCAA | CCTGCACACTTTCCATCTGA |

| Hormone-sensitive lipase (Lipe) | CTGCAAGAGTATGTCACGCTA | CTCGTTGCGTTTGTAGTGC |

| Patatin like phospholipase domain containing 2 (Pnpla2/Atgl) | GAGCTCATCCAGGCCAAT | CTCATAAAGTGGCAAGTTGTCTG |

| Adrenergic receptor, beta 3 (Adrb3) | CCACCGCTCAACAGGTTT | CCAGAAGTCCTGCAAAAACG |

Whole cell extract preparation.

Adipocyte monolayers from experiments described above were harvested in a buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 1 M ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1% Triton X-100; 0.5% Igepal CA-630, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μM pepstatin, 50 trypsin inhibitory milliunits of aprotinin, 10 μM leupeptin, 1 mM 10-phenanthroline, and 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate. Lysates were subjected to one freeze-thaw cycle, passed through a 20-gauge needle three times, and then centrifuged at 17,500 g at 4°C for 10 min. Supernatants were recovered, and protein content was measured by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Sigma-Aldrich).

Gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

Protein (100 μg/well) was loaded onto 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were probed and imaged using standard immunoblotting techniques and detected using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) and SuperSignal West Pico PLUS detection reagents (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Polyclonal rabbit antibodies against hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), phospho-HSL (Ser563, Ser565, or Ser660), and perilipin, as well as a mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin, were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA; catalog nos. 4107, 4139, 4137, 4126, 3470, and 3700, respectively). A mouse monoclonal antibody against phospho-perilipin (human Ser522/mouse Ser517) was obtained from Vala Sciences (San Diego, CA; catalog no. 4856). Autoradiography films were scanned, and densitometry was performed using Image Studio software (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Statistics.

GraphPad Prism 6 for Windows software (La Jolla, CA) was used to calculate means and SE, produce graphs, and determine statistical significance using unpaired two-tailed t-tests or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Threshold for significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

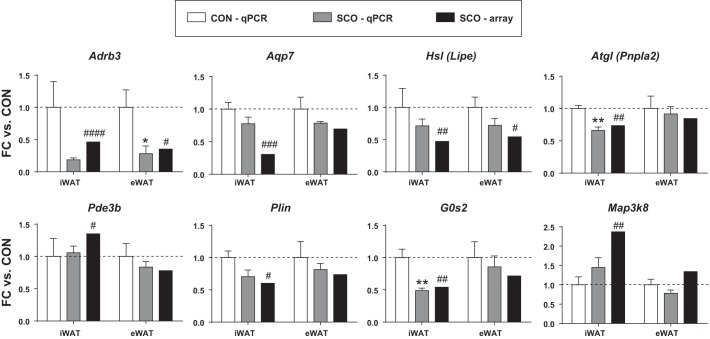

On the basis of our previous studies, we hypothesized that SCO might affect another important metabolic pathway in adipose tissue, namely lipolysis. First, we examined the levels of FFAs and glycerol in serum of mice fed HFD (60% kcal as fat) for 4 wk in the presence or absence of 1% (wt/wt) of SCO extract. As shown in Fig. 1, supplementation with SCO significantly reduced the circulating levels of glycerol and of all fatty acids measured (C18:0, C18:1, C16:0, C16:1), suggesting that SCO may have direct effects on adipose tissue to reduce lipolysis.

Fig. 1.

Artemisia scoparia (SCO) supplementation in high-fat diet (HFD) reduces circulating levels of free fatty acids and glycerol. C57BL/6 diet-induced obese (DIO) mice were fed a HFD supplemented with 1% wt/wt SCO (SCO) or without (CON) ad libitum for 4 wk. Mice were fasted for 4 h, food was returned to the cages, and mice were euthanized 4 h later. Serum lipids and glycerol were extracted and analyzed by GC-MS. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 5 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

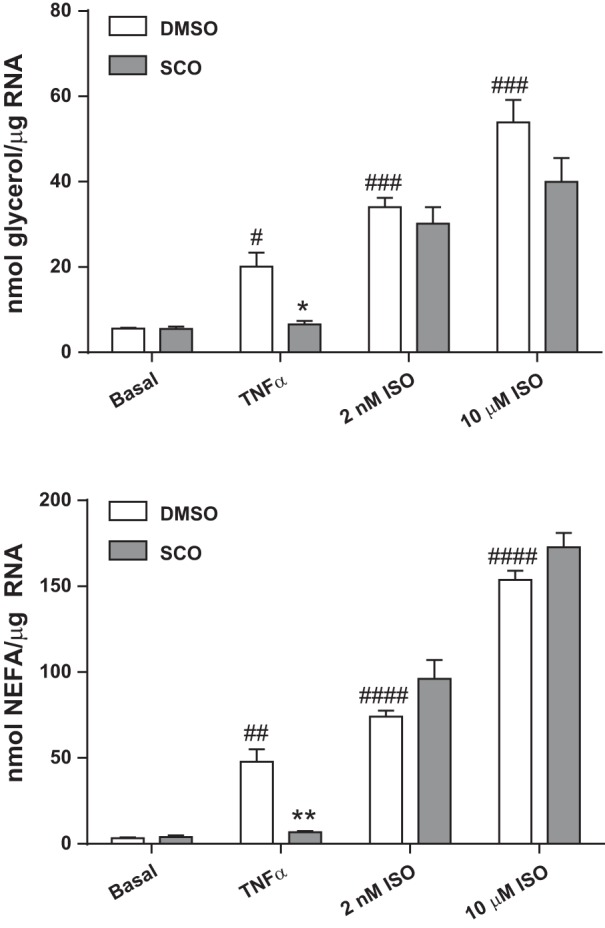

The relationships between inflammation, lipolysis, and insulin resistance (11, 27, 44) prompted us to examine whether SCO could affect lipolysis under basal and induced conditions in a cell-autonomous manner in adipocytes. We stimulated lipolysis either with TNFα or by β-adrenergic stimulation with isoproterenol in murine 3T3-L1 adipocytes. As shown in Fig. 2, TNFα and isoproterenol strongly induced lipolysis, as measured by both glycerol and FFA release into the culture medium. Chronic pretreatment (72 h) with SCO had no significant effects on basal or isoproterenol-induced lipolysis, but significantly attenuated the effect of TNFα.

Fig. 2.

Artemisia scoparia (SCO) reduces tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-induced, but not isoproterenol (ISO)-induced or basal lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes, cultured in 6-well plates, were pretreated for 3 days with SCO at 50 μg/ml and overnight with 0.75 nM TNFα or equal volumes of their vehicles (DMSO or 0.1% BSA in PBS, respectively). Culture medium was replaced with lipolysis incubation medium containing 0 or 2 nM or 10 μM ISO. Medium was assayed for glycerol and nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) concentrations after 2.5 h, and resulting concentrations were corrected for total RNA measured in harvested cells. Data are displayed as means ± SE; n = 3 replicate cell culture wells per condition. Significance denoted as *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (for SCO treatment vs. DMSO control); #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 (for TNFα or ISO treatment vs. basal). Data shown are representative of an experiment that was repeated 2 (for the ISO treatments) or 3 times (for the TNFα treatment).

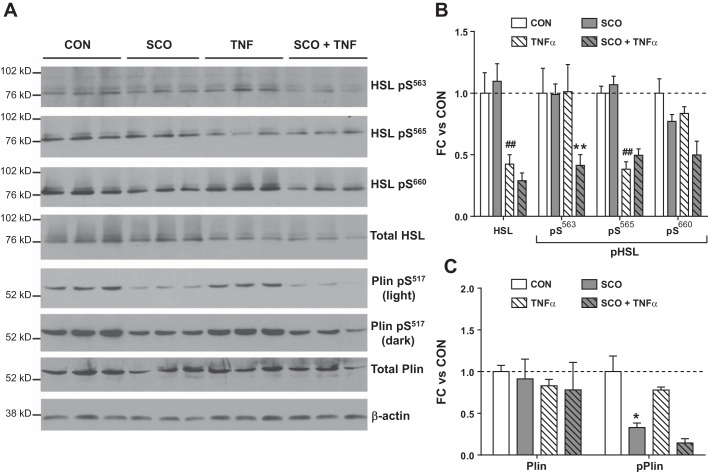

To investigate the potential mechanisms by which SCO may be modulating lipolysis, we performed microarray analysis on visceral eWAT and subcutaneous iWAT samples from male mice fed a HFD with or without SCO supplementation. The resulting data were examined for effects of SCO on 36 genes known to be involved in lipolysis. The list of genes queried is shown in Table 1; genes from this list found to be regulated by SCO (P < 0.05; 10 in iWAT, 8 in eWAT), and their corresponding fold changes, are shown in Table 3. Expression of some of these genes was regulated in a manner that would be expected to reduce lipolysis. For example, Lipe/Hsl and Adrb3 (β3-adrenergic receptor) are both downregulated in iWAT and eWAT, and Pde3b is downregulated in iWAT. However, the effect of SCO on other genes could be considered prolipolytic. One example is the reduced expression of G0s2 in iWAT. A subset of the SCO-regulated genes was analyzed by qPCR to validate the microarray results (Fig. 3). All genes evaluated were regulated in the same direction as observed in the microarray analysis, although not all of the SCO-induced changes were statistically significant when analyzed by qPCR.

Table 3.

SCO supplementation in high-fat diet significantly modulates the expression of several lipolysis-related genes

| iWAT |

eWAT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | FC | P Value | Gene | FC | P Value |

| Antilipolytic regulation | |||||

| Adrb3 | −2.83 | 7.58E-05 | Mgll | −2.15 | 1.26E-03 |

| Aqp7 | −3.28 | 1.05E-04 | Adrb3 | −2.16 | 0.022 |

| Lipe | −2.11 | 1.58E-03 | Lipe | −1.83 | 0.041 |

| Pnpla2 | −1.36 | 5.60E-03 | Arrb1 | −1.41 | 0.045 |

| Pde4a | 1.33 | 0.014 | |||

| Pde3b | 1.35 | 0.031 | |||

| Prolipolytic regulation | |||||

| Plin | −1.66 | 0.014 | Adcy9 | −1.96 | 3.42E-03 |

| Npr3 | 2.70 | 2.77E-03 | Adrb2 | 1.37 | 0.034 |

| G0s2 | −1.85 | 2.81E-03 | Pde4b | −1.28 | 0.043 |

| Map3k8 | 2.37 | 3.65E-03 | |||

Diet-induced obese (DIO) mice were fed a high-fat diet with or without supplementation with 1% wt/wt Artemisia scoparia (SCO) for 4 wk (n = 4 mice per group). Mice were euthanized, and adipose tissue depots were harvested and flash-frozen. RNA was purified, and gene expression was analyzed by microarray. Results were examined for effects of SCO on 36 genes involved in lipolysis, based on literature searches. Genes significantly regulated by SCO (P < 0.05) in inguinal (iWAT) and epididymal (eWAT) white adipose tissue are shown along with their respective fold changes (FC) relative to controls and P value. Genes are separated based on whether the direction of observed change would be expected to repress (antilipolytic regulation) or induce (prolipolytic regulation) lipolysis.

Fig. 3.

qPCR validation of Artemisia scoparia (SCO)-regulated genes identified in microarray analysis. For validation, RNA isolated for microarray analysis was reverse transcribed, and resulting cDNA was analyzed by qPCR. Target gene data were normalized to reference genes Ppia and Nono. Data are plotted as fold change (FC) vs. control (CON); qPCR data are presented as means ± SE; n = 5 mice per group. Significance denoted as #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001 (for effect of SCO in microarray analysis); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (for effect of SCO as measured by qPCR).

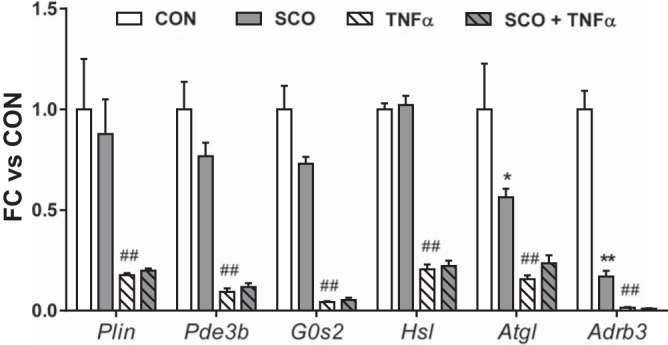

Stimulation of lipolysis by TNFα is associated with the inhibition of several antilipolytic genes including Plin, Pde3b, and G0s2 (23, 45, 67). Hence, we measured the effects of TNFα and SCO on the expression of these genes in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. As shown in Fig. 4, we observed the expected reductions in expression with TNFα treatment. However, SCO did not reverse these changes, suggesting that the effect of SCO on TNFα-mediated lipolysis is likely independent of the transcriptional regulation of these genes. Although TNFα produces robust activation of lipolysis, it has also been shown to reduce the expression of genes coding for proteins that promote lipolysis, such as Adrb3, Lipe/Hsl, and Pnpla2/Atgl (18, 23, 31). In our experiments, TNFα treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes produced the expected reductions in expression of these genes, but the only significant effects of SCO on these genes were reductions in Atgl and Adrb3 in the absence of TNFα. Although these effects would be considered antilipolytic, they cannot explain the effect of SCO on lipolysis, since SCO had no effect on lipolysis in the absence of TNFα. Moreover, reduction in adrenergic signaling would also be expected to reduce isoproterenol-induced lipolysis, which did not occur with SCO treatment. Conversely, in the presence of TNFα, where SCO does reduce lipolysis it had no effect on Atgl or Adrb3 expression (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Artemisia scoparia (SCO) does not reverse tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-induced changes in the expression of genes involved in lipolysis. Differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were pretreated for 3–4 days with SCO at 50 μg/ml and/or 0.5 to 0.75 nM TNFα or an equal volume of their respective vehicles (DMSO or 0.1% BSA in PBS). Control (CON) wells were treated with both vehicles. Cells were harvested, and RNA was isolated, reverse transcribed, and subjected to qPCR. Target gene data were normalized to the reference gene Nono. Data are displayed as means ± SE; n = 3 replicate cell culture wells per condition. Significance denoted as *P < 0.01, **P < 0.0001 (for SCO treatment vs. CON); ##P < 0.0001 (for TNFα treatment vs. CON). These data are representative of an experiment performed in duplicate.

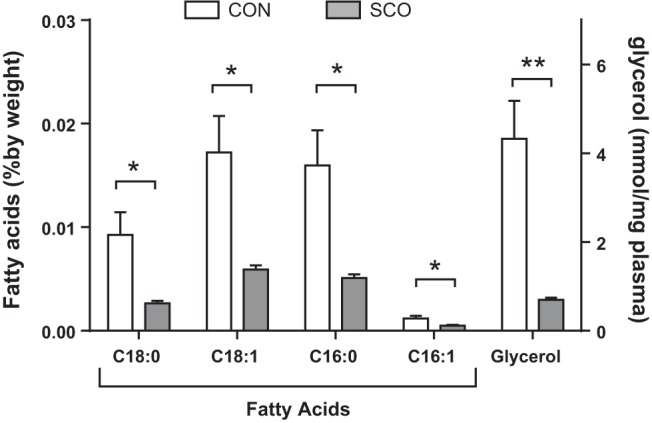

Since lipolysis rates are largely determined by posttranscriptional and posttranslational regulation of lipolytic and lipid droplet-associated proteins (reviewed in Ref. 13), we examined the effects of SCO on perilipin and HSL protein levels and phosphorylation. Consistent with our gene expression studies (Figs. 3 and 4), we observed that TNFα reduced HSL protein levels and that SCO did not significantly modulate HSL levels (Fig. 5A). However, SCO treatment was associated with altered phosphorylation of two serine residues (Ser563 and Ser660) in HSL known to increase the enzyme’s activity and lipolysis rates (1, 16, 56). Although TNFα reduced total HSL levels, it did not alter the amount of HSL phosphorylated at Ser563 (HSL pSer563). These observations are consistent with reported actions of TNFα to increase both HSL phosphorylation and lipolysis despite reductions in total HSL levels (36, 59, 68, 70). Although SCO had no effect on HSL pSer563 in unstimulated conditions, it reduced HSL pSer563 in the presence of TNFα. A similar pattern was observed with the other prolipolytic phosphorylation site that we examined, HSL pSer660 (Fig. 5, A and B). We also studied the phosphorylation of HSL at Ser565, which inhibits phosphorylation of HSL at Ser563 and is associated with decreased HSL activity (2, 14, 30). TNFα produced a significant reduction in the amount of HSL pSer565, but we did not observe any modulation by SCO. Perilipin is a major regulator of lipolysis, as it controls access of HSL to the lipid droplet, and its phosphorylation is a potent inducer of lipolysis (39, 63). As shown in the bottom panels of Fig. 5A and C, SCO had no effect on total perilipin protein levels but produced a striking reduction in its phosphorylation at Ser517, a prolipolytic modification. In Fig. 5, B and C, bands shown in Fig. 5A were quantitated by densitometry, and normalized to the loading control, β-actin.

Fig. 5.

Artemisia scoparia (SCO) induces antilipolytic changes in phosphorylation of hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and perilipin. Differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were pretreated for 3 days with SCO at 50 μg/ml and overnight with 0.75 nM tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) or equal volumes of their vehicles (DMSO or 0.1% BSA in PBS, respectively). Control (CON) wells were treated with both vehicles. Culture medium was replaced with lipolysis incubation medium for 2.5 h for glycerol and nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) measurements, and then cells were harvested and whole cell extracts were prepared; 100 μg total protein per well were loaded for Western blot analysis. Blot images are shown in A. The HSL Ser563 and Ser660 phosphorylation sites are associated with enhanced lipolysis, whereas phosphorylation at Ser565 is antilipolytic. B and C: band intensities were quantified by densitometry. All bands were normalized to the loading control (β−actin). Data are expressed as means ± SE fold change (FC) vs. CON (basal conditions). Significance denoted as ##P < 0.01 (for effect of TNFα vs. CON), and *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (for effect of SCO vs CON or TNFα only); n = 3 replicate wells per condition.

DISCUSSION

An ethanolic extract of A. scoparia (SCO) was originally identified in a screen of botanical extracts that modulated adipocyte development in vitro and was later shown to have metabolically beneficial effects on whole body insulin sensitivity and on adipose tissue function (47, 49). Given the important role of lipolysis in insulin resistance (22) and the favorable effects of SCO on insulin sensitivity in vivo, we hypothesized that SCO might regulate lipolysis. Our studies revealed that SCO inhibits the levels of both glycerol and FFAs (NEFAs) both in vivo and in vitro. Mice fed a HFD supplemented with SCO had significantly lower serum levels of glycerol and all the NEFAs that we examined compared with HFD controls without SCO supplementation (Fig. 1). These results suggested that SCO likely reduces lipolysis in adipose tissue and might affect adipocytes directly. In addition to these in vivo observations, we found that SCO attenuated TNFα-induced lipolysis but did not substantially affect basal or isoproterenol-induced release of glycerol and NEFAs in cultured 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Fig. 2).

The association of TNFα and adipose tissue inflammation is well documented. TNFα not only promotes insulin resistance by decreasing the expression of GLUT4 (61), the insulin receptor, and IRS-1 (60) but also is a potent stimulator of lipolysis (27). In conditions of obesity and insulin resistance, TNFα can be produced in adipose tissue macrophages and act in a paracrine manner on adjacent adipocytes to promote metabolic dysfunction, enhance basal lipolysis, and raise circulating fatty acid levels (11). Increased TNFα and circulating levels of FFAs and their association with insulin resistance have also been documented in a clinical study (44). Hence, the ability of SCO to attenuate TNFα-stimulated lipolysis has relevance in the context of obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

To investigate the potential mechanisms involved in the ability of SCO to regulate lipolysis, we performed microarray analysis and examined the expression of lipolysis-related genes (Table 1) in both subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue samples from an animal study where mice were fed SCO for 4 wk in the presence of a HFD. This analysis yielded equivocal results. Specifically, few genes were significantly regulated by SCO; however, not all genes that were altered by SCO were changed in a manner expected to reduce lipolysis (Table 3). There are several factors that could account for our observations. First, lipolysis rates are highly regulated at the protein level through mechanisms such as phosphorylation and protein stability (43). Although we validated our array results with qPCR (Fig. 3), it is known that gene expression is not always reflective of protein levels or activity. Another consideration is that, although adipocytes are the prominent cell type found in adipose tissue, fat tissue is composed of many other cell types (preadipocytes, immune cells such as lymphocytes and macrophages, and others). Therefore, the gene expression measured in adipose tissue samples reflects mRNA levels in all adipose tissue cell types. The effects of SCO on gene expression in nonadipocytes may account for some of our microarray observations (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Of the lipolytic genes that we examined in cultured adipocytes, only Adrb3 was modulated by SCO, but only in the absence of TNFα, a condition in which we did not observe effects of SCO on lipolysis.

In cultured adipocytes, TNFα affects the expression and posttranslational modifications of proteins known to regulate lipolysis (reviewed in Refs. 13, 55). Hence, we also examined the effects of TNFα and SCO on HSL and perilipin expression and phosphorylation (Fig. 5). As previously documented, TNFα reduced HSL levels (59) even though it enhanced lipolysis. SCO did not significantly modulate HSL levels but did alter the phosphorylation of two serine residues in HSL known to increase the enzyme’s activity and lipolysis rates (1, 16, 56). Although TNFα reduced total HSL levels, it did not affect phosphorylation of HSL Ser563. Our studies are consistent with evidence that TNFα increases HSL phosphorylation and lipolysis despite its ability to reduce total HSL levels (36, 59, 68, 70). While SCO alone had no effect on HSL pS563 in basal conditions, phosphorylation at this residue was reduced in the presence of TNFα. A similar pattern was observed with the other prolipolytic phosphorylation site, HSL Ser660. The phosphorylation of HSL at Ser565 inhibits activation of HSL and is associated with decreased HSL activity (2, 14, 30). Although TNFα produced a significant reduction in the amount of HSL pSer565, we did not observe any modulation by SCO. In terms of HSL, our studies suggest that SCO does not impact HSL protein levels but can reduce the TNFα-induced activation of the prolipolytic phosphorylation at Ser563 and Ser660. Perilipin regulates lipolysis by controlling access of HSL to the lipid droplet, and its phosphorylation strongly induces lipolysis (39, 63). Our studies demonstrated that SCO had no effect on total perilipin protein levels but produced a striking reduction in its prolipolytic phosphorylation at Ser517 (Fig. 5, A and C). Phosphorylation at this site has also been shown to be important in human perilipin at Ser522 (62). Clearly, SCO treatment could affect the ability of TNFα to regulate lipolysis by modulating the phosphorylation of known serine residues in HSL and perilipin. Previous work from our laboratory has shown that SCO activates the nuclear receptor PPARγ and modulates expression of its target genes, which, in turn, enhance adipocyte differentiation (47, 49). Effects of SCO on lipolysis presented in our current study appear to be largely mediated by posttranslational events rather than at the transcriptional level. Interestingly, inhibition of PPARγ has been shown to be involved in mediating TNFα’s ability to stimulate lipolysis, and PPARγ agonists inhibit TNFα-induced lipolysis (23, 57, 59). In addition, the ability of pioglitazone (a PPARγ agonist) to inhibit TNFα’s effect on lipolysis is independent of PPARγ’s adipogenic activity (20). This raises the possibility that SCO’s effects on adipogenesis and on TNFα-induced lipolysis may both be dependent on PPARγ activation.

Recently, SCO has been reported to have anti-inflammatory effects in human mast cells by reducing the levels of TNFα and other inflammatory cytokines (42). These studies also showed that SCO and one of its constituents, 3,5-dicaffeoyl-epi-quinic acid, could reduce the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). Our studies revealed that SCO attenuated only TNFα-induced lipolysis and not basal or adrenergic-induced lipolysis in cultured adipocytes (Fig. 2). Various mechanisms have been implicated in the ability of TNFα to induce lipolysis, including impairment of insulin signaling (9, 33), repression of the antilipolytic protein G0S2 (23), modulation of the micro-RNA miR-145 (37), and the induction of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (57), as well as the regulation of cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector c, also known as fat-specific protein-27 (CIDEC/FSP27) (46). Our measurements of circulating glycerol and fatty acids were made in the fed state, when insulin levels are high. Given that insulin is a potent inhibitor of lipolysis, the insulin-sensitizing effects of SCO in vivo are likely to contribute to its effects on lipolysis; however our observation that TNFα-induced lipolysis in cultured adipocytes is reduced by SCO in the absence of insulin suggests that SCO may act, at least in part, through insulin-independent mechanisms. Related to our observations, a study in human adipocytes has shown that a peptide inhibitor of IKK (IκB kinase) activation effectively blocks the TNFα-mediated nuclear translocation of NF-κB (35). Notably, these studies also show that the ability of TNFα to induce lipolysis is dependent on NF-κB activation (35). Collectively, these reports and our results suggest that the ability of SCO to attenuate TNFα-induced lipolysis in cultured adipocytes may also be related to modulation of NF-κB activity. Our in vivo microarray analysis (Table 3), coupled with our in vitro adipocyte studies (Fig. 4), suggest that modulation of G0S2, a protein that reduces lipolysis, is not involved in the ability of SCO to reduce TNFα-induced lipolysis. Additional studies in cultured adipocytes indicate that siRNA knockdown of G0S2 did not affect the ability of SCO to regulate lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (data not shown). Published studies by other laboratories showing that either anti-inflammatory effects of SCO (17, 42) or effects of TNFα on lipolysis are dependent on NF-κB (35) are supportive of our novel data implicating a potential role of NF-κB in the actions of SCO on adipocytes. Future studies could be performed to demonstrate a role of NF-κB in this regulation, but these studies will be challenging as loss of NF-κB expression or activation affects a variety of adipocyte signaling and inflammatory pathways. To complicate these investigations, there are likely several mechanisms involved in the ability of SCO to abrogate TNFα-induced lipolysis in adipocytes.

Our in vivo studies were performed on HFD-fed mice, in conditions that are known to promote inflammation in adipose tissue (49). It should be noted that, although we have not directly examined macrophage numbers in adipose tissue, our microarray analysis, as well as unpublished experiments, have produced no compelling evidence that SCO reduces macrophage infiltration or activation, but rather that SCO attenuates the response to inflammatory signals in adipocytes. As our in vitro experiments demonstrate, SCO treatment of cultured adipocytes renders them less responsive to TNFα, the primary macrophage-derived inflammatory mediator in adipose tissue (4, 8), and these results are consistent with an in vivo scenario in which SCO may reduce inflammatory responses in adipocytes in the absence of any effects on macrophage numbers or function. Additional studies would be needed to definitively address the question of whether SCO treatment can alter macrophage infiltration or activation in adipose tissue.

In conclusion, our studies have revealed that an extract of SCO known to have positive effects on various metabolic parameters in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity (47, 49) can also reduce serum levels of NEFAs and glycerol (Fig. 1). Lipolysis is one of several metabolically important functions of adipose tissue, and it is well known that obesity/type 2 diabetes is often associated with elevated rates of lipolysis accompanied by increased circulating levels of glycerol and FFAs (41). Notably, antilipolytic agents, such as acipimox and atglistatin, have been proposed as viable therapeutic strategies for improving insulin sensitivity and dyslipidemia (5, 24). Although our observations do not necessarily indicate a direct effect of SCO on adipose tissue lipolysis, our results support this notion and collectively indicate that the ability of SCO to promote metabolic resiliency likely occurs, at least in part, through its ability to reduce TNFα-regulated lipolysis. Direct assessment of lipolytic activity from adipose tissue explants ex vivo will be required to confirm that diet supplementation with SCO reduces lipolysis and to determine any depot-specific differences in the effects of SCO. Depot-specific differences could also potentially be assessed through in vitro treatment of primary adipocytes. Further characterization of TNFα-induced lipolysis and its reduction by SCO will also be needed to identify the mechanisms by which SCO antagonizes TNFα action. In addition, future studies should include efforts to identify the bioactive compounds present in SCO that regulate lipolysis and to elucidate other mechanisms involved in the ability of SCO to promote metabolic health. We propose that the global epidemics of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome (54) could potentially be tackled by a greater consideration of botanical-based interventions.

GRANTS

This research project used Genomics Core facilities that are supported in part by COBRE (National Institute of General Medical Sciences 8 P20 GM-103528) and NORC (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 2 P30 DK-072476) center grants from the NIH. This publication was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health and the Office of Dietary Supplements of the NIH under Award Number P50 AT-002776, which funds the Botanical Dietary Supplements Research Center of Pennington Biomedical Research Center and the Department of Plant Biology and Pathology in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences of Rutgers University.

DISCLAIMERS

The content in this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

The funding sponsor had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.B. and J.M. Stephens conceived and designed research; A.B., J.A.B., W.T.K., R.D., J.-M.S., D.M.R., J.R., and J.M. Salbaum performed experiments; A.B., J.A.B., W.T.K., R.D., J.-M.S., J.R., and J.M. Salbaum analyzed data; A.B., A.J.R., and J.M. Stephens interpreted results of experiments; A.B., A.J.R., and J.A.B. prepared figures; A.B. and J.M. Stephens drafted manuscript; A.B., A.J.R., J.A.B., D.M.R., J.R., J.M. Salbaum, and J.M. Stephens edited and revised manuscript; A.B., A.J.R., J.A.B., W.T.K., R.D., J.-M.S., D.M.R., J.R., J.M. Salbaum, and J.M. Stephens approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tamra Mendoza for technical contributions to the animal study, Hardy Hang for technical assistance, and Susan Newman for analysis of microarray data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthonsen MW, Rönnstrand L, Wernstedt C, Degerman E, Holm C. Identification of novel phosphorylation sites in hormone-sensitive lipase that are phosphorylated in response to isoproterenol and govern activation properties in vitro. J Biol Chem 273: 215–221, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony NM, Gaidhu MP, Ceddia RB. Regulation of visceral and subcutaneous adipocyte lipolysis by acute AICAR-induced AMPK activation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17: 1312–1317, 2009. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armani A, Marzolla V, Rosano GMC, Fabbri A, Caprio M. Phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) in the adipocyte: a novel player in fat metabolism? Trends Endocrinol Metab 22: 404–411, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai Y, Sun Q. Macrophage recruitment in obese adipose tissue. Obes Rev 16: 127–136, 2015. doi: 10.1111/obr.12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bays H, Stein EA. Pharmacotherapy for dyslipidaemia—current therapies and future agents. Expert Opin Pharmacother 4: 1901–1938, 2003. doi: 10.1517/14656566.4.11.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudreau A, Fuller S, Ribnicky DM, Richard AJ, Stephens JM. Groundsel bush (Baccharis halimifolia) extract promotes adipocyte differentiation in vitro and increases adiponectin expression in mature adipocytes. Biology (Basel) 7: E22, 2018. doi: 10.3390/biology7020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun K, Oeckl J, Westermeier J, Li Y, Klingenspor M. Non-adrenergic control of lipolysis and thermogenesis in adipose tissues. J Exp Biol 221, Suppl 1: jeb165381, 2018. doi: 10.1242/jeb.165381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caër C, Rouault C, Le Roy T, Poitou C, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Torcivia A, Bichet J-C, Clément K, Guerre-Millo M, André S. Immune cell-derived cytokines contribute to obesity-related inflammation, fibrogenesis and metabolic deregulation in human adipose tissue. Sci Rep 7: 3000, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02660-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cawthorn WP, Sethi JK. TNF-α and adipocyte biology. FEBS Lett 582: 117–131, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu D-T, Tao Y, Taskén K. OPA1 in lipid metabolism: function of OPA1 in lipolysis and thermogenesis of adipocytes. Horm Metab Res 49: 276–285, 2017. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-100384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engin A. The pathogenesis of obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Adv Exp Med Biol 960: 221–245, 2017. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226: 497–509, 1957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frühbeck G, Méndez-Giménez L, Fernández-Formoso J-A, Fernández S, Rodríguez A. Regulation of adipocyte lipolysis. Nutr Res Rev 27: 63–93, 2014. doi: 10.1017/S095442241400002X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garton AJ, Yeaman SJ. Identification and role of the basal phosphorylation site on hormone-sensitive lipase. Eur J Biochem 191: 245–250, 1990. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge H, Li X, Weiszmann J, Wang P, Baribault H, Chen J-L, Tian H, Li Y. Activation of G protein-coupled receptor 43 in adipocytes leads to inhibition of lipolysis and suppression of plasma free fatty acids. Endocrinology 149: 4519–4526, 2008. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg AS, Shen W-J, Muliro K, Patel S, Souza SC, Roth RA, Kraemer FB. Stimulation of lipolysis and hormone-sensitive lipase via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 276: 45456–45461, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habib M, Waheed I. Evaluation of anti-nociceptive, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activities of Artemisia scoparia hydromethanolic extract. J Ethnopharmacol 145: 18–24, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadri KE, Courtalon A, Gauthereau X, Chambaut-Guérin AM, Pairault J, Fève B. Differential regulation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha of beta1-, beta2-, and beta3-adrenoreceptor gene expression in 3T3-F442A adipocytes. J Biol Chem 272: 24514–24521, 1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris RBS. Direct and indirect effects of leptin on adipocyte metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842: 414–423, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwata M, Haruta T, Usui I, Takata Y, Takano A, Uno T, Kawahara J, Ueno E, Sasaoka T, Ishibashi O, Kobayashi M. Pioglitazone ameliorates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced insulin resistance by a mechanism independent of adipogenic activity of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-gamma. Diabetes 50: 1083–1092, 2001. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jager J, Grémeaux T, Gonzalez T, Bonnafous S, Debard C, Laville M, Vidal H, Tran A, Gual P, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Cormont M, Tanti J-F. Tpl2 kinase is upregulated in adipose tissue in obesity and may mediate interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha effects on extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and lipolysis. Diabetes 59: 61–70, 2010. doi: 10.2337/db09-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen MD. Adipose tissue metabolism – an aspect we should not neglect? Horm Metab Res 39: 722–725, 2007. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-990274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin D, Sun J, Huang J, He Y, Yu A, Yu X, Yang Z. TNF-α reduces g0s2 expression and stimulates lipolysis through PPAR-γ inhibition in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Cytokine 69: 196–205, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin J, Huang S, Wang L, Leng Y, Lu W. Design and synthesis of Atglistatin derivatives as adipose triglyceride lipase inhibitors. Chem Biol Drug Des 90: 1122–1133, 2017. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juan C-C, Chang C-L, Lai Y-H, Ho L-T. Endothelin-1 induces lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288: E1146–E1152, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00481.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kappen C, Salbaum JM. Gene expression in teratogenic exposures: a new approach to understanding individual risk. Reprod Toxicol 45: 94–104, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawakami M, Murase T, Ogama H, Ishibashi S, Mori N, Takaku F, Shibata S. Human recombinant TNF suppresses lipoprotein lipase activity and stimulates lipolysis in 3T3-L1 cells. J Biochem 101: 331–338, 1987. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a121917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawamata Y, Imamura T, Babendure JL, Lu J-C, Yoshizaki T, Olefsky JM. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 can function through a G alpha q/11-beta-arrestin-1 signaling complex. J Biol Chem 282: 28549–28556, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kayala MA, Baldi P. Cyber-T web server: differential analysis of high-throughput data. Nucleic Acids Res 40: W553–W559, 2012. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim S-J, Tang T, Abbott M, Viscarra JA, Wang Y, Sul HS. AMPK Phosphorylates Desnutrin/ATGL and Hormone-Sensitive Lipase To Regulate Lipolysis and Fatty Acid Oxidation within Adipose Tissue. Mol Cell Biol 36: 1961–1976, 2016. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00244-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kralisch S, Klein J, Lossner U, Bluher M, Paschke R, Stumvoll M, Fasshauer M. Isoproterenol, TNFalpha, and insulin downregulate adipose triglyceride lipase in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 240: 43–49, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kusminski CM, Bickel PE, Scherer PE. Targeting adipose tissue in the treatment of obesity-associated diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov 15: 639–660, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langin D, Arner P. Importance of TNFalpha and neutral lipases in human adipose tissue lipolysis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 17: 314–320, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsson S, Jones HA, Göransson O, Degerman E, Holm C. Parathyroid hormone induces adipocyte lipolysis via PKA-mediated phosphorylation of hormone-sensitive lipase. Cell Signal 28: 204–213, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laurencikiene J, van Harmelen V, Arvidsson Nordström E, Dicker A, Blomqvist L, Näslund E, Langin D, Arner P, Rydén M. NF-kappaB is important for TNF-alpha-induced lipolysis in human adipocytes. J Lipid Res 48: 1069–1077, 2007. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600471-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lien C-C, Au L-C, Tsai Y-L, Ho L-T, Juan C-C. Short-term regulation of tumor necrosis factor-α-induced lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is mediated through the inducible nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide-dependent pathway. Endocrinology 150: 4892–4900, 2009. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorente-Cebrián S, Mejhert N, Kulyté A, Laurencikiene J, Åström G, Hedén P, Rydén M, Arner P. MicroRNAs regulate human adipocyte lipolysis: effects of miR-145 are linked to TNF-α. PLoS One 9: e86800, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCreath KJ, Espada S, Gálvez BG, Benito M, de Molina A, Sepúlveda P, Cervera AM. Targeted disruption of the SUCNR1 metabolic receptor leads to dichotomous effects on obesity. Diabetes 64: 1154–1167, 2015. doi: 10.2337/db14-0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyoshi H, Souza SC, Zhang HH, Strissel KJ, Christoffolete MA, Kovsan J, Rudich A, Kraemer FB, Bianco AC, Obin MS, Greenberg AS. Perilipin promotes hormone-sensitive lipase-mediated adipocyte lipolysis via phosphorylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem 281: 15837–15844, 2006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Møller CL, Raun K, Jacobsen ML, Pedersen TÅ, Holst B, Conde-Frieboes KW, Wulff BS. Characterization of murine melanocortin receptors mediating adipocyte lipolysis and examination of signalling pathways involved. Mol Cell Endocrinol 341: 9–17, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morigny P, Houssier M, Mouisel E, Langin D. Adipocyte lipolysis and insulin resistance. Biochimie 125: 259–266, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nam S-Y, Han N-R, Rah S-Y, Seo Y, Kim H-M, Jeong H-J. Anti-inflammatory effects of Artemisia scoparia and its active constituent, 3,5-dicaffeoyl-epi-quinic acid against activated mast cells. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 40: 52–58, 2018. doi: 10.1080/08923973.2017.1405438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nielsen TS, Jessen N, Jørgensen JOL, Møller N, Lund S. Dissecting adipose tissue lipolysis: molecular regulation and implications for metabolic disease. J Mol Endocrinol 52: R199–R222, 2014. doi: 10.1530/JME-13-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohmura E, Hosaka D, Yazawa M, Tsuchida A, Tokunaga M, Ishida H, Minagawa S, Matsuda A, Imai Y, Kawazu S, Sato T. Association of free fatty acids (FFA) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and insulin-resistant metabolic disorder. Horm Metab Res 39: 212–217, 2007. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahn Landström T, Mei J, Karlsson M, Manganiello V, Degerman E. Down-regulation of cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterase 3B in 3T3-L1 adipocytes induced by tumour necrosis factor alpha and cAMP. Biochem J 346: 337–343, 2000. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3460337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ranjit S, Boutet E, Gandhi P, Prot M, Tamori Y, Chawla A, Greenberg AS, Puri V, Czech MP. Regulation of fat specific protein 27 by isoproterenol and TNF-α to control lipolysis in murine adipocytes. J Lipid Res 52: 221–236, 2011. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M008771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richard AJ, Burris TP, Sanchez-Infantes D, Wang Y, Ribnicky DM, Stephens JM. Artemisia extracts activate PPARγ, promote adipogenesis, and enhance insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue of obese mice. Nutrition 30, Suppl: S31–S36, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richard AJ, Fuller S, Fedorcenco V, Beyl R, Burris TP, Mynatt R, Ribnicky DM, Stephens JM. Artemisia scoparia enhances adipocyte development and endocrine function in vitro and enhances insulin action in vivo. PLoS One 9: e98897, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43: e47, 2015. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rood JC, Schwarz J-M, Gettys T, Mynatt RL, Mendoza T, Johnson WD, Cefalu WT. Effects of Artemisia species on de novo lipogenesis in vivo. Nutrition 30, Suppl: S17–S20, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rydén M, Arvidsson E, Blomqvist L, Perbeck L, Dicker A, Arner P. Targets for TNF-α-induced lipolysis in human adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 318: 168–175, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep 20: 12, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma VM, Puri V. Mechanism of TNF-α-induced lipolysis in human adipocytes uncovered. Obesity (Silver Spring) 24: 990, 2016. doi: 10.1002/oby.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen W-J, Patel S, Natu V, Kraemer FB. Mutational analysis of structural features of rat hormone-sensitive lipase. Biochemistry 37: 8973–8979, 1998. doi: 10.1021/bi980545u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Souza SC, Palmer HJ, Kang Y-H, Yamamoto MT, Muliro KV, Paulson KE, Greenberg AS. TNF-α induction of lipolysis is mediated through activation of the extracellular signal related kinase pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Cell Biochem 89: 1077–1086, 2003. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Souza SC, Yamamoto MT, Franciosa MD, Lien P, Greenberg AS. BRL 49653 blocks the lipolytic actions of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: a potential new insulin-sensitizing mechanism for thiazolidinediones. Diabetes 47: 691–695, 1998. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stephens JM, Lee J, Pilch PF. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is accompanied by a loss of insulin receptor substrate-1 and GLUT4 expression without a loss of insulin receptor-mediated signal transduction. J Biol Chem 272: 971–976, 1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stephens JM, Pekala PH. Transcriptional repression of the C/EBP-alpha and GLUT4 genes in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Regulations is coordinate and independent of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem 267: 13580–13584, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sztalryd C, Brasaemle DL. The perilipin family of lipid droplet proteins: Gatekeepers of intracellular lipolysis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1862: 1221–1232, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sztalryd C, Xu G, Dorward H, Tansey JT, Contreras JA, Kimmel AR, Londos C. Perilipin A is essential for the translocation of hormone-sensitive lipase during lipolytic activation. J Cell Biol 161: 1093–1103, 2003. [Erratum in J Cell Biol 162: 353, 2003]. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vidal-Puig A. Adipose tissue expandability, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome. Endocrinol Nutr 60, Suppl 1: 39–43, 2013. doi: 10.1016/S1575-0922(13)70026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang ZQ, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Tipton RC, Raskin I, Ribnicky D, Johnson W, Cefalu WT. Artemisia scoparia extract attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in diet-induced obesity mice by enhancing hepatic insulin and AMPK signaling independently of FGF21 pathway. Metabolism 62: 1239–1249, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112: 1796–1808, 2003. doi: 10.1172/JCI200319246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoshida H, Takamura N, Shuto T, Ogata K, Tokunaga J, Kawai K, Kai H. The citrus flavonoids hesperetin and naringenin block the lipolytic actions of TNF-α in mouse adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 394: 728–732, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang HH, Halbleib M, Ahmad F, Manganiello VC, Greenberg AS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha stimulates lipolysis in differentiated human adipocytes through activation of extracellular signal-related kinase and elevation of intracellular cAMP. Diabetes 51: 2929–2935, 2002. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Y, Schmidt RJ, Foxworthy P, Emkey R, Oler JK, Large TH, Wang H, Su EW, Mosior MK, Eacho PI, Cao G. Niacin mediates lipolysis in adipose tissue through its G-protein coupled receptor HM74A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 334: 729–732, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zu L, Jiang H, He J, Xu C, Pu S, Liu M, Xu G. Salicylate blocks lipolytic actions of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in primary rat adipocytes. Mol Pharmacol 73: 215–223, 2008. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.039479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]