Summary

Objectives:

Mortality among HIV patients with tuberculosis (TB) remains high in Eastern Europe (EE), but details of TB and HIV management remain scarce.

Methods:

In this prospective study, we describe the TB treatment regimens of patients with multi-drug resistant (MDR) TB and use of antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Results:

A total of 105 HIV-positive patients had MDR-TB (including 33 with extensive drug resistance) and 130 pan-susceptible TB. Adequate initial TB treatment was provided for 8% of patients with MDR-TB compared with 80% of those with pan-susceptible TB. By twelve months, an estimated 57.3% (95%CI 41.5–74.1) of MDR-TB patients had started adequate treatment. While 67% received ART, HIV-RNA suppression was demonstrated in only 23%.

Conclusions:

Our results show that internationally recommended MDR-TB treatment regimens were infrequently used and that ART use and viral suppression was well below the target of 90%, reflecting the challenging patient population and the environment in which health care is provided. Urgent improvement of management of patients with TB/HIV in EE, in particular for those with MDR-TB, is needed and includes widespread access to rapid TB diagnostics, better access to and use of second-line TB drugs, timely ART initiation with viral load monitoring, and integration of TB/HIV care.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, HIV, MDR-TB, Eastern Europe

Introduction

Although rates of tuberculosis (TB) have begun to decline in recent years, simultaneous rapid increases in the relative contribution of multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug resistant TB (XDR-TB) are worrying.1–4 Eastern Europe (EE), together with central Asia, has the worlds’ highest proportions of MDR- and XDR-TB with 9–35% of new TB cases and 49–77% of re-treatment cases being diagnosed with MDR-TB in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine compared with 1–3% of new cases and 4–14% of re-treatment cases in Italy, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.1,5–8

The MDR-TB epidemic in EE is further complicated by high rates of HIV co-infection. Whereas most other regions have reported declining rates of new HIV infections over recent years, EE has experienced an increase of 30% in annual number of new HIV infections since the turn of the millennium.9,10 The TB/HIV epidemic in EE is primarily driven by injection drug users (IDU) who often access health care late, are co-infected with hepatitis C (HCV), and frequently have poor treatment compliance and retention in care.11–14 We recently reported a one-year mortality rate of 27% for TB/HIV co-infected patients in EE, and patients diagnosed with MDR-TB had roughly three-times higher mortality compared to those with drug-susceptible TB. Further, patients from EE who initiated TB treatment with three or more active drugs had significantly lower risk of death compared to patients who received less than three active TB drugs (13% vs 34%).15

Treatment for MDR-TB is complex in terms of pill burden, drug-interactions and toxicity, and costly.1,16–18 MDR-TB therapy is prolonged (typically at least 20 months) although the 2016 WHO guidelines include an option for shorter MDR-TB regimens in specific cases.16,19 Preliminary results with a novel six months regimen (consisting of pretomanid, bedaquiline and linezolid) may be highly effective to treat MDR-TB.20 For now, standard of care consists of at least five drugs including a fluoroquinolone, a second-line injectable, at least two other active drugs plus pyrazinamide during the intensive phase of treatment.19 Reported MDR-TB treatment success rates, however, have been generally low, in particular for HIV-positive individuals, and rarely exceed 50%.18,21

Epidemiological data and detailed descriptions of the clinical management of HIV-positive patients with MDR-TB in EE remain relatively scarce.22 We prospectively studied patients with TB/HIV co-infection in EE and in this paper report on the management of those with MDR-TB.

Methods

Study design and participants

The TB:HIV Study is a prospective cohort study including 62 TB and HIV clinics in 19 countries in EE, Western Europe, Southern Europe, and Latin America. Adult (>16 years) HIV-positive patients with a TB diagnosis were consecutively enrolled between 01/01/2011 and 31/12/2013. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected on standardized case report forms at baseline and month 6, 12, and 2412; further details are available at http://www.cphiv.dk/TBHIV. All participating clinics obtained ethical approval in accordance with local rules and legislations, and the study was performed in accordance with the strobe guidelines for observational studies.23

Study definitions

Patients from EE were included in the present analyses if they had definite or probable TB. A diagnosis of definite TB was based on positive culture or molecular diagnostics for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), and probable TB on the presence of acid fast bacilli and/or granulomatous inflammation on sputum smear or tissue biopsy specimens.12 Baseline was defined as the date TB treatment was initiated, and a baseline culture was defined as a culture obtained within one month of baseline. All TB drugs initiated within 10 days of baseline were considered to constitute initial TB treatment. Standard definitions of MDR-TB, pre-XDR-TB, and XDR-TB were used (see Box 1), and pan-susceptible TB was defined as TB without documented drug resistance. TB treatment regimens were categorized in line with general recommendations16,24: 1: Treatment regimens containing RHZ (with or without ES) targeting drug-susceptible TB,24 2: Treatment regimens containing RHZ plus a fluoroquinolone AND a second line injectable, providing empiric cover for both susceptible TB and MDR-TB, 3: Five or more MDR-TB drugs (including a fluoroquinolone AND a second line injectable) providing appropriate empiric cover for MDR-TB, 4: Regimens containing a fluoroquinolone OR a second line injectable (but not both), providing inadequate cover for MDR-TB, and 5: Any other drug combination (Fig. 1). For patients with MDR-TB, the number of active drugs in the TB regimen was calculated at various time points based on the susceptibility pattern of isolates obtained up to the given time point. If a Drug Susceptibility Test (DST) result was not available for a specific drug included in the regimen, the given Mtb isolate was either considered potentially susceptible to this drug (potentially active drugs) or resistant to this drug (known active drugs), thus representing a “best case” and “worst case” treatment scenario.

Box 1. Definitions of tuberculosis resistance.

| Definition | |

|---|---|

|

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) |

Tuberculosis resistant to rifampicin and isoniazid |

|

Pre-extensively drug- resistant tuberculosis (pre-XDR-TB) |

MDR-TB plus additional resistance against a fluoroquinolone or a second-line injectable |

|

Extensively drug- resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) |

MDR-TB plus additional resistance against a fluoroquinolone and a second-line injectable |

Figure 1.

TB treatment and outcomes over time among 105 patients with MDR-TB (left), 183 with no DST (middle) and 130 patients with susceptible TB (right) from time of start of TB treatment.

R = Rifampicin

H = Isoniazid

Z = Pyrazinamide

E = Ethambutol

S = Streptomycin

FQ = Fluoroquinolone

2L-inj = Second-line injectables

LTFU = Loss to follow-up

DST = Drug-susceptibility test

Antiretroviral treatment (ART) was defined as a combination of ≥ 3 antiretroviral drugs from any ART class. Participants were considered lost to follow-up (LTFU) when no attendance was recorded at the relevant time points in those who were not known to have died.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for baseline characteristics of patients. Patients were stratified into three groups: MDR-TB at baseline, pan-susceptible TB at baseline, and other (no baseline DST results available or the presence of non-MDR-TB resistance patterns). MDR-TB patients who had extended DST available were further classified as having pre-XDR or XDR-TB. Baseline characteristics among patients who had MDR-TB, those who were fully susceptible and those who did not have any baseline DST available were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate for categorical variables, whereas the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables.

TB and HIV treatment regimens were analyzed at months 0, 3, 7, 13, and 21. Kaplan–Meier estimates were used to estimate time to receiving adequate treatment for MDR-TB (category 3: five or more MDR-TB drugs including a fluoroquinolone AND a second line injectable), and time to starting ART censoring at last visit date (maximum 21 months) or death, whichever occurred first. Further, Kaplan–Meier estimates were also used to estimate the time to starting ART. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Statistical Analysis Software, Cary, NC, USA, version 9.3).

Results

Patient characteristics

Of 1406 patients enrolled into the TB:HIV study, 834 received care in EE, of these 485 had definite or probable TB and were included in this analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1). A positive culture for Mtb was reported in 383 (79%) patients, 302 (79%) of these were tested for resistance to any drug, 270 (70%) for both R and H, and 68 (18%) for fluoroquinolone or second line injectables. Of the 485 patients, 105 (22%) had MDR-TB, 130 (27%) had pan-susceptible TB at baseline and 183 (38%) had no DST results; the remaining 67 (14%) had non-MDR-TB resistance patterns and were excluded from subsequent analyses. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were male and white, with a median age of 35 years. Recent incarceration was common, and previous TB, IDU, and HCV co-infection were significantly more common among MDR-TB patients. The median baseline CD4 cell count was 91 (interquartile range [IQR] 31–230) cells/mm3, and only 82 (17%) patients were on ART.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included individuals (N = 485)

| Total |

MDR-TB |

All other groups |

pg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Total | 485 | 105 | 380 | 0.43 | |

| Gender | Male | 374 (77) | 84 (80) | 290 (76) | 0.42 |

| Ethnicitya | White | 442 (94) | 98 (96) | 344 (94) | <0.01 |

| Previous TBb | Yes | 64 (13) | 24 (23) | 40 (11) | 0.52 |

| TB risk factors | Prison | 91 (19) | 22 (21) | 69 (18) | 0.57 |

| Alcohol | 128 (26) | 30 (29) | 98 (26) | 0.22 | |

| Family | 41 (8) | 12 (11) | 29 (8) | N/A | |

| Travel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | |

| Injection frig use(ever) | Yes | 327 (67) | 80 (76) | 247 (65) | 0.32 |

| OST (ever) | Yes | 6 (1) | 0 (0) | 6 (2) | 0.03 |

| Hepatitis Cc | Yes | 254 (52) | 59 (56) | 195 (51) | 0.27 |

| TB type | Pulmonary | 176 (36) | 45 (43) | 131 (34) | |

| Extra pulmonary | 24 (5) | 4 (4) | 20 (5) | ||

| Disseminated | 285 (59) | 56 (53) | 229 (60) | ||

| HIV+ > 3 months before TB diagnosis | Yes | 354 (73) | 81 (77) | 273 (72) | 0.28 |

| ART7 | Yes | 82 (17) | 14 (13) | 68 (18) | 0.27 |

| Median (IQR) | |||||

| Age | Year | 35 (31–40) | 35 (31–40) | 35 (31–40) | 0.75 |

| Weightd | Kg | 60 (53–68) | 63 (55–68) | 59 (53–68) | 0.29 |

| CD4 cell counte | (cells/mm3) | 91 (31–230) | 100 (32–267) | 89 (31–220) | 0.59 |

| HIV-RNAf | Log10 copies/ml | 5.25 (4.40–5.75) | 5.42 (4.46–5.91) | 5.22 (4.35–5.70) | 0.13 |

OST: opioid substitution therapy; ART: antiretroviral therapy.

9 individuals had missing data on previous TB.

17 individuals had missing data on ethnicity.

148 individuals had missing data on hepatitis C.

300 individuals had missing weight at baseline.

87 individuals had missing baseline CD4.

211 individuals had missing baseline HIV-RNA.

P-values compare the characteristics between individuals with MDR-TB and all other individuals in included in the study. The chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test, or Mann-Whitney u test was used as appropriate.

DST patterns for MDR-TB patients

Among the 105 patients with MDR-TB at baseline, DST results (obtained at any time during TB treatment) for other drugs ranged from 51–95% for group 1 drugs, 75–78% for group 2/3 drugs, and 49–69% for group 4 drugs (Table 2). The timing of DST testing for individual TB drugs is shown in Table 3a. Overall, 13 (12%) of MDR-TB patients had XDR-TB, 20 (19%) had pre-XDR, 35 (33%) had MDR, and 37 patients had insufficient data to determine pre-XDR/XDR-TB status.

Table 2.

Results from drug susceptibility test performed at any time point in follow-up among all patients with MDR-TB (N = 105)

| Drug | N (%) with data |

N (% of those tested) with resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | ||

| Pyrazinamide | 54 (51) | 30 (56) |

| Ethambutol | 100 (95) | 72 (72) |

| Streptomycin | 75 (71) | 72 (96) |

| Group 2 | ||

| Fluoroquinolones | 79 (75) | 22 (28) |

| Group 3 | ||

| Second-line injectables | 82 (78) | 35 (43) |

| Group 4 | ||

| Ethionamide/Prothionamide | 72 (69) | 23 (32) |

| Cycloserine/Terizidone | 51 (49) | 8 (16) |

| Para-Aminosalicylic Acid (PAS) | 61 (58) | 10 (16) |

Table 3.

DST performance and TB drug use among patients with MDR-TB (N = 105)

| 3a: N (%) of patients who had DST performed per drug up to the indicated time point among those under follow-up at given time point |

||||||||||||||

| N | R | H | Z | E | FQ | 2L-inj | PT/ET | CS/TZ | PAS | BDQ | DLM | LNZ | ||

| 0 | 105 | 49 (47) | 49 (47) | 27 (26) | 46 (44) | 35 (33) | 37 (35) | 32 (30) | 16 (15) | 24 (23) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 month | 88 | 88 (100) | 88 (100) | 47 (53) | 82 (93) | 63 (72) | 66 (75) | 57 (65) | 40 (45) | 47 (53) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 months | 79 | 79 (100) | 79 (100) | 44 (56) | 74 (94) | 58 (73) | 64 (81) | 54 (68) | 40 (51) | 45 (57) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 months | 72 | 72 (100) | 72 (100) | 40 (56) | 68 (94) | 54 (75) | 61 (85) | 51 (71) | 37 (51) | 41 (57) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 months | 56 | 56 (100) | 56 (100) | 42 (57) | 53 (95) | 43 (77) | 47 (84) | 40 (71) | 30 (54) | 33 (59) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 months | 44 | 44 (100) | 44 (100) | 25 (57) | 42 (95) | 35 (80) | 37 (84) | 30 (70) | 22 (50) | 26 (59) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 21 months | 31 | 31 (100) | 31 (100) | 16 (52) | 29 (94) | 23 (74) | 25 (81) | 23 (74) | 16 (52) | 22 (71) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3b: N (%) of patients under follow-up who received selected anti-TB medications at the indicated time point |

||||||||||||||

| N | R | H | Z | E | FQ | 2L-inj | PT/ET | CS/TZ | PAS | BDQ | DLM | LNZ | ||

| 0 | 105 | 86 (82) | 89 (85) | 90 (86) | 84 (80) | 16 (15) | 23 (22) | 14 (13) | 10 (10) | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 month | 88 | 57 (65) | 59 (67) | 76 (86) | 68 (77) | 32 (36) | 38 (43) | 31 (35) | 23 (26) | 17 (19) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 months | 79 | 39 (49) | 37 (47) | 66 (84) | 53 (67) | 43 (54) | 46 (58) | 40 (51) | 30 (38) | 29 (34) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 months | 72 | 23 (32) | 23 (32) | 55 (76) | 37 (51) | 51 (71) | 48 (67) | 49 (68) | 39 (54) | 33 (46) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 months | 56 | 6 (11) | 5 (9) | 42 (75) | 21 (38) | 50 (89) | 39 (70) | 47 (84) | 37 (66) | 31 (55) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| 13 months | 44 | 5 (11) | 4 (9) | 34 (77) | 14 (32) | 39 (89) | 15 (34) | 33 (75) | 27 (61) | 20 (45) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 21 months | 31 | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 20 (65) | 7 (23) | 25 (81) | 8 (26) | 19 (61) | 22 (71) | 15 (48) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3c: N (%) of patients under follow-up who had ever received selected TB medications at the indicated time point |

||||||||||||||

| N | R | H | Z | E | FQ | 2L-inj | PT/ET | CS/TZ | PAS | BDQ | DLM | LNZ | ||

| 0 | 105 | 86 (82) | 89 (85) | 90 (86) | 84 (80) | 16 (15) | 23 (22) | 14 (13) | 10 (10) | 4 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 month | 88 | 76 (86) | 75 (85) | 81 (92) | 76 (86) | 33 (38) | 40 (45) | 32 (36) | 23 (26) | 17 (19) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 months | 79 | 68 (86) | 66 (84) | 72 (91) | 68 (86) | 45 (60) | 49 (62) | 41 (52) | 31 (39) | 29 (37) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 months | 72 | 62 (86) | 61 (85) | 66 (92) | 61 (85) | 54 (75) | 55 (76) | 51 (71) | 40 (56) | 36 (50) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 months | 56 | 47 (84) | 47 (84) | 53 (95) | 51 (91) | 51 (91) | 49 (88) | 48 (86) | 40 (71) | 33 (59) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| 13 months | 44 | 39 (89) | 39 (89) | 42 (95) | 42 (95) | 40 (91) | 38 (86) | 37 (84) | 31 (70) | 24 (55) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 21 months | 31 | 27 (87) | 27 (87) | 29 (94) | 30 (97) | 29 (94) | 28 (90) | 26 (84) | 23 (74) | 20 (65) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

DST: Drug Susceptibility Test; R: Rifampicin; H: Isoniazid; Z: Pyrazinamide; E: Ethambutol; FQ: Fluoroquinolone; 2L-inj: Second-line injectables; PT/ET: Prothionamide/Ethionamide; CS/TZ: Cycloserine/Terizidone; PAS: Para-aminosalicylic acid; BDQ: Bedaquiline; DLM: Delamanide; LNZ: Linezolid.

Treatment regimen and outcomes

In Fig. 1, TB treatment regimens and outcomes are depicted from baseline through 21 months of follow-up. WHO recommended regimens were initiated in the majority of individuals with drug-susceptible TB but maintained well beyond the recommended 6 months. Despite the high population prevalence of MDR-TB, very few subjects received empiric therapy that provided cover against drug-susceptible and (multi)drug resistant TB (category 2). High rates of death were observed among MDR-TB patients and those without DST. Loss to follow-up (from both TB and HIV care) was high, ranging from 8% of MDR-TB patients to 19–20% among patients with pan-susceptible TB or no DST.

TB treatment for MDR-TB patients

Only 8 (8%) of MDR-TB patients initiated an adequate empiric MDR-TB regimen (category 3), which increased to 35 (44% of patients still under follow-up) after three months. A total of 49 MDR-TB patients ever received category 3 treatment after a median of 1.2 months (IQR 0.4–2.3), and by 12 months, an estimated 57.3% (95%CI = 41.5–74.1%) had started adequate MDR-TB treatment. Similar results were obtained when excluding patients with known pre-XDR-TB or XDR-TB (data not shown).

Fluoroquinolones and second-line injectables were uncommon components of initial treatment and, if used, commonly used without adequate companion drugs (Table 3b/c). By three months, a quarter of MDR-TB patients still had not initiated a fluoroquinolone or a second-line injectable. Group 4 drugs were variably used, a single patient had received linezolid (introduced late during the course of treatment), and no patients had received bedaquiline or delamanide. Culture conversion was documented in 45/105 (43%) of MDR-TB patients and 77/130 (59%) of patients with pan-susceptible TB after a median of 3.0 (IQR 1.8–5.1) and 2.3 (IQR 1.7–4.9, p = 0.30) months, respectively.

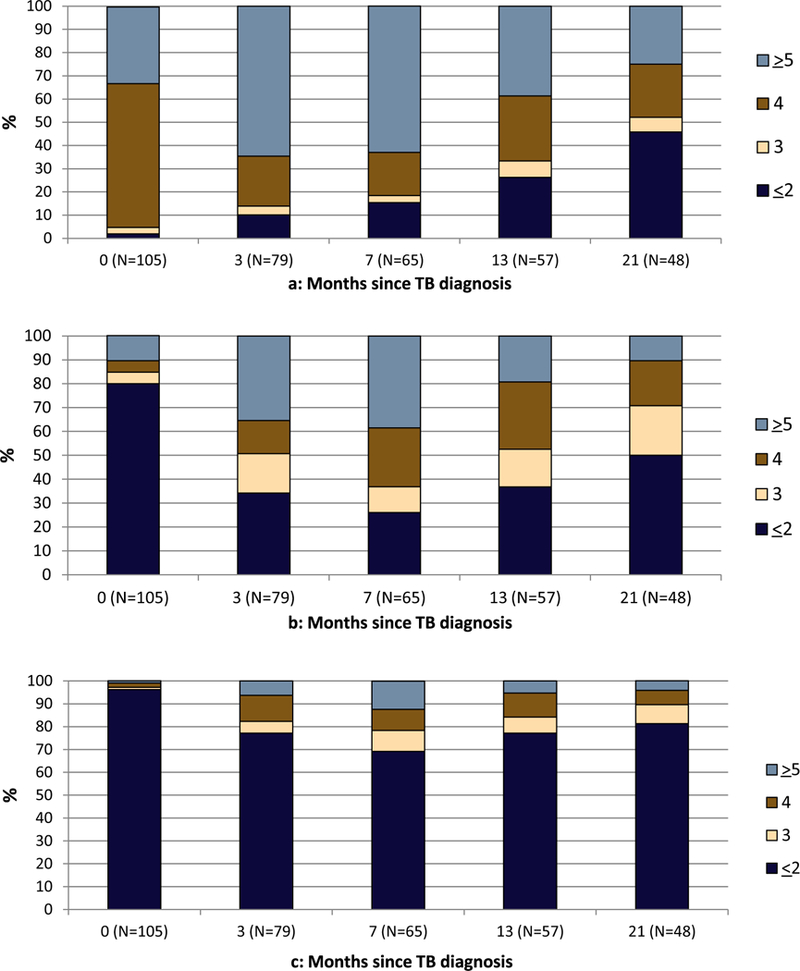

Activity of TB treatment for MDR-TB patients

Fig. 2a–c illustrates the total number of drugs and the total number of “potentially” active drugs and “known” active drugs, respectively, in the MDR-TB treatment regimens. While most patients received 4 or more drugs in their regimen during the first year of treatment, more than 70% received 0, 1 or 2 drugs with demonstrated activity. A regimen containing 5 or more known active drugs was received by less than 15% of patients and a regimen containing 5 or more potentially active drugs by less than 40% of patients.

Figure 2.

a-c: Number of total TB drugs (a), potentially active* (b), and known active** (c) TB drugs at each time point for 105 MDR-TB patients under follow-up.

*Potentially active: Assuming susceptibility where DST for a specific drug was missing.

**Known active: Only including known DST results and not assuming susceptibility for missing DST.

HIV treatment for MDR-TB patients

Despite 77% of MDR-TB patients at the time of their TB diagnosis already having an HIV diagnosis and the majority being severely immunosuppressed with a median CD4 cell count of 100 cells/mm3, only 13% were on ART at baseline (Table 1). The proportion on ART among those who remained in care increased to more than 60% (Fig. 3). The majority of those on ART did not have regular HIV-RNA monitoring, and less than 20% of MDR-TB patients were documented to have had an undetectable HIV-RNA (<500 copies/mL) at any stage during follow up. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of starting ART by eight weeks was only 23%; similar results were observed for patients with drug-susceptible TB and those with no DST results (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Antiretroviral (ART) status over time for MDR-TB patients (N = 105)*

*ART and viral load (VL) was calculated +/− 1 month of the various time-points.

Discussion

This study shows suboptimal management of MDR-TB in HIV-positive patients in EE. Despite the high prevalence of MDR-TB, full DST testing was often restricted and delayed, resulting in prolonged use of inappropriate or failing regimens that contained few active drugs and suboptimal intensification strategies, with only half of patients ultimately receiving recommended MDR-TB therapy. In addition, we observed a low uptake of ART, inadequate viral load monitoring and low rates of HIV-RNA suppression. All of these factors are likely to have contributed to the mortality rate of nearly 50% at two years. These data point towards opportunities to improve management of HIV-positive individuals with TB in parts of EE.

The similar characteristics of patients with and without MDR-TB preclude public health strategies based on risk-stratification of patients and argue for routine DST in all TB patients. Rapid TB diagnostics and DST such as line-probe assays or cartridge-based molecular tests for Mtb and rifampicin resistance16 should be introduced as a priority,25 with routine evaluation of genotypic or phenotypic DST for fluoroquinolones and second line injectables of all rifampicin-resistant isolates. Thirty-nine percent of those tested for MDR-TB in our cohort had MDR-TB which is consistent with other recent reports from the EE region.8,26 Of the patients with MDR-TB, approximately one-third had MDR, one-third had pre-XDR or XDR-TB, and one-third did not have sufficient DST data to assess whether they had (pre-)XDR-TB. We also found common co-resistance to other drugs, as described in another European multicenter study.27 Despite the setting of high MDR-TB prevalence in EE, empiric therapy rarely provided cover for MDR-TB. This is also problematic as selection for additional drug-resistance is more likely to occur early on when the bacillary burden is high. It is worth noting, however, that four in five patients who later were shown to have fully susceptible TB, initially received adequate RHZ-based treat-ment, as recently described.28

In patients with MDR-TB, there were significant delays to initiate treatment for MDR-TB, and many patients never received adequate MDR-TB treatment as defined by international guidelines.19 The number of active drugs remained low at all time points; only one-third of patients were treated at some stage with at least five potentially active drugs, and only one-sixth of patients received regimens with 5 drugs known to have activity against their Mtb isolate. This is of concern as recent studies demonstrate improved outcomes with optimal MDR-TB regimens (≥5 likely effective drugs).29–31 Optimal MDR-TB treatment requires continued, unrestricted access to high quality medications; in a recent survey we documented that this was not the case in many clinics in EE.32 In agreement with this, linezolid, bedaquiline and delamanid were generally not used although widespread use in the current context raises significant opportunities for these drugs to be rapidly lost due to the emergence of resistance.

There is now solid evidence that ART should be initiated shortly after TB diagnosis, especially in patients with MDR-TB and those with CD4 cell counts below 50 cells/mm3.33–36 In our study, patients were severely immunosuppressed, and two-thirds of those who remained under follow-up at three months had initiated ART. However, less than 20% had documented suppressed viral loads at any time which is well short of the WHO goal of virological suppression in 90% of patients receiving ART.37

We documented a mortality rate of nearly 50% within the first two years following initiation of TB treatment, which is similar to the mortality observed in a retrospective study from our group of HIV-patients with MDR-TB in EE which was conducted in the period 2004–2006.14 Retrospective African studies reported mortality rates among HIV-positive patients with MDR-TB of 15–31%38–40 and a meta-analysis of outcomes found a pooled mortality rate of 38%.41 The vast majority of deaths in our retrospective cohort were due to TB,42 which underscores the particular need for high-quality TB management for people with HIV. Other circumstances may have played a role in determining outcome of MDR-TB patients in EE. A disintegrated health care system with separated TB and HIV management remains common32 and is likely to contribute to poor coordination of care to this often very vulnerable patient population. In particular, opioid substitution therapy for IDU is severely restricted or even prohibited in some countries despite documented positive effects on adherence to treatment and health care in general.43

Our observational study has several limitations including the intrinsic risk of selection bias. The participating clinics were primarily located in major cities and may not be representative of all clinics across EE. DST was done locally and methods for performing DSTs varied between clinics, and when calculating the number of active drugs, we counted all drugs as equally effective which is likely to be an over-simplification. A large number of patients had missing DST results, CD4 cell counts and HIV-RNA measurements precluding a more robust evaluation of immune-virological outcomes. Nonetheless, the circumstances described reflect the difficulties for many HIV and TB clinicians working in EE, although substantial regional variability in the prevalence of MDR-TB and availability of DST, TB and ART drugs, and HIV-RNA measurements exists.12 Due to limited number of patients with MDR-TB we did not assess intraregional variability.

Conclusion

In EE, there is an urgent need for access to rapid diagnostics to guide initial TB treatment, to extend DST to all patients diagnosed with rifamycin-resistant or MDR-TB and to provide better access to second line drugs to allow the administration of optimally active MDR-TB regimens. Integration of TB and HIV services can ensure better management and support for people with HIV who frequently have IDU and HCV coinfection, including rapid initiation of fully suppressive ART.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The TB:HIV study group

Eastern Europe

Belarus: Belarusian State Medical University, Department of Infectious Disease: I. Karpov (PI), A. Vassilenko; Republican Research and Practical Centre for Pulmonology and TB (Minsk): A. Skrahina (PI), D. Klimuk, A. Skrahin, O. Kondratenko and A. Zalutskaya; Gomel State Medical University (Gomel): V. Bondarenko (PI), V. Mitsura, E. Kozorez, O. Tumash; Gomel Region Centre for Hygiene: O. Suetnov (PI) and D. Paduto.

Estonia: East Viru Central Hospital (Kohtla-Jarve): V. Iljina (PI) and T. Kummik.

Georgia: Infectious Diseases, AIDS and Clinical Immunology Research Center (Tiblisi): N. Bolokadze (PI), K. Mshvidobadze and N. Lanchava; National Center for Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases of Georgia (Tibilisi): L. Goginashvili, L. Mikiashvili and N. Bablishvili.

Latvia: Infectology Centre of Latvia (Riga): B. Rozentale (PI), I. Zeltina and I. Janushkevich.

Lithuania: Centre for Communicable Diseases and AIDS (Vilnius): I. Caplinskiene (PI), S. Caplinskas, Z. Kancauskiene.

Poland: Wojewodski Szpital Zakanzy/Medical University of Warsaw (Warszawa): R. Podlasin (PI), A. Wiercinska-Drapalo (PI), M. Thompson and J. Kozlowska; Wojewodski Szpital Specjalistyczny/Medical University Teaching Hospital (Bialystok): A. Grezesczuk (PI); Jozef Strus Multidisciplinary City Hospital (Poznan): M. Bura (PI); Wroclaw University School of Medicine (Wroclaw): B. Knysz (PI) and M. Inglot; Jagiellonian University Medical College (Krakow): A. Garlicki (PI) and J. Loster.

Romania: Dr. Victor Babes Hospital (Bucharest): S. Tetradov (PI) and D. Duiculescu (†).

Russia: Botkin Hospital of Infectious Diseases (St. Petersburg): A. Rakhmanova (PI†), O. Panteleeva, A. Yakovlev, A. Kozlov, A. Tyukalova and Y. Vlasova; City TB Hospital No. 2 (St. Petersburg): A. Panteleev (PI); Center for Prevention and Control of AIDS (Veliky, Novgorod): T. Trofimov (PI); Medical University Povoljskiy Federal Region.

Ukraine: Crimean Republican AIDS Centre (Simferopol): G. Kyselyova (PI).

Western Europe

Denmark: Rigshospitalet (Cph): AB. Andersen (PI); Hvidovre University Hospital: K. Thorsteinsson.

Belgium: CHU Saint-Pierre (Brussels): MC Payen (PI), K. Kabeya and C. Necsoi.

France: Aquitaine Cohort. Cohort administration: F. Dabis (PI) and M. Bruyand. Participating Centers and Physicians: Bordeaux University Hospital: P. Morlat; Arcachon Hospital: A. Dupont; Dax Hospital: Y. Gerard; Bayonne Hospital: F. Bonnal; Libourne Hospital: J. Ceccaldi; Mont-de-Marsan Hospital: S. De Witte; Pau Hospital: E. Monlun; Périgueux Hospital: P. Lataste; Villeneuve-sur-Lot Hospital: I. Chossat.

Switzerland, Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS, www.shcs.ch): Cohorte administration: M. Sagette and M. Rickenbach. Participating Centers and Physicians: University Hospital Basel: L. Elzi and M. Battegay; University Hospital Bern: H. Furrer (PI); Hopital Cantonal Universitaire, Geneve: D. Sculier and A. Calmy; Centre Hospitalaire Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne: M. Cavassini; Hospital of Lugano: A. Bruno and E. Bernasconi; Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen: M. Hoffmann and P. Vernazza; University Hospital Zurich: J. Fehr and Prof. R. Weber. This study has been co-financed within the framework of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study, supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant # 148522) and by SHCS project 666. The data are gathered by the Five Swiss University Hospitals, two Cantonal Hospitals, 15 affiliated hospitals and 36 private physicians).The members of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study are: Aubert V, Battegay M, Bernasconi E, Böni J, Bucher HC, Burton-Jeangros C, Calmy A, Cavassini M, Dollenmaier G, Egger M, Elzi L, Fehr J, Fellay J, Furrer H (Chairman of the Clinical and Laboratory Committee), Fux CA, Gorgievski M, Günthard H (President of the SHCS), Haerry D (deputy of “Positive Council”), Hasse B, Hirsch HH, Hoffmann M, Hösli I, Kahlert C, Kaiser L, Keiser O, Klimkait T, Kouyos R, Kovari H, Ledergerber B, Martinetti G, Martinez de Tejada B, Metzner K, Müller N, Nadal D, Nicca D, Pantaleo G, Rauch A (Chairman of the Scientific Board), Regenass S, Rickenbach M (Head of Data Center), Rudin C (Chairman of the Mother & Child Substudy), Schöni-Affolter F, Schmid P, Schüpbach J, Speck R, Tarr P, Telenti A, Trkola A, Vernazza P, Weber R, Yerly S.

United Kingdom: Mortimer Market Centre (London): R. Miller (PI) and N. Vora; St. Mary’s Hospital: G. Cooke (PI) and S. Mullaney; North Manchester General Hospital: E. Wilkins (PI) and V. George; Sheffield Teaching Hospitals: P. Collini (PI) and D. Dockrell; King’s College Hospital (London): F. Post (PI), L. Campbell, R. Brum, E. Mabonga and P. Saigal. Queen Elizabeth Hospital: S. Kegg (PI); North Middlesex University Hospital: J. Ainsworth (PI) and A. Waters. Leicester Royal Infirmary: J. Dhar (PI) and L. Mashonganyika.

Southern Europe:

Italy: IRCCS – Ospedale L. Spallanzani (Rome): E. Girardi (PI), A Rianda, V. Galati, C. Pinnetti and C. Tommasi; AO San Gerardo (Monza): G. Lapadula (PI); IRCCS AOU San Martino – IST di Genoa (Genova): A. Di Biagio (PI) and A. Parisini; Clinic of Infectious Diseases, University of Bari (Bari): S. Carbonara (PI), G. Angarano and M. Purgatorio; University of Brescia Spedali Civili: A. Matteelli (PI) and A. Apostoli.

Spain: Barcelona Cohort funded by the Spanish HIV/AIDS Research Network. Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Madrid (Spain) provided JMM a personal intensification research grant #INT15/00168 during 2016.: Hospital Clinic of Barcelona: J.M. Miro (PI), C. Manzardo, C. Ligero and J. Gonzalez; Hospital del Mar: F. Sanchez, H. Knobel, M. Salvadó and J.L. Lopez-Colomes; Mutua de Terrassa: X. Martínez-Lacasa and E. Cuchí; Hospital Universitari Vall d’Herón: V. Falcó, A. Curran, M.T. Tortola, I. Ocaña and R. Vidal; Hospital Universitari de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau: MA. Sambeat, V. Pomar anbd P. Coll; Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge: D. Pozamczer, M. Saumoy and F. Alcaide; Agencia de Salud Pública de Barcelona: J. Caylà, A. Moreno, J.P. Millet, A. Orcau, L. Fina, L. del Baño, L.L. Roldan. Hospital Universitario Donostia (San Sebastian): JA. Iribarren (PI) and M. Ibarguren; Hospital Universitario Ramon y Cajal (Madrid): S. Moreno (PI) and A. González; Hospital Universitario ‘Gregorio Maranon’ (Madrid): P. Miralles (PI) and T. Aldámiz-Echevarría.

Latin America

The CICAL Cohort: Cohorte administration: M. Losso (PI), J. Toibaro and L. Gambardella. Participating Centers and Physicians: Argentina: Hospital J. M. Ramos Mejía (Buenos Aires): J. Toibaro and L. Moreno Macias; Hospital Paroissien (BA): E. Warley (PI) and S. Tavella; Hospital Piñero (BA): O. Garcia Messina and O. Gear; Hospital Nacional Profesor Alejandro Posadas: H. Laplume; Hospital Rawson (Cordoba): C. Marson (PI); Hospital San Juan de Dios (La Plata): J. Contarelia and M. Michaan; Hospital General de Agudos Donación F. Santojani: P. Scapellato and D. D Alessandro; Hospital Francisco Javier Muñiz (BA): B. Bartoletti and D. Palmero; Hospital Jujuy: C. Elias. Chile: Fundación Arriaran (Santiago): C. Cortes. México: INNcMZS (México DF): B. Crabtree (PI); Hospital General Regional de Leon- CAPACITS: JL Mosqueda Gomez; Hospital Civil de Guadalajara: A. Villanueva and LA Gonzalez Hernandez.

TB:HIV steering committee

H. Furrer, E. Girardi, J. A. Caylá, M. H. Losso, J. D. Lundgren, A. Panteleev (co-chair), R. Miller, J.M. Miro, Å. B. Andersen, S. Tetradov, F. A. Post (co-chair), A. Skrahin and J. Toibaro.

Statistical centre

A. Schultze, A. Mocroft.

Coordinating centre

AM. W. Efsen, M. Mansfeld, B. Aagaard, B. R. Nielsen, A H. Fisher, E.V. Hansen, D. Raben, D. N. Podlekareva, O. Kirk.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported by EU – 7th Framework (FP7/2007–2013, EuroCoord n 260694) programme. The funding source had no role in study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

RFM reports personal fees from Gilead, ViiV, Merck, and Jannsen outside the submitted work (non-promotional lectures on clinical aspects of HIV infection). JMM reports grants and personal fees from Abbvie, BMS, Cubist, Genentech, Gilead, Medtronik, MSD, Novartis, and ViiV Healthcare outside the submitted work. EG reports personal fees from Otsuka Novel products, Angelini, Gilead, Jannsen outside the reported work. HJF reports grants from Abbvie, Gilead, MSD, BMS, ViiV, all paid to his institution outside the submitted work. OK reports personal fees and non-financial support from Gilead, personal fees from ViiV, non-financial support from Bristol Myers-Squibb outside the submitted work. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Conference presentation

The results from this study were presented as a poster at the TB2016 conference, 16–17 July, Durban, South Africa (www.tb2016.org). Poster “Management of TB/HIV Co-infected Patients Including MDR-TB in Eastern Europe: Results from the TB:HIV Study”, number: P37.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2015. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_eng.pdf. [Accessed 1 October 2017].

- 2.Zumla A, Chakaya J, Centis R, D’Ambrosio L, Mwaba P, Bates M, et al. Tuberculosis treatment and management–an update on treatment regimens, trials, new drugs, and adjunct therapies. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3(3):220–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daley CL, Caminero JA. Management of multidrug resistant tuber-culosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2013;34(1):44–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casali N, Nikolayevskyy V, Balabanova Y, Harris SR, Ignatyeva O, Kontsevaya I, et al. Evolution and transmission of drug-resistant tuberculosis in a Russian population. Nat Genet 2014;46(3):279– 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acosta CD, Dadu A, Ramsay A, Dara M. Drug-resistant tubercu-losis in Eastern Europe: challenges and ways forward. Public Health Action 2014;4(Suppl 2):S3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balabanova Y, Ignatyeva O, Fiebig L, Riekstina V, Danilovits M, Jaama K, et al. Survival of patients with multidrug-resistant TB in Eastern Europe: what makes a difference? Thorax 2016;71: 854–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skrahina A, Hurevich H, Zalutskaya A, Sahalchyk E, Astrauko A, Hoffner S, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Belarus: the size of the problem and associated risk factors. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91(1):36–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skrahina A, Hurevich H, Zalutskaya A, Sahalchyk E, Astrauko A, van Gemert W, et al. Alarming levels of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Belarus: results of a survey in Minsk. Eur Respir J 2012;39(6): 1425–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS. AIDS by the numbers. WORLD AIDS DAY 2015. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/AIDS_by_the_numbers_2015_en.pdf. [Accessed 1 October 2017].

- 10.Yablonskii PK, Vizel AA, Galkin VB, Shulgina MV. Tuberculosis in Russia. Its history and its status today. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191(4):372–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeHovitz J, Uuskula A, El-Bassel N. The HIV epidemic in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2014;11(2):168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efsen AM, Schultze A, Post FA, Panteleev A, Furrer H, Miller RF, et al. Major challenges in clinical management of TB/HIV coinfected patients in Eastern Europe compared with Western Europe and Latin America. PLoS ONE 2015;10(12):e0145380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Late presenters working group in CiE, Mocroft A, Lundgren J, Antinori A, Monforte A, Brannstrom J, et al. Late presentation for HIV care across Europe: update from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe (COHERE) study, 2010 to 2013. Euro Surveill 2015;20(47). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Post FA, Grint D, Werlinrud AM, Panteleev A, Riekstina V, Malashenkov EA, et al. Multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis in HIV positive patients in Eastern Europe. J Infect 2014;68(3):259–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Podlekareva DN, Efsen AM, Schultze A, Post FA, Skrahina AM, Panteleev A, et al. Tuberculosis-related mortality in people living with HIV in Europe and Latin America: an international cohort study. Lancet HIV 2016;3(3):e120–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis 2011. update. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44597/1/9789241501583_eng.pdf. [Accessed 1 October 2017]. [PubMed]

- 17.Gunther G, Gomez GB, Lange C, Rupert S, van Leth F, TBNET. Availability, price and affordability of anti-tuberculosis drugs in Europe: a TBNET survey. Eur Respir J 2015;45(4):1081–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange C, Abubakar I, Alffenaar JW, Bothamley G, Caminero JA, Carvalho AC, et al. Management of patients with multidrug-resistant/extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J 2014;44(1):23–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. WHO treatment guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis 2016. update. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250125/1/9789241549639-eng.pdf. [Accessed 1 October 2017].

- 20.Conradie F, Diacon A, Everitt D, Mendel C, Niekerk C, Howell P, et al. The NIX-TB Trial Of Pretomanid, Bedaquiline And Linezolid To TreaT XDR-TB. Abstract number 80LB. Oral presentation from Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI). 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahuja SD, Ashkin D, Avendano M, Banerjee R, Bauer M, Bayona JN, et al. Multidrug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis treatment regimens and patient outcomes: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 9,153 patients. PLoS Med 2012;9(8):e1001300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abubakar I, Zignol M, Falzon D, Raviglione M, Ditiu L, Masham S, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: time for visionary political leadership. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13(6):529–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strobe Group. Strobe statement 2009. Available from: http://strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=strobe-home.strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=strobe-home. [Accessed 1 October 2017].

- 24.World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis guidelines fourth edition 2010. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44165/1/9789241547833_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1. [Accessed 1 October 2017]. [PubMed]

- 25.Xie YL, Chakravorty S, Armstrong DT, Hall SL, Via LE, Song T, et al. Evaluation of a rapid molecular drug-susceptibility test for tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2017;377(11):1043–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zignol M, Dean AS, Alikhanova N, Andres S, Cabibbe AM, Cirillo DM, et al. Population-based resistance of Mycobacterium tuber-culosis isolates to pyrazinamide and fluoroquinolones: results from a multicountry surveillance project. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16(10):1185–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunther G, van Leth F, Altet N, Dedicoat M, Duarte R, Gualano G, et al. Beyond multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Europe: a TBNET study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015;19(12):1524–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podlekareva DNSA, Panteleev A, Skrahina AM, Miro JM, Rakhmanova A, Furrer H, et al. and the TB:HIV study in EuroCoord#. One-year mortality of HIV-positive patients treated for rifampicin-and isoniazid- susceptible tuberculosis in Eastern Europe, Western Europe and Latin America. Accepted for publication in AIDS 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Ahmad Khan F, Gelmanova IY, Franke MF, Atwood S, Zemlyanaya NA, Unakova IA, et al. Aggressive regimens reduce risk of recur-rence after successful treatment of MDR-TB. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:214–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franke MF, Appleton SC, Mitnick CD, Furin JJ, Bayona J, Chalco K, et al. Aggressive regimens for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis reduce recurrence. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56(6): 770–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velasquez GE, Becerra MC, Gelmanova IY, Pasechnikov AD, Yedilbayev A, Shin SS, et al. Improving outcomes for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: aggressive regimens prevent treatment failure and death. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59(1):9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansfeld M, Skrahina A, Shepherd L, Schultze A, Panteleev AM, Miller RF, et al. Major differences in organization and availabil-ity of health care and medicines for HIV/TB coinfected patients across Europe. HIV Med 2015;16(9):544–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, Padayatchi N, Baxter C, Gray A, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med 2010;362(8):697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanc FX, Sok T, Laureillard D, Borand L, Rekacewicz C, Nerrienet E, et al. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365(16): 1471–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Group ISS, Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, Emery S, Grund B, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373(9):795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Havlir DV, Kendall MA, Ive P, Kumwenda J, Swindells S, Qasba SS, et al. Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365(16):1482–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.UNAIDS. 90–90-90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic 2014. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2017/90-90-90. [Accessed 1 October 2017].

- 38.Satti H, McLaughlin MM, Hedt-Gauthier B, Atwood SS, Omotayo DB, Ntlamelle L, et al. Outcomes of multidrug-resistant tuber-culosis treatment with early initiation of antiretroviral therapy for HIV co-infected patients in Lesotho. PLoS ONE 2012;7(10): e46943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin SS, Modongo C, Boyd R, Caiphus C, Kuate L, Kgwaadira B, et al. High treatment success rates among HIV-infected multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients after expansion of antiretroviral therapy in Botswana, 2006–2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74:65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Umanah T, Ncayiyana J, Padanilam X, Nyasulu PS. Treatment outcomes in multidrug resistant tuberculosis-human immuno-deficiency virus co-infected patients on anti-retroviral therapy at Sizwe Tropical Disease Hospital Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isaakidis P, Casas EC, Das M, Tseretopoulou X, Ntzani EE, Ford N. Treatment outcomes for HIV and MDR-TB co-infected adults and children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015;19(8):969–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Podlekareva DN, Panteleev AM, Grint D, Post FA, Miro JM, Bruyand M, et al. Short- and long-term mortality and causes of death in HIV/tuberculosis patients in Europe. Eur Respir J 2014;43(1): 166–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morozova O, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Methadone treatment improves tuberculosis treatment among hospitalized opioid dependent patients in Ukraine. Int J Drug Policy 2013;24(6):e91–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.