Abstract

Negative energy balance is a prevalent feature of cystic fibrosis (CF). Pancreatic insufficiency, elevated energy expenditure, lung disease, and malnutrition, all characteristic of CF, contribute to the negative energy balance causing low body-growth phenotype. As low body weight and body mass index strongly correlate with poor lung health and survival of patients with CF, improving energy balance is an important clinical goal (e.g., high-fat diet). CF mouse models also exhibit negative energy balance (growth retardation and high energy expenditure), independent from exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, lung disease, and malnutrition. To improve energy balance through increased caloric intake and reduced energy expenditure, we disrupted leptin signaling by crossing the db/db leptin receptor allele with mice carrying the R117H Cftr mutation. Compared with db/db mice, absence of leptin signaling in CF mice (CF db/db) resulted in delayed and moderate hyperphagia with lower de novo lipogenesis and lipid deposition, producing only moderately obese CF mice. Greater body length was found in db/db mice but not in CF db/db, suggesting CF-dependent effect on bone growth. The db/db genotype resulted in lower energy expenditure regardless of Cftr genotype leading to obesity. Despite the db/db genotype, the CF genotype exhibited high respiratory quotient indicating elevated carbohydrate oxidation, thus limiting carbohydrates for lipogenesis. In summary, db/db-linked hyperphagia, elevated lipogenesis, and morbid obesity were partially suppressed by reduced CFTR activity. CF mice still accrued large amounts of adipose tissue in contrast to mice fed a high-fat diet, thus highlighting the importance of dietary carbohydrates and not simply fat for energy balance in CF.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We show that cystic fibrosis (CF) mice are able to accrue fat under conditions of carbohydrate overfeeding, increased lipogenesis, and decreased energy expenditure, although length was unaffected. High-fat diet feeding failed to improve growth in CF mice. Morbid db/db-like obesity was reduced in CF double-mutant mice by reduced CFTR activity.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, db/db mouse model, energy expenditure, hyperphagia, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lethal inherited disease, characterized by chronic pulmonary infection, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, reduced growth, and low body mass index (BMI). The morphometric indices in patients with CF strongly correlate with health and survival, with weight at a young age being a strong predictor of pulmonary function at later ages (11a). Therefore, maintaining a healthy body weight and body composition is an important clinical goal. This growth deficit is addressed clinically through pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy coupled with aggressive nutritional support [high-fat (30–45% kcals), high-energy diet (110–200%) of recommended daily allowance]. Similar to patients with CF, CF mice exhibit retarded growth and remain short and lean for their age (52), albeit independently from characteristic exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and malnutrition (4). We previously reported significantly reduced insulin-like growth factor-1 in Cftr-null mice along with marginally reduced serum growth hormone (37). Our further investigations in CF mice revealed low food intake at weaning and consequent low hepatic and adipose tissue de novo lipogenesis (DNL), as well as low fatty acid deposition to adipose tissue stores, contributing to low growth and adiposity (4). Furthermore, we recently reported high energy expenditure in CF mice (12) consistent with findings of elevated energy expenditure and substrate oxidation in infants (14, 22), children (39), and adults with CF (6, 9, 10, 51). In some studies, elevated energy expenditure correlated with pancreatic insufficiency (33, 46), poor nutritional status (32, 50), or poor lung health (6, 45). In contrast, elevated energy expenditure was found in patients with CF even with good nutritional status and lung function, suggesting its intrinsic nature (38). Together, these findings suggest a model of energy imbalance in CF characterized by low growth and high energy expenditure.

In an attempt to shift energy balance and improve growth, we fed CF mice a high-fat, high-calorie diet. Unexpectedly, high-fat diet feeding resulted in emaciated phenotype with low fat stores and high mortality because of intestinal obstruction, a characteristic of CF mouse models. We therefore investigated other strategies to provide CF mice with additional calories for growth and energy demands and report here the effects of manipulating leptin signaling.

It has been suggested that leptin, an adipose-generated hormone and a major controller of energy balance, may be involved in the energy imbalance characteristic of CF (2). In individuals without CF, leptin levels correlate with fat mass and would be expected to be low in patients with CF. However, Ahmed et al. (1) reported poor correlation of elevated leptin levels with fat mass in children and adolescents with CF, consistent with elevated energy expenditure and low energy storage characteristic of CF. However, others have reported either decreased or no difference in leptin levels in both children and adults (8, 11) citing inflammatory cytokines and heterogeneity of controls as causes for these discrepancies (43). Despite inconclusive results with regard to leptin levels, studies reported significantly lower fat and lean body mass in patients with CF suggesting leptin-independent mechanisms.

The db/db mouse model is a research tool used to augment food intake and lipogenesis, increase body weight and length, and lower energy expenditure, all of which are arguably the opposite of CF mouse characteristics. Impairing leptin receptor signaling in the db/db mouse model results in hyperphagia, hyperinsulinemia, and consequently, high DNL leading to rapid adipose tissue gain (15, 30, 48). Coupled with lower energy expenditure and substrate oxidation (53), these alterations in energy balance all contribute to an obese phenotype. Although this can also be accomplished by eliminating leptin production, as in the ob/ob mouse model, the leptin gene (Lep) is tightly linked to Cftr on chromosome 6, and thus the ability to make double mutants will be difficult as recombination is rare between the two genes. The leptin receptor gene, LepR, in contrast is on the different chromosome and thus independently assorts with Cftr, allowing double mutants to be generated readily through a dihybrid cross.

Given the attributes of the db/db mouse model, we hypothesized that the removal of leptin signaling in our CF mouse model would “correct” low growth and adiposity via hyperphagia-stimulating DNL and lipid accretion and lowering of energy expenditure. Together, these efforts would shift energy balance from negative to positive, potentially uncovering mechanisms of reduced growth in CF. Our experimental strategy was to cross the db/db allele of the leptin receptor into CF mouse lines. We found that the CF mutation masked the effects of db/db-linked obesity, resulting in an intermediate phenotype. Double mutants did exhibit increased growth, hyperphagia, DNL, and lower energy expenditure leading to increased body weight and adipose tissue but surprisingly not in body length. Despite markedly lower energy expenditure, the intermediate phenotype of the double mutants was presented as delayed growth, lower grade of hyperphagia, lower lipogenesis, and elevated carbohydrate oxidation.

Overall, we found that a high-fat diet failed to improve growth in CF mice; however, db-linked carbohydrate overfeeding was compensatory to the high energy expenditure characteristic of CF and provided animals with excess carbon for DNL and lipid accretion. Our results highlight the importance of dietary carbohydrates for adipose tissue accretion in CF.

METHODS

Husbandry and Genotyping

Mice with CF were homozygous for the R117H mutation in Cftr (Cftrtm2Uth). We initially crossed the db/db allele to CF mice carrying the Cftrtm1Kth mutation, which was used to gather preliminary data on energy imbalance, but the double mutants had very poor survival because of high incidence of intestinal obstruction. To reduce the risk of obstruction and improve survival, we crossed db/db onto a line of mice carrying Cftrtm2Uth (R117H) mutation associated with milder disease in humans and significantly lower incidence of intestinal obstruction in mice but that does not positively affect growth (25). Mice were bred to congenicity by the continuous backcrossing to C57BL/6J for at least 15 generations. Littermates homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele (designated “WT”) were used as controls. C57BL/6J mice carrying the leptin receptor mutant allele db/db (strain B6.BKS(D)-Leprdb/db/J; Jackson Laboratories) were crossbred with CF mice to create double-mutant animals (designated “CF db/db”). Mice were housed at constant temperature (22°C) on a 12-h:12-h light-dark cycle. The experimental groups consisted of both sexes [male (M)/female (F) ratio] represented as follows: WT n = 26 (M/F: 14/12), db/db n = 9 (M/F: 4/5), CF n = 25 (M/F: 7/18), CF db/db n = 9 (M/F: 5/4). Mice were fed regular chow (see below) ad libitum. Food intake was measured twice a week for up to 100 days and expressed as the average per animal in grams and kcals and per gram body weight. Feed efficiency was calculated using the following formula: feed efficiency (%) = weight gained (g/day)/food consumed (g/day) × 100% (31). Animal growth was followed for ~100 days after weaning. Naso-anal length was determined postmortem for consistent measurements. Animals were stretched and fixed with surgical pins and length was measured using calibrated calipers (Fisher Scientific). BMI was calculated by dividing the body weight (kg) by length (cm) squared. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University.

All mice in this study were fed a standard rodent diet (9% fat, kcals) from lard (Cat. No. 7960, Teklad) ad libitum, except for the high-fat experiments in which mice were fed a high-fat diet (58% fat, kcals) from lard (Cat. No. D-12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ). For diet experiments, the following groups were used: WT low fat (LF) n = 26 (M/F: 14/12) CF LF n = 25 (M/F: 7/18), WT high fat (HF) n = 12 (M/F: 5/7), HF CF n = 15 (M/F: 6/9).

Chemicals and Supplies

Unless specified, all chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Body Composition (MRI Imaging)

Mice were acclimated to the Case Center for Imaging Research facility for several days. On the day of imaging, animals were weighed and anesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane in oxygen. The animals were then placed in a prone position within a Bruker Biospec 7T MRI scanner (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA). A 72-mm-diameter volume coil was used for excitation and signal detection to maximize the uniformity of the images. After localizer scans, a relaxation compensated fat fraction MRI acquisition and reconstruction process was used to generate quantitative fat fraction maps for each imaging slice (27). Briefly, three asymmetric echo spin echo MRI acquisitions were acquired (repetition time/echo time = 1,500 ms/0 ms, 17–25 coronal slices, resolution = 200 × 200 × 1,000 µm, 2 averages). The three acquisitions were acquired with different echo shifts to allow separate fat and water images to be generated. Finally, a semiautomatic image analysis was performed to segment and calculate the respective volumes of peritoneal and subcutaneous adipose tissues.

Indirect Calorimetry

Oxygen consumption (V̇o2), carbon dioxide production (V̇co2), and respiratory exchange ratio were determined using the 8-chamber Oxymax indirect calorimetry system (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). On the morning of the experiment, the instrument was calibrated against a standard gas mix containing defined quantities of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen. On the day of the experiment, mice (2 from each group, n = 8 per run, total of 4 runs) were weighed and placed individually into the enclosed plastic indirect calorimetry chambers furnished with the water bottle and ad libitum food supply. After brief acclimatization, collection of experimental data began and proceeded for ~24 h under 12-h:12-h light-dark cycle at room temperature. After ~24 h, animals were returned to their respective cages. Total energy expenditure was computed using a modified Weir equation: total energy expenditure = (3.815 + 1.232 × respiratory exchange ratio) × V̇o2 (19).

Fecal Sample Collection

Fecal samples were collected by allowing mice to defecate naturally, and the feces were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Before processing, fecal samples were lyophilized to remove moisture and weighed. Total triglycerides (TGs) were extracted using the Folch procedure (17).

De Novo Lipogenesis (Stable Isotope Protocol)

We determined the rates of lipogenesis following the incorporation of deuterium (2H) from deuterated water (2H2O) into newly made TG-bound fatty acids, as reported previously (5). At 3:00 pm, CF and non-CF mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of 2H-labeled saline (28 ml per kg body wt of 9 g NaCl in 1,000 ml 99.9% 2H2O). After injection, mice were returned to their cages and maintained on 6% 2H-labeled drinking water overnight. This procedure maintains a steady-state labeling of body water at ~3.0–3.5% 2H molar percent enrichment. After ~19 h of exposure to deuterated water, mice were weighed, anesthetized with carbon dioxide, and exsanguinated. Blood samples were collected and livers and white adipose tissue (WAT) were freeze-clamped using Wollenberger tongs, weighed, and frozen. All samples and tissues were kept at −86°C until processing.

Histology

Livers were sampled fresh and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Atlanta, GA) for 24 h at 4°C. Samples were cryo-protected in 15% sucrose followed by 30% sucrose overnight. Blocks were made using optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Tissue Tek, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Liver samples were sectioned using a cryostat (Cat. No. CM-1850, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Tissue sections (6 μm) were warmed and placed in Oil Red O (0.5% solution, Poly Scientific R&D) for 1.5 h at room temperature. Samples were next rinsed with distilled water and stained with filtered Harris Hematoxylin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for a few seconds. Liver samples were rinsed and coverslipped with VectaShield mounting media (Vector, Burlingame, CA). The ×40 magnification images were captured using a Rolera XR CCD camera (Q-Imaging, Surrey, Canada) mounted on a Leica DMLB microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Analytical Procedures

Isotopic deuterium enrichments of the body water and TG-bound fatty acids and concentration profiles of tissue fatty acids were determined using an Agilent 5973N-MSD (mass selective detector) equipped with an Agilent 6890 gas chromatography system [gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS)]. A DB17-MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) was used in all assays with a helium flow of 1 ml/min. Samples were analyzed in Selected Ion Monitoring mode using electron impact ionization. Ion dwell time was set to 10 ms.

2H-labeling of body water.

The 2H-labeling of body water was determined by exchange with acetone, as previously described by Katanik et al. (28). Briefly, 20 µl of whole blood or standard were reacted overnight at room temperature with 4 µl of 10 N KOH and 4 µl of 5% acetone in acetonitrile. Deuterated acetone was then extracted by the addition of 500 µl of chloroform, dried with sodium sulfate, and 100 µl was transferred to a GC/MS vial insert, and 1 µl sample was injected in GC/MS in split mode (1:40). Acetone mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) 58 and 59 were monitored. Isotopic enrichment was determined as ratio of m/z 59/(58 + 59) and corrected using a standard curve.

2H-labeling of TG-bound fatty acids.

The 2H-labeling of TG-bound palmitate was determined from liver and WAT extracts. Briefly, weighed liver/WAT samples were extracted using the Folch extraction method as described elsewhere (17). Isolated TGs were saponified by reacting with 1 ml of 1 N KOH (70% Ethanol, vol/vol) at 90°C for 2 h. After acidification, palmitate was extracted three times with hexane. Combined hexane extracts were evaporated to dryness, and palmitate was converted to trimethylsilyl derivative by the following derivatization procedure: 80 µl of bis(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide + 10% trimethylchlorosilane (Regis, Morton Grove, IL) were added to the dried samples and reacted for 30 min at 75°C. Derivatized sample was transferred to GC/MS vial insert, and 1 µl was injected in GC/MS in split mode (1:40). The following ions (313–317) were monitored for palmitate. Isotopic enrichment was determined for each corrected mass isotopomer as Mi/Σ (M0 . . . Mi). Total isotopic enrichment was determined as sum of all isotopic enrichments such as M1 + (M2 × 2) + (Mn × n). Total enrichment was divided by factor 22, number of deuterium atoms/carbon incorporated for palmitate, resulting in fractional enrichment (41). Finally, fractional lipogenesis was determined using a precursor-product relationship of “fractional enrichment/2H-body water × time (days).”

Tissue concentration profiles of TG-bound fatty acids.

We determined concentration profiles of myristic (14:0), palmitic (16:0), stearic (18:0), oleic (18:1), linoleic [18:2 (n−6)], and linolenic [18:3 (n−3)] fatty acids extracted from liver and adipose tissue. Tissues were extracted as described above. Concentrations of fatty acids were determined by comparing the abundance of m/z 285, 313, 341, 339, 337, and 335, respectively, to that of heptadecanoic acid (17:0), m/z 327, added as internal standard. Because ionization efficiency of various fatty acids is different, we premixed equal quantities of each fatty acid to determine the correction factors (1.0 for myristate, 0.95 for palmitate, 0.9 for stearate, 0.5 for oleate, 0.4 for linoleate, and 0.3 for linolenate). Each sample was run in duplicate.

Statistical Analyses

In all experiments, mice were randomized using a systematic approach. On average, the number of mice per group was 6–8 per genotype per sex. All statistical analysis were conducted by an epidemiologist in a blinded fashion (data codes were not available to the analyst). As deemed appropriate, univariate and multivariate statistical analyses were conducted independently using parametric statistics (Student’s t-tests and/or one-way analysis of variance or their nonparametric alternatives) (35). Simple and multivariable stepwise linear and logistic or multinomial logistic regression analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (STATA Corp., College Station, TX), depending on the outcome of interest following assumptions and definitions as previously described (16, 26). Associations between outcomes measured on the same animal over time (e.g., body weight repeated measures), animal sex, and results from laboratory tests were investigated by using a multilevel mixed-effects linear regression while controlling for unbalanced designs, missing data points, and adjusting for both fixed and random effects. Mouse was set as a random effect to estimate and test the genotype variance component (40).

Predicted linear slopes for time series curves were calculated using average marginal effect statistics (slopes were presented in figures as summary statistics to illustrate overall curve steepness, and their significant departure from 0 as P values). Variables associated with the ability of a test result to predict the mouse genotype (WT, CF, db/db, and CF db/db) were also investigated in separate analyses using multinomial logistic regression. During initial model building, variables with P < 0.15 were selected to construct final models. Parameters were considered statistically significant if P values were <0.05. Pairwise comparisons of least square means were performed for the genotype categories by using dummy variable and expanded interaction methods within the regression analysis tools available in the STATA software, which allows the estimation of F and adjusted Z statistics and P values.

Multivariate principal component analysis, vector visualization, and multivariate T-squared distribution statistics (40) were used for the comprehensive analysis of fatty acid data envelopes (Fig. 7). P values between 0.05 and 0.1 were shown when appropriate.

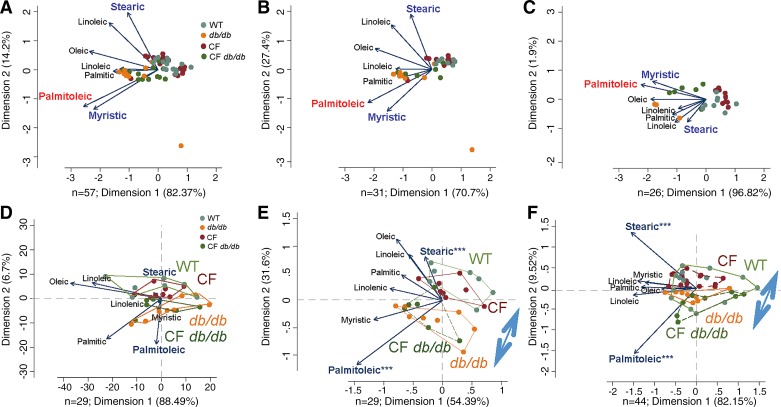

Fig. 7.

Multivariate vector analysis of hepatic and adipose tissue revealed a pattern of TG-bound fatty acids that segregate db/db and CF db/db mice. A and D: 6 + 17 wk old; B and E: 6 wk old, and C and F: 17 wk old. Notice that myristic (liver only), stearic, and palmitoleic acids were consistently different and opposite in both tissues separating the mice with db/db genotypes from those without (highlighted in bold), irrespective of mice age (weeks 6 vs. 17, adjusted P = 0.5). Notice that in adipose tissue the segregation is reproducible and more pronounced (with less influence of myristic acid; see polygons grouping samples based on genotype). Arrows indicate the magnitude effect and direction of separation of significant data sets. The double-head arrows indicate significant multivariate segregation of genotypes based on a model with palmitoleic and stearic acids, (regression adjusted ***P < 0.001). Log transformed data was used for multivariable analysis. CF, cystic fibrosis; TG, triglyceride; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

RESULTS

High-Fat Diet Feeding

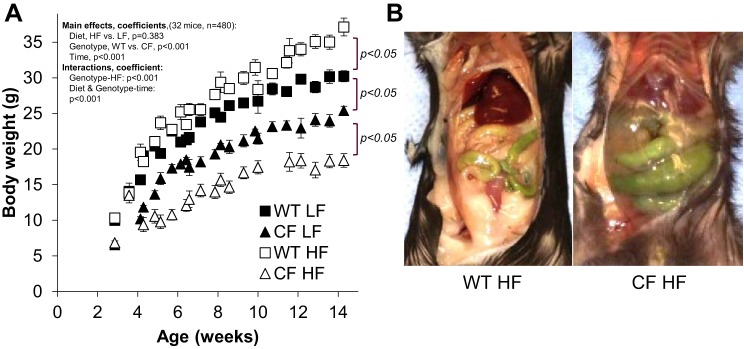

To overcome previously reported low de novo lipid synthesis and triglyceride deposition (4), we fed CF mice a high-fat, high-calorie diet (36, 44). Figure 1A shows growth curves of WT and CF mice fed either high-fat or low-fat diets. Regardless of diet, both mice genotypes gained weight. Data were analyzed using mixed-effects linear regression model, which showed that when diet, genotype, and their interaction with time were modeled collectively, diet was not a significant driving force in the model (adjusted P = 0.383); however, when CF genotype was considered separately, there was a significant effect of high-fat diet (P < 0.001). After 10 wk of feeding, comparison of final body weights revealed wide weight disparity between the groups, with HF groups exhibiting the biggest difference (WT LF: 30.2 ± 0.7, WT HF: 37.1 ± 1.2, CF LF: 25.4 ± 0.6, and CF HF: 18.4 ± 0.9). Our strategy of high-fat diet feeding resulted in obese WT mice and emaciated CF mice as shown in Fig. 1B. MRI quantification of visceral body fat confirmed these differences in adipose tissue depots (visceral fat volume, WT high fat: 2.5 ± 0.3 vs. CF high fat: 0.5 ± 0.1 mm3, P < 0.001). Because our high-fat feeding strategy was unsuccessful to overcome low growth in CF mice, we crossed CF mice with db/db mice to remove leptin signaling and thus induce hyperphagia and stimulate DNL and fat accretion.

Fig. 1.

High-fat diet feeding fails to improve growth in CF mice. A: growth curves (body weight) of mice fed regular chow (LF, 9% fat, kcals) or high-fat diet (HF, 58% fat, kcals). WT LF n = 26 (M/F: 14/12), LF CF n = 25 (M/F: 7/18), WT HF n = 12 (M/F: 5/7), CF HF n = 15 (M/F: 6/9). Data were analyzed using multilevel mixed-effects linear regression model, which revealed that collectively, diet was not a significant driving force in the full model (bodyweight = diet, genotype, and their interactions with time, performed repeated time analysis with mice as groups; adjusted P = 0.383; 734 observations, Wald χ = 2242) but was important interacting with genotype and HF diet, CF compared with WT (major model coefficients and P values shown). CF HF group had on average 5 g less weight gain than WT, controlling for all other variables in the model. Over time, all the linear predictions showed significant changes over time (marginal line slope predictions: WT LF: 0.22, WT HF: 0.25, CF LF: 0.15, CF HF: 0.14, all different from zero, P < 0.001). B: pictures showing lack of adipose tissue deposition in CF mice fed high-fat diet. CF, cystic fibrosis; F, female; HF, high fat; LF, low fat; M, male; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

Caloric Intake and Body Growth

We previously showed that CF mice, after weaning, exhibit low food intake of solid chow, leading to low availability of carbohydrates for DNL and consequently low adipose tissue deposition. Leptin regulates food intake by signaling satiety; therefore, we investigated whether disrupting leptin signaling in CF mice would lead to increased food (caloric) intake and increased body growth. Figure 2A shows food intake profiles from weaning until 10 wk of age. The removal of leptin signaling resulted in a characteristically rapid increase in food intake of db/db mice reaching a plateau by 5 wk. At the end of the experimental period, db/db mice doubled their food intake, which resulted in a rapid gain of weight growth (Fig. 2B, between 3 and 8 wk, WT: 2.5 vs. db/db: 6.7 g/day). From 8 to 15 wk of age, the WT growth rate reached a plateau whereas db/db mice continued to gain weight (WT: 1.2 vs. db/db: 3.4 g/day).

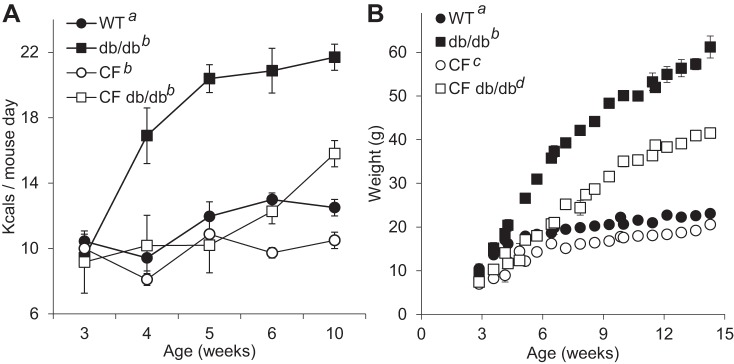

Fig. 2.

Delayed increase in caloric intake and body growth in CF db/db mice. A: food intake over the study period. Data were analyzed using mixed-effects linear regression model, which revealed that only db/db mice had a significantly increased food intake profile (adjusted P < 0.011) compared with the other genotypes (CF P = 0.987 and CF db/db P = 0.135, n = 107 observations over time and 19 mice, model Chibar2 P = 0.01). Marginal linear model predictions were not significant for WT (slope 0.03, P = 0.152) and CF (slope 0.02, P = 0.277) whereas predictions were significantly different for db/db (slope 0.16, P < 0.001) and CF db/db (slope 0.07, P < 0.001). Data are average ± SE. B: body weight over the study period. Mixed-effects linear regression showed that all animals gained weight over time (slopes: WT 0.2, db/db 0.59, CF 0.18, CF db/db 0.48). Compared with WT, CF had lowest body weight, but the effect was marginal (model adjusted P = 0.068 n = 480 observations, 32 mice). But this effect was not significant comparing average marginal effects predicted from the model, as compared with the other two genotypes (db/db and CF db/db) for which the effects were strongly significant P < 0.0001. In this experiment, all marginal predicted slopes for body weight gain were greater than zero (adjusted value of predictions P < 0.0001 for all genotypes). Superscripts with same letter indicate no significant adjusted differences. a,b,c,dhighlight differences. Data are average ± SE. CF, cystic fibrosis; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

Absence of leptin signaling in CF mice also resulted in higher food intake, although 2 wk delayed relative to mice with WT CFTR. The delayed hyperphagic response coincided with the lower growth rate of CF db/db mice at 3–8 wk (Fig. 2B; CF: 2.6 vs. CF db/db: 3.7 g/day). From 8 to 15 wk of age, CF db/db animals maintained the same high growth rate whereas the CF group reached a plateau (CF db/db: 3.8 vs. CF: 0.9 g/day).

Food intake at the end of experimental period increased more than twice for db/db mice as compared with WT (Fig. 2A, WT 10.0 ± 0.5: vs. db/db: 21.7 ± 0.8 kcals/mouse day, P < 0.01) but only increased 1.5 times for CF db/db (Fig. 2A, CF: 9.7 ± 0.4 vs. CF: db/db 15.8 ± 0.8 kcals/mouse day, P < 0.05). Note that food intake was similar for WT and CF mice at 14 wk. When food intake was normalized per g body wt, db/db and CF db/db mice were most efficient as they required less calories per unit of body wt, whereas the CF group was least efficient as they had highest food intake per unit of body wt (WT: 0.383 ± 0.02, db/db: 0.350 ± 0.01, CF: 0.441 ± 0.02, and CF: db/db ± 0.821 kcals/mouse day). Overall, the db/db genotype in Cftr-WT mice resulted in hyperphagia and rapid body weight increase, whereas presence of CF genotype resulted in delayed onset of hyperphagia and thus lower bodily growth.

Body Growth and Morphometric Indices

Table 1 shows body weights in both the beginning (after weaning, 3 wk old) and the end of the experimental period (14 wk) and percent change. As we and others have reported (5, 52), CF mice had lower body weight compared with WT mice at weaning and adult ages. Body weights of db/db mice at weaning did not differ from WT weights, whereas CF (adjusted P < 0.001) and CF db/db (adjusted P < 0.01) mice at weaning were significantly smaller than WT mice. Although CF db/db mice gained significantly more weight than CF mice, it was proportionately less than that gained by the obese db/db mice. Body weight of db/db and CF db/db mice increased about double that of the WT or CF mice, respectively. We also found sex-specific differences in weight gain; WT and CF females had weights similar to males at weaning but had lower weights at 14 wk of age compared with males. This sex-specific difference was not observed in either db/db or CF db/db mice.

Table 1.

Body weights at weaning and adult ages and percent increase

| Age |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 3 wk | 14 wk | Increase from 3 to 14 wk, % | |

| WT | ||||

| Males | 9 | 10.0 ± 0.3 | 30.2 ± 0.8 | 300 |

| Females | 6 | 10.5 ± 1.1 | 23.1 ± 0.8 | 220 |

| db/db | ||||

| Males | 5 | 8.9 ± 1.3 | 58.1 ± 2.7 | 650 |

| Females | 11 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 61.2 ± 2.5 | 650 |

| CF | ||||

| Males | 4 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 25.4 ± 0.6 | 380 |

| Females | 5 | 6.6 ± 0.7 | 20.6 ± 0.8 | 310 |

| CF db/db | ||||

| Males | 5 | 8.0 ± 0.2 | 42.5 ± 1.0 | 530 |

| Females | 4 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 41.5 ± 2.7 | 560 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of mice. 3 wk, weaning; 14 wk, adult. CF, cystic fibrosis; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

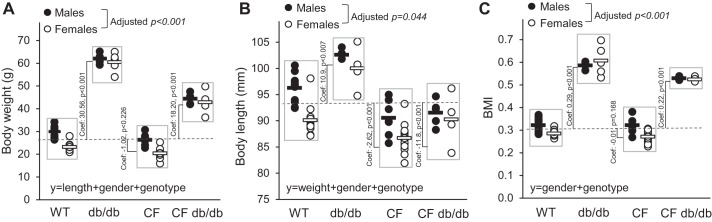

Figure 3, A–C, shows individual (circles) and average values (line symbol) of body weight, length, and BMI, respectively, at 14 wk of age. A linear regression model revealed that independent of sex, body weights of db/db and CF db/db mice were markedly higher (Fig. 3A) as compared with WT and CF, respectively. Note that absolute gain of CF db/db mice was markedly lower than of db/db alone indicating a CF-dependent effect. Female WT (pairwise comparisons, P < 0.001) and CF (pairwise comparisons, P < 0.001) mice had significantly lower body weight than their male counterparts; however, this difference was absent in db/db (pairwise comparisons P = 0.54) and CF db/db (pairwise comparisons P = 0.61) groups.

Fig. 3.

Morphometric growth indices show short obese CF db/db mice. A: body weights. B: body lengths. C: BMI. WT n = 26 (M/F: 14/12), db/db n = 9 (M/F: 4/5), CF n = 25 (M/F: 7/18), CF db/db n = 9 (M/F: 5/4). Males: closed symbols. Females: open symbols. Dashed line represents average WT values; all model coefficients shown are illustrated as visual reference with respect to WT average. Significance was determined using multinomial logistic linear regression analysis which showed that length was the most significant and influential parameter (adjusted P < 0.0001) that also interacted with sex (adjusted P < 0.005) to predictably differentiate genotypes. Predictive multinomial analysis revealed that length and sex were the most important predictors to differentiate genotype, but the effects were noticeable differentiating WT from CF P < 0.05 controlling for all variables (observations 69, PseudoR2 = 7941 χ P < 0.001). BMI, body mass index; CF, cystic fibrosis; coef, coefficient; F, female; M, male; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

Humans and animals afflicted with CF are short for age. Figure 3B shows changes in linear growth. Expectedly, CF mice were significantly shorter than WT mice (P < 0.001). The db/db mice exhibited ~8% greater linear growth than WT mice, (coefficient 10.9, P = 0.007) whereas there was less difference (~4%) between the CF and CF db/db mice (P < 0.05). Female mice were significantly shorter (adjusted P < 0.001) than male mice in all but the CF db/db group. Overall, when leptin signaling was absent, linear growth increased; however, presence of the CF genotype diminished this growth.

Figure 3C shows the effects of leptin signaling’s absence on BMI. Both db/db and CF db/db mice exhibited higher BMI, reflecting an increase in body length and an even larger increase in body weight. Interestingly, female mice had significantly lower BMI than male mice in WT (adjusted P < 0.001) and CF (adjusted P < 0.001) groups but not when leptin signaling was disrupted, indicating sexual dimorphism in leptin-influenced growth. Thus, the absence of leptin signaling resulted in morphometric indices that were influenced by the Cftr genotype.

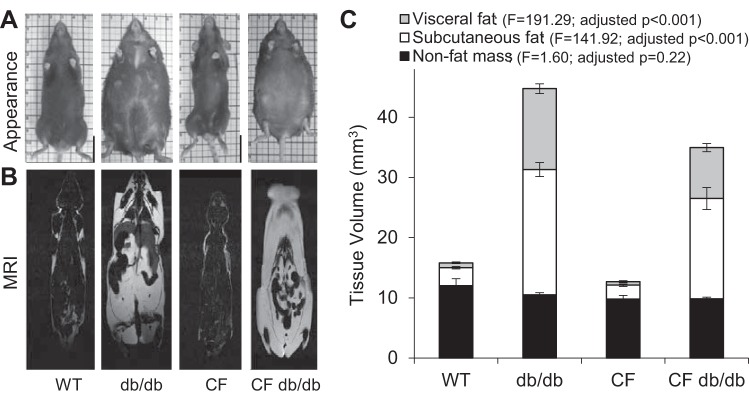

Body Composition

Figure 4A shows obese db/db and CF db/db mice that are much larger than WT and CF mice. Also, consistent with low adiposity, the CF mouse appears emaciated compared with the WT. Pictures were taken on a 1-cm grid to show relative size and length, on which reduced linear growth of CF and CF db/db mice was evident, indicating that the increased body mass did not improve linear growth.

Fig. 4.

Magnetic resonance imaging shows marked adipose tissue expansion in db/db and CF db/db mice. A–C: illustrates body composition analysis. Data are average ± SE. Linear regression analysis [F(3,16) statistics], showed statistically significant differences between the groups. Nonfat mass was marginally different in CF db/db group compared with all other groups (P = 0.05). Visceral fat was different in db/db (P < 0.001) and CF db/db (P < 0.001) groups compared with WT and CF. Subcutaneous fat was different in db/db (P < 0.0001) and CF db/db, (P < 0.0001) groups compared with WT and CF. CF, cystic fibrosis; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

Absence of leptin signaling causes marked expansion of lipid storage. Using MRI, we quantified the volume of adipose tissue stores, both visceral and subcutaneous. Also, changes in nonfat tissue mass representing mostly skeletal muscle were quantified at ~10 wk of age. MRI slices of the fat fraction (white) are shown in Fig. 4B. Using computational algorithms (27), we quantified body composition, shown in Fig. 4C. Nonfat mass was significantly lower and only different in CF db/db group (P < 0.05). Visceral fat was markedly higher only in db/db and CF db/db groups, as compared with WT and CF, respectively. Similarly, subcutaneous fat was also higher only in db/db and CF db/db groups, as compared with WT and CF, respectively. Absence of leptin signaling resulted in both the db/db and CF db/db groups to gain ~7 times more subcutaneous fat than the WT and CF groups, respectively. Visceral fat of both db/db and CF db/db groups increased ~17 and ~14 times, respectively. These results show that inactivation of the leptin receptor in CF mice results in obesity via accretion of adipose tissue and that the relative effects on subcutaneous fat were similar regardless of Cftr status, but visceral fat depots were smaller in CF db/db mice than db/db mice.

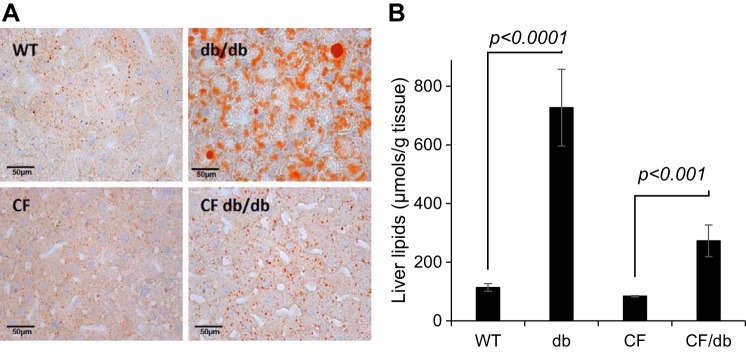

Hepatic Steatosis

Hepatic lipid accumulation or hepatic steatosis is characteristic of db/db mouse models (48). The qualitative assessment of hepatic steatosis is shown in Fig. 4A with representative liver tissue slices. Liver lipids were stained with Oil Red O and hematoxylin-eosin staining and shown under ×40 magnification. The db/db panel clearly shows predominant lipid infiltration into hepatic parenchyma. The CF db/db panel shows less lipid infiltration. We quantified hepatic lipids using MRI and mass spectrometry. Based on MRI, WT and CF mice had similar liver lipids consistent with our previous data in F508del mice (4). The db/db and CF db/db mice accumulated ~6 times and 5 times more lipids, respectively (WT: 0.09 ± 0.01, db/db: 0.57 ± 0.05, and CF db/db: 0.46 ± 0.07 mm3, P < 0.0001) (48). These findings were in agreement with those determined by mass spectrometric analyses, shown in Fig. 5B. Linear regression model showed most steatosis in db/db group, followed by CF db/db group. Overall, removal of leptin receptor signaling resulted in characteristic steatosis in both WT and CF mouse models, apparently driven by elevated hepatic DNL. Indeed, markedly increased DNL has been reported in the db/db mouse model (48).

Fig. 5.

Hepatic steatosis is more pronounced in db-dependent mouse genotypes. A: representative histological appearance (Oil-Red and H&E staining) of liver tissues. B: biochemical quantification of hepatic fat. Linear regression model controlling for all the variables showed most steatosis in db/db followed by CF db/db. Adjusted p values for the model (F(3, 22) = 30.43) are shown. Additional comparisons were as follow, WT vs. CF db/db (P < 0.01), db/db vs. CF db/db (P < 0.0001). WT vs. CF comparison was not significant (P = 0.57). CF, cystic fibrosis; H&E, hematoxylin-eosin; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

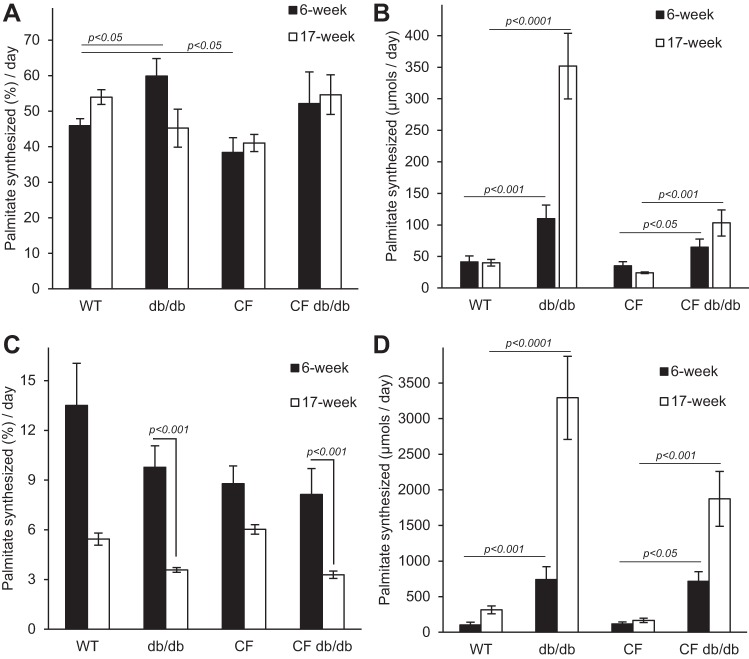

Hepatic DNL

The DNL pathway converts excess carbon from carbohydrates and proteins into fatty acids, i.e., palmitic is the principal fatty acid produced by the fatty acid synthase. DNL occurs mainly in the liver and to some extent in adipose tissue. We previously showed that CF mice exhibit low hepatic DNL, contributing to lack of adipose tissue stores (4). In the current work, DNL was measured in 6- and 17-wk-old mice following deuterium incorporation. The 6-wk-old group was chosen to compare with our previous findings in F508del mice (4), and the older group (17 wk) was analyzed at the end of our experimental period. Figure 6, A and B, shows fractional and absolute DNL rates, respectively, for triglyceride-bound palmitate of 6- and 17-wk-old mice. Fractional lipogenesis rate (FSR) refers to a fraction of the palmitate pool that was synthesized de novo during the experimental period whereas absolute rate (ASR) takes into account FSR and pool size, i.e., total amount of palmitate in the liver samples. Data from 6-wk-old mice agree with our previous findings in that 1) WT mice exhibit high DNL rates reflecting reliance on high-carbohydrate content of the diet for lipid accretion, and 2) similar to F508del mice, R117H mice have significantly lower DNL rates (pairwise comparisons, P < 0.05) at 17 wk.

Fig. 6.

Marked increases in de novo lipogenesis rates of palmitate in db/db and CF db/db mice. A: hepatic fractional lipogenesis, db/db was significant from WT at 6 wk only. B: hepatic absolute lipogenesis. Mixed-effects linear model revealed significant differences in age-dependent db/db mice rates as compared with WT (adjusted P < 0.001) and in CF db/db rates as compared with CF (P < 0.05). C: adipose tissue fractional lipogenesis. D: adipose tissue absolute lipogenesis. Data were analyzed using mixed-effects linear regression model F(6,19.71), which revealed age-dependent significant increases in absolute rates of lipogenesis in db/db and CF db/db genotypes as compared with WT and CF, respectively. Data are average ± SE. CF, cystic fibrosis; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

Figure 6B shows absolute rates of palmitate synthesis. WT mice ASR did not change with age whereas db/db mice nearly tripled (~2.7-fold) ASR by 6 wk (P < 0.001) and ~9-fold by 17 wk of age (P < 0.0001). At 6 wk old, CF db/db ASR also increased ~twofold from CF, (P < 0.05) ~fourfold by 17 wk (P < 0.01). Overall, both db/db and CF db/db mice markedly upregulated DNL of palmitate to support accretion of adipose tissue, albeit CF mutation suppressed full increase in lipogenesis rates.

Adipose Tissue Lipogenesis

Similar to hepatic lipogenesis, adipose tissue contributes to triglyceride formation, albeit to a smaller degree de novo and mostly by reesterification of free fatty acids (triglycerogenesis). Fractional adipose tissue lipogenesis was determined as the fraction of triglyceride-bound fatty acids carrying deuterium. Hepatic and extrahepatic sources both contribute to this pool to an unknown degree. Figure 6C shows fractional lipogenesis, measured from TGs isolated from epididymal adipose tissue. In 6-wk-old mice, fractional lipogenesis in adipose tissue was not different among the groups indicating that deuterium incorporation was proportional to adipose tissue growth. These rates agree well with our previous findings in F508del mice (4). As the adipose tissue expanded with age, “apparent” FSR rates based on deuterated fatty acids of hepatic and extrahepatic origins had decreased significantly in 17-wk-old mice. Both db/db and CF db/db FSR rates decreased to greater extents than WT and CF mice (P < 0.001). Note that CF mice had the least change in fractional rate with age, indicating a lack of adipose tissue accumulation.

Absolute lipogenesis (Fig. 6D) was determined using fractional rates, palmitate concentration, and epididymal tissue wet weights. Similar to our findings in F508del mice (5), R117H (CF) mice had significantly lower fat-pad weights, (WT: 0.45 ± 0.08 vs. CF: 0.23 ± 0.03 g wet wt, P < 0.01). Removal of leptin-receptor signaling resulted in 9- and 13-fold expansions of the epididymal fat pads of WT and CF mice, respectively. This expansion was fueled by 7- and 6-fold increases in ASR in 6-wk-old db/db and CF db/db groups, respectively, and an 11-fold increase at 17 wk of age. These data show that despite having small fat-pad size at weaning, presence of the db/db genotype allows for similar adipose tissue expansion in the CF mice.

Hepatic and Adipose Tissue Remodeling of TG-Bound Fatty Acid Composition

Total hepatic lipids normalized per liver weight were not different in 6-wk-old mice indicating efficient lipid export. However, total hepatic lipids in the 17-wk-old mice were markedly higher in db-carrying groups (WT: 114.0 ± 12.9 vs. db/db 727.1 ± 130.8 vs. CF 84.2 ± 2.7, vs. CF db/db 273.0 ± 54.0 µmols lipid/g tissue, P < 0.01). Such marked increases in hepatic lipids indicate inability of the liver to efficiently export excess lipid leading to hepatic steatosis. These data are in agreement with the increases in ASR from previous section.

To quantify the effects of removal of leptin signaling in CF mice on the remodeling of hepatic fatty acids, we measured concentrations of TG-bound fatty acids, analyses shown in Fig. 7, A–C. Multivariate vector analyses of the data are shown as biplots. Figure 7A shows results combined for both ages, whereas Fig. 7B shows 6-wk-old data and Fig. 7C shows 17-wk-old data. Analyses show that among all fatty acids, myristic, stearic, and to lesser extent palmitoleic were different, separating data into groups with db/db phenotype from those without (WT and CF).

Figure 7, D–F, shows analyses of TG-bound fatty acids isolated from adipose tissue for combined ages (Fig. 7D), 6-wk-old (Fig. 7E), and 17-wk-old (Fig. 7F) mice groups. Double-head arrows in Fig. 7, E and F indicate significant (regression adjusted P < 0.001) separation among db-carrying genotypes from those that do not. More separation was evident in younger animals.

Marked increases in long-chain fatty acids in db/db and CF db/db mice groups suggests increased rates of postsynthesis processing, i.e., elongation and desaturation, shown in the following section.

Desaturation and Elongation Ratios

We recently reported low de novo synthesis of palmitate and consequent low elongation and desaturation rates in F508del mice (4). In this study, we find marked increases in DNL and thus a large production of palmitate, a primary precursor for desaturation and elongation reactions. Table 2 shows markedly increased desaturation and elongation ratios in db/db and CF db/db mice groups driven by the increased lipid flux of newly made palmitate. These data demonstrate dominance of db/db mutation for increasing desaturation and elongation reaction fluxes regardless of CF mutation, which was shown to decrease those fluxes. Table 3 shows changes in desaturation and elongation ratios of fatty acids isolated from epididymal fat pads. Similar to hepatic changes, desaturation of palmitate increased three- and twofold (6 wk) and 1.8- and 1.3-fold (17 wk) in db/db and CF db/db mice, respectively. Desaturation of stearate was only significantly different in CF db/db mice as compared with CF. Elongation of palmitate was significantly increased 1.3-fold for db/db and CF db/db mice of 6 wk of age and 1.1- and 1.8-fold, respectively, for db/db and CF db/db mice of 17 wk.

Table 2.

Hepatic fatty acids desaturation and elongation ratios

| Desaturation Ratio 16:1/16:0 |

Desaturation Ratio 18:1/18:0 |

Elongation Ratio 16:0/18:0 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 wk old | 17 wk old | 6 wk old | 17 wk old | 6 wk old | 17 wk old | |

| WT | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 1.31 ± 0.11 | 1.48 ± 0.16 | 1.53 ± 0.07 | 1.54 ± 0.07 |

| db/db | 0.15 ± 0.02# | 0.22 ± 0.03# | 6.15 ± 0.70* | 7.20 ± 1.80* | 3.70 ± 0.30* | 3.19 ± 0.21* |

| CF | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 1.85 ± 0.52 | 1.37 ± 0.12 | 1.77 ± 0.23 | 1.62 ± 0.04 |

| CF db/db | 0.13 ± 0.02# | 0.21 ± 0.02# | 4.00 ± 0.87* | 4.54 ± 0.85* | 2.62 ± 0.37* | 2.41 ± 0.24* |

Vallues are means ± SE. Data were analyzed using multilevel mixed-effects linear regression model. Model revealed significant age effect only in db/db and CF db/db groups, compared with WT and CF, respectively (adjusted P < 0.001). CF, cystic fibrosis; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

P < 0.01, pairwise comparisons;

P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Adipose tissue fatty acids desaturation and elongation ratios

| Desaturation Ratio 16:1/16:0 |

Desaturation Ratio 18:1/18:0 |

Elongation Ratio 16:0/18:0 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 wk old | 17 wk old | 6 wk old | 17 wk old | 6 wk old | 17 wk old | |

| WT | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 5.94 ± 0.89 | 10.86 ± 1.28 | 4.80 ± 0.38 | 6.81 ± 0.60 |

| db/db | 0.29 ± 0.02# | 0.21 ± 0.02# | 6.26 ± 0.65 | 12.45 ± 2.38* | 6.34 ± 0.40* | 7.47 ± 0.81* |

| CF | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 5.85 ± 0.45 | 8.58 ± 1.02 | 5.10 ± 0.33 | 5.44 ± 0.29 |

| CF db/db | 0.26 ± 0.03# | 0.23 ± 0.03# | 7.09 ± 1.09* | 15.00 ± 2.10* | 6.97 ± 0.70* | 9.70 ± 0.86* |

Values are means ± SE. Data were analyzed using multilevel mixed-effects linear regression model. Model revealed no significant age effects in 16:1/16:0 ratio but there was an effect in 18:1/18:0 ratio in all but CF group (adjusted P < 0.001). No age effect was found in 16:0-to-18:0 ratio. CF, cystic fibrosis; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

P < 0.01, pairwise comparisons;

P < 0.05.

Fecal Lipid Excretion

We previously showed that F508del mice did not exhibit fecal lipid loss (4). Here, we examined fecal lipids from the four groups and found that the absence of leptin receptor signaling resulted in less fatty acid content for both CF and non-CF mice, despite the increased dietary intake. Of note, the CF mice had fewer fatty acids in their stools than WT controls, regardless of leptin receptor status (WT: 134.3 ± 24.0, db/db: 115.4 ± 14.4, CF: 93.7 ± 13.6, and CF db/db: 72.1 ± 4.7 µmols lipid/g dry wt), again implying that reduced accretion of fat in CF is not simply due to substrate availability.

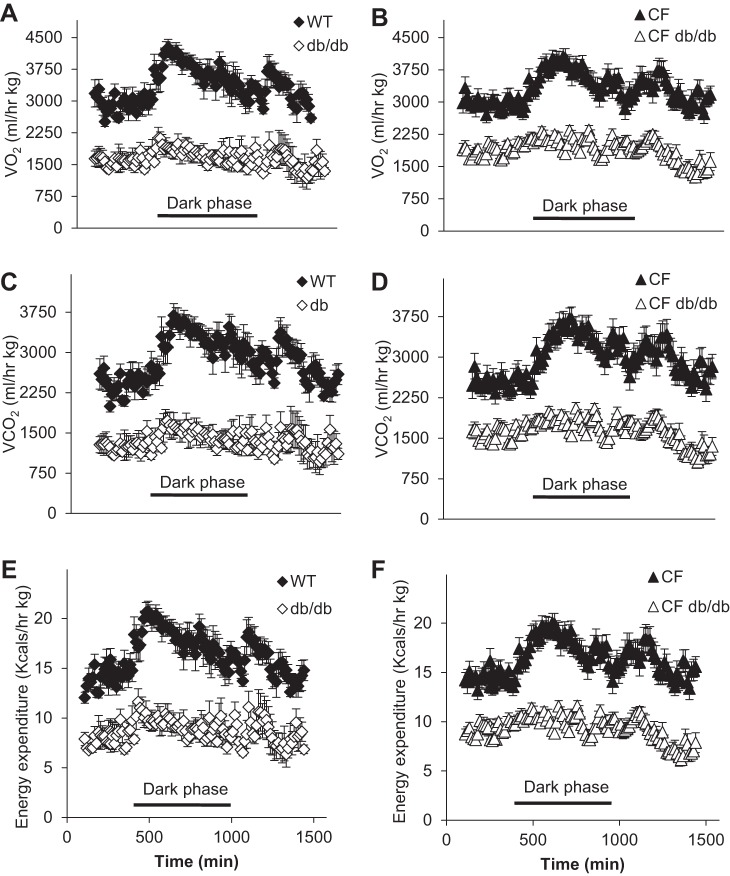

Energy Expenditure

Lastly, we explored reduced energy expenditure, another phenotype caused by the db mutation contributing to increased adipose stores. Daily energy expenditure was measured in 17-wk-old animals using 24-h indirect calorimetry. Figure 8 shows profiles of 24-h oxygen consumption (Fig. 8, A and B, V̇o2, ml·h−1·kg−1), carbon dioxide production (Fig. 8, C and D, V̇co2, ml·h−1·kg−1), and energy expenditure (Fig. 8, E and F, kcals·h−1·kg−1). The data clearly show that the leptin mutation alone or in combination with CF significantly lowered all the measured parameters. Moreover, db/db and CF db/db mice lost the circadian rhythm of activity during the dark phase as the profiles remain flat during the dark phase of the day cycle. WT and CF mice profiles clearly show an increase in all the parameters indicating the end of light phase and beginning of dark phase of the day, marked by higher activity.

Fig. 8.

Comparative (pairwise) 24-h indirect calorimetry profiles show significant differences for db-derived genotypes. A and B: oxygen consumption (V̇o2; ml·h−1·kg−1); C and D: carbon dioxide production (V̇co2; ml/h kg); E and F: energy expenditure (kcals·h−1·kg−1); closed diamonds: WT; open diamonds: db/db; closed triangles: CF; open triangles: CF/db. Data are average ± SE. CF, cystic fibrosis; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele.

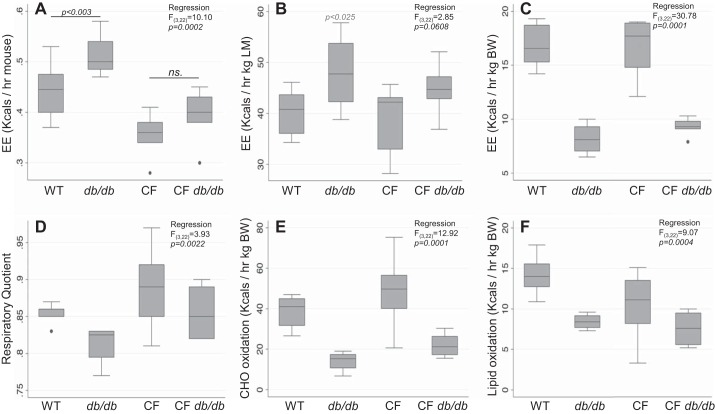

Figure 9 shows average energy expenditure over 24 h and normalized per animal (Fig. 9A), per lean body mass (Fig. 9B) and per unit total body mass (Fig. 9C) to evaluate energy expenditure and its source. Normalization per animal shows that db/db animals require more energy than their Cftr-matched counterparts, but CF db/db animals did not have higher energy demands than WT mice, indicating energy expenditure was not simply related to weight. Most of the weight in db/db and CF db/db mice is adipose tissue, which has low energy consumption. When normalized to lean mass (Fig. 9B), CF and non-CF mice were similar in energy expenditure, and the db/db genotype caused an elevation that was proportional to the fat tissue accrued. Energy expenditure normalized to total body weight (Fig. 9C) showed lower values for db/db and CF db/db mice, which appear skewed by including large depots of energetically low adipose tissue.

Fig. 9.

Altered total (24-h composite) energy expenditure (EE) and substrate oxidation analysis showed significance differences in the db/db genotype. A: EE, normalized per animal (kcals·h−1·mouse−1). B: EE, normalized per kg body weight (kcals·h−1·kg body wt−1). C: EE, normalized per kg lean mass (kcals·h−1·kg LM −1). D: respiratory quotient. E: carbohydrate oxidation rate (kcals of substrate·h−1·kg body wt−1). F: lipid oxidation rate (kcals of substrate·h−1·kg body wt−1). Data are average ± SE. Linear regression model parameters are shown in corresponding panels. BW, body weight; CF, cystic fibrosis; WT, mice homozygous for the wild-type Cftr+/+ allele; LM, lean mass.

We previously reported elevated energy expenditure in 6-wk-old F508del mice, in contrast to the results here. To determine if this were an age or genotype effect, we repeated the evaluations in a subset of 6-wk-old R117H mice and found them to be significantly elevated (WT: 17.1 ± 0.7 vs. R117H: 22.5 ± 0.9, P < 0.05), in agreement with the previous F508del mice data (4). Overall, the db/db genotype lowered energy expenditure in CF mice, thus allowing for weight gain observed in these animals.

Indirect calorimetry can also provide information on substrate utilization, which could provide clues to why the CF mice were unable to accrue fat, such as when fed a high-fat diet. We next used respiratory quotient and calculations to infer specific substrate utilization rates.

Respiratory Quotient and Substrate Oxidation

Respiratory quotient (RQ), calculated as the ratio of V̇co2/V̇o2, reflects the substrates being utilized. When RQ approaches 1.0, carbohydrates are being preferentially oxidized and when RQ is closer to 0.7, lipids are being oxidized (19). As shown in Fig. 8D, both CF and CF db/db mice had higher RQ values, as compared with WT and db/db, respectively. This indicates that CF genotype, suggesting higher carbohydrate utilization by CF mice.

To model this further, we estimated rates of carbohydrate and lipid oxidation using published equations (19) that assume negligible protein oxidation. Shown in Fig. 9E, carbohydrate oxidation rates were estimated to be 22% higher in CF mice (WT: 37.7 ± 2.6 vs. CF: 46.0 ± 4.4 mg/day mouse). However, the db/db genotype reduced estimated oxidation rates by half or more (db/db: 14.2 ± 2.6 and CF db/db: 22.2 ± 2.0 mg/day mouse). Lipid oxidation rates were also estimated to be lower in both groups carrying db/db mutation, (WT: 13.9 ± 0.7, CF: 10.6 ± 1.0, db/db: 8.4 ± 0.5, CF db/db: 7.4 ± 0.7). Overall, absence of leptin signaling in both WT and CF mice appeared to lower oxidation rates of carbohydrates and lipids, thus allowing for weight accumulation, however, carbohydrate and total oxidation was estimated to be higher in CF animals when compared with db/db counterparts.

DISCUSSION

We previously showed that CF mice are able to absorb ingested nutrients similarly to non-CF mice, suggesting that the reduced growth and weight gain of these animals is not simply because of malabsorption and malnutrition (4). Our initial attempts to increase growth through a high-fat, high-calorie diet were unsuccessful, as this diet had very adverse effects on growth and survival of CF mice (unpublished observations). This suggests that simply increasing calories is not sufficient to promote growth in CF. Here we show that increasing caloric intake while disrupting a metabolic regulatory system, leptin signaling, resulted in CF mice with improved growth and substantial fat stores.

The observed effects could be due to increased fatty acid synthesis, deposition, or reduced catabolism as the db/db mouse is typically characterized by a rapid and marked increase in food intake (15), body weight and length (15, 48), insulin-stimulated lipid synthesis and deposition (48), high body fat (48), and low energy expenditure (3). To begin to understand the mechanisms involved, we examined each of these steps and found that fatty acid synthesis was increased in CF db/db mice but not nearly to the extent of db/db mice with WT CFTR. We found that fatty acid deposition was also increased and that this was comparable between db/db mice regardless of Cftr genotype.

Our experimental strategy also revealed an intermediate phenotype in CF db/db mice, a long CF-like delay in growth. Both CF and CF db/db mice had similar growth until approximately week 6 when the growth of CF db/db mice markedly increased. This suppression of growth corresponds with a delayed onset of hyperphagia, but the reasons for this are unclear. Getchell et al. (21) reported that db/db mice exhibit an unusual enhancement in olfactory function (~10 times faster food finding time), which contributes to the observed hyperphagia. In contrast, Grubb et al. (23) showed that CF mice exhibit lower olfactory function that may affect appetite and food intake. These findings, if combined, are one potential explanation of the delayed hyperphagic response observed in CF db/db mice, but hypothalamic involvement is also a likely explanation.

The delayed hyperphagia affected growth and accretion of adipose tissue DNL, because the latter is “activated” once the animals are weaned from low-carbohydrate, high-fat milk to high-carbohydrate, low-fat chow (47). CF db/db mice markedly increased their body weight (twofold), although, still lagged behind the db/db mice. Lower hepatic DNL rates in CF db/db mice compared with db/db could account for reduced adipose tissue deposition, characteristic of CF. We previously reported (4) low rates of fatty acid desaturation and elongation driven by low substrate. Here, we report db-linked, CF-independent increase desaturation and elongation pathways driven by the increased substrates (e.g., stearate and palmitoleate). Increased levels of palmitoleate and other fatty acids, resulting from palmitate elongation and desaturation, may play roles, beyond energy storage. For example, palmitoleate has been proposed as an important “adipokine” to improve insulin sensitivity, hepatic triglyceride clearance and inflammation. Overall, we found that the delayed-onset hyperphagia coincided with lower lipid synthesis in CF mice, regardless of leptin signaling. As shown here, absence of leptin receptor signaling allows CF adipose tissue to accrue TGs almost as well as non-CF tissue, again suggesting that malabsorption is not the major source of growth impairment in these animals. We previously reported that very little of newly synthesized hepatic fatty acids are deposited in CF adipose tissue. Our findings are consistent with dysregulated leptin receptor function, and suggesting that the adipose tissue itself is altered in CF.

Leptin is also an important modulator of linear growth (20), affecting bone elongation via increased bone mineral density, mineral content, and bone area (49). We therefore expected that the length of CF db/db mice would be augmented beyond that of CF mice. However, CF db/db mice did not increase their body length, whereas db/db mice grew ~10% longer. Le Henaff et al. (29) showed that F508del mice exhibited decreased bone formation via decreased mineral density and altered architecture, thus highlighting the importance of CFTR in bone growth. One explanation is that altered bone turnover present in CF mice was not affected by the removal of leptin signaling and is a Cftr-dependent mechanism, requiring further research.

With regard to catabolism, increased energy expenditure is an aspect of energy balance present in both patients with CF and mouse models. Elevated energy expenditure in patients with CF has been associated with pancreatic insufficiency, poor nutritional status, and advanced lung disease (33, 34, 41, 45). However, recent reports of elevated energy expenditure in infants and adults with CF with stable nutritional status and lung function suggest that other factors influence energy homeostasis in CF, independent of nutrition and lung health (14, 38). We reported elevated energy expenditure in CF (F508del) mice (12) in the absence of pancreatic insufficiency, malnutrition, or lung disease, thereby establishing a model to study the etiology of increased energy needs in CF. Removal of leptin signaling resulted in markedly lower energy expenditure and loss of circadian rhythm in both db/db and CF db/db mice as compared with WT and CF mice, as evidenced by lack of dark phase activity. This change allowed for weight gain in CF db/db mice. Additionally, we found that CF mice have elevated energy expenditure independent of their gut obstructive phenotype (unpublished data), indicating that elevated energy expenditure may be an intrinsic property of CF cells and tissues.

Assessment of catabolism in our study showed an age effect, where young CF mice (3–6 wk of age) exhibited higher energy expenditure than non-CF mice, but they converged at later ages (3–6 mo of age). Disruption of leptin signaling lowered both CF and non-CF mice to similar energy expenditure levels, albeit, CF db/db mice trending higher. However, an unanticipated observation was that the respiratory quotients were higher in CF and CF db/db mice indicating higher reliance on carbohydrates. Such substrate preference may partly explain lower survival of CF mice fed high-fat, low-carbohydrate (20%) diet (Fig. 1). Higher carbohydrate preference is consistent with previously reported findings in patients with CF (9). Using existing computational models (19), these results predict that carbohydrate oxidation is elevated in CF, independent of leptin receptor function, and that lipid oxidation is reduced. We propose a model in which lack of CFTR function suppresses the ability to switch effectively between fuel sources such that fatty acids are not effective fuels for CF. Our results also indicate that this model applies to energy storage in some regard, as a high-fat diet does not lead to increased fat stores in CF mice. If correct, this model has important clinical implications as high-fat diets are commonly prescribed for CF patients.

It is also apparent from the data presented here that CFTR function interacts directly or indirectly with leptin signaling, as the timing of hyperphagia and subsequent growth are very different between db/db mice with and without normal CFTR function. The effect of the leptin receptor mutation in mice with WT CFTR is already apparent at weaning, while in CF mice the effect is delayed by at least 2 wk (Fig. 2). Whether the effect is acting through adipocytes, hypothalamic neurons or other cell types is not yet clear and currently being investigated. Recent data by Davies et al. (13) show that the correction of Cftr signaling by ivacaftor resulted in significant weight gain in children with CF, indicating a functional link between Cftr function and pathways leading to changes in body composition and body weight. A recently established link between Cftr dysfunction and AMP kinase in epithelial cells (24) provides a framework for a possible mechanism of energy imbalance, as AMP kinase is a major regulator of energy homeostasis in adipose tissue (7). By uncovering the mechanisms by which Cftr dysfunction causes energy imbalance in CF mice, with eventual translation to CF patients, will help uncover specific targets for nutritional and pharmacological interventions.

In conclusion, we utilized a leptin receptor-linked genetic model of hyperphagia and obesity to uncover specific mechanisms of low growth in CF mouse models. We found that db-linked large increases in food intake were masked in CF mice leading to delayed increase in lipogenesis and overall less obesity. We also uncovered that low linear growth is a CF-specific phenotype that could not be overcome even with such a robust model as db/db. Additionally, CF db/db mice became obese, a phenotype never previously observed in CF mouse models. This indicates that adipose tissue in CF mice has a capacity to store large amounts of TGs when those are abundant for storage. The abundance of carbohydrates for lipogenesis and TGs for storage was provided by the robust decrease in energy expenditure and associated decrease in diurnal activity. This is especially relevant in CF because high energy expenditure is a CF-specific phenotype, prevalent in CF mouse models and CF patients. By removing leptin receptor signaling, we were able to overcome high energy expenditure in CF to allow fat accretion.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (grant nos. BEDERM14G0 and DRUMMR0) and NIH (grant no. R24-RR-032425).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

I.R.B. and K.S. conceived and designed research; I.R.B., G.P., M.O., J.P., A.P., and B.O.E. performed experiments; I.R.B., G.P., M.O., A.P., B.O.E., A.R.-P., and M.L.D. analyzed data; I.R.B., M.O., A.R.-P., C.A.F., and M.L.D. interpreted results of experiments; I.R.B., A.P., A.R.-P., C.A.F., and M.L.D. prepared figures; I.R.B. and M.L.D. drafted manuscript; I.R.B., M.P., C.A.F., and M.L.D. edited and revised manuscript; I.R.B. and M.L.D. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the shared resources of Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Core (U24 DK76174) and Imaging Research Core of the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland (UL1TR000439).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed ML, Ong KK, Thomson AH, Dunger DB. Reduced gains in fat and fat-free mass, and elevated leptin levels in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Acta Paediatr 93: 1185–1191, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb02746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arumugam R, LeBlanc A, Seilheimer DK, Hardin DS. Serum leptin and IGF-I levels in cystic fibrosis. Endocr Res 24: 247–257, 1998. doi: 10.1080/07435809809135532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates SH, Dundon TA, Seifert M, Carlson M, Maratos-Flier E, Myers MG JR. LRb-STAT3 signaling is required for the neuroendocrine regulation of energy expenditure by leptin. Diabetes 53: 3067–3073, 2004. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bederman I, Perez A, Henderson L, Freedman JA, Poleman J, Guentert D, Ruhrkraut N, Drumm ML. Altered de novo lipogenesis contributes to low adipose stores in cystic fibrosis mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 303: G507–G518, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00451.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bederman IR, Dufner DA, Alexander JC, Previs SF. Novel application of the “doubly labeled” water method: measuring CO2 production and the tissue-specific dynamics of lipid and protein in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E1048–E1056, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00340.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell SC, Saunders MJ, Elborn JS, Shale DJ. Resting energy expenditure and oxygen cost of breathing in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 51: 126–131, 1996. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.2.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bijland S, Mancini SJ, Salt IP. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in adipose tissue metabolism and inflammation. Clin Sci (Lond) 124: 491–507, 2013. doi: 10.1042/CS20120536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boguszewski MC, Kamoi TO, Bento Radominski R, Boguszewski CL, Rosberg S, Filho NA, Sandrini Neto R, Albertsson-Wikland K. Insulin-like growth factor-1, leptin, body composition, and clinical status interactions in children with cystic fibrosis. Horm Res 67: 250–256, 2007. doi: 10.1159/000098480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowler IM, Green JH, Wolfe SP, Littlewood JM. Resting energy expenditure and substrate oxidation rates in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child 68: 754–759, 1993. doi: 10.1136/adc.68.6.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchdahl RM, Cox M, Fulleylove C, Marchant JL, Tomkins AM, Brueton MJ, Warner JO. Increased resting energy expenditure in cystic fibrosis. J Appl Physiol (1985) 64: 1810–1816, 1988. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.5.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen RI, Tsang D, Koenig S, Wilson D, McCloskey T, Chandra S. Plasma ghrelin and leptin in adult cystic fibrosis patients. J Cyst Fibros 7: 398–402, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry 2009 Annual Data Report. Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Registry, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darrah RJ, Bederman IR, Mitchell AL, Hodges CA, Campanaro CK, Drumm ML, Jacono FJ. Ventilatory pattern and energy expenditure are altered in cystic fibrosis mice. J Cyst Fibros 12: 345–351, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies JC, Wainwright CE, Canny GJ, Chilvers MA, Howenstine MS, Munck A, Mainz JG, Rodriguez S, Li H, Yen K, Ordoñez CL, Ahrens R; VX08-770-103 (ENVISION) Study Group . Efficacy and safety of ivacaftor in patients aged 6 to 11 years with cystic fibrosis with a G551D mutation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 1219–1225, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0153OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies PS, Erskine JM, Hambidge KM, Accurso FJ. Longitudinal investigation of energy expenditure in infants with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Clin Nutr 56: 940–946, 2002. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Luca C, Kowalski TJ, Zhang Y, Elmquist JK, Lee C, Kilimann MW, Ludwig T, Liu SM, Chua SC JR. Complete rescue of obesity, diabetes, and infertility in db/db mice by neuron-specific LEPR-B transgenes. J Clin Invest 115: 3484–3493, 2005. doi: 10.1172/JCI24059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohoo IMW, Stryhn H. Cohort studies. In: Veterinary Epidemiologic Research. University of Prince Edward Island, AVC, Inc., 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226: 497–509, 1957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frayn KN. Calculation of substrate oxidation rates in vivo from gaseous exchange. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 55: 628–634, 1983. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.2.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gat-Yablonski G, Phillip M. Leptin and regulation of linear growth. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 11: 303–308, 2008. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f795cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Getchell TV, Kwong K, Saunders CP, Stromberg AJ, Getchell ML. Leptin regulates olfactory-mediated behavior in ob/ob mice. Physiol Behav 87: 848–856, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girardet JP, Tounian P, Sardet A, Veinberg F, Grimfeld A, Tournier G, Fontaine JL. Resting energy expenditure in infants with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 18: 214–219, 1994. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199402000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grubb BR, Rogers TD, Kulaga HM, Burns KA, Wonsetler RL, Reed RR, Ostrowski LE. Olfactory epithelia exhibit progressive functional and morphological defects in CF mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C574–C583, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00106.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallows KR, Fitch AC, Richardson CA, Reynolds PR, Clancy JP, Dagher PC, Witters LA, Kolls JK, Pilewski JM. Up-regulation of AMP-activated kinase by dysfunctional cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells mitigates excessive inflammation. J Biol Chem 281: 4231–4241, 2006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson LB, Doshi VK, Blackman SM, Naughton KM, Pace RG, Moskovitz J, Knowles MR, Durie PR, Drumm ML, Cutting GR. Variation in MSRA modifies risk of neonatal intestinal obstruction in cystic fibrosis. PLoS Genet 8: e1002580, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hidalgo B, Goodman M. Multivariate or multivariable regression? Am J Public Health 103: 39–40, 2013. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson DH, Narayan S, Wilson DL, Flask CA. Body composition analysis of obesity and hepatic steatosis in mice by relaxation compensated fat fraction (RCFF) MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 35: 837–843, 2012. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katanik J, McCabe BJ, Brunengraber DZ, Chandramouli V, Nishiyama FJ, Anderson VE, Previs SF. Measuring gluconeogenesis using a low dose of 2H2O: advantage of isotope fractionation during gas chromatography. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284: E1043–E1048, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00485.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Henaff C, Gimenez A, Haÿ E, Marty C, Marie P, Jacquot J. The F508del mutation in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene impacts bone formation. Am J Pathol 180: 2068–2075, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Jeanrenaud B. Pre- and postweaning studies on development of obesity in mdb/mdb mice. Am J Physiol 234: E568–E574, 1978. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.234.6.E568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malik RC. Genetic and physiological aspects of growth, body composition and feed efficiency in mice: a review. J Anim Sci 58: 577–590, 1984. doi: 10.2527/jas1984.583577x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marín VB, Velandia S, Hunter B, Gattas V, Fielbaum O, Herrera O, Díaz E. Energy expenditure, nutrition status, and body composition in children with cystic fibrosis. Nutrition 20: 181–186, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moudiou T, Galli-Tsinopoulou A, Nousia-Arvanitakis S. Effect of exocrine pancreatic function on resting energy expenditure in cystic fibrosis. Acta Paediatr 96: 1521–1525, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Rawe A, McIntosh I, Dodge JA, Brock DJ, Redmond AO, Ward R, Macpherson AJ. Increased energy expenditure in cystic fibrosis is associated with specific mutations. Clin Sci (Lond) 82: 71–76, 1992. doi: 10.1042/cs0820071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrie A, Watson P. Statistics for Veterinary and Animal Sciences. Blackwell Science. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petro AE, Cotter J, Cooper DA, Peters JC, Surwit SJ, Surwit RS. Fat, carbohydrate, and calories in the development of diabetes and obesity in the C57BL/6J mouse. Metabolism 53: 454–457, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg LA, Schluchter MD, Parlow AF, Drumm ML. Mouse as a model of growth retardation in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Res 59: 191–195, 2006. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000196720.25938.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selvadurai HC, Allen J, Sachinwalla T, Macauley J, Blimkie CJ, Van Asperen PP. Muscle function and resting energy expenditure in female athletes with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 1476–1480, 2003. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-363OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shepherd RW, Holt TL, Vasques-Velasquez L, Coward WA, Prentice A, Lucas A. Increased energy expenditure in young children with cystic fibrosis. Lancet 331: 1300–1303, 1988. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)92119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stata Press Stata Multilevel Mixed-Effects Reference Manual. College Station, TX: Stata Press, 2013, p. 371. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinkamp G, Rühl IB, Müller MJ, Schmoll E, von der Hardt H. Increased resting energy expenditure in malnourished patients with cystic fibrosis. Acta Univ Carol Med (Praha) 36: 177–179, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stylianou C, Galli-Tsinopoulou A, Koliakos G, Fotoulaki M, Nousia-Arvanitakis S. Ghrelin and leptin levels in young adults with cystic fibrosis: relationship with body fat. J Cyst Fibros 6: 293–296, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Surwit RS, Feinglos MN, Rodin J, Sutherland A, Petro AE, Opara EC, Kuhn CM, Rebuffé-Scrive M. Differential effects of fat and sucrose on the development of obesity and diabetes in C57BL/6J and A/J mice. Metabolism 44: 645–651, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90123-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomson MA, Wilmott RW, Wainwright C, Masters B, Francis PJ, Shepherd RW. Resting energy expenditure, pulmonary inflammation, and genotype in the early course of cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 129: 367–373, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tomezsko JL, Stallings VA, Kawchak DA, Goin JE, Diamond G, Scanlin TF. Energy expenditure and genotype of children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Res 35: 451–460, 1994. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Towle HC, Kaytor EN, Shih HM. Regulation of the expression of lipogenic enzyme genes by carbohydrate. Annu Rev Nutr 17: 405–433, 1997. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.17.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trayhurn P, Wusteman MC. Lipogenesis in genetically diabetic (db/db) mice: developmental changes in brown adipose tissue, white adipose tissue and the liver. Biochim Biophys Acta 1047: 168–174, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90043-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Upadhyay J, Farr OM, Mantzoros CS. The role of leptin in regulating bone metabolism. Metabolism 64: 105–113, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaisman N, Clarke R, Pencharz PB. Nutritional rehabilitation increases resting energy expenditure without affecting protein turnover in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 13: 383–390, 1991. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ward SA, Tomezsko JL, Holsclaw DS, Paolone AM. Energy expenditure and substrate utilization in adults with cystic fibrosis and diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr 69: 913–919, 1999. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilke M, Buijs-Offerman RM, Aarbiou J, Colledge WH, Sheppard DN, Touqui L, Bot A, Jorna H, de Jonge HR, Scholte BJ. Mouse models of cystic fibrosis: phenotypic analysis and research applications. J Cyst Fibros 10, Suppl 2: S152–S171, 2011. doi: 10.1016/S1569-1993(11)60020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zigman JM, Elmquist JK. Minireview: From anorexia to obesity–the yin and yang of body weight control. Endocrinology 144: 3749–3756, 2003. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]