Abstract

B’More Healthy Communities for Kids was a multi-level, multi-component obesity prevention intervention to improve access, demand and consumption of healthier foods and beverages in 28 low-income neighborhoods in Baltimore City, MD. Process evaluation assesses the implementation of an intervention and monitor progress. To the best of our knowledge, little detailed process data from multi-level obesity prevention trials have been published. Implementation of each intervention component (wholesaler, recreation center, carryout restaurant, corner store, policy and social media/text messaging) was classified as high, medium or low according to set standards. The wholesaler component achieved high implementation for reach, dose delivered and fidelity. Recreation center and carryout restaurant components achieved medium reach, dose delivered and fidelity. Corner stores achieved medium reach and dose delivered and high fidelity. The policy component achieved high reach and medium dose delivered and fidelity. Social media/text messaging achieved medium reach and high dose delivered and fidelity. Overall, study reach and dose delivered achieved a high implementation level, whereas fidelity achieved a medium level. Varying levels of implementation may have balanced the performance of an intervention component for each process evaluation construct. This detailed process evaluation of the B’More Healthy Communities for Kids allowed the assessment of implementation successes, failures and challenges of each intervention component.

Introduction

Obesity rates remain high among minority youth in the United States; 20% of African-American children and adolescents have obesity compared with 15% of non-Hispanic white children [1]. Food environments can influence diet quality [2], thus contributing to high obesity rates. Access to healthy foods is challenging for low-income, underserved children and adolescents because high-fat and sugar foods are the least expensive and most accessible foods in those neighborhoods [3–5]. In Baltimore, approximately 42.1% of residents live at or below 185 percent of the Federal Poverty Level and 30% of children live in a food desert zone (i.e. more than 1/4 mile from a supermaket) [6].

Multi-level, multi-component (MLMC) interventions work to address the complex contributors to high obesity rates among children, especially low-income minority youth [1, 3, 4]. By simultaneously intervening in several settings, MLMC interventions integrate environmental factors with educational interventions and policy changes, which may lead to reduced obesity risk [7–11]. Previous MLMC studies intervening in community settings, recreation centers and schools have shown promising results. Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones was a youth-targeted MLMC intervention that worked with recreation centers, corner stores and carryout restaurants in Baltimore City [10] and was associated with significant reductions in youth body mass index (BMI) percentile. Subgroup analyses in girls with overweight and obesity revealed a significant decrease in BMI for age percentile in the intervention group and in girls with high exposure to the intervention, compared with the control or lower exposure group [12]. Another intervention, Shape up Somerville, took place from 2002 to 2005 and targeted both parents and children. This intervention achieved reduced BMI in adults, reduced BMI z-scores in children, decreased consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and screen time, and increased physical activity levels in children [9, 13–15]. The Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration (CORD) multi-site projects intervened in primary care, early childhood education and community settings [11]. Impact results demonstrated significant reductions in BMI and behaviors such as screen time and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among children [16–19].

To address the challenge of managing various intervention components and levels, process evaluation assesses whether an intervention trial is implemented according to pre-intervention set standards and can be used to monitor progress during an MLMC trial [20]. To the best of our knowledge, little detailed process data from multi-level obesity prevention trials using the Social Ecological Model have been published. However, examples from the literature demonstrate the potential of process evaluation to assist in MLMC intervention delivery and impact evaluation [9–11]. For instance, process evaluation results of Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones showed overall high reach and dose but moderate fidelity in terms of intervention delivery at the store level and suggested that the addition of a food policy and wholesaler component could improve access to healthier foods in corner stores and carryout restaurants in a more sustainable manner [10].

The CORD projects shared a common process evaluation framework across the multiple sites to assess reach, dose delivered and fidelity [11, 21]. The California CORD project used process evaluation to engage stakeholders, minimize policy resistance and maximize desired intervention outcomes [22]. The Massachusetts and California CORD linked process evaluation results to intervention outcomes, exploring exposure, quality of delivery, fidelity, participant responsiveness and differentiation (i.e. identification of core versus peripheral intervention components) [23]. In the Texas CORD process evaluation results, the reduction in BMI percentile in the intensive phase was strongly influenced by dosage. Fidelity during the intensive phase showed that 86%, 86% and 88% of the sessions were delivered completely as planned for age groups 2–5, 6–8 and 9–12 years, respectively [16].

B’More Healthy Communities for Kids (BHCK) was an MLMC obesity prevention intervention expanding upon previous work by intervening in food environment, individual and policy levels, including small corner stores, recreation centers, carryout restaurants, wholesalers, social media/text messaging and local policymakers. The intervention worked to improve access, demand and consumption of healthier foods and beverages in 28 low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhoods in Baltimore City. The target population for this trial was 10- to 14-year-old low-income, African-American youth [24].

This research assesses the BHCK MLMC intervention implementation through the following questions:

How well was each intervention component implemented in terms of reach, dose delivered and fidelity, compared with set standards and across components?

What are the implications of varying implementation quality when assessing overall intervention quality and impact?

Materials and methods

Setting

The BHCK study took place in Baltimore City, MD. The city has approximately 654 corner stores, 316 convenience stores, 50 supermarkets, 6 public markets [25] and 40 recreation centers [26].

BHCK intervention trial

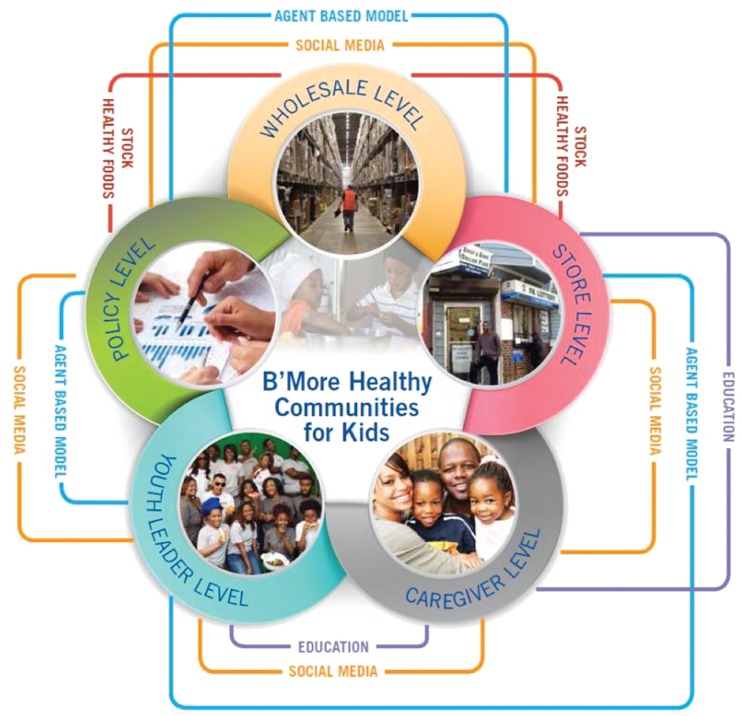

BHCK intervened simultaneously in multiple levels of the food environment to improve access, demand and consumption of healthier foods and beverages in 28 low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhoods in Baltimore City, using a group randomized controlled design (Figure 1). Twenty-eight low-income neighborhood zones were randomized as intervention (n = 14) or comparison (n = 14) zones. These zones were centered around a recreation center with a 1.5-mile radius surrounding the center, contained at least five small food stores (<3 aisles and no seats), and were located more than � mile away from a supermarket (food desert). All zones were low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhoods. BHCK study participants were child-caregiver dyads who lived in these zones. The underlying theories that informed this work include the Social Cognitive Theory, Social Ecological Model and Systems Theory [27–29] utilizing the various levels of the food system and environment, as well as individual factors to achieve behavior change. A more comprehensive description of the study design can be found elsewhere [24]. The research protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Fig. 1.

BHCK intervention components.

Following formative research to identify promoted foods and build stakeholder relationships, the intervention was delivered in two waves by trained interventionists. Wave 1 took place between July 2014 and February 2015 and Wave 2 between November 2015 and July 2016. Each wave was divided into three phases highlighting different themes: healthy beverages, snacks and cooking methods (Table I). Each phase integrated the different components of the programme and was approximately 2 months long with 2-week subphases. Wave 2 contained a fourth review phase in corner stores and wholesalers to review content from sessions with very low reach due to winter weather. Phases were adjusted in Wave 2 due to seasonality. For example, in Wave 2, the beverages phase was moved to the last phase so that the team was not promoting cold beverage samples during the winter.

Table I.

Phases and activities of the B’More Healthy Communities for Kids intervention

| Phase | Educational messages/promoted foods | Phase-specific giveaways | Policy and environmental changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1. Smart drinks |

|

|

|

| Phase 2. Smart snacks |

|

|

|

| Phase 3. Smart cooking/breakfast |

|

|

|

| Phase 4. Review phase (Wave 2 corner stores and wholesalers only) | Reviewed material from sessions that had low reach:

|

Sandwich keeper, portion bowl, chip clips |

|

Description of intervention components

All intervention components were implemented simultaneously, except for the Policy Working Group, which began during the formative phase and was ongoing.

Wholesaler component

Aimed to increase small store owners’ access to promoted foods through improved stocking and labeling of BHCK-promoted foods lower in sugar and fat, as well as provision of gift cards and discounts [30]. BHCK worked with three wholesaler locations in Baltimore City, which supply surrounding corner stores and carryout restaurants.

Corner store component

Aimed to increase both supply and demand of healthier foods and beverages in intervention neighborhoods through wholesaler store gift cards, training videos for owners, point of purchase promotion and educational interactive sessions for customers [30].

Carryout restaurant component

Similar in design to the corner store component, but included menu redesign and cooking demonstrations for owners [31].

Recreation center/peer mentor component

Involved a 14-week nutrition curriculum developed in partnership with a youth-led community-based organization and adapted pre-existing nutrition resources (e.g. the Food & Fun After-School curriculum [32]). Youth leaders (college and high-school students from Baltimore City) delivered this curriculum every 2 weeks, beginning each session with a discussion of learning outcomes, followed by an experiential learning activity and ending with a taste test or cooking demonstration to children (10–14 years old) in intervention after-school programmes [33].

Social media/text messaging component

Aimed to reach caregivers and reinforce material delivered in recreation centers and stores. Bidirectional text messages (i.e. participants could respond to messages and receive an automated response from the study team) were sent three times per week to the intervention sample (those living in the intervention zones) and included goal-setting material related to the phase. Daily posts were made on BHCK Facebook and Instagram accounts to supplement text messages with content such as recipes and real-time notifications of intervention activities (e.g. corner store interactive sessions). Monthly challenges and giveaways on Instagram aimed to increase engagement. Twitter was utilized to reach caregivers in Wave 1, but based on process evaluation revealing low reach, it was repurposed to reach policymakers and community partners in Wave 2 [34].

Policy component

Aimed to institutionalize components of BHCK at the city level and to provide evidence supporting local policies through quarterly stakeholder meetings [35]. The Policy Working Group also introduced an agent-based model (ABM) that simulated Baltimore food policies and its impact on local environments to inform decision making [36, 37].

Process evaluation

BHCK process evaluation assessed reach, dose delivered and fidelity of each component [20]. The study team developed a priori implementation standards (Table II) based on previous experience with programme implementation in Baltimore [10]. Research team members met every other month during implementation to discuss progress, address challenges and adjust delivery. Slight adjustments were made to standards before Wave 2, therefore the final Wave 2 standards were used to assess implementation of both waves (Table II).

Table II.

Description of sample BHCK high standards per component

| Intervention component | Sample reach (set-standard) | Sample dose delivered (set-standard) | Sample Fidelity (set-standard) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wholesalers | No. of wholesalers participating: (>2) |

|

|

| Corner stores |

|

|

|

| Carryouts |

|

|

|

| Recreation centers (mentoring programme) |

|

|

|

| Social media/text messaging |

|

|

|

| Policy |

|

|

|

Tracked number of children between 10 and 14 years old.

Tracked number of adults >18 years old.

The following definitions were used:

Reach: Number of people in the intended target audience who participated in each intervention component [20]. Reach was measured at individual and institutional levels.

Dose delivered: Amount of units (e.g. minutes, number of handouts) of each intervention component provided by BHCK interventionists [20].

Fidelity: Assessed the quality of intervention component implementation based on reactions to or engagement with the programme.

Process evaluation training and reporting

Process evaluation data collectors were distinct from those delivering the intervention, except in the case where forms needed to be completed by the interventionist such as gathering participant reactions to taste tests in corner stores and carryout restaurants. The certification process for data collectors included 5–6 hours of training, role-play and supervised practice.

Instruments

All process evaluation instruments were modified from previous environmental trials conducted in Baltimore [10, 38–40].

Corner store/carryout/wholesaler environmental assessment

This assessment was a modified version of the original Nutrition Environment Measures Study (NEMS) tool [41]. Trained data collectors conducted monthly structured observations at the corner store, carryout and wholesaler levels to assess maintenance of communication materials (e.g. BHCK shelf labels and posters), healthy food availability and state of the store environment (e.g. lighting and cleanliness). Data collectors also measured number of promoted foods present on carryout restaurant menus and promoted foods featured in wholesaler circular advertisements [30, 31].

Corner store/carryout/wholesaler visit form

Interventionists completed visit forms monthly at stores and carryout restaurants and three times per phase at wholesalers to assess the number (reach) and length (dose delivered) of meetings with the store owner or wholesaler representatives. These forms were also completed as needed if additional visits occurred such as video training sessions with owners, and additional feedback on intervention activities was given [30, 31].

Corner store/carryout interventionist form

This form was completed every other week in each location by interventionists and measured the number of communication materials such as posters, shelf labels, handouts and giveaways distributed and hung during interactive sessions (dose delivered), taste test acceptance, number and duration (10–60 s or >1 min) of interactions with youth and their caregivers (reach), the number and type of interactive display boards used, and session overall outcome [30, 31].

Recreation center interventionist form

This form was completed by a data collector during each recreation center educational session (every 2 weeks). It captured reach, dose delivered and fidelity, including duration of the session (minutes), number of youth leaders and children within the target age range present, number of BHCK posters hung, materials distributed to children and curriculum components covered [33].

Social media/text messaging analytics

Facebook, Instagram and Twitter process evaluation data were derived from online tracking platforms such as Facebook Insights, Iconosquare and Twitter Analytics by two social media interventionists on a weekly, monthly or by phase basis depending on the process evaluation standard. Data from text messaging were extracted from the online texting programmes: Textit in Wave 1 and EZText/MobileVip in Wave 2. All data were recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet [34].

Policy tracking form and meeting reports

Data collectors tracked meeting action items, attendance and other process evaluation standards in quarterly meeting reports and internal weekly meeting minutes. Process measures were later compiled and analyzed annually [35].

Score development/data analysis

Implementation scores were developed for each process evaluation construct (reach, dose delivered and fidelity), for all components after each phase. The mean of the three phases was used to calculate a score per intervention component. Overall study reach, dose delivered and fidelity were also determined.

First, to obtain the percentage met of each set standard, we divided the individual process measure by the set standard and multiplied it by 100. Then, those scores within each process evaluation construct in each component were averaged to determine the percentage score for each process evaluation construct in each study component and classified as high, medium or low. High intervention delivery was defined as the process evaluation construct meeting ≥100% of the set standard. Medium implementation was defined as 50–99.9% of high standard, and low implementation was <50% of the high standard. Additionally, a component implementation score of each BHCK intervention component was developed by averaging the reach, dose delivered and fidelity scores. Finally, we determined an overall study score by averaging all reach, dose delivered and fidelity percentage scores for all five components. All process data were entered and analyzed in Microsoft Excel 2013. This analysis was based on methods developed in previous process evaluation research by the study team [30].

Results

Summary

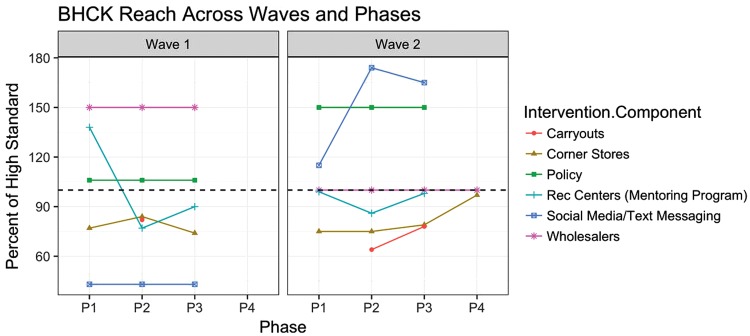

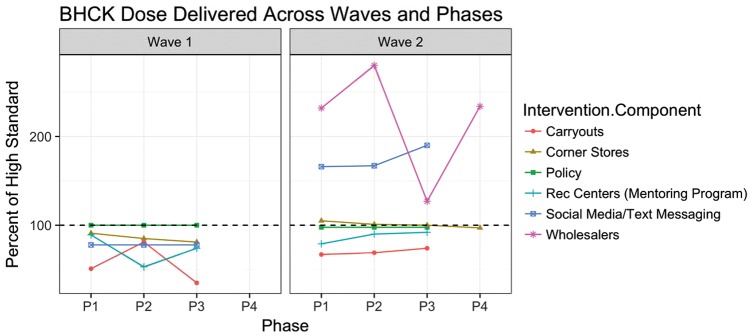

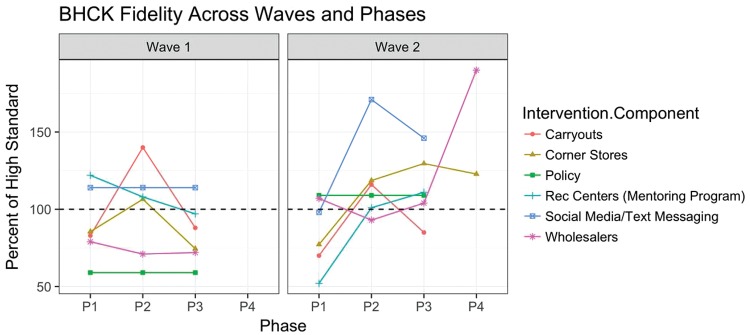

Wholesaler, policy and social media/text messaging components had the highest level of implementation quality, as these components achieved a component implementation score ≥100%. Recreation center, carryout and corner store components were classified in the medium level of component implementation score. No components achieved a low component implementation score. Overall, study reach and dose delivered achieved a high implementation level, whereas fidelity achieved a medium level. Process evaluation results for reach, dose delivered and fidelity by wave and phase for all study components can be found in Figures 2–4, respectively.

Fig. 2.

BHCK reach across all phases. Graph depicts average percent of the high standard for all reach process evaluation data for each intervention component. Dotted line marks the high level of implementation at 100%. Phase 4 occurred in Wave 2 only.

Wholesaler

All reach, dose delivered and fidelity measures met a high level of implementation. The reach for this component achieved an average of 121%, ranging from 100% to 150% of the high standard (Figure 2). The dose delivered achieved an average of 218%, ranging from 127% to 280% across all waves and phases (Figure 3). Fidelity achieved an average of 102%, ranging from 71% to 190% (Figure 4). Reach remained high across waves, with a slight decrease during Wave 2. Fidelity improved from medium to high from Wave 1 to Wave 2. Dose delivered remained at a high level across phases in Wave 2.

Fig. 3.

BHCK dose delivered across all phases. Graph depicts average percent of the high standard for all dose delivered process evaluation data for each intervention component. Dotted line marks the high level of implementation at 100%. Phase 4 occurred in Wave 2 only.

Fig. 4.

BHCK fidelity across all phases. Graph depicts average percent of the high standard for all fidelity process evaluation data for each intervention component. Dotted line marks the high level of implementation at 100%. Phase 4 occurred in Wave 2 only.

Corner stores

The reach for the corner store component achieved a medium level of implementation, averaging 80% and ranging from 74% to 97% of the high standard across all waves and phases (Figure 2). The dose delivered achieved a medium level of implementation averaging 94%, ranging from 81% to 105% (Figure 3). Fidelity achieved a high level of implementation averaging 102%, ranging from 75% to 130% (Figure 4). Corner store dose delivered and fidelity increased from medium in Wave 1 to high in Wave 2, whereas reach remained at a medium level.

Carryout restaurants

The reach for the carryout restaurant component achieved a medium level of implementation with an average of 75% of the high standard, ranging from 64% to 82% across the waves and phases (Figure 2). The dose delivered achieved a medium level of implementation with an overall average of 63%, ranging from 35% to 81% (Figure 3). Fidelity achieved a medium level of implementation with an overall average of 97% and ranged from 70% to 140% (Figure 4). Reach and dose delivered remained medium across phases, and fidelity fluctuated between medium and high across all phases.

Recreation centers/peer mentor

The reach for the recreation center component achieved a medium level of implementation, averaging 98% and ranging from 77% to 138% of the high standard across all waves and phases (Figure 2). The dose delivered achieved a medium level of implementation averaging 80%, ranging from 53% to 92% across phases (Figure 3). Fidelity achieved a medium level of implementation, averaging 99%, ranging from 52% to 122% (Figure 4). Over time, reach in the recreation centers decreased from high to medium, dose delivered remained medium, and fidelity fluctuated between high and medium.

Social media/text messaging

The reach for the social media/text messaging component achieved a medium level of implementation, averaging 97%, ranging from 43% to 174% of the high standard across all waves and phases (Figure 2). The dose delivered achieved a high level of implementation, averaging 126%, ranging from 78% to 190% (Figure 3). Fidelity achieved a high level of implementation averaging 127%, ranging from 89% to 171% (Figure 4). Social media/text messaging dose delivered remained high across all waves and phases, and reach and fidelity improved from medium to high.

Policy

The reach for the policy component met a high level of implementation, averaging 128% and ranging from 106% to 150% of the high standard across phases (Figure 2). Year 1 overlapped with the formative phase of BHCK, and is not shown in the figures. The dose delivered achieved a medium level of implementation, averaging 99% and ranging from 98% to 100% across phases (Figure 3). Fidelity achieved a medium level of implementation, averaging 84% and ranged from 59% to 109% across phases (Figure 4). Reach and fidelity increased over time from medium to high. Dose delivered decreased from high to medium.

Discussion

This study is the first to present detailed process data from all components of an MLMC obesity prevention trial in a low-income, urban setting. Process evaluation is a key component of intervention evaluation and is needed to inform impact measures. Using a priori standards during intervention implementation provided ongoing feedback to the research team about the quality of each component delivered and allowed for midcourse corrections to intervention delivery. We consider this best practice in public health education and environmental interventions. Linnan and Steckler suggest that corrective feedback for intervention implementation as well as sharing of success with team members is possible when process evaluation reports are generated on a regular basis. Further, in the process for designing and implementation effective process evaluation efforts, reports on process measures create a feedback loop to refine theory, interventions and measurement [20]. Policy, wholesaler and social media/text messaging represented novel components in this study and expanded on our previous work [10, 42–44]. These findings support the reinforcing nature of the various intervention components, where ideally, poor performance in one component for one process evaluation construct can be balanced by better performance in another component for that same process evaluation construct, thus improving the overall intervention implementation score.

Result trends by component

Other MLMC interventions have utilized process evaluation to provide context for implementation and interpretation of study impact [10, 11, 21]. Our overall results for reach, dose delivered and fidelity are consistent with those found in a similar MLMC trial in Baltimore (Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones) [10]. Medium fidelity at the carryout restaurant, corner store and recreation center levels could be due to store closures, change in store ownership, language barriers, youth leader availability and transportation issues. These barriers were consistent with other MLMC trials in low-income populations, as these components are more burdensome to implement and depend heavily on store owner and youth schedules [10, 22, 45].

Wholesalers

Although reach at the wholesaler level remained high during Waves 1 and 2, a slightly decreased reach in Wave 2 was due to a management change at one of the wholesalers, reducing their ability to contribute adequate time to the programme and stock new products. Wave 1 did not capture dose delivered, but the high standard was met during Wave 2 of the intervention due to improved communication with wholesalers and tracking methods. Fidelity at the wholesaler level improved across waves due to an overall increase in promoted foods stocked and correct label placement. Years of developing relationships with local wholesalers and maintaining consistent communication with a fixed point of contact contributed to the overall success of the wholesaler component [38].

Corner stores

Reach in corner stores remained at a medium level and was low during winter months. Weather conditions and safety concerns affected reach to target youth at corner stores, limiting times staff could safely be in stores before foot traffic and drug activity increased in the evening. Corner store dose delivered and fidelity increased across waves due to increased participation in store owner training, promoted food stocking and correct label placement. Average total interactions (including adults) were similar, if not higher to that of another corner store study in Baltimore [40].

Carryout restaurants

The reach for the carryout restaurant component had a wide range due to fewer standards in Wave 1, but increased in Wave 2 with additional measures added and more sessions occurring due to owner availability. Weather conditions and safety concerns affected reach to target youth at carryouts similar to corner stores. Challenges in working with small store and carryout owners, specifically fear of loss of profits and lack of time or interest were similar to those of Shape Up Somerville [46].

Recreation centers

Dose delivered improved over time in recreation centers through more consistent distribution of materials and improved behavioral management assistance from recreation center staff. Reach decreased, due to starting the intervention during the summer. During this time, recreation centers hold summer camps, yielding higher enrollment than during the school year. Weather conditions in the winter also affected the reach at recreation center sessions. BHCK youth leaders were local high school and college students with competing demands on their time, which caused challenges in scheduling [47]. These conflicts were similar to those found in Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones [10].

Social media/text messaging

Between Waves 1 and 2, the study team introduced new strategies for social media, including targeted, paid boosting campaigns and a consistent weekly posting schedule, which increased reach, dose delivered and fidelity for Wave 2. Unlike other components, social media and text messaging delivery relied less on external factors such as weather and customers entering a store. Challenges existed in receiving limited input for content from youth leaders and low number of followers submitting entries for challenges.

Policy

Policy process evaluation measures were affected by change in leadership of the Policy Working Group and changes in city council representation. Fidelity increased from medium to high due to development of the ABM over time.

Implications of process evaluation in MLMC trial implementation

Several challenges exist in implementing and evaluating MLMC interventions, as it is difficult to demonstrate the relationships between components [48]. This study strove to address this challenge by utilizing social media/text messaging as the reinforcing ‘glue’, promoting content from all components to programme participants. Additionally, BHCK process evaluation facilitated discussion of strategies to improve intervention delivery during regular process evaluation update meetings as well as follow up in weekly team meetings.

Difficulty also exists in implementing multiple components simultaneously and tracking many process evaluation measures. Other MLMC interventions such as the CORD projects have developed detailed process evaluation frameworks [11]. Further, process evaluation results of the Texas CORD project reported fidelity as attendance (instructor reported engagement and attendance) [16]. However, BHCK was unique in the frequency of regular feedback from the process evaluation team to research staff based on set standards to make course corrections to intervention delivery. The use of set process evaluation standards and regular meetings improved study team communication and helped address challenges during trial implementation, created synergy between components, and improved adherence to study protocols. In a three-case comparison of MLMC interventions, BHCK’s process evaluation proved to be much more detailed and rigorous in the assessment of each intervention component and amount of feedback provided to researchers throughout implementation, as compared with the SOL-Health and Local Community Programme, which did not conduct process evaluation and Children’s Healthy Living programme, which provided the monthly reports to intervention communities regarding measures such as reach, acceptability and adoption [48].

Implications of varying implementation quality

Varying levels of implementation must be considered when assessing the overall impact of the intervention. Future MLMC trials should consider weighting different intervention components, dividing them into nutrition education (recreation centers), environmental (corner stores, carryouts and wholesalers), policy and social media/text messaging and assigning weights for the overall process evaluation score based on proximity of these components to individual behavior change. This has been assessed in other settings in terms of differentiation, which determines core intervention components that are essential and directly responsible for intervention effects as well as more periphery components [23].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Modifications to the intervention and standards between waves, though based on lessons learned, made data difficult to compare between waves. This was addressed by the percentage scoring system for ease of comparison and using final Wave 2 standards to evaluate both waves. Furthermore, research staff changes in between waves may have affected consistency of delivery. However, the same project coordinator oversaw both waves of implementation to ensure that changes were consistent with the original study design, a manual of procedures was developed to guide activities and report on lessons learned and all interventionists underwent intensive training. Finally, having interventionists collecting process evaluation data in some components (e.g. corner stores and carryouts) has potential for measurement bias.

Conclusions

Overall study reach and dose delivered achieved a high implementation level, and study fidelity achieved a medium level of implementation, due to the reinforcing nature of the individual component scores. BHCK plans include sustainability and expansion of the intervention components that were most successfully delivered such as the wholesaler, policy and social media/text messaging components. Our method of setting a priori standards and assessing process evaluation throughout the intervention to make course corrections to implementation is considered best practice in interventions [24]. The study team is currently sharing this process evaluation strategy with other public health professionals via webinars and trainings with state health departments. Although not all BHCK intervention components attained a high component implementation score, all components at a minimum achieved a medium component implementation score. Setting process evaluation standards and planning for regular feedback to the research team should be applied to the design of public health interventions to strengthen and improve reach, dose delivered and fidelity to contextualize impact analysis.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank additional study team members, including Elizabeth Anderson Steeves, Laura Hopkins, Anna Kharmats, Yeeli Mui, Andrew Seiden, Naomi Rapp, Donna Dennis, Thomas Eckmann, Maria Jose Mejia, Sarah Lange and Sarah Rastatter. They would also like to acknowledge our community partners Baltimore City Recreation and Parks, Living Classrooms, Baltimore corner store and carryout restaurant owners, B-green Cash and Carry, Baltimore Food Policy Initiative and other members of our Policy Working Group.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Global Obesity Prevention Center (GOPC) at Johns Hopkins and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (OD) under award number U54HD070725. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This work was also funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1U48DP000040, SIP 14-027).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG. et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA 2016; 315: 2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. D'Angelo H, Suratkar S, Song H-J. et al. Access to food source and food source use are associated with healthy and unhealthy food-purchasing behaviours among low-income African-American adults in Baltimore City. Public Health Nutr 2011; 14: 1632–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitchell NS, Catenacci VA, Wyatt HR. et al. Obesity: overview of an epidemic. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2011; 34:717–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borradaile KE, Sherman S, Vander Veur SS. et al. Snacking in children: the role of urban corner stores. Pediatrics 2009; 124:1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiszko K, Cantor J, Abrams C. et al. Corner store purchases in a low-income urban community in NYC. J Community Health 2015; 40:1084–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buczynski A, Freishtat H, Buzogany S. Mapping Baltimore City's Food Environment: 2015 Report. Johns Hopkins University Center for a Livable Future; Available at: http://mdfoodsystemmap.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/06/Baltimore-Food-Environment-Report-2015-11.pdf2015 Jun. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sabin MA, Kiess W.. Childhood obesity: current and novel approaches. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 29:327–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dooyema CA, Belay B, Foltz JL. et al. The childhood obesity research demonstration project: a comprehensive community approach to reduce childhood obesity. Child Obes 2013; 9:454–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Folta SC, Kuder JF, Goldberg JP. et al. Changes in diet and physical activity resulting from the Shape Up Somerville community intervention. BMC Pediatr 2013; 13:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gittelsohn J, Dennisuk LA, Christiansen K. et al. Development and implementation of Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones: a youth-targeted intervention to improve the urban food environment. Health Educ Res 2013; 28:732–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joseph S, Stevens AM, Ledoux T. et al. Rationale, design, and methods for process evaluation in the childhood obesity research demonstration project. J Nutr Educ Behav 2015; 47:560–5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shin A, Surkan PJ, Coutinho AJ. et al. Impact of Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones: an environmental intervention to improve diet among African American youth. Health Educ Behav 2015; 42:97S–105S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Goldberg JP. et al. A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape Up Somerville first year results*. Obesity 2007; 15:1325–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Must A. et al. Shape Up Somerville two-year results: a community-based environmental change intervention sustains weight reduction in children. Prev Med (Baltim) 2013; 57:322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coffield E, Nihiser AJ, Sherry B. et al. Shape Up Somerville: change in parent body mass indexes during a child-targeted, community-based environmental change intervention. Am J Public Health 2015; 105:e83–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Butte NF, Hoelscher DM, Barlow SE. et al. Efficacy of a community- versus primary care-centered program for childhood obesity: TX CORD RCT. Obesity 2017; 25:1584–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woo Baidal JA, Nelson CC, Perkins M. et al. Childhood obesity prevention in the Women, Infants, and Children Program: outcomes of the MA-CORD study. Obesity 2017; 25:1167–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Franckle RL, Falbe J, Gortmaker S. et al. Student obesity prevalence and behavioral outcomes for the Massachusetts Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration project. Obesity 2017; 25:1175–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taveras EM, Perkins M, Anand S. et al. Clinical effectiveness of the Massachusetts Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration initiative among low-income children. Obesity 2017; 25:1159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steckler AB, Linnan L.. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research, 2002. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- 21. O'Connor DP, Lee RE, Mehta P. et al. Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration project: cross-site evaluation methods. Child Obes 2015; 11:92–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chuang E, Brunner J, Moody J. et al. Factors affecting implementation of the California Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration (CA-CORD) Project, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis 2016; 13:E147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chuang E, Ayala GX, Schmied E. et al. Evaluation protocol to assess an integrated framework for the implementation of the Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration Project at the California (CA-CORD) and Massachusetts (MA-CORD) sites. 2015; 11:48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gittelsohn J, Anderson Steeves E, Mui Y. et al. B’More Healthy Communities for Kids: design of a multi-level intervention for obesity prevention for low-income African American children. BMC Public Health 2014; 14:942.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Center for a Livable Future. Maryland Food System Profile II. Baltimore, MD: 2016. Available at: http://mdfoodsystemmap.org/ Accessed: 10 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baltimore City Recreation and Parks. Available at: https://bcrp.baltimorecity.gov/recreationcenters. Accessed: 15 May 2018.

- 27. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W. et al. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health 2006; 27:297–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Engelwood, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schwendler T, Shipley C, Budd N. et al. Development and Implementation: B’More Healthy Communities for Kid’s store and wholesaler intervention. Health Promot Pract 2017; 18:822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perepezko K, Tingey L, Sato P. et al. Partnering with carryouts: implementation of a food environment intervention targeting youth obesity. Health Educ Res 2018; 33:4–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvard School of Public Health. School Tools Prevention Research Center on Nutrition and Physical Activity. Available at: http://www.foodandfun.org. Accessed: 24 March 2018.

- 33. Sato PM, Steeves EA, Carnell S. et al. A youth mentor-led nutritional intervention in urban recreation centers: a promising strategy for childhood obesity prevention in low-income neighborhoods. Health Educ Res 2016; 31:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Loh H, Schwendler T, Trude A. et al. Implementation of social media strategies within the multi-level B’More Healthy Communities for Kids childhood obesity prevention intervention. Inquiry 2018; 55:0046958018779189. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nam CS, Ross A, Ruggiero C. et al. Process evaluation and lessons learned from engaging local policymakers in the B’More Healthy Communities for Kids trial. Heal Educ & Behav 2018; 1090198118778323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gittelsohn J, Mui Y, Adam A. et al. Incorporating systems science principles into the development of obesity prevention interventions: principles, benefits, and challenges. Curr Obes Rep 2015; 4:174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gittelsohn J, Mui Y, Lin S. et al. Simulating the impact of an urban farm tax credit policy in a low income urban setting. Harvard Heal Policy Rev 2016; 15: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Budd N, Cuccia A, Jeffries JK. et al. B’More Healthy: retail rewards—design of a multi-level communications and pricing intervention to improve the food environment in Baltimore City. BMC Public Health 2015; 15:283.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee-Kwan SH, Goedkoop S, Yong R. et al. Development and implementation of the Baltimore healthy carry-outs feasibility trial: process evaluation results. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:638.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gittelsohn J, Suratkar S, Song H-J. et al. Process evaluation of Baltimore Healthy Stores: a pilot health intervention program with supermarkets and corner stores in Baltimore City. Health Promot Pract 2010; 11:723–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE. et al. Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in Stores (NEMS-S): development and evaluation. Am J Prev Med 2007; 32:282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Budd N, Jeffries JK, Jones-Smith J. et al. Store-directed price promotions and communications strategies improve healthier food supply and demand: impact results from a randomized controlled, Baltimore City store-intervention trial. Public Health Nutr 2017; 20:3349–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Song HJ, Gittelsohn J, Kim M. et al. A corner store intervention in a low-income urban community is associated with increased availability and sales of some healthy foods. Public Health Nutr 2009; 12:2060–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee-Kwan SH, Bleich SN, Kim H. et al. Environmental intervention in carryout restaurants increases sales of healthy menu items in a low-income urban setting. Am J Health Promot 2015; 29:357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Blaine RE, Franckle RL, Ganter C. et al. Using school staff members to implement a childhood obesity prevention intervention in low-income school districts: the Massachusetts Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration (MA-CORD Project), 2012–2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2017; 14:E03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Economos CD, Folta SC, Goldberg J. et al. A community-based restaurant initiative to increase availability of healthy menu options in Somerville, Massachusetts: Shape Up Somerville. Prev Chronic Dis 2009; 6: A102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Trude ACB, Anderson Steeves E, Shipley C. et al. A youth-leader program in Baltimore City recreation centers: lessons learned and applications. Health Promot Pract 2018; 19:75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mikkelsen B, Novotny R, Gittelsohn J.. Multi-Level, multi-component approaches to community based interventions for healthy living—a three case comparison. Int J Environ Res Public Heal 2016; 13:1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]