Abstract

Chronic diseases are the primary health burden among Mexican-origin populations and health promotion efforts have not been able to change negative population trends. This research presents behavioral and subjective health impacts of two related community health worker (CHW) interventions conducted in the US–Mexico border region. Pasos Adelante (United States) and Meta Salud (Mexico) are 12–13 week CHW-led preventive interventions implemented with Mexico-origin adults. Curricula include active learning modules to promote healthy dietary changes and increasing physical activity; they also incorporate strategies to promote social support, empowerment and group exercise components responsive to their communities. Questionnaire data at baseline (N = 347 for Pasos; 171 for Meta Salud), program completion and 3-month follow-up were analyzed. Results showed statistically significant improvements in multiple reported dietary, physical activity and subjective health indicators. Furthermore, at follow-up across both cohorts there were ≥10% improvements in participants’ meeting recommended physical activity guidelines, consumption of whole milk, days of poor mental health and self-rated health. While this study identifies some robust health improvements and contributes to the evidence base for these interventions current dissemination, the lack of change observed for some targeted behaviors (e.g. time sitting) suggests they may have stronger overall impacts with curricula refinement.

Introduction

Chronic disease is the leading causes of death and disability in the United States and Mexico [1]. Among both sides of the US–Mexico border the prevalence rates of obesity and diabetes are among the highest globally [2–4]. In the United States, the leading risk factor for lowered daily adjusted life years is high body mass index; and in Mexico, it is high glucose [5]. Despite public health mobilization efforts, the preponderance of data suggest obesity-related cancers, high blood pressure, high total cholesterol, high sodium intake, low fruit consumption, low vegetable consumption, low whole grain intake and low physical activity are worsening [6, 7]. An increasingly important strategy to address these comorbid risk factors is through interventions to promote healthy lifestyles and behaviors [7]; those delivered by community health workers (CHWs), or promotor/promotora in Spanish, show particular promise [8–10]. In this United States and globally, CHW interventions targeting cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes have been demonstrated as efficacious and cost-effective in promoting population health in diverse settings (e.g. clinical; community-based; government-based public health) [11–15]. Despite dissemination efforts for these evidence-based chronic disease interventions, the sustained negative population trends for Mexican-origin adults (particularly the cross-national diabetes epidemic) illustrate the urgency to explore enhancing their effectiveness.

Pasos Adelante (Steps Forward) is a CHW intervention developed to prevent chronic disease in Mexican-origin adults [16]. Pasos development was guided by social cognitive theory [17] and included adaptations from the 9-week, Su Coraz�n, Su Vida (Your Heart, Your Life), curriculum [18]. While drawing heavily on the latter’s dietary change modules [19], the final curriculum differed substantially as a consequence of community-based participatory processes. Pasos goals are to promote healthier diet and physical activity; however, they also include promoting empowerment (personal and community), emotional well-being and social support. The latter were expressed by community members as critical for sustained diet and physical activity change. Social walking clubs and intensive diabetes education prevention components are other core elements.

The finalized Pasos-12 week curriculum was evaluated in a rural US border community [16]. A randomized household survey [20] conducted in the same community showed lower obesity in the adult general population (40%) than those reporting Pasos participation (51%). The majority of Pasos participants [16] did not report having a chronic disease (e.g. 22% with diabetes), thus the sample matched the intervention’s primary prevention orientation.

Findings from this Pasos effectiveness evaluation showed positive change in clinical outcomes and quality of life [16, 21]. Relative to pre-intervention (baseline), at program conclusion (3 months after baseline) and 3-month follow-up (6 months after baseline), there were statistically significant improvements in body mass index, cholesterol, waist, blood pressure, glucose, quality of life and depressive symptoms. Magnitudes of change at follow-up include lowered glucose by 4.5 mg/dl (from 103) and depressive symptomatology lowered by 7% (from 32%). Results of this evaluation and related studies [22] led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2012 to disseminate Pasos Adelante as a Latino-appropriate intervention for addressing a ‘Winnable Battle’ [23]. Recently a large independent study of Pasos executed by an academic, primary care, community and local health department partnership (urban and non-border) showed significant clinical improvements through the study’s endpoint—an immediate post-intervention assessment [24].

Adapted from Pasos, the Meta Salud (Health Goal) was developed for Northern Mexico, one key modification was employing site-based exercise groups based on community preference [25]. The 13-week curriculum was implemented and evaluated in a cohort of adults residing within the largest city in the state of Sonora. The majority (57%) of participants was obese at baseline, though most did not have a chronic disease such as diabetes (17%). Participants showed significant improvements at the 3-month follow up in body mass index, waist, cholesterol and glucose. Findings were clinically significant, e.g. through the follow-up LDL cholesterol was 22 md/dl lower and fasting glucose 8 mg/dl lower.

While there are studies evidencing clinical improvements for Pasos (United States) and Meta Salud (Mexico), these interventions may be further strengthened and refined. Two community-based evaluations of adaptations of Su Coraz�n, Su Vida showed desired risk factor reductions were dependent on as age and specific underlying health conditions [9, 26]. Furthermore, a randomized controlled trial in Mexican-origin women in an urban community showed significant improvements in dietary habits and waist circumference, though non-significant effects on physical activity and glucose [27]. Given physical activity is critical to improved insulin response, lowers risk for cardiometabolic syndrome, and has protective effects on mental well-being [28, 29], effectively and broadly reaching physical activity goals is crucial to these interventions having optimal health impact.

One important way to understand if these interventions are as impactful as possible is to assess whether the behavioral targets of the intervention are consistently impacted. The primary objective of this study is to test whether Pasos participants had the expected changes in targeted physical activity and dietary behaviors, and examine the consistency of such findings with behavioral changes evidenced in the Mexico-implemented, Meta Salud, cohort. Prior studies of dietary and activity changes in Pasos have been limited to immediate intervention post-tests (16, 24) and a secondary analyses of a small cross-sectional sample (N = 48) of self-identified Pasos participants [20]. Furthermore, no study has examined the consistency of behavioral changes in Pasos and its sister curriculum Meta Salud in the US and Mexico cohorts. Meta Salud participants have shown some improvements in meeting dietary and physical activity goals; e.g. significant changes were evidenced in seven of 12 behavioral outcomes assessed immediately after program conclusion [30]. We hypothesize that intervention participants’ will have health protective changes in diet and physical activity through the 6 month assessment periods.

A second objective is to test expected changes in subjective health markers in these interventions. Such markers include self-rated health (SRH)—a global indicator of personal sense of overall health and an established indicator of future mortality in clinical and general populations worldwide [31, 32]. Examining for consistent behavioral and subjective health changes among participants of these interrelated interventions across nations will yield insight to the potential generalizability of this CHW-lead health promotion model for Mexican-origin populations. Reporting evidence on the generalizability or external validity of health behavioral interventions of is of high importance to health education program implementation [33]. Furthermore, if some of the behavioral antecedents expected to mediate clinical improvements [34] are not significantly impacted, modification of these curricula should be considered to strengthen their impact.

Materials and methods

Sampling and implementation

The final Pasos Adelante curriculum was implemented within a rural US–Mexico border community in Arizona and evaluated using a quasi-experimental design that included a baseline, program conclusion and 3-month follow-up assessments [16]. Participants were initially recruited by three bilingual promotoras who expressed the availability of a program to reduce the risk for heart disease, diabetes and other chronic diseases in community settings (e.g. health fairs; after school events). Subsequent participants also included persons referred to program from prior participants.

The last of the assessments for Pasos were completed in 2008 and the sample size at baseline was 347. Of these, 83% were assessed at the intervention conclusion and 73% at the follow-up. Health behavior data from this evaluation cohort has not been reported on in part or whole previously. Impact of the intervention on the clinical indicators [16], depression/quality of life [21] and on clinical/behavioral reports within a small (n = 48) self-reported Pasos-exposed cross-sectional sample are previously reported [20].

Implementation and all assessments for the Meta Salud evaluation were completed in 2012 [25]. This evaluation included comparable design and assessments as that previously described for Pasos. Among baseline respondents (N = 171), 152 (83%) completed all three questionnaires. Nine promotoras recruited for Meta Salud in four low-income neighborhoods of the largest city in the border state of Sonora, Mexico. While Meta Salud’s promotoras were employed at community health centers (funded by the State Ministry of Health), study recruitment efforts were focused outside clinical settings, including going to households door-to-door and through school settings.

There were no exclusion criteria for either evaluation, though participants had to be over 18 and residing in the community of each interventions’ sites. Participation was voluntary and participants could withdraw at any time. All objectives, materials and protocols for the Pasos were reviewed and approved by the University of Arizona’s Institutional Review Board. Protocols for Meta Salud were approved by the ethics committee at El Colegio de Sonora. Though curricula and instruments had existing Spanish translations, all materials were reviewed by multiple Spanish first language team members. Materials were also further refined after pilot phases with bilingual personnel embedded in the communities they were delivered.

Intervention descriptions

Pasos and Meta Salud are chronic disease preventive [23] interventions. They are highly similar and include CHW facilitated and group-based weekly educational sessions (typically 2 h) delivered with substantial interactive and team-based learning. The curricula have a heavy focus on improving dietary habits and physical activity, while samples of other sessions include identifying signs of chronic disease onset and management, promoting emotional/mental well-being and empowerment. The latter, from an individual and community perspective, is a topical area promotoras are well situated to address [10]. Pasos had 13 groups completing the intervention (mean group size of participants of 27), Meta Salud had 8 groups (mean of 23). Sessions were held weekly, 84% (Pasos) and 63% (Meta Salud) of participants completed >8 of them.

A unique component for Pasos to promote physical activity and social bonding was the establishment of walking groups, many of which continued through participants’ own initiative after project completion. Meta Salud with minor changes from Pasos guided by Mexican public health guidelines and to address cultural mores expressed from engagement with community engagement. Rather than walking groups, on-site exercise groups (1–3 times per week) were requested and implemented. There were deliberative processes to be attuned to current community, cultural and geopolitical realities, including adaptations to the differing health care systems between nations (e.g. universal health care in Mexico) and promotion of women’s empowerment. Complete curricula and supporting resources (training manuals and evaluation tools) are freely accessible [23, 35, 36].

CHWs were recruited and trained by bilingual University-employed team members for both interventions, with quarterly training activities to promote fidelity [16, 25]. Such efforts are likely to also the promotoras’ skill acquisition and maintenance [10] as well as provide them necessary instrumental support. Additional details following TREND [37] guidelines on design, recruitment strategies, implementation and diagrammatic flows of participants are available [16, 25].

Measures and variable coding

The self-report assessments included broad health content (e.g. demographic, health-related behaviors, health status, access to care and subjective health) and were most often adapted from standard national and international health behavior surveillance tools [38, 39]. Questions corresponding to more specific behavioral change objectives of sessions (e.g. reducing whole milk consumption and unhealthy fats in cooking) were also added. The Spanish-language questionnaire developed for Pasos was used in Meta Salud, although select items were altered to the local vernacular of Northern Mexico. Anthropometric and laboratory evaluation data were collected and reported in prior studies [16, 24].

In operationalizing the outcomes, common public health surveillance benchmarks were used when available [38]. Daily fruit servings combining fruit and (up to a single serving of) fruit juice intake were averaged over the past week. Milk type was dichotomized into whether they usually drank whole milk or not, sugary drinks included soda as well as non-carbonated sugary drinks in the past week. Health preferable oil reflected using olive oil or canola oil versus another type most of the times in household cooking (e.g. lard, butter). Minutes of weekly walking was calculated as daily minutes of walking X walking days/week. Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) per week = 3.3 X daily minutes of walking X days/week + 4 X daily minutes of moderate exercise X number of days/week + 8 X daily minutes of vigorous exercise X the number of days/week. Meeting the CDC’s recommended exercise per day was coded into whether an individual engaged in ≥75 vigorous or ≥150 moderate minutes of exercise per week. Self-rated health was coded following the common standard [30, 31] of whether the participant responded excellent, very good or good versus fair or poor health.

Statistical analysis

Linear mixed models were used to estimate the differences between baseline, conclusion and follow-up for all continuous outcomes, adjusting for age and using subject as a random effect to account for intra-individual correlation. Generalized linear logistic mixed models were used for binary outcomes, with odds ratios computed to compare post-intervention values to baseline values. All 347 Pasos and 171 Meta Salud participants who completed a baseline questionnaire were entered in these mixed model analyses, which efficiently use available data and are robust to the presence of missing data [40]. Time was used as a categorical variable to reduce likelihood of model misspecification. Graphs of both interventions included odds ratios for binary outcomes and the standardized mean difference for continuous outcomes to facilitate the comparing of relative magnitude of effects.

Sensitivity analyses were performed by testing the logarithm of non-normal continuous outcomes (+1) and in models without outliers for METs (i.e. ≥20 000). Exploratory analyses were carried out to characterize the participants who made behavioral changes in terms of demographics and risk factors. These potential factors included being employed, age, body mass index (BMI), having diabetes, having a family member with diabetes or excess CVD risk (defined as having CVD, high cholesterol or high blood pressure). First, we used mixed models for each of the outcomes which included fixed effect terms for age, time, the factor of interest, and their interaction, as well as a random effect for participant. A significant interaction would indicate that the factor is associated with change over time in the outcome. The second approach was to use logistic regression to model the likelihood of making a health desirable change of 10% or more for continuous outcomes and from 0 to 1 for binary outcomes at the 3-month follow-up as a function of demographic and risk factors.

Results

Baseline demographic and clinical indicators of risk are reported in Table I. Notable differences between the Pasos Adelante and Meta Salud intervention cohorts are that Meta Salud participants were younger, smoked more, had lower cholesterol, were more likely to be married, and almost all had insurance coverage (98% versus 55%).

Table I.

Baseline demographic and health status characteristics of Pasos Adelante (United States) participants (N = 347) and Meta Salud (Mexico) participants (N = 171)

| Pasos Adelante n (%) | Meta Salud n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 314 (90) | 168 (97) |

| Married | 229 (66) | 147 (85) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 203 (58) | 153 (90) |

| Completed high school | 82 (24) | 11 (06) |

| Post high school | 62 (18) | 7 (04) |

| Currently employed | 115 (33) | 62 (36) |

| Has health insurance | 190 (55) | 167 (98) |

| Length of residence in current community | ||

| Less than or equal to 10 | 141 (41) | 22 (13) |

| Greater than 10 | 206 (59) | 149 (87) |

| Born in Mexico (born in Sonora for Meta Salud) | 307 (88) | 126 (74) |

| Family members w/diabetes | 220 (64) | 105 (61) |

| Diagnosed w/diabetes | 91 (22) | 29 (17) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Less than 25 | 48 (14) | 23 (13) |

| 25–29.9 | 113 (33) | 51 (30) |

| 30–39.9 | 155 (45) | 80 (47) |

| Greater than 40 | 31 (9) | 17 (10) |

| Heart disease | 31 (9) | 12 (7) |

| High blood pressure | 143 (41) | 52 (30) |

| High cholesterol | 146 (42) | 38 (22) |

| Asthma | 26 (7) | 12 (7) |

| Current smoker | 23 (7) | 27 (16) |

| Age (mean/SD) | 51.6 � 14.1 | 41.5 � 10.6 |

Data are reported as mean � standard deviation for age. BMI, body mass index.

The proportions and means in outcomes at each assessment period and significance tests in the larger cohort (Pasos) are presented in full in Table II. Omnibus tests indicated statistically significant changes (P < 0.05) across all outcomes except sitting, walking, METs and days unable to perform regular activities due to poor health. There were increases from baseline to conclusion in proportion of participants: meeting CDC recommendations for exercise per day (OR = 1.8); use of olive or canola oil for cooking (OR = 2.2) and, good self-rated health (SRH; OR = 1.8). There were decreases in participants drinking whole milk (OR = 0.37). The linear models showed significant changes to conclusion in daily fruit servings (0.25); sugary drinks per day (−0.15); days of poor physical health per month (−1.5) and poor mental health days per month (−2.1). There were also significant changes from baseline to follow-up in proportion of participants’ meeting CDC recommendations for exercise per day (OR = 1.5); use of olive or canola oil for cooking (OR = 1.5); reporting good SRH (OR = 1.8) and, drinking whole milk (OR = 0.41). At follow-up there were also significant increases in daily vegetable (0.11) and fruit servings (0.18); and significant decreases in poor mental health days per month (−2.4).

Table II.

Mean (standard deviation) or percentage of outcomes at baseline, intervention conclusion, 3-month follow-up for Pasos Adelante participants

| Outcome | Mean (SD) or percentage | Change or odds ratio (95% CI) | Overall P-valuea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, N = 347 | Conclusion, N = 287 | 3-Month follow-up, N = 255 | Conclusion— baseline | P-value | Follow-up— baseline | P-value | ||

| Physical activity | ||||||||

| Sitting (min/day) | 173.7 (264.9) | 151.1 (191.5) | 152.8 (156.2) | −22.6 (−53.1, 7.9) | 0.1 | −20.9 (−52.5, 10.7) | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Walking (min/week) | 280.1 (997.1) | 285.2 (442.1) | 231.1 (721.4) | 5.2 (−111.8, 122.1) | 0.9 | −48.9 (−170.2, 72.4) | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| METs/week | 3712 (6961) | 4199 (5170) | 3815 (5972) | 487 (−374, 1349) | 0.3 | 103 (−794, 1000) | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| CDC recommended exercise (%) | 51 | 64 | 61 | 1.8 (1.3, 2.5) | 0.001 | 1.5 (1.1, 2.1) | 0.02 | 0.002 |

| Nutrition | ||||||||

| Whole milk (%) | 16 | 7 | 8 | 0.37 (0.21, 0.66) | 0.0009 | 0.41 (0.22, 0.74) | 0.003 | 0.0006 |

| Surgary drinks/day | 0.73 (1.05) | 0.57 (0.80) | 0.63 (0.97) | −0.15 (−0.27, −0.04) | 0.007 | −0.10 (−0.21, 0.02) | 0.1 | 0.02 |

| Olive or canola oil for cooking (%) | 49 | 66 | 59 | 2.2 (1.5, 3.1) | <0.0001 | 1.5 (1.0, 2.2) | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Vegetable servings/day | 0.79 (0.70) | 0.87 (0.60) | 0.90 (0.58) | 0.08 (−0.003, 0.16) | 0.06 | 0.11 (0.03, 0.19) | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Fruit servings/day | 1.44 (1.11) | 1.69 (1.14) | 1.62 (1.10) | 0.25 (0.12, 0.38) | 0.0002 | 0.18 (0.04, 0.31) | 0.01 | 0.0007 |

| General health | ||||||||

| Poor physical health days/month | 6.8 (9.8) | 5.3 (8.4) | 5.6 (8.7) | −1.5 (−2.7, −0.3) | 0.01 | −1.2 (−2.4, 0.06) | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Poor mental health days/month | 7.0 (9.8) | 5.0 (8.0) | 4.7 (8.0) | −2.1 (−3.1, −1.0) | 0.0002 | −2.4 (−3.5, −1.2) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Good health (%) | 58 | 69 | 65 | 1.8 (1.3, 2.7) | 0.002 | 1.5 (1.0, 2.2) | 0.04 | 0.006 |

| # Days unable to perform regular activities due to poor health | 2.7 (5.6) | 2.6 (5.6) | 2.7 (6.1) | −0.2 (−1.0, 0.6) | 0.7 | −0.02 (−0.9, 0.8) | 1.0 | 0.9 |

Change or odds ratio from conclusion or follow-up to baseline as estimated from linear mixed models (for continuous outcomes) or logistic mixed models (for binary outcomes) adjusting for age, where follow-up time was used as a fixed-effect categorical variable and participant was used as a random effect. CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; MET, metabolic equivalent of task.

Overall F-test for time variable across the three assessments.

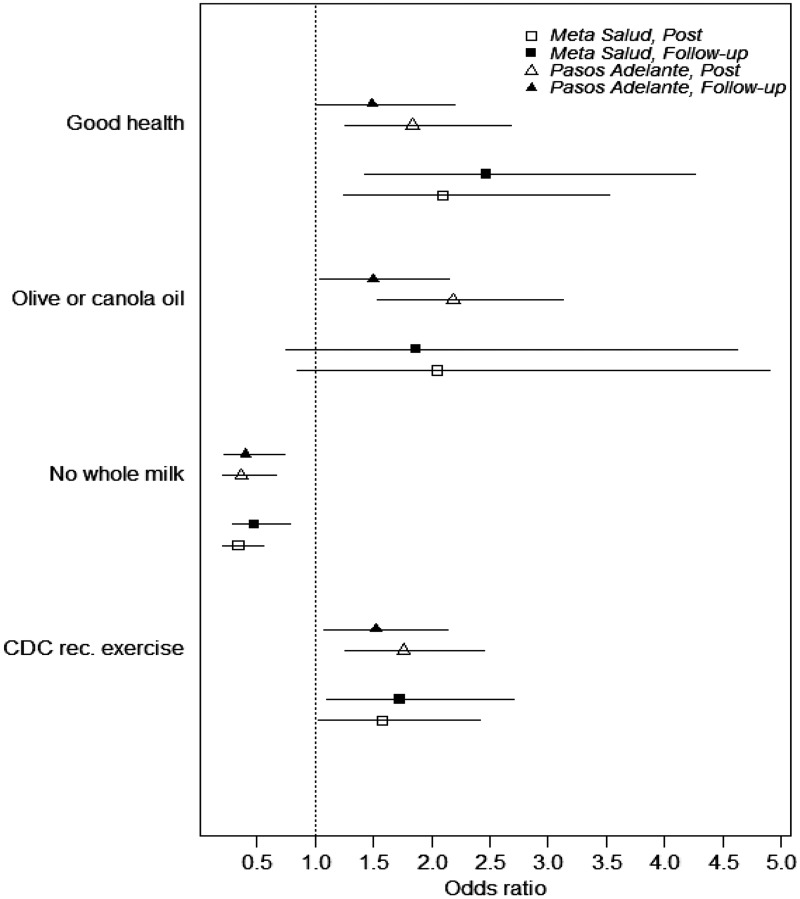

Comparative estimates of Pasos Adelante to Meta Salud

The estimates for Pasos participants presented in Table II were contrasted to those from equivalent models with the Meta Salud cohort, with standardization to facilitate comparisons. Figure 1 shows the odds ratios and confidence intervals for binary outcomes for each intervention. SRH was higher at all intervention conclusion and follow-up assessments (statistically significant ORs = 1.5–2.5). Also consistent across significance tests for all estimates are lower whole milk consumption (ORs = 0.4–0.5) and higher likelihood for meeting CDC guidelines for physical activity (ORs = 1.5–1.8). Consuming healthier oil showed positive trends (though not significant in Meta Salud).

Fig. 1.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each binary outcome from baseline, post intervention and 6 months after baseline assessment in the Pasos Adelante and Meta Salud cohorts.

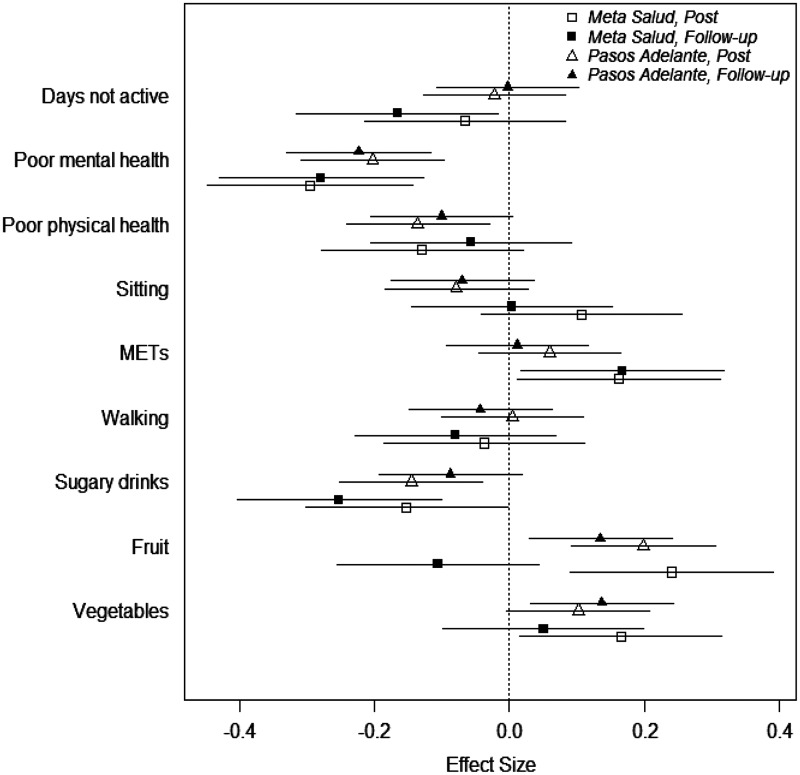

Figure 2 illustrates standardized effects sizes with confidence intervals for the interventions’ continuous outcomes. Statistically significant and fewer days of poor mental health are evident in both cohorts in all post intervention assessments (≥2 fewer days of poor mental health after the interventions and through the follow-ups). Significant increases in consuming vegetables and consuming fruits, and decreases in consuming sugary drinks, are observed in three of the four post intervention assessments. Meta Salud had significant improvements in both post-intervention assessments for METs and fewer days not active at follow-up. Estimates of changes in walking or sitting were not significant in the interventions. Poor physical health has positive trends in both interventions, though significant only in Pasos immediate post-test.

Fig. 2.

Standardized effect size and 95% confidence intervals for each quantitative outcome from baseline, post intervention and 6 months after baseline assessment in the Pasos Adelante and Meta Salud cohorts.

Sensitivity analysis

These ancillary analyses were consistent with the primary analyses, with a few exceptions. For Pasos the nominal level of P-values changed from insignificant to significant at conclusion and follow-up for METs and minutes of weekly walking (both P < 0.01), and for daily vegetable servings at conclusion (P = 0.004). These significant findings were all in the health positive and theorized direction. When 24 observations with excessive METs/week (≥20 000) were excluded and original scale were used for regression, the increase in METs/week at conclusion became significant (P = 0.001). These analyses with Meta Salud also confirmed primary analysis and showed robust estimates. However fruit consumption was significant at follow-up (P = 0.04) unlike the primary analysis, and METs significance varied by the method of ancillary analysis applied. Other primary analyses of Meta Salud that yielded Ps ≤ 0.05 were similar or smaller values in subsequent sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

Behavioral and subjective health improvements through the 6 months of assessments were evident for Pasos Adelante and Meta Salud participants. Significant and consistent improvement in meeting CDC guidelines for exercise across post-intervention assessments intervals and across nations. From baseline to follow-up (6-months) in Pasos and Meta Salud participants were estimated to be 10% and 14% more likely to meet these guidelines. Regarding dietary changes, the most robust improvements across the cohorts were consuming less sugary drinks and less whole milk. The reduction of sugary drinks may be a particularly important finding as their consumption is strongly linked to metabolic abnormalities; in fact their reduction is a major focus of obesity control efforts in Mexico [41]. Odds of consuming whole milk dropped by more than half in the cohorts, with changes maintained through follow-up. Also, at all post intervention assessments there was ≥2 fewer days of poor mental health and ≥10% improvement in self-rated health–strong markers the interventions positively impacted well-being.

There were also less consistent and non-significant findings. Most models did not evidence changes in sitting, days not active or walking (in sensitivity analyses walking was significant higher at follow-up for Pasos participants). It is possible for individuals with high levels of sedentary behavior, stronger or different types of intervention modules are needed. For both interventions additional or modified sessions directed to these behaviors should be considered. The findings may also be affected by context-based facilitators and barriers that vary by locale, but not reflected within the current sampling where the participants were relatively homogenous and from single communities. Likewise in Meta Salud there may be barriers to sustaining increases in fruits and vegetables at the community level, as Pasos had stronger evidence for these dietary lifestyle improvements. It is possible more limited fresh produce availability or higher relative cost in Sonora may require other structural-level interventions to reinforce the curricular objectives.

On balance the changes in physical activity and diet support the study’s hypothesis. The findings from the Pasos cohort add to the evidence for using these interventions to prevent chronic disease in under-served populations within high-income nations [14, 26]. Studies with non-border Latinos have also increased the evidence base for CHW interventions being effective in reducing risk for chronic disease in the United States [23, 42, 43]. Likewise, the present findings on Meta Salud compliment other promising evaluations of chronic disease risk reduction in Southern Mexico and Costa Rica from a CHW intervention [44]. Together they suggest a promising and scalable preventive strategies to reduce escalating burden of chronic diseases in middle-income Latin American regions.

The study’s major limitation is the lack of comparison groups—either via random assignment or non-random with comparators. Self-selection into the interventions could impact the findings. However when compared to propensity score matched controls from the same community, a subset of reported Pasos participants had statistically significant reductions in fatty milk consumption and increased meeting of CDC recommended exercise guidelines [20]. These estimates of intervention effects reflect an average of 4.5 years after the Pasos intervention and the effect sizes are similar to the within-person changes estimated from this study. Another limitation is the potential impact of social desirability. However due to the within-person modeling executed, social desirability would be adjusted for except to the degree it changed over time. Furthermore, it should be noted the current findings are consistent with cohort improvements in objective measures [16, 25] and with the understanding that self-rated health is a consistent predictor of objective health outcomes [31, 32].

While the limitations are important, they are tempered in that the two independent, binational, cohorts showed similar changes in diet and physical activity. Furthermore, related CHW interventions have shown some positive clinical effects when evaluated via randomized designs [9, 27]. Of note, despite the high health risks for residents, US–Mexico border region research studies are particularly challenging given economic, medical and geopolitical obstacles [2, 5, 9, 20, 45].

The imbalance in sex of participants is also noted. A contributing factor to the overwhelming enrollment of women may be their traditionally higher involvement in community affairs and social participation in Mexico. The intervention may have been more effective due to this imbalance, given the historical roots of the promotora movement with indigenous women [45]. It is possible through reaching more women the CHWs may have broader impact on their families and peer networks that likely for participating men—essentially the women completing the intervention may act as an extension of the promotora [10]. The low rates of engaging men in the present and other related studies [8, 9, 22] does suggests a continued public health challenge. In fact for males >50 in Mexico diabetes is the principal cause for their decreased life expectancy projections [46, 47]. One CHW study conducted within a tight community within Mexico City, and with a strong community partner with a particularly diverse and broad community outreach, was able to report on comparable participation of men [26]. This balance was achieved despite this intervention having 19 women of 22 CHWs. There may be lessons learned that could be applied to recruit more Latino participants in CHW programs, though whether that study’s recruitment strategies would be as effective in other communities and contexts is unknown.

There are a number of critical next steps in research on Pasos Adelante and Meta Salud. There is a need for random controlled trials to provide the strongest evidence for clinical and behavioral effects. One challenge to conducting this research is requesting that CHWs not deliver, or postpone, interventions to persons in need presents an ethical obstacle for these health professionals. A key component to these interventions success may be CHWs’ desire, more aptly described a fundamental core sense of purpose, to help all members of their community [10, 45]. Relatedly, such a design may have a major problem of contamination, as such interventions may involve community resources to promote exercise or healthy eating, or common centers where most persons receive health care. Other alternatives include highly expensive and practically challenging cluster randomized trials (e.g. randomization at the community/health center level); where causal inference and statistical power is limited without numerous group level units [48].

Future research may also seek to scale Pasos Adelante and Meta Salud to positively shift population level trends in chronic disease in Latino populations. Such research could also afford an exploration of community-level factors that may interact with the curricula in determining chronic disease risk reduction. However such research will also bring its own unique obstacles. Within Mexico an intervention like Meta Salud may not be as effective when scaled to national/regional levels if the selection of the intervention delivery personnel are more influenced from centralized health system administrators than local stakeholders [45]. The latter may better identify trusted and connected local residents.

Conclusion

CHW driven preventive interventions such as Pasos Adelante and Meta Salud are increasingly promising for reducing chronic disease risk in Mexican-origin persons. The evidence base supports continued dissemination efforts. Encouraging findings from this study are the cross-national evidence for increasing physical activity, such as meeting CDC benchmarks, and multiple improved dietary behaviors targeted. However adopters of the interventions should be aware of some mixed findings, and without enhancements the curricula may not be effective in changing sedentary behavior. The success of CHW intervention components such as walking groups [16], clinic-housed group based classes [22], connection to external community exercise resources [9] or by tailoring to all such modalities to individual participants or local contexts [49], may be crucial to reduced chronic disease risk. A common component to these efforts should be social bonding among participants and with CHWs—strengthened through interactive and collective action activities [10]—to reinforce healthy lifestyle change and reduce co-morbidities such as depression [50]. However even with effective engagement of individuals and their peer networks, these CHW intervention may require structural supports to reduce chronic disease morbidity and mortality [29, 49]. Examples such as investment in more parks and walking areas, supporting access to affordable healthy foods and beverages, and in Mexico, implementing systems that ensure potable water in all schools, workplaces and homes, may be further necessities for optimally foster healthy lifestyles.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the promotoras and participants, the Douglas Special Action Group for its support of Pasos Adelante, and Tanyha Zepeda and other members of the Arizona Prevention Research Center (AzPRC) and research staff at El Colegio de Sonora for their diligence in ensuring high-quality data collection and entry for Pasos Adelante and Meta Salud. We also acknowledge Maria Lourdes Fernandez and Carol Huddleston (deceased) for their unwavering leadership in promoting health in the Douglas community and intersections with the Pasos Adelante. We also acknowledge the Secretar�a de Salud del Estado de Sonora [Sonora State Health Ministry] for supporting community health worker recruitment and overall intervention logistics for Meta Salud.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States Department of Health and Human Services (U48DP005002 to S.C.C, U48-DP000041 to L.K.S.); UnitedHealth Chronic Disease Initiative (to C.D.) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (R01HL125996 to C.R.).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1. Barquera S, Pedroza-Tob�as A, Medina C. et al. Global overview of the epidemiology of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Arch Med Res 2015; 46: 328–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elder JP, Arredondo EM.. Strategies to reduce obesity in the U.S. and Latin America: lessons that cross international borders. Am J Prev Med 2013; 44: 526–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oyebode O, Pape UJ, Laverty AA. et al. Rural, urban and migrant differences in non-communicable disease risk-factors in middle income countries: a cross-sectional study of WHO-SAGE data. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0122747.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reininger BM, Wang J, Fisher-Hoch SP. et al. Non-communicable diseases and preventive health behaviors: a comparison of Hispanics nationally and those living along the US–Mexico border. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang X, Ghaddar S, Brown C. et al. Alliance for a healthy border: factors related to weight reduction and glycemic success. Popul Health Manag 2012; 15: 90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; pii: S0140-6736(15)00128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramirez A. The dire need for cancer health disparities research. Health Educ Res 2013; 28: 745–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ayala G, Vaz L, Earp J. et al. Outcome effectiveness of the lay health advisor model among Latinos in the United States: an examination by role. Health Educ Res 2010; 25: 815–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Heer HD, Balcazar HG, Wise S. et al. Improved cardiovascular risk among hispanic border participants of the Mi Coraz�n Mi Comunidad Promotores De Salud Model: the HEART II Cohort Intervention Study 2009–2013. Front Public Health 2015; 3: 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koskan AM, Friedman DB, Brandt HM. et al. Preparing promotoras to deliver health programs for Hispanic communities: training processes and curricula. Health Promot Pract 2013; 14: 390–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neupane D, McLachlan CS, Mishra SR. et al. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention led by female community health volunteers versus usual care in blood pressure reduction (COBIN): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6: e66–e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Balcazar H, George S.. Community health workers: bringing a new era of systems change to stimulate investments in health care for vulnerable US populations. Am J Public Health 2018; 108: 720–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Islam N, Nadkarni SK, Zahn D. et al. Integrating community health workers within Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. J Public Health Manag Pract 2015; 21: 42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM.. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health 2014; 35: 399–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson KJ, Brown HS, Bastida E.. Cost-effectiveness of a community-based weight control intervention targeting a low-socioeconomic-status Mexican-origin population. Health Promot Pract 2015; 16: 101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Staten LK, Cutshaw CA, Davidson C. et al. Effectiveness of the Pasos Adelante chronic disease prevention and control program in a US–Mexico border community, 2005–2008. Prev Chronic Dis 2012; 9: E08. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav 2004; 31: 143–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Su Coraz�n, Su Vida. Bethesda, MD: NIH Publication; No. 00-4087, 2000. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/resources/heart/hispanic-health-manual. Accessed: 14 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Staten LK, Scheu LL, Bronson D. et al. Pasos Adelante: the effectiveness of a community-based chronic disease prevention program. Prev Chronic Dis 2005; 2: A18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carvajal SC, Miesfeld N, Chang J. et al. Evidence for long-term impact of Pasos Adelante: using a community-wide survey to evaluate chronic disease risk modification in prior program participants. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013; 10: 4701–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cutshaw CA, Staten LK, Reinschmidt KM. et al. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life among participants in the Pasos Adelante chronic disease prevention and control program, Arizona, 2005–2008. Prev Chronic Dis 2012; 9: E24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Balc�zar HG, de Heer H, Rosenthal L. et al. A promotores de salud intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in a high-risk Hispanic border population, 2005–2008. Prev Chronic Dis 2010; 7: A28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notable Accomplishments in Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity: Community-Based Program on the U.S.–Mexico Border Reduces Chronic Disease Risks, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Population Health Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/prc/prevention-strategies/chronic-disease-risks.htm. Accessed: 14 July 2018.

- 24. Krantz MJ, Beaty BM, Coronel-Mockler S. et al. Reduction in cardiovascular risk among Latino participants in a community-based intervention linked with clinical care. Am J Prev Med 2017; 53: e71–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Denman CA, Rosales C, Cornejo E. et al. Evaluation of the community-based chronic disease prevention program Meta Salud in Northern Mexico, 2011–2012. Prev Chronic Dis 2014; 11: E154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Balc�zar H, Fern�ndez-Gaxiola AC, P�rez-Lizaur AB. et al. Improving heart healthy lifestyles among participants in a Salud para su Coraz�n promotores model: the Mexican pilot study, 2009–2012. Prev Chronic Dis 2015; 12: E34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koniak-Griffin D, Brecht ML, Takayanagi S. et al. A community health worker-led lifestyle behavior intervention for Latina (Hispanic) women: feasibility and outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2015; 52: 75–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bouchonville M, Armamento-Villareal R, Shah K. et al. Weight loss, exercise or both and cardiometabolic risk factors in obese older adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014; 38: 423–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gallegos-Carrillo K, Flores YN, Denova-Guti�rrez E. et al. Physical activity and reduced risk of depression: results of a longitudinal study of Mexican adults. Health Psychol 2013; 32: 609–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Denman CA, Bell ML, Cornejo E. et al. Changes in health behaviors and self-rated health of participants in Meta Salud: a primary prevention intervention of NCD in Mexico. Glob Heart 2015; 10: 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Flores YN, Shaibi GQ, Morales LS. et al. Perceived health status and cardiometabolic risk among a sample of youth in Mexico. Qual Life Res 2015; 24: 1887–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. P�rez-Zepeda MU, Belanger E, Zunzunegui MV. et al. Assessing the validity of self-rated health with the short physical performance battery: a cross-sectional analysis of the international mobility in aging study. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0153855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McLeroy KR, Garney W, Mayo-Wilson E. et al. Scientific reporting: raising the standards. Health Educ Behav 2016; 43: 501–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Horton LA, Ayala GX, Slymen DJ. et al. A mediation analysis of mothers' dietary intake: the entre familia: Reflejos de Salud randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Behav 2018vol. 45: 501–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arizona Prevention Research Center. Pasos Adelante Curriculum, 2017. Available at: https://azprc.arizona.edu/curricula/steps-forward-curriculum-english-version. Accessed 14 July 2018.

- 36. El Colegio de Sonora. Meta Salud, 2017. Available at: http://sitios.colson.edu.mx/metasalud/. Accessed: 14 July 2018.

- 37. Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N. et al. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health 2004; 94: 361–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html. Accessed 14 July 2018.

- 39. Ministerio de Salud P�blica. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutricion (ENSANUT), 2017. Available at: http://www.salud.gob.ec/encuesta-nacional-de-salud-y-nutricion-ensanut/. Accessed: 14 July 2018.

- 40. Bell ML, Fairclough DL.. Practical and statistical issues in missing data for longitudinal patient-reported outcomes. Stat Methods Med Res 2014; 23: 440–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Meneses-Leon J, Denova-Guti�rrez E, Casta��n-Robles S. et al. Sweetened beverage consumption and the risk of hyperuricemia in Mexican adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014; 14: 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rothschild SK, Martin MA, Swider SM. et al. Mexican American trial of community health workers: a randomized controlled trial of a community health worker intervention for Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Public Health 2014; 104: 1540–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mudd-Martin G, Martinez MC, Rayens MK. et al. Sociocultural tailoring of a healthy lifestyle intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes risk among Latinos. Prev Chronic Dis 2013; 10: E200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fort MP, Murillo S, L�pez E. et al. Impact evaluation of a healthy lifestyle intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in health centers in San Jos�, Costa Rica and Chiapas, Mexico. BMC Health Serv Res 2015; 15: 577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Balcazar H, Perez-Lizaur AB, Izeta EE. et al. Community Health Workers-Promotores de Salud in Mexico: history and potential for building effective community actions. J Ambul Care Manag 2016; 39: 12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Canudas-Romo V, Garc�a-Guerrero VM, Echarri-C�novas CJ.. The stagnation of the Mexican male life expectancy in the first decade of the 21st century: the impact of homicides and diabetes mellitus. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015; 69: 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Palloni A, Beltr�n-S�nchez H, Novak B. et al. Adult obesity, disease and longevity in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 2015; 57(Suppl. 1): S22–S30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Huang S, Fiero MH, Bell ML.. Generalized estimating equations in cluster randomized trials with a small number of clusters: review of practice and simulation study. Clin Trials 2016; 13: 445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ayala GX, San Diego Prevention Research Center Team. Effects of a promotor-based intervention to promote physical activity: familias Sanas y Activas. Am J Public Health 2011; 101: 2261–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hernandez R, Ruggiero L, Prohaska TR. et al. A cross-sectional study of depressive symptoms and diabetes self-care in African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos with diabetes: the role of self-efficacy. Diabetes Educ 2016; 42: 452–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]