Coronary artery disease (CAD), including stable angina and acute coronary syndrome (ACS), is a leading cause of death and hospitalization in Canada.1 About 2.4 million adult Canadians live with CAD, and in 2013, it was estimated that of every 100,000 Canadians, 205 were hospitalized for an acute myocardial infarction.2 Treatment options for CAD include lifestyle changes, medications, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and cardiac rehabilitation.3

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)—acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) in combination with a P2Y12 inhibitor such as clopidogrel, ticagrelor or prasugrel—is a cornerstone of medical therapy for patients undergoing revascularization via PCI, both electively and emergently, to reduce the risk of stent thrombosis.4 The use of DAPT reduces angina, recurrent myocardial infarction and death, regardless of revascularization.4 The 2018 Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS)/Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology (CAIC) Focused Update of the Guidelines for the Use of Antiplatelet Therapy provides recommendations for the duration of DAPT in patients undergoing PCI for ACS and non-ACS indications, balancing individual bleeding and thrombosis risk, which are dependent on both patient- and procedure-related factors. Recommendations for PCI for ACS indications include standard DAPT duration (12 months) and extended (up to 3 years) and for non-ACS indications include shortened (1-3 months), standard (6-12 months) and extended (up to 3 years) DAPT.5 It is critical for patients to fill prescriptions on a timely basis after discharge from hospital after a coronary event or PCI and to understand their planned treatment duration to avoid interruption in therapy.6 The risks associated with early discontinuation of DAPT are significant. Both primary nonadherence (not filling the initial prescription) and secondary nonadherence (early interruption of therapy) increase the risk of stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, hospitalization and even death.6,7 Patients who discontinue P2Y12 inhibitors within 1 month of PCI with a drug-eluting stent (DES) are 1.5 times more likely to be hospitalized, typically due to myocardial infarction, and have 9 times higher mortality rate within 1 year.8 Acute stent thrombosis related to premature cessation of DAPT therapy is a serious complication.

Despite evidence showing the benefits of adherence and the risks of nonadherence to these medications, adherence rates are suboptimal. Data regarding primary nonadherence suggest that up to 23% of cardiac medication prescriptions are not filled within the first week following discharge, and even at 120 days following discharge, 18% are not filled.6 Secondary nonadherence is significant; the literature indicates that premature discontinuation of DAPT within the first 3 months occurs in approximately 13% of patients and up to 20% of patients after 6 months post-PCI, with suboptimal adherence by 12 months.6,7,9 Barriers to nonadherence are multifactorial, influenced by prescribers, patients and the health care system.10 One study noted that typical reasons cited by patients for not taking their medications included forgetfulness, other priorities, decision to omit doses, lack of information and emotional factors.10 Health care systems create barriers to adherence by limiting access to health care, establishing formulary restrictions and imposing unmanageable costs on patients.10 It is critical to emphasize the benefit of DAPT and adherence to therapy for the management of CAD and post-PCI, including providing simple, clear and consistent education for patients, families and care providers.10

Providing patients an opportunity to better understand both the benefits of their medication therapy and ways to manage potential expected side effects of medication can empower them to take responsibility for their medications and health. Studies show that the majority of patients have positive attitudes toward Internet-based delivery of health information, which may be a powerful tool for improving decision-making around health care.11-13 Scherrer et al. found that in a group of patients waiting for cardiac surgery, Internet-based information and education increased social support, decreased anxiety, improved lifestyle and facilitated positive attitudes toward the impending surgery compared with other traditional methods of medical education.12 The Internet is a widely available resource for patients. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission reports that 59.7% of Canadians have Internet access at home and Statistics Canada reports that 60% of Canadians have Internet-enabled mobile devices.14,15 Research demonstrates that among patients with low health literacy, a clinical teaching tool using animation and spoken dialogue improved recall and positive attitudes compared with animation or written text alone.16 The literature indicates that patient education after ACS with a focus on atherothrombosis and its different clinical features, and the role of antiplatelet agents and the importance of their use, improves patient adherence to DAPT at 6 months compared with no education.17 Therefore, an Internet-based educational video may improve the delivery and reception of medication education and, more specifically, DAPT education.

We developed a DAPT patient education whiteboard video to address a practical clinical need. Within the Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region acute care hospitals, the provision of education on DAPT at the time this video was developed was heterogeneous, including written and verbal communication. Pharmacists caring for patients with acute cardiovascular events identified the opportunity to enhance the efficiency and consistency of patient education relating to the use of DAPT. Their desire was to provide health care providers in all practice settings with a reliable, consistent and accessible DAPT patient education tool. A whiteboard video to educate patients is a popular, technologically savvy method to deliver information to patients in a multitude of practice areas.18 After determining that such a video did not exist, the decision was made to develop a whiteboard video to provide patient-friendly information via animation and spoken dialogue. A national steering committee of key opinion leaders in cardiovascular pharmacotherapy was developed and an animation vendor was contacted to determine the feasibility and cost of whiteboard development. Funding was sought and provided by Astra Zeneca as an unrestricted grant with no additional input into the project. A script draft from the original group of pharmacists that included key educational points regarding DAPT use was reviewed and modified by a national steering committee. To ensure relevance of the messages, 3 patients who had cardiovascular disease and received DAPT and 2 interventional cardiologists were consulted and provided feedback on the script. After several iterations the finalized script was sent to the vendor, along with suggestions for animation. Upon review of the initial draft of the whiteboard, additional revisions to the script and refinement of the animations were made until a final version was agreed upon.

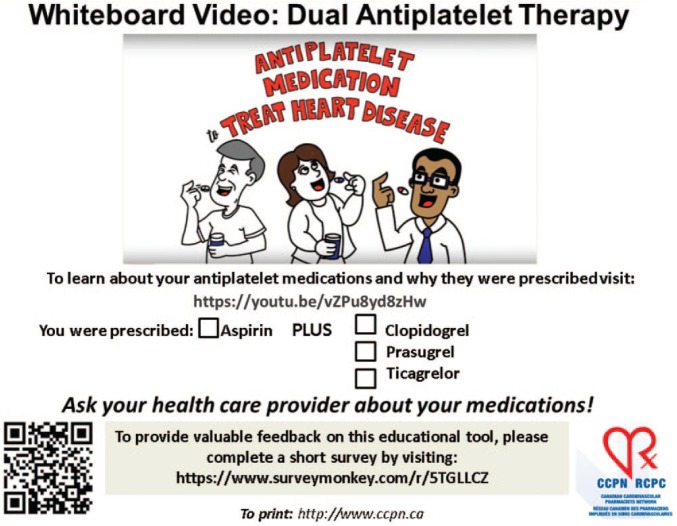

The whiteboard video delivers concise and reliable education in patient-friendly language with visuals about coronary atherosclerosis, the role of DAPT and an overview of the benefits and risks of DAPT medications. This online video addresses a gap in patient-friendly DAPT educational videos with a means to streamline and standardize education. The video is available at the link and QR code given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Printable handout for patients and providers

With the on-demand availability of this video, patients can view the video throughout their cardiac journey at home, at the hospital, while waiting for appointments, or essentially anywhere they have access to the Internet. In addition, the video is available for download from YouTube and can be loaded onto local devices in areas such as inpatient units, cardiac catheterization laboratory recovery rooms and cardiac rehabilitation programs, so it can be used during education sessions provided in these various locations.

Pharmacists play a key role in educating patients and affecting medication adherence. Given their presence throughout the health care system, pharmacists are well positioned to incorporate use of this video into their daily practice at multiple points of a patient’s health care journey.19 Pharmacists interact with patients and their families in hospital, immediately after discharge and during each refill throughout the course of therapy. As the first health care providers with whom patients interact after hospital discharge, community pharmacists reinforce medication education, including benefits, risks and the importance of adherence. Community pharmacists could use and disseminate this video in a variety of ways, which may include advising patients and their families to view the video via mobile devices while waiting for prescriptions throughout the duration that DAPT is prescribed, informing patients how to access the video from home (e.g., via prescription bag stuffers, business cards for patient self-selection, a poster or display in the pharmacy) or showcasing the video as part of a community health day. A printable handout that can be accessed at http://ccpn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/DAPT-handout-link-revised-Aug-10-2018.pdf has been created to facilitate the above-mentioned actions (Figure 1).

This patient care video has been formally endorsed by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology, Prairie Cardiac Foundation and Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute, demonstrating its value and need in clinical practice. Dissemination plans targeting physicians, nurses, patients, caregivers and pharmacists are underway to increase the awareness and use of this video. The video was strategically launched at the Canadian Cardiovascular Congress in October 2017 using a number of vectors. Using social media it was simultaneous posted on YouTube (593 views to date), Facebook (2.4K views to date and 5.9k individuals reached) and Twitter. Key opinion leaders, including pharmacists, physicians and nurses, were engaged to further disseminate the video through social media. There is the potential to “brand” this video, if required, in order for it to be adopted for local or institutional use.

Our aim is to have this video widely accessible to assist stakeholders in the provision of reliable, evidence-based and standard educational information regarding DAPT. Patients are often overloaded with information while in hospital and immediately after discharge. A video that can be conveniently accessed and that reinforces key education points delivered in hospital and community pharmacies may prevent and address potential barriers to medication adherence. The educational video empowers patients with the information required to optimize their health care and improve their health outcomes in relation to their coronary artery disease.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:L. Albers and W. Semchuk initiated the project. S. Tri was responsible for the writing the article under the guidance and review of L. Albers and W. Semchuk as a requirement for completion of a pharmacy residency with the Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region. L. Albers, S. Koshman, C. Bucci, H. Kertland and W. Semchuk reviewed and contributed to the writing of the drafts. The design, writing and conclusions of the article are those of the authors and are independent of a funding source.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:Ms. Tri has nothing to disclose. Ms. Albers reports grants from Astra Zeneca, during the conduct of the tool development; personal fees from Astra Zeneca, outside the submitted work. Dr. Koshman has nothing to disclose. Dr. Bucci reports personal fees from Astra Zeneca, outside of the submitted work. Dr. Kertland reports personal fees from Astra Zeneca, outside the submitted work. Dr. Semchuk reports grants from Astra Zeneca, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Astra Zeneca, outside the submitted work.

Funding:The article was completed independent of a funding source. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and publication of the article.

References

- 1. Government of Canada. Heart disease—heart health. January 2017. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/heart-disease-heart-health.html (accessed Nov. 12, 2017).

- 2. Statistics Canada. Health indicators 2013. March 2013. Available: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/HI2013_EN.pdf (accessed Jan. 17, 2018).

- 3. National Heart. Lung and Blood Institute. Coronary heart disease. November 2015. Available: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/cad/treatment (accessed Jan. 17, 2018).

- 4. Bell AD, Roussin A, Cartier R, et al. The use of antiplatelet therapy in the outpatient setting: Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines. Can J Cardiol 2011;27(3):S1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spertus JA, Kettelkamp R, Vance C, et al. Prevalence, predictors and outcomes of premature discontinuation of thienopyridine therapy after drug-eluting stent placement: results from the PREMIER registry. Circulation 2006;113(24):2803-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mehta SR, Bainey KR, Cantor WJ, et al. 2018 Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS)/Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology (CAIC) Focused Update of the Guidelines for the Use of Antiplatelet Therapy. Can J Cardiol 2018;34(3):214-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Melloni C, Alexander KP, Ou FS, et al. Predictors of early discontinuation of evidence-based medicine after acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2009;104(2):175-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Airoldi F, Colombo A, Morici N, et al. Incidence and predictors of drug-eluting stent thrombosis during and after discontinuation of thienopyridine treatment. Circulation 2007;116:745-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Czarny MJ, Nathan AS, Yeh RW, et al. Adherence to dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: a systematic review. Clin Cardiol 2014;37(8):505-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murero M, D’Ancona G, Karamanoukian H. Use of the Internet by patients before and after cardiac surgery: telephone survey. J Med Internet Res 2001;3(3):e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leaffer T, Gonda B. The Internet: an underutilized tool in patient education. Comput Nurs 2000;18(1):47-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns 2006;63(1-2):24-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Statistics Canada. Digital technology and Internet use, 2013. June 2014. Available: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/140611/dq140611a-eng.htm (accessed Jan. 17, 2018).

- 15. Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. Communications Monitoring Report 2015: Canada’s communications system: an overview for citizens, consumers and creators. October 2015. Available: https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/publications/reports/PolicyMonitoring/2015/Cmr.pdf (accessed Dec. 27, 2017).

- 16. Meppelink CS, van Weert JC, Haven CJ, Smit EG. The effectiveness of health animations in audiences with different health literacy levels: an experimental study. J Med Internet Res 2015;17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. El-Toukhy H, Omar A, Abou Samra M. Effect of acute coronary syndrome patients’ education on adherence to dual antiplatelet therapy. J Saudi Heart Assoc 2017;29(4):252-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DocMikeEvans. Welcome to Dr. Mike’s YouTube page. Available: https://www.youtube.com/user/DocMikeEvans (accessed Dec. 12, 2017).

- 19. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Pharmacy in Canada. February 2016. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/pharmacy-in-canada/Pharmacy%20in%20Canada.pdf (accessed Jan. 17, 2018).