Abstract

Objective. The aim of this study is to examine the experience of European surgeons on autologous fat transfer (AFT) and highlight differences between countries and levels of experience. Background Data. The popularity of AFT causes an increase in sophisticated scientific research and clinical implementation. While results from the former are well-documented, important aspects of the latter are far less recognized. Methods. An international survey study about surgeon background, besides AFT familiarity, technique, and opinion, was distributed among surgeons from 10 European countries. The differences between countries and levels of experience were analyzed using a logistic regression model. Results. The mean respondent age, out of the 358 completed questionnaires, was 46 years. Ninety-seven percent of the respondents were plastic surgeons, who practiced AFT mostly in breast surgery and considered themselves experienced with the technique. The thigh and abdomen were less favored harvest locations by the Belgium and French respondents, respectively, and both the French and Austrian respondents preferred manual aspiration over liposuction in harvesting the fat. Despite minor differences between countries and experience, the intraglandular space was injected in all subgroups. Conclusions. The expanding use of AFT in Europe will lead to more experience and heterogeneity regarding the technique. However, despite an obvious adherence to Coleman’s method, deviations thereof become more apparent. An important example of such a deviation is the ongoing practice of intraglandular AFT despite being a contraindication in various European guidelines. These unsafe practices should be avoided until scientific clarification regarding oncological safety is obtained and should therefore be the focus of surgeon education in Europe.

Keywords: autologous fat transfer, lipofilling, technique, Europe, opinion, experience

Introduction

Autologous fat transfer (AFT) is becoming an increasingly popular procedure in various areas of plastic surgery. Whether used as a permanent filler in facial rejuvenation1,2 or as a volume-enhancing technique in addition to oncoplastic or cosmetic surgery of the breast, much is written regarding the efficacy and safety as well as various techniques and satisfaction.3-5 Thus, popularity and acceptance is growing. Vice versa, this acceptance leads to more and better research currently being conducted.6 Regarding the AFT technique, the systematic review of Strong et al7 recently showed higher retention rates in clinical studies with centrifugation—as opposed to sedimentation—and slow reinjection into less mobile areas. However, this same advantage could not be found in experimental animal and in vitro studies. Satisfaction rates among patients and surgeons are generally assessed with the use of Likert-type scales8-11 or validated questionnaires such as the Breast-Q.12 Despite the advantages and rising confidence with the procedure, concerns about oncological safety remain, since several experimental studies show potential danger of interaction between adipose-derived stem cells and mammary epithelial cells as well as the potential of CD34+ progenitors in white adipose tissue to promote cancer progression.13-15 Regardless of the increase in clinical acceptance of AFT, questions regarding the gold standard in AFT technique and oncological safety remain, partly because of the gap between clinical and basic science studies. One way to narrow the gap between the laboratory and clinical practices is by way of professional survey studies. Two survey studies among professionals are worth mentioning. Kaufman et al16 in 2007 and Skillman et al17 in 2013 performed a national survey concerning the use of AFT among 508 US, and 228 UK plastic surgeons, respectively. The former study reported mainly on the use of AFT in facial recontouring, and the latter mainly on the use in breasts, but both studies reported a general approval of the technique by surgeons as well as a high rate of surgeon-perceived patient satisfaction. The AFT technique used by the respondents—as reported in the study by Kaufman et al16—rarely deviated from the methods discussed in the literature. Since this study dates from 2007 and reports on US respondents only, and given the recent developments in this field,18-20 it is interesting to look at the current situation in Europe. The primary aim of this study is to report on the experience, practice, and opinion of plastic surgeons and breast surgeons in Europe with the AFT procedure in general and with special emphasis on breast surgery. The secondary aim is to highlight the possible differences between surgeons from different countries, thereby aiding the various national (plastic) surgery associations in finding important topics for upcoming meetings as well as surgeon education.

Methods

An international, multicenter, cross-sectional, closed-ended format, study-specific questionnaire was created regarding AFT in general and with emphasis on breast surgery. The national plastic surgery associations of 10 European countries (The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Great Britain, France, Spain, Italy, Greece, Austria, and Switzerland) were contacted through email and, after introduction, asked for their participation in distributing this questionnaire among their members (active participation). When no reply was received, the organization was contacted on 2 additional occasions with a minimum of a 2-week interval by telephone during which the method and purpose of the study was explained and the organization was again asked for their participation in the study. Participating organizations distributed the questionnaire among its members with a reminder email following after 2 to 4 weeks. In the case of passive participation, no mediation by the national association was obtained in the distribution of the email (addresses). Instead, these were actively searched and collected by the first author through screening of the associations—“Member Information” online link, on the respective website. The questionnaire was constructed in SurveyGizmo, an online digital survey tool and translated in the following languages: Dutch, German, Spanish, Italian, and French by either a native-speaking colleague or an Internet-based translational service (www.onehourtranslation.com). The survey encompassed 36 multiple-choice questions, concerning 4 aspects of AFT, namely, background, AFT familiarity, AFT technique, and AFT opinion (see Figure 1). A free-text section was provided at the bottom of the appropriate questions to allow respondents to add personal comments. The completion of the questionnaire was strictly voluntary and without compensation. The completed questionnaires were entered into a database (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) by one investigator (JG) for further analysis.

Figure 1.

Survey questions.

Please note that—in question #1—the participating countries exceeds the number of countries originally contacted. This is due to the fact the multiple respondents currently practiced in their home country after completing their residency abroad, a period in which they became members of their visiting countries’ national plastic surgery association.

Statistical Analyses

The total number of estimated members of the participating countries (The Netherlands 425, Belgium 181, Germany 400, Great Britain 365, France 770, Spain 643, Italy 473, Austria 199, Switzerland 154, Greece 271)21 was 3881. With this, a sample size of 350 is adequate to achieve a confidence level of 95% with a margin error or confidence interval T5% for the entire population.22 Continuous data are presented as mean, standard deviation, and range. Categorical data are presented as counts or proportions. Differences between baseline characteristics of the respondents from different countries were assessed using t tests for continuous variables (age) and the Kruskal-Wallis test for ordinal variables (number of years of experience and number of procedures performed per year). Differences between both technical choices and attitude toward fat grafting were assessed in relation to country, years of experience (resident, 0-10, 10-20, and >20 years of experience), and number of procedures performed per year (0-10, 10-20, and >30 procedures performed per year). We used logistic regression in case of a binary response variable, ordinal regression in case of an ordinal response variable, and multinomial logistic regression in case of multiple response categories.

Results

Details of the the countries participating, the method by which survey invitations were send (passive vs active), and the response rate are accessible through the online supplementary data (Appendix A1, available in the online version of the article). A total of 358 completed questionnaires were retrieved for analysis over a 10-month period (June 2016 to April 2017). Table 1 illustrates the baseline “respondent” demographics. The mean age was 46 years (SD = 10.8 years), with the majority being plastic surgeon (96.9%), followed by breast surgeons (1.7%) and other (1.4%, mostly German gynecologists). Eighty percent were consultants, with a majority having more than 20 years of practicing experience. Ninety percent disclosed having practiced AFT for general purposes (33.5%) or in addition to breast surgery (56.7%). The majority performed AFT alone (66.2%) in <10 (26.5%) or between 10 and 30 (38.5%) procedures per year, and the vast majority considered himself or herself to be either experienced (41.6%) or moderately experienced (40.5%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| Question/Variable | Outcome: Mean (%) | Missing (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 46 ±10.8 | — | |||||||

| Specialty | — | ||||||||

| • Plastic surgeon | 347 (96.9) | ||||||||

| • Breast surgeon | 6 (1.7) | ||||||||

| • Other | 5 (1.4) | ||||||||

| Training | |||||||||

| • Resident (per year of training) | 57 (15.9) | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | Other | — |

| 5 (1.4) | 5 (1.4) | 7 (2.0) | 11 (3.1) | 8 (2.2) | 15 (4.2) | 6 (1.6) | |||

| • Registered medical specialist (experience) | 288 (80.4) | <5 years | 5-10 years | 10-15 years | 15-20 years | >20 years | 1 (0.3) | ||

| 43 (12.0) | 62 (17.3) | 47 (13.1) | 44 (12.3) | 92 (25.7) | |||||

| • Other | 12 (3.4) | ||||||||

| AFG familiarity | 1 (0.3) | ||||||||

| • Familiar with AFG in general but not for breast procedures | 120 (33.5) | ||||||||

| • Familiar with AFG in general and for breast procedures | 203 (56.7) | ||||||||

| • Not familiar with AFG (never practiced) | 34 (9.5) | ||||||||

| Number of AFG procedures per year | <10 | 10-30 | 30-50 | >50 | 35 (9.9) | ||||

| 95 (26.5) | 138 (38.5) | 48 (13.4) | 42 (11.7) | ||||||

| Perform AFG alone or with colleague | Alone | With colleague | With senior colleague | With resident | 36 (10.1) | ||||

| 237 (66.2) | 23 (6.4) | 30 (8.4) | 32 (8.9) | ||||||

| Experience (self-assessment) | Experienced | Moderately experienced | Moderately unexperienced | Unexperienced | 36 (10.1) | ||||

| 149 (41.6) | 145 (40.5) | 19 (5.3) | 9 (2.5) | ||||||

Technique

The harvest locations most often used were the abdomen (78.8%), the thigh (56.7%), and the flank (55.6%), with most respondents using wetting solution (50 mL of 1% lidocaine plus 1 mL of epinephrine [1:1000] plus 1 L of normal saline) as their primary choice for harvest site infiltration (Table 2). Harvesting of fat was mostly performed by way of a liposuction device (41.9%), preferably through 3-mm cannulas (41.1%). When manual aspiration was used for harvesting (14.0%), most respondents did not know the actual diameter size of the cannula/needle. For preparation most respondents performed centrifugation (38.8%) besides washing of the fat (21.2%). Seventy-five percent of the respondents used a cannula to reinject the fat, aiming at 1 to 2 cc (30.7%) or >4 cc (21.5%) of volume per pass. Overcorrection was used by most respondents (80.5%) ranging from 20% to 30% (28%) to more than 50% (3.1%). In breast surgery, more than half (52%) of the respondents grafted the subcutaneous plane in addition to both flap and implant reconstructions as well as the correction of local defects. For flap reconstructions, other planes most commonly grafted were the subglandular (31.8%) and the pectoral (29.9%) spaces with more than half of the respondents aiming at a total grafted volume of 50 to 100 cc (36.2%) or 100 to 150 cc (24.1%). For implant reconstruction/augmentation and for local defect correction (LDC), the preferred planes of reinjection were pectoral (21.8%) versus subglandular (20.9%) and intraglandular (29.9%) versus subglandular (29.1%) spaces, respectively. Methods for AFT take enhancement varied from none (33.8%) to rigottomies (21.5%) and preoperative and postoperative external expansion devices like the Breast Enhancement and Shaping System (BRAVA) in a few select cases (7.5% and 6.1%, respectively).

Table 2.

AFT Technique and Opinion.

| AFT Technique | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question/Variable | Outcome: Mean (%) | Missing (%) | ||||||

| Harvest locationa | Gluteal | Thigh | Flank | Abdomen | Knee | Other | — | |

| 25 (7.0) | 203 (56.7) | 199 (55.6) | 282 (78.8) | 92 (25.7) | 15 (4.2) | |||

| Anesthesia at harvest location | 0.5% Lido. + Epi | 1% Lido. + Epi | Wetting solution | Epinephrine | Other | 37 (10.3) | ||

| 24 (6.7) | 37 (10.3) | 186 (52.0) | 26 (7.3) | 48 (13.4) | ||||

| Harvesting technique | Cannula + constant suction | Coleman technique (with micro-cannula) | Syringe + large-bore needle | Other | 37 (10.3) | |||

| 150 (41.9) | 98 (27.4) | 50 (14.0) | 23 (6.4) | |||||

| Harvest Cannula diameter | ||||||||

| • Liposuction device | 1 mm | 2 mm | 3 mm | 4 mm | Unknown | Other | 37 (10.3) | |

| 24 (6.7) | 72 (20.1) | 147 (41.1) | 39 (10.9) | 25 (7.0) | 14 (3.9) | |||

| • Syringe | 14 Gauge | 16 Gauge | 18 Gauge | Unknown | Other | 43 (12.0) | ||

| 43 (12.0) | 64 (17.9) | 40 (11.2) | 147 (41.1) | 21 (5.9) | ||||

| Fat preparation | None | Washing | Centrifugation | Adding insulin | Decantation | Other | 53 (14.8) | |

| 12 (3.4) | 76 (21.2) | 139 (38.8) | 2 (0,6) | 47 (13.1) | 29 (8.1) | |||

| Freeze fat (yes/nn) | Yes | No | 37 (10.3) | |||||

| 10 (2.8) | 311 (86.9) | |||||||

| Anesthesia at injection site | 0.5% Lido. + Epi | 1% Lido. + Epi | Wetting solution | Epinephrine | None | Other | 45 (12.6) | |

| 19 (5.3) | 68 (19.0) | 34 (9.5) | 3 (0.8) | 162 (45.3) | 27 (7.5) | |||

| Method of injection | Cannula | Needle | Ratchet gun | Other | 38 (10.6) | |||

| 268 (74.9) | 45 (12.6) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (1.7) | |||||

| Estimated volume of injection per pass | <1 cc | 1-2 cc | 2-4 cc | >4 cc | Unknown | 38 (10.6) | ||

| 68 (19.0) | 110 (30.7) | 43 (12.0) | 77 (21.5) | 22 (6.1) | ||||

| Overcorrection (aim) | None | <10% | 10-20% | 20-30% | 30-40% | 40-50% | >50% | 40 (11.2) |

| 30 (8.4) | 32 (8.9) | 96 (26.8) | 99 (27.7) | 40 (11.2) | 10 (2.8) | 11 (3.1) | ||

| Grafted anatomical planes per indicationa | Subcutaneous | Intraglandular | Subglandular | Pectoral | Subpectoral | Other | ||

| • Flap recon structions | 186 (52.0) | 83 (23.2) | 114 (31.8) | 107 (29.9) | 43 (12.0) | 12 (3.4) | ||

| • Implant recon struction/augmentation | 186 (52.0) | 66 (18.4) | 75 (20.9) | 78 (21.8) | 25 (7.0) | 7 (2.0) | ||

| • Local defect corrections | 186 (52.0) | 107 (29.9) | 104 (29.1) | 78 (21.8) | 32 (8.9) | 8 (2.2) | ||

| AFT Technique | ||||||||

| Question/Variable | Outcome: Mean (%) | Missing (%) | ||||||

| • Flap reconstructions | 21 (10.6) | 72 (36.2) | 48 (24.1) | 42 (21.1) | 16 (8.0) | 159 (44.4) | ||

| • Implant reconstruction/augmentation | 39 (19.6) | 73 (36.7) | 44 (22.1) | 31 (15.6) | 12 (6.0) | |||

| • Local defect corrections | 39 (19.6) | 95 (47.7) | 47 (23.6) | 17 (8.5) | 1 (0.5) | |||

| AFG enhancementa | None | BRAVA preop | BRAVA postop | Rigottomies | Other | |||

| 121 (33.8) | 27 (7.5) | 22 (6.1) | 77 (21.5) | 8 (2.2) | ||||

| AFT Opinion | ||||||||

| Question/Variable | Outcome: Mean (%) | Missing (%) | ||||||

| General opinion (agreement with AFG) | Strongly agree | Agree | Somewhat agree | Undecided | Somewhat disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | 6 (1.7) |

| 171 (47.8) | 136 (38.0) | 28 (7.8) | 6 (1.7) | 8 (2.2) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Estimated volume retention >6 months | <30% | 40-50% | 50-60% | 60-70% | 70-80% | >80% | 5 (1.4) | |

| 47 (13.1) | 84 (23.5) | 78 (21.8) | 101 (28.2) | 33 (9.2) | 10 (2.8) | |||

| Estimated cause of volume retention | Fat survival | Replacement with scar tissue | Combination (fat survival + scar tissue replacement) | Other | 6 (1.7) | |||

| 179 (50.0) | 9 (2.5) | 150 (41.9) | 14 (3.9) | |||||

| Estimated patient satisfaction with AFG | Excellent | Good | Poor | 5 (1.4) | ||||

| 184 (51.4) | 142 (39.7) | 27 (7.5) | ||||||

Abbreviations: Lido., lidocaine; Epi, epinephrine; wetting solution (50 mL of 1% lidocaine + 1 mL of epinephrine [1:1000] plus 1 liter of saline); BRAVA, Breast Enhancement and Shaping System; preop, preoperatively; postop, postoperatively.

Multiple answers possible.

Attitude

The vast majority of respondents strongly agreed (47.8%) or agreed (38.0%) with the use of AFT for appropriate indications (Table 2), with an almost equal distribution of respondents estimating the volume retention after 6 months to be in the range of 40% to 50% (23.5%), 50% to 60% (21.8%), or 60% to 70% (28.2%). There was a clear division in the opinion about causative factors when it comes to volume retention, with approximately half of the respondents attributing the results to fat survival (50%) or a combination of fat survival and scar tissue replacement (41.9%). Patient satisfaction as estimated by the surgeon was either excellent (51.4%) or good (39.7%) in the majority of respondents.

Differences Between Countries, Surgeon Experience, and AFT Procedure Performed per Year

Due to the small numbers of respondents for most participating countries (Denmark, Great Britain, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Greece) a comparison could only be made between the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Austria, with the remaining countries pooled together as “other.” Furthermore, since no consensus and therefore gold standard currently exists regarding the AFT technique, no deviation thereof with regard to the various countries analyzed can be calculated. Therefore, the largest group of respondents (the Netherlands) was considered as an arbitrary baseline (see Table 3a).

Table 3.

Outcome per Country, Years of Overall Experience, and AFT Procedures Performed Yearlya.

| 3a. Outcome per Country | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands (Baseline)b | Belgium | France | Austria | Other | |

| No. of respondents (%) | 141 (39.4) | 42 (11.7) | 65 (18.2) | 30 (8.4) | 80 (22.3) |

| Mean age ± SD | 42 ± 10 | 46 ± 11 ↑* | 51 ± 10 ↑*** | 45 ± 10 ↑ns | 50 ± 10 ↑*** |

| Experience (%) | |||||

| • Resident | 32.8 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 10.3 | 9.5 |

| • Specialist (0-10 years) | 43.3 | 40 | 23.4 | 41.4 | 18.9 |

| • Specialist (10-20 years) | 21.9 | 27.5 | 28.1 | 31.0 | 31.1 |

| • Specialist (>20 years) | 10.9 | 27.5 ↑*** | 48.4 ↑*** | 17.2 ↑* | 40.5 ↑*** |

| AFT procedures/year (%) | |||||

| • <10 | 47.9 | 15.0 | 18.5 | 20.0 | 21.1 |

| • 10-30 | 38.5 | 47.5 | 35.4 | 48.0 | 51.3 |

| • >30 | 13.7 | 37.5 ↑*** | 46.2 ↑*** | 32.0 ↑* | 27.6 ↑*** |

| Harvest location (%) | |||||

| • Thigh | 55.3 | 50.0 ↓* | 72.3 | 56.7 | 50.0 ↓* |

| • Abdomen | 75.2 | 78.6 | 81.5↓ *2 | 70.0 | 86.3 |

| Local (donor site) anesthesia (%) | |||||

| • Wetting solution | 69.8 | 50.0 | 34.4 ↓*** | 64.0 | 61.8 |

| Harvesting technique (%) | |||||

| • Liposuction device | 65.5 | 57.5 | 39.1 ↓*** | 28.0 ↓*** | 52.6 ↓* |

| Liposuction cannula (%) | |||||

| • <2 mm | 43.8 | 30.8 | 24.2 | 13.0 | 39.1 |

| • >3 mm | 56.2 | 69.2 | 75.8 ↑** | 87.0 ↑** | 60.9 |

| Preparation (%) | |||||

| • Washing | 27.6 | 31.3 | 22.8 | 20.0 ↓* | 21.3 |

| • Centrifugation | 44.0 | 43.8 | 68.4 ↑** | 16.0 ↓** | 41.3 |

| Estimated volume per pass (%) | |||||

| • <1 cc | 26.5 | 20.5 | 5.1 | 12.5 | 36.5 |

| • 1-2 cc | 46.1 | 38.5 | 15.3 | 54.2 | 35.1 |

| • >2 cc | 27.5 | 41.0 | 79.7 ↑*** | 33.3 | 28.4 |

| Overcorrection (%) | |||||

| • None | 10.3 | 0.05 | 4.7 | 20.0 | 11.0 |

| • <20 | 42.2 | 42.5 | 32.8 | 32.0 | 45.2 |

| • 20-30 | 26.7 | 35.0 | 37.5 | 32.0 | 30.1 |

| • >30 | 20.7 | 17.5 | 25.0 ↑* | 16.0 | 13.7 |

| AFT + Flap reconstruction; injection planes (%) | |||||

| • Subcutaneous | 54.6 | 52.4 | 46.2 ↓** | 53.3 | 51.2 ↓* |

| • Intraglandular | 25.5 | 35.7 | 26.2 | 0.0 | 18.8 ↓* |

| • Subpectoral | 7.1 | 19.0 | 27.7 ↑* | 3.3 | 7.5 |

| AFT + Implant reconstruction/augmentation; injection planes (%) | |||||

| • Subcutaneous | 55.3 | 52.4 ↓* | 47.7 ↓*** | 50.0 | 50.0 ↓** |

| AFT + Local defect corrections; injection planes (%) | |||||

| • Subcutaneous | 53.9 | 52.4 | 46.2 ↓** | 56.7 | 51.3 ↓* |

| • Intraglandular | 38.3 | 38.1 | 24.6 ↓** | 16.7 ↓* | 20.0 ↓*** |

| AFT + Flap reconstruction; estimated total injection volume | |||||

| • <100 | 62.4 | 30.4 | 9.4 | 47.1 | 52.4 |

| • 100-150 | 25.9 | 26.1 | 15.6 | 35.3 | 21.4 |

| • >150 | 11.8 | 43.5 ↑* | 75.0 ↑*** | 17.6 | 26.2 |

| 3b. Outcome per Year of Experience | |||||

| Residents (Baseline) | <10 | 10-20 | >20 | ||

| No. of respondents (%) | 57 (15.9) | 104 (29.1) | 91 (25.4) | 92 (25.7) | |

| Harvest location (%) | |||||

| • Flank | 47.3 | 59.6 ↓*c | 65.9 ↓*c | 48.9 ↓**c | |

| Harvesting technique (%) | |||||

| • Liposuction device | 47.1 | 47.5 ↑* | 52.2 ↑* | 62.9 ↑** | |

| Liposuction cannula (%) | |||||

| • <2 mm | 18.2 | 30.3 | 31.7 | 44.4 ↑* | |

| • >3 mm | 81.8 | 69.7 | 68.3 | 55.6 | |

| Estimated volume per pass (%) | |||||

| • <1 cc | 23.1 | 13 | 25.0 | 31.3 | |

| • 1-2 cc | 38.5 | 50.0 | 33.0 | 26.5 | |

| • >2 cc | 38.5 | 37.0 | 42.0 | 42.2 | |

| 3c. Outcome per AFT Procedures Performed Yearly | |||||

| <10 Proc./Year (Baseline) | 10-30 Proc./Year | >30 Proc./Year | |||

| No. of respondents (%) | 95 (26.5) | 138 (38.5) | 90 (25.1) | ||

| Harvest location (%) | |||||

| • Flank | 50.5 | 61.6 ↑* | 73.3 ↑** | ||

| Harvesting technique (%) | |||||

| • Liposuction device | 67.4 | 50.0 ↓* | 43.2 ↓* | ||

| AFT + Flap reconstruction; injection planes (%) | |||||

| • Subcutaneous | 53.7 | 57.2 | 62.2 ↑* | ||

| • Subglandular | 23.2 | 34.8 | 48.9 ↑** | ||

| • Pectoral | 20.0 | 30.4 | 51.1 ↑*** | ||

| AFT + Implant reconstruction/augmentation; injection planes (%) | |||||

| • Intraglandular | 15.8 | 18.1 | 28.9 ↑* | ||

| Subglandular | 15.8 | 23.2 | 31.1 ↑* | ||

| Pectoral | 16.8 | 21.7 | 35.6 ↑* | ||

| AFT + Local defect corrections; injection planes (%) | |||||

| • Subcutaneous | 52.6 | 55.8 | 65.6 ↑** | ||

| • Subglandular | 26.3 | 29.7 | 42.2 ↑* | ||

| • Pectoral | 11.6 | 22.5 | 40.0 ↑*** | ||

Abbreviation: AFT, autologous fat transfer.

The arrow (↓, ↑) indicates the value in which the country (3a), the experience (3b), or the AFT procedures performed yearly (3c) differs from the baseline (↓ = lower/less; ↑ = higher/more).

Arrows in the columns depict significant deviations from the baseline (column “Netherlands” in 3a, column “Residents” in 3b, and column “<10 proc./year” in 3c).

Percentages are based on the data, significance levels are based on model estimates. Discrepancies between differences between percentages and the direction of the arrows are due to correction for other variables in the model.

Significance: ns = P > .05. *P ⩽ .05. **P ⩽ .01. ***P ⩽ .001.

The mean age of the Dutch respondents was significantly lower than that of other countries. The years of experience and number of AFT procedures performed yearly were higher in Belgium, France, Austria, and the other countries combined. Considering harvest locations, the thigh was significantly less used in Belgium and in the other countries combined, and the French respondents were less inclined to use the abdomen compared with the Dutch. The French and Austrian respondents seemed to prefer manual aspiration over a liposuction device and larger over smaller cannula sizes (>3 vs <2 mm) compared with the Dutch respondents. Furthermore, centrifugation was performed significantly more by the French and both centrifugation as well as washing significantly less by the Austrian surgeons, respectively. In addition to both flap and implant (breast) reconstruction as well as in correcting local (mammary) defects, the French respondents performed significantly less AFT in the subcutaneous plane, compared with the Dutch. In addition, so did both the French and the Austrian respondents when it came to intraglandular AFT for LDC. On the contrary, in addition to flap (breast) reconstructions, the French performed significantly more subpectoral fat injections. Finally, when asked about the amount of injected fat, both the French and the Belgian surgeons injected significantly more in addition to flap reconstruction than the Dutch surgeons.

Table 3b and 3c stratify the number of respondents based on their experience and number of AFT procedures performed yearly. What stands out is both the harvesting location as well as technique and cannula size, besides the estimated injected volume. For example, we see that the flank as a harvesting location is more utilized by surgeons who perform more AFT procedures yearly, but is used less by surgeons with more overall clinical experience. On the contrary, the use of a liposuction device is less often used by both less experienced surgeons as well as surgeons who perform more AFT procedures per year. When looking at the different injection planes used, compared with the number of AFT procedures performed yearly, there seems to be a direct relationship between the two for all injection planes. In other words, the higher the numbers of AFT procedures performed yearly, the more injection planes are utilized by the surgeon. This holds true for intraglandular injections as well.

Discussion

With the growing popularity of AFT among plastic surgeons, the number of AFT techniques and subsequently the patented AFT devices currently commercially available increases. The obvious attraction of the technique for both patients and surgeons comes forth from the desire to recycle fat tissue for a beneficial—often defect occupying—goal in reconstructive or augmentational surgery, hence the high surgeon and patient satisfaction rates that are generally reported in clinical studies and systematic reviews.23,24 However, critics of AFT have strong arguments in pointing out the disadvantages, such as uncertainty regarding oncological and radiological safety in breast reconstruction/augmentation, besides unpredictable long-term results. In the United Kingdom, Germany, and France, clinical guidelines are now available to standardize the technique, aiding both clinical practice and reproducibility among scientific studies. In this light an overview of real-time clinical practice of AFT in Europe identifying differences between countries might aid further scientific studies in the search for the gold standard in AFT.

Despite an adequate overall response rate we found a low response rate per country, which may have been attributable to the headline of the survey invitation. This revealed the technical aspect of some of the questions, which might have discouraged surgeons who never practice AFT to respond. More than a quarter of the respondents had >20 years of practicing experience and higher rates of these more experienced surgeons were found in all of the other countries compared with the Netherlands. This was probably attributable to the higher number of residents among the Dutch respondents. Our survey showed that breast surgery is still the most prominent indication for AFT in Europe. Also, the majority of surgeons performed AFT alone, in accordance with the findings of Skillman et al,17 showing that while AFT can be time consuming, it is not a two-man’s job necessarily. While AFT is a popular procedure, it is still not practiced often, with 26.5% of the respondents performing less than 10 AFT procedures per year and only 11.7% performing more than 50. These findings are in-line with Kaufman et al,16 and although a longer learning curve might be the result of the relative few procedures performed, most surgeons considered themselves experienced.

The technique used remains one of the most heterogenic aspects of AFT, and while factors like harvesting technique and preparation seem to be rather uniform with the Coleman technique,25,26 deviations thereof are becoming apparent. The abdomen is still the most prominent harvesting location overall. Second to this is the flank with even higher rates in the subgroup of respondents who perform more AFT procedures. In 2017 Europe, the vast majority (41.9%) of surgeons is using a liposuction device, which might be attributable to the time-saving properties of this technique. The French and the Austrian respondents used a liposuction device significantly less often than the Dutch population, which we hypothesized as possibly due to the higher level of experience (and Coleman technique adherence) of respondents from these countries. While randomized controlled trials comparing both methods are clearly needed, the recent systematic review by Shim et al27 indicated a slight preference for manual aspiration, based on several small-cohort, retrospective and prospective studies.28-31 The preferred cannula size when using a liposuction device was 3 mm in 41%, with an equal percentage of respondents indicating not knowing the cannula size when using manual aspiration. This seems to be an area where improvement can be achieved, since several studies have indicated that the size of both the aspiration and injection cannula (>3 mm to <6 mm) matter significantly in terms of adipocyte viability.32,33 Finally, in terms of injection technique and planes, half of the respondents aimed at injecting <1 to 2 cc of fat, while overcorrecting 10% to 30%, in line with the Coleman method, with only the French injecting more. With regard to breast surgery, when AFT is used in addition to flap reconstruction, implant reconstruction or augmentation, and LDC, the subcutaneous plane was grafted most, followed by the subglandular and pectoral planes. What is interesting to see is that the intraglandular plane was grafted for all indications ranging from 18.4% in addition to implant reconstruction, to 30% in LDC. Even more interesting is the fact that intraglandular injection rates also seemed to be higher in more experienced surgeons based on the number of AFT procedures performed. Both the British and German clinical guidelines34,35 currently strongly advise against the utilization of intraglandular AFT because of the possible carcinogenic differentiation of (remaining dormant) breast (cancer) cells.36-38 While the number of respondents from the United Kingdom and Germany were too low to make any comparisons between countries, the Dutch plastic surgery association (NVPC) advises its members to adhere to the British guidelines and otherwise to keep up-to-date on the most recent scientific literature when performing AFT. The authors presume the same holds true for other countries, but nonetheless, there seems to be a gap between what is recommended and what is actually performed and herein might lay certain benefits from proper surgeon education when it comes to oncological safety of AFT.

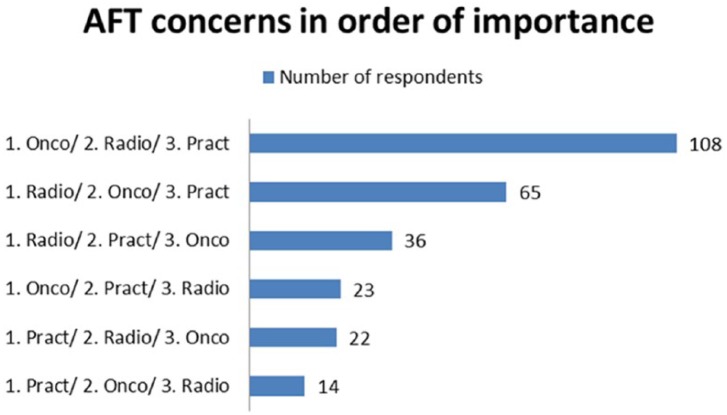

The overall approval of the respondents with AFT in general as well as the surgeon-perceived patient satisfaction was considered high and seems in line with recent studies. The perception of what causes the eventual volume retention was either fat survival or a combination thereof with scar tissue formation, and further histological animal studies, preferably with long-term follow-up, are needed to substantiate the answer to this question. Finally, concerns with AFT in breast surgery are mainly regarding oncological safety, radiological safety, or practical issues. Figure 2 highlights the order in which these concerns troubled the respondents, illustrating that further studies should focus on the oncological and radiological safety of the technique.

Figure 2.

Respondents’ concerns with the practice of autologous fat transfer (AFT) in order of most clinically important.

Oncology: “The transplantation of adipose-derived stem cells and CD34+ progenitors in white adipose tissue poses a risk to promote cancer progression.”

Radiology: “The use of AFG in breast surgery impairs future radiological follow-up and breast cancer screening because of the frequent formation of fat necrosis and micro-/macro-calcifications.”

Practice: “The use of AFG in breast surgery is associated with unacceptable complications such as hematomas, infections, and the need for draining oily cysts/fat necrosis.”

Limitations

The information gathered by survey studies is dependent on honest answers. While the authors trust the intentions of the respondents, the accuracy of the answers given can—on a subconscious level—be colored by embarrassment, lack of memory, alacrity, or even boredom.39 Furthermore, the survey was distributed among a select group of physicians, namely, plastic surgeons and breast surgeons who happened to be members of a plastic surgery association. Therefore, large numbers of—possible AFT practicing—surgeons (like members of the United Kingdom; Royal Colleges of Surgeons) were potentially missed and discrepancy between responders and nonresponders can create a selection bias. Finally, while the questions leave little room for interpretation, certain options like “somewhat agree” can mean different things to different individuals. Nonetheless, for the first time we were able to highlight differences in AFT technique between countries and levels of experience and point out the ongoing practice of intraglandular fat grafting in conjunction with breast surgery.

Conclusion

This study provides the first overview of clinical practice regarding AFT in Europe and highlights important differences between countries that can aid in the focus of future studies as well as point out discrepancies in the physician adherence to clinical guidelines. The overall experience with AFT among respondents was moderate to high, with most applying its use in addition to breast surgery. Coleman’s method is still the most widely used AFT technique but deviations thereof lay in the areas of harvesting technique and cannula sizes. The injection planes of AFT, in addition to breast surgery, are in order of most used: the subcutaneous, subglandular, and pectoral planes. However, despite prominent discouragement of the British and German clinical guidelines, intraglandular AFT still occurs in clinical practice today and this should be the focus of further surgeon education in Europe. Finally, it is the authors’ hope that this “pilot study” into the realm of real-time reporting on the clinical practice of AFT may incite more prospective studies on the subject that may even one day lead to a European “Fat Grafting” database.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Online_Appendix_A1;_Participating_European_countries. for European Survey Study Among Plastic/Breast Surgeons on the Use of and Opinion Toward Autologous Fat Transfer: With Emphasis on Breast Surgery by Jan-Willem Groen, Andrzej A. Piatkowski, John H. Sawor, Janneke A. Wilschut, Marco J. P. F. Ritt and Rene R. J. W. van der Hulst in Surgical Innovation

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Shan Shan Qui, MD, PhD, Denise Zuniga, MD, and Camille Guillaume, MD, for their tremendous work in translating the questionnaires.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Jan-Willem Groen, Andrzej A. Piatkowski, John H. Sawor

Acquisition of data: Jan-Willem Groen, Andrzej A. Piatkowski, Rene R. J. W. van der Hulst

Analysis and interpretation: Janneke A. Wilschut, Marco J. P. F. Ritt

Study supervision: Rene R. J. W. van der Hulst, Marco J. P. F. Ritt

Authors’ Note: Andrzej A. Piatkowski is also affiliated with Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Hand Surgery, Viecuri Medical Center, Venlo, The Netherlands. John H. Sawor is also affiliated with Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Hand Surgery, Viecuri Medical Center, Venlo, The Netherlands. Janneke A. Wilschut is also affiliated with Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD: Jan-Willem Groen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5513-5813

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5513-5813

References

- 1. Chou CK, Lee SS, Lin TY, et al. Micro-autologous fat transplantation (MAFT) for forehead volumizing and contouring. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:845-855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tepavcevic B, Radak D, Jovanovic M, Radak S, Tepavcevic DK. The impact of facial lipofilling on patient-perceived improvement in facial appearance and quality of life. Facial Plast Surg. 2016;32:296-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ismail T, Burgin J, Todorov A, et al. Low osmolality and shear stress during liposuction impair cell viability in autologous fat grafting. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:596-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kronowitz SJ, Mandujano CC, Liu J, et al. Lipofilling of the breast does not increase the risk of recurrence of breast cancer: a matched controlled study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:385-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Streit L, Jaros J, Sedlakova V, et al. A comprehensive in vitro comparison of preparation techniques for fat grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:670e-682e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krastev T, Hommes J, Piatkowski A, van der Hulst RRWJ. Breast reconstruction with external pre-expansion and autologous fat transfer versus standard therapy (BREAST). NCT02339779. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02339779. Published January 15, 2015.Accessed August 24, 2018.

- 7. Strong AL, Cederna PS, Rubin JP, Coleman SR, Levi B. The current state of fat grafting: a review of harvesting, processing, and injection techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:897-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chiu CH. Autologous fat grafting for breast augmentation in underweight women. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34:1066-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chiu CH. Correction with autologous fat grafting for contour changes of the breasts after implant removal in Asian women. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:61-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li FC, Chen B, Cheng L. Breast augmentation with autologous fat injection: a report of 105 cases. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73(suppl 1):S37-S42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spear SL, Pittman T. A prospective study on lipoaugmentation of the breast. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34:400-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mestak O, Sukop A, Hsueh YS, et al. Centrifugation versus PureGraft for fatgrafting to the breast after breast-conserving therapy. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lohsiriwat V, Curigliano G, Rietjens M, Goldhirsch A, Petit JY. Autologous fat transplantation in patients with breast cancer: “silencing” or “fueling” cancer recurrence? Breast. 2011;20:351-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Martin-Padura I, Gregato G, Marighetti P, et al. The white adipose tissue used in lipotransfer procedures is a rich reservoir of CD34+ progenitors able to promote cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2012;72:325-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petit JY, Botteri E, Lohsiriwat V, et al. Locoregional recurrence risk after lipofilling in breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:582-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaufman MR, Bradley JP, Dickinson B, et al. Autologous fat transfer national consensus survey: trends in techniques for harvest, preparation, and application, and perception of short- and long-term results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:323-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Skillman J, Hardwicke J, Whisker L, England D. Attitudes of UK breast and plastic surgeons to lipomodelling in breast surgery. Breast. 2013;22:1200-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gentile P, De Angelis B, Pasin M, et al. Adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction cells and platelet-rich plasma: basic and clinical evaluation for cell-based therapies in patients with scars on the face. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khouri RK, Rigotti G, Cardoso E, Khouri RK, Jr, Biggs TM. Megavolume autologous fat transfer: part II. Practice and techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:1369-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khouri RK, Rigotti G, Cardoso E, Khouri RK, Jr, Biggs TM. Megavolume autologous fat transfer: part I. Theory and principles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:550-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. ISAPS International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic. Procedures performed in 2014. https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2015-ISAPS-Results-1.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- 22. Hulley SB CS, Browner WS. Designing Clinical Research. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Groen JW, Negenborn VL, Twisk DJWR, et al. Autologous fat grafting in onco-plastic breast reconstruction: a systematic review on oncological and radiological safety, complications, volume retention and patient/surgeon satisfaction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:742-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Groen JW, Negenborn VL, Twisk JW, Ket JC, Mullender MG, Smit JM. Autologous fat grafting in cosmetic breast augmentation: a systematic review on radiological safety, complications, volume retention, and patient/surgeon satisfaction. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:993-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coleman SR. The technique of periorbital lipoinfiltration. Oper Tech Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;1:20-26. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coleman SR. Lipoinfiltration of the upper lip white roll. Aesthet Surg J. 1994;14:231-234. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shim YH, Zhang RH. Literature review to optimize the autologous fat transplantation procedure and recent technologies to improve graft viability and overall outcome: a systematic and retrospective analytic approach. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:815-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. He ZX, Donglai G, Jianhua G. The observation of human body adipose tissue damage degree by the method of drawing. Chin J Plast Surg. 2001;17:290-291. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lalikos JF, Li YQ, Roth TP, Doyle JW, Matory WE, Lawrence WT. Biochemical assessment of cellular damage after adipocyte harvest. J Surg Res. 1997;70:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leong DT, Hutmacher DW, Chew FT, Lim TC. Viability and adipogenic potential of human adipose tissue processed cell population obtained from pump-assisted and syringe-assisted liposuction. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;37:169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith P, Adams WP, Jr, Lipschitz AH, et al. Autologous human fat grafting: effect of harvesting and preparation techniques on adipocyte graft survival. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1836-1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erdim M, Tezel E, Numanoglu A, Sav A. The effects of the size of liposuction cannula on adipocyte survival and the optimum temperature for fat graft storage: an experimental study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:1210-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ozsoy Z, Kul Z, Bilir A. The role of cannula diameter in improved adipocyte viability: a quantitative analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2006;26:287-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fatah F, Lee M, Martin L. Lipomodelling guidelines for breast surgery. Joint Guidelines from the Association of Breast Surgery, the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons, and the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons. http://www.bapras.org.uk/docs/default-source/commissioning-and-policy/2012-august-lipomodelling-guidelines-for-breast-surgery.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Published August 2012. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- 35. Rennekampf HO, Sattler G, Bull G, Rezek D. Leitli-nie: “Autologe Fetttransplantation.” https://www.dgpraec.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/S2k_Leitlinie_Fetttransplantation.pdf. Published November 2015. Accessed August 28, 2018.

- 36. Bertolini F. Contribution of endothelial precursors of adipose tissue to breast cancer: progression-link with fat graft for reconstructive surgery. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2013;74:106-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Charvet HJ, Orbay H, Wong MS, Sahar DE. The oncologic safety of breast fat grafting and contradictions between basic science and clinical studies: a systematic review of the recent literature. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;75:471-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krumboeck A, Giovanoli P, Plock JA. Fat grafting and stem cell enhanced fat grafting to the breast under oncological aspects—recommendations for patient selection. Breast. 2013;22:579-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Helmerhorst HJ, Brage S, Warren J, Besson H, Ekelund U. A systematic review of reliability and objective criterion-related validity of physical activity questionnaires. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Online_Appendix_A1;_Participating_European_countries. for European Survey Study Among Plastic/Breast Surgeons on the Use of and Opinion Toward Autologous Fat Transfer: With Emphasis on Breast Surgery by Jan-Willem Groen, Andrzej A. Piatkowski, John H. Sawor, Janneke A. Wilschut, Marco J. P. F. Ritt and Rene R. J. W. van der Hulst in Surgical Innovation