Abstract

Background

A theoretical model of individuals' experiences before, during and after involuntary admission has not yet been established.

Aims

To develop an understanding of individuals' experiences over the course of the involuntary admission process.

Method

Fifty individuals were recruited through purposive and theoretical sampling and interviewed 3 months after their involuntary admission. Analyses were conducted using a Straussian grounded theory approach.

Results

The ‘theory of preserving control’ (ToPC) emerged from individuals' accounts of how they adapted to the experience of involuntary admission. The ToPC explains how individuals manage to reclaim control over their emotional, personal and social lives and consists of three categories: ‘losing control’, ‘regaining control’ and ‘maintaining control’, and a number of related subcategories.

Conclusions

Involuntary admission triggers a multifaceted process of control preservation. Clinicians need to develop therapeutic approaches that enable individuals to regain and maintain control over the course of their involuntary admission.

Declaration of interest

None.

Keywords: Control, detention, grounded theory, involuntary admission, Mental Health Act

In the Republic of Ireland, the Mental Health Act 2001,1 updated the legislative framework within which an individual could be admitted, detained and treated involuntarily. To date, few grounded theory studies have been conducted that have explored individuals' experiences while admitted involuntarily to hospital. Loft and Lavender in their grounded theory study explored the experiences of individuals with psychosis admitted to hospital involuntarily and it included 8 patients (aged 18–65 years) and 9 consultant psychiatrists.2 Seed and colleagues explored the experience of 12 patients diagnosed with anorexia nervosa (aged 18–55 years) admitted involuntarily to a private in-patient facility.3 These studies highlighted the initial distress experienced by individuals on admission,2 how this distress had an impact on their relationship with clinicians,3 how individuals' opinions change about their management during their hospital admission3 and the relief experienced by individuals at the prospect of discharge.2 However, both these studies included modest numbers of participants, primarily focused on individuals' experiences during their admission to hospital, and included individuals with a relatively narrow age range. Consequently, grounded theory studies to date have not examined a large number of individuals in a range of diagnoses and sociodemographic diversity. This present study aims to address these issues by developing a theoretical model to understand individuals' experiences over the course of an involuntary admission.

Method

Research design

Grounded theory was considered the most appropriate methodology because it focuses on developing theory and enables a theoretical understanding of individuals' experiences, before, during and after involuntary admission. Specific attention was given to choosing a version of grounded theory that would prompt the researcher to understand the processes behind individuals' experiences, as well as what was self-reported by the individual. The Straussian version is derived from a constructivist paradigm and uses analytical strategies (such as the coding paradigm), which places an emphasis on the wider context, enabling the researcher to explore if contextual factors influenced experiences.4,5 For this reason, it was a good fit for this study as it assisted the exploration of theoretical perspectives and enabled understanding of the psychological and social processes that contribute to individuals' experiences and their reactions.

Recruitment

A total of 50 individuals, who had been subject to involuntary admissions under the Mental Health Act 2001 and who fulfilled the inclusion criteria (not currently in-patients, no cognitive impairment, able to provide informed written consent for study participation approximately 3 months after termination of their involuntary admission), were recruited from a larger cohort of 156 individuals who agreed to participate and completed follow-up assessments (263 individuals completed the baseline assessments in the follow-up arm of a quantitative prospective study of attitudes towards admission and care in three different in-patient units.6,7 Recruitment to both the quantitative arm of the large study and this grounded theory arm commenced in 2011.

As there was no evolving theory to direct the initial sampling, data collection started with four individuals who met the above inclusion criteria. All four individuals who were contacted 3 months post discharge agreed to be interviewed. These interviews were then analysed prior to subsequent recruitment. This initial analysis also identified areas within the topic guide to be explored in greater depth. Subsequently, recruitment was phased in line with the tenets of grounded theory and theoretical sampling, and involved the concurrent process of recruitment, interviewing and analysis of data from a further 46 more individuals. Although 50 individuals may seem a high number for qualitative research, it is not unusual in grounded theory because large samples are required to ensure maximum variability and a robust theory.

Theoretical sampling

Theoretical sampling was driven by the need to advance the theory, clarify emerging concepts and for comparative purposes ensure that a diversity of individuals with potentially different perspectives and experiences were interviewed. To explore if different contextual factors influenced individuals’ perspectives, people with different sociodemographic and clinical profiles were purposively selected for interview. Individuals with specific characteristics related to age, diagnosis and number of times detained under the act were recruited over the course of the study. As the initial sample included only those between 23 and 65 years of age, two individuals over 80 were specifically recruited as well as individuals who had involuntary admission initiated from within the approved centre and individuals who had their application for involuntary admission made by a family member. In addition, to expand the range of DSM-IV diagnosis,8 one individual with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa was recruited and an individual who had their involuntary admission order revoked at tribunal was interviewed. Theoretical sampling also assisted in the exploration of tentative concepts or the development of theoretical concepts that were not well developed.9 For example, concepts such as: ‘frustration’, and ‘resisting’ emerged early in the study. Thus, in further interviews these concepts were explored. In addition, theoretical sampling also consisted of revisiting the previously collected and analysed data to test out assumptions and check that the emerging patterns were also evident in previous interviews. (see Table 1 for the profile of participants sampled).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical data

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Applicant for individuals transferred from the community (n = 41), n | |

| Member of Garda Síochána (police) | 20 |

| Relative | 17 |

| Authorised officer | 1 |

| Any other person | 3 |

| Individuals who were initially admitted voluntary and who were later subject to the involuntary admission process (n = 9), n (%) | 9 |

| Previous involuntary admissions under Mental Health Act 2001 (n = 49), n (%) | 27 (55.1) |

| Men, n (%) | 29 (58) |

| DSM-IV diagnosis (n = 50), n (%) | |

| Bipolar disorder | 14 (28) |

| Schizophrenia | 13 (26) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 10 (20) |

| Alcohol dependence syndrome | 3 (6) |

| Recurrent depressive disorder | 2 (4) |

| Acute and transient psychotic disorder | 2 (4) |

| Schizophreniform psychosis | 1 (2) |

| Substance-induced psychotic disorder | 1 (2) |

| Anorexia nervosa | 1 (2) |

| Othera | 3 (6) |

| Age, mean (s.d.) range | 42 (14.13), 23–85 |

| Duration of involuntary admission, days: mean (s.d.) range | 23 (24.28), 2–120 |

Two individuals had no diagnosis and the diagnosis for one was classed as ‘other’ because of the fact that consent to medical notes was declined.

Data collection

Data were collected by means of semi-structured audio-recorded interviews by the researcher (D.M.G.) and were transcribed verbatim. Contextual data pertaining to the approved centres were also collected, for example a general description of the environment and therapeutic activities available. The researcher was not involved in the clinical care of any study participants. Interviews took place between the years 2011 and 2013, in out-patients, day centres, individuals' homes, in hotels and one was over Skype.

Interviews were conducted using one of two topic guides. The first topic guide was developed through discussions with the research team using their expertise (self-experience of mental health issues, bioethics, law, psychiatry, psychiatric nursing). It was then refined by the researcher and two experienced qualitative researchers with experience in grounded theory (K.M. and A.H.), one of whom (A.H.) had experience in mental health. The guide was piloted with two individuals to test its ability to generate data of sufficient quality and depth. Following the pilot, the topic guide was revised and used to interview 34 individuals. Using the following introductory open-ended question: ‘With regard to your recent admission, can you tell me what happened to cause you to be admitted to hospital in your own time and in your own words?’, the focus of the guide was to enable each person to share their experiences. Once interviewees began discussing their experiences, follow-up questions were asked, such as: ‘What was it like for you coming to hospital?’; ‘What was it like for you when you first arrived at the hospital?’; ‘What was your stay in hospital like?’; and ‘What was it like immediately after hospital?’.

Later, derived through data analysis, a second more focused topic guide was developed. This consisted of a stock of new questions to assist with elaborating concepts and categories and thus concentrated on further development of the emerging theory. The aim of this phase of data collection was to refine, saturate and integrate categories, in order to identify the core category. In this phase 16 individuals were interviewed. The format of the second topic guide incorporated the same introductory open-ended question, but follow-up questions were more focused on exploring emerging concepts and categories. For example, some concepts such as ‘not wanting help in hospital’ and ‘playing ball’ were probed in-depth. The researcher at this stage acted both flexibly and strategically, allowing the person to recount their experience in whatever sequence they wished, while also asking focused questions on the developing theory. Interviews lasted 8–95 min with a mean length of 47 min. No participant refused to participate in the interviews, although one individual chose not to be audio-recorded, and field notes were recorded instead.

Data analysis

In line with grounded theory a concurrent process of data collection and data analysis5 took place, wherein data were continuously analysed throughout data collection. Three forms of coding were employed (open, axial and selective coding). The first phase of analysis involved open coding the transcript, which involved naming meaningful units of data using a conceptual concept or code. Using comparative analysis, open codes were compared within an individual interview and across interviews for similarities and differences and where relevant collapsed into higher order codes. Following this process, the 345 open codes developed were reduced to 44 higher order codes, which were then integrated and organised into categories. This phase of analysis resulted in preliminary categories that was then used as a framework to guide further data collection and analysis. Using axial coding and constant comparison, subsequent interviews were compared and coded using the emerging framework. If the new data did not fit the coding framework, or if it required a different title to explain its meaning, then a new code or subcategory was created. In order to link subcategories to categories, data was continually compared and interrogated within and between categories. When ‘preserving control’ emerged as the core category with the most explanatory power for the psychosocial process experienced by the participants interviewed, further analysis was completed, through selective coding of all subsequent interviews. Selective coding enabled the development and integration of all the categories within the theory. Interviewing and analysis continued until theoretical saturation of the theory was complete: in that, no new patterns or categories were emerging and linkages between concepts and categories were explicit, well developed and verified through the constant comparative process.10

Some codes that emerged early, such as ‘unnecessary paperwork’ did not earn their way into the theory. Although data analysis is presented in a linear fashion and although the computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software NVivo; (Version 10) was used to assist with data storage and management, the analysis was an iterative process that involved mind mapping, memo writing and discussion with others. The researcher (D.McG.) conducted the preliminary analysis and in order to ensure rigour, two experienced qualitative researchers (K.M. and A.H.), with expertise in grounded theory and qualitative research, reviewed the data and discussed the emerging subcategories and categories. In addition, the emerging theory and supporting data were presented on a continuous basis to the wider research team.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the local hospitals and the National University of Ireland Galway research ethics committees. Participants were informed about the grounded theory part of the study through information sheets and posters and if they expressed interest they were contacted by the researcher (D.McG.) who sought consent. Individuals provided written informed consent for interview and for their clinical notes to be accessed. One individual declined to provide consent to access their clinical notes; therefore, some sociodemographic and clinical data relating to this individual was not available.

Results

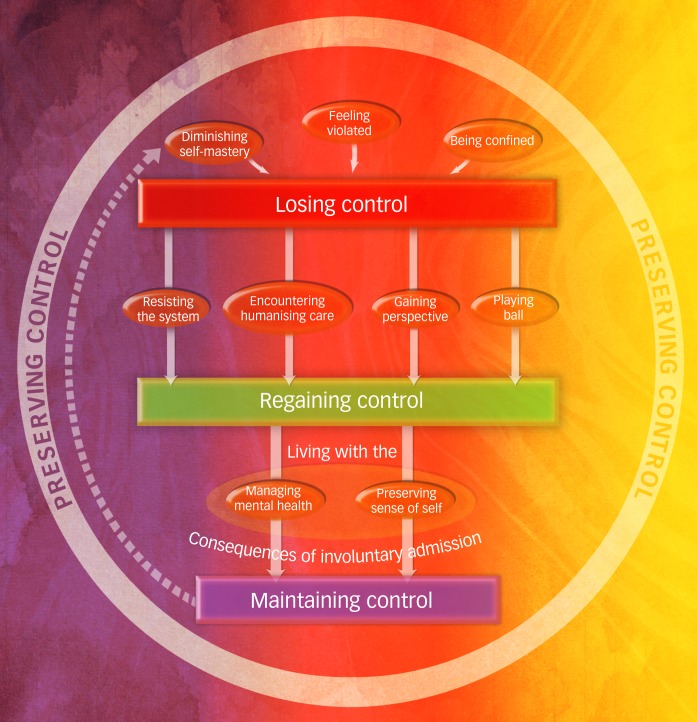

As an outcome of the data analysis process conducted by the researchers, the ‘theory of preserving control’ (ToPC) emerged (Fig. 1). The ToPC consists of three categories: ‘losing control’, ‘regaining control’ and ‘maintaining control’ and was developed to explain the relationship between the categories. The theory describes the extent of loss of control participants experienced when subject to involuntary admission and the ways in which they managed to regain control over their emotional, personal and social lives through the process of preserving control. As the diagram suggests although all participants advanced through the three stages and arrived at the position of ‘maintaining control’, the theory also acknowledges the potential for participants to re-enter the losing control phase, should their mental health deteriorate.

Fig. 1.

The theory of preserving control.

A diagrammatic view of the categories and subcategories of the theory of preserving control. The arrows indicate the direction of progress though the phases with the broken arrow indicating the potential to re-enter the cycle.

Although all individuals experienced a loss of control some experienced a greater loss than others and consequently progressed at differing rates, depending on context. The way(s) in which individuals regained control similarly varied. Some individuals with previous experience of involuntary admission adopted the strategy of ‘playing ball’ much earlier in the process. Additionally, others with no experience of involuntary admission initially adopted a ‘resisting the system’ strategy. Selected participant quotes are provided within the text; however, the Appendix includes a wider range of quotes that support the categories and subcategories identified.

Category 1: ‘losing control’

The first category ‘losing control’ refers to the extent of loss of autonomy individuals experienced as a result of varying levels of mental distress and the extent individuals felt coerced during involuntary admission and subsequent hospital stay. Losing control arose as a result of internal and external pressures on an individual's capacity to control their own life. ‘losing control’ comprised of three subcategories, ‘diminishing self-mastery’, ‘feeling violated’ and ‘being confined’.

Subcategory 1.1: ‘diminishing self-mastery’

This described individuals' retrospective experiences of their becoming unwell, which resulted in them having difficulties in regulating their emotional and social lives. People spoke of changes in their emotions, feeling different and experiencing strange thoughts. Whereas some individuals were clear as to the cause: ‘I started taking drugs. I became paranoid … Everyone knew my business and I couldn't do anything without people talking about me … I felt like everybody … was making a laugh of me’ (participant 25, man), other individuals struggled to make sense of their experience: ‘I didn't really understand what I was going through’ (participant 11, woman).

Subcategory 1.2: ‘feeling violated’

This referred to individuals' experiences of others involvement in the initiation and activation of the involuntary admission procedures and/or their removal to hospital. As participants began to have trouble regulating their lives, others took control, which participants described as not only engendering fear, but was an utter infringement into their lives. ‘I was taken from my place of work against my will … I was very annoyed and furious … I was taken out of my surroundings … Without being explained to me why and … that a GP [general practitioner] could turn around and do something like that and then go off about his business as if nothing happened …’ (participant 50, man). Many experienced coercive interactions with professionals and described feeling frightened as they did not know where they were going: ‘… they [assisted admission team] just dragged me … They put me against the floor, used violence … they handcuffed me and they put me in this plastic yellow blanket and put me in a van or something … I didn't know where I was going.’ (participant 40, woman). When this happened in the presence of neighbours or the public, individuals articulated a consequential sense of embarrassment. Additionally, individuals felt betrayed when they perceived family members may have been involved in initiating their involuntary admission. As a direct consequence, of ‘feeling violated’ peoples' sense of loss of control was further exacerbated.

Subcategory 1.3: ‘being confined’

This was associated with the physical restrictiveness and coercion experienced while in hospital. Individuals described feeling deprived and scared as a result of their loss of liberty and freedom: ‘They [staff] wouldn't let you out in case you ran off … and not being allowed to get out and have fresh air was a major factor to me … I felt restricted … If you think you're in a prison, you're not going to get much better.’ (participant 4, woman); ‘I was trapped, I was locked up …’ (participant 9, man). In addition, many felt coerced into accepting treatment(s) they may not have wanted or perceived they required, with some thus describing being frustrated and badly treated.

Category 2: ‘regaining control’

The second category ‘regaining control’ refers to the manner in which individual's endeavoured to regain control of their autonomy. How control was reclaimed varied; some individuals regained some control when they were supported and facilitated to be involved and make sense of their mental distress, and others adopted self-devised strategies to minimise restriction and coercion. ‘regaining control’ comprises four subcategories: ‘resisting the system’, ‘encountering humanising care’, ‘gaining perspective’ and ‘playing ball’.

Subcategory 2.1: ‘resisting the system’

This describes how some individuals engaged in confrontation with professionals in order assert their autonomy. Individuals verbally asserted themselves; physically protesting and not complying with professionals' directions: ‘I was trying to break free … I was so shocked and angry … I was like shouting and all that’ (participant 33, woman). These strategies were typically associated with those individuals who had no prior experience of involuntary admission. Individuals expressed the view that the focus of their care was predominantly pharmacotherapeutic in nature.

Subcategory 2.2: ‘encountering humanising care’

This describes how participants began to regain control through positive and supportive interactions with people who were in control (for example police and clinicians) and who were willing to take a risk and giving participants some agency and control, despite their legal status. For example, being provided with choice and options such as being allowing to decide on the means of transport to hospital was viewed by participants as an opportunity to regain some control over their situation. ‘I had my car with me … He [Police man] … had me follow him, so he was actually trusting me … the independence … the trust … that was important (participant 38, man)’; Similarly, being listened to, asked for an opinion, or having clinicians that saw the person as opposed to the patient enabled some participants to feel a sense of control and agency over certain aspects of the process of involuntary admission: ‘He [psychiatrist] was very nice … He asked me … how I felt … what brought you here?’ (participant 9, man).

Subcategory 2.3: ‘gaining perspective’

This describes how being provided with treatment approaches (medication and therapeutic relationships), helped people feel calm and think more clearly, make sense of and reappraise what was happening to them: ‘She [nurse] was talking to me as though she believed what was going on in my thoughts … she understood where I was coming from … asking me questions that were trying to make me think introspectively’ (participant 38, man). ‘… when I was in [names hospital] I really sort of faced up to my issues … I think I had a lot of built-up anger, resentment, regrets and other things that had been below the surface for many years and I hadn't sort of dealt with things … I think part of me has always wanted to understand … what's going on … now I understand more about myself …’ (participant 11, woman). As some individuals began to understand and gain perspective they relinquished control to benevolent others (clinicians) as they came to put confidence and trust in a professional they perceived as caring and competent.

Subcategory 2.4: ‘playing ball’

This refers to other strategies adopted by some individuals to limit the extent of coercion exerted upon them. Such individuals saw no benefit from being involuntarily admitted and deliberately monitored what they said to professionals, did not disagree or ask questions of professionals. They conformed to the system by reluctantly agreeing to comply with professionals and treatment, as one participant commented ‘you learn keep your head down, say nothing’ (participant 39, woman).

Category 3: ‘maintaining control’

The third and final category ‘maintaining control’ describes individuals' endeavours to live with the consequences of involuntary admission while managing their readjustment to family, work and wider society following discharge. Individuals not only had to maintain control over their emotional, personal and social lives but they also had to manage, deal and live with the stigma and other people's perception of them.

For some individuals the involuntary admission had a significant impact on their well-being and relationship with others. Some described feeling traumatised by the process ‘When I went to the psychiatrist after 3 months … I said look, I want to go and talk to someone myself … to help you with the post-traumatic stress of being in the hospital in the first place.’ (participant 45, woman). Being involuntarily admitted also had an impact on relationships with family, irrespective of who signed the application for admission. Additionally, some individuals described an ongoing threat of readmission and spoke of feeling under continuous surveillance from both professionals and their families. ‘… it made me aware of how vulnerable I am the system that's there … it's very controlling’ (participant 44, woman). In an attempt to ‘maintain[ing] control’ participants engaged in two strategies conceptualised as ‘managing mental health’ and ‘preserving sense of self’. However, returning home was more daunting than envisaged and consequently, many individuals maintained control only tentatively and lived with the constant fear of once again losing control.

Subcategory 3.1: ‘managing mental health’

This describes the strategies employed by individuals to manage their mental well-being. To minimise the risk of re-entering the cycle of losing control some individuals engaged with community mental health services: ‘… I have a CPN [community mental health nurse] who comes around and who I have regular contact with … someone to talk to, check in … my GP has been supportive … it's been very sort of helpful to be able to talk through a lot of things …’ (participant 10, woman). In addition to traditional services others used strategies that were independent of the mental health service such as using complimentary strategies, monitoring triggers and engaging social supports.

Subcategory 3.2: ‘preserving sense of self’

This describes the strategies used to minimise stigma, and deal and contend with other's perception of them. Individuals were mindful not to state or engage in anything that could be construed as a reason for readmission, opting to conceal certain thoughts or deliberately try to behave in a socially acceptable manner: ‘I'm really afraid to say anything to my husband … I don't give out about people … I think I couldn't start saying any of those things I was saying before that led me to be brought in …’ (participant 44, woman). ‘I have to mind by Ps and Qs because my husband … he'd probably sign me in again’ (participant 39, woman). For other individuals they believed it was easier to isolate themselves as opposed to engage in impression management, with some individuals choosing to distance themselves from the services, in an attempt to forget about their experiences.

Discussion

Main findings and comparison with findings and methodology in previous studies

Previous qualitative international research on people's experiences of involuntary admission and treatment document a complex array of positive and negative experiences. Many individuals report frustration, fear and powerlessness at their loss of autonomy and self-efficacy, as well as lack of information and involvement in decision-making. Other individuals report positive experiences and acknowledge some benefits associated with treatment and care.11–13 Although these studies provide valuable insight into individuals' experience they largely describe patients’ journeys of care. In contrast, to our knowledge, this is the first study to develop a theoretical model that comprehensively explains individuals' experiences before, during and after involuntary admission and that included a large, diverse sample of individuals. The ToPC moves beyond description of individuals' experiences to provide a theoretical model that identifies the contextual factors and conditions that influence experiences.

Although positive and negative experiences have been reported in previous research involving individuals who have been admitted involuntarily, Katsakou et al11 highlight the importance of conducting research that explore factors that may impact on positive and negative perceptions. By revealing unquestioned and unspoken practices the ToPC not only addresses this gap, but provides practical examples of how individuals adapt and respond to different control situations, as well as how they endeavour to produce desirable outcomes and avoid undesirable outcomes. In addition, by demonstrating the usefulness of control-enhancing strategies such as ‘encountering humanising care’ and ‘gaining perspective’ the theory provides professionals with a way of understanding how their interactions can help individuals use strategies to preserve control.

The importance of autonomy

It is unclear how the nature and severity of individuals' clinical presentations may have also had an impact on the ability of professionals to provide explanations and relate responsively with them, or how the level of skill of the clinician had an impact. Professionals should strive to minimise coercive interactions before and during involuntary admissions and increase opportunities for individuals to optimise control-enhancing strategies through developing more specific, sensitive and effective interpersonal communication skills. A systematic review and narrative synthesis of individuals' experiences of recovery has identified empowerment as a dimension in personal recovery in mental health.14 Control and a sense of autonomy is central to promoting empowering and positive relationships and is critical to recovery-focused practices. One way practitioners may assist patients to regain and maintain control is to develop a recovery-focused aftercare plan that identifies support mechanisms and an advanced crisis plan prior to discharge. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 randomised controlled trials, of which 4 investigated advanced statements found that advanced statements were effective in reducing the risk of involuntary admissions by 23%.15 This finding potentially suggests that the introduction of a recovery-focused aftercare plan, developed in collaboration, might potentially reduce subsequent involuntary readmission rates.

The ToPC also indicated that individuals regained control through ‘playing ball’, the realisation that individuals could not control certain aspects of their admission and as a result, refocused their attention on those aspects that were under their control. Contextual factors such as previous experience of involuntary admission and advice from fellow patients may have been formative in adopting a ‘playing ball’ strategy. A previous qualitative study,16 which adopted an interpretative phenomenological analysis, identified a similar concept that the authors titled ‘learning the way’. In the study ‘learning the way’ described how some individuals complied with the taking of medication, not because they believed they required or needed it. Over time individuals learned to adopt a compliance strategy rather than argue with professionals, in order to speed up their discharge.

Stigma

The ToPC can be considered in the context of a grounded theory of individuals' experience of going home from psychiatric hospital: a study entitled ‘managing preconceived expectations’ conducted in a large urban area in the Republic of Ireland.17 The similarities between ‘managing preconceived expectations’ and the ToPC relate to the strategies that individuals employed to minimise the stigma experienced from family and society. However, there are also some differences. Individuals in ‘managing preconceived expectations’ were most typically admitted voluntarily. In the ToPC, aspects of ‘preserving sense of self’ – although referring to the strategies for dealing with stigma, also referred to the strategies that individuals used to prevent family members thinking that they needed to be readmitted to hospital. Although the fear of being stigmatised is similar in both theories, many individuals in the ToPC felt that they were judged negatively on the basis that their admission was involuntary as well as the public manner in which some were removed to hospital.

Implications for mental health practice

The ToPC demonstrated the importance of attending to aspects of control throughout the entire course of the admission process. For example, the process of removal to hospital was reported by many individuals as extremely traumatic. However, several positive accounts of humanising care during this difficult process enabled individuals to preserve some control even at this early stage of the admission process. Central to this was the interactions individuals had with those involved in their removal to hospital such as police. Some positive stories also emerged about the impact of meeting empathic flexible professionals, being provided with an explanation, which enabled individuals to regain a sense of control from the outset and, in some instances, even during their removal to hospital.

The perception that professionals were genuine, that they were acting out of concern contributed to individuals having trust in their expertise and in the development of more therapeutic relationships. In addition, allowing individuals the opportunity to participate and/or be involved in some aspect of the involuntary admission and/or treatment influenced their experience of control.

Professionals need to support individuals to regain and maintain control as well as responding to distress and treating illness. As such, promoting control-enhancing strategies should be a significant focus of clinical interactions by providing explanation, involving in and supporting decision-making and providing humanising care.

Limitations

Although the theory was developed, using purposive and theoretical sampling, from a large and diverse sample that broadly represents the range of clinical presentations and sociodemographic backgrounds of people presenting for involuntary care (Bainbridge et al, under review), and therefore has broad applicability, the theory needs to be considered in light of the following limitations. We interviewed individuals 3 months following discharge as we thought this was the point where individuals were likely to have recovered sufficiently and had a significant amount of time to reflect on their experience prior to discussing it with others. However, the retrospective nature of the interviews may have influenced perceptions of the necessity of involuntary admission and introduced a recall bias. A study undertaken in 201118 reported that 1 year after the involuntary admission order was rescinded, the number of individuals who perceived their involuntary detention as necessary dropped from 72 to 60%. A longitudinal design that involved repeated assessments with participants from in-patient to out-patient might have better captured changes over time. Some individuals who were asked to participate did not consent to be interviewed, or were unable to discuss their experiences of involuntary admission, thus the theory was shaped by those who consented. Had those individuals been involved their perspective may have added to the comprehensiveness of the theory developed.

In conclusion, this paper provides clinicians with a theoretical model for understanding individuals' experiences before, during and after being subject to involuntary admission as well as understanding how individuals adapt to being admitted involuntarily. The manner in which clinicians and/or families initially activate and implement involuntary admission procedures has an impact on how individuals appraise the early days of admission to hospital and is critical and formative in the shaping of an individual's overall experience. Where the initial loss of control was minimised, and where individual's regained control earlier, the experience of involuntary admission was more positive. This indicates that in addition to effective interventions during periods of illness exacerbation, clinicians need to develop therapeutic approaches to support individuals with regaining and maintaining control across the entire course of their involuntary admission, and that such approaches are likely to optimise the therapeutic nature of coercive care and future engagement with services.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the individuals who gave their time to recount their experiences and to our clinical and administrative colleagues who assisted with recruitment.

Appendix

Appendix. 1.

Participant quotes within categories

| Losing control | |

| Diminished self-mastery | ‘… it was hard to sleep … Some nights I didn't sleep any more than maybe 2 hours … but eventually I was getting wore out … I was very … nervous … and not able to concentrate and work properly …’ (Participant 35, man) ‘Thinking unbelievable things and thinking they might be true … I was watching a soccer match … but I thought I was connected to the TV …’ (Participant 20, man) ‘… things began upsetting me … little things … there was a buzzing kind of a noise. Now, I don't know where that was coming from because I was trying to pull out everything to see … I … ended up in the hospital after that …’ (Participant 13, woman) ‘I thought my neighbour was going to kill me. … and I just sat there waiting throughout the night or two nights – waiting for him to come in … Then I'd be afraid to go out … Going around with a knife in my bag just in case … I just lost touch with reality really.’ (Participant 36, man) ‘I was doing strange things … I hadn't slept for a few nights and I was walking in my bare feet around the city for 2 or 3 days and … It finished with me throwing stones at cars.’ (Participant 30, man) |

| Feeling violated | ‘… suddenly a woman called [name] came into my room and then a few men followed her and they just dragged me …’ (Participant 40, man) ‘… I thought I locked the back door [home] but obviously I didn't and the next thing, they [assisted admission team] just all arrived in … I couldn't understand them coming into my house and the cheek of them and who did they think they were, thinking they could just come in and strap me into the trolley … and just take me away?’ (Participant 37, woman) ‘Well, I was going to work one night and the cops [police] picked me up and brought me into [police] station …’ (Participant 31, man) ‘They came to the door and they told me I had to go in and I told them I didn't want to go … The next day they came with the Guards [police] … I was going to close the door on the three nurses. But … one of the nurses put their foot inside the door … and the Guards came in then … I was angry as hell because I'm going into hospital again for no reason …… It's happened to me now maybe six or seven times.’ (Participant 15, man) ‘She [wife] called in the heavies [assisted admission team] … I kind of blamed her … Everyone was against me … I don't know if I want to be part of the family any more … I was railroaded out, brought in and I was violated … I was stigmatised … I want nobody to mention to meddle or mess in my life ever again.’ (Participant 9, man) |

| Being confined | ‘I was terrified of coming into the place [hospital] and not getting out’ (Participant 9, man) ‘I thought oh my God, this is awful … It [psychiatric unit] looked really old-fashioned and it just looked really dingy … and I saw one patient … walking around really slowly … with really dull eyes and I thought oh my God, what am I coming here into? That was scary seeing that … That was probably because of her medication but I didn't like that.’ (Participant 27, woman) ‘I mean there'd just be six, eight, ten [nurses] … it's not like a normal injection … they put you lying on the bed and then one of them sort of gets on top of you and … like they push your shoulders down.’ (Participant 17, woman) ‘I was there on the bed and two nurses came over, two male nurses. One had medication in his hand. He said I have medication for you to take … I've only just arrived … I don't want to take medication and the other guy said, well, we'll give you an injection then … that was fairly threatening.’ (Participant 21, man) |

| Regaining control | |

| Resisting the system | ‘Because of the aggression of the admission, the aggression in me wanted to fight … I was angry … I was just fighting back to prove to them that I'm all right. I didn't need this sort of intervention.’ (Participant 10, woman) ‘When I first went in I was adamant … I wasn't staying in here. This wasn't the place for me … And at the time I was like, oh Jesus, just let me out of this place … I think I tried to run off once.’ (Participant 4, woman) ‘They brought me over anyway … I was being forced into an area where there was no explanation or understanding of what was going through … I started screaming at them … I was feeling angry and upset, giving out to people when I got there first.’ (Participant 28, woman) |

| Encountering humanising care | ‘The Gardaí [Irish police] came, bought me a coffee … gave my bicycle a lift down to the Garda station.’ (Participant 36, man) ‘The Gardaí [Irish police] … it was “will you come down to the station? We'll just have a chat”.’ (Participant 38, man) ‘I can remember having a conversation with the Gardaí that night … We were talking about … hurling and loads of other stuff … making sure I had tea and something to eat … just something as basic as that.’ (Participant 38, man) ‘I was given this medication … I said that they're making me very tired … she changed them then …’ (Participant 19, man) ‘Nurses would … come and say “don't worry … you are okay” … Some [nurses] would really understand what's going on. Really understand who I was’ (Participant 28, woman) ‘I knew I could say to one of the guys [nurses] can you let me out for a walk? Once they got the trust with me … I could walk around the block or they brought in a hurl and a ball.’ (Participant 18, man) ‘… you'd come and go as you please … You'd just say to them [nurses] I'm going out now for an hour. They'd say … Yeah, you're grand [name] … I could go across to the shop … That was good … I was told that I could walk out any time … I had the freedom … it's really up to yourself’ (Participant 5, man) ‘I met Dr [name] … and I said I need to get out. My hair needed to be cut and I needed to get a few personal things done and she allowed me to do that … She gave me 3 hours out that day …’ (Participant 16, woman) ‘I was kept in and then I saw Dr [consultant psychiatrist] … she said “what's going on?” And she spoke to me and we both decided … I'd stay. So, she said we'll rip up this form … Keep you as voluntary.’ (Participant 1, woman) ‘I was still very frightened and I spoke with the doctor [names doctor who she knows] … he sort of brought me down a little bit. I felt a little bit at ease that people were being more normal and talking to me, asking me.’ (Participant 10, woman) ‘There was some staff that I got on with. I … felt they had my best interests at heart that they could see the person behind the patient … appreciated that I had a life outside of being a patient.’ (Participant 21, man) |

| Gaining perspective | ‘You're in a different mind state … to look back … I know now that they [professionals] were right [being subject to involuntary admission] but at the time … they were 100% wrong and now I think they were 100% right’ (Participant 1, woman) ‘… I was thinking differently than everyone else. I thought everyone was on my case … I just know I needed to get in here to get my head sorted out because it wasn't right outside … It was good for me like … Just having someone there to talk to. That's all.’ (Participant 10, man) ‘… it [memory] all started to come back … I started to remember everything and that obviously started to upset me … I really just felt totally deflated and at that stage I just said to myself I don't care how long I have to stay in here … what tablets I have to take … just once I get better basically …’ (Participant 1, woman) ‘She [nurse] was talking to me as though she believed what was going on in my thoughts … she understood where I was coming from … asking me questions that were trying to make me think introspectively.’ (Participant 38, man) ‘I was with [psychotherapist] and she was saying why did you have this thought? I thought my house had been robbed … and she said it's a strange thought. Why did you think it? Probably because I lost my keys in [place] … She said oh, well that was the explanation. It made sense then.’ (Participant 39, woman) ‘I understood the fact that they were admitting me for my own self really. They [professionals] thought I was going to take my life … I understood because of my alcoholism … It was … even clearer to me as I went along … I needed it … I think it was the biggest wake-up call … I'd probably still be drinking away …’ (Participant 4, woman) ‘… when I first came into hospital … I was slightly off the wall … So, as I say being in [names hospital], it was a turning point … I sort of finally came to terms with … I have been diagnosed with bipolar … I think … I understand my illnesses better.’ (Participant 11, woman) ‘When that occurred [police arrival] … it made me think there was something wrong … I also felt … more at peace with myself … from a safety perspective I felt that they would actually protect me from what was going on so the psychosis was still there … once the Guard (policeman) was there, I honestly … felt that I was going to be looked after now. I'd get the treatment.’ (Participant 38, man) |

| Playing ball | ‘I was kind of agreeing and nodding with everything just to get through … I'm thinking to myself … you … shut your mouth and go along with it … and hopefully get out fast … One of the patients said to me when I got in … you agree with everything. You say yes to everything, you toe the line or else.’ (Participant 9, man) ‘I just had to basically agree with them and say I will take whatever medication in order to be able to be let out … I had to say the right thing to everybody to get out, you know, of jail basically.’ (Participant 44, woman) ‘When I was sectioned I thought crap. The only way I was leaving here now was to take my medication … from then on I took it.’ (Participant 14, man) ‘Sometimes it feels hard because … even though they're [other patients] getting better they still feel crazy and they don't show it … they still have beliefs … I've heard other people saying that … when the doctor asked them were they still hearing the voices. In their head they'd say yeah, but then like they'd be saying no … Sometimes I say I'm better than I am … but sometimes … I'm not 100%, that's all … They [psychiatrists] just keep you in for longer … Unless you're right completely like, they just lock you up.’ (Participant 24, man) |

| Maintaining control | |

| Living with the consequences of involuntary admission | ‘It upset me so much. Knowing that my husband could hate me enough to sign me in … he didn't want me at home … He went to the doctor and … put me in hospital.’ (Participant 39, woman) ‘I cannot forget that [being signed in] very easily. I felt very betrayed by my wife … I can't trust her any more … Obviously it has affected my relationship … That made me a very disillusioned person.’ (Participant 47, man) ‘It [point of removal] was only 9 o'clock. There were people on the street … that seen all this happening which was … very embarrassing … people judge you as well on that actual admission or involuntary admission. There's a stigma with it no matter what anybody says.’ (Participant 10, woman) ‘People look at you differently when they realise where you've been … I felt that anyway … “she must have been very bad if she had to be signed in”. I'm really afraid to say anything to my husband … I don't give out about people … I think I couldn't start saying any of those things I was saying before that led me to be brought in … I couldn't express it in case he'd put me back in again.’ (Participant 44, woman) ‘It's changed my life [involuntary admission] … You're doubting your gut, doubting yourself constantly … All those thoughts … I didn't have them before … the reality of life as is so different from previous to this experience for me … it's changed my life … I don't feel like I'm good enough to be [name]'s mother now … It's very painful.’ (Participant 10, woman) |

| Managing mental health | ‘And seeing a doctor up there [day hospital] once a week or every second week. One of the nurses up there the other week … that was good. Somebody to check in and see how I was doing …’ (Participant 20, man) ‘… I talk to … an addiction counsellor and he helps me … it's as good as being in the hospital. You're still getting your medication. You still have nurses there for support.’ (Participant 7, woman) ‘… they [professionals] are trying to help … I can go talk to the [consultant psychiatrist] last Tuesday and [community mental health nurse] called out to my house and I speak to them … about the way I feel … I find it helpful to be honest with people …’ (Participant 10, woman) ‘… I was educated about what was necessary to keep myself on the right track and I try to follow that as strictly as possible … it keeps me going. It was also the out-patient visits and the conversations that I had with the doctors in the out-patients that really helped as well in educating me in terms of what been happening and what I should do to maintain a healthy kind of mind-set …’ (Participant 38, man) ‘… the therapy sessions are a huge bonus because if I get a bad day, or two days … the therapy sessions are brilliant … the anxiety and the mood, this stress and coping one … it's helping to … get yourself out of a situation …’ (Participant 6, man) ‘I'm seeing a psychologist at the moment to come to terms with the past and my diagnosis … Initially I saw one really just to get me back on my feet … that went a long way towards me accepting my diagnosis … since then I've been working on motivation …’ (Participant 41, man) ‘… a way I have dealt with a lot of things is to write things down … that for me has been very helpful, to write down my experiences … my emotions and my feelings and that's something you know I can look back on and understand …’ (Participant 10, woman) |

| Preserving sense of self | ‘Being brought in involuntary … it's much harder to explain being brought in involuntary than it is to be brought in of your own will … This makes it more difficult (to explain to others, so don't tell) … It sounds much better if you check yourself in … it sounds like you're in control. It sounds like you're not crazy. It sounds like you're sane. Involuntary sounds awful dramatic. It sounds like you've totally lost it.’ (Participant 41, man) ‘… Everything I say now, I monitor … Every time I have a conversation with the doctor or a psychiatrist or whatever, that it's been naturally analysed in one sense …’ (Participant 10, woman) ‘… I'm a very strong person so I'd be, well, feck it [reference to standing up to being judged]…there is that tendency oh, hide away … you have to be sort of brave and just go out there …’ (Participant 17, woman) ‘For me it's going to be getting back to [work]. That's going to validate me … you've got to get back your function and you've got to create your own story.’ (Participant 36, man) |

Funding

This study was funded by the Mental Health Commission: Research Programme Grants in Mental Health Research.

References

- 1.Office of the Attorney General. Mental Health Act 2001. Office of the Attorney General, 2001. (http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2001/act/25/enacted/en/print.html). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loft NO, Lavender T. Exploring compulsory admission experiences of adults with psychosis in the UK using grounded theory. J Ment Health 2016; 25: 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seed T, Fox J, Berry K. Experience of detention under the mental health treatment Act for adults with anorexia nervosa. Clin Psychol Psychother 2016; 23: 352–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research, Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy R, McGuinness D, Bainbridge E, Brosnan L, Felzmann H, Keys M, et al. Service users’ experiences of involuntary admission under the Mental Health Act 2001 in the Republic of Ireland. Psychiatr Serv 2017; 68: 1127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bainbridge E, Hallahan B, McGuinness D, Gunning P, Keys M, Felzmann H, et al. Predictors of involuntary patients' satisfaction with care: a prospective follow-up study. BJPsych Open, this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (4th edn) (DSM-IV). APA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott FN, Lazenbatt A. How to recognize a ‘quality’ grounded theory research study. Aust J Adv Nurs 2005; 22: 48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glaser BG. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Sociology Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsakou C, Priebe S. Patient's experiences of involuntary hospital admission and treatment: a review of qualitative studies. Epidemiol Pschiatr Soc 2007; 16: 172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsakou C, Rose D, Amos T, Bowers L, McCabe R, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric patient's view on why their hospitalization was right or wrong: a qualitative study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012; 47: 1169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambers M, Gallagher A, Borschmann R, Gillard S, Turner K, Kantaris X, et al. The experiences of detained mental health service users: issues of dignity in care. BMC Med Ethics 2014; 15: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry 2011; 199: 445–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Jong MH, Kamperman AM, Oorschot M, Priebe S, Bramer W, van de Sande R, et al. Interventions to reduce compulsory psychiatric admissions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73: 657–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGuinness D, Dowling M, Trimble T. Experiences of involuntary admission in an approved mental health centre. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2013; 20: 726–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keogh B, Callaghan P, Higgins A. Managing preconceived expectations: mental health service user's experiences of going home from hospital: a grounded theory study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2015; 22: 715–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Donoghue B, Lyne J, Hill M, O'Rourke L, Daly S, Larkin C, et al. Perceptions of involuntary admission and risk of subsequent readmission at one-year follow-up: The influence of insight and recovery style. J Ment Health 2011; 20: 249–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]