INTRODUCTION

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a leading cause of disability worldwide, affecting 14 million Americans.1 Obesity is a major risk factor for developing KOA, and about 85% of those with KOA are overweight or obese.2 It is hypothesized that both increased biomechanical loading and systemic inflammatory activity associated with obesity accelerate the development and progression of KOA.3 Obesity is furthermore associated with worse joint pain.4 In persons with knee pain who are morbidly obese, defined as body mass index (BMI) exceeding 35 kg/m2, weight loss is associated with improvements in pain, physical function, and quality of life.5,6

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an effective surgical option for end-stage KOA; however, morbidly obese persons present with complication profiles that may outweigh the functional benefits gained.7 For persons with BMI greater than 40 kg/m2, the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (AAHKS) recommends weight loss to below that threshold prior to undergoing TKA.7

Bariatric surgery is the most effective method for losing weight and maintaining weight loss.8 It is also associated with positive changes in radiographic findings seen in early KOA,9 reductions in levels of inflammatory markers linked with OA progression,10 and reductions in the prevalence and incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.11,12 Bariatric surgery techniques can employ restrictive and malabsorptive features. Restrictive techniques, such as laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (laparoscopic banding) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, decrease the size of the stomach thereby limiting food consumption,13 while biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) combine restriction and malabsorption to reroute the gastrointestinal tract and decrease nutrient absorption in the small intestine.14 These procedures are associated with varying amounts of initial and maintained weight loss; on average, malabsorption techniques result in greater weight loss than restrictive procedures, but are also associated with higher complication rates.12,15,16

Over the past few decades, inpatient morbidity and mortality following bariatric surgery have improved dramatically.17 Although there have been bariatric surgical advances and increasing evidence pointing to positive associations between weight loss and knee pain and functional improvements, treating morbidly obese persons with KOA is challenging. Bariatric surgery may be considered as a treatment for not only long-term weight loss, but also OA symptoms for certain morbidly obese persons with KOA. Approximately 115,000 bariatric surgery procedures are performed in the US every year.18 The utilization of bariatric procedures among persons with KOA has not yet been evaluated. Using data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2005 to 2014, we sought to assess trends in the utilization and inpatient outcomes of bariatric operations among morbidly obese persons with KOA.

METHODS

Data source

We abstracted discharge data from the National Impatient Sample (NIS), the largest all-payer inpatient database in the United States,19 between 2005 and 2014. The database was developed by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) and is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). It contains data from 44 states and the District of Columbia, representing a 20% stratified sample of all discharges from US hospitals. Its sampling frame covers more than 96% of the population.19 The database provides information on demographics, comorbidities, diagnoses, total hospital charges, length of stay (LOS), and mortality.19 The NIS has previously been used by investigators to evaluate the volume of and inpatient outcomes associated with bariatric surgery.18,20

Patient selection

We used ICD-9-CM codes to identify persons with KOA who underwent bariatric procedures. We excluded discharges with age <18 years old because KOA is an age-related condition and the prevalence of OA is very low in children. To identify our study sample, we included observations with diagnosis codes for both KOA (715.x6) and obesity (278.00, 278.01, 278.03, and 278.1) as well as a primary procedure code for laparoscopic banding (44.95), laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (43.82), open RYGB (44.31, 44.39), laparoscopic RYGB (44.38), or BPD/DS (45.91, 45.51, 43.89). The primary procedures captured were planned admissions for each specific procedure type; we did not include conversions from laparoscopic to open procedures due to complications. We did not evaluate laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy before 2010 because no ICD-9 code existed prior to then and the procedure was inconsistently coded across hospitals.21

Data elements, outcomes, and definitions

Hospital characteristics

We abstracted hospital information to determine the developed environment type and teaching status (rural, urban teaching, and urban non-teaching) as categorized by the NIS. We also abstracted the bed size for each hospital; the NIS designates each hospital as small, medium, or large bed size with thresholds for each category based on the region, location, and teaching status of the hospital.22

Demographic and clinical characteristics

We abstracted demographic information such as age, sex, race, and payer for each discharge under consideration. Using variables coded in the NIS, we abstracted information on diabetes and hypertension. For each discharge, we calculated the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, a comorbidity metric designed for use with large administrative datasets using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes.23 The Index measures a comprehensive set of 30 comorbidities, all of which were associated with increased resource use, LOS, and mortality.23 For each individual admission, we calculated the Elixhauser Index by assessing the presence of each comorbidity using the ICD-9-CM codes reported in the diagnoses data element variables of the NIS.24 We excluded weight loss and obesity in the calculation because all in the sample were morbidly obese.24

Inpatient surgical outcomes

We abstracted the inpatient mortality status variable and examined in-hospital complications using ICD-9-CM codes. We captured data pertaining to infections, wounds, and pneumonia, as well as urinary and renal, other pulmonary, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and overall systemic complications (Appendix 1).24

Length of stay and procedure costs

For each discharge, we abstracted the LOS variable from the NTS. To calculate hospital costs, we multiplied the charge for each admission by the hospital-specific, all-payer cost-to-charge ratio (CCR) for the appropriate year.25 When this information was unavailable, we estimated appropriate costs using the group average all-payer CCR,25 which represents the weighted average for hospitals in the group defined by its urban or rural status, bed size, ownership status, and state.25 We updated and reported all costs in 2017USD using the Personal Health Care (PHC) Index and the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) Index.26 Prices in the healthcare sector have increased at a faster rate than the rest of the economy;27 thus, the PHC coupled with the PCE has been found to produce the most accurate results in cost adjustment.28

Statistical analysis

For each procedure under consideration, we calculated descriptive hospital, demographic, and clinical characteristics, as well as inpatient complication and mortality outcomes on a bi-annual basis for the entire cohort of bariatric patients with KOA. Using hospital weight strata provided as part of the NIS database, we estimated the national volumes of each procedure type in two-year intervals, adjusted for age, sex, Elixhauser Index, hospital location and teaching status, hospital bed size, and procedure type. We used linear regression to evaluate the trend in the overall national volume of KOA patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

We calculated LOS and costs stratified by procedure and calendar period. We present descriptive data for continuous variables as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) and categorical or binary variables as percentages. We built initial logistic regression models for the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension adjusting for age and sex, and we built linear regression models for LOS and total hospital costs adjusting for age, sex, Elixhauser Index, hospital setting, and bed size. We also adjusted total hospital costs for LOS because costs are heavily impacted by the LOS. The choice of the variables included in the model was guided by bivariate analyses. A covariate was included if it was associated with outcome. From the results of each initial model, covariates that had significant impact (p-value<0.05) were included in the final model.

We modeled temporal trends in continuous variables using linear regression and in proportions using the two-sided Cochran-Armitage temporal trend test. We set statistical significance at a p-value of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For the final analysis, procedure types with an estimated ≤500 database observations over the 10-year period were excluded because trend estimates for small sample sizes are not stable.

RESULTS

Hospital characteristics

The proportion of procedures performed in urban teaching hospitals increased from 55% in 2005-2006 to 74% in 2013-2014, and the proportion performed in urban non-teaching hospitals decreased from 41% to 24% in that same period. Neither trend reached statistical significance (p=0.08 and 0.10, respectively; Table 1). Only about 3% of bariatric procedures were performed in rural hospitals, with no changes in trend. In rural settings, there was a shift from predominantly planned open RYGB (57%) in 2005-2006 to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (50%) in 2013-2014. In urban settings, there was a shift from predominantly laparoscopic RYGB in 2005-2006 to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in 2014-2015.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics and clinical characteristics, surgical outcomes, and hospital characteristics.

| Overall | 2005-2006 | 2007-2008 | 2009-2010 | 2011-2012 | 2013-2014 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||||

| % Female | 79.4% | 79.8% | 79.6% | 80.9% | 78.8% | 77.9% | 0.1667* |

| % White | 62.4% | 59.6% | 62.6% | 63.2% | 64.5% | 62.2% | 0.0953* |

| % Medicare | 15.8% | 7.1% | 11.0% | 18.2% | 19.9% | 23.3% | <0.0001* |

| Age, Median (IQR) | 49 (41-57) | 46 (38-54) | 48 (40-55) | 50 (41-57) | 50 (41-57) | 51 (43-58) | 0.0138† |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||||

| % Diabetes‡ | 30.2% | 27.5% | 27.0% | 29.2% | 29.6% | 32.4% | 0.0261* |

| % Hypertension‡ | 61.4% | 58.8% | 62.1% | 64.2% | 63.4% | 64.7% | 0.0506* |

| Elixhauser Index, Median (IQR)‡ | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | - |

| Elixhauser Index, Mean (SD)‡ | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.2) | 2.0 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.3) | <0.0001† |

| Surgical Outcomes | |||||||

| % Death | 0.06% | 0.07% | 0.08% | 0.08% | 0.08% | 0.00% | 0.4974* |

| Complication Rates | |||||||

| % Any Early Complication§ | 3.20% | 5.24% | 3.46% | 3.66% | 2.09% | 1.68% | <0.0001* |

| Infection | 0.24% | 0.36% | 0.45% | 0.16% | 0.24% | 0.00% | 0.0259* |

| Wound Complication | 0.32% | 0.36% | 0.15% | 0.48% | 0.40% | 0.22% | 0.9136* |

| Urinary/Renal | 0.24% | 0.36% | 0.23% | 0.40% | 0.16% | 0.07% | 0.1258* |

| Pneumonia | 0.38% | 0.58% | 0.08% | 0.64% | 0.24% | 0.36% | 0.6096* |

| Other Pulmonary | 0.68% | 1.96% | 0.83% | 0.40% | 0.16% | 0.00% | <0.0001* |

| Gastrointestinal | 0.61% | 0.87% | 0.90% | 1.03% | 0.24% | 0.00% | 0.0003* |

| Other Cardiovascular | 0.87% | 0.87% | 0.90% | 0.87% | 0.64% | 1.02% | 0.9424* |

| Systemic Complication | 0.20% | 0.58% | 0.30% | 0.00% | 0.08% | 0.00% | 0.0003* |

| Setting | |||||||

| % Rural | 3.1% | 3.1% | 3.1% | 5.3% | 2.1% | 2.2% | 0.3361† |

| % Urban Non-Teaching | 36.7% | 41.5% | 36.6% | 43.0% | 39.1% | 24.0% | 0.0980† |

| % Urban Teaching | 60.2% | 55.5% | 60.3% | 51.7% | 58.8% | 73.9% | 0.0758† |

| Bed Sizeǁ | |||||||

| % Small | 16.7% | 14.8% | 10.5% | 18.0% | 19.5% | 20.9% | 0.0370† |

| % Medium | 26.2% | 23.1% | 27.7% | 24.1% | 27.3% | 28.6% | 0.1457† |

| % Large | 57.1% | 62.1% | 61.8% | 57.9% | 53.2% | 50.5% | 0.0003† |

IQR: Interquartile Range

P-values obtained from:

Cochran-Armitage test for trend

Linear regression

Prevalence, mean, and median values adjusted for age

Prevalence values adjusted for age, procedure, and bed size of the hospital

Categories are based on the number of hospital beds. Each hospital’s category is determined by its locational region and teaching status. Bed size assesses the number of short-term acute care beds set up and staffed in a hospital.

The proportion of procedures performed in large hospitals decreased from 62% in 2005-2006 to 50% in 2013-2014 (p<0.0005; Table 1); there was an increase in the number of procedures performed in both small (15% to 21%, p=0.04) and medium-size (23% to 29%, p=0.15) hospitals. Hospitals with small bed sizes were more likely to perform open RYGB procedures in 2005-2006 (34% of procedures were performed in small-bed hospitals versus 22% and 20% in medium- and large-bed hospitals, respectively), but this decreased in 2013-2014 (0.7% in small-bed hospitals compared to 4.3% and 1.3% in medium- and large-bed hospitals, respectively).

Distribution of volume by procedure type over time in persons with KOA

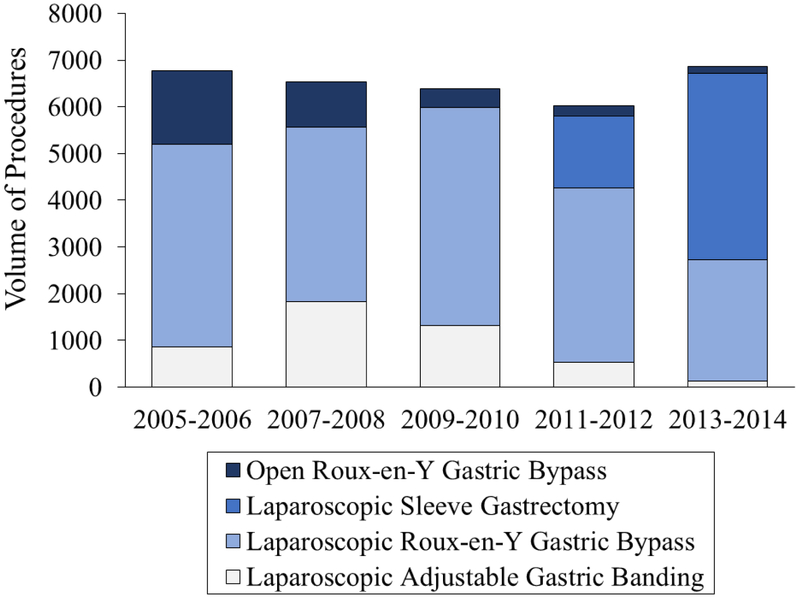

After adjusting for clinical and demographic characteristics, an estimated national total of 32,581 (95% CI: 29,353 – 35,808) laparoscopic and open RYGB, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, and laparoscopic banding procedures were performed on persons with KOA from 2005 to 2014. The annual utilization of any bariatric procedure in adults with KOA plateaued over the decade (p=0.80), staying consistent at a rate of about 23.3 bariatric procedures per 100,000 adults. We report the number of observations in the NIS by procedure per period in Appendix 2 and include the estimates found for each procedure in Appendix 3. BPD/DS procedures were excluded from the analysis because there were only 419 observations over the decade of interest. Planned laparoscopic RYGB was the predominant procedure performed in 2005-2006 (65%) whereas laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy was the most commonly performed procedure (58%) in 2013–2014 (Figure 1). Whereas the proportion of laparoscopic banding and laparoscopic RYGB performed remained consistent over time (p-trend 0.23 and 0.19, respectively), the national volume of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy performed in persons with KOA increased from 1,539 procedures in 2011-2012 to 3,995 procedures in 2013-2014. During this same time frame, the number of open RYGB procedures performed in persons with concomitant KOA decreased significantly from 1,577 procedures in 2005-2006 to 140 procedures in 2013-2014 (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Utilization of bariatric surgery among morbidly obese adults with knee osteoarthritis, by surgery type, between 2005 and 2014, adjusted for clinical and demographic characteristics (age, sex, Elixhauser Index, hospital location and teaching status, hospital bed size, and procedure type). The bars represent the estimated volume of each type of bariatric surgery procedure, calculated by multiplying each observation in the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) by the hospital-specific weight strata provided in the database for the observation. Overall, NIS provides a 20% stratification of all US hospitals.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Between 2005 and 2014, the age of persons with KOA who underwent bariatric surgery ranged from 18 to 78 years, with a median (IQR) of 49 (41-57) years (Table 1). Over time, the median (IQR) age increased from 46 (38-54) to 51 (43-58) years (p=0.01; Table 1). For all individual procedures types, the median age of patients increased; between 2005-2006 and 2013-2014, the median age of those undergoing laparoscopic banding increased from 48 to 51, laparoscopic RYGB from 46 to 51, and open RYGB from 46 to 50.5. For those undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, the median age increased from 49 to 51 between 2011-2012 and 2013-2014.

Most KOA patients undergoing bariatric surgery were women, which remained consistent over the decade (~79%) and across individual procedure types. Overall, the proportion of white patients increased from 60% in 2005-2006 to 62% in 2013-2014 (p=0.10; Table 1). The percentage of patients with Medicare as the primary payer increased from 7% to 23% (p<0.0001; Table 1). A higher proportion undergoing laparoscopic banding paid with Medicare (22%) than those undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (16%), laparoscopic RYGB (15%), and open RYGB (12%).

We found that age and sex contributed significantly to the initial logistic regression models of diabetes and hypertension prevalence; thus, both remained in the final models for both comorbid conditions. The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of diabetes increased from 27% in 2005-2006 to 32% in 2013-2014 (p=0.03; Table 1). The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of hypertension increased from 59% in 2005-2006 to 65% in 2013-2014 (p=0.05; Table 1). The mean Elixhauser Comorbidity Index among KOA patients undergoing bariatric surgery rose from 1.6 to 2.0 (p<0.0001; Table 1), whereas the median Elixhauser Index remained consistent at 2 throughout the period of interest (Table 2).

Table 2.

Age, Elixhauser Index, and length of stay by surgery type.

| Lap. Band | Lap. RYGB | Lap. Sleeve | Open RYGB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 51 (42-59) | 48 (40-56) | 50 (42-57) | 47 (39-55) |

| Elixhauser Index | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) |

| Length of Stay* | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 2.3 (2.2-2.4) | 1.9 (1.8-2.0) | 3.3 (3.2-3.4) |

| Cost† | $10,319 ($9,542-$11,296) |

$14,448 ($13,224-$15,851) |

$12,281 ($11,250-$13,480) |

$14,729 ($13,156-$16,918) |

All values reported are median (interquartile range)

Lap Band: Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band

Lap Sleeve: Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

RYGB: Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

Means adjusted for age, procedure type, location and teaching status of the hospital, and Elixhauser Index

Means adjusted for sex, length of stay, procedure type, bed size of the hospital, location and teaching status of the hospital, and Elixhauser Index

Inpatient surgical outcomes

The annual inpatient mortality rate was between 0.0% and 0.1% overall and did not change significantly over time (p=0.50; Table 1). There were no reported inpatient deaths following laparoscopic band or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; 0.1% of planned laparoscopic RYGB resulted in inpatient death, and 0.2% of open RYGB resulted in inpatient death.

We found that age, procedure type, and bed size of the hospital contributed significantly to the logistic regression model of inpatient complication rate and adjusted the total complication rates by those variables in the final model. The adjusted proportion of all bariatric subjects who experienced any inpatient complication decreased from 4.3% in 2005-2006 to 1.5% in 2013-2014 (p=0.0004; Table 1). When evaluating complication rates by procedure, persons undergoing open RYGB experienced the highest incidence of age-adjusted complications (5.6%), and persons undergoing laparoscopic banding experienced the lowest incidence (1.0%). Persons undergoing laparoscopic RYGB and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy experienced adjusted complication incidences of 3.0% and 2.3%, respectively.

Overall, the risk of specific complications was low. Wounds, urinary and renal-related, pneumonia, and cardiac-related complications were unchanged through the decade and the mean incidence rate by complication type was 0.3%, 0.2%, 0.4%, and 0.9%, respectively. The incidence of inpatient infection, non-pneumonia pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and systemic complications all decreased significantly between 2005-2006 and 2013-2014, from 0.4% to 0% (p=0.03), 2.0% to 0% (p<0.0001), 0.9% to 0% (p=0.0003), and 0.6% to 0% (p=0.0003), respectively.

Length of stay and procedure costs

For LOS of each surgical type, we found that age, procedure type, location and teaching status of the hospital, and Elixhauser Index contributed significantly to the linear regression model and used those as adjustment variables in the final model. Overall, the median (IQR) adjusted LOS decreased from 2.3 (2.2-2.4) to 2.0 (1.9-2.3) days (p=0.08; Table 3). Those who received open RYGB had the longest median adjusted LOS (3.3 days, IQR: 3.2-3.4), whereas those who underwent laparoscopic banding had the shortest median LOS (1.2 days, IQR: 1.1-1.3) (Table 2). The median LOS for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic RYGB was 1.9 (IQR: 1.8-2.0) and 2.3 (IQR: 2.2-2.4) days, respectively. The median adjusted LOS for laparoscopic RYGB increased significantly from 2005-2014, from 2.25 to 2.33 (p<0.01; Table 3). The median adjusted LOS for laparoscopic banding and planned open RYGB did not significantly change over the decade.

Table 3.

Median (interquartile range) length of stay, adjusted for age, hospital location and teaching status, and Elixhauser Index, by surgery type.

| 2005-2006 | 2007-2008 | 2009-2010 | 2011-2012 | 2013-2014 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lap. Band | 1.17 (1.10-1.27) | 1.18 (1.10-1.28) | 1.22 (1.12-1.31) | 1.27 (1.15-1.35) | 1.24 (1.13-1.31) | 0.0525 |

| Lap. RYGB | 2.25 (2.17-2.34) | 2.28 (2.19-2.37) | 2.31 (2.21-2.40) | 2.31 (2.20-2.40) | 2.33 (2.23-2.43) | 0.0097 |

| Lap. Sleeve | - | - | - | 1.87 (1.78-1.95) | 1.90 (1.81-2.00) | - |

| Open RYGB | 3.30 (3.21-3.38) | 3.30 (3.22-3.40) | 3.36 (3.27-3.43) | 3.29 (3.17-3.42) | 3.32 (3.25-3.41) | 0.7848 |

| All Surgeries | 2.28 (2.15-2.44) | 2.24 (1.35-2.40) | 2.27 (2.09-2.40) | 2.20 (1.92-2.37) | 2.02 (1.86-2.28) | 0.0804 |

Lap. Band: Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band

Lap. Sleeve: Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

RYGB: Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

P-value obtained from linear regression model

For the costs of each surgical type, we found that the LOS, sex, procedure type, bed size of the hospital, location and teaching status of the hospital, and Elixhauser Index contributed significantly to the linear regression model; we included these covariates in the final model. The adjusted median costs for each procedure per period, standardized to 2017USD, are tabulated in Table 4. The overall median adjusted costs for laparoscopic banding, laparoscopic RYGB, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, and open RYGB were $10,300, $14,400, $12,300, and $14,700, respectively (Table 2). The median adjusted costs of laparoscopic and open RYGB decreased significantly from $15,100 in 2005-2006 to $13,700 in 2013-2014 (p<0.01) and $15,400 to $11,900 (p=0.02), respectively, whereas the costs of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic banding did not change significantly over time (Table 4). Among the 6,582 observations included in this analysis, 2.3% of the discharges did not include charge data and were excluded from the cost analyses.

Table 4.

Median costs per year, in 2017 USD and adjusted for sex, length of stay, hospital bed size, hospital location and teaching status, and Elixhauser Index. Costs are tabulated for each type of bariatric surgery for a cohort of morbidly obese osteoarthritis patients.

| 2005-2006 | 2007-2008 | 2009-2010 | 2011-2012 | 2013-2014 | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lap. Band | $10,546 | $10,537 | $10,165 | $10,319 | $9,511 | 0.0672 |

| Lap. RYGB | $15,117 | $14,769 | $14,448 | $14,017 | $13,302 | 0.0023 |

| Lap. Sleeve | - | - | - | $12,785 | $12,055 | - |

| Open RYGB | $15,363 | $14,450 | $14,681 | $12,943 | $11,876 | 0.0155 |

| All Surgeries | $14,792 | $14,006 | $13,907 | $13,400 | $12,380 | 0.0076 |

Lap Band: Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band

Lap Sleeve: Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

RYGB: Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

P-values obtained from linear regression model

DISCUSSION

We used the NIS administrative database to evaluate the utilization of bariatric operations and to assess the clinical, demographic, and post-operative profiles of morbidly obese persons with KOA between 2005 and 2014. We found that the volume of bariatric surgery utilization among this population has plateaued over the last decade at about 3,300 procedures performed annually, and that the number and proportion of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy procedures performed have been increasing since 2011. The utilization rate of bariatric surgery, about 23.3 procedures per 100,000 persons with KOA, is lower than that of the general population in the US, which has been reported to be about 47.3 procedures per 100,000 adults.18

These results are comparable to other studies that found a plateau in the number of bariatric procedures in the US population between 2008-2012.18,20 Prior to 2005, the utilization of bariatric surgery in the US had been steadily rising.29,30 This recent plateau may be attributed to the centralization of bariatric procedures following the development of Centers of Excellence (COE), which required hospitals to perform at least 125 bariatric operations per year.31 In 2006, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and other insurers began covering only procedures performed at COE institutions, citing improved quality and patient safety associated with higher-volume centers.32 These policies are reflected in our results on hospital setting distribution trends among persons with KOA receiving bariatric surgery. From 2005-2014, we found that a significantly higher percentage of procedures were performed in urban teaching hospitals (55% to 74%).

Since 2006, there has been contradictory evidence for whether the mandatory COE designation limits access to care. 31, 33-35 In 2013, after CMS found increasing evidence indicating that there may be no difference in surgical outcomes between procedures performed at COE and non-COE facilities, the 2006 policy was overturned. Since 2013, bariatric surgery has been covered at institutions that are not COE-certified.36 With this new policy, there may be a rise in the utilization of bariatric surgery among Medicare patients over the next decade due to the removal of barriers that affected access to care.

The plateau in bariatric surgery utilization among persons with KOA may also be due to barriers facilitated by both patient and provider concerns. In a survey study of primary care providers, only 12% were satisfied with non-surgical interventions for their morbidly obese patients, yet 30% were not comfortable discussing surgical treatment options and less than half were not confident in providing post-operative management.37 Patient concerns include cost, lack of knowledge about the procedures, and safety;38 however, they are more likely to pursue bariatric surgery if it is recommended by referring physicians.38 More education on the benefits, outcomes, and post-operative management of bariatric surgery may result in an increase in the likelihood of provider referral and patient utilization.

The median age of this analysis sample, 49 years, is about 4 years older than that previously reported for the general bariatric population.18,20 This may explain why the estimated utilization rate of bariatric surgery in persons with KOA is lower than that in the general population; older adults may be less willing to undergo bariatric surgery. Whereas KOA primarily affects older adults, KOA patients undergoing bariatric surgery are younger than persons diagnosed with KOA, who are 53.5 years old, on average.39 We report a significant increase in the median age of persons with KOA undergoing bariatric surgery from 2005-2014, which may be due to the CMS decision in 2006 to cover laparoscopic banding, laparoscopic RYGB, and open RYGB.32 This is also reflected in our finding of a significant increase in the proportion of Medicare patients from 2005-2006, when 7% were covered by Medicare, to 2013-2014, when 23% were covered by Medicare. We also found an increase in the Elixhauser Index as well as prevalence of diabetes and hypertension among this sample in the decade of interest. However, despite a set of older and more complex patients, incident inpatient death remained low at 0.0-0.1% and the inpatient complication rate decreased from 5.2% to 1.7% (p<0.0001). Bariatric surgery has been found to be associated with low mortality and complication rates,40,41 and these data emphasize that bariatric surgery is generally safe for morbidly obese persons with KOA.

Administrative databases, such as NIS, offer large amounts of data on a large volume of subjects. However, these datasets have limitations and constraints, including accuracy and completeness of data. There may be omissions in coding for KOA, especially among complex patients with multiple comorbidities as many bariatric patients have. Therefore, our estimates on procedure volume in persons with KOA are likely conservative. Importantly, the NIS does not capture readmissions and post-discharge outcomes, which restricts data to inpatient outcomes and likely results in underestimation of morbidity and mortality. We estimate inpatient mortality at 0.0-0.1%; large cohort studies of bariatric surgery patients report slightly higher results of about 0.3% mortality in 30 days and 0.4% mortality within one year.40,41 Additionally, due to a small number of observations for BPD/DS procedures performed on persons with KOA, we could not obtain accurate estimates or trend information for the outcomes of this two-staged procedure. Finally, because we did not have accurate data on the estimates of morbidly obese persons with KOA over time, we were unable to determine trends in the utilization rate of this population.

Whereas KOA has been historically thought to be caused by mechanical stress on the joint,42 recent evidence has shown that OA development is multifaceted, with inflammation as a central component of disease progression.43,44 Obesity is a potent risk factor for developing KOA; excess body weight not only increases mechanical loading on the knee, but is also associated with metabolic inflammation that contributes to sustained production of systemic pro-inflammatory mediators.43,44 The most effective intervention for KOA is TKA; however, despite having worse functional levels and higher pain than those who are non-obese, TKA is not an option for many who are morbidly obese due to high risks of surgical complications.7 Further, for morbidly obese persons who do undergo TKA, functional results are poorer and revision rates are higher compared to those who are non-obese.7,45

Morbidly obese persons considering TKA are advised to lose weight prior to surgery to reduce risk of complications. Bariatric surgery may be considered in these situations as a means of long term weight reduction. However, the evidence that bariatric surgery may reduce the symptoms associated with KOA and the limitations to undergoing TKA is inconclusive, perhaps due to differences the populations sampled in each study. Positive evidence in favor of bariatric surgery includes a study revealing that subjects undergoing TKA prior to bariatric surgery had significantly higher complication and revision rates and longer anesthesia, operation, and tourniquet times compared to subjects undergoing TKA more than two years after bariatric surgery.46 In another study, subjects undergoing bariatric surgery prior to hip or knee arthroplasty had 3.5 times lower wound infections and 7 times lower readmission rates compared with subjects who first underwent joint arthroplasty.47 Other studies have found that bariatric surgery prior to joint replacement does not offer significantly lower readmission, reoperation, or incident complication rates and may worsen outcomes compared to those who have not undergone bariatric surgery.48,49 Further, weight loss may not be positively associated with better surgical outcomes; one study found no significant difference in the risk of surgical site infections and readmissions in patients who had lost at least 5% of their body weight, through surgical and non-surgical treatments, prior to undergoing TKA compared to patients who had not lost weight pre-TKA.50 These studies highlight the challenges associated with treating persons with KOA who are morbidly obese. Bariatric surgery may not be the correct approach for all; individual factors such as the ability to undergo lifestyle changes including strict diet and exercise adherence, the timing of both the bariatric procedure and the OA diagnosis, and the patient’s lifetime history of obesity all factor into the success of the post-surgical outcomes.

Despite some evidence suggesting that bariatric surgery is efficacious in improving OA symptoms and TKA outcomes,5,9,10,46,47 more research is needed to better understand who among those with KOA and morbid obesity should be recommended to consider bariatric surgery. Ultimately, bariatric surgery is a procedure that has shown to be highly efficacious for weight loss for many in the general morbidly obese population6,11 and has the potential to improve pain, function, and TKA outcomes in persons with KOA.5,9,10,46,47

Supplementary Material

Data Statement.

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) is an inpatient administrative database developed by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) and supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The dataset can be purchased from the HCUP website. The parameters used in the manuscript and the methods of selection can be found in the Methods section of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Supported by: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS): R01AR064320, K24AR057827, and P30AR072577. The funding organization had no role in study design or conduct, data collection, analysis or interpretation of data, preparation or review of the manuscript, or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interest statement: Dr. Losina is a Deputy Editor for Methodology and Biostatistics for the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery and is a consultant for Samumed, LLC. All other authors indicate no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deshpande BR, Katz JN, Solomon DH, Yelin EH, Hunter DJ, Messier SP, et al. Number of Persons With Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis in the US: Impact of Race and Ethnicity, Age, Sex, and Obesity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016; 68: 1743–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niu J, Zhang YQ, Torner J, Nevitt M, Lewis CE, Aliabadi P, et al. Is obesity a risk factor for progressive radiographic knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thijssen E, van Caam A, van der Kraan PM. Obesity and osteoarthritis, more than just wear and tear: pivotal roles for inflamed adipose tissue and dyslipidaemia in obesity-induced osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54: 588–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen RE, Crespo CJ, Bartlett SJ, Bathon JM, Fontaine KR. Relationship between body weight gain and significant knee, hip, and back pain in older Americans. Obes Res 2003; 11: 1159–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards C, Rogers A, Lynch S, Pylawka T, Silvis M, Chinchilli V, et al. The effects of bariatric surgery weight loss on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis 2012; 2012: 504189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King WC, Chen JY, Belle SH, Courcoulas AP, Dakin GF, Elder KA, et al. Change in Pain and Physical Function Following Bariatric Surgery for Severe Obesity. JAMA 2016; 315: 1362–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Workgroup of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Evidence Based Committee. Obesity and total joint arthroplasty: a literature based review. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28: 714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pories WJ. Bariatric surgery: risks and rewards. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: S89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu-Abeid S, Wishnitzer N, Szold A, Liebergall M, Manor O. The influence of surgically-induced weight loss on the knee joint. Obes Surg 2005; 15: 1437–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richette P, Poitou C, Garnero P, Vicaut E, Bouillot JL, Lacorte JM, et al. Benefits of massive weight loss on symptoms, systemic inflammation and cartilage turnover in obese patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70: 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purnell JQ, Selzer F, Wahed AS, Pender J, Pories W, Pomp A, et al. Type 2 Diabetes Remission Rates After Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass and Gastric Banding: Results of the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery Study. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 1101–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, Berk P, Flum DR, Garcia L, et al. Seven-Year Weight Trajectories and Health Outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004; 292: 1724–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchwald H The evolution of metabolic/bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2014; 24: 1126–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, Vetter D, Kroll D, Borbely Y, et al. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss in Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SM-BOSS Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2018; 319: 255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salminen P, Helmio M, Ovaska J, Juuti A, Leivonen M, Peromaa-Haavisto P, et al. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss at 5 Years Among Patients With Morbid Obesity: The SLEEVEPASS Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2018; 319: 241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young MT, Jafari MD, Gebhart A, Phelan MJ, Nguyen NT. A decade analysis of trends and outcomes of bariatric surgery in Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Coll Surg 2014; 219: 480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen NT, Vu S, Kim E, Bodunova N, Phelan MJ. Trends in utilization of bariatric surgery, 2009-2012. Surg Endosc 2016; 30: 2723–2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Overview of the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS). In. <https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp> Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 20.Khan S, Rock K, Baskara A, Qu W, Nazzal M, Ortiz J. Trends in bariatric surgery from 2008 to 2012. Am J Surg 2016; 211: 1041–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, Ko CY, Cohen ME, Merkow RP, et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg 2011; 254: 410–420; discussion 420-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Notes: HOSP_BEDSIZE - Bedsize of hospital. In: 2008. <https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/vars/hosp_bedsize/nisnote.jsp> Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 23.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998; 36: 8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin JH, Worni M, Castleberry AW, Pietrobon R, Omotosho PA, Silberberg M, et al. The application of comorbidity indices to predict early postoperative outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a nationwide comparative analysis of over 70,000 cases. Obes Surg 2013; 23: 638–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratio Files In: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Ed. Rockville, MD: <https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/costtocharge.jsp> Accessed April 4, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Personal Health Care Expenditures Index September 2017 United States Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C.,. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin AB, Hartman M, Washington B, Catlin A. National Health Spending: Faster Growth In 2015 As Coverage Expands And Utilization Increases. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017; 36: 166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunn A, Grosse SD, Zuvekas SH. Adjusting Health Expenditures for Inflation: A Review of Measures for Health Services Research in the United States. Health Serv Res 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trus TL, Pope GD, Finlayson SR. National trends in utilization and outcomes of bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc 2005; 19: 616–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen NT, Masoomi H, Magno CP, Nguyen XM, Laugenour K, Lane J. Trends in use of bariatric surgery, 2003-2008. J Am Coll Surg 2011; 213: 261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livingston EH. Bariatric surgery outcomes at designated centers of excellence vs nondesignated programs. Arch Surg 2009; 144: 319–325; discussion 325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Bariatric Surgery for the Treatment of Morbid Obesity (CAG-00250R). In: 2006. <https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=160&ver=32&NcaName=Bariatric+Surgery+for+the+Treatment+of+Morbid+Obesity+(1st+Recon)&bc=BEAAAAAAEAgA> Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 33.Nicholas LH, Dimick JB. Bariatric surgery in minority patients before and after implementation of a centers of excellence program. Jama 2013; 310: 1399–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bae J, Shade J, Abraham A, Abraham B, Peterson L, Schneider EB, et al. Effect of Mandatory Centers of Excellence Designation on Demographic Characteristics of Patients Who Undergo Bariatric Surgery. JAMA Surg 2015; 150: 644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo LE, Simmons KD, Kelz RR. Bariatric Centers of Excellence: Effect of Centralization on Access to Care. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 221: 914–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Proposed Decision Memo for Bariatric Surgery for the Treatment of Morbid Obesity - Facility Certification Requirement (CAG-00250R3). In: 2013. <https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-proposed-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=266&NcaName=Bariatric+Surgery+for+the+Treatment+of+Morbid+Obesity+-+Facility+Certification+Requirement&TimeFrame=7&DocTvpe=All&bc=AQAAIAAACAAAAA%3D%3D&> Accessed June 18, 2018.

- 37.Tork S, Meister KM, Uebele AL, Hussain LR Kelley SR, Kerlakian GM, et al. Factors Influencing Primary Care Physicians' Referral for Bariatric Surgery. JSLS 2015; 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Funk LM, Jolles S, Fischer LE, Voils CI. Patient and Referring Practitioner Characteristics Associated With the Likelihood of Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg 2015; 150: 999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Losina E, Weinstein AM, Reichmann WM, Burbine SA, Solomon DH, Daigle ME, et al. Lifetime risk and age at diagnosis of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65: 703–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith MD, Patterson E, Wahed AS, Belle SH, Berk PD, Courcoulas AP, et al. Thirty-day mortality after bariatric surgery: independently adjudicated causes of death in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2011; 21: 1687–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tao W, Plecka-Ostlund M, Lu Y, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Causes and risk factors for mortality within 1 year after obesity surgery in a population-based cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015; 11: 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radin EL, Paul IL, Rose RM. Role of mechanical factors in pathogenesis of primary osteoarthritis. Lancet 1972; 1: 519–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loeser RF, Collins JA, Diekman BO. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016; 12: 412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Issa RI, Griffin TM. Pathobiology of obesity and osteoarthritis: integrating biomechanics and inflammation. Pathobiol Aging Age Relat Dis 2012; 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samson AJ, Mercer GE, Campbell DG. Total knee replacement in the morbidly obese: a literature review. ANZ J Surg 2010; 80: 595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Severson EP, Singh JA, Browne JA, Trousdale RT, Sarr MG, Lewallen DG. Total knee arthroplasty in morbidly obese patients treated with bariatric surgery: a comparative study. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27: 1696–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kulkarni A, Jameson SS, James P, Woodcock S, Muller S, Reed MR. Does bariatric surgery prior to lower limb joint replacement reduce complications? Surgeon 2011; 9: 18–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inacio MC, Paxton EW, Fisher D, Li RA, Barber TC, Singh JA. Bariatric surgery prior to total joint arthroplasty may not provide dramatic improvements in post-arthroplasty surgical outcomes. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29: 1359–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin JR, Watts CD, Taunton MJ. Bariatric surgery does not improve outcomes in patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2015; 97-b: 1501–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inacio MC, Kritz-Silverstein D, Raman R, Macera CA, Nichols JF, Shaffer RA, et al. The impact of pre-operative weight loss on incidence of surgical site infection and readmission rates after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29: 458–464.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.