Abstract

Background

The study aims to present the effect of PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations on glucose metabolism and proliferation and identify their underlying mechanisms in cervical cancer.

Methods

The maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax) of tumors was detected by18F-FDG PET/CT scan. In vitro, glycolysis analysis, extracellular acidification rate analysis, and ATP production were used to evaluate the impact of PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations on glucose metabolism. The expression level of key glycolytic enzymes was evaluated by western blotting and immunohistochemical staining in cervical cancer cells and tumor tissues, respectively. Immunofluorescence analysis was used to observe the nuclear translocation of β-catenin. The target gene of β-catenin was analyzed by using luciferase reporter system. The glucose metabolic ability of the xenograft models was assessed by SUVmax from microPET/CT scanning.

Results

Cervical cancer patients with mutant PIK3CA (E542K and E545K) exhibited a higher SUVmax value than those with wild-type PIK3CA (P = 0.037), which was confirmed in xenograft models. In vitro, enhanced glucose metabolism and proliferation was observed in SiHa and MS751 cells with mutant PIK3CA. The mRNA and protein expression of key glycolytic enzymes was increased. AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling was highly activated in SiHa and MS751 cells with mutant PIK3CA. Knocking down β-catenin expression decreased glucose uptake and lactate production. In addition, the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin was found in SiHa cells and tumors with mutant PIK3CA. Furthermore, β-catenin downregulated the expression of SIRT3 via suppressing the activity of the SIRT3 promotor, and the reduced glucose uptake and lactate production due to the downregulation of β-catenin can be reversed by the transfection of SIRT3 siRNA in SiHa cells with mutant PIK3CA. The negative correlation between β-catenin and SIRT3 was further confirmed in cervical cancer tissues.

Conclusions

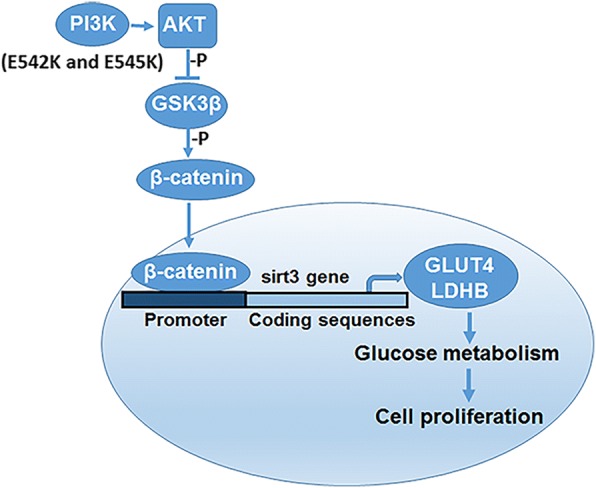

These findings provide evidence that the PI3K E542K and E545K/β-catenin/SIRT3 signaling axis regulates glucose metabolism and proliferation in cervical cancers with PIK3CA mutations, suggesting therapeutic targets in the treatment of cervical cancers.

Trial registration

FUSCC 050432–4-1212B. Registered 24 December 2012 (retrospectively registered).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13045-018-0674-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations, β-Catenin, SIRT3, Glycolysis, Cervical cancer

Background

Cervical cancer remains one of the most common gynecological malignancies, accounting for more than half a million new cases and leading to approximately 266,000 deaths annually worldwide [1]. The clinical outcome of early-stage cervical cancer has been improved due to progress in diagnosis and treatment, whereas the prognosis of advanced and metastatic cervical cancer is still unsatisfactory. Consequently, increasing studies have focused on exploring the molecular characteristics of cervical cancer to identify new therapeutic targets to improve the prognosis of this disease.

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway is recognized as one of the most activated signaling pathways in human cancers. Molecular aberrations of the PI3K pathway drive tumorigenesis and promote various biological processes, including cell proliferation, invasion and migration, differentiation, apoptosis, and glucose metabolism [2–4]. These alterations are mainly caused by PIK3CA amplification or mutation [5, 6] and PTEN loss [7]. PIK3CA mutation has been observed in various solid tumors and plays a crucial and intricate role in carcinogenesis and the development of malignant tumors [8, 9]. In cervical cancer, PIK3CA has been identified as one of the most commonly mutated genes, and the mutation rate ranges from 10 to 30% [10–12]. In a previous study, we demonstrated that E545K, E542K (helical domain), and H1047R (kinase domain) were the hotspots of PIK3CA mutation in cervical cancer. Different from breast cancer, the occurrence of E545K and E542K mutations is dramatically higher than that of H1047R in cervical cancer [13]. PIK3CA mutations in helical and kinase domains exhibit distinct biological and clinical characteristics due to the activation of different signaling pathways. The P110a E545K mutation activates the AKT pathway via interacting with IRS1 instead of the regulatory subunit p85 compared with H1047R mutation [14]. As a result, it is necessary to elucidate the regulatory function of the mutated hotspots E542K and E545K in cervical cancer.

Cancer cells have to readjust their energy metabolism to sustain the uncontrolled proliferation under conditions of complete or deficient nutrients, namely, the Warburg effect, suggesting that cancer cells preferentially utilize aerobic glycolysis to support energetic demands for rapid growth, even in the presence of oxygen [15]. Consequently, some aberrant activation of oncogenic pathways regulates glucose uptake and catabolism. Recent studies suggest that glucose metabolism is mainly reprogrammed by mutations in TP53, MYC, Ras-related oncogenes, and the LKB1-AMP kinase (AMPK) and PI3 kinase (PI3K) signaling pathways [16]. Oncogenic PI3K activation regulates glucose metabolism by regulating a series of downstream signaling effectors. The activation of AKT is essential to stimulate aerobic glycolysis to provide energy for cancer cells [17–19]. The activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway promotes the translocation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) to the plasma membrane in response to insulin stimulation [18]. Furthermore, colorectal cancer cells with PIK3CA mutations exhibit increased proliferation by glutamine dependence [20]. However, the role of mutant PIK3CA on metabolism in cervical cancer is less researched.

In the present study, we demonstrate that PIK3CA mutations promoted glucose metabolism and cervical cancer cell proliferation in vivo and in vitro. Mechanistically mutant PI3K enhanced the expression of β-catenin by activating AKT/GSK3β signaling and promoted the nuclear translocation of β-catenin to transcriptionally decrease the expression of SIRT3, which is a negative regulator of glucose metabolism. These results indicate that PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations play a positive role in regulating glucose metabolism by activating β-catenin/SIRT3 signaling pathways in cervical cancer.

Methods

Patients and specimens

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FUSCC 050432–4-1212B) and conducted in accordance with the approved guidelines. A total of 1015 cervical cancer patients were recruited from January 2010 to December 2014. Altogether, 990 cervical cancer patients were included in the present study, since the cDNA of 25 patients was exhausted. The following inclusion criteria were considered according to a previous publication [13]: pathologically confirmed primary cervical cancer, stage IB1-IIA2 according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system, and no neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation. Tumor tissues were collected during radical hysterectomy procedures. Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to treatment.

Determination of PIK3CA mutation status

The PIK3CA mutation status of 990 patients was detected by Sanger sequencing. A total of 771 patients were recruited from January 2010 to December 2012, and their mutation statuses were reported in a previous study [13]. An additional 219 patients were recruited from January 2013 to December 2014, and the mutation status of these patients was determined as previously described [13]. There was no difference of the mutation status between the 771 patients and the 219 patients.

Whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT scan

Among the 990 patients, PET/CT scan was performed on 52 patients through clinical data retrieval, including 46 patients with wild-type PIK3CA and 6 patients with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations. The SUVmax value of the cervical tumors was detected by PET/CT scan and used to compare the level of glucose metabolism in cervical tumors between patients with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA.

Cell lines and cell culture

A previous study demonstrated that PIK3CA mutations more commonly occurred in squamous carcinoma of the cervix (SCC) [13]. Human SCC cell lines SiHa and MS751 with wild-type PIK3CA were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Both cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin and incubated under 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Plasmid and viral transfection

The plasmid pENTER-PIK3CA E542K and E545K containing the Flag tag and the plasmid with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against the open reading frame of β-catenin mRNA (positions 37–65,5-GCCATGGAACCAGACAGAAA-3) were purchased from Hanyin Biotechnology Limited Company (Shanghai). Then, the plasmid was subcloned into lentivirus vector pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-PURO to construct a recombinant plasmid. Similarly, the control vector was constructed by inserting oligonucleotides encoding short hairpin RNA against green fluorescence protein mRNA (shGFP) into the pLKO.1 vector.

Approximately 30 × 104 SiHa and MS751 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates. The MOI value was set as 10 according to a preliminary experiment. The medium was replaced with 2 ml of virus solution, prepared in accordance with the best MOI value, 30 μl of virus (1 × 108 TU/ml) mixed with 10 μl of polybrene (10 μg/ml), and the rest of the volume was supplemented with culture medium without serum. After 8 h, the medium in the plate was changed to medium with serum. The cells were transferred to 60-mm cell dishes after 48 h and prepared for PURO selection.

The concentration of PURO was determined according to the standard that all cells without virus infection were dead after exposure to a certain concentration of PURO, which was set as 2.5 mg/ml for SiHa and MS751 cells. The cells were treated with PURO for 48 h, and then, the cell medium with PURO was changed to normal medium or medium with PURO for a second round of selection according to the state of the cells. Generally, PURO selection was performed at least twice, and the surviving cells were prepared for identification by Sanger sequencing or western blotting to determine protein expression.

Proliferation assay

The cells were seeded onto 96-well plates with 1 × 103cells/well. Then, 10 μl CCK-8 solution was dissolved in 90 μl of DMEM medium and subsequently added to each well every day for a total of 7 days. The plates were incubated for 2 h, and the absorbance value was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Glycolysis analysis

Glucose Uptake Colorimetric Assay Kits (BioVision) were used to detect the glucose uptake in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA, according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Approximately 3 × 104cells/well were seeded onto 6 wells of a 96-well plate. The medium was replaced with 100 μl of KRPH buffer the next day. Then, 10 μl of 2-DG was added to 3 wells and incubated for 20 min under 37 °C. Subsequently, 80 μl of Extraction Buffer was added and incubated for 40 min under 85 °C, followed by incubation for 5 min on ice, and OD detection was performed after adding 10 μl of neutralization solution. Lactate Colorimetric Assay Kits (Biovision) were used to evaluate the level of lactate production, according to the manufacturer’s protocols. A total of 50 × 104 cells was collected in 1.5-ml EP tubes, and 100 μl of pre-cooling lactate assay buffer was added. After 15 min, the supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 12,000r for 5 min and prepared for OD450 nm.

Extracellular acidification rate analysis

The Seahorse XF Cell Mito stress test kit was used to determine the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, 4 × 104 cells were seeded onto 96-well plates. The final ECAR values were obtained after normalization to the cell number.

ATP (adenosine triphosphate) production analysis

The ENLITEN ATP Assay System (Promega; FF2000) was used to examine ATP production according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A diluted ATP standard was used to build a regression curve to calculate the ATP concentration of the samples. The relative ATP concentration was obtained after normalization to that of control cells.

Western blot assay

Western blot was used to evaluate the protein expression level in the cells as previously described [21]. Antibodies against AKT, pAKT (Ser473 and Ser308), GSK3β, pGSK3β (Ser9), β-catenin, pβ-catenin (Thr41/Ser45), and SIRT3 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (CST), and antibodies against GLUT4 and LDHB (Lactate dehydrogenase B) were purchased from Proteintech. All primary antibodies were diluted 1:1000.

Quantitative real-time PCR

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) was used for total RNA extraction. The cDNA was prepared by using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TAKARA) and subsequently used for real-time PCR analysis by using an ABI 7900HT Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. The following PCR program was used: 95 °C for 10 s, one cycle; 95 °C for 5 s, 62 °C for 31 s, 40 cycles; 2−∆∆CT was used for the relative statistical analysis.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction

SiHa cells with PIK3CA WT E542K and E545K mutation were seeded onto 100-mm dishes at a density of 80–90%. The cells were scraped into 1.5-ml EP tubes after PBS washing. A Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was used for nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). The obtained protein was prepared for protein quantification and western blot analysis.

Immunohistochemical staining (IHC)

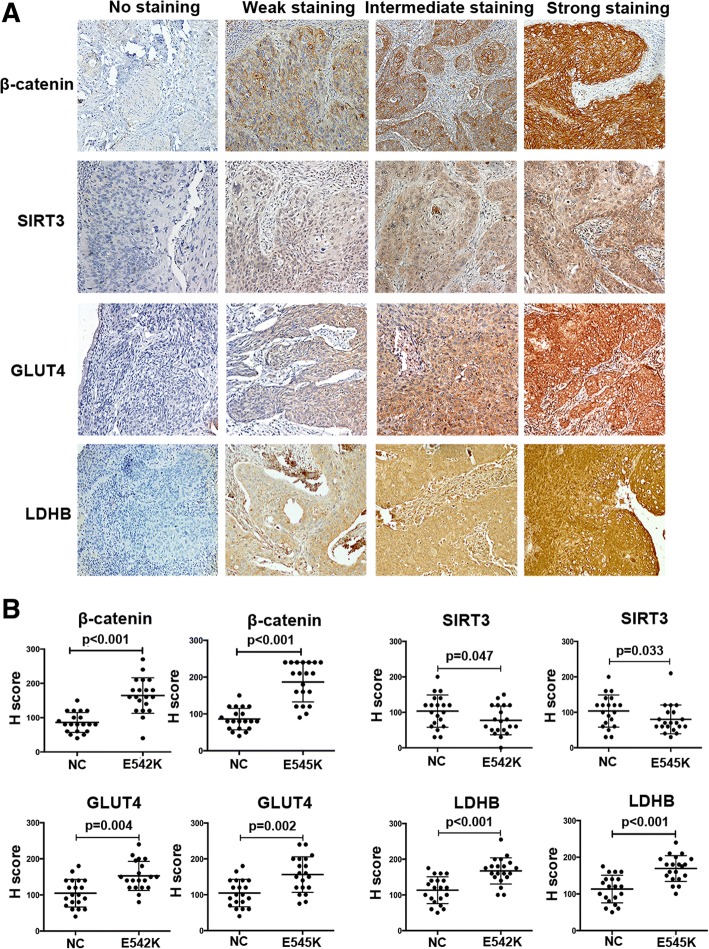

The protein expression in tumors from xenograft models and 60 patients (20 patients with wild-type PIK3CA, 20 patients with mutant PIK3CA E542K, and 20 patients with mutant PIK3CA E545K) was determined by IHC according to a previous publication [21]. Primary antibodies against the following proteins were used: P110a (dilution 1:50, Proteintech), AKT (dilution 1:200, CST), β-catenin (dilution 1:200, Proteintech), SIRT3 (dilution 1:100, CST), GLUT4 (dilution 1:50, Proteintech), and LDHB (dilution 1:1000, Proteintech). The secondary antibody was obtained from an IHC kit from Beijing CoWin Bioscience Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). The staining was repeated by at least three performers who did not know others’ results and assessed by two pathologists blinded to the patients’ information. The final score was calculated as the staining intensity multiplied by staining area. The staining intensity and area of every slide were evaluated after observing five different visual fields by each pathologist. The staining intensity of tissues from patients was evaluated according to the standards shown in Fig. 6 (0 = no staining, 1 = weak staining, 2 = intermediate staining, and 3 = strong staining). The location of β-catenin was evaluated as follows: (1) membrane, if staining was mainly present at membrane but not at nucleus; (2) cytoplasm, if staining was predominant located at cytoplasm but not at nucleus; and (3) nucleus, if staining was present at the nucleus.

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemical analyses of β-catenin, SIRT3, GLUT4, and LDHB expression in tissues of patients with cervical cancer. a Representative pictures of β-catenin/SIRT3 and GLUT4, LDHB in negative, weak staining, intermediate staining, and strong staining. b The statistical analysis of H score of β-catenin/SIRT3 and GLUT4, LDHB in cervical cancer tissues

Immunofluorescence assay

A total of 2 × 104cells were seeded onto 24-well plates containing chamber slides. After attaching to the plate, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min. Then, 0.1% Triton 100 was used to permeabilize the plasma membrane for 30 min. The cells were subsequently washed three times with PBS for 5 min each, blocked with 5% BSA, and incubated in a primary antibody against β-catenin (dilution 1:50, Proteintech) under 4 °C overnight. After washing three times with PBS for 10 min each, the cells were incubated in secondary antibody (1:2000) for 1 h. The slides were counterstained with DAPI and stored under 4 °C in darkness. Images were captured by a Leica SP5 confocal fluorescence microscope.

SiRNA interference

SiRNA against SIRT3, which was obtained from RuiBo Biotechnology Limited Company (Guangzhou), was transfected into SiHa cells by using FuGENE HD (Promega). The sequence was GTCCATATCTTTTTCTGTG.

Luciferase assay

The SIRT3 promotor sequence was cloned into the pGL3-basic reporter gene vector. A plasmid with SIRT3 promotor was designed and constructed by Hanyin Biotechnology Limited Company (Shanghai). SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA (8 × 103 per well) were seeded onto 96-well plates, and then, the vector was transfected into cells with FuGENE HD (Promega). The luciferase reporter gene assays were performed by a luciferase assay system (Promega).

Animal model

Altogether 1 × 107cells (SiHa and MS751) mixed with 100 μl of PBS were injected into BALB/c-nu mice (female, 4 weeks of age; Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd.). Each cell line was implanted into three mice. MicroPET/CT scanning was performed after 18 days. Then, the mice were raised until the 21st day. The tumors were surgically removed, fixed in 10% formalin, and subjected to routine histological examination. The tumor volume was calculated as the longest diameter × the shortest diameter2 × 0.5. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Fudan University and performed according to institutional guidelines.

Statistical analysis

All experiments, except the animal experiments, were repeated three times. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests and one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) were used to evaluate the differences between two groups. GraphPad Prism 6 software (San Diego, CA) was used for the statistical analysis. The statistical significance is defined as P < 0.05.

Results

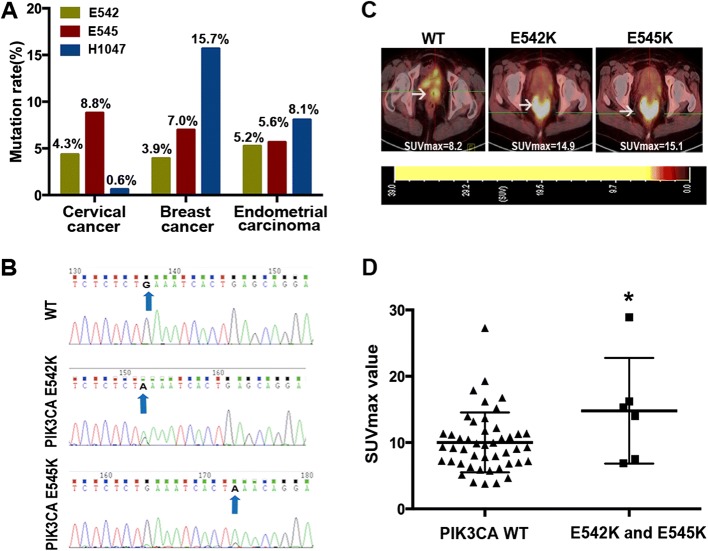

PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations were prominent in cervical cancer

PIK3CA mutations were detected in 146 of the total 990 patients with cervical cancer (146/990, 14.7%), including 132 mutations at exon 9 (132/990, 13.3%) and 14 mutations at exon 20 (20/990, 1.4%). The distribution of amino acid change is shown in Table 1. The frequency of E542 and E545 (exon 9, helical domain) mutation was significantly higher than that of H1047 (exon 20, kinase domain) (Fig. 1a, b). Different from cervical cancer, TCGA database indicated that the PIK3CA H1047 mutation was more common than that of E542 and E545 mutations in breast and endometrial carcinoma (Fig. 1a, b). According to Ciriello et al., among 817 invasive lobular breast cancer patients, 128 patients harbored PIK3CA mutations at H1047 (128/817, 15.7%), which was definitely predominant than that at E542 (32/817, 3.9%) and E545 (57/817, 7.0%) [22]. Similarly, the frequency of variants occurring at H1047 was higher than that at E542 and E545 in endometrial carcinoma (8.1% vs. 5.2% vs. 5.6%) [23]. The mutation distribution is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

PIK3CA mutation distribution in cervical cancer, breast cancer, and endometrial carcinoma

| Cervical cancer (n = 990) | Breast cancer (n = 817) | Endometrial carcinoma (n = 248) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acid change | No. of cases | Frequency of variants (%) | Amino acid change | No. of cases | Frequency of variants (%) | Amino acid change | No. of cases | Frequency of variants (%) | |

| Exon 9 E542 | E542K | 43 | 4.3 | E542K | 30 | 3.7 | E542K | 9 | 3.6 |

| E542G | 2 | 0.2 | E542A | 2 | 0.8 | ||||

| E542Q | 1 | 0.4 | |||||||

| E542V | 1 | 0.4 | |||||||

| Total | 43 | 4.3 | Total | 32 | 3.9 | Total | 13 | 5.2 | |

| Exon 9 E545 | E545K | 84 | 8.5 | E545K | 54 | 6.6 | E545K | 10 | 4.0 |

| E545A | 1 | 0.1 | E542A | 2 | 0.2 | E545D | 2 | 0.8 | |

| E545D | 1 | 0.1 | E545R | 1 | 0.1 | E545A | 1 | 0.4 | |

| E545Q | 1 | 0.1 | E545G | 1 | 0.4 | ||||

| Total | 87 | 8.8 | Total | 57 | 7.0 | Total | 14 | 5.6 | |

| Exon 20 H1047 | H1047R | 5 | 0.5 | H1047R | 116 | 14.2 | H1047R | 12 | 4.8 |

| H1047L | 1 | 0.1 | H1047L | 11 | 1.3 | H1047L | 6 | 2.4 | |

| H1047Y | 1 | 0.1 | H1047Y | 1 | 0.4 | ||||

| H1047Q | 1 | 0.4 | |||||||

| Total | 6 | 0.6 | Total | 128 | 15.7 | Total | 20 | 8.1 | |

Fig. 1.

PIK3CA E542K, E545K mutation and its correlation with 18F-FDG PET/CT SUVmax. a The mutation occurrence of PIK3CA E542, E545, and H1047 in cervical cancer, breast cancer, and endometrial carcinoma. b cDNA sequence of wild-type PIK3CA and mutated at E542K and E545K. c The representative 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in patients with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. d Statistical analysis of SUVmax in groups with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA (n = 52; P = 0.037)

Tumors with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations present higher SUVmax values in18F-FDG PET/CT scan

To evaluate the effect of PIK3CA mutation on glucose metabolism, we analyzed the SUVmax value in 52 patients, including 46 patients with wild-type PIK3CA and 6 patients with PIK3CA mutation at E542 and E545. The results showed that tumors with mutant PIK3CA exhibited higher SUVmax values (P = 0.037) (Fig. 1c, d).

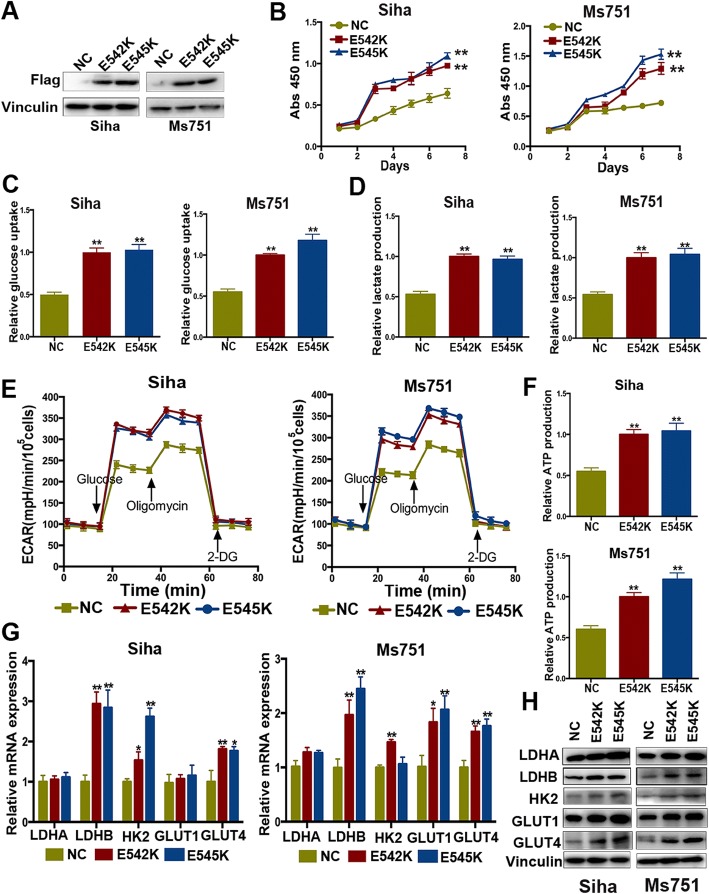

PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations promote glucose metabolism and proliferation in cervical cancer cells

To further determine the function of PI3K E542K and E545K in cervical cancer, we introduced PI3K E542K and E545K cDNA into SiHa and MS751 cells and established SiHa/PI3K E542K, SiHa/PI3K E545K, MS751/PI3K E542K, and MS751/PI3K E545K cells stably expressing PI3K E542K and E545K cDNA (Fig. 2a). The results of the CCK8 assay indicated that PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations significantly promoted cell proliferation in SiHa and MS751 cells (Fig. 2b). To evaluate the effect of PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations on the alteration of glucose metabolism, we analyzed the level of glucose uptake and lactate production and found that cells with mutant PIK3CA had a higher turnover of glucose uptake and lactate production, indicating that PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations enhanced the level of glycolysis in cervical cancer (Fig. 2c, d). ECAR (extracellular acidification rate) is another biomarker to assess glycolysis by measuring the level of lactate production. The results showed that PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations increased ECAR in SiHa and MS751 cells (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, we examined the level of ATP production, a terminal indicator of glucose metabolism. As expected, ATP production was dramatically increased in SiHa and MS751 cells with mutant PIK3CA (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2.

PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations promote proliferation and glucose metabolism in cervical cancer cell. a Transfection of FLAG-tagged PI3K E542K and E545K in SiHa and MS751 cells. b Detection of proliferation by colony formation in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA (**P < 0.01). c The effect of PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutation on glucose uptake (**P < 0.01). d The effect of PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutation on lactate production (**P < 0.01). e ECAR analysis in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. f PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutation affected ATP production (**P < 0.01). g Relative mRNA expression of key enzymes of glycolysis in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). h The effect of PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutation on the expression level of key glycolytic enzyme

To explore the potential underlying mechanism of PIK3CA mutation-mediated glycolysis, key glycolytic enzymes were examined. Higher mRNA and protein expression of key enzymes associated with cell glycolysis (LDHA, LDHB, HK2, GLUT1, and GLUT4) was found in SiHa and MS751 cells harboring mutant PIK3CA (Fig. 2g, f), suggesting that PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations promoted the glycolysis by the increased expression of key glycolytic enzymes. In addition, the expression levels of other glycolytic enzymes increased to varying degrees in SiHa and MS751 cells with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations (Additional file 2: Figure S1a and S1b). Taken together, PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations enhance glucose metabolism and proliferation in cervical cancer cells.

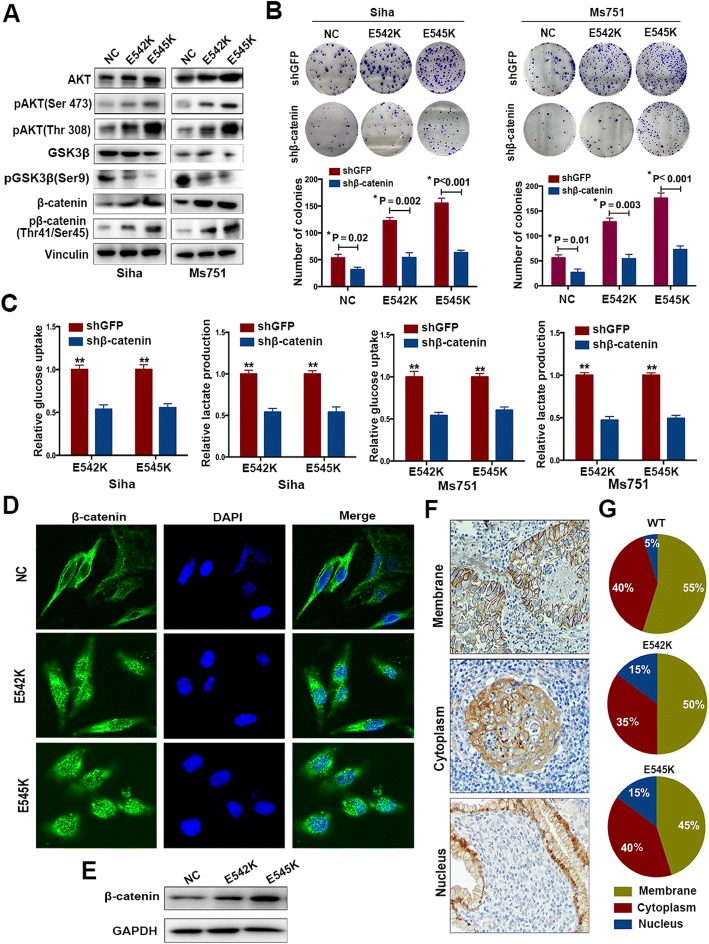

PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations enhance proliferation and glucose metabolism by promoting the expression and nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in cervical cancer cells

PI3K activates the AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathway to regulate cell proliferation; therefore, we compared the expression level of AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. The increased activation of AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin was observed in SiHa and MS751 cells with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations compared to that in cells with wild-type PIK3CA (Fig. 3a). To further explore whether activated AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin was involved in regulating glucose metabolism and proliferation, lentiviruses carrying shRNA against β-catenin were transfected into SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. Colony formation analysis showed that the growth potential was suppressed in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA, but the degree of inhibition was more remarkable in cells with mutant PIK3CA (Fig. 3b). Similarly, the level of glucose uptake and lactate production significantly decreased following the downregulation of β-catenin in SiHa and MS751 cells harboring mutant PIK3CA (Fig. 3c). Moreover, the expression levels of GLUT4 and LDHB were markedly decreased in SiHa and MS751 cells with mutant PIK3CA following the knockdown of β-catenin expression (Fig. 4c), while LDHA, HK2, and GLUT1 did not show evident changes in expression (Additional file 3: Figure S2). Taken together, PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations promote glucose metabolism and proliferation by inducing the AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin in cervical cancer cells.

Fig. 3.

PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations enhance the expression and nuclear accumulation of β-catenin. a The expression of AKT/GSK3 β/β-catenin in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. b The effect of knocking down β-catenin on proliferation in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. c The effect of knocking down β-catenin on glucose uptake and lactate production in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA (**P < 0.01). d The location of β-catenin was analyzed by immunofluorescence staining in SiHa cells. e The expression of β-catenin at nucleus in SiHa cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA by western blotting. f The representative imaging of β-catenin in membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus by IHC in 60 patients with cervical cancer. g The corresponding proportion of β-catenin in membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus in tissues of patients with wild-type and E542K, E545K mutant PIK3CA

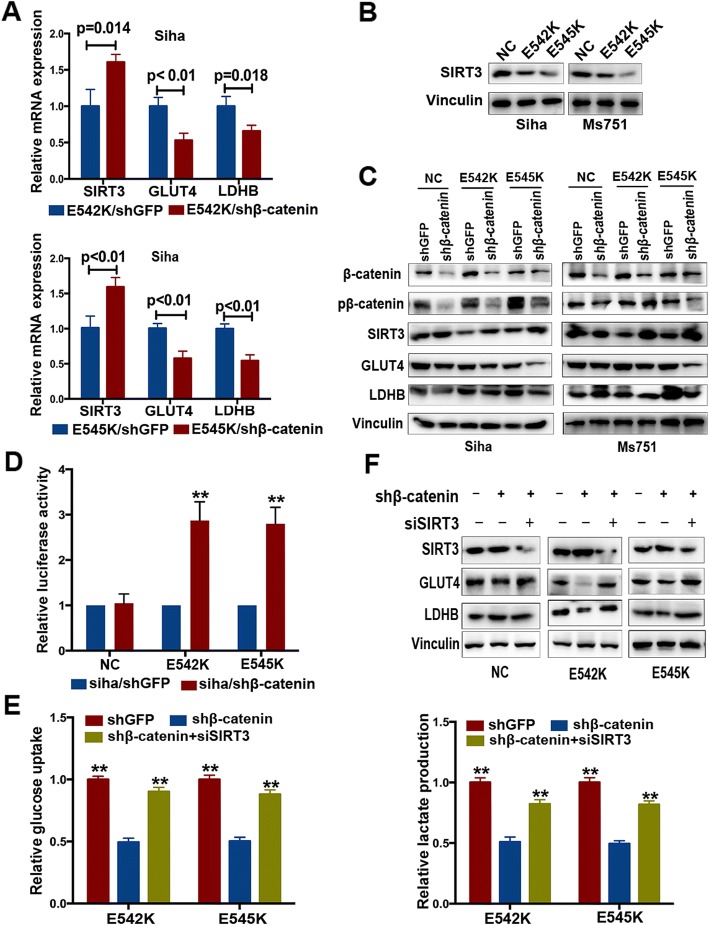

Fig. 4.

SIRT3 is a negative effector of β-catenin in regulating glucose metabolism. a Relative mRNA expression of SIRT3, GLUT4, and LDHB in SiHa cells with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations. b The expression of SIRT3 in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. c Effect of knocking down β-catenin on the expression of SIRT3 and key glycolytic enzymes. d Relative SIRT3 promotor activity in SiHa cells with downregulation of β-catenin (**P < 0.01). e Knocking down SIRT3 rescued the effect of shβ-catenin on glucose uptake, lactate production (**P < 0.01). f Knocking down SIRT3 rescued the effect of shβ-catenin on key glycolytic enzymes

The nuclear accumulation of β-catenin is involved in neoplastic transformation and tumor progression by regulating fat and glucose metabolism [24, 25]. The location of β-catenin is adversely regulated by GSK3β [26, 27]. Considering the high activation of AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin in cervical cancer cells with mutant PIK3CA, we inferred that PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations might promote the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in cervical cancer cells. First, we used immunofluorescence assays to compare the location of β-catenin in SiHa cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. A significantly higher level of nuclear β-catenin expression was observed in SiHa cells with mutant PIK3CA (Fig. 3d). Second, the increased expression of β-catenin in the nucleus was confirmed in SiHa cells with mutant PIK3CA by western blot analysis (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to compare the location distribution of β-catenin in cervical cancer tissues from 40 patients with mutant PIK3CA and 20 patients with wild-type PIK3CA. Representative images of β-catenin in the membrane, cytoplasm, and nucleus are presented in Fig. 3f. Nuclear expression of β-catenin was found in 6 (15%) patients with mutant PIK3CA, which was more common than that in patients with wild-type PIK3CA (1/20), although this finding did not achieve statistical significance, likely due to the limited sample number (P = 0.247, chi-square test, Fig. 3g). Taken together, PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations play a positive role in promoting the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in cervical cancer cells.

β-Catenin regulates glucose metabolism via the suppression of SIRT3 in cervical cancer cells with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations

To further explore the downstream molecular targets regulated by β-catenin, a series of genes involved in glucose metabolism were analyzed in SiHa cells with mutant PIK3CA after the downregulation of β-catenin. We found that the mRNA expression of SIRT3 was marked increased, while that of GLUT4 and LDHB significantly decreased with the downregulation of β-catenin, indicating that SIRT3, GLUT4, and LDHB might be regulated by β-catenin at the transcriptional level (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, we found that the protein expression level of SIRT3 in SiHa and MS751 cells with mutant PIK3CA was significantly lower than that in cells with wild-type PIK3CA (Fig. 4b), and the expression of SIRT3 increased following the knockdown of β-catenin expression (Fig. 4c). Further, correlation analysis indicated it was significantly negative associated with β-catenin in cells with SiHa E545K and MS751 E545K mutation (P < 0.05). Although it did not achieve statistical significance in cells with SiHa E542K and MS751 E542K mutation, it was still suggested that the expression of β-catenin was negatively correlated with that of SIRT3 (Additional file 4: Figure S3). SIRT3, a major mitochondrial deacetylase, mediates metabolic reprogramming and promotes the conversion to glycolysis [28]. Consequently, we inferred that SIRT3 might be involved in glucose metabolism in cervical cancer cells with mutant PIK3CA, which was adversely regulated by β-catenin. A luciferase assay was used to determine whether SIRT3 promotor was regulated by β-catenin in cervical cancer cells with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations. The activity of the SIRT3 promotor markedly increased in SiHa cells with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations following the downregulation of β-catenin, whereas this increase was not evident in SiHa cells with wild-type PIK3CA, suggesting that β-catenin had a negative impact on the promoter activity of SIRT3 in cervical cancer cells with mutant PIK3CA (Fig. 4d). Moreover, the decreased glucose uptake and lactate production due to the downregulation of β-catenin was reversed by transfection with SIRT3 siRNA in SiHa cells with mutant PIK3CA (Fig. 4e). Similarly, the decreased expression of GLUT4 and LDHB was also reversed (Fig. 4f). Taken together, these results demonstrate that SIRT3 functions as a downstream effector of β-catenin in regulating glucose metabolism and glycolysis activity.

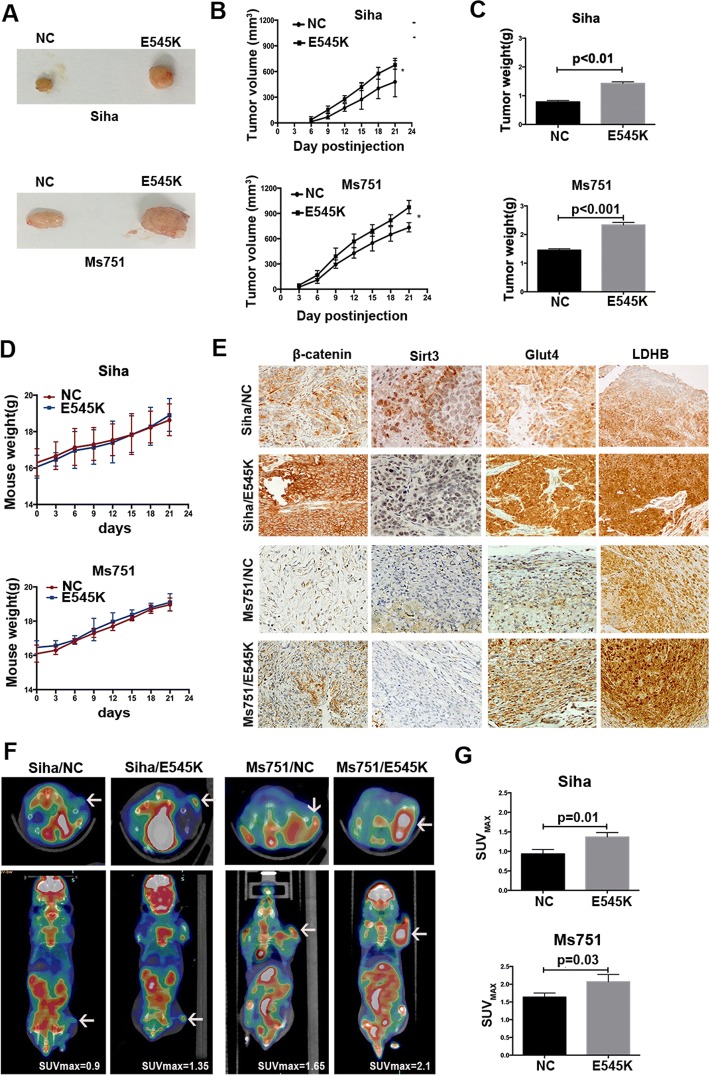

PIK3CA E545K mutation enhances glucose metabolism and proliferation in cervical cancer xenografts

Considering the similar effect of PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations on glucose metabolism and proliferation, we confirmed the effects of PIK3CA E545K mutation in cervical cancer xenografts. SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant E545K PIK3CA were subcutaneously injected into nude mice. Consistently, the growth of tumors with cells harboring mutant PIK3CA was significantly faster than that of tumors with wild-type PIK3CA (Fig. 5a, b). Additionally, the tumors of cells with mutant PIK3CA outweighed those of cells with wild-type PIK3CA (Fig. 5c), and injection had no effect on the weight of nude mice (Fig. 5d). The above results indicate that PIK3CA E545K mutation promotes proliferation in xenograft models.

Fig. 5.

PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations positively regulate proliferation and glucose metabolism in xenograft mice. a The tumors were separated from the xenograft mice with SiHa and MS751 cells harbored wild type and E545K mutant PIK3CA. b The growth curve of xenograft tumors from SiHa and MS751 cells with wild type and E545K mutant PIK3CA. c Tumor weight of xenograft mice with SiHa and MS751 cells harbored wild type and E545K mutant PIK3CA. d The weight of xenograft mice with SiHa and MS751 cells harbored wild type and E545K mutant PIK3CA. e Immunohistochemical staining of xenograft tumor tissues. f Representative 18F-FDG microPET/CT imaging of tumor-bearing mice. The tumors are indicated with arrows. g The tumor SUVmax in xenograft mice with wild type and mutant PIK3CA

We then evaluated the role of PIK3CA E545K mutation in glucose metabolism. Small animal imaging was performed to determine the uptake of 18F-FDG in a xenograft mouse model. The results showed that tumors with mutant PIK3CA exhibited higher 18F-FDG intake, indicating a higher level of glucose uptake in tumors with PIK3CA E545K mutation (Fig. 5f, g). Furthermore, we analyzed the expression of β-catenin, SIRT3, GLUT4, and LDHB by immunohistochemistry in xenografts with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. The expression levels of β-catenin, GLUT4, and LDHB in xenograft models with PIK3CA E545K were enhanced, while that of SIRT3 was decreased compared with those in the corresponding controls, which was consistent with that in cervical cancer cells in vitro (Fig. 5e). Thus, PIK3CA E545K mutation has a positive impact on glucose metabolism in cervical cancer xenografts.

The expression analysis of β-catenin, SIRT3, GLUT4, and LDHB in tissues of patients with cervical cancer

To further verify the association between β-catenin and SIRT3 in glucose metabolism in vivo, we compared the expression of β-catenin, SIRT3, GLUT4, and LDHB in patients with cervical cancers harboring wild-type PIK3CA (n = 20), PIK3CA E542K mutation (n = 20), and PIK3CA E545K mutation (n = 20) by IHC. The expression of these proteins was significantly different between tumors harboring wild-type and mutant PIK3CA (P < 0.05). Correlation analysis showed that the expression of SIRT3 was negatively associated with β-catenin in tumors with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutation, although the curve did not show a good fit (Additional file 5: Figure S4). In addition, the expression of key glycolytic enzymes GLUT4 and LDHB was remarkably higher in tissues with mutant PIK3CA, suggesting that glycolytic metabolism was enhanced in tumors with mutant PIK3CA (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Metabolic reprogramming has been recognized as a hallmark of cancer in recent centuries [29]. To adapt well to nutrient-deficient circumstances, cancer cells activate some metabolic pathways, such as NADPH and ATP, to enhance the production of energy for cell growth and proliferation. However, some oncogenic molecules will be activated and exert positive effects on proliferation and survival [30–32]. The aberrant activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway promotes glucose uptake and glycolysis via the regulation of effectors, such as GLUT1 and GLUT4 [18, 33, 34]. A previous study demonstrated that PIK3CA was the most common mutated gene in cervical cancer. Thus, it was necessary to explore the effect of PIK3CA mutation on proliferation and metabolism alterations in cervical cancer.

18F-FDG PET/CT, an imaging examination based on tumor metabolic activity, has been widely used in the clinic for cancer diagnosis, disease monitoring, and evaluation of treatment response [35–37]. Generally, the elevated SUVmax value indicates enhanced glucose uptake and glycolysis activity. In the present study, we found that the level of glucose metabolism in cervical cancer patients with mutant PIK3CA was dramatically higher than that of patients with wild-type PIK3CA based on the increased SUVmax value detected by 18F-FDG PET/CT. Similar results were obtained in xenograft models. Enhanced proliferation and glucose metabolism was further confirmed in cervical cancer cells and xenograft models with mutant PIK3CA. These results indicate that PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations play a vital role in promoting glycolysis and proliferation in vitro and in vivo.

In terms of mechanism, the AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathway is involved in regulating glucose metabolism. AKT, a well-studied effector of PI3K, is an important driver of tumor glycolytic activity, which enables rapid ATP generation to maintain energetic metabolism. In response to insulin stimulation, the rapid activation of AKT2 increases the expression and translocation of GLUT4, which is essential for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake [18, 34, 38, 39]. AKT signaling also induces the activation of FOXO transcription factors, resulting in a series of downstream transcriptional changes to increase glycolytic capacity [40]. Moreover, the PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway induces the high expression of metabolic gene regulatory networks [41]. Furthermore, AKT negatively regulates GSK3, a type of glycogen synthase, which is responsible for the glycogen synthesis. The inhibition of GSK3 leads to alterations of glucose metabolism via the upregulation of HK2 [42]. Mounting evidence suggested that β-catenin, as an effector of AKT/GSK3, had a close correlation with glucose metabolism. In colorectal cancer cell, β-catenin is translocated to the nucleus and interacts with HIF1α instead of TCF to adjust metabolic patterns during periods of hypoxia [43]. Consequently, we proposed that GSK3β/β-catenin is likely involved in regulating glucose metabolism and proliferation in cervical cancer with mutant PIK3CA. In the present study, the high expression and nuclear translocation of β-catenin was observed in cervical cancer cells and tumor tissues with mutant PIK3CA. The downregulation of β-catenin rapidly decreased the proliferation, glucose uptake, and lactate production of tumors with mutant PIK3CA. The expression of GLUT4 and LDHB were abated following the reduction of β-catenin. Altogether, these results suggest that β-catenin is a vital molecule involved in regulating proliferation and glucose metabolism in cervical cancer cells with mutant PIK3CA.

The sirtuin family has been associated with metabolic regulation in recent years. SIRT3, a member of the sirtuin family, is a type of NAD+-dependent mitochondrial deacetylase, which is involved in negatively regulating glucose metabolism, superoxide levels, and total cellular ATP levels [44]. SIRT3 promotes cellular metabolism and growth by destabilizing HIF1α, a well-known transcription factor regulating glycolysis-related gene expression [45]. The results of the present study suggested that SIRT3 is a direct downstream effector of β-catenin in regulating glucose metabolism. Mechanistically, β-catenin inhibited the activity of the SIRT3 promotor and decreased the expression of SIRT3 at the transcriptional level. Furthermore, the expression of SIRT3 was adversely related to β-catenin in cervical cancer tissues and xenograft models by IHC.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations induce glycolysis in cervical cancer cells through the induction of the β-catenin/SIRT3 signaling pathway (Fig. 7), which offers important implications for the underlying mechanism of PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutation-mediated glycolysis and proliferation, but also provide the new insights into the development of therapeutic approaches using PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations as a target to prevent metastasis in various cancers, including cervical cancer.

Fig. 7.

Mechanism model of PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutation-mediate regulation of proliferation and glucose metabolism via the β-catenin/SIRT3 in cervical cancer

Conclusions

The proliferative and glycolytic potential was enhanced in cervical cancer with PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations in vivo and in vitro. Mechanistically, PIK3CA E542K and E545K mutations promote the expression and nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, which negatively regulates the expression of SIRT3. These findings provide evidence that the PIK3CA E542K and E545K/β-catenin/SIRT3 signaling axis regulates glucose metabolism and proliferation and supply new evidence for the development of therapeutic targets to prevent tumor growth and recurrence.

Additional files

Table S1. The primer sequences are used for qRT-PCR detection. (DOCX 15 kb)

Figure S1. Relative mRNA expression of other glycolytic enzymes in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. A: Relative mRNA expression of other key glycolytic enzymes in SiHa cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. B: Relative mRNA expression of other key glycolytic enzymes in MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. (TIF 1495 kb)

Figure S2. The expression of other key glycolytic enzymes after knocking down the expression of β-catenin. (TIF 1169 kb)

Figure S3. The correlation analysis between β-catenin and SIRT3 by western blotting in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. (TIF 682 kb)

Figure S4. The correlation analysis between β-catenin and SIRT3 in cervical cancer tissues with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. (TIF 457 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81572803) and key research project of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (201640010) for H Yang, National Natural Science Young Foundation of China (81502235) for Z Wang, and National Natural Science Young Foundation of China (81502236) for L Xiang.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact authors for data requests.

Abbreviations

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- ECAR

Extracellular acidification rate

- GLUT1

Glucose transporter 1

- GLUT4

Glucose transporter 4

- HK2

Hexokinase 2

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- LDHA

Lactate dehydrogenase A

- LDHB

Lactate dehydrogenase B

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PVDF

Polyvinylidene fluoride

Authors’ contributions

HJY, ZLW, and LBX designed the study and modified the manuscript. WJ, TCH, and YYZ conducted the experiments. WJ and XP analyzed the data. WJ wrote the manuscript. SL collected the SUVmax value of PET/CT in cervical cancer patients. All authors read and approve the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Review Board and Ethical Committee of Fudan University (FUSCC 050432–4-1212B).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wei Jiang, Email: jiangwei_fuscc@sina.com.

Tiancong He, Email: hetiancong@gmail.com.

Shuai Liu, Email: elaine_liu87@163.com.

Yingying Zheng, Email: zhengyingying91@sina.com.

Libing Xiang, Email: xianglibing_123@sina.com.

Xuan Pei, Email: eveyfdu@163.com.

Ziliang Wang, Phone: 86-21-34777310, Email: huf_zlwang@126.com.

Huijuan Yang, Phone: 86-21-65260535, Email: huijuanyang@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(7):489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samuels Y, Diaz LA, Jr, Schmidt-Kittler O, Cummins JM, Delong L, Cheong I, et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(6):561–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(8):606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miled N, Yan Y, Hon WC, Perisic O, Zvelebil M, Inbar Y, et al. Mechanism of two classes of cancer mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit. Science (New York, NY) 2007;317(5835):239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1135394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huw LY, O'Brien C, Pandita A, Mohan S, Spoerke JM, Lu S, et al. Acquired PIK3CA amplification causes resistance to selective phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors in breast cancer. Oncogenesis. 2013;2:e83. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2013.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollander MC, Blumenthal GM, Dennis PA. PTEN loss in the continuum of common cancers, rare syndromes and mouse models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(4):289–301. doi: 10.1038/nrc3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bader AG, Kang S, Vogt PK. Cancer-specific mutations in PIK3CA are oncogenic in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(5):1475–1479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510857103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasudevan KM, Barbie DA, Davies MA, Rabinovsky R, McNear CJ, Kim JJ, et al. AKT-independent signaling downstream of oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ojesina AI, Lichtenstein L, Freeman SS, Pedamallu CS, Imaz-Rosshandler I, Pugh TJ, et al. Landscape of genomic alterations in cervical carcinomas. Nature. 2014;506(7488):371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature12881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiang L, Li J, Jiang W, Shen X, Yang W, Wu X, et al. Comprehensive analysis of targetable oncogenic mutations in Chinese cervical cancers. Oncotarget. 2015;6(7):4968–4975. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millis SZ, Ikeda S, Reddy S, Gatalica Z, Kurzrock R. Landscape of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase pathway alterations across 19784 diverse solid tumors. JAMA oncology. 2016;2(12):1565–1573. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiang L, Jiang W, Li J, Shen X, Yang W, Yang G, et al. PIK3CA mutation analysis in Chinese patients with surgically resected cervical cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14035. doi: 10.1038/srep14035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hao Y, Wang C, Cao B, Hirsch BM, Song J, Markowitz SD, et al. Gain of interaction with IRS1 by p110alpha-helical domain mutants is crucial for their oncogenic functions. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(5):583–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol. 1927;8(6):519–530. doi: 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boroughs LK, DeBerardinis RJ. Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(4):351–359. doi: 10.1038/ncb3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elstrom RL, Bauer DE, Buzzai M, Karnauskas R, Harris MH, Plas DR, et al. Akt stimulates aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(11):3892–3899. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohn AD, Summers SA, Birnbaum MJ, Roth RA. Expression of a constitutively active Akt Ser/Thr kinase in 3T3-L1 adipocytes stimulates glucose uptake and glucose transporter 4 translocation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(49):31372–31378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yecies JL, Manning BD. Transcriptional control of cellular metabolism by mTOR signaling. Cancer Res. 2011;71(8):2815–2820. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hao Y, Samuels Y, Li Q, Krokowski D, Guan BJ, Wang C, et al. Oncogenic PIK3CA mutations reprogram glutamine metabolism in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11971. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Liu Y, Lu L, Yang L, Yin S, Wang Y, et al. Fibrillin-1, induced by Aurora-a but inhibited by BRCA2, promotes ovarian cancer metastasis. Oncotarget. 2015;6(9):6670–6683. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciriello G, Gatza ML, Beck AH, Wilkerson MD, Rhie SK, Pastore A, et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of invasive lobular breast Cancer. Cell. 2015;163(2):506–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, Shen H, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monga SP. Beta-catenin signaling and roles in liver homeostasis, injury, and tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(7):1294–1310. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chocarro-Calvo A, Garcia-Martinez JM, Ardila-Gonzalez S, De la Vieja A, Garcia-Jimenez C. Glucose-induced beta-catenin acetylation enhances Wnt signaling in cancer. Mol Cell. 2013;49(3):474–486. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu D, Pan W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127(3):469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finkel T, Deng CX, Mostoslavsky R. Recent progress in the biology and physiology of sirtuins. Nature. 2009;460(7255):587–591. doi: 10.1038/nature08197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(2):85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nomura DK, Dix MM, Cravatt BF. Activity-based protein profiling for biochemical pathway discovery in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(9):630–638. doi: 10.1038/nrc2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462(7274):739–744. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carvalho KC, Cunha IW, Rocha RM, Ayala FR, Cajaiba MM, Begnami MD, et al. GLUT1 expression in malignant tumors and its use as an immunodiagnostic marker. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 2011;66(6):965–972. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000600008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang ZY, Zhou QL, Coleman KA, Chouinard M, Boese Q, Czech MP. Insulin signaling through Akt/protein kinase B analyzed by small interfering RNA-mediated gene silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(13):7569–7574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332633100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kidd EA, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. The standardized uptake value for F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose is a sensitive predictive biomarker for cervical cancer treatment response and survival. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1738–1744. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarz JK, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. Association of posttherapy positron emission tomography with tumor response and survival in cervical carcinoma. Jama. 2007;298(19):2289–2295. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooks RA, Rader JS, Dehdashti F, Mutch DG, Powell MA, Thaker PH, et al. Surveillance FDG-PET detection of asymptomatic recurrences in patients with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(1):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eguez L, Lee A, Chavez JA, Miinea CP, Kane S, Lienhard GE, et al. Full intracellular retention of GLUT4 requires AS160 Rab GTPase activating protein. Cell Metab. 2005;2(4):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larance M, Ramm G, Stockli J, van Dam EM, Winata S, Wasinger V, et al. Characterization of the role of the Rab GTPase-activating protein AS160 in insulin-regulated GLUT4 trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):37803–37813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khatri S, Yepiskoposyan H, Gallo CA, Tandon P, Plas DR. FOXO3a regulates glycolysis via transcriptional control of tumor suppressor TSC1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(21):15960–15965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duvel K, Yecies JL, Menon S, Raman P, Lipovsky AI, Souza AL, et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol Cell. 2010;39(2):171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kotliarova S, Pastorino S, Kovell LC, Kotliarov Y, Song H, Zhang W, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition induces glioma cell death through c-MYC, nuclear factor-kappaB, and glucose regulation. Cancer Res. 2008;68(16):6643–6651. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaidi A, Williams AC, Paraskeva C. Interaction between beta-catenin and HIF-1 promotes cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(2):210–217. doi: 10.1038/ncb1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verdin E, Hirschey MD, Finley LW, Haigis MC. Sirtuin regulation of mitochondria: energy production, apoptosis, and signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(12):669–675. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finley LW, Carracedo A, Lee J, Souza A, Egia A, Zhang J, et al. SIRT3 opposes reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism through HIF1alpha destabilization. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(3):416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. The primer sequences are used for qRT-PCR detection. (DOCX 15 kb)

Figure S1. Relative mRNA expression of other glycolytic enzymes in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. A: Relative mRNA expression of other key glycolytic enzymes in SiHa cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. B: Relative mRNA expression of other key glycolytic enzymes in MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. (TIF 1495 kb)

Figure S2. The expression of other key glycolytic enzymes after knocking down the expression of β-catenin. (TIF 1169 kb)

Figure S3. The correlation analysis between β-catenin and SIRT3 by western blotting in SiHa and MS751 cells with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. (TIF 682 kb)

Figure S4. The correlation analysis between β-catenin and SIRT3 in cervical cancer tissues with wild-type and mutant PIK3CA. (TIF 457 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Please contact authors for data requests.