Abstract

Background:

Bedside diagnostic laparoscopy could be helpful in extremely critically ill patients. The aim of this retrospective study is to evaluate the safety and diagnostic accuracy of bedside diagnostic laparoscopy in the identification of intra-abdominal pathology in critically ill patients and to compare its accuracy and outcomes with the ones of laparotomy.

Patients and Methods:

A retrospective review was conducted on the medical records of patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of Careggi University Hospital and submitted to bedside diagnostic laparoscopy between January 2006 and May 2017. This group of patients was compared with a group of patients that were admitted to the ICU and submitted directly to explorative laparotomy for suspected intra-abdominal pathologies.

Results:

One hundred and twenty-nine patients (M/F = 81/48, mean age = 71.64 years) underwent bedside diagnostic laparoscopy in ICU. 154 patients instead were submitted directly to explorative laparotomy in operatory room (mean age 75.70 years, M/F = 94/60). Among the 129 patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy, 53.49% were positive for intra-abdominal pathologies whereas 46.51% were negative, while among the 154 patients submitted directly to laparotomy, 76.62% were positive for intra-abdominal pathologies whereas 23.38% were negative. In 55.03% of all patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy, a non-therapeutic laparotomy was avoided, while the 33.76% of patients submitted directly to laparotomy had a non-therapeutic laparotomy that could be avoidable.

Conclusions:

Our results pinpoint the advantages of performing bedside diagnostic laparoscopy in the ICU setting, which can be considered an option every time there is the suspicion of an intra-abdominal pathology.

Keywords: Bedside laparoscopy, critically ill patients, emergency laparoscopy, Intensive Care Unit

INTRODUCTION

Patients in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) may suffer from a variety of acute abdominal pathologies for which an accurate diagnosis is mandatory and definitive to avoid unnecessary and risky operations in patients that are already critically ill. Difficulties in diagnosis represent a challenge for surgeon and intensivist in anaesthetised, sedated patients, in whom symptoms and signs are unclear, the physical examination is unreliable and laboratory parameters might not provide the necessary data to perform a diagnosis.

The early and appropriate diagnosis of acute life-threatening intra-abdominal pathologies is the key determining the clinical outcome and the only way to increase the patient's chance of survival.

A variety of diagnostic examinations such as ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT) are available for surgeons to help them in such a variety of diagnostic dilemmas, but, although the radiological techniques are non-invasive, they offer varying degrees of diagnostic efficacy and often, in critically ill patients may results non-conclusive.

Historically, in patients with a suspected and occult intra-abdominal disease associated to organ dysfunction, the use of empiric exploratory laparotomy was widespread,[1] even if it has not led to an overall decrease in mortality as the procedure itself involves many risks. Moreover, a large percentage of these laparotomies are negative or non-therapeutic[2] and are associated with a high-morbidity rate (22%).[3]

The aim of this retrospective study is to evaluate the safety and diagnostic accuracy of bedside diagnostic laparoscopy in the identification of intra-abdominal pathology in critically ill patients and to compare its accuracy and outcomes with the ones of laparotomy. The goal is to demonstrate the efficacy of bedside laparoscopy as a diagnostic aid in ICU patients with possible intra-abdominal critical conditions.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data collection

A retrospective review was conducted on the medical records of patients admitted to the ICU of Careggi University Hospital, in Florence (Italy) and submitted to bedside diagnostic laparoscopy between January 2006 and May 2017. To determine the outcome of patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy, this group of patients was compared with a group of patients that were admitted to the ICU of Careggi University Hospital from January 2006 to May 2017 and submitted directly to explorative laparotomy for suspected intra-abdominal pathologies. Data were retrospectively collected from chart records and operating room registers and collected in a database in the General, Emergency and Minimally Invasive Surgery Unit of the Careggi University Hospital.

Indications for bedside laparoscopy

A bedside diagnostic laparoscopy was performed if clinical signs and/or laboratory findings and/or imaging findings were suggestive of intra-abdominal pathologies, without a conclusive diagnosis. Specific indications included unexplained sepsis or multisystem organ failure, a non-conclusive radiological examination or the inability to perform a CT scan because of the critical conditions of the patients.

Contraindications for bedside laparoscopy

Contraindications for bedside diagnostic laparoscopy included patients with a clear indication for surgical operation and/or with a CT scan or US images diagnostic for abdominal pathologies, previous multiple abdominal surgery with multiple incisional scars, the presence of an uncorrectable coagulopathy and the presence of cardiorespiratory failure.

Instrumentation

Bedside diagnostic laparoscopy requires a basic laparoscopic set including a 30° laparoscope, a monitor, an Hasson trocar for the abdominal entry and two 5 mm trocars, manipulating instruments, a light source and cord, insufflator with appropriate tubing and a suction setup. These instruments are stored on one portable cart that can be easily accessed and transferred to the ICU when needed.

Pre-operative technique

All procedures were performed in an isolated single bedroom of the ICU ward [Figure 1]. All the staff present (a nurse from the operating room, one anaesthetist, two ICU nurses and two surgeons) wore protective clothing, a surgical cap, gloves and a surgical mask. The sterility was guaranteed by adherence to routine operating-room protocols.

Figure 1.

Setup of laparoscopic equipment at patient's bedside in Intensive Care Unit

Anaesthesiological technique

The anaesthesiologist monitored the haemodynamics of all the patients including the invasive arterial blood pressure, pulse rate, electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry and on duty directed the administration of total intravenous anaesthesia, ventilation and haemodynamic support. General anaesthesia was performed with a bolus of propofol (1–2.5 mg/kg), midazolam (0.15–0.2 mg/kg) or ketamine (0.5–1 mg/kg) and remifentanil (0.5–1 μg/kg/min) or fentanyl (1–2 μg/kg), followed by an infusion of propofol (4–12 mg/kg/h) and fentanyl (25–100 μg) or remifentanil (0.5–1 μg/kg/min). The neuromuscular block was achieved with atracurium (0.5–0.7 mg/kg). During the procedure, patients were mechanically ventilated (volume-controlled: 6–8 ml/kg; FiO2: 40%–70%; positive end-expiratory pressure: 6–10 cmH2O) and if required, the haemodynamic support was established by means of noradrenaline (0.1–1 μg/kg/min) and/or dobutamine (2–6 μg/kg/min) infusion.

Surgical technique

Patient preparation consisted of cutaneous abdominal disinfection with povidone-iodine (10%), sterile draping and local anaesthesia for the trocar sites. The entry in the abdomen was performed using an open Hasson technique with a 10–12 mm trocar placed in the paraumbilical region. Once the abdomen is insufflated (8–10 mmHg of intra-abdominal pressure), the laparoscope is inserted and the abdomen inspected in all 4 quadrants. A 2nd and 3rd trocar are placed in the left part of the abdomen to explore the right quadrants and then are removed and placed in the right part of the abdomen to explore the left quadrants. At the end of the procedure, the trocars were removed, and the open access entry was closed with a suture of the fascia. The skin was closed with staples or sutures.

Compliance with ethical standards

This retrospective study is in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed with the Chi-square test, Fisher exact test or t-test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and resulting P values were adjusted according to Bonferroni correction method. Data were analysed using the SPSS statistical software, IBM® (New York, United States).

RESULTS

Throughout the time of the study (125 months), 129 patients (M/F = 81/48) with a mean age of 71.64 years, underwent bedside diagnostic laparoscopy in ICU. Within this group of patients, 90 patients were enrolled after post-cardiac surgery, 25 for sepsis and 14 were post-traumatic patients. This bedside laparoscopic group of patients was compared with a group of 154 patients hospitalised in ICU and submitted directly to explorative laparotomy in operatory room (mean age 75.70 years, M/F = 94/60) consisting of 73 patients enroled after post-cardiac surgery, 77 patients for sepsis and four patients after a traumatic event. On average, bedside diagnostic laparoscopy was performed within 11 days (range 6–16) from the ICU admission and lasted 31.27 ± 6.35 min. The general characteristics of the populations studied are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the populations studied

There is no statistically significant difference between the group of patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy and the group of patients submitted directly to laparotomy, except for the mean age that is statistically higher in the laparotomic group (P < 0.05) and the number of septic patients that was higher in the laparotomic group (P < 0.05).

Among the 129 patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy, 69 (53.49%) were positive for intra-abdominal pathologies while 60 (46.51%) were negative whereas among the 154 patients submitted directly to laparotomy, 118 (76.62%) were positive for intra-abdominal pathologies, while 36 (23.38%) were negative. A statistically significant difference was found in terms of positive/negative findings between the two groups (P < 0.05).

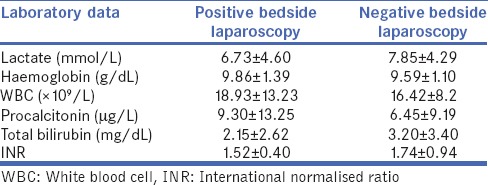

It is important to note that, by analyzing the laboratory data of 129 patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy, there was no statistically significant difference in terms of lactate, haemoglobin, white blood cell, procalcitonin, total bilirubin and international normalised ratio between the positive bedside laparoscopy subgroup (69 patients) and the negative bedside laparoscopy subgroup (60 patients), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Laboratory data of patients with positive and negative findings to bedside laparoscopy

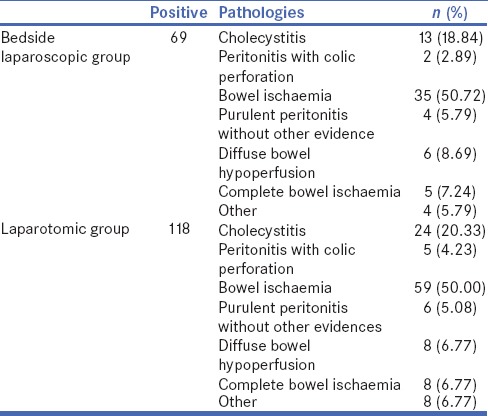

The general results of intra-abdominal pathologies of patients positive to bedside laparoscopy and laparotomic exploration are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

General results of intra-abdominal pathologies of patients positive to bedside laparoscopy and laparotomic exploration

Among the 69 patients with a positive bedside laparoscopy in the ICU, only 58 underwent a surgical operation, as six patients had a bowel hypoperfusion treated conservatively and in 5 patients there was a complete bowel ischaemia from Treitz to the descending colon with no chance of survival for the patients. It is worth considering that in 55.03% of all patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy, a non-therapeutic laparotomy was avoided.

Among the total number of patients submitted to laparotomy, instead, 23.37% had a negative laparotomy without intra-abdominal findings while in 5.19% of patients, there was a complete bowel ischaemia with no chance of survival for the patient (no resection was performed), and in 5.19% of patients, there was a diffuse bowel hypoperfusion without necrosis, not susceptible to surgical treatment. It is evident that the 33.76% of patients submitted directly to laparotomy had a non-therapeutic laparotomy that could be avoidable.

There is a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in terms of therapeutic laparotomies performed and in terms of non-therapeutic laparotomies avoided or avoidable between the group of patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy in ICU and the group of patients submitted directly to laparotomy.

There were two intraoperative complications among the overall patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy (2 omental bleeding deriving from injury due to trocar placement, resolved with coagulation) and 7 among the overall patients submitted directly to laparotomy. There were no statistically significant differences in terms of intraoperatory complications between the group of patients who underwent bedside laparoscopy and the group of patients who were submitted directly to laparotomy, evaluating that parameter even within the subgroup of positive laparoscopy/laparotomy and the negative laparoscopy/laparotomy one.

There were 13 post-operatory complications in patients who underwent bedside laparoscopy (four surgical site infections, five post-operative ileus, three respiratory complications and 1 surgical site haematoma) and 32 in patients who were directly submitted to exploratory laparotomy (14 surgical site infections, six post-operative prolonged ileus, four early mechanical post-operative occlusions, five respiratory complications and three intra-abdominal haematomas). An overall view highlights that the rate of post-operatory complications in the group of patients submitted directly to laparotomy was statistically higher than that of the group of patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy (P < 0.05). Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference in terms of post-operatory complications between the subgroup of patients who were reported positive to bedside laparoscopy and the subgroup of patients who were reported positive to laparotomy, while the rate of post-operative complications in the subgroup of patients who were reported negative to bedside laparoscopy was statistically lower if compared to that of the subgroup of patients who turned out to be negative to laparotomy (P < 0.05).

The overall mortality for patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy was of 30.23%, while for patients submitted directly to laparotomy was of 34.41% (not statistically significant difference). Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference in terms of mortality between patients who had a positive outcome to bedside laparoscopy (40.57%) and laparotomy (33.05%). The percentage of patients deceased after a negative bedside laparoscopy (18.33%) was, instead, statistically inferior to the percentage of patients deceased after a negative exploratory laparotomy (38,88%) (P < 0.05).

There was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in terms of mean operatory time between the 58 patients submitted to laparotomy in operatory room after a bedside laparoscopy in ICU (82.50 ± 45.23) and the 154 patients submitted directly to laparotomy (118.39 ± 31.65).

DISCUSSION

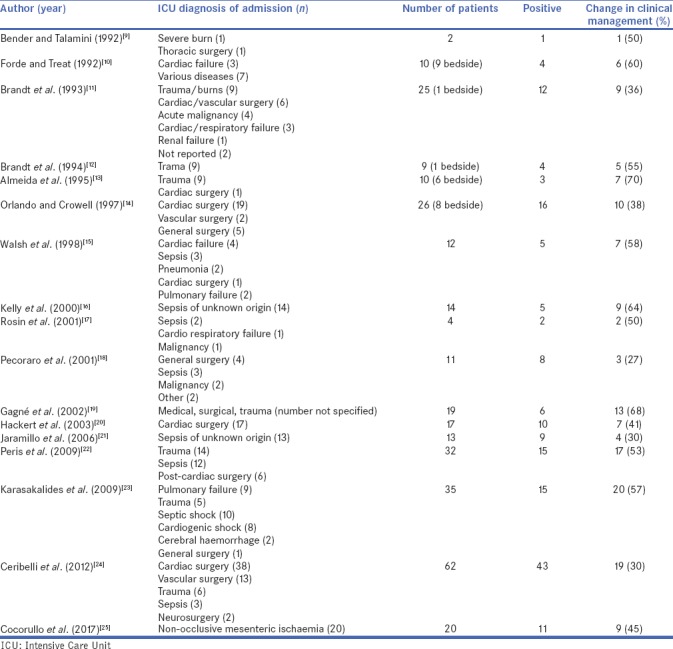

The diagnosis of abdominal pathologies in critically ill patients is often difficult because radiological examinations sometimes do not provide any specific findings. In a recent study published by Just et al. in which the role of CT is analysed in the identification of a potential infectious source in critically ill surgical patients, CT detected an infectious source in 52.8% of cases, and this was associated with a change in treatment in 85.5% of cases. Conversely, patients without identification of an infectious source at CT imaging, treatment was changed in 16.2% of cases.[4] The authors close the study by asserting that CT in clinically ill patients should be analysed more accurately. Moreover, CT is associated with a high sensitivity (96%) in the diagnosis of non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia in patients after cardiovascular surgery, but lacks specificity (33%–60%), with high rates of false-positive results.[5] This aspect may reflect the non-specific nature of many of the imaging features, which are present in 20%–60% of cases.[6] Laparotomy may be considered the major method to perform an accurate diagnosis, but a negative or non-therapeutic laparotomy can be associated with a morbidity rate up to 22%.[3] It is important to consider that a large percentage of these exploratory laparotomies have negative results and that even when they reveal a pathologic condition, surgery may not be life-saving or the condition might be managed non-operatively. Consequently, in extremely critically ill patients, hospitalised in ICU, it is an important to avoid a non-therapeutic laparotomy which will definitely increase morbidity and mortality. Laparoscopy may be helpful in diagnosing abdominal diseases by providing the surgeon with a versatile procedure brought next to the patient, thus avoiding also the inconvenience or risks of transporting the patients (dysrhythmias, hypotension, respiratory distress and artificial airway of intravenous line removal[7,8]). Moreover, it could be helpful mostly when radiological examinations are not conclusive for a diagnosis and there are discrepancies between laboratory tests, clinical findings and radiological imaging, in such selected patients in which a prompt diagnosis and treatment are the sole chance of survival. From 1992 to date, several authors have described their experience with this procedure, and in all the studies, a change in clinical management after bedside laparoscopy is reported with a range from 27% to 70%[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] [Table 4]. All studies highlighted the effectiveness and safety of the procedure in the diagnosis of intra-abdominal conditions in patients with sepsis of unknown origin or in patients who were submitted to open-heart surgery.

Table 4.

Review of literature-bedside diagnostic laparoscopy performed in Intensive Care Unit

In our study, 129 critically ill ICU patients were submitted during 125 months to bedside laparoscopy. Among these patients, 53.49% were positive for intra-abdominal pathologies, while 46.51% were negative. Comparing these data with the group of patients who were submitted directly to laparotomy, it appears evident that the laparotomic group had less negative findings. This may be explained by the fact that while patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy had an inconclusive radiological examination for an intra-abdominal pathology (or it was too risky to transfer them to the radiological department for a CT scan), patients were submitted directly to laparotomy when radiological examinations provided a clear picture of an intra-abdominal condition. However, there is no difference in terms of laboratory data between the patients who were reported positive to bedside laparoscopy and those who were reported negative to it. All these patients had a critical condition and were considered a controversial case. The data stemming from our study show that in 55.03% of all patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy were avoided a non-therapeutic laparotomy, while in patients submitted directly to laparotomy, 33.76% had a non-therapeutic laparotomy that could have been avoided. Even if patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy had similar intraoperatory complications to patients submitted directly to laparotomy, post-operatory complications were higher in the group of patients submitted to laparotomy, especially in the subgroup of patients who were reported negative to explorative laparotomy. Furthermore, even if the mortality rate between patients submitted to bedside laparoscopy was similar to that of patients submitted directly to laparotomy, it appears clearly that the percentage of patients deceased after a negative bedside laparoscopy (18.33%) was statistically lower than the percentage of patients deceased after a negative exploratory laparotomy (38.88%). Moreover, if we consider the mean operating time of the 58 patients submitted to therapeutic laparotomy after a positive bedside laparoscopy, there is evidence that it was lower than that of patients submitted directly to laparotomy. This could be due to the fact that after a bedside exploratory laparoscopy, the surgeon already has a precise plan of what should be performed and can, in fact, perform a kind of ‘tailored laparotomy’.

Bedside laparoscopy definitely provides some advantages for patients in ICU; however, it is also important to consider the constraints and disadvantages of this technique. First of all, it is an invasive procedure which implies the possibility of complications, it is limited to the surface anatomy and has a low sensitivity for retroperitoneal diseases; it requires expertise in the laparoscopic technique and appropriate resources and trained staff. Moreover, it may have a reduced sensitivity in the early stages of intestinal ischaemia because the mucosa can be extensively ischemic while the bowel might still appear normal at external inspection. This drawback may be overcome by using fluorescein-assisted laparoscopy, which can identify also early stages of ischaemia, as reported in our previous study.[26]

While considering all the limitations of this procedure, this study demonstrates the feasibility and accuracy of bedside diagnostic laparoscopy in the assessment of abdominal pathologies in selected critically ill patients in which radiological examinations are not conclusive for a diagnosis and there is a discrepancy between laboratory tests, clinical findings and radiological imaging. A timely diagnosis and treatment are definitely the only chances for survival for critically ill patients, and bedside diagnostic laparoscopy should be included in the diagnostic algorithm for the evaluation of such patients.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our results pinpoint the advantages of performing bedside diagnostic laparoscopy in the ICU setting, which can be considered an option every time there is the suspicion of an intra-abdominal condition based on suggestive, but non-conclusive, laboratory or radiological results, on in the rare case in which it is unsafe to transfer a critically ill patient to the radiology department.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Authors certify that there is no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this article and they state that there are no financial interests or connections, direct or indirect or other situations that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or the conclusions, implications or opinions stated – including pertinent commercial or other sources of funding for the individual author(s) or for the associated department(s) or organisation(s), personal relationships or direct academic competition.

Acknowledgement

Prof. Maria Rosaria Buri, Professional Translator/Aiic Conference Interpreter, University of Salento, for English language editing (http://www.mariarosariaburi.it)

Giorgio Gronchi, P.h.d., for data elaboration and statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Polk HC, Jr, Shields CL. Remote organ failure: A valid sign of occult intra-abdominal infection. Surgery. 1977;81:310–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ott MJ, Buchman TG, Baumgartner WA. Postoperative abdominal complications in cardiopulmonary bypass patients: A case-controlled study. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:1210–3. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Memon MA, Fitztgibbons RJ., Jr The role of minimal access surgery in the acute abdomen. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:1333–53. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70621-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Just KS, Defosse JM, Grensemann J, Wappler F, Sakka SG. Computed tomography for the identification of a potential infectious source in critically ill surgical patients. J Crit Care. 2015;30:386–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwok HC, Dirkzwager I, Duncan DS, Gillham MJ, Milne DG. The accuracy of multidetector computed tomography in the diagnosis of non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia in patients after cardiovascular surgery. Crit Care Resusc. 2014;16:90–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trompeter M, Brazda T, Remy CT, Vestring T, Reimer P. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia: Etiology, diagnosis, and interventional therapy. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1179–87. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braman SS, Dunn SM, Amico CA, Millman RP. Complications of intrahospital transport in critically ill patients. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:469–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-4-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brokalaki HJ, Brokalakis JD, Digenis GE, Baltopoulos G, Anthopoulos L, Karvountzis G, et al. Intrahospital transportation: Monitoring and risks. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1996;12:183–6. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(96)80554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender JS, Talamini MA. Diagnostic laparoscopy in critically ill Intensive-Care-Unit patients. Surg Endosc. 1992;6:302–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02498865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forde KA, Treat MR. The role of peritoneoscopy (laparoscopy) in the evaluation of the acute abdomen in critically ill patients. Surg Endosc. 1992;6:219–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02498806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt CP, Priebe PP, Eckhauser ML. Diagnostic laparoscopy in the intensive care patient. Avoiding the nontherapeutic laparotomy. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:168–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00594100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandt CP, Priebe PP, Jacobs DG. Value of laparoscopy in trauma ICU patients with suspected acute acalculous cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:361–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00642431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almeida J, Sleeman D, Sosa JL, Puente I, McKenney M, Martin L, et al. Acalculous cholecystitis: The use of diagnostic laparoscopy. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1995;5:227–31. doi: 10.1089/lps.1995.5.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlando R, 3rd, Crowell KL. Laparoscopy in the critically ill. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:1072–4. doi: 10.1007/s004649900532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh RM, Popovich MJ, Hoadley J. Bedside diagnostic laparoscopy and peritoneal lavage in the Intensive Care Unit. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1405–9. doi: 10.1007/s004649900869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly JJ, Puyana JC, Callery MP, Yood SM, Sandor A, Litwin DE, et al. The feasibility and accuracy of diagnostic laparoscopy in the septic ICU patient. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:617–21. doi: 10.1007/s004640010068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosin D, Haviv Y, Kuriansky J, Segal E, Brasesco O, Rosenthal RJ, et al. Bedside laparoscopy in the ICU: Report of four cases. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001;11:305–9. doi: 10.1089/109264201317054618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pecoraro AP, Cacchione RN, Sayad P, Williams ME, Ferzli GS. The routine use of diagnostic laparoscopy in the Intensive Care Unit. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:638–41. doi: 10.1007/s004640000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagné DJ, Malay MB, Hogle NJ, Fowler DL. Bedside diagnostic minilaparoscopy in the intensive care patient. Surgery. 2002;131:491–6. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.122607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hackert T, Kienle P, Weitz J, Werner J, Szabo G, Hagl S, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic laparoscopy for early diagnosis of abdominal complications after cardiac surgery. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1671–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaramillo EJ, Treviño JM, Berghoff KR, Franklin ME., Jr Bedside diagnostic laparoscopy in the Intensive Care Unit: A 13-year experience. JSLS. 2006;10:155–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peris A, Matano S, Manca G, Zagli G, Bonizzoli M, Cianchi G, et al. Bedside diagnostic laparoscopy to diagnose intraabdominal pathology in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care. 2009;13:R25. doi: 10.1186/cc7730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karasakalides A, Triantafillidou S, Anthimidis A, Ganas E, Mihalopoulou E, Lagonidis D, et al. The Use of Bedside Diagnostic Laparoscopy in the Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques. 2009;19:333–338. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceribelli C, Adami EA, Mattia S, Benini B. Bedside diagnostic laparoscopy for critically ill patients: A retrospective study of 62 patients. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3612–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cocorullo G, Mirabella A, Falco N, Fontana T, Tutino R, Licari L, et al. An investigation of bedside laparoscopy in the ICU for cases of non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:4. doi: 10.1186/s13017-017-0118-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alemanno G, Somigli R, Prosperi P, Bergamini C, Maltinti G, Giordano A, et al. Combination of diagnostic laparoscopy and intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescence angiography for the early detection of intestinal ischemia not detectable at CT scan. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;26:77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]