Abstract

Background:

Anastomotic leaks after oesophagectomy with tabularised stomach replacement are a significant factor in post-operative mortality and morbidity. Early detection and treatment of this complication allow for improving operative and oncological results. When assessing laboratory values – elevation of inflammatory parameters – complicated interpretation is an issue (systemic inflammatory response syndrome, surgical versus non-surgical complication). Results studying the relationship between C-reactive protein (CRP) and complications following oesophagectomies are inconsistent. The aim of our work was to find relationships between the development of post-operative CRP values and the occurrence of anastomotic complications following minimally invasive oesophagectomy (MIE).

Materials and Methods:

Analysis of the relationship between CRP values and the occurrence of anastomotic complications or the necessity of reoperation following oesophagectomy with tabularised stomach replacement and cervical anastomosis performed using thoracoscopy and laparoscopy in a group of patients operated on for malignancies at our department between 2012 and 2015.

Results:

A significant difference was found in average CRP values on the 5th day and 7th day following operation between patients with and without leaks (233 mg/l vs. 122.8 mg/l P = 0.003, respectively 208.9 mg/l vs. 121.3 mg/l P = 0.014). However, on the 5th day, the leak was clinically apparent only in one case out of 11 leaks. A significant difference in CRP values on the 5th day was found between patients who needed revision surgery and patients without revision surgery (294 mg/l vs. 133.5 mg/l P = 0.01).

Conclusions:

Patients after MIE with tabularised stomach replacement and cervical anastomosis complicated by anastomotic leaks or with the necessity for reoperation had a significantly higher CRP values on the 5th day following operation than patients without complications, regardless of the presence of clinical signs of leaks.

Keywords: Anastomotic leak, C-reactive protein, minimally invasive oesophagectomy, oesophagal carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

The most commonly used replacement following the resection of the oesophagus performed due to tumours is the tabularised stomach with an anastomosis in the chest or on the neck. The potential anastomotic leak is linked to significantly increased post-operative morbidity and mortality.[1,2] Only early identification and treatment of this life-threatening complication can improve the results. An anastomotic leak may be signalled by a change in the overall clinical condition, laboratory values, or a finding achieved through imaging methods. The interpretation of laboratory findings, such as elevation of inflammatory parameters of the C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT) may be complicated in the diagnostics of anastomotic leaks since oesophagectomy, as an extensive surgical operation, induces a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).[3] Accurately distinguishing between surgical and respiratory complications, which are common after oesophageal resections, might also be an issue.[4]

When detecting infectious complications, PCT is generally a more specific marker than CRP. CRP is inexpensive, highly sensitive but non-specific marker for early diagnostics of post-operative complications.[5] Differences in CRP values that might predict infectious complications were observed mainly in colorectal surgery where a CRP value of 135 mg/l on the 4th day following operation was defined as significant.[6]

Surgical approach may play an important role in interpreting post-operative CRP values. Most works describe the laparoscopic approach as causing a weaker post-operative immune response than open surgeries. This finding relates to elective[7] as well as acute[8,9] laparoscopic operations. The results of works comparing CRP levels after open and minimally invasive oesophagectomies (MIEs) are rather inconsistent. According to Scheepers CRP levels after open and MIE are comparable.[10] However, the work of Tsujimota shows that CRP elevation is lower after a minimally invasive approach than after open surgery and that the relationship between infectious complications and post-operative CRP level is not clear.[11]

The aim of this work was, therefore, to find the relationship between the development of post-operative CRP values and the occurrence of anastomotic complications following MIE performed through thoracoscopic and laparoscopic approaches with tabularised stomach replacement and cervical anastomosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of patients

The studied group included patients with MIE indicated for oesophageal tumours. All patients were discussed in an interdisciplinary indication committee regarding the indication of neoadjuvant oncological therapy or primary resection surgery and signed informed consent to the treatment and their enrolment in the studied group. Patients with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy underwent the operation after 6–8 weeks. All patients in this group underwent mini-invasive oesophagectomy with cervical anastomosis.

Surgical technique

The operation was initiated in the pronation position, without selective ventilation, by right-sided thoracoscopy. After the interruption of the vena azygos, the thoracic part of the oesophagus was released and lymphadenectomy was performed. After the change of position into supination there followed laparoscopic interruption of short gastric veins, and releasing of the greater curvature of the stomach with the examination of the gastroepiploic arterial arcade. The fundus of the stomach was then released along with the gastro-oesophagal junction and abdominal oesophagus. Lymphadenectomy around the branches of the truncus coeliacus and the Kocher manoeuvre were performed. The cervical oesophagus was released and interrupted through an incision on the left side of the neck. The stomach and resected oesophagus were taken out from a short transversal laparotomy in the epigastrium. Stapler stomach tabularisation was performed with a standard width of tubule of 4 cm. Pyloroplasty was performed in all patients. After the transposition of the tabularised stomach through posterior mediastinum, the cervical anastomosis was constructed side-to-side using a 60 mm long endostapler.

The study was performed in a group of 40 patients aged 41–75. The occurrence of post-operative complications was monitored as follows: leaks, anastomotic stenosis and the necessity of revision surgery with respect to CRP values. Perioperative CRP values were <5 mg/l in all patients. A total of 28 patients underwent neoadjuvant therapy, and 12 patients were operated on primarily. In 34 cases, the tumours were adenocarcinomas and in 6 spinocelular carcinomas.

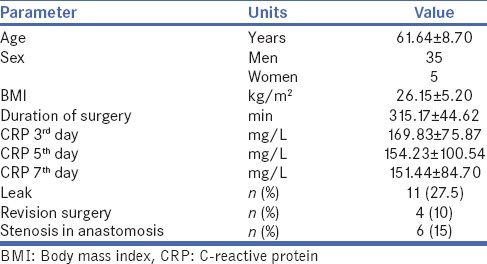

The specification and observed parameters of the studied group are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specification of the group

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 10.0 software. The Mann–Whitney non-parametric test was used to assess the relationship of CRP values on the 3rd, 5th and 7th days following operations to the occurrence of anastomotic leaks, number of revisions and post-operative stenosis in anastomosis (or finding the difference between average CRP values on the 3rd, 5th and 7th days following operation between patients with leaks and without leaks, i.e., with necessary revision and without it, with developed stenosis and without stenosis within the entire group).

RESULTS

A total of 40 patients were indicated for MIE between January 2012 and June 2015. The length of the monitoring period after the operation was at least 1 year. Anastomotic leaks occurred in 11 of the operated patients. Two cases of those showed clinical signs of sepsis with necessary revision due to pathological secretion leaking into the right hemithorax. In other cases, the leak resolved without reoperation, and pathological secretion disappeared within 1 week of local treatment of the cervical incision. One patient died due to sepsis. Two other reoperations were indicated due to profuse chylous secretion from the thoracic drainage and dehiscence of the laparotomy. Stenosis in anastomosis occurred in six cases which were resolved through repeated endoscopic dilation.

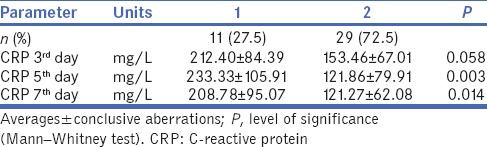

A significant difference was found in average CRP values on the 5th and 7th days following operation between patients with and without leaks. Patients with leaks had higher CRP values. The difference between the average CRP values of both groups on the 3rd day following operation was not significant. The average CRP value in patients without leaks was 122.8 mg/l on the 5th day after operation and 233 mg/l in patients with leaks [Table 2].

Table 2.

Differences in C-reactive protein values on the 3rd, 5th and 7th day following operation between patients with leaks (1) and without leaks (2)

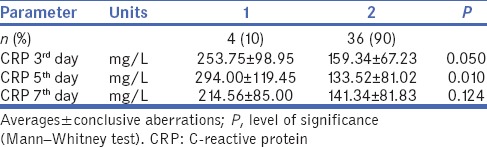

A significant difference was found in average CRP values on the 5th day following operation between patients needing revision surgery and patients that did not. Patients whose condition required reoperation in due course had significantly higher CRP values. The difference in average CRP values on the 3rd day between both groups was of borderline significance. Differences in CRP values on the 7th day following operation between both groups were not significant [Table 3].

Table 3.

Differences in C-reactive protein values on the 3rd, 5th and 7th days following operation between patients needing revision surgery (1) and patients that did not (2)

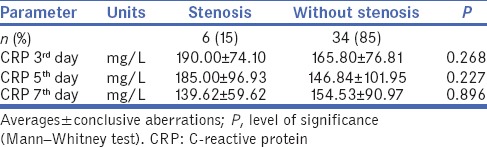

No significant difference was found in average CRP values on the 3rd, 5th and 7th days following operation between patients who developed stenosis and patients who did not [Table 4].

Table 4.

Differences in C-reactive protein values on the 3rd, 5th and 7th day following operation between patients with stenosis in anastomosis (1) and without stenosis in anastomosis (2) within the entire group

No differences in post-operative CRP values were found between patients after neoadjuvant therapy and patients operated on primarily.

DISCUSSION

The rate of mortality after oesophageal resections has significantly decreased in recent years; some authors even claim it to be below 2%. Post-operative morbidity is decreasing as well.[12] It is not possible to prove securely whether this positive development has occurred due to improved pre-operative preparation, new anaesthetic methods or the use of minimally invasive approaches. Assessing the benefit of the minimally invasive techniques is difficult due to their variety. A significant number of deaths following oesophageal resections relate to the presence of anastomotic leaks. Half of the patients after healed leaks then encounter problems with anastomotic stenosis, which negatively impacts their quality of life.[13] Early identification of patients with developing surgically induced infectious complications may lead to the quicker onset of treatment. On the other hand, distinguishing between ‘normal’ SIRS and infectious complications may also prevent unavailing antibiotic therapy and its potential complications.[14]

The published literature presents various ways of proving leaks, usually through radiology. There is a dispute as to whether such examinations should be performed routinely or only in symptomatic patients. The problem of routine examinations is their low benefit for the actual treatment. A sensitivity of only 54% for leak detection was mentioned even in the case of routinely performed computed tomography oesophagography. Accuracy improved in correlation with laboratory methods, possibly also with the determination of elevated amylase values from thoracic drainage.[15] Routine radiological examination of cervical anastomoses was disputed by Boone et al. as 53% of patients clearly had a leak before the routine passage with aqueous stain, planned for the 7th day after the operation, was actually performed.[16] Leaks occurring earlier than on the 7th day after operation were found in three patients in our group, in three cases, it occurred on the 7th day, and in four cases, it occurred later.

Routine endoscopic examination on the 7th day following the operation is recommended by Page. The benefit of this approach, besides the detection of defects in the anastomosis or the stapler line of the tabularised stomach, is the possibility of assessing the vitality of tissues, which cannot be achieved with radiological methods.[17] In his group, Page did not describe any complications related to the performance of endoscopy; however, it is an invasive examination, and it is disputable whether it should be performed on patients in good clinical condition where laboratory findings show no evidence of infectious complications. The advantage of endoscopy is the possibility of therapeutic intervention to resolve leaks from the oesophagogastric anastomosis.[18] Considering the invasive character, high cost and dilemma regarding the ideal timing of the examination methods proving leaks it seems rational to monitor the post-operative dynamics of an inexpensive and easily available laboratory marker such as CRP and carry out potential examinations individually.

We found a statistically significant difference in CRP values on the 5th day following operation in the group of patients with leaks. At that time, a leak had been clinically manifested in one patient only, but it occurred in 10 other patients later on. Some published papers describe significant differences on the 3rd day following open transthoracic oesophagectomy.[3] The published data available is not sufficient to consider whether that time difference may relate to the fact that the patients in our group underwent minimally invasive methods. An interesting fact is that the CRP values on the 5th day following operation in the group without the need for revision surgery (133 mg/l) and without leaks (122 mg/l) are very close to the value of 135 mg/l that is presented as a threshold below which there is a very small risk of an anastomotic leak in colorectal surgery.[6]

The importance of post-operative CRP elevation is assessed in relation to early post-operative complications as well as from a long-term perspective. A significant post-operative CRP elevation following oesophagectomy, i.e., an intense post-operative inflammatory response, was proved as a negative factor for the length of survival after oesophagectomy.[19] Minimally invasive operations generally reduce the response of the organism in the post-operative period. There is no consistent data available for the conditions following oesophagectomy, which can be caused by the greater variety of minimally invasive approaches, and significant surgical trauma after surgery in two cavities is indisputable.[10,11] When assessing long-term results in relation to problems with the healing of anastomosis we also focussed on the potential correlation between CRP elevation and the occurrence of anastomotic stenosis. We did not prove this correlation in our group. Of the 6 patients with stenosis occurrence, three had leaks after the operation, and patients had no complications with the healing of the anastomosis. Similarly, we did not record any differences in CRP values between the group of patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and the primarily resected ones.

CONCLUSIONS

Post-operative monitoring of CRP level development dynamics following oesophagectomy might be beneficial in determining the risk group for the occurrence of leaks. This work considers these risks in a group of patients following MIE. Patients with CRP values on the 5th day after operation <133 mg/l or 122 mg/l are at a low risk that revision surgery would be needed or that anastomotic leaks would occur. This easily available and inexpensive marker allows for stratifying patients by the risk of leaks before most leaks are demonstrated clinically. This approach, therefore, enables selective indication of further examinations aimed at confirmation of the leak and the early-onset of adequate treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grotenhuis BA, van Hagen P, Reitsma JB, Lagarde SM, Wijnhoven BP, van Berge Henegouwen MI, et al. Validation of a nomogram predicting complications after esophagectomy for cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:920–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrott PW, Markar SR, Kuppusamy MK, Traverso LW, Low DE. Accordion severity grading system: Assessment of relationship between costs, length of hospital stay, and survival in patients with complications after esophagectomy for cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:331–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durila M, Bronský J, Haruštiak T, Pazdro A, Pechová M, Cvachovec K, et al. Early diagnostic markers of sepsis after oesophagectomy (including thromboelastography) BMC Anesthesiol. 2012;12:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-12-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsujimoto H, Ono S, Takahata R, Hiraki S, Yaguchi Y, Kumano I, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome as a predictor of anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy. Surg Today. 2012;42:141–6. doi: 10.1007/s00595-011-0049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoeboer SH, Groeneveld AB, Engels N, van Genderen M, Wijnhoven BP, van Bommel J, et al. Rising C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels precede early complications after esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:613–24. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2745-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warschkow R, Beutner U, Steffen T, Müller SA, Schmied BM, Güller U, et al. Safe and early discharge after colorectal surgery due to C-reactive protein: A diagnostic meta-analysis of 1832 patients. Ann Surg. 2012;256:245–50. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825b60f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C, Huang R, Jiang T, Huang K, Cao J, Qiu Z, et al. Laparoscopic and open resection for colorectal cancer: An evaluation of cellular immunity. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:127. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sista F, Schietroma M, Santis GD, Mattei A, Cecilia EM, Piccione F, et al. Systemic inflammation and immune response after laparotomy vs.laparoscopy in patients with acute cholecystitis, complicated by peritonitis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5:73–82. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v5.i4.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schietroma M, Piccione F, Carlei F, Clementi M, Bianchi Z, de Vita F, et al. Peritonitis from perforated appendicitis: Stress response after laparoscopic or open treatment. Am Surg. 2012;78:582–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheepers JJ, Sietses C, Bos DG, Boelens PG, Teunissen CM, Ligthart-Melis GC, et al. Immunological consequences of laparoscopic versus open transhiatal resection for malignancies of the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Dig Surg. 2008;25:140–7. doi: 10.1159/000128171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsujimoto H, Ono S, Sugasawa H, Ichikura T, Yamamoto J, Hase K, et al. Gastric tube reconstruction by laparoscopy-assisted surgery attenuates postoperative systemic inflammatory response after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2010;34:2830–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0757-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Awais O, Levy RM, Keeley S, Shende M, et al. Outcomes after minimally invasive esophagectomy: Review of over 1000 patients. Ann Surg. 2012;256:95–103. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182590603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briel JW, Tamhankar AP, Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Johansson J, Choustoulakis E, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for ischemia, leak, and stricture of esophageal anastomosis: Gastric pull-up versus colon interposition. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:536–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verhage RJ, Hazebroek EJ, Boone J, Van Hillegersberg R. Minimally invasive surgery compared to open procedures in esophagectomy for cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Minerva Chir. 2009;64:135–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker EH, Hill JS, Reames MK, Symanowski J, Hurley SC, Salo JC, et al. Drain amylase aids detection of anastomotic leak after esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:181–8. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boone J, Rinkes IB, van Leeuwen M, van Hillegersberg R. Diagnostic value of routine aqueous contrast swallow examination after oesophagectomy for detecting leakage of the cervical oesophagogastric anastomosis. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:784–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page RD, Asmat A, McShane J, Russell GN, Pennefather SH. Routine endoscopy to detect anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schubert D, Scheidbach H, Kuhn R, Wex C, Weiss G, Eder F, et al. Endoscopic treatment of thoracic esophageal anastomotic leaks by using silicone-covered, self-expanding polyester stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:891–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda S, Takeuchi H, Kawakubo H, Fukuda K, Nakamura R, Takahashi T, et al. Correlation between intense postoperative inflammatory response and survival of esophageal cancer patients who underwent transthoracic esophagectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4453–60. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4557-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]