Abstract

Background:

Adults who were victims of childhood maltreatment tend to have poorer health compared to adults who did not experience abuse. However, many are in good health. We tested whether safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships buffer women with a history of childhood maltreatment from poor health outcomes in later life.

Methods:

Participants included women from the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study who were involved in an intimate relationship at some point by the time their twin children were 10 years old. Women were initially interviewed in 1999–2000 (mean age=33 years) and two, five, and seven years later. They reported on their physical and mental health, and their health risk behaviours.

Results:

Compared to women who did not experience abuse in childhood, women with histories of maltreatment were at elevated risk for mental, physical, and health risk behaviours including major depressive disorder, sleep and substance use problems. Cumulatively, safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships characterized by a lack of violence, emotional intimacy and social support buffered women with a history of maltreatment from poor health outcomes.

Conclusions:

Our findings emphasize that negative social determinants of health – such as a childhood history of maltreatment – confer risk for psychopathology and other physical health problems. If, however, a woman’s current social circumstances are sufficiently positive, they can promote good health, particularly in the face of past adversity.

Prospective and retrospective longitudinal studies consistently show that adults who were victims of abuse or neglect in childhood have poorer mental and physical health than adults who did not experience maltreatment in their early years (Gilbert et al., 2009; Irish et al., 2010; Wegman & Stetler, 2009). These mental health problems include elevated rates of major depressive and generalized anxiety disorders, substance abuse disorders (particularly among women), criminal behaviour, personality disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Afifi et al., 2012; Cohen et al., 2001; Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Scott et al., 2010; Thornberry et al., 2010; Widom, 1999; Widom et al., 2009; Widom et al., 2007; Widom et al., 1995). Physical health problems include elevated rates of asthma (Scott et al., 2012), obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome (Danese et al., 2009; Midei et al., 2013; Noll et al., 2007; Widom et al., 2012), cardiovascular disease (Dong et al., 2004), decreased levels of albumin (which is a marker for kidney and liver disease) (Widom et al., 2012), and poorer self-reported health (Herrenkohl et al., 2013; Irving & Ferraro, 2006). Although childhood maltreatment is correlated with other risk factors for poor health – notably poverty (Sedlak et al., 2010) – maltreatment increases the risk for mental and physical problems even in samples where maltreated and non-maltreated groups are matched for sociodemographic characteristics (Thornberry et al., 2010; Widom et al., 2012). Thus, maltreatment is not merely a marker for some true cause, but is itself likely to be a distal or proximal cause of poor health.

Nevertheless, many adults are in good health despite their childhood history of maltreatment. From an intervention perspective, it is important to identify factors that explain individual differences in the response to adverse early experiences like maltreatment. The goal of our research was to test whether differences in the experience of safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships in adulthood explained why some women were resilient to the adverse effects of childhood maltreatment on adult health while others were not. Safe, supportive and nurturing relationships involve intimate relationships – usually with a romantic partner, but also with friends – that are free of physical or emotional violence and that offer emotional and material support (Merrick et al., 2013). This concept is closely related to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (2014) Essentials for Childhood framework that, along with safety and nurturance, promotes stability in relationships and environments as fundamental for children’s positive development. Socially supportive relationships may generally promote positive outcomes because they increase positive affect, provide stability, validate the individual’s sense of self-worth, and help the individual avoid negative experiences (Cohen & Wills, 1985).

Safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships may be particularly important for women who have childhood histories of maltreatment for two reasons. First, to the extent that victims of childhood maltreatment experience higher-than-average rates of stressful life events across the life course (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002), the presence of safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships may buffer women from these on-going adversities. For example, children who are victims of maltreatment are at elevated risk of exposure to other forms of violence, including bullying, adult domestic violence, and community violence (Bowes et al., 2009; Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993; Finkelhor et al., 2009; Hamby et al., 2010; Fisher et al., 2015). They are also likely to engage in risky sexual behaviour, drug and alcohol use, and violence that would increase their likelihood of experiencing sexual assault, exposure to sexually transmitted diseases, and witnessing violence (Lalor & McElvaney, 2010; Thornberry et al., 2010; Widom & Maxfield, 1996; Widom et al., 2006). Second, maltreatment is associated with various life outcomes that would increase a person’s exposure to stressful conditions including teen parenthood (Widom & Kuhns, 1996), poor educational attainment and unemployment (Gilbert et al., 2009), and poverty (Sedlak et al., 2010). Under conditions of on-going adversity, safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships may provide women with needed support to cope with their circumstances.

Although access to social support is hypothesized to promote good physical or mental health among individuals who have a history of maltreatment (Cicchetti, 2013), relatively few studies have explicitly tested this hypothesis. Two studies used data from the Midlife in the United States Study to test whether socially supportive relationships in adulthood mediated or moderated effects of retrospectively-reported physical abuse on adult health. While one found that psychosocial resources (e.g., a sense of personal control and the ability to form and maintain intimate relationships) mediated the relationship between childhood physical abuse and self-reported health (Shaw & Krause, 2002), the other was consistent with a “main effects” model of social support; receiving higher (versus lower) levels of emotional support was associated with better self-reported physical health for all adults, not just for those who reported childhood physical abuse (Pitzer & Fingerman, 2010). However, another study found that adults who were psychiatrically healthy despite their childhood history of abuse were more likely than similarly healthy, non-abused adults to have experienced stable romantic relationships in adulthood, suggesting that the protective effects of stable relationships were more pronounced for those with versus those without a history of abuse (Collishaw et al., 2007). Moreover, the quality of adult friendships and the stability of adult romantic relationships differentiated “resilient” versus “non-resilient” adults (Collishaw et al., 2007).

In a previous study, we found that the presence of safe and nurturing relationships differentiated women who broke the cycle of violence from women who had childhood histories of maltreatment and whose own children were victims of maltreatment (Jaffee et al., 2013). We now extend that investigation to test whether women who have safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships have better mental health (e.g., major depressive, generalized anxiety and psychosis spectrum disorders), physical health (e.g., general health, sleep problems and limited physical activity) and fewer health risk behaviours (e.g., antisocial behaviours, substance use problems, and food insecurity) than women who lack such relationships. Consistent with the stress-buffering hypothesis, we predict that the beneficial effects of safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships on health will be stronger for women with versus women without a childhood history of maltreatment. We also expect that a cumulative effect of having safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships on health related outcomes and behaviours will be more pronounced than the effects of any specific component of these positive relationships.

Methods

Sample

Participants were mothers involved in the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, which tracks the development of a nationally representative birth cohort of British children. The sample was drawn from a larger birth register of twins born in England and Wales in 1994–1995 (Moffitt & the E-Risk team, 2002). The original sample (n=1,116 families) was constructed using a high-risk stratification sampling procedure to represent the UK population of mothers having children in the 1990’s by oversampling women who gave birth to their first child when 20-years-old or younger to replace those selectively lost to the register due to nonresponse and undersampling older, well-educated mothers having twins via assisted reproduction. Women were, on average, 33 years old at the initial assessment (thereafter referred to as T1). Three additional assessments were undertaken when they were, on average, 35, 38 and 40 years old (thereafter referred to as T2, T3 and T4). The attrition was minimal and the T4 assessment included 96% of the women. This study sample encompasses 914 women involved in an intimate relationship at some point by T3. Participants gave written informed consent after a complete description of the study. The Joint South London and Maudsley and the Institute of Psychiatry Research Ethics Committee approved each phase of the study.

At follow up, the study sample represented the full range of socioeconomic conditions in the UK, as reflected in the families’ distribution on a neighborhood-level socioeconomic index (ACORN [A Classification of Residential Neighbourhoods], developed by CACI Inc. for commercial use in Great Britain) (Odgers et al., 2012a). ACORN uses census and other survey-based geodemographic discriminators to classify enumeration districts (~150 households) into socioeconomic groups ranging from “wealthy achievers” (Category 1) with high incomes, large single-family houses, and access to many amenities, to “hard pressed” neighborhoods (Category 5) dominated by government-subsidized housing estates, low incomes, high unemployment, and single parents. ACORN classifications were geocoded to match the location of each E-Risk study family’s home (Odgers et al., 2012b). E-Risk families’ ACORN distribution closely matches that of households nation-wide: 25.6% of E-Risk families live in “wealthy achiever” neighborhoods compared to 25.3% nation-wide; 5.3% vs. 11.6% live in “urban prosperity” neighborhoods; 29.6% vs. 26.9% live in “comfortably off” neighborhoods; 13.4% vs. 13.9% live in “moderate means” neighborhoods; and 26.1% vs. 20.7% live in “hard-pressed” neighborhoods. E-Risk underrepresents “urban prosperity” neighborhoods because such households are likely to be childless.

Measures

History of childhood maltreatment

Women’s history of childhood maltreatment was retrospectively assessed at T4 using the short form of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al., 2003). This instrument enquires about five categories of childhood maltreatment: emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and also emotional and physical neglect. The validity of the original instrument and a brief version has been previously demonstrated in clinical and community samples (Bernstein et al., 2003; Bernstein & Fink, 1998). We used the score classification evaluated and recommended by the CTQ manual (Bernstein & Fink, 1998) and considered a specific category of maltreatment present if the mothers had a moderate to severe score. Subsequently, we derived a cumulative exposure index for each woman by counting the number of maltreatment categories present: 77.2% of women experienced no maltreatment, 16.4% experienced moderate maltreatment (1–2 categories), and 6.4% experienced severe maltreatment (3 categories or more). Using the manual’s recommended classification scores (Bernstein & Fink, 1998), we identified 202 women (22.8%) in this study sample with a history of at least one type of maltreatment as ‘any maltreatment’.

Socioeconomic deprivation

Socioeconomic deprivation was constructed from a standardized composite of each family’s income, education and occupational status (coded according to the Standard Occupational Classification) collected at T1 (Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, 1991; Trzesniewski et al., 2006). These indicators were highly correlated (correlations ranged from .57 to .67, ps<.05) and loaded significantly onto one latent factor (factor loadings were .80, .70 and .83 for income, education and social class, respectively). The scores were standardized and averaged. In this study sample, 238 women (26.0%) were considered as living in socioeconomically deprived conditions.

Mental health problems

Major Depressive disorders and generalized anxiety disorder were diagnosed using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS; Robins et al., 1995) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV criteria (DSM-IV; APA, 1994). We enquired about women’s history of depression at T1 and T3 and their history of generalized anxiety disorder at T4. Psychosis-spectrum disorder was also assessed using the DIS, which inquires about characteristic symptoms: hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, grossly disorganized or catatonic behaviour and negative symptoms (avolition, flat affect, alogia). Our interview ruled out symptoms with plausible explanations and symptoms occurring solely under the influence of alcohol or drugs. Following DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, women were classified as having a psychosis-spectrum disorder given the presence of hallucinations plus at least two other symptoms, as well as evidence of social, occupational, or self-care dysfunction (Poulton et al., 2000). Our goal was not to diagnose clinical schizophrenia, but to identify women who endorse impairing psychotic-like experiences and beliefs, given compelling evidence that psychosis-spectrum syndromes in the general population are more prevalent than registered treated cases of schizophrenia (Myin-Germeys, Krabbendam, & van Os, 2003).

Physical health problems

Overall health at T4 was measured with the Short Form-12 physical health scale (Gandek et al., 1998). Participants rated their overall health on a scale from poor to excellent (0=poor, 1 =fair, 2=good, 3=very good, 4=excellent). Participants also reported whether their physical health limited their ability to engage in moderately strenuous (e.g., moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner) or more intensely strenuous activities (e.g., climbing several flights of stairs) (0 = no, 1 = limited a little, 2 = limited a lot). Participants reported on their symptoms of sleep problems in a standardized interview at T4 (Gregory et al., 2012). A diagnosis of sleep problems was made based on the criteria outlined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (APA, 1994). Specifically, women were asked if they experienced difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, or problems waking too early. Answers were provided on a 5-point scale (0=none; 1=mild; 2=moderate; 3=severe; 4=very severe). We also asked women “how much do sleep problems interfere with your daily functioning?” (1=not at all to 5=very much). If women reported any sleep difficulty that they considered “severe or “very severe” and reported an interference score ≥ 3, they were considered to have sleep problems.

Health risks and health risk behaviours

History of antisocial behaviours was assessed at T1 with the Young Adult Self-Report (Achenbach, 1997), modified to obtain lifetime data and supplemented with questions from the DIS (Robins et al., 1995) to assess lifetime presence of six DSM-IV symptoms of Conduct Disorder and Antisocial Personality Disorder (e.g., deceitfulness, aggressiveness; APA, 1994). Participants rated each question as being “not true”, “somewhat or sometimes true” or “very or often true” at T1. Items were summed (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83).

Substance abuse was derived from the short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Selzer et al., 1975) and the Drug Abuse Screening Test (Skinner, 1983). Participants rated each question as being “not true”, “somewhat or sometimes true” or “very or often true” at T1. Items were summed (Cronbach’s alpha = .73).

The family’s food insecurity situation was assessed at T2 and T3 using a 7-item scale developed by the US Department of Agriculture and administered to participants (Cronbach’s alpha = .85 at T2 and .87 at T3) (Bickel et al., 2000). This scale distinguishes families that are (1) food-secure (i.e., there is no evidence of food insecurity; 0–1 positive responses), (2) food-insecure without hunger (i.e., food insecurity is evident, but there is no reduction in the family’s food intake; 2–4 positive responses), or (3) food-insecure with hunger (i.e., food intake is reduced; 5–7 positive responses). In our study, fewer than 2% of families experienced food insecurity with hunger, so we combined them with the other food-insecure families (Melchior et al., 2009). Inadequate access to food was deemed a health risk.

Protective Factors

We examined romantic relationship safety by asking participants 12 questions, nine of which were taken from the Conflict Tactics Scale-Form R (Straus, 1990), plus three items describing other physically abusive behaviours [pushed/grabbed/shoved; choked/strangled; threatened with knife/gun]. Participants responded “not true” or “true” to each item. Questions regarding partner violence were asked at T1, covering the period of 5 years since the twins’ birth (Cronbach’s alpha = .80) and again at T3, five years later (Cronbach’s alpha = .98) (Jaffee et al., 2002). We identified 606 women who were in safe relationships at both time points (66.3%).

Emotional intimacy with women’s current partner was assessed at T1 with 14 items (including the questions “We feel very close to each other”, “I feel that I can trust my partner completely”, “We discuss problems and feel good about the solutions”) rated on a scale from 0 (No) to 2 (Yes, true) (Fincham, 1998). Responses to these items were summed (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89). We split this composite score into tertiles. We identified 211 women who reported having high levels of emotional intimacy with their partner (23.1%).

We assessed three components of social support from partners, friends, or family at T1: (1) financial support (whether financial support was provided in times of need); (2) support with twins (how much help was provided with taking care of the twins in times of need); and (3) emotional support (how much support was provided when the mother was upset, worried or needed someone to talk to) (Simons & Johnson, 1996). Participants rated how true each of 12 social support items was of their situation (0, ‘not true’; 1 ‘somewhat true’; 2 ‘yes, true’). Scores were summed (Cronbach’s alpha=0.76) and we split this scale into tertiles. We identified 293 women who reported having high levels of social support (32.1%) in this study sample.

Cumulative Protective Factors

We created a cumulative measure of protective factors by summing the three factors described above (romantic relationship safety; emotional intimacy; and social support). In the study sample, 20% had no protective factors (n=181), 46% had one factor (n=408), 26% had two factors (n=227), and 8% had three factors (n=69). Because relatively few women had all three protective factors, they were combined with the group who had two factors. Women with and without a childhood history of maltreatment were not equally likely to be characterized by these protective factors. Romantic relationship safety more commonly characterized women who did not have a childhood history of maltreatment (72% versus 48% with a childhood history of maltreatment). Similarly, 25% of women without childhood histories of maltreatment reported high levels of emotional intimacy with a partner compared with 14% of women who had childhood histories of maltreatment. Finally, 36% of women without childhood histories of maltreatment reported high levels of social support compared with 17% of women who had childhood histories of maltreatment.

Statistical analyses

First, we examined the associations between women’s history of maltreatment with their mental and physical health problems, and also with their health risk behaviours, using a series of logistic and linear regression analyses. All analyses controlled for women’s socioeconomic status. Second, we tested the protective effect of safe and nurturing relationships on women’s mental and physical health problems and health risk behaviours by including an interactive term between a history of childhood maltreatment and the cumulative protective factors measure. We conducted all analyses using STATA 13.1 (Stata Corp., 2013).

Results

The odds of having mental health problems, physical health problems, or of engaging in health risk behaviours were 2 to 4 times greater for women with a history of childhood maltreatment compared to women without a history of maltreatment (Table 1). Furthermore, for outcomes that were measured continuously, effect size (Cohen’s d) differences between women who did and did not have a history of maltreatment were small to moderate in size (general health: d=−0.28 [95% CI −0.43, −0.12]; functional limitations: d=0.33, [95% CI 0.17, 0.48]; substance use problems: d=0.47 [95% CI 0.31, 0.63]; antisocial behaviour: d=0.55, [95% CI 0.39, 0.71]).

Table 1.

Association between women’s history of child maltreatment and health outcomes in adulthood

| Women’s history of child maltreatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=885) | Never 77.2% (N=683) | Any 22.8% (N=202) | |||||

| Women’s health outcomes | % (N) or M (SD) | % (N) or M (SD) | % (N) or M (SD) | OR/beta | (95% CI) | p | |

| Mental health | |||||||

| Major depressive disorder % | 43.5 (384) | 37.7 (257) | 63.2 (127) | 2.67 | (1.92, 3.72) | <.001 | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder % | 6.6 (58) | 4.5 (31) | 13.4 (27) | 3.00 | (1.73, 5.22) | <.001 | |

| Psychosis spectrum disorder % | 4.6 (40) | 2.5 (17) | 11.6 (23) | 4.34 | (2.24, 8.40) | <.001 | |

| Physical health | |||||||

| Good general health | 2.5 (0.98) | 2.6 (0.94) | 2.3 (1.08) | −0.19 | (−0.34, −0.04) | 0.014 | |

| Sleep problems % | 17.5 (155) | 14.1 (96) | 29.2 (59) | 2.26 | (1.55, 3.31) | <.001 | |

| Limits to moderate activity | 0.3 (0.85) | 0.3 (0.75) | 0.6 (1.11) | 0.23 | (0.10, 0.36) | 0.001 | |

| Health risk behaviours | |||||||

| Antisocial behaviour | 0.6 (1.12) | 0.5 (0.95) | 1.1 (1.48) | 0.54 | (0.37, 0.71) | <.001 | |

| Substance use problems | 0.8 (1.94) | 0.5 (1.44) | 1.4 (2.98) | 0.79 | (0.50, 1.09) | <.001 | |

| Ever food insecurity % | 10.4 (91) | 7.1 (48) | 21.7 (43) | 3.02 | (1.88, 4.83) | <.001 | |

Abbreviations: N, number; M, mean; SD, standard deviation; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Notes: All analyses controlled for women’s socioeconomic status.

As shown in Table 2, of the three component protective factor, romantic relationship safety was the most consistent correlate of good mental health and physical health as well as low levels of health risk behaviours. Having higher versus lower levels of emotional intimacy with a partner was associated with lower rates of depression and food insecurity. Having high versus lower levels of social support was associated with better overall health, fewer functional limitations, and fewer antisocial behaviours.

Table 2.

Associations between safe and nurturing relationships with health outcomes in adulthood

| Absence of partner violence | Emotional intimacy | Social support | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | Low or Moderate | High | Low or Moderate | High | ||||

| Women’s health outcomes | % (N) or M (SD) | % (N) or M (SD) | p | % (N) or M (SD) | % (N) or M (SD) | p | % (N) or M (SD) | % (N) or M (SD) | p |

| Mental health | |||||||||

| Major depressive disorder % | 58.4 (180) | 35.8 (216) | <.001 | 45.2 (317) | 37.6 (79) | 0.039 | 45.7 (283) | 38.7 (113) | 0.102 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder % | 11.9 (36) | 3.9 (23) | <.001 | 7.4 (51) | 3.9 (8) | 0.063 | 7.2 (44) | 5.2 (15) | 0.396 |

| Psychosis spectrum disorder % | 8.6 (26) | 2.8 (17) | 0.004 | 5.2 (36) | 3.3 (7) | 0.201 | 5.5 (34) | 3.1 (9) | 0.227 |

| Physical health | |||||||||

| Good general health | 2.4 (1.02) | 2.6 (0.96) | 0.027 | 2.5 (0.97) | 2.6 (1.03) | 0.188 | 2.4 (1.01) | 2.7 (0.90) | <.001 |

| Sleep problems % | 21.2 (64) | 15.5 (92) | 0.193 | 18.0 (124) | 15.5 (32) | 0.350 | 19.2 (117) | 13.6 (39) | 0.115 |

| Limits moderate activity | 0.4 (0.96) | 0.3 (0.80) | 0.352 | 0.4 (0.87) | 0.3 (0.81) | 0.696 | 0.4 (0.92) | 0.2 (0.69) | 0.021 |

| Health risk behaviours | |||||||||

| Antisocial behaviour | 1.0 (1.43) | 0.4 (0.86) | <.001 | 0.6 (1.09) | 0.6 (1.22) | 0.737 | 0.7 (1.20) | 0.5 (0.91) | 0.030 |

| Substance use problems | 1.2 (2.43) | 0.5 (1.61) | <.001 | 0.7 (1.95) | 0.8 (1.96) | 0.898 | 0.8 (2.20) | 0.6 (1.23) | 0.205 |

| Ever food insecurity % | 15.8 (48) | 7.6 (45) | 0.017 | 11.4 (79) | 6.7 (14) | 0.024 | 11.6 (71) | 7.6 (22) | 0.312 |

Abbreviations: N, number; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Notes: All analyses controlled for women’s socioeconomic status.

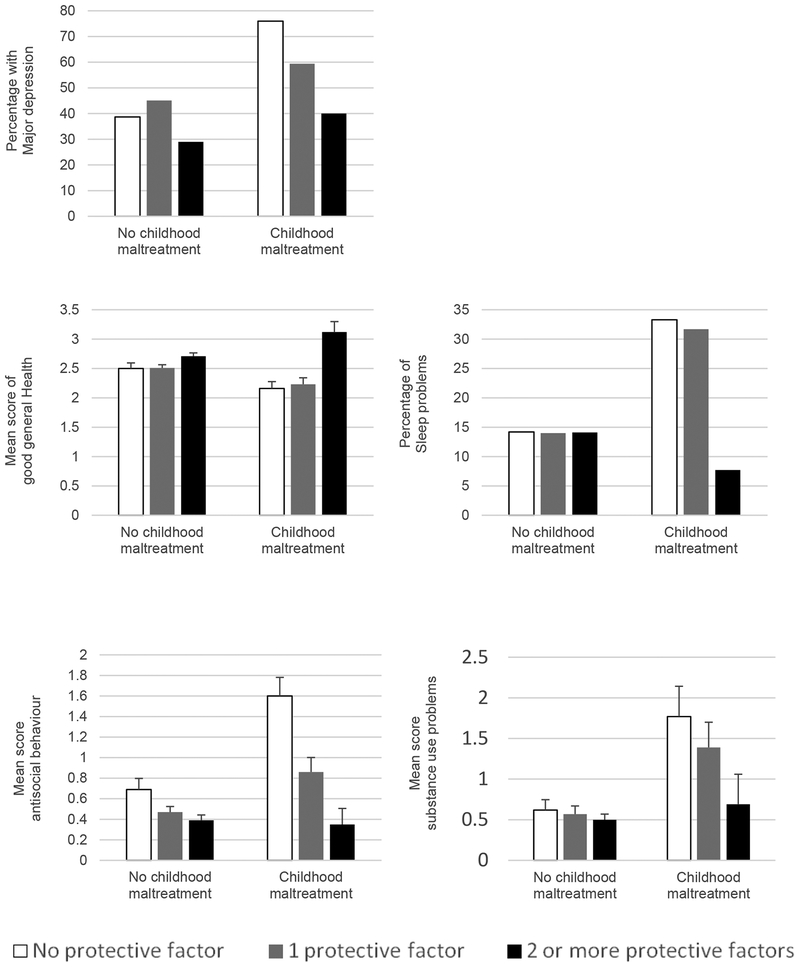

The cumulative protective factors measure comprising safe and nurturing relationships moderated the effect of a history of childhood maltreatment on women’s health and health risk behaviours (Table 3). Having safe and nurturing relationships in adulthood was associated with reductions in rates of depressive episodes among women who reported a history of child maltreatment and with better overall health, lower rates of sleep problems and decreases in antisocial behaviour. There is no specific component of the cumulative protective factor that drove the moderator effect (Table 3).

Table 3.

Moderating effect of safe and nurturing relationships on the association between women’s history of child maltreatment and health outcomes in adulthood

| Absence of partner violence | Emotional intimacy | Social support | Cumulative effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women’s health outcomes | coefficients | p | coefficients | p | coefficients | p | coefficients | p |

| Mental health | ||||||||

| Major Depressive disorder | −0.58 | 0.100 | 0.75 | 0.538 | 0.96 | 0.921 | −0.64 | 0.018 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | −0.17 | 0.776 | 0.78 | 0.361 | 0.67 | 0.306 | −0.03 | 0.953 |

| Psychosis spectrum disorder | −0.10 | 0.886 | 0.25 | 0.809 | 0.23 | 0.806 | −0.79 | 0.275 |

| Physical health | ||||||||

| Good general health | 0.08 | 0.594 | 0.50 | 0.018 | 0.26 | 0.180 | 0.33 | 0.005 |

| Sleep problems | −0.41 | 0.313 | −0.70 | 0.228 | −0.49 | 0.345 | −0.66 | 0.048 |

| Limits moderate activity | −0.07 | 0.614 | 0.08 | 0.653 | −0.29 | 0.087 | −0.08 | 0.417 |

| Health risk behaviours | ||||||||

| Antisocial behaviour | −0.44 | 0.011 | −0.53 | 0.027 | −0.32 | 0.148 | −0.49 | <.001 |

| Substance use problems | −0.64 | 0.038 | 0.01 | 0.990 | −0.29 | 0.444 | −0.46 | 0.051 |

| Ever food insecurity | −0.20 | 0.616 | 0.30 | 0.555 | −0.16 | 0.770 | −0.23 | 0.569 |

Notes: All analyses controlled for women’s socioeconomic status.

Coefficients are shown as those of interactive term between protective measure and adult health outcome.

Furthermore, the cumulative measure was marginally associated with reductions in substance use problems among women who experienced child maltreatment. As illustrated in Figures 1 to 5, an accumulation of safe, supportive, nurturing factors was associated with reductions in women’s mental and physical health problems as well as their health behaviours if they had a history of childhood maltreatment. In contrast, among women who lacked a childhood history of maltreatment, rates of poor mental health, physical health, and health behaviours were low and not associated with cumulative protective factors.

Figure 1.

Buffering effect of the cumulative protective measure of safe, supportive and nurturing relationships for women with a history of maltreatment on later health outcomes

Discussion

Women who had a childhood history of maltreatment were at elevated risk for poor mental, physical, and behavioural health problems in adulthood compared with women who did not have a childhood history of maltreatment. However, women who were characterized by safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships were buffered from the adverse effects of a childhood history of abuse with respect to depression, general health, sleep problems, and antisocial behaviour. Similar patterns of results were observed for substance use, but only at trend levels of significance. In contrast, women who did not experience childhood abuse had relatively low rates of mental, physical, and behavioural health problems and these did not vary as a function of the quality of their interpersonal relationships.

Women’s interpersonal relationships were truly protective – in the sense that they mostly mattered for women who had histories of abuse – rather than generally promotive of positive health outcomes. This finding is consistent with research in the social support literature which distinguishes stress buffering from main effects of socially supportive relationships (Cohen & Wills, 1985). This literature suggests that stress buffering is most likely to be observed when individuals appraise their circumstances as stressful, but also perceive that someone is on hand to provide needed instrumental or emotional support. As described above, there is ample evidence to suggest that women with childhood histories of maltreatment experience more stressful life events in adulthood than women without such histories. Under these circumstances, the presence of a warm and trusted partner as well as the perception that friends or family can provide instrumental or emotional support may alter women’s appraisals of their circumstances (e.g., what initially appeared stressful may not, once it has been discussed with a partner, friend, or family member) or may offer solutions that relieve the stress, both of which could contribute to better mental, physical, or behavioural health (Cohen & Wills, 1985). In contrast, a measure that captures whether (and to what extent) women feel socially isolated versus socially integrated within a network may be associated with positive health outcomes regardless of a woman’s history of maltreatment (Cohen & Wills, 1985).

Although we derived a cumulative protective factors measure, some of the buffering effects we observed appeared to be driven by specific factors. For example, romantic relationship safety alone appeared to improve substance use outcomes for women with childhood histories of maltreatment. In contrast, high levels of emotional intimacy were related to reports of better (versus poorer) general health for women with childhood histories of maltreatment. Interestingly, although the cumulative effect of romantic relationship safety, social support, and emotional intimacy buffered women from the adverse effects of childhood maltreatment on risk for depression, none of the individual factors were statistically significant predictors.

Safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships did not buffer women with histories of abuse from less common mental and physical health problems, such as psychosis spectrum symptoms, or functional impairments in physical health. Given the relatively low base rates of these problems, it is possible that our analyses were under-powered to detect buffering effects. Additionally, it is possible that these problems are sufficiently severe that they require more than what violence-free, supportive, and emotionally-intimate relationships can offer. Although a history of abuse and neglect was also associated with food insecurity, it is likely that money, rather than safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships, buffers women from experiencing that outcome.

Limitations

The current study contributes to a small literature that shows that socially supportive relationships can mitigate the adverse effects of a history of maltreatment on adult health. Nevertheless, the study was characterized by various limitations. First, mothers reported retrospectively on their own history of maltreatment. Individuals who provide retrospective reports have a tendency, on the one hand, to forget past events and, on the other hand, to recall past events in ways that are congruent with their current mood or that make sense of their current circumstances (Reuben et al., 2016; Widom & Shepherd, 1996). However, retrospective reports as measured by the CTQ correspond highly with reports of an individual’s abuse history based on other sources (Bernstein et al., 1997).

Second cumulative measures are criticized for making arbitrary designations of risk (or protection). This was true of the measure of emotional intimacy and the social support measure, both of which were dichotomized at the top tertile, consistent with other reports from this sample (Jaffee et al., 2013; Jaffee et al., 2007). Research on protective effects is also criticized for equating the absence of risk with the presence of protection, as might have been the case with the measure of romantic relationship safety. Nevertheless, cumulative risk or protection measures are parsimonious and consistent with many theoretical models, such as bioecological or allostatic load models (Brody et al., 2013; Evans et al., 2013).

In our previous work, we showed that safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships differentiated mothers who broke the cycle of abuse and neglect in their own families from those who did not (Jaffee et al., 2013). One interpretation of these findings is that children are at low risk of being maltreated by biological or step-fathers if those men are nurturing and non-abusive in their intimate relationships with the children’s mothers. The current findings suggest a second possibility: that experiencing safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships makes mothers themselves less likely to perpetrate abuse and neglect by improving their mental and behavioural health. Although both of these interpretations assume that effects of safe, supportive, and nurturing relationships are causal, experimental or quasi-experimental designs are needed to ascertain whether this is true.

Conclusions

Women who have histories of abuse or neglect are at elevated risk for mental and physical health problems. The growing interest in measuring social determinants of health at the point of primary care (Alley et al., 2016) may mean that adult women will start to be screened systematically for childhood maltreatment and adult domestic violence. The identification of women who are at the greatest risk of poor health and the use of information about their social and socioeconomic circumstances to effectively target services and clinical care could be a positive development. As noted in a recent editorial however, responsible screening for social determinants of health means that practices must have the infrastructure and knowledge to link patients to services and must train physicians to be comfortable and sensitive when asking questions about family violence, housing, or food insecurity (Garg et al., 2016). Many practices lack the resources to devote to this effort. Nevertheless, there are models of successful screening and integrated service delivery in pediatric primary care with, for example, the Safe Environments for Every Kid program (SEEK; Dubowitz et al., 2009). For women who are already experiencing mental and physical health problems, standard pharmacological treatments for problems like depression or poor sleep could be extended to include couples therapy to improve communication and warmth with a partner. Our findings emphasize that social determinants of health not only confer risk for poor health, but if a woman’s current social circumstances are sufficiently positive, they can also promote good health, particularly in the face of past adversity.

Acknowledgements

The E-Risk Study is funded by the Medical Research Council (UKMRC G9806489 and G1002190). Additional support was provided by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant HD077482), the Centers for Disease Control, and by the Jacobs Foundation. Ryu Takizawa was a Newton International Fellow jointly funded by the Royal Society and the British Academy. Louise Arseneault is the Mental Health Leadership Fellow for the Economic and Social Research Council in the UK. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the other funding organizations.

We are grateful to the study mothers and fathers, the twins, and the twins’ teachers for their participation. Our thanks to Terrie E. Moffitt and Avshalom Caspi the founders of the E-Risk Study, to Michael Rutter and Robert Plomin, to Thomas Achenbach for kind permission to adapt the Child Behavior Checklist, CACI, Inc., and to members of the E-Risk team for their dedication, hard work, and insights.

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Ryu Takizawa had full access to all of the data in this study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data, the accuracy of the data analysis, and the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None.

Conflict of interest: None

References

- Achenbach TM (1997). Manual for the Young Adult Self-Report and Young Adult Behavior Checklist. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry: Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, Mota NP, Dasiewicz P, MacMillan HL, Sareen J (2012). Physical punishment and mental disorders: Results from a nationally representative US sample. Pediatrics 130, 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM (2016). Accountable health communities — Addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. New England Journal of Medicine 374, 8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of MentalDisorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing Inc: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D (2002). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology 31, 285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L (1997). Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 36, 340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D, Fink L (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Manual. The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect 27, 169–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J (2000). Guide to Measuring Household Food Insecurity: Revised 2000 United States Department of Agriculture Food & Nutrition Service. Office of Research and Analysis: Alexandria, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Bowes L, Arseneault L, Maughan B, Taylor A, Caspi A, Moffitt TE (2009). School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children’s bullying involvement: A nationally representative longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 48, 545–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Chen YF, Kogan SM, Evans GW, Beach SR, Windle M, Simons RL, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Philibert RA (2013). Cumulative socioeconomic status risk, allostatic load, and adjustment: A prospective latent profile analysis with contextual and genetic protective factors. Developmental Psychology 49, 913–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014). Essentials for Childhood: Steps to create safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/essentials_for_childhood_framework.pdf

- Cicchetti D (2013). Annual Research Review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children--past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry 54, 402–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M (1993). Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry 56, 96–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Brown J, Smaile E (2001). Child abuse and neglect and the development of mental disorders in the general population. Developmental Psychopathology 13, 981–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin 98, 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, Rutter M, Shearer C, Maughan B (2007). Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect 31, 211–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Pariante CM, Poulton R, Caspi A (2009). Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: Depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 163, 1135–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williams JE, Chapman DP, Anda RF (2004). Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: Adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation 110, 1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J (2009). Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: The Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) model. Pediatrics 123, 858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Li DP, Whipple SS (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin 139, 1342–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD (1998). Child development and marital relations. Child Development 69, 543–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, Hamby SL (2009). Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics 124, 1411–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher HL, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wertz J, Gray R, Newbury J, Ambler A, Zavos H, Danese A, Mill J, Odgers CL, Pariante C, Wong CCY, Arseneault L (2015). Measuring adolescents’ exposure to victimization: The Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study. Developmental Psychopathology 27, 1399–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplege A, Prieto L, Sullivan M (1998). Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 51, 1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Boynton-Jarrett R, Dworkin PH (2016). Avoiding the unintended consequences of screening for social determinants of health. JAMA 316, 813–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 373, 68–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, Moffitt TE, Ambler A, Arseneault L, Houts RM, Caspi A (2012). Maternal insomnia and children’s family socialization environments. Sleep 35, 579–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R (2010). The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimizations in a nationally representative survey of youth. Child Abuse & Neglect 34, 734–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Hong S, Klika JB, Herrenkohl RC, Russo MJ (2013). Developmental Impacts of Child Abuse and Neglect Related to Adult Mental Health, Substance Use, and Physical Health. Journal of Family Violence 28, 191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish L, Kobayashi I, Delahanty DL (2010). Long-term physical health consequences of childhood sexual abuse: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 35, 450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving SM, Ferraro KF (2006). Reports of abusive experiences during childhood and adult health ratings: Personal control as a pathway? Journal of Aging & Health 18, 458–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Bowes L, Ouellet-Morin I, Fisher HL, Moffitt TE, Merrick MT, Arseneault L (2013). Safe, stable, nurturing relationships break the intergenerational cycle of abuse: A prospective nationally representative cohort of children in the United Kingdom. Journal of Adolescent Health 53, S4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Polo-Tomas M, Taylor A (2007). Individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children: A cumulative stressors model. Child Abuse & Neglect 31, 231–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Arseneault L (2002). Influence of adult domestic violence on children’s internalizing and externalizing problems: An environmentally informative twin study. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry 41, 1095–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalor K, McElvaney R (2010). Child sexual abuse, links to later sexual exploitation/high-risk sexual behavior, and prevention/treatment programs. Trauma Violence Abuse 11, 159–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Widom CS (1996). The cycle of violence. Revisited 6 years later. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medication 150, 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior M, Caspi A, Howard LM, Ambler AP, Bolton H, Mountain N, Moffitt TE (2009). Mental health context of food insecurity: A representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics 124, e564–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, Leeb RT, Lee RD (2013). Examining the role of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships in the intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment--Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Adolescent Health 53, S1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midei AJ, Matthews KA, Chang YF, Bromberger JT (2013). Childhood physical abuse is associated with incident metabolic syndrome in mid-life women. Health Psychology 32, 121–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, The E-Risk team (2002). Teen-aged mothers in contemporary Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 43, 727–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Krabbendam L, van Os J (2003). Continuity of psychotic symptoms in the community. Current Opinions in Psychiatry 16, 443–449. [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Zeller MH, Trickett PK, Putnam FW (2007). Obesity risk for female victims of childhood sexual abuse: A prospective study. Pediatrics 120, e61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Caspi A, Bates CJ, Sampson RJ, Moffitt TE (2012b). Systematic social observation of children’s neighborhoods using Google Street View: A reliable and cost-effective method. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 53, 1009–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Caspi A, Russell MA, Sampson RJ, Arseneault L, Moffitt TE (2012a). Supportive parenting mediates neighborhood socioeconomic disparities in children’s antisocial behavior from ages 5 to 12. Developmental Psychopathology 24, 705–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (1991). Standard Occupational Classification (Vols. 1–3). London: HMSO [Google Scholar]

- Pitzer LM, Fingerman KL (2010). Psychosocial resources and associations between childhood physical abuse and adult well-being. Journal of Gerontology series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 65, 425–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulton R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, Murray R, Harrington HL (2000). Children’s self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorders: A 15-year longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry 57, 1053–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Belsky DW, Harrington H, Schroeder F, Hogan S, Ramrakha S, Poulton R, Danese A (2016). Lest we forget: comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 57, 1103–1112. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz KK, Compton W (1995). Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. Washington University School of Medicine: St. Louis, MO. [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Smith DA, Ellis PM (2012). A population study of childhood maltreatment and asthma diagnosis: Differential associations between child protection database versus retrospective self-reported data. Psychosomatic Medicine 74, 817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Smith DR, Ellis PM (2010). Prospectively ascertained child maltreatment and its association with DSM-IV mental disorders in young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry 67, 712–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L (1975). A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST). Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 36, 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, Li S (2010). Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4): Report to Congress, Executive Summary. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BA, Krause N (2002). Exposure to physical violence during childhood, aging, and health. Journal of Aging and Health 14, 467–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Johnson C (1996). The impact of marital and social network support on quality of parenting In Pierce GR, Sarason BR, & Sarason IG (Eds.) Handbook of Social Support and the Family. (pp. 269–287). Springer: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA (1983). The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviours 7, 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp (2013). Stata Statistical Software: Release 13.1. StataCorp LP: College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (1990). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales In Straus MA, & Gelles RJ(Eds.) Physical violence in American families: Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. (pp. 403–424). Transcation Press: New Brunswick, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Henry KL, Ireland TO, Smith CA (2010). The causal impact of childhood-limited maltreatment and adolescent maltreatment on early adult adjustment. Journal of Adolescent Health 46, 359–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski KH, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Maughan B (2006). Revisiting the association between reading achievement and antisocial behavior: New evidence of an environmental explanation from a twin study. Child Development 77, 72–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegman HL, Stetler C (2009). A meta-analytic review of the effects of childhood abuse on medical outcomes in adulthood. Psychosomatic Medicine 71, 805–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1999). Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. American Journal of Psychiatry 156, 1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Bentley T, Johnson MS (2012). A prospective investigation of physical health outcomes in abused and neglected children: New findings from a 30-year follow-up. American Journal of Public Health 102, 1135–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Paris J (2009). A prospective investigation of borderline personality disorder in abused and neglected children followed up into adulthood. Journal of Personality Disorders 23, 433–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ (2007). A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry 64, 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Ireland T, Glynn PJ (1995). Alcohol abuse in abused and neglected children followed-up: Are they at increased risk? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 56, 207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Kuhns JB (1996). Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health 86, 1607–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Maxfield MG (1996). A prospective examination of risk for violence among abused and neglected children. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 794, 224–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Schuck AM, White HR (2006). An examination of pathways from childhood victimization to violence: The role of early aggression and problematic alcohol use. Violence Victims 21, 675–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Shephard RL (1996). Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization: Part 1. Childhood physical abuse. Psychological Assessment 8, 412–421. [Google Scholar]