Abstract

Introduction

The development of targeted drug delivery systems is a rapidly growing area in the field of nanomedicine.

Methods

We report herein on optimizing the targeting efficiency of a lipid nanoparticle (LNP) by manipulating the acid dissociation constant (pKa) value of its membrane, which reflects its ionization status. Instead of changing the chemical structure of the lipids to achieve this, we used a mixture of two types of pH-sensitive cationic lipids that show different pKa values in a single LNP. We mixed various ratios of YSK05 and YSK12-C4 lipids, which have pKa values of 6.50 and 8.00, respectively, in one formulation (referred to as YSK05/12-LNP).

Results

The pKa of the YSK05/12-LNP was dependent not only on the molar ratio of each lipid but also on the individual contribution of each lipid to the final pKa (the YSK12-C4 lipid showed a higher contribution). Furthermore, we succeeded in targeting and delivering short interfering RNA to liver sinusoidal endothelial cells using one of the YSK05/12-LNPs which showed an optimum pKa value of 7.15 and an appropriate ionization status (~36% cationic charge) to permit the particles to be taken up by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells.

Conclusion

This strategy has the potential for preparing custom LNPs with endless varieties of structures and final pKa values, and would have poten tial applications in drug delivery and ionic-based tissue targeting.

Keywords: acid dissociation constant, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, physical targeting, short interfering RNA

Introduction

Targeted delivery systems are promising tools for the specific delivery of therapeutic cargos into tissues of interest, with the objective of improving therapeutic outcomes while minimizing adverse effects on nontargeted tissues. Examples of targeting strategies include 1) passive targeting, in which delivery systems accumulate at the target site through the blood circulation;1,2 2) active targeting, in which delivery systems are directed to specific sites through targeting moieties attached to their surface (eg, ligands or antibodies);3,4 and 3) physical targeting, in which delivery systems are targeted at certain environments with special physical characteristics such as pH,5 temperature,6 or ionic property.7,8 The objective of the present study was to investigate the physical targeting of a delivery system, based on the ionic charge and electrostatic interactions of the particle with cellular membranes.

Gene therapy using short interfering RNA (siRNA), a short sequence of nucleotides that can silence genes of interest,9,10 can be applied to the treatment of a wide variety of diseases related to genetic disturbances, such as cancer. However, the physical properties of siRNAs hinder their entry into cells: high molecular weight (~13,000 Da), hydrophilic nature, and highly anionic charge. Moreover, siRNAs are not stable in an in vivo environment. Therefore, an effective and safe siRNA drug delivery system is required.

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have proved to be efficient systems for delivering siRNA into body tissues.11–15 We assumed that by modifying the acid dissociation constant (pKa) value of the LNP membrane, which reflects its ionization status, it might electrostatically interact with specific tissue membranes. Instead of changing the chemical structure of the lipids to manipulate the pKa value of the LNP membrane, a method that is time-consuming and labor-intensive and results in limited pKa adjustments, we mixed lipids having different pKa values at different molar ratios in the LNP formulation, a method which minimized time and effort and allowed us to precisely adjust the final pKa for achieving ionic-based tissue targeting.

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) are an example of a tissue that would be a suitable model for our study and could be targeted based on the ionic charge of their surface. LSECs, which are the physical barrier that separate liver tissues from the blood flow,16,17 have significant roles under normal conditions, including providing a selective and permeable barrier, facilitating the transport of metabolites and waste clearance,18–20 regulating hepatic blood flow, maintaining a low portal pressure,21 and keeping hepatic stellate cells in their inactivated state to prevent fibrosis.22 However, the absence of any special characteristics and the phenotype of LSECs, due to capillarization (loss of fenestration and development of basement membrane),23 angiogenesis,24 or altered gene expression,25–27 results in the initiation and progression of various liver diseases, such as inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and cancer metastasis.24,27–31 Therefore, LSECs are possible drug targets for preventing or treating related liver disorders, especially those associated with genetic disturbances. Based on our previous observations, LSECs take up LNPs with higher pKa values, in the pKa range tested (5.70–7.25).32 However, higher pKa values were not examined and the optimum pKa value for targeting LSECs is not currently known.

We previously developed an LNP composed of different types of pH-sensitive cationic lipids, namely YSK lipids (referred to as YSK-LNP), to deliver siRNA in vitro and in vivo, particularly in hepatocytes.33,34 In our previous study, slightly cationic LNP formulations that were composed of lipids with high pKa values, such as YSK13-C4 (pKa 6.80) and YSK15-C4 (pKa 7.10), were found to be highly local-ized in LSECs as opposed to hepatocytes.32 Nevertheless, they showed a weak gene silencing activity in LSECs, possibly due to their inactivation by endothelial lipase (EL).32 This prompted us to investigate the feasibility of targeting LSECs using lipase-resistant LNPs in which the membrane had optimized pKa values.

As mentioned above, instead of synthesizing new lipids with new chemical structures and pKa values, we prepared mixtures of lipids with different pKa values in one LNP formulation at various molar ratios to manipulate the final pKa of the membrane for LSECs targeting. The lipids used were YSK05 and YSK12-C4 (pKa 6.50 and 8.00, respectively). Both lipids are lipase-resistant and have a strong endosomal escape and gene silencing activity.33,35,36 Mixing these lipids into one LNP formulation (referred to as a YSK05/12-LNP) enabled us to prepare a wide variety of formulations in which the membranes had different final pKa values that were not merely dependent on the quantity of each lipid in the mixture, but also on the individual contribution of each lipid to the final pKa value (35% vs 65% by YSK05 and YSK12-C4, respectively). As proof of our concept, we successfully targeted and delivered siRNA to LSECs using one of the YSK05/12-LNP formulations which had an optimum pKa value (7.15) and ionization property (~36% cationic charge) for use in uptake by LSECs.

Material and methods

Materials and reagents

YSK05 (1-methyl-4,4-bis(((9Z,12Z)-octadeca-9,12-dien- 1-yl)oxy)piperidine) and YSK12-C4 (6Z,9Z,28Z,31Z)–19-(4-(dimethyl-amino)butyl)heptatriaconta-6,9,28,31 tetraen-19-ol) lipids were synthesized in our laboratory as described previously.33,36 Cholesterol (Chol) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). 1,2-Dimirystoyl-sn-3-glycero methoxypolyethyleneglycol 2000 ether (mPEG2k-DMG) was purchased from the NOF Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). RiboGreen, DiI, and DiD were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). The TRIzol reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The 6-(p-Toluidino)-2-naphthalenesulfonic acid (TNS) was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd (Osaka, Japan). The sequences for the sense and antisense strands of siRNAs used in this study are listed in Table S1. All the siRNAs used in this study were obtained from Hokkaido System Science (Sapporo, Japan). The sequences for the forward and reverse primers used in this study are listed in Table S2. All primers were obtained from SIGMA Genosys Japan (Ishikari, Japan).

Animals

ICR (♀, 4 weeks, 16–22 g) mice were obtained from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). All animal experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Hokkaido University Animal Care Committee in accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Preparation of LNPs

The LNPs were prepared by a tertiary butanol (t-BuOH) dilution procedure, as previously reported.33,37,38 The lipids, which include 1050 nmol of YSK lipids (YSK05 or YSK12-C4 or a mixture of both), 450 nmol of cholesterol, and 30 nmol of mPEG2k-DMG – which represent a molar ratio of 70:30:2, respectively – were first dissolved in 400 µL of 90% (v/v) t-BuOH. When a fluorescent material (DiI or DiD) was incorporated into the LNPs, it was added at a concentration of 0.5–1 mol% or 0.15 mol% (of the total lipid) to the lipid solution. A 200 µL portion of an aqueous solution containing 40 µg siRNA was then added gradually to the lipid solution under vigorous mixing, producing an siRNA/lipid ratio of 0.042 (wt/wt). The siRNA–lipid solution was then gradually added to 2 mL of 20 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.0) under vigorous mixing to facilitate the precipitation and formation of the LNPs. This yields a final t-BuOH concentration of 60% (v/v). Finally, ultrafiltration using Amicon ultracentrifugal tubes (Merck Millipore Ltd, Darmstadt, Germany) was performed to remove the t-BuOH, replace the external buffer with PBS (−) (pH 7.40), and concentrate the LNPs. Centrifugation was performed at 1,000×g for 11–18 minutes at RT.

Characterization of LNPs

The average diameter and ζ-potential of LNPs were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using Zetasizer Nano ZS ZEN3600 instrument (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK). The siRNA encapsulation efficiency, concentration, and recovery ratio were measured using the RiboGreen assay as previously described;33 by which LNPs were diluted in 10 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.40 containing 20 µg/mL dextran sulfate and RiboGreen in the presence or absence of 0.1 w/v% Triton X-100. Fluorescence was measured using an Enspire 2300 multilabel reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) setup with λex=500 nm, λem=525 nm. The siRNA concentration was calculated from the siRNA standard curve. The siRNA encapsulation effi-ciency was calculated by comparing siRNA concentration in the presence and absence of Triton X-100. The morphology of the LNPs was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), in which a drop of an aqueous solution containing LNPs was adsorbed to carbon-coated copper grids (400 mesh) and the samples were stained with a 2% phosphotungstic acid solution (pH 7.0) for 20 seconds. The sample was observed by TEM (JEM-1400Plus, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 100 kV. Digital images (3,296×2,472 pixels) were taken with a CCD camera (EM-14830RUBY2, JEOL Ltd.).

Measurement of the pKa value of the LNP membrane

The pKa value of the LNP membrane was measured by a TNS assay, as described previously.32,33 First, 0.5 mM of LNP’s lipid and 0.6 mM of TNS (a negatively charged fluorescent dye) were mixed in 200 µL of the following buffers (each buffer contained 150 mM NaCl) 20 mM citrate buffer (pH 3.50–5.50), 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.00–8.00), or 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.00–9.00) in a 96-well plate, to yield a final concentration of 30 and 6 µM of LNP’s lipid and TNS in each well, respectively. Fluorescence was then measured using an Enspire 2300 multilabel reader (Perkin Elmer) setup with λex=321 nm, λem=447 nm at 37°C. The pKa was determined to be the pH value with 50% of maximal fluorescent intensity.

Observation and quantification of biodistribution

Mice, regardless of their body weight to minimize variation, were injected with 200 µL of LNPs encapsulating 10 µg siRNA (assuming a mouse body weight of 20 g, the injected dose would be 0.5 mg of siRNA/kg). In the LNPs, either the lipid was labeled with DiD or the siRNA was labeled with AF647. At 30 minutes after the injection, the mice were sacrificed and their body organs (liver, lung, kidneys, and spleen) were collected and the fluorescence of either the lipids or siRNA was observed using FluorVivo 300 small animal fluorescence imaging (INDEC BioSystems, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For quantifying the fluorescence intensity in each organ, the ImageJ software was used as follows: after selecting the region of interest (ROI) in each image, its corrected fluorescence was measured using the following formula:

The corrected fluorescence of the treated samples was then normalized to the corrected fluorescence of PBS (-)-treated samples and then divided by the area of the ROI.

Observation of intrahepatic distribution

Mice were intravenously injected with DiI-labeled LNP encapsulating a mixture of siRNA (siGL4:siCy5-green fluorescent protein [GFP] 1:1 ratio) at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg of both siRNAs. After 1 hour, the mice were sacrificed, and their liver tissues (0.5–1 cm2) were collected and immersed in staining solution (Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline [D-PBS (-)]) containing 20 µg/mL FITC-labeled Isolectin B4 (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for staining blood vessels and 1 µg/mL Hoechst33342 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) for staining nuclei. Intrahepatic distribution of the LNPs was observed using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM; Nikon A1, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Evaluation of gene silencing

Mice were intravenously injected with the LNPs with a mixture of siRNA (siCD31:siFVII 1:1 ratio) encapsulated at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg of each type of siRNA. After 24 hours, the mice were sacrificed, and their body tissues were collected to evaluate the silencing of CD31 in the endothelium of various organs at the mRNA level as described in this section, and blood was collected to evaluate the silencing of plasma coagulation factor VII (FVII) at the protein level, as described below. To evaluate the silencing of CD31, ~30 mg samples of liver, lung, and spleen tissues were each homogenized using a Precellys 24 (Bertin technologies, Aix-en-Provence, France) in 500 µL of TRIzol reagent, and the RNA was then extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA was then converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using a high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Finally, a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed on cDNA to evaluate gene expression using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and Lightcycler 480 system II (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Measurement of plasma coagulation factor VII activity

At 24 hours after the mice had been injected with the LNPs encapsulating a mixture of siRNA (siCD31:siFVII 1:1 ratio) at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg of each type of siRNA as described in the previous section, blood was collected from their veins in the presence of heparin. The blood was then centrifuged at these conditions: 800×g, 5 minutes, 4°C. Plasma, the clear supernatant of the centrifuged blood, was removed and FVII protein expression was evaluated using a Biophen FVII kit (Hyphen Biomed, Neuville-Sur-Oise, France) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Evaluation of LNP-associated toxicity

The LNP-associated toxicity was evaluated by measuring liver enzyme levels (aspartate transaminase [AST] and alanine transaminase [ALT]) using a GOT·GPT CII kit (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Furthermore, inflammatory cytokine gene expressions (interleukin-6 [IL-6] and tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-α]) were quantified by performing qRT-PCR analysis on cDNA prepared from liver tissues using the same method described in Evaluation of gene silencing section in this article.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean±SD of independent repeats. Statistical comparisons between groups were evaluated by nonrepeated measures ANOVA followed by SNK test.

Results

Physical characteristics of LNPs

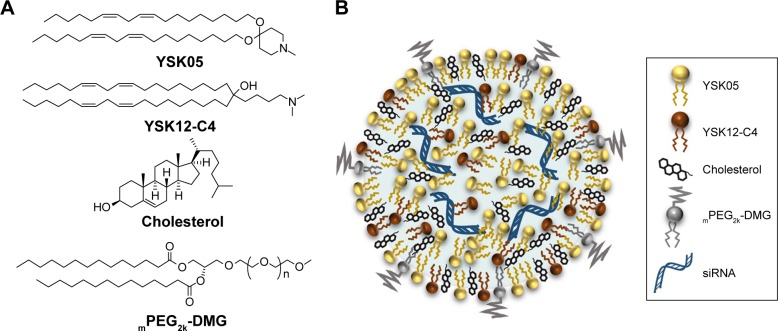

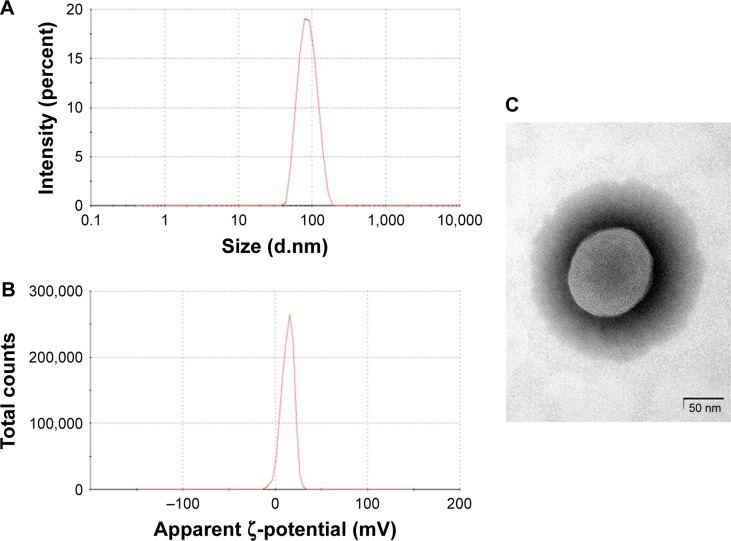

Various LNPs (referred to as YSK05/12-LNPs) were prepared using the t-BuOH dilution procedure by mixing two different lipids YSK05 and YSK12-C4 (pKa 6.50 and 8.00, respectively) as follows: YSK05/YSK12-C4/cholesterol/mPEG2k-DMG=(70–X):X:30:2 mol% of total lipids (X=0–70; Figure 1). Typically, the LNPs have diameters in the range of 70–100 nm with a homogenous size distribution (polydispersity index [PDI] <0.2), and the encapsulation of siRNA exceeds 90%. The ζ-potential at pH 7.40 varied from neutral to cationic, depending on the type of YSK lipid used and the amount in the LNP. An example of measuring the LNP’s particle size and ζ-potential by DLS and observing its morphology by TEM is shown in Figure 2. Further characterization data for the LNPs with various lipid compositions are shown in Table S3.

Figure 1.

Composition and structure of the YSK05/12-LNPs.

Notes: (A) The chemical structure of the lipid components in the LNPs used in this study. (B) A schematic illustration of LNP structure. The YSK05/12-LNP was prepared by means of t-BuOH dilution method by mixing the following different molar ratios of YSK05 and YSK12-C4 lipids: YSK05/YSK12-C4/Cholesterol/mPEG2k-DMG=(70–X):X:30:2 mol% of total lipids (X=0–70).

Abbreviations: LNP, lipid nanoparticle; mPEG2k-DMG, 1,2-Dimirystoyl-sn-3-glycero methoxypolyethyleneglycol 2000 ether; siRNA, short interfering RNA; t-BuOH, tertiary butanol.

Figure 2.

Physical characteristics of the YSK05/12-LNP.

Notes: Particle size (A) and ζ-potential distribution (B), as detected by DLS and the morphology of LNPs, as observed by TEM (C). The YSK05/12-LNP used for these measurements was prepared by means of the t-BuOH dilution method. It has the following composition: YSK05/YSK12-C4/Cholesterol/mPEG2k-DMG=50:20:30:2 mol% of total lipids and the following characteristics: size, 82.75 nm; number mean, 63.24 nm; PDI, 0.079; ζ-potential, 13.5 mV; EE of siRNA, 99.46%. Scale bars: 50 nm (C).

Abbreviations: DLS, dynamic light scattering; EE, encapsulation efficiency; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; mPEG2k-DMG, 1,2-Dimirystoyl-sn-3-glycero methoxypolyethyleneglycol 2000 ether; PDI, polydispersity index; siRNA, short interfering RNA; t-BuOH, tertiary butanol; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

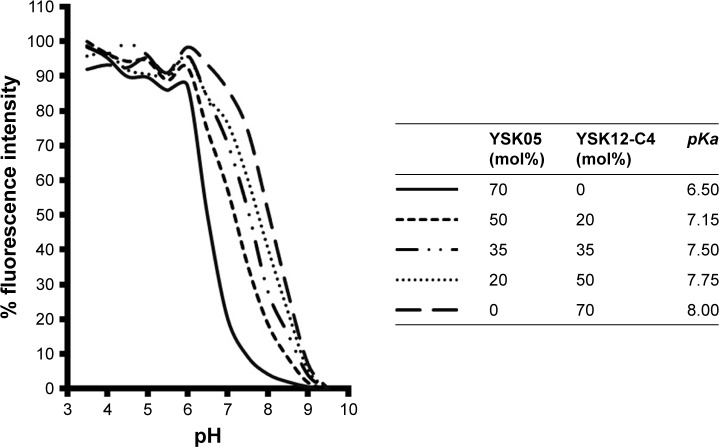

Manipulating the pKa value of the LNP membrane through mixing lipids

The pKa values for the YSK05/12-LNP membranes were determined using a TNS assay. TNS is a compound that electrostatically interacts with the cationic lipid membrane, resulting in fluorescence,39,40 and the pKa of the LNP was determined to be the pH value with 50% maximal fluorescent intensity. This method was found to be a better alternative for ζ-potential measurement to predict the real charge state of the LNP surface in the in vivo environment. As shown in Figure 3, mixing YSK05 and YSK12-C4 (pKa 6.50 and 8.00, respectively) at different molar ratios resulted in LNPs in which the membrane had different final pKa values, ranging between 6.50 and 8.00.

Figure 3.

The YSK05/12-LNP fluorescence intensity under different pH values measured by TNS assay.

Notes: The pKa value of the LNP membranes was determined to be the pH value with 50% of maximal fluorescence intensity. Data represent the mean (n=3).

Abbreviations: LNP, lipid nanoparticle; pKa, acid dissociation constant; TNS, 6-(p-toluidino)-2-naphthalenesulfonic acid.

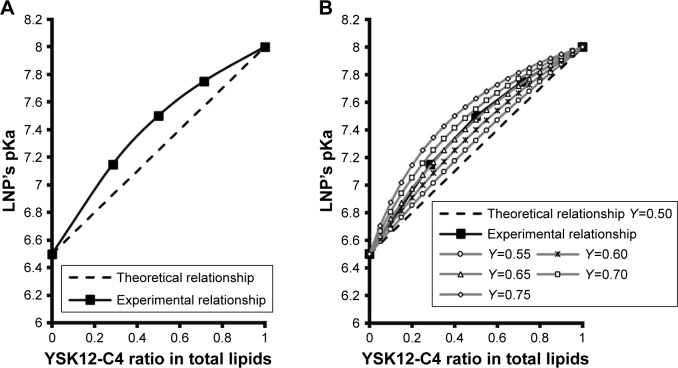

The pKa value of the LNP membrane was not merely dependent on the quantity of lipid used

The relationship between lipid quantity or the molar ratio of each of the lipid components and the final pKa value for the membrane was expected to be linear, as represented in Figure 4A, dotted line. In other words, the pKa value or the LNP membrane was expected to be an average of the pKa values of its lipid components, depending on their quantity, which can be calculated using Equation 1 considering two factors: the pKa value of each lipid and its molar ratio in the LNP.

| (1) |

where pKa1 is the pKa of first lipid (eg, YSK12-C4), pKa2 is the pKa of second lipid (eg, YSK05), pKa1+2 is the pKa of the LNP (eg, YSK05/12-LNP), X is the molar ratio of one lipid (eg, YSK12-C4).

Figure 4.

The relationship between lipid quantity and the pKa value of the LNP membrane.

Notes: (A) The relationship between the YSK12-C4 ratio in total lipids (X/70) and the pKa value for the YSK05/12-LNP membrane, theoretically simulated or experimentally measured using Equation 1 or TNS assay, respectively. (B) Determination of Y value (contribution factor) of YSK12-C4 lipid in the modified Equation 2.

Abbreviations: LNP, lipid nanoparticle; TNS, 6-(p-toluidino)-2-naphthalenesulfonic acid; pKa, acid dissociation constant.

However, the experimental results indicated that this was not the case, in that, the relationship between the molar ratio of each of the LNP’s lipid components and the final pKa value for the membrane exhibited a nonlinear relationship, in which YSK12-C4 (pKa 8.00) had a higher contribution to the final pKa value than YSK05 (pKa 6.50) (Figure 4A, line with squares). Therefore, the equation was modified to Equation 2 by adding a third factor, the Y factor (contribution factor), which represents the contribution of each lipid in the pKa value for the LNP membrane.

| (2) |

where pKa1 is the pKa of first lipid (eg, YSK12-C4), pKa2 is the pKa of second lipid (eg, YSK05), pKa1+2 is the pKa of the LNP (eg, YSK05/12-LNP), X is the molar ratio of one lipid (eg, YSK12-C4), and Y is the contribution of one lipid (eg, YSK12-C4).

If the relationship between the molar ratio of each of the LNP’s lipid components and its final membrane’s pKa value was linear, then the Y value of each lipid should be equal to 0.50, which represents a 50% contribution of each lipid to the final pKa value for the LNP membrane. However, because the experimentally found relationship was nonlinear, the Y value of both lipids is different. To determine the Y value (eg, of the YSK12-C4 lipid) in the experimental nonlinear relationship, various values >0.50 but <1.00 were examined. These values were chosen to be >0.50 because the YSK12-C4 lipid had a higher contribution than YSK05 to the final pKa value for the LNP, as observed in Figure 4A, the line with squares. The chosen Y values were then tested in Equation 2 to produce simulated relationships as shown in Figure 4B.

The Y value that was found to fit completely into the equation to produce a simulated relationship identical to the experimental relationship measured by the TNS assay was 0.65 (Figure 4B, gray line with open triangles). In other words, YSK12-C4 lipid (pKa 8.00) contributes 65% of the pKa value for the YSK05/12-LNP membrane, while the YSK05 lipid (pKa 6.50) contributes the remainder, ie, 35%.

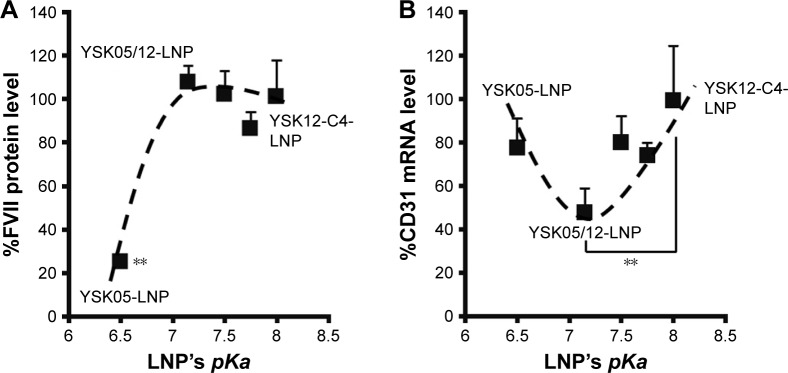

Gene silencing activity in the liver is dependent on the pKa value of its membrane

Mice were intravenously injected with YSK05/12-LNPs in which the membranes had different pKa values, as shown in Figure 3. Gene knockdown activity in hepatocytes was observed for LNPs that contained the YSK05 lipid only, with a pKa value of 6.50. This type of LNP induced approximately an 80% gene silencing of the FVII protein (a hepatocyte marker that has been used by us and other researchers as a reliable indicator of gene silencing activity of LNPs in the liver)34,37,43 with a 0.1 mg/kg dose of siFVII (Figure 5A). On the other hand, in LSECs, although LNPs composed of the YSK05 lipid only or the YSK12-C4 lipid produced only a weak activity, mixing these lipids in one LNP formulation optimized the pKa value for the membrane and improved the LNP silencing activity to an approximately 60% knockdown of CD31 mRNA (an endothelial cell marker) with a 0.1 mg/kg dose of siCD31 (Figure 5B). The YSK05/12-LNP with the composition YSK05/YSK12-C4/cholesterol/mPEG2k-DMG=50:20:30:2 mol% of total lipids resulted in the best mRNA silencing activity in LSECs, and the pKa value for its membrane was 7.15, thus confirming this to be optimal for specific uptake by LSECs. Furthermore, this optimized LNP had a minimal activity in other organ endothelia, such as the lung and spleen (Figure S1).

Figure 5.

In vivo silencing activity of LNPs in hepatocytes and LSECs.

Notes: Mice were intravenously injected with LNPs encapsulating a mixture of siRNA (siCD31:siFVII 1:1 ratio) at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg of each type of siRNA. After 24 hours, levels of the FVII protein in plasma (A) and CD31 mRNA in liver tissues (B) were measured by means of an FVII assay and qRT-PCR, respectively. The reference gene in LSECs was TIE2. **P<0.01, nonrepeated ANOVA followed by an SNK test; data represent the mean±SD (n=3).

Abbreviations: FVII, coagulation factor VII; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; LSECs, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells; mRNA, messenger RNA; pKa, acid dissociation constant; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; siRNA, short interfering RNA; TIE2, angiopoietin receptor.

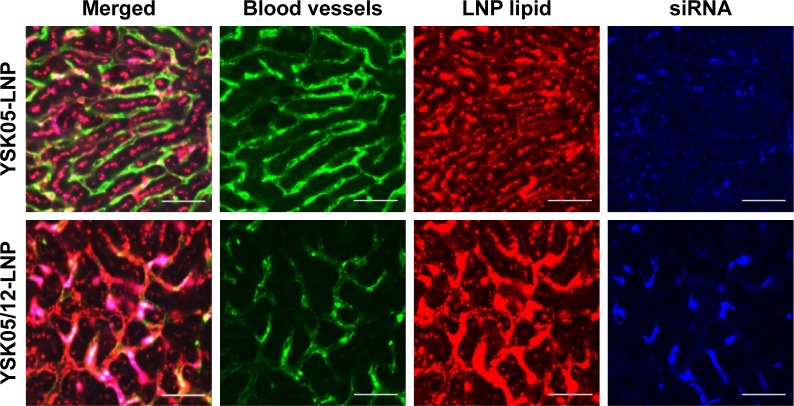

Optimizing the pKa value of the LNP membrane improves its targeting efficiency

The FluorVivo imaging (Figure S2) revealed that the YSK05-LNP (pKa 6.50) and YSK05/12-LNP (pKa 7.15 and composition of YSK05/YSK12-C4/cholesterol/mPEG2k-DMG=50:20:30:2 mol% of total lipids) have a similar biodistribution pattern and they are largely distributed to liver tissues. However, we decided to compare their intrahepatic distribution by observing liver tissues that had been injected with DiI-labeled LNP encapsulating a mixture of siRNA (siGL4:siCy5-GFP 1:1 ratio) at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg of both siRNAs using CLSM. Although the injected siRNA dose was higher than that used for obtaining gene silencing (0.5 vs 0.1 mg/kg, respectively), it was selected to enable us to visualize hepatic distribution with high sensitivity and clarity. We observed the LNP containing the YSK05 lipid only (YSK05-LNP) and a pKa of 6.50 was extensively taken up by hepatocytes (Figure 6, upper). In the image, the YSK05-LNP (represented in red color) is extensively distributed in hepatocytes, which are the most abundant cells in the liver and are defined in the image as the nonfluorescent areas that are infiltrated with LSECs which are shown in green color. On the other hand, the YSK05/12-LNP with a pKa value of 7.15 was highly taken up by LSECs (Figure 6, lower). In the image, YSK05/12-LNP (represented in red) is distributed on LSECs (the green color of LSECs turned into red or orange because of LNP accumulation in this area). These results suggest that, despite the similar hepatic biodistribution of YSK05-LNP and YSK05/12-LNP, as shown in Figure S2, their intrahepatic distribution varied depending on their pKa value.

Figure 6.

Intrahepatic distribution of YSK05-LNP (pKa 6.50) and YSK05/12-LNP (pKa 7.15).

Notes: Mice were intravenously injected with DiI-labeled LNPs encapsulating a mixture of siRNA (siGL4:siCy5-GFP 1:1 ratio) at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg of both siRNAs. After 1 hour, liver tissues were collected and the distribution of LNPs was observed by CLSM. Green color represents blood vessels/LSECs (FITC-Isolectin B4), red color represents LNP (DiI), and blue color represents siRNA (Cy5). Scale bars: 50 µm.

Abbreviations: CLSM, confocal laser scanning microscopy; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; GFP, green fluorescent protein; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; LSECs, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells; siRNA, short interfering RNA.

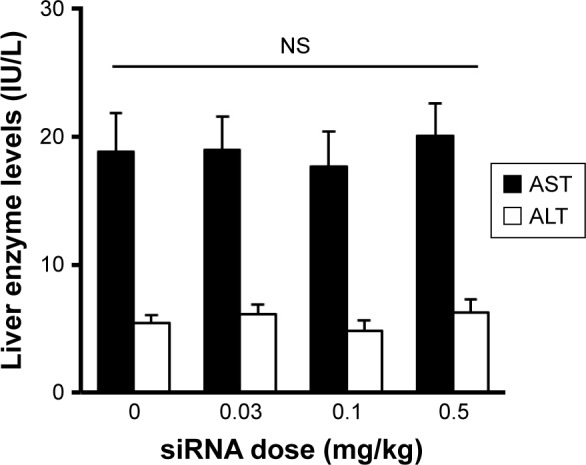

It is noteworthy that no increase in the levels of liver enzymes (AST or ALT) was observed after intravenously injecting the mice with YSK05/12-LNP (Figure 7). Furthermore, inflammatory cytokine gene expression (for IL-6 and TNF-α) was quantified in the liver tissues of the same group of mice by qRT-PCR; no increase in expression was found (data not shown). These data suggest the safety and lack of toxicity of the LNPs.

Figure 7.

Liver enzyme levels after YSK05/12-LNP injection.

Notes: Mice were intravenously injected with YSK05/12-LNP. After 24 hours, plasma was collected, and liver enzymes were evaluated using a GOT·GPT CII kit. Nonrepeated ANOVA followed by an SNK test; data represent mean±SD (n=3).

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase (GPT); AST, aspartate transaminase (GOT); LNP, lipid nanoparticle; NS, not significant; siRNA, short interfering RNA.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to improve the targeting efficiency of an LNP by optimizing the dissociation constant (pKa) value for its membrane, which reflects its ionization property or surface charge. This would permit electrostatic interactions with targeted tissues since both structures would have complementary charges. This could selectively enhance the uptake of LNPs by tissues of interest with minimal distribution to others, in a process that is called ionic-based physical targeting.

We previously reported on the development of our original LNPs, which can be prepared using several types of lipids that were synthesized in our laboratory, and are referred to as YSK lipids, to deliver siRNA to cells, both in vitro and in vivo.32–38 LNPs, especially those containing lipids, namely YSK05 and YSK13-C3, showed a high cellular uptake, strong endosomal escape, and efficient siRNA delivery and silencing activity, especially in hepatocytes.33,34 We also found that the pKa value of the LNP membrane influences its intrahepatic distribution. For example, LNPs that contain lipids with low pKa values (eg, YSK05 and YSK13-C3 with pKa values of 6.50 and 6.45 pKa, respectively) are distributed in hepatocytes. Whereas, those containing lipids with higher pKa values (eg, YSK13-C4 and YSK15-C4 with pKa values of 6.80 and 7.10, respectively) are distributed in LSECs,32 which are border cells that are located between hepatocytes and the blood stream.16,17 However, due to the limited range of pKa values (5.70–7.25) that were tested in that previous study,32 higher pKa values were not evaluated and the optimal pKa value for an LNP for uptake by LSECs was not confirmed. Furthermore, despite the enhanced pKa-dependent distribution of YSK13-C4- and YSK15-C4-LNPs in LSECs, the silencing activity in those cells was relatively weak, probably due to their inactivation by EL which are distributed in LSECs and have phospholipase activity that cleaves the ester linkage present in those lipids.32,41 Inactivation by other lipases such as lipoprotein lipase or hepatic lipase can be excluded because they have triglyceride lipase activity.

We selected LSECs as a target tissue in this study for two reasons: first, the potential for LSEC targeting using LNPs containing a membrane with an optimized pKa value32 would confirm the feasibility of our concept regarding ionic-based physical targeting. Second, the significance of LSECs in liver pathophysiology qualifies them as a potential drug target candidate for treating various liver disorders,18–31 especially those related to genetic disturbances that could be corrected by siRNA-based therapeutics and gene silencing. To improve the activity of YSK13-C4- and YSK15-C4-LNPs in LSECs, it was necessary to change the ester linker in those lipids to prevent their inactivation by EL. However, changing the linker type might hinder the ability of those lipids to induce efficient endosomal escape. It was reported elsewhere that the presence of an ester linker facilitates the lipid mixing mechanism with endosomal membranes, thus leading to an efficient endosomal escape of cargos even without the need to add helper fusogenic lipids.42,43 Another solution would be to preserve the ester linkages but inhibit EL activity. However, EL inhibitors such as GSK264220A might induce systemic side effects due to their interference with the physiological roles of EL in lipid metabolism.44 Therefore, it would be more efficient to develop an LNP formulation for which the pKa value of the membrane would be optimal for targeting LSECs using lipase-resistant lipids.

There are two possible strategies for optimizing the pKa of an LNP membrane for LSECs targeting. The first strategy is the synthesis of various lipids with different chemical structures and pKa values for use in preparing LNPs with a wide range of membrane pKa values and screen the uptake and activity of each in LSECs. However, this method is time- and effort-consuming, not cost-effective, and results in limited pKa adjustments. Therefore, we adopted a more effective strategy, which involved mixing two lipids at different molar ratios with low and high pKa values in several LNP formulations to permit the pKa value of the final LNP membrane. These lipids are YSK05 (a pH-sensitive cationic lipid with a pKa value of 6.50), and YSK12-C4 (a highly cationic lipid with a pKa value of 8.00). Their chemical structures are shown in Figure 1. These lipids were chosen because they have a strong endosomal escape, strong activity (YSK05 in hepatocytes, in vivo,33 and YSK12-C4 in dendritic cells, in vitro36), and are resistant to the action of lipases. Several formulations (referred to as YSK05/12-LNPs) were prepared with the following composition: YSK05/YSK12-C4/cholesterol/mPEG2k-DMG=(70–X):X:30:2 mol% of total lipids (X=0–70; Figure 1). As shown in Figure 2 and Table S3, the YSK05/12-LNPs, which were prepared using the t-BuOH procedure, typically have a diameter in the range of 70–100 nm with a homogenous size distribution (PDI,0.2), and the encapsulation of siRNA exceeds 90%. The ζ-potential distribution of the LNPs at pH 7.40 was varied depending on the type of YSK lipid used and the amount in the LNP. Generally, the ζ-potential value of the LNP shifts from neutral (when only the YSK05 lipid was used) to cationic (when only the YSK12-C4 lipid was used or mixed with YSK05 lipid). The pKa values of the YSK05/12-LNP membrane were measured by the fluorescent intensity of TNS, a compound that fluoresces only when it interacts with cationic lipid membranes.39,40 As we reported in a previous study,32 the apparent pKa value of the LNP, which was determined to be the pH with 50% of the maximal fluorescence intensity of TNS, reflects the real charge state or ionization property of the LNP membrane in an in vivo environment, and is a better alternative to the ζ-potential value which could be influenced by nonencapsulated negatively charged siRNA and/or PEG-DMG molecules that are attached to the LNP surface in the buffer while the ζ-potential is being measured but are subsequently detached in the blood circulation.

It was previously reported that the pH-sensitivity of the delivery system is a key parameter for its efficiency in delivering siRNA.33,45 An efficient delivery system should be able to sense small pH changes in the environment, such as the neutral pH in the blood and the acidic pH in cellular endosomes, and to switch its charge to a cationic charge in the endosome for efficient endosomal escape. As shown in Figure 3, mixing the lipids in the LNP formulation had no effect on its pH-sensitivity, but rather it influenced the pKa of the membrane and permitted the preparation of LNP formulations with pKa values between 6.50 and 8.00 at various lipid molar ratios. As a result, lipid mixing was found to be an effective strategy for manipulating the final pKa value of the LNP.

Before mixing the lipids, we expected to see a linear relationship between each lipid molar ratio and the final LNP’s pKa value (Figure 4A, dotted line), in which both lipids would contribute equally to the final pKa, and the final pKa can be calculated using a simple mathematical equation that considers two factors: the pKa value of each lipid and its molar ratio in the formulation (Equation 1). However, the experimental relationship, as measured by a TNS assay was unexpectedly nonlinear (Figure 4B, line with squares), in which YSK12-C4 lipid (pKa 8.00) had a higher impact and contribution to the final pKa for the LNP than YSK05 (pKa 6.50). Therefore, the equation was modified by adding a third factor called the Y factor or contribution factor (Equation 2). In the linear simulated relationship, the Y factor equals 0.50, meaning that each lipid contributes equally or by 50% to the final pKa value for the LNP. To determine the Y value in the experimental relationship and specifically for the YSK12-C4 lipid which had a higher contribution in the final pKa, we investigated a series of values >0.50 and <1.00 (0.50<Y<1.00), which represents the percentage of the lipid contribution (50%–100%) in the final pKa value. The Y value that was found to fit completely into the equation to produce a relationship identical to the experimental relationship was 0.65 (Figure 4B, gray line with open triangles). This indicates that YSK12-C4 contributes to the final pKa by 65%, while the contribution by YSK05 is 35%. The reasons for this difference remain to be investigated in a future study. It is noteworthy that we previously encountered this nonlinear relationship when we used two different lipids, namely, YSK13-C2 and YSK13-C4 (pKa 5.70 and 6.80, respectively) in one LNP formulation. The YSK13-C4 lipid contributed to a higher extent, by 73%, to the final pKa value of the LNP (the Y value measured using Equation 2 was 0.73), while the YSK13-C2 lipid contributed the rest, ie, 27%, to the final LNP’s pKa ([n=2], data not shown). We cannot, however, conclude that Equation 1 or 2 can be applied universally. More studies will need to be carried out using different kinds of lipids with different pKa values to confirm that this is a universal equation that predicts the final pKa value of the LNP resulting from lipid mixing.

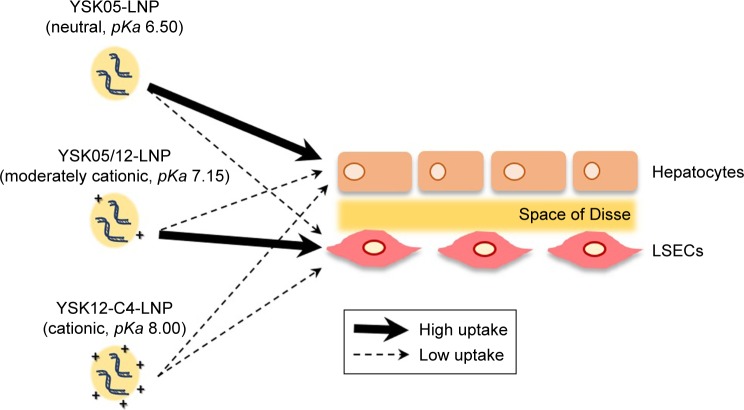

After preparing YSK05/12-LNPs in which the membranes have different pKa values, the in vivo knockdown activity of these LNPs was evaluated. Basically, the intrahepatic activity of YSK05/12-LNPs was compared with that of the original YSK05- or YSK12-C4-LNPs (the pKa values for all these preparations are shown in Figure 3). The formulation that induced the strongest knockdown activity in hepatocytes was YSK05-LNP (pKa 6.50), while the activities for the YSK05/12-LNPs and YSK12-C4-LNP, which have higher pKa values, were considerably lower (Figure 5A). A possible reason behind the hepatocyte uptake of YSK05-LNP might be related to the fact that hepatocytes preferentially take up neutral particles with lower pKa values through the apolipoprotein E-low density lipoprotein receptor pathway, and this coincides with previous reports.32,43 On the other hand, in LSECs, despite the weak activity of both YSK05-and YSK12-C4-LNPs, using mixtures in YSK05/12-LNP dramatically improved their activity in LSECs as the result of optimizing the pKa value for the LNP membrane to 7.15 (Figure 5B). A possible reason behind this is the preference of endothelial cells to take up slightly cationic particles which electrostatically interact with the slightly anionic charge of the endothelial membrane.

The YSK05/12-LNP formulation which is composed of YSK05/YSK12-C4/cholesterol/mPEG2k-DMG (50:20:30:2 mol%) and a pKa value of 7.15 was chosen for use in experiments to target LSECs and compared with YSK05-LNP. Although YSK05-LNP and YSK05/12-LNP have a similar biodistribution, as shown in Figure S2, in which the lipids and siRNA of both types of LNPs were visualized by Fluo-rVivo imaging and were found to be largely distributed to liver tissues, the intrahepatic distribution of those LNPs varied and was determined by their pKa value. The intrahepatic distribution was shifted substantially from hepatocytes (with YSK05-LNP [pKa 6.50; Figure 6, upper]) into LSECs (with YSK05/12-LNP [pKa 7.15; Figure 6, lower]). However, we observed that traces of the YSK05/12-LNP were distributed into hepatocytes and liver resident macrophages (Kupffer cells). Furthermore, the biodistribution of YSK05/12-LNP to the lung and spleen was minimal (only a weak siRNA fluorescent intensity was detected in lungs [Figure S2]) and its silencing activity in lung and spleen endothelia was weak (Figure S1). The selectivity of the YSK05/12-LNP for the liver endothelium over the lung or spleen endothelium can be attributed to the special scavenging character of LSECs, which have a very high endocytic capacity and are responsible for the uptake of soluble or colloidal materials and nanoparticles that are not large enough to be phagocytosed by Kupffer cells.16,17,20,46,47 It is noteworthy that, despite the improved activity in LSECs, the YSK05-LNP was still stronger in hepatocytes than the YSK05/12-LNP in LSECs. This can be attributed to the difference in the type of siRNA used to target hepatocytes or LSECs (siFVII vs siCD31, respectively), which might have different gene silencing strengths. Furthermore, differences in cellular properties between hepatocytes and LSECs should also be considered. Another possible explanation is related to the low uptake of YSK05/12-LNP by Kupffer cells due to its cationic charge. However, this uptake is small compared with that of YSK12-C4-LNP (pKa 8.00), which could be taken up by Kupffer cells due to its highly cationic charge, and despite its strong activity in vitro,36 it lost its activity completely in vivo. Moreover, the weak activity of the YSK12-C4-LNP could be attributed to its rapid disintegration in the blood stream and the leakage of siRNA. As shown in Figure S2, the siRNA was rapidly eliminated and detected in the kidney at 30 minutes after intravenous administration, possibly due to the high cationic charge of the LNP and its recognition by the reticuloendothelial system, while the lipids derived from LNPs were mostly distributed to lungs and, to a lower extent, the liver. This suggests that the pKa value of the LNP is critical in terms of its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and should be used in conjunction with a cation to maintain the LNP’s integrity, stability in the blood, and distribution and uptake by targeted tissues.

The optimized YSK05/12-LNP (pKa 7.15) induced an mRNA knockdown of approximately 60% in the case of a 0.1 mg/kg dose of siRNA targeting the CD31 gene in LSECs. This is a remarkable improvement compared with YSK05-LNP, which induced only around 20% knockdown in LSECs with the same dose, and to the YSK12-C4-LNP which induced no activity at all with the same dose. In addition, this LNP had a stronger activity than a previously optimized LNP in our laboratory to target LSECs, in which the YSK05-LNP was modified by attaching a ligand specific for LSECs to its surface (the KLGR peptide ligand was used which was designed from the ApoB-100 sequence of an LDL molecule), and which needed a higher dose of 1 mg siRNA/kg to induce effective gene silencing.48,49

The pKa value of the LNP 7.15 was determined to be a balanced value, not low or neutral in order to be taken up by hepatocytes, and not very cationic in order to be taken up by Kupffer cells. In contrast, a pKa value of 7.15 represents a ~36% cationic charge, which was found to be optimum for LSECs uptake (Figure 8). The YSK05/12-LNP is free of toxicity and side effects (Figure 7), which makes it a better substitute for viral vectors.50 In addition, it has potential applications for producing in vivo pharmacological effects by silencing any gene of interest in LSECs, thus permitting a variety of diseases associated with such cells to be treated. Unlike ligand-based,51–54 or size-based LSECs targeting,55 the YSK05/12-LNP provided, for the first time, a new strategy for targeting LSECs through optimizing the pKa value of the carrier membrane or ionization property, which was confirmed to be an important physiochemical property that could have great applications in targeting more challenging tissues other than the liver. Further studies are needed to investigate the physiochemical properties of the pKa-modified LNPs in the physiological environment and their biophysical interactions with protein corona which could alter their fate and interaction with targeted cellular membranes, as discussed previously elsewhere.56

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of the current strategy and findings.

Note: Manipulating the pKa value of the LNP’s membrane for optimizing the targeting of LSECs.

Abbreviations: LNP, lipid nanoparticle; LSECs, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells; pKa, acid dissociation constant.

Conclusion

In the present study, specific tissue targeting was successfully achieved by optimizing the pKa value of the membrane of an LNP by mixing different lipids with different pKa values into one formulation. The lipids used in this study did not contribute equally to the process, in that a nonlinear pattern of pKa modification was found, in which the final pKa of the LNP membrane was dependent not only on the quantity of each lipid but also on the individual contribution of each lipid in the final pKa value. This strategy has the potential for preparing custom LNPs with endless varieties of structures and final pKa values, and would have potential applications in drug delivery and ionic-based tissue targeting.

Supplementary materials

In vivo silencing activity of YSK05-LNP (pKa 6.50) and YSK05/12-LNP (pKa 7.15) in the lung and spleen.

Notes: Mice were intravenously injected with the LNPs encapsulating a mixture of siRNA (siCD31:siFVII 1:1 ratio) at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg of each type of siRNA. After 24 hours, the level of CD31 mRNA in the lung (A) and spleen (B) was measured by means of qRT-PCR. The reference genes were TIE2 in the lung and GAPDH in the spleen. *P<0.05, nonrepeated ANOVA followed by an SNK test; data represent mean±SD (n=4).

Abbreviations: FVII, coagulation factor VII; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; mRNA, messenger RNA; NS, not significant; NT, non-treated; pKa, acid dissociation constant; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; TIE2, angiopoietin receptor.

Biodistribution of LNPs.

Notes: Mice were intravenously injected, regardless of their body weight, with 200 µL of LNPs encapsulating 10 µg siRNA (assuming a mouse body weight of 20 g, the injected dose will be 0.5 mg siRNA/kg). In the LNPs, either the lipids were labeled with DiD or the siRNA was labeled with AF647. At 30 minutes after injection, the mice were sacrificed and body organs (liver, lung, kidneys, and spleen) were collected and fluorescence of either the lipids or the siRNA was observed using FluorVivo 300 small animal fluorescence imaging (A). The biodistribution of lipids (B) and siRNA (C), respectively, was further quantified using ImageJ software. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, nonrepeated ANOVA followed by an SNK test; data represent the mean±SD (n=3).

Abbreviations: AF647, alexafluor 647; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; siRNA, short interfering RNA.

Table S1.

List of siRNA sequences used in this study

| siRNA | Sense strand (5′–3′) | Antisense strand (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| siFVII | GGAucAucucAAGucuuACT*T | GuAAGAcuuGAGAuGAuccT*T |

| siCD31-1 | GCACAGUGAUGCUGAACAATT | UUGUUCAGCAUCACUGUGCTT |

| siCD31-2 | GUGCAUAGUUCAAGUGACATT | UGUCACUUGAACUAUGCACTT |

| siCD31-3 | GCAAGAAGCAGGAAGGACATT | UGUCCUUCCUGCUUCUUGCTT |

| Cy5-siGFP | AcAuGAAGcAGcACGACuUT*T | AAGUCGUGCUGCUUCAUGUT*T-Cy5 |

| AF647-siGL4 | AF647-CCGUCGUCUUCGUGAACAATT | UUGCUCACGAAUACGACGGTT |

| siGL4 | CCGUCGUCUUCGUGAACAATT | UUGCUCACGAAUACGACGGTT |

Notes: 2′-OMe-modified nucleotides are depicted in lowercase letters, 2′-fluoro-modified nucleotides are shown in bold lowercase letters, and phosphorothioate linkages are denoted by asterisks. The siCD31-1, -2, and -3 were mixed together in advance.

Abbreviations: AF647, alexafluor 647; FVII, coagulation factor VII; GFP, green fluorescent protein; siRNA, short interfering RNA.

Table S2.

List of PCR primers used in this study

| Gene | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| GAPDH | AGCAAGGACACTGAGCAAG | TAGGCCCCTCCTGTTATTATG |

| ACTB | AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC | CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT |

| CD31 | TACAGTGGACACTACACCTG | GACTGGAGGAGAACTCTAAC |

| TIE2 | GACCAGACTGTAAGCTCAG | AATCCTCTATCTGTGGAGTC |

Abbreviations: ACTB, beta-actin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TIE2, angiopoietin receptor.

Table S3.

Physical characteristics of the LNPs

| Lipid composition

|

pKa | Size (nm) | Number mean (nm) | PDI | ζ-potential (mV) | EE of siRNA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YSK05 (mol%) | YSK12-C4 (mol%) | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| 70 | 0 | 6.50 | 84.02 ± 6.82 | 58.52 ± 3.49 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 1.70 ± 4.59 | 94.82 ± 0.64 |

| 50 | 20 | 7.15 | 85.59 ± 8.22 | 55.71 ± 2.91 | 0.17 ± 0.08 | 6.12 ± 1.46 | 95.32 ± 1.12 |

| 35 | 35 | 7.50 | 84.89 ± 11.79 | 56.31 ± 7.80 | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 7.75 ± 2.83 | 96.18 ± 1.73 |

| 20 | 50 | 7.75 | 92.86 ± 10.27 | 56.55 ± 8.01 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 8.97 ± 1.74 | 97.58 ± 0.96 |

| 0 | 70 | 8.00 | 92.61 ± 11.47 | 51.72 ± 0.99 | 0.22 ± 0.10 | 11.63 ± 1.56 | 97.41 ± 0.67 |

Notes: After preparing LNPs that have the composition YSK05/YSK12 C4/Cholesterol/mPEG2k-DMG=(70-X):X:30:2 mol% of total lipids (X=0~70) by t-BuOH dilution method, the pKa was measured using a TNS assay; size, number mean, PDI, and ζ-potential were measured using DLS; EE of siRNA was measured using RiboGreen assay. Data represent mean±SD (n=3).

Abbreviations: DLS, dynamic light scattering; EE, encapsulation efficiency; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; PDI, polydispersity index; mPEG2k-DMG, 1,2-Dimirystoyl-sn-3-glycero methoxypolyethyleneglycol 2000 ether; pKa, acid dissociation constant; siRNA, short interfering RNA; t-BuOH, tertiary butanol; TNS, 6-(p-toluidino)-2-naphthalenesulfonic acid.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant numbers 15K20831 and 17H05052). The authors also wish to thank doctor Milton S Feather for his helpful advice in writing the English manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986;46(12 Pt 1):6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maeda H, Matsumura Y. Tumoritropic and lymphotropic principles of macromolecular drugs. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 1989;6(3):193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitetta ES, Krolick KA, Miyama-Inaba M, Cushley W, Uhr JW. Immunotoxins: a new approach to cancer therapy. Science. 1983;219(4585):644–650. doi: 10.1126/science.6218613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrne JD, Betancourt T, Brannon-Peppas L. Active targeting schemes for nanoparticle systems in cancer therapeutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60(15):1615–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torchilin VP, Zhou F, Huang L. pH-sensitive liposomes. J Liposome Res. 1993;3(2):201–255. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein JN, Magin RL, Yatvin MB, Zaharko DS. Liposomes and local hyperthermia: selective delivery of methotrexate to heated tumors. Science. 1979;204(4389):188–191. doi: 10.1126/science.432641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexis F, Pridgen E, Molnar LK, Farokhzad OC. Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008;5(4):505–515. doi: 10.1021/mp800051m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nigavekar SS, Sung LY, Llanes M, et al. 3H dendrimer nanoparticle organ/tumor distribution. Pharm Res. 2004;21(3):476–483. doi: 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000019302.26097.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar P, Ban HS, Kim SS, et al. T cell-specific siRNA delivery suppresses HIV-1 infection in humanized mice. Cell. 2008;134(4):577–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eguchi A, Meade BR, Chang YC, et al. Efficient siRNA delivery into primary cells by a peptide transduction domain-dsRNA binding domain fusion protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(6):567–571. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh Y, Tomar S, Khan S, et al. Bridging small interfering RNA with giant therapeutic outcomes using nanometric liposomes. J Control Release. 2015;220(Pt A):368–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leung AK, Tam YY, Cullis PR. Lipid nanoparticles for short interfering RNA delivery. Adv Genet. 2014;88:71–110. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800148-6.00004-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hope MJ. Enhancing siRNA delivery by employing lipid nanoparticles. Ther Deliv. 2014;5(6):663–673. doi: 10.4155/tde.14.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan C, Allen TM, Cullis PR. Lipid nanoparticle delivery systems for siRNA-based therapeutics. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2014;4(1):74–83. doi: 10.1007/s13346-013-0161-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maier MA, Jayaraman M, Matsuda S, et al. Biodegradable lipids enabling rapidly eliminated lipid nanoparticles for systemic delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Mol Ther. 2013;21(8):1570–1578. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wisse E. An electron microscopic study of the fenestrated endothelial lining of rat liver sinusoids. J Ultrastruct Res. 1970;31(1):125–150. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(70)90150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisse E. An ultrastructural characterization of the endothelial cell in the rat liver sinusoid under normal and various experimental conditions, as a contribution to the distinction between endothelial and Kupffer cells. J Ultrastruct Res. 1972;38(5):528–562. doi: 10.1016/0022-5320(72)90089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser R, Bosanquet AG, Day WA. Filtration of chylomicrons by the liver may influence cholesterol metabolism and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1978;29(2):113–123. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(78)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redgrave TG. Formation of cholesteryl ester-rich particulate lipid during metabolism of chylomicrons. J Clin Invest. 1970;49(3):465–471. doi: 10.1172/JCI106255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smedsrød B, Pertoft H, Gustafson S, Laurent TC. Scavenger functions of the liver endothelial cell. Biochem J. 1990;266(2):313–327. doi: 10.1042/bj2660313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah V, Haddad FG, Garcia-Cardena G, et al. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are responsible for nitric oxide modulation of resistance in the hepatic sinusoids. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(11):2923–2930. doi: 10.1172/JCI119842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deleve LD, Wang X, Guo Y. Sinusoidal endothelial cells prevent rat stellate cell activation and promote reversion to quiescence. Hepatology. 2008;48(3):920–930. doi: 10.1002/hep.22351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaffner F, Poper H. Capillarization of hepatic sinusoids in man. Gastroenterology. 1963;44:239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thabut D, Shah V. Intrahepatic angiogenesis and sinusoidal remodeling in chronic liver disease: new targets for the treatment of portal hypertension? J Hepatol. 2010;53(5):976–980. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramadori G, Moriconi F, Malik I, Dudas J. Physiology and pathophysiology of liver inflammation, damage and repair. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59:107–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neubauer K, Wilfling T, Ritzel A, Ramadori G. Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 gene expression in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells during liver injury and repair. J Hepatol. 2000;32(6):921–932. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Márquez J, Kohli M, Arteta B, et al. Identification of hepatic microvascular adhesion-related genes of human colon cancer cells using random homozygous gene perturbation. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(9):2113–2122. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasarín M, La Mura V, Gracia-Sancho J, et al. Sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction precedes inflammation and fibrosis in a model of NAFLD. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e32785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Z, Han M, Chen T, Yan W, Ning Q. Acute liver failure: mechanisms of immune-mediated liver injury. Liver Int. 2010;30(6):782–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mori T, Okanoue T, Sawa Y, Hori N, Ohta M, Kagawa K. Defenestration of the sinusoidal endothelial cell in a rat model of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1993;17(5):891–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arteta B, Lasuen N, Lopategi A, Sveinbjörnsson B, Smedsrød B, Vidal-Vanaclocha F. Colon carcinoma cell interaction with liver sinusoidal endothelium inhibits organ-specific antitumor immunity through interleukin-1-induced mannose receptor in mice. Hepatology. 2010;51(6):2172–2182. doi: 10.1002/hep.23590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato Y, Hatakeyama H, Hyodo M, Harashima H. Relationship between the physicochemical properties of lipid nanoparticles and the quality of siRNA delivery to liver cells. Mol Ther. 2016;24(4):788–795. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato Y, Hatakeyama H, Sakurai Y, Hyodo M, Akita H, Harashima H. A pH-sensitive cationic lipid facilitates the delivery of liposomal siRNA and gene silencing activity in vitro and in vivo. J Control Release. 2012;163(3):267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto N, Sato Y, Munakata T, et al. Novel pH-sensitive multifunctional envelope-type nanodevice for siRNA-based treatments for chronic HBV infection. J Hepatol. 2016;64(3):547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato Y, Hatakeyama H, Hyodo M, Akita H, Harashima H. Development of an efficient short interference RNA (siRNA) delivery system with a new pH-sensitive cationic lipid. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2012;132(12):1355–1363. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.12-00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warashina S, Nakamura T, Sato Y, et al. A lipid nanoparticle for the efficient delivery of siRNA to dendritic cells. J Control Release. 2016;225:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe T, Hatakeyama H, Matsuda-Yasui C, et al. In vivo therapeutic potential of Dicer-hunting siRNAs targeting infectious hepatitis C virus. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4750. doi: 10.1038/srep04750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsui H, Sato Y, Hatakeyama H, Akita H, Harashima H. Size-dependent specific targeting and efficient gene silencing in peritoneal macrophages using a pH-sensitive cationic liposomal siRNA carrier. Int J Pharm. 2015;495(1):171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bailey AL, Cullis PR. Modulation of membrane fusion by asymmetric transbilayer distributions of amino lipids. Biochemistry. 1994;33(42):12573–12580. doi: 10.1021/bi00208a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Fan H, Levorse DA, Crocker LS. Ionization behavior of amino lipids for siRNA delivery: determination of ionization constants, SAR, and the impact of lipid pKa on cationic lipid-biomembrane interactions. Langmuir. 2011;27(5):1907–1914. doi: 10.1021/la104590k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yasuda T, Ishida T, Rader DJ. Update on the role of endothelial lipase in high-density lipoprotein metabolism, reverse cholesterol transport, and atherosclerosis. Circ J. 2010;74(11):2263–2270. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Habrant D, Peuziat P, Colombani T, et al. Design of ionizable lipids to overcome the limiting step of endosomal escape: application in the intracellular delivery of mRNA, DNA, and siRNA. J Med Chem. 2016;59(7):3046–3062. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jayaraman M, Ansell SM, Mui BL, et al. Maximizing the potency of siRNA lipid nanoparticles for hepatic gene silencing in vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(34):8529–8533. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Annema W, Tietge UJ. Role of hepatic lipase and endothelial lipase in high-density lipoprotein-mediated reverse cholesterol transport. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2011;13(3):257–265. doi: 10.1007/s11883-011-0175-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kajimoto K, Sato Y, Nakamura T, Yamada Y, Harashima H. Multifunctional envelope-type nano device for controlled intracellular trafficking and selective targeting in vivo. J Control Release. 2014;190:593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smedsrød B, Le Couteur D, Ikejima K, et al. Hepatic sinusoidal cells in health and disease: update from the 14th International Symposium. Liver Int. 2009;29(4):490–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.01979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elvevold K, Smedsrød B, Martinez I. The liver sinusoidal endothelial cell: a cell type of controversial and confusing identity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294(2):G391–G400. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00167.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akhter A, Hayashi Y, Sakurai Y, Ohga N, Hida K, Harashima H. A liposomal delivery system that targets liver endothelial cells based on a new peptide motif present in the ApoB-100 sequence. Int J Pharm. 2013;456(1):195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Akhter A, Hayashi Y, Sakurai Y, Ohga N, Hida K, Harashima H. Ligand density at the surface of a nanoparticle and different uptake mechanism: two important factors for successful siRNA delivery to liver endothelial cells. Int J Pharm. 2014;475(1–2):227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abel T, El Filali E, Waern J, et al. Specific gene delivery to liver sinusoidal and artery endothelial cells. Blood. 2013;122(12):2030–2038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-468579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takei Y, Maruyama A, Ferdous A, et al. Targeted gene delivery to sinusoidal endothelial cells: DNA nanoassociate bearing hyaluronanglycocalyx. FASEB J. 2004;18(6):699–701. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0494fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kren BT, Unger GM, Sjeklocha L, et al. Nanocapsule-delivered Sleeping Beauty mediates therapeutic Factor VIII expression in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells of hemophilia A mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(7):2086–2099. doi: 10.1172/JCI34332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bartsch M, Weeke-Klimp AH, Meijer DK, Scherphof GL, Kamps JA. Massive and selective delivery of lipid-coated cationic lipoplexes of oligonucleotides targeted in vivo to hepatic endothelial cells. Pharm Res. 2002;19(5):676–680. doi: 10.1023/a:1015318415705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bartsch M, Weeke-Klimp AH, Morselt HW, et al. Optimized targeting of polyethylene glycol-stabilized anti-intercellular adhesion molecule 1 oligonucleotide/lipid particles to liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67(3):883–890. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khan OF, Zaia EW, Yin H, et al. Ionizable amphiphilic dendrimer-based nanomaterials with alkyl-chain-substituted amines for tunable siRNA delivery to the liver endothelium in vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(52):14397–14401. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen VH, Lee BJ. Protein corona: a new approach for nanomedicine design. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:3137–3151. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S129300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

In vivo silencing activity of YSK05-LNP (pKa 6.50) and YSK05/12-LNP (pKa 7.15) in the lung and spleen.

Notes: Mice were intravenously injected with the LNPs encapsulating a mixture of siRNA (siCD31:siFVII 1:1 ratio) at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg of each type of siRNA. After 24 hours, the level of CD31 mRNA in the lung (A) and spleen (B) was measured by means of qRT-PCR. The reference genes were TIE2 in the lung and GAPDH in the spleen. *P<0.05, nonrepeated ANOVA followed by an SNK test; data represent mean±SD (n=4).

Abbreviations: FVII, coagulation factor VII; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; mRNA, messenger RNA; NS, not significant; NT, non-treated; pKa, acid dissociation constant; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; TIE2, angiopoietin receptor.

Biodistribution of LNPs.

Notes: Mice were intravenously injected, regardless of their body weight, with 200 µL of LNPs encapsulating 10 µg siRNA (assuming a mouse body weight of 20 g, the injected dose will be 0.5 mg siRNA/kg). In the LNPs, either the lipids were labeled with DiD or the siRNA was labeled with AF647. At 30 minutes after injection, the mice were sacrificed and body organs (liver, lung, kidneys, and spleen) were collected and fluorescence of either the lipids or the siRNA was observed using FluorVivo 300 small animal fluorescence imaging (A). The biodistribution of lipids (B) and siRNA (C), respectively, was further quantified using ImageJ software. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, nonrepeated ANOVA followed by an SNK test; data represent the mean±SD (n=3).

Abbreviations: AF647, alexafluor 647; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; siRNA, short interfering RNA.

Table S1.

List of siRNA sequences used in this study

| siRNA | Sense strand (5′–3′) | Antisense strand (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| siFVII | GGAucAucucAAGucuuACT*T | GuAAGAcuuGAGAuGAuccT*T |

| siCD31-1 | GCACAGUGAUGCUGAACAATT | UUGUUCAGCAUCACUGUGCTT |

| siCD31-2 | GUGCAUAGUUCAAGUGACATT | UGUCACUUGAACUAUGCACTT |

| siCD31-3 | GCAAGAAGCAGGAAGGACATT | UGUCCUUCCUGCUUCUUGCTT |

| Cy5-siGFP | AcAuGAAGcAGcACGACuUT*T | AAGUCGUGCUGCUUCAUGUT*T-Cy5 |

| AF647-siGL4 | AF647-CCGUCGUCUUCGUGAACAATT | UUGCUCACGAAUACGACGGTT |

| siGL4 | CCGUCGUCUUCGUGAACAATT | UUGCUCACGAAUACGACGGTT |

Notes: 2′-OMe-modified nucleotides are depicted in lowercase letters, 2′-fluoro-modified nucleotides are shown in bold lowercase letters, and phosphorothioate linkages are denoted by asterisks. The siCD31-1, -2, and -3 were mixed together in advance.

Abbreviations: AF647, alexafluor 647; FVII, coagulation factor VII; GFP, green fluorescent protein; siRNA, short interfering RNA.

Table S2.

List of PCR primers used in this study

| Gene | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| GAPDH | AGCAAGGACACTGAGCAAG | TAGGCCCCTCCTGTTATTATG |

| ACTB | AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC | CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT |

| CD31 | TACAGTGGACACTACACCTG | GACTGGAGGAGAACTCTAAC |

| TIE2 | GACCAGACTGTAAGCTCAG | AATCCTCTATCTGTGGAGTC |

Abbreviations: ACTB, beta-actin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TIE2, angiopoietin receptor.

Table S3.

Physical characteristics of the LNPs

| Lipid composition

|

pKa | Size (nm) | Number mean (nm) | PDI | ζ-potential (mV) | EE of siRNA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YSK05 (mol%) | YSK12-C4 (mol%) | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| 70 | 0 | 6.50 | 84.02 ± 6.82 | 58.52 ± 3.49 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 1.70 ± 4.59 | 94.82 ± 0.64 |

| 50 | 20 | 7.15 | 85.59 ± 8.22 | 55.71 ± 2.91 | 0.17 ± 0.08 | 6.12 ± 1.46 | 95.32 ± 1.12 |

| 35 | 35 | 7.50 | 84.89 ± 11.79 | 56.31 ± 7.80 | 0.14 ± 0.08 | 7.75 ± 2.83 | 96.18 ± 1.73 |

| 20 | 50 | 7.75 | 92.86 ± 10.27 | 56.55 ± 8.01 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 8.97 ± 1.74 | 97.58 ± 0.96 |

| 0 | 70 | 8.00 | 92.61 ± 11.47 | 51.72 ± 0.99 | 0.22 ± 0.10 | 11.63 ± 1.56 | 97.41 ± 0.67 |

Notes: After preparing LNPs that have the composition YSK05/YSK12 C4/Cholesterol/mPEG2k-DMG=(70-X):X:30:2 mol% of total lipids (X=0~70) by t-BuOH dilution method, the pKa was measured using a TNS assay; size, number mean, PDI, and ζ-potential were measured using DLS; EE of siRNA was measured using RiboGreen assay. Data represent mean±SD (n=3).

Abbreviations: DLS, dynamic light scattering; EE, encapsulation efficiency; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; PDI, polydispersity index; mPEG2k-DMG, 1,2-Dimirystoyl-sn-3-glycero methoxypolyethyleneglycol 2000 ether; pKa, acid dissociation constant; siRNA, short interfering RNA; t-BuOH, tertiary butanol; TNS, 6-(p-toluidino)-2-naphthalenesulfonic acid.