Abstract

Objectives

Empirical investigations of cumulative dis/advantage typically treat health inequality as an intraindividual process rooted in early-life conditions and operating within the span of the individual life course, while literature on processes of intergenerational transmission has historically focused on socioeconomic mobility, largely overlooking health. The current study examines the persistence of work disability across generations and multiple explanations for this relationship, including the role of early-life disadvantage, childhood health, educational attainment, and social mobility.

Methods

We model latent classes of midlife work disability characterized by timing and stability using longitudinal data from the intergenerational component of the U.S. Panel Study of Income Dynamics (N = 3,328). Latent class analysis captures the initial risk of experiencing a work disability and how this risk changes across mid-life as a function of early-life conditions, childhood health, educational attainment, mobility, and parent’s work disability.

Results

Early disadvantage, childhood health, and educational attainment were associated with patterns of midlife work disability, and although upward mobility provided some protection, intergenerational continuity in health remained net of all of these factors.

Discussion

Findings support the importance of looking beyond the individual life course to the transmission of health inequality across generations within families.

Keywords: Cumulative dis/advantage, Early origins of health, Health disparities, Life course analysis, Work disability

An important facet of life course research is its recognition of the importance of linked lives and the intergenerational context of life course processes (Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003). Despite great interest in early-life influences on later life health, studies have not adequately or explicitly incorporated the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage and the effects of social mobility across generations within families into their investigations. Research typically investigates health inequality as an intraindividual process rooted in early-life conditions and operating within the span of the individual life course, only implicitly addressing the intergenerational transmission of health inequality across generations. At the same time, literature on processes of intergenerational transmission has focused largely on class mobility, often by examining educational attainment, occupational location, intergenerational earnings and wealth persistence (for a review, see Erikson & Goldthorpe, 2002) while largely overlooking the continuity in health across generations.

The goal of this analysis is to integrate these bodies of literature in an investigation of the importance of considering linked lives and the intergenerational transmission of health for our understanding of health inequality. The length and richness of the intergenerational component of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) provides one of the few opportunities to observe indicators of health in the parent (G1) and adult child (G2) generations at roughly the same stage in their life course and allows the long-term observation and analysis of prospective measures of early-life environment as well as mobility through midlife. We examine potential explanations for the intergenerational persistence of health identified in multiple literatures, including the role of early-life disadvantage, the role of poor childhood health, and low educational attainment. In addition, we examine the extent to which socioeconomic mobility across generations within families contributes to our understanding of the influence of the health of the previous generation.

We use work disability as our measure of health for the G1 and G2 generations for both conceptual and practical reasons. It is the only measure of health consistently included in the early years of the PSID that is asked of both generations over long periods of time, and importantly, work disability provides a global indicator of health in midlife that fits with a social model recognizing health as a form of life course capital which can be protected or depleted within the individual life course and transmitted across generations (O’Rand & Henretta, 1999). Health capital consists of a heterogeneous group of physical and mental states which intersect with social roles and institutions, and this focus, rather than an exclusive focus on specific diseases and conditions, is important for studies of inequality as it suggests one avenue through which social class may be reproduced across generations (Priestley, 2005; Verbrugge & Jette, 1994).

Intragenerational Accumulation and the Intergenerational Transmission of Health

Guided in part by the theory of cumulative dis/advantage (CAD) (Dannefer, 1987, 2003; O’Rand, 1996), the life course perspective (see Elder et al., 2003) emphasizes the early-life origins of later life outcomes. Research on social stratification and mobility theorizes CAD as a mechanism through which relative position early in life generates further gains or losses across the life course, resulting in the over-time accumulation of advantages for one individual or group relative to another (for discussion, see Diprete & Eirich, 2006; Rosenbaum 1979). Although initially applied to the accumulation of financial resources and status attainment, CAD has since heavily influenced contemporary studies of adult health. This field has seen a proliferation of research interested in the accumulative effects of early environment and exposures to disadvantage on later-life health, as well as research on the more proximal mechanisms between disadvantage and health such as stress, health behaviors, and exposure to toxins and hazards (see, e.g., Ferraro, Schafer, & Wilkinson, 2016; Goosby, 2013; Lloyd & Taylor, 2006; McEwen & Wingfield, 2003; Pais, 2014; O’Rand & Hamil-Luker, 2005; Willson & Shuey, 2016). Empirical applications of CAD focus primarily on the accumulative processes associated with advantage and disadvantage within an individual life course as a mechanism for generating growing intracohort inequality at the population level (e.g., Brown, O’Rand, & Adkins, 2012; Dupre, 2007; Lynch, 2003; Wickrama, Noh, & Elder, 2009; Willson, Shuey, & Elder, 2007). Other research loosely references theories of accumulation in an attempt to isolate the effects of early-life disadvantage on later life health outcomes in the presence of measures of midlife resources (e.g., Bartley & Plewis, 2007; Brennan & Spencer, 2014; Guralnik, Butterworth, Wadsworth, & Kuh, 2006; Latham, 2015; Lynch & Smith, 2005; Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011; Montez & Hayward, 2014). More recently, research has attempted to assess the benefits of social mobility by determining whether the harmful effects of early insults can be attenuated by adult resources, largely limited to comparisons of the direct and indirect effects of resources from discrete life stages and often producing conflicting results (Graham, 2002; Hallqvist, Lynch, Bartley, Lang, & Blane, 2004; Pudrovska & Anikputa, 2013; Rosvall, Chaix, Lynch, Lindstrom, & Merlo, 2006).

Despite conceptual cross-fertilization between the life course perspective’s recognition of the importance of accumulative processes (Elder et al., 2003) and social science’s core interest in stratification and mobility, empirical investigations of adult health primarily focus on intraindividual processes and pathways and their early-life origins rather than giving explicit attention to the intergenerational transmission and reproduction of health inequality across generations within families. Insight on intergenerational persistence can be found in the literature on the transmission of socioeconomic status within families, which is interested in understanding to what extent parents’ resources provide opportunities or close paths for their children’s status attainment (see, e.g., Bowles & Gintis, 2002; Breen & Jonsson, 2005; Corcoran, 2001; Mayer & Lopoo, 2005; Solon, 1992; Wagmiller, Lennon, Kuang, Alberti, & Aber, 2006).

The inclusion of health in the discussion of intergenerational transmission largely has been limited to an interest in the role of childhood health as a “mechanism through which socioeconomic status is transferred across generations” (Haas, 2006: 339). Adults in poor health are more likely to have experienced disadvantaged socioeconomic origins and poor childhood health, which in turn affects human capital accumulation and mobility across their life course (Carvalho, 2012; Case, Fertig, & Paxson, 2005; Currie, 2009; Palloni, Milesi, White, & Turner, 2009). Additionally, there has been some recent interest in the role of the health of one generation on the educational attainment of the next. For example, Boardman and colleagues (2012) find that parents’ poor midlife health leads to lower educational attainment of their children and they argue that this could be due in part to health’s effect on labor market attachment and resources available to support children’s needs. Other explanations for intergenerational continuity include the transmission of health behaviors (e.g., Chassin, Presson, Rose, & Sherman, 1998; Wickrama, Conger, Wallace, & Elder, 1999) and the social contexts in which both health and socioeconomic status are practiced and reproduced (Boardman, 2009; Boardman, Alexander, Miech, MacMillan, & Shanahan, 2012; Bourdieu, 1990).

In summary, adult health reflects the accumulation of exposures to advantages and disadvantages across the individual life course as well as the transmission of resources and practices across generations within one’s family of origin, which forms the starting berth from which children are launched and inequality is reproduced (Rosenbaum, 1979). In this study, we integrate previous conceptual and empirical work to consider health as a form of life course capital that may be transmitted across generations. Health has the potential to negatively affect one’s own labor force attachment, and the next generation’s childhood health, educational attainment, and subsequent midlife health and labor force participation. A strength of work disability as a measure of midlife health is that it focuses on the intersection of impairment and social context, rather than on the impairment or health condition itself (Nagi, 1991; Priestley, 2005; Verbrugge & Jette, 1994). Health conditions that are limiting in one occupation may not be in another, or in a workplace that provides adequate accommodations compared to one that does not. Our measure captures the experience of a physical or mental health condition that is perceived by the respondent as significant enough to impair the ability to work in his or her given occupation, and more explicitly links health with the socioeconomic consequences of an individual’s ability to participate in social institutions, such as work (Kelley-Moore, 2010).

In this research, we analyze 47 years of multigenerational longitudinal data from the PSID to: (a) examine continuity across generations in midlife work disability, which provides insight into the ways in which inequality is reproduced through labor market attachment. (b) Second, we examine the effect of multiple indicators of childhood socioeconomic disadvantage, measured prospectively in childhood, on patterns of G2 midlife work disability. (c) We next examine the association between G1 and G2 work disability net of G2 childhood health and G2 educational attainment. (d) Finally, we examine the effect of intergenerational mobility on work disability in midlife net of the above. Is the health of the upwardly mobile significantly different than that of those who have persistently low or stably high income?

DATA AND METHODS

Data

We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), which began in 1968 as an annual survey with a representative sample of approximately 4,800 American households and information on almost 18,000 individuals residing in those households (PSID, 2016). In 1997, the survey switched to a biennial format, and the latest available survey wave at the time of this analysis was 2015. The PSID maintains representativeness of the nonimmigrant U.S. population as children and adults who split-off from original PSID households are followed in their new household (Fitzgerald, 2011). The multigenerational design and long span of data collection allows us to use data on childhood socioeconomic environment provided prospectively by parents at the time the child was in the parental home. We limit the sample to respondents (G2) who were newborn to 12 years old in 1968 and lived in a family in which the member of the parent generation (G1) identified as the household head was 20–65 in 1968 (N = 4,443). After attrition and minimal missing data on covariates, the final sample size for the analyses is 3,328.

Attrition may weaken the representativeness of longitudinal surveys over time, which is particularly concerning in research on health and aging. Multiple studies monitoring the effects of attrition in the PSID show that the weighted sample maintains its representativeness on many characteristics (see Fitzgerald, 2011 for review). Our own investigation suggests attrition is only minimally related to the socioeconomic characteristics of the G2 families of origin, but may lead to conservative estimates of the association of childhood socioeconomic circumstances and health in adulthood (see the Supplementary Material for further details).

Dependent Variable

G2 work disability

The dependent variable in this analysis is latent classes of G2 work disability. G2 respondents are coded “1” in each wave they answered ‘yes’ to the question, “Do you have any physical or nervous condition that limits the type of work or the amount of work you can do?” This includes any health-related issue that prevents someone from working to the extent he or she would have without the condition, such as short-term physical injuries, chronic conditions, long-term disabilities, or mental health issues. Estimation of the latent classes of G2 work disability is described in further detail below. Indicators are included from the year the G2 respondent turned 35 to the last wave of data collection in 2015 when respondents were aged 47–59. The oldest respondents turned 35 in 1992, the youngest in 2003. Because the PSID became biennial in 1997, some respondents were first measured at age 36.

Independent Variables

G1 work disability

We measure work disability in the G1 generation prospectively with the same question used to assess G2 respondents’ work disability (described above). If the G1 household head reported a work disability in any year before the G2 was 18, G1 ever work disabled = 1. Until 1981 work disability was asked only of household heads. The PSID defines the family unit “head” as the person with the most financial responsibility for the family unit. When the study began, the husband (if present) was designated the Head to conform to Census Bureau definitions and this practice has been maintained for consistency. Family units are female-headed if no husband is present or he is incapacitated. In our sample, approximately 25% of family units were female-headed at some point during the G2 respondents’ childhood.

Social mobility

Following Wightman and Danziger (2014), our measure of social mobility uses the average annual percentile ranking in the distribution of per capita household income of the G1 and G2 generations. At each relevant wave, we divide total household income from all sources by the number of household members and calculate the distribution of this value, weighted with the appropriate year’s weight, to produce an annual percentile ranking. We then average the annual percentiles over the relevant age ranges (G1 income from 1968 until G2s are aged 18; G2 income from survey waves in which G2s are aged 30–35). Relatively low income reflects an average percentile ranking of less than 50 (below the median), and relatively high income is an average income percentile ranking that is greater than or equal to 50 (above the median). We tested multiple mobility measures with finer gradations of the income distribution; for example income ranking thresholds of 25%, 50%, and 75%, but the combinations resulted in relatively small cell sizes for some pairs. We also considered a measure using the difference between G1 and G2 average income percentiles and determining thresholds for comparison, but previous research (Wightman & Danziger, 2014) indicated that findings are sensitive to the somewhat arbitrary decision about threshold lines, which makes this a less satisfactory approach.

We interact indicators of G1’s and G2’s income status to create categories that indicate whether G2s were doing better, worse, or roughly the same as the parent generation at a similar point in the life course. This resulted in four mutually exclusive categories. Persistently below-median income includes respondents whose average ranking falls below the median in adulthood and who resided in households with average income below the median as children. Upwardly mobile respondents have income above the median in adulthood but were raised in lower income households. Downwardly mobile respondents grew up in higher income families but have lower income in adulthood. The stably above-median income respondents are those who were raised in a household with income above the median and who on average have income above the median in adulthood.

G2 early-life disadvantage

Indicators of disadvantaged early origins are measured prospectively through repeated observations of the G2’s household head. These questions, asked of the G1 generation before G2 children were age 18, include: whether the G2’s household head was ever unemployed, ever female, had less than a high school education, or was non-white (=1).

G2 childhood health

A retrospective question fielded in 1999 asked respondents to rate their health before the age of 16. G2 childhood poor health = 1 if the respondent reported that his/her health was fair or poor. Because this variable has more missing cases than other variables in the analysis (465 missing cases, or 14%), we include a variable indicating a missing value on childhood health to retain these respondents in the analysis and to examine whether missing cases are associated with the dependent variable (childhood health missing = 1).

Other G2 characteristics

Respondents’ highest level of educational attainment is measured with a series of dummy variables comparing less than a high school degree (=1) and high school degree but less than college (=1) to college degree or postgraduate degree. The analysis compares white (=0) and non-white respondents (=1), which consist primarily of African American as well as a small number of Hispanic and Asian sample members. In addition, sex (male = 1) and age (continuous) are included. Descriptive statistics for all variables are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proportions and Means, Weighted, Panel Study of Income Dynamics

| Variable | Mean/proportion |

|---|---|

| G2 Characteristics | |

| Ever work disabled | 0.30 |

| Age in 1968 (0–12) | 7.0 |

| Non-white | 0.16 |

| Male | 0.47 |

| Education | |

| < high school | 0.09 |

| High school degree | 0.64 |

| College | 0.27 |

| Child health poor | 0.03 |

| Child health missing | 0.14 |

| G2 Early-Life Disadvantage | |

| G1 < high school | 0.43 |

| G1 Non-white | 0.14 |

| G1 Ever female | 0.24 |

| G1 Ever unemployed | 0.14 |

| G1 Health | |

| Ever work disabled | 0.36 |

| Social Mobility | |

| Persistently below median income | 0.30 |

| Stably above median income | 0.35 |

| Downward mobility | 0.18 |

| Upward mobility | 0.16 |

Note: N = 3,328.

Analytic Strategy

Conceptually, the life course literature defines trajectories as “long-term patterns of stability and change, often including multiple transitions, that can be reliably differentiated from alternate patterns” (George, 1993: 358; Elder et al., 2003). In this analysis we conceptualize work disability as a long-term process that takes the form of a trajectory operating across biographical and historical time. In addition, this measure of life course health can be described by dimensions including, but not limited to, pattern, sequence, stability, timing, and unlike some health conditions, reversibility (see Clipp, Pavalko, & Elder, 1992; Pavalko, 1997).

We model G2 trajectories of work disability using repeated-measures latent class analysis (RMLCA) with PROC LCA in SAS 9.4 (Lanza, Dziak, Huang, Wagner, & Collins, 2015). RMLCA is a finite mixture model that identifies mutually exclusive and exhaustive latent classes of individuals who are homogenous in their observed responses of patterns of experience, such as work disability, over time (Collins & Lanza, 2010; Lanza et al., 2015; McCutcheon, 1987; Nagin, 2005). RMLCA allows for the identification of unique patterns of work disability because the specification of a functional form for individual change over time is not required (see the Supplementary Material for further discussion of the choice of RMLCA to model trajectories of work disability). When latent classes are estimated with repeated measures of a single item, such as work disability status, the latent classes “represent the common patterns observed in the variable over time: trajectories” (Lynch & Taylor, 2016: 34). RMLCA allows for the simultaneous identification of predictors of latent class membership within a multinomial regression framework (Collins & Lanza, 2010; Nagin, 2005).

After identifying latent classes of work disability, we estimate stepwise models predicting entry into these latent classes in four models that correspond to our research questions. Model 1 includes basic sociodemographic controls and G1 work disability as predictors of G2 work disability trajectories to address RQ1. To assess the effect of G1 health net of G2 early-life disadvantage (RQ2), G2 childhood health and educational attainment (RQ3), as well as the effect of social mobility on G2 health (RQ4), we estimate a series of multinomial logistic regression models in PROC LCA. Although methods have been developed to enable mediation analysis in binary logistic regression models (e.g., Breen, Karlson & Holm, 2013), they are not readily available for LCA multinomial logistic regression. We therefore note the effect of the G1 health coefficient net of other variables in the model, but do not test for the effects of mediation.

RESULTS

Identifying Trajectories of Work Disability

Our first goal is to identify the number of latent classes representing distinct trajectories of work disability among G2 respondents in midlife. Model selection in RMLCA is theoretically motivated and based on a combination of parsimony, fit statistics, and the interpretability of models (Collins & Lanza, 2010; Nagin, 2005). Based on these factors we selected a model allowing four trajectories of work disability. The Supplementary Material file details the procedure we used for determining the optimal number of classes and includes a table of model fit statistics.

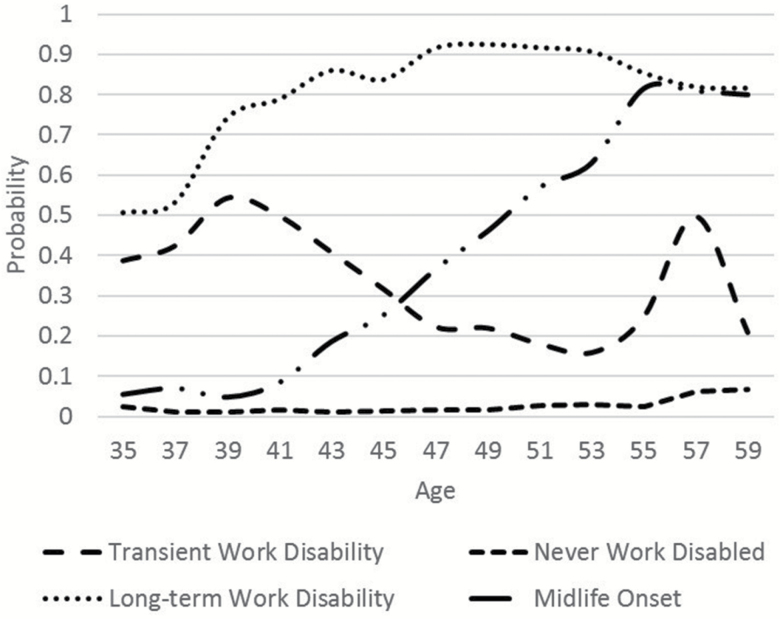

Figure 1 provides a characterization of the four trajectories of work disability. The graph plots the item response probabilities conditional on membership in a given latent trajectory by age and estimates of the proportion of the sample in each latent class (weighted). Most of the G2 sample had a low probability of work disability in midlife (“Never Work Disabled”; 79%). In contrast, approximately 9% of the sample had a relatively high likelihood of experiencing disability in their 30s that steeply increased and was maintained through the study period (“Long-term Work Disability”). The “Late Midlife Onset” class (referred to as “Late Onset”; 8%) is characterized by a steadily increasing probability of a work disability as respondents entered their 50s. Respondents in the “Transient Work Disability” class (4%) experienced episodic health conditions that limited their ability to work. We plotted a random subset of cases from this class and their trajectories of work disability evidenced frequent movement in and out of work disability (not shown), resulting in an average probability of work disability that was consistently elevated for the duration of the observation period.

Figure 1.

Item-response probabilities for a four-class longitudinal latent class model of work disability trajectories, PSID (N = 3,328). PSID = Panel Study of Income Dynamics.

Predicting Trajectories of Work Disability

The second stage of our analyses builds stepwise models that correspond to our research questions and predict the likelihood of experiencing the various trajectories of work disability. In Table 2, Models 1–4 report odds ratios of G2’s increased or decreased likelihood of experiencing each work disability trajectory relative to the “No Work Disability” latent class. In analyses not shown here, we rotated the reference category to test for significant differences in the effects of the key independent variables on membership in the work disability latent classes and report the results below.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios from Multinomial Logistic Regressions Predicting Trajectories of G2 Work Disability

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transient | Long-term | Late onset | Transient | Long-term | Late onset | Transient | Long-term | Late onset | Transient | Long-term | Late onset | |

| Intercept | .002*** | .042*** | .233 | .003*** | .029*** | .154** | .002*** | .015*** | .142*** | .004*** | .019*** | .118*** |

| G2 Age | 1.122** | 1.027 | .981 | 1.105*** | 1.029 | .990 | 1.098*** | 1.026 | .986 | 1.090*** | 1.025 | .989 |

| G2 Non-white | 1.149 | .90 | 1.090 | .479 | .733 | 1.026 | .413** | .933 | 1.361 | .406** | .906 | 1.372 |

| G2 Male | .882 | .687* | 1.008 | .917 | .714* | .988 | .878 | .761* | .987 | .859 | .795 | .990 |

| G1 Health | ||||||||||||

|

Ever work disabled |

1.789** | 1.840*** | 1.366 | 1.609** | 1.609*** | 1.182 | 1.476** | 1.445** | 1.088 | 1.434* | 1.360* | 1.107 |

| G2 Early-Life Disadvantage | ||||||||||||

| G1 < H.S. degree | --- | --- | --- | .864 | 1.981*** | 1.200 | .715 | 1.465** | 1.103 | .745 | 1.261 | 1.106 |

| G1 Non-white | --- | --- | --- | 2.754** | .954 | .898 | 2.772*** | .713 | .643 | 2.457** | .693 | .671 |

| G1 Ever female | --- | --- | --- | .933 | 1.005 | 1.377* | 1.007 | .984 | 1.329* | .995 | .991 | 1.304* |

| G1 Ever unemployed | --- | --- | --- | 1.457 | 1.218 | 1.284 | 1.281 | 1.179 | 1.240 | 1.251 | 1.167 | 1.226 |

| G2 Educational Attainment | ||||||||||||

| <H.S. Degree | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 3.000*** | 4.639** | 1.930** | 2.977*** | 3.400*** | 1.919** |

| H.S. Degree (vs College) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.662** | 2.552*** | 1.309 | 1.647* | 1.988*** | 1.320 |

| G2 Childhood Health | ||||||||||||

| Child health poor | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 5.036*** | 3.823*** | 1.549 | 4.863*** | 3.693*** | 1.592 |

| Child health missing | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.002 | 1.272 | 1.544* | .967 | 1.240 | 1.480* |

| Social Mobility | ||||||||||||

| Persistently below median | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .826 | 1.407* | 1.039 |

| Stably above median | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .792 | .683 | 1.134 |

| Downward mobility (vs upward mobility) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .546* | 1.302 | 1.126 |

Reference category = Never Work Disabled.

Results of likelihood ratio tests comparing the difference in the deviance of Model 1 and Models 2–4 to the appropriate chi-squared critical value based on the difference in degrees of freedom indicate that Models 3 and 4 significantly improve model fit compared to Model 1.

Note: N = 3,328. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Intergenerational continuity in health

Our first research question asks the extent to which is there an association between G1 midlife work disability and G2’s work disability trajectories. In Model 1 of Table 2, G1 work disability significantly increased the likelihood that G2s experienced a transient (OR 1.789, p < .01) or long-term (OR 1.840, p < .001) work disability trajectory in midlife (compared Never Disabled). Further analysis (data not shown) indicated that the association between G1 and G2 midlife work disability did not differ significantly across the work disability latent classes; in other words, G1 midlife work disability significantly increased the likelihood of G2 experiencing a transient or long-term trajectory compared to never disabled, but not compared to each other or to late midlife onset. Finally, men were less likely than women to experience long-term work disability in midlife (OR .687, p < .05), and older respondents were more likely to be classified in the Transient than Never Work Disabled class (OR 1.122, p < .01).

The role of disadvantaged early origins

Model 2 of Table 2 adds measures of childhood disadvantage. Measures of disadvantage had distinct effects on trajectories of work disability. For example, children who grew up in less educated families had a greater likelihood of a long-term work disability trajectory compared to the never work disabled (OR 1.981, p < .001) and compared to those with transient work disability (data not shown). Children in families with non-white heads were more likely to have a transient work disability trajectory than to never have a work disability (OR 2.754, p < .01), and children who ever lived in a female-headed household were more likely to experience the onset of a work disability in late midlife (Late Midlife Onset) than never have a work disability (OR 1.377, p < .01). Net of childhood disadvantage, the effect of G1’s work disability remained statistically significant for transient and for long-term work disability.

Childhood health and human capital accumulation

Research suggests that parents’ health and childhood disadvantage may operate through child poor health and/or through educational attainment to affect children’s health in adulthood. In Model 3, we introduce poor health in childhood, which significantly increased the likelihood of both transient (OR 5.036, p < .001) and long-term (OR 3.823, p < .001) work disability. G2 respondents who were missing on this retrospective measure were significantly more likely to experience late onset of work disability (OR 1.549, p < .01), suggesting that they were more likely to have left the PSID before the childhood health question was first asked in 1999.

Model 3 also adds G2’s education and indicates that, compared to those with a college degree, lower levels of education significantly increases one’s odds of experiencing work disability. We estimated models that added child health and education separately and the results were consistent with Model 3. The one exception is that for those in the Late Onset class, having a high school degree did not differ significantly from a college degree. With the addition of childhood health, the coefficient for G1 work disability remained significant for transient and for long-term work disability.

Social mobility

Model 4 adds variables measuring social mobility. Compared to the upwardly mobile, respondents persistently below-median income were more likely to experience a long-term work disability trajectory than to not be work disabled in midlife (OR 1.407, p < .01). In other words, upward mobility offers some protection from work disability in midlife. The downwardly mobile were less likely to experience transient work disability than to never experience disability compared to the upwardly mobile (OR 0.546, p < .05), which perhaps indicates the long-term protective effects of childhood, as the downwardly mobile experienced income above the median in childhood while the upwardly mobile began life with income below the median. Comparing stably above-median income versus upward mobility suggests that upward mobility protects from disability to a lesser extent, but this coefficient only reached statistical significance in a one-tailed test. Further analysis (data not shown) demonstrates that compared to the upwardly mobile, respondents persistently below-median income were significantly more likely to experience a long-term work disability than a transient work disability trajectory, and the downwardly mobile were significantly less likely to experience the transient trajectory than all of the other trajectories of work disability.

In summary, the results suggest that childhood advantage offers protection from work disability even in the face of downward mobility, and that upward mobility provides some health benefits as well, but not to the same extent as stably higher income conditions. The effects of all other variables, including G1 work disability, remained significant and largely unchanged.

Discussion

This study contributes to our understanding of the ways in which health in midlife reflects both one’s own history of advantage and disadvantage as well as that of previous generations. We aimed to integrate the burgeoning body of literature on the early-life origins of health with the concept of linked lives and the intergenerational transmission of resources to consider the intergenerational transmission of health inequality. Possible pathways through which social class may be reproduced across generations include the effect of parent’s work disability on the early-life disadvantage and poor childhood health of the next generation, which in turn influences their educational attainment and subsequent health and labor force attachment. The PSID provides one of few opportunities to observe these pathways prospectively. Our findings indicate that the experience of a work disability in the parent generation increases the likelihood of work disability in the next generation, net of the significant effects of poor childhood health, early-life disadvantage, and educational attainment. In addition, “one of the key issues in our understanding of inequality is the role played by intergenerational mobility in loosening or tightening the link between the socioeconomic positions, rewards, and statuses of one generation and those of the next” (Mare, 2011:5). To this end, we found that upward mobility does provide some protection from the onset of work disability in midlife, as the upwardly mobile were less likely than the persistently disadvantaged to experience a trajectory of long-term disability. The long-term benefits of advantaged childhood circumstances also were evident, as the downwardly mobile—those who began life in a family with above-median income but experience below-median income in adulthood—were less likely than the upwardly mobile to experience transient disability. However, the intergenerational persistence of health within families remained in the presence of controls for childhood disadvantage, poor child health, lower human capital accumulation via education, and social mobility.

Although a number of possible explanations outlined in the literature are included in our models, the enduring association between G1 and G2 work disability could be the result of a number of underlying mechanisms that we are unable to measure. Health penalties associated with early, off-time caregiving for work-disabled parents, fewer resources to support children resulting from parents’ shortened work life, genetic factors, and health-related behaviors may at least partially explain the persistence of health across generations but are beyond the scope of this investigation. In addition, drawing on Bourdieu (1990), Boardman and colleagues (2012) explain that distal social factors may structure the social contexts that influence the health of multiple generations. Parental health may provide important information about the social contexts in which both health and socioeconomic status are practiced—more information than socioeconomic indicators alone provide. Therefore, the intergenerational transmission of health may be in part the result of the same broad lifestyle that both shapes an individual’s social world and reproduces it (Boardman et al., 2012; Bourdieu, 1990). An additional consideration that could be explored in future research is the contribution of occupational continuity across generations and the extent to which intergenerational mobility into occupations that are considered safer and less detrimental to health and well-being, as well as more likely to offer workplace accommodations, contributes to better health across generations.

Despite the strengths of the PSID’s long-term intergenerational component, there are several factors that should be considered when interpreting the results of the study. First, although our measure of health does not include the specific health condition or type of disability experienced, advancements in medicine and changing social conditions have resulted in disease profiles that differ over the period that the two generations were observed (Jemal, Ward, Hao, & Thun, 2005), making comparable experiences of disease difficult to measure. The measure of work disability used in the analysis is one solution, as it focuses on the intersection of impairment and social context, rather than on the impairment itself, and conceptualizes health as a form of life course capital that can be transmitted across generations. Second, respondents classified by RMLCA as “Always Work Disabled” were characterized by a high probability of impairment at the beginning of the observation period when they were age 36. Due to the left-censoring of work disability data in the analysis, for this group we are not able to determine whether the early onset of a work disability influenced their income in adulthood, which is measured from ages 30–35. Including controls for childhood health and earlier socioeconomic conditions mitigates this problem, and in multivariate models, downward mobility was not significantly associated with this class. Third, our measures of the G1 generation are observed of household heads and not limited to one of the biological parents of the G2 respondents. Although this does not allow for conclusions about genetic predispositions, which is not our aim, it is consistent with an approach that emphasizes the social context imbued by families of origin, as discussed above.

Finally, although the PSID provides the opportunity to include much prospective socioeconomic and demographic data from G2’s childhood, information on childhood health is limited and a less-than-perfect measure, as is the case in most panel data. Recalling health in childhood may be influenced by many factors, including one’s current health, and there are significant missing data on this variable. Because it is likely that people who experienced poor health in childhood are also more likely to attrit and their exclusion may bias results, we retained the missing respondents in the analysis and found they were significantly more likely to have experienced a work disability. Further, in contrast to study designs that only begin following individuals in mid- or later-life and are therefore left-censored, the design of the PSID allows us to investigate potential selection processes that occur early in the life course that may result in less observed heterogeneity among those who are still present in the study in midlife. From our examination of changes in sample composition, described in detail in the Supplementary Material, we determined that attrition potentially weakened, but did not bias, the relationships we observed in our analysis.

Although multiple literatures focus on the influence of early-life conditions on health disparities, the majority of existing research has investigated health within one generation. We extend that here to emphasize the importance of linked lives within families and the role of the intergenerational transmission of health. Recent research has demonstrated the enduring effect of parents’ health on the status attainment of their children; our study provides further evidence for the necessity of explicitly examining health disparities as both causes and consequences of social stratification that are transmitted within families across two, or even multiple generations (Mare, 2011).

Funding

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (120311). The collection of data used in this study was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HD069609) and the National Science Foundation (1157698).

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Author Contributions

A. E. Willson and K. M. Shuey planned and wrote the study together.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bartley M. & Plewis I (2007). Increasing social mobility: An effective policy to reduce health inequalities. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 170, 469–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2006.00464.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman J. D. (2009). State-level moderation of genetic tendencies to smoke. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 480–486. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.134932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman J. D. Alexander K. B. Miech R. A. Macmillan R. & Shanahan M. J (2012). The association between parent’s health and the educational attainment of their children. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 75, 932–939. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles S., & Gintis H (2002). The inheritance of inequality. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16, 3–30. doi: 10.1257/089533002760278686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breen R., & Jonsson J. O (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 223–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122232 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breen R., Karlson K., & Holm A (2013). Total, direct, and indirect effects in logit and probit models. Sociological Methods and Research, 42, 164–191. doi: 10.1177/0049124113494572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D. S. & Spencer A. J (2014). Health-related quality of life and income-related social mobility in young adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 52. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. H. O’Rand A. M. & Adkins D. E (2012). Race-ethnicity and health trajectories: Tests of three hypotheses across multiple groups and health outcomes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53, 359–377. doi: 10.1177/0022146512455333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho L. (2012). Childhood circumstances and the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status. Demography, 49, 913–938. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0120-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A. Fertig A. & Paxson C (2005). The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. Journal of Health Economics, 24, 365–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L. Presson C. C. Todd M. Rose J. S. & Sherman S. J (1998). Maternal socialization of adolescent smoking: The intergenerational transmission of parenting and smoking. Developmental Psychology, 34, 1189–1201. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clipp E. C., Pavalko E. K., & Elder G. H. Jr (1992). Trajectories of health: In concept and empirical pattern. Behavior, Health, and Aging, 2, 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Collins L. M., & Lanza S. T (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9780470567333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran M. 2001. Mobility, persistence, and the consequences of poverty for children: Child and adult outcomes. In Danziger S. & Haverman R. (Eds.), Understanding poverty (pp. 127–161). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J. (2009). Healthy, wealthy, and wise: Socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood, and human capital development. Journal of Economic Literature, 47, 87–122. doi: 10.1257/jel.47.1.87 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D. (1987). Aging as intercohort differentiation: Accentuation, the Matthew effect, and the life course. Sociological Forum, 2, 211–36. doi:0884-8971/87/0202-02 [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D. (2003). Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58, S327–S337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.S327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diprete T. A., & Eirich G. M (2006). Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: A review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 271–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre M. E. (2007). Educational differences in age-related patterns of disease: Reconsidering the cumulative disadvantage and age-as-leveler hypotheses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48, 1–15. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. H. Jr, Johnson M. K., & Crosnoe R (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In Mortimer J. & Shanahan M. (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. doi: 10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson R., & Goldthorpe J. H (2002). Intergenerational inequality: A sociological perspective. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16, 31–44. doi: 10.1257/089533002760278695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro K. F. Schafer M. H. & Wilkinson L. R (2016). Childhood disadvantage and health problems in middle and later life: Early imprints on physical health?American Sociological Review, 81, 107–133. doi: 10.1177/0003122415619617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J. (2011). Attrition in models of intergenerational links in health and economic status in the PSID. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 11, 1–61. doi: 10.2202/1935-1682.2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George L. K. (1993). Socioeconomic perspectives on life transitions. Annual Review of Sociology, 19, 353–73. [Google Scholar]

- Goosby B. J. (2013). Early life course pathways of adult depression and chronic pain. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54, 75–91. doi: 10.1177/0022146512475089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham H. (2002). Building an inter-disciplinary science of health inequalities: The example of lifecourse research. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 55, 2005–2016. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00343-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik J. M. Butterworth S. Wadsworth M. E. & Kuh D (2006). Childhood socioeconomic status predicts physical functioning a half century later. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 61, 694–701. doi:10.1093/gerona/61.7.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas S. A. (2006). Health selection and the process of social stratification: The effect of childhood health on socioeconomic attainment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 339–354. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallqvist J. Lynch J. Bartley M. Lang T. & Blane D (2004). Can we disentangle life course processes of accumulation, critical period and social mobility? An analysis of disadvantaged socio-economic positions and myocardial infarction in the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 58, 1555–1562. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00344-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A. Ward E. Hao Y. & Thun M (2005). Trends in the leading causes of death in the United States, 1970-2002. JAMA, 294, 1255–1259. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore J. (2010). Disability and ageing: The social construction of causality. In Dannefer D. & Phillipson C. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of social gerontology (pp. 96–110), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781446200933.n7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza S. T., Dziak J. J., Huang L., Xu S., & Collins L. M (2015). Proc LCA and Proc LTA Users’ Guide (Version 1.3.2). University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State; http://methodology.psu.edu [Google Scholar]

- Latham K. (2015). The “long arm” of childhood health: Linking childhood disability to late midlife mental health. Research on Aging, 37, 82–102. doi: 10.1177/0164027514522276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd D. A. & Taylor J (2006). Lifetime cumulative adversity, mental health and the risk of becoming a smoker. Health (London, England: 1997), 10, 95–112. doi: 10.1177/1363459306058990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch S. M. (2003). Cohort and life-course patterns in the relationship between education and health: A hierarchical approach. Demography, 40, 309–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J. & Smith G. D (2005). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 1–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch S. M., & Taylor M. G (2016). Trajectory models in aging research. In George L. K. & Ferraro K. F. (Eds.), Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences (8th Edition, pp. 23–51). San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mare R. D. (2011). A multigenerational view of inequality. Demography, 48, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0014-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer S. E., & Lopoo L. M (2005). Has the intergenerational transmission of economic status changed?Human Resources, XL, 40, 169–185. doi: 10.3368/jhr.XL.1.169J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon A. L. (1987). Latent class analysis. Quantitative applications in the social sciences, Series No. 64. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781412984713 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S. & Wingfield J. C (2003). The concept of allostasis in biology and biomedicine. Hormones and Behavior, 43, 2–15. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(02)00024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. E. Chen E. & Parker K. J (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 959–997. doi: 10.1037/a0024768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montez J. K. & Hayward M. D (2014). Cumulative childhood adversity, educational attainment, and active life expectancy among U.S. adults. Demography, 51, 413–435. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0261-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagi S. (1991). Disability concepts revisited: Implications to prevention. In Pope A. M. & Tarlove A. R. (Eds.) Disability in America: Toward a national agenda for prevention (pp. 307–327). Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi: 10.4159/9780674041318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand A. M. (1996). The precious and the precocious: Understanding cumulative disadvantage and cumulative advantage over the life course. The Gerontologist, 36, 230–238. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand A. M. & Hamil-Luker J (2005). Processes of cumulative adversity: Childhood disadvantage and increased risk of heart attack across the life course. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60 (Spec No 2), 117–124. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.Special_Issue_2.S117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand A. M., & Henretta J. C (1999). Age and inequality: Diverse pathways through later life. Boulder, CO: Westview. [Google Scholar]

- Pais J. (2014). Cumulative structural disadvantage and racial health disparities: The pathways of childhood socioeconomic influence. Demography, 51, 1729–1753. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0330-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A. Milesi C. White R. G. & Turner A (2009). Early childhood health, reproduction of economic inequalities and the persistence of health and mortality differentials. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 68, 1574–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panel Study of Income Dynamics (2016). Produced and distributed by the Survey Research Center. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko E. K. (1997). Beyond trajectories: Multiple concepts for analyzing long-term process. In Hardy M. (Ed.), Studying aging and social change (pp. 129–147). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Priestley M. (2005). Disability and social inequalities. In Romero M. & Margolis E. (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to social inequalities (pp. 372–395). Oxford: Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9780470996973.ch17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pudrovska T., & Anikputa B (2013). Early-life socioeconomic status and mortality in later life: An integration of four life-course mechanisms. Journals of Gerontology, 69B, 451–460. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum J. E. (1979). Tournament mobility: Career patterns in a corporation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 220–241. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2392495 [Google Scholar]

- Rosvall M. Chaix B. Lynch J. Lindström M. & Merlo J (2006). Similar support for three different life course socioeconomic models on predicting premature cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality. BMC Public Health, 6, 203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solon G. (1992). Intergenerational income mobility in the United States. The American Economic Review, 82, 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M. & Jette A. M (1994). The disablement process. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 38, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagmiller R. L., Lennon M. C., Kuang L., Alberti P. M., & Aber J. L (2006). The dynamics of economic disadvantage and children’s life chances. American Sociological Review, 71, 847–866. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama K. A. Conger R. D. Wallace L. E. & Elder G. H. Jr (1999). The intergenerational transmission of health-risk behaviors: Adolescent lifestyles and gender moderating effects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 258–272. doi: 10.2307/2676351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama K. A. S., Noh S., & Elder G. H. Jr (2009). An investigation of family SES-based inequalities in depressive symptoms from early adolescence to emerging adulthood. Advances in Life Course Research, 14, 147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman P., & Danziger S (2014). Multi-generational income disadvantage and the educational attainment of young adults. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 35, 53–69. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2013.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willson A. E. & Shuey K. M (2016). Life course pathways of economic hardship and mobility and midlife trajectories of health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 57, 407–422. doi: 10.1177/0022146516660345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson A. E., Shuey K. M., & Elder G. H. Jr (2007). Cumulative advantage processes as mechanisms of inequality in life course health. American Journal of Sociology, 112, 1886–1924. doi: 10.1086/512712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.