Abstract

Objectives

Many studies of daily life have framed stressors as unpredictable disruptions. We tested age differences in whether individuals forecast upcoming stressors, whether individuals show anticipatory stress responses prior to stressors, and whether having previously forecasted any stressors moderates stressor exposure on negative affect.

Method

Adults (n = 237; age 25–65) completed surveys five times daily for 14 days on current negative affect, stressor exposure, and stressor forecasts.

Results

Older age was associated with slightly greater likelihood of reported stressors but unrelated to forecasted stressors. Following forecasted stressors, individuals were four times more likely to report a stressor had occurred; age did not moderate this effect. Even prior to stressors, current negative affect was significantly higher when individuals forecasted stressors compared to when no stressors were forecast. No support was found for forecasts buffering effects of stressors on negative affect and age did not moderate this interaction. Instead, the effects were additive.

Discussion

In an age-heterogeneous sample, individuals showed early and persistent affective responses in advance of stressors. Anticipatory stress responses may be a mechanism for chronic stress.

Keywords: Aging, Anticipatory stress, Negative affect, Stressor forecasting

After four decades of daily stress studies, a consistent finding is that, on average, individuals report higher negative affect on days when they report a stressor compared to their negative affect on days when they reported no stressor (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981; Mroczek & Almeida, 2004; Neupert, Almeida, & Charles, 2007; Ong, Bergeman, Bisconti, & Wallace, 2006; Röcke, Li, & Smith, 2009; Suls, Green, & Hillis, 1998; van Eck, Nicolson, & Berkhof, 1998; Whitehead & Bergeman, 2012; Zautra, Affleck, Tennen, Reich, & Davis, 2005). Studies like these have treated everyday stressors as randomly occurring, unexpected events that perturb a previously evenly keeled emotional state. With these conceptualizations, researchers have effectively assumed that the emotional state is disturbed when the event occurs (e.g., emotional reactivity) and for some amount of time following the event until returning to a baseline level (e.g., emotional recovery) (see figure 9.2 in Sliwinski & Scott, 2014).

Not all stressors, however, are unpredictable surprises. Bills, work deadlines, and many other stressors may be highly anticipatable in daily life. Forecasting whether stressors will occur at a specified point in the future involves future-oriented thinking (Aspinwall, 2005). As individuals make forecasts about future stressors, they may rely on their first-hand knowledge of routine occurrences (i.e., traffic at rush hour) or impending events (i.e., work evaluation at 2 p.m.). In contrast, some daily experiences are stressful because they violate our expectations and disrupt our plans (i.e., unusual traffic delays because of an accident; need to leave work early to pick up sick child at school). Following the conceptual model and definitions in this special issue (Neupert, Neubauer, Scott, Hyun, & Sliwinski, 2018), we refer to these predictions as stressor forecasting. This term borrows from affect forecasting (Wilson & Gilbert, 2003, 2005) and risk taking and aversion (Kahneman & Lovallo, 2000). We propose that there are different levels of specificity for predicting future stressors. First, “temporal specificity,” which indicates that a person knows that something stressful will happen during a specific time period (e.g., the next few hours, the next day, the next month). Second, “type specificity” in which a person predicts the domain of stressor that might occur (e.g., travel related, work related, interpersonal; see Neupert and Bellingtier, 2018). Even more fine-grained is “event-specificity” in which a person predicts the specific stressor that occurs (e.g., mechanical breakdown, or arguing with spouse). Even within event-specificity, one could query about whether the specifics of the event that occurred matched those forecasted (e.g., a flat tire, arguing about finances). The current study examined stressor forecasting at the level of temporal specificity (i.e., will any stressful event happen in the next few hours).

Presently, little is known about whether individuals are accurate in forecasting whether or not daily stressors would occur. An exception is a longitudinal measurement burst study of 20–79-year olds (Neubauer, Smyth, & Sliwinski, 2018a). Individuals were more than four times more likely to report stressors had occurred when they previously forecasted stressors, compared to times when they previously forecasted no stressors. Stressor forecasts were not perfectly accurate, however, as indicated by the finding that following stressor forecasts, stressors were reported at only 51.4% of the next assessments.

There may be age differences in the stressor forecast accuracy. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST) offers contradictory predictions for affect forecasting (see Nielsen, Knutson, & Carstensen, 2008). Extending SST hypotheses for stressor forecasting, given accumulated life experience and valuing emotional stability, older adults may prioritize accurately predicting an emotionally disruptive stressor, resulting in better accuracy. Contradictorily, older age could be associated with lower stressor forecast accuracy. A preference for emotional equilibrium (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005) could result in overestimating the likelihood of a stressor to prepare for the worst case scenario (Paterson & Neufeld, 1987). Similarly, the positivity effect (Mather & Carstensen, 2005; Reed & Carstensen, 2012) could result in missing relevant negative cues about a forthcoming stressor and underestimating stressor likelihood. No studies to date have examined age differences in stressor forecast accuracy.

Fortunately, the negative events we expect to happen do not always come to pass. An implication of this is that there may be emotional responses to these threats, even before (or without) the stressor (Brosschot, 2017; Brosschot, Verkuil, & Thayer, 2017); Paterson and Neufeld (1987) referred to these responses to future aversive events as anticipatory stress; in this special issue, we refer to these as anticipatory stress responses. In laboratory investigations in which individuals were told that a shock was 100% or 50% likely to occur a few minutes later, participants showed similar anticipatory stress responses in heart rate, skin conductance, and relaxation-tension whether or not they actually received a shock (Monat, Averill, & Lazarus, 1972). Individuals showed lower tolerance for frustration (Spacapan & Cohen, 1983) and greater cortisol awakening response (CAR; Elder, Barclay, Wetherell, & Ellis, 2018) when told to expect a stressor compared to controls who were not told to expect a stressor. Individuals “preacted” in the absence of an event. These effects were specific to frustration tolerance and CAR: consistent differences were not found across stressor expectation conditions for mood, blood pressure, or physical symptoms (Spacapan & Cohen, 1983) or subjective or objective sleep (Elder et al., 2018).

Real-world stressors differ from laboratory stressors in many ways, including their personal relevance, potency, and duration (Brown & Harris, 1989). The effects of forecasted everyday stressors, like those deadlines and bills mentioned above, should also be potent. To the extent that individuals both respond to stressors when they occur and pre-emptively respond when they forecast future stressors, may together produce higher negative affect and result in longer periods of distress than for unpredicted stressors. Van Eck and colleagues’ (1998) ecological momentary assessment (EMA) study of male whitecollar workers found that stressor expectedness related to negative affect—for reported stressors that were retrospectively rated as more expected, negative affect was higher compared to stressors rated less expected. Smyth and colleagues’ (1998) EMA study asked participants to make prospective stressor forecasts to test whether individuals respond similarly to anticipated and actual stressors in daily life. At times when individuals reported that they expected stressors to occur in the next hour, negative affect and cortisol were higher and positive affect was lower—even controlling for whether the person had been dealing with problems in the last 5 min or had been exposed to stressors in the last 2 hr.

Study design limits conclusions regarding the effects of forecasted stressors on negative affect. Van Eck and colleagues (1998) relied on retrospectively-rated expectedness. This means that, after the fact, individuals may have rated more influential stressors as ones that they were unprepared for and did not expect. Smyth and colleagues (1998) assessed negative affect concurrently with stressor forecasts, thus it is not possible to determine whether individuals currently experience worse negative affect because they foresee stressful experiences or if they are more likely to label their upcoming events as stressors at times when they are already in a bad mood. In order to disentangle the effects on negative affect related to contemporaneous forecasts, prior forecasts, and stressor exposure, models with carefully chosen baseline comparisons are needed (Smyth et al., 2018). Neubauer and colleagues’ (2018a) study found that individuals had higher negative affect concurrent with observations in which they forecasted stressors in the next few hours—supporting what was suggested by van Eck et al. (1998) and Smyth et al. (1998)—and that there were lagged effects of prospective stressor forecasts on future negative affect. Specifically, when no stressors had occurred, negative affect was higher when individuals had previously forecasted stressors compared to when they had not. Negative affect was elevated in cases when stressors occurred; however, the increase in negative affect was similar regardless of whether the individual previously forecasted stressors or not. Based on laboratory and naturalistic research, we predict individuals will show anticipatory stress responses in the form of heightened current negative affect when they forecast stressors but stressors have not yet occurred. We used lagged effects models to test questions of the effects of unexpected stressors.

Individual differences in reactivity to stressor exposure are frequently found. Given evidence that stressor forecasts concurrently and prospectively relate to negative affect, does age or other factors distinguish differences in how much individuals respond to stressor forecasts? Age differences in preferences for more passive emotion-regulation strategies (Blanchard-Fields, 2007) as a way to “short circuit the stress process” (Folkman, Lazarus, Pimley, & Novacek, 1987, p. 182) could result in older age relating to a weaker response to stressors which were forecast but did not occur. For example, older age was associated with less of an increase in negative affect on days when individuals reported they avoided a potential argument, relative to a baseline of days in which individuals did not report avoiding an argument (Charles, Piazza, Luong, & Almeida, 2009). On days when an argument was reported, however, no age differences were found. It may be that when it is not possible to avoid upcoming stressors, anticipating it ahead of time does not confer a special advantage with older age. Further, it is possible that with older age, individuals may more vulnerable to the effects of prolonged negative affect (Charles, 2010), which—based on the lagged effect of stressor forecasts observed by Neubauer and colleagues (2018a)—is expected to be elevated in advance of actual stressors for forecasted stressors.

In the present study, we utilize data from an EMA study in which participants reported on current NA, whether a stressor had occurred since the last survey (i.e., a period of 2.5 hr on average), and whether they expected something stressful to occur in the next few hours. We tested the following questions: First, are stressors more likely to be reported following stressor forecasts? We predicted when a person forecasted any upcoming stressors in the next few hours it is more likely that stressors would be reported at the next survey. Second, do individuals show anticipatory stress responses in daily life? We predicted that current negative affect would be higher when individuals forecasted any upcoming stressors, compared to times when they did not forecast stressors. Third, when stressors occur, do individuals respond similarly in terms of negative affect when they previously forecasted any stressors, compared to when they did not forecasted stressors would occur? Importantly, in the analyses below, we carefully posed these questions in order to disaggregate anticipatory stress responses related to forecasted stressors from “reactivity” or response to reported stressors. For each of these questions, we tested age for age differences.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from the first burst of the Effects of Stress on Cognitive Aging, Physiology, and Emotion (ESCAPE; Scott et al., 2015) study. ESCAPE participants were recruited via systematic probability sampling of New York City Registered Voter Lists for the zip code 10475. Introductory letters were sent, followed by calls to establish eligibility (i.e., age 25–65, ambulatory, fluent in English, free of visual impairment, Bronx County resident) and enroll those who were interested. The sample included 237 adults who were aged 25–65 (mean age: 46.9 [SD: 10.7]). Women made up 66.2% of the sample; 62.5% identified as non-Hispanic Black, 6.3% as Hispanic Black, 17.7% as Hispanic White, 9.3% as non-Hispanic White, 4.2% as Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, or Other. The median income was $40,000–$59,999 (<$20,000: 21.1%; $20,000–$39,999: 23.2%; $40,000–$59,999: 20.3%; $60,000–$79,999: 10.6%; $80,000–$100,000: 6.8%; >$100,000: 9.7%, chose not to answer: 8.4%); the median education was some college (less than high school: 5.5%; high school or equivalent: 17.3%; some college: 32.5%; college degree: 27.4%; graduate or professional degree: 17.3%). Half (50.2%) were employed (retired: 12.7%; unemployed and looking for work: 27.0%; unemployed and not looking for work: 9.3%; N/A: 0.8%). Nearly half (50.6%) had children at home. The majority of the participants were married to first spouse (21.5%) or never married (34.6%).

Measures

Age and other demographics (sex, race–ethnicity, annual household income, education) were assessed in a baseline paper and pencil questionnaire.

Ecological momentary assessments

Participants completed separate ratings of current negative affective states in response to questions framed as “How unhappy to do you feel right now?” using a slider from not at all (0) to extremely (100). Negative affect was calculated as the average of ratings of tense/anxious, angry/hostile, depressed/blue, frustrated, and unhappy. Following the procedures described by Cranford and colleagues (2006), high reliability was found both to detect differences between individuals (RKF= .99) and changes within individuals from one occasion to another (RC = .82). Reported stressors were assessed by participants checking yes or no to “Did anything stressful occur since the last survey? A stressful event is any event, even a minor one, which negatively affects you.” During the training (described below), participants were instructed to report on the most significant stressor if more than one occurred. Forecasted stressors were assessed at the end of the survey with a yes or no response to the question “Do you think anything stressful or unpleasant will happen in the next few hours?”

Procedure

Participants who met eligibility criteria attended a lab visit to the research offices. During this visit, they completed demographic questionnaires and 1.5 hr of training on the study protocol and use of study smartphones. The day after the training, the participants completed 2 days of the EMA protocol then returned to the lab. The protocol involved the smartphones beeping five quasi-random times each day. The interval between beeped surveys was about 2.5 hr; beep times varied across days of the week but were programmed according to self-reported wake schedules. Those participants who completed 80% or more of the smartphone surveys were invited into the 14 day study. During the study period, the average participant completed 83.4% of surveys (SD: 21.1%, range: 8.5%–100%). Participants completing all aspects of this data collection received $160.

Analytic Approach

To address our first question—are stressors more likely to be reported following stressor forecasts?—we used a multilevel logistic model in SAS GEN MOD with repeated statement. In this model, lagged forecasted stressor from the prior survey was used to predict reported stressor at the current survey. Lagged forecasted stressor was necessarily missing for the first survey of each day (no prior survey that morning) and was thus not included in the analysis.

For our second question—do individuals experience anticipatory stress responses in the form of elevated NA when they forecast any upcoming stressors?—we used multilevel models (MLMs) predicting current negative affect from concurrently reported stressor forecasts. In order to isolate anticipatory stress responses (e.g., elevated negative affect when any stressors are forecasted but have not yet occurred), we analyzed observations in which no stressors were reported to have occurred in the past 2.5 hr (N = 8,627 observations).

For our third question, we also used MLMs and sought to distinguish the effects of previously forecasted stressors when stressors did and did not subsequently occur. In order to rule out possible persistent elevations in negative affect due to earlier stressors, we analyzed observations for which stressors were not reported at the prior survey when individuals made their stressor forecasts. This analysis, then, provides estimates of current negative affect in four scenarios: when no stressors were previously forecasted and no stressors were reported, when stressors were previously forecasted and no stressors were reported, when no stressors were previously forecasted and stressors were reported, and when stressors were previously forecast and stressors were reported.

For simplicity, Tables 1–3 present the results of our key questions of age differences. Two- and three-way interactions were included in order to test whether age moderated the effect of lagged forecasted stressor on likelihood of reporting a stressor (i.e., two-way interaction, Table 2), whether age moderated the effect of currently forecasted stressors on current negative affect (i.e., two-way interaction, Table 3), whether age moderated the effect of currently reported stressors on current negative affect (i.e., two-way interaction, Table 4) and whether age moderated the interaction between lagged forecasted stressor and currently reported stressor on current negative affect (i.e., three-way interaction, Table 4). Supplementary Tables S1–S3 display the full set of demographic variables included as covariates. In all models, age was centered at 45 years. Because reported and forecasted stressors have a meaningful zero (e.g., no event), these variables were uncentered. We also included variables representing individual differences in reported or forecasted stressors (i.e., proportion of surveys in which stressors were reported, proportion of surveys in which stressors were forecasted). In MLMs predicting negative affect from lagged stressor, the individual’s day-centered lagged negative affect (e.g., momentary negative affect subtracted from the person’s average negative affect for that particular day) was included to address dependency in the lagged data. Random effects were included for reported and forecasted stressors. All MLMs were estimated using three-level model including day level with the restricted maximum likelihood method, the between–within method for the denominator degrees of freedom option, and the unstructured variance–covariance matrix.

Table 1.

Cross-tabulation for Concurrently Reported and Lagged Forecasted Stressors

| Concurrently reported stressor | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lagged forecasted stressor | Yes | No | Total |

| Yes | 701 | 838 | 1,539 |

| 6.7% | 8.0% | 14.8% | |

| No | 1,151 | 7,738 | 8,889 |

| 11.0% | 74.2% | 85.2% | |

| Total | 1,852 | 8,576 | 10,428 |

| 17.8% | 82.2% | 100.0% | |

Note: Reported stressor was concurrently reported at the same survey; lagged forecasted stressor represents forecasted stressors reported at prior survey.

Table 3.

Multilevel Model Predicting Current Negative Affect From Concurrently Forecasted Stressors and Age When No Stressor Was Reported

| Variable | B coefficient | SE | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 18.67 | 1.55 | <.01 | |

| Currently forecasted stressor | 7.79 | 0.97 | <.01 | |

| Age | −0.14 | 0.10 | 0.17 | |

| Interaction between currently forecasted stressor and age | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.74 | |

| Proportion of reported stressor | 10.73 | 9.12 | 0.24 | |

| Proportion of forecasted stressor | 0.73 | 7.65 | 0.92 | |

| Prior (lagged) negative affect centered at day-mean negative affect | −0.09 | 0.01 | <.01 | |

| Random effects (variance components) | ||||

| Level 1 | Residual (within-person) | 88.33 | 1.68 | <.01 |

| Level 2 | Day | 48.50 | 2.42 | <.01 |

| Level 3 | Residual (between-person) | 243.66 | 23.35 | <.01 |

| Forecasted stressor | 63.55 | 15.00 | <.01 | |

| Covariance (residual, forecasted stressor) | -14.87 | 14.71 | 0.31 | |

Note: Age was included as a moderator in order to test for age differences. Age was centered at 45 years old and addressed as a continuous variable. Intercept and currently forecasted stressor were included as random effects.

Table 2.

Multilevel Logistic Models Predicting Reported Stressor

| Variable | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Lagged forecasted stressor | 3.00** | 2.47–3.65 |

| Age | 1.02** | 1.01–1.03 |

| Interaction between forecasted stressor and age | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 |

| Proportion of forecasted stressors | 8.03** | 4.33–14.91 |

Note: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Multilevel logistic model predicting likelihood of reporting a stressor at the current survey from lagged forecasted stressor from the prior survey, demographics (i.e., age, sex, race–ethnicity, annual household income, education, and work/marital status) and their interactions. For simplicity, only the key predictors are displayed here. Full results are displayed in Supplementary Table S1. The OR was adjusted for proportion of observations the individual endorsed anticipating a stressor in the next few hours. Age was centered at 45 years old and addressed as a continuous variable.

**p < .01.

Table 4.

Multilevel Model Predicting Current Negative Affect From Reported and Lagged Forecasted Stressors and Age When No Stressor Was Previously Reported

| Variable | B coefficient | SE | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 18.60 | 1.54 | <.01 | |

| Currently reported stressor | 15.81 | 0.99 | <.01 | |

| Lagged forecasted stressor | 4.78 | 0.89 | <.01 | |

| Interaction between currently reported and lagged forecasted stressors | −0.73 | 1.33 | 0.58 | |

| Age | −0.10 | 0.10 | 0.30 | |

| Interaction between currently reported stressor and age | −0.21 | 0.09 | 0.02 | |

| Interaction between lagged forecasted stressor and age | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.89 | |

| Interaction among currently reported stressor, lagged forecasted stressor, and age | −0.10 | 0.12 | 0.40 | |

| Proportion of reported stressor | 1.00 | 9.10 | 0.92 | |

| Proportion of forecasted stressor | 6.91 | 7.55 | 0.36 | |

| Prior (lagged) negative affect centered at day-mean negative affect | −0.24 | 0.01 | <.01 | |

| Random effects (variance components) | ||||

| Level 1 | Residual (within-person) | 102.68 | 2.02 | <.01 |

| Level 2 | Day | 44.38 | 2.58 | <.01 |

| Level 3 | Residual (between-person) | 242.54 | 23.41 | <.01 |

| Reported stressor | 138.08 | 18.94 | <.01 | |

| Lagged forecasted stressor | 33.35 | 9.77 | <.01 | |

| Covariance (residual, reported stressor) | −32.17 | 14.65 | 0.03 | |

| Covariance (residual, lagged forecasted stressor) | −15.18 | 12.05 | 0.21 | |

| Covariance (reported stressor, lagged forecasted stressor) | 14.16 | 11.63 | 0.22 | |

Note: NA = xxx. Age was included as a moderator in order to test for age differences. Age was centered at 45 years old and addressed as a continuous variable. Intercept, currently reported stressor, and lagged forecasted stressor were included as random effects.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays frequencies of concurrently reported and forecasted stressors. Participants forecasted any stressors in the next few hours on about 18% of the surveys; they reported that stressors had occurred in the last few hours on about 14% of surveys. In about 8% of surveys, participants reported that they had both experienced a stressor in the last few hours and forecasted anything stressful would occur in the next few hours. Two and a half hours after surveys in which they forecasted any stressors, individuals reported stressors had occurred at 701/1,539 or approximately 46% of the next surveys (i.e., a forecasted stressor hit); they reported that stressors had not occurred at 838/1,539 or about 54% of the next surveys (i.e., a forecasted stressor miss). In contrast, the “hit rate” was much higher following surveys in which individuals forecasted no stressors for the next few hours: individuals reported no stressors at 7,738/8,889 or 87% of the next surveys (i.e., a forecasted no stressor hit) and reported stressors had occurred only 1,151/8,889 or 13% of the next surveys (i.e., a forecasted no stressor miss). The correlation between age and proportion of observations individuals reported stressors was significant (r (235) = .14, p = .03). Age was not correlated with person-average negative affect (r (235) = −.07, p = .32) or proportion of observations individuals forecasted a stressor (r (235) = −.01, p = .83).

Are Stressors More Likely to be Reported Following Stressor Forecasts?

The results of this model are displayed in Table 2. Lagged forecasted stressor was a significant predictor of reporting a stressor at the next survey (OR = 3.94, SE = 1.91, CI = 1.53–10.18). That is within persons, following surveys when any stressors were forecasted, the individual was nearly four times more likely to report stressors occurred compared to observations when the participant did not forecast stressors. Older age was significantly associated with a slightly greater likelihood of reporting a stressor (OR = 1.01, SE = 0.01, CI = 1.00–1.03). The interaction between age and lagged forecasted stressors, however, was not significant (OR = 1.00, SE = 0.01, CI = 0.98–1.02). See Supplementary Table S1 for full details.

Do Individuals Show Elevated NA When They Forecast Any Stressors?

Our second research question asked whether, prior to a stressor’s occurrence, individuals show elevated current NA when they forecast stressors compared to times when they forecast no stressors. The results of this model are displayed in Table 3. Negative affect was higher when participants forecasted upcoming stressors relative to times when they did not forecast upcoming stressors (B = 7.79, SE = 0.97, p < .01). Age did not moderate the effect of currently forecasted stressors (B = −1.03, SE = 0.09, p = .74). See Supplementary Table S2 for full details on other demographics.

Do Prior Forecasts Moderate Stressor Effects on Negative Affect?

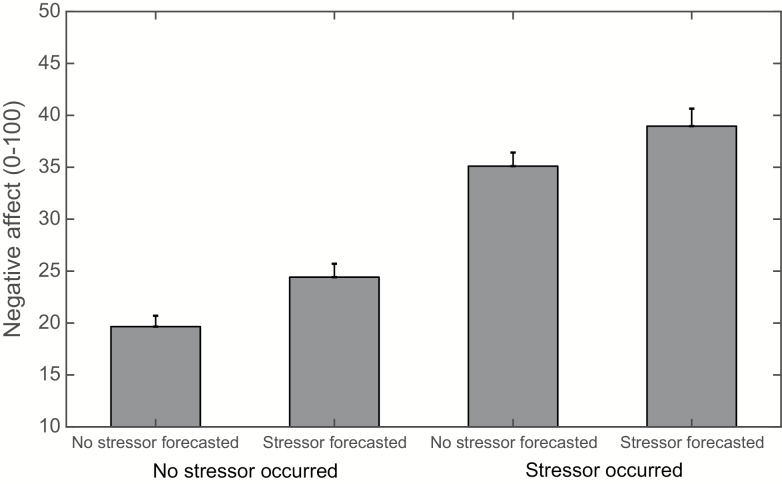

This third question was whether, when stressors are reported, do individuals show higher negative affect when they previously forecasted no stressors compared to when they had forecasted stressors at the prior survey; the results are displayed in Table 4. There were significant effects of currently reported stressor (B = 15.81, SE = 0.99, p < .01) and lagged forecasted stressor (B = 4.78, SE = 0.89, p < .01) on negative affect, indicating that both were associated with higher negative affect (Figure 1). There was a significant interaction between currently reported stressors and age on current negative affect (B = −0.21, SE = 0.09, p = .02). We used ESTIMATE statements in SAS PROC MIXED in order to understand the direction of this effect—there was a trend such that younger individuals tended to show greater negative affect following currently reported stressors. That is, we estimated for three ages (i.e., 35, 45, and 55 years) average negative affect values for assessments on which a stressor was reported (age 35: 38.58, age 45: 35.48, age 55: 32.38). This age effect was previously reported (Scott, Ram, Smyth, Almeida, & Sliwinski, 2017) in this data set. No support, however, was found for the moderating role of previously forecasting stressors on the impact of reported stressors on negative affect; the interaction between lagged forecasted stressor and reported stressor was not significant (B = −0.73, SE = 1.33, p = .58). Similarly, it appears that this pattern did not differ across age. We found no evidence of a three-way interaction between lagged forecasted stressor, reported stressor, and age predicting negative affect (B = −0.10, SE = 0.12, p = .40). See Supplementary Table S3 for full details on other demographics.

Figure 1.

Current negative affect estimated by multilevel model testing whether current negative affect was higher when participants previously forecasted upcoming stressors and currently reported stressors had occurred since the last survey. Tukey-Kramer procedures (conducted by SAS LSMEANS statement) showed all estimates are significantly different each other. Error bars indicate the SE of each estimate.

Discussion

We posed three main questions and examined age differences: are stressors more likely to be reported following stressor forecasts?, do individuals show anticipatory stress responses when they forecast stressors?, and do previous stressor forecasts moderate the effect of reported stressors on negative affect? Despite the common approach (including our own) of conceptualizing, measuring, and modeling everyday stressors as unexpected events which disrupt emotional functioning when they occur, this study provides evidence that everyday stressors are often forecasted, that individuals may “preact” to stressors prior to their actual occurrence, and that the threat of forecasted stressors appears to have lasting effects on negative affect even when events do not occur. We discuss these findings below in light of the literature on stress and socioemotional aging.

Forecasting the Future

Given the familiar, even scheduled, nature of many everyday stressors, we expected that stressor forecasts would prospectively predict reported stressors. Indeed, reported stressors were nearly four times more likely following forecasted stressors at prior survey. This finding is consistent with the only other study examining prospective forecasts predicting stressor reports (Neubauer et al., 2018a). As in that study, however, individuals were not perfectly “accurate” in their predictions. A few hours after forecasting stressors, stressors were reported about 46% of the time. The hit rate was much higher when individuals forecasted stressors would not occur—in 87% of the surveys following forecasts of no upcoming stressors they reported no stressors.

Why this difference in the accuracy of forecasting whether stressors will occur or not? One explanation is, of course, that given information that a stressor is pending, individuals may engage in anticipatory coping behaviors to prevent it (see Neupert & Bellingtier, 2018). In support of this, an EMA study that asked participants to select an explanation for why no stressor occurred when a stressor was not reported found that 20% of these times individuals reported that they avoided stressful situations and 10% of the time that they handled situations before they became stressful (see Neubauer, Smyth, & Sliwinski, 2018b). Interestingly, in that study the response that best fits with actual frequency of daily stressor reports—that stressors do not usually happen—was only endorsed 15% of these times. This was less than explanations of luck (19%) or another reason (36%) (Neubauer et al., 2018b). Recent stress theory (Brosschot, 2017; Brosschot et al., 2017) proposed a default stress response which is inhibited only when the individual perceives safety. We did not find evidence that individuals constantly expected stressors, but these overestimates in terms of stressor forecasts could be examples of “preparing for the worst” and inflating the probability that additional negative events will occur (Paterson & Neufeld, 1987).

We did not have specific hypotheses regarding age differences in stressor forecasting. Age did not moderate accuracy in forecasting whether future stressors would occur. It is possible that in the set of everyday stressors they forecasted and experienced, the 25–65-year olds in this study were similarly accurate. If there are systematic, age-related differences in stressor forecasting, however, it is possible that the age range in this study was not sufficiently wide to capture this.

Early and Persistent Emotional Responses

We found that when no stressors had yet occurred, current negative affect was higher when participants concurrently forecasted any stressors compared to when they did not forecast any stressors, consistent with Paterson and Neufeld’s (1987) definition. Examining the persistence of these responses to prospectively forecasted stressors, we found a significant lagged stressor forecast effect such that 2.5 hr after forecasting stressors negative affect was significantly higher than times when they had not previously forecasted stressors. The effect of prior stressor forecast was not as large as the increase in negative affect for concurrently reported stressors (Figure 1), but indicates that individuals show persistent effects of the threat from forecasted stressors, even if these do not occur. Over a longer forecasting period of an entire day, responses to the question “How stressful do you think today will be?” upon waking predicted cognitive performance throughout the day (Hyun, Smyth, & Sliwinski, 2018) even when accounting for the effect of stressor exposure. Together, these results concur with Koval and Kuppens’ proposition that “the anticipatory period may often last longer (e.g., hours or days) than the stressor itself” (2012, p. 258). Anticipatory stress responses, then, may be a pathway by which individuals experience persistent (negative affect), and over time, result in chronic stress which may result in risk for disease (Smyth, Zawadzki, & Gerin, 2013).

It is important to note that, consistent with Neubauer and colleagues (2018a), we did not find evidence for prior stressor forecasts buffering or exacerbating the effect of a stressor on negative affect several hours later. When a stressor occurred, negative affect was higher whether the individual had previously forecasted stressors or not. Thus, these results suggest that findings from the traditional approach to considering everyday stressors as unexpected disruptions would likely hold even if stressor forecasts were accounted for. However, these studies may have both (a) underestimated the duration of elevated negative affect related to stressors by estimating the “start” of negative affect elevations as when the stressor was reported to have occurred rather than when it was forecast and (b) potentially included anticipatory stress responses in the calculation of a non-stressor baseline (e.g., Scott et al., 2017; Wrzus, Luong, Wagner, & Riediger, 2015).

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations must be noted. First, we examined stressor forecasts in terms of temporal specificity (i.e., “Do you think anything stressful will happen in the next few hours?”). We cannot determine whether the precise stressor which an individual forecasted was the stressor that occurred (e.g., event-specificity). Similarly, we do not have data in this study on proactive coping behaviors that may have been engaged following these stressor forecasts. Neupert and Bellingtier (2018), however, collected daily diary ratings likelihood of next-day occurrence of stressors across different life domains (i.e., type specificity) as well as coping behaviors related to these forecasts.

Further, although we used lagged analyses in order to begin to address whether forecasted stressors are likely to be future reported stressors and whether negative affect is elevated hours after stressor forecasts, there is much more work to be done in order to understand anticipatory stress responses. For example, Paterson and Neufeld (1987) proposed that incubation period duration (i.e., time between forecast and occurrence) may increase stress levels. In order for stress research to advance, future designs must develop measures that clarify anticipatory processes and account for these influences in the effects of reported stressors. Last, although this special issue focused on delineating anticipatory stress concepts and testing the role of age differences, other constructs (e.g., neuroticism, defensive pessimism) may also help explain which individuals expect stressors and when forecasted stressors exert stronger effects on negative affect (e.g., intrusive thoughts; see Neubauer et al., 2018a). The present study contributes to the everyday stress literature by considering both the period prior to stressor exposure as well as the period afterward.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R03AG050798 to S. B. Scott, R01AG039409 to M. J. Sliwinski).

Conflicts of Interest

None reported.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aspinwall L. G. (2005). The psychology of future-oriented thinking: From achievement to proactive coping, adaptation, and aging. Motivation and Emotion, 29, 203–235. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9013-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields F. (2007). Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult developmental perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00469.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot J. F. (2017). Ever at the ready for events that never happen: European Journal of Psychotraumatology: Vol 8, No 1. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1309934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot J. F. Verkuil B. & Thayer J. F (2017). Exposed to events that never happen: Generalized unsafety, the default stress response, and prolonged autonomic activity. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 74, 287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. W., & Harris T. O (1989). Life events and illness. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L. L., & Mikels J. A (2005). At the intersection of emotion and cognition aging and the positivity effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00348.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charles S. T. (2010). Strength and vulnerability integration: A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 1068–1091. doi: 10.1037/a0021232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles S. T. Piazza J. R. Luong G. & Almeida D. M (2009). Now you see it, now you don’t: Age differences in affective reactivity to social tensions. Psychology and Aging, 24, 645–653. doi: 10.1037/a0016673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford J. A. Shrout P. E. Iida M. Rafaeli E. Yip T. & Bolger N (2006). A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: Can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably?Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 917–929. doi: 10.1177/0146167206287721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. J. Barclay N. L. Wetherell M. A. & Ellis J. G (2018). Anticipated next-day demand affects the magnitude of the cortisol awakening response, but not subjective or objective sleep. Journal of Sleep Research, 27, 47–55. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Lazarus R. S., Pimley S., & Novacek J (1987). Age differences in stress and coping processes. Psychology and Aging, 2, 171–184. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.2.2.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun J., Sliwinski M. J., & Smyth J. M (2018). Waking up on the wrong side of the bed: The effects of stress anticipation on working memory in daily life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 74, 38–46. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D., & Lovallo D (2000). Timid choices and bold forecasts: A cognitive perspective on risk taking. In D. Kahneman & A. Tversky (Eds.) Choices, values, and frames (pp. 393–413). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner A. D. Coyne J. C. Schaefer C. & Lazarus R. S (1981). Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 1–39. doi:10.1007/BF00844845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval P. & Kuppens P (2012). Changing emotion dynamics: Individual differences in the effect of anticipatory social stress on emotional inertia. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 12, 256–267. doi: 10.1037/a0024756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M. & Carstensen L. L (2005). Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monat A. Averill J. R. & Lazarus R. S (1972). Anticipatory stress and coping reactions under various conditions of uncertainty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 237–253. doi:10.1037/h0033297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek D. K. & Almeida D. M (2004). The effect of daily stress, personality, and age on daily negative affect. Journal of Personality, 72, 355–378. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer A. B., Smyth J. M., & Sliwinski M. J (2018a). Age differences in proactive coping with minor hassles in daily life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer A. B. Smyth J. M. & Sliwinski M. J (2018b). When you see it coming: Stressor anticipation modulates stress effects on negative affect. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 18, 342–354. doi: 10.1037/emo0000381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert S. D. Almeida D. M. & Charles S. T (2007). Age differences in reactivity to daily stressors: The role of personal control. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, P216–P225. doi:10.1093/geronb/62.4.P216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert S. D., & Bellingtier J. A (2018). Daily stressor forecasts and anticipatory coping: Age differences in dynamic, domain-specific processes. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74, 17–28. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupert S. D., Neubauer A. B., Scott S. B., Hyun J., & Sliwinski M. J (2018). Back to the future: Examining age differences in processes before stressor exposure. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 74, 1–6. doi:10.1093/geronb/gby074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen L. Knutson B. & Carstensen L. L (2008). Affect dynamics, affective forecasting, and aging. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 8, 318–330. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong A. D. Bergeman C. S. Bisconti T. L. & Wallace K. A (2006). Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 730–749. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson R. J. & Neufeld R. W (1987). Clear danger: Situational determinants of the appraisal of threat. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 404–416. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.3.404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. E. & Carstensen L. L (2012). The theory behind the age-related positivity effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 339. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röcke C. Li S. C. & Smith J (2009). Intraindividual variability in positive and negative affect over 45 days: Do older adults fluctuate less than young adults?Psychology and Aging, 24, 863–878. doi: 10.1037/a0016276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S. B., Graham-Engeland, J. E., Engeland, C. G., Smyth, J. M., Almeida, D. M., Katz, M. J., Lipton, R. B., Mogle, J. A., Munoz, E., Ram, N., & Sliwinski, M. J. (2015). The Effects of Stress on Cognitive Aging, Physiology, and Emotion (ESCAPE) Project. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 15, 146–160. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0497-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S. B. Ram N. Smyth J. M. Almeida D. M. & Sliwinski M. J (2017). Age differences in negative emotional responses to daily stressors depend on time since event. Developmental Psychology, 53, 177–190. doi: 10.1037/dev0000257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinski M. J., & Scott S. B (2014). Boundary conditions for emotional well-being in aging: The importance of daily stress. In P. Verhaeghen & C. Hertzog (Eds.), Oxford handbook of emotion, social cognition, and everyday problem solving during adulthood (pp. 128–141). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J. Ockenfels M. C. Porter L. Kirschbaum C. Hellhammer D. H. & Stone A. A (1998). Stressors and mood measured on a momentary basis are associated with salivary cortisol secretion. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 23, 353–370. doi:10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00008-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J. M. Sliwinski M. J. Zawadzki M. J. Scott S. B. Conroy D. E. Lanza S. T., … Almeida D. M (2018). Everyday stress response targets in the science of behavior change. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 101, 20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J. M., Zawadzki M., & Gerin W (2013). Stress and disease: A structural and functional analysis. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7, 217–227. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spacapan S. & Cohen S (1983). Effects and aftereffects of stressor expectations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 1243–1254. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.6.1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suls J., Green P., & Hillis S (1998). Emotional reactivity to everyday problems, affective inertia, and neuroticism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 127–136. doi: 10.1177/0146167298242002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Eck M. Nicolson N. A. & Berkhof J (1998). Effects of stressful daily events on mood states: Relationship to global perceived stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1572–1585. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead B. R. & Bergeman C. S (2012). Coping with daily stress: Differential role of spiritual experience on daily positive and negative affect. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 456–459. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. D., & Gilbert D. T (2003). Affective forecasting. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 345–411. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(03)01006-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T. D., & Gilbert D. T (2005). Affective forecasting: Knowing what to want. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 131–134. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00355.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wrzus C. Luong G. Wagner G. G. & Riediger M (2015). Can’t get it out of my head: Age differences in affective responsiveness vary with preoccupation and elapsed time after daily hassles. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 15, 257–269. doi: 10.1037/emo0000019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra A. J. Affleck G. G. Tennen H. Reich J. W. & Davis M. C (2005). Dynamic approaches to emotions and stress in everyday life: Bolger and Zuckerman reloaded with positive as well as negative affects. Journal of Personality, 73, 1511–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00357.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.