Abstract

To characterize mechanisms involved in neurokinin type 1 receptor (NK1R)-mediated emesis, we investigated the brainstem emetic signaling pathways following treating least shrews with the selective NK1R agonist GR73632. In addition to episodes of vomiting over a 30-min observation period, a significant increase in substance P-immunoreactivity in the emetic brainstem dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNX) occurred at 15 min post an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection GR73632 (5 mg/kg). In addition, time-dependent upregulation of phosphorylation of several emesis-associated protein kinases occurred in the brainstem. In fact, Western blots demonstrated significant phosphorylations of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase IIα (CaMKIIα), extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase1/2 (ERK1/2), protein kinase B (Akt) as well as α and βII isoforms of protein kinase C (PKCα/βII). Moreover, enhanced phospho-ERK1/2 immunoreactivity was also observed in both brainstem slices containing the dorsal vagal complex emetic nuclei as well as in jejunal sections from the shrew small intestine. Furthermore, our behavioral findings demonstrated that the following agents suppressed vomiting evoked by GR73632 in a dose-dependent manner: i) the NK1R antagonist netupitant (i.p.); ii) the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) antagonist nifedipine (subcutaneous, s.c.); iii) the inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) antagonist 2-APB (i.p.); iv) store-operated Ca2+ entry inhibitors YM-58483 and MRS-1845, (i.p.); v) the ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor U0126 (i.p.); vi) the PKC inhibitor GF109203X (i.p.); and vii) the inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathway LY294002 (i.p.). Moreover, NK1R, LTCC, and IP3R are required for GR73632-evoked CaMKIIα, ERK1/2, Akt and PKCα/βII phosphorylation. In addition, evoked ERK1/2 phosphorylation was sensitive to inhibitors of PKC and PI3K. These findings indicate that the LTCC/IP3R-dependent PI3K/PKCα/βII-ERK1/2 signaling pathways are involved in NK1R-mediated vomiting.

Keywords: GR73632, NK1 receptor, emesis, brainstem, gut, ERK1/2

1. Introduction

Serotonin (5-HT) type 3 receptor (5-HT3R) and substance P (SP) neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R) are major emetic receptors involved in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) (Darmani and Ray, 2009; Jordan et al., 2016). In fact both basic and clinical research have implicated 5-HT and SP as major neurotransmitters in CINV. They act on the brainstem dorsal vagal complex (DVC) emetic nuclei including the area postrema (AP), nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNV), as well as peripheral emetic loci such as neurons of the enteric nerves system (ENS) which are embedded in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and vagal afferents which carry input from the GIT to the brainstem DVC (Babic and Browning, 2013; Darmani and Ray, 2009; Ray et al., 2009a). Antiemetic regimens against high-dose cisplatin-type CINV include a 5-HT3R antagonist (e.g. palonosetron), an NK1R antagonist (e.g. netupitant), and the glucocorticoid dexamethasone (Jordan et al., 2016). Originally, release of 5-HT from enterochromaffin (EC) cells in the GIT during the acute phase and of SP in the brainstem DVC during the delayed phase were considered as major events in CINV (Andrews and Rudd, 2004; Hesketh et al., 2003). However, more recent basic and clinical research demonstrate these emetic neurotransmitters are released concomitantly both in the brainstem and the GIT during both phases of CINV (Darmani et al., 2008; Higa et al., 2006; Ray et al., 2009b). Indeed, outcomes from more recent clinical trials (Hesketh et al., 2016; Jordan et al., 2016) utilizing such antagonists prophylactically support the latter revised neurotransmitter basis of CINV.

Revealing post-receptor mechanisms underlying 5-HT3R/NK1R-mediated emesis is of significance for understanding CINV intracellular mechanisms as well as for developing new antiemetics. Recently our group demonstrated that Ca2+ mobilization via extracellular Ca2+ influx through 5-HT3Rs/L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCC), and intracellular Ca2+ release via ryanodine receptor (RyR) present on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, initiate Ca2+-dependent sequential activation of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase IIα (CaMKIIα) and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase1/2 (ERK1/2), which contribute to 5-HT3R-mediated, 2-methyl-serotonin (2-Me-5-HT)-evoked vomiting in the least shrew emesis model (Zhong et al., 2014b). Published literature indicate that Ca2+ mobilization following NK1R stimulation is also an important aspect of its downstream signaling. Indeed: i) Ca2+ response induced by SP is dependent on NK1R activation (Heding et al., 2002), ii) the selective NK1R agonist GR73632 causes an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration in spinal astrocytes in a dose-dependent manner (Miyano et al., 2010), iii) NK1R-evoked Ca2+ mobilization involves both extracellular Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ release from the ER intracellular calcium stores via inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor and/or RyR in SP-evoked muscle contraction (Lin et al., 2005) and spinal astrocytes (Miyano et al., 2010). In addition, we have found that LTCC blockers amlodipine and nifedipine suppress vomiting evoked by GR73632 in a potent and dose-dependent manner in least shrews (Darmani et al., 2014; Zhong et al.,2014a), suggesting extracellular Ca2+ influx through LTCC is involved NK1R-mediated emesis.

Our previous findings indicate that the Ca2+-CaMKII-ERK1/2 cascade in the brainstem and gut has a common role in the regulation of emetic responses elicited by intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of diverse emetogens (Zhong et al., 2016, 2014b). Furthermore, phosphorylation of ERK1/2 has been shown to play an important role in diverse NK1R-mediated cellular responses (Amadoro et al., 2007; Lallemend et al., 2003; Nakamura et al., 2014; Ramnath et al., 2007). However, NK1R belongs to the large family of GPCRs and signals through several different pathways associated with distinct G proteins (Garcia-Recio and Gascón, 2015). To delineate the central signal transduction pathway through which GR73632-NK1R interaction induces emesis in the least shrew, in the present study we examined the participation of Ca2+ channels, CaMKIIα, ERK1/2, protein kinase C (PKC), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (Akt) pathway. We also aimed to clarify the functional consequences of cross-talk between these effectors of NK1R stimulation following GR73632 administration.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

A colony of adult least shrews from the Western University of Health Sciences Animal Facilities were housed in groups of 5–10 on a 14:10 light: dark cycle, and were fed and watered ad libitum. The experimental shrews were 45–60 days old and weighed 4–6 g. Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Western University of Health Sciences. All efforts were made to minimize animals suffering and to reduce the number of animals used in the experiments.

2.2. Chemicals

The following drugs were used in the present study: the NK1R agonist GR73632 (Sakurada et al., 1999), PI3K-Akt pathway inhibitor LY294002 (Xiao et al., 2018), PKC inhibitors chelerythrine and GF109203X (Cho et al., 2001) (the latter more selectively targets PKCα/β (Asehnoune et al., 2005)), and store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) inhibitors YM-58483 and MRS-1845 were purchased from Tocris, Minneapolis, MN. CaMKII inhibitor KN93, ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor U0126 were obtained from Calbiochem, San Diego, CA. The L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine was from Sigma/RBI (St. Louis, MO). The ryanodine receptor antagonist dantrolene, the inositol-1, 4, 5-triphosphate receptor (IP3R) antagonist 2-APB were purchased from Santa Cruz (Dallas,Texas). The 5-HT3 receptor antagonist palonosetron and NK1 receptor antagonist netupitant were kindly provided by Helsinn Health Care (Lugano, Switzerland). GR73632 and palonosetron were dissolved in water. Nifedipine, dantrolene, 2-APB, YM-58483, MRS-1845, U0126, LY294002, chelerythrine and GF109203X were dissolved in 25% DMSO in water. Netupitant was dissolved in a 1:1:18 solution of emulphor™, ethanol and saline. All drugs were administered at a volume of 0.1 ml/10 g of body weight.

2.3. Behavioral emesis studies

On the day of the experiment shrews were brought from the animal facility, separated into individual cages and allowed to adapt for at least two hours (h). Daily food was withheld 2 h prior to the start of the experiment but shrews were given 4 mealworms each prior to emetogen injection, to aid in identifying wet vomits as described previously (Darmani, 1998).

We have previously demonstrated that a 5 mg/kg i.p. injection of the brain penetrating selective NK1 receptor agonist GR73632 produces a robust frequency of vomits in all tested animals (Darmani et al., 2011, 2008). To evaluate drug interaction studies, different groups of shrews were pre-treated with an injection of either corresponding vehicle (i.p. or subcutaneous (s.c.)), or varying doses of the: i) NK1R antagonist netupitant (0.5, 1, 5 and 10 mg/kg, i.p., n = 6 per group); ii) RyR antagonist dantrolene (0.5, 1, 5, 10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p., n = 6–8 per group); iii) IP3 receptor antagonist 2-APB (0.5, 1, 5, 10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p., n = 6–10 per group); iv) CaMKII inhibitor KN93 (10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p., n = 6–8 per group); v) ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor U0126 (5 and 10 mg/kg, i.p., n = 6 per group); vi) PI3K-Akt pathway inhibitor LY294002 (5, 10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p., n = 6); vii) PKC inhibitor chelerythrine (5, 10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p., n = 6–9); viii) PKC inhibitor GF109203X (5, 10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p., n = 6–9); and store-operated Ca2+ entry inhibitors YM-58483 or MRS-1845 (0, 1, 5 and 10 mg/kg, s.c., n = 6). Thirty minutes later, each treated shrew received a 5 mg/kg emetic dose of GR73632 (i.p.). The number of animals vomiting within groups and the frequency of vomits for the next 30 min were recorded. Each shrew was used once and then euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.) following the termination of each experiment.

2.4. Substance P immunohistochemistry

Different groups of adult least shrews were injected with a 5 mg/kg dose of GR73632 and anesthetized with isoflurane at time-points 15 min and 30 min and were then subjected to rapid perfusion. Likewise, some shrews were injected with a 1 mg/kg (i.p.) dose of GR73632 and 15 min later underwent perfusion. For antagonist studies, different groups of shrews were given netupitant (10 mg/kg, i.p.), nifedipine (5 mg/kg. s.c.) or 2-APB (20 mg/kg., i.p.) 30 min prior to an injection of GR73632 (5 mg/kg) followed by a 15 min exposure time. In the case of 2-APB, shrews were sacrificed at 30 min post GR73632 administration. After a 10-min perfusion, brains were removed and cryoprotected in 15% and then 30% sucrose at 4˚C till brains settled down to bottom, and sectioned on a freezing microtome at 20 μm. Sections were observed with a light microscope and those containing the whole DVC subjected to immunostaining. Slides were blocked in 0.1 M PBS containing 10% donkey serum and 0.3% Triton X-100, and then incubated overnight at 4°C with rat anti-subst ance P (1:1000, MAB356, Millipore) in 0.1 M PBS containing 5% donkey serum and 0.3% Triton X-100. Sections were washed 3 times (10 min each) in PBS and incubated in CY™3-conjugated donkey anti-rat secondary antibody (1:200, Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS 4 times, sections were mounted with anti-fade mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and examined under confocal microscope (Nikon). Images for the whole DVC and for the individual areas (AP/NTS/DMNX) were acquired under a confocal microscope (Nikon) with Metamorph software using 20× objective. We have already descr ibed the circumventricular organ AP and its different cytoarchitectonic detail such as cell size and packing, which differentiates DMNX from NTS within the DVC, as part of a stereotaxic atlas of the least shrew brainstem (Ray et al., 2009a). This criterion has been well recognized (Chebolu et al., 2010; Darmani et al., 2008; Ray et al., 2009a; Ray et al., 2009c; Zhong et al., 2016).The average SP intensity was determined in a 267 × 96 μm2 area in the DMNX. In order to correct for slice-to-slice variation in staining intensity, image intensities of the DMNX were subtracted from the area known as the hypoglossal nucleus (XII) bellow the DMNX that was negative of SP staining of the same slice. The values from 3 animals (3 slices per animal) were used for quantitative analysis.

2.5. Western blot for phosphorylation analyses

To determine the time-dependent profile of CaMKIIα, ERK1/2, Akt, and PKC phosphorylation, different groups of animals (n = 3 per group) were sacrificed at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min following GR73632 administration (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Shrew brainstems were then removed at specific intervals after GR73632 treatment and homogenized in lysis buffer. Protein extracts from brainstem lysates were subjected to Western blot. The following primary antibodies were used for Western blot: phospho-CaMKIIα (Thr286) (1:1000, ab32678, Abcam), CaMKIIα (1:1000, ab22609, Abcam), phospho-ERK1/2 (1:1000, #9101, Cell Signaling), ERK1/2 (1:3000, #9107, Cell Signaling), phospho-Akt (Ser473) (1:2000, #4060, Cell Signaling), Akt (1:2000, #2920, Cell Signaling), phospho-PKCδ (1:1000, #9374, Cell Signaling), phospho-PKCα/βII (Thr638/641) (1:1000, #9375, Cell Signaling) and GAPDH (1:10000, MAB374, Millipore). The following secondary antibodies were used for western blot: goat anti-rabbit IRDye 680RD and goat anti-mouse IRDye 800CW (1:10000, LI-COR). Bound antibodies were visualized correspondingly using Odyssey imaging system. The ratios of phospho-CaMKIIα (~ 50 kD) to CaMKIIα, phospho-ERK1/2 (42/44 kD) to ERK1/2, phospho-Akt to Akt, and phospho-PKCα/βII to GAPDH were calculated. All values were divided by the average value at time point 0 for normalization and presented as fold change of control. To identify the relationship between these kinases, different groups of least shrews (n = 3 per treatment group) were pretreated with specific inhibitors or corresponding vehicles, 30 min before GR73632 injection (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Brainstems were collected at 15 min after GR73632 treatment and subjected to Western blots.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The vomit frequency data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunn’s post hoc test and expressed as the mean ± SEM. The percentage of animals vomiting across groups at different doses was compared using the chi square test. Statistical significance for differences between two groups was tested by unpaired t-test. When more than two groups were compared, a one-way ANOVA was used followed by Dunn’s post hoc test to determine statistical significance between experimental groups and control. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

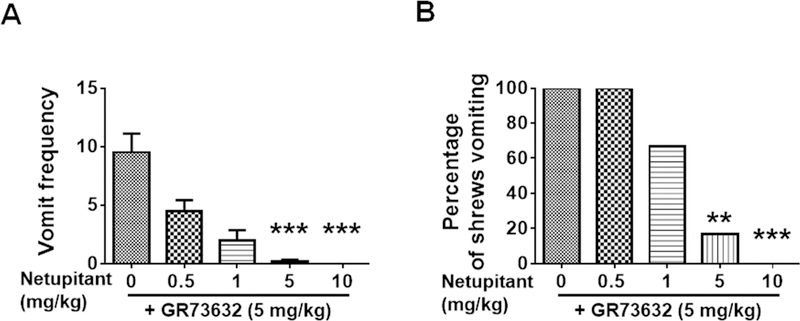

3.1. GR73632-evoked emesis is blocked by the selective NK1R antagonist netupitant

Netupitant (0.5, 1, 5, and 10 mg/kg, i.p.) caused a dose-dependent decrease in the frequency of vomits induced by the NK1R selective agonist GR73632 [(KW (4, = 23.13, p = 0.0001)] with significant reduction occurring at its 5 (p = 0.0009) and complete blockade at its 10 mg/kg dose (p = 0.0003) (Fig. 1A). The chi square test indicates that the percentage of shrews vomiting in response to GR73632 was also reduced by netupitant in a dose-dependent manner [(χ2 (4, 25) = 21.18, p = 0.0003)], with a significant reduction noted at its 5 (p = 0.0034) and complete protection occurring at its 10 mg/kg dose (p = 0.0005) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Antiemetic effects of the neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R) selective antagonist netupitant against GR73632-induced emesis in the least shrew.

Different groups of shrews received either vehicle (0 mg/kg, i.p.), or varying doses of netupitant (0.5, 1, 5 or 10 mg/kg, i.p.), 30 min prior to an emetic dose of GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Emetic parameters were recorded for 30 min post emetic injection. A. The frequency (mean ± SEM) of emesis. n = 6. *** p < 0.001 vs netupitant 0 + GR73632, Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one-way ANOVA and followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. B. The percentage of shrews vomiting. ** p < 0.01, chi square test.

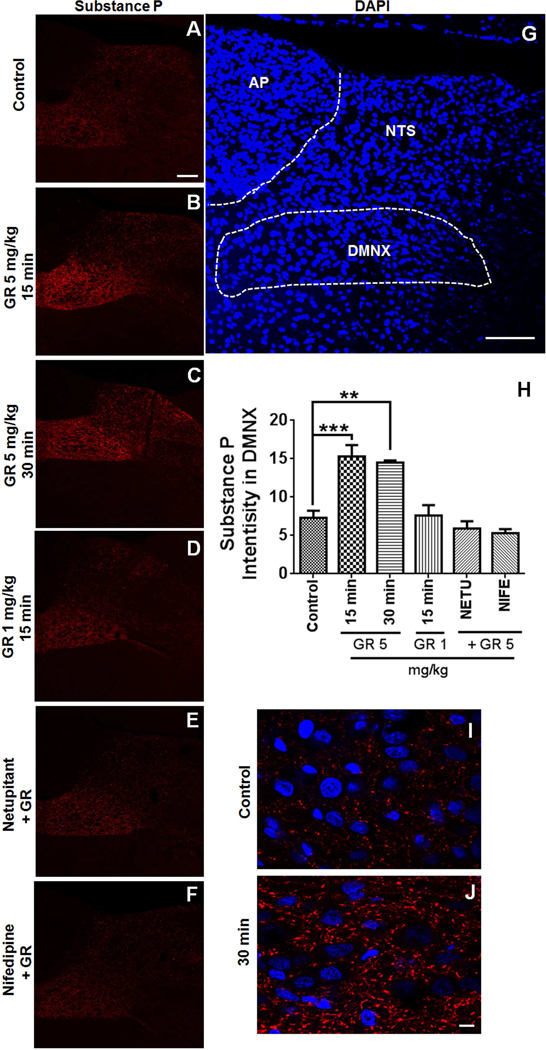

3.2. NK1R and LTCC are required for GR73632 to evoke SP release in the DVC

Stimulation of NK1R by either SP or GR73632 can trigger a time and dose-dependent increase in SP release in cultured adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons (Tang et al., 2007). In the current study, we investigated whether in vivo NK1R activation following systemic administration of GR73632 can affect SP release in the shrew brainstem. SP immunolabeling following GR73632 administration are shown in Fig. 2. Among the brainstem DVC emetic nuclei, there was a mild basal immunoreactivity of SP in DMNX and weak in NTS but not in AP of the vehicle-injected control group (Fig. 2A). Intraperitoneal administration of a 5 mg/kg dose of GR73632 significantly enhanced the SP level in the DMNX at 15 (p = 0.0005) and 30 min (p = 0.0013) post-injection (Fig. 2B, C, H), featured as punctate structures around cell bodies (Fig. 2I, 2J). On the other hand, the basal SP level remained unchanged 15 min post-injection following administration of a lower nonemetic dose (1 mg/kg) of GR73632 (p = 0.9997) (Fig. 2D, H). A 5 mg/kg dose of nifedipine (s.c.) has previously been shown to completely prevent vomiting evoked by GR73632 (5 mg/kg) (Darmani et al., 2014). SP immunohistochemistry experiments were also performed on non-vomiting shrews pretreated with either netupitant (10 mg/kg, i.p.) or nifedipine (5 mg/kg, s.c.) 30 min prior to GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) administration. In these animals, SP immunoreactivity in DMNX 15 min post GR73632 administration appeared to be similar to those of controls (p = 0.7878 between NETU + GR and Control; p = 0.4954 between NIFE + GR and Control) (Fig. 2E, F, H).

Fig. 2. Immunohistochemical analysis of GR73632-evoked substance P (SP) release in the least shrew brainstem.

Coronal brainstem sections (20 μm) were prepared from different groups of Shrews (n = 3 per group), including vehicle-treated control (A); 15 or 30 min post a 5 mg/kg (i.p.) injection of GR73632 (B and C); 15 min post a 1 mg/kg (i.p.) GR73632 injection (D); 15 min post GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) with 30-min pretreatment with either netupitant (10 mg/kg, i.p.) (E) or nifedipine (10 mg/kg, s.c.) (F). Sections were immunolabeled with rat SP antibody overnight followed by CY™3-conjugated donkey anti-rat secondary antibody incubation. A-F. Representative 20x images of brainstem slice showing SP immunoreactivity among the brainstem emetic nuclei, area postrema (AP), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNX). Scale bar, 100 μm. G. The boundary of DMNX is shown on representative section with nuclei stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 100 μm. H. Quantitative analysis of substance P immunostaining. In order to correct for section-to-section variation in staining intensity, substance P intensities determined in a 267 × 96 μm2 area in the DMNX were subtracted from the same size area bellow DMNX (known as the hypoglossal nucleus) that was negative of SP staining of the same slice. 3 images from each shrew were chosen for analysis. The average SP intensity was calculated and used as a value for an individual animal. Shown are means ± SEM of n = 3. ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 vs Control, One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. I-J. High magnification images show GR73632 enhancement of SP-immunoreactive puncta structures in the DMNX at 30 min post treatment. Bar, 10 μm.

3.3. Activation of ERK1/2 following NK1R stimulation in brainstem occurs through an LTCC-dependent pathway

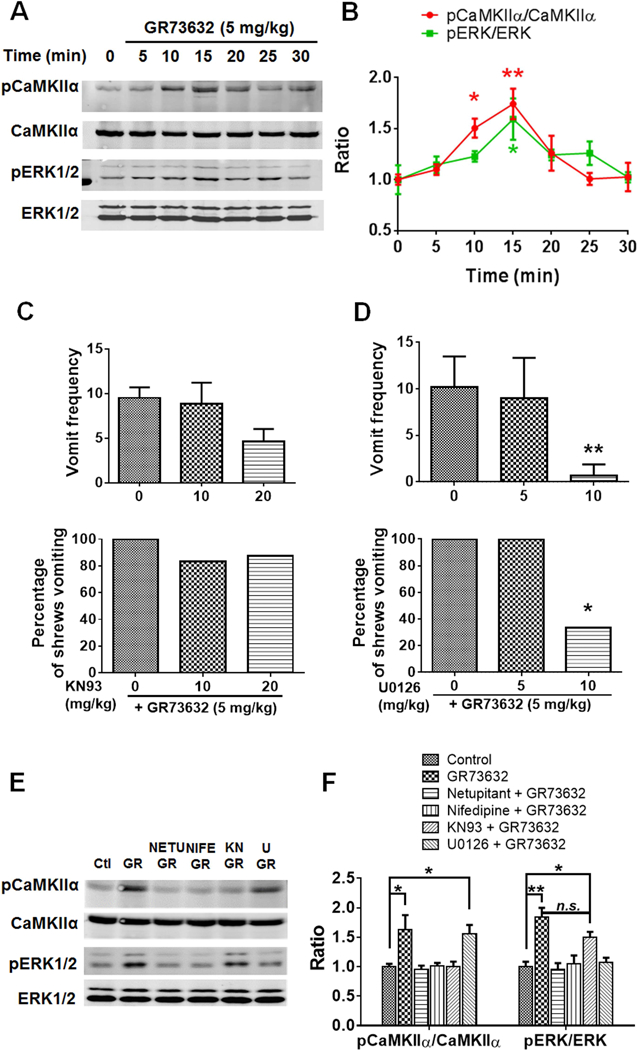

We recently reported that CaMKII mediates ERK1/2 activation in response to 5-HT3R-mediated emesis (Zhong et al., 2014b). In the current study, least shrews were treated (i.p.) for various periods (5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 min) with a 5 mg/kg dose of GR73632. Using the anti-phospho-CaMKIIα Thr286 and anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibodies, phosphorylation states of CaMKIIα and ERK1/2 were assessed by Western blot. Phosphorylation of CaMKIIα was triggered at 10 min (p = 0.0311) and reached a maximal value at 15 min (p = 0.0019) and then declined to unstimulated level (0 min) at 30 min (p = 0.9997) post-GR73632 administration (Fig. 3A, B). Peak phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) also occurred at 15 min post-GR73632 exposure (p = 0.0109) (Fig. 3A, B). Likewise, increased pERK1/2 immunoreactivity occurred in both shrew brainstem slices containing the dorsal vagal complex emetic nuclei (area postrema (AP), nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNX)), as well as in the jejunal sections of the shrew small intestine (See supplemental figures 1–4).

Fig. 3. Involvement of L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) in NK1R-dependent CaMKIIα and ERK1/2 activation.

A. Representative Western blots for time-course of CaMKIIα and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the least shrew brainstems collected at indicated time points after GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) administration (n = 3 per group). Phospho-CaMKIIα T286 (pCaMKIIα), CaMKIIα, phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) and ERK1/2 were detected by Western blot. B. Quantitative analysis of Western blots as shown in A. The ratios of pCaMKIIα to CaMKIIα and pERK1/2 to ERK1/2 (pERK/ERK) were compared. All ratios were normalized to vehicle-treated control (0 min) values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 vs. 0 min, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n = 3. C-D. Effects of either CaMKII inhibitor KN93 (C) or ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor U0126 (D) on GR73632-produced emesis. Different groups of shrews received i.p. vehicle (0 mg/kg), varying doses of KN93 (10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p. n = 6–8) or U0126 (5 and 10 mg/kg, i.p., n = 6), 30 min prior to GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Emetic parameters were recorded for 30 min post emetic injection. Upper panel shows frequency data presented as mean (± SEM). ** p < 0.01 vs. U0126 0 + GR73632, Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one-way ANOVA and followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Below panel shows the percentage of shrews vomiting. * p < 0.05 vs. U0126 0 + GR73632, chi square test. E-F. Effect of selective NK1R (netupitant) or LTCC (Nifedipine) antagonists on CaMKIIα and ERK1/2 phosphorylation evoked by GR73632 and the relationship between CaMKIIα and ERK1/2. E. Representative Western blots of CaMKIIα and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in brainstems obtained from vehicle-treated control (Ctl) or when least shrews were treated with GR73632 (5 mg/kg., i.p.) for 15 min in the absence (GR) or presence of an i.p. 10 mg/kg dose of netupitant (NETU+GR), an s.c. 10 mg/kg dose of nifedipine (NIFE+GR), i.p. 20 mg/kg KN93 (KN+GR), or an i.p. 10 mg/kg dose of U0126 (U+GR). All inhibitors were delivered 30 min prior to GR73632. Phospho-CaMKIIα T286 (pCaMKIIα), CaMKIIα, phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) and ERK1/2 were detected by Western blot. F. Quantitative analysis of Western blots of data shown in F. The ratios of pCaMKIIα to CaMKIIα and pERK1/2 to ERK1/2 (pERK/ERK) were compared. All ratios were normalized to control values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 vs. Control, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n.s., not significantly different, unpaired t-test. n = 3.

Pretreatment with the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 (10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 min prior to GR73632 injection tended to attenuate (51.3 % reduction) the mean frequency of vomiting but the reduction failed to achieve significance [(KW (2, 19) = 4.886, p =0.0830] (Fig. 3C). Moreover, the percentage of shrews vomiting [(χ2 (2, 19) = 1.329, p =0.5145)] in response to GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) was also not affected (Fig. 3C). However, the ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor U0126 (5 and 10 mg/kg, i.p) attenuated both the frequency of GR73632-induced emesis [(KW (2, 15) = 11.76, p = 0.0003] with a significant suppression at its 10 mg/kg dose (p = 0.0016) (Fig. 3D); as well as the percentage of shrews vomiting [(χ2 (2, 15) = 10.29, p = 0.0058)] with a significant reduction at its 10 mg/kg (p = 0.0143) (Fig. 3D). Therefore, while both CaMKII and ERK1/2 activation were observed during GR73632-induced emesis, only ERK1/2 inhibition exerted suppressive effect on the evoked emesis.

In order to further study the role of NK1R and LTCC activity on CaMKIIα and ERK1/2 activation and the CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2, different groups of shrews were pretreated either with the NK1R antagonist netupitant (10 mg/kg., i.p.), the LTCC antagonist nifedipine (5 mg/kg., s.c.), the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 (20 mg/kg, i.p.), or the ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor U0126 (10 mg/kg., i.p.) for 30 min prior to GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) injection. Brainstems were isolated 15 min post GR73632 administration. Western blots were performed to determine the phosphorylation states of brainstem CaMKIIα and ERK1/2. Figures 3E and 3F demonstrate that GR73632-evoked CaMKIIα phosphorylation (p = 0.0181 vs. control), was prevented when shrews were pretreated with either netupitant (p = 0.9985 vs. control), nifedipine (p = 0.9999), or KN93 (p = 0.9985), but not with U0126 (p = 0.0345). Regarding GR73632-induced ERK1/2 activation (p = 0.0011 vs. control), prior treatment with netupitant (p = 0.9969), nifedipine (p = 0.9964), and U0126 (p = 0.9895) completely prevented ERK1/2 phosphorylation. On the other hand, KN93 pretreatment tended but failed to significantly attenuate GR73632-evoked ERK1/2 phosphorylation (p = 0.0281 between KN93 + GR73632 and Control; p = 0.1319 between KN93 + GR73632 and U0126 + GR73632). Thus, these results indicate that while both ERK1/2 and CaMKII phosphorylation can be reversed by either the NK1R-or LTCC antagonist, inhibition of ERK1/2 has no effect on CaMKII phosphorylation. Likewise, CaMKII inhibition had no significant effect on ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

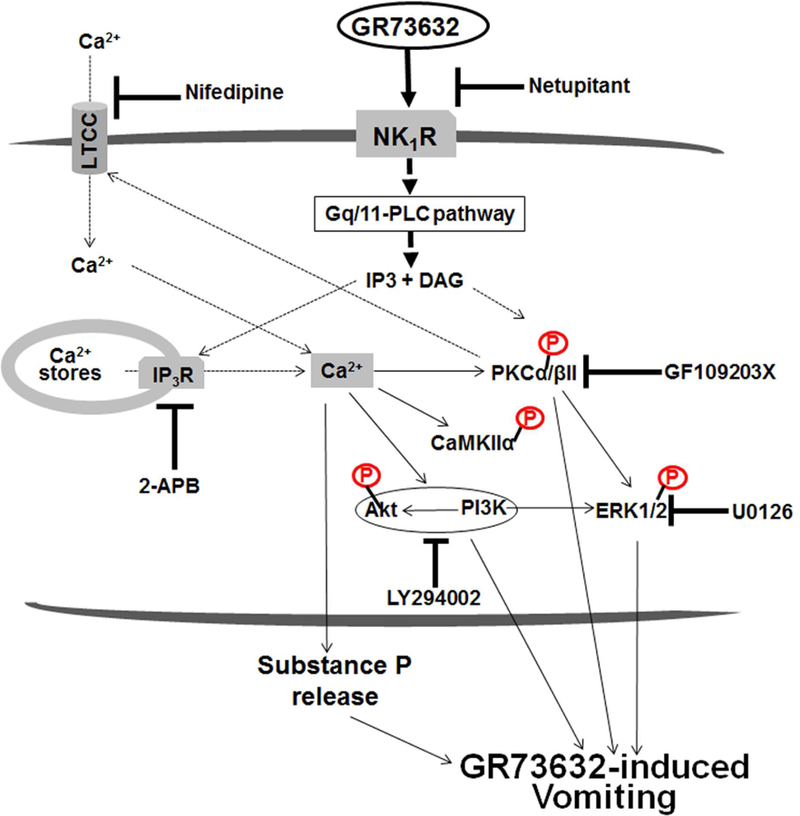

3.4. GR73632-stimulated LTCC-dependent activation of Akt downstream of PI3K is involved in ERK1/2 activation (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Schematic illustration of the potential intracellular pathways in the least shrew brainstem proposed to modulate the NK1R-mediated emesis.

Stimulation of NK1R can activate the Gq/11 protein-activating phospholipase C (PLC) signaling system in which accumulation of IP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG), subsequently trigger intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and PKC activation, respectively. Activated PKC can positively modulate Ca2+ influx through LTCC channels. In this study, potential mechanisms uunderlying the NK1R selective agonist GR73632-induced vomiting, involve stimulation of NK1Rs which results in intracellular Ca2+-release through IP3Rs and as well as extracellular Ca2+-influx via LTCCs. Both Ca2+ events are responsible for increasing intracellular Ca2+ which subsequently evokes substance P release in the brainstem emetic nuclei DMNX, and the activation/phosphorylation of CaMKIIα, PI3K-Akt and PI3K/PKCα/βII-ERK1/2 signals. Blockade/inhibition of NK1R (netupitant), LTCC (nifedipine), IP3R (2-APB), ERK1/2 (U0126), PKCα/βII (GF109203X) and PI3K (LY294002) respectively suppress GR73632-evoked vomiting to different degrees in the shrew. NK1R, neurokinin type 1 receptor; LTCC, L-type Ca2+ channel; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; IP3R, inositol-1, 4, 5-triphosphate receptor; CaMKIIα, Ca2+/calmodulin kinase IIα; PKCα/βII, α & βII isoforms of protein kinase C; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; Akt, protein kinase B; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase1/2.

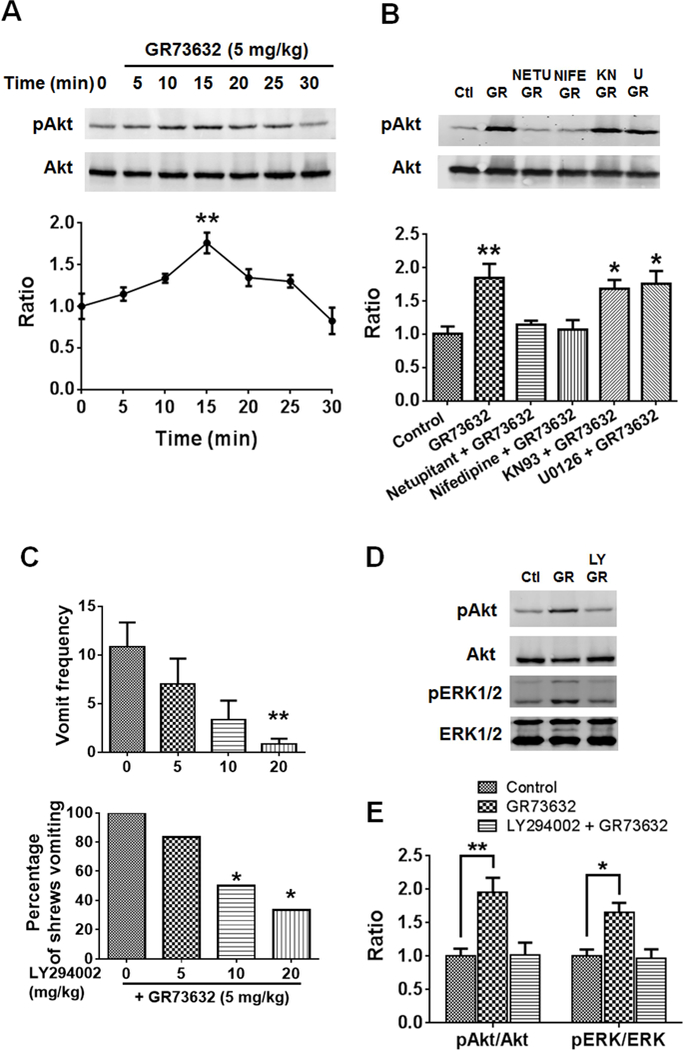

We examined Akt activation through assessment of GR73632-induced time-dependent increases in phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 via Western blot. Different groups of least shrews were treated (i.p.) for various time points (5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 min) with a 5 mg/kg dose of GR73632. Akt phosphorylation was significantly increased at 15 min (p = 0.0015) and returned to basal level (0 min) at 30 min post-GR73632 injection (p = 0.7520 vs. 0 min) (Fig. 4A). Thereafter, different groups of shrews were pretreated with either netupitant (10 mg/kg., i.p.), nifedipine (5 mg/kg., s.c.), KN93 (20 mg/kg, i.p.), U0126 (10 mg/kg., i.p.) or vehicle for 30 min followed by GR73632 injection. Phosphorylation level of Akt was examined at 15 min post-GR73632 treatment. The evoked increase in phosphorylation of Akt in response to GR73632 (p = 0.0081 between GR73632 and Control), was abrogated by netupitant (p = 0.9617 vs. Control) and nifedipine (p = 0.9984), but not by KN93 (p = 0.0319) or U0126 (p = 0.0178) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Involvement of LTCC in NK1R-dependent PI3K-ERK1/2 activation.

A. Western blots for time-course of Akt phosphorylation in the least shrew brainstems were collected at the indicated time points after GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) administration. Phospho-Akt S473 (pAkt) and Akt were detected by Western blot. The below panel shows quantitative analysis of Western blots. The ratios of p-Akt to Akt were compared. All ratios were normalized to vehicle-treated control (0 min) values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. ** p < 0.01 vs. 0 min, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n = 3. B. Effects of NK1R, LTCC, CaMKIIα and ERK1/2 inhibitors on Akt phosphorylation evoked by GR73632. Western blots of Akt phosphorylation in brainstems obtained from vehicle-treated control (Ctl) or the least shrews treated with GR73632 (5 mg/kg., i.p.) for 15 min in the absence (GR) or presence of an i.p. 10 mg/kg dose of netupitant (NETU+GR), s.c. 10 mg/kg dose of nifedipine (NIFE+GR), i.p. 20 mg/kg dose of KN93 (KN+GR), or an i.p. 10 mg/kg dose of U0126 (U+GR). All inhibitors were delivered 30 min prior to GR73632. Phospho-Akt S473 (pAkt) and Akt were detected by Western blot. The below panel shows quantitative analysis of Western blots. The ratios of pAkt to Akt were compared. All ratios were normalized to control values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 vs. Control, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n = 3. C. Antiemetic effects of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 on GR73632-induced emesis. Different groups of shrews received i.p. vehicle (0 mg/kg), or varying doses of LY294002, 30 min prior to GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Emetic parameters were recorded for 30 min post emetic injection. Upper panel shows frequency data presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6. ** p < 0.01 vs. LY294002 0 + GR73632, Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one-way ANOVA and followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Below panel shows the percentage of shrews vomiting. * p < 0.05, chi square test. D. Effect of the PI3K inhibitor on Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by GR73632. Shrews were pretreated (i.p.) for 30 min with 20 mg/kg LY294002 (LY+GR) or the vehicle (GR) and then stimulated with GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) for 15 min. Phospho-Akt S473 (pAkt), Akt, phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) and ERK1/2 in brainstems were detected by Western blot. Shown are representative western blots. E. Quantitative analysis of Western blots in D. The ratios of pAkt to Akt and pERK1/2 to ERK1/2 (pERK/ERK) were compared. All ratios were normalized to control values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 vs. Control, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n = 3.

We further examined whether PI3K-Akt activation pathway is involved in GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.)-evoked emesis in the least shrew by pharmacological means. Administration of varying doses of the specific PI3K-Akt pathway inhibitor LY294002 (0, 5, 10 and 20, i.p.) attenuated the frequency of induced emesis in a dose-dependent fashion [(KW (3, 20) = 10.39, p = 0.0155)] with a significant decrease at its 20 mg/kg (p 0.0087, vs. LY294002 0 + GR73632) (Fig. 4C). The chi square test also showed that the percentage of shrews vomiting in response to GR73632 was reduced by LY294002 at its 10 (p = 0.0455) and 20 mg/kg doses (p = 0.0143) (Fig. 4C).

The effects of LY294002 on Akt and ERK1/2 signaling were also examined. Pre-treatment of shrews with a 20 mg/kg LY294002 30 min prior to GR73632 injection (5 mg/kg, i.p.), attenuated the enhanced phosphorylation level of Akt observed 15 min post-GR73632 treatment (p = 0.0087 between Control and GR73632; p = 0.9945 between Control and LY294002+GR73632) (Fig. 4D, E). Moreover, LY294002 also prevented the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 evoked by GR73632 (p = 0.0124 between Control and GR73632; p = 0.9832 between Control and LY294002+GR73632) (Fig. 4D, E). The increased phosphorylation of Akt after GR73632 treatment is mediated by NK1R and is dependent on LTCC activity, and PI3K-Akt appears to act as an upstream regulator of ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

3.5. GR73632-stimulated LTCC-dependent activation of PKCα/βII is involved in ERK1/2 activation.

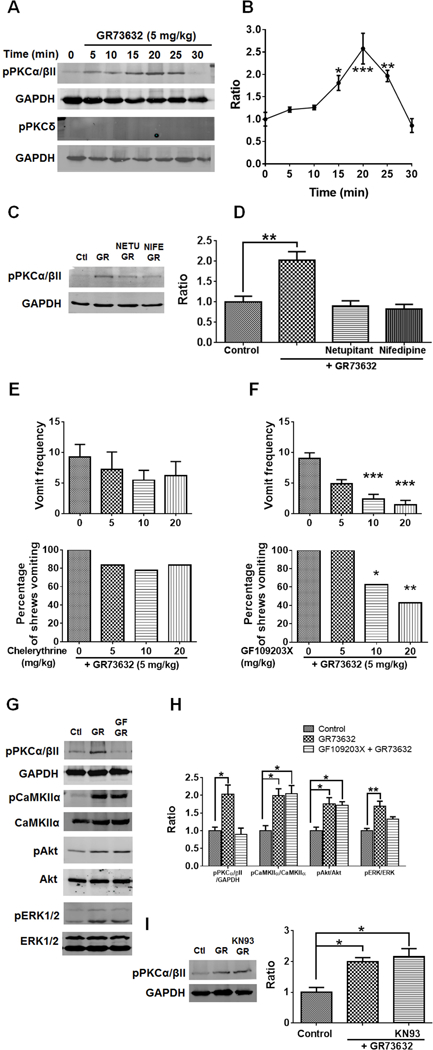

To determine the influence of GR73632 treatment on the phosphorylation state of several PKC isoforms, we examined the effect of GR73632 (5 mg/kg., i.p.) on the phosphorylation of PKCα/βII Thr638/641 and PKCδ Thr505 as well. GR73632 treatment significantly increased the phosphorylation of PKCα/βII Thr638/641 at the 15 (p = 0.0263 vs. 0 min), 20 (p = 0.0001) and 25 min (p = 0.0079) time-points, and subsequently returned to the vehicle-treated control level (0 min) (p = 0.9796) (Fig. 5A, B). In the case of PKCδ Thr505, no significant phosphorylation change was detected in all groups (Fig. 5A, B). We also investigated the possible inhibitory effect of prior treatment (30 min) with either the NK1R (netupitant 10 mg/kg (i.p.))-or LTCC (nifedipine mg/kg (s.c.))-antagonist on PKCα/βII Thr638/641 phosphorylation when shrews were subsequently administered with a 5 mg/kg dose of GR73632 for 15 min. Both netupitant and nifedipine independently and completely blocked the GR73632-evoked phosphorylation of PKCα/βII Thr638/641 (p = 0.0034 between GR73632 and Control; p = 0.9314 between Netupitant + GR73632 and Control; p = 0.7746 between nifedipine + GR73632 and Control) (Fig. 5C, D). The role of PKCα/βII Thr638/641 in GR73632-induced emesis was further investigated by pretreating (i.p.) different groups of shrews for 30 min with varying doses of either the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine (Fig. 5E) or the PKCα/βII more potent and selective inhibitor GF109203X (Asehnoune et al., 2005) (Fig. 5F). The tested doses of chelerythrine failed to attenuate either the frequency [(KW (3, 26) = 2.125, p = 0.5470)] or percentage [(χ2 (3, 26) = 2.115, p = 0.5488)] of shrews vomiting in response to 5 mg/kg GR73632. On the other hand, the 10 and 20 mg/kg doses of GF109203X suppressed both the frequency (p = 0.0009 and p = 0.0001 vs. GF109203X 0 + GR73632, respectively) and the percentage of shrews vomiting (p = 0.0429 and p = 0.0088 vs. GF109203X 0 + GR73632, respectively).

Fig. 5. Involvement of LTCC in NK1R-dependent PKCα/βII-ERK1/2 activation.

A. Representative Western blots for time-course of PKC isoforms activation in the least shrew brainstems collected at indicated time points after GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) administration. Phospho-PKCα/βII Thr638/641 (pPKCα/βII), phospho-PKCδ Tyr311 (pPKCδ) and GAPDH (loading control) were detected by Western blot. B. Quantitative analysis of Western blots shown in A. The ratios of pPKCα/βII to GAPDH were compared. All ratios were normalized to vehicle-treated control (0 min) values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 vs. 0 min, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n = 3. C. Representative Western blots of PKCα/βII phosphorylation in brainstems obtained from vehicle-treated control (Ctl) or the least shrews treated with GR73632 (5 mg/kg., i.p.) for 15 min in the absence (GR) or presence of an i.p. 10 mg/kg dose of netupitant (NETU+GR), or s.c. 10 mg/kg dose of nifedipine (NIFE+GR). All inhibitors were delivered 30 min prior to GR73632. Phospho-PKCα/βII Thr638/641 (pPKCα/βII) and GAPDH were detected by Western blot. D. Quantitative analysis of Western blots shown in C. The ratios of pPKCα/βII to GAPDH were compared. All ratios were normalized to control values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. ** p < 0.01 vs. Control, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n = 3. E-F. Antiemetic effects of PKC inhibitors on GR73632-produced emesis. Different groups of shrews received i.p. vehicle (0 mg/kg), varying doses of chelerythrine (i.p.) or GF109203X (i.p.), 30 min prior to an injection of GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Emetic parameters were recorded for the next 30 min. Upper panels show frequency data presented as mean ± SEM. n = 6–9. *** p < 0.001 vs. 0, Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one-way ANOVA and followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Below panels show the percentage of shrews vomiting. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01, chi square test. G-H. Effects of PKC inhibition with GF109203X on PKCα/βII, CaMKIIα, Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by GR73632. G. Representative Western blots of PKCα/βII, CaMKIIα, Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in brainstems obtained from vehicle-treated control (Ctl) or least shrews treated with GR73632 (5 mg/kg., i.p.) for 15 min in the absence (GR) or presence of an i.p. 20 mg/kg GF109203X (GF+GR). The inhibitor was delivered 30 min prior to GR73632. Phospho-PKCα/βII Thr638/641 (pPKCα/βII), GAPDH, phospho-CaMKIIα T286 (pCaMKIIα), CaMKIIα, phospho-Akt S473 (pAkt), Akt, phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) and ERK1/2 were detected by Western blot. H. Quantitative analysis of Western blots similar to those in G. The ratios of pPKCα/βII to GAPDH, pCaMKIIα to CaMKIIα, pAkt to Akt and pERK1/2 to ERK1/2 (pERK/ERK) were calculated. All ratios were normalized to control values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 vs. Control, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n = 3. I. Effect of CaMKIIα inhibiton by KN93 on PKCα/βII phosphorylation induced by GR73632. Shrews were pretreated (i.p.) for 30 min with 20 mg/kg KN93 (KN+GR) or the vehicle (GR) and then stimulated with GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) for 15 min. Phospho-PKCα/βII Thr638/641 (pPKCα/βII) and GAPDH in brainstems were detected by Western blot. Left panel shows the representative Western blots. Right panel show quantitative analysis of Western blots. The ratio of pPKCα/βII and GAPDH Was compared. All ratios were normalized to control values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. * p < 0.05 vs. Control, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n = 3.

The role of PKCα/βII in CaMKIIα, Akt and ERK1/2 activation was further studied by pretreating (i.p.) shrews for 30 min with or without 20 mg/kg GF109203X, followed by treatment with a 5 mg/kg GR73632 for 15 min. Besides a complete inhibition of PKCα/βII phosphorylation (p = 0.9067 between GF109203X + GR73632 and Control; p 0.0161 between GR73632 and Control), GF109203X partly prevented ERK1/2 phosphorylation evoked by GR73632 (Fig. 5G, H) (p = 0.0834 between GF109203X + GR73632 and Control; p = 0.0036 between GR73632 and Control). However, the GR73632-evoked CaMKIIα and Akt phosphorylation were not affected by GF109203X (for both kinases, p = 0.0151 between GF109203X + GR73632 and Control) (Fig. 5G, H). These results indicate a possible direct role for PKCα/βII for activation of ERK1/2 following NK1R stimulation by GR73632, and not via phosphorylation of either CaMKIIα or Akt. Furthermore, additional experiments were carried out as shrews were pre-treated (i.p.) with or without (vehicle) with a 20 mg/kg dose of the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 for 30 min and then stimulated with 5 mg/kg GR73632 for 15 min. As can be seen in Figure 5I, administration of KN93 did not affect the phosphorylation state of PKCα/βII in the KN93 + GR73632 group compared to vehicle + vehicle control group (p = 0.0086), suggesting CaMKII did not take part in PKCα/βII phosphorylation in GR73632-induced emesis.

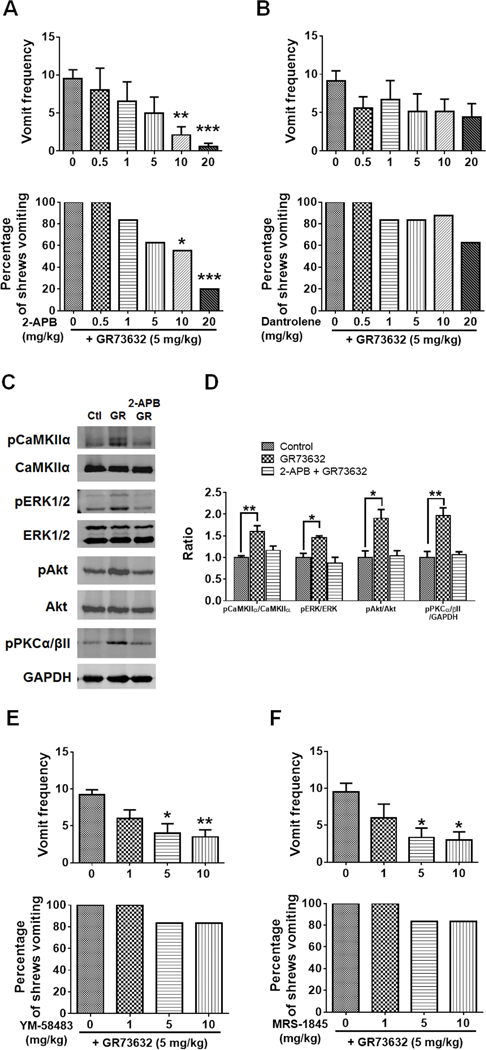

3.6. IP3R but not RyR is involved in GR73632-induced emesis and CaMKIIα/ERK1/2/Akt/PKCα/βII activation.

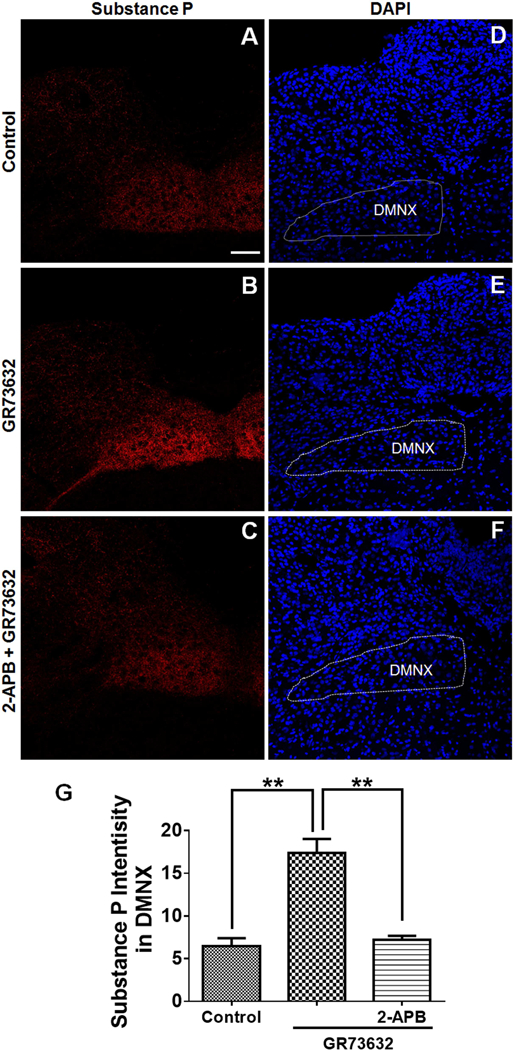

We next investigated whether Ca2+ release from the ER via RyR and/or IP3R were involved in GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.)-induced vomiting. Thus, a 30-min prior exposure to 2-APB (0.5, 1, 5, 10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p.), an antagonist of IP3R, dose-dependently suppressed both the GR73632-induced vomit frequency [KW (5, 41) = 22.56, p = 0.0004] and the percentage [χ2 (5, 41) = 17.92, p = 0.0031] of shrews vomiting with significant reductions occurring at 10 mg/kg (p = 0.0087 for frequency; p = 0.0311 for percentage) and 20 mg/kg doses (Fig. 6A, p = 0.0002 for frequency; p = 0.0007 for percentage). In contrast, the RyR antagonist dantrolene (0.5, 1, 5, 10 and 20 mg/kg, i.p.) had no effect on GR73632-evoked vomiting responses in both frequency [KW (5, 36) = 5.883, p = 0.3187] and percentage of shrews vomiting [χ2 (5, 36) = 6.497, p = 0.2608] (Fig. 6B). To verify the effects of 2-APB in reversing CaMKIIα, ERK1/2, Akt and PKCα/βII phosphorylation evoked by GR73632, shrews were pre-injected (i.p.) for 30 min with or without 20 mg/kg 2-APB, before treatment with 5 mg/kg GR73632 for 15 min. CaMKIIα, ERK1/2, Akt and PKCα/βII phosphorylation status in brainstems were analyzed by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 6C and D, 2-APB completely prevented phosphorylations of CaMKIIα (p = 0.3609 between 2-APB + GR73632 and Control; p = 0.0031 between GR73632 and Control), ERK1/2 (p = 0.5508 between 2-APB + GR73632 and Control; p = 0.0289 between GR73632 and Control), Akt (p = 0.9726 between 2-APB + GR73632 and Control; p = 0.0121 between GR73632 and Control) and PKCα/βII (p = 0.9224 between 2-APB + GR73632 and Control; p = 0.0049 between GR73632 and Control) evoked by GR73632. Further SP immunohistochemistry experiments were performed on non-vomiting shrews pretreated with 2-APB (20 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 min prior to GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) administration. In these animals, 2-APB abolished GR73632-evoked SP immunoreactivity increase in the DMNX (p = 0.0013 between GR and Control; p = 0.0019 between 2-APB + GR and Control) (Fig. 7A-C, G).

Fig. 6. Role of Ca2+ channels in GR73632-induced emesis and signaling cascades.

Effects of intracellular Ca2+ modulators on GR73632-induced emesis in the least shrews. Different groups of least shrews were given an injection (i.p.) of either the corresponding vehicle, or varying doses of: 1) the inositol-1, 4, 5-triphosphate receptor IP3R antagonist 2-APB (n = 6–10) (A); 2) the ryanodine receptor RyR antagonist dantrolene (n = 6–8) (B); 3) store-operated Ca2+ entry blockers YM-58483 (n = 6, s.c.) (E) or MRS-1845 (n = 6, s.c.) (F); 30 min prior to GR73632 injection (5 mg/kg., i.p.). The vomiting responses were recorded for 30 min post GR73632 administration. Upper panel shows the frequency data presented as mean ± SEM. *** p < 0.001 compared to 2-APB 0 + GR73632 (the corresponding vehicle-pretreated control), Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric one-way ANOVA and followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Below panel shows the percentage of shrews vomiting. C-D. Effects of 2-APB on CaMKIIα, ERK1/2, Akt and PKCα/βII phosphorylation evoked by GR73632. C. Representative Western blots of CaMKIIα, ERK1/2, Akt and PKCα/βII phosphorylation in brainstems obtained from vehicle-treated control (Ctl) or the least shrews treated with GR73632 (5 mg/kg., i.p.) for 15 min in the absence (GR) or presence of i.p. 20 mg/kg 2-APB (2-APB+GR). 2-APB was delivered 30 min prior to GR73632. Phospho-CaMKIIα T286 (pCaMKIIα), CaMKIIα, phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2), ERK1/2, phospho-Akt S473 (pAkt), Akt, phospho-PKCα/βII Thr638/641 (pPKCα/βII) and GAPDH were detected by Western blot. D. Quantitative analysis of Western blots shown in C. The ratios of pCaMKIIα to CaMKIIα, pERK1/2 to ERK1/2 (pERK/ERK), pAkt to Akt and pPKCα/βII to GAPDH were compared. All ratios were normalized to control values before analysis and expressed as fold change of control. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 vs. Control, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. n = 3.

Fig. 7.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the effect of 2-APB on GR73632-evoked substance P (SP) release in the least shrew brainstem. Coronal brainstem sections (20 μm) were prepared from different groups of shrews (n = 3 per group), including vehicle-treated control (A); 30 min post a 5 mg/kg (i.p.) injection of GR73632 (B); 30 min post GR73632 (5 mg/kg, i.p.) with 30-min pretreatment with 2-APB (20 mg/kg, i.p.). Sections were immunolabeled with rat SP antibody overnight followed by CYTM3-conjugated donkey anti-rat secondary antibody incubation. A-C. Representative 20x images of brainstem slice showing SP immunoreactivity among the brainstem emetic nuclei, area postrema (AP), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNX). Scale bar, 100 μm. D-F. Nuclei stained with DAPI in blue for A-C respectively. G. Quantitative analysis of substance P immunoreactivity among groups of A-C. Shown are means ± SEM of n = 3. ** p < 0.01 vs Control, One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test.

3.7. Effect of SOCE inhibitors on GR73632-induced emesis

In addition to IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER into cytosol due to increased IP3 levels following NK1R stimulation, store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) can also contribute to increased levels of cytosolic Ca2+ via activation of NK1Rs in the human airway smooth muscle cells (Mizuta et al., 2008). To confirm the involvement of SOCE-mediated Ca2+ mobilization in GR73632-induced emesis, we further investigated the anti-emetic effects of two SOCE inhibitors, YM-58483 and MRS-1845. As shown in Figure 6E, YM-58483 in part attenuated the frequency of GR73632-induced vomiting at its 5 (p = 0.0147) and 10 mg/kg doses (p = 0.0066), but had no significant effect on the percentage of shrews vomiting. Likewise, MRS-1845 partially attenuated the frequency of GR73632-induced vomiting at 5 mg/kg (p = 0.0305) and 10 mg/kg dose (p = 0.0239) (Fig. 6F), without affecting the percentage of shrews vomiting in response to GR73632.

4. Discussion

4.1. Central and peripheral components involved in GR73632-induced vomiting

NK1Rs are expressed in the brainstem DVC emetic nuclei including the AP, NTS and DMNX, as well as in the peripheral emetic loci in the GIT (Darmani et al., 2008; Ray et al., 2009b). Assessing the effect of ablation of central/peripheral NK1Rs on GR73632-evoked emesis in least shrews, our lab has affirmed a cardinal role for central NK1Rs in the initiation of the induced vomiting, and a facilitatory role for gastrointestinal NK1Rs, indicating activation of gastrointestinal NK1Rs is not required for the initiation of the vomiting process, but they are needed for rapid execution of vomit expulsion (Darmani et al., 2008). Ray et al. (2009b) further demonstrated that there is both a major central nervous system component and a minor peripheral nervous system component to tachykinin-mediated vomiting in least shrews. The present study provides insights into brainstem intracellular mechanisms by which NK1R stimulation by GR73632 induces emesis in the least shrew (see Fig. 8).

We have previously shown that following GR73632-evoked vomiting, significantly higher levels of Fos-immunoreactivity occur in the NTS and DMNX emetic nuclei in the shrew brainstem, as well as peripherally in many ENS neurons in the gut (Ray et al., 2009a). These central and peripheral emetic loci are well-known circuits involved in the emetic reflex (Ray et al., 2009a). Both c-Fos- and pERK1/2 have been adopted as neuronal activation markers in vivo (Ferrini et al., 2014; Zhong et al., 2016). In the current study, upon our initial observation that a time-dependent pERK1/2 increase in response to GR73632 can be detected via Western Blots of brainstem tissue, we subsequently used immunohistochemistry to demonstrate the occurrence of robust phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in brainstem slices containing the DVC emetic nuclei (AP, NTS and DMNX) 15 min post GR73632 treatment (Supplemental Fig. 1 and 2). The ENS contains submucosal and myenteric plexuses, in which neurons reside (Furness, 2000) and control intestinal motility and secretion (Sasselli et al., 2012). Additional immunostaining of pERK1/2 conducted on the shrew intestinal jejunum sections also demonstrate significantly higher pERK1/2-IR in neurons of the ENS, most likely in the myenteric plexus located between the outer longitudinal and circular muscle layers (Furness, 2000), following emesis evoked by GR73632 (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Double-labeling of pERK1/2 with the neuronal nuclei marker (NeuN) (Hendrickson et al., 2011) labelling the nuclei of almost all the enteric neurons in other species (Chiocchetti et al. 2003), revealed that almost all pERK1/2-positive cells in the shrew jejunal myenteric plexus and submucosal plexus also express NeuN (Supplemental Fig. 4). NeuN immunoreactivity in neurons of the ENS was robust in the nucleus and weakly present in the cytoplasm of the cell soma, consistent with the cytological distribution of NeuN as described in the literature (Hendrickson et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2010). Thus, our current findings confirms previous work that GR73632 administration can evoke activation of ENS neurons which can further enhance GIT activity and therefore further supports the involvement of GIT-related peripheral mechanisms in GR73632-evoked emesis.

NK1Rs are found in anatomical substrates of emesis in the brain and GIT, including the brainstem DVC composed of the emetic nuclei AP/NTS/DMNX, vagal afferents, enteric nervous system, and intestinal enterochromaffin cells (Darmani et al., 2008; Ray et al., 2009b). In brief, following the intraperitoneal GR736332 administration, due to its brain-penetrating ability (Darmani et al., 2008) and the lack of a brain-blood barrier of the AP region (Saito et al., 2003), it can act directly on the local neurons in the DVC area and/or on afferent terminals within these nuclei. The medial part of NTS, where emetic signals from the AP and the GIT are conveyed by the vagal afferents terminate preferentially and to a lesser extent in the AP and DMNX (Chu et al., 2014; Saito et al., 2003). The DMNX receives axonal projections from the NTS (Travagli and Anselmi, 2016), produces motor outputs and sends emetic signals via vagal efferents to the GIT and modulates the GIT motility (Babic and Browning, 2014; Darmani and Ray, 2009; Rojas and Slusher, 2015). The NK1Rs present on vagal afferents can also indirectly activate the brainstem emetic loci primarily to trigger vomiting (Chu et al., 2014). Meanwhile, the GIT can be another potential anatomical substrate of GR73632-induced emesis. GR73632 directly stimulates intestinal motility via acting on peripheral NK1Rs (Darmani et al., 2008). In addition, the vagal afferents carry input from the GIT to the brainstem DVC. Thus, the NK1Rs present on vagal afferents may also indirectly activate brainstem emetic loci to trigger vomiting (Chu et al., 2014).

4.2. Effects of the NK1 receptor antagonist netupitant

In addition to suppression of GR73632-induced emesis, the selective NK1R antagonist netupitant also concomitantly and significantly reduced or completely prevented GR73632-evoked phosphorylations (activation) of intracellular emetic signaling proteins CaMKII, PKC, ERK1/2 and Akt, suggesting that these GR73632-provoked responses are NK1R-dependent phenomena. Netupitant has already been shown to exert potent and broad-spectrum anti-emetic efficacy against diverse emetogenic stimuli (e.g. cisplatin, thapsigargin, apomorphine, morphine, ipecacuana, copper sulfate and motion) in least and house musk shrews as well as ferrets (Darmani et al., 2015; Rudd et al., 2016; Zhong et al., 2016). The current study sheds insights into intracellular mechanisms by which netupitant prevents GR73632-evoked vomiting.

4.3. GR73632-induced NK1R activation evokes Ca2+-dependent SP release

GR73632-evoked NK1R-mediated SP release has been reported in both cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons (Tang et al., 2008, 2007) and spinal tissue (Yang et al., 1996). GR73632 was also found to upregulate SP level in murine pancreatic acinar cells (Koh et al., 2012). Such SP release evoked by emetogens in the brainstem could also be a key mediator of emesis. In fact, a large dose of SP (50 mg/kg, i.p.) has been shown to concomitantly and time-dependently evoke increases in brainstem tissue SP concentration as well as vomiting in least shrews (Darmani et al., 2008). In the current study, we employed immunohistochemistry and found that in vehicle-treated control shrews weak basal SP immunoreactivity was present in the DMNX and NTS but at barely detectable levels in the AP area of the brainstem DVC under the experimental condition we applied in this study, consistent with our previous observations (Zhong et al., 2016). Previously we have demonstrated that SP-IR within the least shrew brainstem AP, NTS, and DMNX, where SP-staining followed by biotinylated secondary antibody incubation and further streptavidin binding for amplifying the signal were performed on 30 μm thick horizontal sections from the least shrew brainstem (Ray and Darmani, 2007). In fact, we had noticed weak SP-immunoreactivity in fibers and punctate structures in the AP under a high laser power (image not shown). In the current study, we conducted coronal sectioning of the least shrew brains. Furthermore, in the current study a fully emetic (5 mg/kg, i.p), but not an ineffective (1 mg/kg, i.p.) dose of GR73632 (Darmani et al., 2008), increased SP immunoreactivity in the shrew brainstem DMNX at 15 min and 30 min post GR73632 treatment. In fact, such rapid SP release can occur at 5 to 10 min post application of stimulus in vivo (Allen et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2014; Messlinger et al., 1998). Vomitings following GR73632 administration peak 4 −10min post injection, but some vomits do occur later up to a period of 30 min. GR73632 should be metabolized in the least shrew rapidly its metabolic rate is high (Darmani et al., 2008). Moreover, significant NK1R internalization (Marvizón et al., 1997) can occur after stimulation of NK1Rs. The evoked SP-release following NK1R activation by GR73632 may play a role in maintaining the vomiting after 15 min through acting on the non-internalized NK1Rs. However, this is our speculation and currently the exact role of released SP in our study still remains to be deciphered by further experiments. In addition, the NK1R is highly expressed in preganglionic neurons of the DMNX (Krowicki and Hornby, 2000). The DMNX has both motor output to the GIT and local circuit neurons, and thus SP-release in the DMNX as a consequence of NK1R activation by GR73632 could be due to stimulation of local circuit neurons and could contribute to the emetic motor output (Darmani et al., 2008). As discussed earlier, although it is fully accepted that the major site of emetic action of SP lies in the DVC emetic nuclei, the precise location(s) remain uncertain. Indeed, not only application of SP to the cells of NTS in ferrets results in vomiting (Gardner et al., 1994), but also direct injection of NK1R antagonists in the vicinity of medial NTS prevents cisplatin-induced vomiting (Gardner et al., 1994; Tattersall et al., 1996). However, in the dog the antiemetic site of action of NK1R antagonists was thought to be more central probably in the emetic pathway connecting the medial NTS to the central pattern generator for vomiting (Fukuda et al., 1998). The NTS consists of several subnuclei (Baude et al., 1989), which are not easy to differentiate due to the small size of the least shrew brainstem sections. Among them, the medial part of NTS receives inputs from the AP (Saito et al., 2003). In the least shrew brainstem coronal sections, only rarely more than one section contain the medial NTS (Darmani et al., 2008). The DMNX is known to receive inputs from the NTS and the medullary raphe nuclei as well (Lewis and Travagli, 2001). It also sends appropriate output to gastrointestinal tract to alter the GIT motility (Ray et al., 2009a and 2009b). Moreover excitatory functional effects through NK1Rs activation within the DMNX on vagal motor output result in the gastric relaxation, which precedes emesis (Castro et al., 2000; Lewis and Travagli, 2001; Krowicki and Hornby, 2000). Thus, we focused on the DMNX when we analyzed the SP-immunoreactivity intensity in this current study.

Stimulation of NK1R can activate the Gq/11 protein-activating phospholipase C signaling system via which accumulation of IP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG) occurs, the former subsequently triggers intracellular Ca2+ release, and the latter promotes PKC activation, respectively (Douglas and Leeman, 2011; Garcia-Recio and Gascón, 2015; Meshki et al., 2009). Activated PKC can positively modulate Ca2+ influx through LTCC channels (Weiss and Dascal, 2015). Evoked neurotransmitter release requires entry of Ca2+ in presynaptic terminals via multiple voltage-activated calcium channels among which L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs) can play a prominent role (Giugovaz-Tropper et al., 2011; Gu et al., 2009). Ca2+-dependent release of SP from peripheral nerve terminals in response to multiple stimuli has been well reviewed (White, 1997). In fact KCl-induced SP release in sensory nerves involves activation of LTCCs (Kopp and Cicha, 1999). Moreover, Ca2+-dependent SP release from the central terminals and axons of primary afferents in spinal cord slices in response to increased action potentials has also been demonstrated (Lao et al., 2003). Our current finding that GR73632-evoked elevation of SP immunoreactivity in the DVC area can be reversed by netupitant, the LTCC blocker nifedipine or 2-APB, suggests: i) an important role for LTCCs and IP3R in the induction of NK1R-mediated GR73632-evoked vomiting and SP release, and ii) the SP release is linked to NK1R-mediated increases in intracellular Ca2+ and an increase in neuronal excitability produced by NK1R-mediated activation of the phospholipase C pathway, which is associated with increased intracellular Ca2+ levels (Adelson et al., 2009).

4.4. NK1R activation-Ca2+ mobilization-signaling pathways

The role of Ca2+ as an essential factor for vomiting has been well investigated in our laboratory (Darmani et al., 2014; Zhong et al., 2016, 2014a, 2014b). Activation of different kinases by increased intracellular Ca2+ levels leads to a cross-talk among diverse intracellular signals that promote activation of downstream effectors which control cellular responses (Paredes-Gamero et al., 2006). Based upon our published findings regarding intracellular emetic signaling for other emetogens (Darmani et al., 2013; Zhong et al., 2016, 2014b), in this study we focused on the activation of emetic effector proteins CaMKII, ERK1/2, PI3K-Akt and PKC downstream of NK1Rs. In fact GR73632-mediated phosphorylation of these signaling proteins occurred in a time-dependent manner which complement the frequency of evoked vomiting and all of these events were reversed by both the NK1R antagonist netupitant and the LTCC antagonist nifedipine.

4.4.1. CAMKII-ERK1/2 signaling

CaMKII is a well-known downstream kinase and it undergoes autophosphorylation in response to elevated intracellular Ca2+, which is critical to the coordination and execution of Ca2+ signal transduction (Hudmon and Schulman 2002; Gustin et al., 2011). Through binding to Raf-1, CaMKII positively regulates ERK1/2 activation (Illario et al., 2003). We have demonstrated the essential role of Ca2+-CaMKII-ERK1/2 cascade in shrew brainstem following emesis evoked by both the 5-HT3R selective agonist 2-Me-5-HT (Zhong et al., 2014b) and selective sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin (Zhong et al., 2016). In the present study, we also demonstrate that GR73632 causes phosphorylation of both CaMKII and ERK1/2 following NK1R stimulation. However, a small though nonsignificant portion of GR73632-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation appears to be sensitive to CaMKII inhibitor (KN93), which suggests that ERK1/2 activation in the brainstem may not require active CaMKII. These results are also in line with our behavioral experiments, where the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 tended but could not significantly attenuate GR73632-evoked NK1R-mediated emesis, whereas the ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 caused near maximum reductions in the evoked mean vomit frequency and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Thus, GR73632-evoked CaMKII activation is not a major mechanism involved in NK1R-induced vomiting. In contrast, CaMKII inhibition has been shown to significantly suppress 2-Me-5-HT or thapsigargin-induced emesis in least shrews (Zhong et al., 2016, 2014b). As can be seen in the discussion later, these discording results appear to be due to involvement of other emetic signals and their potential interactions in NK1R-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation which ultimately contributes to the emesis. Thus, our current results indicate that the Ca2+-dependent ERK1/2 signaling is not restricted to 2-Me-5-HT (Zhong et al., 2014b) or thapsigargin (Zhong et al., 2016)-evoked vomiting, but may also participate in NK1R-mediated emesis. ERK1/2 probably represents one potential converging site where diverse emetic effectors can congregate to modulate GR73632-evoked emetic signaling. Indeed, maximal activation of ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) seems to accompany maximum brainstem tissue turnover of 5-HT and SP at peak vomit frequency during both the immediate and delayed phases of emesis caused by cisplatin in the least shrew (Darmani et al., 2013, 2009).

4.4.2. PKC-ERK1/2 pathway

To expand our understanding of mechanistic implications of NK1R in emesis, we investigated another Ca2+-dependent kinase PKC activation which also has been found to be coupled with ERK1/2 activation events (Lallemend et al., 2003; Ramnath et al., 2008). Among the PKC superfamily, a maximum PKCα/βII phosphorylation occurred in the shrew brainstem western blot at 15 min post GR73632 injection. No such change was detected in PKCδ phosphorylation following GR73632 administration in the shrew brainstem. However, substance P has been shown to induce early phosphorylation of PKCδ followed by increased activation of ERK1/2 in mice pancreatic acinar cells (Ramnath et al., 2008). This apparent discrepancy could be due to the differential distribution of PKC isoforms among different tissues. GF109203X is an inhibitor of PKCα, β, δ and ε with a ranked potency order, α > βI > ε > δ) (Lallemend et al., 2003). GF109203X pretreatment completely blocked GR73632-induced PKCα/βII phosphorylation in the shrew brainstem, and it also suppressed the GR73632-evoked ERK1/2 phosphorylation increase, but not completely. This finding indicates that ERK1/2 phosphorylation occurs downstream and is partially dependent upon PKCα/βII activation. This conclusion is in agreement with published findings in that PKCα phosphorylation can lead to ERK1/2 activation following SP-NK1R binding in mouse primary macrophages (Sun et al., 2009) and in rat spinal ganglion neurons (Lallemend et al., 2003). Therefore, PKC phosphorylation event appear to be upstream of ERK1/2 activation following stimulation of NK1Rs by GR73632. Furthermore, it appears that PKCα/βII is activated by GR73632 in parallel with CaMKII activation, since the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 had no marked effect on GR73632-induced PKCα/βII phosphorylation in the shrew brainstem, nor PKC inhibition with GF109203X affected CaMKII activation.

4.4.3. PI3K-ERK1/2

It was noted that PKC inhibitor GF109203X failed to completely prevent ERK1/2 phosphorylation and vomiting evoked by GR73632. This suggests that there may be a second PKC-independent signaling mechanism contributing to the process. ERK1/2 activation can be blocked by PI3K-Akt pathway inhibition (Zhuang et al., 2004). LY294002 is an inhibitor of the PI3K-Akt pathway and has been extensively used to study the role of PI3K in the regulation of different intracellular pathways (Sun et al., 2009). In the current study, LY294002 suppressed both GR73632-evoked ERK1/2 phosphorylation and vomiting in shrews, confirming an important role for the PI3K-Akt pathway in NK1R-mediated responses. Neither CaMKII, ERK1/2 nor PKC inhibition prevented Akt phosphorylation, indicating Akt is independent of CaMKII, ERK1/2 and PKC (see Fig. 7). Possibilities of crosstalk among the discussed pathways or their independence from each other have been extensively described. Indeed, PKC-ERK1/2 activation is found to be downstream of PI3K (Mookerjee Basu et al., 2006), while the PI3K pathway does not mediate the effect of SP on ERK1/2 activation (Lallemend et al., 2003). Our findings indicate that the PI3K and PKC converge on ERK1/2 to serve as primary mediators to sustain the vomiting behavior through individual/parallel components of the NK1R signaling pathway (see Fig. 7). In addition, the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 completely abrogated ERK1/2 activation evoked by GR73632, whereas PKC inhibition failed to exert its inhibitory effect to the same extent, suggesting PI3K may play a more significant role in contributing to ERK1/2 activation following NK1R stimulation. The role of phosphorylation of PI3K downstream signaling protein Akt in the evoked vomiting appears to be complex and is under further study in our laboratory. Importantly, the results presented in this study further support the critical involvement of ERK1/2 in emesis.

4.5. Role of Ca2+ channels IP3R/RyR in GR73632-induced emesis

We have previously shown that intracellular Ca2+ release channels RyRs and IP3Rs can be differentially modulated by diverse emetogens including 2-Me-5-HT (Zhong et al., 2014b) and thapsigargin (Zhong et al., 2016). Intracellular Ca2+ elevation has been reported in response to NK1R activation by both SP and GR73632 in cultured neurons in vitro (Ito et al., 2002; Miyano et al., 2010). In this in vivo study, we explored the role of RyRs and IP3Rs in GR73632-induced vomiting via pharmacological manipulation with their respective antagonists, dantrolene and 2-APB. Unexpectedly, GR73632-induced emesis was insensitive to dantrolene, but in contrast, both the frequency and percentage of shrews vomiting were significantly suppressed by 2-APB at 20 mg/kg. In addition, 2-APB blocked activation of GR73632-evoked signaling pathways involving the discussed phosphorylated kinases. Thus, our results indicate that the GR73632-evoked effects depend primarily on intracellular Ca2+-release from the ER Ca2+ stores through IP3Rs but not RyRs, as well as Ca2+ influx through LTCC. This conclusion is in agreement with Miyano et al.’s (2010) observation that the stimulation of the NK1R by GR73632 in spinal astrocytes initially induces intracellular Ca2+ release through IP3R channels. Likewise, Lin and co-workers (Lin et al., 2005) have confirmed that the SP-evoked intracellular Ca2+-release is followed by extracellular Ca2+-influx and the corresponding muscle responses in swine trachea were potently attenuated by the LTCC blocker verapamil and the IP3R inhibitor 2-APB.

4.6. The role of SOCE in GR73632-induced vomiting

Ca2+ release from IP3Rs evoked by IP3 has been shown to couple with extracellular Ca2+ influx through LTCCs in non-excitable cells such as Jurkat human T lymphocytes (Wang and Wu, 2011) and drosophila S2 cells (Wang et al., 2015), as well as in excitable cells such as submucosal neurons in the rat distal colon (Rehn et al., 2013). Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) at the plasma membrane can be activated subsequent to emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores through IP3R- and/or RyR-channels in both non-excitable cells and excitable neuronal cells (Parekh and Putney, 2005; Putney, 2003; Putney and McKay, 1999). Upon agonist stimulation, Ca2+ entry has been confirmed involving co-activation of SOCE and LTCC (Ávila-Medina et al., 2016). In the current study we found that relative to complete suppression of GR73632-evoked vomiting by nifedipine at 5 mg/kg dose, administration of potent and selective SOCE inhibitors YM-58483 (Gao et al., 2013) or MRS-1845 (Li et al., 2013), can only partially reduce the frequency of evoked vomiting without providing significant emesis protection (p > 0.05), even at a large dose (10 mg/kg), indicating a clear contribution of LTCC-mediated Ca2+ influx and a minor role for SOCE in the mechanisms underlying NK1R-mediated vomiting. As Putney (2003) already suggested, the magnitude of SOCE is much smaller than the voltage-gated entry, and therefore may be not necessarily correlated with the physiological significance of this signal. Thus, though 2-APB has been applied as a less specific inhibitors of SOCE (Ávila-Medina et al., 2016) and has been used as an experimental tool that activates then inhibits SOCE (DeHaven et al., 2008), our data that there is no major role for SOCE in NK1R-mediated GR73632-evoked vomiting indicates that the 20 mg/kg dosage of 2-APB utilized in this study mainly exerts inhibitory effect on IP3R.

5. Conclusion

Taken together, our results demonstrate that GR73632 is a potent emetogen and subsequent NK1R-evoked emesis is associated with Ca2+ mobilization involving both intracellular Ca2+ release from the ER Ca2+ stores through IP3Rs, as well as extracellular Ca2+ influx mainly via LTCCs. Both processes are prerequisite to subsequent Ca2+-dependent activation of diverse interplaying signaling systems involving PKCα/βII-ERK1/2 and PI3K-ERK1/2 pathways. The present study highlights how different intracellular effector signaling systems cooperate in the induction of NK1R-mediated emetic effects. Moreover, involvement of such complex array of intracellular emetic signals in NK1R-evoked emesis whose blockade at the receptor level underscores broad-spectrum antiemetic nature of NK1R antagonists, whereas antiemetic activity of 5-HT3R antagonists may involve relatively less complex signaling pathway involving 5-HT3R/LTCC extracellular Ca2+ influx/intracellular Ca2+ release via RyR/CaMKIIα/ERK1/2 (Zhong et al., 2014b). The 5-HT3 and NK1 receptors exhibit crosstalk (Rojas et al., 2014) and therefore shared components of the signaling pathways between them implicate the crosstalk at the intracellular level. Considering significance of NK1R antagonists in preventing CINV, current validation of the signaling systems underlying the evoked emesis may help develop new anti-CINV strategies targeting specific emetic mechanisms linking initial Ca2+ mobilization to downstream intracellular signaling systems.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Neurokinin type 1 receptor (NK1R) agonist GR73632 induces emesis in least shrews.

GR73632 increases substance P in the brainstem emesis-associated nucleus, DMNX.

GR73632 evokes CaMKIIα, ERK1/2, Akt and PKCα/βII phosphorylation in brainstem.

NK1R, L-type calcium channel and intracellular calcium release channel IP3R are involved in GR73632-evoked emesis involving above emetic signals.

PI3K-ERK and PKC-ERK signaling pathways are involved in GR73632-induced emesis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH-NCI grant (CA207287) and WesternU intramural startup fund (1395) to NAD.

Abbreviations

- 5-HT

5-Hydroxytryptamine = Serotonin

- 5-HT3R

Serotonin type 3 receptor

- SP

substance P

- NK1R

neurokinin type 1 receptor

- CINV

chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting

- DVC

dorsal vagal complex

- AP

area postrema

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitaries

- DMNX

dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus

- ENS

enteric nerves system

- GIT

gastrointestinal tract

- EC cells

enterochromaffin cells

- LTCC

L-type Ca2+ channel

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- CaMKIIα

Ca2+/calmodulin kinase IIα

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase1/2

- 2-Me-5-HT

2-methyl-serotonin

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- PKCα/βII

α and βII isoforms of protein kinase C

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- Akt

protein kinase B

- SOCE

store-operated Ca2+ entry

- IP3R

inositol-1, 4, 5-triphosphate receptor

- pERK1/2

phospho-ERK1/2

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Disclaimer (not mandatory)

Part of the data was presented at the MASCC/ISOO Annual Meeting in Vienna, 29th June 2017, Abstract # 0343.

References

- Adelson D, Lao L, Zhang G, Kim W, Marvizón JC. Substance P release and neurokinin 1 receptor activation in the rat spinal cord increase with the firing frequency of C-fibers. Neuroscience 2009; 161: 538–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen BJ, Rogers SD, Ghilardi JR, Menning PM, Kuskowski MA, Basbaum AI, Simone DA, Mantyh PW. Noxious cutaneous thermal stimuli induce a graded release of endogenous substance P in the spinal cord: imaging peptide action in vivo. J Neurosci 1997; 17: 5921–5927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadoro G, Pieri M, Ciotti MT, Carunchio I, Canu N, Calissano P, Zona C, Severini C. Substance P provides neuroprotection in cerebellar granule cells through Akt and MAPK/ERK1/2 activation: evidence for the involvement of the delayed rectifier potassium current. Neuropharmacology 2007; 52: 1366–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PLR, Rudd JA. The role of tachykinins and the tachykinin NK1 receptor in nausea and emesis. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2004; 164: 359–440. [Google Scholar]

- Asehnoune K, Strassheim D, Mitra S, Yeol Kim J, Abraham E. Involvement of PKCalpha/beta in TLR4 and TLR2 dependent activation of NF-kappaB. Cell Signal 2005; 17: 385–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Medina J, Calderón-Sánchez E, González-Rodríguez P, Monje-Quiroga F, Rosado JA, Castellano A, Ordóñez A, Smani T. Orai1 and TRPC1 Proteins Co-localize with CaV1.2 Channels to Form a Signal Complex in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. J Biol Chem 2016; 291: 21148–21159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic T, Browning KN. The role of vagal neurocircuits in the regulation of nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol 2014; 722: 38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baude A, Lanoir J, Vernier P, Puizillout JJ. Substance P-immunoreactivity in the dorsal medial region of the medulla in the cat: effects of nodosectomy. J Chem Neuroanat 1989; 2: 67–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro A, Mearin F, Larish J, Malagelada JR. Gastric fundus relaxation and emetic sequences induced by apomorphine and intragastric lipid infusion in healthy humans. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 3404–3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chebolu S, Wang Y, Ray AP, Darmani NA. Pranlukast prevents cysteinyl leukotriene-induced emesis in the least shrew (Cryptotis parva). Eur J Pharmacol 2010; 628: 195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, McRoberts JA, Marvizón JC. μ-Opioid receptor inhibition of substance P release from primary afferents disappears in neuropathic pain but not inflammatory pain. Neuroscience 2014; 267: 67–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiocchetti R, Poole DP, Kimura H, Aimi Y, Robbins HL, Castelucci P, Furness JB. Evidence that two forms of choline acetyltransferase are differentially expressed in subclasses of enteric neurons. Cell Tissue Res 2003; 311: 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Youm JB, Earm YE, Ho WK. Inhibition of acetylcholine-activated K(+) current by chelerythrine and bisindolylmaleimide I in atrial myocytes from mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 424: 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CC, Hsing CH, Shieh JP, Chien CC, Ho CM, Wang JJ. The cellular mechanisms of the antiemetic action of dexamethasone and related glucocorticoids against vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol 2014; 722: 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Chebolu S, Amos B, Alkam T. Synergistic antiemetic interactions between serotonergic 5-HT3 and tachykininergic NK1-receptor antagonists in the least shrew (Cryptotis parva). Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2011; 99: 573–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Crim JL, Janoyan JJ, Abad J, Ramirez J. 2009. A re-evaluation of the neurotransmitter basis of chemotherapy-induced immediate and delayed vomiting: evidence from the least shrew. Brain Res 2009; 1248: 40–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Dey D, Chebolu S, Amos B, Kandpal R, Alkam T. Cisplatin causes over-expression of tachykinin NK(1) receptors and increases ERK1/2- and PKA-phosphorylation during peak immediate- and delayed-phase emesis in the least shrew (Cryptotis parva) brainstem. Eur J Pharmacol 2013; 698: 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Ray AP. Evidence for a re-evaluation of the neurochemical and anatomical bases of chemotherapy-induced vomiting. Chem Rev 2009; 109: 3158–3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Wang Y, Abad J, Ray AP, Thrush GR, Ramirez J. Utilization of the least shrew as a rapid and selective screening model for the antiemetic potential and brain penetration of substance P and NK1 receptor antagonists. Brain Res 2008; 1214: 58–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Zhong W, Chebolu S, Mercadante F. Differential and additive suppressive effects of 5-HT3 (palonosetron)- and NK1 (netupitant)-receptor antagonists on cisplatin-induced vomiting and ERK1/2, PKA and PKC activation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2015; 131: 104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA, Zhong W, Chebolu S, Vaezi M, Alkam T. Broad-spectrum antiemetic potential of the L-type calcium channel antagonist nifedipine and evidence for its additive antiemetic interaction with the 5-HT(3) receptor antagonist palonosetron in the least shrew (Cryptotis parva). Eur J Pharmacol 2014; 722: 2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmani NA. Serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists prevent cisplatin-induced emesis in Cryptotis parva: a new experimental model of emesis. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 1998; 105: 1143–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Bird GS, Putney JW Jr. J Biol Chem. Complex actions of 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate on store-operated calcium entry 2008; 283: 19265–19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]