Abstract

Pathological angiogenesis is a hallmark of many diseases. Previously, we reported that orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 (human homolog, Nur77, mouse homolog) is a critical mediator of angiogenesis to regulate tumor growth and skin wound healing via down-regulating the expression of the junctional proteins and integrin β4. However, the molecular mechanism, by which TR3/Nur77 regulated angiogenesis, was still not completely understood. In this report by analyzing the integrin expression profile in endothelial cells, we found that the TR3/Nur77 expression highly increased the expression of integrins α1 and β5, decreased the expression of integrins α2 and β3, but had some or no effect on the expression of integrins αv, α3, α4, α5, α6, β1 and β7. In the angiogenic responses mediated by TR3/Nur77, integrin α1 regulated endothelial cell proliferation and adhesion, but not migration. Integrin β5 shRNA inhibited cell migration, but increased proliferation and adhesion. Integrin α2 regulated all of the endothelial cell proliferation, migration and adhesion. However, integrin β3 did not play any role in endothelial cell proliferation, migration and adhesion. TR3/Nur77 regulated the transcription of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5, via various amino acid fragments within its transactivation domain and DNA binding domain. Furthermore, TR3/Nur77 regulated the integrin α1 promoter activity by directly interacting with a novel DNA element within the integrin α1 promoter. These studies furthered our understanding of the molecular mechanism by which TR3/Nur77 regulated angiogenesis, and supported our previous finding that TR3/Nur77 was an excellent therapeutic target for pathological angiogenesis. Therefore, targeting TR3/Nur77 inhibits several signaling pathways that are activated by various angiogenic factors.

Keywords: TR3/Nur77, angiogenesis, integrin, promoter, Proliferation, migration

Introduction

Pathological angiogenesis is a hallmark of many diseases including cancer, inflammation, wound healing and ischemic heart disease. Neutralizing antibodies against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) kinase/multiple kinase inhibitors have been successfully developed and widely used in the clinic (reviewed in (1)). However, in addition to their side effects (2), VEGF-targeted therapies in cancer face the problems of insufficient efficacy (3–12), resistance and intrinsic refractoriness (10, 13, 14). Therefore, it is desirable to identify additional angiogenesis targets. Our recent studies demonstrated that TR3/Nur77 (human: TR3, mouse: Nur77, rat: NGFI-B) was one of such promising targets (15–17).

TR3/Nur77 is a member of the nuclear receptor IV subfamily of the transcription factors, without identified physiological ligand (18), although several agonists, cytosporone B and a series of methylene-substituted diindolymethanes, were identified (19, 20). The nuclear receptor IV subfamily members play redundant roles in TCR-mediated apoptosis (21) and brown fat thermogenesis (22, 23). However, they play different roles in development (reviewed in (24)). TR3/Nur77 also plays important roles in cancer cell biology, inflammation, metabolic diseases, stress and addiction (reviewed in (25–28)).

Prior to our recent studies (16), little was known about the role of TR3/Nur77 in angiogenesis. Our studies demonstrated that TR3/Nur77 was a critical mediator of angiogenesis. We found that TR3/Nur77 was highly and transiently up-regulated in cultured endothelial cells (EC) and during angiogenesis in vivo. TR3/Nur77 was induced by the angiogenic factors having microvessel permeable activity, including VEGF, histamine and serotonin, but not by the angiogenic factors without microvessel permeable activity, including basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), placental growth factor (PlGF) and platelet-derived growth factor PDGF (15–17), and in postnatal angiogenesis, such as tumor angiogenesis and skin wound healing (16, 29). In the gain of function assays, the overexpression of TR3/Nur77 protein was sufficient to induce endothelial cell proliferation, migration and tube formation in vitro. Angiogenesis, microvessel permeability and normal skin wound healing were greatly induced/improved in our transgenic EC-Nur77-S mice, in which the full length Nur77 was inducibly and specifically expressed in mouse endothelium (15–17). The transgenic EC-Nur77-S mice were healthy after Nur77 had been induced for three months (29). In the loss of function assays, the knockdown of TR3 expression by its antisense DNA or shRNA inhibited endothelial cell proliferation, migration and tube formation induced by VEGF, histamine and serotonin in vitro (15–17). Tumor growth, angiogenesis and microvessel permeability induced by VEGF, histamine or serotonin were almost completely inhibited in Nur77 knockout mice (15–17). Paradoxically, however, Nur77 null mice are viable, fertile, appear to develop a normal adult vasculature and have no defect on normal skin wound healing (21, 29). Our studies demonstrated that TR3/Nur77 was an excellent target for pro-angiogenesis and anti-angiogenesis therapies.

Our studies further demonstrated that TR3/Nur77 regulated angiogenesis in the early stage (15–17). In adult vessels, vascular integrity is maintained by the endothelial cell-endothelial cell (EC-EC) junctions and the endothelial cell-basement membrane (EC-BM) interactions that are regulated by integrins. In order to induce angiogenesis, both of these interactions must be altered to facilitate endothelial cell proliferation and migration. Recently, we reported that TR3/Nur77 regulated the expression of eNOS, protein components in VE-cadherin associated adherent junctions, and integrin β4, to induce angiogenesis (17, 29). However, it was still not known whether TR3/Nur77 regulated the expression of other integrins that played important roles in angiogenesis. In this study, we analyzed the expression profile of integrin genes that might be regulated by TR3/Nur77, studied the function of integrins in TR3/Nur77-mediated angiogenic responses, and investigated the molecular mechanism, by which TR3/Nur77 regulated the expression of integrins.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The recombinant human VEGF was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Histamine, Flag antibody (Cat. No. F-3165), and actinomycin D (Cat. No. A1410) were purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC, St. Louis, MO). The antibodies against pAkt-S473 (Cat. No. 9271), Akt (Cat. No. 9272), phospho-p42/p44 MAPK (Cat. No. 9106S) and p42/p44 MAPK (Cat. No. 9211) were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). The antibodies against TR3/Nur77 (Cat. No. sc-5569), integrin α2 (Cat. No. SC-6586), integrin β3 (Cat. No. SC-14009) and integrin β5 (Cat. No. SC-14010) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The integrin α1 antibody (MAB1973) was purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Endothelial cell basal medium (EBM), EGM-MV BulletKit, Trypsin/EDTA, and trypsin neutralization solution were obtained from Lonza (Allendale, NJ). Vitrogen 100 was purchased from Collagen Biomaterials (Palo Alto, CA, USA).

Cell Culture

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human dermal microvessel endothelial cells (HDMVECs) purchased from Lonza (Allendale, NJ) were grown on the plates coated with 30 μg/ml vitrogen in EBM supplemented with EGM-MV BulletKit. The HUVECs of passages 5 were used for all of the experiments.

Adenoviruses expressing integrin shRNAs and cDNAs

The shRNA oligonucleotides were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa), then annealed and cloned to a pENTR1A-stuffer vector that was modified from the lentiviral vector pLKO.1 (Addgene, Boston, MA) with a pU6 promoter and a PURO element (our unpublished data), via the restriction enzymes AgeI and EcoRI. The pENTR1A-shRNA plasmids were used as the entry clones and transferred to the pAd/PL-DEST vector following the instruction provided by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The sense sequences of shRNAs were shITGA1–1213, 5’CAGTTGTCATGCA GAAGGCTAGTCAAA 3’; shITGA1–596, 5’CAGAATGGATATTGGTCCTAAACAGAC3’; shITGB5, 5’AGCTTGTTGTCC CAATGAAAT3’; and shGFP, 5’GCAAGCTGACCCTGAAGTTC AT3’.

To clone the integrin α2 cDNA, the N-terminus and the C-terminus of the integrin α2 cDNA were obtained by RT-PCR with the RNA isolated from HUVECs using the primer pairs of ITGA2 cDNA.XhoI.F1 / ITGA2cDNA.R2322, and ITGA2cDNA.F1642 / ITGA2cDNA.BamHI.R3546, respectively. The two PCR products were digested with the restriction enzymes XhoI + HindIII and HindIII + BamHI, respectively, and then ligated into the pCR2.1-TOPO vector that was digested with the restriction enzymes XhoI and BamHI, to obtain the plasmid pCR2.1-TOPOITGA2. The coding region was sequenced correct. The integrin α2 cDNA was digested from the pCR2.1-TOPO-ITGA2 with the restriction enzymes XhoI and BamHI, and subcloned into the retroviral expression vector pCMBP (30), to obtain the pCMBP-ITGA2cDNA plasmid. Similarly, the ITGB3 cDNA was obtained by RT-PCR from HUVEC mRNA with the primer pair of ITGB3.cDNA.XhoI.F1 and ITGB3.cDNA.BamHI.R2367, and cloned into the pCBMP vector. The primer sequences are listed in the Supplemental Material.

The retroviruses expressing ITGA2 and ITGB3 were prepared and used to infect HUVECs as described previously (31). Briefly, 293T cells were seeded at a density of 6 × 106 cells per 100 mm plate 24 h before transfection. DNA transfection was carried out with the Effectene™ Transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Two μg of each target gene, 1.5 μg of pMD.MLV gag.pol, and 0.5 μg of pMD.G DNA, encoding the cDNAs of the proteins which are required for virus packaging (kindly provided by Dr. Mulligan), were mixed in 300 μl of EC buffer. Thirty-two μl of enhancer was added to the DNA mixture. Five minutes later, 30 μl of effectene was added to the DNA mixture. After incubated at room temperature for at least 10 min, the DNA mixture was added dropwisely to 293T cells. The medium was changed after 16 h. The retroviruses were collected 48 h after transfection and used immediately for infection or frozen at –70°C.

Twenty-four hours before infection, HUVECs were seeded at a density of 0.3 × 106 cells per 100 mm plate. One ml of retrovirus solution (~2 ×107 pfu/ml) and 5 ml of fresh medium was added to the cells with 10 μg/ml polybrene. The medium was changed after 16 hours. Forty-eight hours after infection, the cellular extracts were collected and subjected to immunoblotting to confirm the expression of the integrins α2 and β3 proteins.

Then the integrin α2 and β3 cDNAs were subcloned to the adenovirus expression vector pAd/PL-DEST via the pENTR1A as an entry cloning vector, following the instruction provided by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Adenoviruses were prepared in the similar way following the Gateway® Technology protocol. Briefly, 1 μg of the expression plasmid in the pAd/CMV/V5-DEST using Gateway® Technology was digested with the restriction enzyme Pac I and then transfected into 293T Cells with TransIT 2020 (Mirus, Madison, WI) to produce a crude adenoviral stock. To amplify the adenoviruses, 293T cells were infected with the crude adenoviral stock, harvested when there were plags in the cell layer or the cells detached from the plate. The cells were lysed to release the adenovirus particles by three cycles of freezing (−80°C) / thawing (37°C). The lysed cells were centrifuged at 4000 RPM for 10 min. The supernatant was ultracentrifuged in a CsCl gradient. The adenoviruses were collected, dialyzed, aliquoted and frozen in −80°C.

Proliferation assay

Twenty-four hours after seeded in 96-well plates (2 × 103 cells/well), the HUVECs were transduced with the viruses as indicated. Forty-eight hours after transduction, the cells were serum-starved with 0.1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in EBM for 48 hours. The Cell Counting Kit-8 reagent (CK04–11, Dojindo) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 3 hours before the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Monolayer migration assay

The HUVEC monolayer migration assay was carried out as described previously (15). Briefly, HUVECs (6 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were transduced with the viruses as indicated. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were serum-starved with 1% FBS in EBM for 24 h. Scratch wound was generated with a 200 μl pipette tip and photographed immediately as 0 h, and at 16 h, respectively. The cells migrated to the wound area were counted. The results were expressed as mean ±SD of 6 views.

Cell adhesion assay

HUVECs (1.5 × 105 cells/plate) were seeded in 60 mm plates. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were transduced with the viruses as indicated. Forty-eight hours later, the cells were serum-starved with 1% FBS in EBM for 48 hours, or serum-starved for 24 hours and stimulated with VEGF for 24 hours. Then, the cells were harvested with 0.25% trypsin, centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 3 min, washed with 10 ml of Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) for 3 times, and resuspended in 800 μl of adhesion buffer that contains RPMI1640 medium, 1mM MgCl2 and 0.5% BSA. The cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded on 48-well-plate. After incubated for 30 min, the cells were washed 3 times with warm PBS, stained with 0.1% crystal violet (100 μl/well) for 10 min, washed with warm PBS 3 times carefully, and incubated with 100 μl of 10% acetic acid at room temperature. The optical density (OD) value was measured at 600 nm using a microplate reader.

mRNA stability assay

HUVECs (3×105 cells/plate) were seeded on 60 mm plates. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were infected with the adenoviruses expressing TR3/Nur77, or Lac Z as a control. Sixteen hours later, the cells were treated with actinomycin D (10 μg/ml) to inhibit mRNA synthesis, and then incubated for 8 hours. The RNA was collected with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and subjected to real-time PCR with the indicated primers.

Construction of the promoter luciferase reporters and the luciferase assay

The promoter luciferase reporter constructs were prepared as described in the supplemental data. All of the plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing. For luciferase assay, HUVECs (6×104 cells/well) were seeded on 12-well plates. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were washed with Minimum Essential Media (MEM) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) three times and transfected with promoter luciferase construct (4 wells per group) and infected with the adenoviruses as indicated at the same time. The pGL3-integrin α1 promoter construct (990 ng / well) was added to 80 μl of MEM. The pRT-SV40 luciferase vector in 20 μl of MEM, serving as an internal control (10 ng/well), was added to the mixture of promoter construct. One μl of TransIT2020 (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison, WI) was then added to the DNA mixture. The transfection mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 to 30 minutes and then added to the cells. The adenoviruses expressing Lac Z as a control, or TR3/Nur77 (16, 32) was added to the cells. Six hours later, the cells were changed to MEM. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were lysed and subjected to luciferase analysis with Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI), following the instruction provided by the company. The luciferase activity in each well was normalized to the internal luciferase activity. The data were expressed as the average fold change of luciferase activity in the TR3/Nur77-expressing cellsrelating to that in the Lac-Z expressing cells.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (CHIP)

CHIP assays were performed according to the protocol provided by the company (CHIP assay, Upstate, Charlottesville, Virginia). Briefly, the HUVEC pellets were sonicated. A small portion of the sample was saved as the input. The remainings of the samples were cross-linked with formaldehyde and then subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with the antibodies against TR3/Nur77 and IgG as a control at 4 °C overnight. After extensively washed, half of the immunoprecipitated samples were eluted with SDS-sample buffer for immunoblotting analysis. The other half was used to extract DNA with phenol-chloroform followed by the ethanol precipitation. The DNA precipitate was resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA) and subjected to PCR assay with the primers amplifying the regions containing, 1) the element between −150 and −130 of integrin α1 promoter, and 2) the GATA2 and NBRE sites in the promoters of TSHβp and Enolas3p that are TR3/Nur77-targeted genes, respectively (33, 34).

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as mean ± SD. Student’s t-test and ANOVA with post-hoc test for multiple comparisons were employed to determine statistical significance. P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

TR3/Nur77 differentially regulates the expression of integrins.

Previously, we reported that integrin β4 played a role in the TR3/Nur77-induced angiogenesis (29). However, it was not known whether other integrins played any roles in the TR3/Nur77-regulated angiogenesis. Therefore, we studied the TR3/Nur77-regulated expression of 12 integrins that are expressed in endothelial cells. The HUVECs that were cultured on plates coated with collagen were infected with the adenoviruses expressing Flag-fused TR3 and Lac Z as a control (16). The RNAs were isolated and subjected to Realtime RT-PCR with the specific primers of the 12 integrins. We found that, in addition to the integrin β4, TR3/Nur77 overexpression increased the mRNA levels of integrins α1, and β5, but decreased the mRNA expression of integrins β3, α2, and α4 significantly and greatly (Table 1). The expression levels of integrins α3 and β1 were partially, but significantly decreased by TR3 expression (Table 1). However, TR3/Nur77 expression did not have significant effect on the expression of integrins αv, α5, α6 and β7 mRNAs (Table 1). It is well known that, in the quiescent vessels, the main components in BM are collagen and laminin. In activated or angiogenic vessels that are found in tumors and inflammation, basement membranes undergo changes to form a “provisional” ECM that mainly consists of fibronectin and vitronectin. The expression profile of integrins in angiogenic vessels differs from that in quiescent vessels (reviewed in (35)). Hence, we further studied the expression of integrins in the HUVECs grown on fibronectin- and Lamin-coated plates. For cells grown on fibronectin, the expression levels of integrins α1, β5 and β4 were significantly increased (Table 1). The integrin α2 expression was significantly decreased (Table 1). There was no significant change in the expression levels of integrin αv, α5, α6, β1, α4 and β3 (Table 1). For cells grown on laminin, the levels of integrins α1 and αv were significantly increased (Table 1). The levels of integrins α5, β1, α2 and β3 were significantly decreased (Table 1). There was no significant change in the expression levels of integrins β5, β4, α6 and α4 (Table 1). Similarly, TR3/Nur77 differentially regulated the expression of the integrins in HDMVECs grown on various matrixes (Table 2). On collagen, integrins α5, α3, α2 and β3 were significantly decreased (Table 2). Integrin β4 was partially increased (Table 2). On fibronectin, integrins α1 and β5 were greatly and significantly increased (Table 2). Integrins β4 and β3 were decreased partially and greatly, respectively (Table 2). On laminin, integrins α6, α2 and β3 were significantly decreased (Table 2). Because integrins α1 and β5 were most upregulated, and integrins α2 and β3 were most down-regulated, among the 12 integrins in HUVEC cultured on collagen and affected by TR3/Nur77 in several cultured condition (various cells and matrix), we chose integrins α1, β5, α2 and β3 in our current study (Fig. 1A). We further tested whether TR3 regulated the protein levels of integrins α1, β5, α2 and β3. The HUVECs grown on collagen-coated plates were infected with the viruses expressing Lac Z as a control, TR3 cDNA (TR3), and TR3 antisense (TR3-AS) that inhibited TR3 expression (16). The cellular extracts were subjected to immunoblotting with the antibodies against integrins α1, β5, α2 and β3. The protein levels of integrins α1, β5, and of integrins α2 and β3, were significantly upregulated or down-regulated by the TR3/Nur77 overexpression, respectively (Fig. 1B). The infection with the viruses expressing TR3 antisense decreased the expression of integrins α1 and β5, but increased the expression of integrins α2 and β3 (Fig. 1B). Previously, we reported that TR3/Nur77 was a down-stream target of VEGF and histamine (17). We further studied whether TR3/Nur77 was correlated with VEGF and histamine in the regulation of the integrin expression. The serum-starved HUVECs were stimulated with or without VEGF and histamine. VEGF and histamine increased the expression of integrins α1 and β5, but decreased the expression of integrins α2 and β3 (Fig. 1C and D). These data indicated that TR3/Nur77 differentially regulated the expression of integrins α1, β5, α2 and β3, and the regulation was correlated with that by VEGF and histamine.

Table 1.

TR3/Nur77 regulated the RNA expression of integrins in HUVEC cultured on various kinds of matrix.

| Matrix | Collagen | Fibronectin | Laminin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold | SD | p | Fold | SD | p | Fold | SD | p | |

| ITGA1 | 5.32 | 0.27 | ** | 5.89 | 0.07 | *** | 6.93 | 0.30 | ** |

| ITGB5 | 2.06 | 0.04 | ** | 2.21 | 0.04 | ** | 0.90 | 0.03 | NS |

| ITGB4 | 1.40 | 0.08 | * | 1.72 | 0.02 | * | 1.24 | 0.01 | NS |

| ITGAv | 1.06 | 0.01 | NS | 1.65 | 0.07 | NS | 1.60 | 0.03 | * |

| ITGA5 | 1.02 | 0.01 | NS | 1.19 | 0.05 | NS | 0.51 | 0.01 | * |

| ITGA6 | 0.88 | 0.01 | NS | 1.12 | 0.07 | NS | 1.05 | 0.05 | NS |

| ITGB1 | 0.76 | 0.01 | ** | 1.00 | 0.02 | NS | 0.72 | 0.00 | *** |

| ITGA3 | 0.73 | 0.00 | ** | ||||||

| ITGB7 | 0.71 | 0.04 | NS | ||||||

| ITGA4 | 0.57 | 0.05 | * | 1.75 | 0.17 | NS | 0.69 | 0.09 | NS |

| ITGA2 | 0.54 | 0.04 | * | 0.78 | 0.02 | * | 0.43 | 0.02 | ** |

| ITGB3 | 0.40 | 0.00 | ** | 0.87 | 0.03 | NS | 0.35 | 0.01 | *** |

SD, standard deviation.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

NS, no significant change

Table 2.

TR3 regulated the RNA expression of integrins in HMDVEC cultured on various kinds of matrix.

| Matrix | Collagen | Fibronectin | Laminin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold | SD | p | Fold | SD | p | Fold | SD | p | |

| ITGA1 | 0.98 | 0.03 | NS | 2.15 | 0.08 | ** | 1.30 | 0.08 | NS |

| ITGB5 | 1.05 | 0.08 | NS | 1.35 | 0.04 | * | 0.96 | 0.09 | NS |

| ITGB4 | 1.42 | 0.03 | NS | 0.91 | 0.00 | ** | 0.82 | 0.01 | NS |

| ITGAv | 1.39 | 0.12 | NS | 0.80 | 0.07 | NS | 1.07 | 0.05 | NS |

| ITGA5 | 0.52 | 0.00 | ** | 1.23 | 0.03 | NS | 0.41 | 0.00 | NS |

| ITGA6 | 1.06 | 0.40 | NS | 1.11 | 0.02 | NS | 0.50 | 0.03 | ** |

| ITGB1 | 1.28 | 0.05 | NS | 1.01 | 0.10 | NS | 0.76 | 0.02 | NS |

| ITGA3 | 0.50 | 0.02 | ** | ||||||

| ITGB7 | 1.34 | 0.01 | * | ||||||

| ITGA4 | 0.82 | 0.24 | NS | 0.86 | 0.05 | NS | 0.95 | 0.01 | NS |

| ITGA2 | 0.66 | 0.03 | ** | 0.93 | 0.03 | NS | 0.45 | 0.02 | * |

| ITGB3 | 0.48 | 0.02 | ** | 0.70 | 0.00 | *** | 0.40 | 0.07 | * |

SD, standard deviation.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

NS, no significant change

Figure 1. TR3/Nur77 differentially regulated the expression of integrins.

A. RNA isolated from the HUVECs that were transduced Lac Z as a control, and TR3/Nur77 were analyzed by Realtime RT-PCR with specific primers as indicated (n=4, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Data represent 3 independent experiments. B-D. Proteins isolated from the HUVECs that were transduced with Lac Z as a control, TR3 cDNA (TR3) or TR3 antisense DNA (TR3-AS) (B), stimulated with or without VEGF (C) or histamine (D) were analyzed by immunoblotting with the antibodies against integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5. Data represent 3 independent experiments. Gel densities were measured and plotted (n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, NS: no significance).

Integrins α1, α2, β3, and β5 regulated the angiogenic responses induced by TR3/Nur77.

We used the loss-of-function assays to study whether integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5 were required for the TR3/Nur77-mediated angiogenesis. For integrins α1 and β5 that were up-regulated by TR3/Nur77, their shRNAs were designed and used to knock down their expressions. For integrins α2 and β3 that were down-regulated by TR3, their full-length cDNAs were cloned and over-expressed to prevent their down-regulations. The HUVECs expressing Flag-TR3 were transduced with 1) integrin α1 shRNAs, shITGA1–1213 and shITGA1–596, 2) integrin β5 shRNA, shITGB5, 3) shGFP as a control, 4) integrin α2 and β3 cDNAs, and 5) Lac Z as a control. The cellular extracts were subjected to immunoblotting with the antibodies against Flag to confirm the equal expression of Flag-TR3, integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5 to indicate the knockdown and the overexpression of proteins, respectively (Fig. 2A). The HUVECs expressed Flag-TR3 were transduced with the adenoviruses expressing these shRNAs or cDNAs as indicated and subjected to cell proliferation, migration and adhesion assays as described in detail in the Section of Materials and Methods. The TR3/Nur77-induced cell proliferation was significantly inhibited by shITGA1–1213, shITGA1–596 and integrin α2 overexpression (Fig.2, B-I, and B-III), but increased by shITGB5 (Fig.2, B-II). The overexpression of integrin β3 had no effect on the cell proliferation mediated by TR3/Nur77 (Fig.2, B-IV). shITGB5 and the integrin α2 overexpression significantly inhibited cell migration (Fig. 2, C-II, C-III, and supplemental data Fig.S). However, shITGA1–1213, shITGA1–596 and overexpression of integrin β3 had not effect on cell migration (Fig.2, C-I, C-IV, and supplemental data Fig.S). The TR3/Nur77-induced cell adhesion was significantly inhibited by shITGA1–1213, shITGA1–596 and integrin α2 overexpression (Fig.2, D-I, and D-III), but increased by shITGB5 (Fig.2, D-II). The overexpression of integrin β3 had no effect on the cell adhesion mediated by TR3/Nur77 (Fig.2, D-IV). These data demonstrated that integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5 differentially mediated the cell proliferation, migration and adhesion induced by TR3/Nur77.

Figure 2. Effect of integrins on the angiogenic responses induced by TR3/Nur77.

The HUVECs expressing TR3/Nur77 were transduced with shGFP as a control, shITGA1–1213 and shITGA1–596 (Panel I), shGFP as a control and shITGB5 (panel II), Lac Z as a control and ITGA2 (panel III), and Lac Z as a control and ITGB3 (panel IV). Cellular extracts were subjected to immunoblotting analysis with the antibodies as indicated, and a Flag antibody indicating the equal expression of TR3/Nur77. Data represent 3 independent experiments. Gel densities were measured and plotted (A). Cells were subjected to proliferation assay (B), migration assay (C) and adhesion assay (D). Data represent 3 independent experiments (n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, NS: no significance).

Integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5 regulated the expression and activation of the signaling molecules induced by TR3/Nur77.

Previously, we reported that TR3/Nur77 inhibited the expression and phosphorylation of Akt, but increased the phosphorylation of MAPK4/44 without affecting the total MAPK42/44 level (29). We tested whether integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5 influenced the TR3/Nur77 effects. HUVECs were transduced with the adenoviruses expressing TR3/Nur77, together with one of the adenoviruses expressing shITGA1–1213, shITGA1–596, shITGB5, the cDNAs of integrin α2 and integrin β3. The cellular extracts were subjected to immunoblotting with the antibodies against phosphorylated AKT, AKT, phosphorylated MAPK42/44 and MAPK42/44. shITGA1–1213 and shITGA1–596 significantly inhibited the MAPK42/44 phosphorylation, but had no effect on AKT phosphorylation, and the expression of MAPK and MAPK42/44 (Fig. 3A). shITGB5 significantly increased AKT phosphorylation and decreased MAPK42/44 phosphorylation, but had no effect on the expression of AKT and MAPK42/44 (Fig. 3B). Overexpression of integrin α2 cDNA greatly increased MAPK42/44 phosphorylation but had no effect on AKT phosphorylation, the expression of AKT and MAPK42/44 (Fig. 3C). Overexpression of integrin β3 cDNA greatly increased AKT phosphorylation but had no effect on MAPK42/44 phosphorylation, the expression of AKT and MAPK42/44 (Fig. 3D). These data indicated that integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5 differentially mediated the expression and activation of signaling molecules induced by TR3/Nur77.

Figure 3. Effect of integrins on TR3/Nur77-activated signaling molecules.

Cellular extracts from the HUVECs expressing TR3/Nur77 that were transduced with shGFP as a control, shITGA1–1213 and shITGA1–596 (A), Lac Z as a control and shITGB5 (B), Lac Z as a control and ITGA2 cDNA (C), Lac Z as a control and ITGB3(D) were subjected to immunoblotting analysis with the antibodies as indicated. Data represent 3 independent experiments. Gel densities were measured and plotted (n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, NS: no significance).

Various TR3/Nur77 domains were required for its regulation of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5.

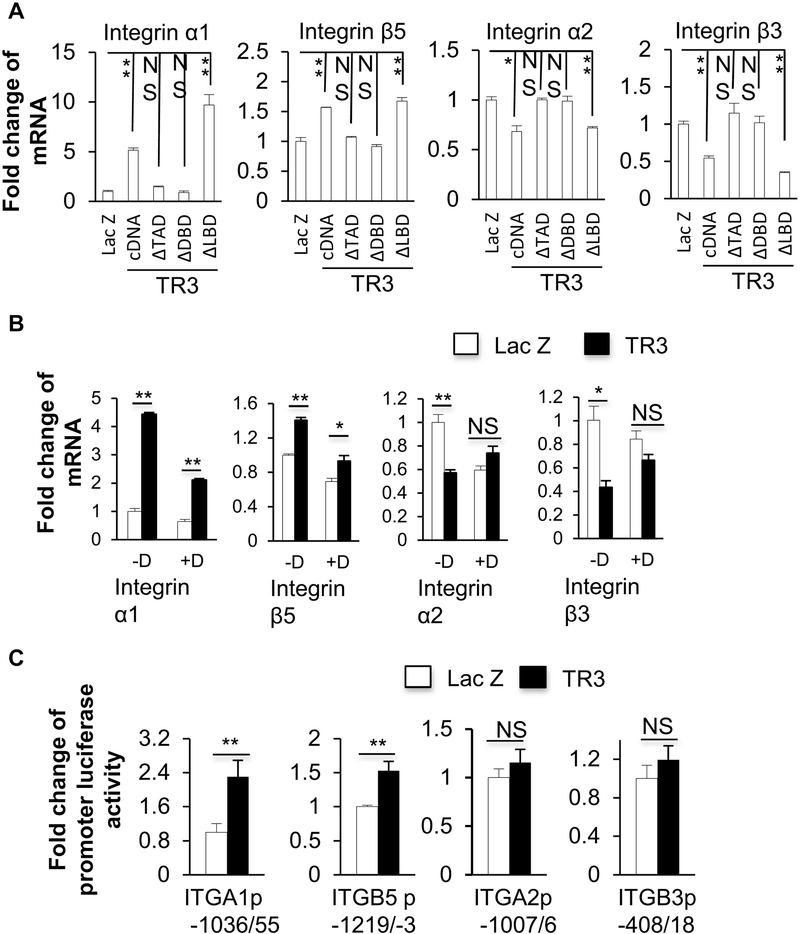

Previously, we reported that the transactivation domain and the DNA binding domain, but not the ligand-binding domain, of TR3/Nur77, were required for the function of TR3/Nur77 in angiogenesis ((15–17, 32) and Fig.4A). We studied which TR3/Nur77 domain(s) played a role in its regulation of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5. We found that both of the TR3ΔTAD and the TR3ΔDBD, in which the transactivation domain and the DNA-binding domain of TR3 were deleted, respectively, were unable to up-regulate the expression of integrins α1 and β5 or down-regulate the expression of integrins α2 and β3, but TR3ΔLBD (deletion mutant of ligand-binding domain) had the similar effect as TR3/Nur77 on regulating the expression of integrins (Fig. 4B). Our data indicated that the transactivation domain and the DNA binding domain, but not the ligand-binding domain, of TR3/Nur77 were required for its regulation of the expression of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5. We also generated serial deletions, TR3Δ1–20, TR3Δ21–40, TR3Δ41–60, TR3Δ61–80 and TR3Δ101–120, in which, the protein sequences of 1–20, 21–40, 41–60, 61–80 and 101–120 within the transactivation domain of TR3/Nur77 were deleted, respectively ((32) and Fig.4C). HUVECs were transduced with the adenoviruses expressing Flag-fused Lac Z as a control, TR3 cDNA, TR3Δ1–20, TR3Δ21–40, TR3Δ41–60, TR3Δ61–80 and TR3Δ101–120, respectively. The cellular extracts were subjected to Immunoblotting analysis with an antibody against Flag to confirm the equal expression of the various mutants, and then with the antibodies against integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5. Integrin α1 could not be up-regulated by TR3Δ101–120. Integrin β5 could not be up-regulated by TR3Δ41–60 and TR3Δ101–120. Integrin α2 could not be down-regulated by TR3Δ2140. Integrin β3 could not be down-regulated by TR3Δ41–60 (Fig.4D). Within the DNA binding domain, we generated the point mutants of TR3(S350A), TR3(S350D) and the deletion mutant TR3ΔGRR (32). The cellular extracts from the HUVECs that were transduced with Flag-fused Lac Z as a control, TR3(S350A), TR3(S350D) and TR3ΔGRR were subjected to immunoblotting analysis with the antibodies against Flag to confirm the equal expression of the various mutants, and integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5. TR3ΔGRR was unable to up-regulate the expression of integrins α1 and β5. TR3(S350D) and TR3ΔGRR were unable to down-regulate the expression of integrins α2 and β3 (Fig. E). These data showed that various amino acid fragments within the transactivation domain and the DNA binding domain of TR3/Nur77 were required for the TR3/Nur77-regulated expressions of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5.

Figure 4. Various TR3/Nur77 domains were required for its regulation of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5.

A. Schematic structure of TR3 and Nur77 genes and mutants constructed to lack TAD, DBD, or LBD domains. B. Cellular extracts isolated from the HUVECs that were transduced with Lac Z as a control, TR3, TR3ΔTAD, TR3ΔDBD, or TR3ΔLBD were subjected Immunoblotting analysis with the antibodies against Flag, integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5, and β-actin as a protein equal loading control. Data represent 3 independent experiments. Gel densities were measured and plotted (n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, NS: no significance). C. Schematic structure of TR3 mutants in the transactivation domain. D and E. Cellular extracts isolated from the HUVECs that were transduced with Lac Z as a control, TR3 cDNA, mutants as indicated were subjected Immunoblotting analysis with the antibodies against Flag, integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5, and β-actin as a protein equal loading control. Data represent 3 independent experiments. Gel densities were measured and plotted (n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, NS: no significance).

TR3/Nur77 regulated the transcription of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5.

HUVECs were transduced with Flag-fused Lac Z as a control, TR3cDNA, TR3ΔTAD, TR3ΔDBD and TR3ΔLBD. RNAs were isolated and subjected to Realtime RT-PCR analysis. Integrins α1 and β5 were upregulated by TR3cDNA and TR3ΔLBD, but not TR3ΔTAD and TR3ΔDBD. Integrins α2 and β3 were down-regulated by TR3cDNA and TR3ΔLBD, but not TR3ΔTAD and TR3ΔDBD (Fig. 5A). These data indicated that TR3 regulated the expression of integrins in RNA level and the transcriptional activity of TR3 was required for this regulation. Next we studied whether TR3/Nur77 regulated the transcription or mRNA stability of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5. The HUVECs expressing Lac Z as a control or TR3 were treated with or without actinomycin-D, a transcription inhibitor. The RNAs were isolated and subjected to Realtime RT-PCR. Actinomycin-D inhibited the up-regulation of integrins α1 and β5, and the down-regulation of integrins α2 and β3, induced by TR3 (Fig. 5B). These data indicated that TR3/Nur77-regulated the expression of integrins α1, β5, α2 and β3 by targeting their transcription. We further created promoter luciferase reporters by cloning the DNA fragments of integrins α1, β5, α2 and β3, which were upstream of their respective transcription starting sites, as described in detail in the Section of Materials and Methods. These reporters were transfected together with an internal reporter control plasmid to the HUVECs that were transduced with TR3 or Lac Z as a control. Luciferase activities were assayed and normalized to the internal control luciferase activity. The expression of TR3 increased the promoter activity of integrins α1 and β5, but had no effect on the cloned promoter activity of integrins α2 and β3 (Fig. 5C). These data clearly indicated that the TR3-regulated elements were found in the cloned integrin α1 and β5 promoters, but not in the cloned integrin α2 and β3 promoters.

Figure 5. TR3/Nur77 regulated the transcriptions of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5.

A. RNA isolated from the HUVECs that were transduced with Lac Z as a control, TR3, TR3ΔTAD, TR3ΔDBD, or TR3ΔLBD were subjected to Realtime RT-PCR with the specific primers of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5. B. The HUVECs that were transduced with Lac Z as a control, and TR3/Nur77 were treated with or without actinomycin-D. RNA were isolated and subjected to Realtime RT-PCR with specific primers of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5. C. HUVECs were transduced with promoter luciferase constructs as indicated, and then infected with Lac Z and TR3/Nur77 for the luciferase assay (n=4, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, NS: no significance). Data represent of 3 independent experiments.

TR3/Nur77 regulated integrin α1 promoter activity by directly interacting with a novel DNA element in the integrin α1 promoter.

We generated the serial deletion mutants of the integrin α1 promoter, −410/55, −310/55 and −205/55, containing the promoter regions of −410 bp, −310 bp and −205 bp in the integrin α1 promoter. The luciferase activities of all of the promoter deletion constructs, similar to that of pGL3IGTA1p(−1036/55), were increased almost two-fold in the HUVECs transduced with TR3 compared to that in cells transduced with Lac Z as a control (Fig.6A, top panel). Because further deletion might destroy the core promoter region, we generated nest deletion mutants, Δ−205/−170, Δ−170/−135, Δ−135/−105, in which the fragments between −205 bp and −170 bp, −170 bp and −135 bp, and −135 bp and −105 bp were deleted from the pGL3IGTA1p(−410/55) construct. The luciferase activity of the Δ−205/−170 was almost twofold higher in the TR3-expressed cells than that of Lac Z-expressed cells, but the luciferase activities of the Δ−170/−135 and Δ−135/−105 mutants were not significantly different in the HUVECs expressing TR3 from that in the cells expression Lac Z as a control (Fig.6A, middle panel). We further generated the nest deletion mutants between −170 bp and −105 bp region. While the luciferase activities were significantly increased in that mutants of Δ−170/−160 and Δ−160/−150, there was no difference in the luciferase activities of the mutants of Δ−150/−140, Δ−140/−130, Δ−130/−117 and Δ−117/−105, in the HUVECs transduced with TR3 compared to that in cells transduced with Lac Z as a control (Fig.6A, bottom panel). However, the basal promoter activities of the mutants Δ−130/−117 and Δ−117/−105 in Lac Z transduced cells were very low, suggesting that this region contained the transcriptional basic core promoter. Therefore, a DNA element between −150 and −130 in integrin α1 promoter was required for TR3 regulation.

Figure 6. TR3/Nur77 regulated integrin α1 promoter activity by directly interacting with a novel DNA element in the integrin α1 promoter.

A. The relative luciferase activities of integrin α1 promoter mutants in the HUVECs transduced with Lac Z as a control and TR3/Nur77 (n=4, *p < 0.05, NS: no significance). B. CHIP samples as indicated were subjected to immunoblotting with a TR3/Nur77 antibody (panel I), and to PCR with primers of integrin α1 (panel II), TSHβp (panel III) and endolas3p (panel IV). Data represent of 3 independent experiments.

We further studied whether TR3 directly interacted with the DNA element containing the region between −150 and −130 of integrin α1 promoter by CHIP assay that was carried out following the standard protocol. Briefly, after sonication, a small portion of the sample was saved as the input. The remaining of the samples were immunoprecipitated with a TR3 antibody or IgG as a control. After extensively washed, half of the immunoprecipitated samples were eluted with SDS-sample buffer for immunoblotting analysis and the other half were used to recover the DNA for PCR. The SDS-eluted protein-DNA samples were resolved in a 7% SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted with a TR3 antibody to detect TR3 in the immunoprecipitated complex. TR3 protein was clearly detected in the input sample and in the immunoprecipitated complex with a TR3 antibody, but not in the immunoprecipitated samples with IgG as a control (Fig.6B, panel I). The recovered DNA was subjected to PCR with the primers amplifying the regions containing 1) the element between −150 bp and −130 bp of integrin α1 promoter, and 2) the TR3/Nur77-targeting GATA2 and NBRE sites in the promoters of TSHβp and Enolas3p, respectively (33, 34). The PCR products were readily detected in the input sample and in the CHIP sample with a TR3 antibody, but not detected in the CHIP sample with IgG as a control (Fig.6B, panels II, III, and IV). These data clearly indicated that TR3 directly interacted with the DNA element between −150 bp and −130 bp of integrin α1 promoter.

Discussion

Pathological angiogenesis is a hallmark of many diseases. Previously, we reported that TR3/Nur77 was a critical mediator of angiogenesis to regulate tumor growth and skin wound healing. In normal adult vessels, vascular integrity is maintained by endothelial cell-endothelial cell junctions and endothelial cell-basement interactions. In order to induce angiogenesis, both of these interactions must be modified to facilitate endothelial cell proliferation and migration. We already reported that TR3/Nur77 destabilized endothelial cell-endothelial cell junctions to induce microvessel permeability and angiogenesis (17). In quiescent vessels, the main components in basement membrane are laminin and collagen. In activated/angiogenic vessels found in tumors and inflammation, basement membrane undergoes changes to form a “provisional” ECM that mainly consists of fibronectin and vitronectin. The expression profile of integrins in angiogenic vessels differs from that in quiescent vessels (reviewed in (35)). Further, integrins are known to play important roles in angiogenesis. We reported that integrin β4 was up-regulated by TR3/Nur77 (29). Here, we studied the expression profile of integrins regulated by TR3/Nur77 in endothelial cells and confirmed the upregulation of integrin β4 by TR3/Nur77 with different cells and various matrixes, on which cells were cultured. Further, TR3/Nur77 highly increased the expression of integrins α1 and β5, decreased the expression of integrins α2 and β3, but had some or no effect on the expression of integrins αv, α3, α4, α5, α6, β1 and β7. These data indicated that TR3/Nur77 differentially regulated the expression of integrins. Further, the regulations of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5 by TR3/Nur77 correlated very well with that by VEGF and histamine. These data furthered our findings that TR3/Nur77 was a down-stream target of VEGF and histamine in angiogenesis (15).

Previously, we reported that integrin β4 mediated cell migration, but not proliferation, induced by TR3/Nur77 (29). With lost-of function assays by knocking down the expression of integrins α1 and β5, and overexpression of cDNAs of integrins α2 and β3 to study whether these integrins played roles in TR3/Nur77-mediated angiogenic responses, we found that integrin α1 regulated endothelial cell proliferation and adhesion, but not migration. integrin β5 shRNA inhibited cell migration, but increased proliferation and adhesion. Integrin α2 regulated all of the endothelial cell proliferation, migration and adhesion. However, integrin β3 did not play any role in endothelial cell proliferation, migration and adhesion, suggesting that integrin β3 may play other roles on TR3/Nur77, such as microvessel permeable activity.

It was reported that Akt phosphorylated TR3/Nur77 to trigger the cytosolic translocation of TR3/Nur77, resulting in loss of the TR3/Nur77 transcriptional activity (36). We found that TR3/Nur77 induced a feed-forward signal pathway by down-regulating the expression of PI3K-Akt axis (29). Here, our data indicated that knockdown of the expression of integrins β5, and prevention of the down-regulation of integrins β3 increased the phosphorylation of AKT, but had no effect on the expression of AKT. We extended our previous finding that a novel signaling pathway, TR3/Nur77 → integrin → PI3K → Akt → FAK, by which TR3/Nur77 regulated HUVEC migration (29).

It is well known that phosphorylation of MAPK plays an important role in cell proliferation. Previously, we reported that TR3/Nur77 slightly increased the phosphorylation of MAPK42/44, which was not reversed by knocking down the expression of integrin β4 (29). Our data that shRNAs of integrins α1 and β5 decreased, but integrin α2 overexpression increased, MAPK phosphorylation, correlated very well with that integrins α1, α2 and β5 regulated cell proliferation.

The cellular localization of TR3/Nur77 alters its cellular functions. When present in the nucleus, TR3/Nur77 functions as a transcription factor that regulates gene expression and promotes cell growth. In the cytosol, TR3/Nur77 is hyper-phosphorylated and does not have transcriptional activity, but associates with other proteins, such as PKC to inhibit PKC activity (37) or Bcl2 to promote cancer cell apoptosis (38). Our previous studies demonstrated that the transcriptional activity of TR3/Nur77 was required for its function in angiogenesis and downregulation of the proteins in VE-cadherin associated adherent junctions. Here, we extended our findings that the transactivation domain, or the DNA-binding domain, but not the ligand-binding domain of TR3/Nur77 were required for the up-regulation of integrins α1 and β5, and the down-regulation of integrins α2 and β3, by TR3/Nur77, at both protein and mRNA levels. Further deletion studies indicated that TR3/Nur77 regulated the expression of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5 by various amino acid fragments. The amino acid sequence 101–120 of TR3/Nur77 was required for TR3/Nur77 upregulation of integrins α1 and β5. The amino acid sequences 41–60 and 101–120 were required for TR3/Nur77 up-regulation of integrin β5. The amino acid sequences 21–40 and 41–60 of TR3/Nur77 were required for TR3/Nur77 down-regulation of integrins α2 and β3, respectively. Amino acid sequence GRR in the DNA binding domain of TR3/Nur77 was required for the regulation of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5 by TR3/Nur77. Mutation of amino acid residue Serine 350 to Aspartate was unable to down-regulate the expression of integrins α2 and β3. There data extended our previous findings that TR3/Nur77 was a common target for various angiogenic factors, such as VEGF, histamine and serotonin, and regulated various angiogenic responses by targeting several signaling pathways through its various domains (15).

Our data that actinomycin D inhibited the up-regulation of integrins α1 and β5 and the downregulation of integrins α2 and β3 induced by TR3/Nur77 indicated that TR3/Nut77 regulated these integrins at the transcriptional levels, further supporting that TR3/Nur77 regulated angiogenesis through its transcriptional activity. TR3/Nur77 directly regulated the promoter activities of integrins α1 and β5 and interacted with a novel DNA element in the integrin α1 promoter, correlating very well with the factor that TR3/Nur77 functioned as a transcription enhancer. TR3/Nur77 did not regulate the cloned integrin α2 and β3 promoters, indicating that the TR3/Nur77 regulatory elements are not located within the cloned regions of integrin α2 and β3 promoters. It is possible that 1) TR3/Nur77 directly interacts with an inhibitory element(s) outside the cloned integrin α2 and β3 promoters and function as a transcription repressor; 2) TR3/Nur77 may functions as a transcription factor to induce the expression of a transcription repressor that interacts with integrin α2 and β3 promoters, because overexpression of Nurr1, a closely related TR3/Nur77 family member, downregulated matrix metalloproteinase promoter activity through functionally inhibiting ETS1-regulated MMP promoter luciferase activity (39). We will further study the molecular mechanism, by which TR3/Nur77 transcriptionally regulates the expression of integrins.

Collectively, we demonstrated that TR3/Nur77 differentially regulated the expression of integrins in endothelial cells and that integrins played various roles in the angiogenic responses induced by TR3/Nur77. Various TR3/Nur77 domains were required for its regulation of integrins. TR3/Nur77 transcriptionally regulated the expression of integrins, and regulated the integrin α1 promoter activity by directly interacting with a novel DNA element in the integrin α1 promoter. These studies furthered our understanding of the molecular mechanism, by which TR3/Nur77 regulated angiogenesis and supported our previous finding that TR3/Nur77 was an excellent therapeutic target for pathological angiogenesis. Targeting TR3/Nur77 would inhibit several signaling pathways that were activated by various angiogenic factors. In the future, we will study the TR3/Nur77 inhibitory molecules for therapeutic application.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

TR3/Nur77 expression highly increased the expression of integrins α1 and β5, decreased the expression of integrins α2 and β3, but had some or no effect on the expression of integrins αv, α3, α4, α5, α6, β1 and β7.

Integrns α1, α2, α3 and β5 differentially regulated the angiogenic responses mediated by TR3/Nur77.

TR3/Nur77 regulated the transcription of integrins α1, α2, β3 and β5, via various amino acid fragments within its transactivation domain and DNA binding domain.

TR3/Nur77 regulated the integrin α1 promoter activity by directly interacting with a novel DNA element within the integrin α1 promoter.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by the NIH grants R01CA133235 and R03CA191463 (HZ), R01DK095873 and R21DK080970 (DZ), by the American Cancer Society grant RSG CSM 113297 (DZ), and by the Scholarships from China Scholarship Council (JP, SH, GN and YL), from Renji hospital, P.R.China (TY), and from Beijing Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Capital Medical University (XL).

Abbreviations:

- TR3/Nur77

orphan nuclear receptor TR3 (human homolog, Nur77, mouse homolog)

- VEGF

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

- VEGFR

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor

- bFGF

Basic fibroblast growth factor

- PlGF

Placental growth factor

- PDGF

Platelet-derived growth factor

- CHIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays

- EC-Nur77-S mice

transgenic mice in which the full length Nur77 is inducibly and specifically expressed in mouse endothelium

- EC

endothelial cell

- BM

basement membrane

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- ORF

open reading frame

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- EBM

endothelial basic medium

- MEM

Minimum Essential Medium

- PBS

Phosphate Buffered Saline

- OD

optical density

- TR3ΔTAD

TR3 mutant with deletion of transactivation domain

- TR3ΔDBD

TR3 mutant with deletion of DNA-binding domain

- TR3ΔLBD

TR3 mutant with deletion of ligand-binding domain

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shibuya M (2014) VEGF-VEGFR Signals in Health and Disease. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 22, 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayman SR, Leung N, Grande JP, and Garovic VD (2012) VEGF inhibition, hypertension, and renal toxicity. Curr Oncol Rep 14, 285–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bautch VL (2010) Cancer: Tumour stem cells switch sides. Nature 468, 770–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebos JM, and Kerbel RS (2011) Antiangiogenic therapy: impact on invasion, disease progression, and metastasis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8, 210–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebos JM, Lee CR, Christensen JG, Mutsaers AJ, and Kerbel RS (2007) Multiple circulating proangiogenic factors induced by sunitinib malate are tumor-independent and correlate with antitumor efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 1706917074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kienast Y, von Baumgarten L, Fuhrmann M, Klinkert WE, Goldbrunner R, Herms J, and Winkler F (2010) Real-time imaging reveals the single steps of brain metastasis formation. Nat Med 16, 116–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li JL, Sainson RC, Oon CE, Turley H, Leek R, Sheldon H, Bridges E, Shi W, Snell C, Bowden ET, Wu H, Chowdhury PS, Russell AJ, Montgomery CP, Poulsom R, and Harris AL (2011) DLL4-Notch signaling mediates tumor resistance to anti-VEGF therapy in vivo. Cancer Res 71, 6073–6083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loges S, Schmidt T, and Carmeliet P (2010) Mechanisms of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy and development of third-generation anti-angiogenic drug candidates. Genes Cancer 1, 12–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ricci-Vitiani L, Pallini R, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Invernici G, Cenci T, Maira G, Parati EA, Stassi G, Larocca LM, and De Maria R (2010) Tumour vascularization via endothelial differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Nature 468, 824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shojaei F (2012) Anti-angiogenesis therapy in cancer: current challenges and future perspectives. Cancer Lett 320, 130–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shojaei F, Wu X, Qu X, Kowanetz M, Yu L, Tan M, Meng YG, and Ferrara N (2009) G-CSF-initiated myeloid cell mobilization and angiogenesis mediate tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF therapy in mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 6742–6747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang R, Chadalavada K, Wilshire J, Kowalik U, Hovinga KE, Geber A, Fligelman B, Leversha M, Brennan C, and Tabar V (2010) Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature 468, 829–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helfrich I, Scheffrahn I, Bartling S, Weis J, von Felbert V, Middleton M, Kato M, Ergun S, Augustin HG, and Schadendorf D (2010) Resistance to antiangiogenic therapy is directed by vascular phenotype, vessel stabilization, and maturation in malignant melanoma. J Exp Med 207, 491–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shojaei F, Wu X, Malik AK, Zhong C, Baldwin ME, Schanz S, Fuh G, Gerber HP, and Ferrara N (2007) Tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment is mediated by CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells. Nat Biotechnol 25, 911–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin L, Zhao D, Xu J, Ren X, Terwilliger EF, Parangi S, Lawler J, Dvorak HF, and Zeng H (2013) The vascular permeabilizing factors histamine and serotonin induce angiogenesis through TR3/Nur77 and subsequently truncate it through thrombospondin-1. Blood 121, 2154–2164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng H, Qin L, Zhao D, Tan X, Manseau EJ, Van Hoang M, Senger DR, Brown LF, Nagy JA, and Dvorak HF (2006) Orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 regulates VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis through its transcriptional activity. J Exp Med 203, 719–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao D, Qin L, Bourbon PM, James L, Dvorak HF, and Zeng H (2011) Orphan nuclear transcription factor TR3/Nur77 regulates microvessel permeability by targeting endothelial nitric oxide synthase and destabilizing endothelial junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 12066–12071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flaig R, Greschik H, Peluso-Iltis C, and Moras D (2005) Structural basis for the cellspecific activities of the NGFI-B and the Nurr1 ligand-binding domain. J Biol Chem 280, 19250–19258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho SD, Lee SO, Chintharlapalli S, Abdelrahim M, Khan S, Yoon K, Kamat AM, and Safe S (2010) Activation of nerve growth factor-induced B alpha by methylene-substituted diindolylmethanes in bladder cancer cells induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth. Mol Pharmacol 77, 396–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhan Y, Du X, Chen H, Liu J, Zhao B, Huang D, Li G, Xu Q, Zhang M, Weimer BC, Chen D, Cheng Z, Zhang L, Li Q, Li S, Zheng Z, Song S, Huang Y, Ye Z, Su W, Lin SC, Shen Y, and Wu Q (2008) Cytosporone B is an agonist for nuclear orphan receptor Nur77. Nat Chem Biol 4, 548–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SL, Wesselschmidt RL, Linette GP, Kanagawa O, Russell JH, and Milbrandt J (1995) Unimpaired thymic and peripheral T cell death in mice lacking the nuclear receptor NGFI-B (Nur77). Science 269, 532–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maxwell MA, Cleasby ME, Harding A, Stark A, Cooney GJ, and Muscat GE (2005) Nur77 regulates lipolysis in skeletal muscle cells. Evidence for cross-talk between the beta-adrenergic and an orphan nuclear hormone receptor pathway. J Biol Chem 280, 12573–12584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanzleiter T, Schneider T, Walter I, Bolze F, Eickhorst C, Heldmaier G, Klaus S, and Klingenspor M (2005) Evidence for Nr4a1 as a cold-induced effector of brown fat thermogenesis. Physiol Genomics 24, 37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu HC, Zhou T, and Mountz JD (2004) Nur77 family of nuclear hormone receptors. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 3, 413–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campos-Melo D, Galleguillos D, Sanchez N, Gysling K, and Andres ME (2013) Nur transcription factors in stress and addiction. Front Mol Neurosci 6, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMorrow JP, and Murphy EP (2011) Inflammation: a role for NR4A orphan nuclear receptors? Biochem Soc Trans 39, 688–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohan HM, Aherne CM, Rogers AC, Baird AW, Winter DC, and Murphy EP (2012) Molecular pathways: the role of NR4A orphan nuclear receptors in cancer. Clin Cancer Res 18, 3223–3228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearen MA, and Muscat GE (2010) Minireview: Nuclear hormone receptor 4A signaling: implications for metabolic disease. Mol Endocrinol 24, 1891–1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niu G, Ye T, Qin L, Bourbon PM, Chang C, Zhao S, Li Y, Zhou L, Cui P, Rabinovitz I, Mercurio AM, Zhao D, and Zeng H (2015) Orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 improves wound healing by upregulating the expression of integrin beta4. FASEB J 29, 131–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao D, Keates AC, Kuhnt-Moore S, Moyer MP, Kelly CP, and Pothoulakis C (2001) Signal transduction pathways mediating neurotensin-stimulated interleukin-8 expression in human colonocytes. J Biol Chem 26, 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng H, Zhao D, Yang S, Datta K, and Mukhopadhyay D (2003) Heterotrimeric Gq/11 proteins function upstream of KDR (VEGF receptor 2) phosphorylation in VPF/VEGF signaling. J Biol Chem 278, 20738–20745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Bourbon PM, Grant MA, Peng J, Ye T, Zhao D, and Zeng H (2015) Requirement of novel amino acid fragments of orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 for its functions in angiogenesis. Oncotarget 6, 24261–24276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurakula K, van der Wal E, Geerts D, van Tiel CM, and de Vries CJ (2011) FHL2 protein is a novel co-repressor of nuclear receptor Nur77. J Biol Chem 286, 44336–44343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakajima Y, Yamada M, Taguchi R, Shibusawa N, Ozawa A, Tomaru T, Hashimoto K, Saito T, Tsuchiya T, Okada S, Satoh T, and Mori M (2012) NR4A1 (Nur77) mediates thyrotropin-releasing hormone-induced stimulation of transcription of the thyrotropin beta gene: analysis of TRH knockout mice. PLoS One 7, e40437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stupack DG, and Cheresh DA (2004) Integrins and angiogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol 64, 207–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen HZ, Zhao BX, Zhao WX, Li L, Zhang B, and Wu Q (2008) Akt phosphorylates the TR3 orphan receptor and blocks its targeting to the mitochondria. Carcinogenesis [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim H, Kim BY, Soh JW, Cho EJ, Liu JO, and Youn HD (2006) A novel function of Nur77: physical and functional association with protein kinase C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 348, 950–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wingate AD, and Arthur JS (2006) Post-translational control of Nur77. Biochem Soc Trans 34, 1107–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mix KS, Attur MG, Al-Mussawir H, Abramson SB, Brinckerhoff CE, and Murphy EP (2007) Transcriptional repression of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression by the orphan nuclear receptor NURR1 in cartilage. J Biol Chem 282, 9492–9504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.