Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) has undergone significant empirical inquiry in the past decade, and the relationship between emotion regulation deficits and NSSI is well established (Pisani, Wyman, Petrova, Schmeelk-Cone, Goldston et al., 2013). While NSSI is recognized as being distinct from self-inflicted harm with suicidal intent (Brausch & Gutierrez, 2010), many studies have documented the strong relationship between NSSI and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. For example, lifetime history of NSSI has been shown to strongly associate with lifetime history of suicide ideation and attempts in cross-sectional studies (Klonsky, May, & Glenn, 2013), and has also been shown to prospectively predict suicide ideation and behavior in longitudinal studies (Guan, Fox, & Prinstein, 2012). The relationship between emotion regulation deficits and suicide ideation and behavior is less understood, but recent studies indicate a moderate association (Anestis, Pennings, Lavender, Tull, & Gratz, 2013). The current study aimed to examine emotion regulation deficits as prospective predictors of suicide ideation at a 6-month follow-up as moderated by the presence or absence of NSSI behavior in an unselected community sample of adolescents. Identifying an interaction between emotion regulation deficits and NSSI in predicting suicide ideation could help to better identify youth at risk for suicide ideation and attempts. Youth with poor emotion regulation skills may not be at risk for suicide ideation if they have no other history of self-injury; however, if they do engage in NSSI, it could increase risk for future suicide ideation and behavior. Identifying emotion regulation deficits early on may be crucial in prevention of all self-harm behavior.

Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicide Risk in Adolescents

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the intentional destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent, most commonly through cutting or burning of the skin. Prevalence rates of lifetime NSSI have averaged 20% in community samples of adolescents (Muehlenkamp, Peat, Claes, & Smits, 2012). The typical age of onset for NSSI is in the early adolescent years (13-14) and NSSI is slightly more prevalent among girls than boys, although this effect size is small (Bresin & Schoenleber, 2015). Decades of research on NSSI show it to be a transdiagnostic behavior that is prominent in individuals with emotional disorders (Bentley, Cassiello-Robbins, Vittorio, Sauer-Zavala, & Barlow, 2015). NSSI is an established risk factor for suicide ideation among various adolescent samples, whether studied with cross-sectional or longitudinal designs (e.g., Andover & Gibb, 2010; Guan et al., 2012; Ribeiro et al., 2016). Additionally, NSSI has been identified as a particularly robust risk factor for suicide among clinical and community adolescents, showing up to 2-fold increase in future suicide risk (Ribeiro et al., 2016; Franklin et al., 2017). It has been postulated that NSSI is “double trouble” as it represents a risk factor for both suicide ideation and behaviors (Klonsky, Victor, & Saffer, 2014, p. 567). NSSI is strongly associated with psychological distress, whether it be interpersonal or emotional, which has been shown to associate with suicide ideation (Klonsky, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2003). NSSI has commonly been framed as contributing to acquired capability within the context of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS; Joiner, 2005), which posits that individuals must have both desire for suicide and capability for suicide in order to make a potentially lethal attempt. However, recent studies indicate that NSSI is associated with constructs related to both suicide desire and capability (Assavedo & Anestis, 2016). These studies underscore the potent risk that NSSI confers for both suicide ideation and behaviors.

Adolescence is also a time period that sees an increase in suicidal ideation and attempts. Suicide was the third leading cause of death in 15-24 year-olds for at least two decades, until it became the second leading cause of death in 2011 and has remained as such (Drapeau & McIntosh, 2017). Results from the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance in the United States found that 8% of adolescents reported attempting suicide in the past year, almost 17% reported seriously thinking about attempting suicide, and 13% made a plan in the past year (Kann, Kinchen, Shanklin, Flint, Kawkins et al., 2014). Moreover, research has shown that one-third of adolescents with suicide ideation will transition to making a plan and/or a suicide attempt, and 60% of those who transition to an attempt will do so in the first year after onset of suicidal thoughts (Glenn & Nock, 2014; Nock, Green, Hwang, et al., 2013). Thus, focusing on severity of suicide ideation in a non-clinical sample is still important because it is more prevalent than attempts, but can still help identify future suicide risk. Taken together, both NSSI and suicide ideation and behaviors remain a primary concern in this age group.

Emotion Regulation Deficits

In the context of NSSI behavior, it is well-documented that individuals who engage in NSSI self-report that the behavior is a form of (their dysfunctional) emotion regulation (Andover & Morris, 2014); 65-80% of adolescents from various samples report some form of emotion regulation as their main reason for NSSI (Lay-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, 2005; Lloyd-Richardson, Kelley, & Hope, 1997; Nock & Prinstein, 2004). This affect-regulation model of NSSI suggests that self-injury serves as a mechanism for relieving negative affect or emotions, and that NSSI becomes a maladaptive way to manage negative emotions (Klonsky, 2007). Endorsing emotion regulation as a motivation for NSSI is related to increased frequency of NSSI (Saraff, Trujilloo, & Pepper, 2015; Weinberg & Klonsky, 2012). In both self-report and laboratory studies, individuals report experiencing negative affect prior to self-injuring and a reduction in negative affect following self-injury (Klonsky, 2007). Moreover, the changes that occur with negative affect through engaging in self-injury may increase the likelihood that the behavior will be repeated (Klonsky, 2009).

To further conceptualize the role of emotion dysregulation in NSSI behavior, the Experiential Avoidance Model (EAM) has been proposed to explain how NSSI may serve to functionally avoid strong, negative, internal experiences for which some individuals have a low tolerance (Chapman, Gratz, & Brown, 2006). This model hypothesizes that when some individuals experience strong, negative emotions, poor emotion regulation skills prompt them to avoid these emotions, leading them to use NSSI to do. The NSSI then provides temporary relief to the negative emotions, but in the process, negatively reinforces the NSSI behavior. Not surprisingly, adults with NSSI behavior have consistently been found to report greater levels of experiential avoidance compared to those with no NSSI history (Nielsen, Sayal, & Townsend, 2016) and self-injurers who cease NSSI behavior report lower experiential avoidance than current self-injurers (Horgan & Martin, 2016). Higher levels of experiential avoidance is also associated with more recent NSSI (Nielsen et al., 2016) and higher frequency of NSSI (Howe-Martin, Murrell, & Guarnaccia, 2012; Najmi, Wegner, & Nock, 2007). However, no known studies have examined the interaction of experiential avoidance and NSSI behavior in the prospective prediction of suicide ideation, particularly in adolescents.

Interoceptive Deficits

Another skill set found to be lacking in individuals with NSSI are interoceptive skills, which are defined as the ability to notice, identify, and articulate emotional, and sometimes physiological cues within the body. These skill deficits have been largely studied within the context of eating disorders, a population is identified as having poor interoceptive skills related to both hunger and emotional cues (Pollatos, Kurz, Albrecht, Schreder, Kleemann et al., 2008). For example, in patients with bulimia nervosa, those that report more NSSI also have greater interoceptive deficits than those with little to no NSSI (Favaro & Santonastaso, 1998). Moreover, interoceptive deficits appear to characterize eating disorder patients who report nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempts, as well as indirect self-harm such as alcohol and drug abuse, hair pulling, vomiting, and laxative abuse. Within a sample of treatment-seeking women with eating disorders, interoceptive deficits were significantly associated with NSSI (Dodd, Smith, Forrest, Witte, Bodell, Bartlett, Siegfried, & Goodwin, 2017).

While there is evidence of impairment in awareness of bodily sensations and emotions in clinical samples of eating disorder patients, less is known about this relationship in community samples. One study of Canadian high school students study found significant differences in interoceptive awareness between groups of injuring and non-injuring adolescents across genders (Ross, Heath, & Toste, 2009) and that interoceptive awareness was associated with lifetime frequency of NSSI. Thus, adolescents who habitually engage in NSSI may be less skilled in identifying and labeling their emotions. The lack of awareness of both physical and emotional states has been consistently found to relate to severity, frequency, and factors associated with recovery for both NSSI and eating disorders. Interoceptive deficits have not been studied as extensively as emotion regulation deficits in the context of NSSI, even though there appears to be great overlap in these skill sets. While several studies have found links between these factors, research is lacking on how interoceptive deficits are related to NSSI in community samples of adolescents.

Emotion Regulation Deficits and Suicide

While a basic understanding of the link between NSSI and multiple emotion regulation deficits has been established, little evidence is available on the relation of emotion regulation to suicide and, moreover, results have been mixed (Anestis et al., 2013). Some research indicates zero-order correlations between suicidal behavior and emotion regulation (e.g., Zlotnick, Donaldson, Spirito, & Pearlstein, 1997), while others have not found associations (e.g., Tamas, Kovacs, Gentzler, Tepper, Gadoros et al., 2007). Few studies have examined this relationship in adolescent samples, and results have also been mixed. In a community sample, limited use of emotion regulation strategies and lack of emotional clarity increased the odds of past-year suicide attempts above and beyond effects of depression and other demographic factors (Pisani et al., 2013). In a sample of adolescent inpatients, difficulties in global emotion regulation were higher among adolescents with only NSSI history or NSSI and suicide attempt history compared to adolescents with only suicide attempt history (Preyde, Vanderkooy, Chevalier, Heintzman, Warne et al., 2014). Similarly, research on interoceptive deficits and suicide is sparse, and only one using a non-eating disorder population was identified. This study found that individuals with past suicidal thoughts and behaviors showed worse interoception that controls, and suicide attempters had worse interoception than ideators (Forrest, Smith, White, & Joiner, 2015). Research thus far on the overlap between NSSI, suicide, and emotion regulation deficits has almost exclusively focused on suicide attempts, or within eating disordered populations for ID, leaving room for discovery regarding relationships with suicide ideation within a non-clinical adolescent sample.

Rationale and Hypotheses

NSSI and suicide behaviors remain a public health concerns for adolescents especially as suicide deaths continue to increase each year, the prevalence of NSSI is consistent, and NSSI represents a significant risk factor for suicide ideation and behavior. Identifying how NSSI behavior may interact with experiential avoidance (EA) and interoceptive deficits (IR) in their association with suicide ideation will be a valuable addition to the existing literature. Emotion regulation is a well-known and oft cited function of NSSI, but its relationship with suicide ideation is largely unknown. Furthermore, specific investigations of experiential avoidance and interoceptive deficits and their associations with both NSSI and suicide ideation is lacking. The current study aims to address this gap in the literature by examining the interaction between two dimensions of emotion regulation deficits – Interoceptive Deficits (ID; lack of emotional clarity) and Experiential Avoidance (EA; psychological inflexibility; unwillingness to experience negative, internal experiences) – and recent NSSI engagement in the prediction of future suicide ideation at 6-month follow-up in an unselected community sample of adolescents. It was hypothesized that after controlling for suicide ideation at baseline, NSSI engagement would moderate the relationship between ID/EA and suicide ideation at 6-month follow-up such that when NSSI behavior was present, ID and EA would prospectively predict suicide ideation, and when NSSI behavior was absent, the relationship between ID/EA and suicide ideation would not be significant.

Method

Participants

Data were collected as part of a longitudinal study on the development of NSSI and suicidal ideation and behaviors in a community sample of adolescents. Data in the current study were taken from Times 2 and 3, when measures of emotion regulation deficits were added to the research protocol. Baseline data at Time 1 were collected from 436 adolescents – 233 7th graders and 203 9th graders. The mean age at baseline was 13.19 (SD = 1.19) with a range of 11-16, but 99.6% of participants were between the ages of 12-15. The majority of participants identified as female (52.7%) or male (46.4%) and less than 1% identified as transgendered or “other.” The majority of the sample also identified as heterosexual (88.5%), with some students identifying as gay or lesbian (0.7%), bisexual (2.1%), “not sure” (5.6%) and “decline to state” (2.4%). and In terms of racial diversity, 85.3% of the participants identified as White; 2.3% as Black, 4.7% as Multiethnic, 2.8% as Hispanic, 1.9% as Asian, 0.9% as American Indian, and 2.1% as “other.” At Time 2, 373 adolescents participated, evenly split between 7th and 9th grades, for a 6-month retention rate of 85.5%. At time 3, 367 adolescents participated, again with an even split between now 8th and 10th grades, for a 12-month retention rate of 84.2%. Demographic distribution did not change across time points, with proportions of ethnicity and gender staying similar.

Procedure

Data collection occurred at two public middle and two high schools in the south-central region of the United States at baseline, and at two six-month follow-up points. The two follow-up points are the focus of the current study. The research study was approved by administration at all school districts and the Institutional Review Board at XXXX University. Active parental consent was required and parent consent forms were sent home with all 7th grade students at two middle schools (~700 students), and all 9th grade students at two high schools (~476 students). The response rate for 7th graders was 42.7% (n=299; 257 positive consent, 42 negative) and for 9th graders was 47.5% (n=226; 221 positive consent, 5 negative). Adolescent participants with positive parent consent were also given a written assent form to complete before beginning the study. Out of 478 total positive parent consent forms returned 91.2% of adolescents participated in the study (n=436). Data collection occurred during school hours at each school, and all participants at each school completed the research study in one large group (e.g., spread out in the school cafeteria) or in individual classrooms. The Ph.D.-level researcher was present at all data collection sessions, in addition to up to four master’s level graduate students and up to 6 undergraduate research assistants. Students were informed that they may be referred to speak to a school counselor if the research team assessed their responses to indicate suicide risk.

After completing the research protocols, measures were thoroughly checked for pre-determined critical items that indicate depression or suicide risk. If a student was determined to be at risk on any of the identified measures, he or she was called out of a different class period later in the day to follow-up with a school counselor. An Intervention Record was completed by the research team for each identified student to classify them at one of three levels of severity (Low, Moderate, or High) with a recommendation for follow-up (ranging from monitor/review to immediate interview/follow-up). The completed records were left with the school counselors at each school to facilitate follow-up with the identified students. At Time 2, 5.6% were referred (n=21; 14 high school, 7 middle school) and at Time 3, 5.2% were referred (n=19; 10 high school, 9 middle school). At all schools, counselors assisted with parent consent distribution and collection, scheduling and organizing data collection sessions, and agreed to provide follow-up services to students identified as being at risk for suicide behaviors. School counselors followed established policies and procedures at their school for working with students at risk based on their determination of level of intervention needed.

Measures

Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury (ISAS; Klonsky & Glenn, 2009)

The ISAS is a self-report measure that assesses multiple features of nonsuicidal self-injury. Participants indicate lifetime frequency of all methods of NSSI, and provide details regarding characteristics pf NSSI. The ISAS also includes 39 statements about reasons why individuals engage in NSSI (which assesses 13 functions), and participants are asked to rate each reason on a 3-point scale about its relevance to them. The ISAS function scales have demonstrated good internal consistency (α=.80-.88) and test-retest reliability (α = .52-.89; Klonsky & Glenn, 2009; Glenn & Klonsky, 2011). In the current study, instructions on the ISAS for Time 2 were modified to assess NSSI behavior in the past 6 months; adolescents who reported NSSI behavior in this timeframe were coded as having NSSI present, and those without NSSI were coded as having NSSI absent.

Eating Disorder Inventory – Third Edition (EDI-3; Garner, 2004)

The EDI-3 is a 91-item self-report measure that assesses symptoms indicative of eating disorder risk and psychological domains that are conceptually relevant to eating disorders. The EDI was designed for use with individuals ages 13 and older, and can be used with clinical and nonclinical samples. The current study utilized one subscale from the EDI-3 – Interoceptive Deficits. This subscale consists of nine items that measure fear and confusion related to identifying and responding to emotional states, similar to the emotion regulation dimensions of lack of emotional clarity. EDI items are presented in a 6-point Likert format ranging from 6 (always) to 0 (never). Items are scored so that responses in the pathological direction for each item are weighted. Subscale scores are calculated by summing the weighted responses with higher scores indicating greater dysregulation and deficits. Internal consistency has been found to be high (α = .90 to .97) for diagnostic and normative groups and test retest reliability is excellent (α = .93 to .95). In the current sample, the ID subscale at Time 2 showed good reliability (α = .75).

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; Bond et al., 2011)

The AAQ-II is a revised version of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (Hayes, Strosahl, Wilson, et al., 2004) that was condensed from 9 items to 7 items. Questions are presented in a Likert format (1= Never true; 7=Always true) and assess experiential avoidance. The AAQ-II was found to measure the construct of experiential avoidance with better psychometric consistency than the original version and its validity has been established in multiple samples (Bond et al., 2011). In the current sample, internal consistency at Time 2 was excellent (α = .93).

Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire – Junior (SIQ-JR; Reynolds, 1988)

The SIQ-JR is a 15-item self-report measure of an adolescent’s suicidal ideation in the past month, designed for use with adolescents in grades 7–12. Items are rated according to a 7-point scale ranging from 6 (almost every day) to 0 (I never had this thought). Total scores range from 0 to 90 with higher scores indicating a greater intensity of suicidal ideation. The SIQ-JR has a clinical cut-off score of 31 and in the current sample, 3% of adolescents scored above this cut-off. The SIQ-JR has demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .94 to .97), and adequate concurrent and construct validity (Pinto, Whisman, & McCoy, 1997). The SIQ-JR showed excellent internal consistency at Time 3 in the current sample (α = .96)

Results

Two moderation models using the PROCESS macros for SPSS (Hayes, 2013) were used to test the presence or absence of NSSI as a moderator between ER deficits (interoceptive deficits or experiential avoidance) and suicide ideation at 6-month follow-up. Within the Time 2 sample, 17.2% of adolescents reported NSSI behavior in the past 6 months (n=66). The NSSI variable was dummy coded as being present (1) or absent (0) and entered as the moderator in both models. The Interoceptive Deficits (ID) subscale from the EDI-3 (Garner, 2004) and the AAQ-II (Ross et al., 2011) total score (EA; experiential avoidance) from Time 2 were entered as the independent variable, one in the first model and the other in the second model. Total scores from the SIQ-JR at Time 3 were entered as the outcome variable in both models, and total scores from the SIQ-JR at Time 2 were entered as covariates in both models.

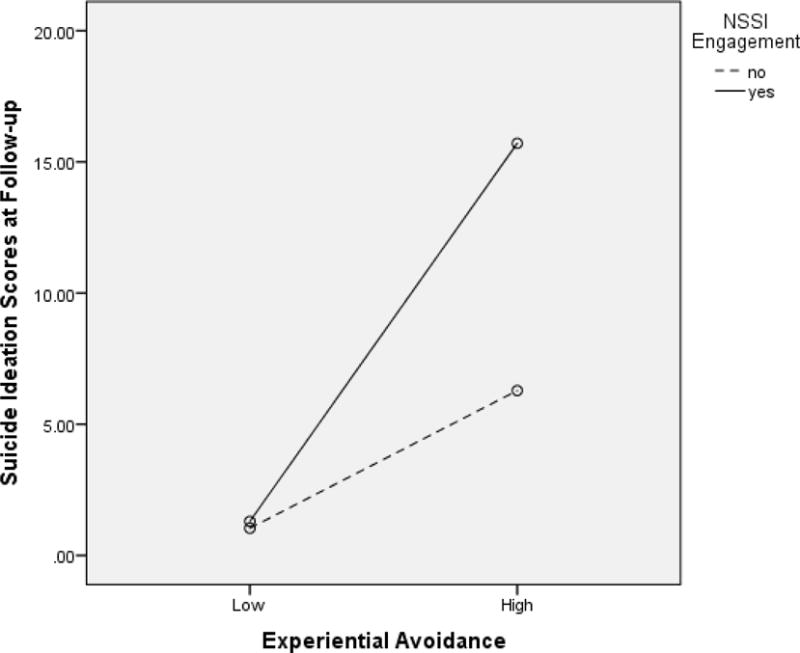

The first hypothesis expected NSSI engagement and experiential avoidance (EA) to significantly predict suicide ideation at follow-up, and for NSSI to moderate the relationship between EA and suicide ideation. The overall model was significant, F (4, 306) = 39.17, p < .01, R2 = .34. Only EA and prior suicide ideation scores were significant predictors of suicide ideation at follow-up (B=0.50 and B=0.16, respectively). The interaction effect of NSSI x Experiential Avoidance was also significant, B=0.28, 95% CI [.004, .556], t=2.00, p=.046, indicating that the relationship between EA and suicide ideation was moderated by NSSI status (see Table 1). Furthermore, examining the simple slopes showed that the relationship between EA and suicide ideation differed when NSSI was present or absent and was significant at both levels. The relationship between EA and suicide ideation was significant when NSSI was present, B=.84, 95% CI [.500, .978], t=6.09, p<.01, and when NSSI absent, B=.46, 95% CI [.282, .636], t=5.10, p<.01 (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Regression results for experiential avoidance and interoceptive deficits as moderated by NSSI engagement in the prediction of future suicide ideation

| Model | B | t | F | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 39.17** | 0.34 | ||

|

| ||||

| Suicide Ideation Baseline | 0.158 | 2.30* | ||

| Experiential Avoidance (EA) | 0.504 | 6.24** | ||

| NSSI Engagement | −0.490 | 1.77 | ||

| EA x NSSI | 0.281 | 2.00* | ||

| Model 2 | 32.09** | 0.30 | ||

| Suicide Ideation Baseline | 0.311 | 4.70** | ||

| Interoceptive Deficits (ID) | 3.45 | 3.04** | ||

| NSSI Engagement | 1.57 | 0.90 | ||

| ID x NSSI | 4.95 | 2.62** | ||

Note. The Process macros for SPSS (Hayes, 2013) reports only unstandardized coefficients.

p < .05

p < .01

Figure 1.

Interaction of Experiential Avoidance and NSSI Engagement Predicting Future Suicide Ideation

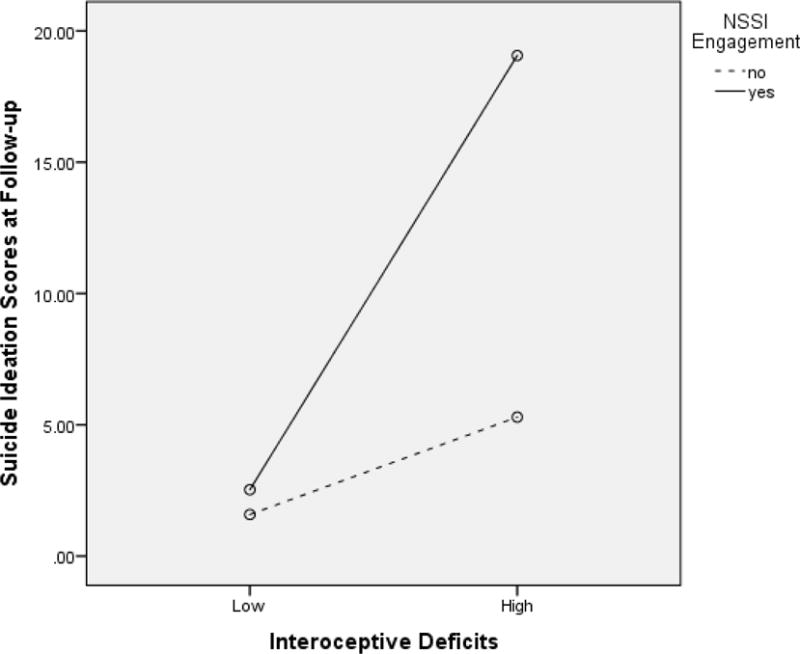

The second hypothesis expected NSSI and ID to be significant predictors of suicide ideation at follow-up and for NSSI engagement to moderate the relationship between Interoceptive Deficits and suicide ideation. The overall model was significant, F (4, 300) = 32.09, p < .01, R2 = .30. Only ID and prior suicide ideation were significant predictors of suicide ideation at follow-up (B=3.45, B=0.31, respectively). The interaction effect of NSSI x Interoceptive Deficits (ID) was also significant, B=4.95, 95% CI [1.24, 8.66], t=2.62, p<.001, indicating that the relationship between ID and suicide ideation was moderated by NSSI status (see Table 1). Additionally, examining the simple slopes showed that when adolescents had no NSSI engagement, the relationship between ID and suicide ideation was significant, B= 2.68, 95% CI [0.122, 5.23], t=2.06, p=.04. When adolescents did have NSSI engagement, the relationship between ID and suicide ideation was also significant, B=7.62, 95% CI [4.71, 10.53], t=5.16, p<.01 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interaction of Interoceptive Deficits and NSSI Engagement Predicting Future Suicide Ideation

Discussion

Given the identified relationship between NSSI and suicide ideation in adolescents, and the strong association between emotion regulation deficits and NSSI, the current study aimed to delineate the interplay between these three factors. Results from the current study indicate that the relationship between emotion regulation deficits and future suicide ideation could be impacted by an adolescent’s engagement in NSSI during the same time period. Both experiential avoidance and interoceptive deficits at a baseline time point were significantly and prospectively predictive of suicide ideation severity six months later, even after controlling for suicide ideation at baseline. Moderation analyses were also significant, and show preliminary interactions between emotion regulation deficits and NSSI behavior in the prediction of future suicide ideation. Follow-up analyses of the interactions did show that the relationship between emotion regulation deficits and suicide ideation changed depending on if NSSI behavior was also present. For example, without NSSI history, the relationship between interoceptive deficits and suicide ideation was significant, but not as pronounced as for those with NSSI history. Similar results were found for both dimensions of emotion regulation examined in this study, indicating that both experiential avoidance and interoceptive deficits could be important influences on NSSI and suicide ideation.

The finding that emotion regulation deficits being associated with suicide ideation differently with or without NSSI engagement is consistent with the overall conclusions of the few existing studies that examined similar relationships. Anestsis et al. (2013, 2014) found significant indirect relationships between several dimensions of emotion regulation and suicide attempts in three different samples of adults. In a sample of adolescent inpatients, Preyde et al. (2014) found adolescents with either NSSI only or NSSI + suicide attempts to report greater emotion regulation deficits than adolescents with only suicide attempt history (and no history of NSSI). All of these findings, when paired with the results of the current study, indicate that the interaction between emotion regulation deficits and suicide ideation and behaviors is potentially highly influenced by NSSI behavior. The current study may be the first to examine this relationship prospectively in a non-clinical sample of adolescents, and shows how future suicide ideation may be increased by experiencing NSSI and poor emotion regulation skills in the six months prior.

Within a sample of adult substance abuse disorder patients, Anestis et al. (2013) found that NSSI behavior mediated the relationship between distress tolerance and suicide attempts. Low distress tolerance was indirectly associated with lifetime suicide attempts, with NSSI frequency as the significant mediator. The current study somewhat mirrors these findings in that measures of experiential avoidance and interoceptive deficits were differentially related to current suicide ideation depending on their NSSI engagement. Both of these studies highlight the interaction of emotion regulation deficits and NSSI behavior to increase risk of suicidal thoughts and actions. If emotion regulation deficits and NSSI behavior already show risk for increased suicide ideation, risk for future suicide attempts may be increased as well, given NSSI’s potential to increase an adolescent’s capability for a suicide attempt should their ideation remain heightened or increase again in the future. On the contrary, adolescents with poor emotion regulation skills who do not use NSSI as a means to manage negative emotions may not be at increased risk for suicide ideation. Perhaps those adolescents are experimenting with other means of coping that do not impact capability for suicide to the same degree as those who use NSSI. These preliminary short-term prospective results point to potential long-term effects. Future research should focus on studying the dynamic relationship between emotion regulation deficits, NSSI behavior, and suicide ideation and behaviors as they change together over time.

Clinical Implications

The identification of individuals, particularly adolescents, most at risk for suicide ideation and attempts has been difficult historically; the large number of potential risk factors has made such predictions imprecise (U.S. Department of HHS, 2012). In addition to the obvious negative consequences of failing to recognize serious suicide risk when it is present, there may also be negative consequences in overestimating risk. Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization should be recommended sparingly and only for those at greatest imminent risk (Jobes, 2016), as it could have potential iatrogenic effects (Czyz, Berona, & King, 2016) and negatively impact future help-seeking behaviors (Michelmore & Hindley, 2012). Furthermore, individuals who present to the emergency department for treatment of self-injury wounds have reported feeling judged by medical staff (Long, Manktelow, & Tracey, 2015), which is concerning when research also shows that individuals who have negative experiences with medical or mental health professionals are less likely to seek future help when needed (Hawton, Rodham, & Evans, 2006). Therefore, it is important for clinicians to have a nuanced understanding of the risk factors for suicide and how they interact to confer higher risk. Results of the current study have significant clinical implications in that they may help to more accurately determine risk levels of youth.

Given that the combination of emotion regulation deficits and NSSI behavior in our sample was predictive of greater suicide ideation severity, it is important to monitor adolescents with poor emotion regulation skills (e.g. Perez et al., 2012). The commonly endorsed function of NSSI as an emotion regulation mechanism suggests that the deficits initially precede engagement in the behavior, which findings from a handful of studies seem to support (Andrews, Martin, Hasking, & Page, 2013; Zhang, Ren, You, Huang, Jiang, Lin, & Leung, 2017). Therefore, identification of adolescents with emotion regulation deficits could allow earlier intervention to prevent not only suicide ideation, but also NSSI. Given the other risk factors and detrimental psychological effects associated with NSSI, this is an important treatment goal on its own.

Limitations and Future Directions

When interpreting the results of the current study, several limitations must be considered. First, a single dichotomous item was used for NSSI engagement. Although some previous research with adults has used NSSI frequency rather than a dichotomous variable (e.g. Anestis et al., 2013), the current study opted to use a history variable similar to Preyde and colleagues (2014), as the use of frequency can be difficult in adolescents due to lower frequencies overall. In addition, previous research suggests that adolescents who engage in NSSI only one time significantly differ from those who never do (Whitlock, Eckenrode, & Silverman, 2006). However, future studies should consider examining these variables using NSSI frequency, possibly in clinical samples with higher frequencies. Second, this was a short-term longitudinal study with only one 6-month follow-up, and therefore the precise relationship of the variables over a longer period of time cannot be inferred. Future studies should look to using longitudinal designs with multiple follow-ups to investigate the variables in question to determine if emotion regulation deficits always precede NSSI engagement or if they might be mutually reinforcing. As previously mentioned, evidence suggests that emotion regulation deficits precede NSSI engagement at least initially (e.g., Laye-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, 2005) and that it is the combination of the two that confer increased risk, but the relationship may be more complex over time. Third, all measures were self-report, and participants were aware that endorsing items related to suicide might flag their surveys for follow-up with a school counselor, which might have had an effect on willingness to disclose NSSI and suicide ideation. The rates of both variables that were calculated are in line with previous findings, but the possibility cannot be discounted. Fourth, the majority of the sample identified as White/Caucasian and therefore the generalizability of these findings may be limited. Lastly, although we did collect data on suicidal behaviors during the follow-up period, a low base rate for suicide attempts (n=3) prevented us from being able to test hypotheses using this as an outcome variable. Future studies should aim to increase sample sizes, or target participant recruitment, in order to be able to examine the full spectrum of suicidal behavior.

Conclusions

Associations between both dimensions of emotion regulation, NSSI, and suicide ideation have been previously established in the literature, but the precise way in which these variables interact has not yet been determined. Results of the current study provide insight into the mechanisms of these relationships and have significant clinical implications for the identification of adolescents at risk for suicide behaviors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael McClay, Kandice Perry, Amanda Williams, Natalie Perkins, and Shelby Bandel for their assistance with coordination and data collection on this project.

Funding: This project was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number P20GM103436. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

DR. AMY BRAUSCH (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-7123-7633)

MS. SHERRY WOODS (Orcid ID : 0000-0002-6604-129X)

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Andover MS, Gibb BE. Non-suicidal self-injury, attempted suicide, and suicidal intent among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Research. 2010;178:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andover MS, Morris BW. Expanding and clarifying the role of emotion regulation in nonsuicidal self-injury. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;59:569–575. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews T, Martin G, Hasking P, Page A. Predictors of continuation and cessation of nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Kleiman EM, Lavender JM, Tull MT, Gratz KL. The pursuit of death versus escape from negative affect: An examination of the nature of the relationship between emotion dysregulation and both suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2014;55:1820–1830. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Pennings SM, Lavender JM, Tull MT, Gratz KL. Low distress tolerance as an indirect risk factor for suicidal behavior: Considering the explanatory role of non-suicidal self-injury. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2013;54:996–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assavedo BL, Anestis MD. The relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2016;38:251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Cassiello-Robbins CF, Vittorio L, Sauer-Zavala S, Barlow DH. The association between nonsuicidal self-injury and the emotional disorders: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;37:72–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, Waltz T, Zettlef RD. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brausch AM, Gutierrez PM. Differences in non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in adolescents. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2010;39:233–242. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresin K, Schoenleber M. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;38:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyz EW, Berona J, King CA. Rehospitalization of suicidal adolescents in relation to course of suicidal ideation and future suicide attempts. Psychiatric Services. 2016;67:332–338. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd DR, Smith AR, Forrest LN, Witte TK, Bodell L, Bartlett M, Siegfried N, Goodwin N. Interoceptive deficits, nonsuicidal self-injury, and suicide attempts among women with eating disorders. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2017 doi: 10.1111/sltb.12383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau CW, McIntosh JL, for the American Association of Suicidology . USA suicide 2015: Official final data. Washington, DC: American Association of Suicidology; 2016. dated December 23, 2016, downloaded from http://www.suicidology.org. [Google Scholar]

- Favaro A, Santonastaso P. Impulsive and compulsive self-injurious behavior in bulimia nervosa: Prevalence and psychological correlates. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186:157–165. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LN, Smith AR, White RD, Joiner TE. (Dis)connected: An examination of interoception in individuals with suicidality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;124:754–763. doi: 10.1037/abn0000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin. 2017;3:187–232. doi: 10.1037/bul0000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM. The Eating Disorder Inventory-3 Professional manual. Odessa, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. Prospective prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury: A 1-year longitudinal study in young adults. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:751–762. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Nock MK. Improving the short-term prediction of suicidal behavior. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2014;47(3 Supplement 2):S176–S180. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan K, Fox KR, Prinstein MJ. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a time-invariant predictor of adolescent suicide ideation and attempts in a diverse community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:842–849. doi: 10.1037/a0029429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E. By their own young hand: Deliberate self harm and suicidal ideas in adolescents. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG, Bissett RT, Pistorello J, Toarmino D, et al. Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan M, Martin G. Differences between current and past self-injurers: How and why do people stop? Archives of Suicide Research. 2016;20:142–152. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1004479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe-Martin LS, Murrell AR, Guarnaccia CA. Repetitive nonsuicidal self-injury as experiential avoidance among a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68:809–828. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobes DA. Managing suicidal risk; A collaborative approach. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Kawkins J, Harris WA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2013. MMWR Surveillance Summary. 2014;63(4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychological Review. 2007;27:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of self-injury in young adults who cut themselves: Clarifying the evidence for affect regulation. Psychiatry Research. 2009;166:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Glenn CR. Assessing the functions of non-suicidal self-injury: Psychometric properties of the Inventory of Statements about Self-injury (ISAS) Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009;31:215–219. doi: 10.1007/s10862-008-9107-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May AM, Glenn CR. The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: Converging evidence from four samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:231–237. doi: 10.1037/a0030278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1501–1508. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Victor SE, Saffer BY. Nonsuicidal self-injury: What we know, and what we need to know. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;59:565–568. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laye-Gindhu A, Schonert-Reichl KA. Nonsuicidal self-harm among community adolescents: Understanding the ‘Whats’ and ‘Whys’ of Self-Harm. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Richardson EE, Kelley ML, Hope T. Self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents: Descriptive characteristics and provisional prevalence rates. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Behavioral Medicine; New Orleans, LA. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Long M, Manktelow R, Tracey A. The healing journey: Help seeking for self-injury among a community population. Qualitative Health Research. 2015;25:932–944. doi: 10.1177/1049732314554092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelmore L, Hindley P. Help-seeking for suicidal thoughts and self-harm in young people: A systematic review. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2012;42:507–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Peat CM, Claes L, Smits D. Self-injury and disordered eating: Expressing emotion dysregulation through the body. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2012;42:416–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najmi S, Wegner DM, Nock MK. Thought suppression and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2007;45:1957–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen E, Sayal K, Townsend E. Functional coping dynamics and experiential avoidance in a community sample with no self-injury vs. non-suicidal self-injury only vs, those with both non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14:575. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14060575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A Functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez J, Venta A, Garnaat S, Sharp C. The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: Factor structure and association with nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent inpatients. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2012;34:393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A, Whisman MA, McCoy KJM. Suicidal ideation in adolescents: Psychometric properties of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire in a clinical sample. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pisani AR, Wyman PA, Petrova M, Schmeelk-Cone K, Goldston DB, Xia Y, Gould MS. Emotion regulation difficulties, youth-adult relationships, and suicide attempts among high school students in underserved communities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:807–820. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9884-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollatos O, Kurz AL, Albrecht J, Schreder T, Kleemann AM, Schopf V, Schandry R. Reduced perception of bodily signals in anorexia nervosa. Eating Behaviors. 2008;9:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preyde M, Vanderkooy J, Chevalier P, Heintzman J, Warne A, Barrick K. The psychosocial characteristics associated with NSSI and suicide attempt of youth admitted to an in-patient psychiatric unit. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;23:100–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, Nock MK. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46:225–236. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Heath NL, Toste JR. Non-suicidal self-injury and eating pathology in high school students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:83–92. doi: 10.1037/a0014826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraff PD, Trujilloo N, Pepper CM. Functions, consequences, and frequency of non-suicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Quarterly. 2015;86:305–393. doi: 10.1007/s11126-015-9338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamas Z, Kovacs M, Gentzler AL, Tepper P, Gadoros J, Kiss E, Vetro A. The relations of temperament and emotion self-regulation with suicidal behaviors in a clinical sample of depressed children in Hungary. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:640–652. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Washington, DC: HHS; Sep, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Klonsky ED. The effects of self-injury on acute negative arousal: A laboratory simulation. Motivation and Emotion. 2012;36:242–254. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Eckenrode J, Silverman D. Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1939–1948. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ren Y, You J, Huang C, Jiang Y, Lin M, Leung F. Distinguishing pathways from negative emotions to suicide ideation and to suicide attempt: The differential mediating effects of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10802-017-0266-9. on-line first. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Donaldson D, Spirito A, Pearlstein T. Affect regulation and suicide attempts in adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:793–798. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]