Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes, the sexual stages responsible for malaria parasite transmission, develop in the human bone marrow parenchyma in proximity to the erythroblastic islands. Yet, mechanisms underlying gametocytes interactions with these islands are unknown. Here, we have investigated whether gametocyte-infected erythrocytes (GIE) adhere to erythroid precursors, and whether a putative adhesion may be mediated by a mechanism similar to the adhesion of erythrocytes infected with P. falciparum asexual stages to uninfected erythrocytes. Cell-cell adhesion assays with human primary erythroblasts or erythroid cell lines revealed that immature GIE do not specifically adhere to erythroid precursors. To determine whether adhesion may be dependent on binding of STEVOR proteins to Glycophorin C on the surface of erythroid cells, we used clonal lines and transgenic parasites that overexpress specific STEVOR proteins known to bind to Glycophorin C in asexual stages. Our results indicate that GIE overexpressing STEVOR do not specifically adhere to erythroblasts, in agreement with our observation that the STEVOR adhesive domain is not exposed at the surface of GIE.

Introduction

The spread of malaria in population relies on the ability of the Plasmodium parasites to be transmitted from infected individuals to mosquito vectors. Understanding the biology of Plasmodium gametocytes, the only parasite stages capable of transmission to mosquitoes, is therefore crucial to ablate parasite transmission. For Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of the most severe form of human malaria, gametocytes maturation lasts about 10 days and is conventionally divided into 5 morphological stages (I–V)1. From stage I to IV, immature gametocytes are sequestered away from peripheral circulation, and appear only as mature stages V in the peripheral blood where they are accessible for mosquito bites. Analyses of ex-vivo and autopsy specimens from malaria-infected patients revealed that immature gametocytes are predominantly localized in the bone marrow parenchyma, where they are enriched at erythroblastic islands2–4. These specialized niches, where the terminal erythroid differentiation occurs, consist of a macrophage surrounded by differentiating erythroblasts5.

The unveiling of the hidden sites for gametocytes maturation raised the questions how these parasite stages develop and sequester in the bone marrow micro-environment and how they interact with the erythroblastic islands. Their presence in the bone marrow extra-vascular compartment and the absence of P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) expression in gametocytes6 suggest that gametocytes sequester via different mechanisms than those of asexual stages, which depend on cytoadhesion of infected erythrocytes to vascular endothelium through the interaction of PfEMP1 with endothelial receptors7,8. Moreover, studies of gametocyte-infected erythrocytes (GIE) cytoadhesion failed to show any binding interactions of immature GIE with human endothelial cells from different tissues, including human bone marrow-derived endothelial cell lines6,9–11. The proximity of immature GIE with erythroblastic islands suggests that GIE may adhere to erythroid precursors. A binding interaction between these cells may be mediated by a mechanism similar to the adhesion of asexual stages-infected erythrocytes to uninfected erythrocytes. This phenomenon, called “rosetting”, has been linked to disease severity12. Although rosetting has been almost exclusively observed in asexual stages, we hypothesize that a “rosetting-like” adhesion may occur between GIE and erythroid precursors. Among the different erythrocyte receptors involved in rosetting of asexual stages, Glycophorin C (GPC) is one of the key host receptors for rosetting with erythrocytes infected with both P. falciparum and P. vivax13,14. GPC interacts with parasite proteins called STEVOR (SubTElomeric Variable Open Reading frame). These proteins belong to one of the major parasite proteins family and are exposed at the infected erythrocyte surface in late trophozoite stages14–16. Interestingly, STEVOR proteins are exported to the infected erythrocyte membrane by immature gametocytes17,18, and one study has reported their presence at the surface of live GIE17. Moreover, GPC protein expression starts in the early stage of erythropoiesis19,20. Therefore, an interaction between the GPC located at the surface of erythroid precursors and STEVOR proteins exposed at the surface of immature GIE would be plausible. Based on this, we hypothesized that the adhesion of STEVORs to GPC might contribute to sequestration of immature gametocytes in the bone marrow parenchyma by promoting adhesion of immature GIE to erythroblasts. Yet, the ability of GIE to cytoadhere to erythroid cells has never been addressed, although one study suggested that GIE from P. falciparum isolates may be involved in rosette formation13. Moreover, STEVORs adhesive properties have never been investigated during sexual stages.

In the present study, we have performed cell-cell adhesion assays to investigate interactions between immature GIE and human primary erythroblasts or erythroid cell lines. To determine the contribution of STEVOR proteins to these interactions, we used clonal lines that express specific stevor genes as well as transgenic parasite lines that overexpress or down-regulate members of the stevor gene family. Our results show that GIE overexpressing STEVOR do not adhere to erythroblasts, and that STEVOR adhesive domain is not exposed at the surface of GIE.

Results

Validation of the cell-cell adhesion protocol

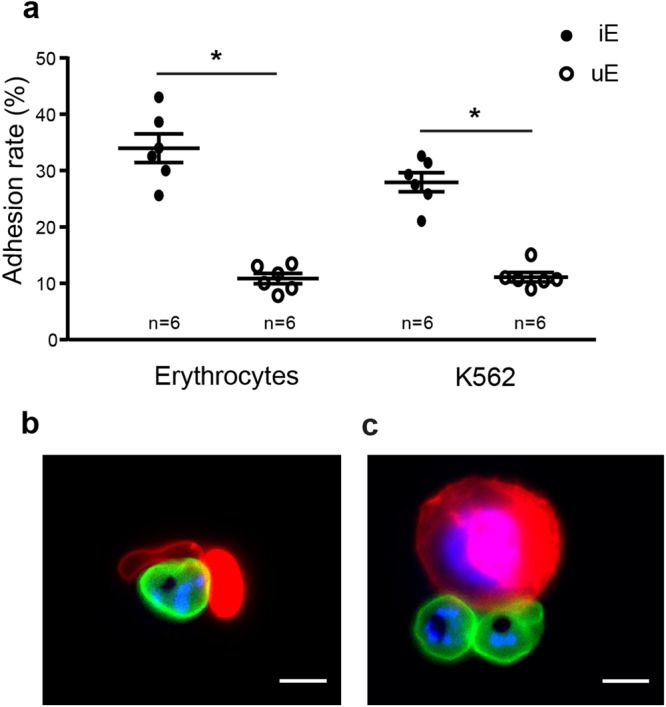

The presence of immature gametocytes near the erythroblastic islands in extravascular spaces of bone marrow suggests a direct adhesion of immature GIE to the developing erythroblasts. To test this hypothesis, we set up a cell-cell adhesion protocol with MACS-purified infected erythrocytes and erythroid cells. We first validated our protocol with the VarO parasite line known to adhere to the ABO blood group and commonly used as a model for in vitro rosetting21. With this adhesion protocol, erythrocytes infected with VarO asexual parasites significantly adhered to non-infected erythrocytes (Fig. 1a,b) and K562 erythroid cells (Fig. 1a,c), indicating that size and rigidity of nucleated erythroid cells are not a hindrance for infected erythrocyte adhesion.

Figure 1.

Validation of the cell-cell adhesion protocol. (a) Cell-cell adhesion assays of MACS-purified erythrocytes infected with asexual VarO trophozoites (iE) or uninfected erythrocytes (uE) to erythrocytes (p = 0.03) or K562 cells (p = 0.03). Error bars denote the standard error of the mean. n = number of experiments. (b,c) Live microscopy imaging showing adhesion of VarO-infected erythrocytes stained with PKH67 (green) to uninfected erythrocytes (b) or K562 cells (c) stained with PKH26 (red). DNA is stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Bars represent 5 µm.

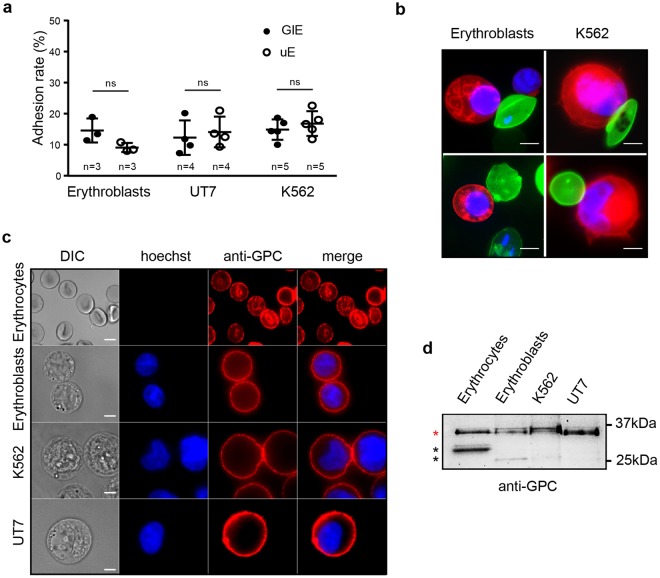

NF54 GIE fail to adhere to erythroid cells

We then used our adhesion protocol to address whether immature GIE bind to primary erythroblasts derived from CD34+ progenitor cells from human bone marrow or to the erythroid cell lines K562 and UT7 (Fig. 2a,b). As VarO parasites do not produce gametocytes, we quantified adhesion of immature GIE from the NF54 gametocyte-producing strain. We observed that adhesion rates of MACS-purified immature NF54 GIE to erythroblasts or erythroid cell lines were not significantly different from those of uninfected erythrocytes from the same culture (Fig. 2a), indicating that NF54 GIE do not specifically adhere to erythroid precursors. Since we hypothesized that GIE might adhere to erythroid cells via interaction with GPC, we performed immunostaining of non-permeabilized UT7 cells, K562 cells, erythroblasts and erythrocytes with an anti-GPC antibody to confirm that GPC is properly expressed at the surface of all types of erythroid cells (Fig. 2c). Moreover, immunoblotting analysis detected in all types of cells a major band at 32 kDa that corresponds to the expected size of fully glycosylated GPC22, suggesting that glycosylation levels are comparable in erythrocytes and erythroid precursors (Fig. 2d). These results indicate that NF54 immature GIE fail to adhere to erythroid cells expressing GPC. These findings suggest either that GIE and erythroblasts never bind together, or that adhesion is dependent on GIE protein(s) that are not expressed in the NF54 strain.

Figure 2.

NF54 GIE fail to adhere to erythroid cells. (a) Cell-cell adhesion assays of MACS-purified NF54 GIE (GIE) or uninfected erythrocytes (uE) to human primary erythroblasts, UT7 cells and K562 cells. Error bars denote the standard error of the mean. ns, non-significant differences in adhesion rates. n = number of experiments. (b) Live microscopy imaging showing non-specific adhesion of MACS-purified NF54 GIE (upper panel) and uninfected erythrocytes (lower panel) stained with PKH67 (green) to human primary erythroblasts or K562 cells stained with PKH26 (red). DNA is stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Bars represent 5 µm. (c) Immunofluorescence analysis (IFA) of paraformaldehyde-fixed uninfected erythrocytes, erythroblasts, K562 cells and UT7 cells stained with anti-GPC mAb followed by anti-mouse Alexa594-conjugated IgG, showing the presence of GPC at the surface of all erythroid cells. DNA is stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Bars represent 5 µm. (d) Western blot analysis showing the presence and the size of GPC in erythrocytes, erythroblasts, K562 cells and UT7 cells. Red star indicates the expected size of fully glycosylated GPC (32 kDa). Black stars indicate degradation products. Full-length blot is presented in Supplementary Fig. S1.

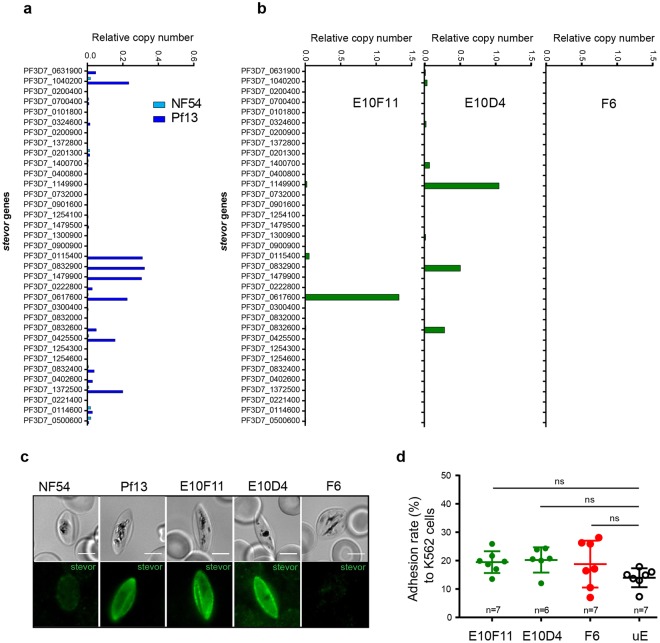

Endogenous levels of STEVOR expression do not promote GIE adhesion to erythroid cells

The absence of specific adhesion between NF54 GIE and erythroid cells may be explained by a too low expression of stevor genes in the NF54 polyclonal culture. Indeed, the expression of this multigenic family is clonally variant and undergoes switching23, therefore the low level of transcription of stevor genes in comparison with the endogenous control gene expression in NF54 trophozoites (Fig. 3a) suggests that only a proportion of the parasite population efficiently transcribes stevor genes. Moreover, the STEVOR N-terminal sequence is variable among the 35 members of the STEVOR family, and adhesive properties may not be conserved in the entire family. For instance, only a subset of PfEMP1 variants can mediate rosetting24. Since the ability to bind GPC has been addressed for just a few STEVOR members14, it is thus possible that the members expressed in NF54 GIE are not involved in adhesion. To determine which STEVOR member(s) are likely involved in rosetting, we analyzed by RT-qPCR the stevor genes transcription profile in the 3D7/Pf13 parasite line that has been enriched for a rosetting phenotype25 (Supplementary Fig. S2a). In contrast with NF54 parasites, seven stevor genes (PF3D7_1040200, PF3D7_0115400, PF3D7_0832900, PF3D7_1479900, PF3D7_0617600, PF3D7_0425500, and PF3D7_1372500) were significantly transcribed in trophozoites of this parasite line (Fig. 3a). Among them, four genes (PF3D7_1040200, PF3D7_0115400, PF3D7_0832900, and PF3D7_0617600) were selected in a published microarray analysis14 as upregulated in two parasite lines enriched for rosetting. To determine the contribution of these STEVOR members to a potential adhesion to erythroid cells, we utilized parasite clones of NF54 that were previously characterized for stevor expression23, instead of the 3D7/Pf13 line that poorly generates gametocytes (Supplementary Fig. S2b). In particular, we picked two clones which expressed one stevor detected in both our RT-qPCR analysis of the 3D7/Pf13 parasite line and the published microarray analysis, and one clone which did not express any stevor (Fig. 3b). Immunostaining of immature GIE from these clones with specific anti-STEVOR antibodies confirmed that STEVOR proteins are expressed in E10F11 and E10D4 gametocytes whereas no expression was detected in the F6 clone (Fig. 3c). However, adhesion assays did not show any difference in GIE adhesion to K562 cells between these three clones and uninfected erythrocytes (Fig. 3d). These results suggest that the STEVOR members expressed in E10F11 and E10D4 clones (PF3D7_0617600 and PF3D7_0832900) may not be the ones responsible for the rosetting phenotype in the 3D7/Pf13 line, since we cannot exclude that these proteins may not have adhesive properties. Also, endogenous expression of the selected stevor genes may not be sufficient to promote adhesion to erythroid cells. In support of this hypothesis, previous studies have reported a reduction of STEVOR expression in laboratory-adapted parasite lines compared to parasites directly isolated from patients where STEVOR may play a crucial role in host-parasite interaction26,27.

Figure 3.

Endogenous levels of STEVOR expression do not promote GIE adhesion to erythroid cells. (a,b) RT-qPCR analysis of transcriptional levels for the 35 stevor genes in trophozoites (28 hours post-infection) of NF54 and 3D7/Pf13 lines (a), and of NF54 clones E10F11, E10D4 and F6 (b). Transcription levels were normalized to the transcription level of the arginyltRNA synthetase reference gene (PF3D7_1218600). (c) IFA of permeabilized GIE showing the expression of STEVOR protein (green) in NF54, 3D7/Pf13, E10F11, E10D4 and F6 parasite lines. GIE were stained with a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against STEVOR PF3D7_0631900 protein followed by anti-rabbit Alexa488-conjugated IgG. Pictures were taken under identical exposure conditions. Bars represent 5 µm. (d) Cell-cell adhesion assays of MACS-purified GIE from NF54 clones or of uninfected erythrocytes (uE) to K562 cells. Error bars denote the standard error of the mean. ns, non-significant differences in adhesion rates. n = number of experiments.

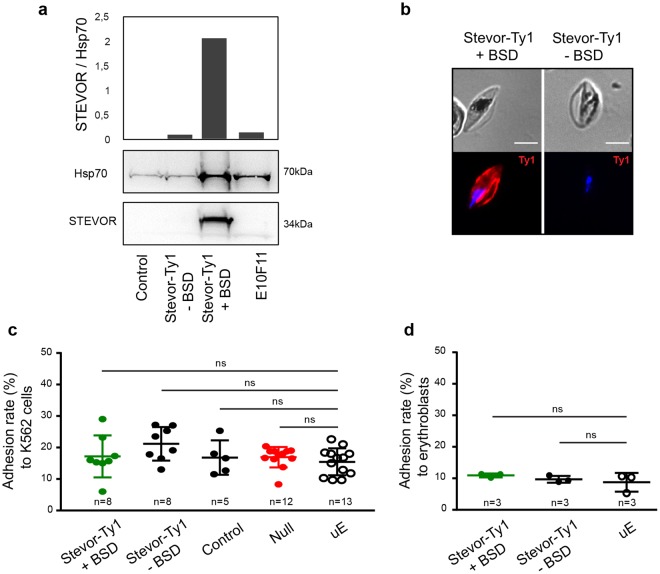

Overexpression of STEVOR does not promote GIE adhesion to erythroid cells

To rule out the hypothesis that endogenous expression of stevor genes is not sufficient to promote adhesion, we generated a transgenic parasite line (Stevor-Ty1) that episomally overexpresses a Ty1-tagged copy of stevor driven by the constitutive promotor of calmodulin. To exclude the possibility that the STEVOR members expressed in E10F11 and E10D4 clones are not functional, we opted for the overexpression of the PF3D7_1040200 stevor gene. This gene has been selected in our RT-qPCR analysis of the 3D7/Pf13 parasite line, and the PF3D7_1040200 protein has also been previously shown to mediate adhesion of asexual parasite-infected erythrocytes to GPC14. As a control, we promoted the shedding of the episome-encoded PF3D7_1040200 by cultivating the Stevor-Ty1 line for several generations without blasticidin selection (-BSD) required to retain the episome. The transgenic Control parasite line28, transfected with an empty plasmid, and the Null parasite line28 that down-regulates the entire stevor gene family, were also used as negative controls. Immunoblotting and immunostaining of immature GIEs with antibodies against STEVOR and Ty1 tag indicated that STEVOR proteins were twenty-fold more expressed in the Stevor-Ty1 transgenic line than in the E10F11 clone (Fig. 4a) and that PF3D7_1040200-Ty1 was properly exported to the infected erythrocyte membrane (Fig. 4b). However, adhesion assays did not show any significant adhesion of immature GIE from this overexpressing parasite line to K562 cells (Fig. 4c) or to primary erythroblasts (Fig. 4d) compared to the control lines and uninfected erythrocytes. Similar results were obtained with another transgenic line overexpressing the PF3D7_0631900 protein28 (Supplementary Fig. S4). These results indicate that overexpression of a STEVOR protein involved in adhesion to GPC in asexual stages does not promote adhesion of gametocyte stages to erythroid cells.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of STEVOR does not promote GIE adhesion to erythroid cells. (a) Western blot analysis of STEVOR expression in stage III GIEs from the transgenic Stevor-Ty1 line cultivated with and without BSD, the transfection control line (Control) and the NF54 clone E10F11. Immunoblots were probed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against STEVOR PF3D7_0300400 protein and with a mAb directed against PfHsp70. Quantification of STEVOR level relative to the loading control PfHsp70 was performed by densitometry (ImageJ software). Decrease of STEVOR expression in Stevor-Ty1 GIE cultivated without BSD indicates a loss of episomal expression of the epitope-tagged STEVOR protein. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S3. (b) IFA of methanol-fixed blood smears showing the expression and erythrocyte membrane localization of PF3D7_1040200 -Ty1 STEVOR protein (red) in Stevor-Ty1 GIE cultivated with and without BSD. GIE were stained with anti-Ty1 mAb followed by anti-mouse Alexa594-conjugated IgG, and parasite nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Pictures were taken under identical exposure conditions. Absence of Ty1 expression in Stevor-Ty1 GIE cultivated without BSD indicates a loss of episomal expression of the epitope-tagged STEVOR protein. Bars represent 5 µm. (c,d) Cell-cell adhesion assay of MACS-purified transgenic Stevor-Ty1 GIE cultivated with and without BSD, of transfection control GIE (Control), of a transgenic GIE downregulating STEVOR expression (Null) or of uninfected erythrocytes (uE) to K562 cells (c) or to human primary erythroblasts (d). Error bars denote the standard error of the mean. ns, non-significant differences in adhesion rates. n = number of experiments.

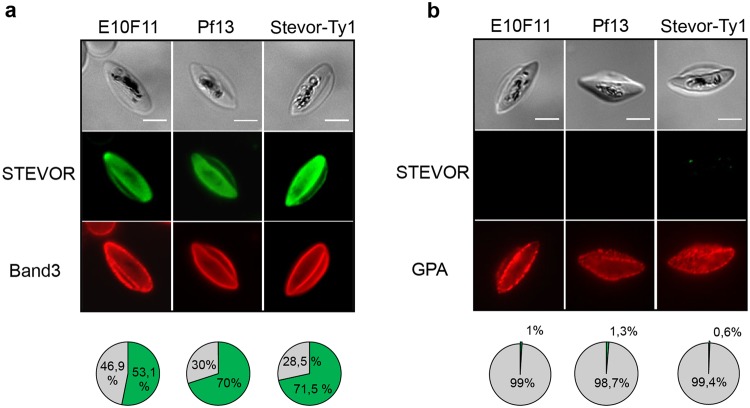

STEVOR adhesive domain is not exposed at the GIE surface

Failure of GIE to adhere to erythroid cells may be due to a different conformation of STEVOR proteins at the GIE membrane compared to asexual stages. To address whether the adhesive domain of STEVOR proteins is properly exposed at the surface of erythrocytes infected with gametocytes, we performed IFA on permeabilized and non-permeabilized immature GIE with antibodies directed against the N-terminus domain of STEVOR. This domain includes the variable domain, the first hydrophobic stretch and the semi-conserved region that promotes binding to GPC in asexual stages14. Unexpectedly, we observed that antibodies detected the STEVOR N-terminus domain in more than 53.1% of permeabilized cells (Fig. 5a) but in less than 1% of non-permeabilized cells (Fig. 5b) from the E10F11 clone, suggesting that the STEVOR adhesive domain may not be exposed at the surface of GIE. Furthermore, the few non-permeabilized cells positive for STEVOR were either recognized by antibodies directed against a cytoplasmic domain of Band 3, indicating the leakiness of the erythrocyte membrane, or were not recognized by anti-Glycophorin A antibodies, suggesting a loss of the erythrocyte membrane (Supplementary Fig. S5). Similar staining patterns were observed in GIE from the Stevor-Ty1 transgenic line and the 3D7/Pf13 parasite line, indicating that STEVOR exposure at the erythrocyte surface is not dependent on STEVOR expression level or parasite enrichment for rosetting (Fig. 5). Therefore, the missing of STEVOR adhesive domain at the erythrocyte surface likely accounts for the lack of GIE adhesion to erythroid cells.

Figure 5.

STEVOR proteins are not exposed at the GIE surface IFA of permeabilized (a) and non-permeabilized (b) immature GIE from the E10F11, 3D7/Pf13 and Stevor-Ty1 (+BSD) parasite lines. GIE were stained with a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the N-terminal domain of STEVOR PF3D7_0631900 (green) and with a mouse antibody directed against the cytoplasmic domain of Band 3 ((a), red) or with a mouse anti-Glycophorin A (GPA) (b, red). Pie charts show proportions of GIE positive (green) or negative (grey) for STEVOR staining. 300 cells per condition were examined. Band 3 and GPA staining control permeabilization and presence of the erythrocyte membrane, respectively. Pictures were taken under identical exposure conditions. Bars represent 5 µm.

Discussion

Deciphering the interactions between P. falciparum gametocytes and erythroblastic islands may provide insights into the parasite sequestration mechanisms in the bone marrow parenchyma. In the present study, we investigated whether immature GIE adhere to erythroid precursors. Our results indicated that GIE from the NF54 strain fail to adhere to erythroblasts, suggesting either that these cells never bind together, or that adhesion is dependent on protein(s) which are not expressed in the NF54 strain, as for proteins encoded by multigenic families. In support to this latter hypothesis, other adhesion phenotypes in P. falciparum are often mediated by antigenically variant proteins, such as PfEMP1 proteins that promote adhesion to endothelial cells or RIFIN (Repetitive Interspersed Family) and STEVOR proteins that are involved in asexual stages rosetting29. Therefore, we have investigated whether GIE may adhere to erythroid precursors via a mechanism similar to the rosetting mediated by STEVOR and GPC in asexual stages. Our results established that STEVOR proteins are not exposed on the GIE surface, thus making them unlikely candidates for binding to erythroid cells.

These results contrast with data reported for asexual stages where 10 to 13% of erythrocytes infected with schizonts are recognized with antibodies directed against the N-terminus domain of STEVOR14–16,30. In a previous study, STEVOR proteins have also been observed at the surface of live GIE17, however antibodies used as controls for erythrocyte membrane integrity in this study were directed against the parasite (anti-Pfg27 antibodies) and may not be able to detect a low leakiness of the erythrocyte membrane as we observe here with anti-Band 3 antibodies. Despite the absence of surface exposure, we observed STEVOR proteins in association with the GIE membrane (Figs 3c, 4b and 5a), in agreement with previous studies17,18,28. These observations are consistent with a model of a two-transmembrane topology at the GIE membrane with a surface-exposed short hypervariable region and C-terminal and N-terminal regions facing the erythrocyte cytoplasm31,32. Further studies are needed to validate this predicted topology and confirm that it differs from the topology with only one transmembrane domain observed in asexual stages. It is tempting to speculate that the potential different topologies in asexual and sexual stages may reflect different functions of the protein and may reveal a strategy that the parasite has evolved to differently modify its host cell to adapt to different microenvironments. For instance, it has been proposed that the STEVOR-mediated stiffness of immature GIE may contribute to their sequestration by mechanical retention in the bone marrow parenchyma17,33. Since the increased erythrocyte stiffness depends on the interaction between the C-terminus domain of STEVOR and the erythrocyte cytoskeletal ankyrin complex28, our results suggest that the STEVOR N-terminus domain may also interact with cytoskeletal proteins and contribute to the rigidification of the erythrocyte membrane. This interaction may occur in immature GIE but not in asexual stages where sequestration is mediated by infected cell adhesion to endothelium rather than mechanical retention. On the other hand, surface-exposed STEVOR proteins preferentially localize in proximity to knobs in asexual stages, and this localization has been proposed to confer an advantage to the parasite by reinforcing the cytoadherence of infected erythrocytes16. It is plausible that surface-exposure of the STEVOR adhesive domain is dependent on knobs formation, therefore the absence of knobs in gametocytes stages6 may result in a the two-transmembrane topology leading to absence of STEVOR at the surface. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude that STEVOR exposure and/or STEVOR-mediated adhesion requires an additional co-factor expressed in vivo but not in vitro, or not expressed in our parasite lines.

Other ligand(s) and receptor(s) may also promote adhesion between GIE and erythroblastic islands. For instance, the parasite proteins GEXP07 and GEXP10 exhibit adhesive properties and are exposed at the surface of erythrocytes infected with early gametocytes34. However this hypothesis is not supported by our results showing the absence of adhesion between several types of erythroid cells and NF54 GIE that constitutively express GEXP proteins. In contrast, other clonally variant adhesins expressed by multigenic families, such as RIFIN35, may be involved in GIE adhesion to erythroid cells since they mediate rosetting in asexual stages via binding to the blood group A antigen and to the Glycophorin A36. Their presence in immature gametocytes37 makes them interesting ligand candidates that need to be investigated in further studies.

It remains to be clarified how gametocytes sequester in the bone marrow parenchyma. The proposed contribution of infected erythrocyte stiffness to this phenotype is supported by recent data showing that sildenafil citrate, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor known to keep GIE in a rigid state38, increases the enrichment of Plasmodium berghei gametocytes in the bone marrow of infected mice39. It is also possible that immature GIE adhere to non-erythroid bone marrow cells. Interestingly, recent work revealed that erythrocytes infected with immature gametocytes or with asexual stages adhere to human bone marrow mesenchymal cells via trypsin-sensitive parasite ligands exposed on the erythrocyte surface40. Although the ligand(s) and receptor(s) promoting this adhesion are not identified yet, this mechanism may contribute to immature GIE sequestration in the parenchyma. Furthermore, we cannot exclude that the association of immature gametocytes with erythroblastic islands reflects the infection of erythroblasts by gametocytes. Indeed, several experiments using ex vivo culture of human primary erythroblasts showed that the development of gametocytes could take place in hematopoietic cells as early as the orthochromatic stages4, suggesting that gametocytes may preferentially develop in erythroblasts or reticulocytes in the human marrow.

In conclusion, this study provides insights into the interplay between P. falciparum gametocytes and human bone marrow cells. Also, our results highlight that STEVOR proteins may have different role and topology in asexual and sexual stages. These observations raise some questions about the function of other variant antigens in gametocytes.

Methods

Parasite culture

The VarO and the 3D7/Pf13 parasite lines were described elsewhere21,25. The P. falciparum isolate NF5441 was used to generate clonal and transgenic lines (see Supplemental Table 1 for description of parasite lines). Parasites were cultivated in vitro as described42 using RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human serum, hypoxanthin 10 mM, gentamicin (20 µg/ml) and human erythrocytes at 5% hematocrit. Infected erythrocytes were cultivated at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 2% O2. To obtain synchronous asexual stages, parasites were synchronized by the isolation of trophozoites by magnetic isolation using a MACS depletion column (Miltenyi Biotec) in conjunction with a magnetic separator, and placed back into culture. After the invasion of merozoites, ring-stage parasites were selected by magnetic depletion of trophozoites to obtain a tighter window of synchronization. Synchronous production of gametocytes was achieved as described43. Briefly, the culture medium was supplemented with 50 mM N-acetyl-glucosamine from day 0 onwards, and a medium replacement was continued for 5 to 6 days to eliminate the asexual stages.

DNA construct and transfection

To overexpress the PF3D7_1040200-tagged protein having two adjacent Ty1 at the carboxy-terminal domain, the plasmid pLN-stevorPF3D7_1040200-Ty1 was constructed by amplifying the PF3D7_1040200 gene from NF54 genomic DNA using these primers: Fw, 5′-AAGGCCGGCCCTCGAGATGAAGATGTATTACCTTAAAATGATATTGTTTAAC and Rv, 5′- AAGGCGCGCCACTTACATAAATGTTTCTTGCATTGATGTTTCAATGAATTTTTTC. The PCR product was restriction digested with FseI and AscI and inserted into the expression vector pLN-Ty1C44. This expression vector contains an expression cassette that is driven by the P. falciparum 5′ calmodulin promoter and the 3′ hsp86 terminator, to ensure a high expression level of stevor gene, and blasticidin (bsd) expression cassette for selection of transformed parasites. Sequence of the plasmid was confirmed by sequencing: Fw, 5′-TGTATATTGGGGTGATGATAAAATG and Rv, 5′-AATATGTATATTTTAAACTAGAAAAGG. Parasites were transfected into the NF54-derived B10 clone17 as previously described, by electroporating ring-stage parasites45. Briefly, 0.2 cm electroporation cuvettes were loaded with 0.100 mL of ring-stage infected erythrocytes and 60 μg of plasmid DNA in cytomix solution. Positive selection was achieved using 2.5 μg/mL blasticidin (Euromedex). Episomal plasmid rescue experiment was performed by transforming E. coli competent cells with 100 ng of purified P. falciparum genomic DNA. To remove episomal overexpression, parasites were cultivated without blasticidin for 14 generations.

Erythroid Cell Culture

The K562 cell line was cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 200 U/mL penicillin, 200 mg/mL streptomycin and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum46. The UT7 cell line was cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 2 U/mL erythropoietin (Epo), 2 mM L-glutamine, 200 U/mL penicillin, 200 mg/mL streptomycin and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum47. The human primary erythroblasts culture method was adapted from Freyssinier et al.48. CD34+ progenitor cells were obtained from human donors who gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. The study has been approved by the French ministry of higher education and research review board (DC-2012–1645). CD34+ cells were collected from G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood after cytapheresis and purified by an immunomagnetic procedure (MACS CD34 isolation Kit; Miltenyi Biotech). CD34+ cells were cultured in 5% CO2 at 37 °C in Iscove DMEM (IMDM) containing 15% BIT 9500 (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada), 100 ng/mL Stem Cell Factor (SCF, Milteny Biotech), 10 ng/mL IL6 and 10 ng/mL IL3. After 7 days of culture, a purified population of human erythroid progenitors was obtained by positive selection on CD36 immunomagnetic beads. CD36+ cells were cultured with 2 U/mL Epo, 100 ng/mL SCF and 10 ng/mL IL3 to allow the erythroid differentiation.

Adhesion assay

Infected-erythrocytes were purified by magnetic isolation using a MACS depletion column as described above. Purified infected-erythrocytes were stained with PKH67 (Sigma) according to manufacturer’s instructions and Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) (1/20000). Erythroid cells were stained with PKH26 and Hoechst 33342. 20% of purified infected-erythrocytes were added to 80% of erythroid cells. Cells were allowed to adhere for 2 hours in 100% human serum at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 2% O2. After incubation, at least 300 cells per condition were counted at the X100 objective of a Leica DMi8 microscope. Statistical significances of adhesion rates were determined with the Wilcoxon test, and raw p-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure49.

Antibodies

The 3D7 genomic DNA sequence coding for the N-terminal part including the semi-conserved region, the first hydrophobic stretch and the variable domain of STEVOR PF3D7_0631900 was amplified using the following primers: Fw: 5′-GGGAAGCTTACCCAAATCCATAATCCAC-3′; Rv: 5′-GGGGGATCCTTAAGGGGGAAATGCACCTATAGC-3′). Recombinant protein was produced in E. coli and antisera directed against the protein was produced in rabbits (Pineda Antikörper-Service).

Immunofluorescence assays (IFA)

To detect the GPC at the surface of nucleated erythroid cells and erythrocytes were fixed during 10 minutes with a solution of 1X Phosphate-Buffered-Saline (PBS)/4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) or 1% PFA, respectively. After 2 hours of pre-incubation in 1X PBS/2% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), slides were incubated overnight with a mouse monoclonal antibody directed against Glycophorin C/D (Santa Cruz) (1/200).

To assess STEVOR protein expression in the different parasite lines, GIE were fixed with a solution of 1X PBS/1% PFA/0.25% glutaraldehyde for 10 minutes and permeabilized with a solution of 1X PBS/0.1% Triton (Sigma) for 10 minutes or GIE were air-dried on glass blood smears and methanol-fixed at −20 °C for 10 minutes. After 2 hours of pre-incubation in 1X PBS/2% BSA, slides were incubated overnight with rabbit antibodies raised against STEVOR PF3D7_030040028 (1/200), with a mouse antibody raised against the intracellular domain of Band 3 protein (Santa Cruz) (1/10000) or with a mouse mAb directed against Ty1 (Diagenode) (1/50000).

For live surface IFA, GIE were incubated 1 hour at 37 °C with antibodies directed against STEVOR PF3D7_0300400 (1/200), the N-terminal domain of Glycophorin A/B (Santa Cruz) (1/500) and the intracellular domain of Band 3 protein (Santa Cruz) (1/10000).

All incubations with primary antibodies are followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1/2000) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1/2000) and Hoechst 33342 (Life technologies) (1/20000) for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were observed at X100 magnification using a Leica DMi8 microscope.

Western-blotting analysis

For the detection of the GPC in erythroid cells, proteins were extracted from whole cells with a RIPA buffer (Sigma) in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein concentration was determined using a Pierce BSA assay kit (Thermo Scientific). 30 to 60 µg of proteins (depending on cell types) were denatured in protein loading buffer (Biorad) during 10 min at 95 °C and were separated by 4–12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane and blocked 2 hours in 5% non-fat dry milk. Immunoblots were probed overnight with primary mouse GPC antibody (Santa Cruz) (1/500) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or IgG secondary antibodies (Promega) (1/10000) for 1 hour. Detection step was performed using the Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

To characterize transgenic parasite lines, stage III GIE were purified by magnetic isolation, pelleted by centrifugation at 1,800 rpm and kept at −80 °C until used. After protein separation and transfer to PVDF membrane, immunoblots were probed overnight with rabbit antibodies against STEVOR PF3D7_030040028 (1/2000) and mouse anti-PfHsp7028 (1/5000) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Promega) (1/10000) for 1 hour. Detection step was performed using the Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The levels of STEVOR were quantified by densitometry using the ImageJ software by determining the ratio of STEVOR level relative to the loading control PfHsp70.

RT-qPCR

RNA was extracted from mid-trophozoite stages at 28 hours post-invasion (hpi). RNA was prepared with Trizol (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer and treated with DNAse I (Roche). RNA was then reverse-transcribed using Superscript III that was primed with random hexamer primers (Invitrogen). The absence of genomic DNA contamination was confirmed by PCR amplification with arginyl-tRNA synthetase primers (PF3D7_1218600) on RNA samples that lacked reverse-transcriptase. Real-time PCR was performed using a Light Cycler 480 (Roche). Reactions were prepared in 10 μL volumes using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Roche) and 1 µM primers. Relative quantification of cDNA was performed using the standard curve method to determine the efficiency of the target and reference amplification and to quantify cDNA in each sample. The relative copy number for each gene was determined as the ratio of the relative amount of target gene cDNA/the relative amount of housekeeping control gene cDNA arginyl-tRNA synthetase (PF3D7_1218600). The threshold detection level (TDL) was defined as 3 CT below the CT value that was obtained for the water control or RNA samples treated without reverse-transcriptase. Gene-specific primers for stevor genes and housekeeping genes were published elsewhere23.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

GN was supported by a labex GR-Ex fellowship. The labex GR-Ex, reference ANR-11-LABX-0051 is funded by the program “Investissements d’avenir” of the French National Research Agency, reference ANR-11-IDEX-0005-02. CL, GN, FD, BN and DB acknowledge the financial support from the Cnrs (ATIP-Avenir grant), Inserm and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (“Equipe FRM” grant DEQ. 20170336722). We are grateful to Odile Mercereau-Puijalon and Micheline Guillotte for providing the VarO and the 3D7/Pf13 parasite lines. We thank Emmanuel Bischoff for his support with statistical analysis.

Author Contributions

G.N., F.D., M.L., D.B. and C.R. performed experiments; G.N., F.V. and C.L. analysed data; G.N. performed statistical analysis; R.M.M., J.J.L.R. and A.B. contributed new reagents or analytical tools; G.N., B.N., F.V. and C.L. designed the research; G.N. and C.L. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-36148-y.

References

- 1.Hawking F, Wilson ME, Gammage K. Evidence for cyclic development and short-lived maturity in the gametocytes of Plasmodium falciparum. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1971;65:549–559. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(71)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar R, et al. Molecular evidence for the localization of Plasmodium falciparum immature gametocytes in bone marrow. Blood. 2014;123:959–966. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-520767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farfour E, Charlotte F, Settegrana C, Miyara M, Buffet P. The extravascular compartment of the bone marrow: a niche for Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte maturation? Malar J. 2012;11:285. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joice R, et al. Plasmodium falciparum transmission stages accumulate in the human bone marrow. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:244re245. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chasis JA, Mohandas N. Erythroblastic islands: niches for erythropoiesis. Blood. 2008;112:470–478. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-077883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tiburcio, M. et al. Early gametocytes of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum specifically remodel the adhesive properties of infected erythrocyte surface. Cell Microbiol, 10.1111/cmi.12062 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Craig A, Scherf A. Molecules on the surface of the Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocyte and their role in malaria pathogenesis and immune evasion. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 2001;115:129–143. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00275-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller LH, Baruch DI, Marsh K, Doumbo OK. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:673–679. doi: 10.1038/415673a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers NJ, Daramola O, Targett GA, Hall BS. CD36 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 mediate adhesion of developing Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1480–1483. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1480-1483.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers NJ, Hall BS, Obiero J, Targett GA, Sutherland CJ. A model for sequestration of the transmission stages of Plasmodium falciparum: adhesion of gametocyte-infected erythrocytes to human bone marrow cells. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3455–3462. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.6.3455-3462.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silvestrini F, Tiburcio M, Bertuccini L, Alano P. Differential adhesive properties of sequestered asexual and sexual stages of Plasmodium falciparum on human endothelial cells are tissue independent. PloS one. 2012;7:e31567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho M, Davis TM, Silamut K, Bunnag D, White NJ. Rosette formation of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes from patients with acute malaria. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2135–2139. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2135-2139.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee WC, et al. Glycophorin C (CD236R) mediates vivax malaria parasite rosetting to normocytes. Blood. 2014;123:e100–109. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-541698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niang M, et al. STEVOR is a Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte binding protein that mediates merozoite invasion and rosetting. Cell host & microbe. 2014;16:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niang M, Yan Yam X, Preiser PR. The Plasmodium falciparum STEVOR multigene family mediates antigenic variation of the infected erythrocyte. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000307. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh, H. et al. Expression dynamics and physiologically relevant functional study of STEVOR in asexual stages of Plasmodium falciparum infection. Cell Microbiol19, 10.1111/cmi.12715 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Tiburcio M, et al. A switch in infected erythrocyte deformability at the maturation and blood circulation of Plasmodium falciparum transmission stages. Blood. 2012;119:e172–180. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-414557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McRobert L, et al. Distinct trafficking and localization of STEVOR proteins in three stages of the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6597–6602. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6597-6602.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, et al. Isolation and functional characterization of human erythroblasts at distinct stages: implications for understanding of normal and disordered erythropoiesis in vivo. Blood. 2013;121:3246–3253. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-476390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gautier EF, et al. Comprehensive Proteomic Analysis of Human Erythropoiesis. Cell Rep. 2016;16:1470–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vigan-Womas I, et al. An in vivo and in vitro model of Plasmodium falciparum rosetting and autoagglutination mediated by varO, a group A var gene encoding a frequent serotype. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5565–5580. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00901-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chasis JA, Mohandas N. Red blood cell glycophorins. Blood. 1992;80:1869–1879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavazec C, Sanyal S, Templeton TJ. Expression switching in the stevor and Pfmc-2TM superfamilies in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:1621–1634. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yam XY, Niang M, Madnani KG, Preiser PR. Three Is a Crowd - New Insights into Rosetting in Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vigan-Womas I, et al. Allelic diversity of the Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 entails variant-specific red cell surface epitopes. PloS one. 2011;6:e16544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blythe JE, et al. Plasmodium falciparum STEVOR proteins are highly expressed in patient isolates and located in the surface membranes of infected red blood cells and the apical tips of merozoites. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3329–3336. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01460-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bachmann A, et al. Temporal expression and localization patterns of variant surface antigens in clinical Plasmodium falciparum isolates during erythrocyte schizogony. PloS one. 2012;7:e49540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naissant B, et al. Plasmodium falciparum STEVOR phosphorylation regulates host erythrocyte deformability enabling malaria parasite transmission. Blood. 2016;127:e42–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-690776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scherf A, Lopez-Rubio JJ, Riviere L. Antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:445–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachmann A, et al. A comparative study of the localization and membrane topology of members of the RIFIN, STEVOR and PfMC-2TM protein families in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Malar J. 2015;14:274. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0784-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lavazec C, Sanyal S, Templeton TJ. Hypervariability within the Rifin, Stevor and Pfmc-2TM superfamilies in Plasmodium falciparum. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6696–6707. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Templeton TJ. The varieties of gene amplification, diversification and hypervariability in the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 2009;166:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiburcio M, Sauerwein R, Lavazec C, Alano P. Erythrocyte remodeling by Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in the human host interplay. Trends Parasitol. 2015;31:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hermand P, et al. Plasmodium falciparum proteins involved in cytoadherence of infected erythrocytes to chemokine CX3CL1. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33786. doi: 10.1038/srep33786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kyes SA, Rowe JA, Kriek N, Newbold CI. Rifins: a second family of clonally variant proteins expressed on the surface of red cells infected with Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9333–9338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goel S, et al. RIFINs are adhesins implicated in severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nat Med. 2015;21:314–317. doi: 10.1038/nm.3812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petter M, Bonow I, Klinkert MQ. Diverse expression patterns of subgroups of the rif multigene family during Plasmodium falciparum gametocytogenesis. PloS one. 2008;3:e3779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramdani G, et al. cAMP-Signalling Regulates Gametocyte-Infected Erythrocyte Deformability Required for Malaria Parasite Transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004815. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Niz M, et al. Plasmodium gametocytes display homing and vascular transmigration in the host bone marrow. Sci Adv. 2018;4:eaat3775. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Messina V, et al. Gametocytes of the Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum Interact With and Stimulate Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Cells to Secrete Angiogenetic Factors. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:50. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ponnudurai T, Leeuwenberg AD, Meuwissen JH. Chloroquine sensitivity of isolates of Plasmodium falciparum adapted to in vitro culture. Trop Geogr Med. 1981;33:50–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fivelman QL, et al. Improved synchronous production of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in vitro. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 2007;154:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vembar SS, Scherf A, Siegel TN. Noncoding RNAs as emerging regulators of Plasmodium falciparum virulence gene expression. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;20:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu Y, Sifri CD, Lei HH, Su XZ, Wellems TE. Transfection of Plasmodium falciparum within human red blood cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:973–977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersson LC, Nilsson K, Gahmberg CG. K562–a human erythroleukemic cell line. Int J Cancer. 1979;23:143–147. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Komatsu N, et al. Establishment and characterization of a human leukemic cell line with megakaryocytic features: dependency on granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin 3, or erythropoietin for growth and survival. Cancer Res. 1991;51:341–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freyssinier JM, et al. Purification, amplification and characterization of a population of human erythroid progenitors. Br J Haematol. 1999;106:912–922. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.