Abstract

Familial amyloid polyneuropathy is a hereditary systemic amyloidosis caused by a mutation in the transthyretin (TTR) gene. Amyloid deposits in tissues of patients contain not only full-length TTR but also C-terminal TTR fragments. However, in vivo models to evaluate the pathogenicity of TTR fragments have not yet been developed. Here, we generated transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans strains expressing several types of TTR fragments or full-length TTR fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein in the body wall muscle cells and analyzed the phenotypes of the worms. The transgenic strain expressing residues 81–127 of TTR, which included the β-strands F and H, formed aggregates and caused defective worm motility and a significantly shortened lifespan compared with other strains. These findings suggest that the C-terminal fragments of TTR may contribute to cytotoxicity of TTR amyloidosis in vivo. By using this C. elegans model system, we found that (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a major polyphenol in green tea, significantly inhibited the formation of aggregates, the defective motility, and the shortened lifespan caused by residues 81–127 of TTR. These results suggest that our newly developed C. elegans model system will be useful for in vivo pathological analyses of TTR amyloidosis as well as drug screening.

Introduction

Hereditary transthyretin (ATTRm) amyloidosis, also called transthyretin (TTR)-related familial amyloid polyneuropathy (TTR-FAP), is a fatal inherited disease associated with extracellular amyloid deposits derived from TTR1. Patients with ATTRm amyloidosis demonstrate polyneuropathy, autonomic dysfunction, cardiac and renal failure, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and other symptoms, all of which may lead to death usually within 10 years2. More than 140 mutations in the TTR gene have now been reported, with the mutation Val30 to Met (Val30Met) being most common and mainly reported in Japan, Portugal, and Sweden3.

TTR forms a 55-kDa homotetramer that consists of four identical 14-kDa monomers with 127 amino acid residues. TTR is mainly produced (secreted) in the liver, eye, and choroid plexus, and it usually exists as a tetramer in the bloodstream4. In patients, TTR dissociates to monomers that are misfolded by mutations and/or aging, which causes polymerization of the dissociated TTR and formation of amyloid fibrils5. Liver transplantation is the most common treatment for patients with ATTRm. Dissociation of the TTR tetramer into monomers is the rate-limiting step in amyloid fibril formation5. Therefore, small molecules that can stabilize the TTR tetramer have been developed as therapeutic agents6, and diflunisal and tafamidis are now used as TTR stabilizers7–10. Although liver transplantation and TTR tetramer stabilizers effectively treat ATTRm amyloidosis, their effects are limited to early stages of the disease and the delay of disease progression, but they do not completely suppress the progression of the pathology11.

Involvement of TTR fragments in the formation of amyloid fibrils has been demonstrated. Amyloid deposits in the tissues of ATTR amyloidosis consist of not only full-length TTR but also C-terminal TTR fragments, especially the fragment with residues 49–127 (TTR49–127)12–15. TTR49–127 can be produced by trypsin treatment of full-length TTR, and it induced amyloid formation in in vitro studies16,17. Structural analysis revealed that the β-strands F and H (residues 91–96 and 115–124, respectively) of TTR had a strong amyloidogenic properties18. However, how TTR fragments affect amyloidosis in vivo remains elusive.

For many years, many attempts have been made to develop an animal model of TTR amyloidosis to clarify the molecular mechanism of the pathogenesis of this disease and to evaluate the therapeutic effects of candidate drugs19. However, transgenic mice and rat models so far reported unfortunately have not manifested the toxic phenotype representing TTR amyloidosis20,21. Transgenic worms expressing human disease-relevant proteins and/or peptides have been developed, however, and have provided information about the molecular mechanisms of disease pathogenesis and served as an efficient screening tool for drug development22–25. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is the major polyphenol in green tea26. Reports have described certain biological functions of EGCG such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities27–30. EGCG has also been demonstrated to inhibit toxic aggregate formation of Aβ, α-synuclein, ataxin-3, and mutant huntingtin, as well as bacterial amyloid formation26,28,31–37. In this study, we describe a Caenorhabditis elegans model that expresses various TTR fragments to elucidate the pathogenesis of C-terminal fragments of TTR in vivo, and we established this model as a tool for screening drug candidates for TTR amyloidosis.

Results

C-terminal fragments of TTR formed aggregates and demonstrated toxic effects in vivo

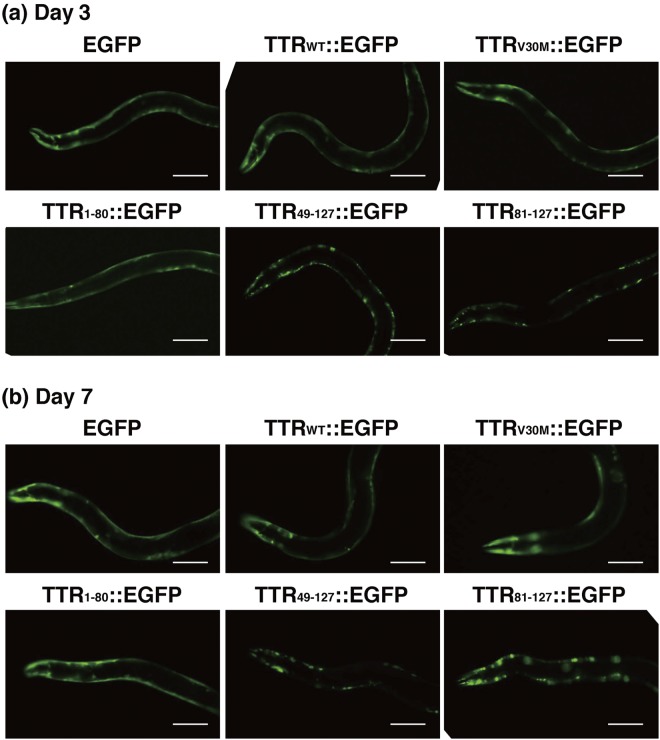

To investigate the pathogenesis of C-terminal fragments of TTR in vivo, we generated a C. elegans model expressing various TTR fragments fused to enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP): the full-length wild-type TTR (TTRWT::EGFP), the 1–80 residue fragment (TTR1–80::EGFP), the 49–127 residue fragment (TTR49–127::EGFP), the 81–127 residue fragment (TTR81–127::EGFP), the full-length TTR but containing a Val30Met mutation (TTRV30M::EGFP), and EGFP alone (EGFP) as a control. TTR49–127 was previously identified in amyloid deposits obtained from patients12–15, and TTR81–127 contains two strong amyloidogenic β-strands—F and H18. The Val30Met mutation is the most common TTR mutation in the world3. Expression of fusion proteins in the body wall muscle cells of C. elegans was achieved by using the unc-54 promoter. Note that TTR::EGFP fusion constructs do not contain a TTR signal sequence; as a result, these fusion proteins are expected to localize in the cytoplasm of the body wall muscle cells. As Fig. 1 shows, EGFP and TTR1–80::EGFP exhibited a diffuse localization pattern throughout the body wall muscle cells. In contrast, TTR49–127::EGFP and TTR81–127::EGFP had discrete aggregates. TTRWT::EGFP and TTRV30M::EGFP, however, gradually formed aggregates as the worms aged (Table 1). Based on fluorescence microscopic findings, these kinds of TTR were likely to form intracellular amorphous shape aggregates in our C. elegans models. These results suggest that the C-terminal fragments of TTR play an important role in aggregate formation in vivo as well as in vitro.

Figure 1.

Expression of TTR::EGFP fusion proteins in C. elegans. Strains expressing EGFP, TTRWT::EGFP, TTRV30M::EGFP, TTR1–80::EGFP, TTR49–127::EGFP, and TTR81–127::EGFP were analyzed. Young adult (Day 3) (a) and aged (Day 7) (b) worms of each strain were evaluated. The day when eggs were laid was designated day 0. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Table 1.

Effect of C-terminal TTR fragments on formation of aggregates.

| Strain | Number of aggregates per worm (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Day 3* | Day 7* | |

| EGFP | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 1.7 |

| TTRWT::EGFP | 5.3 ± 3.4 | 30.5 ± 10.5 |

| TTRV30M::EGFP | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 17.4 ± 6.8 |

| TTR1–80::EGFP | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 3.5 ± 1.9 |

| TTR49–127::EGFP | 67.0 ± 21.9 | 92.5 ± 29.4 |

| TTR81–127::EGFP | 124.2 ± 21.3 | 176.1 ± 14.8 |

*Day 0 = the day when eggs were laid. Data are means ± SD.

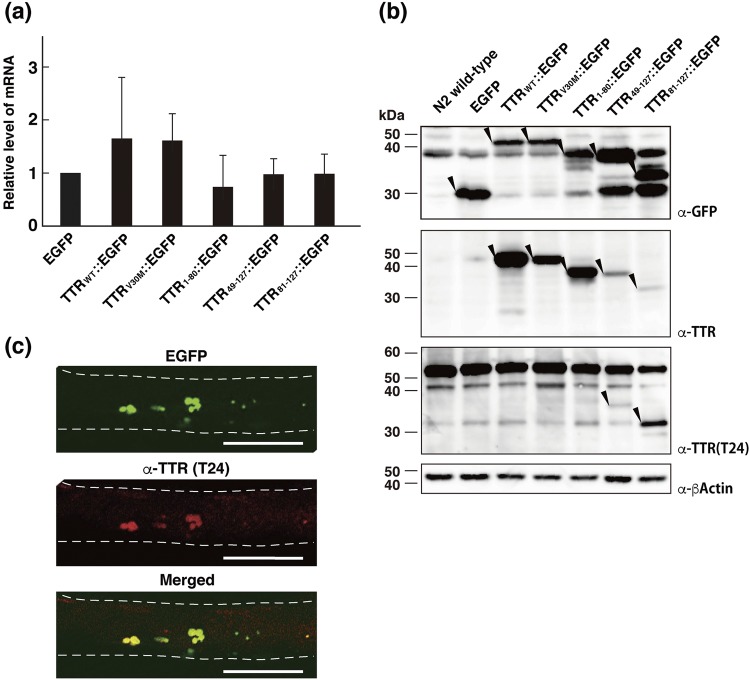

To confirm the expression of TTR::EGFP fusion proteins in transgenic animals, we first measured their transcript levels by quantitative RT-PCR with primers for the gene encoding EGFP. As Fig. 2a illustrates, we found no significant differences. We then performed Western blotting analysis by using an anti-TTR polyclonal antibody, an anti-C-terminal TTR monoclonal antibody (T24)38 that recognized residues 115–124 containing the β-strand H of TTR, and an anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 2b). The anti-GFP antibody detected the EGFP protein and all TTR::EGFP fusion proteins at the expected molecular sizes, although a significant cleaved product, which seems to be EGFP, was also detected in some TTR::EGFP proteins. The anti-TTR polyclonal antibody detected all TTR::EGFP fusion proteins, although this antibody had a low affinity for C-terminal TTR proteins. TTR49–127::EGFP and TTR81–127::EGFP, however, were clearly detected by the T24 antibody. These results suggest that these fusion proteins are indeed expressed in transgenic worms.

Figure 2.

Analyses of the expression of TTR::EGFP fusion proteins in transgenic worms. (a) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed to detect transcripts encoding EGFP from six strains of transgenic worms. The transcript levels were normalized by using act-1 transcripts as internal controls. The relative levels of mRNA were calculated as fold ratios relative to the mRNA level of EGFP-expressing strain. The means and standard deviations from three independent analyses are shown. (b) Total lysates from six strains of transgenic worms and the N2 wild-type worm as a control were analyzed by using SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the antibodies anti-GFP, polyclonal anti-TTR, monoclonal anti-C-terminal TTR (T24), and anti-β-actin (as a loading control). Molecular masses are indicated at the left of the panels. Arrowheads point to the bands of interest. Full size scans of immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. (c) An EGFP fluorescent image (top), immunohistochemical image (middle) obtained with the anti-C-terminal TTR antibody (T24) from a worm expressing TTR81–127::EGFP, and their merged image (bottom) are shown. Broken lines outline the worm surface. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Next, to confirm whether signals for EGFP and TTR co-exist in aggregates, we studied the TTR81–127::EGFP strain by means of fluorescent immunohistochemistry. The TTR signal colocalized with EGFP-containing aggregates in the body wall muscle cells (Fig. 2c), indicating that the fluorescent aggregates contained TTR81–127::EGFP fusion proteins.

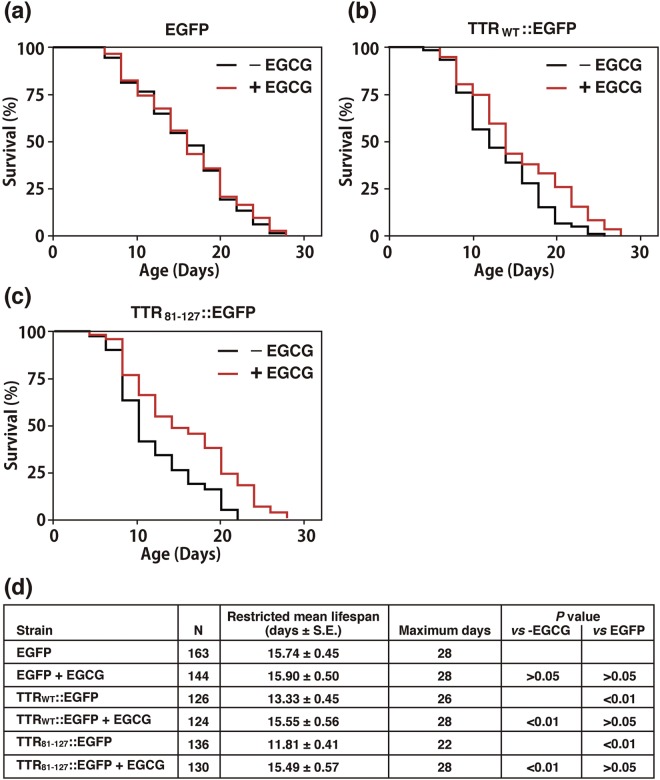

Finally, to evaluate the toxicity of TTR::EGFP aggregates in transgenic worms, we measured the lifespan of these worms. Although it is well known that fluorodeoxyuridine (FUdR) has no effect on the lifespan of wild-type N2 worms, it has been reported that FUdR has some effect on the lifespan of some mutants, such as gas-1, in an FUdR concentration-dependent manner39. Therefore, we used FUdR at a relatively low concentration of 16 μM (compared to the standard 100 μM) in our lifespan assays. Figure 3 shows that the TTR81–127::EGFP strain had the shortest lifespan among all transgenic worms. The TTR1–80::EGFP strain that rarely formed aggregates had the same lifespan as the EGFP strain. Lifespans of the TTRWT::EGFP, TTRV30M::EGFP, and TTR49–127::EGFP strains fell between these two values. These results indicate that the formation of aggregates may be related to toxicity. On the basis of these data, we expect that transgenic worms forming toxic TTR aggregates may be a suitable animal model of ATTR amyloidosis and can be used to screen drug candidates that would cure and/or prevent amyloidosis.

Figure 3.

Effect of TTR::EGFP fusion proteins on lifespan. (a) More than 100 worms of each of the six kinds of transgenic worms expressing EGFP, TTRWT::EGFP, TTRV30M::EGFP, TTR1–80::EGFP, TTR49–127::EGFP, or TTR81–127::EGFP were used to investigate worm lifespan. The data were processed via Kaplan–Meir survival analysis of OASIS2 (https://sbi.postech.ac.kr/oasis2/). Plots represent at least two independent experiments. Colour was determined with the aid of the COLORBREWER 2.0 software (www.colorbrewer2.org). (b) Restricted mean lifespans, maximum days, and P values are shown for the different strains.

EGCG inhibited the formation of TTR::EGFP aggregates in vivo

Using our novel transgenic worm models, we investigated the therapeutic effects of three candidate drugs: diflunisal, β-cyclodextrin, and EGCG. Diflunisal stabilizes TTR tetramers and inhibits the progression of amyloidogenesis8. β-Cyclodextrin reportedly interacts with TTR and prevents protein misfolding40. EGCG is a main active ingredient of green tea and reportedly inhibits protein aggregation and remodels mature amyloid fibrils consisting of Aβ1–40, IAPP8–24, or Sup35NM7–1641.

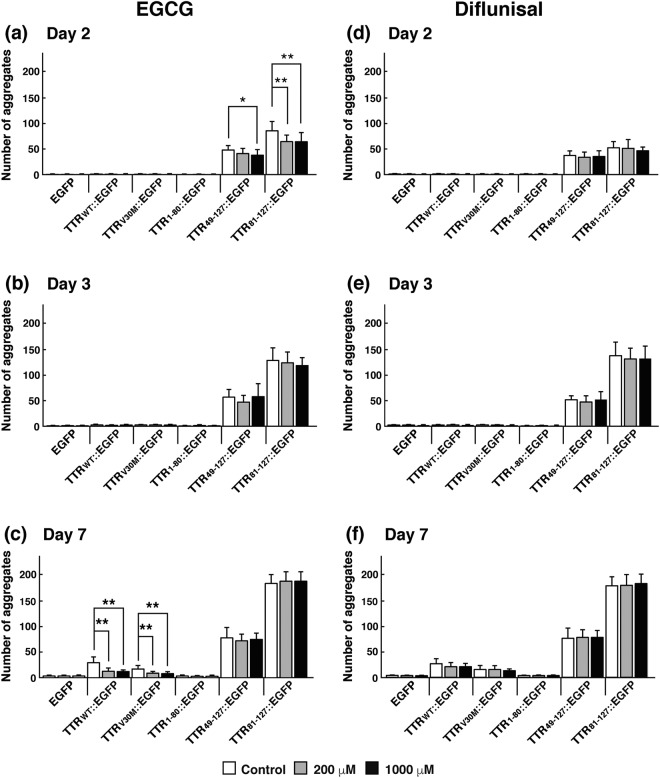

To elucidate the effect of these candidate drugs on the formation of aggregates, we counted the number of aggregates in transgenic worms grown in the presence or absence of the drugs. We found that the number of aggregates was reduced in L3 larvae of TTR49–127::EGFP and TTR81–127::EGFP worms fed EGCG (day 2 in Fig. 4a). Note that we defined the day when eggs were laid as day 0. A higher concentration of EGCG had a stronger effect. However, this inhibitory effect of EGCG on aggregate formation gradually decreased as worms aged (Fig. 4a–c). In contrast, EGCG inhibited TTR aggregate formation in aged worms of TTRWT::EGFP and TTRV30M::EGFP strains (day 7 in Fig. 4c). Given that the formation of aggregates was observed in earlier developmental stages in TTR49–127::EGFP and TTR81–127::EGFP worms but not in TTRWT::EGFP and TTRV30M::EGFP worms, as shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1, these results suggest that EGCG has an inhibitory effect on aggregate formation and delays the onset of aggregate formation. Diflunisal and β-cyclodextrin, however, did not inhibit TTR aggregate formation in the transgenic worms (Fig. 4d–f and Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 4.

Effects of EGCG and diflunisal on the formation of TTR::EGFP aggregates in transgenic worms. Six kinds of transgenic worms expressing EGFP, TTRWT::EGFP, TTRV30M::EGFP, TTR1–80::EGFP, TTR49–127::EGFP, or TTR81–127::EGFP were used. Effects of EGCG (a–c) and diflunisal (d–f) on aggregation in worms were analyzed, and the number of aggregates in each worm was counted on days 2 (a,d), 3 (b,e), and 7 (c,f). The day when eggs were laid was defined as day 0. Worms were grown in the absence of EGCG (white bars) or in the presence of 200 μM (gray bars) or 1000 μM (black bars) EGCG. Plots represent at least three independent experiments (16 animals for each strain). Error bars indicate the SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

EGCG improved the motility of transgenic worms

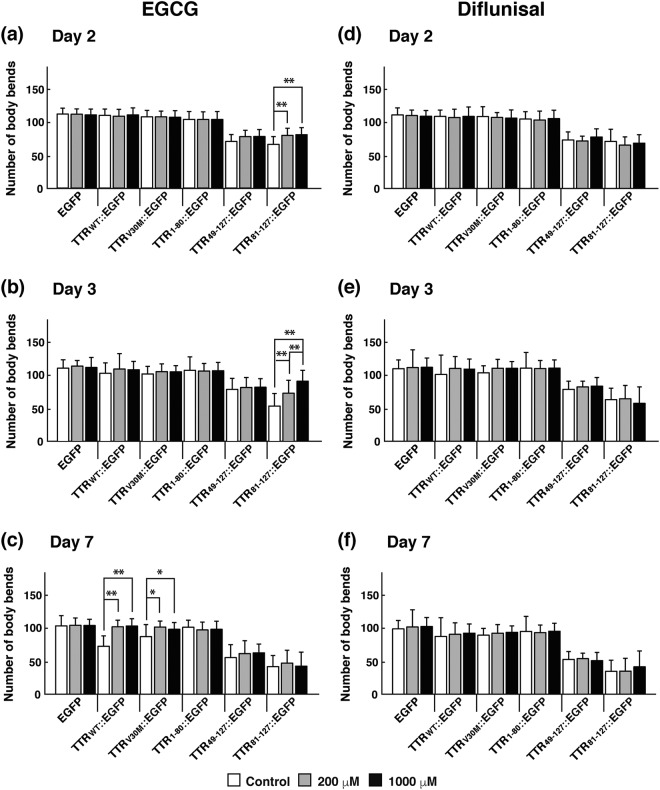

As Fig. 5 illustrates, TTR49–127::EGFP and TTR81–127::EGFP worms manifested a severe motility defect from the larval stage. Given that these two transgenic strains had clear and discrete aggregates as seen in Fig. 1, these results indicate that TTR::EGFP aggregates demonstrated toxicity in vivo. We next evaluated the motility of transgenic worms in the presence and absence of three candidate drugs at different developmental stages. Worms were placed in M9 buffer, and the number of body bends of the worms was counted. We found that EGCG improved the motility of larvae of TTR49–127::EGFP and TTR81–127::EGFP worms but not that of the aged worms (Fig. 5a–c). EGCG did improve the motility of aged TTRWT::EGFP and TTRV30M::EGFP worms, however (Fig. 5c). As in the case of the effects of diflunisal and β-cyclodextrin on aggregate formation, these drugs had no effect on motility in any worm strain (Fig. 5d–f and Supplementary Fig. S3). Taken together with the effects on aggregate formation, only EGCG among the three drugs had inhibitory activity against toxic TTR::EGFP aggregates.

Figure 5.

Effects of EGCG and diflunisal on motility of transgenic worms. Six kinds of transgenic worms expressing EGFP, TTRWT::EGFP, TTRV30M::EGFP, TTR1–80::EGFP, TTR49–127::EGFP, or TTR81–127::EGFP were used. Effects of EGCG (a–c) and diflunisal (d–f) on worm motility were analyzed, and the number of body bends of worms per minute was counted in M9 buffer on days 2 (a,d), 3 (b,e), and 7 (c,f). The day when eggs were laid was defined as day 0. Worms were grown in the absence of EGCG (white bars) or in the presence of EGCG at 200 μM (gray bars) or 1000 μM (black bars). Plots represent at least three independent experiments (16 animals for each strain). Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

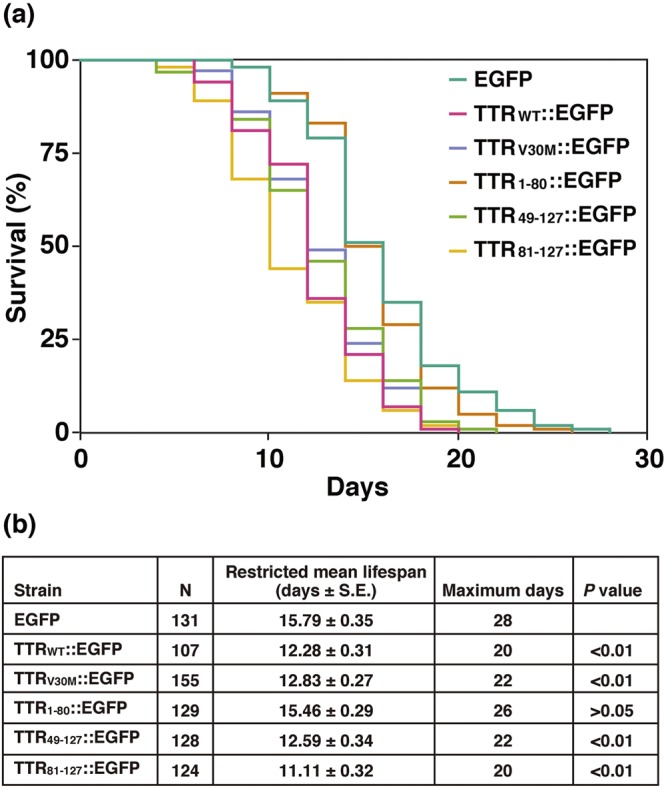

EGCG improved the survival of transgenic worms

To determine whether EGCG can improve survival of transgenic worms, we used three transgenic strains, the EGFP alone strain as a control, the TTRWT::EGFP strain showing a moderately shortened lifespan, and the TTR81–127::EGFP strain showing a severely shortened lifespan (Fig. 3). We found that EGCG had no effect on EGFP-expressing controls (Fig. 6a,d), but it significantly improved the lifespans of animals expressing either TTRWT::EGFP or TTR81–127::EGFP (Fig. 6b–d).

Figure 6.

Effect of EGCG on lifespan of transgenic worms. Three kinds of transgenic worms expressing EGFP (a), TTRWT::EGFP (b), or TTR81–127::EGFP (c) were studied in the absence (black line) and presence (magenta line) of 1 mM EGCG. Data were processed via Kaplan–Meir survival analysis of OASIS 2 (https://sbi.postech.ac.kr/oasis2/). Plots represent at least two independent experiments. (d) Restricted mean lifespans, maximum days, and P values are shown.

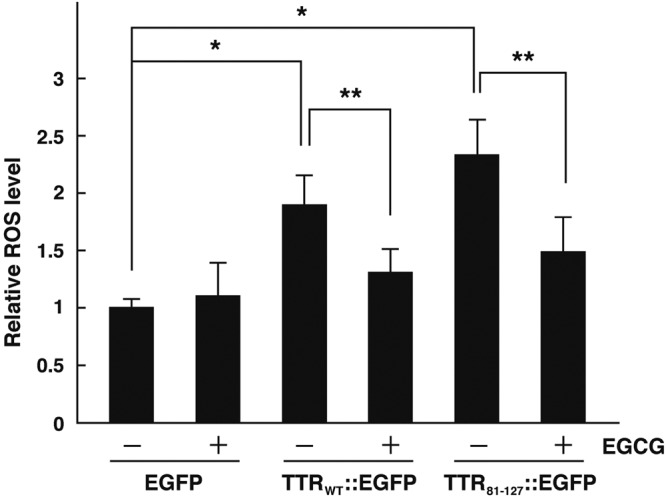

EGCG reduced the intracellular ROS level in the worm model

One interesting finding was that EGCG significantly restored the shortened lifespan of worms expressing TTR81–127::EGFP but did not inhibit aggregate formation or improve the motility defect in aged worms expressing TTR81–127::EGFP. These results suggested that EGCG may have a therapeutic effect on the model worms other than inhibiting aggregate formation. A previous study reported a relationship between the pathogenesis of ATTR amyloidosis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in TTR amyloid deposits in the tissues of patients42. EGCG also reportedly possesses free radical-scavenging activity41,43. Therefore, we measured cellular ROS levels in transgenic worms in the presence and absence of EGCG by using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate as a molecular probe. The TTRWT::EGFP and TTR81–127::EGFP strains showed higher ROS levels than did control worms, which suggests that TTR aggregates increased the cellular ROS levels in C. elegans. In the presence of EGCG, however, the higher ROS levels in the two TTRWT::EGFP and TTR81–127::EGFP strains were reduced to nearly the control level (Fig. 7). These results clearly indicate that TTR aggregates increased cellular ROS levels and that EGCG demonstrated free radical-scavenging activity in C. elegans.

Figure 7.

Effect of EGCG on ROS levels in transgenic worms. Three kinds of transgenic worms expressing EGFP, TTRWT::EGFP, or TTR81–127::EGFP were used. The synchronized L1 worms were grown on NGM agar plates in the absence or presence of 1 mM EGCG for 3 days. ROS levels were measured with H2DCF-DA as a molecular probe. Results are expressed as relative ROS levels (relative to the untreated EGFP worms). Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

In this study, we generated five kinds of transgenic C. elegans strains and established that the C-terminal fragments of TTR, TTR49–127, and TTR81–127 easily formed aggregates in vivo. TTR49–127 has been found in amyloid deposits of patients12–15. TTR49–127 and TTR81–127 contain two β-strands F and H (residues 91–96 and 115–124, respectively), both of which have been shown to form amyloid efficiently in vitro18. These results suggest that the C-terminal fragments of TTR containing the amyloidogenic β-strands are prone to form aggregates in vivo, a finding that supports the hypothesis that the C-terminal fragment of TTR plays an important role in amyloidogenesis in tissues of patients with ATTR amyloidosis. Furthermore, transgenic worms expressing TTR49–127::EGFP or TTR81–127::EGFP evidenced reduced motility and a shortened lifespan, results that indicate that TTR aggregates contributed to cellular toxicity in vivo. In view of the findings that TTR1–80::EGFP did not produce aggregates or cause cellular toxicity in vivo and that cellular toxicity in the TTR81–127::EGFP strain was stronger than that in the TTR49–127::EGFP strain, the TTR81–127 fragment may be critical for toxicity. The TTRWT::EGFP and TTRV30M::EGFP strains showed mild toxicity as the worms aged, however. The TTR49–127 fragment may be generated by proteolytic cleavage in patients16. C-terminal fragments may thus be produced and accumulate as worms age. Additional in vivo studies are required to determine how the C-terminal TTR fragment is involved in the pathogenesis of TTR amyloidosis.

In view of the cellular toxicity of TTR aggregates, our C. elegans model has potential as a screening tool for therapeutic agents for ATTR amyloidosis. In this study, we evaluated the effects of three candidate drugs on the C. elegans model. We found that when model worms were treated with EGCG, the accumulation of TTR aggregates and the motility defect were delayed, and the lifespan was improved. Note that EGCG did not disrupt or dissociate the aggregates formed, however. Our in vivo observation is supported by the fact that the binding of EGCG to TTR modulates the aggregation mechanism of TTR44. EGCG also reportedly reduced Aβ-induced and ataxin-3-induced toxicity in transgenic worm models33,36,45. These results suggest that EGCG has an inhibitory effect against aggregate-induced cellular toxicity. We thus propose that EGCG combined with a putative aggregate disruptor may be a powerful therapeutic strategy. Alternatively, by using EGCG as a lead compound, a new compound with aggregate disruptor activity may be developed. Our C. elegans model will aid such a process.

Diflunisal and β-cyclodextrin, however, had no therapeutic effect in our transgenic worms. Diflunisal as a TTR tetramer stabilizer may not have a therapeutic effect on the intracellular monomeric TTR species in our model worms, in which TTR::EGFP proteins are produced and exist in the cytoplasm. Very recently, Madhivanan et al. reported that non-tagged, secreted TTRV30M can form non-native oligomers in the body cavity, causing defects in neuronal morphology and locomotion46. Interestingly, CMPD5, a TTR-selective fluorogenic dye, binds the TTR tetramer in the body cavity and functions as a tetramer stabilizer. Therefore, CMPD5 feeding rescued the locomotion defect caused by TTRV30M46. On the other hand, it can be reasonably assumed that β-cyclodextrin does not inhibit TTR misfolding sufficiently because of its poor intestinal adsorption47. The worm is also covered with a robust cuticle that forms a barrier to chemical uptake. It is interesting to mention that several mutations, including bus-5(br19) with altered cuticle properties, have been identified, and these mutants showed increased permeability, such that they can be used as a suitable strain for drug screening48.

TTR is mainly synthesized by the liver for secretion into the blood, and it usually exists as a tetramer4. In patients, TTR with mutation tends to dissociate and form amyloid fibrils5. Therefore, although we generated the C. elegans model system in body wall muscle cells for the TTR study, we still need to establish a secretion system of TTRWT, TTRV30M, and TTR81–127 and a corresponding detection system in C. elegans to fully understand the mechanism of TTR amyloidosis. Previously, it has been reported that TTRWT was expressed in body wall muscle cells and secreted (strain CL2008). Although secreted TTR was detected throughout the animal, with an intense signal in coelomocytes using an anti-TTR antibody, thioflavin S (an amyloid specific dye)-positive deposits were not observed49. Later, those TTR-expressing coelomocytes in CL2008 were detected using the newly developed amyloid-specific dye X-3450. The newly developed TTR-selective fluorogenic probe, aryl fluorosulfate 4, can also detect secreted TTR tetramers51. Using these probes, it will be possible to discriminate native-TTR (tetramer) and non-native-TTR (oligomer and amyloid) in our future secretion system. In the present study, TTR81–127 was likely to form intracellular amorphous shape aggregates, but we have not determined detailed morphological features of these aggregates. To elucidate detailed morphological features of these TTR aggregates, we should perform further ultrastructural investigations. In addition, it is important to decipher this issue in the future secretion model.

We also demonstrated that TTR aggregates increased the cellular ROS level in transgenic worms and that EGCG inhibited the increase in the cellular ROS level in aggregate-forming transgenic worms. A high ROS level has been proposed to be one of the primary causes of aging in C. elegans52. We thus conclude from these data that EGCG possesses two activities—inhibition of TTR aggregate formation and reduction of accumulated intracellular ROS levels. EGCG may be a good lead compound to develop an effective therapeutic drug for amyloidosis, and the C. elegans model system is ideal for such a screening process. It is important to mention that the TTRWT::EGFP strain at day 3 presented a higher ROS level (Fig. 7) but lower level of aggregates (Fig. 4) and body bends impairment (Fig. 5). This can be explained as follows: it takes time to form TTRWT::EGFP aggregates after synthesis. During this process, a soluble monomer becomes a soluble oligomer, and then becomes soluble and insoluble aggregates. When the soluble oligomer is formed, the ROS level may increase, but the phenotypic impairment may not yet appear. It is known that TTR is frequently and post-translationally modified by oxidation. When the TTR-expressing strain CL2008 was treated with oxidative stress-inducing reagents, such as menadione, modified TTR was formed, causing the toxic effect. However, when an anti-oxidant was treated simultaneously, the toxic effect was not observed, suggesting that the C. elegans model system is suitable for the post-translational protein modification analysis53.

In conclusion, our newly developed C. elegans model will be useful for in vivo pathological analyses of TTR amyloidosis as well as drug screening.

Methods

Chemicals

EGCG (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan) and β-cyclodextrin (a gift from Dr. H. Jono, Department of Clinical Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kumamoto University) were dissolved in water and stored at −20 °C. Diflunisal (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20 °C. Drugs were added after pouring plates. The control group was treated with the solvent used, minus the drug (i.e. add water for EGCG and β-cyclodextrin controls), and the equivalent concentration (a final concentration of 0.05%) of DMSO was used for the diflunisal control.

Plasmid construction

To create a translational fusion of human full-length TTR with an EGFP, the full-length human cDNA for TTR was amplified via PCR by using PrimeStar HS DNA polymerase (TaKaRa, Otsu, Japan) and the primers ns-fTTR-5ʹ-SalI and TTR-3ʹ-BamHI and was cloned into pEGFP-1 (Clonetech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) to yield pCKX3305. A resultant fusion gene for TTR::EGFP was then amplified with the primers ns-fTTR-5ʹ-SalI and EGFP-3ʹ-EcoRV and cloned into pPD30.38 containing the promoter and enhancer elements from unc-54 myosin heavy-chain locus54 to yield pCKX3307. The fusion protein will be expressed in C. elegans body wall muscle cells. To create a translational fusion of a truncated TTR81–127 with EGFP, we amplified a DNA fragment for TTR81–127 with the primers TTR-5ʹ-SalI and TTR-3ʹ-BamHI and cloned it into pEGFP-1 to yield pCKX3301. We then amplified TTR81–127::EGFP with pCKX3301 as a template and the primers TTR-5ʹ-SalI and EGFP-3ʹ-EcoRV and cloned it into pPD30.38 to yield pCKX3303. To create other translational fusions of truncated human TTR with EGFP, we performed PCR with pCKX3307 as a template and the primer sets 1–80-down and 1–80-up for TTR1–80::EGFP, and ns49–127-down and ns49–127-up for TTR49–127::EGFP, by using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Cedar Creek, TX, USA), to yield pCKX3311 and pCKX3313, respectively. To create a point mutation for V30M, we performed PCR with pCKX3307 as a template and the primers V30M-down and V30M-up, by using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, to yield pCKX3309. To create an EGFP expression vector, we performed PCR with pCKX3307 as a template and the primers nsEGFP-down and nsEGFP-up, by using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, to yield pCKX3316.

Plasmid DNA was column purified by using the Wizard Plus SV Minipreps DNA Purification system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and filtered by using SURPEC-02 (TaKaRa). DNA sequences of the constructed plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes the oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

C. elegans strains and protocols

C. elegans N2 (Bristol) was used as the wild-type strain. Standard nematode growth medium (NGM) was used for C. elegans growth and maintenance at 20 °C55. NGM agar plates were seeded with live Escherichia coli OP50.

Transgenic animals carrying extrachromosomal arrays were created by microinjecting the DNA plasmid into the gonad of young adults at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. Individual fluorescent F2 worms were isolated to establish transgenic lines. At least two independent lines for each construct were isolated and analyzed.

Body bends assays

Body bends assays were performed as described previously56. Worms were placed in M9 buffer, and the number of body bends of the worms was counted manually for 1 min when a worm swung its head to either left or right. Approximately 15 worms were analyzed for each experimental condition. Worms were analyzed at days 2, 3, and 7. The day when eggs were laid was defined as day 0.

Lifespan assays

Lifespan assays were performed essentially according to standard protocols as described in Murayama et al.57. Briefly, synchronized young adults were treated with 0.3 mg/ml fluorodeoxyuridine (FUdR) for 24 h to prevent production of progeny. The worms were then transferred to fresh 0.2 mg/ml (16 μM) FUdR-containing plates in the presence or absence of EGCG (final concentration 1 mM). Surviving and dead worms were counted every other day. We did not count worms that died due to internal hatching or crawling up the plate wall. The day when worms reached the young adult stage was said to be day 0. Lifespan assays were repeated at least twice. Data analysis was performed as described by Han et al.58, by using the publicly available analysis suite OASIS 2 (Online Application for Survival Analysis 2) (https://sbi.postech.ac.kr/oasis2/).

Fluorescence microscopic observation

Worms were placed in M9 buffer containing levamisole (0.5 mg/ml) on a slide glass, and images were obtained via the Olympus Power BX51 microscope equipped with a CoolSnapHQ CCD camera. MetaMorph software was used to process acquired images.

Worms were placed in M9 buffer containing levamisole (0.5 mg/ml) on a slide glass, and the number of TTR::EGFP aggregates in body wall muscle cells was counted manually via the Olympus SZX16 fluorescence microscope with a x115 magnification. Aggregates were defined as discrete structures with spherical shape and boundaries easily distinguishable from surrounding fluorescence on all sides. Approximately 10 worms were analyzed for each experimental condition. Worms were evaluated at days 2, 3, and 7. The day when eggs were laid was said to be day 0.

Fluorescence immunohistochemistry

TTR81–127::EGFP-expressing transgenic worms were fixed in Bouin’s fixative/methanol/β-mercaptoethanol (40:40:1) and immunostaining was performed59,60. The primary and secondary antibodies used were the mouse anti-TTR monoclonal antibody (T24) at a 50× dilution and the goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 594) antibody at a 50× dilution, respectively. A confocal laser scanning microscope (FV1200; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to visualize stained samples.

Quantitative real-time PCR for mRNA quantification

L4-stage worms of each strain grown on 6-cm NGM plates were collected into 1.5-ml tubes and washed three times with M9 buffer (22 mM KH2PO4, 42 mM Na2HPO4, 85.5 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4) containing 0.01% Tween 20. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA by using an ExScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The LightCycler System (Roche Diagnostic, Basel, Switzerland) with SYBR Premix DimerEraser (TaKaRa) was used to perform all PCR reactions with primers of EGFP forward and EGFP reverse. β-Actin was used as an internal control with primers of β-actin forward and β-actin reverse. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes the oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

Western blotting

L4-stage worms of each strain grown on 6-cm NGM plates were collected into 1.5-ml tubes and washed three times with M9 buffer containing 0.01% Tween 20. The worm pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of PBS and frozen in liquid nitrogen until use. Total lysates were prepared by sonication, and protein concentration was determined by using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples were mixed with SDS sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE by using 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) or 12% SDS-PAGE. The TTR::EGFP protein species in the samples were detected via standard Western blotting protocol by using an anti-TTR antibody (A0002, polyclonal rabbit anti-human prealbumin; DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) (1:1000), the monoclonal antibody T24 (1:100) that recognizes residues 115–124 (cryptic epitope) containing the β-strand H of TTR as described previously38, an anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (1:2000) (Clonetech), and an anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (1:3000) (Sigma-Aldrich). β-Actin was used as a loading control. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulins antibody (DAKO) (1:1000) and HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulins antibody (DAKO) (1:1000) were used as a secondary antibody for the anti-TTR antibody and other antibodies, respectively. Signals were detected using the ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and LAS-4000 Image Analyser (GE Healthcare).

Measurement of ROS

Intracellular ROS levels in C. elegans were measured with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) as a molecular probe. The hatched worms were grown on NGM plates in the presence or absence of 1 mM EGCG for 3 days, after which they were collected and resuspended in 100 μl of PBS containing 0.01% Tween 20. Worms were sonicated, and the lysates obtained were incubated with H2DCF-DA (50 mM final concentration) in a Costar 96-well microtiter plate at 37 °C. Samples were read every 15 min for 2 h with an xMark Microplate Spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with the emission wavelength at 530 nm. Assays were repeated three times.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance for the number of aggregates, the number of body bends, and ROS levels was analyzed by a Steel-Dwass’s multiple comparison post-hoc test using JMP 9.0 software (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan). For all analyses, a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Dr. H. Jono for providing β-cyclodextrin, and we thank T.M., N.T., S.G., E.M., O.Y., M.A., O.M., K.H., K.K., M.S. and M.M. for their help with the experiments. Y.T. was supported by the Shibasaburo Program, Kumamoto University Foundation. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Japan Society of Promotion of Science (JSPS) (No. 15H04841 to Y.A.) and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the JSPS (Nos 15K09318 and 18K07502 to M.U.).

Author Contributions

Y.T., K.Y., M.U., T.O. and Y.A. conceived the project and designed the experiments. Y.T., K.Y., R.T., M.U., T.M. and Y.M. conducted the experiments. Y.T., K.Y., M.U., T.O. and Y.A. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information Files.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kunitoshi Yamanaka, Email: yamanaka@gpo.kumamoto-u.ac.jp.

Mitsuharu Ueda, Email: mitt@rb3.so-net.ne.jp.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-36357-5.

References

- 1.Ando Y, et al. Guideline of transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis for clinicians. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ando Y, Nakamura M, Araki S. Transthyretin-related familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Arch. Neurol. 2005;62:1057–1062. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.7.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamashita T, et al. General and clinical characteristics of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis in endemic and non-endemic areas in Japan. J. Neuro. 2018;265:134–140. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou X, Aguilar MI, Small DH. Transthyretin and familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Recent progress in understanding the molecular mechanism of neurodegeneration. FEBS J. 2007;274:1637–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly JW, et al. Transthyretin quaternary and tertiary structural changes facilitate misassembly into amyloid. Adv. Protein Chem. 1997;50:161–181. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miroy GJ, et al. Inhibiting transthyretin amyloid fibril formation via protein stabilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:15051–15056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almeida MR, et al. Selective binding to transthyretin and tetramer stabilization in serum from patients with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy by an iodinated diflunisal derivative. Biochem. J. 2004;381:351–356. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekijima Y, Dendle MA, Kelly JW. Orally administrated diflunisal stabilizes transthyretin against dissociation required for amyloidogenesis. Amyloid. 2006;13:236–249. doi: 10.1080/13506120600960882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson SM, Connelly S, Wilson IA, Kelly JW. Biochemical and structural evaluation of highly selective 2-arylbenzoxazole-based transthyretin amyloidogenesis inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:260–270. doi: 10.1021/jm0708735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coelho T, et al. Long-term effects of tafamidis for the treatment of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J. Neurol. 2013;260:2802–2814. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueda M, Ando Y. Recent advances in transthyretin amyloidosis therapy. Transl. Neurodegener. 2014;3:19. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thylen C, et al. Modifications of transthyretin in amyloid fibrils: analysis of amyloid from homozygous and heterozygous individuals with the Met30 mutation. EMBO J. 1993;12:743–748. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergstrom J, et al. Amyloid deposits in transthyretin-derived amyloidosis: cleaved transthyretin is associated with distinct amyloid morphology. J. Pathol. 2005;206:224–232. doi: 10.1002/path.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ihse E, Suhr OB, Hellman U, Westermark P. Variation in amount of wild-type transthyretin in different fibril and tissue types in ATTR amyloidosis. J. Mol. Med. 2011;89:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oshima T, et al. Changes in pathological and biochemical findings of systemic tissue sites in familial amyloid polyneuropathy more than 10 years after liver transplantation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2014;85:740–746. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangione PP, et al. Proteolytic cleavage of Ser52Pro variant transthyretin triggers its amyloid fibrillogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:1539–1544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317488111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcoux J, et al. A novel mechano-enzymatic cleavage mechanism underlies transthyretin amyloidogenesis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015;7:1337–1349. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saelices L, et al. Uncovering the mechanism of aggregation of human transthyretin. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:28932–28943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.659912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buxbaum JN. Animal models of human amyloidosis: are transgenic mice worth the time and trouble? FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2663–2673. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohno K, et al. Analysis of amyloid deposition in a transgenic mouse model of homozygous familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;150:1497–1508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ueda M, et al. A transgenic rat with the human ATTR V30M: a novel tool for analyses of ATTR metabolisms. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;352:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamanaka K, Okubo Y, Suzaki T, Ogura T. Analysis of the two p97/VCP/Cdc48p proteins of Caenorhabditis elegans and their suppression of polyglutamine-induced protein aggregation. J. Struct. Biol. 2004;146:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maxwell CK, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans: an emerging model in biomedical and environmental toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;106:5–28. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McColl G, et al. Utility of an improved model of amyloid-beta (Aβ1-42) toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans for drug screening for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2012;7:57–65. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez BA, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA. C. elegans as a model system to accelerate discovery for Parkinson disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2017;44:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambert JD, Yang CS. Mechanisms of cancer prevention by tea constituents. J. Nutr. 2003;133:3265S–3267S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.12.4172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dona M, et al. Neutrophil restraint by green tea: inhibition of inflammation, associated angiogenesis, and pulmonary fibrosis. J. Immunol. 2003;170:4335–4341. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stangl V, Lorenz M, Stangl K. The role of tea and tea flavonoids in cardiovascular health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2006;50:218–228. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tipoe GL, Leung TM, Hung MW, Fung ML. Green tea polyphenols as an anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory agent for cardiovascular protection. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2007;7:135–144. doi: 10.2174/187152907780830905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavet ME, Harrington KL, Vollmer TR, Ward KW, Zhang JZ. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative effects of the green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate in human corneal epithelial cells. Mol. Vis. 2011;17:533–542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rezai-Zadeh K, et al. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) modulates amyloid precursor protein cleavage and reduces cerebral amyloidosis in Alzheimer transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:8807–8814. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1521-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehrnhoefer DE, et al. Green tea (−)-epigallocatechin-gallate modulates early events in huntingtin misfolding and reduces toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:2743–2751. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonanomi M, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and tetracycline differently affect ataxin-3 fibrillogenesis and reduce toxicity in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:6542–6552. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonanomi M, et al. How epigallocatechin-3-gallate and tetracycline interact with the Josephin domain of ataxin-3 and alter its aggregation mode. Chem. Eur. J. 2015;21:18383–18393. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serra DO, Mika F, Richter AM, Hengge R. The green tea polyphenol EGCG inhibits E. coli biofilm formation by impairing amyloid curli fibre assembly and downregulating the biofilm regulator CsgD via the σE-dependent sRNA RybB. Mol. Microbiol. 2016;101:136–151. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Visentin C, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and related phenol compounds redirect the amyloidogenic aggregation pathway of ataxin-3 towards non-toxic aggregates and prevent toxicity in neural cells and Caenorhabditis elegans animal model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:3271–3284. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arita-Morioka K, et al. Inhibitory effects of Myricetin derivatives on curli-dependent biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:8452. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26748-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hosoi A, et al. Novel antibody for treatment of transthyretin amyloidosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:25096–25105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.738138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Raamsdonk JM, Hekimi S. FUdR causes a twofold increase in the lifespan of the mitochondrial mutant gas-1. Mech. Aging Dev. 2011;13:519–521. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jono H, et al. Potential use of glucuronylglucosyl-β-cyclodextrin as a novel therapeutic tool for familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. Amyloid. 2012;19(Suppl 1):50–52. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2012.674988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palhano FL, Lee J, Grimster NP, Kelly JW. Toward the molecular mechanism(s) by which EGCG treatment remodels mature amyloid fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7503–7510. doi: 10.1021/ja3115696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ando Y, et al. Oxidative stress is found in amyloid deposits in systemic amyloidosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;232:497–502. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Jie G, Zhang J, Zhao B. Significant longevity-extending effects of EGCG on Caenorhabditis elegans under stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;46:414–421. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kantham S, et al. Effect of the biphenyl neolignane honokiol on Aβ42-induced toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans, Aβ42 fibrillation, cholinesterase activity, DPPH radicals, and iron(II) chelation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017;8:1901–1912. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferreira N, et al. Binding of epigallocatechin-3-gallate to transthyretin modulates its amyloidogenicity. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3569–3576. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madhivanan K, et al. Cellular clearance of circulating transthyretin decreases cell-nonautonomous proteotoxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E7710–E7719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801117115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szejtli J, Gerloczy A, Fonagy A. Intestinal absorption of 14C-labelled beta-cyclodextrin in rats. Arzneimittelforschung. 1980;30:808–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiong H, Pears C, Woollard A. An enhanced C. elegans based platform for toxicity assessment. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9839. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10454-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Link CD. Expression of human b-amyloid peptide in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9368–9372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Link CD, et al. Visualization of fibrillar amyloid deposits in living, transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans animals using the sensitive amyloid dye, X-34. Neurobiol. Aging. 2001;22:217–226. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baranczak A, et al. A fluorogenic aryl fluorosulfate for intraorganellar transthyretin imaging in living cells and in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:7404–7414. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Raamsdonk JM. Levels and location are crucial in determining the effect of ROS on lifespan. Worm. 2015;4:e1094607. doi: 10.1080/21624054.2015.1094607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henze A, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model system to study post-translational modifications of human transthyretin. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37346. doi: 10.1038/srep37346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fire A, Harrison SW, Dixon D. A modular set of lacZ fusion vectors for studying gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 1990;93:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90224-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ono K, Parast M, Alberico C, Benian GH, Ono S. Specific requirement for two ADF/cofilin isoforms in distinct actin-dependent processes in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:2073–2085. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murayama Y, Ogura T, Yamanaka K. Characterization of C-terminal adaptors, UFD-2 and UFD-3, of CDC-48 on polyglutamine aggregation in C. elegans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;459:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han SK, et al. OASIS 2: online application for survival analysis 2 with features for the analysis of maximal lifespan and healthspan in aging research. Oncotarget. 2016;7:56147–56152. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirotsu T, Saeki S, Yamamoto M, Iino Y. The Ras-MAPK pathway is important for olfaction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;404:289–293. doi: 10.1038/35005101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Masuda T, et al. Early skin denervation in hereditary and iatrogenic transthyretin amyloid neuropathy. Neurology. 2017;88:2192–2197. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information Files.