Significance

The bacterial transcription factor OxyR is a model example of a highly sensitive and specific hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) sensor. H2O2 reduction by its active-site cysteine triggers protein structural changes leading to an increased transcription of antioxidant genes. By solving the crystal structures of full-length OxyR in both reduced and oxidized states, we provide molecular insight into these structural changes. We also present a H2O2-bound structure with a threonine activating the peroxide, and argue that this H2O2-bound structure may be catalytically more relevant than that seen previously in the study of a sulfinic acid-mimic mutant of the active-site cysteine. Finally, we discuss the commonalities and differences between the peroxidatic mechanisms of peroxiredoxins and OxyR.

Keywords: transcription factor, hydrogen peroxide sensor, redox regulation, X-ray structure

Abstract

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a strong oxidant capable of oxidizing cysteinyl thiolates, yet only a few cysteine-containing proteins have exceptional reactivity toward H2O2. One such example is the prokaryotic transcription factor OxyR, which controls the antioxidant response in bacteria, and which specifically and rapidly reduces H2O2. In this study, we present crystallographic evidence for the H2O2-sensing mechanism and H2O2-dependent structural transition of Corynebacterium glutamicum OxyR by capturing the reduced and H2O2-bound structures of a serine mutant of the peroxidatic cysteine, and the full-length crystal structure of disulfide-bonded oxidized OxyR. In the H2O2-bound structure, we pinpoint the key residues for the peroxidatic reduction of H2O2, and relate this to mutational assays showing that the conserved active-site residues T107 and R278 are critical for effective H2O2 reduction. Furthermore, we propose an allosteric mode of structural change, whereby a localized conformational change arising from H2O2-induced intramolecular disulfide formation drives a structural shift at the dimerization interface of OxyR, leading to overall changes in quaternary structure and an altered DNA-binding topology and affinity at the catalase promoter region. This study provides molecular insights into the overall OxyR transcription mechanism regulated by H2O2.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a reactive oxidative species that is generated in numerous biological processes, and there is established evidence for its participation in cell signaling. Controlling the levels of H2O2 is essential for cellular redox homeostasis, with the intracellular H2O2 concentration normally kept in the nanomolar range (∼1–50 nM) (1–3). Hydrogen peroxide is a strong oxidant that mainly targets metal centers and protein thiol groups (1, 4). However, within thiols, there is a great gap between the oxidation rate of most thiol groups (∼10–102 M−1s−1) and the oxidation rate of specialized protein thiols (≥105 M−1s−1), meaning that only a handful of proteins are relevant for controlling the intracellular H2O2 levels. These proteins have additional structural features, which lower the otherwise high-energy activation barrier of H2O2 reduction, speeding up the otherwise slow reaction (4). Such features have been studied in detail for peroxiredoxins (Prdxs), where a Thr/Cys/Arg triad is mainly responsible for the peroxidatic activity (5, 6). Both the Thr and the Arg favor the reduction of H2O2 by stabilizing the transition state and by polarizing the O–O peroxyl bond (5). For other cases, as in the sulfur-containing glutathione peroxidase family, a Cys/Asn/Gln/Trp tetrad is responsible for the peroxidatic activity, but the details of the H2O2 reduction mechanism have not yet been uncovered (7). In general, structural factors that govern thiol-based H2O2 sensing and catalysis of H2O2 reduction are still unclear.

One protein with exceptionally high reactivity toward H2O2 is the prokaryotic transcription factor OxyR, a member of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family. LTTRs contain two domains: an N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD) and a C-terminal regulatory domain (RD), responsible for sensing specific metabolites (H2O2 in the case of OxyR). OxyR uses its H2O2-reactive peroxidatic cysteine (CP) of its RD domain to sense increased H2O2 concentrations, reacting with H2O2 at a rate of ∼105 M−1s−1 (8) and, upon intramolecular resolution of the sulfenylated CP with the resolving cysteine (CR), transduces this oxidative signal into the transcription of H2O2-detoxifying genes, such as catalase, and iron-chelating proteins (9–12). For many virulent bacteria, OxyR is an important antioxidant defense regulator, as oxyR knockouts are sensitive to oxidative stress and exhibit attenuated virulence (13–19). The sensitivity of OxyR toward H2O2 has been exploited to create the HyPer probe, a genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor that dynamically monitors physiological fluctuations in cellular H2O2 concentrations (20, 21).

The first published crystal structures of the oxidized and reduced states of the RD of Ec-OxyR provided a model in which a rate-limiting conformational change follows CP-CR disulfide formation (8, 22). To date, crystal structures of the OxyR RD from Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Vibrio vulnificus, Neisseria meningitidis, and Porphyromonas gingivalis have been published, displaying a conserved homodimeric arrangement of RD subunits (22–26). So far, the molecular evidence for H2O2 binding and catalysis at the peroxidatic active site of OxyR derives from crystallographic and biochemical studies of P. aeruginosa OxyR (Pa-OxyR). A crystal structure of full-length Pa-OxyR, with the CP mutated to Asp, a sulfinylated cysteine mimic, has been solved with H2O2 bound in the active site, and mutational studies highlighted a role of the active-site residue T100 (Pa-OxyR numbering) for H2O2 reduction (23).

In this study, we focus on the catalytic and regulatory mechanisms of a noncanonical OxyR from the actinomycete Corynebacterium glutamicum (Cg-OxyR), which utilizes a repressor mechanism toward catalase transcription, differing from the typical E. coli OxyR model, which uses an activator mechanism (10, 27, 28). Here, we present the reduced, H2O2-bound, and intramolecular disulfide-bonded crystal structures of Cg-OxyR, and find an altered H2O2 binding configuration with respect to the Pa-OxyR findings (23). By combining structural data with H2O2 consumption assays of selected site-directed mutants of OxyR, we show the critical residues for H2O2 reduction. The structural changes following disulfide formation in Cg-OxyR point toward an allosteric mechanism that regulates the RD homodimeric interface and translates into conformational changes in the OxyR tetrameric assembly. Finally, we explore how Cg-OxyR acts as a H2O2-sensing transcriptional regulator in vivo and discuss the implications of its mode of action.

Results

Full-Length Cg-OxyR Structure Shows a Tetrameric Configuration Differing from Previously Published Structures.

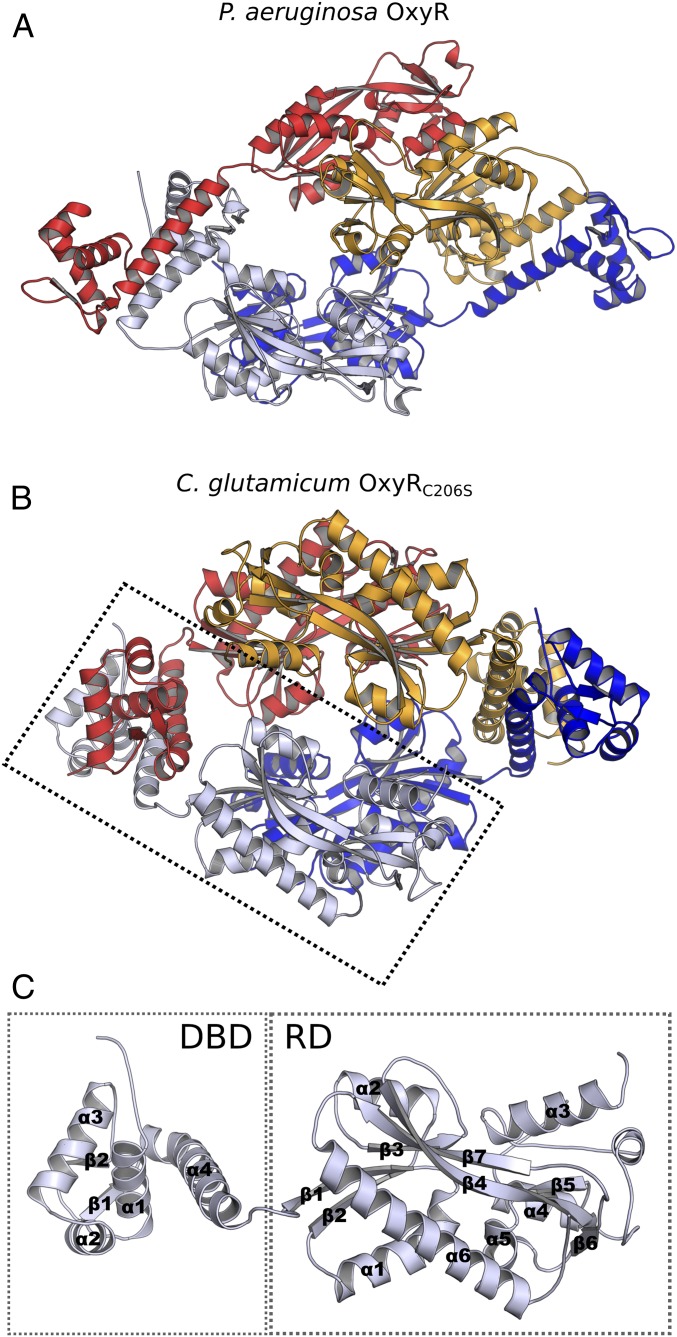

The crystal structure of full-length Cg-OxyRC206S (a CP mutant, C206S, which functionally is redox-insensitive) was solved to a resolution of 2 Å in space group P21 (Table 1). The asymmetric unit contains a homotetramer composed of a dimer of dimers, wherein an intradimer interface is formed between the RDs of each respective protomer, and an interdimer interface is formed between the DBDs from each dimer (Fig. 1B). The tetrameric oligomeric state of reduced OxyR was supported by high-resolution size-exclusion chromatography (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). The overall structural fold of the RD is common to that of the LTTR family, with an N-terminal domain comprised of β-strands sandwiched between two α-helices (subdomain 1), a bundle of β-strands and α-helices (subdomain 2), and a C-terminal α-helix and β-strand traversing both domains (Fig. 1C). The tetrameric conformation of Cg-OxyRC206S differs noticeably from the tetrameric structure of Pa-OxyR (Fig. 1A) (PDB ID code 4X6G) (23) and the putative P. aeruginosa LTTR PA01 (PDB ID code 3FZV). Although the interdimeric interface of the DBDs itself is conserved among the three structures, the tetrameric configuration between the three structures derives from a difference in the hinge bending angle between the DBD and RD subunits. When considering the RD homodimers of Pa-OxyR, an asymmetry in the angle between the RD and the DBD of each subunit of the dimer is apparent. Whereas the DBD of one subunit hinges at an ∼55–60° acute angle relative to the connecting RD, the DBD of the other subunit hinges at an ∼100° obtuse angle relative to the connecting RD. This combination of acute and obtuse angle hinging of the homodimer is reflected in the paring homodimer, which constitutes the full tetramer, therefore resulting in a “slanted” tetrameric assembly. The subunits of the Cg-OxyRC206S structure, on the other hand, all exhibit similarly acute hinging angles between the DBD and RD of each subunit, all with hinge angles in the range of 40–50°. This results in a relatively more symmetric assembly of subunits within the Cg-OxyRC206S tetramer. The hinging angle was determined by the intersect between the midpoint and the C terminus of DBDα4, and the C terminus of DBDα4 and N terminus of RDβ1 (see Fig. 1C for secondary structure annotation), giving a hypotenuse between the midpoint of DBDα4 and the N terminus of RDβ1.

Table 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics

| Data and refinement | OxyRC206S (6G1D) | OxyRH2O2 (6G4R) | OxyRSS (6G1B) |

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P21 | P21 | C2 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 74.4, 63.5, 157.4 | 71.2, 57.0, 154.2 | 161.3, 46.2, 116.7 |

| β (°) | 97.8 | 98.0 | 121.9 |

| Resolution (Å) | 49.23–1.99 (2.03–1.99)* | 152.67–2.62 (2.66–2.62)* | 46.07–2.28 (2.36–2.28)* |

| Rmerge | 0.34 (1.88) | 0.234 (0.90) | 0.12 (0.96) |

| I/σI | 2.8 (0.7) | 5.3 (1.4) | 8.1 (1.5) |

| Completeness (%) | 99 (85.1) | 99.8 (95.1) | 96.6 (91.4) |

| Redundancy | 7 (6.1) | 6.5 (6.5) | 5.1 (4.7) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 44.86–1.99 (2.06–1.99) | 76.34–2.62 (2.71–2.62) | 46.06–2.28 (2.34–2.28) |

| No. reflections | 98,622 (9050) | 36,733 (3460) | 30,760 (2245) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.200/0.221 | 0.235/0.286 | 0.196/0.230 |

| No. atoms | 10,408 | 9,338 | 5,192 |

| Protein | 9,670 | 9,218 | 4,883 |

| Ligand/ion | 70 | 15 | 28 |

| Water | 668 | 405 | 281 |

| B-factors | |||

| Protein | 50.0 | 71.2 | 52.2 |

| Ligand/ion | 44.7 | 53.5 | 60.8 |

| Water | 54.7 | 41 | 45.3 |

| Rmsd | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.02 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.7 | 0.6 | 1.8 |

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Fig. 1.

Cg-OxyR crystal structure shows a more symmetric subunit arrangement compared with the asymmetric relation between the RD and DBD homodimers of Pa-OxyR. (A) Crystal structure of tetrameric Pa-OxyR C199D [PDB ID code 4X6G (23)]. (B) Crystal structure of tetrameric Cg-OxyRC206S. (C) Overview of the Cg-OxyRC206S monomeric subunit, with the DBD and the RD highlighted.

Conserved Architecture of the OxyR Active-Site Pocket.

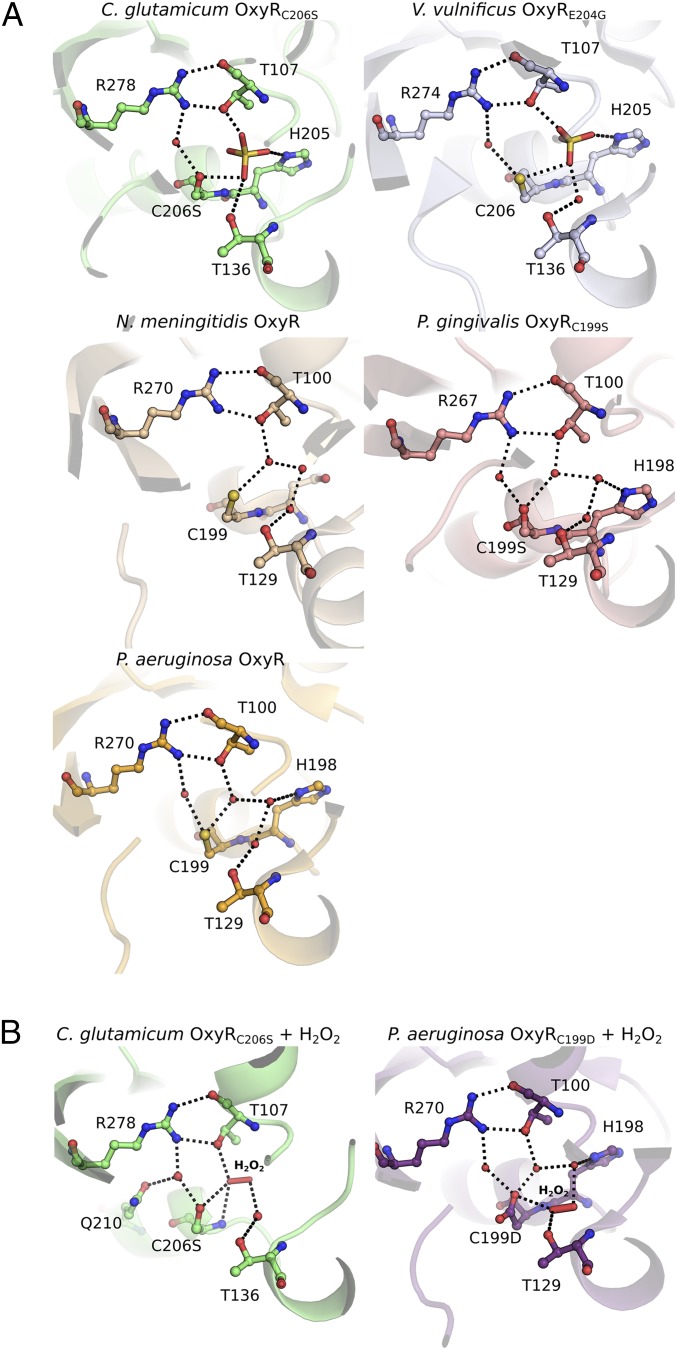

In the crystal structure of Cg-OxyRC206S, a sulfate molecule occupies the peroxidatic active-site pocket. This sulfate engages in hydrogen bonds with the side-chain hydroxyls of T107 and S206 (CP equivalent) and the side-chain amine of H205 (Fig. 2A). A sulfate molecule is also present in the crystal structure of V. vulnificus OxyR2 (Vv-OxyR2; PDB ID codes 5B7D and 5B7H), binding at an identical location and with the same hydrogen bond interactions (Fig. 2A) (25). In other OxyR structures, there is a conserved network of three water molecules within the active-site pocket instead of a sulfate molecule (PDB ID codes 3T22, 3JV9, and 4Y0M) (Fig. 2A) (22–26). This water pattern is conserved among these structures due to hydrogen bond interactions with side-chains of four conserved residues—T107, T136, H205, and C206—in Cg-OxyR (in N. meningitidis OxyR, H205 is substituted by Asn). Just outside of the active-site pocket, an additional conserved water molecule binds to both the side-chains of the CP (Ser in CP-mutant) and R278, the latter of which also contributes hydrogen bonds via its guanidinium group to the oxygens of the side-chain hydroxyl and backbone carbonyl of T107, an interaction that may play a role in stabilizing the position of T107 within the active-site architecture (Fig. 2A). Conservation of these active-site residues is demonstrated by a multiple sequence alignment of 67 OxyRs from different families (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). In particular, the CP and the R278 are universally conserved (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), while T107 is present in 97% of the sequences (substituted by a serine in the remaining 3%).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of Cg-OxyR active-site pocket with previously published structures. (A) OxyR structures show conservation of the active-site region. The active-site architecture from the OxyR crystal structures of C. glutamicum C206S (present study), V. vulnificus E204G OxyR2 [PDB ID code 5B7D (25)], N. meningitidis [PDB ID code 3JV9 (24)]*, P. gingivalis C199S [PDB ID code 3T22 (26)], and P. aeruginosa [PDB ID code 4Y0M (23)] are shown. (B) Comparison of the different H2O2 binding modes of the H2O2-soaked crystal structures of C. glutamicum OxyRC206S (present study) and P. aeruginosa C199D [PDB ID code 4X6G (23)]. Polar interactions between the residue side-chains and ligands (SO42−, H2O2) or water molecules (red spheres) are presented as dashed black lines. *The crystal structure of N. meningitidis OxyR contains two protein chains; in the active-site pocket of the alternate protein chain (not shown), the conserved water molecule which hydrogen bonds R270 is present but the conserved water molecule hydrogen bonding T129 is absent.

Crystallographic and Kinetic Evidence for H2O2 Binding and Reduction.

To better understand the role of these conserved residues in H2O2 binding and reduction at the molecular level, we soaked crystals of the redox-insensitive Cg-OxyRC206S with H2O2 to gain a peroxide-bound structure. Exposure of crystals of Cg-OxyRC206S to 600 mM H2O2 for 90 min enabled determination of a crystal structure of H2O2-bound Cg-OxyRC206S (hereafter referred to as Cg-OxyRH2O2) at a resolution of 2.6 Å in space group P21 (Table 1). Cg-OxyRH2O2 retains an overall tetrameric configuration close to that of Cg-OxyRC206S, with some minor subunit displacement. In all four respective active-site pockets of the Cg-OxyRH2O2 tetramer, the sulfate molecule is no longer present, and in two of the four pockets a molecule of H2O2 and a water molecule occupy a position equivalent to the sulfate (Fig. 2B). The structural architecture of the remaining two active-site pockets is disrupted by unfolding of the α3 helix of the RD (RDα3), where the CP and CR reside, into a loop. In both of the peroxide-bound pockets one oxygen of H2O2 (OA) accepts a hydrogen bond from the side-chain hydroxyl of T107 and the backbone amide of S206, and the other peroxide oxygen (OB) is bridged to the side-chain hydroxyl of T136 by a water molecule (Fig. 2B). The location of the H2O2 moiety in the active-site pocket is different to the one found in the C199D Pa-OxyR structure: in this structure, the OA peroxide oxygen establishes hydrogen bond contacts with the side-chain carboxyl of D199 and the side-chain hydroxyl of T129 (T136 in Cg-OxyR) (Fig. 2B) (23). The side-chain conformation of S206 is variable between the two H2O2-bound pockets, and in one pocket (hereafter referred to as “pocket A”) is directed away from the H2O2-containing active site, whereas in the other pocket (now referred to as “pocket B”) is directed toward H2O2 and would be within distance for a potential thiolate nucleophilic attack with the native cysteine (Fig. 3A).

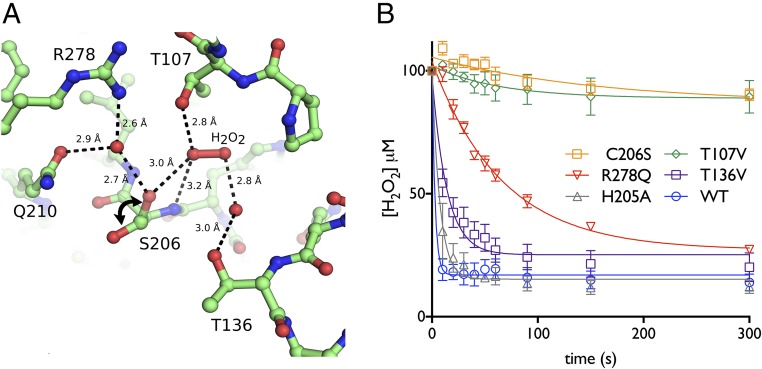

Fig. 3.

C206, T107, and R278 are the crucial residues for H2O2 catalysis. (A) In the crystal structure of Cg-OxyRH2O2, an H2O2 molecule occupies the active-site pocket in two of the four chains present in the asymmetric unit. Displayed is one of the two the H2O2 binding environments, termed pocket A (see Crystallographic and Kinetic Evidence for H2O2 Binding and Reduction). Here, the side-chain of S206 is directed away from the active site, whereas in pocket B, the side-chain of S206 is directed into the active site. Both conformations are displayed here, with a double-headed arrow indicating the rotameric change. The hydrogen-bonding network between H2O2, two conserved water molecules, and residues of the active site is expressed in terms of interatomic distances. (B) Mutation of the active-site residues impairs H2O2 reduction and supports the crystallographic data. WT Cg-OxyR and mutant variants (C206S, T107V, T136V, H205A, R278Q) were mixed with an equimolar amount of H2O2, and the H2O2 concentration was monitored in function of time with the FOX assay reagent. The lines correspond to single exponential fittings of the H2O2 consumption (n = 3). The error bars correspond to SD.

To explore the importance of the conserved active-site residues T107, T136, H205, C206, and R278 in peroxide reduction, single-residue variants (T107V, T136V, H205A, C206S, R278Q) were constructed, and H2O2 consumption was monitored in function of time using the ferrous oxidation of xylenol orange (FOX assay), which detects the H2O2 concentration in a given solution. While WT Cg-OxyR consumes the majority of H2O2 within 10 s, T107V and C206S variants are catalytically dead and only reduce minor amounts of H2O2 (Fig. 3B). The peroxidatic activity of the R278Q mutant is clearly affected, but not as dramatically as the T107V or C206S variants (Fig. 3B). The T136V variant shows impairment in H2O2 consumption to a lesser extent, and a H205A mutation has even less of an effect (Fig. 3B). The CR, C215, is not required for peroxidatic activity, because the C215S mutant shows no difference in H2O2 consumption compared with WT Cg-OxyR (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Taken together, the combination of structural and kinetic data points to a hierarchic contribution of four active-site residues for H2O2 binding and reduction in the following order of importance: C206, T107, R278, and T136.

Disulfide Bond Formation Reorganizes the OxyR Tetrameric Assembly.

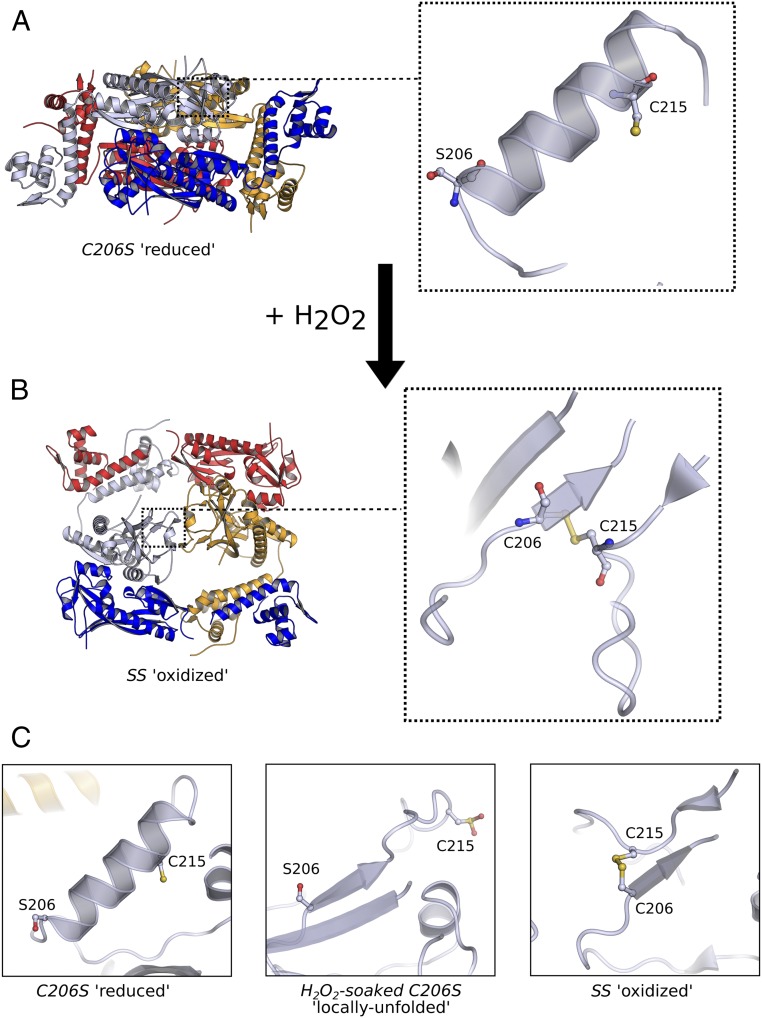

The crystal structure of the intramolecular disulfide-bonded form of Cg-OxyR (Cg-OxyRSS) was solved to a resolution of 2.3 Å in space group C2 (Table 1). The asymmetric unit cell contains two protomers of OxyR forming a RD-interfacing homodimer, which is one-half of the full tetramer related by crystallographic symmetry (Fig. 4A). The tetrameric oligomeric state of Cg-OxyRSS was confirmed by high-resolution size-exclusion chromatography, with some octameric subpopulation (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). As with Cg-OxyRC206S, the crystallographic tetramer of Cg-OxyRSS is a dimer of RD-interfaced homodimers with interhomodimer interactions predominating through respective DBD interfaces, although its overall tetrameric conformation differs significantly from that of Cg-OxyRC206S (Fig. 4A). The different oligomeric configurations adopted by Cg-OxyRC206S and Cg-OxyRSS arise predominantly from an asymmetric hinge motion of the loop connecting the DBD to the RD, resulting in a more square-like conformation for Cg-OxyRSS compared with the more rhomboid shape of Cg-OxyRC206S, with a shortening of the distance between DBDs of an RD homodimer from ∼117 Å in Cg-OxyRC206S to ∼96 Å in Cg-OxyRSS (Fig. 4A). Despite this significant oligomeric rearrangement, the interprotomer DBD interfaces are essentially conserved between the oxidized and reduced forms of OxyR (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B).

Fig. 4.

Cg-OxyR disulfide formation reorganizes its tetrameric conformation. (A) Crystal structure of reduced tetrameric Cg-OxyRC206S and a close-up view of the S206 and C215 of a single protomer (Right). (B) Crystal structure of the disulfide tetrameric Cg-OxyRSS, generated by crystallographic symmetry, with a close-up of the disulfide-bonded C206-C215 of a single protomer (Right). For both structures, each protomer is colored separately, and the RD homodimer formed by the blue and light-blue protomers were aligned before figure preparation, thereby providing a common orientation for structural comparison. (C) Each panel is a focused view of the relative positions of S206/C206 and C215 of the three crystal structures reported in this study. A structural alignment of all three structures was performed to provide a common orientation. The Left panel depicts the S206 and C215 of Cg-OxyRC206S, and is equivalent to the fully folded state of Cg-OxyRH2O2. The Center panel shows the locally unfolded state of Cg-OxyRH2O2, and the Right panel shows the C206-C215 disulfide of Cg-OxyRSS.

In both protein chains of the asymmetric unit, the CP (C206) and CR (C215) engage in a CP-CR intramolecular disulfide. This disulfide formation is facilitated by unfolding of the RDα3 helix, displacing the CP by 9.8 Å and CR by 7.4 Å (Cα-Cα), and resulting in the formation of a short β-strand from C206 to H208 (Fig. 4B). Of note, the unfolded conformation of the RDα3 helix is almost identical to that observed in Cg-OxyRH2O2 described above (Fig. 4C). These local conformational changes induce a subtle repacking of the hydrophobic core proximal to the peroxidatic site, causing allosteric structural changes at the RD homodimer interface, which translates into a cumulative 20° sliding rotation of the RD homodimer protomers. For a more in-depth discussion of the structural factors governing the localized conformational changes upon oxidation of Cg-OxyR, see SI Appendix.

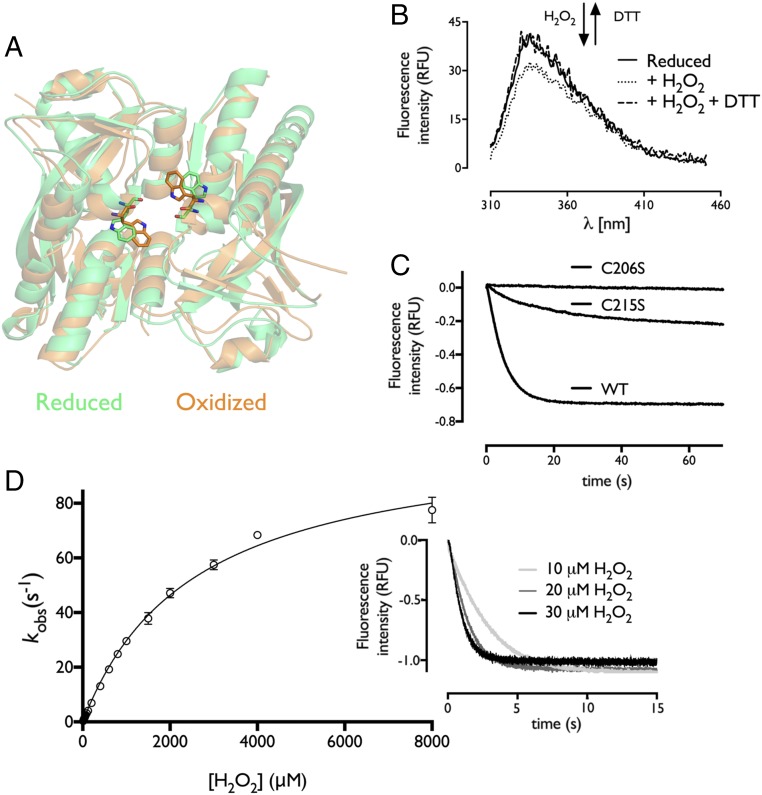

H2O2 Induces Rapid Intersubunit Rotation.

The single Trp of Cg-OxyR, W258, is located at the RD dimerization interface and shows a side-chain flip upon Cg-OxyR oxidation (Fig. 5A), which causes a decrease in the Trp-intrinsic fluorescence (Fig. 5B). This fluorescence decrease can be reverted upon addition of the reducing agent DTT (Fig. 5B). Motivated by this observation, we used the fluorescent read-out for a stopped-flow kinetic study. Upon H2O2 exposure, a rapid exponential fluorescence decrease was observed for WT Cg-OxyR RD (Fig. 5C). The C206S variant, which is peroxidatically inert, has almost no fluorescence decrease, while the C215S variant, which is peroxidatically active, shows a fluorescence decrease but lower than for WT Cg-OxyR (Fig. 5C). This further supports a mechanism in which CP-CR disulfide formation is required to lock the RD intersubunit rotation in Cg-OxyR, leading to a side-chain flip of W258. The progress curve for WT Cg-OxyR fits with an equation for a single exponential decay (Fig. 5D), and the observed rate constants of the progress curves correlate with the H2O2 concentration in a hyperbolic manner (Fig. 5D). Fitting the data to a hyperbolic equation [kobs = ([E0]kcat[H2O2])/(KM + [H2O2])] gives a kcat of 105.7 s−1 and a KM of 2.56 mM, resulting in a kcat/KM of 4.2 × 104 M−1s−1. Using the same approach, we also evaluated the kinetic impact on the T136V and H205A variants. These mutants did not show a single exponential fluorescence decrease upon H2O2 addition, but instead gave a single exponential increase in fluorescence, which, for the H205A variant, was preceded by a rapid decrease in fluorescence (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). It is possible that these mutations slightly reposition W258, which upon H2O2 addition affects the overall protein intrinsic fluorescence. For both H205A and T136V mutants, the observed rate constants of the fluorescence increase are linearly proportional to the H2O2 concentration (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). From the slope of the linear curve, a second-order rate constant for the reaction with H2O2 was obtained, yielding a rate of (1.06 ± 0.1) × 104 M−1s−1 for H205A and (5.18 ± 0.19) × 102 M−1s−1 for T136V (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), which is in good agreement with the results obtained from the FOX assay (Fig. 3B). For the R278Q variant, we were unable to determine the second-order rate constant via this approach. As an alternative, we used the FOX assay with a fixed H2O2 concentration while varying the concentration of R278Q Cg-OxyR. The H2O2 consumption profile followed a single exponential decrease, and the observed rate constant was linearly proportional to the concentration of R278Q Cg-OxyR (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), yielding a second-order rate constant of (1.79 ± 0.12) × 102 M−1s−1. A summary of the rate constants can be found in Table 2. Overall, Cg-OxyR exhibits a rapid conformational change upon oxidation, which is slowed by replacement of the conserved active-site residues.

Fig. 5.

Cg-OxyR shows rapid conformational changes upon oxidation. (A) Structural view of the tryptophan location and its side-chain flip upon oxidation. (B) The side-chain flip leads to a decrease in intrinsic fluorescence. Fluorescence spectroscopy of Cg-OxyR upon oxidation by H2O2 and rereduction by DTT. (C) Cg-OxyR requires both cysteines for the full conformational change. One micromolar WT and C206S/C215S variants were mixed with 5 μM H2O2, and fluorescence decrease was monitored over time in a stopped-flow mixing device. (D) The conformational change rate increases with H2O2 concentration in a hyperbolic manner. Increasing concentrations of H2O2 were added to Cg-OxyR. The progress curves were fitted to single exponential equation, and the observed rate constants plotted against the H2O2 concentration (n = 3). Inset shows the progress curves of Cg-OxyR fluorescence changes upon addition of 10, 20, or 30 μM H2O2.

Table 2.

Second-order rate constants of OxyR reaction with H2O2 (pH 7.4, 25 °C)

| OxyR variant | k (M−1s−1) |

| WT | 4.20 × 104 |

| H205A | 1.06 × 104 |

| T136V | 5.18 × 102 |

| R278Q | 1.79 × 102 |

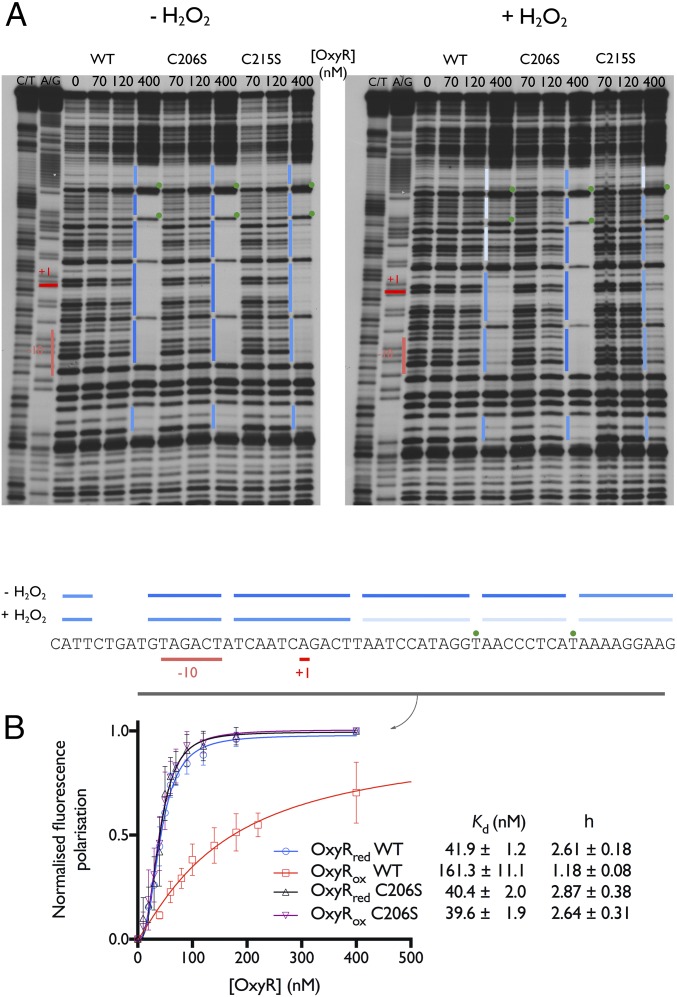

Disulfide-Bonded Cg-OxyR Shifts Its DNA-Binding Pattern at the Catalase Regulatory Region.

Contrary to the conventional E. coli model of OxyR as a transcriptional activator, the OxyRs of Corynebacterium diphtheriae and C. glutamicum are thought to act as transcriptional repressors (27, 29). It has been demonstrated that the oxidized, intramolecular disulfide-bonded form of Cg-OxyR is less specific in its binding to the four promoter regions, katA, dps, ftn, and cydA relative to reduced Cg-OxyR, and that in vivo bacterial exposure to H2O2 leads to induction of katA and dps, but not ftn and cydA (27). We aimed to assess the relationship between the oxidation state of Cg-OxyR and its ability to bind to the catalase (katA) operator/promoter region. Using EMSA, we found that both oxidized and reduced Cg-OxyR bind to the catalase operator/promoter region, and this with no apparent difference in the electrophoretic mobility of the Cg-OxyR-DNA complex (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). We found that only the DBDs bind to the katA regulatory region, because a Cg-OxyR RD-only variant does not show any interaction (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Next, to determine the exact Cg-OxyR binding region, we performed DNase I footprinting experiments, and observed that reduced Cg-OxyR protects a section corresponding to approximately four consecutive helical turns, which includes the −10 promoter element and the transcription start point (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, disulfide-bonded Cg-OxyR retained binding to the −10 promoter element, but the last two helical turns were no longer protected from the DNase I treatment (Fig. 6A). The Cg-OxyRC206S variant protected the same katA regulatory region as reduced WT Cg-OxyR, whereas reduced CR mutant (Cg-OxyRC215S) displayed slightly less protection of the binding region in comparison with reduced WT or Cg-OxyRC206S (Fig. 6A). Treatment of Cg-OxyRC215S with H2O2 causes a uniform decrease of protection on the whole binding region, whereas protection by H2O2-treated Cg-OxyRC206S was unaffected (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Cg-OxyR oxidation decreases binding affinity and extension to the catalase promoter region. (A) DNase I footprint of the C. glutamicum catalase promoter/operator region in presence of WT or C206S/C215S CgOxyR, and under reducing (Left) or oxidizing (Right) conditions. A C/T and A/G sequencing ladder and a no Cg-OxyR control were added in each condition. Binding regions are highlighted in blue, with the binding affinity being proportional to the color intensity. The nucleotides that are hypersensitive to DNase I treatment in presence of OxyR are marked by a green dot. The transcription start point (+1) is highlighted in red, and the −10 region is highlighted in salmon. A summary of the binding experiments is shown below. (B) Fluorescence polarization experiments using a 6-FAM–labeled oligonucleotide containing the catalase binding region (highlighted in gray in A). The labeled oligonucleotide was mixed with increasing concentrations of WT/C206S Cg-OxyR, under reducing or oxidizing conditions, until reaching binding saturation (n = 3).

To determine the affinity of the Cg-OxyR variants toward the protected region of the katA promoter, we measured binding to a 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)–labeled katA promoter oligonucleotide by fluorescence polarization, whereby binding of OxyR to the oligonucleotide increases the fluorescence polarization. Reduced WT Cg-OxyR, and reduced and H2O2-treated Cg-OxyRC206S gave similar affinities (∼40 nM) for the oligonucleotide and bound with strong positive cooperativity (h = 2.6–2.8) (Fig. 6B), whereas oxidized WT Cg-OxyR had a fourfold lower binding affinity (∼160 nM) with almost no cooperativity (h = 1.2) (Fig. 6B). Isothermal titration calorimetry of the interaction between Cg-OxyR and the katA promoter showed that binding of the katA promoter to reduced Cg-OxyR occurs with a higher affinity than that observed for binding to oxidized Cg-OxyR, and displays an initial exothermic binding step not observed for oxidized Cg-OxyR (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C).

Next, to identify the nitrogenous bases of the katA promoter that are directly involved in the binding to reduced and/or oxidized Cg-OxyR, missing contact probing experiments were performed. These experiments involve addition of Cg-OxyR to sparingly modified depurinated/depyrimidinated DNA (on average one modification per molecule), followed by separation of the free DNA and protein-bound forms on an acrylamide gel, cleavage of the DNA backbone at the modified positions, and separation of the reaction products by gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions. If a base is essential to Cg-OxyR binding, DNA molecules missing this base will be underrepresented in the bound DNA form and overrepresented in the free DNA form (30). Initially, the missing contact probing was tested with oxidized WT Cg-OxyR and with the redox-insensitive C206S variant, Cg-OxyRC206S. However, it was observed that the complex between Cg-OxyRC206S and DNA gave a totally different electrophoretic mobility pattern on the acrylamide gel compared with the WT Cg-OxyR–DNA complex (SI Appendix, Fig. S6D), and so for this reason we decided not to use the Cg-OxyRC206S variant for this experiment. For reduced WT Cg-OxyR, we found two binding regions, each 11- to 13-nucleotides long and separated by 6 nucleotides (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Both reduced and oxidized Cg-OxyR specifically bound the upstream binding region, which contains the −10 promoter element, and is immediately upstream of the transcription start point, but the oxidized form of Cg-OxyR was no longer able to specifically interact with the downstream binding region (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

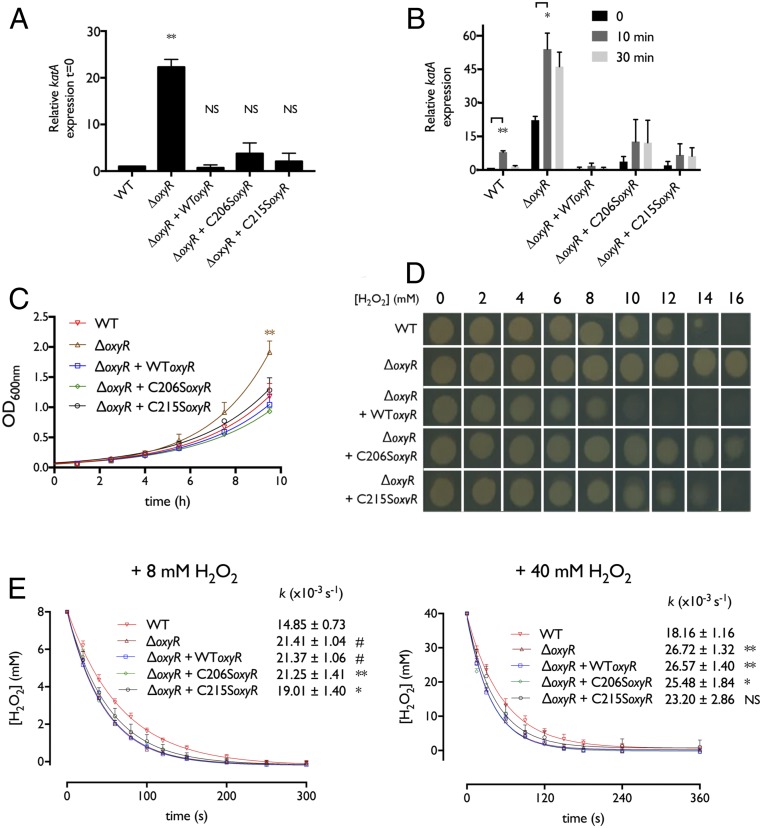

Cg-OxyR Is a Repressive Gatekeeper of Catalase Expression.

Because Cg-OxyR binds to the catalase regulatory region in a manner dependent on its oxidation state, we explored the C. glutamicum response to H2O2 stress by evaluating the regulation of catalase transcription. Under basal conditions, a ΔoxyR strain of C. glutamicum displayed a massive increase of the katA mRNA levels, ∼20-fold higher than in the WT strain, indicating that Cg-OxyR represses katA transcription (Fig. 7A and SI Appendix, Table S2). In agreement with this, complementation of ΔoxyR with overexpressed WT Cg-OxyR (which displays an ∼20-fold increase of the oxyR mRNA level) (SI Appendix, Table S3) led to a great decrease in katA expression (as expected), equivalent to the one described for the WT strain (Fig. 7A and SI Appendix, Table S2). In contrast, complementation with C206S or C215S oxyR increased katA expression compared with the WT strain (∼two- to fourfold) (Fig. 7A and SI Appendix, Table S2).

Fig. 7.

Cg-OxyR controls catalase transcription, recovery from lag phase, survival to H2O2 stress, and H2O2 scavenging rate. (A) katA mRNA levels under normal conditions in the different C. glutamicumstrains (n = 3). (B) katA mRNA levels in the different C. glutamicum strains after 10 or 30 min upon a 10 mM H2O2 challenge (n = 3). (C) Growth curves for the different C. glutamicum strains (n = 3). (D) In vivo resistance to H2O2. The different Cg-OxyR strains were spotted on agar plates containing increasing concentrations of H2O2, and growth was evaluated. (E) H2O2 consumption rates. An 8-mM (Left) or 40-mM (Right) H2O2 bolus was added to growing cultures of the Cg-OxyR strains, and the H2O2 concentration decrease was monitored in function of time using the FOX reagent (n = 3). Samples were statistically compared with Student’s t test when indicated (NS, not significant; *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01; #P < 0.005).

We also evaluated the fluctuations of katA mRNA levels in response to externally applied H2O2 for the same strains ± complementation. In all cases, katA expression increases 10 min after a H2O2 bolus, although the degree of increase in expression varied greatly depending on the strain/complementation, with the WT strain giving an 8-fold up-regulation, the ΔoxyR strain a 2.5-fold up-regulation, and the ΔoxyR with WT oxyR complementation a 2.2-fold up-regulation, having the lowest katA mRNA levels upon H2O2 treatment (Fig. 7B and SI Appendix, Table S2). On the other hand, a ΔoxyR strain with C206S/C215S oxyR complementation exhibited an ∼threefold increase (albeit nonsignificant) of katA up-regulation under H2O2 stress (Fig. 7B and SI Appendix, Table S2). After 30 min of H2O2 stress, the katA mRNA levels returned to basal levels in strains containing WT OxyR (WT, ΔoxyR + WT oxyR), while the other strains still maintained increased katA expression (Fig. 7B and SI Appendix, Table S2).

The bacterial fitness of each strain against oxidative stress was also assessed. It has been previously reported that during the latency (“lag”) phase of bacterial growth, genes of the oxyR regulon are up-regulated (31), bacteria are more sensitive to H2O2 (31), and the presence or supplementation of catalase to the growth media shortens this lag phase (3, 32). Consistent with this finding, the ΔoxyR strain, which overexpresses catalase, shows a shorter lag phase compared with the oxyR-containing strains (Fig. 7C). In accordance with previous studies (10, 27) we also observed an increase of resistance against exogenous H2O2 in the ΔoxyR strain (Fig. 7D). Complementation with overexpressed WT Cg-OxyR renders the strain more sensitive to H2O2, while complementation with C206S oxyR gives the second-most resistant phenotype (after ΔoxyR), and complementation with C215S oxyR has no effect (Fig. 7D). We also evaluated the in vivo H2O2-consumption kinetics of C. glutamicum upon application of a H2O2 bolus (8 or 40 mM). For both tested concentrations, the WT strain was the slowest in consuming H2O2, followed by the ΔoxyR + C215S oxyR and ΔoxyR + C206S oxyR strains (Fig. 7E). Strains lacking OxyR or complemented with overexpressed WT Cg-OxyR were the fastest in scavenging single doses of H2O2 (Fig. 7E). All in all, these results indicate that catalase up-regulation allows C. glutamicum to survive persistent oxidative conditions.

Discussion

The generation of reactive oxidants is key for the defense of the host against pathogenic invasion. As the frontline sensor and coordinator of the bacterial response to the oxidant H2O2, OxyR drives the survival of many pathogenic organisms (9–12, 14–19). Its efficacy of defensive coordination depends on the ability to sense intracellular H2O2 before it reaches a concentration that inhibits bacterial growth (1, 3).

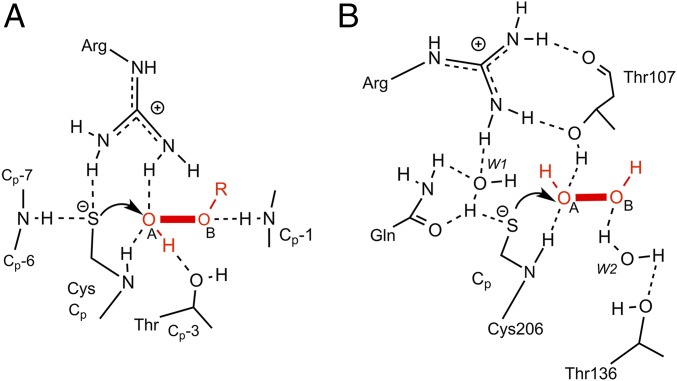

Here we show that the H2O2-sensing capacity of OxyR relies mainly on three conserved residues (T107/C206/R278 in Cg-OxyR), and that water molecules in the active-site pocket likely play a supplementary role in proton transfer. We find a conserved water placement among the peroxidatic pockets of multiple OxyRs, and a close match between the location of conserved waters and the respective positions of the OA and OB in the H2O2-bound structure (5). Because the CP of both OxyR and Prdx facilitate peroxide reduction at rates several orders-of-magnitude greater than that for a typical protein thiol, key insights can be gained from comparison of the contribution of the respective residues in active-site environments (Fig. 8). In both cases, hydrogen-bonding interactions are predominantly formed at OA over OB, and whereas the CP thiolate of Prdx is stabilized by hydrogen bond donation from an arginine guanidinium group, we propose that in OxyR this hydrogen bond instead comes from a water molecule bridging R278 and Q210. For both Prdx and OxyR, a conserved Thr plays a critical role in providing a hydrogen bond to the peroxide OA (Fig. 8; see SI Appendix for further discussion of the molecular architecture of H2O2 binding in Cg-OxyRH2O2). Our study shows the essential nature of T107 hydroxyl group for H2O2 reduction by Cg-OxyR, a finding supported by the previous observation that a T100V (equivalent to T107 in Cg-OxyR) but not a T100S mutation in Pa-OxyR induces cellular H2O2 hypersensitivity (23). In Cg-OxyR, mutating R278 also impairs H2O2 reduction, and we postulate that R278 scaffolds the active-site architecture by correctly positioning T107 for its catalytic role (Fig. 8). Based on these results, we propose that OxyR possess a core triad (T/C/R) for H2O2 reduction.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of H2O2 reduction mechanism by OxyR and Prdx. Schematic drawing of the Prdx peroxide-bound active site (A) [reprinted from ref. 5. Copyright (2010), with permission from Elsevier] in comparison with the OxyR active site (B). The key hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) that allow for H2O2 reduction are highlighted.

Following reduction of H2O2 at the CP of OxyR, unfolding of the RDα3 helix is required to bring the CP-SOH and CR into close proximity for condensation to a CP-CR disulfide. In the crystal structure of Cg-OxyRH2O2, two of the four active sites of the tetramer are apo with the RDα3 unfolded, placing S206 in a position equivalent to the disulfide-engaged C206 (Fig. 4C). This shows that Cg-OxyR can adopt a locally unfolded state without the prerequisite of CP sulfenylation, and a similar observation has been made in the structure of C199D Pa-OxyR (23). In Prdxs, a local unfolding of the CP environment is a well-known phenomenon, and it is associated with an inherent equilibrium between the fully-folded (FF) and locally-unfolded (LU) conformations of the active site (33). Our data suggest that the OxyR CP environment is also subject to FF/LU conformational dynamics, and it is very likely that a FF/LU equilibrium regulates the peroxidatic power of OxyR and susceptibility to CP hyperoxidation. Active-site conformational dynamics have also been observed in a comparative study of Vv-OxyR1 and Vv-OxyR2 (25). Whereas in the majority of OxyRs, the active site His (H205 in C. glutamicum and V. vulnificus) is preceded by a Gly (G204), in Vv-OxyR2 this Gly is substituted with a Glu (G204E), which is proposed to reduce the conformational flexibility of the active site. Due to this active-site rigidity, Vv-OxyR2 reduces H2O2 twofold faster than its counterpart Vv-OxyR1 (which contains G204), but it is more susceptible to CP hyperoxidation (25). Despite sharing no conserved structural features, it is intriguing to see that both OxyR and Prdx adopted a similar structural dynamic mechanism.

Here we report a significant rearrangement of the tetrameric assembly of Cg-OxyR upon oxidation, yet with localized structural change restricted to the RD subunits only, and the DBDs remaining unaltered in conformation. The observed shortening of the distance between respective DBD dimer pairs of the oxidized tetramer relative to the reduced form validates the previously hypothesized mechanistic models of oxidative regulation of OxyR in its capacity as a transcription factor (23, 34). See SI Appendix for a hypothesis of how localized structural changes upon CP-CR formation in Cg-OxyR drive the transition between the reduced and oxidized tetrameric assemblies. Importantly, these structural changes that occur upon Cg-OxyR oxidation translate into changes in DNA binding topology and affinity. We show that in the absence of oxidizing stimuli, Cg-OxyR binds to the catalase promoter/operator region at two distinct binding sites upstream and downstream of the katA transcription start point. Upon oxidation, Cg-OxyR loses its interaction with the downstream binding site, and this is further reflected by a reduction in overall affinity and allosteric cooperativity of the binding association between oxidized OxyR and the katA promoter. This is opposite to what has been found for the redox-dependent binding of Ec-OxyR to the katA regulatory region, where the binding affinity increases upon oxidation (34). Although Cg-OxyR oxidation causes loss of binding to the second site, the electrophoretic mobility of the Cg-OxyR–DNA complex is not affected by its redox state (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A), thereby indicating that the same number of Cg-OxyR subunits is associated with the katA regulatory region, regardless of its oxidation state. Furthermore, the decrease in binding cooperativity under reducing conditions suggests that the four DBDs of the Cg-OxyR tetramer bind to the katA regulatory region (two in each binding region), whereas Cg-OxyR oxidation causes a conformational change that leads to the dissociation of two DBDs from the downstream binding region. Because oxidized Cg-OxyR still binds to the −10 promoter element of katA, we can expect a positive interaction between oxidized Cg-OxyR and the RNA polymerase, whereas the extended contacts made with reduced Cg-OxyR might inhibit transcription initiation.

C. glutamicum strains lacking OxyR are more resistant to H2O2 stress, due to catalase derepression (10, 27). Catalase levels are required to survive H2O2 stress, as demonstrated in C. glutamicum and C. diphtheriae strains lacking katA, which are hypersensitive to H2O2 (27, 29). We confirm that catalase up-regulation not only improves resistance against elevated H2O2 concentrations, but also shortens the growth lag phase and increases the rate of H2O2 consumption. The strain of C. glutamicum overexpressing Cg-OxyR (ΔoxyR + WT Cg-oxyR) exhibits the lowest catalase levels and the lowest survival to sustained H2O2 stress. Under resting conditions, both WT and Cg-OxyR–overexpressing strains show similar repression of katA transcription, but under H2O2 treatment, the strain overexpressing Cg-OxyR exhibits even lower katA mRNA levels, as others have previously observed (27). This likely explains the increased sensitivity of this strain to H2O2 stress. Despite all this, the strain overexpressing Cg-OxyR has one of the highest H2O2 scavenging rates after a single H2O2 bolus. An explanation for this behavior is that OxyR itself is rapidly consuming H2O2, thereby acting as a kind of short-term scavenger. However, OxyR is not a real H2O2 scavenger, as the rereduction kinetics of OxyR are too slow to maintain a defense response during prolonged oxidative stress conditions. A H2O2 bolus in E. coli and V. vulnificus causes OxyR oxidation in 30 s, but it takes 5–10 min for OxyR to be rereduced (19, 35).

In summary, this study provides in vivo evidence for H2O2-dependent transcriptional derepression by Cg-OxyR, and for redox-dependent associations with cognate DNA. With in-depth crystallographic and biochemical analyses, we uncovered the molecular mechanism of hydrogen peroxide sensing by OxyR. OxyR employs a disulfide-driven allosteric structural change at its RD interface. The obtained structural and mechanistic insights might further steer the design of H2O2-sensing inhibitors and guide the optimization of a new generation of HyPer-like redox biosensors.

Methods

Crystallization and X-Ray Diffraction.

All crystals of Cg-OxyR were obtained using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method at 283 K. Cg-OxyRC206S was crystallized by mixing 1.5 μL of protein [3 mg mL−1 in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, and 2 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP)] with 1.5 μL of 25% PEG 4000, 0.1 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (Mes), pH 6.2, 0.125 M lithium sulfate, 3% 1,6-hexanediol, and 2 mM TCEP. Crystals were cryoprotected by addition of 16% ethylene glycol, 10% glycerol, 10% propanediol, and 2 mM TCEP and flash-frozen. Diffraction data were collected at the PROXIMA-2A beamline of SOLEIL synchrotron at 100 K and a wavelength of 0.98 Å.

To obtain a H2O2-bound protein crystal, 1.65 μL of artificial mother liquor containing an increased concentration of PEG (30% PEG 4000, 0.1 M Mes, pH 6.2, 0.125 M lithium sulfate) was added to a ∼3.3 μL crystallization droplet of OxyRC206S, prepared as described above, followed by direct addition of 0.5 μL 6.6 M H2O2 (to give a final [H2O2] of ∼600 mM) and incubated at 283 K for 90 min. Crystals were flash-frozen and diffraction data collected at beamline I24 of the Diamond Light Source synchrotron at 100 K and a wavelength of 1.0 Å.

Crystals of Cg-OxyRSS were obtained by mixing 1.5 μL of protein (2.5 mg mL−1) with 1.5 μL of 13% PEG 4000, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, 0.1 M magnesium acetate and 10 mM β-Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrate. Crystals were cryoprotected by addition of 20% ethylene glycol, 15% sucrose, and 15% 3-(1-Pyridinio)-1-propanesulfonate and flash-frozen. Diffraction data were collected at the ID30B beamline of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility at 100 K and a wavelength of 0.954 Å.

All diffraction data reduction was performed in XDS (36) and merging of intensities in AIMLESS (37). Phases for OxyRC206S were determined by molecular replacement using Phaser (38) with full-length P. aeruginosa C199D OxyR (PDB ID code 4X6G) as a search model (23), and the full-length model or RD homodimer of OxyRC206S used as a search model in molecular replacement for OxyRH2O2 and OxyRSS respectively. Atomic coordinates were manually corrected in COOT (39), and the final maximum-likelihood refinement performed in PHENIX (40). Molecular geometry was validated using MolProbity (41), and the Ramachandran outliers for OxyRC206S, OxyRH2O2, and OxyRSS were 0.08%, 0.17%, and 0% respectively. X-ray data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. For a discussion of ligand assignment/fitting to residual density, we direct readers to the SI Appendix. All structural figures were prepared in PyMOL. Oligomeric assemblies of crystal structures were verified using PISA (42).

Methods describing stopped-flow analysis, FOX assay, DNA-binding experiments, generation of mutant strains, transcriptional analysis, and in vivo resistance to H2O2 are described in detail in SI Appendix, Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank “Iniciativa de Empleo Juvenil” from both “Junta de Castilla y León” (L.M.-P.) and the Spanish Ministry “MINECO” (Á.M.) for technical assistance; and the scientists at the PROXIMA 2-A beamline of the SOLEIL synchrotron and at the ID30B beamline of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. This work was made possible thanks to financial support from Vlaams Instituut voor Biotechnologie; an Institute for Innovation by Science and Technology (IWT) doctoral fellowship (to B.P.); equipment Grant HERC16 from the Hercules foundation (to J.M.); Research Foundation Flanders Grant FWO G.0D79.14N (to J.M.); Research Foundation Flanders Excellence of Science Project 30829584 (to J.M.); the Erasmus Internship Program (to A.G.d.l.R.); and Strategic Research Programme SRP34 of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (to J.M.); Russian Science Foundation Grant 17-14-01086 (to V.V.B.); and “Junta de Castilla y León; LE326U14” and “University of León; UXXI2016/00127” Projects (to L.M.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.wwpdb.org (PDB ID codes 6G1D, 6G4R, and 6G1B).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1807954115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Imlay JA. The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: Lessons from a model bacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:443–454. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sies H. Hydrogen peroxide as a central redox signaling molecule in physiological oxidative stress: Oxidative eustress. Redox Biol. 2017;11:613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seaver LC, Imlay JA. Hydrogen peroxide fluxes and compartmentalization inside growing Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:7182–7189. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7182-7189.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winterbourn CC. The biological chemistry of hydrogen peroxide. Methods Enzymol. 2013;528:3–25. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405881-1.00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall A, Parsonage D, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Structural evidence that peroxiredoxin catalytic power is based on transition-state stabilization. J Mol Biol. 2010;402:194–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portillo-Ledesma S, et al. Deconstructing the catalytic efficiency of peroxiredoxin-5 peroxidatic cysteine. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6113–6125. doi: 10.1021/bi500389m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flohé L, Toppo S, Cozza G, Ursini F. A comparison of thiol peroxidase mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:763–780. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee C, et al. Redox regulation of OxyR requires specific disulfide bond formation involving a rapid kinetic reaction path. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1179–1185. doi: 10.1038/nsmb856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei Q, et al. Global regulation of gene expression by OxyR in an important human opportunistic pathogen. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4320–4333. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milse J, Petri K, Rückert C, Kalinowski J. Transcriptional response of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 to hydrogen peroxide stress and characterization of the OxyR regulon. J Biotechnol. 2014;190:40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.07.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng M, et al. DNA microarray-mediated transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli response to hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4562–4570. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.15.4562-4570.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alanazi AM, Neidle EL, Momany C. The DNA-binding domain of BenM reveals the structural basis for the recognition of a T-N11-A sequence motif by LysR-type transcriptional regulators. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:1995–2007. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913017320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau GW, Britigan BE, Hassett DJ. Pseudomonas aeruginosa OxyR is required for full virulence in rodent and insect models of infection and for resistance to human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2550–2553. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2550-2553.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sund CJ, et al. The Bacteroides fragilis transcriptome response to oxygen and H2O2: The role of OxyR and its effect on survival and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:129–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flores-Cruz Z, Allen C. Necessity of OxyR for the hydrogen peroxide stress response and full virulence in Ralstonia solanacearum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:6426–6432. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05813-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bae HW, Cho YH. Mutational analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa OxyR to define the regions required for peroxide resistance and acute virulence. Res Microbiol. 2012;163:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JR, et al. OxyR contributes to the virulence of a clonal group A Escherichia coli strain (O17:K+:H18) in animal models of urinary tract infection, subcutaneous infection, and systemic sepsis. Microb Pathog. 2013;64:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu C, et al. OxyR-regulated catalase CatB promotes the virulence in rice via detoxifying hydrogen peroxide in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:269. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0887-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S, et al. Distinct characteristics of OxyR2, a new OxyR-type regulator, ensuring expression of Peroxiredoxin 2 detoxifying low levels of hydrogen peroxide in Vibrio vulnificus. Mol Microbiol. 2014;93:992–1009. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belousov VV, et al. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat Methods. 2006;3:281–286. doi: 10.1038/nmeth866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bilan DS, Belousov VV. HyPer family probes: State of the art. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;24:731–751. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi H, et al. Structural basis of the redox switch in the OxyR transcription factor. Cell. 2001;105:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jo I, et al. Structural details of the OxyR peroxide-sensing mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:6443–6448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424495112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sainsbury S, et al. The structure of a reduced form of OxyR from Neisseria meningitidis. BMC Struct Biol. 2010;10:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jo I, et al. The hydrogen peroxide hypersensitivity of OxyR2 in Vibrio vulnificus depends on conformational constraints. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:7223–7232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.743765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svintradze DV, Peterson DL, Collazo-Santiago EA, Lewis JP, Wright HT. Structures of the Porphyromonas gingivalis OxyR regulatory domain explain differences in expression of the OxyR regulon in Escherichia coli and P. gingivalis. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:2091–2103. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913019471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. OxyR acts as a transcriptional repressor of hydrogen peroxide-inducible antioxidant genes in Corynebacterium glutamicum R. FEBS J. 2013;280:3298–3312. doi: 10.1111/febs.12312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christman MF, Storz G, Ames BN. OxyR, a positive regulator of hydrogen peroxide-inducible genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, is homologous to a family of bacterial regulatory proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3484–3488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JS, Holmes RK. Characterization of OxyR as a negative transcriptional regulator that represses catalase production in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunelle A, Schleif RF. Missing contact probing of DNA-protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6673–6676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolfe MD, et al. Lag phase is a distinct growth phase that prepares bacteria for exponential growth and involves transient metal accumulation. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:686–701. doi: 10.1128/JB.06112-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Follmann M, et al. Functional genomics of pH homeostasis in Corynebacterium glutamicum revealed novel links between pH response, oxidative stress, iron homeostasis and methionine synthesis. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:621. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perkins A, et al. The sensitive balance between the fully folded and locally unfolded conformations of a model peroxiredoxin. Biochemistry. 2013;52:8708–8721. doi: 10.1021/bi4011573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toledano MB, et al. Redox-dependent shift of OxyR-DNA contacts along an extended DNA-binding site: A mechanism for differential promoter selection. Cell. 1994;78:897–909. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tao K. In vivo oxidation-reduction kinetics of OxyR, the transcriptional activator for an oxidative stress-inducible regulon in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1999;457:90–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans PR, Murshudov GN. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:1204–1214. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr Sect Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.