Significance

G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling from the extracellular orthosteric drug binding site across the cell membrane to the intracellular contact sites with G proteins and arrestins is enabled by inherent structural plasticity, which can be observed by NMR spectroscopy. Here, we use 19F-NMR to characterize ensembles of different, simultaneously populated conformations of the human A2A adenosine receptor in function-related equilibria. The NMR data support an activation model involving both induced fit and reequilibration of conformational ensembles, and experiments with a constitutively active mutant of A2A adenosine receptor (A2AAR) established correlations between NMR parameters and GPCR basal activity. The present quantitative measurements with observation of judiciously engineered 19F-NMR probes complement a previous qualitative overall view of A2AAR dynamics from high-resolution NMR.

Keywords: NMR spectroscopy, GPCR, adenosine receptor, signaling, dynamics

Abstract

The human proteome contains 826 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), which control a wide array of key physiological functions, making them important drug targets. GPCR functions are based on allosteric coupling from the extracellular orthosteric drug binding site across the cell membrane to intracellular binding sites for partners such as G proteins and arrestins. This signaling process is related to dynamic equilibria in conformational ensembles that can be observed by NMR in solution. A previous high-resolution NMR study of the A2A adenosine receptor (A2AAR) resulted in a qualitative characterization of a network of such local polymorphisms. Here, we used 19F-NMR experiments with probes at the A2AAR intracellular surface, which provides the high sensitivity needed for a refined description of different receptor activation states by ensembles of simultaneously populated conformers and the rates of exchange among them. We observed two agonist-stabilized substates that are not measurably populated in apo-A2AAR and one inactive substate that is not seen in complexes with agonists, suggesting that A2AAR activation includes both induced fit and conformational selection mechanisms. Comparison of A2AAR and a constitutively active mutant established relations between the 19F-NMR spectra and signaling activity, which enabled direct assessment of the difference in basal activity between the native protein and its variant.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are cell surface sensory proteins that recognize a vast array of extracellular stimuli and form signaling complexes with intracellular partner proteins that drive physiological responses. Approximately 35% of all FDA-approved drugs target human GPCRs, and development of new GPCR drugs shows no signs of slowing down (1). Drug development is supported by both 3D structures of GPCRs and GPCR complexes obtained by X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM and by knowledge about their dynamic structural plasticity gained using other biophysical methods such as NMR spectroscopy. NMR in solution possesses the unique ability to observe multiple, simultaneously populated GPCR conformers, establish relations between their populations and the efficacies of bound drugs, and thus provide direct insight into dynamic processes that underlie physiological GPCR signaling.

In this study, we apply 19F-NMR to refine our understanding of signaling mechanisms in the human A2A adenosine receptor (A2AAR). A2AAR functions have been studied in the central nervous system as a key modulator of neurotransmitters (2), in the cardiovascular system as regulating vasodilation (3), and in the immune system as a T-cell surface immune checkpoint protein (4). Correspondingly, A2AAR has been targeted for various diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (5) and depression (6), and new drugs are under development for cancer therapies (7, 8). To gain a deeper understanding of A2AAR functionality, X-ray crystal structures have been reported for its complexes with antagonists (9–12) and agonists (13, 14) and for a ternary complex with an agonist and a “mini G protein” (15). The extensive data on structure and function now provide a foundation for other biophysical techniques to provide complementary insights into the signaling mechanisms. Here we used NMR spectroscopy in solution.

In earlier high-resolution NMR studies of stable-isotope–labeled A2AAR, NMR observations afforded a global view of structural plasticity throughout the 3D structure, and changes in conformational equilibria could be related to variable drug efficacies and to inactivation of an allosteric switch (16, 17). To characterize these structure ensembles in greater detail and to quantify rates of exchange among the different conformers, we now used 19F-NMR with single extrinsic probes judiciously placed in positions at the intracellular tips of the transmembrane helices (TM) VI, VII, and VIII. The increased sensitivity of this 19F-NMR approach relative to 2D heteronuclear correlation experiments permitted quantitative measurements of drug efficacy-related changes in the populations of multiple conformers and the exchange rates among them. The results obtained will be placed in context with data collected using different 19F-NMR probes positioned differently in the A2AAR structure (18, 19) and by 13C-methyl NMR of selectively labeled isoleucine residues on a deuterated background (20).

Results

Selecting Locations for 19F-NMR Probes in A2AAR.

The chemical reaction used here for the introduction of 19F-groups targets cysteine side chains via a disulfide bond formation. Wild-type AA2AR contains 14 cysteines, of which 8 are in disulfide bonds and thus protected from the chemical reagent. In the 3D structure of AA2AR, the remaining six cysteine residues are located in the membrane interior and therefore also inaccessible for chemical reagents, provided that the technique of in-membrane chemical modification (IMCM) (21) is used for the introduction of the NMR probes. Without the need for other amino acid replacements, 19F-NMR reporter groups could thus be introduced by design into locations near the intracellular surface, where their possible response to ligand-induced conformational rearrangements can provide insights into the mechanisms enabling the physiological signaling by AA2AR. Cys residues were thus engineered into three such locations and then reacted with 2,2,2-trifluoroethanethiol (TET), yielding CTET (22).

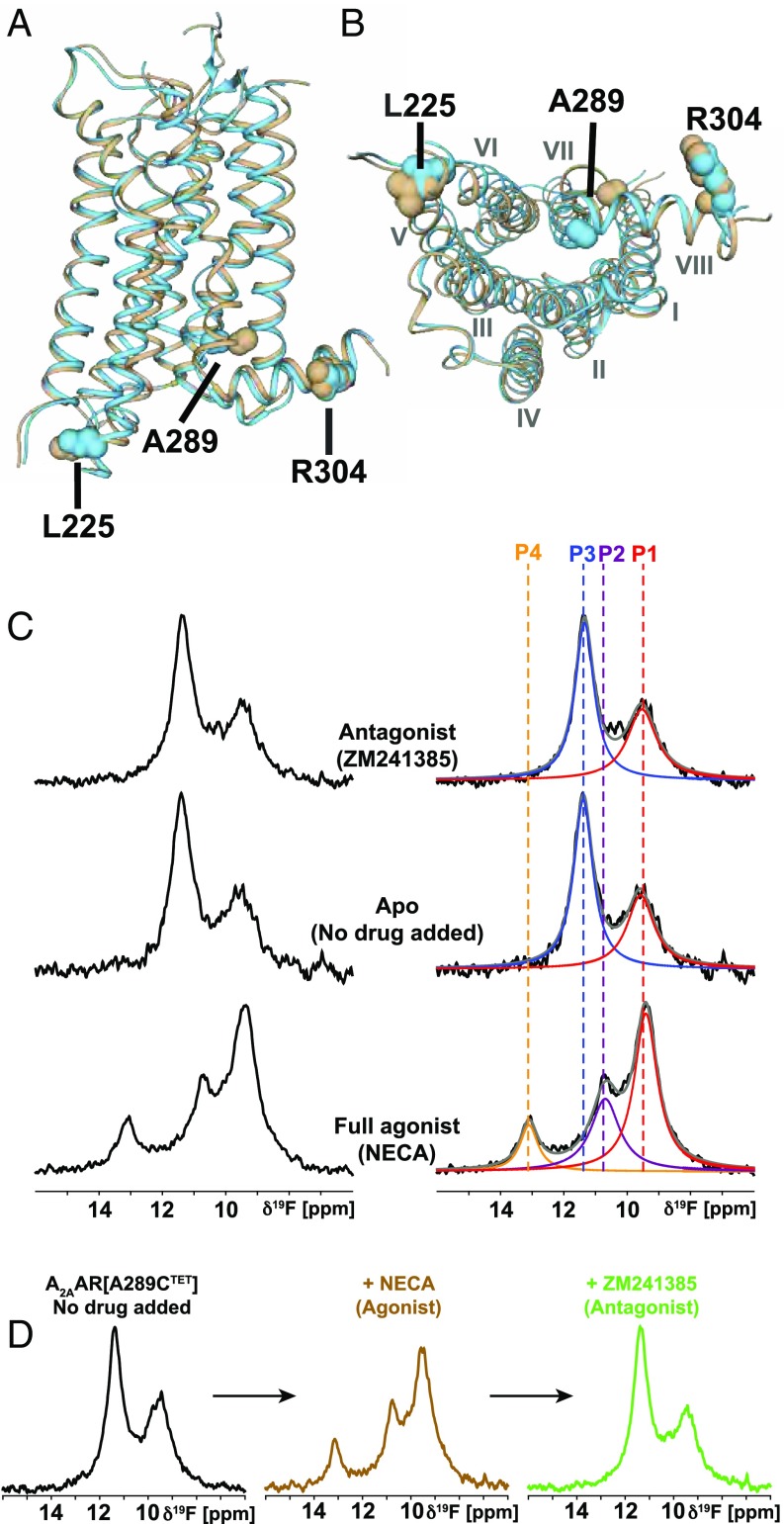

The selection of the engineered Cys sites was based on comparison of crystal structures of A2AAR complexes with antagonists and agonists, which showed that the intracellular ends of the transmembrane helices (TM) VI and VII undergo major rearrangements (10–13, 23, 24). We therefore introduced cysteines into sequence positions 225 and 289, which are located near the intracellular tips of TM VI and TM VII, yielding A2AAR[L225C] and A2AAR[A289C] (Fig. 1 A and B). In the selection of these two sites, we also considered earlier NMR and crystallographic studies with rhodopsin, the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR), and A2AAR, which had identified similar receptor locations as hotspots for activation-related conformational changes (22, 25–30).

Fig. 1.

Location of 19F-NMR probes in the crystal structure of A2AAR and NMR response to variable drug efficacy. (A) Side view of a superposition of the antagonist complex A2AAR–ZM241385 (brown, PDB-ID: 3ELM) with the agonist complex A2AAR–UK432097 (cyan, PDB-ID: 3QAK); the extracellular membrane surface is at the top. The three sequence positions selected for the 19F labels are highlighted by spheres and identified. (B) Same as A, view onto the intracellular surface; Roman numerals indicate the TM numbering. (C) The 1D 19F-NMR spectra of A2AAR[A289CTET] complexes with ligands of varying efficacy, as indicated in the Center. On the Right, the NMR spectra shown on the Left are interpreted by Lorentzian deconvolutions with the minimal number of components that provided a good fit, i.e., P1 to P4. The chemical shift positions of P1 to P4 are indicated by colored broken vertical lines. (D) The 1D 19F-NMR observation of ligand exchange in A2AAR[A289CTET]. The agonist NECA was added at saturating concentration to the apo-A2AAR and then displaced by the more strongly binding antagonist ZM241385.

As a control, we also investigated A2AAR[R304CTET], where the position of the engineered cysteine in helix VIII does not show major differences between the crystal structures of A2AAR complexes with agonists and antagonists (10, 12–14).

All three variants of A2AAR used here were shown to retain the pharmacological activity of the parent receptor, using radioligand saturation binding (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

The 19F-NMR of A2AAR Complexes Shows Different Conformational Ensembles in Response to Variable Efficacy of the Bound Drug.

Experiments with A2AAR[A289CTET] revealed pronounced 19F-NMR spectral changes between agonist complexes and antagonist complexes. The complexes with antagonists contain two signals with chemical shifts δ ≈ 11.4 ppm (P3) and δ ≈ 9.5 ppm (P1), which coincides with the spectrum of apo-A2AAR[A289CTET] (Fig. 1C). Complexes with agonists contain a signal at the chemical shift of P1 and two new signals, P2 and P4, at δ ≈ 10.8 and 13.1 ppm, but there is no signal intensity at position P3 (Fig. 1C). The line shapes of the dominant components in the spectra of antagonist and agonist complexes at 9.5 and 11.4 ppm, respectively, are closely similar and narrower than the other components. There are at most subtle variations among the spectra of complexes with different antagonists or with different agonists (SI Appendix, Table S1), respectively (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2), so that the 19F-NMR spectra of A2AAR[A289CTET] represent “fingerprints” for the corresponding functional states. The two different patterns of 19F-NMR signals seen in Fig. 1C are thus characteristic of conformational ensembles associated, respectively, with the functionally inactive receptor and its active-like state present when an agonist is bound to the extracellular orthosteric site in the absence of interactions with intracellular partner proteins. This assignment is further supported by the 19F-NMR–detected ligand competition experiments of Fig. 1D. Starting with the two-signal spectrum of apo-A2AAR[A289CTET], addition of the agonist NECA resulted in the appearance of the characteristic spectral features for agonist complexes. Subsequent addition of an excess of the high-affinity antagonist ZM241385 yielded a spectrum characteristic of the antagonist-bound receptor. We conclude that we observed transitions from an inactive conformational ensemble of apo-A2AAR[A289CTET] to an active-like ensemble of the complex with NECA and then from this active-like state to an inactive ensemble of the complex with ZM241385. It is intriguing that the complex of A2AAR with the partial agonist LUF 5834 shows the signal of the inactive state, rather than that for the active-like state (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Observation of the 19F-NMR signals originating from CTET in sequence position 225 provided similar results to those obtained from observation of CTET in position 289. Despite the much smaller dispersion of the chemical shifts (see also the next section), the presence of a new signal for complexes of A2AAR[L225CTET] with agonists, compared with complexes with antagonists, is readily apparent (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). The signals obtained from the reporter group in position 225 are again identical among different antagonist complexes and the apo-form of the receptor, and different agonist complexes also show closely similar 19F-NMR signals (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Deconvolution of the signals showed a good fit with the assumption of two and three components for the inactive and active-like states (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). While the relative intensities and line widths assigned to the two components of the inactive state signal coincide qualitatively with those observed at CTET289, the intensity distributions in the signals for the active-like states is clearly different, indicating different responses to drug efficacy at the tips of TMVI and TMVII.

For CTET in sequence position 304, no differences were seen between the 19F-NMR signals of the apo-form, complexes with antagonists, and complexes with agonists (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This absence of a response to different efficacies of the bound ligand is in line with the absence of differences in the spatial arrangement of helix VIII between crystal structures of A2AAR complexes with agonists or antagonists (Fig. 1 A and B).

In the continuation of this work, we focus on drug complexes with A2AAR[A289CTET], making use of the high spectral resolution of the 19F-NMR spectra recorded with this probe location.

The 19F-NMR in Solution and Crystal Structures of A2AAR.

To link the NMR data with the available A2AAR crystal structures, we performed aromatic ring current shift (δR) calculations (SI Appendix, Table S2) (31, 32). Since only small ring current shifts of <0.1 ppm were calculated for the CTET groups at positions 225 and 304, which is due to the absence of nearby aromatic residues and consistent with the small chemical shift dispersion observed at these two sites (SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4), the following discussion is focused on A2AAR [A289CTET]. For the A2AAR–ZM214385 complex, a small downfield shift of δR ≈ 0.2 ppm was calculated, and for A2AAR–NECA there was a large upfield shift of δR ≈ −1.4 ppm. The difference of about 1.6 ppm is due to conformational rearrangements that bring the aromatic rings of Phe286, Phe295, and Phe299 into proximity of residue 289 in the structure of the agonist complex. These calculated shifts are in close agreement with the experimental chemical shift difference of 1.9 ppm between signals P1 and P3 (Fig. 1C), whereas all other combinations of pairs of possible corresponding peaks in the two spectra do not fit the crystal data. The implication is that the most highly populated states P3 and P1 in the complexes with ZM241385 and NECA, respectively, coincide with the corresponding crystal structures, whereas the conformers giving rise to the NMR signal P1 in the antagonist complex and those represented by P2 and P4 in the agonist complex were not seen in the crystals. Additional ring current calculations using the presumed fully active state in the crystal structure of the ternary complex of A2AAR, NECA, and a “mini G protein” (15) yielded an upfield shift of δR ≈ −1.2 ppm for Ala289, which is close to that for the active-like A2AAR–NECA state. In summary, the ring current calculations yielded assignments for the dominantly populated conformations of the inactive (P3) and active-like (P1) states and support that the crystal structures do not represent the full repertoire of A2AAR conformations present in solution at ambient temperature.

Rate Processes in Function-Related Conformational Ensembles of A2AAR.

The presence of individually resolved NMR signals establishes an upper limit for the exchange rates (kex) between the A2AAR conformations represented by these signals, i.e., kex ≲10−3 s−1. Here, we explore the dynamic processes in these conformational ensembles further with saturation transfer difference experiments (STD) (33, 34) and 2D exchange spectroscopy (EXSY) (35).

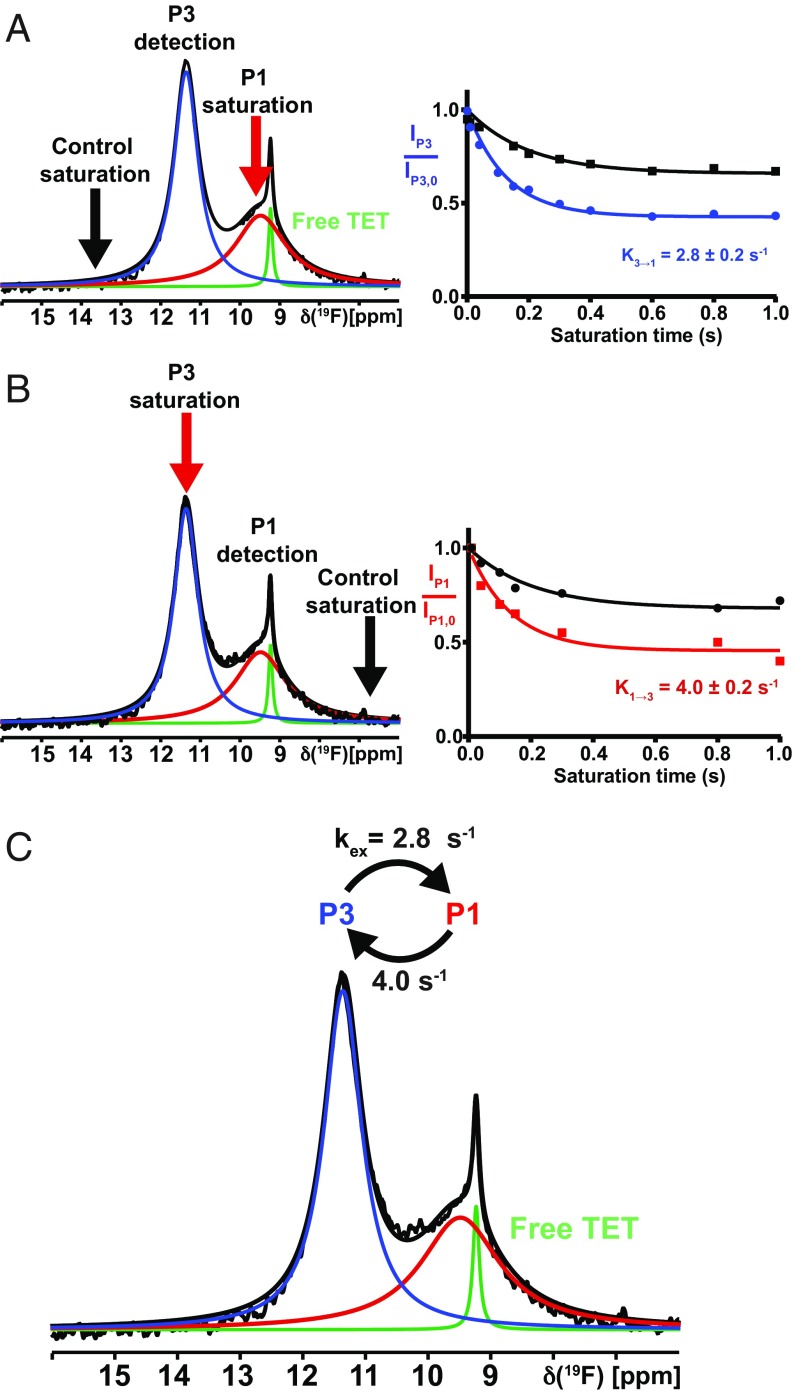

For the A2AAR[A289C]–ZM241385 complex, 1D 19F-STD experiments were performed with preirradiation on P1, monitoring changes in the intensity of P3, and collecting reference data with preirradiation at 13.3 ppm. The saturation times were 0.05–1.0 s. The measurements were then performed also with preirradiation at P3 and detection on P1 (Fig. 2 A and B). Analysis of the STD data using the Bloch–McConnell formalism (36, 37) established that kex (3→1) = 2.8 s−1 and kex (1→3) = 4.0 s−1 (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Conformational exchange in the A2AAR complex with the antagonist ZM241385 by 19F-NMR saturation transfer. (A, Left) The 1D 19F-NMR spectrum. The Lorentzian deconvolution introduced in Fig. 1 is indicated. A red arrow indicates the carrier position for the preirradiation, and a black arrow indicates the position for the reference measurement. The observed peak is indicated by “detection.” (A, Right) Plots of the normalized intensity of the observed peak, P3, versus the saturation pulse length after irradiation on P1 (cyan) and at the control (black). (B) Same as A, with inverted direction. (C) Survey of the conformational exchange rates in the A2AAR[A289CTET]–ZM241385 complex.

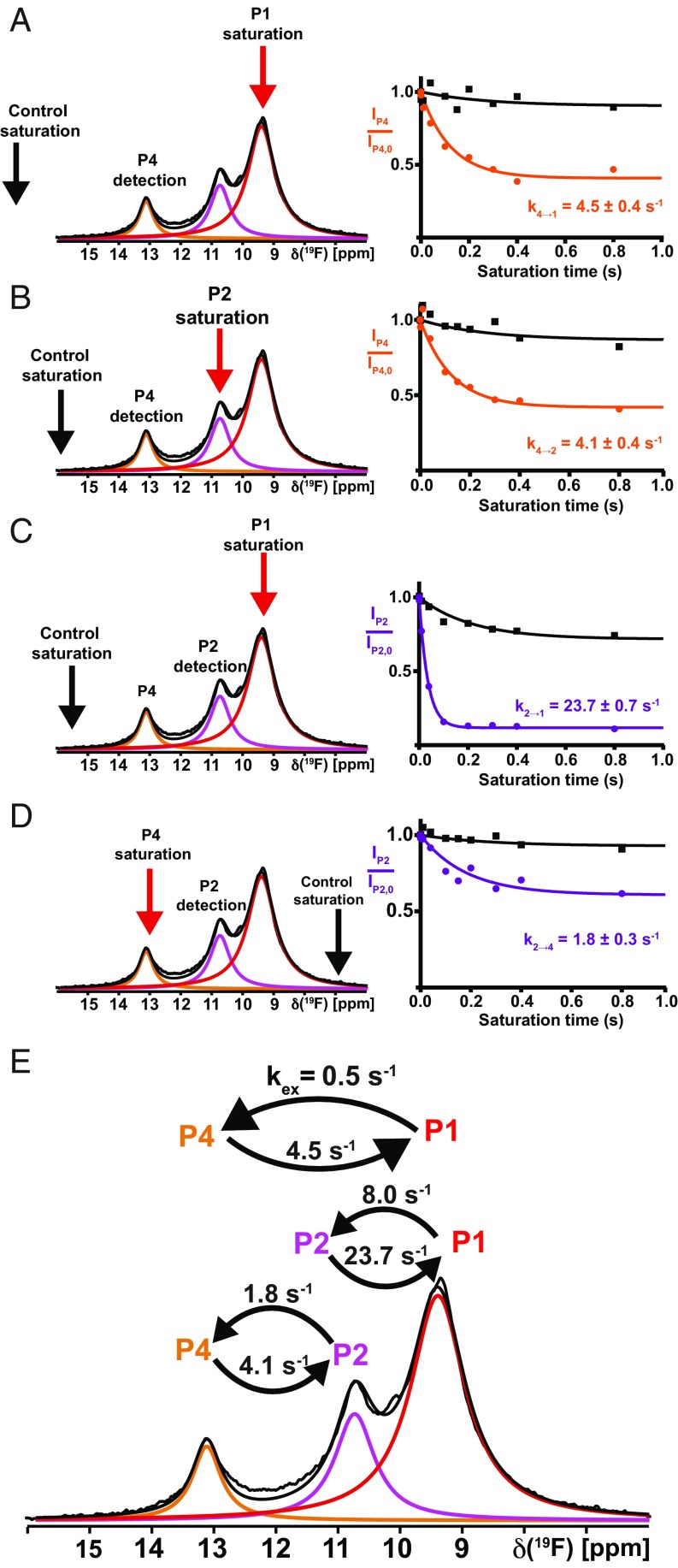

For agonist-bound A2AAR[A289CTET], STD experiments were performed with preirradiation of all three signals (Fig. 3 A–D, red arrows), and reference data were recorded with preirradiation at the chemical shifts indicated by the black arrows in the figure. Analysis of the STD data resulted in the following exchange rates: kex (4→1) = 4.5 s−1, kex (1→4) = 0.5 s−1, kex (4→2) = 4.1 s−1, kex (2→4) = 1.8 s−1, kex (2→1) = 23.7 s−1, and kex (1→2) = 8.0 s−1 (Fig. 3E). It is remarkable that with the exception of kex (2→1) and kex (1→2), slow exchange was measured for all pairs of conformers.

Fig. 3.

Conformational exchange in the A2AAR complex with the full agonist NECA by 19F-NMR saturation transfer. (A–D) Four individual measurements linking P1, P2, and P4, same presentation as in Fig. 2 A and B. (E) Survey of the conformational exchange rates in the A2AAR[A289CTET]–NECA complex. Please note in C and D that the saturation and control saturation are not symmetrical to the detection position, and this arrangement was chosen to prevent falsification of the data by direct irradiation of the tail of the observed signal.

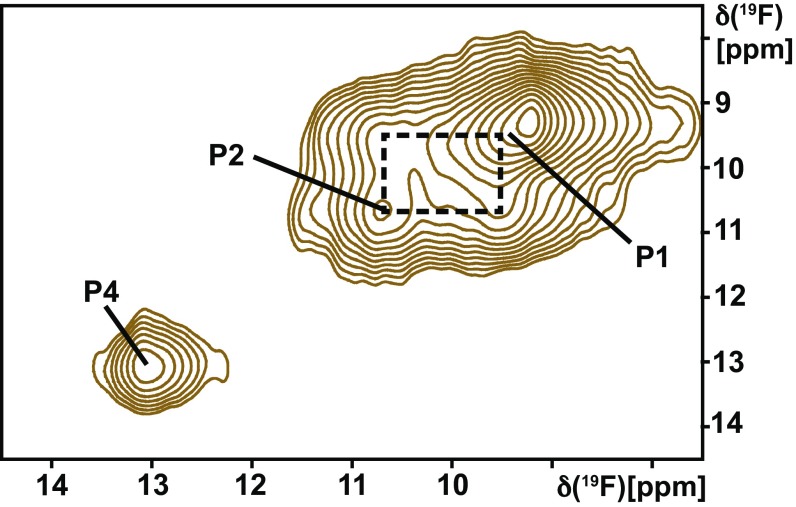

The conformational exchange rates from STD measurements were qualitatively confirmed with the use of 2D exchange spectroscopy (EXSY). In the 2D [19F,19F]-EXSY spectrum of the A2AAR[A289CTET] complex with the agonist NECA, exchange crosspeaks between P2 and P1 were observed, but there were no crosspeaks between P4 and either P1 or P2 (Fig. 4). There were no crosspeaks between the two NMR signals of the antagonist-bound receptor (Fig. 1). The EXSY data thus confirm the coexistence of widely different exchange rates among the conformational substates of the different activation levels of A2AAR (Figs. 2C and 3E).

Fig. 4.

Conformational exchange in the A2AAR complex with the full agonist NECA observed by 2D exchange spectroscopy. A contour plot is shown of a 2D [19F, 19F]-EXSY spectrum collected at 280 K with a mixing time of 100 ms. The diagonal peak positions of P1, P2, and P4 are labeled, and a dashed box indicates crosspeaks observed between P1 and P2.

The 19F-NMR–Based Comparison of A2AAR with a Constitutively Active Variant.

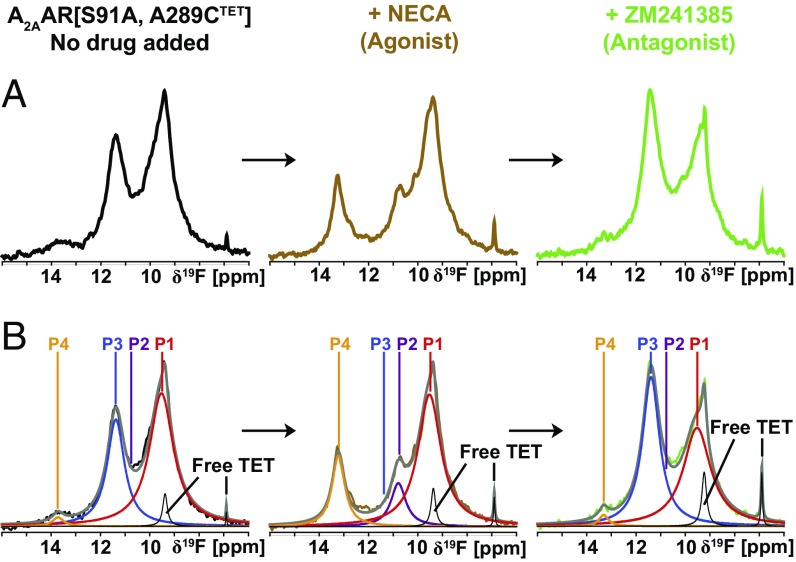

A2AAR[S91A], which contains a single amino acid replacement near the allosteric switch at D2.50 in the transmembrane-spanning region of the receptor, has been demonstrated to exhibit significant basal activity and increased signaling at full activation in HEK293T cells stimulated with the full agonist CGS21680 (38). The 19F-NMR spectra of A2AAR[S91A, A289CTET] show qualitatively similar signals and exchange rates as A2AAR (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), confirming the structural integrity of the modified protein. Nonetheless, the functional differences relative to A2AAR are paralleled by important differences between the NMR spectra. The apo-form of the variant protein shows increased intensity for the signal P1, compared with apo-A2AAR[A289CTET], and there is a weak peak at the position P4, which had no signal intensity in apo-A2AAR. Upon addition of the agonist NECA, spectra of A2AAR[S91A, A289CTET] showed increased intensities for the signals P1 and P4, compared with A2AAR[A289CTET], where the increased intensity of P4 was particularly striking. In competition binding experiments, addition of an excess amount of the high-affinity antagonist ZM241385 to the NECA-bound A2AAR[S91A, A289CTET] yielded a spectrum with similar signal positions as for the apo-protein, but different relative signal intensities (Fig. 5B). Overall, in contrast to A2AAR, the spectra of the apo-form and the antagonist-bound complex of the constitutively active mutant protein contain admixtures of 19F-NMR signals that are characteristic of the active-like state. For both the inactive state and active-like state, the exchange rates among the different conformers represented by the individual 19F-NMR signals are closely similar to those measured for the wild-type protein (Figs. 2 and 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Fig. 5.

Dynamic processes in the 19F-labeled constitutively active mutant A2AAR[S91A, A289CTET] observed by 1D 19F-NMR. (A) Same ligand exchange experiment as in Fig. 1D. (B) Lorentzian deconvolutions of the spectra shown in A.

Discussion

The present quantitative description of A2AAR structural ensembles by 19F-NMR probes complements a recent qualitative many-parameter overview of A2AAR structural plasticity by high-resolution NMR, which revealed that there are structural manifolds linked to function (16, 17). The 19F-NMR spectra observed for probes in TM VI and TM VII are qualitatively similar, but only the spectra TM VII are sufficiently well resolved to enable quantitative measurements, due to the location of the –CF3 group near aromatic residues that reflect the efficacy of bound drugs.

The STD and 2D EXSY (Figs. 2–4) showed that exchange between the two conformers of the inactive state and with the component P4 in the active-like state is slow. The corresponding high energy barrier indicates that differences between these substates likely involve major structural rearrangements of the polypeptide backbone, while the active-like state contains also two substates, P2 and P1 (Figs. 3 and 4), with a low energy barrier for interconversion. The available data indicate that all substates of the active-like conformation are separated from the inactive state by high energy barriers.

Overall, two conclusions can be drawn from the observations. First, considering the high energy barriers separating at least one component in each activation state from the other structures in the ensemble, it could be that only one of the conformers is linked to activation. Second, the difference in resolution between the probes on TM VI and TM VII (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3) illustrates how the NMR data can be optimized by placement of probes near indigenous aromatic amino acid residues, or possibly by introduction of extrinsic aromatic residues near the NMR probe (39).

A2AAR is the second human GPCR studied by 19F-NMR in solution, after the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR), which contained equilibria between one inactive conformational state and one active-like state (26), which were in slow exchange (25) and showed different relative populations at different probe sites. Considering the present data for A2AAR, we conclude that β2AR cannot serve as a model for human GPCRs overall, or even for class A GPCRs. It is further intriguing that the relative populations of active-like states in β2AR could be directly related to biased agonism (26). Since there are no published findings of biased agonists for A2AAR, 19F-NMR experiments may guide future efforts to explore A2AAR biased agonists.

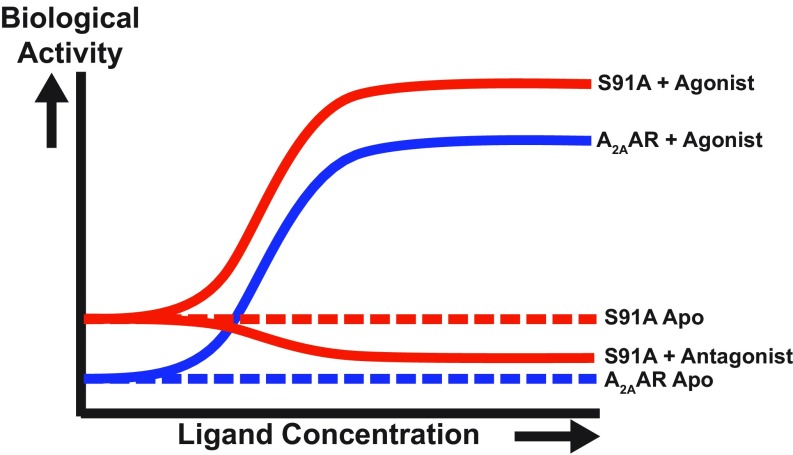

Since the intensity of the NMR signal P4 of agonist-bound A2AAR could be related to the activation level, it now provides a means for assessing basal activity (Fig. 6). As no admixtures of active-like states were detected in either apo- or antagonist-bound A2AAR[A289CTET] (Fig. 1 C and D), we conclude that the 19F-NMR data reflect the inherently low basal activity of A2AAR measured in cells (38). Recent NMR studies using a 19F probe in a position on helix VI, which provided a limited chemical shift dispersion comparable to the one shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3, was interpreted to show that the basal activity amounted to 70% of the activity of agonist-bound A2AAR (18, 19). Clearly, this contrasts with the present NMR studies and with literature data of the pharmalogical activity of A2AAR (38). There are additional apparent discrepancies in refs. 18 and 19 relative to the present data; in view of the large chemical shift dispersion and the resulting high spectral resolution by our 19F probe, we are confident in the interpretation of our results.

Fig. 6.

Biological response versus ligand concentration as manifested in the 19F NMR spectra. A plot is shown of the biological activity (i.e., G protein signaling) versus ligand concentration for A2AAR and A2AAR[S91A], as labeled on the right of the individual sigmoidal response curves. Relative biological activity was determined by observation of the intensity of the peak P4 in 19F-NMR spectra of A2AAR[A289CTET] and A2AAR[S91A, A289CTET]. The dashed lines represent the basal signaling level of the two proteins.

From the relations between the 19F-NMR data and the A2AAR crystal structures revealed by ring current shift calculations (SI Appendix, Table S2), only one combination of substates between inactive and active-like A2AAR is consistent with predicted chemical shifts from the crystal structures. This pair of substates is dominantly populated and shows narrower NMR lines than all other substates except for P4 (Fig. 1). The NMR data in solution at ambient temperature thus manifest conformations that are not observed in crystals. This is most apparent for signal P4, which is shifted downfield by ∼1.5 ppm from the predicted chemical shift for the active-like state. The increased intensity of the NMR signal P4 for the antagonist complex of a constitutively active mutant establishes a direct relation to A2AAR activation. Since all available A2AAR crystal structures thus represent only a fraction of the repertoire of function-relevant conformations, it could even be that the physiological action of A2AAR is mainly based on a conformer that has not yet been seen in crystal structures. In this context, it is also intriguing that A2AAR[A289CTET] with the bound partial agonist LUF5834 yields spectra that are those of antagonist-bound A2AAR[A289CTET], which suggests that the local conformation at the intracellular end of TM VII corresponds to an inactive state for this partial agonist.

Materials and Methods

The TET-labeled A2AAR variants used in this study were expressed and purified as previously described (21). The solutions used for NMR measurements contained 25 to 50 µM protein in 50 mM Hepes at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% DDM, 0.01% CHS, and excess ligand. All NMR data were measured on a Bruker AVANCE 600 spectrometer using a QCI 1H/19F-13C/15N quadruple resonance cryoprobe with shielded z-gradient coil. Spectra were processed using Bruker TOPSPIN version 3.1, and signals were deconvoluted using the MNOVA software version 10.0.0.2. Additional details are described in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank K. White (University of Southern California) for help with analysis of the radioligand binding dating. We acknowledge support from the NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Protein Structure Initiative Biology Grants U54 GM094618 and R01GM115825). L.S. was supported by a Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds PhD fellowship and by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). M.T.E. acknowledges an American Cancer Society postdoctoral research fellowship. K.W. is the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Professor of Structural Biology at The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1813649115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hauser AS, Attwood MM, Rask-Andersen M, Schiöth HB, Gloriam DE. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: New agents, targets and indications. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:829–842. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fredholm BB, Chen J-F, Masino SA, Vaugeois J-M. Actions of adenosine at its receptors in the CNS: Insights from knockouts and drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:385–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belardinelli L, et al. The A2A adenosine receptor mediates coronary vasodilation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:1066–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson KA, Gao Z-G. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armentero MT, et al. Past, present and future of A(2A) adenosine receptor antagonists in the therapy of Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;132:280–299. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins LE, et al. The novel adenosine A2A antagonist Lu AA47070 reverses the motor and motivational effects produced by dopamine D2 receptor blockade. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2012;100:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young A, et al. Co-inhibition of CD73 and A2AR adenosine signaling improves anti-tumor immune responses. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittal D, et al. Antimetastatic effects of blocking PD-1 and the adenosine A2A receptor. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3652–3658. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun B, et al. Crystal structure of the adenosine A2A receptor bound to an antagonist reveals a potential allosteric pocket. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:2066–2071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621423114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaakola V-P, et al. The 2.6 angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White KL, et al. Structural connection between activation microswitch and allosteric sodium site in GPCR signaling. Structure. 2018;26:259–269.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doré AS, et al. Structure of the adenosine A(2A) receptor in complex with ZM241385 and the xanthines XAC and caffeine. Structure. 2011;19:1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu F, et al. Structure of an agonist-bound human A2A adenosine receptor. Science. 2011;332:322–327. doi: 10.1126/science.1202793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lebon G, et al. Agonist-bound adenosine A2A receptor structures reveal common features of GPCR activation. Nature. 2011;474:521–525. doi: 10.1038/nature10136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter B, Nehmé R, Warne T, Leslie AGW, Tate CG. Structure of the adenosine A2A receptor bound to an engineered G protein. Nature. 2016;536:104–107, and erratum (2016) 538:542. doi: 10.1038/nature19803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eddy MT, et al. Extrinsic tryptophans as NMR probes of allosteric coupling in membrane proteins: Application to the A2A adenosine receptor. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:8228–8235. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b03805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eddy MT, et al. Allosteric coupling of drug binding and intracellular signaling in the A2A adenosine receptor. Cell. 2018;172:68–80.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye L, et al. Mechanistic insights into allosteric regulation of the A2A adenosine G protein-coupled receptor by physiological cations. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1372. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03314-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye L, Van Eps N, Zimmer M, Ernst OP, Prosser RS. Activation of the A2A adenosine G-protein-coupled receptor by conformational selection. Nature. 2016;533:265–268. doi: 10.1038/nature17668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark LD, et al. Ligand modulation of sidechain dynamics in a wild-type human GPCR. eLife. 2017;6:e28505. doi: 10.7554/eLife.28505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sušac L, O’Connor C, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. In-membrane chemical modification (IMCM) for site-specific chromophore labeling of GPCRs. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:15246–15249. doi: 10.1002/anie.201508506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein-Seetharaman J, Getmanova EV, Loewen MC, Reeves PJ, Khorana HG. NMR spectroscopy in studies of light-induced structural changes in mammalian rhodopsin: Applicability of solution (19)F NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13744–13749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hino T, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor inactivation by an allosteric inverse-agonist antibody. Nature. 2012;482:237–240. doi: 10.1038/nature10750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lebon G, Edwards PC, Leslie AGW, Tate CG. Molecular determinants of CGS21680 binding to the human adenosine A2A receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;87:907–915. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.097360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horst R, Liu JJ, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. β2-adrenergic receptor activation by agonists studied with 19F NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:10762–10765. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu JJ, Horst R, Katritch V, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. Biased signaling pathways in β2-adrenergic receptor characterized by 19F-NMR. Science. 2012;335:1106–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.1215802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eddy MT, Didenko T, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. β2-adrenergic receptor conformational response to fusion protein in the third intracellular loop. Structure. 2016;24:2190–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung KY, et al. Role of detergents in conformational exchange of a G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:36305–36311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.406371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manglik A, et al. Structural insights into the dynamic process of β2-adrenergic receptor signaling. Cell. 2015;161:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim TH, et al. The role of ligands on the equilibria between functional states of a G protein-coupled receptor. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9465–9474. doi: 10.1021/ja404305k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson C, Jr, Bovey F. Calculation of nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of aromatic hydrocarbons. J Phys Chem. 1958;29:1012–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forsen S, Hoffman RA. Exchange rates by nuclear magnetic multiple resonance. III. Exchange reactions in systems with several nonequivalent sites. J Phys Chem. 1964;40:1189–1196. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forsén S, Hoffman RA. Study of moderately rapid chemical exchange reactions by means of nuclear magnetic double resonance. J Phys Chem. 1963;39:2892–2901. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeener J, Meier BH, Bachmann P, Ernst RR. Investigation of exchange processes by two‐dimensional NMR spectroscopy. J Phys Chem. 1979;71:4546–4553. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McConnell HM. Reaction rates by nuclear magnetic resonance. J Phys Chem. 1958;28:430–431. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bloch F. Nuclear induction. Phys Rev. 1946;70:460–474. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Massink A, et al. Sodium ion binding pocket mutations and adenosine A2A receptor function. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;87:305–313. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.095737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu D, Wüthrich K. Ring current shifts in (19)F-NMR of membrane proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2016;65:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10858-016-0022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.