Abstract

Introduction

Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE), also known as marantic endocarditis, is a rare, underdiagnosed complication of cancer, in the context of a hypercoagulable state. NBTE represents a serious complication due to the high risk of embolisation from the sterile cardiac vegetations. If these are not properly diagnosed and treated, infarctions in multiple arterial territories may occur.

Case presentation

The case of a 47-year-old male is described. The patient was diagnosed with a gastric adenocarcinoma, in which the first clinical manifestation was NBTE. Subsequently, a hypercoagulability syndrome was associated with multi-organ infarctions, including stroke and eventually resulted in a fatal outcome.

Conclusions

NBTE must be considered in patients with multiple arterial infarcts with no cardiovascular risk factors, in the absence of an infectious syndrome and negative blood cultures. Cancer screening must be performed to detect the cause of the prothrombotic state.

Keywords: endocarditis, stroke, multi-organ arterial infarctions, gastric adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) is part of the clinical manifestation spectrum characterising paraneoplastic hypercoagulability. In NBTE cases, vegetations of platelets and fibrin accumulate on the cardiac valves. These vegetations are fragile and have a high embolic potential. Approximately half of NBTE patients have systemic embolic events, most commonly affecting the cerebral circulation. In NBTE, these systemic embolic events are the main cause of mortality among patients. [1,2,3].

NBTE is a rare condition and a frequently underdiagnosed cause of ischemic stroke. Elucidating the cause of ischemic stroke in young patients without accompanying cardiovascular risk factors is a challenge for neurologists. If atherothrombotic pathology and cardiac arrhythmias have been excluded, consideration should be given to the possibility of cardiac disease such as endocarditis. [2].

The fatal case of a young patient with NBTE causing multiple arterial infarctions in the brain, lungs, spleen and kidneys, which was proved to be the initial manifestation of an occult gastric adenocarcinoma, is presented in this paper.

Case report

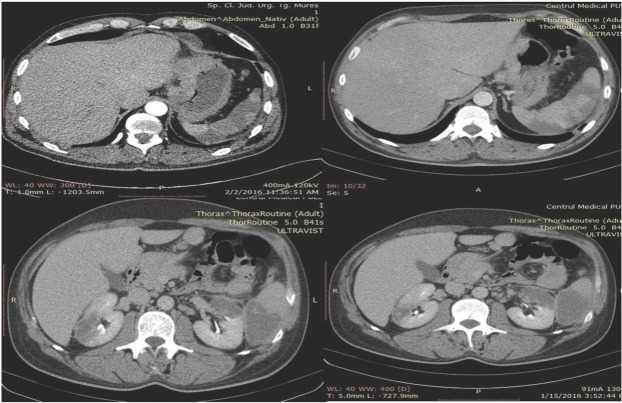

The case is presented of a 47-year-old male patient in apparently good health, suffered increasing weight loss during a 6-weeks-period. He was admitted to the emergency department of the Emergency County Hospital Targu Mures, Romania, presenting with sudden onset of dyspnoea, chest pain, micro haemoptysis, low-grade fever and fatigue. Physical examination revealed fever, skin paleness, mild tachycardia and laterocervical lymphadenopathy. All other physical and neurological findings were normal. An ECG revealed sinus tachycardia, right bundle branch block and negative T waves in V1-V4, DIII and aVF. The chest-abdomen-pelvis CT showed pulmonary, renal and splenic infarctions and the presence of bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Abdominal CT scan showing multi-organ infarcts

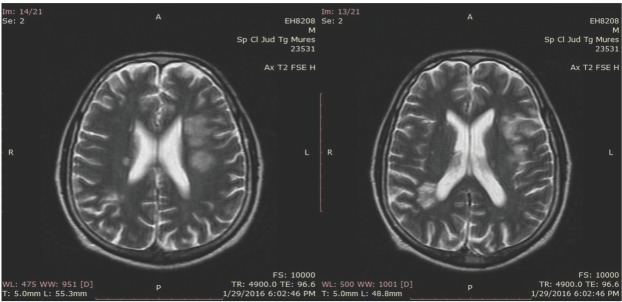

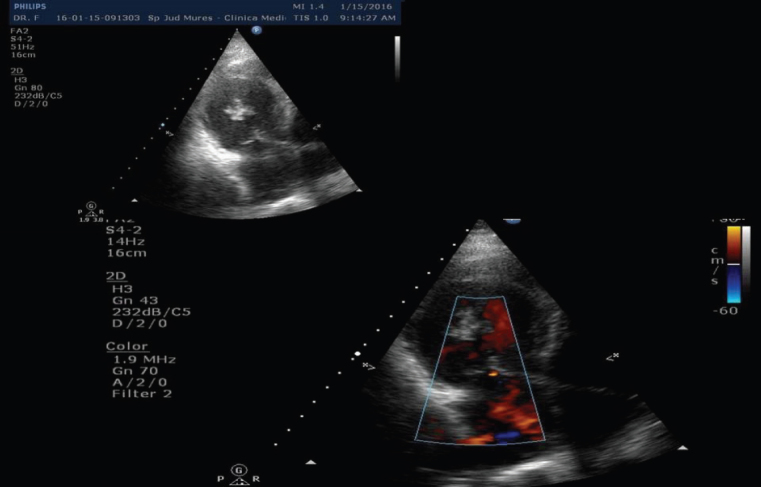

The brain-computer tomography found a hypodense lesion in the right parietal lobe. Transthoracic (TTE) and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) revealed a mobile echogenic mass of 0,8 x 0,9 cm on the mitral valve (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography showed a mobile echogenic mass on the mitral valve

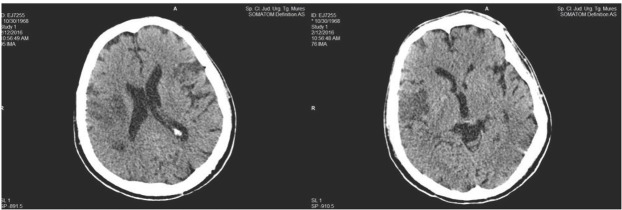

Vascular Doppler ultrasonography showed no signs of deep vein thrombosis in the lower limbs. Bacterial endocarditis was suspected at this point, and the patient was admitted to the Department of Cardiology Emergency County Hospital Targu Mures. The initial laboratory examination results (complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, procalcitonin level, C-Reactive Protein, blood ion levels, coagulation tests, amylase, urea, creatinine) were all normal. The transaminase levels were three times above the normal range, and D-dimers were above 35 mg/L Repeated aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal blood cultures were all negative. The patient was treated with intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics, cefuroxime 1.5 g and gentamicin 80 mg every 12 hours, and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), enoxaparin 1 mg/kg every 12 hours, subcutaneously. After eight days of hospitalisation, he developed right-sided hemiparesis, graded as 4/5 on the Medical Research Council scale, and severe motor aphasia. Brain MRI revealed multiple lesions in hypersignal on T2-weighted images, suggestive of embolic infarctions in the left frontotemporal and the right parietal lobes. (Figure 3).

Carotid Doppler ultrasound was normal. Repeated TEE showed a vegetation with an uneven surface, measuring 0,3 x 0,51 cm on the atrial surface of the mitral valve. There was no, mitral stenosis or regurgitation. As repeated blood cultures were negative and the patient showed no clinical signs of an infectious syndrome, the possibility of an aseptic marantic endocarditis was considered. His hereditary thrombophilia panel, antithrombin III, protein C, protein S, Factor V Leiden, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation screening, as well as the autoimmune panel, anti- cardiolipin IgG and IgM, antinuclear antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, were analysed. All results were within normal limits. In an attempt to detect a neoplastic process, tumour markers were taken. Alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, prostate-specific antigen were all within the normal range. The marker Cyfra 21-1, recorded as 5.9 ng/ml, was out with the normal range.

After 14 days of hospitalisation, the patient presented with a normochromic, normocytic anaemia with a progressive decrease in haemoglobin to 6.5 g/dl. The haematocrit values decreased to 19.5%. Gastroscopy revealed an ulcerated tumour at the gastric angle, which extended from the antrum to the subcardial region, measuring 4x6 cm and presenting diffuse bleeding. A biopsy was taken, and the pathology report indicated an infiltrative, poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma.

In spite of parenteral anticoagulant, antiplatelet, antibiotic, gastric antisecretory therapy and red blood cell transfusion, the patient’s neurological status worsened, and he developed tetraparesis with left hemiplegia. A cerebral CT examination was repeated and revealed a new infarction in the right sylvian artery. (Figure 4.)

Fig. 3.

Areas of hyperintensity on T2-weighted MRI sequences in the left frontal lobe and the right parietal lobe.

Fig. 4.

Cerebral CT scan with acute right middle cerebral artery infarction

Due to the patient`s impaired level of consciousness and respiratory failure, he was transferred to the intensive care unit where he required supportive care measures. The patient’s neurological condition worsened with progressive deterioration in consciousness, increased intracranial pressure, and transtentorial brain herniation. Death ensued four weeks after his initial admission to the hospital.

Discussions

NBTE is a rare condition which, before echocardiography, had been diagnosed only following a post-mortem examination. It is clinically suspected if iterative and consecutive embolic events occur in several arterial areas. [1,2,3].

Post-mortem studies show that the incidence of NBTE is approximately 1% of the general population but increases by times five in patients with cancer. [4,5].

Neoplasia is associated with a pronounced prothrombotic status, which increases the risk of thromboembolic events by a factor of five. NBTE is part of the clinical manifestations’ spectrum characterising paraneoplastic hypercoagulability, along with deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, disseminated intravascular coagulation and thrombotic microangiopathy. [6].

The pathogenesis of the prothrombotic status in patients with gastric adenocarcinomas is linked to a release of procoagulant molecules by tumour cells, the most well-known being tissue factor and cancer procoagulant. This leads to an excessive generation of thrombin via the extrinsic pathway. Digestive adenocarcinomas can also accelerate the formation of thrombi by secreting a highly adherent glycoprotein called mucin, which is secreted directly into the blood, aggravating the hypercoagulability. This is an accepted characteristic for neoplasia. In the endothelial cells, platelets and lymphocytes, the mucin interacts with certain cell adhesion proteins, causing the formation of platelet-rich thrombi. [7,8,9,10]

NBTE is a sterile endocarditis, affecting intact aortic and mitral valves. Fibrin and platelets are deposited in areas with increased blood flow. Frequently, NBTE is detected only by necropsy, as the cardiac vegetation is small, fragile, with an embolization tendency. It is usually too small to be seen with a transthoracic echocardiography. TEE has a much higher sensitivity in detecting NBTE. Taccone et al. (2008) observed that NBTE was the main aetiopathogenic cause of an ischemic stroke in patients with systemic cancer, especially in case of adenocarcinomas. [1,2,4,11,12].

Embolization occurs most commonly in the cerebral, renal, splenic, coronary and mesenteric vessels, multiple infarctions being the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients. Cerebral infarctions due to paraneoplastic hypercoagulability and NBTE are usually multiple, extensive and have a poor prognosis. Sixty-seven percent of patients with stroke and neoplasia have multiple cerebral infarctions. [1,13,14,15].

Coagulation testing is required if a paraneoplastic hypercoagulability is suspected. In the present case, the prothrombin time and the activated partial thromboplastin time were both normal, but the level of fibrinogen/fibrin degradation products were increased. Thrombin activation is assessed by measuring D-dimers. Our patient showed an increased level of D-dimers. D-dimers cannot be used as a screening tool, but it has been noticed that neoplasia patients with associated cerebral infarctions, have elevated D-dimer levels compared to stroke patients without neoplasia. [16, 17]

The treatment of a stroke patient with cancer and other arterial infarctions is complex requiring close collaboration between neurologists, oncologists and intensive care physicians. The use of parenteral anticoagulation by patients with paraneoplastic hypercoagulability and NBTE is overshadowed by the increased risk of the haemorrhagic transformation of the areas affected by cerebral infarction. [18] Compared to oral antivitamin K, anticoagulant treatment with LMWH has proved to be more efficient in preventing recurrent deep vein thrombosis in cancer patients.[19,20] In contrast, in patients with NBTE, it is not clear which systemic anticoagulant treatment is optimal for secondary embolism prevention. However, current guidelines [21] suggest that both LMWH and unfractionated heparin are equally effective in treating this pathology.

In our case, under parenteral anticoagulant treatment with therapeutic-dose LMWH, the patient’s neurological condition worsened with a new cerebral embolization originating from the endocardial vegetation. This caused a malignant cerebral infarction followed by death. [19,20,21].

NBTE-prognosis is poor, due to its association with an incurable neoplastic disease, but also due to thromboembolic complications. [1]

The present case report had an intriguing clinical picture of bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism and arterial infarctions in multiple vascular areas, as inaugural manifestations of a gastric adenocarcinoma. The peculiarity of this case lies in its development, which was initially favourable but was followed by the severe worsening of the patient’s neurological condition and finally by his death. This progression raises questions regarding the effectiveness of the LMWH therapy.

Conclusion

In case of patients with multiple arterial infarctions, one should consider the possibility of an NBTE, which is frequently associated with a detected or undetected neoplasm. Once NBTE has been diagnosed, it is essential to exclude an infectious endocarditis or a primary thrombophilia. Therefore, a detailed paraclinical examination should be performed to detect an occult neoplasia, especially an adenocarcinoma. Diagnosis and treatment of NBTE, in the context of a complex paraneoplastic pro-coagulant status, represents a challenge, involving a multidisciplinary approach, as the optimal anticoagulation treatment has not yet been established.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the internal research grant of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Targu Mures, 18/2015

Footnotes

Informed consent The written informed consent to publish this case presentation and the related images was granted by the patient’s wife. A copy of this consent has been handed to the Chief Editor of the JCCM.

Bibliography

- 1.el-Shami K, Grifiths E, Streiff M.. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in cancer patients: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Oncologist. 2007;12:518–23. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H, Fritz T, Banga P, Wohns D, Cohle S, Banga S. The search for cryptogenic stroke, a case of marantic endocarditis. Int J Cardiovasc Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;2:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borowski A, Ghodsizad A, Cohnen M, Gams E. Recurrent embolism in the course of marantic endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:2145–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llenas-Garcia J, Guerra–Vales JM, Montes–Moreno S, López-Rios F, Castelbón-Fernández FJ, Chimeno-Garcia J.. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis: clinicopathologic study of a necropsy series. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007;60:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzales Quintela A, Candela MJ, Vidal C, Roman J, Aramburo P.. Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis in cancer patients. Acta Cardiol. 1991;46:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldenberg N, Kahn SR, Solymoss S. Markers of coagulation and angiogenesis in cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4194–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao LV. Tissue factor as a tumor procoagulant. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1992;11:249–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01307181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caine GJ, Stonelake PS, Lip GY, Kehoe ST. The hypercoagulable state of malignancy: pathogenesis and current debate. Neoplasia. 2002;4:465–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaturvedi P, Singh AP, Batra SK. Structure, evolution and biology of MUC4 mucin. FASEB J. 2008;22:966–81. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9673rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varki A. Trousseau’s syndrome: multiple definitions and multiple mechanisms. Blood. 2007;110:1723–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-053736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taccone FS, Jeangete SM, Blecic SA. First-ever stroke as initial presentation of systemic cancer. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;17:169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scalia GM, Tandon AK, Robertson JA. Stroke, aortic vegetations and disseminated adenocarcinoma- case of marantic endocarditis. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21:234–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cestari DM, Weine DM, Panageas KS, Segal AZ, DeAngelis LM. Stroke in patients with cancer: incidence and etiology. Neurology. 2004;62:2025–30. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129912.56486.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singhal AB, Topcuoglu MA, Buonanno FS. Acute ischemic stroke paterns in infective and nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis: a difusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. Stroke. 2002;33:1267–73. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000015029.91577.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong CT, Tsai LK, Jeng JS. Paterns of acute cerebral infarcts in patients with active malignancy using difusion-weighted imaging. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:411–6. doi: 10.1159/000235629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sturgeon CM, Dufy MJ, Hofmann BR. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine Practice Guidelines for use of tumor markers in liver, bladder, cervical and gastric cancers. Clin Chem. 2010;56:e1–48. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.133124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uemura J, Kimura K, Sibazaki K, Inoue T, Iguchi Y, Yamashita S.. Acute stroke patients have occult malignancy more often than expected. Eur Neurol. 2010;64:140–4. doi: 10.1159/000316764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bajkó Z, Bălaşa R, Moţăţăianu A. Malignant Middle Cerebral Artery Infarction Secondary to Traumatic Bilateral Internal Carotid Artery Dissection. A Case Report. J Crit Care Med. 2016;2:135–41. doi: 10.1515/jccm-2016-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohr JP, Thompson JL, Lazar RM. A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1444–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, Bowden C. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:146–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitlock RP, Sun JC, Fremes SE, Rubens FD, Teoh KH. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for valvular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis 9thed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e576S–e600s. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]