Abstract

Objective:

To examine (1) the impact of pictorial cigarette warning labels on changes in self-reported warning label responses: warning salience, cognitive responses, forgoing cigarettes, and avoiding warnings, and (2) whether these changes differed by smokers’ educational level.

Methods:

Longitudinal data of smokers from two survey waves of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Europe Surveys were used. In France and the UK, pictorial warning labels were implemented on the back of cigarette packages between the two survey waves. In Germany and the Netherlands, the text warning labels did not change.

Findings:

Warning salience decreased between the surveys in France (OR=0.81, p=0.046) and showed a non-significant increase in the UK (OR=1.30, p=0.058), cognitive responses increased in the UK (OR=1.34, p<0.001) and decreased in France (OR=0.70, p=0.002), forgoing cigarettes increased in the UK (OR=1.65, p<0.001) and decreased in France (OR=0.83, p=0.047), and avoiding warnings increased in France (OR=2.93, p<0.001) and the UK (OR=2.19, p<0.001). Warning salience and cognitive responses decreased in Germany and the Netherlands, forgoing did not change in these countries, and avoidance increased in Germany. In general, these changes in warning label responses did not differ by education. However, in the UK, avoidance increased especially among low (OR=2.25, p=0.001) and moderate educated smokers (OR=3.21, p<0.001).

Conclusion:

The warning labels implemented in France in 2010 and in the UK in 2008 with pictures on one side of the cigarette package did not succeed in increasing warning salience, but did increase avoidance. The labels did not increase educational inequalities among continuing smokers.

Keywords: Europe, public policy, smoking, social class, cigarette warning labels

INTRODUCTION

In most Western countries, tobacco smoking is more prevalent among people with low compared to high educational levels [1–3]. To help mitigate resulting health disparities, it is important that there are tobacco control policies that decrease educational differences in smoking. To date, however, there has been too little attention paid to the question of whether the impact of tobacco control policies varies across educational levels [4]. This paper examined whether the impact of pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages implemented in France and the United Kingdom (UK) varied across educational levels of smokers. Educational differences in changes in four self-reported warning label responses were studied: warning salience, cognitive responses, forgoing cigarette, and avoiding warnings.

Studies using population-based surveys found that smokers from high educated groups reported noticing text-only warning labels (warning salience) more often than smokers from low educated groups [5–6]. Additionally, smokers from high educated groups reported higher perceived effectiveness of the text-only warning labels increasing their thoughts about health risks of smoking and about quitting (cognitive responses) [7].

For pictorial warning labels, both experimental and population-based survey studies found equal effectiveness for low and high educated groups on warning salience [6,8] and cognitive responses [8–11]. Three studies on pictorial warning labels in Mexico and Brazil found that lower educated groups had stronger cognitive responses [6,12,13] and more often reported that warning labels stopped them from having a cigarette (forgoing cigarettes) [6].

There is evidence that the implementation of pictorial warning labels is followed by an increase in the number of smokers covering up the warnings, keeping them out of sight or using a cigarette case (avoiding warnings) [14–16]. To our knowledge, no studies have examined educational differences in (changes in) avoidance of cigarette warning labels.

A study about educational differences in warning label impact in Europe showed mixed results. This study examined self-reported responses to text-only warning labels with cross-sectional population-based survey data from France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. Scores on a combined measure of salience, cognitive responses, and forgoing cigarettes due to the warning labels were higher among low to moderate educated French, German, and Dutch smokers than high educated smokers, while the opposite trend was observed in the UK [17]. Differences in avoidance of warning labels were not reported. Changes in educational differences after the impact of the European pictorial warning labels have not been studied yet.

Pictorial cigarette warning labels are not yet mandatory in the European Union. The European Commission directive 2001/37/EC came into effect in 2003 and required cigarettes sold in the European Union to carry text warning labels. Two general warnings (“smoking kills” and “smoking seriously harms you and others around you”) must be placed on 30% of the front of the cigarette pack and one of a rotating set of 14 additional text warnings must be placed on 40% of the back of the pack. Optional color photographs and other illustrations for the back of the pack were adopted by the European Commission in 2005. Member states can choose between three illustrations for each of the 14 additional warnings, some showing pictures of diseased organs and human suffering, and others showing messages to encourage smokers to get help with quitting. The UK implemented pictorial warnings in 2008 and France in 2010 (Table 1). Although they are called pictorial warning labels, not all of them contain photographs. The UK chose 11 labels with photographs and 4 labels with text-based images, while France adopted 14 labels with photographs and no text-based images (Figure 1). Both in France and the UK, factory-made cigarette packages were first obligated to carry pictorial warning labels, while roll-your-own tobacco had a longer phase-in period (Table 1).

Table 1:

Warning label policies, fieldwork periods, sample sizes and follow-up rates per country.

| Introduction of warning label policy | Baseline survey | Follow-up survey | No. of months between pictorial warning labels were obliged for factory-made cigarettes and start of follow-up surveya | No. of smokers at the baseline survey | No. of continuing smokers participating in both surveys | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | Text warning labels implemented in Sep. 2003, pictorial warning labels implemented between Apr. 2010 and Apr. 2012 | Sep. 2008 - Dec. 2008 (wave 2) |

Sep. 2012 - Dec. 2012 (wave 3) |

17 months | 1,540 | 861 |

| United Kingdom | Text warning labels implemented in Feb. 2003, pictorial warning labels implemented between Oct. 2008 and Sep. 2010 | Sep. 2007 - Feb. 2008 (wave 6) |

July. 2010 - Dec. 2010 (wave 8) |

9 months | 1,643 | 751 |

| Germany | Text warning labels implemented in Oct. 2003 | Jul. 2007 - Nov. 2007 (wave 1) |

Sep. 2011 – Oct. 2011 (wave 3) |

- | 1,515 | 496 |

| The Netherlands | Text warning labels implemented in Jun. 2002 | April 2008 (wave 1) |

May 2011 - Jun. 2011 (wave 5) |

- | 1,668 | 755 |

| Total | 6,366 | 2,863 |

Both France and the UK had a two year phase-in period of the pictorial warning labels in which factory-made cigarettes were obligated to carry pictorial warning labels after one year and roll-your-own tobacco after two years.

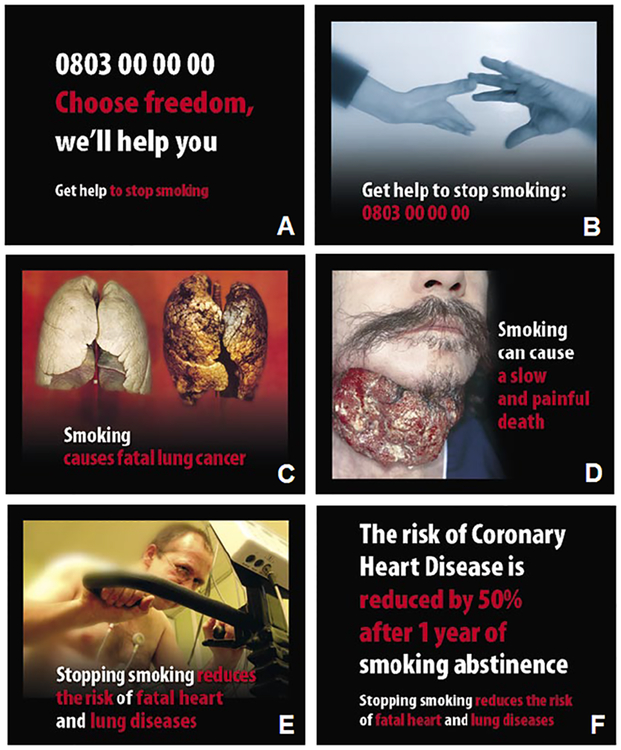

Figure 1: Examples of the optional European pictorial warning labels for the back of cigarette packages*.

* ‘Pictures’ A and F are sed in the UK, pictures B and E are used in France, and pictures C and D are used in both the UK and France.

In the current study, we examined the impact of pictorial warning labels on changes in self-reported warning label responses among smokers with low, moderate, and high levels of education by using a quasi-experimental design. We used longitudinal data from two survey waves of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Europe Surveys conducted in France, the UK, Germany, and the Netherlands. In France and the UK (‘intervention’ countries), pictorial warning labels were implemented between the two survey waves. In Germany and the Netherlands (‘control’ countries), the text warning labels did not change. Our research questions were:

Was the implementation of pictorial warning labels in France and the UK associated with a change in self-reported warning label responses that was larger than any change in these responses in Germany and the Netherlands where no pictorial warning labels were implemented?

Were these changes in self-reported warning label responses between baseline and follow-up different for low, moderate, and high educated smokers?

METHODS

Sample

Longitudinal survey data from smokers aged 18 years and older from the ITC Europe Surveys in France, the UK, Germany, and the Netherlands were used. The mode of interviewing was computer assisted telephone interviewing in France, the UK, and Germany and computer assisted web interviewing in the Netherlands. Telephone respondents were recruited using probability sampling methods with fixed line telephone numbers selected at random from the population of each country. Web respondents were recruited from a large probability-based database with respondents who had indicated their willingness to participate in research on a regular basis [18]. Respondents in all countries were eligible to participate at initial recruitment into the survey if they had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and were currently smoking at least once a month.

For France, we used one survey wave from before the implementation of pictorial warning labels (wave 2, 2008) and one survey wave after the implementation (wave 3, 2012). For the UK, we also used one survey wave before (wave 6, 2007–2008) and one after (wave 8, 2010) the implementation of pictorial warning labels. For Germany and the Netherlands, two survey waves were used when text warning labels were on cigarette packages: one survey wave from 2007 or 2008 and one survey wave from 2011. In all countries, we limited our analyses to current smokers because frequency of exposure to warning labels and cognitive and behavioral responses to warning labels is reduced once people quit smoking and not all questions were asked of ex-smokers in all countries.

Across countries, 6,366 current smokers participated in the baseline surveys that were used in this study. Of them, 2,863 respondents participated in the follow-up survey and were still smoking at follow-up (Table 1). These smokers differed from baseline smokers who were lost to follow-up or who stopped smoking: continuing smokers who participated in the follow-up survey were more often female in the Netherlands (χ2=4.23, p=0.040), were older in all countries (F France=11.12, p<0.001; UK=13.36, p<0.001; Germany=18.63, p<0.001; the Netherlands=36.70, p<0.001), had lower education in the Netherlands (χ2=13.26, p=0.001), were more often exclusively smoking rolling tobacco in the Netherlands (χ2=7.62, p=0.006), were heavier smokers in all countries except France (F UK=7.48, p=0.006; Germany=4.26, p=0.039; the Netherlands=15.00, p<0.001), and were less often planning to quit smoking within 6 months in all countries (χ2 France=15.03, p<0.001; UK=6.85, p=0.009; Germany=4.36, p=0.037; the Netherlands=15.22, p<0.001). Respondents who participated in the follow-up survey and were still smoking did not differ significantly from smokers who were lost to follow-up or who stopped smoking on warning salience, cognitive responses, forgoing cigarettes, and avoiding warnings at baseline in any of the countries.

Measurements

Education was categorized into three levels: low (no degree, elementary school and lower secondary education), moderate (secondary vocational education and middle secondary education), and high (upper secondary education, university and post-graduation). The education levels were only partly comparable across countries because of differences in educational systems.

Warning salience was measured with the question “In the last month, how often have you noticed the warning labels on cigarette packages or on roll-your-own packs?” [14]. Responses were dichotomized into ever (1) versus never (0).

Cognitive responses to warning labels were measured with three questions: “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking?”, “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking?”, and “In the past 6 months, have warning labels on cigarette packages led you to think about quitting?” [14]. All responses were dichotomized into ever (1) versus never (0) and they were combined by computing a binary variable: any cognitive response (1) versus no cognitive responses (0).

Forgoing cigarettes because of warning labels was measured by asking respondents “In the last month, have the warning labels stopped you from having a cigarette when you were about to smoke one?” [14]. Responses to this question were dichotomized into ever (1) versus never (0).

Avoidance of warning labels was measured in the UK at both survey waves with the question “In the last month, have you made any effort to avoid looking at or thinking about the warning labels, such as covering them up, keeping them out of sight, using a cigarette case, avoiding certain warnings, or any other means?” [14]. In the Netherlands, a shortened version of the question was used at both survey waves: “In the last month, have you made any effort to avoid looking at or thinking about the warning labels by covering the warnings up?” France and Germany used the shortened version of the question at baseline and the longer version at follow-up. Respondents could answer these questions with (1) yes or (0) no.

Control variables were gender, age group (18–24, 25–39, 40–54, 55+), tobacco type (smoking exclusively rolling tobacco or (also) manufactured cigarettes), Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI), intention to quit, country, and time in sample (number of prior survey waves in which the person had participated). HSI was computed by taking the sum of two categorized measures: number of cigarettes per day and time to the first cigarette of the day [19]. HSI values ranged from 0 to 6 with higher values indicating stronger nicotine dependence [19].

Ethics

All surveys were cleared for ethics by the Office of Research Ethics of the University of Waterloo, Canada, and by the appropriate institutions in each country.

Analyses

All analyses were performed with SPSS version 22.0 and were weighted by age and gender to be representative of the smoker population in each country. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) analyses were performed to examine country, time, and educational level differences in (1) warning salience, (2) cognitive responses, (3) forgoing cigarettes, and (4) avoiding warnings. The data from all countries were pooled for the primary analyses. All dependent variables were dichotomous and, therefore, the binomial distribution and the logit link were used [20]. The repeated measure variable was survey wave: baseline or follow-up. The unstructured correlation structure was used, because this closely approximates the true correlation structure in large samples [21]. All GEE models were adjusted for time-invariant covariates (gender, age group at baseline, and country) and time-varying covariates (educational level, tobacco type, HSI, intention to quit, and time in sample).

In separate GEE analyses, we added interactions between country and survey wave (research question 1) and between country, survey wave, and educational level (research question 2). We adjusted these analyses for the interaction between educational level and survey wave, and the interaction between educational level and country. Dummy coding was used for educational level, country, and survey wave in the main and interaction analyses [22]. The p-values for the overall 3 degrees of freedom (df) tests for the country by wave interaction and the 6df tests for the education by country by wave interaction were reported in the table and text. When the overall tests of interactions were significant, single degree of freedom interactions were also examined, but these test statistics are not reported in the tables or the text. To facilitate interpretations for readers, Table 4 also shows stratified analyses separately for each country.

Table 4:

GEE analyses predicting warning label responses, pooled across countries with interactions and separately for each country.

| ALL COUNTRIES | Warning salience (n = 6,289) OR (95% CI) |

Cognitive responses (n = 6,299) OR (95% CI) |

Forgoing cigarettes (n = 6,288) OR (95% CI) |

Avoiding warnings (n = 6,295) OR (95% CI) |

| Survey wave | ||||

| Baseline | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Follow-up | 0.72 (0.65 to 0.80)*** | 0.79 (0.72 to 0.86)*** | 1.00 (0.87 to 1.14) | 2.31 (1.99 to 2.69)*** |

| Interactions (separate analyses) | ||||

| Country * wave (3 df) | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.001 | p=0.049 |

| Country * wave * education (6 df) | p=0.641 | p=0.248 | p=0.122 | p=0.002 |

| FRANCE | Warning salience (n = 1,531) OR (95% CI) |

Cognitive responses (n = 1,531) OR (95% CI) |

Forgoing cigarettes (n = 1,531) OR (95% CI) |

Avoiding warnings (n = 1,530) OR (95% CI) |

| Survey wave | ||||

| Baseline | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Follow-up | 0.81 (0.66 to 1.00)* | 0.70 (0.55 to 0.88)** | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.00)* | 2.93 (2.30 to 3.73)*** |

| UNITED KINGDOM | Warning salience (n = 1,618) OR (95% CI) |

Cognitive responses (n = 1,624) OR (95% CI) |

Forgoing cigarettes (n = 1,623) OR (95% CI) |

Avoiding warnings (n = 1,622) OR (95% CI) |

| Survey wave | ||||

| Baseline | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Follow-up | 1.30 (0.99 to 1.70) | 1.34 (1.14 to 1.58)*** | 1.65 (1.25 to 2.16)*** | 2.19 (1.72 to 2.80)*** |

| GERMANY | Warning salience (n = 1,502) OR (95% CI) |

Cognitive responses (n = 1,503) OR (95% CI) |

Forgoing cigarettes (n = 1,503) OR (95% CI) |

Avoiding warnings (n = 1,503) OR (95% CI) |

| Survey wave | ||||

| Baseline | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Follow-up | 0.62 (0.50 to 0.76)*** | 0.83 (0.69 to 0.99)* | 0.71 (0.46 to 1.11) | 2.57 (1.57 to 4.20)*** |

| THE NETHERLANDS | Warning salience (n = 1,638) OR (95% CI) |

Cognitive responses (n = 1,641) OR (95% CI) |

Forgoing cigarettes (n = 1,631) OR (95% CI) |

Avoiding warnings (n = 1,640) OR (95% CI) |

| Survey wave | ||||

| Baseline | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Follow-up | 0.47 (0.38 to 0.58)*** | 0.51 (0.44 to 0.61)*** | 1.06 (0.75 to 1.49) | 1.28 (0.80 to 2.03) |

All models were adjusted for gender, age group, educational level, tobacco type, HSI, intention to quit, and time in sample. The pooled analyses were also adjusted for country. The interaction analyses were also adjusted for the education by wave interaction and the education by country interaction.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Table 2 shows the sample characteristics for the smoking respondents at the baseline surveys in France, UK, Germany and the Netherlands. Respondents from the four countries significantly differed on gender, age group, educational level, tobacco type, HSI, and intention to quit smoking.

Table 2:

Sample characteristics at the baseline survey and time in sample at both surveys by country (weighted data).

| France (n = 1,540) |

United Kingdom (n = 1,643) |

Germany (n = 1,515) |

The Netherlands (n = 1,668) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | χ2 = 18.78 | ||||

| Female (%) | 45.3 | 49.9 | 42.3 | 45.7 | p < 0.001 |

| Male (%) | 54.7 | 50.1 | 57.7 | 54.3 | |

| Age group | χ2 = 81.60 | ||||

| 18–24 years (%) | 17.7 | 13.2 | 13.7 | 11.5 | p < 0.001 |

| 25–39 years (%) | 34.7 | 34.3 | 31.0 | 29.3 | |

| 40–54 years (%) | 32.7 | 30.9 | 36.1 | 34.8 | |

| 55 years and older (%) | 14.8 | 21.7 | 19.1 | 24.5 | |

| Educational level | χ2 = 507.08 | ||||

| Low (%) | 44.4 | 55.0 | 22.6 | 37.9 | p < 0.001 |

| Moderate (%) | 36.9 | 28.6 | 36.9 | 42.7 | |

| High (%) | 18.6 | 16.4 | 40.5 | 19.3 | |

| Smokes exclusively rolling tobacco | χ2 = 274.56 | ||||

| Yes, exclusively rolling tobacco (%) | 13.1 | 26.4 | 12.7 | 32.4 | p < 0.001 |

| No, manufactured cigarettes or both (%) | 86.9 | 73.6 | 87.3 | 67.6 | |

| Heaviness of smokinga | χ2 = 230.75 | ||||

| 0–1 | 45.5 | 23.2 | 39.3 | 27.9 | p < 0.001 |

| 2–4 | 50.6 | 68.5 | 55.2 | 65.1 | |

| 5–6 | 3.9 | 8.3 | 5.4 | 7.0 | |

| Intention to quit | χ2 = 29.08 | ||||

| Within 6 months (%) | 29.9 | 27.0 | 25.5 | 21.8 | p < 0.001 |

| Not within 6 months (%) | 70.1 | 73.0 | 74.5 | 78.2 | |

| Number of waves participated (time in sample) | F = 861.43 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.4 (0.7) | 4.2 (2.2) | 2.0 (0.8) | 3.5 (1.2) | p < 0.001 |

| Range | 1–3 | 1–8 | 1–3 | 1–5 |

Heaviness of smoking (HSI) is used as a continuous variable in the GEE analyses; HSI values ranged from 0 to 6 with higher values indicating stronger nicotine dependence.

Warning salience

The percentage of respondents who noticed warning labels in the last month by country, survey wave, and educational level can be seen in Table 3. Between 74% (Germany, follow-up survey) and 91% (UK, follow-up survey) of smokers noticed the warning labels in the last month.

Table 3:

Warning label responses by country, survey wave, and educational level (weighted data).

| France | United Kingdom | Germany | The Netherlands | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline survey (n = 1,540) |

Follow-up survey (n = 861) |

Baseline survey (n = 1,643) |

Follow-up survey (n = 751) |

Baseline survey (n = 1,515) |

Follow-up survey (n = 496) |

Baseline survey (n = 1,668) |

Follow-up survey (n = 755) |

|

|

Warning salience (% noticed in last month) |

||||||||

| Low educational level | 86.4 | 82.0 | 86.7 | 90.3 | 78.8 | 71.3 | 88.4 | 77.9 |

| Moderate educational level | 85.7 | 84.8 | 86.1 | 91.6 | 80.2 | 70.2 | 86.7 | 77.3 |

| High educational level | 85.3 | 85.1 | 88.1 | 89.7 | 85.2 | 78.8 | 87.2 | 77.1 |

| Total group | 86.0 | 83.8 | 86.8 | 90.5 | 81.6 | 73.9 | 87.4 | 77.7 |

|

Cognitive responses (% labels led to thinking) |

||||||||

| Low educational level | 90.0 | 87.3 | 63.0 | 69.3 | 71.1 | 68.1 | 61.3 | 42.7 |

| Moderate educational level | 89.1 | 81.2 | 67.0 | 73.9 | 63.3 | 50.0 | 61.5 | 43.6 |

| High educational level | 89.5 | 88.9 | 64.8 | 66.9 | 63.5 | 62.7 | 53.3 | 37.1 |

| Total group | 89.6 | 85.5 | 64.4 | 69.9 | 64.8 | 58.9 | 59.9 | 41.8 |

|

Forgoing cigarettes (% labels led to forgoing in last month) |

||||||||

| Low educational level | 30.0 | 26.7 | 6.9 | 10.1 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 7.3 | 5.5 |

| Moderate educational level | 19.6 | 14.9 | 11.4 | 15.3 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 6.4 | 7.8 |

| High educational level | 12.2 | 12.1 | 9.7 | 14.5 | 7.9 | 4.7 | 6.6 | 8.5 |

| Total group | 22.7 | 19.1 | 8.6 | 12.3 | 7.3 | 4.2 | 6.8 | 7.0 |

|

Avoiding warningsa (% labels led to avoidance in last month) |

||||||||

| Low educational level | 10.7 | 19.2 | 7.8 | 16.4 | 3.8 | 13.8 | 2.4 | 2.0 |

| Moderate educational level | 4.6 | 16.8 | 8.6 | 21.7 | 2.0 | 5.3 | 3.1 | 3.9 |

| High educational level | 3.8 | 13.6 | 11.2 | 15.4 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 3.4 |

| Total group | 7.2 | 16.9 | 8.6 | 17.6 | 2.3 | 5.7 | 2.5 | 3.3 |

Question changed between baseline and follow-up for France and Germany

The GEE analysis in Table 4 indicated that warning salience decreased between baseline and follow-up surveys (OR=0.72, p<0.001). In an additional GEE analysis, we added interactions between country, survey wave, and educational level (Table 4). The interaction between country and wave was significant (p<0.001). Stratified analyses showed that warning salience decreased in France (OR=0.81, p=0.046), showed a non-significant increase in the UK (OR=1.30, p=0.058), and decreased in Germany (OR=0.62, p<0.001) and the Netherlands (OR=0.47, p<0.001).

The three-way interaction between educational level, country and wave was not significant (p=0.641).

Cognitive responses

Between 42% (the Netherlands, follow-up survey) and 90% (France, baseline survey) of smokers reported thoughts about health risks or quitting due to warning labels (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the GEE analysis predicting cognitive responses. Cognitive responses decreased between the two survey waves (OR=0.79, p<0.001). An additional GEE analysis with interactions (Table 4) showed that the interaction between country and wave was significant (p<0.001). Cognitive responses to warning labels increased in the UK (OR=1.34, p<0.001), but decreased in the other countries (OR France=0.70, p=0.002; Germany=0.83, p=0.037; the Netherlands=0.51, p<0.001).

The three-way interaction between educational level, country, and wave was not significant (p=0.248).

In additional analyses (data not shown), the three survey questions about cognitive responses were analyzed separately. Affirmative responses to the question whether the warning labels made smokers think about quitting increased between baseline and follow-up for all countries combined and there was no significant interaction between country and wave. For the other two questions (whether the warning labels made smokers think about the health risks of smoking and made them more likely to quit) the interaction between country and wave was significant. These cognitive responses increased in the UK and decreased in the other countries.

Forgoing cigarettes

Between 4% (Germany, follow-up survey) and 23% (France, baseline survey) of smokers reported that warning labels stopped them from having a cigarette in the last month (Table 3).

As can be seen in Table 4, forgoing did not change between survey waves (OR=1.00, p=0.938). In the GEE analysis with interactions we found a significant interaction between country and wave (p=0.001). Stratified analyses showed that reports of forgoing cigarettes because of warning labels increased in the UK (OR=1.65, p<0.001), decreased in France (OR=0.83, p=0.047) and did not change significantly in the other countries (OR Germany=0.71, p=0.135; the Netherlands=1.06, p=0.742).

The three-way interaction between educational level, country, and wave was not significant (p=0.122).

Avoiding warnings

Between 2% (Germany, baseline survey) and 18% (the UK, follow-up survey) of smokers reported that they had made an effort to avoid looking at or thinking about the warning labels in the last month (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the GEE analysis for avoidance. Avoidance increased between baseline and follow-up surveys (OR=2.31, p<0.001). A separate GEE analysis (Table 4), showed a significant interaction between country and survey wave (p=0.049). Country-stratified analyses indicated that avoidance increased between baseline and follow-up in France (OR=2.93, p<0.001), the UK (OR=2.19, p<0.001), and Germany (OR=2.57, p<0.001), but not significantly so in the Netherlands (OR=1.28, p=0.304).

As can be seen in Table 4, the three-way interaction between educational level, country, and wave was significant (p=0.002). Analyses stratified by country (not shown in Tables) indicated that in the UK, the increase in avoidance between baseline and follow-up was especially pronounced among low (OR=2.25, p<0.001) and moderate educated smokers (OR=3.21, p<0.001). While in the Netherlands, there was no increase in avoidance among low and moderate educated smokers, there was a significant increase among high educated smokers (OR=3.52, p=0.036).

DISCUSSION

The current study showed that after the implementation of pictorial warning labels in France and the UK, warning salience did not increase, cognitive responses and forgoing of cigarettes increased only in the UK, and avoidance of warnings increased substantially in France and the UK. This is contrary to what has been found in previous pre-post studies, in which marked increases in all four warning label responses were observed after the implementation of pictorial warning labels [14–16,23]. A possible explanation is that the current European pictorial warning labels are placed on only one side of the cigarette package, while other countries have placed them both at the back and the front of the package. Previous studies [6,24] already found indications that it is important to place pictorial warnings on both the front and back of the package. Our study is the first that examined the impact of pictorial warnings on one side of the package with a pre-post population-based survey study.

The other research question that we examined, was whether there were educational differences in the change in warning label responses over time. Few studies have examined whether the impact of warning labels varies across educational levels [4]. Studies that have examined educational differences have not always used nationally representative samples surveyed both before and after the implementation of new warning labels. We found a significant difference in the increase in avoidance in the UK compared to the Netherlands. It seems that the increase in avoidance of warning labels between waves was larger among smokers with low and moderate levels of education compared to more highly educated smokers in the UK. In the Netherlands, there was no increase in avoidance among low and moderate educated smokers, but there was a significant increase among high educated smokers. Other educational differences in trends of self-reported warning label responses across countries were not significant. Therefore, we conclude that our findings point to a neutral equity impact of pictorial warning labels among continuing smokers. It should be noted that the results could have been different if we had also examined those who quit smoking.

The increase in cognitive responses and forgoing cigarettes only in the UK and not in France can possibly be explained by the set of pictorial warnings that the UK chose. The UK chose 4 out of 15 labels with text-based images, while France adopted 14 labels with photographs and no labels with text-based images (Figure 1). The UK set may have been more effective in stimulating thoughts about health risks of smoking and thoughts about quitting, and more effective in stopping smokers from having a cigarette than the French set. However, it is also possible that the longer period between the implementation of pictorial warnings and the follow-up survey in France (Table 1) played a role. It should be noted that additional analyses showed that one of the cognitive responses (warning labels made smokers think about quitting) did increase in France.

In Germany and the Netherlands, no pictorial warning labels were implemented and the text labels have been the same since 2003 and 2002 respectively. We found that warning salience and cognitive responses decreased in these countries. This pattern of decreases of self-reported warning label responses (warning label ‘wear-out’) has been reported before [14,15,25]. We found that warning avoidance increased in Germany, but avoidance remained much lower (6% tried to avoid labels in the last month at the second survey wave) than in France (17%) and the UK (18%) after the implementation of pictorial warning labels. The small increase in avoidance in Germany and (part of) the increase in France could have been due to the change in measurement of avoidance between the baseline and follow-up surveys in these countries.

Limitations

This study’s limitations are, first of all, that there were four years between the baseline and follow-up survey in France. Note that this does not mean that we could only assess the long-term impact of the implementation of pictorial warnings, because the follow-up surveys in both France and the UK were conducted only a few months after the pictorial warnings were fully implemented (this took two years in both countries, see Table 1). Therefore, we could still show the immediate impact of the full implementation of pictorial warnings in both countries. In the UK, Germany, and the Netherlands, because we chose survey waves that approximately matched the timing of four years between the two surveys studied in France, these countries had one or more survey waves completed in between the two studied waves. Any effect of this on our results is likely to be small as all analyses were controlled for time in sample. However, there could have been effects from other tobacco control activity that has happened between the baseline and follow-up surveys. For example, the price of cigarettes increased in France and there were several media campaigns about smoking. In the UK, there were no substantial price increases, but there were media campaigns about smoking during the study period. Germany and the Netherlands both implemented a partial smoke-free hospitality industry law. The Netherlands also had several price increases, ran media campaigns about smoking cessation, and implemented reimbursement of smoking cessation treatment. Even though we assume that these measures did not exert substantial impact on the warning label specific measures used in this study, we cannot completely rule out this possibility.

Another limitation is that we examined changes in self-reported warning label responses among continuing smokers and did not assess the impact of pictorial warning labels on quitting behavior. Additionally, the current study is a population-based survey with a quasi-experimental design. Although this can help us understand the ‘real-world’ impact of pictorial cigarette warning labels, it cannot provide conclusive evidence about causality.

Finally, not all smokers who participated in the baseline survey also completed the follow-up survey. Study participants were older, had a lower educational level, were more often exclusively smoking rolling tobacco, were heavier smokers, and were less often planning to quit smoking within 6 months than those who were lost to follow-up or who stopped smoking. Therefore, our results may not be fully generalizable to the population of smokers in the four European countries.

Implications

In 2016, the European directive 2014/40/EU comes into effect, which means that pictorial warning labels will be implemented on 65% of both sides of the cigarette package in the entire European Union. As larger warnings [26] and warnings on both sides of the pack [6] are more often noticed than smaller warnings on one side of the pack, it is possible that the new EU legislation will increase warning salience compared with the current text-only labels and the current pictorial labels on one side of the pack. A thorough monitoring of the impact of this new legislation is needed in which educational differences are taken into account. Also, our findings from Germany and the Netherlands imply that the warnings need to be changed regularly to prevent wear-out.

It is known from previous studies that cognitive responses and reports of forgoing cigarettes are positively associated with self-reported quit attempts at later time points, both directly [27,28] and indirectly [29]. This implies that the UK warning labels may have a positive impact on quit attempt behavior. Future studies should explicitly address this question by also including smokers who quit smoking in the analyses and examining effects on behavior.

We found that warning avoidance increased in France, the UK, and Germany. Previous population-based survey studies have found that avoidance strategies do not appear to reduce cessation behaviors [27,29,30]. Future studies should examine whether this applies to smokers from all educational groups.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study found that the warning labels implemented in France in 2010 and in the UK in 2008 with pictures on one side of the cigarette package did not succeed in increasing warning salience, but did increase avoidance of warnings. Cognitive responses to the warning labels and forgoing cigarettes because of the warning labels increased only in the UK and decreased in France. Pictorial warning labels did not seem to increase educational inequalities in self-reported warning label responses among continuing smokers.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

The warning labels implemented in France in 2010 and in the UK in 2008 with pictures on one side of the cigarette package did not succeed in increasing warning salience, but did increase avoidance of warnings.

Cognitive responses to the warning labels and forgoing cigarettes because of the warning labels increased only in the UK and decreased in France.

Pictorial warning labels on one side of the package did not seem to increase educational inequalities in self-reported warning label responses among continuing smokers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Several members of the ITC Project team at the University of Waterloo have assisted in all stages of conducting the ITC Netherlands surveys, which we gratefully acknowledge. In particular, we thank Thomas Agar and Anne Quah. This paper is a deliverable within the SILNE Project ‘Tackling socio-economic inequalities in smoking: Learning from natural experiments by time trend analyses and cross-national comparisons’.

FUNDING

The ITC Europe Surveys were supported by grants from Institut nationale du cancer (INCa), Observatoire français des drogues et toxicomanies (OFDT), and Institut national de prevention et d’education pour la sante (INPES) for ITC France Survey; Cancer Research UK (C312/A3726, C312/A6465, C312/A11039; C312/A11943) for ITC UK Survey; German Federal Ministry of Health, Dieter Mennekes-Umweltstiftung and Germany Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) for ITC Germany Survey; and the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw 70000001 and 121010008) for ITC Netherlands Survey. Geoffrey T. Fong is supported by a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and a Prevention Scientist Award from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. The SILNE Project is funded by the European Commission under the FP7-Health-2011 program (grant agreement 278273).

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beauchamp A, Peeters A, Wolfe R, et al. Inequalities in cardiovascular disease mortality: The role of behavioural, physiological and social risk factors. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan RC, Bangdiwala SI, Barnhart JM, et al. Smoking among U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:496–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunst A, Giskes K, Mackenbach J. Socio-economic inequalities in smoking in the European Union Applying an equity lens to tobacco control policies. Rotterdam: Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown T, Platt S, Amos A. Equity impact of population-level interventions and policies to reduce smoking in adults: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;138:7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borland R, Hill D. Initial impact of the new Australian tobacco health warnings on knowledge and beliefs. Tob Control 1997;6:317–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thrasher JF, Villalobos V, Szklo A, et al. Assessing the impact of cigarette package health warning labels: A cross-country comparison in Brazil, Uruguay and Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 2010;52(Suppl 2):206–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin Y, Wu M, Pan X, et al. Reactions of Chinese adults to warning labels on cigarette packages: A survey in Jiangsu Province. BMC Public Health 2011;11:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantrell J, Vallone DM, Thrasher JF, et al. Impact of tobacco-related health warning labels across socioeconomic, race and ethnic groups: Results from a randomized web-based experiment. PLOS ONE 2013;8:e52206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond D, Reid JL, Driezen P, et al. Pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs in the United States: An experimental evaluation of the proposed FDA warnings. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Hegarty M, Pederson LL, Yenokyan G, et al. Young adults’ perceptions of cigarette warning labels in the United States and Canada. Prev Chronic Dis 2007;4:A27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thrasher JF, Carpenter MJ, Andrews JO, et al. Cigarette warning label policy alternatives and smoking-related health disparities. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittencourt L, Person SD, Cruz RC, et al. Pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs and the impact on women. Rev Sáude Pública 2013;47:1123–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond D, Thrasher J, Reid JL, et al. Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings among Mexican youth and adults: A population-level intervention with potential to reduce tobacco-related inequities. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23(Suppl 1):57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT, et al. Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: Findings from four countries over five years. Tob Control 2009;18:358–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green AC, Kaai SC, Fong GT, et al. Investigating the effectiveness of pictorial health warnings in Mauritius: Findings from the ITC Mauritius Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. Published Online First: 18 April 2014. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yong HH, Fong GT, Driezen P, et al. Adult smokers’ reactions to pictorial health warning labels on cigarette packs in Thailand and moderating effects of type of cigarette smoked: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia Survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:1339–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hitchman SC, Mons U, Nagelhout GE, et al. Effectiveness of the European Union text-only cigarette health warnings: Findings from four countries. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagelhout GE, Willemsen MC, Thompson ME, et al. Is web interviewing a good alternative to telephone interviewing? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Netherlands survey. BMC Public Health 2010;10:351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: Using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict 1989;84:791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ballinger GA. Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organ Res Methods 2004;7:127–150. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin JM. Working correlation selection in generalized estimating equations. PhD dissertation: University of Iowa 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaccard J Interaction effects in logistic regression Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07–135 Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thrasher JF, Pérez-Hernández R, Arillo-Santillán E, et al. Towards informed tobacco consumption in Mexico: Effects of pictorial warning labels among smokers. Salud Pública Méx 2012;54:242–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakefield MA, Zacher M, Bayly M, et al. The silent salesman: An observational study of personal tobacco pack display at outdoor café strips in Australia. Tob Control 2014;23:339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hitchman SC, Driezen P, Logel C, et al. Changes in effectiveness of cigarette health warnings over time in Canada and the United States, 2002–2011. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:536–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammond D Health warning messages on tobacco products: A review. Tob Control 2011;20:327–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borland R, Yong H- H, Wilson N, et al. How reactions to cigarette packet health warnings influence quitting: Findings from the ITC Four-Country Survey. Addiction 2009;104:669–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li L, Borland R, Fong GT, et al. Smoking-related thoughts and microbehaviours, and their predictive power for quitting: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey. Tob Control. Published Online First: 25 February 2014. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051384 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yong HH, Borland R, Thrasher J, et al. Mediational pathways of the impact of cigarette warning labels on quit attempts. Health Psychology. Published Online First: 30 June 2014. doi: 10.1037/hea0000056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, et al. Graphic Canadian cigarette warning labels and adverse outcomes: Evidence from Canadian smokers. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1442–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]