Abstract

Purpose:

Lymph node (LN) involvement in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is associated with a poor prognosis. While lymph node dissection (LND) may provide diagnostic information, its therapeutic benefit remains controversial. Thus, the aim of our study is to analyze survival outcomes after LND for non-metastatic RCC and to characterize contemporary practice patterns.

Materials and Methods:

The National Cancer Database was queried for patients with non−metastatic RCC who underwent either partial or radical nephrectomy from 2010−2014. A total of 11,867 underwent surgery and LND. Chi square tests were used to examine differences in patient demographics. To minimize selection bias, propensity score matching (PSM) was used to select one control for each LND case (n= 19,500). Cox regression analyses were conducted to examine overall survival (OS) in patients who received LND compared to those who did not.

Results:

Of all patients undergoing LND for RCC (n= 11,867), 5, 23, 31, 47% were performed for tumors of clinical T stage 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Proportions of LND have not significantly changed from 2010 to 2014. No significant improvement in median OS for patients undergoing LND compared to no LND was shown (34.7 vs. 34.9 months, respectively; p = 0.98). Similarly, no significant improvement in median OS was found for clinically LN positive patients undergoing LND compared to no LND (p=0.90). On Cox regression analysis, LND dissection was not associated with an OS benefit (HR: 1.00; 95% CI 0.97–1.04).

Conclusions:

Among all RCC patients, LNDs are often performed for low stage disease, suggesting a potential overutilization of LND. No OS benefit was seen in any subgroup of patients undergoing LND. Further investigation is needed to determine which patient populations may benefit most from LND.

Keywords: Renal Cell Carcinoma, Lymph Node Dissection, Lymphadenectomy, Radical Nephrectomy, National Cancer Database

Introduction

Kidney cancer is the third most common genitourinary malignancy, with an estimated 65,340 new diagnoses and 14,970 deaths in 20181. The vast majority of kidney cancers are renal cell carcinoma (RCC), accounting for over 90% of renal parenchymal tumors2. RCC is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and an especially poor prognosis when there is lymph node (LN) involvement. For example, numerous studies have identified both clinical and pathologic lymphadenopathy as independent adverse prognostic factors for cancer-specific survival (CSS) and all-cause mortality (ACM).3

Surgical extirpation with partial nephrectomy (PN) or radical nephrectomy (RN) is the gold standard treatment for RCC2. Additionally, for many urologic malignancies, the role of LND in controlling disease progression and improving oncologic outcomes is well-established4–6. However, the benefits of performing a lymph node dissection (LND) for RCC remain controversial7–9.

Current American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines recommend lymph node dissection (LND) in the setting of clinical node positive (cN+) disease for staging and prognostic purposes2. Despite these recommendations, it is unclear whether LND in this setting provides any oncologic benefit. Multiple studies have suggested that LND does not confer a survival advantage in RCC patients, even in high-risk patients or those with cN+ disease10–12. Conversely, other studies have reported a small subset of pN1M0 RCC patients with isolated nodal disease may have a durable long-term survival benefit after LND3, 13. Further, the use of LND and its impact on survival in clinical practice is unknown, as this may differ from the results of controlled clinical trials or single-center registries.

Given the clinical equipoise of this intervention14, we sought to query the National Cancer Database (NCDB) – the largest cancer registry in the United States - to examine the outcomes and practice patterns of LND in non-metastatic RCC. Thus, we aimed to investigate survival outcomes after LND for non-metastatic RCC, as well as to characterize contemporary surgical practice patterns using a population-based approach. We hypothesized that LND would be performed most often in high risk patients, most commonly performed via an open surgical approach, and would provide a survival advantage in select non-metastatic cN+ RCC patients compared to those with cN- status.

Methods

Data Source

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is a national, hospital-based registry sponsored by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) and the American Cancer Society. All programs accredited by the CoC have been required to report cancers diagnosed or treated in their facilities. The NCDB includes more than 1,500 programs and approximately 70% of all newly diagnosed cases in the United States15. The data base also includes demographic information such as aggregate measures on education attainment and income in addition to individual diagnosis and treatment information such as number of clinical and pathologic lymph nodes and surgical modality16.

Study Population

A total of 173,834 patients from 2010–2014 were included in the kidney cancer data set. We excluded patients with metastasis (n= 36,870), non-surgical procedures (n= 24,001), and patients missing (or inconsistent) other critical information (n=2,000). The final sample size before propensity score matching (PSM) procedures was 110,963, including 11,867 patients with lymphadenectomies. To minimize the risk of including lymphadenectomies from surgical events separate from the definitive surgical procedures, only partial and radical nephrectomies were included; local tumor excision codes including biopsies were excluded from the unmatched population. Additionally, we excluded 70 (0.3%) patients from the PSM population due to disparate dates for first surgical procedure and definitive surgical procedure. Institutional review board exemption was granted for this study.

Statistical Analysis

Frequencies and proportions were calculated for all demographic and clinical categorical variables. Chi-square test was used to compare proportions and produce p-values. Means, medians, t-tests, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were calculated to examine LN yield and relevant continuous variables. An alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank statistics were used to examine overall survival before and after propensity score matching (PSM). To limit selection bias commonly observed in large observational studies, 1-to-1 propensity score-matched analysis was performed with a final sample size of 19,500 patients (9,750 LND patients and 9,750 no LND patients)17, 18.

Propensity scores were computed by modeling logistic regression with the dependent variable as having a LND, and the independent variables patient’s age, sex, race/ethnicity, Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Score, education attainment, household income type of health insurance, hospital type, clinical primary tumor stage, clinical lymph node positivity, surgical modality, and year of diagnosis. Covariate balance between matched groups (lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy) was examined after propensity scores were computed (Table 1). Afterwards, we used Cox proportional hazards regression to examine survival time between matched groups, LND vs. no LND. No additional variables were included in the model. To examine OS in high-risk patients, we conducted a sub-analysis to compare OS in cN+ patients who underwent LND vs. no LND patients. Similar to the main analysis, 1-to1 propensity score –matched analysis was used to compare OS in cN+ LND patients to no LND patients with a sample size of 3198 patients (1599 LND patients and 1599 no LND patients). Additional OS sensitivity analysis included (a) examination of patients having ≥3 LN examined, (b) excluding patients with only one LN examined, (c) excluding patients who received adjuvant or neoadjuvant systemic therapy. Both groups were compared to no LND patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics from patients diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma by lymph node dissection status before and after propensity score matching, NCDB 2010–2014

| Patient Characteristics |

Unmatched Population | Propensity Score Matched Population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No LN† Surgery N(%) |

LN† Surgery N(%) |

p-value‡ | No LN† Surgery N(%) |

LN† Surgery N(%) |

p-value | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≤50 | 26088(26) | 3033(24) | 0.18 | 2275(23.3) | 2198(22.5) | 0.60 |

| >50–60 | 25347(26) | 3125(26) | 2713(27.8) | 2728(28.0) | ||

| >60–70 | 24036(24) | 2867(24) | 2388(24.5) | 2445(25.1) | ||

| >70 | 23625(24) | 2842(24) | 2374(24.4) | 2379(24.4) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 61372(62) | 7562(64) | <0.01 | 6248(49.9) | 6268(50.1) | 0.82 |

| Female | 37724(38) | 4305(36) | 3502(50.1) | 3482(49.9) | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 83001(85) | 10082(86) | <0.01 | 8431(86.5) | 8410(86.3) | 0.31 |

| Black | 11827(12) | 1284(11) | 950(9.7) | 1024(10.5) | ||

| American Indian | 509(0.5) | 43(0.4) | 53(0.5) | 32(0.3) | ||

| Asian | 1933(2) | 224(2) | 221(2.3) | 192(2.0) | ||

| Other | 843(1) | 114(1) | 95(1.0) | 92(1.0) | ||

| Hispanic Ethnicity | ||||||

| Yes | 6201(7) | 705(6) | 0.15 | 579(6.1) | 554(5.9) | 0.37 |

| No | 89156(93) | 10749(94) | 8863(93.9) | 8905(94.1) | ||

|

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

||||||

| 0 | 677388(68) | 8307(70) | <0.0001 | 6725(69.0) | 6734(69.0) | 0.18 |

| 1 | 23581(24) | 2687(23) | 2233(22.9) | 2288(23.5) | ||

| 2 | 8127(8) | 873(7) | 792(8.1) | 728(7.5) | ||

| Income 2008–12 ($) | ||||||

| ≥62,000 | 17474(18) | 1962(17) | 0.02 | 3368(34.5) | 3171(32.5) | 0.11 |

| ≥47,999–62,999 | 23279(23) | 2771(23) | 2551(26.2) | 2677(27.5) | ||

| ≥38,000–47,999 | 23279(23) | 2771(24) | 222(22.8) | 2292(23.5) | ||

| <38,000 | 17474(18) | 1962(17) | 1609(16.5) | 1610(16.5) | ||

|

Education Attainment* |

||||||

| <7% | 22695(23) | 2771(23) | 0.13 | 1582(16.2) | 1614(16.6) | 0.29 |

| 7–12.9% | 32676(33) | 3967(33) | 2498(25.6) | 2581(26.5) | ||

| 13–20.9% | 26345(27) | 3124(26) | 3181(33.7) | 3245(33.3) | ||

| >21% | 17099(17) | 1955(17) | 2389(24.5) | 2310(23.7) | ||

| Insurance | ||||||

| Private Insurance | 45671(47) | 5578(48) | <0.01 | 4595(47.1) | 4617(47.4) | 0.16 |

| Not Insured | 3200(3) | 476(4) | 352(3.6) | 388(4.0) | ||

| Medicaid | 5606(6) | 710(6) | 530(5.4) | 558(5.7) | ||

| Medicare | 42051(43) | 4789(41) | 4138(42.4) | 4076(41.8) | ||

| Other Government | 1337(1) | 130(1) | 135(1.4) | 111(1.1) | ||

| Hospital Type | ||||||

| Academic/Research Cancer Program | 38378(41) | 5927(52) | <0.01 | 4813(49.4) | 5155(52.9) | 0.08 |

| Community Cancer Program | 6403(7) | 678(6) | 526(5.4) | 570(5.9) | ||

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | 38934(41) | 3660(32) | 3411(35.0) | 3081(31.6) | ||

| Integrated Network Cancer Program | 10218(11) | 1085(10) | 1000(10.3) | 944(9.7) | ||

| Clinical Primary Tumor | ||||||

| 1 | 78261(80) | 4523(38) | <0.01 | 3327(34.2) | 3120(31.9) | 0.08 |

| 2 | 12269(14) | 3625(34) | 2838(29.1) | 3294(33.8) | ||

| 3 | 7460(9) | 3280(31) | 3328(34.1) | 3048(31.3) | ||

| 4 | 366(0.4) | 321(3) | 257(2.6) | 288(3.0) | ||

| Surgical Modality | ||||||

| Robotic | 30124(30) | 2345(20) | <0.01 | 1514(15.5) | 1831(18.9) | 0.12 |

| Laparoscopic | 30625(31) | 2941(25) | 3214(33.0) | 2371(24.3) | ||

| Open | 38347(39) | 6581(55) | 5022(51.5) | 5548(56.9) | ||

| Year of Diagnosis | ||||||

| 2010 | 18649(19) | 2209(19) | 0.86 | 1738(17.8) | 1797(18.4) | 0.40 |

| 2011 | 19099(19) | 2264(19) | 1849(19.0) | 1827(18.7) | ||

| 2012 | 19913(20) | 2381(20) | 2000(20.5) | 1972(20.2) | ||

| 2013 | 20428(21) | 2448(21) | 2074(21.3) | 1998(20.5) | ||

| 2014 | 21007(21) | 2565(22) | 2089(21.4) | 2156(22.1) | ||

NCDB defines education attainment as the proportion of adults in the patient’s zip code who did not graduate from high school. NCDB determines household income by matching patient’s zip code at diagnosis against the 2012 American Community Survey Data (US Census Bureau). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population are listed in Table 1 (unmatched population). Results of LND rates by clinical T stage are listed in Table 2. A total of 1,794 patients had cN+ disease, 1,287 of whom were pN+ (Table 3). The proportion of cN+ patients who were pN+ was 71.7%. The proportion of patients undergoing LND did not significantly change from 2010 to 2014 (p=0.29). Three surgical approaches were reported: robotic 2345 (20%), laparoscopic 2941 (25%), and open 6581 (55%). Of 1725 cN+ patients, 214 (12%), 359 (20%), and 1152 (67%), underwent robotic, laparoscopic, and open LND, respectively (p<0.0001). Open surgery was associated with greater mean LN yield (5.9±7.1) compared to robotic (5.1±5.9) or laparoscopic surgery (3.9±4.9) (p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Lymphadenectomy Utilization Across Clinical T Stage

| T Stage | No LND n(%) |

Yes LND n(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 78261 (95) | 4523 (5) |

| 2 | 12269 (77) | 3625 (23) |

| 3 | 7460 (69) | 3280 (31) |

| 4 | 366 (53) | 321 (47) |

Table 3.

Distribution of Patients based on Clinical and Pathologic Nodal Status

| Clinical | Pathologic | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Yes | 1,287 | 507 | 1,794 |

| No | 677 | 36,562 | 37,239 |

| Total | 1,964 | 37,069 | 39,033 |

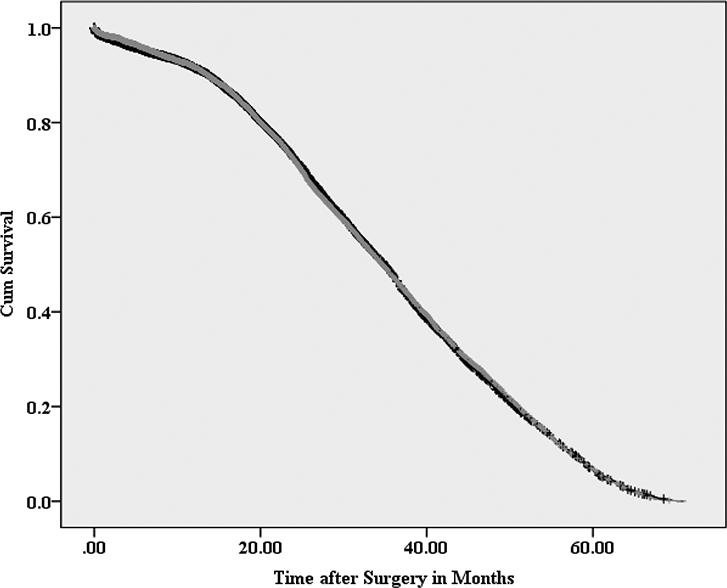

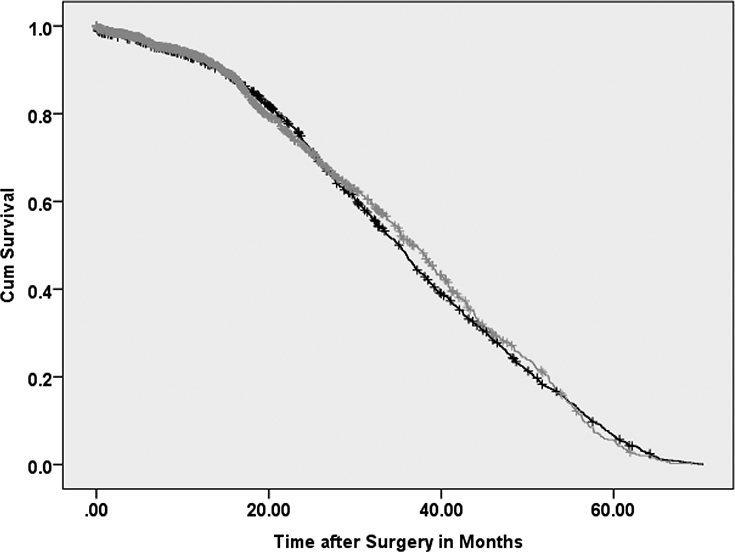

Table 1 also shows clinical and demographic characteristics after PSM procedures (n=19,500, matched population). There was no significant improvement in median OS for patients undergoing LND compared to no LND patients (34.7 vs. 34.9 months, respectively; p = 0.98) (Figure 1). On Cox regression analysis, LND dissection was not associated with an OS benefit (HR 1.00; 95% CI 0.97–1.04). Similarly, there was no significant OS benefit (p=0.90) for cN+ patients undergoing LND compared to cN+ no LND patients, 36.7 (95%CI: 35.9–37.5) vs 35.1 (95%CI: 34.6–35.7) months respectively (Figure 2). There was no significant OS benefit (p=0.93) in patients having ≥3 LN examined (34.8 months, 95%CI 34.1–35.4) compared to no LND patients (34.9 months, 95%CI 34.5–35.2). When excluding patients (n=1,206 (6.2%)) who had either neoadjuvant or adjuvant systemic therapy, no significant OS benefit (p=0.70) between patients receiving an LND (34.8 months, 95%CI 34.3–35.2) compared to no LND patients (34.8 months, 95%CI 34.4–35.2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for patients with and without lymphadenectomy (yes=gray/no=black) after propensity score matching

Log Rank Test p value=0.98, Lymphadenectomy yes vs. no

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for patients with clinical N+ who had lymphadenectomy (yes=gray/no=black) and patients with no lymphadenectomy

Log Rank Test p value=0.90, Lymphadenectomy yes vs. no

Discussion

Using a population-based cohort of patients with non-metastatic RCC, our findings reveal that no overall survival benefit can be attributed to performing a LND. To our knowledge, this is the largest study examining OS in patients who underwent lymphadenectomy at the time of nephrectomy/partial nephrectomy. The large sample size allowed us to use propensity-score matching to minimize selection bias commonly noted in observational data and likely seen in earlier studies. The results of the current study are interesting given the commonly described practice of performing a LND with high risk or clinically node positive disease (Figure 1). Specifically, even in the subgroup of patients with cN+ disease, no significant survival benefit was seen for patients who underwent a LND (Figure 2).

Robson and colleagues first described a possible benefit to removing local lymph nodes at the time of nephrectomy several decades ago19. Since then, the data supporting this practice has been mixed. To date, phase III EORTC 30881 study is the only randomized clinical trial evaluating the effect of LND combined with radical nephrectomy, but it did not demonstrate improved survival with LND11. However, this study only examined patients who were pT1–3 who did not have clinically detectable lymph nodes prior to surgery, possibly missing a considerable portion of the population that might benefit from LND. Similarly, Pantuck et al. retrospectively analyzed 535 patients with RCC at a single institution that had no clinical evidence of lymph node involvement. In this cohort, 238 patients underwent a LND, with no benefit in survival compared to patients who underwent a nephrectomy alone (p=0.42)8. On the other hand, patients with N+ disease from this study did have a significant survival advantage when undergoing LND, with the median survival approximately five months greater8.

Our results are similar to a recent report by Gershman et al., who retrospectively analyzed 1797 patients from a single institution who underwent RN for non-metastatic RCC20. They found that in the 108 patients with preoperative radiographic features of lymph node positive disease, there was no difference in the development of distant metastases, CSS, or ACM when a LND was performed. Further, the latest work of Gershman et al., in a multi-institutional cohort of 2722 patients, again found LND for M0 RCC was not associated with any oncologic benefit (risk of distant metastatic disease, CSS, or ACM). These results were maintained even in a subgroup analysis of patients with cLN+ disease12. Additionally, our results echo that of EORTC 30881, in which patients without clinical evidence of lymph node disease did not benefit from a LND11. However, as the authors of that study concluded, there was no increase in morbidity or mortality from LND and in the absence of further large scale clinical trials, abandoning LND altogether may miss a population of patients who would benefit from it. At present, it is unclear whether neoadjuvant or adjuvant systemic therapy would influence the effect of LND. Our finding that there was no OS benefit with a LND for those who had no neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatments would seem to further call into question the true oncologic benefit of the procedure. However, with the recent FDA approval of novel immunologic therapies and an adjuvant targeted therapy, it may reasonable to consider LND for the purpose of staging and to help guide future therapeutic choices21–23.

Previous reports have provided evidence that tumor size was correlated with LN involvement24, 25. In fact, a recent study showed that the probability of having LN metastases significantly increased in patients with cT1-T2N0M0 disease when the clinical tumor size was ≥ 7 cm26. Given the low incidence of lymph node metastases in the absence of clinical suspicion, many have suggested that LND be reserved for patients with clinically N+ disease or patients at high-risk (cT3-T4N0 or cTanyN1)27–30. Delacroix Jr. et al. looked at outcomes of 68 patients with node positive RCC who underwent LND at the time of nephrectomy and found that 22.1% had no evidence of recurrence after a median follow-up of 43.5 months31. Thus, the authors argued that durable survival could be seen in this population. Whitson et al. commented on this by evaluating the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database32. This analysis demonstrated that although no difference in disease specific survival was noted in patients with negative lymph nodes after LND, increased lymph node yield had a positive survival effect on pN+ patients.

Current guidelines from both the AUA and NCCN reflect the uncertainty of the role of LND for RCC2, 33. While acknowledging that the therapeutic benefit of LND has not been well established, the NCCN does recommend it for patients with palpable or enlarged lymph nodes on preoperative imaging tests. In a somewhat similar guideline statement, the AUA proposes that when there is suspicious lymphadenopathy seen preoperatively or at the time of the nephrectomy, a LND should be done for staging and prognostic purposes2.

It is interesting to note from our study that the proportion of patients undergoing LND have not significantly changed from 2010 to 2014. Although much of the information that suggests there is little oncologic role for LND comes from studies that precede this time frame, any change in practice patterns were not captured by our data. Our study would also seem to suggest that there currently is an overutilization of LND, especially for patients with lower stage disease. Reported rates of lymph node metastases are between 13–21% of all RCC stages, with increasing stage associated with a higher incidence34. Capitanio et al. looked at a series of 3507 patients and showed that only 1.1% of patients with stage T1 disease and 2.3% of patients with stage T2 disease had positive lymph nodes35. However, we found in our analysis that 5% and 23% of patients underwent a LND who were stage T1 or T2, respectively (Table 2).

There are several limitations to our study36, 37. First, this study is retrospective in nature and subject to all limitations inherent in such a design including coding and measurement error in data collection and losses to follow up. Second, the National Cancer Database only contains information regarding overall survival; therefore, we cannot assess the role of LND with respect to cancer specific or distant metastasis free survival. Third, the NCDB pools data from patients treated at only facilities participating in the Committee on Cancer accreditation program, and so may not be representative of the total population. Although for this study, restricting the analysis to institutions with a robust cancer program increases the likelihood that clinical staging and surgical technique issues were minimized. Finally, PSM helps with optimization of matching and stratification but does not substitute for randomization, as additional misclassification issues may still be present due to unmeasured or unknown confounders. Despite these limitations, we believe this study includes the largest sample size to date for analyzingthe trends and outcomes associated with LND for RCC. Well-designed clinical trials are still needed to better define the role of LND, especially in patients with high stage disease.

Conclusions

Among all RCC patients, LNDs were often performed for low stage disease, suggesting a potential overutilization of LND. No OS benefit was seen in any subgroup of patients undergoing LND, including those with cLN+ disease. Further investigation is needed to determine which patient populations may benefit from LND alone or in combination with adjuvant systemic therapy.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Lymph node (LN) involvement in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is associated with a poor prognosis. The aim of our study was to analyze overall survival (OS) after LND for non-metastatic RCC and to characterize contemporary practice patterns.

The National Cancer Database was queried for patients with non−metastatic RCC who underwent either partial or radical nephrectomy from 2010−2014. A total of 11,867 underwent surgery and LND. To minimize selection bias, propensity score matching (PSM) was used.

Among all RCC patients, LNDs were often performed for low stage disease, suggesting a potential overutilization of LND. No OS benefit was seen in any subgroup of patients undergoing LND. Further investigation is needed to determine which patient populations may benefit most from LND.

Acknowledgement:

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (P30CA072720).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin, 68: 7, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell S, Uzzo RG, Allaf ME et al. : Renal Mass and Localized Renal Cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol, 198: 520, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhindi B, Wallis CJD, Boorjian SA et al. : The role of lymph node dissection in the management of renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int, 121: 684, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruins HM, Veskimae E, Hernandez V et al. : The impact of the extent of lymphadenectomy on oncologic outcomes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol, 66: 1065, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson AJ, Sheinfeld J: The role of retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in the management of testicular cancer. Urol Oncol, 22: 225, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leyh-Bannurah SR, Budaus L, Pompe R et al. : North American Population-Based Validation of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Practice Guideline Recommendation of Pelvic Lymphadenectomy in Contemporary Prostate Cancer. Prostate, 77: 542, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trinh QD, Schmitges J, Bianchi M et al. : Node-positive renal cell carcinoma in the absence of distant metastases: predictors of cancer-specific mortality in a population-based cohort. BJU Int, 110: E21, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pantuck AJ, Zisman A, Dorey F et al. : Renal cell carcinoma with retroperitoneal lymph nodes: role of lymph node dissection. J Urol, 169: 2076, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroeger N, Pantuck AJ, Wells JC et al. : Characterizing the impact of lymph node metastases on the survival outcome for metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with targeted therapies. Eur Urol, 68: 506, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ristau BT, Manola J, Haas NB et al. : Retroperitoneal Lymphadenectomy for High Risk, Nonmetastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: An Analysis of the ASSURE (ECOG-ACRIN 2805) Adjuvant Trial. J Urol, 199: 53, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blom JH, van Poppel H, Marechal JM et al. : Radical nephrectomy with and without lymph-node dissection: final results of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) randomized phase 3 trial 30881. Eur Urol, 55: 28, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gershman B, Thompson RH, Boorjian SA et al. : Radical Nephrectomy with or without Lymph Node Dissection for High Risk Nonmetastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Multi-Institutional Analysis. J Urol, 199: 1143, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gershman B, Moreira DM, Thompson RH et al. : Renal Cell Carcinoma with Isolated Lymph Node Involvement: Long-term Natural History and Predictors of Oncologic Outcomes Following Surgical Resection. Eur Urol, 72: 300, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John NT, Blum KA, Hakimi AA: Role of lymph node dissection in renal cell cancer. Urol Oncol, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP et al. : The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol, 15: 683, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winchester DP, Stewart AK, Bura C et al. : The National Cancer Data Base: a clinical surveillance and quality improvement tool. J Surg Oncol, 85: 1, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Agostino RB Jr.: Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med, 17: 2265, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austin PC: Assessing balance in measured baseline covariates when using many-to-one matching on the propensity-score. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 17: 1218, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robson CJ, Churchill BM, Anderson W: The results of radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol, 101: 297, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gershman B, Thompson RH, Moreira DM et al. : Radical Nephrectomy With or Without Lymph Node Dissection for Nonmetastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Propensity Score-based Analysis. Eur Urol, 71: 560, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravaud A, Motzer RJ, Pandha HS et al. : Adjuvant Sunitinib in High-Risk Renal-Cell Carcinoma after Nephrectomy. N Engl J Med, 375: 2246, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motzer RJ, Ravaud A, Patard JJ et al. : Adjuvant Sunitinib for High-risk Renal Cell Carcinoma After Nephrectomy: Subgroup Analyses and Updated Overall Survival Results. Eur Urol, 73: 62, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute. Nivolumab in Treating Patients With Localized Kidney Cancer Undergoing Nephrectomy. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT03055013

- 24.Hutterer GC, Patard JJ, Perrotte P et al. : Patients with renal cell carcinoma nodal metastases can be accurately identified: external validation of a new nomogram. Int J Cancer, 121: 2556, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capitanio U, Abdollah F, Matloob R et al. : When to perform lymph node dissection in patients with renal cell carcinoma: a novel approach to the preoperative assessment of risk of lymph node invasion at surgery and of lymph node progression during follow-up. BJU Int, 112: E59, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dell’Oglio P, Larcher A, Muttin F et al. : Lymph node dissection should not be dismissed in case of localized renal cell carcinoma in the presence of larger diseases. Urol Oncol, 35: 662 e9, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capitanio U, Becker F, Blute ML et al. : Lymph node dissection in renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol, 60: 1212, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giuliani L, Giberti C, Martorana G et al. : Radical extensive surgery for renal cell carcinoma: long-term results and prognostic factors. J Urol, 143: 468, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canfield SE, Kamat AM, Sanchez-Ortiz RF et al. : Renal cell carcinoma with nodal metastases in the absence of distant metastatic disease (clinical stage TxN1–2M0): the impact of aggressive surgical resection on patient outcome. J Urol, 175: 864, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margulis V, Wood CG: The role of lymph node dissection in renal cell carcinoma: the pendulum swings back. Cancer J, 14: 308, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delacroix SE Jr., Chapin BF, Chen JJ et al. : Can a durable disease-free survival be achieved with surgical resection in patients with pathological node positive renal cell carcinoma? J Urol, 186: 1236, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitson JM, Harris CR, Reese AC et al. : Lymphadenectomy improves survival of patients with renal cell carcinoma and nodal metastases. J Urol, 185: 1615, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Network NCC: Kidney Cancer Version (32018) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bekema HJ, MacLennan S, Imamura M et al. : Systematic review of adrenalectomy and lymph node dissection in locally advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol, 64: 799, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capitanio U, Jeldres C, Patard JJ et al. : Stage-specific effect of nodal metastases on survival in patients with non-metastatic renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int, 103: 33, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boffa DJ, Rosen JE, Mallin K et al. : Using the National Cancer Database for Outcomes Research: A Review. JAMA Oncol, 3: 1722, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole AP, Friedlander DF, Trinh QD: Secondary data sources for health services research in urologic oncology. Urol Oncol, 36: 165, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.