Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study is to evaluate the relationship of leading causes of death with gradients of cognitive impairment and multimorbidity.

Method:

This is a population-based study using data from the linked 1992-2010 Health and Retirement Study and National Death Index (n = 9,691). Multimorbidity is defined as a combination of chronic conditions, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes. Regression trees and Random Forest identified which combinations of multimorbidity associated with causes of death.

Results:

Multimorbidity is common in the study population. Heart disease is the leading cause in all groups, but with a larger percentage of deaths in the mild and moderate/severe cognitively impaired groups than among the noncognitively impaired. The different “paths” down the regression trees show that the distribution of causes of death changes with different combinations of multimorbidity.

Discussion:

Understanding the considerable heterogeneity in chronic conditions, functional limitations, geriatric syndromes, and causes of death among people with cognitive impairment can target care management and resource allocation.

Keywords: comorbidity, mortality, cause of death, cognitive status

Introduction

Cognitive impairment (CI) is common in older adults. An estimated 3.4 million Americans (prevalence: 13.9%) above age 70 have Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia (AD/dementia; Plassman et al., 2007). An additional 5.4 million (prevalence: 22.8%) have CI without dementia (Plassman et al., 2008). However, most people with CI die from causes other than those directly related to AD/dementia (Contador et al., 2014; Perna et al., 2015; Shipley, Der, Taylor, & Deary, 2008). Many of these deaths are due to chronic disease, which is also common in older adults, with more than 75% suffering from multiple (two or more) concurrent conditions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Furthermore, the majority of older adults suffer from one or more functional limitations or geriatric syndromes that also contribute to health decline and mortality (Cigolle, Ofstedal, Tian, & Blaum, 2009; Inouye, Studenski, Tinetti, & Kuchel, 2007; Koroukian, Schiltz, Warner, Stange, & Smyth, 2016). Although CI and chronic disease, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes often co-occur, little is known about how the patterns of multimorbidity vary across the spectrum of cognitive function and how these patterns relate to cause-specific mortality.

Understanding leading causes of mortality is important for clinical practice as it can suggest which clinical needs should concern a person most (Hurty, 1910). When patients have multiple unrelated conditions or functional disabilities, they may neglect some if one condition is prioritized over others for care (Redelmeier, Tan, & Booth, 1998). This is especially true for patients with AD/dementia, as providers may focus on the CI during visits, leaving little time to discuss other health problems. CI can also complicate the management of chronic conditions as patients may have difficulty remembering to take medications and recalling symptoms, and communicating symptoms to the provider. In addition, they may have limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs), further exacerbating difficulties with self-management. However, cognitive status is seldom assessed in patients with chronic conditions. One study conducted in small towns documented CI in only 15% of the patients that had it (Ganguli et al., 2004).

Much heterogeneity exists among people with CI in terms of severity (Mungas et al., 2010), and the cause-specific mortality likely differs for people with different combinations of multimorbidity. However, because of the many different possible combinations of morbidity (Koroukian et al., 2017; Sorace et al., 2011), examining them all is impractical with traditional methods. However, data mining approaches can empirically identify relevant combinations that influence an outcome (Koroukian, Schiltz, Warner, Sun, Bakaki, et al., 2016; Schiltz et al., 2017), in this case, cause-specific mortality.

The aims of this article are (a) to examine the distribution of leading causes of death by gradient of CI and (b) to explore how the distribution of causes of death changes for different combinations of multimorbidity (chronic disease, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes) by gradient of CI.

Method

Study Design and Population

This study is a retrospective study using the 1992-2010 Health and Retirement Study (HRS) linked to the National Death Index (NDI) through 2011, the most recent years for which these linked data are currently available. The HRS-NDI data were linked by the National Center for Health Statistics using probabilistic matching (Institute for Social Research, 2013). This study was approved by the Case Western Reserve University Institutional Review Board, and permission to use the data for this study was obtained from the University of Michigan.

The HRS is a longitudinal panel study of adults age 50 and older in the United States (National Institute of Aging, 2007). Surveys are conducted every 2 years either in-person or over the phone. In each wave, data are collected on a variety of measures including demographics, cognitive ability, chronic conditions, self-reported health status, functional status, and geriatric syndromes. The NDI is a centralized database of death record information on file in state’s vital statistics offices, and includes information on the underlying cause of death information coded using International Classification of Diseases, Version 9 (ICD-9) or Version 10 (ICD-10) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011).

The study population includes HRS survey participants for whom we have a linked NDI record of their deaths, and who had participated in the HRS survey (either as self-respondent or proxy) within 3 years preceding death (n = 11,822). Those with missing data on CI were excluded from study population (n = 2,131).

Measures

Our main outcome of interest is underlying cause of death as identified through an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code and recorded in the NDI database. We use a National Center for Health Statistics algorithm, which groups the causes of death into 50 rankable causes (“NCHS 50”), for our main analysis (Heron, 2016). In the regression tree models (described later), we further collapse these into five causes: heart disease, lower respiratory disease, malignant neoplasm, AD/dementia, and “all other.” For parsimony, and because of small numbers with other causes of death, we created the “all other” category. As a secondary analysis, we rank the leading “associated” cause of death, which accounts for the fact that many people have multiple causes of death.

Our main independent variable is Cl as measured in the HRS by an adaptation of the 35-point Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) or by a proxy respondent rating of the subject’s cognitive performance on a 5-point scale (Brandt, Spencer, & Folstein, 1988). We classify people into three categories based on their TICS score: none (≥11), mild (8-10), and moderate/severe (≤7; Langa et ah, 2008). In cases where the TICS was not assessed and a proxy was used, a rating of fair or poor is classified as moderate/severe, a rating of good is classified as mild, and a rating of very good or excellent is classified as none. As noted previously, subjects without a TICS score or proxy response on Cl were removed from study population. The TICS and all covariates were assessed in the last survey wave prior to death, with a median time of 13 months from survey to death (maximum 36 months).

Key covariates are those related to multimorbidity—which we define as the occurrence or co-occurrence of chronic conditions, geriatric syndromes, and/or functional limitations. These variables are measured through self- or proxy-report in the HRS data. Chronic conditions are defined based on whether the respondent was ever told by a physician that he or she had hypertension, heart disease, lung disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), diabetes, stroke, arthritis, cancer, or psychiatric conditions. Additional questions assessed whether the respondent was receiving treatment for a given condition (e.g., medication for hypertension or oxygen for lung disease), which allowed us to categorize each condition as either no disease, mild disease as indicated by self-reported diagnosis alone, or severe disease (Koroukian, Schiltz, Warner, Sun, Bakaki, et al, 2016). Functional limitations are defined by limitations in strength, upper body mobility, lower body mobility, ADLs, or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (Cigolle et al, 2009). Geriatric syndromes, which are conditions commonly experienced by older individuals, include hearing impairment (even when wearing a hearing aid), vision impairment (even when wearing corrective lenses), moderate/severe depressive symptoms, urinary incontinence, and severe pain (Inouye et al., 2007). Geriatric syndromes are self-reported and collected from survey questions that ask if the person ever experienced each of the aforementioned symptoms/events.

Other covariates of interest include the following: age, race, sex, education, marital status, body mass index (BMI), alcohol use, smoking. Age is categorized into intervals (50-64, 65-74, 75-84, and 85+). Race/ethnicity includes four categories: White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and Other. Marital status is identified as marriedor not married (i.e. divorced, widowed, or never married). Years of education are grouped in three categories: less than high school, high school graduate, and college. Smoking status (never smoked, former smoker, and current smoker) and alcohol use (none, moderate, and heavy) included three categories. We characterize BMI (measured as kg/m2) as obese (BMI ≥ 30) or not obese (BMI < 30).

Statistical Analysis

We first provide descriptive data of the study population, and used Rao–Scott chi-square tests accounting for survey design effects to compare differences across levels of cognitive status. We do not use population weights because our study population is only the subset of the HRS that we can link to the NDI and represents multiple time periods. We also tabulated the frequencies of cause of death for each group of cognitive status. We use conditional inference regression tree (CTree) analysis (Hothorn, Homik, & Zeileis, 2006) to identify combinations of covariates associated with cause of mortality. CTree analysis is a nonparametric, machine-learning method that uses repeated binary partitioning of the value spaces of explanatory variables so that each partition corresponds to as homogeneous an outcome as possible. Each covariate is considered as a potential split, including every value of an interval-level variable. Each node can split and form two child nodes, which can in turn split and create two more child nodes each. Nodes that are not split are called terminal nodes, and each study respondent can only be in one terminal node. The criteria we chose for a split are a p value <.001, with a minimum node size of 20 subjects and a maximum tree depth of four levels. CTree is similar to the more well-known classification and regression tree (CART) analysis (Breiman, Friedman, Stone, & Olshen, 1984) but uses a statistical significance test as the splitting criterion rather than Gini impurity or information gain.

A bootstrap aggregation method, Random Forest, determines whether our CTree models capture the most important variables related to the outcomes. The Random Forest algorithm creates multiple decision trees using random variable selection (Breiman, 2001). For each Random Forest model, we created 5,000 trees and sampled three of the explanatory variables at each node split. We use R Version 3.3.0 and the “partykit” (CTree) and “randomForest” (Random Forest) packages for the regression tree analysis, and SAS Version 9.3 for data management and descriptive statistics (Hothorn & Zeileis, 2014; Liaw & Wiener, 2002; SAS Institute, 2011).

Results

There are 9,691 deceased people in the study population, of whom 636 (6.6%) had mild CI before death and 1,438 (14.8%) had moderate/severe CI (Figure S1). A higher percentage of people with CI preceding death are older, female, racial minorities, and single, widowed, or divorced compared with those without CI (Table 1). The percentage that are current or former smokers, moderate to heavy drinkers, and obese is higher in the noncognitively impaired group. Proxy respondents make up just 2% of the no-CI group, but 32% of the mild CI group, and 71% of the moderate/severe CI group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population by Cognitive Status.

| No cognitive impairment |

Mild cognitive impairment |

Moderate/severe cognitive impairment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Total subjects | 7,617 | 636 | 1,438 | |||

| Age categories | ||||||

| 50-64 | 1,269 | 16.7 | 24 | 3.8 | 34 | 2.4 |

| 65-74 | 2,014 | 26.4 | 91 | 14.3 | 163 | 11.3 |

| 75-84 | 2,725 | 35.8 | 244 | 38.3 | 465 | 32.4 |

| 85+ | 1,609 | 21.1 | 277 | 43.6 | 776 | 54.0 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 3,678 | 48.3 | 268 | 42.1 | 552 | 38.4 |

| Female | 3,939 | 51.7 | 368 | 57.9 | 886 | 61.6 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 6,048 | 79.4 | 426 | 67.0 | 999 | 69.5 |

| Black | 1,050 | 13.8 | 141 | 22.2 | 289 | 20.1 |

| Hispanic | 419 | 5.5 | 58 | 9.1 | 123 | 8.6 |

| Other | 100 | 1.3 | 11 | 1.7 | 27 | 1.9 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 3,763 | 49.4 | 237 | 37.3 | 501 | 34.8 |

| Not married | 3,854 | 50.6 | 399 | 62.7 | 937 | 65.2 |

| Years of education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 2,774 | 36.4 | 397 | 62.4 | 772 | 53.7 |

| High school | 2,510 | 33.0 | 141 | 22.2 | 355 | 24.7 |

| College | 2,333 | 30.6 | 98 | 15.4 | 311 | 21.6 |

| Smoke | ||||||

| Never | 2,524 | 33.1 | 302 | 47.5 | 697 | 48.5 |

| Former | 3,826 | 50.2 | 276 | 43.4 | 651 | 45.3 |

| Current | 1,267 | 16.6 | 58 | 9.1 | 90 | 6.3 |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| None | 5,778 | 76.0 | 560 | 88.1 | 1,307 | 91.0 |

| Moderate | 1,476 | 19.4 | 69 | 10.8 | 111 | 7.7 |

| Heavy | 344 | 4.5 | 7 | 1.1 | 18 | 1.3 |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Not obese | 6,214 | 81.6 | 565 | 88.8 | 1,275 | 88.7 |

| Obese | 1,403 | 18.4 | 71 | 11.2 | 163 | 11.3 |

| Proxy respondent | ||||||

| No | 7,444 | 97.7 | 433 | 68.1 | 420 | 29.2 |

| Yes | 173 | 2.3 | 203 | 31.9 | 1,018 | 70.8 |

Multimorbidity is common in the study population, with 95% of the decedents having two or more chronic conditions. In the mild CI and moderate/severe CI, the percent without multimorbidity is just 2% and 1%, respectively. Table 2 shows the breakdown of each chronic condition, functional limitation, and geriatric syndrome by cognitive status. All functional limitations and geriatric syndromes are more common in those with CI. Especially notable are the differences in limitations in ADLs (12% no CI, 31% mild CI, 52% moderate/severe CI) and IADLs (32% no CI, 65% mild CI, 88% moderate/severe CI). The percentage of those with chronic conditions across cognitive status groupings is mixed. Mild heart disease, severe (i.e., actively treated) psychiatric conditions, and mild/severe stroke are more common among the cognitively impaired, whereas other conditions like COPD and severe cancer are more common in the no-CI group.

Table 2.

Multimorbidity in the Study Population by Cognitive Status.

| No cognitive impairment | Mild cognitive impairment | Moderate/severe cognitive impairment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Total subjects | 7,617 | 636 | 1,438 | |||

| Chronic conditions | ||||||

| Hypertension, mild | 1,273 | 16.7 | 137 | 21.5 | 351 | 24.4 |

| Hypertension, severe | 3,622 | 47.6 | 304 | 47.8 | 662 | 46.0 |

| Diabetes, mild | 1,450 | 19.0 | 131 | 20.6 | 266 | 18.5 |

| Diabetes, severe | 610 | 8.0 | 61 | 9.6 | 106 | 7.4 |

| Stroke, mild | 1,774 | 23.3 | 227 | 35.7 | 437 | 30.4 |

| Stroke, severe | 473 | 6.2 | 72 | 11.3 | 267 | 18.6 |

| Heart disease, mild | 2,901 | 38.1 | 297 | 46.7 | 693 | 48.2 |

| Heart disease, severe | 548 | 7.2 | 43 | 6.8 | 80 | 5.6 |

| COPD, mild | 1,034 | 13.6 | 72 | 11.3 | 105 | 7.3 |

| COPD, Severe | 508 | 6.7 | 34 | 5.3 | 75 | 5.2 |

| Arthritis, mild | 2,407 | 31.6 | 183 | 28.8 | 384 | 26.7 |

| Arthritis, severe | 2,237 | 29.4 | 203 | 31.9 | 459 | 31.9 |

| Psychiatric, mild | 688 | 9.0 | 42 | 6.6 | 156 | 10.8 |

| Psychiatric, severe | 588 | 7.7 | 80 | 12.6 | 282 | 19.6 |

| Cancer, mild | 1,473 | 19.3 | 112 | 17.6 | 276 | 19.2 |

| Cancer, severe | 537 | 7.1 | 36 | 5.7 | 51 | 3.5 |

| Functional limitations | ||||||

| Limitations in ADLs | 901 | 11.8 | 195 | 30.7 | 741 | 51.5 |

| Limitations in IADLs | 2,448 | 32.1 | 416 | 65.4 | 1,262 | 87.8 |

| Strength limitations | 5,456 | 71.6 | 524 | 82.4 | 1,283 | 89.2 |

| Upper body limitations | 4,286 | 56.3 | 489 | 76.9 | 1,218 | 84.7 |

| Lower body limitations | 6,066 | 79.6 | 547 | 86.0 | 1,340 | 93.2 |

| Geriatric syndromes | ||||||

| Urinary incontinence | 1,814 | 23.8 | 215 | 33.8 | 831 | 57.8 |

| Visual impairment | 2,631 | 34.5 | 298 | 46.9 | 799 | 55.6 |

| Hearing impairment | 2,265 | 29.7 | 262 | 41.2 | 697 | 48.5 |

| Depressive symptoms* | 1,805 | 24.3 | 147 | 34.1 | 131 | 31.4 |

| Severe pain | 611 | 8.0 | 61 | 9.6 | 122 | 8.5 |

Note. Chronic conditions are categorized as either mild (self-reported diagnosis alone) or severe (if a given condition also causes limitations in usual activities and/or a respondent is receiving treatment). COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ADLs = activities of daily living; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living.

Data on depressive symptoms is missing for 179 subjects in the no cognitive impairment group, 204 in the mild group, and 1,021 in the moderate/severe group.

Table 3 shows the leading cause of death across the three categories of CI. Heart disease is the leading rankable cause in all groups and makes up 28% to 31% of all deaths in each CI group. Conversely, cancers make up a much larger percentage in the no-CI group compared with both CI groups. As expected, AD/dementia-related deaths are much more common in people reporting moderate/severe CI (12%) compared with mild CI (3%) and no CI (1%). Table S1 in the online supplement provides more detail on specific subtypes of heart disease and cancer. Table S2 shows the top 10 associated causes of death—which allows for multiple causes of death per person.

Table 3.

Top 10 Leading Underlying Causes of Death by Cognitive Status.

| No cognitive impairment |

Mild cognitive impairment |

Moderate/severe cognitive impairment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of death | n | % | Cause of death | n | % | Cause of death | n | % | |

| 1 | Heart disease | 2,310 | 30.3 | Heart disease | 196 | 30.8 | Heart disease | 404 | 28.1 |

| 2 | Malignant neoplasm | 2,062 | 27.1 | Malignant neoplasm | 110 | 17.3 | Nonrankable causes | 259 | 18.0 |

| 3 | Nonrankable causes | 839 | 11.0 | Nonrankable causes | 70 | 11.0 | AD/dementia | 173 | 12.0 |

| 4 | Lower respiratory disease | 466 | 6.1 | Cerebrovascular | 57 | 9.0 | Malignant neoplasm | 138 | 9.6 |

| 5 | Cerebrovascular | 438 | 5.8 | War related | 31 | 4.9 | Cerebrovascular | 113 | 7.9 |

| 6 | War related | 348 | 4.6 | Influenza and pneumonia | 30 | 4.7 | Lower respiratory disease | 72 | 5.0 |

| 7 | Diabetes | 230 | 3.0 | Lower respiratory disease | 25 | 3.9 | War related | 50 | 3.5 |

| 8 | Influenza and pneumonia | 175 | 2.3 | Diabetes | 23 | 3.6 | Diabetes | 46 | 3.2 |

| 9 | Nephritis | 146 | 1.9 | AD/dementia | 21 | 3.3 | Influenza and pneumonia | 44 | 3.1 |

| 10 | Septicemia | 106 | 1.4 | Atherosclerosis | 10 | 1.6 | Nephritis | 40 | 2.8 |

| All other | 497 | 6.5 | All other | 63 | 9.9 | All other | 99 | 6.9 | |

Note. AD = Alzheimer’s disease.

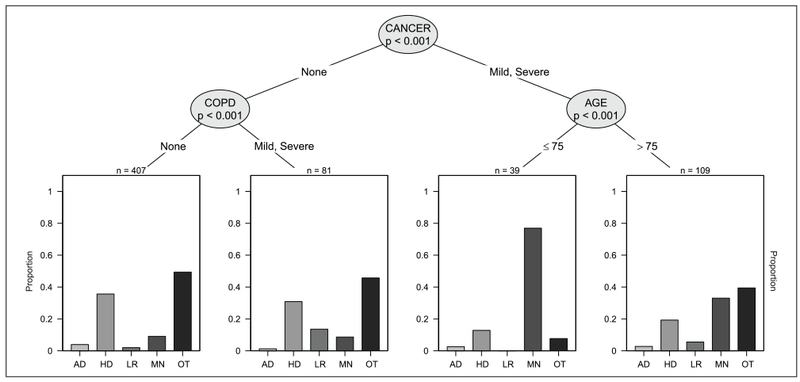

Figure 1 shows the CTree for people with mild CI. The different “paths” down the tree show how the distribution of cause of death changes with different combinations of morbidity. For instance, among those with cancer, those below age 75 years were most likely to die from cancer (67%), but those above age 75 were most likely to die from other causes (57%). Among those without cancer, lower respiratory disease as the cause of death was more common in those with mild or severe COPD compared with those without (14% vs. 2%).

Figure 1.

Distribution of cause of death among those with mild cognitive impairment.

Note. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; HD = heart diseases; LR = lower respiratory diseases; MN = malignant neoplasms; OT = other causes.

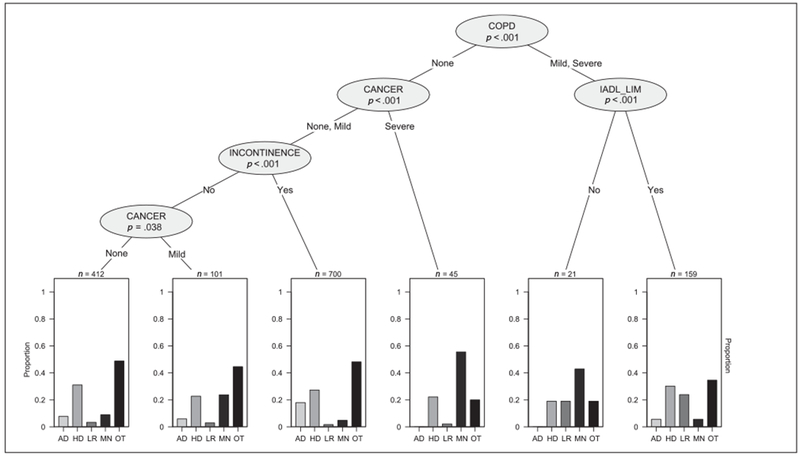

Figure 2 shows the CTree for people with moderate/severe CI. In people with COPD and IADLs limitations the leading causes of death are “other” (35%), heart disease (30%), and lower respiratory disease (24%), whereas for people with COPD but no IADLs limitations the leading cause is cancer (43%). Cancer is the leading cause of death for people without COPD and with severe (actively treated) cancer (56%). AD/dementia is the cause of death in 18% of people without COPD or severe cancer, but having incontinence.

Figure 2.

Distribution of cause of death among those with moderate/severe cognitive impairment.

Note. IADL_LIM = Instrumental activities of daily living; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; HD = heart diseases; LR = lower respiratory diseases; MN = malignant neoplasms; OT = other causes.

For comparison, we show the CTree for the people without CI in the supplemental material (Figure S2). Cancer, COPD, IADLs, and heart disease are frequently appearing covariates in the noncognitively impaired CTree.

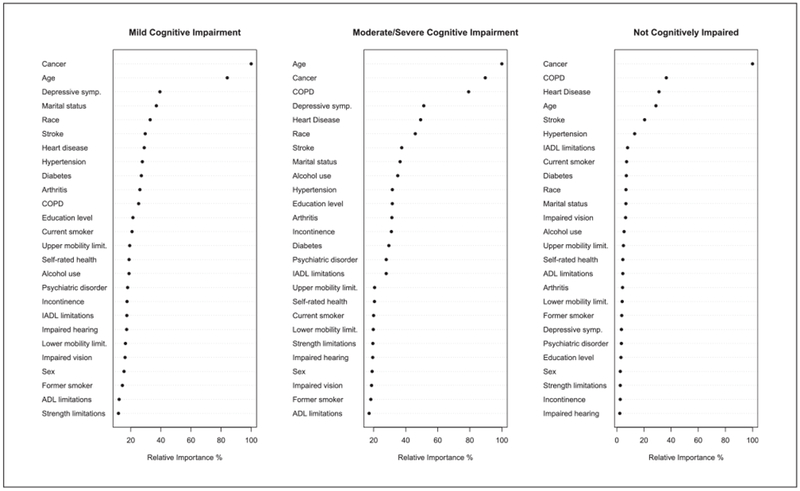

Figure 3 shows the most important covariates that influence the distribution of cause of death from the Random Forest analysis among those with mild, moderate/severe, or no CI prior to death. Many of the same variables that appear in the tree model in Figure 3 also appear in the CTree, lending evidence of validity to our tree models. Cancer status and age are the two most important predictors in both cognitively impaired groups. COPD, stroke, and heart disease are also important factors in all groups. Depression is an important correlate in the mild and moderate/severe cognitively impaired group, but less so in the noncognitively impaired group.

Figure 3.

Random Forest Plot ranking the factors that most influence the distribution of cause of death.

Note. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living; ADLs = activities of daily living.

Discussion

Older adults with CI are a heterogeneous population in terms of their multimorbidity profile. First, we show that people with all levels of CI have significant multimorbidity burden at their time of death. Almost all persons had at least two or more long-term conditions, regardless of cognitive status. However, people with higher levels of CI had greater levels of functional disability and higher prevalence of most geriatric syndromes. This has important implications, as these people may be less able to self-manage their care. The high level of multimorbidity, also makes these patients more at risk for poor care coordination, and some conditions going untreated or undertreated. In line with previous studies, the dose-response relationship is especially noticeable for ADLs and IADLs (Barberger-Gateau et al., 1992; Gill, Richardson, & Tinetti, 1995).

Second, we show that people with CI die from many different causes, most of which are not directly related to cognition. Of the 2,074 deaths in our study population of people with any level of CI, only 192 (9%) died of AD/dementia-related causes. These results provide strong circumstantial evidence that AD/dementia is underreported in death certificates, a finding that has been corroborated by a recent study (James et al., 2014). The leading causes of death are similar across all levels of cognitive status, differing only by a few percentage points. This suggests that much of the variation in cause of death is due to factors other than cognitive level. The two exceptions are AD/dementia, more common with increasing level of CI, and cancer, a more common cause of death in those without CI. While the former makes intuitive sense, the reason for the latter is less clear. It may be because persons with higher levels of CI have more comorbidities, and hence more possible competing causes of death. Other possible explanations are survival bias, in that cancer kills many people before they have a chance to develop cognitive limitations, and diagnostic bias, in that once people have a diagnosis of dementia, family members and clinicians may be less likely to pursue diagnostic evaluation of symptoms that could be markers of cancer.

Finally, we show that the distribution of cause of death varies by combination of morbidity even within different levels of CI. Many of the findings may not be individually surprising: For example, people with cancer more likely die from cancer and people with COPD more likely die from lower respiratory failure. However, it demonstrates the heterogeneity in the cognitively impaired population in terms of multimorbidity and risk factors and the role they play in cause-specific mortality. The machine-learning approach we used yields some empirical insights that might not be obvious with more traditional parametric methods. For example, cancer was the leading cause of death for those in the mild CI group with cancer and age below 75 years (67% of all deaths), but not in those above 75 years (22% of all deaths). From a clinical standpoint, this shows that cancer treatment and prevention may be a priority for persons with CI before age 75, but less of a priority as patients grow older.

There are several limitations to our analysis. There may be misclassification of the underlying cause of death in death certificates, because death can have multiple causes. While physicians should record the underlying cause of death, an immediate or secondary cause of death may be recorded instead (Kircher, Nelson, & Burdo, 1985). However, death certificates are still widely used in research and public health policymaking, because they are readily available, and no other alternative exists at a national scale. Another limitation is that CTree produces a single tree, which is in contrast with the Random Forest analysis, which uses subsets of the data and variables, as well as bootstrapping, to produce many trees. However, many of the same covariates that appeared in our CTree models are also the ones that were identified as the most important by the Random Forest method, lending further validity to our model. Because there is a time gap between survey response and death, persons may have developed additional morbidities and experience cognitive decline prior to death. Therefore, there may be some misclassification biased toward the noncognitively impaired group and “not present” for each multimorbidity measure.

In conclusion, this study shows considerable heterogeneity in the leading cause of death across gradients of CI, which we partly explain by different combinations of morbidity and risk factors. Understanding this heterogeneity can help with care management for people with CI by helping clinicians to advise patients and family members about prognosis and the many possible health and illness pathways. In addition, the information presented here on specific functional health and diagnoses associated with CI can be used to increase clinical awareness and resource allocation to meet the specific likely emerging medical care and functional support needs of people living with dementia. Finally, the tree models could be adapted into a tool that identifies the most likely causes of death for a patient with a given multimorbidity profile. This could help clinicians to identify the most urgent clinical needs in complex patients, and focus treatment and preventive care accordingly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This publication is a product of the Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods at Case Western Reserve University, supported by Cooperative Agreement, Cooperative Agreement Number, SIP 14-004, U48 DP005030-01S3, under the Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Centers Program, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Some of the authors were also supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R21 HS023113) and the Clinical & Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland (UL1 TR000439 and KL2 TR000440) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Dr. Stange is supported as a scholar of the Institute for Integrative Health and as a clinical research professor of the American Cancer Society (ACS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the ACS, CDC, NIH, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available for this article online.

References

- Barberger-Gateau P, Commenges D, Gagnon M, Letenneur L, Sauvel C, & Dartigues J-F (1992). Instrumental activities of daily living as a screening tool for cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly community dwellers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40, 1129–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01802.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Spencer M, & Folstein M (1988). The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology, 1, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L (2001). Random Forests. Machine Learning, 45, 5–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1010933404324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L, Friedman J, Stone J, & Olshen R (1984). Classification and regression trees (1st ed.). Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011, January 1). National Death Index. HealthData.gov. Retrieved from https://www.healthdata.gov/dataset/national-death-index

- Cigolle CT, Ofstedal MB, Tian Z, & Blaum CS (2009). Comparing models of frailty: The Health and Retirement Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, 830–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contador I, Bermejo-Pareja F, Mitchell AJ, Trincado R, Villarejo A, Sánchez-Ferro Á, & Benito-León J (2014). Cause of death in mild cognitive impairment: A prospective study (NEDICES). European Journal of Neurology: The Official Journal of the European Federation of Neurological Societies, 21, 253–e9. doi: 10.1111/ene.12278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, Rodriguez E, Mulsant B, Richards S, Pandav R, Bilt JV, … DeKosky ST (2004). Detection and management of cognitive impairment in primary care: The Steel Valley Seniors Survey. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52, 1668–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM, Richardson ED, & Tinetti ME (1995). Evaluating the risk of dependence in activities of daily living among community-living older adults with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences, 50(5), M235–M241. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50A.5.M235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron M (2016). Deaths: Leading causes for 2014 (National Vital Statistics Report, Vol. 65, No. 5). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Hornik K, & Zeileis A (2006). Unbiased recursive partitioning: A conditional inference framework. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 15, 651–674. doi: 10.1198/106186006X133933 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, & Zeileis A (2014). partykit: A modular toolkit for recursive partitioning in R (Working paper). Faculty of Economics and Statistics, University of Innsbruck; Retrieved from http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/innwpaper/2014-10.htm [Google Scholar]

- Hurty JN (1910). The bookkeeping of humanity. Journal of the American Medical Association, 55, 1157–1160. doi: 10.1001/jama.1910.04330140001001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, & Kuchel GA (2007). Geriatric syndromes: Clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55, 780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Social Research. (2013). Health and Retirement Study (Cross-Year NDI Cause of Death (Restricted) Version 5.0, Data Description and Usage). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/rda/metadata/NDI/ndiCausedd2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- James BD, Leurgans SE, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Yaffe K, & Bennett DA (2014). Contribution of Alzheimer disease to mortality in the United States. Neurology, 82, 1045–1050. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher T, Nelson J, & Burdo H (1985). The autopsy as a measure of accuracy of the death certificate. The New England Journal of Medicine, 313, 1263–1269. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511143132005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroukian SM, Schiltz NK, Warner DF, Stange KC, & Smyth KA (2017). Increasing burden of multimorbidity across gradients of cognitive impairment. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 32, 408–417. doi: 10.1177/1533317517726388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroukian SM, Schiltz NK, Warner DF, Sun J, Bakaki PM, Smyth KA, … Given CW (2016). Combinations of chronic conditions, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes that predict health outcomes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31, 630–637. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3590-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroukian SM, Schiltz NK, Warner DF, Sun J, Stange KC, Given CW, & Dor A (2017). Multimorbidity: Constellations of conditions across subgroups of midlife and older individuals, and related Medicare expenditures. Journal of Comorbidity, 7, 33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa KM, Larson EB, Karlawish JH, Cutler DM, Kabeto MU, Kim SY, & Rosen AB (2008). Trends in the prevalence and mortality of cognitive impairment in the United States: Is there evidence of a compression of cognitive morbidity? Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 4, 134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw A, & Wiener M (2002). Classification and regression by randomForest. R News, 2(3), 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mungas D, Beckett L, Harvey D, Farias ST, Reed B, Carmichael O, … DeCarli C (2010). Heterogeneity of cognitive trajectories in diverse older person. Psychology and Aging, 25, 606–619. doi: 10.1037/a0019502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Aging. (2007). Growing older in America: The Health and Retirement Study. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Perna L, Wahl H-W, Mons U, Saum K-U, Holleczek B, & Brenner H (2015). Cognitive impairment, all-cause and cause-specific mortality among non-demented older adults. Age and Ageing, 44, 445–451. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB, … Wallace RB. (2007). Prevalence of dementia in the United States: The aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology, 29, 125–132. doi: 10.1159/000109998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB, … Wallace RB (2008). Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine, 148, 427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, & Booth GL (1998). The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. The New England Journal of Medicine, 338, 1516–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. (2011). SAS/STAT(R) 9.3 user’s guide (2nd ed.). Cary, NC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Schiltz NK, Warner DF, Sun J, Bakaki PM, Dor A, Given CW, … Koroukian SM (2017). Identifying specific combinations of multimorbidity that contribute to health care resource utilization: An analytic approach. Medical Care, 55, 276–284. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley BA, Der G, Taylor MD, & Deary IJ (2008). Cognition and mortality from the major causes of death: The Health and Lifestyle Survey. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 65, 143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorace J, Wong H-H, Worrall C, Kelman J, Saneinejad S, & MaCurdy T (2011). The complexity of disease combinations in the Medicare population. Population Health Management, 14, 161–166. doi: 10.1089/pop.2010.0044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). Multiple chronic conditions—A strategic framework: Optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.